Abstract

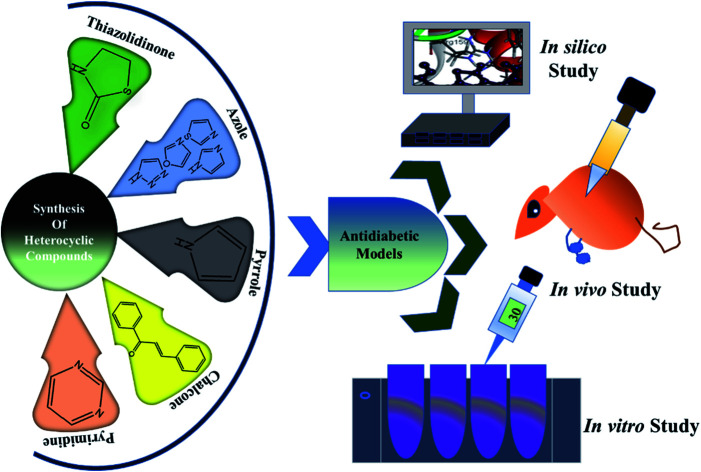

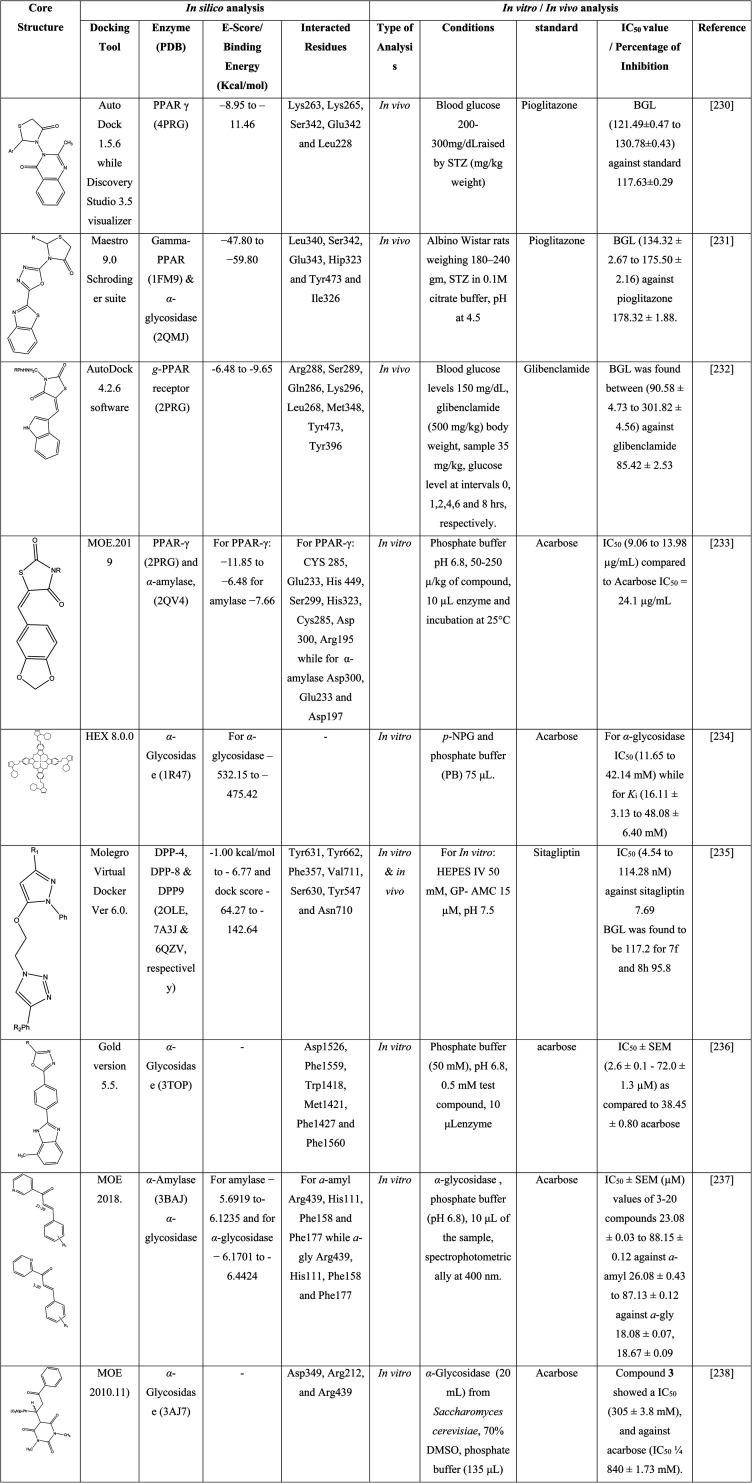

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a major metabolic disorder due to hyperglycemia, which is increasing all over the world. From the last two decades, the use of synthetic agents has risen due to their major involvement in curing of chronic diseases including DM. The core skeleton of drugs has been studied such as thiazolidinone, azole, chalcone, pyrrole and pyrimidine along with their derivatives. Diabetics assays have been performed in consideration of different enzymes such as α-glycosidase, α-amylase, and α-galactosidase against acarbose standard drug. The studied moieties were depicted in both models: in vivo as well as in vitro. Molecular docking of the studied compounds as antidiabetic molecules was performed with the help of Auto Dock and molecular operating environment (MOE) software. Amino acid residues Asp349, Arg312, Arg439, Asn241, Val303, Glu304, Phe158, His103, Lys422 and Thr207 that are present on the active sites of diabetic related enzymes showed interactions with ligand molecules. In this review data were organized for the synthesis of heterocyclic compounds through various routes along with their antidiabetic potential, and further studies such as pharmacokinetic and toxicology studies should be executed before going for clinical trials.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a major metabolic disorder due to hyperglycemia, which is increasing all over the world.

1. Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus1 is an ordinary, chronic,2 persistent,3 and metabolic disease.4 It is a disorder that arises due to the increase of glucose5,6 in blood, which leads to hyperglycemia.7 DM is linked with dysfunction of the eyes,8 kidneys,9 and heart.10 In broad terms,11 DM is classified into type-I DM, which is due to the impairment of pancreatic β cells,11 and type-II DM,12 due to insulin resistance13 or by destruction of secreted insulin.14 Type-II, also known as non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus15 is the most commonly occurring diabetes in 80% of the total affected patients around the world.16 It is a complex disease17 distinguished by resistance of insulin and lower insulin secretion.18 The effect of this disease on social health is closely related to the co-occurrence of both disorders, metabolic and cardiovascular.19 About 0.5 billion patients are affected world wide by these metabolic disorders. It is accountable for nearly 5 million deaths every year.20 DM generally impairs the body's potential to use the energy in food.21 The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that the global spreading number of diabetes has been 108 million people in 1980 which raised to 422 million people in 2014.22 It is presumed that it will rise by 5.4% in 2025.23 Similarly, report from the WHO narrated that about 250 million people are right now living with diabetes and this number is expected to be more than 366 million by 2030. This increase has been linked with lifespan expansion, higher cases of obesity, and stress. Recent trends in medicinal chemistry research have showed that there is a higher acceptance of molecular hybridization for drug synthesis, which is based on the mixture of two or more pharmacophoric moieties of various biologically active substances to prepare a new influential hybrid molecule with greater effectiveness and affinity in comparison with standard one.24 In 2016, it was the seventh most death-causing disease in the world.25 Another report of WHO narrated that more than 400 million cases of diabetes, and this figure may increase to 592 million by 2035, owing to an increased rate of adult-onset diabetes (T2DM).26

1.1. Diabetes mellitus and other diseases

Diabetics carrier person faces various complications27 regarding health28 including endothelial defectiveness,29 a key source for chief macro-vascular complications30 such as hypertension,31 myocardial ischemia,32 and peripheral vasculopathy.33 In the past few days, heart problems, stroke34 are the major reasons for death35 and dysfunction among people with type-II diabetes.36 Lower levels of glucose tolerance37 and higher blood pressure are nearly associated. Hypertension38 and high blood pressure rate39 are mostly common in all types of diabetes and also effects nephrons of kidneys.40 Long-term insulin affects the weight of the patient,41 which is indirectly associated with blood pressure issues. Diabetic patients also have non-specific arteriolar hyalinosis,42 interstitial fibrosis,43 and mild glomerulopathy.44 Although synthetic drugs have so many complications even in the form of their side effects and they are still being sold in the market as therapeutic agents. The chronic DM consequence is higher blood sugar levels, causing the metabolic disturbance of protein,45 fat,46 and carbohydrate.47,48 It is currently the third foremost cause of mortality worldwide.49 It is also associated with numerous postprandial effects50i.e. atrial fibrillation51 dying, obesity,52 blindness,53 lower limb amputation,54 and fatty liver disease.55 All through the current Covid-19 pandemic, it was seen that the likelihoods of diabetic patients56,57 to be sick by the virus are 5–18% higher than the others. However, in the SARS-CoV-1 epidemic in 2002–2003, diabetes was the single sovereign factor to surge the complications.58

1.2. Natural resources for treatment of diabetes mellitus

Aloe,59 mint,60 banaba,61 bitter melon,62 caper bush,63 cinnamon,64 cocoa,65 coffee,66 fenugreek,67 garlic,68 guava,69 turmeric,70 tea,71 walnuts,72 Shaggy bindweed,73Yerba mates,74Bambusa tulda,75Ficus bengalensis,76Ferula orientalis,77Gymnema sylvestre,78Dioscorea japonica,79Artemisia abyssinica,80Phaseolus vulgaris,81Datura quercifolia,82Cassia fistula,83Citrus aurantium,84Ficus benghalensis,85Polygonum aviculare,86Allium tuncelianum,87Astragalus brachycalyx,88Ferulago stelleta,89 and Rhizophora mucronate90 are natural sources that contain chemical moieties which are effective against diabetes.91 However, recent research-based studies showed more aim to develop new drugs that can be provided orally for the therapeutics uses of diabetes disease.92–95

2. Diabetes therapy

The main curative way used for diabetes Type-I is the injection of insulin in the subcutaneous layer of the body, which is an invasive process. However, for diabetes type-II, diet adjustment, exercise, and usage of several antidiabetic medicines.96 These treatments have few sorts of side effects which are given as pain in the area of injection, obesity, low sugar level, and less control of blood glucose levels (BGL). Therefore, novel antidiabetic agents that can be administered using a less-invasive approach are needed.97 At present available oral anti-hyperglycemic agents have contrary reactions such as gastrointestinal disorders, hypersensitivity reactions, weight gain, and harm to main organs.98 If the number of DM patient reaches 366 million in 2030 from 171 million in 2000, novel medications will be needed to cure it.98 Treatments of type-II DM include improvement of insulin sensitivity99 or falling the proportion of carbohydrate absorption from the gastrointestinal tract. Although, the medicines used to treat DM have liver and renal dysfunction.100

2.1. α-Glycosidase and diabetes

α-Glycosidase is an enzyme101 of upper part of small intestine102 which is used for hydrolyzation of polysaccharides.103 Its competitive restraint is a helping tool for the administration of blood sugar regulation.104 Therefore, α-glycosidase inhibiting agents either synthetic or natural are considered as a drug that can lower type 2 diabetes. Till now, mainly three naturally occurring α-glycosidase inhibitors; voglibose, miglitol, and acarbose are remotely using for the control of diabetes.105–109 Insulin controls glucose of blood by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase110via signaling pathway. The major issue in type II diabetes is that the insulin-producing cells become resistant, which disrupts the insulin signaling pathway and impairs the ability of target tissues like lipids and muscles to absorb glucose.111 Correspondingly, any irregularity that occurs in the PI3K pathway influences the insulin signal transduction.112 Metabolic enzymes play essentials roles in biological systems, and their activation and suppression is associated with a variety of health problems.113 α-Glycosidase inhibition leads to the reduction of increased postprandial blood glucose levels.114

Polysaccharide of sugars are digested by the enzyme α-amylase to produce sub units of disaccharides and oligosaccharides which are subsequently degraded by the enzyme α-glycosidase to produce monosaccharide units.115 The inhibition of α-amylase and α-glycosidase hampers blood glucose levels rises afterward consumption of carbohydrates and can be a central approach in the administration of non-insulin-dependent diabetes.7 The two complex enzymes as maltase-glucoamylase and sucrose-isomaltase play role in the breakdown of alimentary sugars and starch to glucose.25 Few other auspicious targets that are considered for DM are dipeptidyl peptidase-4, insulin secretagogues, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR-γ), etc.,.116 α and β-Glycosidases are identified to catalyze the cleavage of glycosidic bonds.58 Different types of medicines were used to inhibit α-glycosidase, including acarbose, voglibose, and miglitol in the actual treatment of type-II diabetes mellitus. α-Glycosidase117 acetylcholinesterase (AChE), and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) enzymes have all been positively inhibited by sedative medications such hipnodex, ketamine midazolam, pental sodium and propofol.118 But, such inhibitors, which have a structural range, need tedious multi-steps in preparation.119 Recently, numerous synthetic agents have been stated to inhibit α-glycosidase.120 Appropriate care and early diabetes diagnosis should be prioritized in order to lessen the impact of diabetes on a person and society.121 Insulin is a vital hormone122 that plays a key role in the development of human tissues123 and leads to glucose homeostasis.124 The active molecule of insulin is a small protein that contains two chains α and β which have two disulfide bonds.125 An anabolic hormone insulin126 plays an imperious part in glucose metabolism, synthesis of protein,127 and translocation of important substances i.e., fatty acids, amino acids, and glucose along the biological membrane.128,129 The source of insulin secretion is pancreatic β-cells130 as a single-chain precursor, preproinsulin, along a signal sequence that allows its way to move into secretory vesicles.131 The proteolytic signal is removed by proteolytic manners then resultantly proinsulin is formed. In response, an increase in blood sugar, secreted proinsulin transformed into active insulin by certain proteases.

The major purpose of this review is to reveal new findings of heterocyclic synthetic agents for diabetes, along objective focused on novel synthesis approaches and antidiabetic potentials.

3. Synthetic agents as antidiabetics

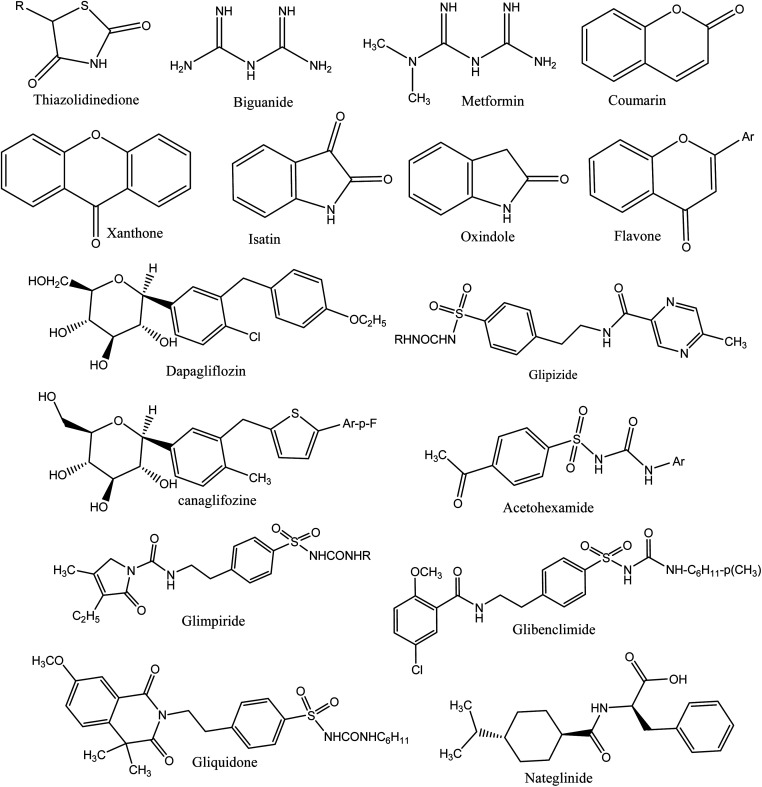

A number of synthetic drugs are available in market that had their great potential in order to cure diabetes as metformin,132 gliquidone,133 nateglinide,134 phenformin,135 rosiglitazone,136 glimepiride,137 pioglitazone,138 glibenclamide, exenatide,139 mitiglinide,140 gliclazide,141 chlorpropamide,142 glipizide,143 acetohexamide,144 tolbutamide,145 dapagliflozin,146 dulaglutide,147 liraglutide,148 glyburide,149 canagliflozin,150 and repaglinide.151 Some therapeutic agents are used to cure DM, classified as α-glycosidase inhibitors, thiazolidinediones,5,152 biguanides,153 sulfonylureas,154 and gliptins.155 Deazaxanthine156 and also various heterocyclic synthetic based pyrrole,157 pyrazole,158 pyrrolidine,159 oxindole,160 isatin,161 imidazole,162 benzimidazole,163 triazole,164 oxadiazole,165 thiazole,166 pyridine,167 piperazine,168 thiazolidinone, thiadiazole,169 benzofuran,170 benzoxazole,171 coumarin,172 flavone,173 piperidine,174 xanthone175 and pyrimidine.176 The core structures of antidiabetic moieties are given in Fig. 1. There are many synthetic agents used for diabetes that control glucose levels of plasma and to gain insulin-mimetic effects. Every class of drug has various mechanisms to control the blood glucose. Drugs are also connected with numerous negative effects; it is good to search for more and new drugs that can combat this disease more effectively with lower side effects.177

Fig. 1. The core structures of antidiabetic moieties.

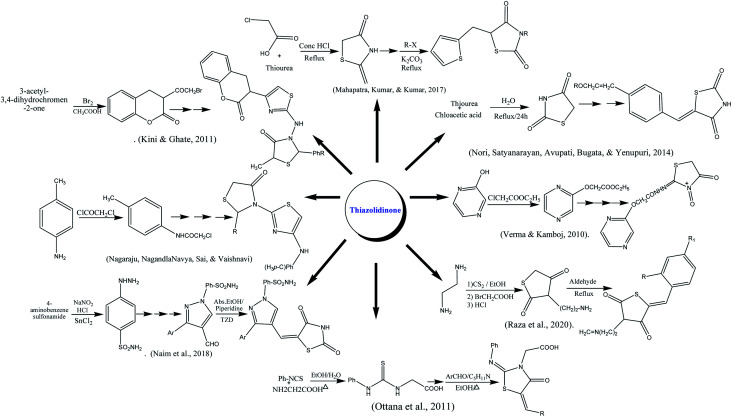

3.1. Synthesis of thiazolidinone

Ottana and co-authors reported the synthesis of thiazolidinone by multistep reaction using phenyl isothiocyanate and amino acetic acid as reactants. The reaction was carried out in acidic pH under reflux conditions. The resulting intermediate was further condensed undergoes Knoevenagel condensation with appropriate aromatic aldehydes on refluxing in ethanolic medium using piperidine as a base.178 The formulation of fused substituted thiazolidinone was reported from chloroacetic acid and thiourea under reflux in concentrated HCl. The thiazolidine-2,4-dione was further reacted with anhydrous sodium acetate in glacial acetic acid at 110–120 °C followed by Knoevenagel condensation with thiophene carboxaldehyde.179 Naim along colleagues reported the synthesis of thiazolidinedione derivatives. In the first step sulphanilamide in concentrated HCl, sodium nitrite and cold SnCl2 were stirred to form hydrazinyl benzene sulphonamide which was further converted into substituted pyrazole carbaldehydes and thiazolidinedione using different aldehydes and other reagents on reflux for 2–3 h.22 Thiazolidinone also synthesized from 3-acetyl coumarins as starting material which was reacted with Br2 in acetic acid at 25 °C to form 3-bromoacetyl coumarin which was allowed to reflux with substituted benzaldehyde resulting thiosemicarbazones up to 8 h to form intermediate in good yields. The last product was treated with thiolactic acid under reflux in ZnCl2 and dioxane to form end product. The structures of the compounds were characterized by IR, H-NMR.180 Knoevenagel condensation reaction was done between terephthalaldehyde and 1,3-thiazolidine-2,4-dione (prepared by refluxing chloroacetic acid and thiourea in water). Furthermore, base-catalyzed condensation with appropriate aromatic ketones and potassium hydroxide in the presence of ethanol to form a targeted product in good yield.181 A series of amino-derived thiazolidinone were prepared by the reaction of ethylenediamine with CS2 in the presence of triethylamine and ethanol, followed by a reaction with chloroacetic acid. The five-membered ring was obtained after stirring the former suspension in hot HCl for 5 min. The final products were synthesized by refluxing of basic skeleton with respective aldehyde in acidic medium.182 The pyrazolyl-based thiazolidinones were prepared by reacting p-toluidine, acetic acid, sodium acetate, and chloroacetyl chloride. The starting material was refluxed in a microwave synthesizer in the presence of thiourea. Schiff bases were formed using different aldehyde, upon thioglycolic addition and reflux under microwave synthesizer effective product was formed.183 The substituted oxo-thiazolidinones were prepared through electrophilic substitutions reaction by ethyl chloroacetate on hydroxy pyrazine on refluxing. The synthesized intermediate was further, aminated with alkyl isocyanate and chloroacetic acid yielded the end product.184

Imines were initially synthesized by reacting piperonylamine with substituted aromatic aldehydes. The imine was created quite practically at this point by just shaking the reactants, and was employed in the cyclization reaction. The most widely used technique for attaining 4-thiazolidinones, was employed as cyclization process by Refluxing in EtOH, and end product of piperonyl based 4-thiazolidinones (2a–i) derivatives were obtained.185

3.2. Antidiabetic activities of thiazolidinone

The inhibition of aldose reductase (bovine lens) was done via in vitro model using sorbinil and epalrestat as standard drugs. The more satisfactory inhibitors of aldose reductase (ALR2) were 5c and 5e compounds with IC50 values 0.25 mM and 1.32 mM respectively, owing to the presence of an acetic acid group that more actively interacted with the enzyme. A molecular modeling study was done with 5c and 5h compounds. ARL2 binding site can be divided into two different regions. The docking outcomes were anticipated that 5c compound forms very stable IDD594 conformation (ΔGAD4 = −9.14 kcal mol−1) along with more occupied cluster (size 60/100). However, standards sorbinil (ΔGAD4 = −7.27 kcal mol−1) and tolrestat (ΔGAD4 = −7.61 kcal mol−1) were not found with such a populated cluster.178

Insulin has a negative regulator known as protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) dephosphorylates. In vitro model, compounds 13 and 16 showed inhibition of PTP1B with IC50 7.31 μM and 8.73 μM respectively using in vitro model. The consequences directed those compounds with phenyl and methyl sulphonate substituted profoundly inhibited PTP1B. In silico inhibition of PTP1B by more active compounds 13 and 16 were performed. Hydrogen bonding was observed between the oxygen of C-4 carbonyl and Ser216, Ala217, and Arg221 amino acids of the active site in docking studies. Thiazolidinone nitrogen group has H-bonding contact with Arg221, along other interactions. Anti-hyperglycemic action of compounds checked by in vivo model after 7 days of administration. Almost 15.71 to 32.13% lowering of sugar level was seen in contrast to pioglitazone (31%). Compounds 13 and 16 decreased the blood sugar level by 32.13% and 30.22% respectively. Comparable results of SAR inferred that compounds having alkyl substitutions (–RSO3) at benzene ring improved anti-hyperglycemic activity with methyl and phenyl than bulky groups (Ar-NO2, 2,4,6-trimethylphenyl, 2-naphthyl, etc.).179

In vivo hypoglycemic activity was seen in STZ induced diabetic rats and almost all compounds exhibited PPAR-γ transactivation. Blood glucose level was checked after 1, 7, 15 days of drug administration. The decreasing order of lowering of glucose level for 7b, 7d and 7p was 138.7 ± 4.4 mg dL−1 > 137.4 ± 5.3 mg dL−1 > 134.1 ± 4.2 mg dL−1 respectively. The antihyperglycemic activity for standard pioglitazone was 132.2 ± 5.0 mg dL−1 although 7c, and 7f compounds exposed modest results in contrast to standard drugs. The SAR assay of compounds was focused on an aryl ring (substitution) that connected with the pyrazole core. Though, those compounds like 7d having halogen substitution at meta and para position were considered as more inhibitory compounds than others. Those compounds that had electron decreasing groups also reduced activity.22

Antihyperglycemic effect of compounds was determined by orally administering of Albino rats by synthesized coumarino thiazolo-thiazolidinones (4a–4j) and reference drug rosiglitazone (200 mcg kg−1) solution in Tween-80 while diabetes was induced by streptozocin. The blood sugar level was assessed by semi auto analyzer using a glucose estimation kit. Average glucose concentrations (mg day−1 ± SEM) for 4a, 4g, and 4h were 74.33 ± 1.156, 75.58 ± 1.375 and 75.63 ± 1.197 respectively, although the values of mean percentage change in antihyperglycemic activity were found to be 23.845 ± 2.134%, 27.567 ± 1.708% and 27.394 ± 2.564%, respectively.180

α-Glycosidase inhibitory activity of compounds was studied using phosphate buffer (50 mM) and PNP glycoside (1 mM) by incubation. The outcomes of the test were also compared with acarbose and type of inhibition was also assessed by plotting Lineweaver Burk plots using various concentrations of compounds. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of highly active compounds 5p and 5o was 6.56 ± 0.81 and 8.92 ± 0.21 μg mL−1 respectively. This inhibitory activity was substantially varied owing to different groups on α, β unsaturated ketone. Compounds showed a decreasing order of compounds 5p > 5n > 5m regarding to IC50 values (2,4-di-F-C6H3, IC50: 6.56 ± 0.81 μg mL−1) > (2,4-di-Cl-C6H3, IC50: 29.47 ± 0.32 μg mL−1) > (2-Cl-C6H4, IC50: 32.11 ± 0.33 μg mL−1) respectively.181

α-Glycosidase inhibition was done through in vitro assay. All derivatives showed inhibition (%) in a good range, however, 3a (77.7 ± 1.3%), b (88.1 ± 0.8%) whereas, 4c (74.8 ± 1.4%) compared to acarbose (89.3 ± 1.0%). The molecular modeling study was accomplished by the MOE program against PDB file of 3WEO (α-glycosidase). The values of E-score range between – 0.7121 to −5.2428, while, 3b, 4a and 4b docking score values are −4.9815, −5.2428 and −5.1597, respectively.182

The antidiabetic action of reported compounds was checked by tail tipping method for streptozocin-induced higher glucose levels in male Wistar rats. The promising antidiabetic activity of TZN-4 and TZN-8 was higher than the reference drug. Glibenclamide was a standard drug while streptozocin was used to induce diabetes. Streptozotocin solution was made by mixing with citrate buffer (0.05 M) maintained at a pH of 4.5 up to 24 h. After 72 h of administration, hyperglycemia condition was observed. A dose of just 100 mg kg−1 (b.w. of rat) of each compound was given and a reduction in sugar level was observed near to 50%. Compound TZN-2, TZN-4, and TZN-8 were reported with a certain decrease in mean ± SEM values from 300.5 ± 0.12 to 116.5 ± 5.90 mg dL−1, 213.5 ± 8.78 to 95.75 ± 6.06 mg dL−1, and 203.7 ± 13.79 to 101.5 ± 4.5 mg dL−1, respectively.183

The particular dosage (200 mg per kg of body weight) of oxo-thiazolidinone was administered and dexamethasone was used to induce hyperglycemic activity. The level of percentage of blood glucose reduction was maximum; 155.44% and 124.93% in case of compounds 1 and 2 respectively compared to control. However, intermediate reduction of 103.14%, 100.46% and 70.52% for compounds 3, 4, and 5 possessed activity respectively. Although, compounds 6, 7, and 8 were confirmed with the lowest antidiabetic potential of 33.88%, 50.00%, and 43.09% respectively against rosiglitazone (145.01%) as a standard drug. Compounds 1 and 2 also showed reduced insulinemia by the effect of dexamethasone and values mainly fall in a good range (3.000 ± 0.033 to 3.100 ± 0.057 milmL−1).184Scheme 1 depicted various synthesis protocols for thiazolidinone.

Scheme 1. Protocols for synthesis of thiazolidinone.

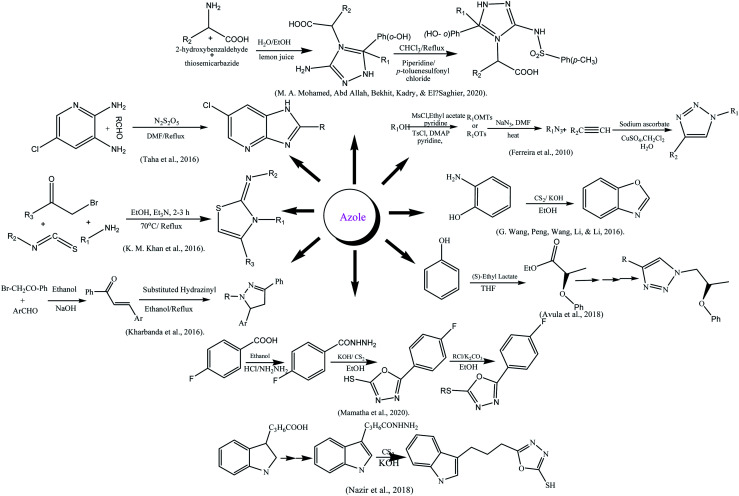

3.3. Synthesis of azole

The azole moiety was prepared according to Mitsunobu reaction by reacting 4-bromo-2-methoxy phenol and (S)-ethyl lactate in THF yielding ester that was converted into alcohol first, later on into azide after reacting with tosyl. The azide was converted into azole by 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition between azide and alkyne in presence of CuI.186 Ferreira and his colleague synthesized glycolated triazoles viz 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction. The structure elucidation was done with modern techniques.187 The substituted azoles were also synthesized by reacting p-halo acetophenones with aldehyde to form chalcones which on reaction with 2-hydrazinobenzothiazole-6-sulfonic acid amide.188 The substituted oxazole was synthesized from a cheaper source by the reaction of 2-aminophenol and carbon disulfide (CS2) in alkaline ethanol189 while, the synthesis of imidazopyridine was done by the reaction of different aldehydes and 5-chloropyridine-2,3-diamine.190 Similarly, azole-type compounds from a heterocyclic carboxylic acid; carboxylic acid was firstly converted into ester then into amide by reaction with hydrazine. The hydrazine was further treated with CS2 in a basic medium to yield azoles.191 The amino acid-coupled triazole derivatives were prepared using a green approach via multicomponent reaction. Salicylaldehyde was reacted with amino acids and thiosemicarbazide using lemon juice as a catalyst at 100 °C for 2 to 3 h which further reflux with p-toluenesulfonyl chloride in chloroform using piperidine catalyst and obtained end product.164 Mamatha and his colleagues reported the synthesis of mercapto oxadiazole using fluorobenzoic acid as starting agent, other chemical agents used were ethanol, conc. H2SO4, hydrazine hydrate, carbon disulfide, potassium hydroxide, and hydrochloric acid, DMF, and anhydrous K2CO3.192 A series of new thiazole derivatives was formulated by “one-pot” multicomponent reaction, by a variety of phenyl hydrazine treatment with aryl isothiocyanate in ethanol to get thiosemicarbazide intermediate which were further treated with phenacyl bromide to get the desired product.193

3.4. Antidiabetic activities of azoles

Compounds were given well inhibition (in vitro) of about 50% of α-glycosidase (14.2–218.1 μM) as contrasted to acarbose (IC50 = 942.0 μM). Enzyme Inhibition IC50 = 14.2 μM was possessed by 10b having methoxy substitution on phenyl, which is 67 times more active than acarbose while 10a with methyl group exhibited lower activity (IC50 = 83.8 μM) and had 5 times least inhibitory activities. Compound 10e with nitro, 10c with trifluoro phenyl, and 10d with fluorophenyl having IC50 values 21.6 μM, 28.7 μM and 56.2 μM, respectively. Molecular docking score of 10b, 10c and 10e was −13.6171, −12.0273 and −12.9459. Different substitutions had different effects on the interaction of the molecule with receptors as 10b exhibited with Arg312, Glu304, and Phe158 their bond lengths were 2.93, 3.25,3.63 Å, respectively, whereas, bond energies were ranged between −0.8, to −0.3.186

The inhibition of α-glycosidase was examined using the maltase enzyme (yeast) in comparison to acarbose as reference drug. All three types of β-d-ribosyl, α-d-galactosyl, and α-d-xylosyl triazoles were given maximum inhibition values by 500 μM while IC50 values are also in effective range (4 to 25 μM) against acarbose 108.8 ± 12.3 μmol L−1. The extreme percentage of inhibition seen in the case of 4f which was 99.5 ± 0.1% and lowest one for 7b 33.3 ± 46.1%. Others compounds with different substitutions at C-4 of triazole ring i.e., 4b (1-cyclohexenyl), 4e (phenoxymethyl), and 4g (1-cyclohexanol) were also depicted good inhibition. The glycolated triazole interatomic contacts with MAL12 were inspected using the Ligplot program and CSU/LPC server. A comparison of interactions was done between maltase (MAL12) and 4b, 4m (sterioisomers: 4mR and 4mS), and standard drug acarbose. The shortest contact distance and potent bonding were seen in the case of 4b, among nitrogen of triazole ring, Thr207, and OGI atom (2.6 Å) with contact area 39.8 Å2, for 4mR, H-bonding among pyran (C-14), His103, and CEI atom (3.4 Å) with contact area 20.6 Å2 and in 4ms hydrophobic interactions among pyran (C-13), Phe169 and CEI atom (2.4 Å) along contact area of 34.8 Å2.187

Compounds were docked over PPAR agonist and compared with the standard drug, rosiglitazone. Molecular docking studies of synthesized compounds against the PPAR target. Almost eighteen compounds possessed good docking score value than rosiglitazone (−5.72). Compound 7k (−10.06) was observed pi–pi contacts and hydrogen bonding with Arg280 and Lys261 while, compound 8g (−10.03) had various hydrogen bonding interactions with Lys261 residue. Synthesized compounds 7c, 7d, 7i–l, 8c, 8d, 8g, and 8h in transactivation test were found with intermediate alleviation of PPAR. Compounds 7k, 7j and 8h evaluated with elevation in PPAR transactivation 54.93%, 54.01 and 54.29%, respectively than rosiglitazone (81.68%). In STZ-induced diabetic rats, it was found that compounds 7i–l, 8g, and 8h caused lowering of blood plasma sugar level up to normal range on 15th day of the administration while, 7c, 7d, 8c, and 8d lowered glucose level nearly as rosiglitazone and glibenclamide. Compounds with p-chloroacetophenone are found more active than p-bromoacetophenone. Fluoro group on aryl ring increase activity than chloro, however, presence of alkyl and alkoxy on phenyl ring dropped biological activity.188

Substituted oxazole's 4a–4m were assessed for in vitro α-glycosidase (baker's yeast) inhibitory activity using acarbose as a positive control. The more effective inhibition was shown by 4f–4i, 4k and 4m (32.49 ± 0.17–120.24 ± 0.51 μM) as contrasted to acarbose (IC50 = 817.38 ± 6.27 μM). Different substitution at phenyl ring was found to play an imperative role in inhibition like for 4g with 4-phenoxy (IC50 = 32.49 ± 0.17). Electron-donors i.e., alkyl and alkoxy groups were decreased the rate of inhibition of enzymes in 4b, 4c, 4d, 4e, 4l, and 4j compared to electron-withdrawing groups 3-CF3, 4-F, 4-Cl and 2,4-Cl2 in respective compounds 4f, 4h, 4i, and 4k (IC50: 120.24 ± 0.51 to 44.4 ± 0.17 μM). A molecular simulations study was done using Saccharomyces cerevisiae extracted α-glycosidase over Autodock vina 1.1.2. and contacts illustrated visually by PyMOL 1.7.6. Dichlorophenyl substituted exhibited arene-cation contacts with Arg439 and π–π stacking interaction with Phe157 in both 4k and 4g, while benzoxazole rings with Phe157, Phe300, and Val303. Hydrogen bonding was observed with Asp349 by 4k and 4g (3.2–3.3 Å). Contrary to all, the terminal phenyl group of 4g also formed alkyl–π respective interactions with Tyr71 and Phe177 and made 4g more active compound.189

Antiglycation activities of all compounds (1–26) were estimated against rutin (IC50 = 294.46 ± 1.50 μM). The assay had revealed that hydroxyl group bearing compound depicted as best antiglycation agents i.e., 2, 3, 4, 6, 13 and 26 exhibited IC50 = 240.10 ± 2.40 μM–292.10 ± 3.20 μM. However, mono –OH compounds were found less active than di-OH compounds. Compounds with one hydroxyl group at ortho position even more inhibition potential than rutin except for 26 contained p-hydroxyl groups.190 Oxadiazole substituted compounds (8a–l) were showed inhibition of the α-glycosidase enzyme and IC50 values for compounds 8l, 8h, 8c, 8e, 8d, and 8f were 9.37 ± 0.03, 9.46 ± 0.03, 12.68 ± 0.04, 14.35 ± 0.02, 21.49 ± 0.04, and 21.64 ± 0.04 μM respectively that were more effective than acarbose (IC50 of 37.38 ± 0.12 μM). Compound 8I revealed percentage of inhibition 94.74 ± 0.11 at concentration of 0.5 mM. MOE dock program was used to accomplish modeling over α-glycosidase (baker's yeast) with PDB ID code: 3N04. In 8h indolic-NH proton and the carbonyl oxygen of acetamide form effective polar and acidic contacts with Asp73 and Arg404 with 1.80 and 2.01 angstroms, respectively. Although, these interactions were also in 8I with Lys422 and Asp420 at a distance of 2.25 Å and 2.15 Å, respectively which bind the compounds at active sites.191

Amino acid coupled triazoles were inhibited the α-amylase enzyme through in vitro assay using starch solution (0.1%) with sodium acetate buffer (pH = 4.8, 16 mM). The percentage of inhibition was ranged (80.0–75.43%). In vivo inhibition was seen male Wistar by orally administered triazoles compared to gliclazide as a standard drug. Afterward, 4 weeks of compound 3c (100 mg Kg−1), dropped the glucose level up to 49.2%, however, reference drug lowered sugar level about 54.4%.164

The in vitro inhibitory potential of compounds was also checked and GOD-POD method was employed to check the glucose liberation. For sucrose inhibition, compound benzothiazole 5 was found with 14% inhibition (5 mg mL−1), and 5a, 5b, 5f, and 5h showed moderate inhibition substituted with benzoyl, p-methyl benzoyl, heptyl, and p-chloro benzoyl substituents, while compound 5i (hexyl substituted) and 5j (acetate group) given lesser activity. The inhibition of α-glycosidase, 5e was detected with 48% inhibition while again 1% inhibition was shown by 5i and 5j. The compound 5e with coumarin was depicted 62% inhibition of α-amylase.192

α-Glycosidase inhibition potential of compounds was checked (IC50 = 9.06 ± 0.10–82.50 ± 1.70 μM) and compared to standard acarbose (IC50 = 38.25 ± 0.12 μM). Compound 12 with the presence of p-chloro aniline gives the greatest inhibition than others (IC50 = 9.06 ± 0.10 μM) and effective docking score (−11.8617). In benzamide-based azole 1 and 2 with p-Cl, p-CN at phenyl ring was given inhibitory values (IC50) from 22.40 ± 0.32 to 23.60 ± 0.39 μM due to electron-withdrawing groups, found that activity increased. While in diphenyl methanimine based azoles showed lesser activity than the other two substituted groups. Docking study of the compounds was exhibited for all three categories compounds. The compound showed 12 pi-interaction on the pocket via arene–arene moieties of chloro benzene and aniline with residues which depicted a good docking score −11.8617. In compound 17m-Cl on phenyl substitution lowered docking score (−9.9130). In methyl-substituted benzamide i.e., compound 1 imperative interaction was found with His279, Asn241, and Phe157 along with docking score (−12.5054). In diphenyl methenamine based azoles (19–24), compound 20 was most active with a docking score-13.6348.193Scheme 2 depicted various synthesis protocols for azole.

Scheme 2. Protocols for synthesis of azole.

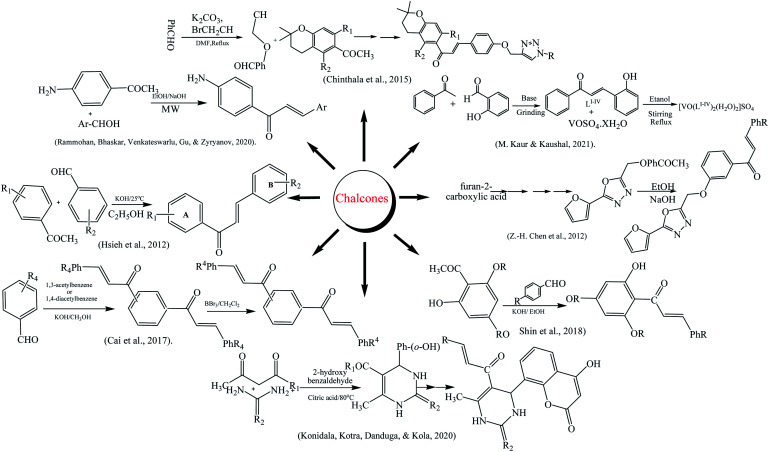

3.5. Synthesis of chalcones

The synthesis of chalcone was reported in a multistep reaction; firstly, 2,4-dihydroxy acetophenone and isoprene reacted to give chroman. Secondly, propargyl bromide was reacted with 4-hydroxy benzaldehyde in potassium carbonate by refluxing the mixture. The chalcone moiety was prepared by treating products of steps 1 and 2 via aldol condensation. The final product having triazole chalcone moiety was prepared by reacting chalcone with aromatic azide.194 Chen along coworkers reported that chalcone derivatives were synthesized using furoic acid as preparatory material. The desired products were prepared by the Claisen–Schmidt condensation.195 Kaur and Kaushal reported the synthesis of vanadyl chalcone complexes according to the method along with certain modifications. The ethanolic solution of both VOSO4·xH2O and chalcone ligands in a 1 : 2 molar ratio was mixed with constant stirring followed by dropwise addition of NaOH solution. The reaction mixture was further refluxed up to 10 h and green-colored precipitate of the complex was formed, which was filtered, and washed with ethanol.196 The synthesis of amino chalcones was accomplished by microwave-assisted synthesis.22 4-Aminoacetophenone and aromatic aldehyde in the equimolar ratio were dissolved in ethanol and basified with NaOH. The reaction mixture was irradiated under 180 microwave radiations for 15 min and the reaction completion was confirmed with TLC.197 Konidala and his colleagues reported the synthesis of coumarin–chalcone derivatives. Salicylaldehyde, acetylacetone, urea, thiourea, and citric acid were used as starting materials for their synthesis.198 The one-step synthesis of chalcone derivatives with high purity and yield was reported.199 Cai and co-authors narrated the synthesis of chalcones and bis-chalcones. The reaction starts from aromatic aldehyde, diacetyl benzene, and 50% KOH/CH3OH. The desired product was obtained by the demethylation of reaction intermediates in the presence of BBr3/CH2Cl2, respectively.200 The trihydroxy chalcone derivatives were prepared by reaction of acetophenone and benzaldehyde in ethanol (basic pH) in a round-bottomed flask under nitrogen atmosphere and stirred for 72 h at 25 °C. The end product was purified and recrystallized from ethanol to yield the chalcones.201 Tetrabromo-chalcones derivatives were obtained from previously reported methanoisoindole-substituted chalcones by adding 2 mol of molecular bromine in chloroform at 25 °C for 2 h, yielding the tetrabromo chalcone derivatives (2a–i). The recrystallization of compounds in CH2Cl2 was done in order to purify the end products. The structural analysis of compounds (2a–i) were also done using spectroscopic approaches.202 Chalcone-imide derivatives were synthesized starting from amino chalcone derivatives were synthesized using the well-known Claisen–Schmidt condensation method and on reaction with the benzaldehyde derivatives (2a–g) in base catalyzed medium about 3 h gave the amino chalcone derivatives (3a–g) in excellent yields. The reaction with maleic anhydride (4) in the presence of a few drops of NEt3 target crude solid product were obtained and was refined by recrystallisation using an ethanol and n-hexane solvent combination.203 When phloroglucinol and aqueous solution of acetic anhydride at 80 °C with methanesulfonic acid (MSA), compound 2 was synthesized. Following the successful synthesis of compound 2, compound 2 with dimethyl sulfate given compound 3 and in similar manner on reaction with benzaldehydes in a basic medium fluoro-substituted trischalcones in good yields were obtained.204 Chalcones derivatives were synthesized by bromination of 2,4,6-trimethoxyacetophenone to the 3-bromo-2,4,6-trimethoxyacetophenone (14) and an effective yield (95%) were obtained utilizing a general bromination method. The compound (14) in a base catalyzed mechanism with different reported benzaldehydes new chalcone derivatives were obtained.205

New halogenated chalcones (2a–n) were synthesized from starting from 6-acetyl-2(3H)-benzoxazolone that already synthesized from mixing of DMF and aluminum chloride solution that warmed at 45 °C for 5–10 min then acetyl chloride and 2-(3H)-benzoxazolone were added 80 °C for 3 h and after it poured out in cold water with HCl. The combination of 6-acetyl-2(3H) benzoxazolone and a suitable aldehyde in ethanol then an addition of an aqueous solution of KOH obtained end product.206

3.6. Antidiabetic activities of chalcones

α-Glycosidase inhibitory activity of rat intestine was measured using phosphate buffer and by maintaining pH up to 6.8. The sample solution was made in DMSO (5 mg mL−1) and incubated with crude α-glycosidase. The inhibition of the enzyme was measured by comparing the value of absorbance in control with the test sample solution. Regression analysis was applied to get IC50 values from average values of inhibition. The best inhibition activity was shown by compounds 4m, 4p, and 4s having IC50 values in the range of 67.77–102.10 μM. Structural features of these compounds exhibited that maximum inhibitory activity is correlated to a straight 5-C chain of triazole.194

The inhibition of PTP1B by synthesized chalcones was done using positive control; ursolic acid (IC50 = 3.40 ± 0.21 μM). Compounds 4e–4m had greater inhibitory potential, although, 4l given the IC50 value (3.12 ± 0.18 μM) and outstanding inhibition of 99.17% with 20 μg mL−1. The moderate inhibition of PTP1B was achieved by compound 4 (IC50 = 13.72 ± 1.53 μM). Few compounds (4a, 4b, 4d, and 4h) were also possessed lower inhibitory activity than lead compounds while, both 4c and 4n displayed no inhibition.195

The inhibition assays of amylase by iodine starch process and α-glycosidase using the reported p-NPG method were accomplished by chalcone complexes. All complexes shown a very active inhibition of α-glycosidase having IC50 value (7.35 μg mL−1) for complex-1, complex-2 (9.15 μg mL−1), complex-3 (3.26 μg mL−1) and complex-4 (8.51 μg mL−1) against standard acarbose. However, complex-3 confirmed good positive activity owing to the presence of m-NO2 derivative on the ligand. In amylase, complex-2 (IC50 = 302 μg mL−1) seen with very high activity that is also better than standard (IC50 = 388 μg mL−1). Modeling studies of all complexes showed that complex-3 against α-glycosidase showed maximum inhibition with effective binding energy (−10.02 kcal mol−1) due to hydrogen bonding (bond length = 2.92 Å) between the oxygen atom of the nitro group with Asp630 residue while complexes-1, 2 and 4 also showed moderate inhibition. In silico study of complexes with acarbose also supported the in vitro studies of compounds as complex-2 given best binding energy (−11.33 kcal mol−1) along with inhibition constant Ki (4.99 nM).196

Rats were treated with normal control, positive control with alloxan monohydrate, alloxan monohydrate followed by 0.025 units of insulin, and also with chalcones of 3a–3j. A glucose analyzer (Accu Chek, Roche diabetes care, USA) was used to measure glucose and it was revealed that sugar level was raise up to 301.12 ± 1.85. However, chalcones reduced this level up to 50–29%. Compound 3c reduced sugar level 50% (150.60 ± 1.50 mg dL−1), moderate inhibition by 3e (39%) 160.60 ± 1.58 mg dL−1 while, others 3d; 35% (170.60 ± 1.44 mg dL−1) 3b 33% (176.40 ± 1.90 mg dL−1) and 3f; 31% (181.10 ± 2.40 mg dL−1). The docking experiment was assessed with DPP-IV, PPAR, aldose reductase, and α-glycosidase and chalcones. Compounds showed more interactions with α-glycosidase, compound 3c presented pi–pi interaction with Trp376 (3.4 Å), 3i had polar types of interaction with Asp616 (3.3 Å), pi–pi interactions with Trp376 (3.6 Å) and Phe649 (3.5 Å) and 3b has polar bond interaction with Asp616 (4.1 Å) and pi–pi contact with Phe376 (3.5 Å).197

A molecular modeling study was accomplished over VLife MDS 4.6 software against insulin receptor (1IR3). Chalcones DCCU 13, DCCT 13, and DUUC 8 exhibited binding scores −83.15, −82.72, and −82.26 respectively, in contrast to standard drug metformin having a docking score of −68.64. The interactions of the hybrids were also compared to internal ligand ANP which showed hydrophobic interactions while hybrids interacted by H-bonding, hydrophobic, and van der Waals interactions. Diabetes mellitus was induced in rats by intraperitoneal administration of streptozotocin (STZ). Antidiabetic activities for DCCU 13 and DCCT 13 (15–30 mg kg−1) were assessed by fasting blood glucose level (BGL), change in glucose concentration up to 7 days of administration checked values found for BGL were also in a good range (91.50 ± 6.90–150.00 ± 9.60 mg dL−1).198

In vitro anti diabetic activity was performed in adipocytes 3T3-L1 culture medium. Both pioglitazone and rosiglitazone were employed as positive controls. Derivatives of chalcones 2b, 4a, 5b, 6a, 6b, and 6c with groups at C-2 of A ring displayed effective activity and sugar concentration (210 to 236 mg dL−1). Chalcones 6e and 6g having iodo group at C-3 on A-ring were also exhibited effective values of 238 mg dL−1 and 233 mg dL−1 respectively. Although, the presence of the alkoxy group on the B ring also promoted the positive action of chalcones. An analysis of multi-way ANOVA examination was achieved using JMP 9.0.0 deduced that various substitution augmented the glucose uptake activity (p = 0.0016).199

α-Glycosidase activity was checked using in vitro model of HepG-2 cells and cultured mainly in serum free medium using 1-deoxynojirimycin as standard (IC50 = 21.3 ± 8.7 μM). Type of inhibition was also demonstrated using Lineweavere Burk. Maximum inhibition was shown by 2k with IC50 = 1.0 μM. The presence of methoxy group as substitution showed lesser solubility and lowered the inhibition activity of compounds 1a–1m and inhibition ration found at 40 μM. In 2c position of –OH group at C-4 instead of C-3 of A-ring showed more inhibition (IC50 = 13.4 ± 2.7 μM) than 2d (IC50 = 42.0 ± 6.0 μM) due to donor hydrogen bond effect. While, in bischalcones number of hydroxyl group increases more inhibitory action was seen for 2j and 2I with IC50 values 5.5 ± 1.2 μM and 6.5 ± 0.4 μM, respectively. Intramolecular hydrogen bonding lower the interactions with enzyme and inhibitory activity diminished.200

Antihyperglycemic effect was observed in mice after administration of 4 weeks of chalcones. A blood glucose tolerance test revealed that chalcone 13 was found to be active in blood glucose maintenance. Serum-free fatty acid levels and fat deposition were also notably reduced. Skeletal muscles of mice were also subjected to a TEM study that also disclosed that no fat accretion was detected. Chalcone 13 was also inhibited the activity of PTP1b by interacting strongly with it and giving a value of IC50 = 0.92 mM L−1.201Scheme 3 depicted various synthesis protocols for chalcones.

Scheme 3. Protocols for synthesis of chalcones.

In this work, the IC50 values for hCA I were determined to be between 13.58 and 18.72 nM, whereas those for hCA II were in between 9.62 and 12.60 nM. All of the tested compounds' (2a–i) were extremely effective hCA I inhibitors, with Ki values ranging between 11.30 ± 2.01 and 21.22 ± 5.63 nM, and hCA II inhibitors, with Ki values ranging between 8.20 ± 1.62 and 12.86 ± 1.98 nM. The standard drug AZA found with IC50 values for hCA I and II were 40.45 and 24.16 nM, respectively.202

Chalcone-imide derivatives (5a, 5c–g) effectively inhibited the cytosolic hCA I with Ki values found to be from 426.47 ± 72.10 and 699.58 ± 115.8 nM. This isoform's best inhibition was identified with 5d, having a Ki value of 426.47 ± 72.10 nM. Acetazolamide (AZA) was designated broadly for CA inhibitor due to its more inhibitory action against CAs and its Ki value of 977.77 ± 227.4 nM against hCA I. Chalcone-imide derivatives (5a, 5c–g) showed Ki values for hCA II that ranged from 214.92 ± 2.172 to 532.21 ± 81.52 nM. The standard drug AZA normally prescribed to cure following ailments as epilepsy, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, altitude sickness, glaucoma, glaucoma, central sleep apnea and cystinuria had also intermediate potency for CA II inhibition.203

Novel fluoro-substituted tris-chalcones and their derivatives (5a–5i) revealed IC50 and Ki values between 8.30 ± 3.80–32.30 ± 4.02 nM for α-glycosidase, which is found on cells lining of gut and hydrolyzes monosaccharides to be absorbed via the intestine. The α-glycosidase assay findings revealed that all new fluoro-substituted tris-chalcones derivatives (5a–5i) exhibited more efficient α-glycosidase inhibitory characteristics than acarbose (IC50: 22.8 mM). Also obtained were very effective Ki values for chalcone 5c, with a Ki value of 8.30 ± 3.80 nM.204

α-Glycosidase inhibitory action of new chalcone derivatives (5–12) was demonstrated with Ki values ranging from 12.54 ± 4.16 to 35.22 ± 2.10 nM. The findings also concluded that all chalcone derivatives were more efficient at inhibiting α-glycosidase than acarbose (IC50: 22.800 mM), a commonly used α-glycosidase inhibitor. The Ki values ranging from 16.24 ± 5.10 to 40.96 ± 8.95 nM for novel chalcone derivatives demonstrated low nanomolar inhibition levels against hCA I. Acetazolamide (AZA), a sulfonamide-based reference inhibitor, had a Ki value of 141.02 ± 50.84. The hCA II isoenzyme is inhibited by new chalcones (5–12), in a same manner as to CA I and Ki values were shown in the range of 29.61 ± 5.65–67.15 ± 16.21 nM.205 Derivates of chalcones (2a–n) actively inhibited the human carbonic anhydrase with IC50 (μM) values of 27.2–73.7 for hCA I and 29.1–72.6 for hCA II, despite typical AZA values of 16.6 for hCA I and 8.4 for hCA II. The values of Ki (μM) versus hCA I and hCA II vary from 30.5 ± 11.3–65.5 ± 25.6 and 7.3 ± 1.8–58.8 ± 12.3, respectively. The lowest value is 2g 27.2 and the highest is 2d 29.1.206

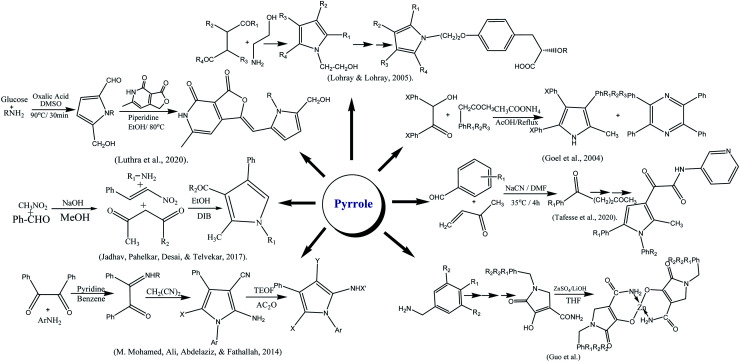

3.7. Synthesis of pyrroles

The derivatives of pyrrole were synthesized by reaction of amine, 1,3-dicarbonyl and nitro styrene in ethanol by refluxing for 4 h in the presence of diacetoxyiodo benzene.207 Similarly, Lohray and coworkers reported the synthesis of novel pyrrole-containing compounds by the reaction of 4-disubstituted compounds with amino ethanol. They have further evaluated their hypoglycemic and hypotriglyceridemic potential.208 The zinc complexes of pyrrole-3-carboxamide were reported by complexing N-trialkylated acrylamide with ZnSO4 in the presence of LiOH.209 The pyrrole-2-carbaldehydes were synthesized via Malliard reaction in which glucose in presence of oxalic acid was treated with diverse amines at 90 °C for 30 min. The final product was obtained by reacting furopyridine-dione with piperidine.210 Pyrrole was also synthesized via a series of reactions; 2,3-dicarbonyl was reacted with phenylamine in benzene at 80 ∘C for 9 h. After cooling the reaction mixture, malononitrile was added, followed by a catalytic amount of pyridine portion-wise and left to reflex till solid formed. Pyrrole derivatization was done by triethyl orthoformate and acetic anhydride.211 Goel and fellows reported the preparation of methyl triphenyl pyrroles by refluxing benzoin, benzyl methyl ketone, and ammonium acetate mixture in acetic acid. A minor tetraphenyl pyrazine as a byproduct was also probably formed by self-condensation of benzoin with ammonium acetate.212 Pyrrole moiety was also prepared from amine, nitro styrene, and 1,3-dicarbonyl compound in the ethanolic medium by stirring at 25 °C up to 10 min. The reaction mixture, was refluxed in DIB for 4 h. However, nitro styrene's were synthesized from corresponding aromatic aldehydes and nitromethane by considering the reported method.207 Tafesse and co-workers narrated the synthesis of pyrrole started from substituted aldehyde and methyl vinyl ketone. The other chemical reagents that used were NaCN, dimethylformamide, p-toluene sulfonic acid and ethanol. Pyrrole derivatives prepared by reaction of pyrrole with oxalyl chloride, dichloromethane, triethylamine and N,N-dimethyl aminopyridine at 0 °C.213 A class of advantageous heterocyclic of new pyrrole and enamine and their derivatives easily synthesized employing two-component condensation, that actually comprise of glycyl acid and the ethyl ether, these substances with various functional groups successfully used in medicine. First, under the catalytic action of ytterbium(iii) trifluoromethanesulfonate, (Z)-ethyl 2-(3-oxo-1,3-diphenylprop-1-enylamino)acetate (1) was synthesized as reaction of glycine ethyl ester hydrochloride and dibenzoylmethane occurred. The subject of investigation was then chosen to be enamine that then was mixed with tert-BuOK after being dissolved in butyl alcohol and crystals of ethyl-3,5-diphenyl-1H-pyrrole2 carboxylate are the end product (2) that easily attained.214 1,3-Dicarbonyl compounds were employed as the starting reactant in the synthesis process. These chemicals were reacted with oxalyl chloride to produce furan-2,3-diones employing the Wittig reaction. The final step was the optimally controlled synthesis of the end product as novel pyrrole-sulfonamide derivatives, from sulfa medicines and furan-3-one. The target compounds (5a–i) were synthesized in the last stage by refluxing using 1-propanol solvent for 6 h. The process of product formation consists of only two steps. The amino group attacks at C-5 of the furan ring in the first step, which causes ring opening and the cyclization process synthesized the pyrrole ring in the second step. The novel compounds (5a–5i) have recrystallization yields that vary from 76 to 88%.215

3.8. Antidiabetic activities of pyrrole

The α-amylase inhibitory assay of pyrrole was accomplished, aliphatic amines-based pyrroles and branched amino acids-based pyrroles; 3, 7, 12, and 18 exhibited effective IC50 values. Compounds 7 and 12 were found to be the best inhibitors of α-amylase and α-glycosidase. The α-amylase and α-glycosidase IC50 (μmol mL−1) for 3; 0.430 ± 0.82 and 0.861 ± 0.35, 7; 0.365 ± 0.58 and 0.804 ± 0.18, 12; 0.408 ± 0.11 and 0.779 ± 0.259, 18; 0.456 ± 0.42 and 0.840 ± 0.17 respectively. Molecular docking study of the 3 on α-amylase (PDB ID-1OSE) cleared that oxygen of carboxylic group showed H-bonding with Hip305, pyrrole ring interacted with Trp58, Trp59, Glu63, Leu165, and Val163 though, phenyl ring showed contacts with cavity residues Leu162, Hie101, Glu233, Ala198, Ash197, and Arg195. Molecular modeling of 3 with α-glycosidase displayed a very strong interaction of the oxygen atom of the carboxylic group also with Lys348. However, 3 had docking scores −7.995 and −8.236 while 7 had −7.65 and −7.896 against α-amylase and glycosidase respectively.207

The antihyperglycemic effect of compounds was shown by compounds 29, 31, and 34 in mice (mg kg−1) after 6 days of continuous administration. Blood glucose reduction percentage was found for respective compounds as 61.9 ± 1.7%, 58.2 ± 1.5%, and 65 ± 2%. The highest percentage of triglyceride reduction was seen in the case of 34 that was about 54.9 ± 3.2%.208

The insulin-mimetic activity over adipose tissues of male Wistar rats was performed. To check activity, pyrrole–zinc(ii) complexes (10a–d) inhibited adipose cells free fatty acid release that was stimulated with epinephrine except 10e due to non-solubility in the assay medium. Complexes acted as potent hypoglycemic agents and IC50 values of Zn complex 10a, 10b, 10c, 10d and ZnSO4 were 0.37 mM, 0.36 mM, 0.39 mM, 0.41 mM and 0.44 mM as respective.216

In vitro (α-glycosidase) inhibitory activity revealed that compound 3k was found to be four times more potent with IC50 of 0.56 μM against acarbose (IC50 = 2.1 μM) while, 3d shown value 4.4 μM. Compounds 3a and 3f–i had value ranged 20–33 μM although, other compounds showed no activity. The presence of pyridine dione, pyrrolidine increased activity and indolyl ring at C-3 to the pyrrolidinyl nitrogen (3d) also had higher activity values than 3e with phenyl. It was also seen that aromatic moiety at the pyrrolidinyl nitrogen 3f–i compared to aliphatic 3b and c had higher inhibitory potential. Functional group p-CO2Et on the aromatic ring in 3k effect activity, p-halo and p-hydroxy at the para3g–i and o-CH3 in 3j almost did not affect the activity of compounds. The Gold program was used to dock 3k over the α-glycosidase and value of binding (ΔG) was −15.53 kcal mol−1. Four hydrogen bonding interactions are seen between protein and compound 3k.210

Pyrroles-based compounds were assessed by STZ and SLM using glimepiride as a reference drug. In comparison to untreated normal control compound Ia, Ic, and Ie were lowered 17.4%, 18%, and 16.7%, respectively in SLM, although in STZ compared to diabetic group reduced induced glucose level 33.3%, 35.3%, and 29.5%, respectively. In contrast to glimepiride Ia, Ic, and Ie showed a significantly decline in the blood sugar level 109.4%, 116.2%, and 97%, respectively.211

In vivo antihyperglycemic activity in male Sprague Dawley rats was determined using a sucrose loaded model (SLM) and a streptozotocin loaded model (STZ). In SLM and STZ compound 3d having F group at phenyl ring exhibited blood sugar levels up to 50% and 34.7% respectively, while 3c with CF3 substitution at phenyl ring given 40.8% and 25.1%. In 3h and 3i with methoxy group also on phenyl ring given respective 27.8% and 20.3% inhibitory activity in SLM.212

α-Glycosidase inhibition was done by incubation of compounds 5a–i in potassium phosphate buffer. Compound 5e (111 ± 2 μM) showed higher activity due electron withdrawing substitution as 2,4-dichloro 5f substitution and 3,4-dichloro 5g on phenyl ring connected to pyrrole moiety and IC50 values were 573 ± 12 μM and 639 ± 13 μM respectively than standard acarbose 750 ± 9 μM. The presence of 2,4-dichloro 5a (IC50 = 196 ± 10 μM) compared to 2,5-dichloro 5b (IC50 = 663 ± 11 μM) decreased the activity of compound up to three folds. Prior to this, presence of phenyl substitution on pyrrole ring 5h (IC50 = 494 ± 10 μM) and methyl in 5i (IC50 = 673 ± 12 μM) decreased the activity. Molecular docking was accomplished using auto dock Tools version 1.5.6. In compound 5e (binding energy −4.27 kcal mol−1) and 5a (binding free energy = −3.17 kcal mol−1) carbonyl oxygen of acetamide formed hydrogen bonding with His280 and Arg442 respectively. 5-Phenyl ring also showed pi–pi contacts with Tyr158 in 5e, while, Phe303, and Phe178 interact with the 5a. π–anion interactions were observed between pyridine and Asp307 in 5e and Glu411 in 5a. Standard acarbose exhibited binding free energy of 2.47 kcal mol−1.213Scheme 4 depicted various synthesis protocols for pyrrole.

Scheme 4. Protocols for synthesis of pyrrole.

The hCA I inhibitory constant Ki value for compound 1 is 85.07 ± 10.04 μM and for 2 is 47.21 ± 5.06 μM. Although, the results against CA II, and the inhibitory constant of 1 found at 66.01 ± 8.47 μM and of 2 was 35.77 ± 3.53 μM, compounds 1 and 2 exhibited less than inhibitory activity in contrast with the standard medication AZA (27.04 ± 2.43 μM). Compound 1 demonstrated less inhibitory action than AZA, according to the Ki values: 35.51 ± 3.32 μM. Additionally, compound 2 produced findings that were very similar to those of AZA, a drug used to treat a number of common diseases, including glaucoma. The goal of the current investigation was to examine substances that inhibit α-glycosidase activity, synthetic compounds have Ki values of 1 63.76 ± 7.12 μM and for 2 93.54 ± 11.20 μM. Both substances demonstrated weaker inhibitory effects than acarbose based on the IC50 and Ki values 45.21 ± 5.34 μM.214

The cytosolic hCA I and hCA II isoforms as well as AChE were evaluated against their inhibition by newly pyrrole-3-one derivatives (5a–i). The inhibitor concentrations (IC50) were 10.66 to 30.13 nM and their inhibitory constant values in between 1.20 ± 0.19 to 44.21 ± 1.09 nM, all pyrrole-3-one derivative medicines containing sulfur groups efficiently inhibited hCA I. These pyrrole derivatives effectively inhibited hCA II, with IC50 values 8.15–22.35 nM and Ki in between the 8.93 ± 1.58 to 46.86 ± 8.41 nM. In addition, the studied compounds demonstrated the best inhibition when compared to AZA (Ki: 47.32 3.21 nM).215

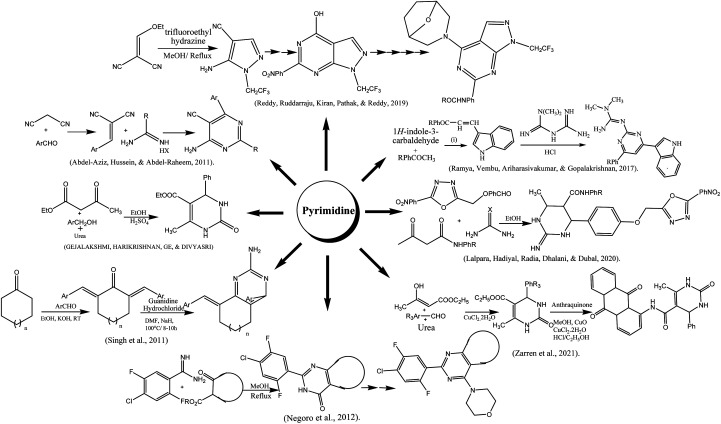

3.9. Pyrimidine

The indole-based pyrimidine derivatives were synthesized by condensing of indole-3-carboxaldehyde with p-substituted acetophenones followed by treating with metformin hydrochloride to form the final product.217 A simple method for the preparation of amino pyrimidine derivatives from malononitrile and benzaldehyde was reported. The precipitates formed in water were acidified with hydrochloric acid, filtered, and recrystallized in ethanol.218 Reddy and co-authors reported the synthesis of the pyrimidine-containing pyrazole group. Trifluoro ethyl hydrazine and malononitrile were reacted in methanol at reflux condition for 3 h to obtain intermediate that was used for final product with good yield after a series of steps such as amide formation, cyclization, chlorinated, nucleophilic substitution, reduction, and coupling.219 The synthesis of tetrahydropyrmidine was done viz Bignelli condensation followed by microwave irradiation. To a mixture of benzaldehyde, urea, and ethyl acetoacetate in a round bottom flask, concentrated hydrochloride acid was added and poured into a china dish for microwave 180 watts irradiation for one minute.220 Zarren and his colleagues reported the anthraquinone-derived pyrimidine derivative by one-pot relay method using a catalytic amount of copper chloride and cupric oxide in methanolic medium. The reaction mixture of both compounds was allowed to stir up to 30 min at ambient temperature.221 Biginelli condensation was also used for the preparation of hydroxy pyrimidine (HPM) derivatives. The reaction of oxadiazole contains aldehyde moiety with substituted acetoacetanilide and urea derivatives in acidic ethanol under microwave irradiation (200 W) up to 25 min.222 The reaction of various bis-benzylidene cycloheptanones and bis-benzylidene cyclohexanones with guanidine hydrochloride was conducted in the presence of NaH and DMF as a solvent to obtain the amino pyrimidine in moderate to good yields.223 Negoro and coworkers reported the synthesis of morpholino pyrimidine derivatives. The reaction was started by condensation of substituted benzamidine with cyclic β-keto ester followed by chlorination using phosphorous oxychloride resulting in the formation of 4-chloro-fused-pyrimidines. These compounds were subjected to substitution with morpholine to acquire the final product.224 To start with thiourea and using trifluoracetic acid as a catalyst, it was simple to synthesized derivatives of pyrimidine thiones. As the reaction was complete, white crystals of the final product were attained.225 Tetrahydropyrimidine carboxylates and their derivatives were synthesized by Sujayev and colleagues using benzaldehyde, urea, 2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl acetoacetate in ethanol and acetyl acetone as solvents (3 : 1). Desired products were then got through a reaction with epichlorohydrin and 1,2-epoxobutane. Utilizing a sulifol UV 254 plate to monitor the reaction, and compound's structural details were clarified by an X-ray diffractogram analysis.226 Similar methods were used to synthesize cyclic thioureas (1–8) by reacting substituted p-tolualdehyde, p-anisaldehyde, o-tolualdehyde, salicylaldehyde, and benzaldehyde with methylene active substances such β-diketones and thiourea. At 60–75 °C, the three-component condensation processes took place in 2.5–3.0 hours. The synthesized compounds were crystalline in nature, and 1H, and 13C-NMR spectroscopic methods as well as elemental analyses were used to determine their structural details. In the region of 3370–3040 cm−1 areas of the IR spectra of the produced compounds (1–8), NH bond valence vibrations were detected.227 In acetylacetone and ethyl alcohol, pyrimidine-thiones are dissolved, and then drop by drop 1,2-epoxypropane (1,2-epoxobutane) is added, AlCl3 catalyst is used and heated at 60–65 °C. 4-Chlorobutanol (G–K) is added to the pyrimidine-thione solution and mixed for 10–15 minutes. The mixture is shaked for 1–3 hours at 70–78 °C.228 For synthesis of N-heterocyclic salts, firstly, 1,2-diaminoethane, 1,3-diaminopropane, and 1,4-diaminobutane were condensed with two molar equivalents of the aromatic aldehydes in ethanol to create the Schiff bases that later on converted to equivalent benzylic diamines by the reduction of sodium borohydride in methanol. Finally, by cyclizing triethyl orthoformate in the presence of ammonium chloride, N,N′-dialkylalkanediamines were transformed into 1,3-dialkylazolium salts. Following, purification, pure products were recovered as colorless solids with effective yields (60 to 87%).229

3.10. Antidiabetic activities of pyrimidines

Docking outputs of compounds (11a–g) were achieved using CDOCKER against glucokinase (LV4S). From results, the synthesized compound showed good docker energy; 11a (−11.36) and 11b (−8.77 kcal mol−1) and 11g (−9.13 kcal mol−1) respectively while, metformin had 21.60 kcal mol−1. Compound 11a had strong contacts with residues Pro66, Arg63, Ilf211, Val452, Thr65, Gln98, Tyr215, Met235, and Met210. Compounds 4-indolylphenyl-6-arylpyrimidine-2-imines (11a–g) have been assessed for inhibition of α-amylase and α-glycosidase by in vitro methods. The maximum inhibition of α-glycosidase was depicted by 11a and 11g with IC50 values 55.98 μg mL−1 and 56.27 μg mL−1 while against α-amylase values were 49.50 μg mL−1, and 49.90 μg mL−1 respectively. STZ induced diabetic albino Wistar rats were used and evaluated through in vivo anti diabetic models. The synthesized compounds (11a–g) were administrated till 28 days. However, glucose level was observed 152.23 mg dL−1 with 11a, 170.21 mg dL−1 for 11e, 167.45 mg dL−1 for 11f and 173.44 mg dL−1 for 11g compared to metformin (154.23 mg dL−1). Compounds 11b, 11c and 11d showed less inhibition as 182.5 ± 11 mg dL−1, 180.232 ± 12 mg dL−1, 181.32 ± 12 mg dL−1, respectively.217

Compound 5d–l, and 6d–l were assessed for antidiabetic effect, induced by alloxan monohydrate in rats via determined the percentage reduction in average glucose after seven days of administration in contrast to standard metformin. Compounds 5d–f, exhibited no decrease in blood glucose, 6d–f reduced up to 15–21% and 5g–i showed about 6–15% decrease. Compound 6g–I with 2-cyclohexylamino-4-oxopyrimidines fasting blood glucose up to 34% excluding 6g due to absence of substituents on phenyl ring at position 6 decrease glucose just 2%. In compounds 5j–l, particularly 5k having p-chlorophenyl at position 6 decrease in glucose by about 45%. In 6j–l especially in 6l with p-methylphenyl substitution, about 46% decreased. Hence, 5k and 6l are normally considered as lead compounds against metformin.218

Novel pyrimidine compounds 8a–I were analyzed for in vitro α-amylase inhibition and IC50 values in between 1.60 ± 0.48 to 2.04 ± 1.20 μM in contrast to reference acarbose (1.73 ± 0.05 μM). Compound 8i was found to be more active due to o-nitro and m-fluoro-substitution on the phenyl ring. Comparison studies have been carried out among the analogues (8f–k) by substituting the nitro group at the ortho, meta, and para on the phenyl ring. The presence of p-nitro on aryl ring in 8k activity increased 1/3-fold than 8a. Most active compounds were 8d, 8f, 8g, 8h, 8i, 8j, and 8k had IC50 values of 1.77 ± 2.84, 1.65 ± 0.45, 1.66 ± 2.24, 1.73 ± 0.37, 1.60 ± 0.48, 1.75 ± 0.36, and 1.64 ± 0.03 μM, respectively. The effective antidiabetic activity was accompanied by compound 8d and 8k in alloxan-induced diabetic Wistar rats having glucose higher than 270 mg dL−1. Compound 8d with 25 mg kg−1 and 50 mg kg−1 dose after 2 h of administration on 5th hrs 198.6 ± 18.6 and 182.2 ± 13.7 respectively, while for 8k values were 204.2 ± 18.6 and 193.2 ± 18.7 against standard glibenclamide (174.1 ± 13.9). In silico modeling studies were exhibited (8a–l) on α-amylase (PDB : 1HNY) against standard acarbose. The 8d with m-nitro and o-methyl group had 59.46 gold score. It formed H-bonding with Gly351 and also hydrophobic contacts with His305, Tyr62, Gly304, Asp356, and Trp59. However, compound 8k had also a score 48.12, which showed hydrophobic contacts with Thr163, Tyr62, Trp59, Ile51, Leu165, along H-bonding with Glu233, Arg195 and Asp197.219

In molecular docking study, substituted pyrimidine showed interactions with insulin receptor. The amino acid residues for binding were Asp1150, Asp1083, His1081, Met1079, Ser1006, Glu1108, Glu1077 with respective ligand pose energy (kcal mol−1); −8.03805, −7.58741, −7.51747, −9.13544, −7.62575, −5.44869, −5.00426 respectively. The ligand and receptor pose energy values were obtained and Pymol viewer was used to view every single binding site interaction.220 Antidiabetic activity of G1–G4 was determined for in vitro α-amylase inhibition and acarbose showed 61.70% inhibition. Compound G2 was found with the highest 57.80% inhibition along IC50 24.23 μg mL−1 although G1, G4, and G3 exhibited 40.96%, 39.36%, and 37.94%, respectively. Docking studies were accomplished for G1–G4 against human pancreatic α-amylase and docking score found in effective ranges (−119.48 to −131.536 Kcal mol−1) although, the acarbose docking score was −111.57 kcal mol−1. G2 (−184.273 kcal mol−1) showed contacts with Thr163 and His305 while bond length values were 2.602 Å and 2.44 Å respectively. In compound G4 oxygen atom of aldehyde showed contacts with Ile235 (2.89 Å). Compound G2 showed the best inhibition of α-amylase than others.221

Synthesized compounds 4a–j and 5a–j were assessed using various concentrations (50–125 lg mL−1) for in vitro α-amylase inhibition and acarbose considered as reference drug. Compounds 4d, 4g, 4i, 4j, 5b and 5f that exhibited IC50 values (lg mL−1) in good ranges; 71.46, 72.41, 72.27, 70.62, 72.79, and 72.10 respectively that nearer to 69.71 for acarbose.222 Aminopyrimidines (21–40) were showed a good percentage of inhibition for α-glycosidase (13–72%) and glycogen phosphorylase (10–40%) and by excluding 31, 34, 35, and 37 had moderate to good inhibitory potential. SAR study of the compounds revealed that phenyl ring substitution in arylidene showed good inhibition of glycosidase enzyme, i.e., compounds 24, 25, 29 and 36 with p-bromo (71.8%), p-chloro (72.8%), p-benzyloxy (53.1%), and p-methoxy (63.2%), respectively, against α-glycosidase but also found more effective against glycogen phosphorylase. A 2-naphthyl substituent compound 40, showed also inhibition of both glycogen phosphorylase and α-glycosidase and 2-aminopyrimidine analogs with fused cyclohexyl compared to cycloheptyl more active against α-glycosidase.223

Pyrimidine derivatives were acted as GPR119 agonist, compound 12a with cyclopentane fused-pyrimidine ring and 4-chloro-2,5-difluorophenyl moiety behaved as a strong GPR119 agonist while 14a due to structural modification having 5,7-dihydrothieno[3,4-d]pyrimidine 6,6-dioxide found to be about 10-fold enhanced activity as a GPR119 agonistic. However, substitution at 4-position in pyrimidine (16b), enhanced not only activity but also improved glucose tolerance. Compound 16b along its derivatives considered potential therapeutic agents for type-II diabetes mellitus.224Scheme 5 depicted various synthesis protocols for pyrimidine.

Scheme 5. Protocols for synthesis of pyrimidine.

Pyrimidine thiones were assayed for the inhibition of both cytosolic human CA (I and II) and acetazolamide AZA used as a standard drug. Compound 3 CA exhibited maximum inhibition constant Ki (pM) against hCA I and hCA II as 312.6 ± 61.1 and 273.6 ± 41.4 respectively, although reference drug showed values at 369.4 ± 68.5 and 271.8 ± 54.5.225

Tetrahydropyrimidine-5-carboxylates derivatives (1–3) were given effective inhibition of cytosolic hCA I and Ki (nM) values in a range between of 429.24 ± 87.89–539.30 ± 106.70. In all derivatives compound 2 possesses good effective inhibitory activity due to following functional as: –C O, –C S, –NH, –OH, Cl, –CH2, and –CH3 have highest value of Ki 429.24 ± 87.89 nM and standard AZA given 281.33 ± 55.33. However, against hCA II synthesized compounds showed Ki value in a limit of 391.86 ± 40.16–530.80 ± 103.60 nM. Hand, AZA values found at 202.70 ± 162.5 nM.226

Cyclic thioureas (1–8) is generally inhibited the hCA I isoenzyme and their lower Ki values found between 47.40 ± 4.43–77.68 ± 3.69 nM in contrast to standard acetazolamide (AZA), 289.22 ± 2.60 nM. The inhibition hCA II that naturally present in red blood cells, compounds depicted with Ki values 30.63 ± 7.62 to 76.06 ± 3.15 nM and among which the cyclic thiourea 2 was found to be best inhibitor of hCA II with Ki: 30.63 ± 7.62 nM value.227

The new pyrimidine-thiones (A–K) compounds under investigation suppressed release of hCA I, with Ki values ranging from 4.3 1.0 to 9.1 ± 2.8 nM, a Ki value of 4.3 ± 1.0 nM compound (K) also proved to have the strongest hCA I inhibitory potential. Acetazolamide (AZA), a commonly prescribed medication, with a Ki value of 13.9 ± 5.1 nM. The new pyrimidine–thiones (A–K) compounds examined here effectively suppressed the hCA II as well these substances had Ki values that ranged from 4.2 ± 1.1 to 14.1 ± 4.4 nM, suggesting that they substantially inhibited hCA II. These numbers surpass those of the therapeutically utilized medication AZA, which has a Ki of 18.1 ± 8.5 nM.228

The newly synthesized tetrahydropyrimidinium, tetrahydrodiazepinium salt and imidazolinium, and derivatives (5a–l) inhibited the hCA I with Ki value found between 1.88 ± 0.83 and 50.66 ± 12.35 nM, however, 5f and 5e recorded the most potent hCA I inhibition abilities with a Ki value of 1.88 ± 0.83 and 2.16 ± 0.47 nM, respectively. Although Ki values ranging from 20.18 ± 6.78 nM to 124.04 ± 46.23 nM found for synthesized compounds to inhibit hCA II. The Ki values of freshly created molecules are superior to those of the AZA standard compound Ki with 187.07 ± 16.55 nM. The CA isoenzyme was significantly inhibited by compounds 5g and 5h, with Ki values of 20.18 ± 6.78 and 24.23 ± 5.55 nM, respectively.229

4. Future perspectives of synthetic compounds

As a health concern, one of the utmost fatal diseases known as diabetes, prevailing around worldwide and natural resources are not enough for the complete eradication of this disease. In light of this review, positive diabetic actions of synthetic analogs are summarized in a well-organized way. Although, the search for novel antidiabetic compounds along their wanted pharmacological profiles is an endless job regarding to drug discovery. Emergent heterocyclic equivalents with prior physiochemical, and pharmacodynamic characteristics might be valuable moieties for future studies. The accessible literature survey on thiazolidinone, azole, pyrrole, chalcone, and pyrimidine analogues is comparatively at ease for pharmaceutical chemists to pursue with coherent synthesis and advance treatment. The general addition, substitution, and elimination (functional groups) reaction process are also operative approaches for scheming new drug molecules. The aforementioned antihyperglycemic activities either by in vitro and in vivo mechanism and drug-receptor or enzyme interaction depicted that just how can ligand adjustment improved mechanistic studies of researchers. In near days, toxicological investigations and reversibility parameters with selectivity effect of novel heterocyclic compounds are likely to predict their opposing and therapeutic effects towards diabetics.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Havrylyuk D. et al., Synthesis and anticancer activity evaluation of 4-thiazolidinones containing benzothiazole moiety. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010;45(11):5012–5021. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Bocanegra L. et al., α-Glucosidase inhibitors from Vauquelinia corymbosa. Molecules. 2015;20(8):15330–15342. doi: 10.3390/molecules200815330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey G. Kim M. S. Lian J. F. Patient compliance and persistence with antihyperglycemic drug regimens: evaluation of a medicaid patient population with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin. Ther. 2001;23(8):1311–1320. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roslin M. S. et al., The rationale for a duodenal switch as the primary surgical treatment of advanced type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic disease. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2015;11(3):704–710. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raza M. A. et al., Synthesis, Single Crystal, In-Silico and In-Vitro Assessment of the Thiazolidinones. J. Mol. Struct. 2022:132384. [Google Scholar]

- Kassa S. B. et al., Effects of some phenolic compounds on the inhibition of α-glycosidase enzyme-immobilized on Pluronic® F127 micelles: An in vitro and in silico study. Colloids Surf., A. 2022;632:127839. [Google Scholar]

- al-Hassan N. Definition of diabetes mellitus. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2003;53(492):567. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogru M. Katakami C. Inoue M. Tear function and ocular surface changes in noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(3):586–592. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00599-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S. M.-W. Bonventre J. V. Acute kidney injury and progression of diabetic kidney disease. Adv. Chron. Kidney Dis. 2018;25(2):166–180. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannel W. B. Hjortland M. Castelli W. P. Role of diabetes in congestive heart failure: the Framingham study. Am. J. Cardiol. 1974;34(1):29–34. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(74)90089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozougwu J. et al., The pathogenesis and pathophysiology of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. 2013;4(4):46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Durmaz L. et al., Screening of Carbonic Anhydrase, Acetylcholinesterase, Butyrylcholinesterase, and α-Glycosidase Enzyme Inhibition Effects and Antioxidant Activity of Coumestrol. Molecules. 2022;27(10):3091. doi: 10.3390/molecules27103091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini V. Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus. World J. Diabetes. 2010;1(3):68. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v1.i3.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amos A. F. McCarty D. J. Zimmet P. The rising global burden of diabetes and its complications: estimates and projections to the year 2010. Diabetic Med. 1997;14(S5):S7–S85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faroqi L. et al., Evaluating the clinical implementation of structured exercise: a randomized controlled trial among non-insulin dependent type II diabetics. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2018;74:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naim M. J. et al., Synthesis, molecular docking and anti-diabetic evaluation of 2,4-thiazolidinedione based amide derivatives. Bioorg. Chem. 2017;73:24–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karalliedde J. Gnudi L. Diabetes mellitus, a complex and heterogeneous disease, and the role of insulin resistance as a determinant of diabetic kidney disease. Nephrol., Dial., Transplant. 2016;31(2):206–213. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillausseau P.-J. et al., Abnormalities in insulin secretion in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. 2008;34:S43–S48. doi: 10.1016/S1262-3636(08)73394-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalkwijk C. G. Stehouwer C. D. Vascular complications in diabetes mellitus: the role of endothelial dysfunction. Clin. Sci. 2005;109(2):143–159. doi: 10.1042/CS20050025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cade W. T. Diabetes-related microvascular and macrovascular diseases in the physical therapy setting. Phys. Ther. 2008;88(11):1322–1335. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat M. Belagali S. Guanidinyl benzothiazole derivatives: Synthesis and structure activity relationship studies of a novel series of potential antimicrobial and antioxidants. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2016;42(7):6195–6208. [Google Scholar]

- Naim M. J. et al., Design, synthesis and molecular docking of thiazolidinedione based benzene sulphonamide derivatives containing pyrazole core as potential anti-diabetic agents. Bioorg. Chem. 2018;76:98–112. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2017.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.-C. et al., Isoliquiritigenin selectively inhibits H2 histamine receptor signaling. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006;70(2):493–500. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.023226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw J. E. Sicree R. A. Zimmet P. Z. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2010;87(1):4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghani U. Re-exploring promising α-glucosidase inhibitors for potential development into oral anti-diabetic drugs: Finding needle in the haystack. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015;103:133–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guariguata L. et al., Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014;103(2):137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailes B. K. Diabetes mellitus and its chronic complications. AORN J. 2002;76(2):265–282. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)61065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinlay J. Marceau L. US public health and the 21st century: diabetes mellitus. Lancet. 2000;356(9231):757–761. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02641-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babik B. et al., Diabetes mellitus: endothelial dysfunction and changes in hemostasis. Orv. Hetil. 2018;159(33):1335–1345. doi: 10.1556/650.2018.31130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ighodaro O. Adeosun A. Vascular complications in diabetes mellitus. Kidney. 2018;4:16–19. [Google Scholar]