Key Points

Question

Is there an association between maternal antipsychotic prescription fill during pregnancy and standardized test scores in school-aged children?

Findings

In this register-based cohort study comprising 667 517 schoolchildren in Denmark, maternal antipsychotic prescription filled during pregnancy was not statistically significantly associated with standardized test scores (range, 1-100) in Danish language (adjusted test score difference, 0.5) or in mathematics (adjusted test score difference, 0.4) compared with children whose mothers did not fill prescriptions for antipsychotics during pregnancy.

Meaning

Among Danish school-aged children, maternal antipsychotic prescription during pregnancy did not appear to be associated with children’s standardized test scores.

Abstract

Importance

An increasing number of individuals fill antipsychotic prescriptions during pregnancy, and concerns have been raised about prenatal antipsychotic exposure on neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Objective

To examine whether maternal prescription fill for antipsychotics during pregnancy was associated with performance in standardized tests among schoolchildren.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This register-based cohort study included 667 517 children born in Denmark from January 1, 1997, to December 31, 2009, and who were attending public primary and lower secondary school. All children had completed at least 1 language (Danish) or mathematics test as part of the Danish National School Test Program between 2010 and 2018. Data were analyzed from November 1, 2021, to March 31, 2022.

Exposures

Antipsychotic prescriptions filled by pregnant individuals were obtained from the Danish National Prescription Register.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Differences in standardized test scores (range, 1-100; higher scores indicate better test results) in language and mathematics between children of mothers with and without antipsychotic prescription fills during pregnancy were estimated using linear regression models. Seven sensitivity analyses, including a sibling-controlled analysis, were performed.

Results

Of the 667 517 children included (51.2% males), 1442 (0.2%) children were born to mothers filling an antipsychotic prescription during pregnancy. The mean (SD) age of children at the time of testing spanned from 8.9 (0.4) years in grade 2 to 14.9 (0.4) years in grade 8. Maternal prescription fill for antipsychotics was not associated with performance in language (crude mean test score: 50.0 [95% CI, 49.1-50.9] for the exposed children vs 55.4 [95% CI, 55.4-55.5] for the unexposed children; adjusted difference, 0.5 [95% CI, −0.8 to 1.7]) or in mathematics (crude mean test score: 48.1 [95% CI, 47.0-49.3] for the exposed children vs 56.1 [95% CI, 56.1-56.2] for the unexposed children; adjusted difference, 0.4 [95% CI, −1.0 to 1.8]). There was no evidence that results were modified by the timing of filling prescriptions, classes (first-generation and second-generation) of antipsychotics, or the most commonly prescribed antipsychotic monotherapies, including chlorprotixene, flupentixol, olanzapine, zuclopenthixol, quetiapine, perphenazine, and methotrimeprazine. The results remained robust across sensitivity analyses, including sibling-controlled analyses, negative control exposures analyses, and probabilistic bias analyses.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this register-based cohort study, maternal prescription fill for antipsychotics during pregnancy did not appear to be associated with standardized test scores in the offspring. The findings provide further reassuring data on offspring neurodevelopmental outcomes associated with antipsychotic treatment during pregnancy.

This cohort study examines the association between maternal antipsychotic prescriptions filled during pregnancy and performance in standardized tests of mathematics and language among schoolchildren in Denmark.

Introduction

Antipsychotics are the first-line pharmacotherapy for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder but are also frequently prescribed for depression and anxiety disorders.1,2 These disorders often emerge during late adolescence and young adulthood and thus coincide with childbearing age.3 In recent years, the number of individuals filling antipsychotic prescriptions during pregnancy has increased in most countries, with the prevalence varying from 0.3% to 4.6%.4,5,6

Antipsychotics cross the placenta, accumulate in the fetal tissue,7 and interact with dopamine D2 receptors that play an essential role in the proliferation and differentiation of neural progenitor cells in the developing fetus.8 Antipsychotics may thus potentially reduce dopaminergic neurotransmission8,9 and have subsequent adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes. Most previous human studies are limited to children aged 5 years or younger and generally suggest transient neurodevelopmental delays and deficits following prenatal exposure to antipsychotics.10 Four recent studies demonstrated little or no increased long-term risks associated with prenatal antipsychotic exposure in neurodevelopmental disorders.11,12,13,14 One study has evaluated potential cognitive outcomes, which may capture more subtle neurodevelopmental impairment.15 To our knowledge, school performance, which is associated with cognitive ability, has not been investigated in this context so far.

We aimed to examine the association between maternal antipsychotic prescriptions filled during pregnancy and school performance in children. Furthermore, we investigated whether any associations differed by the timing of prescription and classes (first-generation and second-generation) of antipsychotics.

Methods

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency. No informed consent is required for a register-based study using anonymized data according to Danish legislation.

Study Population

We conducted a cohort study using Danish nationwide registers (see eMethods in the Supplement). The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

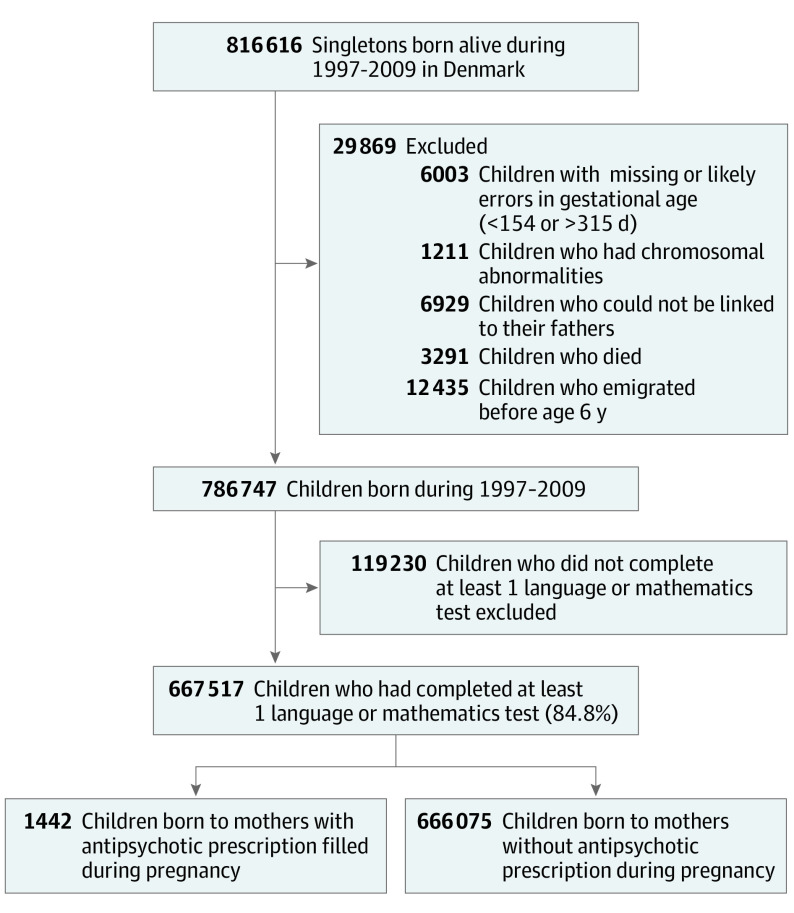

All residents in Denmark are assigned a unique personal identification number recorded in the Civil Registration System,16 which enables individual-level data linkage among registers. We identified all singletons born alive in Denmark between 1997 and 2009 (n = 816 616) from the Medical Birth Registry.17 We excluded 6003 children with missing or unlikely gestational age; 1211 with chromosomal abnormalities identified within the first year from the National Patient Register18; 6929 children with missing linkage to their fathers; and 15 726 children who emigrated or died before age 6 years, the age of school entry in Denmark. From the remaining 786 747 children, we identified 667 517 (84.8%) children who had completed 1 or more language or mathematics tests as part of the National School Test Program19 (Figure). Of the 15.2% of children with no school tests, 12.6% attended private schools with no request for testing, 1.0% were exempted from testing, 0.2% attended special education schools, and 1.3% did not test for unknown reasons.

Figure. Flowchart Illustrating the Identification of the Study Population.

Maternal Antipsychotic Prescriptions Filled During Pregnancy

Information on antipsychotic prescriptions was extracted from the National Prescription Registry.20 We defined prenatal antipsychotic exposure as maternal filling of a prescription for any antipsychotic (the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical [ATC] classification code N05A), excluding lithium (ATC: N05AN01) because of different pharmacological actions, between 30 days before pregnancy and the delivery date. We estimated the start of pregnancy from the recorded gestational age at birth, determined by ultrasonography scan17,21 or the first day of the last menstrual period when ultrasonographic data were unavailable.

Outcomes

School performance was assessed using standardized tests in language (Danish) and mathematics completed from 2010 to 2018 as part of the National School Test Program.19 Language tests are carried out in grades 2, 4, 6, and 8, and mathematics in grades 3, 6, and 8. The tests are computer-based standardized adaptive tests and were initially scored following a Rasch model and subsequently mapped into a score ranging from 1 to 100 with higher scores indicating better test results.19 The scores were norm-based and reflected the student’s performance as a percentile of the nationwide distribution of scores in 2010, the first year of testing, except for mathematics in grade 8, which was introduced in 2018 (see eFigure 1 in the Supplement for standardized score distribution by test years).

Potential Confounders

We identified potential confounders a priori using directed acyclic graphs. The majority were maternal characteristics: age; primiparity; smoking during pregnancy; marital status; calendar year of delivery; highest completed education in the year of delivery22; and measures of morbidity, including psychiatric diagnosis before delivery, inpatient and outpatient psychiatric treatment from 1 year before pregnancy until delivery, self-harm before delivery, and filled prescriptions for antiseizure medications (ATC: N03A), anxiolytics (ATC: N05B), lithium (ATC: N05AN01), and antidepressants (ATC: N06A) during pregnancy. Additionally, we adjusted for parental country of origin, paternal psychiatric diagnosis before delivery, paternal self-harm before delivery, and paternal income in the year of birth (quintiles, adjusted to 2009 prices) to account for shared familial factors. Information on maternal and paternal psychiatric history was obtained from the Psychiatric Central Research Register.23 Individuals with more than 1 recorded diagnosis were categorized into 4 hierarchical groups (eTable 1 in the Supplement), reflecting the organization of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision diagnostic system. Codes used to define self-harm are listed in the eMethods in the Supplement and were derived from a validated coding algorithm.24 A graphical depiction of the timeline for assessing exposure, outcomes, and confounders is provided in eFigure 2 in the Supplement.

Statistical Analysis

We assessed differences in school test performance between children of mothers with and without antipsychotic prescription fills during pregnancy. We used multiple linear regression models to calculate the difference (Δ) of scores with 95% CIs based on 2-sided hypothesis testing. A significance threshold of .05 (2-sided) was used. A child could have multiple tests during the study period, and we used generalized estimating equations with robust standard errors to account for the dependencies among test scores of each child. We examined the associations in 2 models: the baseline model included sex, grade, parental country of origin, and birth year, and the fully adjusted model included all confounding covariates in Table 1. All analyses were done separately for language and mathematics. We also dichotomized test results by applying official cutoffs19 to define below-average performance (1-35) vs average and above average (36-100) and repeated the analyses using logistic regression with generalized estimating equations.

Table 1. Characteristics of Study Population According to Maternal Antipsychotic Prescription During Pregnancy.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Exposed group (n = 1442) | Unexposed group (n = 666 075) | |

| Maternal age at delivery, y | ||

| <25 | 273 (18.9) | 91 348 (13.7) |

| 25-34 | 798 (55.3) | 469 745 (70.5) |

| ≥35 | 371 (25.7) | 104 982 (15.8) |

| Primiparity | 600 (41.6) | 286 317 (43.0) |

| Parental country of origin | ||

| Danish parents | 1033 (71.6) | 549 398 (82.5) |

| 1 Danish parent | 161 (11.2) | 63 717 (9.6) |

| Non-Danish parents | 248 (17.2) | 52 960 (8.0) |

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy | ||

| Yes | 585 (40.6) | 111 361 (16.7) |

| No | 679 (47.1) | 469 592 (70.5) |

| Missing | 178 (12.3) | 85 122 (12.8) |

| Maternal marital status in the year of delivery | ||

| Married or cohabiting | 1023 (70.9) | 585 799 (87.9) |

| Single, divorced, or widowed, including missinga | 419 (29.1) | 80 276 (12.1) |

| Maternal highest education in the year of delivery | ||

| Mandatory school | 716 (49.7) | 134 792 (20.2) |

| High school or vocational school | 475 (32.9) | 289 342 (43.4) |

| College or university | 206 (14.3) | 226 325 (34.0) |

| Missing | 45 (3.1) | 15 616 (2.3) |

| Maternal psychiatric diagnosis before delivery | ||

| Psychotic disorders | 449 (31.1) | 1981 (0.3) |

| Mood disorders | 242 (16.8) | 7521 (1.1) |

| Neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders | 210 (14.6) | 15 383 (2.3) |

| Other mental illnesses | 108 (7.5) | 8989 (1.3) |

| No psychiatric diagnosis | 433 (30.0) | 632 201 (94.9) |

| Maternal inpatient psychiatric treatment from 1 y before pregnancy to delivery | 339 (23.5) | 1657 (0.2) |

| Maternal outpatient psychiatric treatment from 1 y before pregnancy to delivery | 677 (46.9) | 8153 (1.2) |

| Maternal self-harm before delivery | 343 (23.8) | 13 866 (2.1) |

| Maternal prescription fill for other medications during pregnancy | ||

| Antiseizure medications | 112 (7.8) | 2683 (0.4) |

| Antidepressants | 669 (46.4) | 11 189 (1.7) |

| Anxiolytics | 308 (21.4) | 4521 (0.7) |

| Lithium | 20 (1.4) | 50 (<0.1) |

| Paternal psychiatric diagnosis before delivery | ||

| Psychotic disorders | 69 (4.8) | 2797 (0.4) |

| Mood disorders | 37 (2.6) | 3683 (0.6) |

| Neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders | 73 (5.1) | 8091 (1.2) |

| Other mental illnesses | 62 (4.3) | 7374 (1.1) |

| No psychiatric diagnosis | 1201 (83.3) | 644 130 (96.7) |

| Paternal income by quintile in the year of delivery | ||

| Lowest | 560 (38.8) | 129 177 (19.4) |

| Second | 322 (22.3) | 135 795 (20.4) |

| Third | 251 (17.4) | 136 107 (20.4) |

| Fourth | 177 (12.3) | 134 420 (20.2) |

| Highest | 124 (8.6) | 128 500 (19.3) |

| Missing | 8 (0.6) | 2076 (0.3) |

| Paternal self-harm before delivery | 97 (6.7) | 9662 (1.5) |

| Birth year | ||

| 1997-2000 | 365 (25.3) | 212 363 (31.9) |

| 2001-2004 | 390 (27.0) | 209 928 (31.5) |

| 2005-2009 | 687 (47.6) | 243 784 (36.6) |

| Sex of child | ||

| Male | 724 (50.2) | 340 804 (51.2) |

| Female | 718 (49.8) | 325 271 (48.8) |

A total of 5247 (0.8%) children were born to mothers with missing marital status at delivery.

To examine whether the associations between antipsychotic exposure and school performance differed by the timing of exposure, we divided the exposure window into first trimester only (30 days before pregnancy to 90 days of pregnancy); second or third trimester only (91-180 days of pregnancy or 181 days of pregnancy to childbirth); and more than 1 trimester. We considered a child exposed to antipsychotics in a specific trimester if the date of dispensation occurred in the trimester or when the duration of a prescription overlapped that trimester. We calculated the duration of prescriptions by multiplying the number of defined daily doses per package by the number of packages dispensed.

We considered maternal prescription fills for any antipsychotics combined, by classes (first-generation antipsychotics only and second-generation antipsychotics only), and by the most commonly prescribed antipsychotics in monotherapy to account for their differences in mechanisms of action.25,26 See detailed ATC codes for individual antipsychotics in eTable 2 in the Supplement. In the combined analyses of all antipsychotics, we further analyzed the association with school performance by interactions with sex, grade, birth year, test year, and parental country of origin, respectively.

Approximately 15.0% of the values were missing for any potential confounders, and we performed a multiple imputation analysis with 20 imputed data sets using the fully conditional specification method for imputing missing values27 and used the imputed data sets in the adjusted models. All analyses were done using SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). Data were analyzed from November 1, 2021, to March 31, 2022.

Sensitivity Analyses

We performed 7 sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the findings. First and second, to account for confounding by indication, we compared children who were exposed to antipsychotics with children whose mothers filled antipsychotic prescriptions from 1 year to 30 days before pregnancy but not during pregnancy. Furthermore, we investigated the associations stratified by maternal psychiatric diagnosis before delivery. Third, we performed discordant sibling comparisons to assess confounding by shared environmental or genetic factors. We limited the analyses to children with both language and mathematics tests in grade 6 with at least 1 sibling exposed to antipsychotic prescription and at least 1 sibling unexposed. Linear regression models with maternal fixed effects were used to analyze the data. Fourth, we used paternal antipsychotic prescription fills during pregnancy as the negative exposure control. We hypothesized that if there were any potential effects of intrauterine exposure to antipsychotics, antipsychotic prescriptions filled by mothers should have a greater influence than prescriptions filled by fathers in the same period.28 Fifth, to reduce misclassification of antipsychotic exposure, we redefined the exposure as filling 2 or more antipsychotic prescriptions during pregnancy and reclassified individuals with 1 prescription as unexposed. Sixth, to further quantify the influences of misclassification of antipsychotic exposure, we conducted a probabilistic bias analysis by performing 150 Monte Carlo simulations.29 We assigned a sensitivity of 35% to 45% and 99.8% to 100% specificity on the basis of a 40% adherence rate30 and the prevalence of antipsychotic prescriptions filled during pregnancy observed in the present study (0.2%). Seventh, the prevalence of maternal antipsychotic prescriptions filled during pregnancy and parental previous psychiatric diagnosis and self-harm were similar among children with and without a school test, but other parental demographics were slightly different, as shown in eTable 3 in the Supplement. We used inverse probability weighting to assess whether the results were biased because of nonparticipation in the standardized tests. The weights were based on a logistic regression model, including all covariates listed in Table 1 and maternal antipsychotic prescriptions filled during pregnancy. Furthermore, we investigated the association between mothers filling antipsychotic prescriptions and offspring neurodevelopmental disorders in children with and without school tests to examine the potential outcome of nonparticipation selection on an alternative neurodevelopmental measure (which was available for both excluded and included children).

Results

The study population comprised 667 517 children (51.2% males) with 1 608 204 language tests and 908 281 mathematics tests, with a median (range) of 2 (0-4) tests for language and 1 (0-3) test for mathematics per child. The mean (SD) age of children at the time of testing spanned from 8.9 (0.4) years in grade 2 to 14.9 (0.4) years in grade 8. Overall, 1442 (0.2%) children were born to mothers filling an antipsychotic prescription during pregnancy: 965 (0.1%) first-generation antipsychotics only and 332 (<0.1%) second-generation antipsychotics only. Among children of mothers filling an antipsychotic prescription during pregnancy (abbreviated as exposed children), a larger proportion had a mother who was aged younger than 25 years or 35 years and older, smoked during pregnancy, had shorter education, had a psychiatric history, received inpatient and outpatient psychiatric treatment before or during pregnancy, and had a previous history of self-harm (Table 1).

The mean test scores in language were 50.0 (95% CI, 49.1-50.9) for exposed children and 55.4 (95% CI, 55.4-55.5) for unexposed children. The mean test scores in mathematics were 48.1 (95% CI, 47.0-49.3) for exposed children and 56.1 (95% CI, 56.1-56.2) for unexposed children. Differences were statistically significant for both language and mathematics in the baseline model, showing exposed children scoring lower than unexposed, but shifted toward the null in the fully adjusted models, with Δadj of 0.5 (95% CI, −0.8 to 1.7) in language and 0.4 (95% CI, −1.0 to 1.8) in mathematics (Table 2). School performance did not differ by exposure timing. Maternal antipsychotic prescription filled only in the first trimester was not associated with poor school performance compared with unexposed children: the Δadj were −0.2 (95% CI, −1.8 to 1.5) in language and −0.5 (95% CI, −2.3 to 1.3) in mathematics. The corresponding Δadj were 2.5 (95% CI, −0.7 to 5.7) in language and −0.2 (95% CI, −4.2 to 3.7) in mathematics among children whose mothers filled antipsychotic prescriptions in the second or third trimester only.

Table 2. Difference in Mean Test Scores Between Children Born to Mothers With and Without Antipsychotic Prescription Fill During Pregnancy According to the Timing of Antipsychotics.

| Antipsychotic prescription during pregnancy | Language tests | Mathematics tests | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of tests/children | Mean score (95% CI) | Basic adjusted, Δ (95% CI)a | Fully adjusted, Δ (95% CI)b | No. of tests/children | Mean score (95% CI) | Basic adjusted, Δ (95% CI)a | Fully adjusted, Δ (95% CI)b | |

| No antipsychotic prescription | 1 605 026/663 009 | 55.4 (55.4 to 55.5) | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 906 477/594 085 | 56.1 (56.1 to 56.2) | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] |

| Any antipsychotic prescription | 3178/1433 | 50.0 (49.1 to 50.9) | −4.2 (−5.4 to −3.0) | 0.5 (−0.8 to 1.7) | 1804/1237 | 48.1 (47.0 to 49.3) | −7.0 (−8.4 to −5.6) | 0.4 (−1.0 to 1.8) |

| Timing of antipsychotic prescription | ||||||||

| Only first trimester | 1607/739 | 49.0 (47.8 to 50.1) | −5.4 (−7.1 to −3.7) | −0.2 (−1.8 to 1.5) | 888/626 | 46.9 (45.3 to 48.6) | −8.3 (−10.2 to −6.4) | −0.5 (−2.3 to 1.3) |

| Second or third trimester only | 389/170 | 52.9 (50.4 to 55.3) | −0.8 (−4.2 to 2.6) | 2.5 (−0.7 to 5.7) | 226/152 | 48.5 (45.2 to 51.9) | −5.9 (−10.0 to −1.8) | −0.2 (−4.2 to 3.7) |

| Multiple trimesters | 1182/524 | 50.5 (49.0 to 51.9) | −3.7 (−5.8 to −1.6) | 0.6 (−1.4 to 2.7) | 690/459 | 49.6 (47.6 to 51.6) | −5.7 (−8.1 to −3.3) | 1.8 (−0.6 to 4.2) |

Abbreviation: Δ, the difference in mean test score.

Basic adjustment for sex, calendar year of birth, parental country of origin, and grade.

Additional adjustment for maternal age at delivery; primiparity; maternal smoking during pregnancy; maternal marital status; maternal highest completed education in the year of delivery; maternal psychiatric diagnosis at delivery; maternal inpatient and outpatient psychiatric treatment from 1 year before pregnancy until delivery; maternal and paternal self-harm before delivery; maternal filling prescriptions for antiseizure medications, anxiolytics, lithium, and antidepressants during pregnancy; paternal psychiatric diagnosis at delivery; and paternal income in the year of delivery.

Compared with unexposed children, the mean test score differences were Δadj, 0.3 (95% CI, −1.1 to 1.7) in language and Δadj, 0.0 (95% CI, −1.6 to 1.6) in mathematics for children whose mothers filled only first-generation antipsychotic prescriptions, and Δadj, −0.8 (95% CI, −3.3 to 1.8) in language and Δadj, −0.3 (95% CI, −3.2 to 2.6) in mathematics for children whose mothers filled only second-generation antipsychotic prescriptions. The most commonly prescribed antipsychotic monotherapies, including chlorprotixene, flupentixol, olanzapine, zuclopenthixol, quetiapine, perphenazine, and methotrimeprazine, did not appear to be associated with poorer school performance, although the CIs were wide (Table 3).

Table 3. Difference in Mean Test Scores Between Children Born to Mothers With and Without Antipsychotic Prescription Fill During Pregnancy According to the Classes of Antipsychotics.

| Antipsychotic prescription during pregnancy | Language tests | Mathematics tests | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of tests/children | Mean score (95% CI) | Basic adjusted, Δ (95% CI)a | Fully adjusted, Δ (95% CI)b | No. of tests/children | Mean score (95% CI) | Basic adjusted, Δ (95% CI)a | Fully adjusted, Δ (95% CI)b | |

| No antipsychotic prescription | 1 605 026/663 009 | 55.4 (55.4 to 55.5) | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 906 477/594 085 | 56.1 (56.1 to 56.2) | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] |

| First-generation antipsychotics only | 2271/965 | 50.3 (49.2 to 51.3) | −4.1 (−5.6 to −2.7) | 0.3 (−1.1 to 1.7) | 1280/862 | 48.1 (46.6 to 49.5) | −6.9 (−8.6 to −5.3) | 0.0 (−1.6 to 1.6) |

| Chlorprotixene only | 452/215 | 48.5 (46.3 to 50.8) | −6.4 (−9.6 to −3.2) | 1.1 (−2.1 to 4.3) | 265/187 | 45.5 (42.3 to 48.7) | −10.5 (−14.0 to −6.9) | 0.4 (−3.1 to 3.9) |

| Flupentixol only | 420/170 | 47.7 (45.5 to 49.9) | −7.3 (−10.4 to −4.1) | −2.5 (−5.4 to 0.4) | 232/155 | 46.8 (43.6 to 49.9) | −8.7 (−12.4 to −5.0) | −2.1 (−5.4 to 1.3) |

| Zuclopenthixol only | 371/150 | 50.4 (47.7 to 53.0) | −2.5 (– 6.3 to 1.3) | 0.5 (−2.9 to 4.0) | 213/140 | 48.5 (44.9 to 52.0) | −4.6 (−8.8 to −0.4) | 1.7 (−2.6 to 6.0) |

| Perphenazine only | 289/134 | 52.2 (49.2 to 55.2) | −1.6 (−5.8 to 2.7) | 1.9 (−2.0 to 5.8) | 170/116 | 48.9 (44.8 to 52.9) | −6.0 (−10.9 to −1.1) | 0.6 (−4.0 to 5.1) |

| Methotrimeprazine only | 281/121 | 51.6 (48.6 to 54.7) | −3.2 (−7.6 to 1.2) | 2.7 (−1.7 to 7.0) | 157/106 | 45.6 (41.5 to 49.8) | −10.1 (−14.6 to −5.5) | −2.2 (−6.6 to 2.1) |

| Second-generation antipsychotics only | 622/332 | 48.2 (46.3 to 50.1) | −5.6 (−8.1 to −3.0) | −0.8 (−3.3 to 1.8) | 357/260 | 47.4 (44.8 to 50.0) | −8.3 (−11.3 to −5.4) | −0.3 (−3.2 to 2.6) |

| Olanzapine only | 340/156 | 50.7 (48.1 to 53.3) | −1.9 (−5.5 to 1.7) | 1.7 (−2.0 to 5.3) | 199/133 | 50.0 (46.4 to 53.5) | −4.3 (−8.6 to 0.1) | 2.3 (−1.9 to 6.6) |

| Quetiapine only | 199/135 | 44.3 (41.0 to 47.7) | −10.1 (−14.1 to −6.1) | −2.5 (−6.4 to 1.5) | 114/95 | 44.6 (40.1 to 49.1) | −12.1 (−16.9 to −7.4) | −1.3 (−5.8 to 3.3) |

Abbreviation: Δ, the difference in mean test score.

Basic adjustment for sex, calendar year of birth, parental country of origin, and grade.

Additional adjustment for maternal age at delivery; primiparity; maternal smoking during pregnancy; maternal marital status; maternal highest completed education in year of delivery; maternal psychiatric diagnosis at delivery; maternal inpatient and outpatient psychiatric treatment from 1 year before pregnancy until delivery; maternal and paternal self-harm before delivery; maternal filling prescriptions for antiseizure medications, anxiolytics, lithium, and antidepressants during pregnancy; paternal psychiatric diagnosis at delivery; and paternal income in the year of delivery.

Additional Analyses

The results remained consistent when stratifying by birth year, parental country of origin, grade, maternal psychiatric diagnosis, or test year, though maternal antipsychotic prescription was associated with borderline better performance among children whose mothers had other mental illnesses, excluding psychotic disorders; mood disorders; and neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders (eFigures 3 and 4 in the Supplement). When dichotomized as binary outcomes, 31.0% of exposed children had language test scores in the below-average category, in contrast to 23.3% of unexposed children (adjusted odds ratio, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.87-1.08). For mathematics, the proportion of test scores in the below-average category was 34.5% among exposed children vs 23.6% among unexposed children (adjusted odds ratio; 0.96, 95% CI, 0.85-1.09).

Sensitivity Analyses

The potential influences of confounding by treatment indication and shared familial and genetic factors and antipsychotic exposure misclassification were addressed in sensitivity analyses (eTables 4-8 in the Supplement), summarized in Table 4. The analyses consistently confirmed that maternal antipsychotic prescriptions filled during pregnancy did not appear to be associated with poorer school performance. In the sibling analysis, the mean test score in language was 50.4 (95% CI, 47.1-53.7) for exposed siblings and 50.8 (95% CI, 47.5-54.0) for their unexposed siblings (Δadj, −2.2; 95% CI, −6.4 to 1.9). Similar findings were observed in mathematics: the mean test score was 50.7 (95% CI, 47.3-54.2) for the exposed siblings vs 51.5 (95% CI, 48.2-54.8) for their unexposed siblings (Δadj, −1.0; 95% CI, −5.2 to 3.3). Inverse probability weighting was performed to account for potential bias owing to nonparticipation in standardized tests,31 which yielded similar results to the primary analyses (Table 4; and eTable 9 in the Supplement). Furthermore, the association between antipsychotic exposure and offspring neurodevelopmental disorders was examined as a validity check. A similar association was observed between children with and without school tests, suggesting that the selection would not lead to bias (eTable 10 in the Supplement).

Table 4. Sensitivity Analyses Addressing Potential Systematic Errors in the Association Between Maternal Antipsychotic Prescription Filled During Pregnancy and Offspring School Performancea.

| Analyses | Approaches | Potential bias to be addressed | Language tests | Mathematics tests | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of children (exposed/unexposed) | No. of tests (exposed/unexposed) | Fully adjusted, Δ (95% CI)b | No. of children (exposed/unexposed) | No. of tests (exposed/unexposed) | Fully adjusted, Δ (95% CI)b | |||

| Comparison of children born to mothers who filled antipsychotic prescriptions before pregnancy | Negative control | Confounding by indication | 1433/2091 | 3178/4644 | 0.3 (−1.3 to 2.0) | 1237/1790 | 1804/2591 | −0.6 (−2.5 to 1.3) |

| Discordant sibling analysis in children with language and mathematics tests in grade 6 | Sibling control | Confounding by shared familial and genetic factors | 210/248 | 210/248 | −2.2 (−6.4 to 1.9)c | 210/248 | 210/248 | −1.0 (−5.2 to 3.3)c |

| Analysis of maternal filling an antipsychotic prescription and school performance using children with fathers with antipsychotic prescriptions filled during pregnancy as the comparison group | Negative control exposure | Confounding by shared familial factors | 1329/3190 | 2955/7217 | 1.9 (0.4 to 3.4) | 1147/2750 | 1679/4099 | 1.5 (−0.3 to 3.2) |

| Redefining antipsychotic exposure as filling 2 antipsychotic prescriptions | Improve the specificity of antipsychotic exposure definition | Exposure misclassification | 719/663 723 | 1611/1 606 593 | 0.7 (−1.1 to 2.5) | 633/594 689 | 932/907 349 | 1.6 (−0.4 to 3.7) |

| Probabilistic bias analysis | Reassign antipsychotic exposure status based on the sensitivity and specificity | Exposure misclassification | 1433/663 009 | 3178/1 605 026 | 0.1 (−1.4 to 1.6) | 1237/594 085 | 1804/906 477 | 0.1 (−2.3 to 2.2) |

| Analysis weighted for characteristics associated with nonparticipation in standardized tests | Inverse probability weightingd | Selection bias | 1433/663 009 | 3178/1 605 026 | 0.4 (−0.8 to 1.6) | 1237/594 085 | 1804/906 477 | 0.4 (−1.0 to 1.8) |

Abbreviations: Δ, difference in mean test score.

More details can be found in eTables 4-9 in the Supplement.

Fully adjusted for sex; calendar year of birth; parental country of origin; grade; maternal age at delivery; primiparity; maternal smoking during pregnancy; maternal marital status in the year of delivery; maternal highest completed education in the year of delivery; maternal psychiatric diagnosis at delivery; maternal inpatient and outpatient psychiatric treatment from 1 year before pregnancy until delivery; maternal and paternal self-harm before delivery; maternal prescriptions for antiseizure medications, anxiolytics, lithium, and antidepressants during pregnancy; paternal psychiatric diagnosis at delivery; and paternal income in the year of delivery.

Estimates from this analysis were adjusted for characteristics that could differ between siblings, including sex, year of birth, primiparity, and maternal filling prescriptions of antiseizure medications, anxiolytics, lithium, and antidepressants during pregnancy.

The weight was based on a logistic regression model of 786 747 children, including maternal antipsychotic prescription during pregnancy and all covariates listed in Table 1.

Discussion

In this large nationwide cohort of 667 517 children in Denmark, antipsychotic prescriptions filled during pregnancy did not appear to be associated with poorer standardized test performance in language or mathematics after adjustment for potential confounders. We also found no evidence of variation by the timing of prescriptions, classes of antipsychotics, sex, or school grade.

To our knowledge, no previous study has examined the associations between prenatal antipsychotic exposure and school performance in children. We found no signs of poorer standardized test performance after prenatal exposure to antipsychotics. These findings align with previous findings of no increased risk of diagnosed neurodevelopmental disorders, learning disability, or poorer intelligence quotients among children prenatally exposed to antipsychotics.11,12,13,14,15 However, some children with more severe neurodevelopmental disorders may attend special education schools and thus may not have participated in the test program. However, this selection was less likely to bias the present associations because there was no association between prenatal antipsychotic exposure and offspring’s overall neurodevelopmental disorders. Moreover, inverse probability weighting analysis to account for nonparticipation in standardized tests confirmed the findings from the primary analyses.

Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, 2 main indications for antipsychotic treatment, if untreated or undertreated, can have substantial implications for the well-being of both the mother and her child, and in rare but most tragic cases, result in suicide and infanticide.32 Thus, whether to continue antipsychotic treatment during pregnancy is a complex decision that should balance the health outcomes of both the mother and the child. The crude differences in test scores indicate that children born to mothers filling antipsychotic prescriptions are more likely to have lower test scores and thus may benefit from early support.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of this study was its large population. Information on antipsychotic prescriptions filled by pregnant individuals and school performance was collected independently, thus minimizing information bias. We used standardized school tests that do not require assessment from teachers or evaluators. Thus, the test results were unlikely to be affected by observer bias and were more likely to yield a reliable, objective measurement of school performance. Applying probabilistic bias analysis to quantitatively model the effect of antipsychotic exposure misclassification provided reassuring findings.

This study also had some limitations. First, not all children (85%) completed at least 1 language or mathematics test. Therefore, this study may have been subject to selection bias. However, the prevalence of maternal antipsychotic prescriptions filled during pregnancy and its association with offspring neurodevelopmental disorders were similar between those included in the study and those excluded. Moreover, analysis using inverse probability weighting to account for the differences in characteristics yielded similar results. Second, information on the severity of underlying disorders is unavailable in the registers. However, we attempted to minimize residual confounding by incorporating proxy variables such as previous self-harm history, psychiatric diagnosis, and hospital psychiatric treatment. Furthermore, we stratified the analyses by the previous diagnosis. The results remained robust in these sensitivity analyses. Third, patients with psychiatric disorders often have poor adherence to antipsychotic treatment or take antipsychotics intermittently as needed.30 Thus, individuals who redeemed antipsychotic prescriptions do not necessarily take them during pregnancy. On the other hand, some patients may receive antipsychotics only in the hospital and thus are not captured by the prescription register. Therefore, we may misclassify antipsychotic exposure status and thus bias the finding toward the null. However, the results were similar when we redefined antipsychotic exposure as redeeming 2 antipsychotic prescriptions during pregnancy. Moreover, probabilistic bias analysis to correct for antipsychotic exposure misclassification yielded similar findings. Fourth, residual confounding from unmeasured lifestyle factors, such as alcohol consumption, may occur. However, we adjusted for many other covariates, which may be associated with these lifestyle factors and control for some confounding. Lastly, although we had a large sample size, we did not have enough power to study some individual antipsychotic medications.

Conclusions

In this register-based cohort study, we found no difference in school performance in Danish children of mothers with antipsychotic prescriptions filled during pregnancy compared with children of mothers without. These findings provide further reassuring data on offspring neurodevelopmental outcomes for individuals who need to take antipsychotics during pregnancy.

eMethods

eFigure 1. Standardized test score distribution by test year

eFigure 2. The graphical depiction of the timeline for assessing exposure, outcomes, and confounders

eTable 1. The ICD-8 or ICD-10 codes for subgroup diagnosis of psychiatric comorbidities

eTable 2. Classes of antipsychotic prescription during pregnancy

eTable 3. Characteristics of children with and without a school test

eFigure 3. Adjusted mean test score difference between children with and without maternal filling an antipsychotic prescription during pregnancy by birth year, parental origin, test grade, sex, and maternal previous psychiatric diagnosis

eFigure 4. Adjusted mean test score difference between children with and without maternal filling an antipsychotic prescription during pregnancy by test year

eTable 4. Association between maternal prescription fill for antipsychotics in pregnancy and school performance in children, using children with mothers with prescription fill for antipsychotics before pregnancy as the comparator

eTable 5. Sibling analysis of maternal prescription fill for antipsychotics and school performance restricted to children with sixth-grade math and language tests

eTable 6. Association between maternal filling antipsychotic prescription in pregnancy and school performance in children, in comparison to children whose fathers filled antipsychotic prescriptions during pregnancy

eTable 7. Association between maternal filling an antipsychotic prescription in pregnancy and school performance in children, redefining antipsychotic exposure as 2 antipsychotic prescriptions

eTable 8. Association between maternal filling an antipsychotic prescription in pregnancy and school performance in children, applying probabilistic bias analysis

eTable 9. Association between maternal filling an antipsychotic prescription in pregnancy and school performance in children, weighted for characteristics associated with nonparticipation in standardized tests

eTable 10. Hospital contact for neurodevelopmental disorders among included and excluded children born to mothers with and without filling an antipsychotic prescription, n (%)

eReferences

References

- 1.Barbui C, Conti V, Purgato M, et al. Use of antipsychotic drugs and mood stabilizers in women of childbearing age with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: epidemiological survey. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2013;22(4):355-361. doi: 10.1017/S2045796013000012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marston L, Nazareth I, Petersen I, Walters K, Osborn DP. Prescribing of antipsychotics in UK primary care: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(12):e006135. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):168-176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toh S, Li Q, Cheetham TC, et al. Prevalence and trends in the use of antipsychotic medications during pregnancy in the US, 2001-2007: a population-based study of 585,615 deliveries. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16(2):149-157. doi: 10.1007/s00737-013-0330-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park Y, Huybrechts KF, Cohen JM, et al. Antipsychotic medication use among publicly insured pregnant women in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(11):1112-1119. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reutfors J, Cesta CE, Cohen JM, et al. Antipsychotic drug use in pregnancy: a multinational study from ten countries. Schizophr Res. 2020;220:106-115. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.03.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newport DJ, Calamaras MR, DeVane CL, et al. Atypical antipsychotic administration during late pregnancy: placental passage and obstetrical outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(8):1214-1220. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moody CA, Robinson SR, Spear LP, Smotherman WP. Fetal behavior and the dopamine system: activity effects of D1 and D2 receptor manipulations. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1993;44(4):843-850. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90015-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Popolo M, McCarthy DM, Bhide PG. Influence of dopamine on precursor cell proliferation and differentiation in the embryonic mouse telencephalon. Dev Neurosci. 2004;26(2-4):229-244. doi: 10.1159/000082140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poels EMP, Schrijver L, Kamperman AM, et al. Long-term neurodevelopmental consequences of intrauterine exposure to lithium and antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;27(9):1209-1230. doi: 10.1007/s00787-018-1177-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Z, Chan AYL, Coghill D, et al. Association between prenatal exposure to antipsychotics and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, preterm birth, and small for gestational age. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(10):1332-1340. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.4571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Momen NC, Robakis T, Liu X, Reichenberg A, Bergink V, Munk-Olsen T. In utero exposure to antipsychotic medication and psychiatric outcomes in the offspring. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47(3):759-766. doi: 10.1038/s41386-021-01223-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hálfdánarson Ó, Cohen JM, Karlstad Ø, et al. Antipsychotic use in pregnancy and risk of attention/deficit-hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder: a Nordic cohort study. Evid Based Ment Health. 2022;25(2):54-62. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2021-300311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Straub L, Hernández-Díaz S, Bateman BT, et al. Association of antipsychotic drug exposure in pregnancy with risk of neurodevelopmental disorders: a national birth cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(5):522-533. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.0375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slone D, Siskind V, Heinonen OP, Monson RR, Kaufman DW, Shapiro S. Antenatal exposure to the phenothiazines in relation to congenital malformations, perinatal mortality rate, birth weight, and intelligence quotient score. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1977;128(5):486-488. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(77)90029-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):22-25. doi: 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bliddal M, Broe A, Pottegård A, Olsen J, Langhoff-Roos J. The Danish Medical Birth Register. Eur J Epidemiol. 2018;33(1):27-36. doi: 10.1007/s10654-018-0356-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt M, Schmidt SA, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449-490. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beuchert L, Nandrup A. The Danish national tests at a glance. Nationalokon Tidsskr. 2018;1:1-37. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kildemoes HW, Sørensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):38-41. doi: 10.1177/1403494810394717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jørgensen FS. Epidemiological studies of obstetric ultrasound examinations in Denmark 1989-1990 versus 1994-1995. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78(4):305-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petersson F, Baadsgaard M, Thygesen LC. Danish registers on personal labour market affiliation. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):95-98. doi: 10.1177/1403494811408483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB. The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):54-57. doi: 10.1177/1403494810395825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gasse C, Danielsen AA, Pedersen MG, Pedersen CB, Mors O, Christensen J. Positive predictive value of a register-based algorithm using the Danish National Registries to identify suicidal events. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018;27(10):1131-1138. doi: 10.1002/pds.4433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meltzer HY, Matsubara S, Lee JC. The ratios of serotonin2 and dopamine2 affinities differentiate atypical and typical antipsychotic drugs. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1989;25(3):390-392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mauri MC, Paletta S, Maffini M, et al. Clinical pharmacology of atypical antipsychotics: an update. EXCLI J. 2014;13:1163-1191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res. 2007;16(3):219-242. doi: 10.1177/0962280206074463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith GD. Assessing intrauterine influences on offspring health outcomes: can epidemiological studies yield robust findings? Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;102(2):245-256. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00191.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fox MP, Lash TL, Greenland S. A method to automate probabilistic sensitivity analyses of misclassified binary variables. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(6):1370-1376. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valenstein M, Blow FC, Copeland LA, et al. Poor antipsychotic adherence among patients with schizophrenia: medication and patient factors. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(2):255-264. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seaman SR, White IR. Review of inverse probability weighting for dealing with missing data. Stat Methods Med Res. 2013;22(3):278-295. doi: 10.1177/0962280210395740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spinelli MG. Maternal infanticide associated with mental illness: prevention and the promise of saved lives. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(9):1548-1557. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.9.1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

eFigure 1. Standardized test score distribution by test year

eFigure 2. The graphical depiction of the timeline for assessing exposure, outcomes, and confounders

eTable 1. The ICD-8 or ICD-10 codes for subgroup diagnosis of psychiatric comorbidities

eTable 2. Classes of antipsychotic prescription during pregnancy

eTable 3. Characteristics of children with and without a school test

eFigure 3. Adjusted mean test score difference between children with and without maternal filling an antipsychotic prescription during pregnancy by birth year, parental origin, test grade, sex, and maternal previous psychiatric diagnosis

eFigure 4. Adjusted mean test score difference between children with and without maternal filling an antipsychotic prescription during pregnancy by test year

eTable 4. Association between maternal prescription fill for antipsychotics in pregnancy and school performance in children, using children with mothers with prescription fill for antipsychotics before pregnancy as the comparator

eTable 5. Sibling analysis of maternal prescription fill for antipsychotics and school performance restricted to children with sixth-grade math and language tests

eTable 6. Association between maternal filling antipsychotic prescription in pregnancy and school performance in children, in comparison to children whose fathers filled antipsychotic prescriptions during pregnancy

eTable 7. Association between maternal filling an antipsychotic prescription in pregnancy and school performance in children, redefining antipsychotic exposure as 2 antipsychotic prescriptions

eTable 8. Association between maternal filling an antipsychotic prescription in pregnancy and school performance in children, applying probabilistic bias analysis

eTable 9. Association between maternal filling an antipsychotic prescription in pregnancy and school performance in children, weighted for characteristics associated with nonparticipation in standardized tests

eTable 10. Hospital contact for neurodevelopmental disorders among included and excluded children born to mothers with and without filling an antipsychotic prescription, n (%)

eReferences