Abstract

Adolescents with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) face many challenges in the school setting. Researchers have identified school stressors as potential predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors for PNES. However, few researchers have explored the perspectives of adolescents with PNES regarding their experiences of attending school, where they spend much of their time. Therefore, this qualitative study employed content analysis to explore the experience of attending school as an adolescent with PNES. Ten adolescents (100% female, 80% White) were interviewed. With an overwhelming response of “It’s hard!” from respondents, five themes regarding the school experience emerged: stress, bullying, accusations of “faking” seizure events, feeling left out because of the condition, and school-management of PNES. Underlying these themes were expressions of the need for increased understanding from and collaboration among peers, as well as the need for increased understanding from families, healthcare providers, and school personnel including school nurses. Study findings should inform future adolescent PNES research, practice decisions made by healthcare providers in the health and education sectors, education of healthcare and school professionals, and policy development and implementation.

Keywords: Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, Adolescents, Qualitative, School

1. Introduction

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) constitute a life-altering condition involving seizure-like events in the absence of abnormal brainwave activity [1]. Also called functional or dissociative seizures, PNES is classified as a stress-induced functional neurological symptom disorder [1]. Of all age groups, the PNES prevalence rate is highest among adolescents at 59.5/100,000 [2]. Mounting evidence demonstrates that adolescents with PNES face challenges related to school relationships [3], attendance [4], functioning [5], and academic performance [6]. When considering the development of adolescents with PNES through the lens of Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Model, it is logical to explore the multi-level influence of interactions with school peers, personnel, and policies [7]. A few researchers have used qualitative methods to explore adolescent, caregiver, and healthcare provider experiences with PNES care [8–10]. However, to our knowledge, the experience of attending school with PNES has not been reported in literature.

Without an understanding of adolescents’ experiences in an environment where they spend much of their time, interventions that address concerns of most importance to adolescents cannot be designed. Interventions that fail to address adolescent-identified, school-related concerns could result in poorer mental health, academic, and quality-of-life outcomes that impact adolescents’ future health and success. Gaining insight into concepts and conceptual relationships relevant to adolescents with PNES is critical for future intervention development to improve outcomes. The purpose of this study was to build upon existing knowledge pertaining to experiences and challenges faced by adolescents with PNES, particularly exploring school-related experiences amenable to future intervention. Therefore, the research question for this study was: What is the experience of attending school as an adolescent with PNES?

2. Methods

2.1. Design

We conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews to explore the school experience of adolescents with PNES. The research protocol was approved by the Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis Institutional Review Board. The protocol included obtaining both parent/caregiver informed consent as well as child assent prior to participation.

2.2. Setting

The first author conducted interviews via Zoom to capture the school experiences of adolescents across the nation. Adolescents were able to participate in interviews from the privacy of their homes where confidentiality could be maintained while a caregiver was close by if a seizure event occurred during the interview. The option to conduct the interview at school using school equipment and internet access was provided in the event a participant lacked access to a device with internet access at home.

2.3. Sample

We used purposive sampling, particularly “expert sampling,” to identify adolescents with PNES who could provide a rich description of their experiences with PNES at school [11]. Purposive “maximum variation sampling” was directed toward achieving a sample with a broad range of both positive and negative school experiences [12]. An a priori sample size was not determined; instead, sampling and interviewing were continued until data saturation was reached, or repetition of themes or patterns [13] was identified in participants’ responses.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) a diagnosis of PNES verified by self-report of video-EEG (as verbalized by the adolescent), (2) current or recent in-person attendance at school with other students and school personnel, (3) age between 12 and 19 years, (4) ability to speak and understand English, and (5) ability to discuss the experience of attending school as a student with PNES, as reported by person providing consent. The only exclusion criterion was lack of adolescent assent to participate in the study.

2.4. Recruitment

Recruitment for this study involved distributing informational flyers that described the study to adolescents’ caregivers. Three gatekeeper groups were contacted regarding sharing the informational flyer with potential participants:

School nurses were contacted via the National Association of School Nurses state affiliate email lists.

Mental healthcare providers were contacted via contact information provided on a PNES referral site (https://nonepilepticseizures.com/epilepsy-psychogenic-NES-information-referral-sites.php).

Administrators of PNES information-sharing and support groups on Facebook were contacted via Facebook Messenger.

Recruitment occurred from September of 2019 through October of 2020. Most participants were recruited through the flyer shared via a post on PNES Facebook groups, which was accompanied by a brief video introduction by the first author. Adolescents or their caregivers expressed interest by contacting the first author via email, Facebook Messenger, or phone. Following this initial contact, caregivers of those less than 18 years old provided information to ensure inclusion criteria were met and provided consent. Assent was received at the onset of the adolescent Zoom interviews.

2.5. Data collection

A semi-structured interview (Appendix A) was used to gather demographic, school, and individual characteristic information in addition to adolescents’ experience attending school with PNES. All interviews began with the same data generating statement. Data obtained during the interviews were recorded and stored using a password protected computer and secure cloud storage service. Audio recordings of each interview, ranging from 35 to 70 min (except for one interview ending because the adolescent was too upset to continue after 2 min, but still included in analyses), were transcribed by a transcription service and saved as a Microsoft Word document with no personal identifying information. Each transcript included a study identification number and was proofread by the first author to ensure accuracy. Then, the words within the transcripts were broken down into phrases (meaning units) and entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for data analysis [14–16].

2.6. Data analysis

Content analysis was selected to achieve a greater understanding of the complexities of attending school with PNES. Content analysis can be used to explore “affective, cognitive, social” significance [4, p. 3] by focusing on concepts and semantic relationships. Inductive and deductive content analysis methods were used to answer the research question.

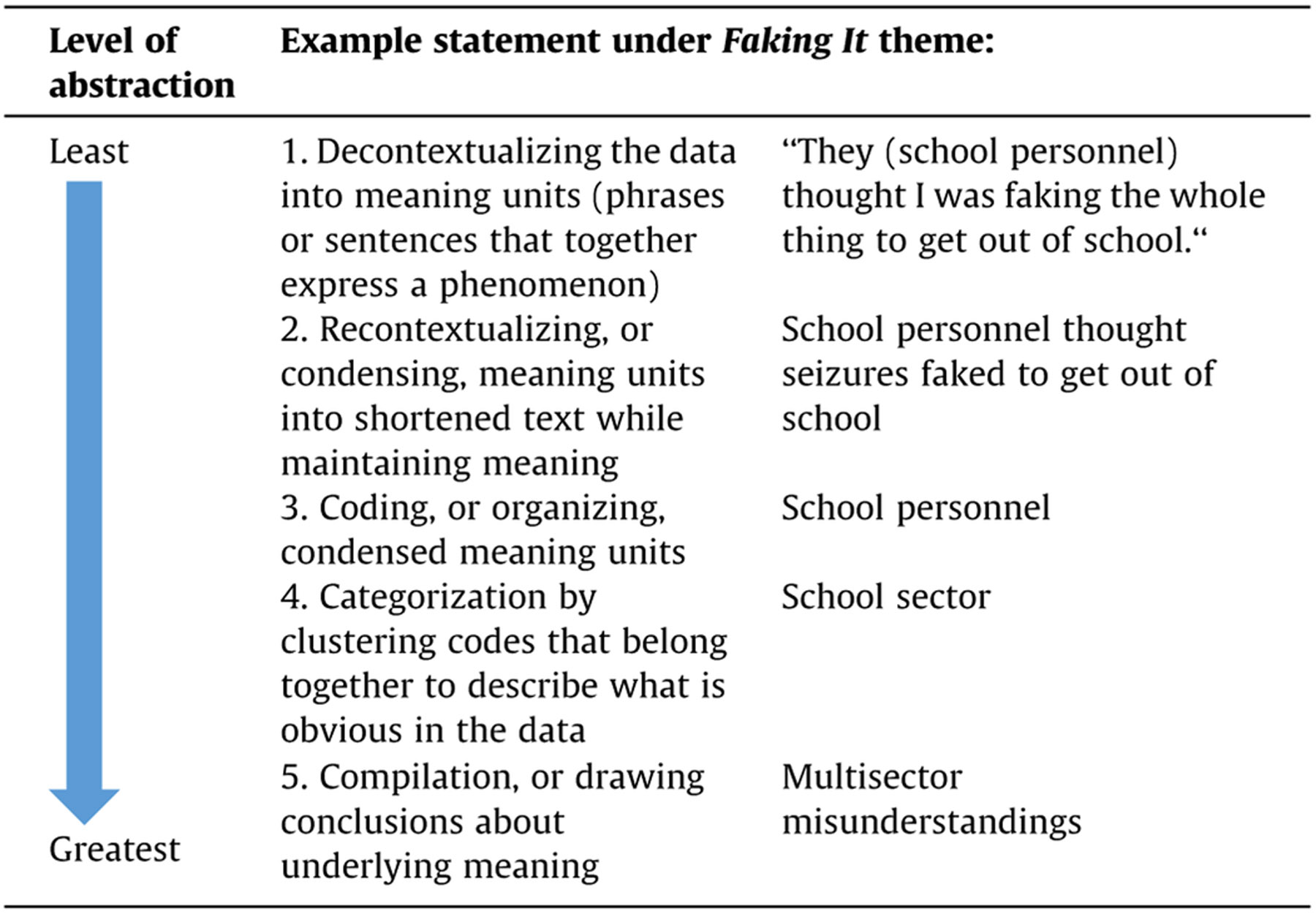

A step-by-step analysis plan was adapted from processes described by Erlingsson and Brysiewicz [15] and Bengtsson [14]. The analysis phase included a sequential process of content analysis. First, transcripts were reviewed three times by investigators to become immersed in the data while beginning to inductively open code (identify potential categories or themes that were not identified a priori) and ensure a priori themes (stressors and bullying) deductively derived from extant literature were appropriate “buckets” for initial organization of data [13]. Second, the data organization template was modified and used to organize participant responses to newly identified (inductive) and predetermined (deductive) overarching themes separated by columns. Lastly, thematically related meaning units from each column were reviewed, advanced through levels of abstraction (Table 1), and compiled into meaningful conclusions.

Table 1.

Advancement through Levels of Abstraction.

|

An audit trail was maintained during the data analysis phase to capture potential explanations, conclusions, inferences, and meanings. At the conclusion of the abstraction process, the compilations were combined to create a “larger meaning” of the data [11]. This larger meaning was evaluated through the lens of the research question and through the multi-level influences for adolescents with PNES, as understood through Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Model [7].

Rigor was insured by weekly debriefing with team members and bracketing preconceptions [17]. These practices limited the influence the first author’s previous experiences as a school nurse for adolescents with PNES had on the interviews and data analysis. Debriefing also included a review of data collection methods, coding process, and analysis techniques to ensure consistency. The validity, or trustworthiness, of the results of this study were substantiated through attention to credibility (truth of the findings through triangulating extant research and qualitative adolescent responses with varied school satisfaction), dependability and confirmability (consistency and repeatability of findings over time and contexts through audit trail), and transferability (ability to transfer findings to other contexts through a detailed analysis plan informed by theory) [18].

3. Results

3.1. Demographics, school, and individual characteristics

During the recruitment period, 21 participants or their families expressed interest in the study; however, seven did not complete the consent process and four were excluded (two for age beyond inclusion criteria, one for not attending school in the United States, and one for being home schooled since receiving diagnosis). Ten adolescents participated in the study. The first nine interviews occurred prior to COVID-19-related school closures in March 2020; one interview occurred two months after returning to inperson learning in October 2020. Adolescents ranged in age from 12 to 19 years (mean 15.8; SD 2.04). Eight adolescents self-reported as White (80%) and two self-reported as Black or African American (20%); all were female. Age at diagnosis ranged from 10 to 18 years, (mean 14.4; SD 2.06). Time since diagnoses ranged from less than 1 year to 4 years (mean 1.5, SD 1.06). Seven adolescents (70%) were from the Midwest, two (20%) were from the Northeast, and one (10%) was from the Southeast.

All students receiving mental health care also reported receiving school accommodations for PNES (80%), six via Section 504 plans and two via Individualized Education Plans (IEPs). One adolescent reported not receiving mental health nor documented school accommodations. Additionally, this student did not have access to a school nurse. Of the eight students with accommodations, five adolescents did not begin receiving school accommodations until after their PNES diagnosis, while three had comorbid diagnoses (ADHD, depression, and history of concussion) that qualified them for school accommodations. Additional details related to school and individual participant characteristics are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Individual and School Characteristics of the Sample.

| Variable | n = 10 | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Receiving mental health care | ||

| Yes | 8 | 80% |

| No | 1 | 10% |

| Unknown | 1 | 10% |

| School accommodations | ||

| Section 504 | 6 | 60% |

| IEP | 2 | 20% |

| None | 1 | 10% |

| Unknown | 1 | 10% |

| Initiation of accommodations | ||

| Before PNES diagnosis | 5 | 50% |

| After PNES diagnosis | 3 | 30% |

| School type | ||

| Public | 10 | 100% |

| Private | 0 | 0% |

| Charter | 0 | 0% |

| Program type | ||

| Homebound | 1 | 10% |

| Partial day | 4 | 40% |

| Full day | 5 | 50% |

| School 911 protocol | ||

| Did not call for every seizure | 5 | 50% |

| Did call for every seizure | 3 | 30% |

| Unknown | 2 | 20% |

| School nurse presence | ||

| None | 1 | 10% |

| Partial day/week | 4 | 40% |

| Full time | 4 | 40% |

| Unknown | 1 | 10% |

| Experienced bullying | ||

| Yes | 6 | 60% |

| No | 4 | 40% |

| Experience aura/seizure warning | ||

| Yes | 8 | 80% |

| No | 1 | 10% |

| Unknown | 1 | 10% |

| PNES event frequency | ||

| Daily | 3 | 30% |

| Weekly | 3 | 30% |

| Monthly | 2 | 20% |

| Bimonthly | 1 | 10% |

| Unknown | 1 | 10% |

| Missed school days | ||

| <25% of school days | 1 | 10% |

| 25–50% of school days | 3 | 30% |

| >50% of school days | 5 | 50% |

| Unknown | 1 | 10% |

| Perceived academic performance | ||

| Satisfactory | 8 | 80% |

| Unsatisfactory | 1 | 10% |

| Unknown | 1 | 10% |

Note. Unknown = missing data from interview that ended abruptly.

3.2. School experience themes

When asked about their experience attending school with PNES, most adolescents immediately responded with variations of, “It’s hard!” Two adolescents began by recounting their experience of having their first seizures at school while others shared the details of what made attending school with PNES so challenging. In the retelling of seizure experiences at school, themes of stressors, bullying, accusations of “faking it,” feeling left out, and school-management arose.

3.2.1. Stressors

Adolescents identified several internal and external stressors related to their school experience. Three adolescents distinguished internal stressors—comorbid mental health conditions including post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety—that influenced their school experience. Feelings of intense emotions, including anger, grief, and being overwhelmed were also identified as internal stressors.

All participants described external or school-related stressors that either originated from the school environment or impacted their school experience. Adolescents discussed the sense of feeling overwhelmed by school deadlines, being behind in the completion of schoolwork related to missing school, and academic struggles in one or more subject areas. Three adolescents experienced school struggles related to taking Advanced Placement or challenging courses. Adolescents also noted test anxiety as a school-related stressor. Two adolescents described experiencing school stress, but not having seizures in the most stressful classes. Rather, they experienced seizures in a particular class where they felt more safe or relaxed. Some students described general school environment concerns including others talking about their seizure activity inappropriately. One student attributed her seizures and school-related stress to racism expressed by fellow classmates. Another student described the school environment in terms of difficult interactions with a teacher. For adolescents transitioning to adulthood, one described stress related to balancing both school and work. While she experienced more seizures at school than at work, both were stressful environments that impacted her overall school experience. Another adolescent detailed the stress she experienced related to planning for college while having poor grades.

Not all stress disclosed by the adolescents were related to attending school. Adolescents mentioned stressors beyond the school environment that still impacted their school experience, including family interactions in which the student was providing for a parent’s needs. Another adolescent noted “money concerns” as a stressor that impacted her school experience. Two adolescents described the stress they perceived simply because of having seizures. For example, the stress of having seizures weighed heavily on one adolescent’s transition into adulthood as she declared, “I actually felt stressed by not being able to have a job and not being able to drive. I felt like I lost my sense of being an adult.”

3.2.2. Bullying

When asked directly about their experiences with bullying as a part of their school experience, a range of responses emerged. Four of the adolescents denied experiencing bullying initially. However, after each interview was completed, only one adolescent still maintained she did not experience bullying. All adolescents experiencing bullying only recalled bullying that occurred after having PNES, with no adolescents recalling bullying prior to having PNES. The adolescents listed several reasons others chose to bully them, forms in which bullying was delivered, and perpetrators of the bullying.

Adolescents revealed several reasons others bullied them, mostly related to their seizures. Adolescents described being bullied for “stupid things” and for “things I couldn’t help.” One student identified bullying that targeted her race rather than her seizures. However, all adolescents pinpointed seizure-related reasons for at least some of the bullying they endured. One adolescent recounted being bullied for the attention she received due to seizures and her frequent absences from school, including, “If you wanna leave school so badly, instead of having a seizure, why don’t you just drop out?” Derogatory comments from peers also pertained to perceptions of unfairness when the adolescent with PNES was allowed to attend a school trip despite poor attendance. Other instances of bullying involved peer comments such as, “You’re the seizure girl. You can’t do ‘this’ or ‘that’” and school personnel telling an adolescent with PNES that she was scaring other children.

Just as bullying occurred for many reasons, bullying also came in many forms from different people groups. The previously mentioned accounts of bullying were primarily verbal. However, one adolescent’s experience was a result of a digital social media post, which began with this event: “This kid has made a post about the whole seizure and how the school wasn’t treating me right and it ended all over Facebook. And then we had to deal with the legal troubles.” One adolescent explained her experience of bullying via written messages received on and in her locker while another described violent acts of bullying with rocks being thrown at her. As detailed in the previous accounts, peers at school were the primary offenders reported by eight different adolescents, but peers in an inpatient mental care facility also bullied adolescents with PNES. Finally, school personnel, responsible for identifying, reporting, and addressing bullying, were also identified as perpetrators in verbal bullying.

3.2.3. Accusations of “faking it”

One concept arose amidst adolescents’ discussions surrounding bullying and their school experience in general, the accusations of “faking it.” One participant pointed out the term “pseudoseizure,” formerly used for PNES, conjured the impression that the seizures are “not real.” Six of the ten adolescents interviewed described at least one person who had accused them of faking their seizures. While two adolescents specifically identified peers or friends as the accusers, the accusations were primarily cast by various members of both the healthcare sector and education sector.

Adolescents described several disconcerting interactions with healthcare personnel. One adolescent described doctors in the hospital conveying the accusation of faking seizures because they did not understand the condition. Another adolescent quoted her diagnosing physician, saying, “And then they did an EEG and that’s when they came up saying, it was PNES. She’s faking it. Send her home. There’s nothing we can do.” Participants also reported that hospital nurses and emergency medical personnel also made similar accusatory remarks.

Adolescents experienced similar responses from school personnel, including school nurses. One participant described overhearing a school nurse saying to other school personnel during a seizure, “She only does this in front of certain people.” Adolescents reported overhearing school personnel refer to their seizures as “attention episodes” acted out purposefully “to get out of school” and a principal reporting to his staff that “they’re faked for attention.” According to participants, classmates, even those thought to be friends, tended to follow the example set by their teachers and school leaders by echoing their remarks regarding faked seizures.

3.2.4. Left out

The negative thoughts and comments from school personnel, students, and healthcare providers created an environment where adolescents expressed feeling “left out”. Seven participants reported feelings of isolation or exclusion, with six stating their school environment was the cause of such feelings.

Adolescents with PNES attributed their feelings of school isolation and exclusion to five school-related factors. First, one adolescent described a lack of time to connect with others due to seizures, seizure-related absences, and resultant makeup work. Second, one adolescent described the experience of always having an adult escort decreasing the likelihood that she could interact with peers. Third, another adolescent described her school administrator’s decision to restrict her to a half-day schedule, which decreased the number of classes she had with peers as well as access to recreational opportunities. Fourth, five adolescents described being prohibited from attending school-related extracurricular events—a course after normal school hours, school spirit week, choir contest, field trip, football games, or homecoming—because of the chaos an untimely seizure might cause. Lastly, one adolescent explained that her school would not allow her to participate in physical education class with her peers because the gym was in a separate building from the main school building.

Peers in the school setting also contributed to feelings of exclusion. Adolescents expressed peers’ fear of seizures and avoidance of those different than themselves as reasons for feeling left out. One commented, “They [peers] treat us like we’re out-casters in a way.” One adolescent used a social media poll to gain understanding of how others viewed her, resulting in 48 responding they viewed her differently because of her condition and eight responding their view of her was unchanged.

Beyond feeling excluded by peers, multiple adolescents experienced exclusion or isolation from interactions with healthcare providers. One adolescent described her inability to try out for cheerleading because the urgent care center where she attempted to obtain a school physical would not examine her due to her having “unexplained seizures.” She later learned that other healthcare providers might have performed a physical, but that information was received too late for her to try out for cheerleading. The healthcare system was also a source of isolation for an adolescent when a neurologist provided the diagnosis of PNES without any subsequent transition follow-up care or school guidance. She said, “I…felt like I was just pushed out to sea and left to build a raft on my own.”

Adolescents voiced that they were the source of some of their feelings of exclusion or isolation. They expressed feeling the need to orchestrate life around PNES because of the fear of impending seizures happening at school and to avoid seizure triggers. One adolescent described being involved in the decision with school leaders to isolate in the health office rather than attend school spirit week events. Another adolescent expressed a desire to separate herself from others who do not have PNES, stating, “I just wanna go to a school where everyone has the same disorders as me, so they could treat me the same.”

3.2.5. School-management

When adolescents with PNES were asked to speak about their school experience, a final prominent theme that emerged was school-management. Out of 64 meaning units, 38 were negative attributes of school-management offered by 9 adolescents and 26 were positive attributes contributed by 8 adolescents, with 7 adolescents experiencing both positive and negative school-management of PNES. Two adolescents had only negative school-management experiences to share while one had only positive experiences to share. Various school accommodations and responses shaped adolescents’ perceptions of their school experiences, both positive and negative.

When describing negative school-management of PNES, adolescents identified school-management as liability-driven, seizure-defined, schoolwork-distracting, ever-changing, increasingly restrictive, others-centered, teacher-led, pain-inducing, and fear-driven. Adolescents listed numerous school-management activities that shaded their school experience, including being placed with a one-on-one instructional assistant, being placed in homebound instruction when unable to physically get out of bed to participate in the instruction, being excluded from classes because of seizures, and being required to participate in emotion check-ins with a counselor so the school could gauge the likelihood of a seizure each day. School personnel contributed to inappropriate school-management when they: (1) guessed how to respond to adolescents’ needs rather than following an action plan; (2) immediately called parents to pick up adolescents after each seizure; (3) “paraded” adolescents via wheelchair throughout the school; (4) attempted to calm adolescents when they were not feeling the need for calming; and (5) mishandled seizures through such actions as “put[ting] a pencil in my mouth at one point to keep it open and apart.” Adolescents were negatively affected by responses from school personnel, as one explained, “I fell and hit my head, and had a seizure. And they didn’t really do anything, they just said, ‘Oh, okay, go back to class.’” Another student shared, “Nobody cared that I was seizing until I started bleeding.” Having even just one teacher who responded negatively to their condition made adolescents’ view their school experience as negative.

School-management adolescents considered beneficial was categorized as student-centered and safety-centered. Positive, or supportive school-management included the following accommodations: (1) notifying adolescents in advance of seizure triggers such as fire alarms; (2) allowing elevator use and early dismissal from class to avoid crowds; (3) extending time to complete homework or tests to decrease stress; (4) permitting tests to be taken at home when seizures prevented attendance; (5) adhering to a student-informed Section 504 plan with seizure response action steps; (6) making improvements to seizure response processes based on learning from previous seizures; (7) utilizing a small team approach for responding to seizures; and (8) employing effective teacher–student communication. Supportive school-management also involved having a space for adolescents with PNES to calm when experiencing heightened stress levels and transitioning adolescents to homebound instruction when seizure frequency made school attendance too difficult. Adolescents described the importance of knowing there was at least one person at school who expressed interest in understanding PNES and could be trusted.

To better understand adolescents’ expectations for positive school-management, the researcher asked each adolescent to envision an ideal school experience. One adolescent remarked, “I would just be able to go and do stuff without having to perfectly orchestrate it.” Two adolescents wished they could experience life without being accused of faking their seizures and one hoped for a life free of fearing seizures. Specific to school, adolescents hoped to be able to remain in class despite seizures while the teacher continued to teach class. One desired having just one friend assist her during seizures rather than a team of school personnel bringing attention to the seizures. Another expressed a desire for “perfect attendance” and “perfect grades.” The ideal bystander response included responding in confidence rather than fear; with knowledge, reassurance, and a motherly instinct; and without assumptions of the seizures being faked. Table 3 provides a summary of themes and categories with exemplar quotes from adolescents.

Table 3.

School Experience Themes, Categories, and Exemplar Statements.

| Theme | Category | Exemplar Statement |

|---|---|---|

| Stressors | Internal | “Sometimes getting bad memories, sometimes thinking too much of the past, and sometimes that just affects me emotionally.” |

| External | “Attendance and make-up work has been the biggest thing.” | |

| “I’m stressed ‘cause I’m like, ‘Well, what about my future? I’ll never get into a college with these kind of grades.’” | ||

| “Seizures themselves are stressful.” | ||

| “It stressed me out to feel like I couldn’t go anywhere or do anything.” | ||

| Bullying | Reasons | “And it was mainly kids felt that it was unfair that I still got to go on a senior trip, I got to do this, I got to do that, when these things were attendance based. Well, these were things I couldn’t help.” |

| “They called me attention-whore and things like that.” | ||

| Forms | “I had stuff thrown at me, things like that. I had one kid throw probably the biggest rock I had ever seen at me one day when I was getting in my sister-in-law’s car and yelled at me that if a brain injury started all of this, maybe another one could cure it.” | |

| “I would get letters put on my locker or in my locker.” | ||

| Perpetrators | “When the school had called and told me that I was scaring the other children, I definitely felt a sense of… I felt attacked in a sort of that way.” | |

| Accusations of “faking it” | Health care | “EMS said, ‘Sign these papers quickly because we have somebody with real chest pain to go get to.’” |

| School | “They (school personnel) thought I was faking the whole thing to get out of school.” | |

| “The principal decided to agree with everything he read online that they’re faked for attention and stuff like that.” | ||

| “My school nurse thinks that I fake it and she just thinks I fake all of it.” | ||

| “Yeah, everyone thinks it’s just for attention, but I don’t know why I’d put myself through having a seizure and hitting my head and having a bump on my head just for attention. That’s not the way to get attention.” | ||

| Left out | School-inflicted | “I can’t go to extracurricular activities like ball games. Veteran’s day was yesterday, they had a whole assembly and stuff. I cannot go to stuff like that…They’re afraid that I’m going to fall out and have a seizure, and then it would be a mess.” |

| “Every second that I had that I wasn’t insanely stressed or worried about having a seizure or actually having a seizure was spent frantically trying to catch up on the work. I was either having seizures, or I was catching up as much as possible, and I was always behind. So yeah, I didn’t really have any time to talk to people in the hallways or anything.” | ||

| Peer-inflicted | “They had just kicked me out of everything. They would talk to me; they would call me crazy.” | |

| Health care-inflicted | “Last year I was going to try out for cheerleading for the fall season, and I was denied a physical at [an urgent care clinic], because they said no one would give me a physical with unexplained seizures.” | |

| Self-inflicted | “During school spirit week we would all gather into the gym, and I would always sit out during those moments.” | |

| School-management | Negative | “The school administration was awful. I remember when I went over my limit for seizures, they roll out new plans.” |

| “After new superintendent and lawyer got involved, they wouldn’t get blamed, they have to call 911 first to make sure I’m okay, and then call my grandma.” | ||

| “They didn’t know what to do with me, so they just told me to walk around. So, I was walking by lockers, there’s this hall, where you just can walk by yourself. And I fell and hit my head and had a seizure. And they didn’t really do anything, they just said, ‘Oh, okay, go back to class.’” | ||

| “If they (principal’s assistant and counseling assistant) were called, I all but started crying because they would put all of their weight on me… They would move me to one side, and then put all of their weight to try and constrict the movement. And this hurt more than anything.” | ||

| “I’ve had teachers say that they didn’t want me as a student ‘cause they just… It’s a lot of extra stuff they have to deal with, and it’s a distraction for the class, stuff like that.” | ||

| Positive | “The teachers, generally, were pretty nice. They’re very accommodating.” | |

| “They have an elevator ‘cause I can’t go up the stairs, ‘cause they’re afraid I’m gonna fall down the stairs. I get to go up the elevator every day. That’s extremely helpful.” | ||

| “Well, they’re also extremely interested with my condition. They’ve signed so many release forms and talked with my doctors, and my psychiatrists, and tons of hospitals that have treated me with my condition.” | ||

| “In school we’ve all come up with a plan. One person has to go get the teacher, one helps me out and stuff like that.” | ||

| Ideal | “I feel like just as it’s scary for me, of course, it’s also scary for them. I feel like if people recognize the fear in both accounts, it would help a lot of situations that I had to go through.” | |

| “I would want them to respond kind of not in fear but in confidence of knowing what they could do, kinda like the basic necessity. Make sure their airway is opened, protect their head, make sure they’re not restraining them.” |

4. Discussion

Adolescents provided poignant glimpses into their experiences attending school with PNES. Riddled with stressors, bullying (considered disability harassment by the Office for Civil Rights [19]), accusations of faking seizure events, and stigma-infused exclusion from school events, adolescents formed a narrative of their school-management experiences. Based upon their varied responses, PNES school-management is not one-size-fits-all. For instance, some adolescents felt oppressed by having a one-on-one aide during the school day or homebound instruction while others appreciated such services. While school-management strategies were met with mixed adolescent approval, both school personnel and healthcare providers contributed to misunderstandings regarding PNES diagnosis legitimacy and adolescents’ inability to control seizure events. Both sectors were reported to accuse adolescents of faking seizure events; however, both sectors could collaborate to improve multi-sector understanding and develop PNES action plans for more supportive school-management. Because of the perplexing mind–body connection of PNES, health and education leaders must address both the physical safety and mental health support necessary to effectively manage PNES outside of the healthcare system, namely in the education setting.

4.1. Comparison with existing adolescent PNES studies

To our knowledge, researchers have not explored adolescents’ school experiences with PNES from the adolescents’ perspective. Our findings are consistent with those of other studies that have examined aspects of school experiences. A systematic review of patient and caregiver perspectives of pediatric PNES revealed recurring themes of the need to legitimatize PNES, feel understood, and manage social and academic stressors [15]. A qualitative study of pediatric and parent experiences with PNES established several themes consistent with our findings as well, including perceptions of missing out, feeling misunderstood, and PNES as “less than” epilepsy [10]. An antidote to such negativity identified by participants in this study was knowing at least one person understood them and cared about them, similar to findings among adolescent students with emotional behavioral disabilities [20]. Studies on healthcare providers’ perspectives further support our findings, including school nurses’ experiences of other school personnel believing seizure events to be fabricated and healthcare providers providing insufficient guidance for school-management [21].

Healthcare providers have identified a gap in services for pediatric PNES and recommend improving collaboration between pediatricians and school liaisons to improve pediatric PNES outcomes [9]. Unfortunately, such collaboration has been stymied by ethical dilemmas surrounding school policies and procedures. For instance, some healthcare providers have expressed concern that school personnel will inappropriately respond to adolescents with epileptic seizures after learning how to respond to nonepileptic seizures [8]. School leaders have shared concern regarding school liability for not summoning emergency care for events that resemble prolonged epileptic seizures [8]. The impact of ethical dilemmas and lack of consistent collaboration between health and school teams is evident in the experiences of adolescents interviewed in our study.

4.2. Limitations

Several limitations exist within this study. First, participants who responded to our flyers may have expressed stronger (particularly negative) views compared to the general population, and so our results may be subject to selection bias. However, attempts were made to ensure opposing views were discovered in the content analysis before concluding that saturation had been reached [13].

Second, this study lacked diversity in participant gender, race, and school type. Only female adolescents participated. Although more females than males are diagnosed with PNES [22,23], the findings would be more representative if male perspectives were included. Many studies of adolescents with PNES did not report race of participants [24–29] although Sawchuk and colleagues found in their study 79% of adolescents with PNES were White [30], similar to our study. Future research should include perspectives of non-White adolescents with PNES. The study findings also may be more generalizable if it included participants from private or charter schools rather than only public schools. However, a benefit to only interviewing adolescents in public schools is that legal expectations for disability-related accommodations were consistent for all participants.

Finally, the most successful recruitment method used in this study was accessing participants or their guardians through PNES support groups on Facebook. Because eight of ten adolescents were recruited on an online platform, it is likely that adolescents without internet access or family use of social media were excluded from this study. It is unknown what differences, including social determinants of health, may exist between adolescents with and without internet or social media access. Such differences may have impacted school experiences. Future studies should collect data to examine the influence of family income, school free/reduced lunch rates, and school urbanicity. Finally, recruiting via Facebook support groups may have increased the likelihood of including adolescents who have heightened concerns or greater advocacy tendencies. Adolescents with caregivers who seek support groups may have different school experiences than those who do not.

4.3. Future implications for PNES care

Findings from this qualitative content analysis inform future research and practice implications. As little is known about adolescents’ school experience with and school-management of PNES, further research is needed to understand school-management of PNES from other perspectives, including school-based nurses, administrators, mental healthcare providers, and other healthcare providers. Prior to developing interventions to improve adolescents’ school experience, it is also important to gain additional school-management perspectives, test potential conceptual relationships, and validate outcome measures with a more representative sample of adolescents. To translate current and future research into practice, researchers and healthcare providers should collaborate with school nurses and other school team members. A collaborative effort among neurologists, neuropsychiatrists, and mental healthcare providers is needed to provide appropriate guidance for adolescents, families, and school personnel. This guidance should include how to reactively respond to PNES events and proactively develop action plans.

PNES research and practice must inform the education of healthcare providers and education personnel as well as policy. Unfortunately, both healthcare providers and education personnel contributed to adolescents’ many instances of harassment and being accused of faking their seizures. There is a critical need for PNES experts to educate healthcare providers and education personnel (such as school nurses, teachers, administrators, and counselors) regarding the legitimacy of this condition and adolescents’ inability to control PNES events. Misunderstandings regarding PNES led to adolescents’ negative experiences including violations of their educational right to a Free Appropriate Public Education [19]. Healthcare providers who care for adolescents with PNES are well positioned to advocate for students to ensure their schools equitably address PNES care needs and do not exclude students from learning and school-sponsored activities because of their condition. Both healthcare providers and education personnel should advance their education legal literacy and support adolescents through guiding development of such legally binding documents as IEPs or Section 504 Plans.

5. Conclusion

Adolescents with PNES report onerous experiences while attending school. They endure school and condition related stressors, bullying from peers and harassment from school personnel, accusations of fabricating seizures, and feelings of being left out from peer and school activities. School-management decisions made by school and healthcare personnel can impact adolescents’ perceptions of the school experience. Information gleaned from this qualitative study will inform future research, practice, education, and policy efforts aimed toward improved mental health, academic, and quality-of-life outcomes for adolescents with PNES.

Funding

This work was supported by Indiana University School of Nursing at Indianapolis, through their T32 postdoctoral fellowship titled “Advanced Training in Self-Management Interventions for Serious Chronic Conditions” [National Institute of Nursing Research grant number T32 NR018407] and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Future of Nursing Scholars fellowship.

Appendix A

Semi-structured interview script

Tell me about what it is like to come to school as a student with PNES. Describe any experiences that seem important, as well as your thoughts and feelings. Continue to describe your experiences until you feel you have fully described what it is like to be a student at school with PNES.

Possible follow-up questions:

Who has been a part of your PNES at school?

When did episodes occur? Not occur?

Where did episodes occur? Not occur?

How does your experience in school compare to other students who do not have PNES?

What is most helpful to you at school as a student with PNES?

What is most harmful at school for you as student with PNES?

What do you do to help you manage your PNES?

What has or could the school nurse do to help you manage your PNES?

Demographic, School, and Individual characteristics questions:

How old are you right now?

How old were you when you were diagnosed with PNES?

How were you diagnosed? Was a video-EEG done?

What gender are you?

Are you under care of mental healthcare professional right now? Have you ever been?

Are you under the care of a seizure specialist right now? Have you ever been?

Are you still experiencing PNES spells? Time since last one? How often (times per day, week, month)?

Do you experience any aura/warning/clue that you might have a seizure? Type? How do you respond when you have an aura?

Have you experienced bullying? At school or outside of school? Before or after dx?

What things in your life cause you to feel more stress than usual?

How are you doing in school? How are your grades? Have you ever changed schools?

How is your school attendance? How many days of school have you missed this school year?

Do you have an IEP? 504 plan? Was the plan first developed before or after PNES diagnosis?

In what region of the US do you live?

Type of school setting? Public, private, charter, online, homeschool?

Type of program? Full day, partial day?

School nurse present? All day, partial day every day, some days, never?

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].American Epilepsy Society. Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. n.d.

- [2].Villagrán A, Eldøen G, Duncan R, Aaberg KM, Hofoss D, Lossius MI. Incidence and prevalence of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures in a Norwegian county: a 10-year population-based study. Epilepsia 2021;62:1528–35. 10.1111/epi.16949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Alhafez L, Masri A. School bullying: An increasingly recognized etiology for psychogenic non-epileptic seizures: report of two cases. Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med 2019;6:5–7. 10.1016/j.ijpam.2019.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Plioplys S, Doss J, Siddarth P, Bursch B, Falcone T, Forgey M, et al. A multisite controlled study of risk factors in pediatric psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia 2014;55:1739–47. 10.1111/epi.12773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Akdemir D, Uzun Ö, Pehlivantürk Özsungur B, Topçu M, Özsungur BP, Topçu M. Health-related quality of life in adolescents with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav 2013;29:516–20. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Doss J, Caplan R, Siddarth P, Bursch B, Falcone T, Forgey M, et al. Risk factors for learning problems in youth with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav 2017;70:135–9. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The Bioecological model of human development. Handbook of child psychology, Hoboken, NJ: International Universities Press.; 2006, p. 793–828. 10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cole CM, Falcone T, Caplan R, Timmons-Mitchell J, Jares K, Ford PJ. Ethical dilemmas in pediatric and adolescent psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav 2014;37:145–50. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].McWilliams A, Reilly C, Heyman I. Non-epileptic seizures in children: views and approaches at a UK child and adolescent psychiatry conference. Seizure 2017;53:23–5. 10.1016/j.seizure.2017.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].McWilliams A, Reilly C, McFarlane FA, Booker E, Heyman I. Nonepileptic seizures in the pediatric population: a qualitative study of patient and family experiences. Epilepsy Behav 2016;59:128–36. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Etikan I, Musa SA, Alkassim RS. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am J Theor Appl Statis 2016;5:1–4. 10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Marshall C, Rossman GB. Designing qualitative research. 6th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bengtsson M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open 2016;2:8–14. 10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Erlingsson C, Brysiewicz P. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. Afr J Emerg Med 2017;7:93–9. 10.1016/j.afjem.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today 2004;24:105–12. 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tufford L, Newman P. Bracketing in qualitative research. Qualitative Social Work 2012;11:80–96. 10.1177/1473325010368316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lincoln YS, Guba EG, Pilotta JJ. Naturalistic inquiry. Int J Intercultural Relations 1985;9:438–9. [Google Scholar]

- [19].United States Department of Education. Prohibited Disability Harassment. 2000.

- [20].Whitlow D, Cooper R, Couvillon M. Voices from those not heard: A case study on the inclusion experience of adolescent girls with emotional-behavioral disabilities. Children Schools 2019;41:45–54. 10.1093/cs/cdy027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Terry D, Trott K. A qualitative analysis of school nurses’ experience caring for students with psychogenic nonepileptic events. J School Nurs 2019:1–8. 10.1177%2F1059840519889395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Asadi-Pooya AA, Sperling MR. Epidemiology of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav 2015;46:60–5. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Say GN, Taşdemir HA, Ince H. Semiological and psychiatric characteristics of children with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: gender-related differences.Seizure 2015;31:144–8. 10.1016/j.seizure.2015.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yadav A, Agarwal R, Park J. Outcome of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) in children: a 2-year follow-up study. Epilepsy Behav 2015;53:168–73. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kim SH, Kim H, Lim BC, Chae J-H, Kim KJ, Hwang YS, et al. Paroxysmal nonepileptic events in pediatric patients confirmed by long-term video-EEG monitoring — Single tertiary center review of 143 patients. Epilepsy Behav 2012;24:336–40. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Park EG, Lee J, Lee BL, Lee M, Lee J. Paroxysmal nonepileptic events in pediatric patients. Epilepsy Behav 2015;48:83–7. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cornaggia CM, di Rosa G, Polita M, Magaudda A, Perin C, Beghi M. Conversation analysis in the differentiation of psychogenic nonepileptic and epileptic seizures in pediatric and adolescent settings. Epilepsy Behav 2016;62:231–8. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Papagno C, Montali L, Turner K, Frigerio A, Sirtori M, Zambrelli E, et al. Differentiating PNES from epileptic seizures using conversational analysis. Epilepsy Behav 2017;76:46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Asadi-Pooya AA, Myers L, Valente K, Sawchuk T, Restrepo AD, Homayoun M, et al. Pediatric-onset psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a retrospective international multicenter study. Seizure 2019;71:56–9. 10.1016/j.seizure.2019.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sawchuk T, Buchhalter J, Senft B. Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures in children—Prospective validation of a clinical care pathway & risk factors for treatment outcome. Epilepsy Behav 2020;105:. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.106971106971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]