Abstract

Background:

The management of achalasia has improved due to diagnostic and therapeutic innovations. However, variability in care delivery remains and no established measures defining quality of care for this population exist. We aimed to use formal methodology to establish quality indicators for achalasia patients.

Methods:

Quality indicator concepts were identified from the literature, consensus guidelines and clinical experts. Using RAND/University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Appropriateness Method, experts in achalasia independently ranked proposed concepts in a two-round modified Delphi process based on 1) importance, 2) scientific acceptability, 3) usability, and 4) feasibility. Highly valid measures required strict agreement (≧ 80% of panelists) in the range of 7–9 for across all four categories.

Key Results:

There were 17 experts who rated 26 proposed quality indicator topics. In round one, 2 (8%) quality measures were rated valid. In round two, 19 measures were modified based on panel suggestions, and experts rated 10 (53%) of these measures as valid, resulting in a total of 12 quality indicators. Two measures pertained to patient education and five to diagnosis, including discussing treatment options with risk and benefits and using the most recent version of the Chicago Classification to define achalasia phenotypes, respectively. Other indicators pertained to treatment options, such as the use of botulinum toxin for those not considered surgical candidates and management of reflux following achalasia treatment.

Conclusions & Inferences:

Using a robust methodology, achalasia quality indicators were identified, which can form the basis for establishing quality gaps and generating fully specified quality measures.

Keywords: achalasia, clinical practice, esophageal dysphagia, esophageal motility, quality indicators

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Achalasia is a rare disease, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 100,0001 and characterized by incomplete lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and disordered esophageal motility. There is evidence that the incidence is increasing,1–3 which may be related to improved detection.4 Overall, clinical care of achalasia has improved during the last decade with advances in diagnostic technology including the introduction of esophageal high-resolution manometry (HRM) and use of the endoscopic functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP). Furthermore, management techniques continue to advance with sub-type specific treatment options now including per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) in addition to pneumatic dilation and Heller myotomy with partial fundoplication.5 Society guidelines have likewise responded to these advancements in technology and therapeutic techniques.6–9

Nonetheless, there are differences in the performance and interpretation of motility testing10 as well as the management of achalasia patients. Even as current guidelines outline best clinical practice recommendations, there are no existing metrics on which clinicians can report or track their outcomes. While variation is expected due in part to institutional expertise and availability of ancillary diagnostic testing and treatment modalities, the potential exists for achalasia patients to receive inconsistent care across settings.6–9

As a result, and because of the increasing evidence base for tailored therapy leading to optimal outcomes, establishing metrics for achalasia is important. Generating a quality measure, including those on which clinicians can report as part of a systematic quality program such as the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), relies on an extensive process of specification, testing, and formal programmatic submission.11 These measures are necessarily different, though frequently are derived from, guideline recommendations12; they may be outcomes-based and impart greater significance than guideline statements, particularly as they require strong recommendations with high levels of evidence.13 Quality indicators, though also ways to track health care performance and outcomes, are separate constructs.14 While they also proscribe a defined clinical circumstance15 in which care is appropriate or indicated and are related to the structure, process, or outcomes of that care, they should be considered an initial step in this process to identify critical concepts worthy of measure development and a means by which quality gaps can be recognized. Therefore, we aimed to identify quality indicators for adult patients with achalasia being managed by gastroenterologists using established formal methodology relying on the existing evidence base of literature and guidelines as well as expert opinion.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

To develop achalasia-specific quality indicators, we applied the RAND/University of California, Los Angeles Appropriate Methodology (RAM) through a modified two-round Delphi technique among invited academic gastroenterologists. This study was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board (IRB).

2.1 |. Expert panel recruitment

The professional panel of esophageal experts were recruited by direct email invitations from the primary investigators (AK, PK, FO, DL). To ensure generalizability of the proposed quality indicators, the panel members were recruited among those with English language proficiency and, if international, academic health systems comparable to the United States. Invited expert participants were recruited based on a national and/or international reputation in the clinical expertise for managing achalasia, publications and academic record within esophageal diseases. A total of 22 gastroenterologists were contacted. If experts accepted the invitation, they were immediately enrolled into round one.

2.2 |. Compilation of Potential Quality Indicators

Potential achalasia quality indicators were identified by the primary investigators through an extensive literature review and assessment of guidelines endorsed by professional societies (ie, American College of Gastroenterology, American Gastroenterology Association, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus). The literature review included a detailed assessment of scientific papers including large randomized controlled trials, cohort studies and systematic reviews. Candidate indicators encompassed initial diagnosis, management (surgical and non-surgical), and follow up. Purposefully the authors composed initial indicators to contain both specific and general statements, with the final results dependent on expert voting and suggested modifications.

2.3 |. Analyzing Measures for Validity

Analysis of the measures was performed using the scoring definitions applied in standard quality indicator development. Validity was determined based on median rankings and the dispersion of rankings. We applied a 9-point Likert scale in which a score of 1= “definitely not valid”, 5= “uncertain”, and 9= “definitely valid.” Agreement for the panel was defined by 80% or more panelists’ rankings falling in the same three-point range (ie, 1–3, 4–6, or 7–9), where agreement was noted for the ranking of 7–9, as applied in prior quality indicator developments. 16 Each proposed indicator was separately ranked based on importance, scientific acceptability, usability and feasibility.17 If one or more of the rankings in one category were not in a similar three-point range among the others, this was considered indicative of disagreement for the proposed indicator. A measure was considered valid if there was a strict agreement within all four categories in the ranking range of 7–9.

2.4 |. Round 1: Initial ranking of Achalasia quality indicators

We used a well-described formal methodology to develop valid, physician-led, quality indicators for patients with achalasia.18 This method applied a two-round modified RAND/UCLA Delphi process organized by the primary investigators and who were not voting members of the panel. In round one, members of the professional expert panel received an invitation with specific instructions for ranking by an electronic mail. Ranking was hosted by Qualtrics (Provo, Utah, USA). Experts were provided instructions and definitions on each category (importance, scientific acceptability, usability and feasibility) to ensure each rater was interpreting terms similarly. We requested the panelists to independently rank each proposed indicator on personal judgment and scientific knowledge.

Panelists ranked each indicator separately on importance, scientific acceptability, usability and feasibility applying the 9-point Likert scale. Following round one ranking, panelists were provided an opportunity to suggest modifications to the proposed indicator to improve potential validity, and responses were de-identified. Summary statistics were calculated for each proposed quality measure assessing for level of agreement. Agreement among the members was defined by >=80% rankings falling in the three-point range of 7–9.19

Participants could access the survey ranking on their personal electronic device (ie, cell phone, tablet or computer), as well as complete the survey on multiple sittings without having to restart the ranking. This survey allowed for no response if the participant did not feel it was appropriate. Panelists were asked to complete the rankings within two weeks. The primary investigators monitored responses and sent reminder emails to panelists one week prior to the ranking submission deadline.

2.5 |. Round 2: Adapting indicators meeting disagreement and re-ranking

Each proposed indicator that met with disagreement due to differing rankings in all four categories was either completely eliminated in round one or modified based on suggested changes and modifications by the panelists. In round two, the panelist received a direct email survey of the modified quality indicators hosted by Qualtrics (Provo, Utah, USA). Panelists re-ranked each modified indicator within the four categories (importance, scientific acceptability, usability and feasibility) of appropriateness and these rankings were used as the final assessment of validity. Summary statistics were performed and validity indicators from round two were subsequently compiled with round one, creating the developed achalasia quality indicators. A final face-to-face round to allow for in-person discussion was not performed due to the feasibility for international authors.

3 |. RESULTS

A review of the literature, consensus statements and societal guidelines generated 26 potential quality indicators on achalasia diagnosis and management. A total of 17 (77%) esophageal experts accepted the invitation to participate and rated the proposed quality indicator topics. In round one, experts agreed upon 2 (8%) indicators as valid. Subsequently prior to round two, 19 measures failing to reach agreement in round one were adjusted in wording and context as suggested by the panel members. The remaining five indicators failing to reach agreement were completely removed due to lack of suggestions in wording in addition to high consensus of disagreement within all four categories. Subsequently, in round two experts agreed upon the 19 additional indicators that had been modified and experts rated 10 (53%) of these as valid. At the completion of this two-rounded modified Delphi study, we identified a total of 12 valid achalasia quality indicators based on expert agreement. The data generated during this study are available from the authors upon request.

We identified achalasia quality indicators within several domains, including patient education, treatment options with risk and benefits, diagnosis using esophageal HRM, and treatment options such as the use of botulinum toxin (Botox) for those not considered surgical (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Quality indicators deemed to be valid by consensus opinion from 17 experts using two-round Delphi technique.

| Quality Indicator | Agreement (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Importance | Scientific Acceptability | Usability | Feasibility | |

| IF a patient has dysphagia in the context of suspected achalasia, THEN an endoscopy with esophageal biopsies should be performed to rule out mechanical obstruction or eosinophilic esophagitis. | 94.1 | 88.2 | 94.1 | 94.1 |

| IF symptoms of GERD occur after achalasia treatment, THEN the patient should be treated with an anti-reflux regimen. | 93.3 | 93.3 | 100 | 100 |

| IF a patient with esophageal dysphagia has an endoscopy with esophageal biopsies and the results are unrevealing THEN high- resolution stationary esophageal manometry should be pursued. | 93.8 | 93.8 | 93.8 | 93.8 |

| If manometry is performed, THEN high-resolution technology should be used. | 93.8 | 100 | 100 | 87.5 |

| IF high-resolution manometry is performed, THEN the Chicago classification v3.0 should be used to help define clinically relevant phenotypes using a standardized language. | 93.8 | 93.8 | 93.8 | 100 |

| IF a patient is diagnosed with achalasia, THEN the patient should be educated on all treatment options with a discussion on risk and benefits. | 100 | 100 | 93.8 | 87.5 |

| IF myotomy (surgical or endoscopic) is performed in achalasia, THEN patients should be made aware of the potential risk of developing gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) following myotomy. | 100 | 100.0 | 100 | 93.8 |

| IF a patient diagnosed with achalasia undergoes laparoscopic surgical myotomy, THEN concomitant partial fundoplication can be performed. | 93.8 | 93.8 | 100 | 100 |

| IF a patient with a diagnosis of achalasia is healthy THEN Botox should not be offered as a long-term treatment option. | 100 | 93.8 | 93.8 | 87.5 |

| IF a patient is diagnosed with achalasia and is high risk for surgery or has a short life expectancy, THEN Botox can be considered. | 93.8 | 87.5 | 87.5 | 93.8 |

| IF symptoms due to achalasia return after achalasia treatment, THEN an objective re-evaluation should be completed. | 100.0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| IF a patient diagnosed with achalasia responds to a form of treatment and has recurrent symptoms, THEN the patient will likely need additional endoscopic or surgical therapies in the future. | 93.8 | 93.8 | 87.5 | 87.5 |

Of the 26 original proposed achalasia quality indicators, 14 (54%) quality indicators were determined to have low validity based on expert disagreement. In round one, example of indicators meeting complete disagreement among panel members included topics on barium esophagram if manometry findings are equivocal in addition to application of Eckardt score in measuring symptom severity and response to treatment. In round two after 19 proposed indicators were adjusted in wording and context as suggested by the panel members, indicators with continued low validity included topics on the need to rule out pseudoachalasia in a new achalasia diagnosis or a trial of Botox injection if the diagnosis of achalasia is unclear. Majority of indicators were excluded due to disagreement in all four categories (important, scientific acceptability, usability and feasibility) whereas the recommendation for percutaneous gastrostomy tube in end-stage achalasia had expert disagreement only with respect to feasibility (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Quality indicators determined to have low validity by consensus opinion from 17 experts using two-round Delphi technique.

| Quality Indicator | Agreement (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Importance | Scientific Acceptability | Usability | Feasibility | |

| IF manometry findings are equivocal, THEN esophagogram should be used to assess EGJ morphology and assess esophageal emptying. | 41.2 | 41.2 | 41.2 | 41.2 |

| IF the diagnosis of achalasia is made, THEN the Eckardt score should be documented to help measure symptom severity and response to treatment. | 11.8 | 11.8 | 35.3 | 52.9 |

| IF a patient is diagnosed with achalasia, THEN treatment with hydraulic dilation (ie, EsoFLIP™) is reasonable. | 33.3 | 26.7 | 21.4 | 7.1 |

| IF a patient is treated for a diagnosis of achalasia, THEN symptom improvement should be monitored by Eckardt score. | 13.3 | 20.0 | 26.7 | 40.0 |

| IF symptoms due to achalasia return after achalasia treatment with confirmed achalasia on objective testing, THEN patients are still a candidate for re-treatment with the same or different modality. | 57.1 | 42.9 | 42.9 | 64.3 |

| IF manometry confirms achalasia, THEN a timed barium esophagogram should be pursued to provide objective measure in the evaluation of treatment response. | 50.0 | 31.3 | 43.8 | 50.0 |

| IF a patient is diagnosed with achalasia, THEN pseudoachalasia should be first excluded. | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 43.8 |

| IF a patient is presenting with dysphagia and the diagnosis is unclear for achalasia, THEN a trial of Botox or EndoFLIP technology, if available, can be used for diagnostic purposes. | 43.8 | 25.0 | 31.3 | 31.3 |

| IF a patient undergoes treatment for achalasia, THEN they should be counseled on the chronic nature of the disease and potential risk of progression to end-stage esophagus despite control of symptoms. | 75.0 | 68.8 | 68.8 | 68.8 |

| IF a patient is diagnosed with end-stage achalasia, THEN esophagectomy or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) should be discussed as a treatment option. | 56.3 | 43.8 | 68.8 | 56.3 |

| IF a patient undergoes achalasia treatment and develops classic GERD symptoms, THEN the patient should be empirically treated with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). | 62.5 | 56.3 | 68.8 | 81.3 |

| IF a patient has treated or untreated achalasia, THEN documentation should include counseling on the potential increased relative risk of squamous cell carcinoma. | 43.8 | 31.3 | 31.3 | 37.5 |

| IF a high-risk patient has treated or untreated achalasia, THEN they should undergo squamous cell carcinoma surveillance. | 25.0 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 25.0 |

| IF surveillance for squamous cell carcinoma in achalasia is started in high-risk patients with treated or untreated achalasia, THEN surveillance should extend in duration as long as the benefits of EGD outweigh the risk. | 43.8 | 31.3 | 31.3 | 31.3 |

4 |. DISCUSSION

This study is the first to systematically develop comprehensive quality indicators for gastroenterologists treating achalasia, applying a modified RAND/UCLA Delphi process. Applying two rounds of ranking, the expert panel focused on importance, scientific acceptability, usability and feasibility among proposed quality indicators, and independently agreed with high validity on 12 achalasia quality indicators spanning the domains of patient education, diagnostic evaluation, and treatment options.

Management of achalasia has increased in complexity over time. It remains a rare disease but is frequently under-recognized20 despite recent data demonstrating an increase in incidence.1 The rise in diagnostic and management choices emphasizes the need not just for best practices, but also measurement of the actual care delivered. In general, demonstrating high quality and cost-conscious care has become increasingly important to patients and payers alike as well as being mandated by the Affordable Care Act.21 Future quality programs are likely to focus on clinical care pathways and cross-cutting measures that encompass disease states rather than individual provider activities.22 In this context, diseases such as achalasia that require expertise across a continuum of care and between specialties are important for developing quality benchmarks. This study demonstrates 12 important quality indicators in achalasia management – and in particular topics with agreement and disagreement.

In contrast to guidelines, which help establish best practice recommendations, quality measures denote an even greater emphasis on the level of evidence as well as provide a structure for measuring and reporting on clinical practice.15 While broadly similar, compared to quality measures, quality indicators are generally more conceptual in framework. They frequently describe the clinical concepts involved and perspective from which measurement occurs, but rarely designate the method for measurement (eg, the data source(s) to be used), specify precise population criteria, or include instructions for how the measure is to be used. In this way, quality indicators may form the basis of future quality measure development and help direct quality improvement efforts to improve patient care.

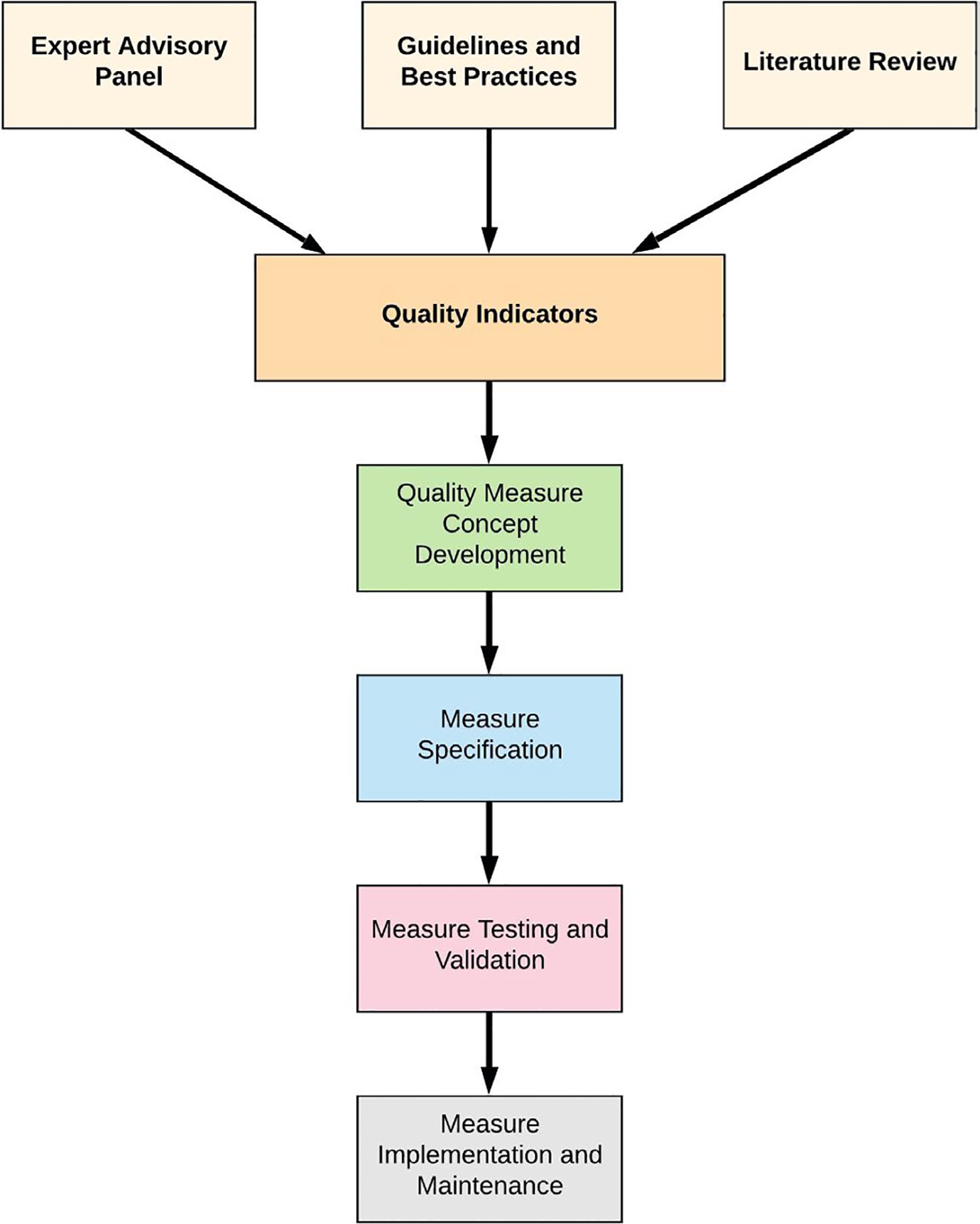

There are several ways in which quality indicators can be generated, though usually this involves a literature review and expert engagement.15 We performed a literature scan of relevant published research and leveraged content guidelines to form the basis for the proposed quality indicators. Furthermore, we engaged content experts during the modified RAND process to satisfy the process of indicator development (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic overview for generating quality indicators and quality measures from literature review, guidelines, and expert input. The current study identified 12 quality indicators that may be further developed as concepts for specified quality measure development.

Ultimately, we found uniform agreement among a panel of academic gastroenterologists that patients with dysphagia should undergo upper endoscopy to diagnose and treat mechanical or inflammatory etiologies. There was also agreement that if this evaluation were unrevealing, an esophageal HRM applying Chicago Classification version 3.0 should be performed. This is consistent with prior data demonstrating HRM improves the overall diagnostic yield for achalasia when compared to conventional manometry.4

An acknowledgment that Botox is acceptable in high-risk patients but not a suitable option for other patients was also identified as a valid indicator. The indicator does not address its use prior to more definitive interventions in healthy patients, particularly in equivocal cases such as when achalasia is suspected but manometric findings support EGJOO,23 or the controversial data demonstrating multiple such injections can attenuate future therapeutic options.24

Additionally, expert panelists identified the importance of discussing risks and benefits of all therapeutic options – as well as risks of developing gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) – following achalasia treatment. This reflects the emerging use of POEM 25,26 and the strong association of GERD complicating post-op care. As an example, data have shown that up to 40% of patients will experience GERD following POEM27 – indicating a risk magnitude warranting an informed discussion ahead of any therapeutic interventions. There was also agreement that patients with continued obstructive symptoms such as dysphagia following initial therapy warrant further work-up and may require endoscopic or surgical therapy.

Despite identifying 12 candidate indicators as valid, there was disagreement among the expert panel across a variety of similar domains. In particular, regularly excluding pseudoachalasia as a cause for symptoms was a source of disagreement. This attitude may reflect the challenges to routinely test for this condition28,29 or a subtle difference in management approach. However, this can be contextualized in the setting of recent data regarding esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction (EGJOO). In this clinical setting, which can represent pseudoachalasia as well as incipient or variant achalasia,30 there is increasing data suggesting such ancillary testing is low-yield and not warranted given the overall small risk,31,32 and likely such an approach does not represent quality in confirmed typical achalasia care.33 Interestingly, FLIP is often used in this scenario but consensus was not reached on this indicator either.

Even with more regulatory attention to patient oriented outcomes and measures, there was also a lack of consensus about the utility of the Eckardt score to either measure disease severity or to assess therapeutic response. This finding was surprising and may be controversial, given its common use in clinical practice and relevance for measuring patient experience. While never formally validated, recent data suggest it has fair reliability and validity based on the dysphagia construct34 and is routinely utilized to establish treatment success in achalasia.35,36

The concept that patients with achalasia who have symptomatic recurrence should be candidates for re-treatment was not identified as valid, which may further reflect a lack of confidence in patient-reported outcomes. However, even the use of objective measures such as timed barium swallow to assess disease response did not yield consensus. Surprisingly, expert panelists did not reach a consensus on the need for chronic acid inhibition with proton pump inhibitors (PPI) following achalasia treatment, which could relate to rates of reflux depending on treatment modality.

Overall, this current report provides important context for understanding markers of high quality care in the management of achalasia patients, although it has some limitations. First, although there are obvious strengths to having an expert panel provide their opinion regarding candidate indicators, these were generated by a comprehensive but not systematic review of the literature. Second, the expert panel provided their input but did not help in the generation of these concepts. While including international experts is a strength of this study, an acknowledged limitation is the lack of in-person meeting. Nonetheless, the contributions of a global cohort should help to generalize our findings. While there are few data to suggest that the quality indicators identified in our study would be more applicable in some locations versus others, treatment approaches may vary by geographic region and could be predicated on insurance coverage as well as expertise. Specifically, European centers may be more likely to treat with pneumatic dilation compared to American colleagues37; in Asia, the use of POEM was more quickly adopted than in other areas.38 Whether this impacts patient outcomes, or adherence to quality indicators, could be the subject of future study.

Additionally, the expert panel comprised of gastroenterologists practicing within tertiary care academic referral centers, and did not include foregut surgeons or gastroenterologists working within a community setting. Therefore, proposed indicators may be subject to external selection bias and may not be generalizable. Last, while this study formally proposes quality indicators for the care of achalasia, we have not yet established the presence of gaps in current practice management and the need for established quality indicators. It is acknowledged that some of the indicators identified may lack sufficient impact to warrant development into full measures. However, the intention of this current study was to find indicators, or concepts, worthy of future measure development rather than actually generate measures. Future studies, including both retrospective evaluations of past care delivery and prospective tracking of performance, will be needed to evaluate for quality gaps in achalasia management. Ideally, these will be among multiple institutions, assessing not only the feasibility of measuring these quality indicators but more importantly to find opportunities for improvement. Ultimately, this initial step in creating and identifying quality indicators encompasses a larger goal to develop comprehensive outcome measures in achalasia management, which will include detailed specification instructions and require formal testing and validation ahead of inclusion in many quality reporting environments.

In conclusion, using an accepted and widely utilized modified RAND/UCLA Delphi process, an expert panel identified 12 quality indicators as valid for the management of achalasia. Future work will require testing and validation of these indicators, which cover multiple domains and provide guidance for comprehensive quality measure development with a focus on clinical outcomes.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Afrin N. Kamal: None, Priya Kathpalia: None, Fouad Otaki: None, Albert J Bredenoord: Received speaker and/or consulting fees from Laborie, Diversatek, Medtronic, Donald O. Castell: None reported, John O. Clarke: Consultant for Isothrive, Medtronic, Pfizer, Regeneron/Sanofi; site principal investigator for Ironwood, Impleo Medical, Gary W. Falk: None, Ronnie Fass: Advisor – Medtronic, Speaker – Diversitek, C. Prakash Gyawali: Consulting: Medtronic, Diversatek, Ironwood, Isothrive, Quintiles, Peter J Kahrilas: Consultant/Advisory Boards: Reckitt Benckiser [Reflux disease (Aluminum hydroxide/magnesium carbonate)]; Ironwood [Irritable bowel (Linaclotide)], Philip O. Katz: None, David A. Katzka: Education consulting for Shire and Takeda, Roberto Penagini: None, John E. Pandolfino: Crospon [IP], Medtronic [Speaking, Consulting, Licensing, Grant], Diversatek [Speaking/Consulting/Grant], Takeda [Consulting]. Ironwood [Consulting, Grant], Sabine Roman: Consulting Medtronic, Research support: Medtronic, Diverstak Healthcare, Joel E. Richter: None, Edoardo Savarino: Consultant: Abbvie, Allergan, MSD, Takeda, Sofar, and Janssen, Teaching and speaking: Medtronic, Reckitt-Benckiser, Malesci, and Zambon, George Triadafilopoulos: None, Michael F. Vaezi: Research support Diversatek; Consulting Pathom, Marcelo F. Vela: Medtronic (consulting), Diversatek (research support), Fouad Otaki: None, David A. Leiman: Chair-elect of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Quality Committee (QC). The current manuscript reflects individual work not completed on behalf, or with the endorsement of, the AGA or the QC, which would evaluate any indicators independently. Education consultant, Medtronic.

REFERENCES

- 1.Samo S, Carlson DA, Gregory DL, Gawel SH, Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ. Incidence and prevalence of achalasia in central chicago, 2004–2014, since the widespread use of high-resolution manometry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(3):366–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey PR, Thomas T, Chandan JS, et al. Incidence, morbidity and mortality of patients with achalasia in England: findings from a study of nationwide hospital and primary care data. Gut. 2019;68(5):790–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boeckxstaens GE. Revisiting Epidemiologic Features of Achalasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(3):374–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roman S, Huot L, Zerbib F, et al. High-resolution manometry improves the diagnosis of esophageal motility disorders in patients with dysphagia: a randomized multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(3):372–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson DA, Pandolfino JE. Personalized approach to the management of achalasia: how we do it. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(10):1556–1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaezi MF, Pandolfino JE, Yadlapati RH, Greer KB, Kavitt RT. ACG Clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(9):1393–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaninotto G, Bennett C, Boeckxstaens G, et al. The 2018 ISDE achalasia guidelines. Dis Esophagus. 2018;31(9):1–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khashab MA, Vela MF, Thosani N, et al. ASGE guideline on the management of achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91(2):213–227 e216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oude Nijhuis R, Zaninotto G, Roman S, et al. European guidelines on achalasia: United European Gastroenterology and European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility recommendations. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;8(1):13–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlson DA, Ravi K, Kahrilas PJ, et al. Diagnosis of esophageal motility disorders: esophageal pressure topography vs. conventional line tracing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(7):pp. 967–977; quiz 978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cardona DM, Peditto S, Singh L, Black-Schaffer S. Updates to medicare’s quality payment program that may impact you. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2020;144(6):679–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahn JM, Gould MK, Krishnan JA, et al. An official American thoracic society workshop report: developing performance measures from clinical practice guidelines. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(4):S186–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams MA, Allen JI, Saini SD. Translating Best Practices To Meaningful Quality Measures: From Measure Conceptualization to Implementation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(5):805–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughes RG.(2008). Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality(US). Rockville (MD). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melmed GY, Siegel CA, Spiegel BM, et al. Quality indicators for inflammatory bowel disease: development of process and outcome measures. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(3):662–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yadlapati R, Gawron AJ, Bilimoria K, et al. Development of quality measures for the care of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(5):874–883 e872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quality Indicators for the Management of Barrett’s Esophagus. Dysplasia, and esophageal adenocarcinoma: international consensus recommendations from the american gastroenterological association symposium. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1599–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD, et al. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method User’s Manual. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2001. https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1269.html. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taskforce AEUQI, Day LW, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for gastrointestinal endoscopy units. VideoGIE. 2017;2(6):119–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niebisch S, Hadzijusufovic E, Mehdorn M, et al. Achalasia-an unnecessary long way to diagnosis. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30(5):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. In. 42 U.S.C. § 18001 et seq.\2010.

- 22.Peabody JSR, Adeyi O, Wang H, Broughton E, Kruk ME. 2017. Chapter 10: Quality of Care. In: Jamison DTGH, Horton S (Eds). Disease Control Priorities: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty.3rd edition. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, The World Bank. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garbarino S, von Isenburg M, Fisher DA, Leiman DA. Management of Functional Esophagogastric Junction Outflow Obstruction: A Systematic Review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54(1):35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Srinivasan RVM, Tutuian R, Katz PO, Castell DO. Prior botulinum toxin injection may compromise outcome of pneumatic dilatation in achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2436–2437. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barbieri LA, Hassan C, Rosati R, Romario UF, Correale L, Repici A. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Efficacy and safety of POEM for achalasia. United European Gastroenterol J. 2015;3(4):325–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kahrilas PJ, Katzka D, Richter JE. Clinical Practice Update: The Use of Per-Oral Endoscopic Myotomy in Achalasia: Expert Review and Best Practice Advice From the AGA Institute. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(5):1205–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Repici A, Fuccio L, Maselli R, et al. GERD after per-oral endoscopic myotomy as compared with Heller’s myotomy with fundoplication: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87(4):934–943 e918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ponds FA, van Raath MI, Mohamed SMM, Smout A, Bredenoord AJ. Diagnostic features of malignancy-associated pseudoachalasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45(11):1449–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kahrilas PJ, Kishk SM, Helm JF, Dodds WJ, Harig JM, Hogan WJ. Comparison of pseudoachalasia and achalasia. Am J Med. 1987;82(3):439–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kahrilas PJ, Boeckxstaens G. The spectrum of achalasia: lessons from studies of pathophysiology and high-resolution manometry. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(5):954–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beveridge CA, Falk GW, Ahuja NK, Yang YX, Metz DC, Lynch KL. Low Yield of Cross-Sectional Imaging in Patients With Esophagogastric Junction Outflow Obstruction. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okeke FC, Raja S, Lynch KL, et al. What is the clinical significance of esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction? evaluation of 60 patients at a tertiary referral center. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu A, Woo M, Nasser Y, et al. Esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction on manometry: Outcomes and lack of benefit from CT and EUS. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31(12):e13712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taft TH, Carlson DA, Triggs J, et al. Evaluating the reliability and construct validity of the Eckardt symptom score as a measure of achalasia severity. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30(6):e13287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perbtani YB, Mramba LK, Yang D, Suarez J, Draganov PV. Life after per-oral endoscopic myotomy: long-term outcomes of quality of life and their association with Eckardt scores. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87(6):1415–1420 e1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boeckxstaens GE, Annese V, des Varannes SB, et al. Pneumatic dilation versus laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy for idiopathic achalasia. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1807–1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boeckxstaens G The European Experience of Achalasia Treatment. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;7(9):609–611. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tuason J, Inoue H. Current status of achalasia management: a review on diagnosis and treatment. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(4):401–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]