Abstract

Background

The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG)-recommended five variant classification categories (pathogenic, likely pathogenic, uncertain significance, likely benign, and benign) have been widely used in medical genetics. However, these guidelines are fundamentally constrained in practice owing to their focus upon Mendelian disease genes and their dichotomous classification of variants as being either causal or not. Herein, we attempt to expand the ACMG guidelines into a general variant classification framework that takes into account not only the continuum of clinical phenotypes, but also the continuum of the variants’ genetic effects, and the different pathological roles of the implicated genes.

Main body

As a disease model, we employed chronic pancreatitis (CP), which manifests clinically as a spectrum from monogenic to multifactorial. Bearing in mind that any general conceptual proposal should be based upon sound data, we focused our analysis on the four most extensively studied CP genes, PRSS1, CFTR, SPINK1 and CTRC. Based upon several cross-gene and cross-variant comparisons, we first assigned the different genes to two distinct categories in terms of disease causation: CP-causing (PRSS1 and SPINK1) and CP-predisposing (CFTR and CTRC). We then employed two new classificatory categories, “predisposing” and “likely predisposing”, to replace ACMG’s “pathogenic” and “likely pathogenic” categories in the context of CP-predisposing genes, thereby classifying all pathologically relevant variants in these genes as “predisposing”. In the case of CP-causing genes, the two new classificatory categories served to extend the five ACMG categories whilst two thresholds (allele frequency and functional) were introduced to discriminate “pathogenic” from “predisposing” variants.

Conclusion

Employing CP as a disease model, we expand ACMG guidelines into a five-category classification system (predisposing, likely predisposing, uncertain significance, likely benign, and benign) and a seven-category classification system (pathogenic, likely pathogenic, predisposing, likely predisposing, uncertain significance, likely benign, and benign) in the context of disease-predisposing and disease-causing genes, respectively. Taken together, the two systems constitute a general variant classification framework that, in principle, should span the entire spectrum of variants in any disease-related gene. The maximal compliance of our five-category and seven-category classification systems with the ACMG guidelines ought to facilitate their practical application.

Keywords: ACMG guidelines, Allele frequency threshold, Allelic heterogeneity, Disease prevalence, Exome sequencing, Genetic heterogeneity, Incomplete penetrance, Multifactorial/complex disease, Pathogenicity, Variant interpretation

Background

Now that the application of exome and genome sequencing in a clinical setting has become fairly routine, we face an increasing challenge in terms of assigning variants to the five discrete classificatory categories (i.e., “pathogenic”, “likely pathogenic”, “uncertain significance”, “likely benign”, and “benign”) [1] recommended by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG-AMP; referred to henceforth as ACMG). A fundamental issue is that the ACMG guidelines were specifically drawn up in order to describe variants identified in genes underlying Mendelian disorders. However, in reality, the etiology of a given disorder may (1) lie on a spectrum from highly penetrant single gene defect to multifactorial disease and (2) involve multiple gene loci that do not make comparable pathological contributions to the disease in question. Moreover, even in genes underlying Mendelian disorders, clinically relevant variants do not readily fall into a discontinuous causal versus benign dichotomy [2]. Indeed, as opined by Wright and colleagues [3], some basic conceptual questions about variant interpretation still remain to be addressed in medical genetics. Thus, should the term “pathogenic” be generally applied to any disease-relevant variant in a given disease-causing gene? When should a pathologically relevant mutation be considered to be a “risk” variant rather than being “pathogenic” in its own right? Various adaptations and refinements of the ACMG guidelines have previously been made in the context of secondary findings derived from clinical exome and genome sequencing [4] as well as in the context of different genes/diseases [5–14] or specific variant types [15]. In addition, a comprehensive refinement of the ACMG variant classification criteria in terms of 40,000 clinically observed variants has also been made [16]. However, in our view, none of these provide a general framework that adequately addresses the aforementioned conceptual issues. Very recently, an “ABC system” (involving both functional and clinical grading steps) has been proposed for the classification of all types of genetic variant (including hypomorphic alleles, imprinted alleles, copy number variants, runs of homozygosity, enhancer variants and variants related to traits) [17]. However, a key limitation of this system is that it relies upon quite different codes (i.e., A, B, C,…) for variant classificatory categories from those used by ACMG, which will likely hamper cross-comparison and may well lead to widespread confusion.

Herein, we propose a general variant classification framework that takes into account the continuum of clinical phenotypes, the continuum of the variants’ genetic effects, and the different pathological roles of the implicated genes, while maximally complying with ACMG guidelines. To this end, we opted to employ chronic pancreatitis (CP) as a disease model. CP, a chronic inflammatory process of the pancreas that leads to irreversible morphological changes and the progressive impairment of both exocrine and endocrine functions, can be caused by both genetic and environmental factors [18, 19]. In common with many other diseases, the process of genetic discovery in CP began with the mapping and identification of a causative gene (i.e., PRSS1 (OMIM #276000; encoding cationic trypsinogen)) for a Mendelian form of the disease, autosomal dominant hereditary pancreatitis [20–23]. Thereafter, a diverse range of variants in more than 10 different genes (for references, see Masson et al. [24]) have been identified in patients with hereditary, familial, idiopathic and/or alcoholic CP (see Main text for disease subtype definitions). These different forms of CP may be considered to reflect a continuum of the disease extending from monogenic to multifactorial [25], thereby rendering CP an archetypal model of a genetic disease (Fig. 1).

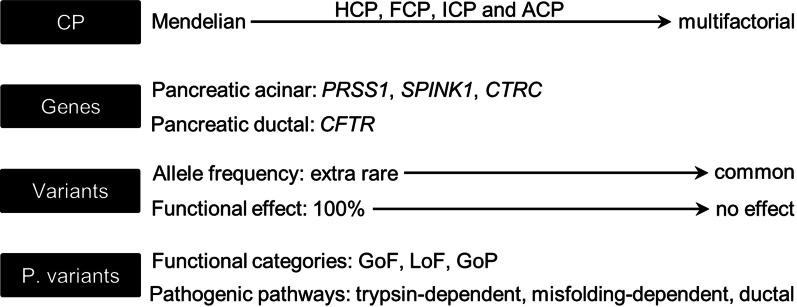

Fig. 1.

Layers of complexity challenging variant classification in CP that were included for analysis in the current study. CP chronic pancreatitis, HCP hereditary CP, FCP familial CP, ICP idiopathic CP, ACP alcoholic CP, P variants, pathological variants, GoF gain-of-function, LoF loss-of-function, GoP gain-of-proteotoxicity

A preprint of this manuscript has been posted on medRxiv [26].

Main text

Genes included in the analysis

A general conceptual proposal should be based upon sound data. We therefore opted to focus our analysis on the first four discovered and most extensively studied CP genes (i.e., PRSS1, CFTR (OMIM #602421; encoding cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator), SPINK1 (OMIM #167790; encoding pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor) and CTRC (OMIM #601405; encoding chymotrypsin C)), each of which is known to harbor a large number of pathologically relevant variants [23, 27–37]. General information about these four genes, including year and method of gene discovery, mRNA reference accession number, length of coding DNA sequence and length of the encoded protein, may be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Some general information about the four CP genes

| Gene (encoded protein) | Year of discovery | Discovery approach | Reference mRNA sequence | Coding sequence (bp) | Protein sequence (aa) | Protein tissue expressiona | Cell type expression in exocrine pancreas | Functional categories of pathologically relevant variantsb | o/e score of pLoF variants (95% CI)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRSS1 (cationic trypsinogen) | 1996 | Positional cloning [23] | NM_002769.5 | 744 | 247 | Specifically expressed in exocrine pancreas | Acinar | GoF (majority); GoP (minority) | 1.31 (0.86–1.86) |

| CFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator) | 1998 | Candidate gene approach based upon the role of CFTR in cystic fibrosis [28, 29] | NM_000492.4 | 4443 | 1480 | Highly expressed in exocrine pancreas and kidney; medially expressed in salivary gland, duodenum and small intestine | Ductal and centroacinar | LoF | 1.09 (0.91–1.31) |

| SPINK1 (pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor) | 2000 | Candidate gene approach stimulated by the PRSS1 finding [30] | NM_001379610.1 | 240 | 79 | Highly expressed in exocrine pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, urinary bladder and appendix | Acinar | LoF | 0.24 (0.09–1.13) |

| CTRC (chymotrypsin C) | 2008 | Candidate gene approach stimulated by the PRSS1 finding [31, 32] | NM_007272.3 | 807 | 268 | Specifically expressed in exocrine pancreas | Acinar | LoF (majority); GoP (minority) | 1.15 (0.78–1.69) |

aa amino acid, bp base-pair, CI confidence interval, CP chronic pancreatitis, GoF gain-of-function, GoP gain-of-proteotoxicity, LoF loss-of-function, o/e observed/expected, pLoF predicted loss-of-function

aIn accordance with the Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org/) [73]

bSee text for details

cIn accordance with gnomAD v2.1.1 (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/) [74]

Variants in the four CP genes considered here

For reported variants in the PRSS1, SPINK1 and CTRC genes, the reader is referred to the Genetic Risk Factors in Chronic Pancreatitis Database [38]. CP-associated variants in the CFTR genes were sought in PubMed using a keyword search (i.e., CFTR plus pancreatitis plus variant or CFTR plus pancreatitis plus mutation; the latest search was performed on 12 April 2022). Data from some original reports were reinterpreted in accordance with the disease subtype definitions outlined below.

Disease subtype definitions

CP cases empirically demonstrated to have a genetic contribution may be classified into four distinct subtypes, namely hereditary CP (HCP), familial CP (FCP), idiopathic CP (ICP) and alcoholic CP (ACP). The first three subtypes were defined in accordance with our previous practice. Specifically, HCP is defined in terms of having three or more affected family members spanning at least two generations, whereas FCP is indicated by a positive family history without satisfying the strict diagnostic criteria for HCP; ICP is indicated when neither a positive family history of pancreatitis nor any obvious external causative risk factors (e.g., excessive alcohol consumption, infection, trauma or drug use) have been reported [25, 27, 39]. ACP was defined in accordance with the original publications, in which it was usually attributed to an alcohol intake of ≥ 80 g/d for a male and ≥ 60 g/d for a female for at least 2 years. “Non-alcoholic CP”, a term used in some publications, may be regarded as being equivalent to ICP, and indeed this has been our previous practice [40]. Finally, it should be emphasized that ICP was defined in terms of the absence of any identifiable etiology prior to genetic analysis.

Classifying the pathologically relevant variants in the four CP genes into three categories in terms of their functional consequences

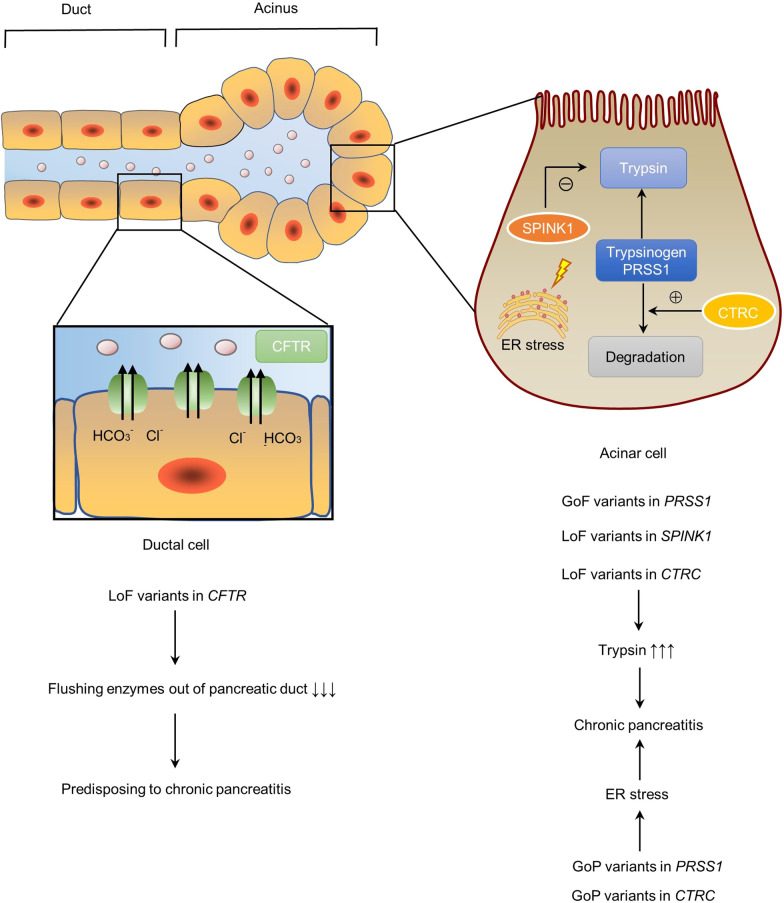

PRSS1, SPINK1 and CTRC are specifically or highly expressed in the acinar cells, whereas CFTR is highly expressed in the ductal cells of the exocrine pancreas (Table 1; Fig. 2). Based upon current knowledge, all pathologically relevant variants in the four CP genes may be classified into three functional categories: gain-of-function (GoF), loss-of-function (LoF) and gain-of-proteotoxicity (GoP). Briefly, GoF variants in PRSS1 result in increased trypsinogen activation and/or increased trypsin stability. These variants, as well as LoF variants in SPINK1 and CTRC (NB. SPINK1 specifically inhibits trypsin, whereas CTRC specifically degrades trypsinogen/trypsin), give rise to increased intrapancreatic trypsin activity or a gain of trypsin within the pancreas, thereby causing or predisposing to CP (trypsin-dependent pathway) [39, 41]. A small subset of pathologically relevant variants in PRSS1 and CTRC induced the misfolding of their corresponding zymogens and elicited endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in the pancreatic acini (misfolding-dependent pathway) [42]; these variants are termed GoP. In the exocrine pancreas, CFTR regulates cAMP-mediated bicarbonate secretion into the pancreatic duct lumen, which dilutes and alkalinizes the protein-rich acinar secretions; LoF variants in CFTR are thought to lead to slowed flushing of trypsinogen/trypsin out of the pancreatic ducts, thereby predisposing to pancreatic injury and CP [25] (termed “ductal pathway” by Mayerle and colleagues [43]). These classifications served as the basis to perform the cross-gene and cross-variant comparisons outlined below.

Fig. 2.

Illustration of the cellular locations of PRSS1, CFTR, CTRC and SPINK1 within the exocrine pancreas and the pathological mechanisms underlying the chronic pancreatitis-related variants in the corresponding genes. ER endoplasmic reticulum, GoF gain-of-function, LoF loss-of-function, GoP gain-of-proteotoxicity

Classifying the four CP genes into two distinct categories in terms of causation

The four CP genes do not contribute equally to the pathophysiology of the exocrine pancreas. To distinguish their roles in the pathogenesis of CP at the gene level, we firstly sought to determine whether the very rare variants [defined as having a minor allele frequency (MAF) of < 0.001 in accordance with Manolio et al. [44] in any gnomAD (Genome Aggregation Database) subpopulation)] were identified in the Mendelian form of CP or HCP in the context of each gene. A MAF cutoff of 0.001 has previously been recommended for filtering variants responsible for dominant Mendelian disorders [45]. The MAF of < 0.001 corresponds to a carrier frequency of < 0.002. It was used here as a very conservative cutoff given that it was more than 600 times higher than the prevalence of HCP, which was estimated to be 0.3/100 000 in Western Countries [46]. The premise was that such variants, where presumed (or experimentally demonstrated) to fall into the aforementioned GoF, GoP or LoF categories, can be confidently interpreted as disease-causing.

PRSS1 was the first CP gene to be identified, with multiple very rare variants including GoF copy number and missense variants and GoP missense variants (n = 12; Table 2) subsequently being reported in many HCP families. By contrast, only a limited number of very rare SPINK1 variants (n = 3; Table 2), and not particularly very rare CFTR and CTRC variants (n = 0; Table 2), have been reported in HCP families. Moreover, the HCP families harboring PRSS1 mutations were generally large, often involving ≥ 4 patients across ≥ 3 generations, whereas the HCP families harboring SPINK1 mutations had at most 3 patients over 3 generations (Table 2). In short, high-confidence disease-causing variants were found in PRSS1 and SPINK1 but not in CFTR and CTRC.

Table 2.

Very rare pathologically relevant variants found in HCP in the context of four CP genes

| Gene | Varianta | Number of HCP families (family description) reportedb | Reference(s) | Biological/functional consequence | gpAF (hspAF) in gnomADc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRSS1 | Trypsinogen gene triplication | 5 (10 patients across 4 generationsd) | Le Maréchal et al. [27] | GoF (gene dosage) [39] | Absent |

| Double “gain-of-function” hybrid variant | 1 (6 patients across 3 generations) | Masson et al. [75] | GoF (gene dosage plus effect of p.Asn29Ile) | Absent | |

| c.47C > T (p.Ala16Val) | 2 (4 patients across 2 generations; 3 patients across 2 generations) | Grocock et al. [76] | GoF (increased activation) [77] | Absent [78] | |

| c.62A > C (p.Asp21Ala) | 1 (5 patients across 3 generations) | Yilmaz et al. [79] | GoF (increased activation) [80] | Absent | |

| c.63_71dup (p.Lys23_Ile24insIleAspLys | 1 (3 patients across 2 generations) | Joergensen et al. [81] | GoF (increased activation) [81] | Absent | |

| c.86A > T (p.Asn29Ile) | The second most frequent variant causing HCP [38]; in the first report, one family had 19 patients across 7 generations [82] | Gorry et al. [82] | GoF (increased activation and stability) [77] | Absent | |

| c.86A > C (p.Asn29Thr) | 1 (8 patients across 3 generations) | Dytz et al. [83] | GoF (increased activation and stability) [77] | Absent | |

| c.116T > C (p.Val39Ala) | 1 (9 patients across 3 generations) | Arduino et al. [84] | GoF (increased stability) [77] | Absent | |

| c.311T > C (p.Leu104Pro) | 2 (both having 3 patients across 3 generations) | Teich et al. [85]; Németh et al. [86] | GoP (intracellular retention and elevation of ER stress marker) [87] | Absent | |

| c.346C > T (p.Arg116Cys) | 2 (3 patients across 2 generations; 3 patients across 3 generations) | Pho-Iam et al. [88]; Kereszturi et al. [89] | GoP (intracellular retention and elevation of ER stress marker) [89] | 0.00007072 (0.0007018, East Asian) | |

| c.365G > A (p.Arg122His) | The most frequent variant causing HCP [38]; in the discovery report, one family had 20 patients across 4 generations [23] | GoF (increased activity) [90, 91] | 0.00001194 (0.00002639, non-Finnish European) | ||

| c.365_366GC > AT (p.Arg122His) | 1 (4 patients across 4 generations) | Howes et al. [92] | Same as above | Absent | |

| CFTR | Not identified | ||||

| SPINK1 | c.27DelC (p.Ser10ValfsTer5) | 1 (3 patients across 2 generations) | Le Maréchal et al. [93] | LoF (predicted complete functional loss) | 0.00001197 (0.00002896, Latino/Admixed American) |

| c.41T > G (p.Leu14Arg) | 2 (both having 3 patients across 3 generations) | Király et al. [94] | LoF (experimentally demonstrated to abolish SPINK1 secretion) [94] | Absent | |

| Deletion of the entire gene | 1 (3 patients across 2 generations) | Masson et al. [95] | LoF (predicted complete functional loss) | Absent | |

| CTRC | Not identified |

CP chronic pancreatitis, gpAF global population allele frequency, GoF gain-of-function, GoP gain-of-proteotoxicity, HCP hereditary CP, hspAF highest subpopulation allele frequency, LoF loss-of-function

aAll are heterozygous. See Table 1 for reference mRNA accession numbers

bData from some original reports were reinterpreted in accordance with our working definition of HCP

cIn accordance with gnomAD v2.1.1 or SVs v2.1 (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/) [74]

dDescribed was the family with the most affected patients

The abovementioned findings may have been influenced by many factors including differences in patient recruitment and mutation analysis protocols between laboratories and different timespans since the first report of CP gene discovery. To confirm or refute these findings, we performed three additional comparative analyses. Firstly, we compared the observed/expected (o/e) scores of predicted LoF (pLoF) variants in the four genes from gnomAD v2.1.1 (Table 1). The o/e score is an indicator of LoF intolerance devised by Karczewski and colleagues [47], low o/e values being indicative of strong intolerance. The highest o/e score was exhibited by PRSS1 (o/e = 1.31); this is understandable because it is predominantly GoF variants in this gene that cause CP, whereas LoF variants in PRSS1 and PRSS2 (encoding anionic trypsinogen, the second major isoform after cationic trypsinogen) are protective with respect to CP [48, 49]. With regard to the latter, we evaluated the pLoF PRSS1 variants in gnomAD v2.1.1. The highest subpopulation allele frequency (hspAF) of such variants, which was found in the case of the c.200 + 1G > A variant, was 0.02871 (African/African American). In the context of the three genes for which LoF variants (or predominantly LoF variants) underlie the disease, CFTR and CTRC have an o/e score of > 1 (1.09 and 1.15, respectively), whereas SPINK1 has an o/e score of < 1 (specifically, 0.24).

Secondly, we compared the odds ratios (ORs) calculated from the aggregated pathologically relevant variants in the three genes for which LoF variants (or predominantly LoF variants) underlie the disease. For reasons of simplicity and comparability, we used data from a German study that analyzed these genes in a large cohort of patients (n = 410–660) and controls (n = 750–1758) [34]. The ORs for CFTR, CTRC and SPINK1 variants were 2.7, 5.3 and 15.6, respectively. In other words, the aggregated pathologically relevant variants in the CFTR and CTRC genes were associated with a much lower genetic effect than those in the SPINK1 gene.

Thirdly, and reinforcing the above point, even the most severe LoF variants in CFTR and CTRC do not exert a very large genetic effect. Thus, for example, CFTR p.Phe508del, the classical cystic fibrosis-causing variant, had an OR of only 2.5 (95% CI 1.7–3.9) for CP [34]. In similar vein, CTRC p.Lys247_Arg254del, which results in a complete loss of CTRC enzymatic activity, had an OR of 6.4 (95% CI 2.3–17.5) [50]. By contrast, the OR for ICP conferred by SPINK1 c.194 + 2T > C, which should result in a ~ 90% functional loss of SPINK1 activity [51, 52], was 59.31 (95% CI 33.93–103.64) based upon data from a Chinese study [36, 40].

Finally, a remarkable difference in terms of phenotype expression was observed between naturally occurring human SPINK1 and CTRC knockouts. Two SPINK1 knockouts, one a homozygous deletion of the entire SPINK1 gene, the other the homozygous insertion of a full-length inverted Alu element into the 3′-untranslated region of the SPINK1 gene (experimentally determined to cause the complete loss of SPINK1 expression), presented with severe exocrine pancreatic insufficiency around 5 months of age [53]. By contrast, a CTRC knockout, homozygous for a deletion of the entire CTRC locus, had been clinically asymptomatic until adulthood [54]. Only at the age of 20 was he incidentally found to have calcifications and cysts in the pancreas; subsequent laboratory tests revealed exocrine pancreatic insufficiency [54]. These highly unusual cases are strongly consistent with SPINK1 exerting a much stronger effect than CTRC in terms of the negative regulation of the level of prematurely activated trypsin within the pancreas.

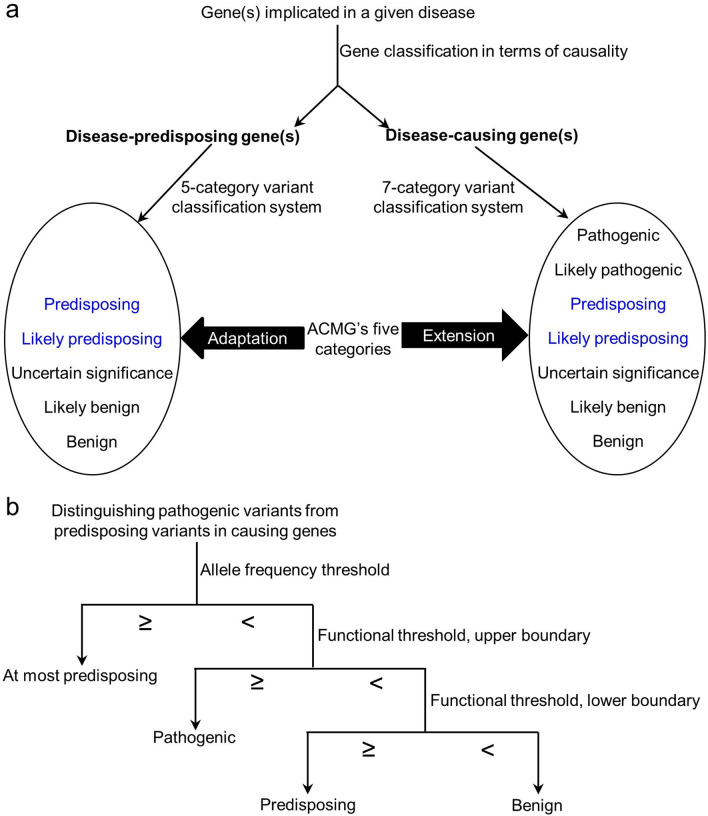

Taking these observations together, we classified PRSS1 and SPINK1 as CP-causing genes and CFTR and CTRC as CP-predisposing genes. This step, generalized to any gene(s) implicated in any disease, is illustrated in Fig. 3a.

Fig. 3.

Key components of our proposed general variant classification framework. a Disease genes were first classified into either “causing” or “predisposing” based upon multiple sources of evidence. Then, minimal extension and adaptation were made to the five ACMG variant classificatory categories in the different gene contexts. The two new categories proposed in this study are highlighted in blue. b Illustration of the use of two thresholds to distinguish pathogenic variants from predisposing variants in disease-causing genes

Adapting ACMG guidelines for the classification of variants in the two CP-predisposing genes

We would propose to change two of the five ACMG categories, “pathogenic” and “likely pathogenic”, to “predisposing” and “likely predisposing” for the purposes of classifying the pathologically relevant variants in the CFTR and CTRC genes. Thus, all CFTR pathologically relevant variants previously known as “cystic fibrosis-causing, severe”, “cystic fibrosis-causing, mild” and “non-cystic fibrosis-causing” [34] will be classified as “predisposing” in the context of CP, with the conventional cystic fibrosis-based categories being provided in parentheses. As for the CTRC variants, we propose to reclassify all “pathogenic” variants listed in the Genetic Risk Factors in Chronic Pancreatitis Database [38] as CP “predisposing”.

A generalized five-category classification system in terms of disease-predisposing genes is illustrated in Fig. 3a.

Extending the ACMG guidelines to classify variants in the two CP-causing genes

It is evident that not all pathologically relevant variants in a given disease-causing gene are causative. To make a distinction at this juncture, we propose to add the above-mentioned two novel categories, “predisposing” and “likely predisposing”, to the five ACMG categories (Fig. 3a). Therefore, the key issue is how to distinguish “pathogenic” from “disease predisposing” among the pathologically relevant variants in the causative genes (Fig. 3b).

Establishing an allele frequency threshold to distinguish pathogenic variants from disease predisposing variants

The relative rarity of a variant is a proxy indicator of its potential pathogenicity [1, 55–59]. But defining an allele frequency threshold above which a pathological variant should be considered too common to cause the disease in question is inherently challenging owing to the uncertainties pertaining to disease prevalence, the variable mode of inheritance, the existence of genetic and allelic heterogeneity, and the issue of incomplete penetrance [58].

Earlier, we used a conservative MAF cutoff of < 0.001 to evaluate high confidence HCP-causing variants. Herein, we further explore this issue by evaluating the population allele frequencies of what we term “gold-standard” pathologically relevant variants in the two CP-causing genes. “Gold-standard” LoF variants in SPINK1 refer to pLoF variants or variants experimentally shown to result in a complete or almost complete (> 95%) loss of SPINK1 function. By contrast, it is impractical to quantify the effect of GoF or GoP variants. Keeping this caveat in mind, “gold-standard” GoF variants in PRSS1 refer to those variants that are very rare and which have been experimentally shown to increase trypsinogen activation and/or trypsin stability, whereas “gold-standard” GoP variants in PRSS1 refer to those variants that are very rare and which have experimentally been shown to reduce protein secretion and elicit ER stress. The global population allele frequency (gpAF) and hspAF of these “gold-standard” variants are provided in Tables 3, 4 and 5. Herein, it should be noted that in the context of “gold-standard” LoF variants in SPINK1 (Table 5), p.Arg67His, which was experimentally shown to cause a complete functional loss of SPINK1 [60], has a hspAF as high as 0.03078. This apparent outlier was excluded from the final analysis.

Table 3.

“Gold-standard” GoF variants in PRSS1

| Variant | gpAF in gnomADa | hspAF in gnomADa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide change | Amino acid change | ||

| Triplication CNV | Absent | ||

| Duplication CNV | Absent | ||

| Double “gain-of-function” CNV | Absent | ||

| c.47C > T | p.Ala16Val | Absent [78] | |

| c.49C > A | p.Pro17Thr | Absent | |

| c.56A > C | p.Asp19Ala | Absent | |

| c.62A > C | p.Asp21Ala | Absent | |

| c.65A > G | p.Asp22Gly | Absent | |

| c.68A > G | p.Lys23Arg | Absent | |

| c.63_71dup | p.Lys23_Ile24insIleAspLys | Absent | |

| c.86A > T | p.Asn29Ile | Absent | |

| PRSS1-PRSS2 hybrid (gene conversion) | p.Asn29Ile + p.Asn54Ser | Absent | |

| c.86A > C | p.Asn29Thr | Absent | |

| PRSS1-PRSS2 hybrid (gene conversion) | p.Asn29Ile + p.Asn54Ser | Absent | |

| c.116 T > C | p.Val39Ala | Absent | |

| c.276G > T | p.Lys92Asn | 0.000007953 | 0.00006152 (African/African American) |

| c.364C > T | p.Arg122Cys | 0.00001988 | 0.00003517 (non-Finnish European) |

| c.365G > A | p.Arg122His | 0.00001194 | 0.00002639 (non-Finnish European) |

| c.365_366GC > AT | p.Arg122His | Absent | |

See the Genetic Risk Factors in Chronic Pancreatitis Database [38] for original genetic and functional analysis reports

GoF gain-of-function, gpAF global population allele frequency, hspAF highest subpopulation allele frequency

aIn accordance with gnomAD v2.1.1 or SVs v2.1 (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/) [74]

Table 4.

“Gold-standard” GoP variants in PRSS1

| Variant | gpAF in gnomADa | hspAF in gnomADa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide change | Amino acid change | ||

| c.311T > C | p.Leu104Pro | Absent | |

| c.346C > T | p.Arg116Cys | 0.00007072 | 0.0007018 (East Asian) |

| c.415T > A | p.Cys139Ser | Absent | |

| c.416G > T | p.Cys139Phe | Absent | |

See the Genetic Risk Factors in Chronic Pancreatitis Database [38] for original genetic and functional analysis reports

GoP gain-of-proteotoxicity, gpAF global population allele frequency, hspAF highest subpopulation allele frequency

aIn accordance with gnomAD v2.1.1 or SVs v2.1 (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/) [74]

Table 5.

“Gold-standard” LoF variants in SPINK1

| Variant | gpAF in gnomADa | hspAF in gnomADa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide change | Amino acid change | ||

| Presumed complete functional loss | |||

| c.-28,211_*2,066del | Absent | ||

| c.-15,969_*7,702del | Absent | ||

| c.-320_c.55 + 961del | Absent | ||

| c.2 T > G | p.Met1? | Absent | |

| c.2 T > C | p.Met1? | Absent | |

| c.27delC | p.Ser10ValfsTer5 | 0.00001197 | 0.00002896 (Latino/Admixed American) |

| c.55 + 1G > A | Absent | ||

| c.87 + 1G > A | Absent | ||

| c.98_99insA | p.Tyr33Ter | Absent | |

| c.177delG | p.Val60TyrfsTer35 | Absent | |

| c.194 + 1G > A | Absent | ||

| Experimentally demonstrated complete or almost complete functional loss | |||

| c.41T > C | p.Leu14Pro | Absent | |

| c.41T > G | p.Leu14Arg | Absent | |

| c.123G > C | p.Lys41Asnb | Absent | |

| c.143G > A | p.Gly48Glu | Absent | |

| c.150T > G | p.Asp50Glu | 0.000003991 | 0.000008834 (non-Finnish European) |

| c.160T > C | p.Tyr54His | Absent | |

| c.190A > G | p.Asn64Asp | Absent | |

| c.198A > C | p.Lys66Asn | 0.0002272 | 0.0004129 (non-Finnish European) |

| c.199C > T | p.Arg67Cys | Absent | |

| c.200G > A | p.Arg67Hisc | 0.003187 | 0.03078 (African/African American) |

| c.206C > T | p.Thr69Ile | 0.00001198 | 0.0001635 (East Asian) |

| c.236G > T | p.Cys79Phe | Absent | |

| c.*14_c.*15ins359 | Absent | ||

See the Genetic Risk Factors in Chronic Pancreatitis Database [38] for original genetic and functional analysis reports

gpAF global population allele frequency, hspAF highest subpopulation allele frequency, LoF loss-of-function

aIn accordance with gnomAD v2.1.1 or SVs v2.1 (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/) [74]

bFunctional analysis of this variant was performed in ref. [66]

cThis variant was regarded as an outlier and was therefore excluded from the final analysis

As shown in Tables 3, 4 and 5, only a small subset (precisely 19% (9/47)) of the “gold-standard” pathologically relevant variants in the two CP-causing genes were found in normal populations. Of this small set of variants, the high-confidence HCP-causing PRSS1 p.Arg116Cys has the highest hspAF (0.0007018). We therefore elected to adopt the previously recommended allele frequency of 0.001 for the filtering of dominant Mendelian disorders [45] as the threshold hspAF for differentiating pathogenic from disease predisposing variants in the PRSS1 and SPINK1 genes.

Establishing gene-specific functional thresholds to distinguish pathogenic variants from disease predisposing variants

In the two CP-causing genes, not all pathologically relevant variants with a hspAF of < 0.001 can be pathogenic due to their different functional effects. Taking into consideration the different roles of the two genes, we attempted to set gene-specific functional thresholds that would allow pathogenic variants to be distinguished from disease predisposing variants.

As mentioned earlier, it is impractical to quantify the functional effect of GoF or GoP variants in the PRSS1 gene. Given (1) the central role of PRSS1 in the trypsin-dependent pathway and (2) that PRSS1 is the most abundantly expressed of the pancreatic zymogen genes, we would tentatively classify all PRSS1 variants with an allele frequency of < 0.001 that have been experimentally demonstrated to be consistent with a GoF or GOP mechanism, as pathogenic.

We would further propose that those SPINK1 variants with an allele frequency of < 0.001, that were either presumed or experimentally shown to cause a complete or almost complete functional loss (> 95%) of SPINK1, should be regarded as pathogenic. Additional support for this proposal came from the SPINK1 c.194 + 2T > C variant which is associated with a ~ 90% functional loss of SPINK1 [51, 52] but has an hspAF of 0.003335 in the East Asian population. As for the lower boundary of functional loss for defining disease predisposing SPINK1 variants, we would tentatively propose a functional loss of at least 10%.

Use of the two newly established thresholds to reclassify several variants in the two CP-causative genes

In the Genetic Risk Factors in Chronic Pancreatitis Database [38], variants in the PRSS1 and SPINK1 genes are systematically classified in accordance with the ACMG recommended five categories with the addition of a new “protective” category. Herein, we mainly focus on the missense variants and pLoF variants that were classified as “pathogenic” or “likely pathogenic” in PRSS1 and SPINK1 by the Database [38]. Utilizing the newly established thresholds would result in the reclassification of multiple variants, as described below.

In the context of PRSS1, p.Gly208Ala would be reclassified from “pathogenic” to “disease predisposing”, primarily because its hspAF is 0.00987 (East Asian), ~ 10 times higher than the 0.001 allele frequency threshold; moreover, functional assays revealed that this variant had only a moderate impact on secretion [61]; finally, in terms of its genetic effect, it had an OR of only 4.92 for ICP [36, 40]. The “pathogenic” p.Lys92Asn and p.Ser124Ser variants would be reclassified as “likely pathogenic” since both showed moderate impact on secretion but no data on ER stress were available. We would also propose to reclassify the “protective” LoF variants p.Tyr37Ter and c.200 + 1G > A as “benign”, with a view to avoiding the addition of a clinically irrelevant category to the five pre-existing ACMG categories. Nevertheless, to distinguish them from the classical “benign” variants (e.g., missense variants that have been experimentally demonstrated to be functionally neutral), the “protective” nature of these LoF variants in PRSS1 may be specified in parentheses after the “benign” category (Table 6). Employing the same line of reasoning, we would propose to use the risk allele rather than the protective allele for variant classification with respect to the common promoter variant located at c.-204, upstream of the translational initiation codon of PRSS1 [62–64]. Consequently, c.-204C > A (protective) should be described as c.-204A > C (predisposing).

Table 6.

Illustrative examples of additions to the main classification categories in the context of PRSS1 variants

| Variant | Classification |

|---|---|

| Trypsinogen gene triplication | Pathogenic (causes HCP; has also been noted in cases with FCP and ICP; causes the disease via a gene dosage effect) [39] |

| p.Ala16Val | Pathogenic (highly variable penetrance [38]; causes disease via the trypsin-dependent pathway) [77] |

| p.Arg122His | Pathogenic (the most frequent variant found in HCP families [38]; causes disease via the trypsin-dependent pathway) [41, 91] |

| p.Gly208Ala | Predisposing (Asian population-specific variant, with an allele frequency of 0.009873 in East Asians; odds ratio for ICP, 4.92 [36]; may predispose to CP through the misfolding pathway [42] since it causes a moderate effect on secretion [61]) |

| c.-204A > C | Predisposing (a common promoter polymorphism whose pathological authenticity is supported by both in silico and functional data; exerts a moderate genetic effect; odds ratio for ICP, 1.28) [64] |

| c.200 + 1G > A | Benign (a loss-of-function mutation that was found in normal controls; protective against CP) |

CP chronic pancreatitis, FCP familial CP, GoF gain-of-function, HCP hereditary CP, ICP idiopathic CP

In the context of SPINK1 variants, there would be three noteworthy reclassifications. First, the abovementioned c.194 + 2T > C should be reclassified from “pathogenic” to “predisposing”. Second, the extensively studied p.Asn34Ser variant should be reclassified from “likely benign” to “benign’ [65–67]. Third, the functional enhancer variant, c.-4141G > T, which is in extensive linkage disequilibrium with p.Asn34Ser [65, 67], should be reclassified from “likely pathogenic” to “predisposing” owing to its hspAF of ~ 0.01975 (South Asia). Additionally, a very rare SPINK1 variant, p.Arg65Gln, which has been shown to cause a ~ 50% functional loss of SPINK1 [68, 69], would be also reclassified from “pathogenic” to “predisposing” based upon the above established SPINK1-specific functional threshold (functional loss of > 10 to < 95%).

Further additions to the general classification framework

As mentioned above, it is desirable to provide necessary information (such as detection frequency in patients, reported OR, functional analytic data, etc.) about the pathologically relevant variant in question in parentheses immediately after the variant’s principal classification. The main reason is that, for any given disease gene, there are often a large number of variants classified as either “pathogenic” or “predisposing”. We provide illustrative examples in the context of PRSS1 variants in Table 6.

Discussion

Employing CP as a disease model and focusing on the four firmly established CP genes, we propose a general variant classification framework that both complements and extends the widely used five ACMG-recommended categories (Fig. 3). To this end, the first step taken was to classify the pathologically relevant variants in the different genes into three functional categories, GoF, LoF and GoP. This allowed us to appropriately perform several cross-gene and cross-variant comparisons, which then enabled us to assign the different genes into two distinct categories in terms of causality; causative genes refer to those genes in which a severe variant can cause CP on its own, whereas disease predisposing genes refer to those genes in which even a highly deleterious variant cannot cause CP by itself. This dichotomy is pivotal because it paves the way for both extension and/or adaptation of the ACMG guidelines (Fig. 3a). Herein, we would like to emphasize that, in common with many term definitions, our currently defined “CP-causing genes” and “CP-predisposing genes” are context-dependent. Thus, we did not consider CFTR or CTRC as CP-causing genes even if homozygous or compound heterozygous variants in both of them or CFTR/CTRC trans-heterozygosity might cause CP.

Another key feature of our proposed conceptual framework was the adoption of two thresholds (allele frequency and functional) to differentiate true pathogenic (disease causing) variants from predisposing variants in the context of disease-causing genes, thereby addressing the basic questions raised by Wright et al. [3]. We readily concede that the threshold values we settled upon, particularly the functional ones, may have to be adjusted once more data become available.

Herein, we used CP as a disease model with which to generate a general variant classification framework. This does not mean that a given disorder necessarily always involves both disease causing and disease predisposing genes. Indeed, our analytical approach may well not be applicable across the board to other disease states and in other gene contexts. Rather, it is proposal for a general framework which comprises a five-category classification system for disease-predisposing genes and a seven-category classification system for disease-causing genes, that could potentially be applied to all possible situations. For example, in a truly polygenic disease (i.e., a genetic disorder resulting from the combined action of two or more genes, the implicated genes may in principle be termed disease-predisposing genes and all pathologically relevant variants within these genes may accordingly be classified as “disease-predisposing”. Moreover, in classical autosomal dominant diseases (e.g., autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) [70]) or autosomal recessive diseases (e.g., cystic fibrosis [71]), the so-called modifier genes may in principle be termed disease-predisposing genes. Further, the so-called hypomorphic alleles in some disease-causing genes may be classified as “predisposing” (e.g., [72]). Herein, we would like to emphasize that the assignation of a disease gene as disease-causing or disease-predisposing and the establishment of the allele frequency and functional thresholds (in the context of disease-causing genes) would need to be made on a gene-by-gene basis and would require close collaboration between researchers and clinicians with specific expertise in the diseases/genes in question.

It is worth reiterating that this study aimed to provide a proof-of-concept, general variant classification framework, a process facilitated by the availability of functional data for most missense variants in the PRSS1, SPINK1 and CTRC genes. It was not however intended to address in detail the specific criteria and rules used to define each variant classificatory category. Therefore, our proposed framework should not be expected to solve all problems of variant interpretation that are likely to be encountered in a clinical exome or genome sequencing context.

It is also worth emphasizing that our proposed general variant classification framework was aimed at classifying variants at individual levels. It was beyond the scope of this study to attempt to classify variants in combination even although such situations are routinely encountered in clinical practice.

The salient point was that it was found to be unnecessary to make more than minimal changes to the five ACMG variant classification categories. As such, all the principles and rules established by ACMG may be readily used and/or adapted for variant classification using our proposed framework.

Conclusions

In summary, we propose a general classification framework for pathologically relevant variants that successfully addresses key issues pertaining to variant interpretation in medical genetics. The maximal compliance of our proposed five-category and seven-category schemes (for disease-predisposing and disease-causing genes, respectively) with the ACMG guidelines should in principle render these schemes applicable for variant classification in other well-established disease genes.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ACMG-AMP

The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology

- ACP

Alcoholic chronic pancreatitis

- CP

Chronic pancreatitis

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- FCP

Familial chronic pancreatitis

- GoF

Gain-of-function

- GoP

Gain-of-proteotoxicity

- gpAF

Global population allele frequency

- HCP

Hereditary chronic pancreatitis

- hspAF

Highest subpopulation allele frequency

- ICP

Idiopathic chronic pancreatitis

- LoF

Loss-of-function

- MAF

Minor allele frequency

- o/e

Observed/expected

- OR

Odds ratio

- PLoF

Predicted loss-of-function

Author contributions

EM and W-BZ contributed to the study design, data collation and analysis, and assisted in writing the paper. EG, DNC, GLG, YF, NP and VR analyzed the data and critically revised the manuscript with important intellectual input. CF and ZL contributed to the concept of the study, analyzed the data and critically revised the manuscript. JMC conceived and coordinated the study, performed data collation and analysis, and drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript submitted.

Funding

This work was performed within the framework of the Sino-French GREPAN (Genetic REsearch on PANcreatitis) study and was supported by the INSERM (Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale) Cross-Cutting Project GOLD (GenOmic variability in heaLth and Disease), the Association des Pancréatites Chroniques Héréditaires and the Association Gaétan Saleün, France; and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82120108006 [Z.L.]). N.P. received a 1-year visiting PhD student scholarship from the China Scholarship Council, the Ministry of Education of China (No. 202006190267). The funding sources did not play any role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data or in the writing of the report.

Availability of data and materials

All supporting data are available within the article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Emmanuelle Masson and Wen-Bin Zou share co-first authorship

References

- 1.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minikel EV, Vallabh SM, Lek M, Estrada K, Samocha KE, Sathirapongsasuti JF, et al. Quantifying prion disease penetrance using large population control cohorts. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(322):322ra9. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad5169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright CF, West B, Tuke M, Jones SE, Patel K, Laver TW, et al. Assessing the pathogenicity, penetrance, and expressivity of putative disease-causing variants in a population setting. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;104(2):275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnston JJ, Brennan ML, Radenbaugh B, Yoo SJ, Hernandez SM, Core NRP, et al. The ACMG SF v3.0 gene list increases returnable variant detection by 22% when compared with v2.0 in the ClinSeq cohort. Genet Med. 2022;24(3):736–43. doi: 10.1016/j.gim.2021.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly MA, Caleshu C, Morales A, Buchan J, Wolf Z, Harrison SM, et al. Adaptation and validation of the ACMG/AMP variant classification framework for MYH7-associated inherited cardiomyopathies: recommendations by ClinGen’s inherited cardiomyopathy expert panel. Genet Med. 2018;20(3):351–359. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morales A, Kinnamon DD, Jordan E, Platt J, Vatta M, Dorschner MO, et al. Variant interpretation for dilated cardiomyopathy: refinement of the American college of medical genetics and genomics/ClinGen guidelines for the DCM precision medicine study. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2020;13(2):e002480. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGEN.119.002480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kountouris P, Stephanou C, Lederer CW, Traeger-Synodinos J, Bento C, Harteveld CL, et al. Adapting the ACMG/AMP variant classification framework: a perspective from the ClinGen hemoglobinopathy variant curation expert panel. Hum Mutat. 2022;43(8):1089–1096. doi: 10.1002/humu.24280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Girodon E, Rebours V, Chen JM, Pagin A, Levy P, Férec C, et al. Clinical interpretation of PRSS1 variants in patients with pancreatitis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2021;45(1):101497. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2020.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Girodon E, Rebours V, Chen JM, Pagin A, Lévy P, Férec C, et al. Clinical interpretation of SPINK1 and CTRC variants in pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2020;20(7):1354–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2020.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fortuno C, Mester J, Pesaran T, Weitzel JN, Dolinsky J, Yussuf A, et al. Suggested application of HER2+ breast tumor phenotype for germline TP53 variant classification within ACMG/AMP guidelines. Hum Mutat. 2020;41(9):1555–1562. doi: 10.1002/humu.24060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee K, Krempely K, Roberts ME, Anderson MJ, Carneiro F, Chao E, et al. Specifications of the ACMG/AMP variant curation guidelines for the analysis of germline CDH1 sequence variants. Hum Mutat. 2018;39(11):1553–1568. doi: 10.1002/humu.23650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mester JL, Ghosh R, Pesaran T, Huether R, Karam R, Hruska KS, et al. Gene-specific criteria for PTEN variant curation: recommendations from the ClinGen PTEN expert panel. Hum Mutat. 2018;39(11):1581–1592. doi: 10.1002/humu.23636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oza AM, DiStefano MT, Hemphill SE, Cushman BJ, Grant AR, Siegert RK, et al. Expert specification of the ACMG/AMP variant interpretation guidelines for genetic hearing loss. Hum Mutat. 2018;39(11):1593–1613. doi: 10.1002/humu.23630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parsons MT, Tudini E, Li H, Hahnen E, Wappenschmidt B, Feliubadalo L, et al. Large scale multifactorial likelihood quantitative analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants: an ENIGMA resource to support clinical variant classification. Hum Mutat. 2019;40(9):1557–1578. doi: 10.1002/humu.23818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandt T, Sack LM, Arjona D, Tan D, Mei H, Cui H, et al. Adapting ACMG/AMP sequence variant classification guidelines for single-gene copy number variants. Genet Med. 2020;22(2):336–344. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0655-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nykamp K, Anderson M, Powers M, Garcia J, Herrera B, Ho YY, et al. Sherloc: a comprehensive refinement of the ACMG-AMP variant classification criteria. Genet Med. 2017;19(10):1105–1117. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houge G, Laner A, Cirak S, de Leeuw N, Scheffer H, den Dunnen JT. Stepwise ABC system for classification of any type of genetic variant. Eur J Hum Genet. 2022;30(2):150–159. doi: 10.1038/s41431-021-00903-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleeff J, Whitcomb DC, Shimosegawa T, Esposito I, Lerch MM, Gress T, et al. Chronic pancreatitis. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2017;3:17060. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ru N, Xu XN, Cao Y, Zhu JH, Hu LH, Wu SY, et al. The impacts of genetic and environmental factors on the progression of chronic pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(6):e1378–e1387. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Bodic L, Bignon JD, Raguenes O, Mercier B, Georgelin T, Schnee M, et al. The hereditary pancreatitis gene maps to long arm of chromosome 7. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5(4):549–554. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.4.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitcomb DC, Preston RA, Aston CE, Sossenheimer MJ, Barua PS, Zhang Y, et al. A gene for hereditary pancreatitis maps to chromosome 7q35. Gastroenterology. 1996;110(6):1975–1980. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8964426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pandya A, Blanton SH, Landa B, Javaheri R, Melvin E, Nance WE, et al. Linkage studies in a large kindred with hereditary pancreatitis confirms mapping of the gene to a 16-cM region on 7q. Genomics. 1996;38(2):227–230. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whitcomb DC, Gorry MC, Preston RA, Furey W, Sossenheimer MJ, Ulrich CD, et al. Hereditary pancreatitis is caused by a mutation in the cationic trypsinogen gene. Nat Genet. 1996;14(2):141–145. doi: 10.1038/ng1096-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masson E, Rebours V, Buscail L, Frete F, Pagenault M, Lachaux A, et al. The reversion variant (p.Arg90Leu) at the evolutionarily adaptive p.Arg90 site in CELA3B predisposes to chronic pancreatitis. Hum Mutat. 2021;42(4):385–91. doi: 10.1002/humu.24178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen JM, Férec C. Chronic pancreatitis: genetics and pathogenesis. Annu Rev Genom Hum Genet. 2009;10:63–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082908-150009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masson E, Zou WB, Génin E, Cooper DN, Le Gac G, Fichou Y, et al. A proposed general variant classification framework using chronic pancreatitis as a disease model. medRxiv 2022.06.03.22275950; 10.1101/2022.06.03.22275950 2022.

- 27.Le Maréchal C, Masson E, Chen JM, Morel F, Ruszniewski P, Levy P, et al. Hereditary pancreatitis caused by triplication of the trypsinogen locus. Nat Genet. 2006;38(12):1372–1374. doi: 10.1038/ng1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohn JA, Friedman KJ, Noone PG, Knowles MR, Silverman LM, Jowell PS. Relation between mutations of the cystic fibrosis gene and idiopathic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(10):653–658. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809033391002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharer N, Schwarz M, Malone G, Howarth A, Painter J, Super M, et al. Mutations of the cystic fibrosis gene in patients with chronic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(10):645–652. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809033391001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Witt H, Luck W, Hennies HC, Classen M, Kage A, Lass U, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the serine protease inhibitor, Kazal type 1 are associated with chronic pancreatitis. Nat Genet. 2000;25(2):213–216. doi: 10.1038/76088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosendahl J, Witt H, Szmola R, Bhatia E, Ozsvari B, Landt O, et al. Chymotrypsin C (CTRC) variants that diminish activity or secretion are associated with chronic pancreatitis. Nat Genet. 2008;40(1):78–82. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masson E, Chen JM, Scotet V, Le Maréchal C, Férec C. Association of rare chymotrypsinogen C (CTRC) gene variations in patients with idiopathic chronic pancreatitis. Hum Genet. 2008;123(1):83–91. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0459-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masson E, Chen JM, Audrézet MP, Cooper DN, Férec C. A conservative assessment of the major genetic causes of idiopathic chronic pancreatitis: data from a comprehensive analysis of PRSS1, SPINK1, CTRC and CFTR genes in 253 young French patients. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e73522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosendahl J, Landt O, Bernadova J, Kovacs P, Teich N, Bodeker H, et al. CFTR, SPINK1, CTRC and PRSS1 variants in chronic pancreatitis: is the role of mutated CFTR overestimated? Gut. 2013;62(4):582–592. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jalaly NY, Moran RA, Fargahi F, Khashab MA, Kamal A, Lennon AM, et al. An evaluation of factors associated with pathogenic PRSS1, SPINK1, CTFR, and/or CTRC genetic variants in patients with idiopathic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(8):1320–1329. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zou WB, Tang XY, Zhou DZ, Qian YY, Hu LH, Yu FF, et al. SPINK1, PRSS1, CTRC, and CFTR genotypes influence disease onset and clinical outcomes in chronic pancreatitis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2018;9(11):204. doi: 10.1038/s41424-018-0069-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cho SM, Shin S, Lee KA. PRSS1, SPINK1, CFTR, and CTRC pathogenic variants in Korean patients with idiopathic pancreatitis. Ann Lab Med. 2016;36(6):555–560. doi: 10.3343/alm.2016.36.6.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nemeth BC, Sahin-Tóth M. The Genetic Risk Factors in Chronic Pancreatitis Database. http://www.pancreasgenetics.org/index.php. Accessed 23 May 2022.

- 39.Zou WB, Cooper DN, Masson E, Pu N, Liao Z, Férec C, et al. Trypsinogen (PRSS1 and PRSS2) gene dosage correlates with pancreatitis risk across genetic and transgenic studies: a systematic review and re-analysis. Hum Genet. 2022;141(8):1327–1338. doi: 10.1007/s00439-022-02436-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen JM, Herzig AF, Genin E, Masson E, Cooper DN, Férec C. Scale and scope of gene-alcohol interactions in chronic pancreatitis: a systematic review. Genes (Basel) 2021;12(4):471. doi: 10.3390/genes12040471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hegyi E, Sahin-Tóth M. Genetic risk in chronic pancreatitis: the trypsin-dependent pathway. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(7):1692–1701. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4601-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sahin-Tóth M. Genetic risk in chronic pancreatitis: the misfolding-dependent pathway. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2017;33(5):390–395. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mayerle J, Sendler M, Hegyi E, Beyer G, Lerch MM, Sahin-Toth M. Genetics, cell biology, and pathophysiology of pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(7):1951–68.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.11.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manolio TA, Collins FS, Cox NJ, Goldstein DB, Hindorff LA, Hunter DJ, et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature. 2009;461(7265):747–753. doi: 10.1038/nature08494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bamshad MJ, Ng SB, Bigham AW, Tabor HK, Emond MJ, Nickerson DA, et al. Exome sequencing as a tool for Mendelian disease gene discovery. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(11):745–755. doi: 10.1038/nrg3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rebours V, Levy P, Ruszniewski P. An overview of hereditary pancreatitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44(1):8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, Cummings BB, Alfoldi J, Wang Q, et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581(7809):434–443. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen JM, Le Maréchal C, Lucas D, Raguénès O, Férec C. "Loss of function" mutations in the cationic trypsinogen gene (PRSS1) may act as a protective factor against pancreatitis. Mol Genet Metab. 2003;79(1):67–70. doi: 10.1016/S1096-7192(03)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Witt H, Sahin-Tóth M, Landt O, Chen JM, Kahne T, Drenth JP, et al. A degradation-sensitive anionic trypsinogen (PRSS2) variant protects against chronic pancreatitis. Nat Genet. 2006;38(6):668–673. doi: 10.1038/ng1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beer S, Zhou J, Szabo A, Keiles S, Chandak GR, Witt H, et al. Comprehensive functional analysis of chymotrypsin C (CTRC) variants reveals distinct loss-of-function mechanisms associated with pancreatitis risk. Gut. 2013;62(11):1616–1624. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kume K, Masamune A, Kikuta K, Shimosegawa T. [-215G>A; IVS3+2T>C] mutation in the SPINK1 gene causes exon 3 skipping and loss of the trypsin binding site. Gut. 2006;55(8):1214. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.095752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zou WB, Boulling A, Masson E, Cooper DN, Liao Z, Li ZS, et al. Clarifying the clinical relevance of SPINK1 intronic variants in chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 2016;65(5):884–886. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Venet T, Masson E, Talbotec C, Billiemaz K, Touraine R, Gay C, et al. Severe infantile isolated exocrine pancreatic insufficiency caused by the complete functional loss of the SPINK1 gene. Hum Mutat. 2017;38(12):1660–1665. doi: 10.1002/humu.23343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Masson E, Hammel P, Garceau C, Benech C, Quemener-Redon S, Chen JM, et al. Characterization of two deletions of the CTRC locus. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;109(3):296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Whiffin N, Minikel E, Walsh R, O'Donnell-Luria AH, Karczewski K, Ing AY, et al. Using high-resolution variant frequencies to empower clinical genome interpretation. Genet Med. 2017;19(10):1151–1158. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ragoussis V, Pagnamenta AT, Haines RL, Giacopuzzi E, McClatchey MA, Sampson JR, et al. Using data from the 100,000 Genomes Project to resolve conflicting interpretations of a recurrent TUBB2A mutation. J Med Genet. 2022;59(4):366–369. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2020-107528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hanany M, Sharon D. Allele frequency analysis of variants reported to cause autosomal dominant inherited retinal diseases question the involvement of 19% of genes and 10% of reported pathogenic variants. J Med Genet. 2019;56(8):536–542. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2018-105971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kobayashi Y, Yang S, Nykamp K, Garcia J, Lincoln SE, Topper SE. Pathogenic variant burden in the ExAC database: an empirical approach to evaluating population data for clinical variant interpretation. Genome Med. 2017;9(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0403-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Minikel EV, MacArthur DG. Publicly available data provide evidence against NR1H3 R415Q causing multiple sclerosis. Neuron. 2016;92(2):336–338. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boulling A, Keiles S, Masson E, Chen JM, Férec C. Functional analysis of eight missense mutations in the SPINK1 gene. Pancreas. 2012;41(2):329–330. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182277b83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schnúr A, Beer S, Witt H, Hegyi P, Sahin-Tóth M. Functional effects of 13 rare PRSS1 variants presumed to cause chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 2014;63(2):337–343. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Whitcomb DC, LaRusch J, Krasinskas AM, Klei L, Smith JP, Brand RE, et al. Common genetic variants in the CLDN2 and PRSS1-PRSS2 loci alter risk for alcohol-related and sporadic pancreatitis. Nat Genet. 2012;44(12):1349–1354. doi: 10.1038/ng.2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boulling A, Sato M, Masson E, Genin E, Chen JM, Férec C. Identification of a functional PRSS1 promoter variant in linkage disequilibrium with the chronic pancreatitis-protecting rs10273639. Gut. 2015;64(11):1837–1838. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Herzig AF, Genin E, Cooper DN, Masson E, Férec C, Chen JM. Role of the common PRSS1-PRSS2 haplotype in alcoholic and non-alcoholic chronic pancreatitis: meta- and re-analyses. Genes (Basel) 2020;11(11):1349. doi: 10.3390/genes11111349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boulling A, Masson E, Zou WB, Paliwal S, Wu H, Issarapu P, et al. Identification of a functional enhancer variant within the chronic pancreatitis-associated SPINK1 c.101A>G (p.Asn34Ser)-containing haplotype. Hum Mutat. 2017;38(8):1014–24. doi: 10.1002/humu.23269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Szabó A, Toldi V, Gazda LD, Demcsak A, Tozser J, Sahin-Tóth M. Defective binding of SPINK1 variants is an uncommon mechanism for impaired trypsin inhibition in chronic pancreatitis. J Biol Chem. 2021;296:100343. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pu N, Masson E, Cooper DN, Genin E, Férec C, Chen JM. Chronic pancreatitis: the true pathogenic culprit within the SPINK1 N34S-containing haplotype is no longer at large. Genes (Basel) 2021;12(11):1683. doi: 10.3390/genes12111683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boulling A, Le Maréchal C, Trouvé P, Raguénès O, Chen JM, Férec C. Functional analysis of pancreatitis-associated missense mutations in the pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (SPINK1) gene. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15(9):936–942. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Király O, Wartmann T, Sahin-Tóth M. Missense mutations in pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (SPINK1) cause intracellular retention and degradation. Gut. 2007;56(10):1433–1438. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.115725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lanktree MB, Haghighi A, di Bari I, Song X, Pei Y. Insights into autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease from genetic studies. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16(5):790–799. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02320220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Butnariu LI, Tarca E, Cojocaru E, Rusu C, Moisa SM, Leon Constantin MM, et al. Genetic modifying factors of cystic fibrosis phenotype: a challenge for modern medicine. J Clin Med. 2021;10(24):5821. doi: 10.3390/jcm10245821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Durkie M, Chong J, Valluru MK, Harris PC, Ong ACM. Biallelic inheritance of hypomorphic PKD1 variants is highly prevalent in very early onset polycystic kidney disease. Genet Med. 2021;23(4):689–697. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-01026-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.The Human Protein Atlas. https://www.proteinatlas.org. Accessed 12 April 2022.

- 74.gnomAD (Genome Aggregation Database). https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/. Accessed 12 April 2022.

- 75.Masson E, Le Maréchal C, Delcenserie R, Chen JM, Férec C. Hereditary pancreatitis caused by a double gain-of-function trypsinogen mutation. Hum Genet. 2008;123(5):521–529. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Grocock CJ, Rebours V, Delhaye MN, Andren-Sandberg A, Weiss FU, Mountford R, et al. The variable phenotype of the p.A16V mutation of cationic trypsinogen (PRSS1) in pancreatitis families. Gut. 2010;59(3):357–63. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.186817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Szabó A, Sahin-Tóth M. Increased activation of hereditary pancreatitis-associated human cationic trypsinogen mutants in presence of chymotrypsin C. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(24):20701–20710. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.360065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Génin E, Cooper DN, Masson E, Férec C, Chen JM. NGS mismapping confounds the clinical interpretation of the PRSS1 pAla16Val (c.47C>T) variant in chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 2022;71(4):841–2. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yilmaz B, Ekiz F, Karakas E, Aykut A, Simsek Z, Coban S, et al. A rare PRSS1 mutation in a Turkish family with hereditary chronic pancreatitis. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2012;23(6):826–827. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2012.0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nemoda Z, Sahin-Tóth M. The tetra-aspartate motif in the activation peptide of human cationic trypsinogen is essential for autoactivation control but not for enteropeptidase recognition. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(33):29645–29652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505661200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Joergensen MT, Geisz A, Brusgaard K, de Muckadell OBS, Hegyi P, Gerdes AM, et al. Intragenic duplication: a novel mutational mechanism in hereditary pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2011;40(4):540–546. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182152fdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gorry MC, Gabbaizedeh D, Furey W, Gates LK, Jr, Preston RA, Aston CE, et al. Mutations in the cationic trypsinogen gene are associated with recurrent acute and chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1997;113(4):1063–1068. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9322498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dytz MG, de Mendes MJ, de Castro Santos O, da Silva Santos ID, Rodacki M, Conceicao FL, et al. Hereditary pancreatitis associated with the N29T mutation of the PRSS1 gene in a Brazilian family: a case-control study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94(37):e1508. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Arduino C, Salacone P, Pasini B, Brusco A, Salmin P, Bacillo E, et al. Association of a new cationic trypsinogen gene mutation (V39A) with chronic pancreatitis in an Italian family. Gut. 2005;54(11):1663–1664. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.062992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Teich N, Bauer N, Mossner J, Keim V. Mutational screening of patients with nonalcoholic chronic pancreatitis: identification of further trypsinogen variants. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(2):341–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Németh BC, Patai ÁV, Sahin-Tóth M, Hegyi P. Misfolding cationic trypsinogen variant p.L104P causes hereditary pancreatitis. Gut. 2017;66(9):1727–8. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Balazs A, Hegyi P, Sahin-Tóth M. Pathogenic cellular role of the p.L104P human cationic trypsinogen variant in chronic pancreatitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2016;310(7):477–86. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00444.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pho-Iam T, Thongnoppakhun W, Yenchitsomanus PT, Limwongse C. A Thai family with hereditary pancreatitis and increased cancer risk due to a mutation in PRSS1 gene. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(11):1634–1638. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i11.1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kereszturi E, Szmola R, Kukor Z, Simon P, Weiss FU, Lerch MM, et al. Hereditary pancreatitis caused by mutation-induced misfolding of human cationic trypsinogen: a novel disease mechanism. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(4):575–582. doi: 10.1002/humu.20853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gui F, Zhang Y, Wan J, Zhan X, Yao Y, Li Y, et al. Trypsin activity governs increased susceptibility to pancreatitis in mice expressing human PRSS1R122H. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(1):189–202. doi: 10.1172/JCI130172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Huang H, Swidnicka-Siergiejko AK, Daniluk J, Gaiser S, Yao Y, Peng L, et al. Transgenic expression of PRSS1R122H sensitizes mice to pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(4):1072–82 e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Howes N, Greenhalf W, Rutherford S, O'Donnell M, Mountford R, Ellis I, et al. A new polymorphism for the RI22H mutation in hereditary pancreatitis. Gut. 2001;48(2):247–250. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.2.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Le Maréchal C, Chen JM, Le Gall C, Plessis G, Chipponi J, Chuzhanova NA, et al. Two novel severe mutations in the pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor gene (SPINK1) cause familial and/or hereditary pancreatitis. Hum Mutat. 2004;23(2):205. doi: 10.1002/humu.9212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kiraly O, Boulling A, Witt H, Le Marechal C, Chen JM, Rosendahl J, et al. Signal peptide variants that impair secretion of pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (SPINK1) cause autosomal dominant hereditary pancreatitis. Hum Mutat. 2007;28(5):469–476. doi: 10.1002/humu.20471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Masson E, Le Marechal C, Levy P, Chuzhanova N, Ruszniewski P, Cooper DN, et al. Co-inheritance of a novel deletion of the entire SPINK1 gene with a CFTR missense mutation (L997F) in a family with chronic pancreatitis. Mol Genet Metab. 2007;92(1–2):168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All supporting data are available within the article.