Abstract

In palliative care, as in many areas of medicine, there is a considerable amount of research conducted that makes sound recommendations but does not result consistently in improved care. For instance, though palliative care has been shown to benefit all people with a life-threatening illness, its main reach continues to be for those with cancer. Drawing on relational models of research use, we set out to engage policy-makers, educators, clinicians, commissioners and service providers in a knowledge exchange process to identify implications of research for Scottish palliative care priorities. First, we mapped the existing palliative care research evidence in Scotland. We then organised evidence review meetings and a wider stakeholder event where research producers and users came together to coproduce implications of the evidence for policy, education and practice. We used questionnaires and key stakeholder feedback meetings to explore impacts of this process on research uptake and use immediately after the events and over time. In this paper, we reflect on this knowledge exchange process and the broader context in which it was set. We found that participation fostered relationships and led to a rich and enthusiastic exploration of research evidence from multiple perspectives. Potential impacts relating to earlier identification for palliative care, education and need-based commissioning ensued. We make suggestions to guide replication.

Keywords: bereavement, nursing home care, education and training, communication, chronic conditions, cancer

Key messages.

What was already known?

Research findings often do not influence policy and practice.

Knowledge exchange initiatives can address this.

What are the new findings?

A four-step process facilitated a rich and enthusiastic exploration of research evidence from multiple perspectives.

Both researchers and key stakeholders gained new clinical, educational and policy insights.

What is their significance?

This approach informed stakeholder decision-making regarding palliative care policy and practice.

Research and relationships promote research use.

Introduction

Despite growing evidence that palliative care is relevant to all life-threatening diseases, should be integrated from diagnosis, should address all dimensions of need and should be delivered across all settings of care,1 2 research has failed to influence many related aspects of policy and clinical practice.3 Specific tools have been developed, validated and recommended to help clinicians to identify and assess patient needs and to share these plans across settings,4–6 but many people still do not benefit from palliative care.7 Unless health and social care research findings are shared, understood and used, their overall value is limited.

Recognising this, over the past two decades, there has been an increasing focus on understanding the processes by which findings from research are used to inform policy and practice.8 Knowledge mobilisation (KMb) is commonly adopted as an umbrella term to describe any activities aimed at collating and communicating research-based knowledge in health and social care systems.9 KMb emphasises a proactive process, whereby knowledge is shared for a specific purpose. It recognises that the dissemination of research via traditional academic channels alone is not sufficient. Instead, proactive strategies are required to bring together those who generate research (research producers) and those who can use research knowledge to inform real-world decision-making and change (research users). Research knowledge brokers—those whose role involves facilitating links between research producers and users — play an important role in this process.10 Brokers organise knowledge sharing activities, facilitate the development of collaborative relationships and support network building between research producers and users

In order to create shared understanding about research uptake and use, some definitions are needed. ‘Research uptake’ relates to user engagement with research and is supported by activities such as conferences, briefings and seminars where research producers and users come together to discuss research findings and how it might apply to their area.11 ‘Research use’ occurs when research users act on the research, adapt it to their context and use it to inform policy or practice developments.11 Three main types of research use are frequently identified: instrumental, conceptual and symbolic.12 13 Instrumental/direct use involves applying research findings to influence decision choices directly, for example, using a new evidence-based tool. Conceptual/indirect use involves using research findings to change understanding and/or attitudes and introduce new concepts, terms or theories, for example, using research findings to describe the scale of a problem or knowledge gaps. Symbolic/political/persuasive use is where research findings are used to develop a position, as well as to justify, legitimise and maintain a predetermined one, for example, where high-level research findings are used for the purposes of advocacy. Instrumental/direct use is linked with well-defined decision-making in relation to a specific problem; conceptual/indirect use may be longer term and gradual; symbolic use is often associated with gaining political traction. Often, all three forms occur in the same context or setting.12

Our work is underpinned by relational models of knowledge mobilisation. Interactional or relational models of knowledge flow assume that relationships and networks are the most important way in which research is shared, used and reused.11 These models suggest that learning is a social and situated process and emphasise the importance of interactions between people and ideas whether in research, policy or practice. Linkage and exchange approaches are a typical example14 and involve a greater degree of interaction between research producers and users than traditional linear approaches. The level of engagement varies, but can include anything from dialogue between research producers and users through to collaborative engagement in producing research evidence (coproduction) or in working together to implement evidence (eg, action research).

Identifying, engaging and building relationships with stakeholders and key stakeholders in research activity is critical. Stakeholders include a broad range of research users including clinicians, healthcare providers, policy-makers, politicians, regulators, academics, research funders, industry and insurers, alongside patients, carers and families. Key stakeholders are an important group of stakeholders who can act on the basis of the research knowledge or can directly influence those who can act.12 13 Given the greater decision-making influence of key stakeholders, identifying and engaging this group is vital in promoting research evidence use.

Aim and approach taken

Our primary aim was to engage key stakeholders in palliative care research in order to increase palliative care research uptake and use in Scotland. We sought to design and coordinate a knowledge exchange process so that palliative care research findings might be shared and discussed with stakeholders responsible for palliative care policy, service delivery, education and planning. We hypothesised that such a process would increase research uptake and use, inform evidence-based decision-making and drive palliative care quality improvement in the longer term. The focus of this paper is to describe the knowledge exchange process and impact on research uptake and use. This process was situated within the broader context of a newly published Scottish Government Strategic Framework for Action (SFA) on Palliative and End of Life Care (2016–2021).15

Policy context in Scotland: 2016–2021

The SFA set out the Scottish Government’s vision for palliative care that ‘…by 2021, everyone in Scotland who needs palliative care will have access to it’.15 The framework outlined 10 commitments to support a range of improvements. The fifth commitment advocated the strengthening and coordination of research and knowledge exchange through the establishment of a Scottish Research Forum for Palliative and End of Life Care.

The Scottish Research Forum for Palliative and End of Life Care

This open forum was established in May 2016 to bring together researchers, clinicians, service managers, policy-makers and health and social care professionals. It was co-chaired by a professor of primary palliative care (SAM) and a professor of nursing and palliative care (BJ) and supported by an organising committee. A key objective was to share research findings across academic, policy and health and social care communities, including, where possible, patient and public involvement (PPI) representation.

Description of knowledge exchange process

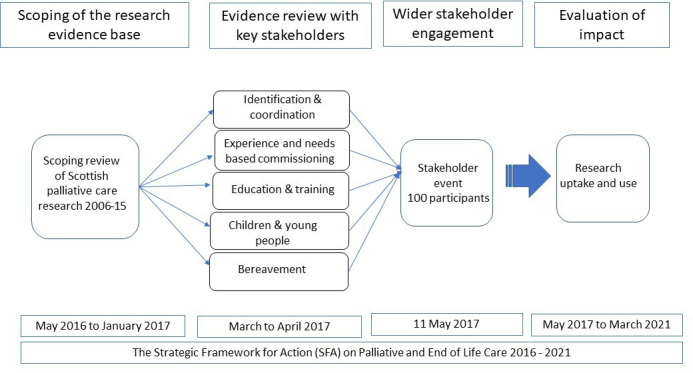

The knowledge exchange process evolved after a scoping review of Scottish palliative and end-of-life care research was completed.16 On reflection, the overall process comprised of four stages: (1) scoping review of the research evidence base, (2) evidence review with key stakeholders, (3) wider stakeholder engagement and (4) evaluation (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of the four-step knowledge exchange process.

Step 1: Scoping review of the research evidence base

A subgroup of forum members conducted a scoping review of all palliative care research in Scotland published during the previous decade.16 This process identified 308 papers, many of which related to priority areas highlighted in the SFA as areas where palliative care might need to be better integrated and practised.15

Step 2: Evidence review with key stakeholders

The papers identified in the scoping review were mapped to priority areas in the SFA. Five priority areas with a significant volume of mapped research were selected for further evidence review and knowledge exchange:

Identification and coordination (50 papers).

Experienced and needs-based service commissioning (70 papers).

Education and training (37 papers).

Children and young people (18 papers).

Bereavement (22 papers).

For each priority area, an evidence review group meeting was convened. Each group was facilitated by a key stakeholder (a research user in a senior position who could act on the research knowledge) to lead the discussion and a member of the scoping review research team to ensure continuity from step 1 of the process. A mix of health and social care professionals, service managers, educators and policy-makers were invited to participate in each group to encourage a range of perspectives on the priority area. These were identified by the research team in discussion with policy colleagues and through snowballing (whereby those invited suggested others with relevant expertise). Six-to-eight participants attended each meeting (with some of the research team attending more than one meeting). Each meeting lasted 1–2 hours and half of the participants were research producers (research team members) and half were research users (clinicians, educators, service managers and those in a policy-related role). In advance of each evidence review meeting, the coordinator provided group members with a summary of findings from the published papers identified during the scoping review relating to their topic and any additional literature that members requested (eg, full-text versions of key papers). At each meeting, the discussion was structured around the following four areas relevant to the priority area being considered: (1) key findings from research relevant to their priority area; (2) evidence-based examples of good practice; (3) key implications for policy, training and service delivery and (4) evidence gaps. Following the meeting, the key stakeholder facilitator synthesised the discussion and research implications for presentation at the follow-up stakeholder engagement event.

Step 3: Wider stakeholder engagement

Through the Scottish Research Forum for Palliative and End of Life Care, we organised a wider stakeholder engagement event attended by 100 key policy-makers, educators, clinicians, social care workers, academics and commissioners in palliative care across Scotland. This half-day event took place on 11 May 2017 and was opened by the Scottish Government’s Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport. The programme consisted of an overview of findings from the scoping review,16 five short presentations each focusing on one of the priority areas selected for evidence review and a question and answer session. The presentations were delivered by the key stakeholder facilitators identified in step 2. The question and answer session encouraged wider stakeholder participation and critical reflection on the implications of research findings in practice.

Step 4: Evaluation

Assessing impact on research uptake and use

Evaluating the specific impact of knowledge exchange activities is challenging.12 17 To assess the immediate impacts of the evidence review process and stakeholder event, we invited participants to provide feedback by questionnaire (online for the evidence review meetings and paper-based immediately after the wider stakeholder event). Questionnaires were designed by the research team, specifically for the purpose of gathering feedback (see online supplemental material). Quantitative data were analysed descriptively in MS Excel. Qualitative data were analysed using a content analysis approach, which allows quantification of common issues that appear in the data and is suited to pragmatic analyses involving low levels of interpretation.18 To identify potential longer-term impacts, we held two group meetings by teleconference involving the research team and key stakeholders. The first was held within a year of the original events and the second in 2021, coinciding with the end period covered by the SFA on Palliative and End of Life Care.15 Feedback from these two meetings, alongside follow-up feedback shared by key stakeholders via email, was summarised by the coordinator, but not formally analysed.

bmjspcare-2021-003096supp001.pdf (38.9KB, pdf)

Research uptake

In total, 23 key stakeholders and researchers participated in the evidence review groups (some participated in more than one). An anonymised online questionnaire was circulated within a month of the review groups to collect feedback from participants. All respondents (n=15) described the evidence review meetings as ‘useful’ and ‘relevant’.

"In the review meetings it was helpful to speak to people with similar research, practice and policy interests and critique the current research base."

Participants valued the professional diversity of group members as this enabled each priority area to be explored from a breadth of perspectives:

"I found it fascinating to listen to and learn from colleagues from such a range of backgrounds and to consider how the same evidence can be interpreted and utilised differently, depending on the perspective."

Participants also reflected on how the group discussions had shaped and informed their own practice within the priority area under consideration. For instance, in an email to the project leads (AF and SAM), a key stakeholder involved in the education and training evidence review group wrote:

"…[the evidence review process] shaped our approach to implementing the national educational framework by highlighting end-of-life care as an area of unmet need for a wide range of staff groups, meaning this could be raised in discussion with regional and local groups tasked with leading workforce development…[It] strengthened our understanding of the need to engage with care home and care-at-home sectors by highlighting these as under-represented in current research, and supported the case for ensuring educational resources are relevant, accessible and promoted to staff in these sectors. [It] reinforced our intention to address the emotional impact of palliative care provision in the national educational resource by highlighting this as an area of interest and concern for staff in clinical practice."

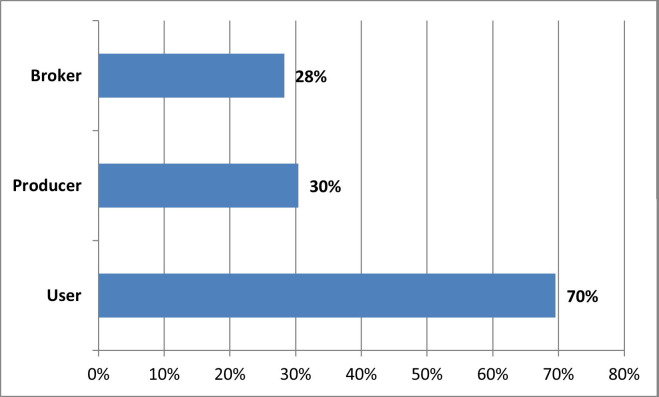

The wider stakeholder event was oversubscribed, reflecting a high interest in the application of research to policy, training and service delivery. Overall, 46 of the 100 attendees completed a post event paper-based questionnaire. The response rate (46%) was lower than expected as feedback forms were left to the end of the event and not seen by all participants. Over two-thirds of respondents were research users (figure 2). All respondents described the event as ‘very useful’ (78%) or ‘quite useful’ (22%). In response to a question exploring what respondents liked about the event, 52% noted the variety, diversity and breadth of content and the fact that many of the presentations were given by research users who were able to articulate the implication of research findings in their own work setting:

Figure 2.

Role of the participants at the knowledge exchange event (N=46) Note: Participants could choose more than one role.

"Range of speakers presenting, not just research academics."

"Varied, short and sharp, I learned a lot."

"Informative relevant progressive discussion."

In response to the question, ‘Is there anything you will do in your place of work because of the event?’, 30% stated they would promote or use research findings in their workplace and a further 26% said they would disseminate findings to colleagues or use them for educational purposes. Respondents commented:

"[I will] invite palliative care researchers to speak at network/specialty groups."

"Share learning with colleagues."

"Ensure we have a research fellow as part of our workforce in the near future."

"Thinking about attracting more research brokers."

"[I will] follow-up on some of the academic research and resources."

Some respondents (15%) also commented that they were interested in accessing specific tools to identify patients, for example,

"[I will] look into the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool."

Similar future events were viewed as useful to support evidence-based decision-making in palliative care, especially given the opportunities to collaborate with others in different areas concerned with similar priorities. Many recommended further networking events to support evidence-based decision-making in the future. One respondent reported:

"I would like to see each NHS board have a research platform where a variety of professional groups are invited along to help be part of research, inform research, and help knowledge exchange."

Research Use

The knowledge exchange process led to instrumental, conceptual and symbolic research use. Specific examples relating to each priority area were evident (table 1).

Table 1.

Specific examples of research use over time

| Priority area | Examples of research use |

| Identification and coordination |

|

| Experienced and needs based service commissioning |

|

| Education and training |

|

| Children and young people |

|

| Bereavement |

|

Instrumental/direct research use

Research evidence was used to embed palliative care teaching resources in undergraduate programmes of education and to create resources, including videos, for clinicians and patients.19 Evidence based tools were incorporated into new training materials by Healthcare Improvement Scotland to improve identification of people for early palliative care.20 The recognition of the lack of research around bereavement services and support needs led a group of researchers and service managers to develop a network to discuss their interests in bereavement research and plan an application for funding.

Conceptual/indirect research use

Conceptual use of research was evidenced by the strengthening of awareness and understanding of palliative care in non-specialist professional networks. This included a greater awareness of tools such as the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT) for improving identification of people for a palliative care approach. Conceptual research use was also evident in the development of Scottish Government Commissioning Guidance for Palliative and End of Life Care which drew heavily on the research discussed as part of the process.21 Research on the number of people with a Key Information Summary (KIS), a shared electronic care record,22 was used to inform the Scottish General Medical Services Direct Enhanced Services Palliative Care Scheme (2019), which rewarded General Practitioner Practices to systematically identify appropriate patients for palliative care and create a KIS.

Symbolic/persuasive/political research use

Research was used by key stakeholders to describe how far Scotland had come in terms of coordinating care for people with palliative care needs and what was needed to improve further. The process helped raise the profile of the importance of the KIS to better coordinate care of people with palliative care needs. Evidence on the importance of identifying people with any advanced progressive condition for financial support earlier, and regardless of diagnosis, was used by Marie Curie and MND Scotland to support their successful advocacy work for a new definition of terminal illness to be included in the Social Security (Scotland) Act 2018.

Relationships

There was general agreement that the knowledge exchange process increased comradery, communication, fostered new relationships and enabled shared understanding among the academics, policy-makers, service managers and health and social care professionals involved. The process entailed the active use of research by key stakeholders—in the review of articles, in the discussion groups, in the presentation of insights to the audience attending the wider stakeholder event and in the audience questions that followed. This participatory process enabled the construction and use of new knowledge as key stakeholders encountered and explored the research findings and worked to translate and apply the ideas and insights in their respective areas and fields of expertise. Having had the opportunity to engage with the research evidence, key stakeholders felt more confident and empowered to advocate clearly and with authority in their bases and to suggest changes, improvements and innovations. Learning was mutual, with researchers gaining new insights into the competing priorities and context experienced by research users and the need for greater consideration of strength of evidence when recommending changes in policy and practice. The professional diversity facilitated a rich and nuanced exploration of the research findings and their application to early identification for palliative care in general settings, care coordination, commissioning, education, children and young people and bereavement.

Reporting and wider dissemination

A summary report which emerged from the process was shared among all attendees.23 This was also shared with key health and social care decision-makers who were not involved, including all members of the Scottish Government’s National Implementation and Advisory Group (NIAG), the group overseeing progress on the SFA on Palliative and End of Life Care. The process and report were discussed at the NIAG and covered in the mainstream media, reflecting wider diffusion of findings.24

Facilitating factors, barriers and other considerations

In Scotland, there was already a strong government-level commitment to the improvement of palliative and end-of-life care leading up to the SFA and the prevailing social and political climate was one in which research evidence was valued. This type of culture helps foster and promote knowledge exchange initiatives such as that described here.12 Specific facilitating factors included pre-existing relationships between research producers and users, relevance of research to current policy priorities, financial and in-kind contributions, identification of a coordinator and emphasis on mutual learning. We were able to draw on pre-existing relationships between the research team and colleagues in diverse roles and organisations to identify key stakeholders to participate in the evidence review meetings. The Scottish Government contributed to the costs involved in conducting the scoping review, while Marie Curie covered the costs of the wider stakeholder event (meeting room hire, catering, equipment, administration). A member of the research team coordinated the overall process. Throughout the process, there was a strong focus on mutual learning and support—with research producers developing a much better understanding of real-world decision-making, the contexts in which resources are allocated, strategies are developed and the type of evidence needed to inform this.

Barriers to evaluating and sustaining the process were also evident. Overall, we received feedback from 61 participants—15 of those involved in the evidence review groups and 46 of those participating in the stakeholder engagement event. It is possible that those who responded were those most engaged and positive about knowledge exchange activities. Future evaluation work should try to identify strategies to optimise feedback from all participants, such as building this in as part of attending the event and emphasising the importance of feedback to guide future collaborative work. In terms of sustainability, the Scottish Palliative and End of Life Care Research Forum was particularly active between 2016 and 2018 but, due to a lack of financial resources to help with forum administration and event organisation, event activity was subsequently reduced. This type of network is hugely helpful for knowledge exchange initiatives but needs to be resourced to ensure sustainability over time.

Our four-step knowledge exchange process describes a set of methodological steps that could be used to promote research knowledge exchange in other regions and countries. The process should be underpinned by regional and/or national palliative and end-of-life care priorities, which will differ across countries. We would expect that the discussions, perspectives and politics of the stakeholders involved would also differ between countries, as these are influenced by the culture, societal norms and values, as well as the context in which care is delivered. Timing is also relevant. For instance, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a considerable research and policy focus on bereavement support, psychological support, advance care planning and digital health interventions than previously was the case and such topics are likely to emerge more prominently if this process were to be replicated now. In the longer term, as perspectives on palliative care evolve (eg, if a move to more disease-specific and location-specific care models continues), this will in turn influence research and policy priorities, as well as perceived evidence gaps. Re-running this process at relevant time points, such as when new policies are being developed or implemented or research questions need to be reprioritised, is recommended. As palliative care becomes more integrated with other services within the health and social care system, there will be an even greater need for knowledge exchange involving diverse professional communities, patients and carers, so that the holistic care of the person and their family remains the primary consideration.

The four-step knowledge exchange process we outline is also well suited for use where the focus is a specific topic to inform service and policy developments in that area (eg, out of hours care; informal carer support; inequalities in access to palliative care). In this case, the process would involve a greater focus on all aspects of the topic under consideration, potentially leading to more focused impacts and an emerging collaborative network with a common interest that could be sustained over time.

Replicating this knowledge exchange process

We offer the following 10 steps to guide others interesting in adapting this process to promote knowledge exchange in their countries, regions or health and social care area.

Convene an organising committee, including a coordinator and administrative support.

Scope the research evidence base, with a particular focus on the evidence generated in your region. This could be carried out formally using systematic scoping review or rapid review methods or informally, depending on the resources available. You might include evidence beyond your region if you are focusing on a narrower topic where geography, context or setting is less important.

Identify strategic priorities. Draw on local or regional policy and strategy documents relevant to palliative and end-of-life care, to identify priorities for change and improvement.

Engage key stakeholders with a particular interest or expertise in each priority area—a mix of research users from health and social care settings, as well as those involved in policy, advocacy, commissioning and service innovation. PPI is key and professionals from generalist settings should ideally be involved.

Map the evidence relevant to each priority area. Collate and summarise key findings of research relevant to each priority area.

Create evidence review groups to appraise the research, facilitate critical reflection and draw implications for policy, education, commissioning and practice. Identify a research producer (academic) and research user (key stakeholder) to facilitate each group. Include a PPI representative. Work together to summarise the evidence and coproduce implications for practice in a format that can be presented to a wider stakeholder group.

Organise and advertise a wider stakeholder event with a recognised leader or decision-maker to open the event, where a key stakeholder from each evidence review group presents research and its implications (identified in the evidence review groups) to a wider audience, who in turn reflect on the presentations and share their experiences and perspectives on the implications.

Share the event findings and key points raised with those who attended the events, including a summary report, which can be disseminated easily and discussed at future key meetings.

Evaluate the process using formal (eg, questionnaire) and informal approaches (eg, feedback meetings; social media) to explore impacts on all forms of research use.

Sustain relationships over time.

Conclusion

A relational approach to knowledge mobilisation fostered a vibrant dialogue between researcher producers and users, enabling appraisal of the latest research evidence and generation of implications for palliative care policy and practice in Scotland. Relevant research was identified by key stakeholders who were able to use it in their respective professional settings. The process increased stakeholder confidence around research use, promoted stakeholder ownership of the research and fostered relationships between research users and producers which were sustained over time. Our process was underpinned by collaborative engagement with stakeholders, reciprocity, shared accountability for implications generated and respect for the knowledge of all parties involved. Overall, the four-step knowledge exchange process contributed to research use in palliative care education, service commissioning and care coordination. This approach to knowledge exchange may be relevant to other areas of health and social care—especially areas that are complex and with many stakeholder groups across professions and settings—and in low-income, middle-income and high-income countries.

Footnotes

Twitter: @A_Finucane, @carer_research

Contributors: AF, EC, SF, JL, BJ and SAM were involved in the scoping review. AF, EC, RM and SAM conceived of, and organised the evidence review meetings and wider stakeholder event. SD, SF, SC, DH and FR participated in the evidence review meetings as key stakeholders. AF, EC, SF, BJ and SAM facilitated evidence review meetings. BJ chaired the wider stakeholder event. AF and JL designed feedback questionnaires and analysed the data. AF drafted the manuscript. All authors provided critical content and agreed the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by a small grant from the Scottish Government for the scoping review (£5893). Marie Curie funded the knowledge exchange event through its Policy and Public Affairs, Scotland Team (£750). Anne Finucane is funded by a Marie Curie Research Fellowship: www.mariecurie.org.uk

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1. Murray SA, Kendall M, Mitchell G, et al. Palliative care from diagnosis to death. BMJ 2017;356:j878. 10.1136/bmj.j878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, et al. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 2005;330:1007–11. 10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Murray SA, Murray IR. End of life care still not living up to public and doctors' expectations. BMJ 2016;353:i2188. 10.1136/bmj.i2188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Highet G, Crawford D, Murray SA, et al. Development and evaluation of the supportive and palliative care indicators tool (SPICT): a mixed-methods study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2014;4:285–90. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Finucane AM, Davydaitis D, Horseman Z, et al. Electronic care coordination systems for people with advanced progressive illness: a mixed-methods evaluation in Scottish primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2020;70:e20–8. 10.3399/bjgp19X707117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Leniz J, Weil A, Higginson IJ, et al. Electronic palliative care coordination systems (EPaCCS): a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2020;10:68–78. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dixon J, King D, Matosevic T. Equity in the provision of palliative care in the UK: review of evidence. London School of Economics and Political Science, Personal Social Services Research Unit, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Farley-Ripple EN, Oliver K, Boaz A. Mapping the community: use of research evidence in policy and practice. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 2020;7:1–10. 10.1057/s41599-020-00571-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davies H, Powell A, Nutley S. Mobilizing knowledge in health care. Oxford University Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pentland D, Forsyth K, Maciver D, et al. Key characteristics of knowledge transfer and exchange in healthcare: integrative literature review. J Adv Nurs 2011;67:1408–25. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05631.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morton S. Progressing research impact assessment: A ‘contributions’ approach. Res Eval 2015;24:405–19. 10.1093/reseval/rvv016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davies HTO, Powell AE, Nutley SM. Mobilising knowledge to improve UK health care: learning from other countries and other sectors – a multimethod mapping study. Health Serv Deliv Res 2015;3:1–190. 10.3310/hsdr03270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lavis JN, Robertson D, Woodside JM, et al. How can research organizations more effectively transfer research knowledge to decision makers? Milbank Q 2003;81:221–48. 10.1111/1468-0009.t01-1-00052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lomas J. Essay: Using 'linkage and exchange' to move research into policy at A Canadian Foundation. Health Aff 2000;19:236–40. 10.1377/hlthaff.19.3.236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scottish Government . Palliative and end of life care: strategic framework for action, 2015. Available: https://www.gov.scot/publications/strategic-framework-action-palliative-end-life-care/ [Accessed 19 Jun 2021].

- 16. Finucane AM, Carduff E, Lugton J, et al. Palliative and end-of-life care research in Scotland 2006-2015: a systematic scoping review. BMC Palliat Care 2018;17:19. 10.1186/s12904-017-0266-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morton S. Creating research impact: the roles of research users in interactive research mobilisation. Evid Policy 2015;11:35–55. 10.1332/174426514X13976529631798 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci 2013;15:398–405. 10.1111/nhs.12048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Primary Palliative Care Research Group . Early palliative care: a video for health and care professionals. Available: https://www.ed.ac.uk/usher/primary-palliative-care/videos/health-and-care-professionals [Accessed 09 Mar 2021].

- 20. Healthcare Improvement Scotland . Comparing tools that can help to identify people who could benefit from a palliative care approach, 2018. Available: https://livingwellincommunities.com/2018/04/11/comparing-tools-that-can-help-to-identify-people-who-could-benefit-from-a-palliative-care-approach/ [Accessed 15 Jul 2021].

- 21. Scottish Government . Strategic Commissioning of Palliative and End-of-Life Care by Integration Authorities. Edinburgh, 2018. https://www.gov.scot/publications/strategic-commissioning-palliative-end-life-care-integration-authorities/ [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tapsfield J, Hall C, Lunan C, et al. Many people in Scotland now benefit from anticipatory care before they die: an after death analysis and interviews with general practitioners. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2019;9:e28. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-001014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marie Curie Scotland . Palliative care in Scotland: research into practice, 2017. Available: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/minutes/2018/11/palliative-and-end-of-life-care-national-implementation-advisory-group-papers-december-2017/documents/palliative-care-in-scotland-research-into-practice/palliative-care-in-scotland-research-into-practice/govscot%3Adocument/Palliative%2Bcare%2Bin%2BScotland%2B-%2Bresearch%2Binto%2Bpractice.pdf [Accessed 09 August 2021].

- 24. Meade R. Research must be shared to promote debate and shape policy. The Scotsman 2017. https://www.scotsman.com/news/richard-meade-research-must-be-shared-promote-debate-and-shape-policy-1448522 [Google Scholar]

- 25. NHS Education for Scotland . Palliative and end of life care: a framework to support the learning and development needs of the health and social service workforce in Scotland 2018. https://lms.learn.sssc.uk.com/course/view.php?id=2

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjspcare-2021-003096supp001.pdf (38.9KB, pdf)