ABSTRACT

Enterovirus D68 (EV-D68) can cause mild to severe respiratory illness and is associated with a poliomyelitis-like paralytic syndrome called acute flaccid myelitis (AFM). Most cases of EV-D68-associated AFM occur in young children who are brought to the clinic after the onset of neurologic symptoms. There are currently no known antiviral therapies for AFM, and it is unknown whether antiviral treatments will be effective if initiated after the onset of neurologic symptoms (when patients are likely to present for medical care). We developed a “clinical treatment model” for AFM, in which individual EV-D68-infected mice are tracked and treated with an EV-D68-specific human-mouse chimeric monoclonal antibody after the onset of moderate paralysis. Mice treated with antibody had significantly better paralysis outcomes compared to nonspecific antibody-treated controls. Treatment did not reverse paralysis that was present at the time of treatment initiation but did slow the further loss of function, including progression of weakness to other limbs, as well as reducing viral titer in the muscle and spinal cords of treated animals. We observed the greatest therapeutic effect in EV-D68 isolates which were neutralized by low concentrations of antibody, and diminishing therapeutic effect in EV-D68 isolates which required higher doses of antibody for neutralization. This work supports the use of virus-specific immunotherapy for the treatment of AFM. It also suggests that patients who present with AFM should be treated as soon as possible if recent infection with EV-D68 is suspected.

KEYWORDS: enterovirus D68, chimeric monoclonal antibody, delayed treatment, acute flaccid myelitis, EV-D68, enterovirus

INTRODUCTION

Enterovirus D68 (EV-D68) is an emerging pathogen, which caused worldwide outbreaks of respiratory disease in children during the fall of 2014, 2016, and 2018. The prodromal illness typically includes cough, congestion, and sore throat, with some patients reporting nausea and vomiting (1). However, while the respiratory illness can be severe and can result in hospitalization, the most serious consequence of EV-D68 infection is its association with a rapid onset poliomyelitis-like paralytic disease. This paralytic disease, called acute flaccid myelitis (AFM), is characterized by a rapid onset of muscle weakness, which can progress to paralysis in one or more limbs. Weakness typically begins approximately 5 to 7 days after the prodromal respiratory symptoms. Patients may report some improvement in their preceding respiratory and systemic symptoms before the onset of neurological deficits (2). The pattern of muscle weakness and associated clinical and laboratory studies are consistent with virus-induced death of motor neurons. Unfortunately, most patients who develop AFM will have residual long-term motor deficits with the most profoundly affected muscle groups showing little to no improvement in strength (2).

There are currently no proven effective antiviral therapies for treatment of AFM, nor is there a vaccine (3). Studies in experimental murine models of AFM have shown that human intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and anti-EV-D68 neutralizing monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies can significantly reduce paralysis and improve survival when administered prior to the onset of paralysis (4–6). It remains unclear, even in experimental models, if therapy will be effective after the onset of neurological disease, and if so, what the therapeutic window is. No markers of risk for neurological disease progression among those with EV-D68 infection are currently known. Given the nonspecific nature of the prodromal respiratory symptoms caused by EV-D68, our current inability to identify which cases will progress to AFM, and the fact that most patients will not seek medical attention until the onset of AFM, prevention of EV-D68-associated AFM would require screening and treatment on a massive scale or broad administration of an effective vaccine, and neither of these approaches are currently feasible. Conversely, if treatment of EV-D68 could significantly reduce the severity of neurologic outcome even if the treatment regimen is initiated after the onset of AFM symptoms, then patients could be treated as soon as they seek medical attention with neurologic symptoms.

The objective of this study was to determine whether anti-EV-D68 neutralizing antibodies can significantly reduce the severity of paralysis outcomes when treatment is initiated after the onset of moderate paralysis in a mouse model. We call this model the “clinical treatment” model since most AFM patients do not present at the clinic for treatment until after the onset of neurologic symptoms. We utilized a monoclonal antibody, which we refer to as 15C5-Chmra. This antibody is a mouse-human chimera containing a human Fc domain and an Fab portion identical to that of a previously characterized mouse monoclonal antibody designated 15C5 (6). Mice treated with this antibody had significantly better paralysis outcomes compared to those of nonspecific antibody-treated controls when infected with EV-D68 isolates from patients during both the 2014 and 2016 outbreaks.

RESULTS

Efficacy of 15C5-Chmra antibody in a 24-h delayed-treatment model.

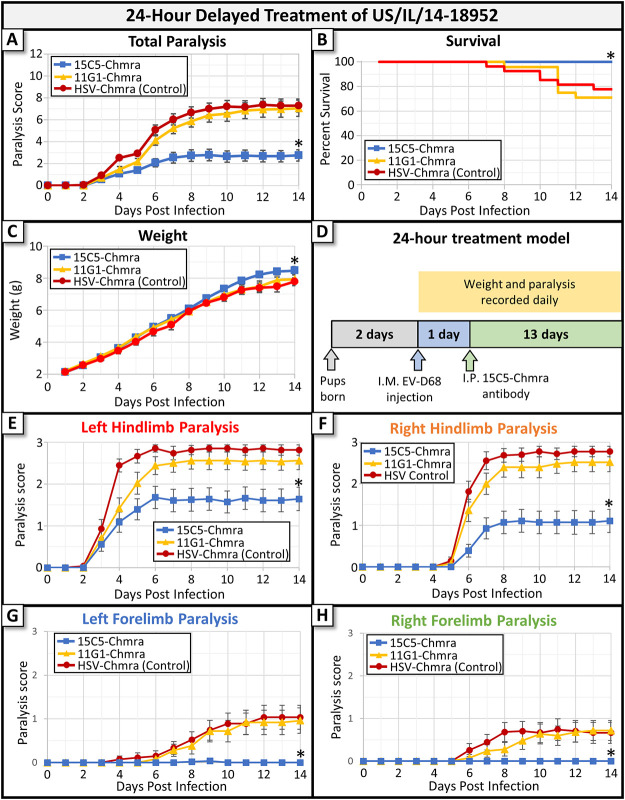

Two humanized monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) were tested in a 24-h delayed-treatment mouse model to assess efficacy against EV-D68-induced AFM. Zheng et al. (6) previously described each of these antibodies as follows: 15C5 which binds at the 3-fold axis of the viral capsid and 11G1 which binds at the 5-fold axis. We used chimeric antibodies (developed at ZabBio), which have an Fab fragment that matches that published by Zheng et al. but have a human rather than murine Fc fragment (to facilitate potential future use in humans). In this paper, we will refer to these chimeric antibodies as 15C5-Chmra and 11G1-Chmra. A chimeric anti-herpes simplex virus (anti-HSV) monoclonal antibody was used as a non-EV-D68-specific control, and animals treated with this antibody did not differ in any measured metric from animals treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) alone. Animals injected with anti-HSV had the same survival, weight gain, and paralysis scores as animals injected with PBS (no antibody control). Two-day-old Swiss Webster mice were infected with 10,000 × 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) of EV-D68 (isolate US/IL/14-18952) by intramuscular (i.m.) injection into the left hindlimb, and individual limbs were assessed for the development of paralysis using a previously validated scoring system (4). The 15C5-Chmra antibody significantly reduced the severity of paralysis outcome, increased animal survival, and increased weight gain (Fig. 1A to C, respectively) compared to outcomes for animals treated with control antibody. To assess whether this effect was due to neutralization by the Fab fragment or whether the presence of the foreign human Fc fragment alerted the mouse immune system to clear virus, we also assessed the efficacy of the 11G1-Chmra antibody. This antibody binds to viral capsid and has the same human Fc fragment as 15C5-Chmra (6), but in our model, it did not reduce paralysis outcome compared to that of nonspecific antibody-treated mice, did not increase animal survival, nor did it improve weight gain (Fig. 1A to C, respectively) compared to that of the controls. Our finding that the 11G1 antibody does not increase survival compared to that in controls when given 24 h postinfection differs from the results presented by Zheng et al. (6). However, since we used a different EV-D68 isolate (US/IL/14-18952 versus STL-2014-12), a different mouse strain (Swiss Webster versus BALB/cJ), and a different route of infection (i.m. versus intraperitoneally [i.p.]), it is not unexpected for our results to differ somewhat from those of Zheng et al. (6). A diagrammatic representation of our 24-h treatment model is shown in Fig. 1D. Taken together, these results confirm that 15C5-Chmra efficacy in vivo is due to binding of the Fab fragment to viral capsid and not a nonspecific result of recognition of the human Fc fragment by the murine immune system.

FIG 1.

Monoclonal antibody treatment of mice infected with EV-D68 beginning 24 h after infection. Two-day-old Swiss Webster mice were infected with EV-D68 (2014 isolate US/IL/14-18952). At 24 h following infection, mice were treated with 15C5-Chmra (n = 28), 11G1-Chmra (n = 24), or control antibody (n = 27). (A) Total paralysis score (0 = unparalyzed; 12 = quadriplegic) over a 14-day time course of experiment. 11G1-Chmra versus control was not significant, and 15C5-Chmra versus control was significant; *, P < 0.0001, repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) on days 12 to 14. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM). (B) Percent survival by treatment group for the same mice as in panel A. 11G1-Chmra versus control was not significant, and survival analysis of control versus 15C5-Chmra was significant; log-rank test, *, P = 0.0087. (C) The average pup weight by treatment group for the same mice as in panels A and B. 11G1-Chmra versus control was not significant, and 15C5-Chmra versus control was significant; *, P = 0.0362, repeated measures ANOVA on days 12 to 14. Error bars represent SEM. (D) A pictographic representation of the 24-h delayed treatment model. (E) The average paralysis in the left hindlimb (i.m. infected limb) for each group. Error bars represent SEM. There is a significant difference between 15C5-Chmra and control; *, P < 0.0001, repeated measures ANOVA. (F) The average paralysis in the right hindlimb for each group. Error bars represent SEM. There is a significant difference between 15C5-Chmra and control; *, P < 0.0001, repeated measures ANOVA. (G) The average paralysis in the left forelimb for each group. Error bars represent SEM. There is a significant difference between 15C5-Chmra and control; *, P = 0.0003, repeated measures ANOVA. (H) The average paralysis in the right forelimb for each group. Error bars represent SEM. There is a significant difference between 15C5-Chmra and control; *, P = 0.0018, repeated measures ANOVA.

We also examined how antibody treatment affects viral spread through the spinal cord by assessing the development of paralysis in individual limbs. The left hindlimb, which is intramuscularly infected with virus, was reliably the first limb to develop paralysis. A few days later, the contralateral (right) hindlimb began to show signs of paralysis, followed lastly by the development of paralysis in the forelimbs of some infected control-treated animals (data not shown). Treatment with 15C5-Chmra MAb at 24 h postinfection did not affect the time-to-paralysis for either the left or right hindlimbs (Fig. 1E and F). It did, however, reduce paralysis scores in both hindlimbs compared to nonspecific antibody-treated controls, as well as preventing the development of paralysis in the forelimbs (Fig. 1G and H), suggesting that its effects occur both outside the central nervous system (CNS) at the site of primary replication in muscle and within the spinal cord to inhibit viral spread and progression of paralysis.

Efficacy of 15C5-Chmra in clinical treatment model against EV-D68 isolate US/IL/14-18952.

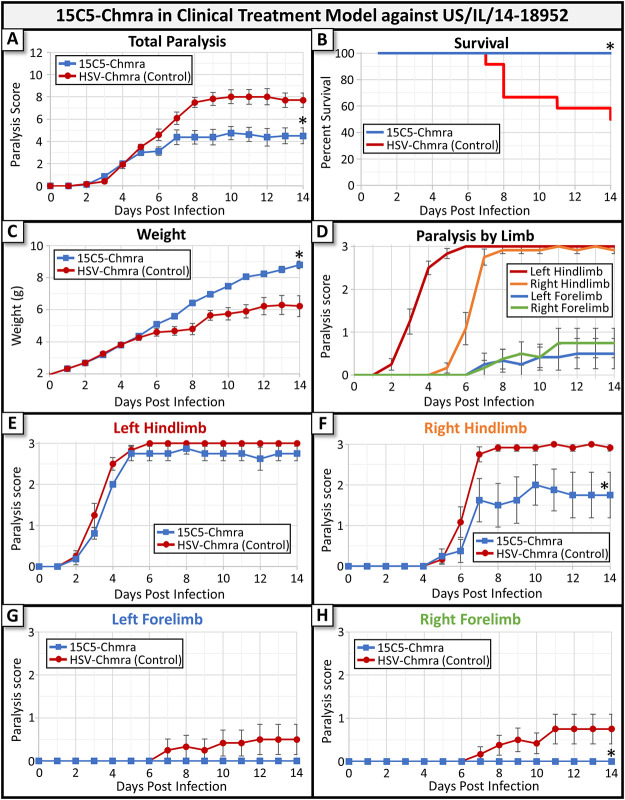

Having established the efficacy of 15C5-Chmra MAb in our 24-h delayed model, we next assessed whether this MAb was able to improve any of these metrics when treatment was withheld until after the onset of moderate paralysis (clinical treatment model). Mice were infected with a 2014 isolate of EV-D68 (US/IL/14-18952). When an individual animal was observed to have a paralysis score between 2 and 3 (moderate to complete paralysis in a single limb), then it was treated with either 15C5-Chmra or control antibody. Most mice became paralyzed and received treatment between 3 and 5 days after infection and had a paralysis score between 2 and 3 at the time of treatment. A detailed description of the animal numbers in each group, average paralysis score at the time of treatment, and metrics for degree of paralysis by group can be found in Table 1. In this clinical treatment model, we found that 15C5-Chmra MAb significantly reduced the severity of paralysis outcome, significantly increased animal survival, and significantly increased weight gain compared to that of the nonspecific MAb-treated controls (Fig. 2A to C, respectively). In this experiment, we once again observed that the (i.m. infected) left hindlimb developed paralysis a few days prior to the contralateral (right) hindlimb, and the forelimbs developed paralysis last (Fig. 2D). In the clinical treatment model, 15C5-Chmra did not significantly reduce paralysis in the left hindlimb (Fig. 2E), but this is not surprising since treatment was initiated when a paralysis score of 2 to 3 was already present in this limb. 15C5-Chmra treatment did, however, reduce the severity of paralysis in the right hindlimb and prevented the development of paralysis in the forelimbs—just as we saw in the 24-h delayed treatment model (Fig. 2F to H).

TABLE 1.

Experimental design summary

| Treatment | Viral isolate | Model | Days of treatment | Paralysis score at time of treatment | Δ Paralysis score after treatment | No. of mice in group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15C5-Chmra | US/IL/14-18952 | 24-h delayed | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 | +2.8 | 27 |

| 11G1-Chmra | US/IL/14-18952 | 24-h delayed | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 | +7.0 | 25 |

| Anti-HSV control | US/IL/14-18952 | 24-h delayed | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 | +7.3 | 28 |

| 15C5-Chmra | US/IL/14-18952 | Clinical | 4.0 ± 0.0 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | +2.50 | 8 |

| Anti-HSV control | US/IL/14-18952 | Clinical | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | +4.95 | 12 |

| 15C5-Chmra | 2016-334-74 | Clinical | 4.2 ± 1.0 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | +3.02 | 26 |

| Anti-HSV control | 2016-334-74 | Clinical | 4.3 ± 1.1 | 2.4 ± 1.0 | +5.00 | 28 |

FIG 2.

Monoclonal antibody treatment of mice infected with EV-D68 (2014 isolate US/IL/14-18952) in a clinical treatment model. In this model, mice were treated with either with 15C5-Chmra (n = 8) or control (n = 12) antibody after paralysis score reached or exceeded two (treatment was initiated between 3 and 5 days postinfection). (A) Total paralysis score (0 = unparalyzed; 12 = quadriplegic) over 14-day time course of experiment. 15C5-Chmra had significantly lower paralysis scores than control group (*, P = 0.0041, repeated measures ANOVA on day 6 to 14 time points). Error bars represent SEM. (B) Percent survival by treatment group for the same mice as in panel A. There was significantly improved survival in the 15C5-Chmra group compared to that in controls (log rank test, *, P = 0.0221). (C) The average pup weight by treatment group for the same mice as in panels A and B. There were significantly increased weights in the 15C5-Chmra group versus controls (*, P = 0.0004, repeated measures ANOVA on days 12 to 14). Error bars represent SEM. (D) Shows the average paralysis score for each limb across 14 days for the control group. Error bars represent SEM. (E) The average paralysis in the left hindlimb (i.m. infected limb) for each group. Error bars represent SEM. 15C5-Chmra versus control; P = 0.075, repeated measures ANOVA for days 9 to 14. (F) Shows the average paralysis in the right hindlimb for each group. Error bars represent SEM. 15C5-Chmra versus control; *, P = 0.0077 repeated measures ANOVA for days 6 to 14. (G) Shows the average paralysis in the left forelimb for each group. Error bars represent SEM. 15C5-Chmra versus control; P = 0.2640, repeated measures ANOVA for days 7 to 14. (H) The average paralysis in the right forelimb for each group. Error bars represent SEM. 15C5-Chmra versus control; *, P = 0.0361, repeated measures ANOVA for days 7 to 14.

Tissue titers in clinical treatment model against 2014 EV-D68 isolate US/IL/14-18952.

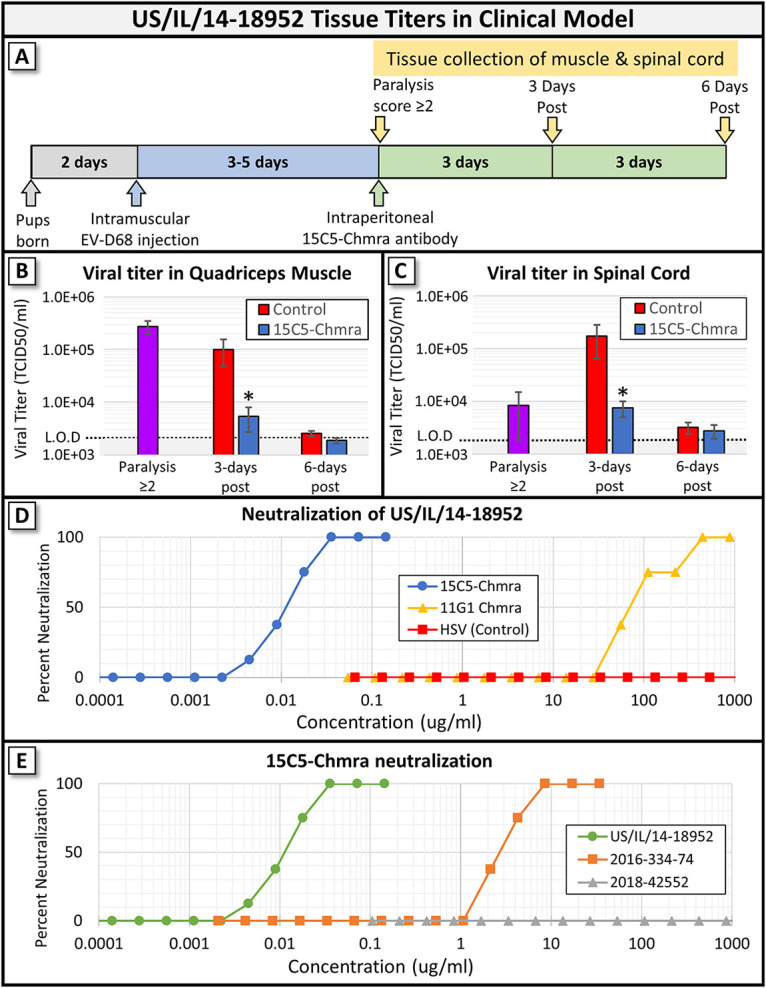

We next tested whether 15C5-Chmra reduced viral titer in spinal cord and muscle collected from mice in our clinical treatment model. Mice were infected with EV-D68 as described above. Tissue was collected from untreated mice when they reached a paralysis score greater than or equal to two. Alternatively, tissue was collected from additional mice at 3 and 6 days after treatment with antibody. Figure 3A is a pictographic representation of the clinical model and tissue collection time points. We found that the viral titer in both muscle and spinal cords from 15C5-Chmra-treated animals in our clinical treatment model were significantly lower than those of controls at 3 days post treatment (Fig. 3B and C). Interestingly, in the days following the initial paralysis onset, 15C5-Chmra treatment seems to be preventing an increase in viral titer within the spinal cord rather than driving a reduction in viral titer (comparison of “Paralysis ≥2” to “3 days post” in Fig. 3C). In muscle, 15C5-Chmra treatment results in a greater reduction of viral titer in the days following initial paralysis, whereas the control animals have far less reduction of viral titer in the muscle during the same window of time (comparison of “Paralysis ≥2” to “3 days post” in Fig. 3B). By 6 days posttreatment, there were no longer significant differences in viral titer (within the spinal cord or muscle) between 15C5-Chmra and control-treated animals, and both groups had viral titers nearing the lower limit of detection (Fig. 3B and C). The paralysis score of each animal was recorded before collecting tissue, and scores were found to be significantly lower in the 15C5-Chmra-treated group at both 3 and 6 days postinfection (data not shown), which is consistent with the decreased spinal cord and muscle tissue titers of these animals. We also measured viral titer in the contralateral (not injected with virus) quadriceps muscle and never found detectible virus in any treatment group at any time point (data not shown), suggesting that virus is spreading through the CNS rather than systemically to infect other muscle groups and their associated peripheral nerves.

FIG 3.

Viral titer in tissue collected from mice infected with EV-D68 (2014 US/IL/14-18952) and treated with monoclonal antibody in clinical treatment model. (A) Pictographic representation of the clinical treatment model (gray, blue, and green arrow) and time points when tissue was collected for panels B and C (yellow arrows). (B) Viral titers in the left (i.m. injected) quadriceps muscle from tissue collected when paralysis score was ≥2 (single purple bar represents samples from untreated animals), 3 days after paralysis score was ≥2, and 6 days after paralysis score was ≥2. There is a significant difference between 15C5-Chmra-treated animals and controls at 3 days postparalysis with a score of ≥2 (Student's t test, *, P = 0.0167). n = 9 to 10 in all groups. Error bars represent SEM. (C) Viral titers in the spinal cord from tissue collected when paralysis score was ≥2 (single purple bar represents samples from untreated animals), 3 days after paralysis score was ≥2, and 6 days after paralysis score was ≥2. There is a significant difference between 15C5-Chmra-treated animals and controls at 3 days postparalysis with a score of ≥2 (Student's t test, *, P = 0.005). n = 9 to 10 in all groups. Error bars represent SEM. (D) 15C5-Chmra, 11G1-Chmra, and control (anti-herpes simplex virus) antibody neutralization (IC50) against 100× TCID50 of EV-D68 isolate US/IL/14-18952. (E) 15C5-Chmra antibody neutralization (IC50) against 100× TCID50 of EV-D68 isolates US/IL/14-18952, 2016-334-74, and 2018-42552.

Neutralization of EV-D68 isolates from 2014, 2016, and 2018.

When we examined the concentration of 15C5-Chmra and 11G1-Chmra required to neutralize EV-D68 in vitro, we found that the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) against the EV-D68 isolate US/IL/14-18952 (which was used for Fig. 1, 2A and 3A–C) was approximately 0.01 μg/mL for 15C5-Chmra and approximately 100 μg/mL for 11G1-Chmra (Fig. 3D). Nearly 10,000× more 11G1-Chmra antibody is required to neutralize US/IL/14-18952 than 15C5-Chmra antibody. When we assessed the IC50 of 15C5-Chmra against a 2016 isolate of EV-D68 (2016-334-74), we found that at least 100-fold more antibody was required to neutralize the 2016-334-74 isolate than was required to neutralize the 2014 isolate (Fig. 3E). We also assessed the IC50 of 15C5-Chmra against a 2018 isolate of EV-D68 and found that even at 1,000 μg/mL, 15C5-Chmra was not able to neutralize the 2018 isolate. Given that the IC50 of 15C5-Chmra against 2016-334-74 was approximately 3 μg/mL and that there was no significant reduction in paralysis score for animals treated with 11G1-Chmra (with an IC50 of approximately 100 μg/mL), we next asked whether 15C5-Chmra would significantly reduce paralysis in mice infected with 2016-334-74.

Efficacy of 15C5-Chmra in clinical treatment model against EV-D68 isolate 2016-334-74.

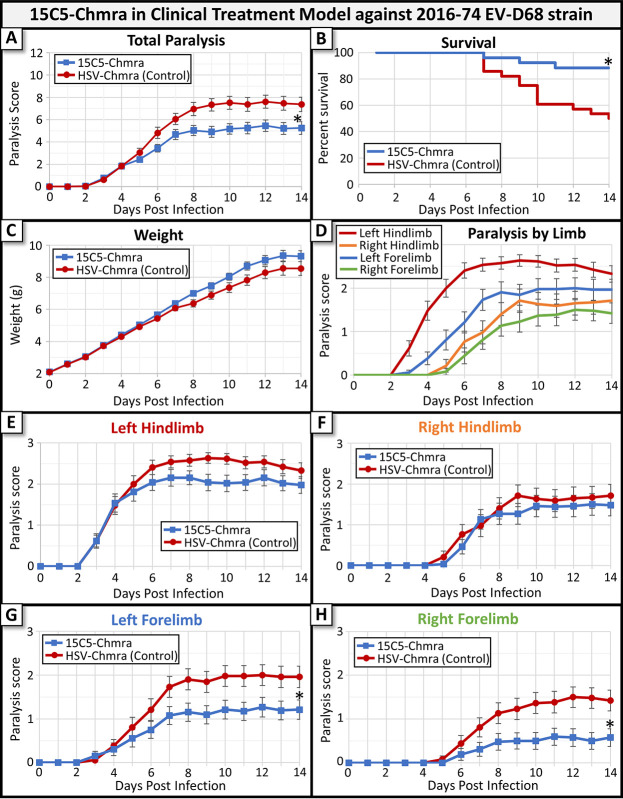

The 2016-334-74 EV-D68 isolate consistently caused paralysis following i.m. injection of Swiss Webster mice. When mice infected with 2016-334-74 were treated with antibody in our clinical treatment model, we found that 15C5-Chmra significantly reduced the severity of paralysis compared to nonspecific antibody-treated controls and increased survival (Fig. 4A and B), but there was only a trend toward increased animal weight in the 15C5-Chmra-treated group (Fig. 4C). Consistent with the reduced neutralization of EV-D68 isolate 2016-334-74 by 15C5-Chmra, we did not observe 100% survival in the 15C5-Chmra-treated group infected with 2016-334-74 (Fig. 4B), as we had when mice were infected with US/IL/14-18952. This data suggests that antibodies that can neutralize virus at lower concentrations will be more effective in a clinical treatment model. To assess whether there were any further changes in paralysis scores beyond our 14-day observation window, we followed mice from this group for 28 days and did not observe any further improvement or decline in paralysis scores in either treatment group beyond 14 days (data not shown). We observed a difference in the time-to-paralysis in each limb when comparing the 2016-334-74 isolate to the US/IL/14-18952 isolate. Mice infected with the 2016-334-74 EV-D68 isolate showed signs of paralysis in the left hindlimb first (as expected); however, the ipsilateral (left) forelimb was the next limb to develop paralysis, followed by the contralateral (right) hindlimb and (right) forelimb (Fig. 4D). We also noted that the severity of paralysis in the forelimbs is greater in mice infected with 2016-334-74 than in mice infected with US/IL/14-18952. These data suggest that there may be a difference between how the 2014 US/IL/14-18952 and 2016 334-74 isolates of EV-D68 spread through the spinal cord, although we do not believe this will have any bearing on efficacy of monoclonal antibody treatment. Despite the differing times-to-paralysis by limb in the two EV-D68 isolates, mice infected with the 2016-334-74 isolate were similar to mice infected with US/IL/14-18952 in showing the greatest reduction in paralysis scores in the forelimbs compared to that of nonspecific antibody-treated controls, while the hindlimbs showed only slight reductions in paralysis (Fig. 4E to H). Consistent with the decreased IC50 of 15C5-Chmra against 2016-334-74, treatment was not able to prevent the development of paralysis in the hindlimbs but did reduce paralysis scores in the forelimbs compared to nonspecific antibody-treated controls (Fig. 4G and 4H).

FIG 4.

Monoclonal antibody treatment of mice infected with EV-D68 (2016 isolate number 74) in a clinical treatment model. In this model, mice were treated with 15C5-Chmra (n = 26) or Control (n = 28) antibody after paralysis score reached or exceeded two (treatment was initiated between 3 and 5 days postinfection). (A) Total paralysis score (0 = unparalyzed; 12 = quadriplegic) over 14-day time course of experiment (control group, n = 28; 15C5-Chmra group, n = 26). 15C5-Chmra had significantly lower paralysis score than control group (*, P = 0.0075, repeated measures ANOVA on day 6 to 14 time points). Error bars represent SEM. (B) Percent survival by treatment group for the same mice as in panel A. There was significantly improved survival in the 15C5-Chmra group compared to that in controls (log-rank test, *, P = 0.0013). (C) Average pup weight by treatment group for the same mice as in panels A and B. There was not a significant difference in weight between the 15C5-Chmra group and controls. Error bars represent SEM. (D) The average paralysis score for each limb across 14 days for the control group. Error bars represent SEM. (E) The average paralysis in the left hindlimb (i.m. infected limb) for each group. 15C5-Chmra versus control; P = 0.0535, repeated measures ANOVA for days 8 to 14. Error bars represent SEM. (F) The average paralysis in the right hindlimb for each group. 15C5-Chmra versus control; P = 0.5407, repeated measures ANOVA for days 9 to 14. Error bars represent SEM. (G) Average paralysis in the left forelimb for each group. 15C5-Chmra versus control; *, P = 0.0202, repeated measures ANOVA for days 7 to 14. Error bars represent SEM. (H) The average paralysis in the right forelimb for each group. 15C5-Chmra versus control; *, P = 0.0088, repeated measures ANOVA for days 7 to 14. Error bars represent SEM.

DISCUSSION

Mitigating paralysis with 15C5-Chmra.

The results presented here indicate that neutralizing antibodies, such as 15C5-Chmra in 2014 EV-D68 isolates, may be an effective treatment for mitigating the progression of paralysis in patients who present clinically with AFM (following EV-D68 infection). Following onset of the initial neurologic symptoms, AFM has the potential to spread to unaffected limbs/nerves within hours to days. AFM lesions are often longitudinally extensive within the spinal cord, and the paralytic disease can progress from weakness in a single limb to complete quadriplegia, which may also affect cranial nerves, the diaphragm, and bulbar muscles (7). We found that treatment of 2014 and 2016 isolates of EV-D68 with 15C5-Chmra is able to slow the progression of paralysis from the injected limb to the contralateral limb and can stop the development of paralysis in the forelimbs. It was not, however, able to reverse paralysis that was present at the time of treatment. This is not surprising since it is unlikely that anti-EV-D68 antibody can rescue the death of motor neurons (the likely cause of paralysis). However, by reducing viral titer in the spinal cord, 15C5-Chmra treatment is likely preventing the death of additional motor neurons that would result from an ongoing EV-D68 infection within the CNS. Consistent with this, we found that the two animals with the highest paralysis scores at 6 days posttreatment (both in the control group) were the same two animals that still had detectible virus in their spinal cords at 6 days posttreatment, suggesting that the more time that virus is active in the spinal cord, the greater the extent of paralysis. Based on this data, we suggest that patients who present with AFM should be treated with antibody therapy as soon as possible to prevent further loss of motor neurons and worsening of paralysis.

Development of an antienterovirus antibody cocktail.

It has proven to be quite difficult to unequivocally identify EV-D68 in patients who present with AFM, likely due to the extended amount of time between the prodromal respiratory illness and the development of AFM. However, since EV-D68 is thought to be a primary cause of AFM, it may be worthwhile to consider the preemptive use of neutralizing antibody prior to or in the absence of a known viral cause for AFM. Given the promising results of neutralizing antibody in our clinical mouse model, we suggest that it would be worthwhile to develop a monoclonal antibody cocktail with neutralizing antibodies against the most common AFM-causing enteroviruses (such as EV-D68 and EV-A71), which is tested annually for neutralization efficacy against circulating isolates. This would allow for the treatment of patients immediately upon AFM diagnosis and prior to identification of a specific viral cause.

In our estimation, it is unlikely that the use of monoclonal antibody therapy for AFM will drive the evolution of antibody-resistant EV-D68 isolates. This is because infection of the CNS often occurs after resolution of the respiratory illness and CNS infection does not enable viral latency, nor does it facilitate spread to a new host. Rather, infection of the CNS is likely to be a dead end for the virus even if the infection goes untreated. It is, however, likely that genetic drift or other environmental factors will drive the emergence of new isolates of EV-D68 that are not neutralized by 15C5-Chmra. Our findings that 15C5-Chmra is highly neutralizing against a 2014 isolate (the original 15C5 antibody was designed against a 2014 EV-D68 isolate), less neutralizing against a 2016 isolate, and ineffective against a 2018 isolate suggest that antibody therapy against AFM will require annual/biennial assessment of antibody efficacy. To combat this, we suggest the development of a cocktail of neutralizing antibodies with unique binding sites and the periodic testing of neutralization against modern viral isolates to maintain antibody efficacy over time.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis of monoclonal antibodies.

15C5-Chmra, 11G1-Chmra, and anti-HSV-Chmra (control) IgG1/K monoclonal antibodies were constructed and provided by ZabBio. Sequences for the variable heavy and variable light domains of the monoclonal antibodies 11G1 and 15C5 were retrieved from the protein data bank deposits 6AJ9 (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/6AJ9) and 6AJ7 (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/6AJ7) as published by Zheng et al. (6). These sequences were then compared to conventional murine antibody domain structures using internal (Mapp) and external databases. In some cases, sequence modifications were made based on known conventions. These variable regions were synthesized, incorporating codon optimization for Mapp’s Nicotiana expression system and 5′/3′ cloning and restriction sites to accommodate expression vector assembly. Expression vectors were then assembled with murine or plant signal peptides and human kappa constant domains. The final “chimeric” antibody sequences, therefore, contain a murine or plant signal peptide (which is cleaved off), a murine variable domain, and a human constant domain. Antibody purity was ≥95% and was assessed using size exclusion chromatography and the LabChip GXII protein characterization system.

Paralysis scoring scale.

Paralysis scores were assessed as previously published by Hixon et al. (4), with the exception that in rare instances, a score of 1.5 or 2.5 was used to better capture limb paralysis that was borderline between bins. Briefly, each limb was scored from 0 to 3, where 0 represents normal limb movement and 3 represents complete loss of function in the limb. The score from each limb was added together to give a total paralysis score of up to 12 for a completely paralyzed, quadriplegic animal. An animal was sacked if its paralysis score was ≥11 or if its weight dropped below 60% of the litter average.

Clinical treatment model.

Litter size was kept constant at 10 animals per dam by mixing litters of the same age. Postnatal day two (P2) Swiss Webster mice of both sexes were intramuscularly injected with 10 μL of EV-D68 at 10,000 TCID50/pup in the left quadriceps muscle. Individual pups were uniquely marked and checked once daily for paralysis. When an individual animal was observed with a paralysis score that was greater than or equal to 2 (paralysis ≥2), either in a single limb (most common) or as a combination of scores from two limbs (rare), the animal was intraperitoneally injected with 25 μL of monoclonal antibody at 15 mg/kg. Antibody vials were labeled “A” and “B” to blind the experimenter, and mice were alternately assigned to treatment groups as they developed paralysis. The paralysis score and weight for each animal was recorded daily. Uniquely marking each animal allowed data from the same animal to be tracked throughout the experiment and allowed the experimenter to retrospectively assign each mouse to its appropriate treatment group (15C5-Chmra versus control). Animals were tracked for a total of 14 days postinfection.

Viral stocks.

Three isolates of EV-D68 were used for this study. US/IL/14-18952 was isolated in 2014 and was purchased from BEI resources. NR-49131 lot number 63205985. 2016-334-74 was isolated in 2016, and 2018-42552 was isolated in 2018. Both 2016 and 2018 isolates were a generous gift from Kirsten St. George and Daryl Lamson at the Wadsworth Center of the NY State Department of Health in Albany.

TCID50 protocol.

RD cells were plated at 3,000 cells/well into 2 sets of 5 columns in a 96-well flat-bottomed cell culture plate. After 24 to 48 h, serial 10-fold dilutions of EV-D68 were added to the appropriate wells and incubated at 33°C for 7 days. All wells were examined for signs of cytopathic effect, and TCID50 values were calculated using the Reed-Muench method. All TCID50 values in this paper represent TCID50/mL even if it is not explicitly stated.

Neutralization assay.

Rhabdomyosarcoma cells were grown in 96-well flat-bottomed cell culture plates for cell-based neutralization assays. Serial 2× dilutions of antibody were mixed with 100× TCID50 EV-D68 and incubated for 60 min prior to introducing virus/antibody mix onto cells. Cytopathic effect was assessed after 7 days at 33°C.

Statistical analysis.

JMP version 15.0.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989–2007) was used for all statistical calculations. We did not observe sex differences in survival or paralysis for any experiment. We did observe litter effects, so all experiments were conducted using a minimum of 4 litters, and pups were mixed and matched between litters whenever possible. For paralysis scores, any animal that died before completion of the 14-day experiment had its last recorded paralysis score carried forward throughout the remainder of the experiment. One animal died of unknown causes prior to the onset of paralysis and was removed from the experiment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lerner AM, DeRocco AJ, Yang L, Robinson DA, Eisinger RW, Bushar ND, Nath A, Erbelding E. 2021. Unraveling the mysteries of acute flaccid myelitis: scientific opportunities and priorities for future research. Clin Infect Dis 72:2044–2048. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Messacar K, Schreiner TL, Van Haren K, Yang M, Glaser CA, Tyler KL, Dominguez SR. 2016. Acute flaccid myelitis: a clinical review of US cases 2012–2015. Ann Neurol 80:326–338. 10.1002/ana.24730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun J, Hu X-Y, Yu X-F. 2019. Current understanding of human enterovirus D68. Viruses 11:490. 10.3390/v11060490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hixon AM, Clarke P, Tyler KL. 2017. Evaluating treatment efficacy in a mouse model of enterovirus D68-associated paralytic myelitis. J Infect Dis 216:1245–1253. 10.1093/infdis/jix468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogt MR, Fu J, Kose N, Williamson LE, Bombardi R, Setliff I, Georgiev IS, Klose T, Rossmann MG, Bochkov YA, Gern JE, Kuhn RJ, Crowe JE, Jr.. 2020. Human antibodies neutralize enterovirus D68 and protect against infection and paralytic disease. Sci Immunol 5:eaba4902. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aba4902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng Q, Zhu R, Xu L, He M, Yan X, Liu D, Yin Z, Wu Y, Li Y, Yang L, Hou W, Li S, Li Z, Chen Z, Li Z, Yu H, Gu Y, Zhang J, Baker TS, Zhou ZH, Graham BS, Cheng T, Li S, Xia N. 2019. Atomic structures of enterovirus D68 in complex with two monoclonal antibodies define distinct mechanisms of viral neutralization. Nat Microbiol 4:124–133. 10.1038/s41564-018-0275-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helfferich J, Knoester M, Van Leer-Buter CC, Neuteboom RF, Meiners LC, Niesters HG, Brouwer OF. 2019. Acute flaccid myelitis and enterovirus D68: lessons from the past and present. Eur J Pediatr 178:1305–1315. 10.1007/s00431-019-03435-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]