Grandparents play an important role in rural Chinese families, often providing extensive and intensive care for grandchildren whose parents have migrated for work opportunities in urban centers. China’s economic growth over the last several decades is, to some degree, predicated on the efforts of grandparents, who enable the migration of workers to locations where productive jobs have been plentiful and return higher wages than jobs in their home communities (Wu & Rao, 2017). However, the social conditions of families and the capacities of older grandparents in China have not been static in recent decades. Declines in fertility have reduced the numbers of grandchildren available to grandparents (Mjelde-Mossey, 2007) while, at the same time, the physical, mental, social, and financial health of older adults have improved due to China’s rapid modernization and economic development (Chen et al., 2010). As a rule, improved health in later life and fertility postponement in younger generations dramatically alter the likelihood and timing of becoming a grandparent, as in patterns observed in the United States (Margolis & Verdery, 2019). Given the speed of such changes in China, as well as the strong integration of grandparents within the family system, we might expect the consequences of these trends to be particularly profound.

In this article, we analyze the Longitudinal Study of Older Adults in Anhui Province, China, and employ a cross-cohort comparative design to examine changes in full-time grandparenting between 2001 and 2018, as well as associated changes in the opportunities and abilities of older adults to provide care to grandchildren.

Background

Grandparenting is a widely researched topic, and evidence suggests that the cultural milieu and degree of welfare state supports have consequences as to whether and how grandparents look after their grandchildren (Baker & Silverstein, 2012; Hank & Buber, 2009). China represents a good case in point, having achieved rapid economic growth while retaining strong filial primacy as a societal norm.

Demographic factors also influence the opportunity for grandparents to provide care for grandchildren. On one hand, as child mortality has declined and life expectancy has increased, older adults are spending more of their lifetimes in the grandparent role (Chen & Liu, 2012; Xu & Chi, 2011). On the other hand, declines in fertility across successive generations have reduced opportunities to interact with grandchildren in their preadult years, creating cross-pressure on enhanced grandparent involvement.

In many countries of the world, grandparents are responsible for caring for their grandchildren when children are challenged to provide such care themselves. In China, this is a common expectation given the collectivistic Confucian culture of China, with its emphasis on family integration and filial responsibility (Zhu et al., 2019). The importance of grandparent-grandchild relationships is exemplified by a cultural script that emphasizes mutual aid and respect between generations (Xu & Chi, 2011). In more traditional, rural areas of China, grandparents are expected to be surrogate care providers for the children of migrant parents, who are themselves obligated to send remittances to these grandparents who were “left behind” (Chen & Liu, 2012; Chen et al., 2015; Tang et al., 2016). From this perspective, caring for grandchildren can be viewed less as a forced choice and more as a strategic family decision designed to optimize overall family well-being in response to dynamic economic conditions.

From this perspective, caring for grandchildren can be viewed less as a forced choice and more as a strategic family decision designed to optimize overall family well-being in response to dynamic economic conditions.

Well-Being of Older Adults in China

The older population in China has achieved remarkable improvements in multiple aspects of their physical, emotional, and material well-being over recent decades (Luo et al., 2019). Research has shown that most older adults in China were able to perform daily activity tasks (Luo et al., 2016) and have improved in their ability to perform these tasks over time (Yang, 2020). Such improvements in physical functioning have likely enhanced the ability of grandparents to provide custodial care for their grandchildren. Further, added years to life, deriving from this health dividend, provide greater opportunities to interact with and provide care for grandchildren (Xu et al., 2014). Not only do better health and increased longevity enable grandparents to provide childcare, but engaging in these care activities is also likely to further benefit their physical and psychological well-being (Tang et al., 2016).

Psychological functioning in relation to grandparenting is an underinvestigated area of research, even though depression has been identified as a persistent problem for older adults in China (Chen et al., 2012). However, research suggests that grandparenting activities produce discernable emotional benefits for grandparents. For instance, grandparents who lived with their grandchildren in the absence of the middle generation suffered from fewer depressive symptoms and were happier than other grandparents (Chi & Mao, 2012; Choi & Zhang, 2021; Silverstein et al., 2006). However, it is unclear whether caring for grandchildren promotes better emotional well-being or whether grandparents with better emotional well-being are more willing and better able to be care providers.

The economic status of the older population of China has also improved in recent years, benefitting the mental health and general well-being of older adults (Hua et al., 2015). Increased financial resources of the older population in rural China have been derived from remittances received from migrant children and financial transfers from upwardly mobile children in “new” China’s emerging middle class. Improvement in the economic well-being of older adults can also be traced to a national policy, introduced in 2009, that provides pensions to rural adults aged 60 and older (Fang & Sakellariou, 2016; Ko & Möhring, 2021). This plan—the New Rural Pension Scheme—provides universal monthly government pension payments, even though these payments tend to be small for those in less developed localities and rural areas of the country. Nevertheless, there is evidence that economic support from children has declined commensurately with the value of pensions, suggesting some degree of substitution between government contributions and intergenerational transfers (Shen & Williamson, 2010). Prior to this pension policy, the family—mostly adult children—was primarily responsible for ensuring the economic sufficiency of older adults (Williamson et al., 2017). Grandparents’ ability to care for grandchildren is likely enhanced by having economic resources that bring tangible benefits to grandchildren (Silverstein & Zhang, 2020) and their older care providers (Hua et al., 2015).

Demand for Childcare by Grandparents

Families in rural China still rely on farming as their chief income-generating activity. Consequently, nonfarming opportunities are quite limited for those in the working-age population, who have resorted to taking jobs in the urban economy where they can earn substantially higher incomes and send remittances back to older parents in their native villages (Cong & Silverstein, 2011). Labor migrants often must geographically separate from their younger children due to restrictions imposed by the household registration system (i.e., hukou) and the prohibitive cost of raising children in urban areas. Grandparents are usually the first choice as custodial care providers for children left behind by migrant parents (Chen & Jiang, 2019; Liu et al., 2020; Xu & Chi, 2011). Another family arrangement in which grandparents provide care for grandchildren is a three-generation household, often with working parents in need of childcare assistance.

Given the amount of effort required to care full-time for grandchildren, it is reasonable to expect grandparents who possess physical, mental, social, and economic resources to be better able to provide care for their grandchildren compared to those who possess fewer such resources. Grandchild care is often framed as a nonnegotiable filial obligation and as only reactive to family demand. In contrast, we consider the capacity of grandparents to fulfill the caregiver role, thus leaving open the possibility that policy interventions that improve the quality of life of older adults may enhance their ability to provide care for grandchildren. We investigate cohort change in the resources of grandparents in relation to the prevalence of providing full-time care for grandchildren.

We examined the issues raised above by conducting a cross-cohort comparison of grandparents in 2001 and 2018 within a particular region of rural China. Specifically, we used data from the Longitudinal Study of Older Adults in Anhui Province, China (for details, see Silverstein et al., 2006). Located in the eastern region of China, the Anhui province is largely rural, with significant labor migration among its working-age population. For this analysis, we organized the data into two cohorts to compare changes in grandparenting between 2001 and 2018 (the more recent 2021 data were not used, to avoid distortions due to coronavirus disease 2019 restrictions). We restricted the analysis to older adults between 60 and 77 years of age in each cohort to standardize chronological age and ensure that there was no overlap of respondents across the two cohorts. The sample sizes in the selected age range were 1,253 in 2001 and 932 in 2018.

Measuring Care for Grandchildren

Each grandparent in the sample was asked whether they provided care to one or more grandchildren (16 years old or younger) parented by each adult child. Response options were six ordinal categories ranging from all day, every day to none. Grandparents were considered full-time caregivers if they provided care all day, every day for at least one set of grandchildren.

Measures of Well-Being

We conceive of the well-being of grandparents as comprising the presence or absence of four resources widely considered necessary for having a reasonably good quality of life (coded in a negative direction, indicating a resource deficit). These deficits or resources include functional limitations (difficulty performing five instrumental activities of daily living), mental distress (nine types of depressive symptoms), social disruption (widowed vs. married status), and economic inadequacy (dissatisfaction vs. satisfaction with one’s current financial condition). To create indicators of difficulties with instrumental activities of daily living and of depressive symptoms, threshold scores were used to create dichotomous variables indicating low versus high resources in these domains (details will be provided upon request to the authors).

Comparative Results

First, we examined differences in the physical, mental, social, and economic well-being of grandparents between the 2001 and 2018 cohorts. Figure 1 shows that each type of well-being improved in the 17 years between cohort assessments. Specifically, the 2018 cohort of grandparents was less likely than the 2001 cohort to have functional limitations and depressive symptoms, be widowed, and experience adverse financial conditions. The improvement in functional health is particularly large and is likely to be the most important qualification for taking care of grandchildren, especially grandchildren in early childhood, who require more energy and diligent supervision on the part of their caregivers.

Figure 1.

Resource deficits and resources among older adults aged 60–77 in 2001 and 2018 cohorts. Abbreviation: IADL, instrumental activities of daily living.

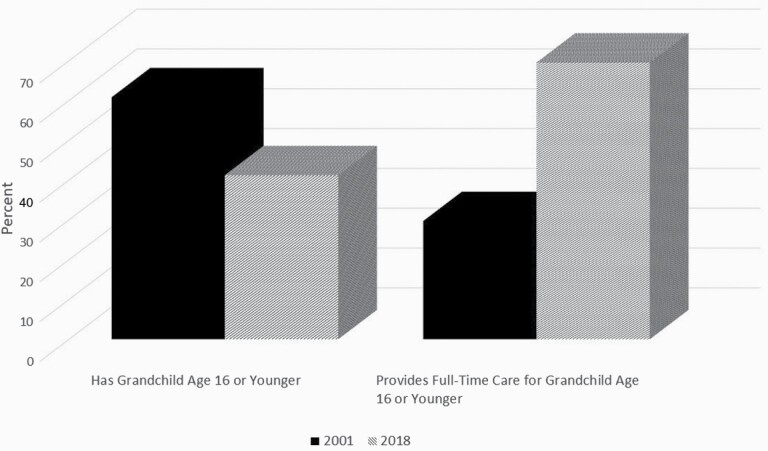

Next, we addressed the following three questions: (1) has the opportunity to provide full-time care for grandchildren declined between 2001 and 2018; (2) conditional on having at least one grandchild 16 years old or younger, are grandparents more likely to provide daily care for grandchildren in 2018 than in 2001; and (3) does the possession of personal resources increase the likelihood that grandparents provide full-time care for grandchildren?

The first two bars in Figure 2 show that the probability of having a preadult grandchild (16 or younger) diminished from 61% to 41% between cohorts, likely as a consequence of declining fertility rates across generations. Indeed, the proportion of older adults in our sample having five or more grandchildren went from 76% in 2001 to 37% in 2018. Clearly, the opportunity to provide care for grandchildren has declined as the family size in descending generations has grown smaller in China.

Figure 2.

Probability of older adults aged 60–77 having a preadult grandchild and conditional probability of providing full-time care for grandchildren in 2001 and 2018 cohorts.

Next, we examined cohort difference in whether grandparents provided full-time care for grandchildren, conditioned on having at least one preadult grandchild. The second two bars in Figure 2 show a dramatic increase in the proportion of grandparents providing full-time care across the two cohorts, rising from 30% in 2001 to 70% in 2018. Thus, while lower fertility has reduced the likelihood that grandparents have a preadult grandchild, those grandparents having at least one such grandchild were far more likely to engage as a full-time caregiver in 2018 than in 2001. Growth in the prevalences of rural-urban migration and dual-earner couples in the working-age population may serve as explanations for such a large increase.

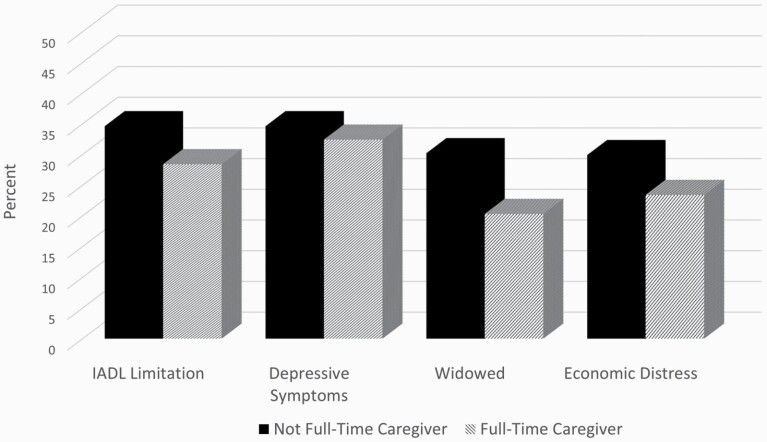

Finally, Figure 3 shows the prevalence of deficits and resources among grandparents by whether they provided full-time care for grandchildren, pooling the 2001 and 2018 cohorts. Full-time caregivers had fewer functional limitations, were less likely to be widowed, and experienced less economic dissatisfaction than other grandparents. There were no differences in depressive symptoms between the two groups.

Figure 3.

Resource deficits and resources among grandparents providing full-time care for grandchildren in pooled 2001 and 2018 cohorts. Abbreviation: IADL, instrumental activities of daily living.

Summary and Policy Considerations

Studying the social patterns of grandparenting in China brings together various, complex changes in Chinese society related to health, fertility, and economic trends that have consequences for individual and family lives. Examining these issues over 17 years provided the opportunity to consider how China’s rapid development has consequences for the family behavior of rural grandparents.

In this article, we examined the role played by grandparents as a key family resource, but one that has been exposed to sharp contextual changes over the last two decades. While fertility decline has reduced opportunities for providing full-time care to grandchildren, the ability of grandparents to serve younger generations was seemingly enhanced over time by the increase in resources available to older adults in rural China.

While fertility decline has reduced opportunities for providing full-time care to grandchildren, the ability of grandparents to serve younger generations was seemingly enhanced over time by the increase in resources available to older adults in rural China.

Grandparent caregivers serve as enablers of economic development in China, albeit indirectly and in ways not always acknowledged. Policies that support grandparent caregiving may be valuable for reducing stress and burnout in this population of older adults and provide added incentives for them to continue their altruistic family activities. Such policies may include inexpensive childcare or respite services to periodically relieve grandparents from the stress of providing intensive care for their grandchildren. In addition, pension bonuses to caregiving grandparents may provide financial relief and indirectly benefit grandchildren whose parents have migrated, as children left behind in rural villages often suffer from behavioral difficulties and emotional distress (He et al., 2012).

While supportive public policies may be viewed as violating norms of filial primacy that characterize rural Chinese society, they can be enacted as family-friendly interventions that benefit not only older adults but also family members in other generations, with whom older adults are interdependent. The interdependence-of-generations perspective is well established in the field of aging, emerging within a social-policy environment threatened by privatization, retrenchment of benefits, and claims of unfairness to younger generations (Bengtson & Achenbaum, 1993). These issues remain persistent challenges to policy development on behalf of older adults and are no less applicable to contemporary China, with its weak social safety net.

Our previous research based on Anhui data showed that grandparent caregivers in China were psychologically and economically advantaged relative to noncaregivers, whereas in the United States the opposite was true (Baker & Silverstein, 2012). Chinese grandparents were involved in a circular exchange of resources that rewarded their caregiving with remittances (Cong & Silverstein, 2008, 2011), and American grandparents tended to be disadvantaged and selected into caregiving due to family distress and crises in the middle generation. Indeed, greater remittance receipts from adult children in rural China improved the psychological and cognitive well-being of grandparents who provided full-time care for grandchildren (Silverstein & Zuo, 2021); this suggests that intergenerational time-for-money reciprocity was beneficial for these caregiving grandparents by providing them with both a purposeful activity and commensurate rewards.

While resources accumulated by one generation are often distributed to other generations in need in both Chinese and American contexts, this pattern appears more evident in China, where mutual exchange and filial obligation more explicitly guide intergenerational transfers. Filial obligation as a core cultural precept should not be underestimated as a social force and may make government supports for older adults more efficient by harnessing the family system as a site of resource redistribution across generations.

Contributor Information

Merril Silverstein, Department of Human Development and Family Science, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, USA; Department of Sociology, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, USA; Aging Studies Institute, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, USA.

Ying Xu, Department of Human Development and Family Science, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, USA; Aging Studies Institute, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, USA.

Funding

This study was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health (R03 TW01060) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71573207 and 72074177). The authors have no financial interests or connections, direct or indirect, or other situations that might raise the question of bias in the work reported or the conclusions, implications or opinions stated – including pertinent commercial or other sources of funding for the individual authors or for the associated departments or organizations, personal relationships, or direct academic competition.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Baker, L., & Silverstein, M. (2012). Grandparents caring for grandchildren in contemporary China: Linchpins of the rural family system. In Arber S. & Timonen V. (Eds.), Contemporary grandparenting: Changing family relationships in a global context (pp. 51–70). Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson, V. L., & Achenbaum, W. A. (Eds.). (1993). The changing contract across generations. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F., Yang, Y., & Liu, G. (2010). Social change and socioeconomic disparities in health over the life course in China: A cohort analysis. American Sociological Review, 75(1), 126–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y., Hicks, A., & While, A. E. (2012). Depression and related factors in older people in China: A systematic review. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 22(1), 52–67. doi: 10.1017/S0959259811000219 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X., & Jiang, X. (2019). Are grandparents better caretakers? Parental migration, caretaking arrangements, children’s self-control, and delinquency in rural China. Crime & Delinquency, 65(8), 1123–1148. doi: 10.1177/0011128718788051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F., & Liu, G. (2012). The health implications of grandparents caring for grandchildren in China. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67(1), 99–112. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F., Mair, C. A., Bao, L., & Yang, Y. C. (2015). Race/ethnic differentials in the health consequences of caring for grandchildren for grandparents. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70(5), 793–803. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi, H., & Mao, S. (2012). The determinants of happiness of China’s elderly population. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 13(1), 167–185. doi: 10.1007/s10902-011-9256-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S. E., & Zhang, Z. (2021). Caring as curing: Grandparenting and depressive symptoms in China. Social Science & Medicine, 289. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong, Z., & Silverstein, M. (2008). Intergenerational time-for-money exchanges in rural China: Does reciprocity reduce depressive symptoms of older grandparents? Research in Human Development, 5(1), 6–25. doi: 10.1080/15427600701853749 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cong, Z., & Silverstein, M. (2011). Intergenerational exchange between parents and migrant and nonmigrant sons in rural China. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73(1), 93–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00791.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Z., & Sakellariou, C. (2016). Social insurance, income, and subjective well-being of rural migrants in China—an application of unconditional quantile regression. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 17(4), 1635–1657. doi: 10.1007/s10902-015-9663-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hank, K., & Buber, I. (2009). Grandparents caring for their grandchildren: Findings from the 2004 Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe. Journal of Family Issues, 30(1), 53–73. doi: 10.1177/0192513X08322627 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He, B., Fan, J., Liu, N., Li, H., Wang, Y., Williams, J., & Wong, K. (2012). Depression risk of “left-behind children” in rural China. Psychiatry Research, 200(2-3), 306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua, Y., Wang, B., Wallen, G. R., Shao, P., Ni, C., Hua, Q. (2015). Health-promoting lifestyles and depression in urban elderly chinese. PLoS ONE, 10(3), e0117998. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko, P. C., & Möhring, K. (2021). Chipping in or crowding-out? The impact of pension receipt on older adults’ intergenerational support and subjective well-being in rural China. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 36(2), 139–154. doi: 10.1007/s10823-020-09422-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D., Xi, J., Hall, B. J., Fu, M., Zhang, B., Guo, J., & Feng, X. (2020). Attitudes toward aging, social support and depression among older adults: Difference by urban and rural areas in China. Journal of Affective Disorders, 274, 85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H., Wong, G. H. Y., Lum, T. Y. S., Luo, M., Gong, C. H., & Kendig, H. (2016). Health expectancies in adults aged 50 years or older in China. Journal of Aging and Health, 28(5), 758–774. doi: 10.1177/0898264315611663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y., Zhang, L., & Pan, X. (2019). Neighborhood environments and cognitive decline among middle-aged and older people in China. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 74(7), e60–e71. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbz016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis, R., & Verdery, A. M. (2019). A cohort perspective on the demography of grandparenthood: Past, present, and future changes in race and sex disparities in the United States. Demography, 56(4), 1495–1518. doi: 10.1007/s13524-019-00795-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mjelde-Mossey, L. A. (2007). Cultural and demographic changes and their effects upon the traditional grandparent role for Chinese elders. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 16(3), 107–120. doi: 10.1300/10911350802107785 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, C., & Williamson, J. B. (2010). China’s new rural pension scheme: Can it be improved? International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 30(5/6), 239–250. doi: 10.1108/01443331011054217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, M., Cong, Z., & Li, S. (2006). Intergenerational transfers and living arrangements of older people in rural China: Consequences for psychological well-being. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61(5), S256–266. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.5.s256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, M., & Zhang, W. (2020). Grandparents’ financial contributions to grandchildren in rural China: The role of remittances, household structure, and patrilineal culture. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 75(5), 1042–1052. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbz009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, M., & Zuo, D. (2021). Grandparents caring for grandchildren in rural China: Consequences for emotional and cognitive health in later life. Aging and Mental Health, 25(11), 2042–2052. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1852175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, F., Xu, L., Chi, I., & Dong, X. (2016). Psychological well-being of older Chinese-American grandparents caring for grandchildren. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 64(11), 2356–2361. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, J. B., Fang, L., Calvo, E. (2017). Rural pension reform in China: A critical analysis. Journal of Aging Studies, 41, 67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D., & Rao, P. (2017). Urbanization and income inequality in China: An empirical investigation at provincial level. Social Indicators Research, 131(1), 189–214. doi: 10.1007/s11205-016-1229-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L., & Chi, I. (2011). Life satisfaction among rural Chinese grandparents: The roles of intergenerational family relationship and support exchange with grandchildren. International Journal of Social Welfare, 20(Suppl 1), S148–S159. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2397.2011.00809.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L., Silverstein, M., & Chi, I. (2014). Emotional closeness between grandparents and grandchildren in rural China: The mediating role of the middle generation. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 12(3), 226–240. doi: 10.1080/15350770.2014.929936 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. (2020). Characterizing long term care needs among Chinese older adults with cognitive impairment or ADL limitations. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 35(1), 35–47. doi: 10.1007/s10823-019-09382-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M., Keene, D. E., & Monin, J. K. (2019). “Their happiness is my happiness”−Chinese visiting grandparents grandparenting in the US. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 17(3), 311–326. doi: 10.1080/15350770.2019.1575781 [DOI] [Google Scholar]