Abstract

Mortality from chronic liver disease (CLD) in the UK has increased by over 400% since 1970, driven by alcohol, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatitis C virus, the natural histories of which can all be improved by early intervention. Patients often present with advanced disease, which would be preventable if diagnosed earlier and lifestyle change opportunities offered.

Liver function tests (LFTs) are very commonly measured. Approximately 20% are abnormal, yet the majority are not investigated according to guidelines. However, investigating all abnormal LFTs to identify early liver disease would overwhelm services. Recently, several diagnostic pathways have been implemented across the country; some focus on abnormal LFTs and some on stratifying at-risk populations.

This review will collate the evidence on the size of the problem and the challenges it poses. We will discuss the limitations and restrictions within systems that limit the responses available, review the current pathways being evaluated and piloted in the UK, and explore the arguments for and against LFT-based approaches and ‘case-finding strategies’ in the community diagnosis of liver disease. Furthermore, the role of fibrosis assessment methods (including scoring systems such as Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index, the enhanced liver fibrosis test and elastography) within these pathways will also be discussed.

In conclusion, this review aims to establish some principles which, if adopted, are likely to improve the diagnosis of advanced liver disease, and identify the areas of contention for further research, in order to establish the most effective community detection models of liver disease.

Keywords: chronic liver disease, screening, liver function test, primary care

Key points.

Mortality from chronic liver disease (CLD) has risen dramatically since 1970, driven by increases in alcohol consumption, obesity and components of the metabolic syndrome, as well as hepatitis C (HCV).

Most patients present late in the disease process, often by an index hospital admission with decompensated cirrhosis.

90% of CLD is caused by reversible and avoidable factors including alcohol, the metabolic syndrome and HCV.

Early detection of those at risk of advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis would theoretically allow lifestyle interventions and treatments, thus halting the disease process and reducing morbidity and mortality, but primary care often struggles to identify the correct patients for specialist referral.

Several community identification pathways have been developed across the UK in recent years.

The optimum way to identify such patients without overwhelming services is debated; is it those with abnormal liver function tests, those with risk factors for liver disease, or both?

The increasing burden of liver disease poses multiple challenges. Primary and secondary care must develop strategies to improve the diagnosis and management of chronic liver disease (CLD) or face being overwhelmed by the needs of our patients.

Since 1970, mortality from CLD in the UK has risen significantly. While illnesses such as cardiovascular disease have seen improvements, age-standardised deaths from liver disease have risen by 400%.1 Liver disease is the leading cause of death in the 35–49 age group, and the third-leading cause of death in under-65s.2

The most frequent causes of CLD are alcohol related liver disease (ARLD), non-alcoholic (metabolic) fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and viral hepatitis. These are preventable, and hepatitis C (HCV) is now curable. Approximately 5%–10% of patients with liver cirrhosis will develop hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the eighth most frequent cause of cancer death in the UK,3 with incidence and mortality rates trebling between 1997 and 2017.4

The financial impact of CLD is staggering. In England and Wales, around 60 000 people are known to have cirrhosis, with approximately 69 000 annual hospital admissions and 11 500 deaths in England alone.5 However, cirrhosis is vastly under-diagnosed, and its population prevalence is estimated at 0.1%–1.7%, which could mean as many as 1 million people living with the condition unknowingly.6 Cirrhosis is often first diagnosed when patients present to secondary care with complications of portal hypertension or liver cancer.7 The Scottish Alcoholic Liver Disease Evaluation identified 35 208 incident ARLD hospital admissions in Scotland between 1991 and 2011; with a mean cost of £6664 per admission. The average lifetime healthcare cost for a male aged 50–59, living in the most deprived areas, was £65 999 more than controls.8

More generally, the UK spends £3.5 billion per year on alcohol-related health problems and £5.5 billion per year on obesity-related health problems—likely a significant underestimate given the role of obesity in common cancers.9

Despite this, CLD is still diagnosed late in the disease process. The protracted natural history of the disease, involving progressive fibrosis leading to cirrhosis, alongside established risk factors (alcohol misuse, obesity, metabolic syndrome), means there is ample opportunity for earlier diagnosis—ultimately 90% of CLD (ARLD, NAFLD and viral hepatitis) is preventable. Earlier diagnosis would permit interventions (eg, alcohol brief interventions, antiviral therapies and weight loss) before the onset of irreversible disease. However, in a health service already struggling to provide high standards of care to patients with established disease, finding time to prioritise patients who are healthy but at-risk is challenging.

HCV is curable; thus, identification of patients has a clear benefit. Diagnosing patients with early ARLD and NAFLD could allow monitoring of disease progression, thus identifying cirrhosis earlier and reducing the risk of decompensating events by starting surveillance for varices and HCC. It is unclear whether a diagnosis of liver disease provides a stimulus to behaviour change in terms of reduction in alcohol consumption or weight loss. A recent systematic review highlights the possibility of a response to brief interventions with incorporation of liver damage markers but requires further prospective studies to confirm the benefits of this approach.10 In NAFLD, patients who have fibrosis only, suffer from vascular events and non-liver cancers whereas those with cirrhosis suffer from liver-related events such as hepatic decompensation and HCC.11 The Oxford Metabolic Liver Clinic offers lifestyle advice, signposting to weight loss services and pharmacological treatment of diabetes and cardiovascular risk. This has resulted in significant reductions in weight, ALT levels and total cholesterol, as well as lowering cardiovascular risk, and is cost-effective.12 In Glasgow, patients with NAFLD were eligible for funded weight management services through ‘Weight Watchers’, and 25% achieved the EASL-recommended weight loss target of 7%–10%.13 Another NAFLD clinic in north-west England offered a 12-week lifestyle intervention programme, but while patients had significant weight loss, this did not result in significant reduction in either ALT levels or total cholesterol. However, only 9.6% (n=16) of patients offered the programme completed it. While the lack of ALT and cholesterol reduction may be related to the low-power of the study, the lack of uptake is concerning.14 These mixed results show the importance of identifying the most optimal interventions. Factors impacting the ‘benefit’ of such interventions will include reduction in alcohol intake and weight loss, but also long-term outcomes including liver complications, death and quality of life indices, as well as cost-effectiveness.

In 2013, the Lancet Commission on liver disease highlighted areas of improvement to provide excellence in care. Several areas focus on government policy (eg, alcohol minimum unit pricing, obesity epidemic strategies) and secondary care (eg, developing district general hospital liver units with dedicated hepatologists). However, the report also highlighted that over 75% of patients had never been referred to liver services before their first hospital admission with decompensated CLD, and a key recommendation was the need for strengthening the detection of liver disease in its early stages.1 An important method of enacting this is the developing protocols for investigation and clarifying referral criteria to secondary care. The final iteration of this report in 2020 underlined the need to improve early detection and the successor forum of this commission, the UK Liver Alliance, has adopted these same themes.15

The primary method of identifying patients with CLD has historically been liver function tests (LFTs), a term commonly used despite the standard panel (bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transferase) being measures of serum levels of liver enzymes rather than liver function.

The ALFIE study followed 95 977 patients in Tayside and found 21.7% had at least one abnormal liver enzyme, with 1090 patients developing CLD during the follow-up timeframe.16 In the BALLETS study,17 around 5% of patients with abnormal LFTs had what the authors termed ‘significant’ liver disease, defined as cirrhosis from NAFLD or ARLD, or deranged LFTs caused by viral, metabolic, autoimmune, neoplastic and infectious aetiologies.

Abnormalities in ALT level are controversial. The upper limit of normal (ULN) in most UK Labs is set at 40–55 µ/L. Patients with advanced liver disease may have an ALT level below this, due to unrecognised NAFLD and/or ARLD in reference populations. A review of the community prevalence of liver disease further underlined this issue; using traditional ALT levels can result in 90% of cirrhotic patients being missed; whereas only 26.7% of cirrhotic patients have a ‘normal’ ALT when lower ULNs are used.6 As a result, to facilitate CLD diagnosis, either the ULN of ALT should be reconsidered, or case-finding programmes to identify patients by risk factor, rather than LFTs, should be developed—though the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines indicate that the cost-effectiveness of widespread screening, is not yet confirmed.18

Following identification of patients at risk of CLD, the presence or absence of liver fibrosis or cirrhosis can be assessed using various non-invasive scoring systems (eg, NAFLD Fibrosis Score (NFS), FIB-4 score, AST:ALT ratio), which have high negative predictive values and can exclude patients at low risk of advanced fibrosis.19–21 Subsequent blood tests (eg, enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) test), or imaging (eg, transient elastography (TE), acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI)) can then be performed, which have strong overall diagnostic accuracy for advanced liver fibrosis.22 This prevents the need for liver biopsy, which has large intrauser variability and has associated significant risks including bleeding and death.

In recent years, various community pathways to detect liver disease have been developed. The aim is to identify patients who are likely to progress to liver-related complications so that specific interventions can be targeted where there is likely to be the greatest yield in terms of liver-related morbidity and mortality. Some use abnormal LFTs, which is a common problem in primary care. However, most people with abnormal LFTs do not have liver disease, and many patients with liver disease have ‘normal’ ALT. Others focus on at-risk populations, to identify liver disease in those with diabetes, the metabolic syndrome or alcohol misuse—but the numbers of these are even greater than those with abnormal LFTs. Combining such strategies would still result in missing patients with liver disease and normal LFTs. A summary of examples of the main techniques for community detection programmes for liver disease is shown in table 1. The different organisational structures in place for the provision of healthcare across the country, for example with NHS Trusts and Clinical Commissioning Groups in England and Health Boards in Scotland and Wales, means that the development of diagnostic pathways has thus far remained a local issue resulting in several programmes, rather than producing a single, national approach.

Table 1.

Summary of published community pathways for detection of liver disease in the UK

| Pathway | LFT or risk factor | Input from Primary Care | Next steps | Outcome |

| Camden and Islington NAFLD Pathway25 | LFT | Calculate FIB-4 after clinically diagnosing NAFLD (based on elevated ALT, non-harmful alcohol use±steatosis on US) | If FIB-4 elevated, patient referred to secondary care; if FIB-4 indeterminate, GP then performs ELF | If ELF elevated, refer to secondary care |

| Gateshead Project28 | Risk factor | FIB-4 calculated at routine diabetic clinic | If FIB-4 elevated, GP refers for TE | Patients with abnormal TE referred to secondary care |

| Gwent AST Project24 | LFT | Request LFTs | Automated reflex AST with AST:ALT ratio calculation | If AST:ALT ratio≥1, direct access to TE provided |

| Intelligent liver function testing (iLFT)23 | LFT | Request LFTs and provide BMI, alcohol intake and comorbidities at time of request | Automated reflex testing of full aetiological liver screen with non-invasive fibrosis scores and ELF where indicated | 32 individual outcomes detailing likely aetiology, stage of fibrosis and management plan including if/when to refer to secondary care |

| Leeds Community Hepatology Pathway (CHEP)29 | LFT and risk factor (‘GP suspicion’) | Perform ELF in patients with suspected CLD | If ELF elevated, GP refers for community TE | If TE elevated, specialist review |

| Scarred Liver Project26 | Risk factor | Complete algorithm for patients at risk | If meet criteria, patient referred directly for TE | All patients provided with liver health information from British Liver Trust; patients with abnormal TE referred to secondary care |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; CLD, chronic liver disease; ELF, enhanced liver fibrosis; FIB-4, Fibrosis-4; LFT, liver function test; NAFLD, non-alcoholic (metabolic) fatty liver disease; TE, transient elastography.

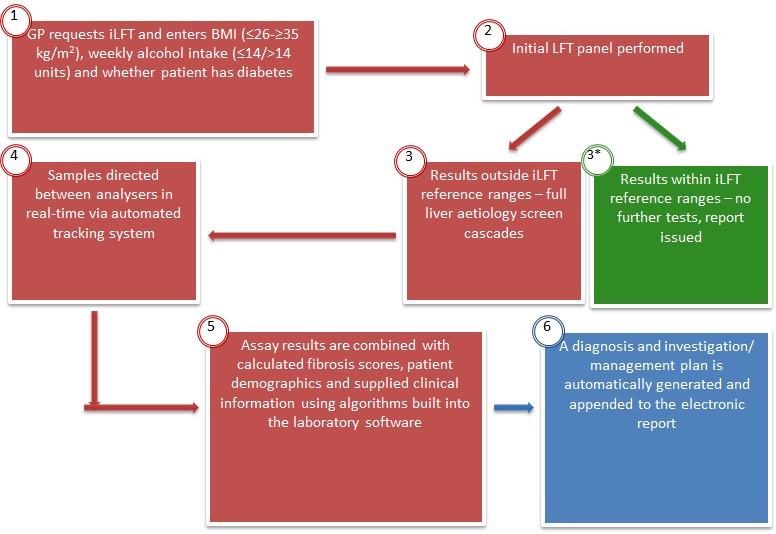

Intelligent liver function testing (iLFT) is a system in Tayside, in which general practitioners (GPs) provide the patient’s body mass index, alcohol intake and metabolic syndrome features when requesting LFTs. Patients with abnormal LFTs automatically have a full ‘liver screen’ performed on the original sample and fibrosis scores (FIB-4 and NFS) calculated. If these are abnormal, an ELF is performed, and the referrer is provided with a likely aetiology for the abnormal LFTs, with a management plan including whether referral to hepatology services is indicated (figure 1). A pilot study demonstrated iLFT increases the diagnosis of liver disease by 43%, costing £284 per correct diagnosis and saving the NHS £3216 per patient lifetime.23 iLFT is now available in NHS Tayside, with over 7000 requests in 3 years. A wide range of liver disease has been diagnosed including ARLD, NAFLD, viral and autoimmune liver diseases. While iLFT is triggered by any abnormal liver enzyme, the ALT ULN is 30 µ/L, removing some of the risk of missing patients with advanced liver disease who happen to have a lower ALT. The Gwent AST Project (GAP) in South Wales has followed a similar model. Patients with abnormal ALT have a reflex AST performed, and the AST:ALT ratio is calculated. GPs are advised to refer patients for fibrosis assessment (usually TE) if the ratio is≥1. In the first 2 years of the project, 17 770 patients had an elevated ALT, with 2117 having an AST:ALT ratio≥1. Three hundred and forty-eight patients had TE, with 57% having an abnormal liver stiffness (≥8 kPa).24

Figure 1.

iLFT pathway. BMI, body mass index; iLFT, intelligent liver function testing; LFT, liver function test.

The Camden and Islington NAFLD Pathway aims to stratify patients with NAFLD between primary and secondary care, using a two-step approach for those with an elevated ALT and clinically diagnosed NAFLD. Patients have a FIB-4 score performed; if elevated, patients are referred to secondary care. Patients with an indeterminate score have an ELF test performed. The pathway increased the diagnosis of advanced liver disease by five times, and resulted in an 88% reduction in ‘unnecessary’ referrals.25 This pathway remains non-invasive and patients only attend for venepuncture, unlike GAP where automatic TE appointments resulted in some non-attendance. The authors of the Camden and Islington NAFLD pathway, however, originally favoured a pathway based on risk factors for NAFLD (obesity, type 2 diabetes), rather than ALT. The ALT-based entry criteria were finalised following concerns regarding the large volumes of patients who may require referral if risk factor-based entry criteria were used instead.

The Scarred Liver Project is a well-established commissioned pathway in Nottingham. GPs are invited to refer patients directly for TE if they are at risk of CLD (eg, harmful alcohol intake and/or features of metabolic syndrome with an elevated AST:ALT ratio). All patients attending for TE are provided with information on how to maintain good liver health. In the first year, 968 patients were referred, with 222 (22.9%) patients stratified to be at risk of advanced fibrosis.26 This pathway eliminates the reliance on LFTs, and therefore patients are not missed simply due to a false reassurance of ‘normal’ liver enzymes; 21% of patients had a normal ALT at referral. However, the need to attend for a further appointment, particularly in patients who feel they are healthy, requires a degree of motivation. An economic evaluation has demonstrated that compared with standard clinical practice the pathway has an 85% probability of cost-effectiveness at the UK willingness to pay threshold of £20 000 per quality adjusted life year.27

The Gateshead Project involves incorporating liver fibrosis assessment into routine diabetic clinics in primary care. In a pilot study, 477 patients at two participating GP Practices had FIB-4 performed at their routine check-up for type 2 diabetes. Patients with abnormal scores were referred for TE and then to liver clinic if indicated. 4.8% of patients were found to have advanced liver disease, and 46% of these had a ‘normal’ ALT28; once again providing confirmation that the ULN of ALT must be lower or not be considered at all.

The Leeds Community Hepatology Clinic (CHEP) for NAFLD uses a two-stage assessment of fibrosis. Patients have an ELF test and, if elevated (>9.5), are referred to a ‘CHEP’ appointment where they undergo TE. In the pilot cohort, ELF was <9.5 in over half of cases, and only 0.7% of those with a low ELF had elevated TE. 10% of patients with elevated ELF had an elevated TE and required secondary care review. The CHEP pathway was more cost-effective than traditional methods of direct referral to secondary care by GPs.29

The recent Lancet Commission on Liver Disease in Europe describes regional and national programmes, including the working group of the Catalan Society of Digestive Diseases, which encompasses a Primary Care Physicians Society, an Endocrinologist Society and the Digestive Society, which produced a consensus document on how and who to screen for liver disease as well as who to refer to secondary or tertiary care settings, essentially providing an algorithm for primary care practitioners to rule out liver fibrosis in patients with possible NAFLD.30 In Finland, a national guideline for NAFLD was published in January 2020.31 In Crete, Greece, a collaborate project was been initiated which will create a state-of-the-art training programme for primary care professionals to allow the implementation of patient care pathways and integrated actions between primary, secondary and tertiary care in NAFLD and will be implemented not just in Greece but also Spain and the Netherlands.32 A study in Barcelona highlighted the results of general population screening for liver disease; in a programme involving 3076 individuals with no known history of liver disease, 3.6% were found to have TE scores of greater than 9.2 kPa, suggestive of fibrosis stages F2 or greater, and when combined with liver disease risk factors and a high fatty liver index value, 92.5% of individuals with an elevated TE score were identified.33

In order to deal with the large number of patients who are likely to require assessment for liver fibrosis after pathways are established, further protocols will be required in order to assess patients in a cost-effective manner. While liver biopsy is the gold standard in diagnosing cirrhosis and advanced fibrosis, it is an invasive procedure which carries high risk in terms of significant bleeding and even death. TE, ELF and ARFI are all non-invasive methods of assessing fibrosis. An integrated primary/secondary care pathway specific to NAFLD in Portsmouth involves nurse-led assessment of patients followed by TE. This pathway resulted in 70.8% of referred NAFLD patients being discharged from clinic, providing an effective assessment tool without overwhelming liver clinics.34

Finally, debate exists surrounding which stage of liver disease is beneficial to detect. It is well documented that only a small proportion of patients with significant fibrosis will develop liver-related events such as hospital admission with decompensated liver disease, HCC or death. Patients with NAFLD fibrosis are more at long-term risk of cardiovascular events than liver related ones. Only 20% of patients with ultrasound evidence of hepatic steatosis will develop steatohepatitis, and only 2.5% of these patients progress to cirrhosis.35 However, some developing pharmacological therapies are targeted at patients with F2 and F3 fibrosis, thus these patients require identification in some way to allow therapies to be used effectively. Advanced, irreversible fibrosis or cirrhosis is associated with worse outcomes, and earlier identification allows intervention.36

Those who provide liver services face a dilemma. The mortality and prevalence of CLD has risen dramatically over the past four decades. Patients with early stages of liver fibrosis need to be identified, to prevent progression to cirrhosis by utilising lifestyle interventions and, in the future, any potential pharmacological interventions. Identifying patients with early liver disease is also necessary to prevent future decompensating events which currently drive admissions and would subsequently improve the care and mortality of these patients. However, unless effective triage systems are developed, liver services are at risk of being overwhelmed by the number of patients. Conversely, identifying patients with risk factors such as obesity and hazardous alcohol intake will increase the demand on community services designed to provide interventions to these problems. A large-scale cost-effectiveness analysis of increasing support to these services has not been undertaken and would be beneficial. However, at a population level, government strategies such as minimum-unit alcohol pricing and a so-called ‘sugar tax’ on high-sugar food and drinks can be beneficial while generating income. For example, minimum-unit alcohol pricing resulted in a 7.7% and 8.6% reduction in alcohol sales in Scotland and Wales, respectively, with the biggest reduction seen among the heaviest drinkers.37

Advances in our ability to diagnose and treat the major causes of chronic illness creates a growing burden of expectation and responsibility to detect treatable disease. GPs will need access to affordable diagnostic strategies that can be applied at scale, and those tests must be both sufficiently specific and sensitive to stratify the large numbers of patients on their lists at risk to yield manageable numbers of ‘cases’ highly likely to have the disease warranting specialist care. It remains to be seen if the currently available liver fibrosis tests are adequate to achieve this goal in CLD but from the existing exemplars cited in this commentary their wider adoption and diffusion would improve current practice that both fails to detect treatable liver disease and yet overwhelms specialist services with unnecessary referrals. Abnormal LFTs provide an opportune window for GPs to investigate for CLD; but many patients with significant disease have normal LFTs, meaning some patients are missed. Therefore, the addition of ‘case-finding’ pathways allow more patients to be identified.

Among interested stakeholders there is a need for ongoing debate about which patients to risk stratify and what stage of fibrosis needs to be targeted. Collaboration and development of an evidence-based consensus is required to diagnose early liver disease with the aim of reducing liver related complications and mortality without overwhelming services. One such way would be to undertake primary research studies to identify the optimal approach(es) as recommended in box 1. Nationwide implementation of early detection pathways will go some way to addressing the tsunami of liver disease facing gastroenterology departments across the country. However, while many unanswered questions remain, all gastroenterologists will agree that anything better than the current standard of care is better than nothing.

Box 1. Research questions facing the hepatology community regarding diagnosis of liver disease.

What are the important research questions to answer to improve the diagnosis of liver disease?

Are pathways that make earlier diagnosis of liver disease beneficial to patients, in terms of liver outcomes, mortality, and quality of life?

What is the best approach to diagnose liver disease—use abnormal LFTs, identify patients with risk factors, or both?

Is early detection of ARLD or NAFLD related hepatic steatosis, in the absence of fibrosis, helpful?

What is the best approach to identify liver fibrosis—blood biomarkers or imaging?

ARLD, alcohol related liver disease; LFT, liver function test; NAFLD, non-alcoholic (metabolic) fatty liver disease.

Footnotes

Twitter: @drdina_mansour, @stumcp, @GwentLiverUnit

Collaborators: Specialist Interest Group in the Early Detection of Liver Disease Members: John F Dillon, Andrew Yeoman, Kushala Abeysekera, William Alazawi, Richard Aspinall, Paul N Brennan, Johnny Cash, Matthew Cramp, Tim Cross, Kate Glyn-Owen, Fiona Gordon, Neil Guha, Rebecca Harris, Helen Jarvis, Moby Joseph, Iain Macpherson, Dina Mansour, Stuart McPherson, Joanne Morling, Philip Newsome, James Orr, Richard Parker, William Rosenberg, Ian Rowe, Ankur Srivastava, Leanne Stratton, Emmanouil Tsochatzis, Fidan Yousuf.

Contributors: IM took the lead in writing the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: KWMA has received lecture fees from Intercept Pharma and a grant from the David Telling Charitable Trust unrelated to this work, DM has received consultancy fees from Intercept Pharma unrelated to this work, SM has received personal fees from MSD, AbbVie and Gilead unrelated to this work, IR has received consultancy fees from Roche unrelated to this work, WR has received speakers fees and research support from Siemens Healthineers unrelated to this work, and is an inventor of the Enhanced Liver Fibrosis Score but has not received royalties in this regard. No other authors have any competing interests related to this work.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Contributor Information

Specialist Interest Group in the Early Detection of Liver Disease Members:

John F Dillon, Andrew Yeoman, Kushala Abeysekera, William Alazawi, Richard Aspinall, Paul N Brennan, Johnny Cash, Matthew Cramp, Tim Cross, Kate Glyn-Owen, Fiona Gordon, Neil Guha, Rebecca Harris, Helen Jarvis, Moby Joseph, Iain Macpherson, Dina Mansour, Stuart McPherson, Joanne Morling, Philip Newsome, James Orr, Richard Parker, William Rosenberg, Ian Rowe, Ankur Srivastava, Leanne Stratton, Emmanouil Tsochatzis, and Fidan Yousuf

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study does not involve human participants.

References

- 1. Williams R, Aspinall R, Bellis M, et al. Addressing liver disease in the UK: a blueprint for attaining excellence in health care and reducing premature mortality from lifestyle issues of excess consumption of alcohol, obesity, and viral hepatitis. Lancet 2014;384:1953–97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61838-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. British Liver Trust . The alarming impact of liver disease in the UK: facts and statistics. United Kingdom, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cancer research UK. Available: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/mortality#heading-Four

- 4. Burton A, Tataru D, Driver RJ, et al. Primary liver cancer in the UK: incidence, incidence-based mortality, and survival by subtype, sex, and nation. JHEP Rep 2021;3:100232. 10.1016/j.jhepr.2021.100232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Public Health England . Liver disease profiles: short statistical commentary, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harris R, Harman DJ, Card TR, et al. Prevalence of clinically significant liver disease within the general population, as defined by non-invasive markers of liver fibrosis: a systematic review. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2:288–97. 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30205-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hussain A, Patel PJ, Rhodes F, et al. Decompensated cirrhosis is the commonest presentation for NAFLD patients undergoing liver transplant assessment. Clin Med 2020;20:313–8. 10.7861/clinmed.2019-0250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bouttell J, Lewsey J, Geue C, et al. The Scottish alcoholic liver disease evaluation: a population-level matched cohort study of hospital-based costs, 1991-2011. PLoS One 2016;11:e0162980. 10.1371/journal.pone.0162980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bhaskaran K, Douglas I, Forbes H, et al. Body-Mass index and risk of 22 specific cancers: a population-based cohort study of 5·24 million UK adults. Lancet 2014;384:755–65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60892-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Subhani M, Knight H, Ryder S, et al. Does advice based on biomarkers of liver injury or non-invasive tests of liver fibrosis impact high-risk drinking behaviour: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Alcohol Alcohol 2021;56:185–200. 10.1093/alcalc/agaa143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vilar-Gomez E, Calzadilla-Bertot L, Wai-Sun Wong V, et al. Fibrosis severity as a determinant of cause-specific mortality in patients with advanced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a Multi-National cohort study. Gastroenterology 2018;155:443–57. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moolla A, Motohashi K, Marjot T, et al. A multidisciplinary approach to the management of NAFLD is associated with improvement in markers of liver and cardio-metabolic health. Frontline Gastroenterol 2019;10:337. 10.1136/flgastro-2018-101155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. I RS H, Blair M, Cairns H, et al. PO337: funded referral to a commercial weight loss provider is effective in achieving weight loss in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2021;75:S611. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Patanwala I, Molnar LE, Akerboom K, et al. Direct access lifestyle training improves liver biochemistry and causes weight loss but uptake is suboptimal in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Frontline Gastroenterol 2021;12:557–63. 10.1136/flgastro-2020-101669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Williams R, Aithal G, Alexander GJ, et al. Unacceptable failures: the final report of the Lancet Commission into liver disease in the UK. Lancet 2020;395:226–39. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32908-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Donnan PT, McLernon D, Dillon JF, et al. Development of a decision support tool for primary care management of patients with abnormal liver function tests without clinically apparent liver disease: a record-linkage population cohort study and decision analysis (ALFIE). Health Technol Assess 2009;13. 10.3310/hta13250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Armstrong MJ, Houlihan DD, Bentham L, et al. Presence and severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in a large prospective primary care cohort. J Hepatol 2012;56:234–40. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Newsome PN, Cramb R, Davison SM, et al. Guidelines on the management of abnormal liver blood tests. Gut 2018;67:6–19. 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Angulo P, Hui JM, Marchesini G, et al. The NAFLD fibrosis score: a noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology 2007;45:846–54. 10.1002/hep.21496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology 2006;43:1317–25. 10.1002/hep.21178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McPherson S, Stewart SF, Henderson E, et al. Simple non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems can reliably exclude advanced fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut 2010;59:1265–9. 10.1136/gut.2010.216077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wahl K, Rosenberg W, Vaske B, et al. Biopsy-controlled liver fibrosis staging using the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) score compared to transient elastography. PLoS One 2012;7:e51906. 10.1371/journal.pone.0051906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dillon JF, Miller MH, Robinson EM, et al. Intelligent liver function testing (iLFT): a trial of automated diagnosis and staging of liver disease in primary care. J Hepatol 2019;71:699–706. 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.05.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yeoman A, Samuel D, Yousuf DF, et al. Introduction of “reflex” AST testing in primary care increases detection of advanced liver disease: the Gwent AST project (GAP). J Hepatol 2020;73:S19. 10.1016/S0168-8278(20)30595-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Srivastava A, Gailer R, Tanwar S, et al. Prospective evaluation of a primary care referral pathway for patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2019;71:371–8. 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chalmers J, Wilkes E, Harris R, et al. The development and implementation of a commissioned pathway for the identification and stratification of liver disease in the community. Frontline Gastroenterol 2020;11:86–92. 10.1136/flgastro-2019-101177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tanajewski L, Harris R, Harman DJ, et al. Economic evaluation of a community-based diagnostic pathway to stratify adults for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a Markov model informed by a feasibility study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015659. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mansour D, Grapes A, Herscovitz M, et al. Embedding assessment of liver fibrosis into routine diabetic review in primary care. JHEP Rep 2021;3:100293. 10.1016/j.jhepr.2021.100293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hinkson AWJ, Canter T, Ong E. PO-1125 using the enhanced liver fibrosis test in primary care: a practical pathway to priotise patients with fibrosis in fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2021;75:S191–866. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Caballeria L, Augustin S, Broquetas T, et al. Recommendations for the detection, diagnosis and follow-up of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in primary and hospital care. Med Clin 2019;153:169–77. 10.1016/j.medcli.2019.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yki-Järvinen HAP, Eskelinen S, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Karlsen TH, Sheron N, Zelber-Sagi S, et al. The EASL-Lancet liver Commission: protecting the next generation of Europeans against liver disease complications and premature mortality. Lancet 2022;399:61–116. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01701-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Caballería L, Pera G, Arteaga I, et al. High prevalence of liver fibrosis among European adults with unknown liver disease: a population-based study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:1138–45. 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.12.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fowell AJ, Fancey K, Gamble K, et al. Evaluation of a primary to secondary care referral pathway and novel nurse-led one-stop clinic for patients with suspected non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Frontline Gastroenterol 2021;12:102–7. 10.1136/flgastro-2019-101304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bellentani S. The epidemiology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int 2017;37 Suppl 1:81–4. 10.1111/liv.13299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nusrat S, Khan MS, Fazili J, et al. Cirrhosis and its complications: evidence based treatment. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:5442–60. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Anderson P, O'Donnell A, Kaner E, et al. Impact of minimum unit pricing on alcohol purchases in Scotland and Wales: controlled interrupted time series analyses. Lancet Public Health 2021;6:e557–65. 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00052-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]