Abstract

Background:

Retinoblastoma (RB) is the most common primary intraocular malignancy of childhood. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the orbit and brain is the preferred imaging modality to diagnose and define extent of disease as well as to assess response to therapy. Sometimes, it may be difficult to differentiate the presence of active residual disease from therapy-related changes based on posttreatment completion MRI.

Materials and Methods:

RB patients who completed treatment between January 2017 and October 2019 were retrospectively analyzed. We evaluated the utility of F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) to predict active disease in RB patients who continued to have residual disease on MRI at completion of treatment.

Results:

Out of the 89 patients who completed treatment, dilemma regarding remission status was present in 11 children. All 11 patients underwent FDG-PET-CT. None of them had evidence of metabolically active disease in the orbit, optic nerve, brain, or rest of the body. After a median follow-up of 24 months, no children developed any evidence of disease progression in the form of local or distant relapse.

Conclusion:

Our results showed that in MRI doubtful cases, a nonavid FDG-PET is reassuring in avoiding further therapy as long as close follow-up can be ensured. FDG-PET-CT may emerge as a useful functional modality to predict disease activity in RB.

Keywords: Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, residual disease, retinoblastoma

Introduction

Retinoblastoma (RB) is the most common primary intraocular malignancy of childhood with an average incidence of approximately 11 new cases per million population <5 years of age.[1] The survival in developed countries almost approaches 100% due to understanding of genetic basis of disease, proper screening programs, and early referral. In low-middle-income countries which contribute to major proportion of RB cases, the prognosis is still poor mainly due to delay in presentation. Extraocular presentation of RB and distant metastasis at diagnosis was found in 21.5% and 19% of patients in low-income countries compared to only 1.5% and 0.3% in high-income countries, respectively.[2] The data from our center also showed extraocular disease and central nervous system metastasis in 27% and 15%, respectively.[3] Treatment and prognosis of extraocular disease depends on stage of disease. Standard modalities to diagnose and define extent of disease include examination under anesthesia (EUA with fundoscopy and ultrasound) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of orbit and brain. RB requires multimodality management strategies with chemotherapy being the cornerstone and radiation therapy and surgery depending on the extent of disease. MRI remains the preferred modality for diagnosis and response assessment. Potential pitfalls of MRI include difficulties in the evaluation for distant metastasis, posttreatment recurrence, such as postoperative changes/scars, artefacts from prostheses, metallic hardware, and atrophy of the optic nerve on the side of globectomy.[4] Frequently, based on posttreatment completion MRI, radiologists find it hard to differentiate the presence of active residual disease from therapy-related changes, more so in case of extraocular disease. There is a need for functional imaging modality like positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT), which may be of benefit to overcome these limitations.

Data on the role of fluorodeoxyglucose PET (FGD-PET) in diagnosing, staging, and monitoring treatment response are very limited in case of RB. There are no studies describing the utility of PET-CT in cases of doubtful residual disease on MRI done at treatment completion. With this background, we retrospectively evaluated the utility of PET-CT to predict active disease in those RB patients who continued to have residual disease on MRI at completion of treatment.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective analysis of all RB patients who had completed treatment between 2017 and 2019 was done. Demographic details were obtained and review of clinical and treatment details was done. EUA with fundoscopy and ultrasonography (USG) and contrast-enhanced MRI orbit and brain was done in all patients. In addition, extraocular disease patients underwent metastatic workup in the form of bilateral bone marrow aspiration and biopsy, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, and bone scan. Intraocular disease patients received either focal therapy alone or focal therapy in combination with systemic chemotherapy (vincristine, carboplatin, and etoposide) depending on disease group as defined by the International Classification for the Intraocular Retinoblastoma.[5] (Patients with intraocular disease requiring enucleation with no high-risk histopathological features were not referred to us). Response was monitored by the EUA after every 2 cycles for intraocular disease. Extraocular disease patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (vincristine, carboplatin, and etoposide every 3-4 weekly) followed by response assessment by MRI after 3 cycles. Subsequently, these patients underwent enucleation of the affected eye if tumor was amenable to surgery (else chemotherapy was escalated) followed by external beam radiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy for a total of 12 cycles. As per the institutional protocol, MRI was obtained in all patients at the end of treatment to document complete remission and their eligibility to after treatment care and survivorship program. If posttreatment MRI was suspicious of residual disease (optic nerve stump residual enhancement/hyperintensity which cannot be differentiated from post operative changes in case of EORB or residual mass lesion in case of intraocular disease), PET-CT was done in these subgroup of patients to look for disease activity.

F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography–computed tomography imaging and analysis

Whole-body PET-CT was performed after completion of therapy. Each patient was injected 0.15-0.30 mCi/kg (5-10 MBq/kg) of F-18 FDG, with a minimum dose of 1 mCi (37 MBq) intravenously in euglycemic state. Images were acquired on a dedicated PET-CT scanner (Biograph mCT, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) beginning 60 min after F-18 FDG injection. An initial scout was followed by noncontrast CT from head to mid-thigh. After CT scan, 3D PET acquisition was taken for 2 min per bed position. PET data were acquired using matrix of 128 × 128 pixels with a slice thickness of 1.5 mm. CT-based attenuation correction of the emission images was employed. PET images were reconstructed by iterative method ordered subset expectation maximization (OSEM; 2 iterations and 8 subsets).

The PET-CT scans were reviewed by qualified nuclear medicine specialist who had more than 10 years of experience in reading PET-CT, to look for abnormal FDG uptake in the orbit (other than the intense physiological uptake in the extraocular muscles), along the optic nerve, brain, or elsewhere in the body. Increased focal FDG uptake at the sites of hyperintensities or residual enhancement of cut end of optic nerve on MRI more than the background FDG uptake in ipsilateral temporalis muscle is considered positive for residual disease.

Results

Total number of patients who completed treatment as per the institutional protocol and enrolled in after treatment completion clinic during the time period (January 2017 to October 2019) were included in the study. The median age was 20 months, interquartile range (IQR) of 26 (10–36), and a male-to-female ratio of 1.6:1. Total number of involved eyes were one hundred and eighteen. Bilateral disease was found in 29 patients. Intraocular disease was noted in 96 eyes and extraocular extension in 22 eyes. Posttreatment completion, MRI was done in all RB patients within 3 months of treatment completion.

Dilemma regarding remission status on MRI was found in 11 patients. The median age was 18 months (IQR: 8–24). Six patients had intraocular and five had extraocular disease. All patients with extraocular disease had thickening/enhancement of variable lengths of optic nerve at baseline. Eight out of eleven patients underwent enucleation (3 for group E intraocular and 5 for extraocular disease). Cut end of optic nerve was free of tumor in all of these 8 children. The median delay in radiotherapy for extraocular RB patients after enucleation was 1.5 months. The most common MRI abnormalities were hyperintensities or residual enhancement of cut end of optic nerve in case of enucleated eye. All 11 patients underwent FDG PET-CT (within one month of MRI). None of the 11 patients had evidence of metabolically active disease in the orbit, optic nerve, brain, or rest of the body [Figures 1 and 2]. All the 11 patients were kept on close follow-up and none of them received any additional form of therapy based on PET-CT report. After a median follow-up of 24 months, none of the children developed any evidence of disease progression in the form of local or distant relapse during the time of last follow-up [Table 1].

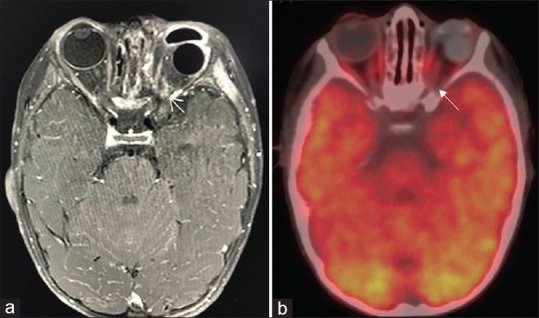

Figure 1.

Axial postcontrast fat suppressed T1 weighted magnetic resonance imaging showing enhancement at left optic nerve stump (a, arrow), 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography, fused positron emission tomography-computed tomography axial section at the same level shows no abnormal fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the areas of enhancement seen on post contrast magnetic resonance imaging images (b, arrow) and normal physiological uptake of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose seen in the extraocular muscles, cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres

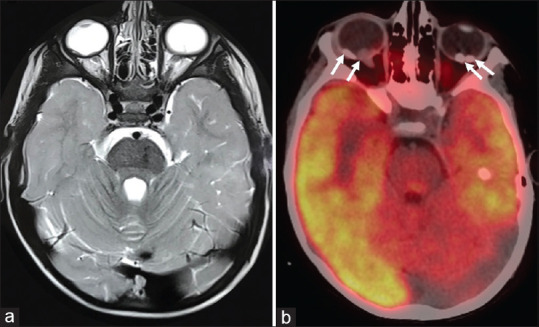

Figure 2.

Axial T2 weighted magnetic resonance imaging showing two intraocular plaques like thickening involving posterior part of right globe and similar T2 hypointense lesion in the posterior part of left globe (a), 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography at the same level shows calcified lesions with no abnormal fluorodeoxyglucose uptake (b)

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and imaging findings

| Diagnosis and stage (IRSS) | Age at diagnosis (months) | Details of therapy | Post treatment MRI | PET-CT | Follow up (months) | Disease Status | HPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right Group E IORB Left Group C IORB Stage 1 |

4 | CT (8 cycles) Enucleation right eye (post 5 cycles) |

Significant edema surrounding the SR and SO muscle | A small hyperdense focus is noted in left eye with no FDG uptake | 20 | Remission | Ciliary body infiltrated Cut end free |

| Right Group C multifocal IORB Left Group E IORB Stage 1 |

18 | CT (12 cycles) Enucleation left eye (post 1 cycle) |

Right regressed plaque, left ON tip enhancement | Focal FDG uptake at insertion of inferior oblique, likely physiological | 20 | Remission | No HRF, cut end free |

| Right multifocal Group B IORB Left Group D IORB Stage 0 |

8 | CT (12 cycles) | Partially calcified endophytic lesion in left eye globe with RD. Doubtful residual mass | No metabolically active residual lesion in left eye | 27 | Remission | NA |

| Right Group C multifocal IORB Left Group C IORB Stage 0 |

18 | CT (15 cycles) IAM |

Hypointense endophytic lesion in right lateral aspect and ON head of right globe. Small lesion left globe | Non FDG avid soft tissue thickening in posterior segment of right eye and calcified plaques in B/L eyes | 18 | Remission | NA |

| Right Group D IORB Left Group E IORB Stage 0 |

13 | CT (9 cycles) | Residual partially calcified endophytic lesion in B/L globe | No metabolically active lesion | 25 | Remission | NA |

| Left Group E IORB Stage 1 |

18 | CT (12 cycles) Enucleation (Post 2 cycles) |

Left intraorbital part of ON shows 3 mm enhancement | No metabolically active lesion | 24 | Remission | No HRF, Cut end free |

| Left EORB Stage 3 |

2 | CT (12 cycles) Enucleation (Post 6 cycles) EBRT (6 months after enucleation) |

Post-OP changes in left eye | No FDG avid thickening/mass in post-operative site | 11 | Remission | Cut end free |

| Right group B IORB Left EORB Stage 3 |

9 | CT (12 cycles) Enucleation (Post 3 cycles) EBRT (1 month after enucleation) |

Hyperintensity of left ON stump | No FDG avid thickening/mass in postoperative site | 34 | Remission | Cut end free |

| Left EORB (trans-scleral extension) Stage 3 |

26 | CT (12 cycles) Enucleation (post 3 cycles) |

ON sheath enhancement present on canalicular part | No metabolically active residual lesion in left eye | 15 | Remission | Cut end free |

| Left EORB Stage 3 |

24 | CT (12 cycles) Enucleation (post 7 cycles) EBRT (2 months after enucleation) |

Doubtful lesion left ON resected margin | No FDG avid lesion | 26 | Remission | Cut end free |

| Left EORB Stage 3 |

36 | CT (12 cycles) Enucleation (post 3 cycles) EBRT (1 month after enucleation) |

Left ocular prosthesis. Left ON stump enhancement seen | No metabolically active lesion | 24 | Remission | Cut end free |

IRSS: International Retinoblastoma Staging System, HPE: Histopathological examination, HRF: High risk features, IORB: Intraocular retinoblastoma, EORB: Extraocular retinoblastoma, CT: Chemotherapy, EBRT: External beam radiotherapy, SO: Superior oblique, SR: Superior rectus, IAM: Intra-arterial melphalan, ON: Optic nerve, RD: Retinal detachment, NA: Not applicable, MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging, CT: Computed tomography, PET: Positron emission tomography, FDG: Fluorodeoxyglucose

Discussion

USG, CT, and MRI are the primary modalities used for imaging of head and neck tumors in children. In case of RB, histologically proven calcification is found in up to 95% of cases and this feature is utilized to differentiate it from other ocular mass lesions in childhood.[6] Examination under general anesthesia with fundoscopy and USG almost always provides the diagnosis of RB. USG detects calcifications in 92%–95% of cases, but it is not useful to evaluate extent of disease. CT is the best imaging modality for the detection of intraocular calcifications, but the sensitivity of CT in detection of optic nerve invasion is very low. There are also concerns about radiation exposure in children. As USG detects foci of calcification in almost all RBs, there is no added advantage of performing routine CT for detection of calcifications in suspected RB. MRI is the most sensitive technique for the evaluation of tumor infiltration of the optic nerve, extraocular extension, and intracranial disease as well as to rule out an associated pinealoblastoma.[7] At our center, MRI brain and orbit and not CECT is done for all patients of RB.

FDG-PET CT is a recently emerging diagnostic tool in ophthalmologic oncology. It makes use of the increased glucose demand of tumor cells and provides functional information regarding tumor metabolism based on FDG uptake. The utility of FDG PET-CT in pediatric patients with intraocular tumors is still not widely established. For majority of the primary orbital tumors, FDG-PET does not help in providing any significant advantage over CT/MRI, other than detecting distant and metastatic lesions missed by conventional imaging. As of current literature, FDG-PET-CT does not provide any added value in baseline staging of RB, except in locally advanced extraocular disease for the detection of metastasis. MRI remains the gold standard investigation for diagnosis and staging of pediatric RBs.

In adults, FDG-PET was found to be suitable in the diagnosis of large- and medium-sized uveal melanoma, initial staging workup and posttreatment assessment of orbital/ocular adnexal lymphomas, detection of metastatic tumors to the orbit and ocular adnexae from other primary sites and allows whole-body scan for detection of metastatic lesions.[8,9] Potential drawbacks of FDG-PET CT imaging of the orbit include background physiological uptake in extraocular muscles and poor uptake in very small lesions.[10] Other disadvantages include high cost, low detection rate in tumor with low metabolic rate, and the use of radiopharmaceuticals increases the risk of secondary cancer. Radhakrishnan et al. in a prospective study found that increased optic nerve uptake on baseline PET CT may be a predictor of lower event-free survival and lower overall survival as compared to patients without optic nerve FDG uptake.[11] In another study, Moll et al. found that in newly diagnosed RB patients, FDG PET showed uptake, but it varied widely from mild activity to high tracer uptake. Scan did not yield useful information in the assessment of possible vital tumor tissue in the scars in the eye.[12]

Our results showed that in all 11 patients who had MRI evidence of doubtful residual disease, FDG-PET CT failed to show any metabolic activity. After a median follow-up of 24 months, none of them had recurrence of disease. Among the 6 cases of intraocular RB, 4 had residual optic nerve enhancement on MRI, which was interpreted as disease recurrence (3 had underwent enucleation and none of them had received radiotherapy), was not appreciated in PET-CT. The other 2 patients with residual intraocular mass lesion were also FDG nonavid. Although literature suggest that intraocular RB may not be FDG avid, this analysis highlights that a negative FDG-PET may be reassuring in avoiding further therapy in case of doubtful residual disease on MRI as no patient in our cohort relapsed. Frequently, many of these imaging findings represent therapy-related changes due to surgery or radiotherapy rather than active disease. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have looked into the utility of FDG-PET in identifying active disease posttreatment completion in MRI doubtful cases. Our analysis is limited by retrospective nature and small number of intervened patients. Furthermore, none of them had underwent a baseline PET to compare if the lesion was FDG avid at the onset. Added value into this issue can be obtained by doing a study for extraocular patients who undergo initial PET at diagnosis and then see the response at the end of therapy. Nonetheless, negative FDG-PET was definitely reassuring in avoiding unnecessary toxic therapy in these patients. Further prospective studies are needed to arrive at a definite conclusion about the role of FDG-PET CT to characterize RB.

Conclusion

The present study retrospectively evaluated the role of PET-CT in RB posttreatment completion. In MRI doubtful cases, a nonavid FDG-PET is reassuring in avoiding further therapy. Close follow-up of these patients has not shown any evidence of local or distant recurrence. Changes seen in MRI may have been due to postoperative or radiotherapy related. FDG-PET-CT may emerge as a useful functional modality to predict disease activity in RB.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Devesa SS. The incidence of retinoblastoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;80:263–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(75)90143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global Retinoblastoma Study Group. Fabian ID, Abdallah E, Abdullahi SU, Abdulqader RA, Adamou Boubacar S, et al. Global retinoblastoma presentation and analysis by National income level. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:685–95. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.6716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chawla B, Hasan F, Azad R, Seth R, Upadhyay AD, Pathy S, et al. Clinical presentation and survival of retinoblastoma in Indian children. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100:172–8. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-306672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Razek AA, Elkhamary S. MRI of retinoblastoma. Br J Radiol. 2011;84:775–84. doi: 10.1259/bjr/32022497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linn Murphree A. Intraocular retinoblastoma: The case for a new group classification. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2005;18:41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ohc.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galluzzi P, Hadjistilianou T, Cerase A, De Francesco S, Toti P, Venturi C. Is CT still useful in the study protocol of retinoblastoma? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:1760–5. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Graaf P, Göricke S, Rodjan F, Galluzzi P, Maeder P, Castelijns JA, et al. Guidelines for imaging retinoblastoma: Imaging principles and MRI standardization. Pediatr Radiol. 2012;42:2–14. doi: 10.1007/s00247-011-2201-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neupane R, Gaudana R, Boddu SH. Imaging techniques in the diagnosis and management of ocular tumors: Prospects and challenges. AAPS J. 2018;20:97. doi: 10.1208/s12248-018-0259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Purohit BS, Vargas MI, Ailianou A, Merlini L, Poletti PA, Platon A, et al. Orbital tumours and tumour-like lesions: Exploring the armamentarium of multiparametric imaging. Insights Imaging. 2016;7:43–68. doi: 10.1007/s13244-015-0443-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Purohit BS, Ailianou A, Dulguerov N, Becker CD, Ratib O, Becker M. FDG-PET/CT pitfalls in oncological head and neck imaging. Insights Imaging. 2014;5:585–602. doi: 10.1007/s13244-014-0349-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radhakrishnan V, Kumar R, Malhotra A, Bakhshi S. Role of PET/CT in staging and evaluation of treatment response after 3 cycles of chemotherapy in locally advanced retinoblastoma: A prospective study. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:191–8. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.095836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moll AC, Hoekstra OS, Imhof SM, Comans EF, Schouten-van Meeteren AY, van der Valk P, et al. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET) to detect vital retinoblastoma in the eye: Preliminary experience. Ophthalmic Genet. 2004;25:31–5. doi: 10.1076/opge.25.1.31.29001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]