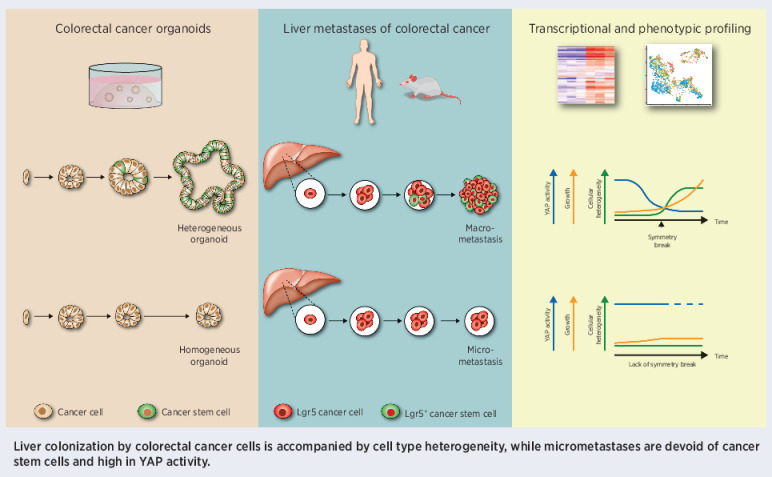

Characterization of the cell type dynamics, composition, and transcriptome of early colorectal cancer liver metastases reveals that failure to establish cellular heterogeneity through YAP-controlled epithelial self-organization prohibits the outgrowth of micrometastases.

Abstract

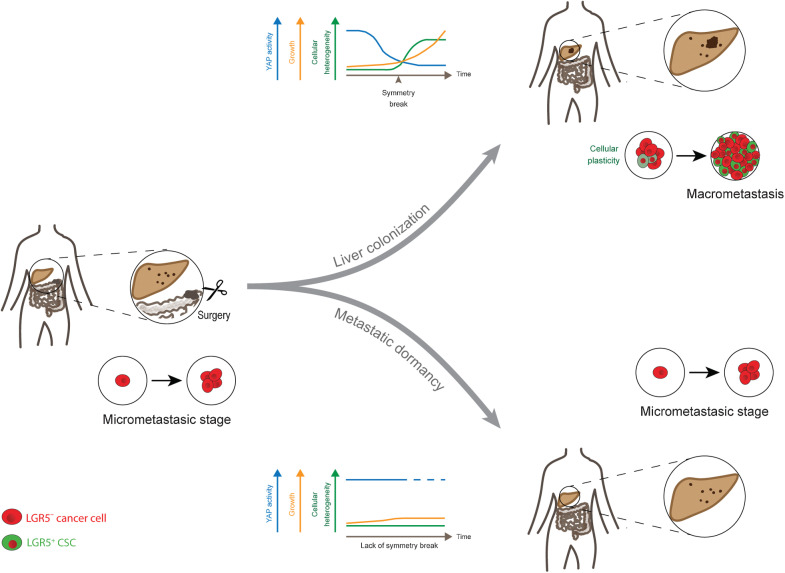

Micrometastases of colorectal cancer can remain dormant for years prior to the formation of actively growing, clinically detectable lesions (i.e., colonization). A better understanding of this step in the metastatic cascade could help improve metastasis prevention and treatment. Here we analyzed liver specimens of patients with colorectal cancer and monitored real-time metastasis formation in mouse livers using intravital microscopy to reveal that micrometastatic lesions are devoid of cancer stem cells (CSC). However, lesions that grow into overt metastases demonstrated appearance of de novo CSCs through cellular plasticity at a multicellular stage. Clonal outgrowth of patient-derived colorectal cancer organoids phenocopied the cellular and transcriptomic changes observed during in vivo metastasis formation. First, formation of mature CSCs occurred at a multicellular stage and promoted growth. Conversely, failure of immature CSCs to generate more differentiated cells arrested growth, implying that cellular heterogeneity is required for continuous growth. Second, early-stage YAP activity was required for the survival of organoid-forming cells. However, subsequent attenuation of early-stage YAP activity was essential to allow for the formation of cell type heterogeneity, while persistent YAP signaling locked micro-organoids in a cellularly homogenous and growth-stalled state. Analysis of metastasis formation in mouse livers using single-cell RNA sequencing confirmed the transient presence of early-stage YAP activity, followed by emergence of CSC and non-CSC phenotypes, irrespective of the initial phenotype of the metastatic cell of origin. Thus, establishment of cellular heterogeneity after an initial YAP-controlled outgrowth phase marks the transition to continuously growing macrometastases.

Significance:

Characterization of the cell type dynamics, composition, and transcriptome of early colorectal cancer liver metastases reveals that failure to establish cellular heterogeneity through YAP-controlled epithelial self-organization prohibits the outgrowth of micrometastases.

See related commentary by LeBleu, p. 1870

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Epithelial tissue turnover is fueled by a small pool of self-renewing stem cells (SC) that give rise to a large population of differentiated cells. Colorectal cancers comprise similar cell populations to the healthy intestine, including cell types reminiscent of cycling SCs as well as differentiated cells (1–4). Furthermore, the cellular hierarchy observed in normal epithelium is vastly maintained in tumors where so-called cancer stem cells (CSC), marked by Lgr5, constitute a self-renewing population that fuels cancer growth by generating all epithelial cell types present in colorectal cancers (3, 5). Both in intestinal homeostasis and cancers, genetic lineage tracing experiments have revealed a high degree of plasticity where more differentiated cells regain SC potential often triggered by external cues (6).

The main cause of colorectal cancer–related mortality is metastatic spread to distant organs such as the liver and lungs. Metastases exhibit cellular heterogeneity resembling the tissue of origin (7). Similarly to primary colorectal cancers, Lgr5+ CSCs are indispensable for metastatic growth and maintenance in murine models (5, 8). Considering the central role of CSCs within the cellular organisation of tumors and metastases, it has been a long-held belief that colorectal cancer metastases are seeded by CSCs. However, using mouse models it was recently demonstrated that the vast majority of disseminating colorectal cancer tumor cells are Lgr5–, while Lgr5+ CSCs reappear at the distant site (8).

Metastatic colonization, that is the successful outgrowth of a (dormant) micrometastasis into an actively growing overt lesion, is a rate-limiting step in the metastatic cascade (9, 10). Illustrative of this is the phenomenon of metastatic latency in patients with colorectal cancer. Micrometastases can remain dormant and undetected in the liver for years after surgical removal of the primary tumor, eventually regaining proliferative behavior and resulting in overt metastases (11). Yet, their small size and inactive nature make micrometastases difficult to detect and study. As a result, it remains elusive as to how a single metastasizing cell grows out into a heterogeneous cell mass and which features are critical for its success (7). Although the microenvironment has been previously implicated in population dormancy (12, 13), the epithelial side underlying cellular dormancy is poorly understood.

Adult SC-derived organoids have emerged as a tool to study both normal and cancerous tissue physiology (14, 15). In particular, their genetic tractability and accessibility allow detailed studies on cellular differentiation trajectories in human and mouse intestinal tissue (16–18) and permit detailed insights into the intrinsic nature of epithelial self-organization.

In this study, we are using a combination of patient biopsies, functional patient-derived xenografts (PDX) and mouse models of colorectal cancer to study plasticity at different stages of in vivo metastasis formation in the liver. We demonstrate a close resemblance in cellular organization and patterning between liver metastasis formation in vivo and clonal outgrowth of patient-derived colorectal cancer organoids (PDO). Through detailed imaging and transcriptomic analysis, our organoid and in vivo data reveal that epithelial self-organization involving attenuation of high levels of YAP activity followed by the formation of cell type heterogeneity is required to transition from the micrometastasic stage to overt liver colonization.

Materials and Methods

Human colorectal cancer liver metastases

The collection and processing of human tissue from residual material of liver resection specimens was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Biobank Research Ethics Committee (TCBio; protocol 16–651) of the University Medical Center Utrecht (Utrecht, the Netherlands). This tissue is classified as “residual material” and the collection and processing of this biological material is in accordance with the “no objection” procedure defining the release of anonymized residual material without broad consent under strict conditions and approval under aforementioned Research Ethics Committee.

Liver tissue strips from patients with colorectal cancer (Supplementary Table S1) measuring 5–10 cm × 2 cm and extending from a macrometastasis into healthy peripheral liver tissue were formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) and consecutively cut. When no macrometastasis was available for diagnostic reasons, a liver tissue strip was obtained from a part of the liver unrelated to a macrometastasis.

IHC

FFPE sections were deparaffinized in xylene (Klinipath) and subsequently rehydrated in a graded alcohol series (100% ethanol to 70% ethanol). For patient liver tissue sections, epitope retrieval was performed by cooking the slides for 20 minutes in citrate buffer (Alfa Aesar, pH 6.0), followed by blocking of endogenous peroxidase in 1.5% H2O2 in PBS, and antibody incubation. Subsequently, slides were developed with diaminobenzidine (Fluka) followed by hematoxylin counterstaining, air-dried, and mounted on coverslips. For tyramide multiplex IHC, epitope retrieval was carried out in 10 mmol/L sodium citrate (pH 6.0) or 1 mmol/L EDTA (pH 9.0) depending on the antibody. Endogenous peroxidase was inactivated and sections were blocked in 10% normal goat serum prior to antibody incubation. Sections were developed using Alexa Fluor–conjugated tyramides. Same species antibodies were applied after 10 minutes of heat-mediated stripping of the antibody complex in 10 mmol/L sodium citrate (pH 6.0) buffer. Slides were counterstained with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich, 600×).

Antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C (details listed in Supplementary Table S2) and poly-horseradish peroxidase antibodies were used in both cases for signal amplification. Automated stainings were performed for CDX2 and EPCAM using the Ventana Bench Ultra at the department of pathology at the University Medical Center Utrecht (Utrecht, the Netherlands).

For identified metastases, the correlation between metastatic size (micro or macro) and SC marker expression (absent or heterogeneous) was assessed using a Fisher exact test.

Mouse experiments

All mouse experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Commitees of our institutions: the Animal Welfare Committees of the Animal Welfare Body Utrecht, the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the Netherlands Cancer Institute. Animals were kept at animal facilities of the Central Laboratory Animal Research Facility (Gemeenschappelijk Dierenlaboratorium, GDL), the Hubrecht Institute or the Netherlands Cancer Institute.

For transplantation experiments, 8–14-week-old male and/or female NOD.Cg-PrkdcSCID Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ mice, obtained from Charles River (NSG, Charles River strain code 614) or The Jackson Laboratory (NSG, The Jackson Laboratory, catalog no. 005557) were used as acceptors.

Orthotopic transplantation of colorectal cancer organoids

Orthotopic transplantation of PDOs was performed as previously described (19). Mice were sedated and type I collagen blobs (Corning, catalog no. 354249) containing approximately 250,000 and 150,000 cells for the murine and human colorectal cancer model, respectively, were transplanted into the cecal subserosa of recipient mice.

Murine livers of 15 mice were analyzed for the presence of human metastases after 3 weeks (3 mice, 1 micrometastasis) or 9–12 weeks (12 mice, all but 1 metastasis).

Mesenteric or portal vein injection of murine colorectal cancer cells

Lgr5+ and Lgr5– cells were collected by FACS and injected in 100 µL PBS into recipient mice. For intravital microscopy (IVM) experiments, 10,000 Lgr5– cells were collected from murine colorectal cancers grown for 7–10 weeks upon orthotopic transplantation and injected into the mesenteric vein (8, 20). For the single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) experiment, Lgr5+ and Lgr5– subpopulations were isolated from colorectal cancer organoids. Approximately, 400k, 200k, 200k, and 50k cells were injected into the portal vein and harvested after 1, 7, 13, and 27 days, respectively.

Intravital imaging on liver metastases

An abdominal imaging window was applied onto the liver of sedated mice and daily tracking of metastases through IVM was performed as previously described (8, 21, 22).

Collagenase liver perfusion

For the isolation of colorectal cancer cells, a two-step liver perfusion protocol was adopted and modified (23). In brief, the portal vein or subhepatic vena cava was cannulated with a 24G IV catheter (BD Insyte Autoguard Shielded IV catheter; BD 381412) to perfuse first, 70 mL HBSS (Gibco) with 0.5 mmol/L EGTA, 25 mmol/L HEPES, and NaOH to reach a pH of 7.4 at 37°C. Next, 80 mL digestion medium consisting of DMEM-low glucose (Corning) with 15 mmol/L HEPES, Penicillin–Streptomycin, collagenase type IV (Gibco) in sufficient quantity for 120 Collagenase Digestive Units (CDU)/mL at 37°C) was perfused.

The liver was excised, minced in a 15-cm petri dish with 10 mL digestion medium, resuspended in 25 mL isolation medium (DMEM-High/F-12, Gibco with 10% FBS), and filtered through a 70-µm strainer. The supernatant of two initial washing steps (centrifugation at 50 × g for 2 minutes) was washed twice more with 25 mL isolation medium (centrifugation at 500 × g for 3 minutes). Then, DRAQ7 (Cell Signaling Technology) was added and single, alive, RFP+ cells were FACS-sorted into 384-well collection plates for scRNA-seq.

Organoid cultures

Organoid lines were maintained in Matrigel (Corning) as previously described (24, 25). Culture medium was adapted per line depending on the presence of oncogenic mutations that render growth factors obsolete: Loss of APC, SMAD4, and oncogenic KRASG12D were attributed by leaving out R-Spondin, Noggin, and EGF, respectively. For details on the lines, see supplementaries.

For experiments, single cells were plated at a density of 250–1,000 cells/µL Matrigel. Perturbation studies were performed using doxycycline (Bio-Connect), verteporfin (Bio-Techne), XMU-MP-1 (Sigma) at indicated concentrations with corresponding DMSO controls (VWR).

Flow analysis of organoids

Viability readouts were performed upon addition of DAPI (Sigma) 30 minutes prior to the sort. STAR gates were defined as STARhi (top 15%), STARlo (bottom 15%), and STARmid (remaining 70%) based on the DMSO sample using FlowJo 10.6.1 (https://www.flowjo.com). EdU incorporation assays were performed after fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature. Significance levels were assessed by two-tailed Student t tests compared with DMSO control.

Organoid tracking experiment

STARhi and STAR− cells were collected by FACS from 2-week-old organoids and plated onto 384-well imaging plates (Corning). Organoid size per phenotype (homogeneous and heterogeneous) was compared using a two-tailed Student t test. For the organoid growth rate r, a proliferation model with uniform growth of all cells over time was assumed: N(t) = N0 × exp(r × t), with number of cells per organoid N and time in days t. Paired organoid data of day 6 (N0) and day 10–11 (N(t)) were used for the analysis.

Size filtering of organoids

Organoids were harvested with 1 mg/mL Dispase II (Life Technologies), and pelleted by gentle spinning at 300 × g, 4 minutes, 4°C. The organoid suspension was first applied onto a 100-µm strainer (VWR), while organoids passing the filter were collected in a 50 mL falcon tube. Organoids trapped in the filter (>100 µm) were isolated using 10 mL of Advanced DMEM/F12, pelleted and kept on ice. Next, to collect organoids of 40–70 µm in diameter, the flow-through of the 100-µm strainer was subjected first to a 70-µm strainer (VWR) and subsequently to a 40-µm strainer (VWR). Organoids trapped in the 40-µm strainer were washed out with 10 mL of Advanced DMEM/F12, pelleted, and kept on ice until processed further.

Organoid staining

Antibody staining was performed as previously described (26). Briefly, 10- to 14-day-old organoids were fixed in 4% PFA, incubated in PBT (PBS with 0.1% Tween 20), and blocked with OWB (0.1% Triton X100 and 0.2% BSA). Antibodies (Supplementary Table S2) were incubated overnight at 4°C. Organoids were imaged in clearing agent (60% glycerol and 2.5 mol/L fructose).

CellTiter-Glo

Organoids were grown in white-walled 96-well tissue culture plates (Merck). For analysis, 50% v/v CellTiter-Glo reagent (Promega) was added to each well. The plate was shaken rigorously for 30 minutes and afterwards analyzed using a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices). Background levels (average of cell-free wells) were subtracted and data was normalized to the respective DMSO control.

EdU incorporation assay

EdU incorporation assays were performed after adding 500 nmol/L EdU for 16 hours to cells and processed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Click-iT EdU Cell Proliferation Kit for Imaging, Thermo Fisher).

qRT-PCR analysis

Samples frozen in 350 µL RLT buffer were processed using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions including DNAseI treatment (Qiagen). cDNA was reverse transcribed (iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit, Bio-Rad) with 1 µg RNA input. 4 µL of cDNA input (diluted to 220 total volume) was mixed with 5 µL FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.5 µmol/L forward and reverse primer each (Supplementary Table S3). Gene expression was normalized to the mean of the housekeeping genes ACTB (forward: CATTCCAAATATGAGATGCGTTGT; reverse: TGTGGACTTGGGAGAGGACT) and B2M (forward: GAGGCTATCCAGCGTACTCCA; reverse: CGGCAGGCATACTCATCTTTT). Data is represented as mean + SEM.

Bulk RNA-seq sample preparation

Twelve-day-old organoids, grown from single STAR+ cells, were size filtered as described above. Subcultures were trypsinized and STARhi, STARmid, and STAR− cells were collected by FACS in technical duplicates or triplicates (10–20k cells each), then snap-frozen.

RNA-seq libraries were prepared as described previously (15) with the following adaptations: Up to 73 ng RNA was used as input material. The library was amplified in 13 cycles and subsequent clean-up was performed using a 0.8x bead-based clean-up. Sequencing was performed using an Illumina NextSeq500 with 50-bp paired-end reads.

Bulk RNA-seq analysis

Sequencing reads mapped to the pre-indexed hg38 genome assembly. Differential gene expression analysis was performed with the DESeq2 package (27). Genes with no reads mapped in any of the samples were filtered prior to differential gene expression (DGE) analysis (Wald test with Benjamini–Hochberg correction). For investigations on STAR dynamics (Supplementary Fig. S4B), equal numbers of replicates (n = 2) of each biological condition were used and significantly changing genes were identified with a likelihood-ratio test.

The YAP activity score is based on Yap perturbation studies in mice (28). It is computed as mean of two expression level fold changes: Yap knockout/control and the inverse of Yap overexpression/control. Genes that were not picked up reliably in both studies were not assigned a YAP score.

Gene-set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed using the fgsea R package (29) of an intestinal SC signature (30), fetal and repair gene signature (31), and LCC signature (13).

Micro-organoid–related genes were extracted on the basis of their high YAP score and/or a high fold change in expression between micro- and macro-organoids (see Supplementary Methods; Supplementary Table S3).

scRNA-seq

scRNA-seq was performed according to the Sort-seq protocol (32). Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq500 at paired-end 60- and 26-bp read length and 75,000 reads per cell.

scRNA-seq data analysis

Reads were mapped to the mm10 genome assembly including the DTR-eGFP and tDimer2 reporter transcripts. Analysis was performed with the R-package Seurat (version 4.0.4; ref. 33). Cells with >200 unique transcripts and <10% mitochondrial reads were included into the analysis. Gene signature expression levels were computed using the AddModuleScore function (ctrl = 5) for the following gene sets: YAP signature (28) and fetal signature (ref. 34; as previously extracted, ref. 35); CSC and non-CSC signatures (8) extracted upon differential gene expression of Lgr5+ and Lgr5– cells located in primary or metastatic tumors.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (software version 6) unless specified otherwise. Results with P values smaller than 0.05 were considered statistically significant (*). P values smaller than 0.01 and 0.001 are indicated by (**) and (***), respectively.

Data and code availability

The sc- and bulk RNA-seq data generated in this study are publicly available in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) at GSE189987 and GSE193248, respectively.

Results

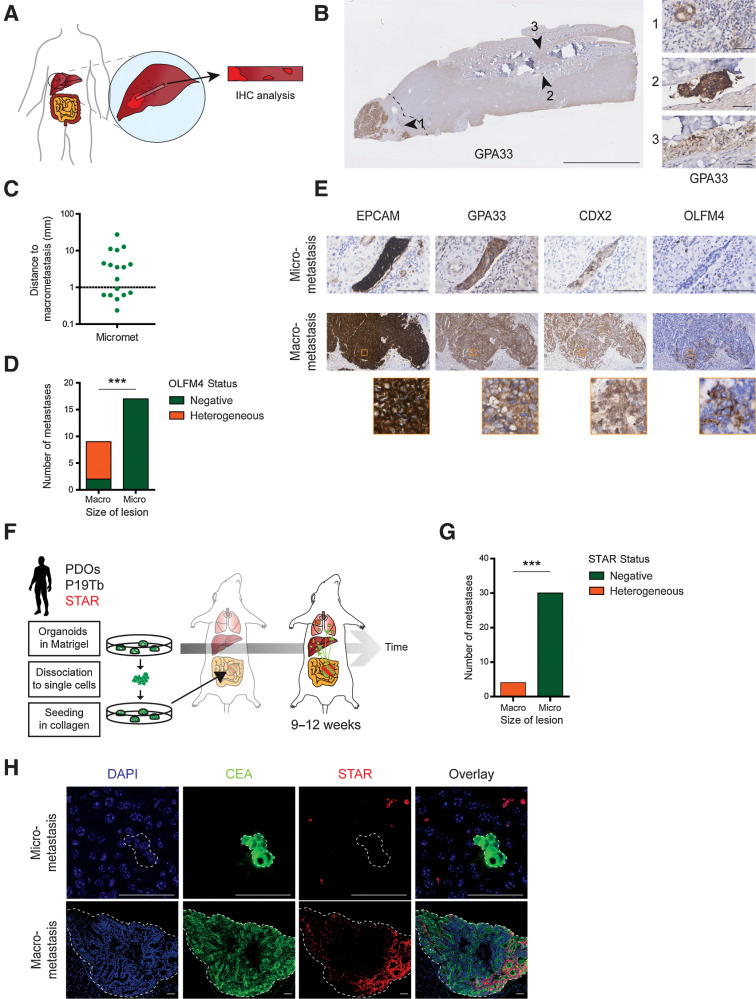

Liver micrometastases of human colorectal cancers are devoid of classical SC markers

Recent data suggests that metastatic growth requires CSCs (5, 8). Yet, examining the presence of CSCs in patient micrometastases is challenging due to their small size and sporadic appearance. Therefore, we collected liver tissue strips of patients undergoing surgical removal of colorectal cancer liver metastases (Supplementary Table S1), which start at the clinically detectable metastatic lesion and extend 5–10 cm into the adjacent liver tissue (Fig. 1A and B). Using IHC against three colonic markers (EPCAM, GPA33, and CDX2, Supplementary Table S2), we could faithfully identify 17 micrometastatic lesions in 18 patients. (Fig. 1B; Supplementary Fig. S1A–S1H).

Figure 1.

Liver micrometastases of human colorectal cancers are devoid of classical SC markers. A, Graphical representation of liver tissue strips extending from macrometastases into adjacent liver tissue. B, Liver tissue strip stained for GPA33 to identify macro- and micrometastases (arrowheads). Dashed line, 1 mm distance to macrometastasis. Scale bar, 5 mm (50 µm in close-ups). C, Distance of identified micrometastases to their respective macrometastasis. Each dot represents one lesion. D, Bar graph summarizing OLFM4 expression patterns in all macro- and micrometastases as either completely absent (green) or heterogeneous (orange). E, Representative IHC stainings of a macro- and micrometastasis of the same patient. Macrometastasis shows heterogeneous OLFM4 expression. Close-ups, orange boxes. Scale bars, 100 µm. F, Experimental setup for spontaneous metastasis formation in mice using orthotopic transplantation of human colorectal cancer PDOs with analysis after 9–12 weeks. G, Bar graph depicting the presence of STAR+ CSCs in liver macro- or micrometastases, identified and classified (size) through IHC against human CEA. H, Representative images related to G. STAR minigene is unique to xenotransplanted cancer line. Signal outside CEA-marked metastasis is background. Scale bars, 50 µm. ***, P < 0.001.

We ensured that the micrometastatic lesions are independent entities by demonstrating the absence of branches toward macrometastases using IHC on consecutive sections. In addition, most micrometastases exceeded 1 mm in distance to the macrometastatic lesion (Fig. 1C), which is the margin used for radical resection in the clinic (36).

To examine the cellular composition of micrometastases, we set out to perform IHC analysis for intestinal SC markers. Frequently used intestinal SC markers comprise LGR5, ASCL2, and OLFM4 (30, 37–40). Because of the lack of proven antibodies against human LGR5 or ASCL2, we stained human liver metastases with an OLFM4 antibody whose suitability we confirmed on human colonic sections (Supplementary Fig. S1D). Most macroscopic lesions displayed a heterogeneous expression pattern, reminiscent of a subpopulation of OLFM4+ CSCs. Conversely, all micrometastatic lesions were completely devoid of OLFM4 (Fig. 1D and E; Supplementary Fig. S1G and S1H), suggesting the lack of OLFM4+ CSCs at the micrometastatic stage.

Compromised by limited availability of IHC-compatible SC markers, we decided to corroborate the OLFM-based patient data with the analysis of spontaneously formed liver metastases upon orthotopic transplantation of human colorectal cancer organoids into the cecum of mice (Fig. 1F). In these metastases, we assessed activity of our previously developed intestinal SC reporter STAR (41) that reflects the transcriptional activity of ASCL2, the master regulator of intestinal SC fate (38, 40).

While the number of macrometastases was limited (n = 4, humane endpoint after 9–12 weeks), micrometastatic lesions identified through expression of human CEA were very abundant (n = 30). CSC activity, visualized with STAR-driven sTomato (Supplementary Fig. S1I and S1J), showed a heterogeneous expression pattern in macroscopic metastases, while being enriched at the rim of the tumor where most actively growing clones reside (42). In contrast, no STAR signal could be detected in any microscopic lesion (Fig. 1G and H), indicating that classical CSCs are absent in liver micrometastases of human colorectal cancer.

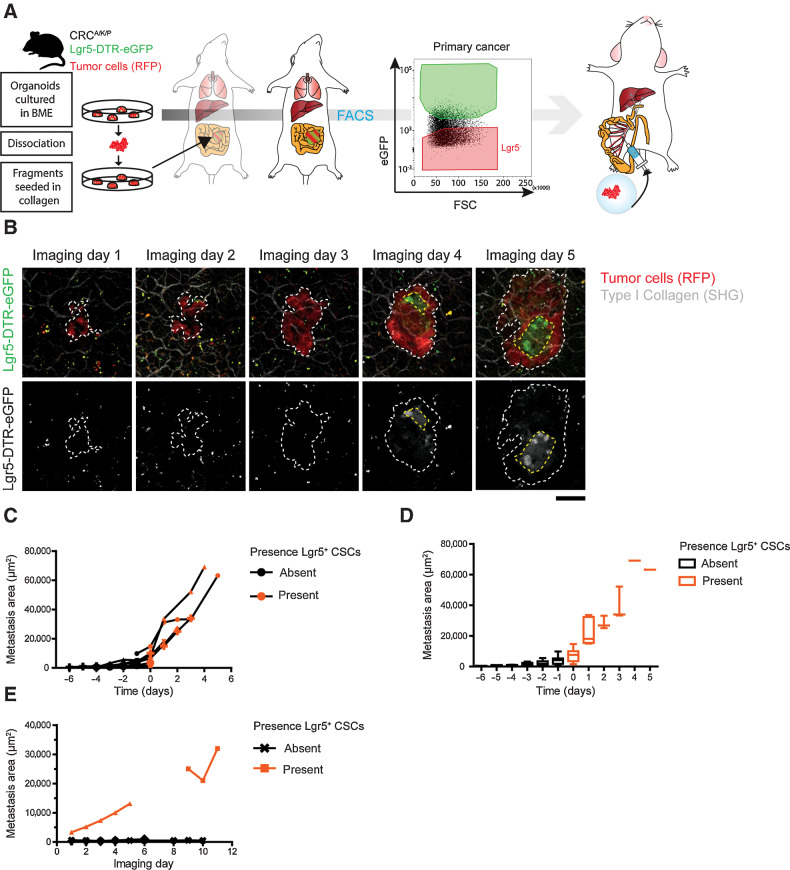

Lgr5+ CSCs appear at micrometastatic stages and mark the transition toward successful metastatic colonization

To understand the relationship between CSC appearance and growth kinetics of liver metastases, we set out to monitor these parameters for individual metastatic lesions over time by IVM. To monitor live metastatic outgrowth, we turned to a well-known mouse colorectal cancer cancer model (Apc, Kras, and Tp53 mutant; ref. 8), in which we used the Lgr5-DTR-eGFP knock-in allele as SC marker. As circulating tumor cells of this model have previously been shown to be Lgr5– (8), we FACS-purified Lgr5– tumor cells as previously described (8) and injected them into the mesenteric vein to synchronize seeding of liver metastases (Fig. 2A). After surgical implantation of an abdominal imaging window (day 5; refs. 22, 43), we could track the outgrowth of multiple metastatic lesions over time (3–10 days), while assessing their size and cellular composition (Fig. 2B–E). Most lesions were first entirely Lgr5– with de novo Lgr5+ cells appearing during the next days. Notably, this symmetry break in terms of spontaneous CSC appearance coincided with a burst in growth (Fig. 2C and D). In strong contrast, microscopic lesions without appearance of Lgr5+ cells displayed limited to no growth (Fig. 2E; Supplementary Fig. S1K). Thus, the establishment of a SC-driven cellular organization defines the transition toward continuous, colonizing growth.

Figure 2.

Lgr5+ CSCs appear at micrometastatic stages and mark the transition toward successful metastatic colonization. A, Experimental setup for timed metastasis formation assay in mice. RFP+ murine ApcFL/FL/KrasG12D/+/Tp53KO/KO cancer organoids were orthotopically transplanted into mice to form primary cancers. After 8 to 10 weeks, Lgr5– primary tumor cells were collected by FACS and injected into the mesenteric vein of recipient mice. Growth kinetics and cellular dynamics of growing liver metastases were monitored by IVM. Stem cells are labeled by endogenous Lgr5-DTR-eGFP expression. B, Representative IVM images of one liver metastasis taken on consecutive days. Top, RFP+ tumor cells (red) visualizing tumor mass and Lgr5-DTR-eGFP expression (green) marking CSCs. Bottom, identical panels in false colors. Dashed line, metastasis border. Scale bar, 50 µm. C, Traces depicting the size of individual metastatic lesions that develop cellular heterogeneity over time. Day 0, time of de novo appearance of Lgr5+ CSCs. Black and orange symbols refer to time points prior to and post symmetry break, respectively. D, As in C, with the mean metastasis size of all lesions represented by a box plot. Whiskers represent minimum to maximum. E, Traces showing the size of individual metastatic lesions over time with no symmetry break event during the course of imaging. Lesion without Lgr5+ SCs (black), lesions with Lgr5 expression before start of IVM (orange).

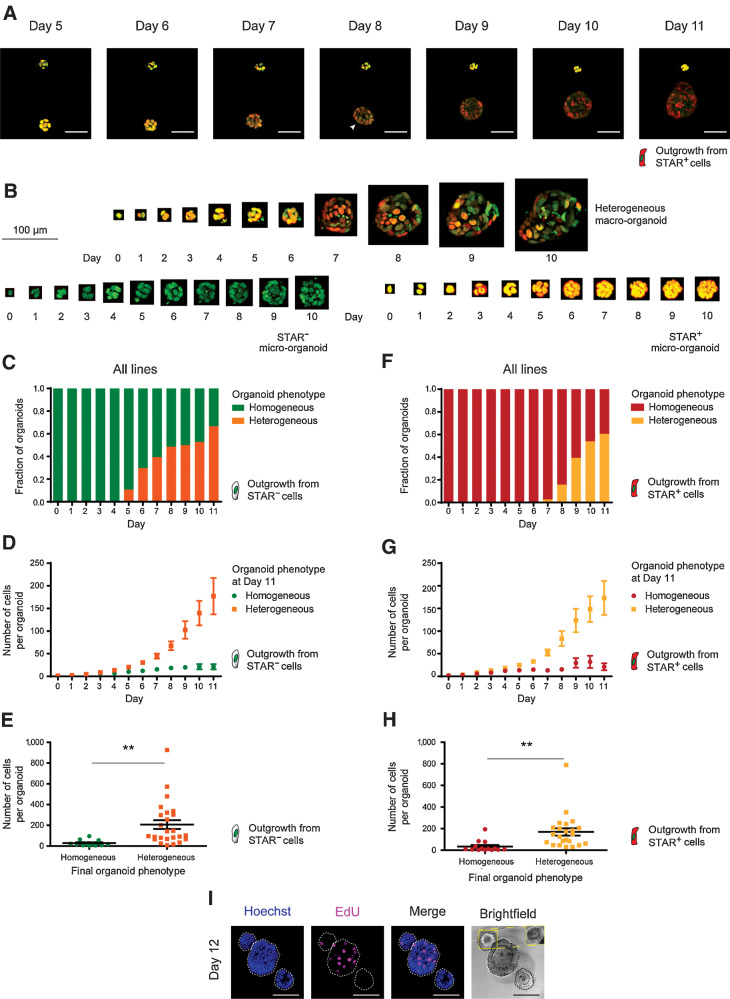

Colorectal cancer organoids phenocopy the cellular dynamics during metastatic outgrowth

Organoids are known for their self-organizing capacity (44). To study early development of human colorectal cancer liver metastases in more detail, we tested whether their growth kinetics and corresponding cellular composition are recapitulated by clonal outgrowth of human colorectal cancer organoids.

Using the STAR reporter to label endogenous ASCL2-driven stem cell activity (nuclear sTomato, Supplementary Fig. S1I) in lines with diverse genetic background, we noticed behavior closely resembling our in vivo observations (Fig. 3A and B). Foremost, STAR– cells gave rise to multicellular structures in the absence of CSCs. After about 5 to 6 days of culture, heterogeneity arose in the majority of the organoids (Fig. 3C; Supplementary Fig. S2A; Supplementary Video S1). When correlating organoid size to phenotypes, it became clear that organoids with a heterogeneous cellular composition were efficiently growing, while organoids that failed to generate CSCs remained restricted in size (Fig. 3D and E; Supplementary Fig. S2B). Intriguingly, when plating single STAR+ cells, we observed similar growth kinetics, timing of symmetry break (corrected for fluorophore decay), and organoid sizes in relation to cellular composition (Fig. 3F–H; Supplementary Fig. S2C–S2G). Indeed, homogeneous STAR+ organoids that failed to break symmetry by differentiation remained growth-restricted similar to their homogeneous STAR– counterparts that lacked CSCs (Fig. 3E and H).

Figure 3.

Colorectal cancer organoids phenocopy the cellular dynamics during metastatic outgrowth. A, Stills from live-cell recordings of A/K/P/S–mutant organoid formation (day 5 to 11) from single nuclear STAR+ cells (red). Top, organoid fails to establish heterogeneity and stagnates in growth. Bottom, organoid develops cellular heterogeneity, indicated by varying STAR levels and continues to grow. Nuclei are marked with a chromatin tag (green). Color hues are red/green overlaid (resulting in yellow to dark orange). Arrowhead, symmetry break. Scale bars, 50 µm. B, 3D-rendered pictures of single cells growing into either a heterogeneous organoid (top) or into homogeneous STAR− (bottom left) or STAR+ (bottom right) micro-organoids. Nuclei (green), STAR (nuclear, red), overlay (yellow). Scale bar, 100 µm. C–H, Pooled data of four human colorectal cancer organoid lines. Engineered APCKO/KO/KRASG12D/–/TP53KO/KO (A/K/P), APCKO/KO/KRASG12D/–/TP53KO/KO/SMADKO/KO (A/K/P/S), PDO P16T, and PDO P19bT. Data are stratified by STAR identity at the time of plating. Outgrowth of STAR−/STAR+ cells with homogeneously STAR− (green)/STAR+ (red) organoids and heterogeneous organoids (orange/yellow). C and F, Graph representing the fraction of organoid phenotypes per indicated time point during the outgrowth of STAR–/STAR+ colorectal cancer cells. D and G, Graph representing the size (mean cell number + SEM) of developing organoids from single STAR–/STAR+ cells, stratified by final phenotype. E and H, Organoid size per final phenotype for the outgrowth of single STAR–/STAR+ cells. Two-tailed Student t test (P value, 0.0070/0.0045) indicates significant difference. I, Three 12-day-old organoids with EdU incorporation (pink) to label proliferative cells. Blue, counterstain Hoechst 33342. Inset (yellow) shows optimal brightfield cross-section. Scale bars, 100 µm. **, P < 0.01.

To further consolidate these findings, STAR was introduced into a set of eight independent colonic organoid lines with diverse sets of driver mutations (representative of either normal, adenoma, or malignant state). Again, analysis confirmed that organoids that failed to develop cell type heterogeneity, being pure CSC or non-CSC organoids, became growth stagnated (Supplementary Fig. S3A and S3B). The difference in the proliferative behavior between macro- and micro-organoids was further demonstrated by EdU incorporation on day 11 (Fig. 3I). Importantly, using a computed growth rate per cell, we confirmed that generating cellular heterogeneity is functionally supportive of organoid growth rather than being a stochastic result linked to higher cell numbers (Supplementary Fig. S2F and S2G).

Next, we assessed the pattern by which de novo CSCs emerged during plasticity events in live-cell recordings of organoid outgrowth with respect to their preceding mitosis (Supplementary Fig. S3C; Supplementary Video S1). We found no link when comparing STAR levels in the first emerging STAR+ CSCs to their direct sisters, which were either diverging or comparable (Supplementary Fig. S3D–S3F vs. Supplementary Fig. S3G–S3I). Likewise, the onset of STAR level increase seemed uncoupled to the timing of the preceding mitosis (Supplementary Fig. S3D and S3E vs. Supplementary Fig. S3F and S3I).

Growth-restricted micro-organoids are in a YAP state

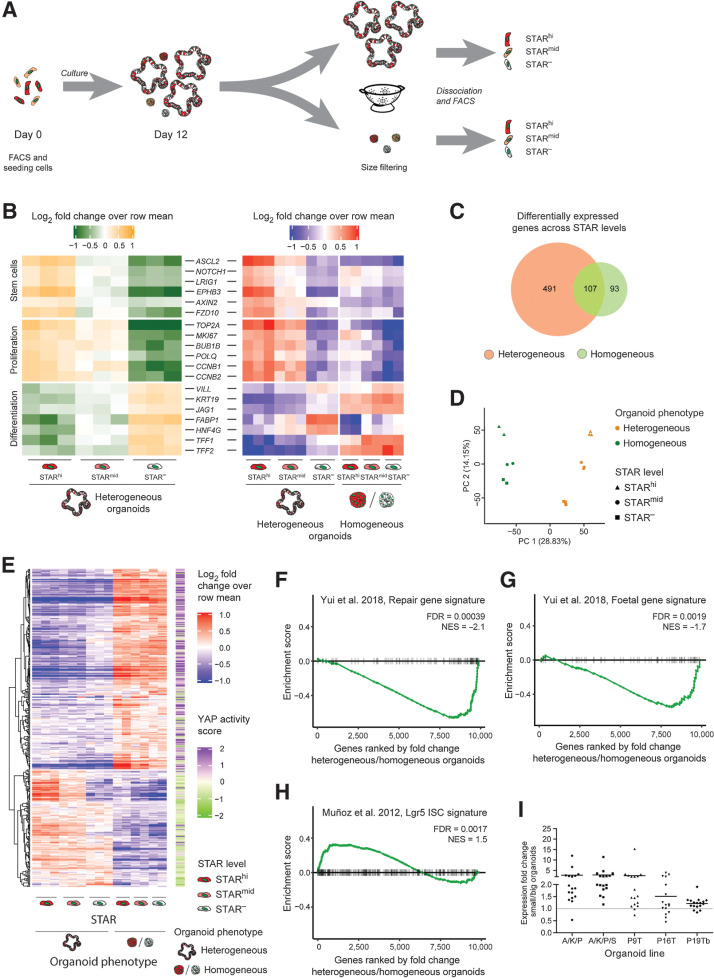

To understand why the development of cell type heterogeneity coincides with sustained growth, we set out to transcriptionally profile cells with various STAR levels from either growth-stagnated (micro) organoids or from cellular heterogeneous (large) organoids (Fig. 4A). We chose A/K/P/S organoids as they depict a pronounced size difference between organoid phenotypes, which enables their separation by size (Supplementary Figs. S2B and S2D and S4A). Moreover, they grow in the absence of niche-derived growth factors, which suggests that the growth stagnation of micro-organoids is a tumor-intrinsic failure.

Figure 4.

Growth restricted micro-organoids are in a YAP state. A, Experimental setup. Single STAR+ cells were cultured for 12 days. Organoids were size separated and STARhi, STARmid, and STAR− cells were collected by FACS for each organoid subfraction for prospective expression analysis. B, Heatmap representing expression levels of intestinal markers for SCs, proliferation, and differentiation (log2-fold change over row mean). Left, relative expression per STAR population of only heterogeneous organoids. Right, both organoid types. C, Venn diagram depicting the number of differentially expressed genes across STAR populations (FDR < 0.01 in at least one comparison) in heterogeneous (orange) and homogeneous (green) organoids. D, Principal component analysis of the expression patterns across STAR populations and organoid phenotypes. E, Heatmap showing all 369 differentially expressed genes between small (homogeneous) and large (heterogeneous) organoids (fold change > 1.5, FDR < 0.05), for which, the assigned YAP score (right side) represents at least a 10% change (YAP score < 0.9 (green) or > 1.1 (purple); score from ref. 28. F–H, GSEA demonstrating the similarity of (homogeneous) micro-organoids to the regenerative state of mouse intestine (ref. 31; F), the fetal state of mouse intestine (ref. 31; G), or of large (heterogeneous) organoids to intestinal SCs (ref. 30; H). I, Expression pattern (by qPCR) of 17 micro-organoid–associated genes across five lines. Horizontal bar per line, mean fold change of all genes. Individual values depicted in Supplementary Fig. S5A.

Transcriptomic analysis demonstrated anticipated expression patterns in heterogeneous (large) organoids: The STARhi population was enriched for SC markers/Wnt targets (such as ASCL2, AXIN2, NOTCH1) and proliferation markers (MKI67, CCNB1, CCNB2), while the STAR− population showed increased expression of differentiation markers such as VILL, KRT19, JAG1, TFF2, and HNF4G (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, in contrast to the differential expression of mature cell type markers, the cellular states within the homogeneous micro-organoids seemed to be less diverse, with immature CSCs and high expression of some differentiation markers (Fig. 4B and C; Supplementary Fig. S4B and S4C). In line with this, principal component analysis of all samples revealed that the strongest source of biological variance related to the organoid phenotype, directly followed by the level of SC activity (Fig. 4D).

Next, unbiased analysis of the differentially expressed genes between big and small organoids (1,985 genes, fold change > 1.5, FDR < 0.05) suggested YAP signaling as the strongest enriched signature in micro-organoids (FDR < 2.1 × 10–6; Supplementary Fig. S4D). Moreover, the addition of a computed YAP score that is based on in vivo perturbation studies (28), indicated that 40% of these genes show a high probability to be target genes of YAP activity (Fig. 4E; Supplementary Fig. S4E). In addition, gene signatures derived from previous YAP/TAZ studies (16, 31), in contrast to an intestinal SC signature, positively correlate with the expression pattern in growth-stalled micro-organoids (Fig. 4F–H).

Reassuring, a set of these genes (Supplementary Table S3) was generally enriched in micro-organoids across different lines (Fig. 4I; Supplementary Fig. S5A), confirming similar YAP activity in micro-organoids regardless of the mutational background.

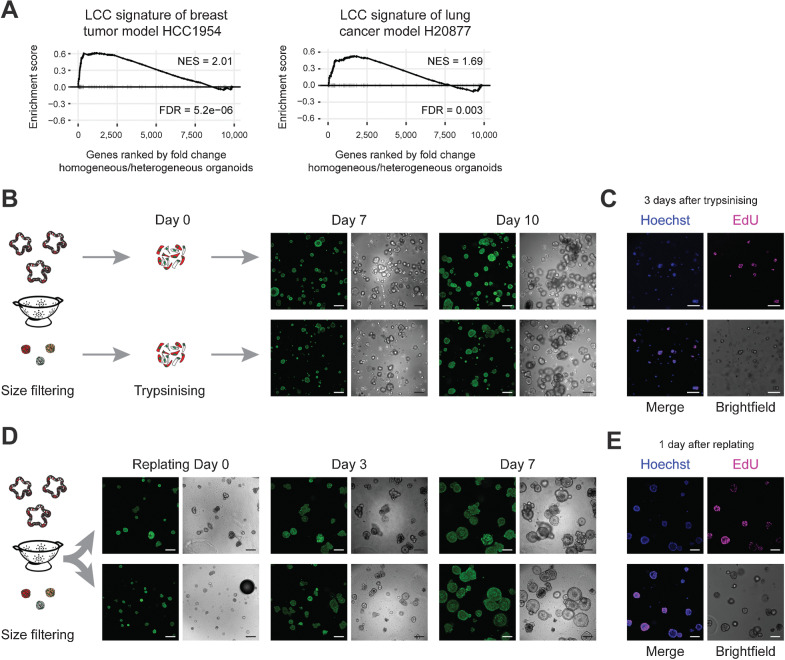

Micro-organoids are in a pseudo-stable state and resemble dormant micrometastases

Growth-stalled micro-organoids and dormant micrometastases both lack mature CSCs and demonstrate limited proliferative behavior. Assessing whether micro-organoids are also transcriptionally similar to micrometastases is challenging due to their elusive nature and lack of colorectal cancer micrometastatic model systems. As closest alternative, we exploited expression data of latency-competent cells (LCC) from lung adenocarcinoma and breast tumor models that can only form small metastatic foci in mice (13). We found strong similarity in expression patterns between our micro-organoids and LCCs (Fig. 5A), corroborating the extent of similarity between micro-organoids and micrometastases.

Figure 5.

Micro-organoids are in a pseudo-stable state and resemble dormant micrometastases. A, GSEA demonstrating similarity of micro-organoids to alternative models of metastatic dormancy (breast tumor line HCC1954 and lung adenocarcinoma line H20877; ref. 13). B, Outgrowth potential of single cells derived from micro- or macro-organoids (A/K/P/S) isolated after 12 days of culturing. Green, H2B. Scale bars, 200 µm. C, EdU incorporation (pink) indicates proliferating cells 3 days after plating single cells derived from micro-organoids. Blue, counterstain Hoechst 33342. Scale bars, 100 µm. D, Growth potential of 12-day-old micro- and macro-organoids (A/K/P/S) upon isolation and replating as intact structures. Green, H2B. Scale bars, 200 µm. E, EdU incorporation (pink) indicates regained proliferative activity of micro-organoids 1 day after replating. Blue, counterstain Hoechst 33342. Scale bars, 100 µm.

An additional functional property of colorectal cancer micrometastases in livers is their capacity to reinitiate growth after years of being dormant. Using organoid formation capacity of micro-organoid–derived cells, we demonstrated renewed proliferation in virtual all cells as shown by the incorporation of EdU within 16 hours (Fig. 5B and C). Moreover, over time, they generated large organoid structures that are indistinguishable from a normal culture (Fig. 5B), supporting the notion that tumor cells in micro-organoids are intrinsically fine, yet remain in a pseudo-stable, nonproliferative state. Likewise, isolation and replating of intact micro-organoids revealed again their capacity to reenter a proliferative state and transition to mature organoids (Fig. 5D and E), while YAP activity decreased (Supplementary Fig. S5B).

Dynamic YAP activity is required for the outgrowth of colorectal cancer organoids

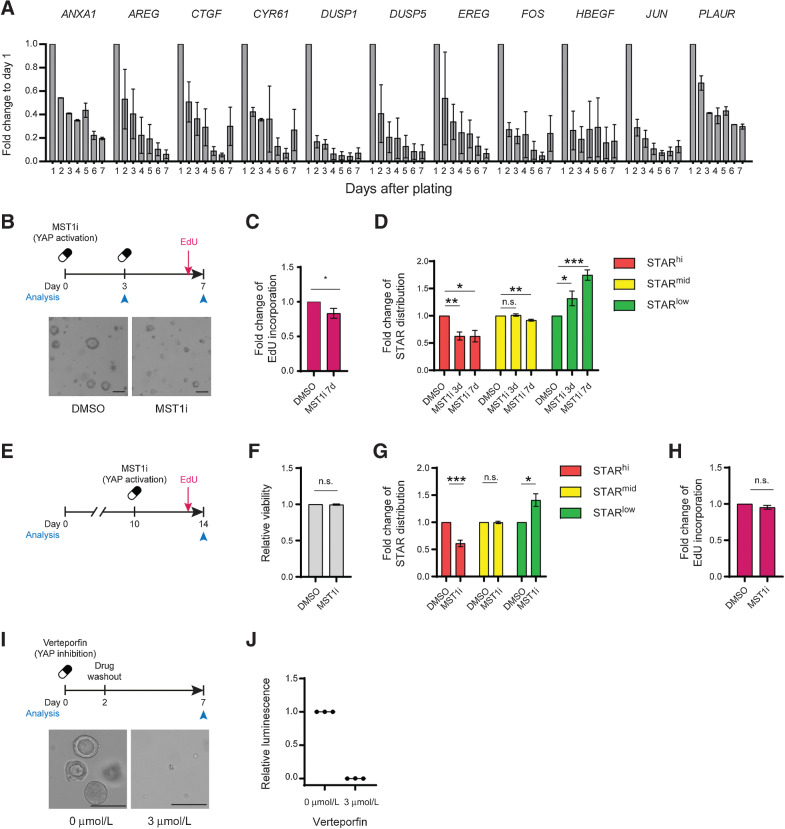

To understand the origin of active YAP/TAZ signaling in growth-stagnated micro-organoids, we assessed the temporal expression patterns of micro-organoid–related YAP genes during clonal organoid formation. As observed in mouse organoids (16), most YAP genes demonstrated highest expression levels during the earliest stage of outgrowth, which subsequently decreased over time (Fig. 6A; Supplementary Fig. S5C), suggesting that the transcriptional state of micro-organoids mimics the earliest stages of organoid outgrowth prior to symmetry break.

Figure 6.

Dynamic Yap activity is required for the outgrowth of colorectal cancer organoids. A, Diminishing expression of micro-organoid–associated genes during the first 7 days of A/K/P/S organoid outgrowth. Gene expression, represented as mean + SEM, is normalized to day 1. B–D, Single A/K/P/S cells treated with 500 nmol/L XMU-MP-1 (MST1/2 inhibitor) for 3 or 7 days. B, Schematic of experimental setup (top) and representative organoid overview after 7 days of culture (bottom). Scale bars, 100 µm. C, Relative fraction of EdU-incorporating cells. D, Flow analysis of STAR levels. C and D, Data is normalized to DMSO control. E–H, Ten-day-old A/K/P/S organoids were treated with 500 nmol/L XMU-MP-1 and analyzed after 96 hours by flow cytometry. E, Experimental setup. F, Relative viability assessed by DAPI. G, Relative change in STAR populations. H, Relative fraction of EdU-incorporating cells. F–H, Data are normalized to their respective DMSO control. I–J, Three µmol/L verteporfin was added to single A/K/P/S cells for 48 hours prior to wash out. Organoids were analyzed after 7 days. I, Schematic of experimental setup (top) and representative organoid overview after 7 days of culture (bottom). Scale bars, 100 µm. J, Relative viability as assessed by CellTiter-Glo. Data are normalized to DMSO control. n.s., nonsignificant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

To assess whether persistent YAP signaling is related to the homogeneous nature of micro-organoids, we measured SC activity upon perturbing YAP signaling activity. Inducible expression of YAP5SA, a constitutively active YAP mutant, led to transcriptional downregulation of intestinal SC markers in multiple lines, while overexpression of the inactive mutant YAPS94A had no effect (Supplementary Fig. S5D). To confirm this on protein level, we chose flow cytometry analysis over Western blot, due to low expression levels of intestinal SC markers and a lack of proven antibodies. As expected, expressing YAP5SA for 48 hours in different colorectal cancer organoids prior to symmetry break induced a loss of STARhi CSCs, while STARlo cells became more frequent (Supplementary Fig. S5E). Conversely, upon inducible expression of YAP inhibitor YTIP (45), the fraction of CSCs increased at the expense of the STARlo population (Supplementary Fig. S5E).

Next, to activate Yap signaling activity to more physiologic levels, we made use of the MST1/2 inhibitor XMU-MP-1, which prevents inactivation of YAP by LATS1/2 (46). Across multiple lines, organoids treated with XMU-MP-1 at functional, nontoxic levels were smaller in size (Fig. 6B; Supplementary Fig. S5F–S5I) and showed reduced EdU incorporation (Fig. 6C) compared with controls. In addition, these YAP-activated organoids revealed a similar reduction in STARhi CSCs (Fig. 6D), as seen previously through active Yap5SA overexpression. Thus, counteracting the physiologic decay of early-stage YAP activity in colorectal cancer PDOs compromises the formation of mature CSCs and persistent YAP activity can induce growth-stalled micro-organoids.

Next, we treated 8-day-old A/K/P/S organoids with XMU-MP-1 (Fig. 6E and F). In these mature colorectal cancer organoids we scored again a reduction in CSC numbers (Fig. 6G). However, in contrast to the organoid formation data, proliferation both overall and stratified by STAR population, was not affected at this stage (Fig. 6H; Supplementary Fig. S5J and S5K). Finally, we tested the consequence of inhibiting the early-stage YAP activity wave using verteporfin at nontoxic levels (Supplementary Fig. S5L). As previously described for low-grade APCKO colorectal cancer lines (31), preventing YAP activity during the first 2 days of outgrowth entirely blocked organoid formation (Fig. 6I and J). Thus, YAP activity is essential for single colorectal cancer cells, yet needs to decay over time to enable the formation of CSCs and to sustain proliferation.

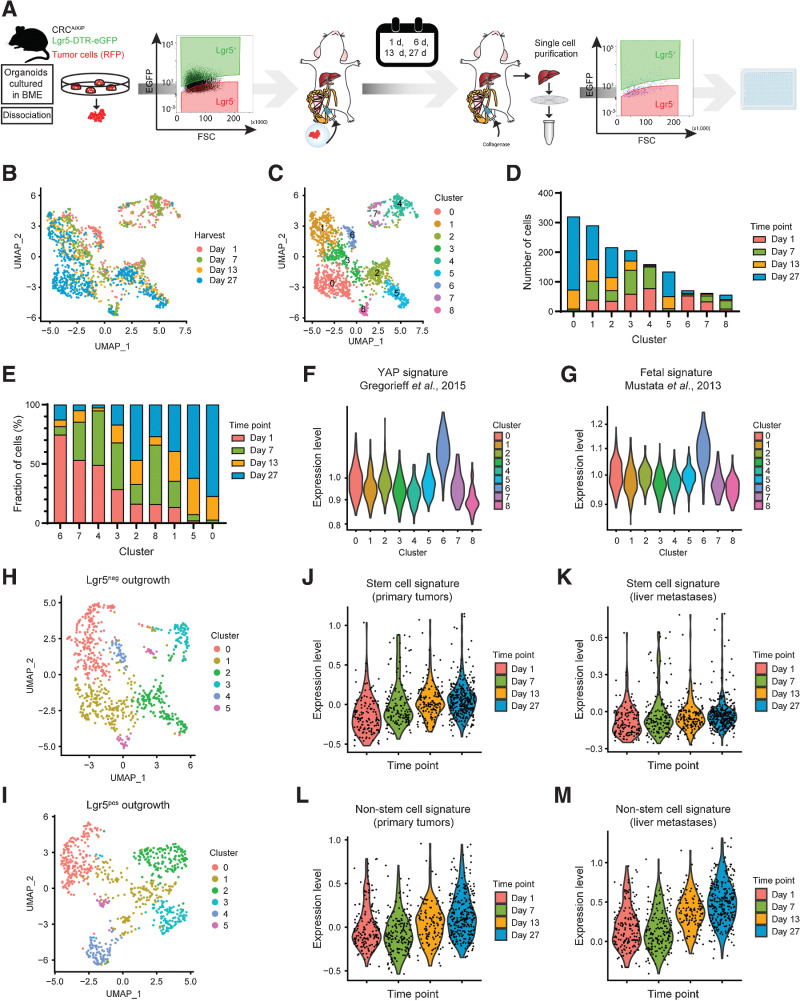

Mapping cellular phenotypes during in vivo formation of colorectal cancer liver metastases

To assess whether the dynamic expression patterns underlying colorectal cancer organoid formation can be translated to a metastatic setting, we investigated the cellular composition during liver metastasis formation over time by scRNA-seq (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7.

Mapping cellular phenotypes during in vivo formation of colorectal cancer liver metastases. A, Experimental design of scRNA-seq analysis of metastatic cells at specific time points during in vivo liver metastasis formation initiated by either Lgr5+ or Lgr5– colorectal cancer cells. B and C, UMAP of scRNA-seq data color-coded by time of harvest (B) and clusters (C) resulting from unsupervised hierarchical clustering. D and E, Composition of clusters color-coded by time of harvest. D, Absolute number of cells. E, Relative composition of clusters ranked (in descending order) according to highest relative contribution from day 1. F and G, Expression levels of Yap-associated gene signatures by cluster for Yap overexpression (F) in murine intestine (28) and fetal intestinal organoids (ref. 34; G). H and I, UMAP after unsupervised hierarchical clustering of all Lgr5−- (H) and Lgr5+- (I) injected cells. J–M, Expression levels of SC (J and K) and non-SC (L and M) gene signatures over time. Signatures are derived from primary tumors (ref. 8; J and L) and liver metastases (ref. 8; K and M). Data input: Lgr5–- (J and K) and Lgr5+- (L and M) injected cells.

First, we noticed that Lgr5 constitutes a suitable SC marker in this cancer model, considering its coexpression with other SC markers (Supplementary Fig. S6A and S6B). Next, in agreement with the fact that both Lgr5+ CSCs and Lgr5– non-CSCs are capable of forming metastases in injection assays (8), we noticed that the initial Lgr5 status at the time of injection does not majorly influence the transcriptomic phenotype of metastatic cells (Supplementary Fig. S6C). Conversely, the age of the metastases (1, 7, 14, and 27 days) strongly correlates with transcriptional changes in our data set (Fig. 7B), indicating major changes in cellular phenotypes during liver colonization by colorectal cancer metastases.

Unsupervised clustering of all cells resulted in nine distinct clusters (Fig. 7C and D), which were subsequently ranked by their relative abundance of cells per time point (Fig. 7E). Cluster 6, the cluster predominantly made up of cells from day 1, revealed an enrichment for many known YAP target genes (e.g., Edn, Mlsn, Amotl2) including those enriched in micro-organoids (Ctgf, Cyr61, Ankrd1; Supplementary Fig. S6D) and also associates most strongly with published YAP signatures (Fig. 7F and G). Conversely, gene expression patterns of cells arising late during metastatic outgrowth (clusters 0, 5, and 1; Fig. 7E), showed particular enrichment of SC markers (Lgr5, DTR-eGFP, Smoc2) and SC-associated genes (Hes1, Hnf4a) in the dominant late-stage clusters 0 and 1 (Supplementary Fig. S6E).

Next, we stratified the data set by the Lgr5 status at the time of injection and analyzed the developing cellular phenotypes separately (Fig. 7H and I). In line with the need for Lgr5+ CSC for metastatic growth (5), we found that Lgr5 and Ascl2 are becoming more widely expressed over time in metastases originating from Lgr5– cells (Supplementary Fig. S6F and S6G), as well as previously obtained (8) gene expression signatures of Lgr5+ CSCs (Fig. 7J and K). Interestingly, also gene expression signatures for non-CSCs increased slightly over time (Supplementary Fig. S6H and S6I), suggesting that non-CSCs in older metastases start matching those of primary tumors. Similarly, signatures for non-CSCs became more pronounced over time during metastasis formation by Lgr5+ CSC (Fig. 7L and M).

Thus, regardless of the metastatic cell of origin, also in vivo cellular heterogeneity is generated over time and is preceded by YAP activity at the earliest stage.

Discussion

The metastatic cascade is a multi-step cell-biological process that includes cell migration, intravasation, metastatic seeding, and outgrowth (47). The process of outgrowth, or metastatic colonization, is a highly inefficient, rate-limiting step that depends on complex interactions between tumor cells and the microenvironment (10). Yet, the cell-intrinsic properties underlying successful transition to metastatic colonization and developmental trajectory of cells are poorly understood. Among others, due to their sporadic occurrence and limited size, micrometastases are difficult to identify and characterize. Foremost, functional studies are hampered as the number of appropriate model systems is limited.

In this study, we used patient biopsies, colorectal cancer PDOs, mouse models of colorectal cancer, and human tumor xenografts to investigate at high spatial and temporal resolution the phenotypic and transcriptional changes taking place during the transition from micrometastases to successful liver colonization (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Summarizing model.

Our patient-related data is in agreement with previous mouse studies demonstrating the ultimate need for Lgr5+ colorectal CSCs for metastatic outgrowth (5, 8). In addition, our study is complementary to the previous finding that the majority of metastases is seeded by Lgr5– cells (8). However, irrespective of the identity of the seeding cell, our in vitro and in vivo data indicate that both CSC and non-CSC have the capacity to establish cell type heterogeneity and form successfully growing metastases. Moreover, our data show that generation of cell type heterogeneity through epithelial self-organization is essential, as pure CSC or non-CSC organoids become growth stagnated. In analogy to the SC support that is provided by differentiated Paneth cells in the normal intestine (48), it is conceivable that non-CSCs fulfill a similar role in promoting CSC function, even in a highly mutated background. Furthermore, our data is in line with L1CAM+ cells being essential for metastatic colonization of colorectal cancer (49), because L1CAM is known to induce YAP/TAZ activity in lung and breast cancer models (50).

Intriguingly, the cellular dynamics and transcriptomic changes during metastatic outgrowth is accurately phenocopied by clonal outgrowth of colorectal cancer PDOs. Moreover, the processes underlying cell type maturation and CSC appearance at a multicellular stage draw similarities to the symmetry break in mouse small intestinal organoids, during which an initial YAP high/proliferative state precedes the reappearance of Lgr5+ SCs and subsequent crypt formation (16). We show that this level of epithelial self-organization is shared across multiple colorectal cancer PDOs, making organoid formation by colorectal cancer PDOs a tractable disease model to study live-cell biology during early-stage liver metastasis formation.

We also scored a fraction of colorectal cancer micro-organoids that failed to establish cellular heterogeneity and was compromised in growth. These micro-organoids contain a homogeneous population of immature cell types with strong expression of transcriptional YAP targets. This finding is in line with the notion that YAP activity represses in particular target genes requiring high Wnt levels like SC genes, while more progenitor-associated Wnt target genes, and as a consequence proliferative behavior, seem preserved (Fig. 6G and H; refs. 28, 31, 51, 52). Persistent YAP activity in micro-organoids most likely originates from the physiologic and essential YAP spike during the earliest stages of organoid formation. Moreover, we demonstrate that its subsequent decay is critical, as maturation and growth of colorectal cancer organoids is otherwise prohibited. These transcriptional changes are in line with our in vivo experiments and are functionally supported by earlier studies demonstrating that YAP activation in murine colorectal cancer cells prevents liver metastases (51). While our data supports a preceding role for YAP activity during cellular plasticity, future studies are warranted to resolve the underlying molecular mechanisms in full detail.

Several publications have linked YAP/TAZ activity in primary cancers to poor patient survival (53–55). More specifically in colorectal cancers, YAP activity and migratory behavior are linked to cell populations (Lgr5– or L1CAM+) that are endowed with metastasis-initiating capacity (8, 49, 50, 56), providing an explanation for YAP as a biomarker based on primary colorectal cancer tissues. Complementary to this, we show that that early-stage YAP promotes single cell survival and that loss of YAP activity at the metastatic site is essential to enable CSC formation, subsequent maturation, and growth of the lesion.

In analogy to our experimental data, it is conceivable that failure to establish epithelial self-organization at the micrometastatic stage constitutes an epithelial, tumor-intrinsic cause underlying the formation of dormant micrometastases in the liver of patients with colorectal cancer. As the microenvironment constitutes a further strong determinant of metastatic colonization (13, 57), it will be of interest to study its influence on the propensity of micrometastases to establish cellular reorganization. The conceptual idea that dormant micrometastases are stuck during their early developmental trajectory is a novel perspective that provides a possible explanation for their state of cellular quiescence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all colleagues, the UMCU Flow Core Cytometry Facility, and the UMCU tissue facility (Department of Pathology) for continuous support and many fruitful discussions. This work was supported by a KWF fellowship from the Dutch Cancer Society (UU 2013–6070) and an ERC Starting Grant (IntratumoralNiche - 803608, both awarded to H.J.G. Snippert). J. van Rheenen was supported by the Doctor Josef Steiner Foundation. This work is part of the Oncode Institute, which is partly financed by the Dutch Cancer Society.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked advertisement in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Research Online (http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

Authors' Disclosures

J. van Rheenen reports grants from Josef Steiner Foundation during the conduct of the study. H.J.G. Snippert reports grants from ERC (StG) and grants from Dutch Cancer Society during the conduct of the study. No disclosures were reported by the other authors.

Authors' Contributions

M.C. Heinz: Conceptualization, data curation, software, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. N.A. Peters: Conceptualization, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing–review and editing, co-first author. K.C. Oost: Formal analysis, investigation, visualization. R.G.H. Lindeboom: Data curation, software, formal analysis, visualization, methodology. L. van Voorthuijsen: Conceptualization, investigation, visualization, writing–original draft. A. Fumagalli: Formal analysis, investigation, visualization, methodology. M.C. van der Net: Investigation, visualization. G. de Medeiros: Software, investigation, visualization, methodology. J.H. Hageman: Formal analysis, investigation, visualization. I. Verlaan-Klink: Investigation, visualization. I.H.M. Borel Rinkes: Resources, methodology. P. Liberali: Conceptualization, writing–original draft. M. Gloerich: Conceptualization, writing–original draft. J. van Rheenen: Conceptualization, resources, methodology, writing–original draft. M. Vermeulen: Conceptualization, resources, data curation, visualization, methodology, writing-original draft. O. Kranenburg: Conceptualization, resources, validation, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing, co-corresponding author. H.J.G. Snippert: Conceptualization, resources, supervision, visualization, writing-original draft, writing–review and editing.

References

- 1. Schepers AG, Snippert HJ, Stange DE, Van Den Born M, Van Es JH, Van De Wetering M, et al. Lineage tracing reveals Lgr5+ stem cell activity in mouse intestinal adenomas. Science 2012;337:730–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Humphries A, Cereser B, Gay LJ, Miller DSJ, Das B, Gutteridge A, et al. Lineage tracing reveals multipotent stem cells maintain human adenomas and the pattern of clonal expansion in tumor evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:E2490–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shimokawa M, Ohta Y, Nishikori S, Matano M, Takano A, Fujii M, et al. Visualization and targeting of LGR5 + human colon cancer stem cells. Nature 2017;545:187–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morral C, Stanisavljevic J, Hernando-Momblona X, Mereu E, Álvarez-Varela A, Cortina C, et al. Zonation of ribosomal DNA transcription defines a stem cell hierarchy in colorectal cancer. Cell Stem Cell 2020;26:845–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. De Sousa E Melo F, Kurtova AV, Harnoss JM, Kljavin N, Hoeck JD, Hung J, et al. A distinct role for Lgr5 + stem cells in primary and metastatic colon cancer. Nature 2017;543:676–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hageman JH, Heinz MC, Kretzschmar K, van der Vaart J, Clevers H, Snippert HJG. Intestinal regeneration: regulation by the microenvironment. Dev Cell 2020;54:435–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tauriello DVF, Calon A, Lonardo E, Batlle E. Determinants of metastatic competency in colorectal cancer. Mol Oncol 2017;11:97–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fumagalli A, Oost KC, Kester L, Morgner J, Bornes L, Bruens L, et al. Plasticity of Lgr5-negative cancer cells drives metastasis in colorectal cancer. Cell Stem Cell 2020;26:569–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Obenauf AC, Massagué J. Surviving at a distance: Organ-specific metastasis. Trends Cancer 2015;1:76–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Massagué J, Obenauf AC. Metastatic colonization by circulating tumour cells. Nature 2016;529:298–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sosa MS, Bragado P, Aguirre-Ghiso JA. Mechanisms of disseminated cancer cell dormancy: An awakening field. Nat Rev Cancer 2014;14:611–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tauriello DVF, Palomo-Ponce S, Stork D, Berenguer-Llergo A, Badia-Ramentol J, Iglesias M, et al. TGFβ drives immune evasion in genetically reconstituted colon cancer metastasis. Nature 2018;554:538–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Malladi S, Macalinao DG, Jin X, He L, Basnet H, Zou Y, et al. Metastatic latency and immune evasion through autocrine inhibition of WNT. Cell 2016;165:45–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yuki K, Cheng N, Nakano M, Kuo CJ. Organoid models of tumor immunology. Trends Immunol 2020;41:652–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lindeboom RG, van Voorthuijsen L, Oost KC, Rodríguez-Colman MJ, Luna-Velez MV, Furlan C, et al. Integrative multi-omics analysis of intestinal organoid differentiation. Mol Syst Biol 2018;14:e8227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Serra D, Mayr U, Boni A, Lukonin I, Rempfler M, Challet Meylan L, et al. Self-organization and symmetry breaking in intestinal organoid development. Nature 2019;569:66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Basak O, Beumer J, Wiebrands K, Seno H, van Oudenaarden A, Clevers H. Induced quiescence of Lgr5+ stem cells in intestinal organoids enables differentiation of hormone-producing enteroendocrine cells. Cell Stem Cell 2017;20:177–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beumer J, Puschhof J, Bauzá-Martinez J, Martínez-Silgado A, Elmentaite R, James KR, et al. High-resolution mRNA and secretome Atlas of human enteroendocrine cells. Cell 2020;181:1291–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fumagalli A, Suijkerbuijk SJE, Begthel H, Beerling E, Oost KC, Snippert HJ, et al. A surgical orthotopic organoid transplantation approach in mice to visualize and study colorectal cancer progression. Nat Protoc 2018;13:235–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van der Bij GJ, Bögels M, Otten MA, Oosterling SJ, Kuppen PJ, Meijer S, et al. Experimentally induced liver metastases from colorectal cancer can be prevented by mononuclear phagocyte-mediated monoclonal antibody therapy. J Hepatol 2010;53:677–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ritsma L, Steller EJA, Ellenbroek SIJ, Kranenburg O, Borel Rinkes IHM, Van Rheenen J. Surgical implantation of an abdominal imaging window for intravital microscopy. Nat Protoc 2013;8:583–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ritsma L, Steller EJA, Beerling E, Loomans CJM, Zomer A, Gerlach C, et al. Intravital microscopy through an abdominal imaging window reveals a pre-micrometastasis stage during liver metastasis. Sci Transl Med 2012;4:158ra145 LP–158ra145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Klaunig JE, Goldblatt PJ, Hinton DE, Lipsky MM, Trump BF. Mouse liver cell culture. I. Hepatocyte isolation. In Vitro 1981;17:913–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Drost J, van Jaarsveld RH, Ponsioen B, Zimberlin C, van Boxtel R, Buijs A, et al. Sequential cancer mutations in cultured human intestinal stem cells. Nature 2015;521:43–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van de Wetering M, Francies HE, Francis JM, Bounova G, Iorio F, Pronk A, et al. Prospective derivation of a living organoid biobank of colorectal cancer patients. Cell 2015;161:933–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dekkers JF, Alieva M, Wellens LM, Ariese HCR, Jamieson PR, Vonk AM, et al. High-resolution 3D imaging of fixed and cleared organoids. Nat Protoc 2019;14:1756–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014;15:1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gregorieff A, Liu Y, Inanlou MR, Khomchuk Y, Wrana JL. Yap-dependent reprogramming of Lgr5+ stem cells drives intestinal regeneration and cancer. Nature 2015;526:715–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Korotkevich G, Sukhov V, Budin N, Shpak B, Artyomov MN, Sergushichev A, et al. Fast gene set enrichment analysis. bioRxiv [Internet]. 2021;60012. Available from: http://biorxiv.org/content/early/2021/02/01/060012.abstract.

- 30. Muñoz J, Stange DE, Schepers AG, Van De Wetering M, Koo BK, Itzkovitz S, et al. The Lgr5 intestinal stem cell signature: Robust expression of proposed quiescent ‘+4’ cell markers. EMBO J 2012;31:3079–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yui S, Azzolin L, Maimets M, Pedersen MT, Fordham RP, Hansen SL, et al. YAP/TAZ-dependent reprogramming of colonic epithelium links ECM remodeling to tissue regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 2018;22:35–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Muraro MJ, Dharmadhikari G, Grün D, Groen N, Dielen T, Jansen E, et al. A single-cell transcriptome Atlas of the human pancreas. Cell Syst 2016;3:385–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stuart T, Butler A, Hoffman P, Hafemeister C, Papalexi E, Mauck WM, et al. Comprehensive integration of single-cell data. Cell 2019;177:1888–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mustata RC, Vasile G, Fernandez-Vallone V, Strollo S, Lefort A, Libert F, et al. Identification of Lgr5-independent spheroid-generating progenitors of the mouse fetal intestinal epithelium. Cell Rep 2013;5:421–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tallapragada NP, Cambra HM, Wald T, Keough Jalbert S, Abraham DM, Klein OD, et al. Inflation-collapse dynamics drive patterning and morphogenesis in intestinal organoids. Cell Stem Cell 2021;28:1516–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Postriganova N, Kazaryan AM, Røsok BI, Fretland ÅA, Barkhatov L, Edwin B. Margin status after laparoscopic resection of colorectal liver metastases: Does a narrow resection margin have an influence on survival and local recurrence? Hpb 2014;16:822–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, Kujala P, van den Born M, Cozijnsen M, et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature 2007;449:1003–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schuijers J, Junker JP, Mokry M, Hatzis P, Koo BK, Sasselli V, et al. Ascl2 acts as an R-spondin/wnt-responsive switch to control stemness in intestinal crypts. Cell Stem Cell 2015;16:158–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. van der Flier LG, Haegebarth A, Stange DE, van de Wetering M, Clevers H. OLFM4 is a robust marker for stem cells in human intestine and marks a subset of colorectal cancer cells. Gastroenterology 2009;137:15–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. van der Flier LG, van Gijn ME, Hatzis P, Kujala P, Haegebar A, Stange DE, et al. Transcription factor achaete scute-like 2 controls intestinal stem cell fate. Cell 2009;136:903–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Oost KC, van Voorthuijsen L, Fumagalli A, Lindeboom RGH, Sprangers J, Omerzu M, et al. Specific labeling of stem cell activity in human colorectal organoids using an ASCL2-responsive minigene. Cell Rep 2018;22:1600–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Van Der Heijden M, Miedema DM, Waclaw B, Veenstra VL, Lecca MC, Nijman LE, et al. Spatiotemporal regulation of clonogenicity in colorectal cancer xenografts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:6140–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ritsma L, Ellenbroek SIJ, Zomer A, Snippert HJ, De Sauvage FJ, Simons BD, et al. Intestinal crypt homeostasis revealed at single-stem-cell level by in vivo live imaging. Nature 2014;507:362–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Xavier da Silveira dos Santos A, Liberali P. From single cells to tissue self-organization. FEBS J 2019;286:1495–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Von Gise A, Lin Z, Schlegelmilch K, Honor LB, Pan GM, Buck JN, et al. YAP1, the nuclear target of Hippo signaling, stimulates heart growth through cardiomyocyte proliferation but not hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:2394–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fan F, He Z, Kong LL, Chen Q, Yuan Q, Zhang S, et al. Pharmacological targeting of kinases MST1 and MST2 augments tissue repair and regeneration. Sci Transl Med 2016;8:352ra108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Valastyan S, Weinberg RA. Tumor metastasis: Molecular insights and evolving paradigms. Cell 2011;147:275–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sato T, van Es JH, Snippert HJ, Stange DE, Vries RG, van den Born M, et al. Paneth cells constitute the niche for Lgr5 stem cells in intestinal crypts. Nature 2011;469:415–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ganesh K, Basnet H, Kaygusuz Y, Laughney AM, He L, Sharma R, et al. L1CAM defines the regenerative origin of metastasis-initiating cells in colorectal cancer. Nat Cancer 2020;1:28–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Er EE, Valiente M, Ganesh K, Zou Y, Agrawal S, Hu J, et al. Pericyte-like spreading by disseminated cancer cells activates YAP and MRTF for metastatic colonization. Nat Cell Biol 2018;20:966–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cheung P, Xiol J, Dill MT, Yuan WC, Panero R, Roper J, et al. Regenerative reprogramming of the intestinal stem cell state via hippo signaling suppresses metastatic colorectal cancer. Cell Stem Cell 2020;27:590–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Guillermin O, Angelis N, Sidor CM, Ridgway R, Baulies A, Kucharska A, et al. Wnt and Src signals converge on YAP-TEAD to drive intestinal regeneration. EMBO J 2021;40:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bernal C, Silvano M, Tapponnier Y, Anand S, Angulo C, Ruiz i Altaba A. Functional pro-metastatic heterogeneity revealed by spiked-scRNAseq is shaped by cancer cell interactions and restricted by VSIG1. Cell Rep 2020;33:108372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Xu Z, Wang H, Gao L, Zhang H, Wang X. YAP levels combined with plasma CEA levels are prognostic biomarkers for early-clinical-stage patients of colorectal cancer. Biomed Res Int 2019;2019:2170830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yuen HF, McCrudden CM, Huang YH, Tham JM, Zhang X, Zeng Q, et al. TAZ expression as a prognostic indicator in colorectal cancer. PLoS One 2013;8:e54211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kiefel H, Bondong S, Hazin J, Ridinger J, Schirmer U, Riedle S, et al. L1CAM: A major driver for tumor cell invasion and motility. Cell Adhes Migr 2012;6:374–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Laughney AM, Hu J, Campbell NR, Bakhoum SF, Setty M, Lavallée VP, et al. Regenerative lineages and immune-mediated pruning in lung cancer metastasis. Nat Med 2020;26:259–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The sc- and bulk RNA-seq data generated in this study are publicly available in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) at GSE189987 and GSE193248, respectively.