Abstract

Cancer cells have acquired several pathways to escape from host immunity in the tumor microenvironment. Programmed death 1 (PD-1) receptor and its ligand PD-L1 are involved in the key pathway of tumor immune escape, and immune checkpoint therapy targeting PD-1 and PD-L1 has been approved for the treatment of patients with certain types of malignancies. Although PD-1 is a well-characterized receptor on T cells, the immune checkpoint receptor is also expressed on tumor-associated macrophages (TAM), a major immune component of the tumor microenvironment. In this study, we found significant diurnal oscillation in the number of PD-1–expressing TAMs collected from B16/BL6 melanoma-bearing mice. The levels of Pdcd1 mRNA, encoding PD-1, in TAMs also fluctuated in a diurnal manner. Luciferase reporter and bioluminescence imaging analyses revealed that a NF-κB response element in the upstream region of the Pdcd1 gene is responsible for its diurnal expression. A circadian regulatory component, DEC2, whose expression in TAMs exhibited diurnal oscillation, periodically suppressed NF-κB–induced transactivation of the Pdcd1 gene, resulting in diurnal expression of PD-1 in TAMs. Furthermore, the antitumor efficacy of BMS-1, a small molecule inhibitor of PD-1/PD-L1, was enhanced by administering it at the time of day when PD-1 expression increased on TAMs. These findings suggest that identification of the diurnal expression of PD-1 on TAMs is useful for selecting the most appropriate time of day to administer PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors.

Implications:

Selecting the most appropriate dosing time of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors may aid in developing cancer immunotherapy with higher efficacy.

Introduction

Tumor tissue is composed of not only cancer cells, but also numerous noncancer cells such as fibroblasts, epithelial cells, lymphocytes, macrophages, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells. The tumor microenvironment is also associated with the extracellular matrix, growth factors, and cytokines, and supports tumor growth and resistance to chemotherapy (1). Although immune cells infiltrate tumor tissue to eliminate cancer cells, there are several pathways through the tumor microenvironment to escape host immunity. One of the most important components in this pathway is an immunosuppressive co-signal (immune checkpoint) mediated by programmed death 1 (PD-1) receptor and its ligand PD-L1 (2). PD-L1 binds to PD-1 receptor expressed on T cells and tumor-associated macrophages (TAM), preventing their antitumor activities through the induction of exhaustion and apoptosis (3, 4).

Among tumor-infiltrating cells, TAMs are one of the most abundant immune components and are closely associated with the poor prognosis of patients with solid tumors (5). Macrophages exhibit highly flexible phenotypes depending on their microenvironment, with pro-inflammatory macrophages and anti-inflammatory macrophages referred to as M1 and M2 macrophages, respectively (6, 7). TAMs are mainly polarized into M2 macrophages, which have an anti-inflammatory phenotype and promote immunosuppressive conditions of the tumor microenvironment through the expression of immunosuppressive molecules (8).

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction are employed in immunotherapy against advanced cancers such as melanoma, renal cancer, and lung cancer (9–11). Although they have long-term, potentially clinical benefits, only a few patients (20%–30%) are estimated to have a positive response to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade therapy (12), and primary or acquired resistance may lead to tumor progression in patients with a clinical response (13). In addition, ICIs lead to the emergence of novel toxic features, known as immune-related adverse events, such as pneumonitis, hepatitis, and neurotoxic effects (14, 15). Although severe immune-related adverse events are rare, they are a limiting factor of ICIs treatment because they are life-threatening without intervention and proper management.

One approach for increasing the efficacy of pharmacotherapy or reducing the adverse effects is to administer drugs at the time of day when they are most effective and/or best tolerated. In experimental chronopharmacology studies and multicenter randomized trials, diurnal variation of the target protein affects the effects of drugs and/or their toxicity (16–18). Daily variations in biological functions are governed by an internal self-sustained molecular oscillator referred to as the circadian clock (19). The circadian clock comprises several clock genes such as Arntl (also known as Bmal1), Clock, Period (Per), and Cryptochrome (Cry). CLOCK and BMAL1 act in the form of a heterodimer and activate the transcription of Per and Cry genes, and increases in PER and CRY proteins suppress CLOCK/BMAL1-mediated transactivation. The activation and suppression of CLOCK/BMAL1 and PER/CRY, which alternates in approximately 24-hour cycles, generate the periodic activation and repression of clock-controlled genes.

During tumor growth, cells constituting the tumor microenvironment are often restricted to be provided nutrients and oxygen. Most solid tumors indeed have hypoxia regions caused by aberrant vascularization and poor blood supply (20). The hypoxic response induces the stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 subunit alpha (Hif1α), and subsequent increase in the expression of Dec1 and Dec2 (21). Because Dec1 and Dec2 also act as the components of molecular circadian clock (22), the hypoxia-induced activation of Hif1α–Dec1 axis interfere with the circadian clock machinery in tumor cells (20).

The cellular function of macrophages is also under the control of the circadian clock; therefore, macrophages exhibit diurnal changes in immune responses (23, 24). Under homeostatic conditions, macrophages rhythmically express ∼1,400 genes (23), of which a significant portion have immune function. Disruption of the clock machinery causes the dysfunction of macrophages, followed by disorders, such as cancers, diabetes, and hepatitis (24–27), suggesting that the macrophagic circadian clock is closely related to the promotion of pathologies.

During the analysis of the circadian characteristics of tumor immune function, we noted significant diurnal oscillation in the number of PD-1–expressing TAMs collected from B16/BL6 melanoma-bearing mice. The molecular circadian clock governing the rhythmic fluctuation in NF-κB–induced transactivation of the Pdcd1 gene, thereby leading to diurnal oscillation of PD-1 expression in TAMs. Therefore, we investigated the relevance of the rhythmic expression of PD-1 on TAMs for PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor–induced antitumor activity in tumor-bearing mice.

Materials and Methods

Cell and treatment

RAW264.7 macrophage-like cells (RRID:CVCL_0493) were purchased from ATCC. B16/BL6 melanoma (RRID:CVCL_0157) and NIH3T3 fibroblasts (RRID:CVCL_0594) were purchased from Cell Resource Center for Biomedical Research (Tohoku University). RAW264.7 cells and NIH3T3 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS and 0.5% penicillin–streptomycin solution (Invitrogen; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, California). B16/BL6 cells were cultured in RPMI1640 supplemented with 5% FBS (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Maryland) and 0.5% penicillin–streptomycin solution (Invitrogen). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. We confirmed the absence of microbes in these cell lines using a TaKaRa PCR Mycoplasma Detection Set. Cell lines were authenticated by each cell bank using short tandem repeat– PCR analysis, and these cell lines were used within 6 months from frozen stocks. To synchronize the cellular circadian clock, RAW264.7 cells were treated with 100 nmol/L dexamethasone (DEX) for 2 hours. Control cells were also set without treatment with DEX. The cells were washed with DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS and 0.5% penicillin and streptomycin, and then incubated in the medium at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. RNA and protein samples were prepared from circadian clock-synchronized cells every 4 hours after DEX treatment.

Construction of dec2 knockdown RAW264.7 cells

Mock and Dec2 shRNA lentivirus particles (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, California), and 10 µg/mL of polybrene were added to the media of RAW264.7 cells, and then incubated for 24 hours. Dec2 shRNA-transduced cells were selected with 1 µg/mL of puromycin.

Construction of cflar knockdown B16/BL6 cells

miRNA expression vectors were constructed using a BLOCK-iT Pol II miRNA-Expression Vector Kit with EmGFP (Invitrogen; Life Technologies). The miRNA oligonucleotide against the Cflar gene (anti-Cflar miRNA) was annealed at 95°C for 4 minutes and then ligated to the linear pcDNA 6.2-GW/EmGFP-miR vector. The annealed oligonucleotide sequences of anti-Cflar are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Constructed vectors were transfected into B16/BL6 cells using Lipofectamine LTX & PLUS reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts). miRNA-expressing cells were selected with blasticidin S (Wako Chemicals, Osaka, Japan), and individual colonies were then expanded and maintained in media containing 10 µg/mL of blasticidin S.

Construction of mEGFP-expressing B16/BL6 cells

mEGFP-C1 plasmid was gifted from Michael Davidson (RRID:Addgene_54759). The sequence of mEGFP was subcloned into pLVSIN-CMV Pur (Takara). Lentivirus particles were prepared by the Lentiviral High Titer Packaging Mix with pLVSIN series (Clonetech, Palo Alto, California) using Lenti-X 293 T-cell lines. mEGFP-expressing lentivirus particles and 10 µg/mL of polybrene were added to the media of B16/BL6 cells, and then incubated for 24 hours. mEGFP-transduced cells were selected with 1 µg/mL of puromycin.

Coculture assay

mEGFP-expressing B16/BL6 cells were seeded on 6-well culture plates at 1×106 per well and incubated for 12 hours. Medium was replaced with serum-free RPMI containing 1×106 mock or DEC2-KD RAW263.7 macrophages. Cells were treated with 10 µmol/L BMS-1, a small-molecule PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor (19914, Cayman Chemical, Ann Abor, Michigan) or vehicle (0.2% DMSO) for 24 hours. After treatment, cells were collected and preincubated in a 1:50 dilution of Fc block (BioLegend) in Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) containing 0.5% BSA and 2 mmol/L EDTA for 10 minutes on ice. This was followed by a 1-hour incubation with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-mouse/human CD11b antibody (BioLegend). Samples were acquired on a BD FACSAria III Cell Sorter with FACSDiva software v6.1.3 and analyzed using FlowJo software (RRID:SCR_008520).

Animals and treatments

Male C57BL/6J mice were housed in groups (from 6 to 8 per cage) in a light-controlled room (ZT, zeitgeber time; ZT0, lights on, ZT12, lights off) at 24±1°C, with humidity at 60±10%, and food and water ad libitum. B16/BL6 (1 × 104 cells) or Cflar knockdown (KD) B16/BL6 (1 × 105 cells) suspended in 50 µL of 50% Matrigel (Corning)/PBS (1:1) were implanted subcutaneously into the back of 5-week-old C57BL/6J mice under isoflurane anesthesia. Cflar-KD B16/BL6-implanted mice were intratumorally injected with a single daily dose of 50 µg of the PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor BMS-1 (19914, Cayman Chemical) or vehicle (PBS containing 10% DMSO) at ZT6 or ZT18. The injection of drugs was initiated on day 9 after cancer implantation. All protocols using mice were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Kyushu University. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Tumor specimens were dissociated in RPMI1640 supplemented with 25 mmol/L HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.4), 0.1% DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.1% collagenase type 4 (Worthingtong Biochemical Corporation, Freeway, New Jersey). Residual red blood cells were lysed with red blood cell lysis buffer (150 mmol/L NH4Cl, 10 mmol/L NaHCO3, and 1.25 mmol/L EDTA). In order to stain CD8+ T cells, single-cell pellets were preincubated in a 1:50 dilution of Fc block (BioLegend, San Diego, California) in HBSS (5.4 mmol/L KCl, 0.44 mmol/L KH2PO4, 137 mmol/L NaCl, 0.34 mmol/L Na2HPO4, and 5.55 mmol/L D-Glucose) containing 0.5% BSA and 2 mmol/L EDTA for 10 minutes on ice. This was followed by a 1-hour incubation with phycoerythrin anti-mouse CD8a antibodies (BioLegend, RRID:AB_312747), FITC anti-mouse CD3 antibodies (BioLegend, RRID:AB_312661), APC anti-mouse CD279 (PD-1) antibodies (BioLegend, RRID:AB_10612938), and PerCP anti-mouse CD45 antibodies (BioLegend, RRID:AB_893339). Cells were washed twice with HBSS containing 0.5% BSA and 2 mmol/L EDTA. For staining TAMs, single-cell pellets were resuspended in PBS supplemented with 0.5% BSA and 2 mmol/L EDTA, and added to anti-F4/80 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotechnology, Auburn, California, RRID:AB_2858241). F4/80+ macrophages were isolated using a magnetic-activated cell-sorting column (Miltenyi Biotechnology, Gladbach, Germany). The cells were preincubated in a 1:50 dilution of Fc block (BioLegend, RRID:AB_1574975) in HBSS containing 0.5% BSA and 2 mmol/L EDTA for 10 minutes on ice. This was followed by a 1-hour incubation with phycoerythrin anti-mouse/human CD11b antibodies (BioLegend, RRID:AB_312791), FITC anti-mouse CD206 (MMR) antibodies (BioLegend, RRID:AB_10900988), and APC anti-mouse CD279 (PD-1) antibodies (BioLegend). Cells were washed twice with HBSS containing 0.5% BSA and 2 mmol/L EDTA. Blood was hemolyzed with red blood cell lysis buffer. The white blood cells were preincubated in a 1:50 dilution of Fc block in 0.5% BSA and 2 mmol/L EDTA containing HBSS for 10 minutes on ice, and then stained with phycoerythrin anti-mouse/human CD11b and FITC anti-mouse F4/80 antibodies. Cells were washed twice with HBSS containing 0.5% BSA and 2 mmol/L EDTA. Samples were acquired on a BD FACSAria III Cell Sorter (Becton Dickinson Biosciences, San Diego, California) with FACSDiva software v6.1.3 and analyzed using FlowJo software (Becton Dickinson Biosciences). Gating strategies for TAMs and CD8+ T cells are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1

Preparation of primary culture of TAMs

F4/80+ macrophages were isolated from tumor masses using a magnetic-activated cell sorting. Isolated TAMs were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS and 0.5% penicillin and streptomycin, and then incubated in the medium at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. To synchronization of cellular circadian clock, cells were treated with DEX for 2 hours, and collected RNA every 4 hours from 28 to 48 hours after DEX treatment.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted using ReliaPrep RNA mini prep systems (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin) or RNAiso (Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was synthesized using a ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Kit (Toyobo Life Science, Osaka, Japan). The cDNA was amplified by PCR using a light cycler 96 (Nippon Genetics, Tokyo, Japan). Data were normalized using 18S ribosomal RNA as a control. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Western blotting

Nuclear and cytosolic fractions from RAW264.7 cells were prepared by centrifugation (28). Total protein was extracted using lysis buffer [20 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% Deoxycholic acid, and 2 mmol/L EDTA). The extracts were centrifuged at 15,000 g at 4°C for 10 minutes and the supernatant was collected. Obtained protein extracts were mixed with 2×sample buffer and denatured at 95°C for 5 minutes. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Membranes were reacted with antibodies against DEC2 (12688–1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China, RRID:AB_2065361), β-ACTIN conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (sc-47778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, RRID:AB_2714189), p65 (ab16502, Abcam, Cambridge, Massachusetts), and p84 (10920–1-AP, Proteintech, RRID:AB_2202239). Specific antigen–antibody complexes were visualized using HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (ab97051, Abcam, RRID:AB_10679369) and ImmunoStar LD (Wako Chemicals). Visualized images were scanned using an ImageQuant LAS4000 (GE Healthcare, Chalfont, United Kingdom).

Construction of the luciferase reporter vector

Genomic DNA was extracted from RAW264.7 cells. The promoter region of the mouse Pdcd1 gene, encoding PD-1, spanning from –2050 or –1540 or –913 to +63 bp was amplified by PrimeSTAR MAX DNA polymerase (R045A, Takara), and the products were ligated into the pGL4.18 luciferase reporter vector (Promega) using DNA ligation reagents (Nippon Gene). Primer sets for amplification of the upstream region of mouse Pdcd1 are listed in Supplementary Table S3.

Luciferase reporter assay

RAW264.7 cells were seeded on 24-well culture plates at 2×105 per well. Cells were transfected with 100 ng of Pdcd1(–2050/+63)::Luc, Pdcd1(–1540/+63)::Luc, Pdcd1(–913/+63)::Luc or pNF-κB:luc (Stratagene), and 400 ng (total) of expression vectors. The pcDNA3.1 empty vector was added to adjust the total amount of DNA in all transfections. A total of 10 ng of phRL-TK vector (Promega) was also transfected as an internal control reporter. Cells were harvested 24 hours after transfection and lysates were analyzed using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). The ratio of firefly to renilla luciferase activity in each sample served as a measure of normalized luciferase activity.

Real-time monitoring of circadian bioluminescence

NIH3T3 cells were transfected with Pdcd1(–2050/+63)::Luc, Pdcd1(–1540/+63)::Luc, or Pdcd1(–913/+63)::Luc. Thereafter, cells were stimulated with 100 nmol/L DEX for 2 hours to synchronize their circadian clocks. Bioluminescence from Pdcd1(–2050/+63)::Luc-, Pdcd1(–1540/+63)::Luc-, or Pdcd1(–913/+63)::Luc-transfected cells was recorded using a real-time monitoring system (Lumicycle, Actimetrics, Wilmette, Illinois), and the amplitude was calculated using Lumicycle analysis software (Actimetrics).

Immunofluorescence histochemical staining

B16/BL6 melanoma tumor masses were removed from mice and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. The fixed tumor masses were sliced into 12-µm sections using Cryostar NX70 (Thermo Scientific). The sections were blocked in solution containing 10% FBS and 0.1% Triton X-100 for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by incubation with antibody against F4/80 (BioRad, Hercules, California) at 4°C for 12 hours. After washing, sections were incubated with a fluorescent secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 555, Abcam) at room temperature for 4 hours. The sections were mounted using Vectashield hard-set mounting medium with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, California). Visualized images were obtained using a BZ-9000 instrument (Keyence, Osaka, Japan).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using JMP pro 14 software (SAS Institute Japan). All data were checked the normality and equal variances before performing ANOVA. The statistical significance of the circadian variations was assessed by one-way ANOVA. The comparison of multiple groups was assessed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer post hoc test. The comparison of data between two groups was tested by unpaired t test. It was considered to be significant if P value was <0.05.

Results

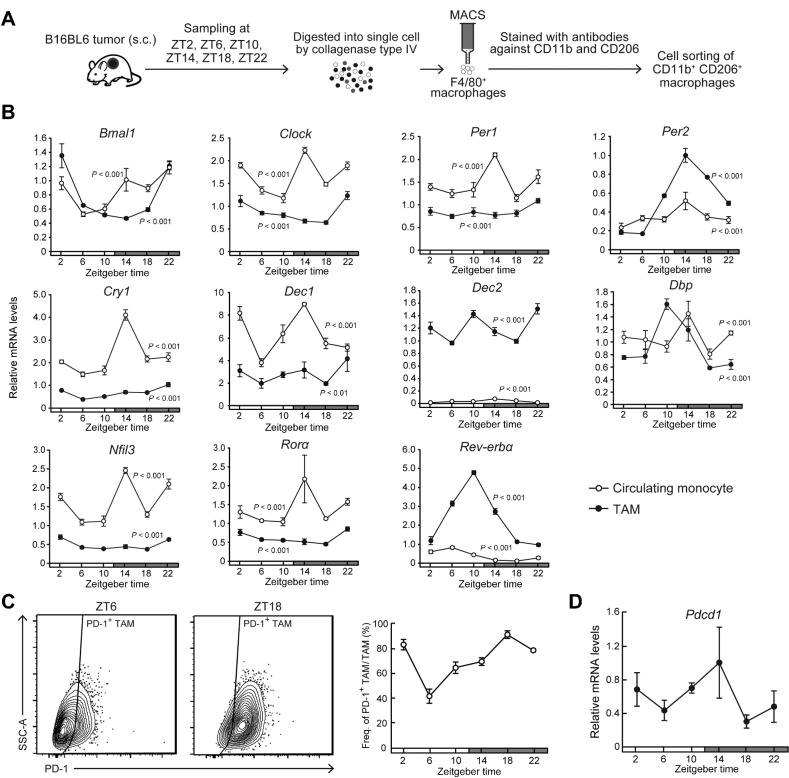

Circadian clock machinery functions in TAMs

To investigate whether the circadian clock machinery is functional in TAMs, we assessed the temporal expression profiles of clock genes in TAMs and circulating monocytes in blood. Two weeks after the implantation of B16/BL6 cells into subcutaneous tissue in the back region in C57BL/6J mice, tumor masses were removed at six different time points and single-cell suspensions were prepared. Circulating monocytes were also prepared from blood after hemolysis. F4/80+/ CD11b+/CD206+ cells were isolated as TAMs using magnetic-activated cell sorting and FACS (Fig. 1A). The mRNA levels of clock genes exhibited significant diurnal oscillations in both TAMs and circulating monocytes, but the expression levels of several clock genes in TAMs were significantly different from those in circulating monocytes (Fig. 1B). The expression levels of Per2, Dec2, and Rev-erbα increased in TAMs, whereas Clock, Per1, Cry1, Dec1, Nfil3, and Rorα mRNA levels in TAMs decreased compared with those in circulating monocytes. Although the PD-1–expressing monocytes were undetectable in circulating blood, FACS analysis revealed that the number of PD-1–expressing TAMs increased in a diurnal manner (P < 0.01; Fig. 1C). The levels of Pdcd1 mRNA, encoding PD-1 protein, in TAMs also showed significant diurnal oscillation (P < 0.05; Fig. 1D). The oscillation in the number of PD-1–expressing TAMs was delayed by approximately 4 hours relative to the Pdcd1 mRNA rhythm. This suggests that the expression of Pcdc1 gene in TAMs is under the control of circadian clock machinery.

Figure 1.

Diurnal variations in the population rate of PD-1–expressing TAMs in mouse B16/BL6 melanoma-forming tumor masses. A, Schematic depicting the isolation method of TAMs from mouse B16/BL6 melanoma-forming tumor masses. B, Temporal mRNA expression profiles of Bmal1, Clock, Per1, Per2, Cry1, Dec1, Dec2, Dbp, Nfil3, Rorα, and Rev-erbα in TAMs and circulating monocytes. Data were normalized by 18S rRNA levels. Values are the mean with SD (n = 3). There were significant time-dependent variations in the mRNA levels of all circadian clock gene in both TAMs and circulating monocytes (P < 0.01, respectively; one-way ANOVA). C, The left diagrams show the representative proportion of PD-1+ TAMs collected at ZT6 and ZT18. Right panel shows temporal profiles of the population of PD-1–expressing F4/80+ CD11b+ CD206+ TAMs. Values are the mean with SD (n = 3). There was a significant time-dependent variation in the population of PD-1–expressing TAMs. (F5,12 = 63.251, P < 0.001; one-way ANOVA). D, Temporal expression profile of Pdcd1 mRNA in TAMs. Data were normalized by 18S rRNA levels. Values are the mean with SD (n = 3). There was a significant time-dependent variation in Pdcd1 mRNA levels (F5,12 = 4.167, P = 0.020; one-way ANOVA). The horizontal bar at the bottom of each panel indicates light and dark cycles.

DEC2 regulates the circadian expression of Pcdc1.

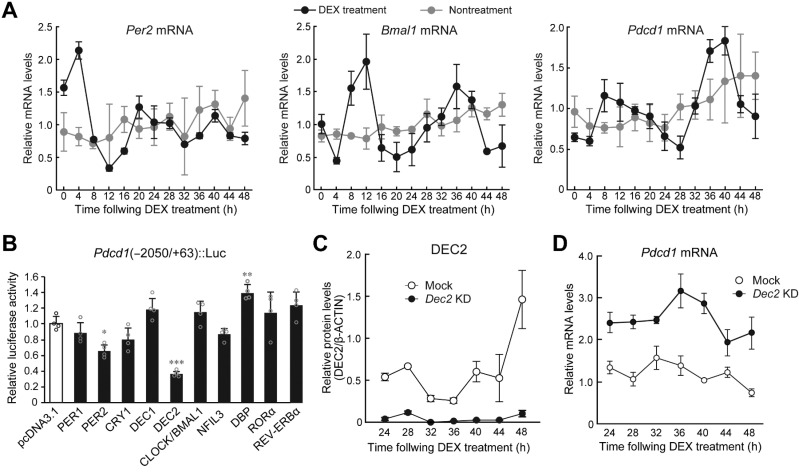

Next, we investigated whether molecular components of the circadian clock regulate the expression of Pdcd1. To prepare primary culture of TAMs, F4/80+ macrophages were isolated from tumor masses using a magnetic-activated cell sorting, and then treated with 100 nmol/L DEX to synchronize the circadian clock (29). The mRNA levels of Per2 and Bmal1 in primary culture of TAMs exhibited significant 24-hour oscillation after DEX treatment (Supplementary Fig. S2). In the circadian clock-synchronized TAMs, Pdcd1 mRNA also showed 24-hour oscillation (Supplementary Fig. S2), suggesting that rhythmic expression of Pdcd1 in TAMs is caused by cell-autonomous clock machinery. Because it was hard to prepare a sufficient number of TAMs for analyzing molecular circadian system, we also used murine macrophage-like cell line RAW264.7 to investigate the underlying mechanism of diurnal expression of Pdcd1. After treatment of RAW264.7 with 100 nmol/L DEX, the mRNA levels of Per2, Bmal1, and Pdcd1 also exhibited significant 24-hour oscillations (Fig. 2A). As circadian clock nonsynchronized cells failed to show significant 24-hour oscillation of mRNA levels of clock gene and Pdcd1, rhythmic expression of Pdcd1 in RAW264.7 cells also appeared to be governed by cell-autonomous clock machinery.

Figure 2.

DEC2 regulates the circadian expression of Pdcd1 mRNA in macrophages. A, Temporal mRNA expression profiles of Per2, Bmal1, and Pdcd1 in RAW264.7 cells, whose circadian clocks were synchronized by treatment with 100 nmol/L DEX for 2 hours. Nontreatment cells were set as a nonsynchronized control. Data were normalized by the levels of 18S rRNA and the mean of each group was set at 1.0. Values are the mean with SD (n = 3). There were significant time-dependent variations in Per2, Bmal1, and Pdcd1 in DEX treatment group (F12, 26 = 53.225, P < 0.001 for Per2; F12, 26 = 12.609, P < 0.001 for Bmal1; F12, 26 = 18.874, P < 0.001 for Pdcd1; one-way ANOVA). B, DEC2 negatively regulates the transcription of the Pdcd1 gene. RAW264.7 cells were cotransfected with Pdcd1(-2050/+63)::Luc, and expression vectors for PER1, PER2, CRY1, DEC1, DEC2, CLOCK/BMAL1, NFIL3, DBP, RORα, and REV-ERBα. The values are the mean with SD (n = 3). The value of empty vector (pcDNA3.1)-transfected RAW264.7 cells was set at 1.0. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; significant difference from empty vector (pcDNA3.1)-transfected groups (F10,33 = 18.109, P < 0.001; ANOVA with the Tukey Kramer post hoc test). C, Temporal expression profiles of DEC2 protein in mock-transduced and Dec2 KD RAW264.7 cells, whose circadian clocks were synchronized by treatment with 100 nmol/L DEX. Data were normalized by the β-ACTIN levels. Values are the mean with SD (n = 3). (F1, 28 = 216.110, P < 0.01 for group; F6,28 = 17.930, P < 0.01 for time point; F6,28 = 12.966, P < 0.01 for time point×group; two-way ANOVA). D, Temporal expression profiles of Pdcd1 mRNA in mock-transduced and Dec2 KD RAW264.7 cells, whose circadian clocks were synchronized by treatment with 100 nmol/L DEX. Data were normalized by the levels of 18S rRNA. Values are the mean with SD (n = 3). (F1,28 = 323.663, P < 0.01 for group; F6,28 = 8.459, P = 0.016 for time point; F6,28 = 4.890, P < 0.01 for time point×group; two-way ANOVA).

As several DNA sequences homologous with clock gene response elements, E-box, D-site, and retinoic orphan receptor (ROR) response elements, are located in the upstream region of mouse Pdcd1 gene, we focused on these response elements and performed transient transcription assays by constructing luciferase reporter vectors containing the upstream region of the mouse Pdcd1 gene spanning from –2050 to +63 bp (relative to the transcription start site, +1). The reporter constructs of Pdcd1 (–2050/+63)::Luc were cotransfected with expression vectors encoding PER1, PER2, CLOCK/BMAL1, CRY1, DEC1, DEC2, RORα, REV-ERBα, DBP, and NFIL3 (Fig. 2B). The transcriptional activity of Pdcd1 (–2050/+63)::Luc was significantly repressed by PER2 and DEC2 (P < 0.05 for PER2; P < 0.001 for DEC2, respectively) and increased by DBP (P < 0.01), but was unaffected by PER1, CRY1, CLOCK/BMAL1, NFIL3, RORα, and REV-ERBα (Fig. 2B). Dec2 was upregulated in TAMs and suppressed the transcriptional activity of Pdcd1 (–2050/+63)::Luc. Furthermore, the protein levels of DEC2 in TAMs isolated from B16BL6 tumor masses increased at the trough time of Pdcd1 mRNA expression (Supplementary Fig. S3A), suggesting that DEC2 acts as a circadian repressor of Pdcd1 expression in TAMs. To investigate the circadian role of DEC2 in more detail, we prepared stable Dec2 KD RAW264.7 cells using a lentiviral system. Mock-transduced RAW264.7 cells exhibited significant 24-hour oscillation of DEC2 protein after DEX treatment, but transduction of shRNA against Dec2 reduced the levels of protein and mRNA throughout all examined time points (Fig. 2C; Supplementary Fig. S3B). Under this condition, the Pdcd1 mRNA levels were constitutively increased in Dec2 KD RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 2D), suggesting that DEC2 represses the expression of Pdcd1 by acting on the DNA sequence between –2050 to +63 bp.

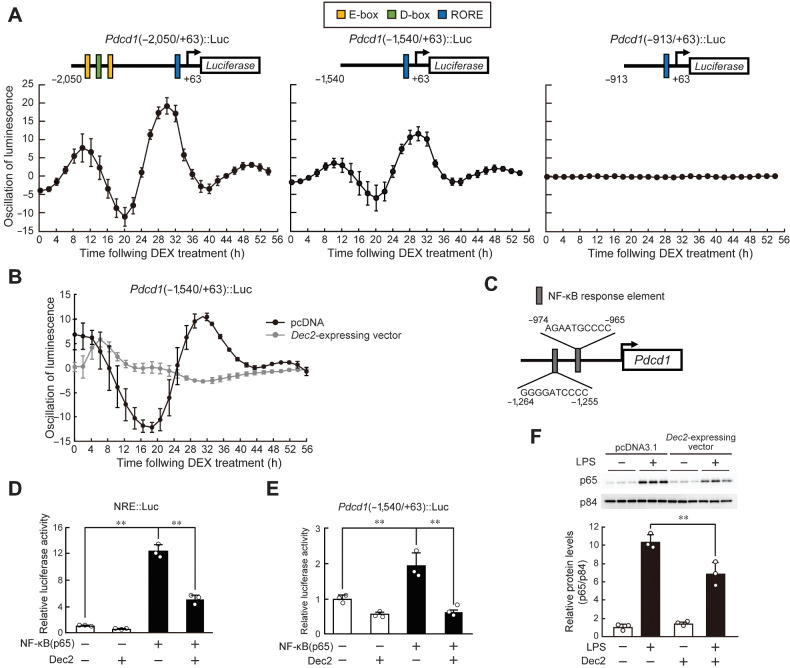

DEC2 suppresses the transcription of Pcdc1 through inhibition of the nuclear translocation of p65

To explore the underlying mechanism of DEC2-regulated circadian Pdcd1 expression, we searched for regions responsible for generating 24-hour expression of Pdcd1. The reporter constructs of Pdcd1 (–2050/+63)::Luc, (–1540/+63)::Luc, or (–913/+63)::Luc were transfected into NIH3T3 cells, and their circadian clock was synchronized by treatment with 100 nmol/L DEX for 2 hours. RAW264.7 cells rapidly growth and their viability was gradually decreased during the assessment of circadian bioluminescence. Therefore, NIH3T3 cells were used in this experiment instead of RAW264.7. Bioluminescence oscillated with a period length of approximately 24 hours in cells transfected with Pdcd1 (–2050/+63)::Luc or Pdcd1 (–1540/+63)::Luc, but no significant bioluminescence oscillation was detected in cells transfected with Pdcd1 (–913/+63)::Luc (Fig. 3A). The oscillated bioluminescence of Pdcd1 (–1540/+63)::Luc was repressed by transfection with Dec2-expressing vector (Fig. 3B). Although this suggested that the upstream region of the mouse Pdcd1 gene from –1540 to –913 bp contains elements responsible for its circadian expression, computer-aided analysis of this region revealed no consensus DNA sequence of clock gene response elements.

Figure 3.

Repression of NF-κB–mediated transactivation by DEC2 underlies the circadian expression of Pdcd1. A, Bioluminescence profiles driven by Pdcd1(-2050/+63)::Luc-, Pdcd1(-1540/+63)::Luc-, and Pdcd1(-913/+63)::Luc-transfected NIH3T3 cells after treatment with 100 nmol/L DEX for 2 hours. The upper schematic diagrams show luciferase reporter constructs containing different lengths of the upstream region of the mouse Pdcd1 gene. Closed boxes indicate the sites homologous with clock gene response elements and the numbers of nucleotide residues indicate the distance from the transcription start site (+1). Values are the mean with SD (n = 6–8). B, Bioluminescence profiles driven by Pdcd1(-1540/+63)::Luc in circadian clock-synchronized NIH3T3 cells transfected with Dec2-expressing vectors or control (pcDNA) vectors. C, Location of the NRE in the upstream region of the mouse Pdcd1 gene. D, Suppression of p65-mediated transactivation of the NRE::Luc by DEC2. RAW264.7 cells were cotransfected with NRE::Luc, and expression vectors for p65 and DEC2. Values are the mean with SD (n = 3). The value of empty vector (pcDNA3.1)-transfected RAW264.7 cells was set at 1.0. **, P < 0.01; significant difference between the two groups (F3,8 = 237.051, P < 0.001; one-way ANOVA with Tukey Kramer post hoc test). E, Suppression of p65-mediated transactivation of the Pdcd1 (–1540/+63)::Luc by DEC2. RAW264.7 cells were cotransfected with Pdcd1(–1540)::Luc, and expression vectors for p65 and DEC2. Values are the mean with SD (n = 3). The value of empty vector (pcDNA3.1)-transfected RAW264.7 cells was set at 1.0. **, P < 0.01; significant difference between the two groups (F3,8 = 29.215, P < 0.001; one-way ANOVA with Tukey Kramer post hoc test). F, Suppression of LPS-induced nuclear translocation of p65 by DEC2. RAW264.7 cells were transfected with empty vector (pcDNA3.1) or Dec2-expressing vector and then treated with 1 µg/mL of LPS for 30 minutes. **, P < 0.01; significant difference between the two groups (F3,8 = 96.447, P < 0.001; one-way ANOVA with Tukey Kramer post hoc test).

NF-κB plays an essential role in the inflammatory response (30). Recent studies demonstrated that NF-κB is also involved in the regulation of circadian gene expression (31, 32). A highly conserved NF-κB response element (NRE) was located from –1264 to –1255 bp and –974 to –965 bp upstream from the transcription start site of the mouse Pdcd1 gene (Fig. 3C). NRE sequences were also observed at a similar position in the human PDCD1 gene (Supplementary Fig. S4). Treatment of macrophages with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) activates p65, a component of NF-κB, through stimulation of TLR4 signaling and upregulates the expression of Pdcd1 (33). We investigated whether DEC2 represses the transcription of Pdcd1 by inhibiting NF-κB activity. The promotor activity of luciferase reporters containing consensus NRE (NRE::Luc) was significantly increased by p65, but the p65-mediated transactivation of NRE::Luc was suppressed by DEC2 (Fig. 3D). As observed in the case of NRE::Luc, the reporter activity of Pdcd1 (–1540/+63)::Luc was also increased by p65 and its transactivation was repressed by DEC2 (Fig. 3E). This suggests that DEC2 represses Pdcd1 expression by inhibiting NF-κB transcriptional activity. After inflammatory stimuli, such as LPS, p65 is translocated into the nucleus and forms dimers as part of the activation process (34). LPS-induced nuclear translocation of p65 in RAW264.7 cells was significantly prevented by DEC2 (Fig. 3F). Thus, DEC2 represses the p65-mediated transactivation of Pdcd1. The time-dependent repression of p65-mediated transactivation by DEC2 may cause the circadian expression of Pdcd1 in TAMs.

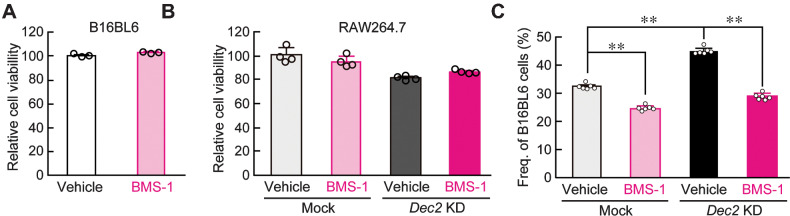

DEC2 regulates the antitumor effects of macrophages by regulating PD-1 expression.

It is well established that the blockade of PD-1/PD-L1 interactions promotes T cell–mediated antitumor effects (35). In addition, antitumor activity of TAMs is suppressed by the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway (36). As DEC2 negatively regulated the expression of PD-1 in RAW264.7 cells, we investigated whether DEC2 alters the pharmacologic effects of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors on the antitumor immunity of RAW264.7 macrophages. A small molecular PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor, BMS-1, was tested. Treatment of cultured B16/BL6 and RAW264.7 cells with 10 µmol/L BMS-1 for 24 hours had negligible effects on their viability (Fig. 4A and B). No significant change in the viability of Dec2 KD RAW264.7 cells was noted after treatment with 10 µmol/L BMS-1 (Fig. 4B). On the other hand, the concentration of BMS-1 significantly affected the viability of B16/BL6 melanoma when cells were cocultured with mock-transduced RAW264.7 macrophages (P < 0.01; Fig. 4C). The viability of B16/BL6 melanoma in coculture with mock-transduced RAW264.7 macrophages decreased by 24% after treatment with BMS-1. Under this coculture condition, downregulation of DEC2 in RAW264.7 cells increased the viability of B16/BL6 melanoma, but the higher viability of melanoma cells was also significantly suppressed by 10 µmol/L BMS-1 (P < 0.01). The viability of B16/BL6 melanoma in coculture with DEC2-KD RAW264.7 macrophages decreased by 38% after treatment with BMS-1. Thus, the ability of DEC2 to alter antitumor immunity of macrophages affects the pharmacologic effects of the PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor BMS-1.

Figure 4.

Regulation of antitumor immunity of RAW264.7 macrophages by DEC2. (A and B) The viability of B16/BL6 melanoma (A) and mock-transduced or Dec2 KD RAW264.7 cells (B) after treatment with 10 µmol/L BMS-1 for 24 hours. C, BMS-1 increases the antitumor immunity of RAW264.7 cells under coculture conditions. B16/BL6 melanoma was cocultured with mock-transduced or Dec2 KD RAW264.7 cells, and cells were treated with 10 µmol/L BMS-1 or vehicle (0.2% DMSO) for 24 hours. All experiments were conducted without synchronization of the circadian clock. Values are the mean with SD (n = 6). **, P < 0.01; significant difference between the two groups (F3,20 = 419.160, P < 0.001; one-way ANOVA with Tukey Kramer post hoc test).

Dosing time-dependent change in the antitumor effects of BMS-1.

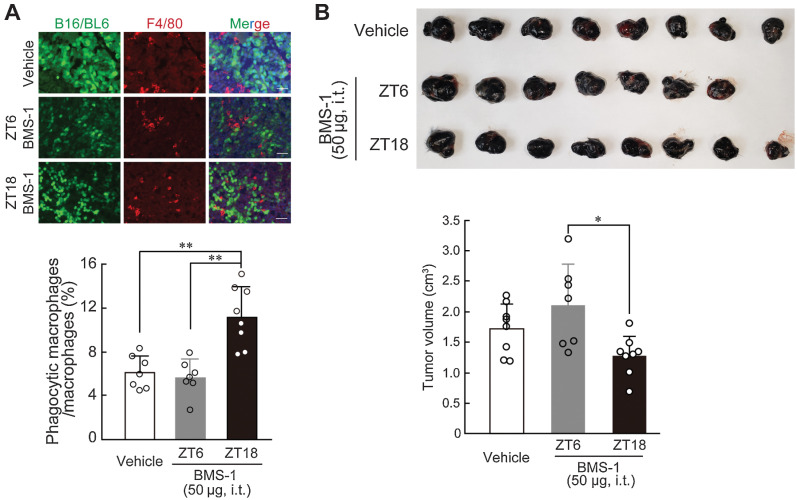

As the number of PD-1–expressing TAMs exhibited significant diurnal oscillation in B16/BL6 melanoma-implanted mice (Fig. 1C), we investigated whether the antitumor effects of BMS-1 in B16/BL6-bearing mice can be improved by optimizing the dosing time. B16/BL6 melanoma cells were reported to acquire resistance to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade (37), but a recent study reported that downregulation of the Cflar gene increases the PD-1 blockade efficacy in a melanoma tumor model (38). Therefore, we prepared Cflar KD B16/BL6 melanoma cells and implanted them into subcutaneous tissue of the back region in C57BL/6J mice. BMS-1 (50 µg) was intratumorally injected every day at ZT6 and ZT18; at these time points, the expression of PD-1 in TAMs decreased and increased, respectively (Fig. 1C). IHC analysis revealed that administration of BMS-1 at ZT18 significantly increased the phagocytic activity of TAMs (P < 0.01; Fig. 5A). Furthermore, tumor growth was significantly suppressed by the administration of BMS-1 at ZT18 compared with administration of the drug at ZT6 (P < 0.01; Fig. 5B). This suggests a link between circadian clock machinery in TAMs and the antitumor immune response in tumor microenvironment.

Figure 5.

Dosing time-dependent change in the ability of BMS-1 to inhibit the growth of B16/BL6 melanoma implanted in mice. A, Difference in the number of phagocytic macrophages in B16/BL6 tumor masses at 7 days after the initiation of BMS-1 administration at ZT6 and ZT18. Cflar KD B16/BL6 cells were implanted into subcutaneous tissue of the back region in C57BL/6J mice. From 9 days after implantation, mice were intratumorally (i.t.) injected with a single daily dose of BMS-1 (50 µg) or vehicle (10% DMSO in PBS) at ZT6 or ZT18. The left panel shows immunofluorescence labelling of F4/80 (red) in the GFP-expressing B16/BL6 (green) tumor masses. The scale bar indicates 50 µm. The phagocytic macrophages were manually counted in a blinded manner. Values are the mean with SD (n = 7–8). **, P < 0.01; significant difference between the two groups (F2,19 = 17.746, P < 0.001; one-way ANOVA with Tukey Kramer post hoc test). B, Difference in the volume of B16/BL6 melanoma-forming tumor cells at 7 days after the initiation of BMS-1 administration at ZT6 and ZT18. Values are the mean with SD (n = 7–8). *, P < 0.05; significant difference between the two groups (F2,20 = 5.271, P = 0.0145; one-way ANOVA with Tukey Kramer post hoc test). Upper photograph shows dissected tumor from B16/BL6 melanoma-implanted mice at 7 days after the initiation of BMS-1 administration at ZT6 and ZT18.

Discussion

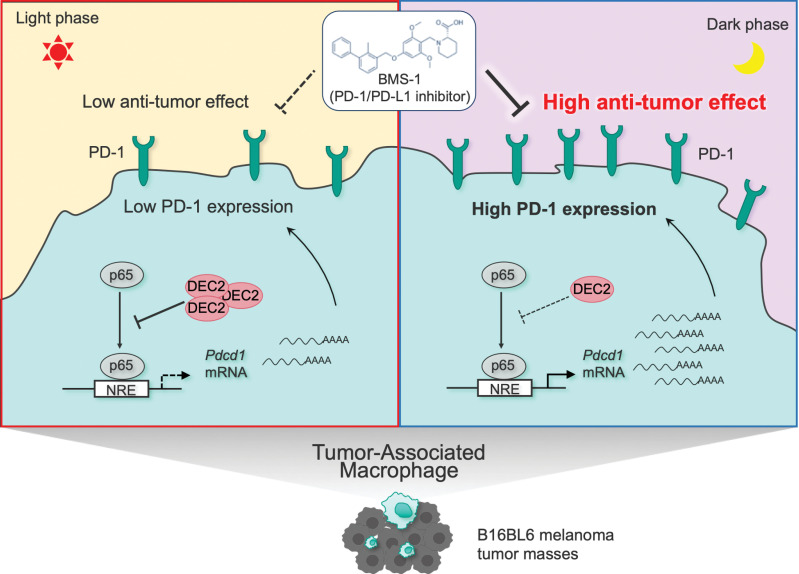

Although there have been many recent advances in our understanding of circadian control of the immune system, little is known about circadian changes in the function of tumor-infiltrating immune cells, including TAMs. In this study, we found that the expression of PD-1 exhibited significant diurnal oscillation on TAMs collected from mice B16/BL6 melanoma-forming tumor. The biochemical and molecular analysis revealed that DEC2 time-dependently repressed NF-κB–mediated transactivation of Pdcd1, thereby causing diurnal oscillation of PD-1 expression on TAMs (Fig. 6). Although in vitro pharmacologic study demonstrates that a RORγ agonist attenuates the expression of PD-1 on T cells, no significant diurnal variation was detected in the number of PD-1–expressing T cells in B16/BL6 melanoma-forming tumor tissue (Supplementary Fig. S5). The rhythmic expression of PD-1 on TAMs appears to underlie the dosing time-dependent change in the antitumor effects of the PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor BMS-1 in B16/BL6 melanoma-bearing mice, demonstrating the importance of the circadian clock in TAMs for cancer immunotherapy. This notion is also supported by recent findings that the effects of immune checkpoint inhibitor in patients with advanced melanoma vary according to administration time (39).

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram underlying mechanism of the dosing time-dependent changes in the antitumor effects of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor BMS-1 in B16BL6 melanoma-implanted mice. The time-dependent repression of p65-mediated transactivation of Pdcd1 by DEC2 induces the circadian expression of PD-1 in TAMs. The antitumor efficacy of BMS-1 is enhanced by administering at the time of day when PD-1 expression is increased on TAMs.

As a variety of immune cells with the capacity to reject cancer cells infiltrate into the tumor microenvironment, tumor tissue is often under pro-inflammatory conditions. PD-1 is expressed on the surface of tumor-infiltrating immune cells, including T cells, natural killer cells, and TAMs (36, 40). Macrophages are the largest population of immune cells in B16 melanoma-forming tumor tissues (41). The proportion of M2 macrophages among PD-1–expressing TAMs is higher than that of M1 macrophages in the tumor microenvironment (36). M2-polarized TAMs are known to induce immunosuppressive effects, especially limiting cytotoxic T-cell responses (42). Although NF-κB acts as an inducer of M1 polarization of macrophages, previous (33) and our present findings demonstrated that NF-κB signaling also activates Pdcd1 expression in TAMs. It has been suggested that upregulation of PD-1 expression promotes M2 polarization of macrophages by increasing the phosphorylation of STAT6 (43). Prolonged and excessive expression of PD-1 by NF-κB signaling may result in M2 polarization of TAMs.

In addition to NF-κB–mediated transactivation, the expression of PD-1 is regulated at the posttranslational level (44). FBXO38 is identified as a specific E3 ubiquitin ligase of PD-1 that regulates its proteasome degradation (44). FBXO38 is highly expressed in circulating T cells, but not in tumor-infiltrating T cells (44), supporting the notion that the ubiquitin ligase is involved in the regulation of the antitumor immunity of T cells. The expression of Fbxo38 in TAMs was significantly lower than that in circulating monocytes (Supplementary Fig. S6). A decrease in the levels of Fbxo38 may also increase the expression of PD-1 in TAMs. Downregulation of FBXO38 in tumor-infiltrating T cells is associated with IL2 receptor signaling (44). As the expression levels of IL2 receptor also decreased in M2 macrophages (45), it is possible that attenuated IL2 receptor signaling in TAMs increases the expression of PD-1 via the downregulation of FBXO38.

Accumulating evidence supports that many cellular functions of macrophages and monocytes are under the control of circadian clock machinery (23). Most downstream events of the macrophagic circadian clock are related to immune functions for host defense against bacterial pathogens, which exhibit diurnal variation (46). In this study, we demonstrated that the mRNA levels of clock genes exhibit significant diurnal expression not only in circulating monocytes, but also in TAMs, although the expression levels of several clock genes in TAMs were different from those observed in circulating monocytes. Among them, the expression of Dec2 and Rev-erbα significantly increased in TAMs. Although REV-ERBα acts as an anti-inflammatory molecule through inhibition of NF-κB activity (47), the bioluminescence rhythm of Pdcd1(–1540/+63)::Luc was damped by transfection of Dec2-expressing vector. Furthermore, downregulation of DEC2 in cultured macrophages increased the expression of Pdcd1 mRNA. These results suggests that DEC2 functions as the major regulator of Pdcd1 expression in macrophages. The time-dependent suppression of Pdcd1 expression by DEC2 may underlie the diurnal oscillation of PD-1 levels on TAMs.

Pro-inflammatory conditions in the tumor microenvironment are closely connected to all stages of cancer development, including initiation, promotion, and progression, but excessive inflammation induces apoptotic death of cancer cells (48). The proliferation of cancer cells implanted in mice exhibits diurnal rhythms, with a peak from the late light phase to the early dark phase (49), which is delayed by approximately 8 hours relative to the PD-1 expression rhythm of TAMs. As PD-1–expressing TAMs display the M2 phenotype of macrophages and support cancer cell proliferation by secreting growth factors, the time-dependent change in the number of PD-1–expressing TAMs may also play a role in the generation of the diurnal rhythm of proliferation of cancer cells in tumor tissues.

Anti–PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies have become the most widely prescribed cancer immunotherapy. However, immune-related adverse events sometimes cause damage and can be lethal in severe cases if not treated properly. Our present study suggested that the dosing time-dependent change in the antitumor effects of BMS-1 is, at least in part, due to the PD-1 expression rhythm on TAMs. On the other hand, a previous report (50) and analysis of the circadian expression profiles database also indicated that the expression of the Cd274 gene, encoding PD-L1, exhibits circadian oscillation, with a peak in the light period in the normal liver and lung of mice. The rhythmic phase of PD-L1 expression is nearly opposite to the PD-1 expression rhythm in TAMs, suggesting that administration of a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor during the dark phase can prevent or attenuate immune-related adverse events, but further studies are required to investigate the dosing time dependency of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor–induced immune-related adverse events.

As a variety of immune functions are under the control the circadian clock, alteration of the circadian machinery of immune cells leads to pathologic states (24). However, disruption of the circadian control of immune-cell functions in the tumor microenvironment by inhibiting PD-1/PD-L1 interactions will be detrimental to the growth of cancer cells. Therefore, selecting the most appropriate dosing time of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors may aid in developing cancer immunotherapy with maximized efficacy and minimal adverse events.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the technical assistance of The Research Support Center, Research Center for Human Disease Modeling, Kyushu University Graduate School of Medical Sciences. This study was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (20K21484, to A. Tsuruta) and Grant-in-Aid for Research Activity Start-up (19K23891, to A. Tsuruta). This study was also supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research A (16H02636, to S. Ohdo), Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Research (Pioneering) (21K18249, to S. Ohdo), Grant-in-Aid for Exploratory Research (20K21484, to S. Koyanagi), Grant-in-Aid for Exploratory Research (20K21901, to N. Matsunaga), and Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research [Basis for Supporting Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (BINDS)] from AMED under grant number JP21am0101091.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked advertisement in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Molecular Cancer Research Online (http://mcr.aacrjournals.org/).

Authors' Disclosures

No disclosures were reported.

Authors' Contributions

A. Tsuruta: Conceptualization, resources, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, funding acquisition, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing–original draft. Y. Shiiba: Conceptualization, resources, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, funding acquisition, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing–original draft. N. Matsunaga: Conceptualization, resources, data curation, software, formal analysis, supervision, validation, investigation, methodology, writing–original draft, project administration. M. Fujimoto: Methodology. Y. Yoshida: Methodology. S. Koyanagi: Supervision, project administration, writing–review and editing. S. Ohdo: Supervision, funding acquisition, writing–original draft, project administration, writing–review and editing.

References

- 1. Jin MZ, Jin WL. The updated landscape of tumor microenvironment and drug repurposing. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2020;5:166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Topalian SL, Taube JM, Anders RA, Pardoll DM. Mechanism-driven biomarkers to guide immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2016;16:275–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wherry EJ, Kurachi M. Molecular and cellular insights into T-cell exhaustion. Nat Rev Immunol 2015;15:486–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ishida Y, Agata Y, Shibahara K, Honjo T. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. EMBO J 1992;11:3887–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dehne N, Mora J, Namgaladze D, Weigert A, Brüne B. Cancer cell and macrophage cross-talk in the tumor microenvironment. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2017;35:12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, Allavena P, Sica A. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol 2002;23:549–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ostuni R, Kratochvill F, Murray PJ, Natoli G. Macrophages and cancer: from mechanisms to therapeutic implications. Trends Immunol 2015;36:229–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Bronte V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumors. Nat Rev Immunol 2012;12:253–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQM, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, et al. Safety and activity of anti–PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2455–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weber J, Mandala M, Del Vecchio M, Gogas HJ, Arance AM, Cowey CL, et al. Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage III or IV melanoma. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1824–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, George S, Hammers HJ, Srinivas S, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1803–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haslam A, Prasad V. Estimation of the percentage of US patients with cancer who are eligible for and respond to checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy drugs. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e192535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, Hodi FS, Hwu WJ, Kefford R, et al. Five-year survival outcomes for patients with advanced melanoma treated with pembrolizumab in KEYNOTE-001. Ann Oncol 2019;30:582–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Postow MA, Sidlow R, Hellmann MD. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med 2018;378:158–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martins F, Sofiya L, Sykiotis GP, Lamine F, Maillard M, Fraga M, et al. Adverse effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors: epidemiology, management, and surveillance. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2019;16:563–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matsunaga N, Ogino T, Hara Y, Tanaka T, Koyanagi S, Ohdo S. Optimized dosing schedule based on circadian dynamics of mouse breast cancer stem cells improves the antitumor effects of aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitor. Cancer Res 2018;78:3698–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Okazaki F, Matsunaga N, Okazaki H, Azuma H, Hamamura K, Tsuruta A, et al. Circadian clock in a mouse colon tumor regulates intracellular iron levels to promote tumor progression. J Biol Chem 2016;291:7017–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Koyanagi S, Kuramoto Y, Nakagawa H, Aramaki H, Ohdo S, Soeda S, et al. A molecular mechanism regulating circadian expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in tumor cells. Cancer Res 2003;63:7277–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rijo-Ferreira F, Takahashi JS. Genomics of circadian rhythms in health and disease. Genome Med 2019;11:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. O'Connell EJ, Martinez CA, Liang YG, Cistulli PA, Cook KM. Out of breath, out of time: interactions between HIF and circadian rhythms. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2020;319:C533–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miyazaki K, Kawamoto T, Tanimoto K, Nishiyama M, Honda H, Kato Y. Identification of functional hypoxia response elements in the promoter region of the DEC1 and DEC2 genes. J Biol Chem 2002;277:47014–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Honma S, Kawamoto T, Takagi Y, Fujimoto K, Sato F, Noshiro M, et al. Dec1 and Dec2 are regulators of the mammalian molecular clock. Nature 2002;419:841–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Keller M, Mazuch J, Abraham U, Eom GD, Herzog ED, Volk H-D, et al. A circadian clock in macrophages controls inflammatory immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009;106:21407–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nguyen KD, Fentress SJ, Qiu Y, Yun K, Cox JS, Chawla A. Circadian gene Bmal1 regulates diurnal oscillations of Ly6C(hi) inflammatory monocytes. Science 2013;341:1483–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xu H, Li H, Woo SL, Kim SM, Shende VR, Neuendorff N, et al. Myeloid cell–specific disruption of Period1 and Period2 exacerbates diet-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. J Biol Chem 2014;289:16374–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pourcet B, Zecchin M, Ferri L, Beauchamp J, Sitaula S, Billon C, et al. Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group D member 1 regulates circadian activity of NLRP3 inflammasome to reduce the severity of fulminant hepatitis in mice. Gastroenterology 2018;154:1449–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alexander RK, Liou Y-H, Knudsen NH, Starost KA, Xu C, Hyde AL, et al. Bmal1 integrates mitochondrial metabolism and macrophage activation. Elife 2020;9:1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Baghirova S, Hughes BG, Hendzel MJ, Schulz R. Sequential fractionation and isolation of subcellular proteins from tissue or cultured cells. MethodsX 2015;2:440–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Balsalobre Auré, Brown SA, Marcacci L, Tronche Franç, Kellendonk C, Reichardt HM, et al. Resetting of circadian time in peripheral tissues by glucocorticoid signaling. Science 2000;289:2344–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Taniguchi K, Karin M. NF-κB, inflammation, immunity, and cancer: coming of age. Nat Rev Immunol 2018;18:309–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tsurudome Y, Koyanagi S, Kanemitsu T, Katamune C, Oda M, Kanado Y, et al. Circadian clock component PERIOD2 regulates diurnal expression of Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor-1 and its scaffolding function. Sci Rep 2018;8:9072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Spengler ML, Kuropatwinski KK, Comas M, Gasparian AV, Fedtsova N, Gleiberman AS, et al. Core circadian protein CLOCK is a positive regulator of NF-κB–mediated transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012;109:E2457–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bally APR, Lu P, Tang Y, Austin JW, Scharer CD, Ahmed R, et al. NF-κB regulates PD-1 expression in macrophages. J Immunol 2015;194:4545–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yang F, Tang E, Guan K, Wang CY. IKK beta plays an essential role in the phosphorylation of RelA/p65 on serine 536 induced by lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol 2003;170:5630–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bronte V, Kasic T, Gri G, Gallana K, Borsellino G, Marigo I, et al. Boosting antitumor responses of T lymphocytes infiltrating human prostate cancers. J Exp Med 2005;201:1257–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gordon SR, Maute RL, Dulken BW, Hutter G, George BM, McCracken MN, et al. PD-1 expression by tumor-associated macrophages inhibits phagocytosis and tumor immunity. Nature 2017;545:495–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mosely SIS, Prime JE, Sainson RCA, Koopmann JO, Wang DYQ, Greenawalt DM, et al. Rational selection of syngeneic preclinical tumor models for immunotherapeutic drug discovery. Cancer Immunol Res 2017;5:29–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang Y, Li JJ, Ba HJ, Wang KF, Wen XZ, Li DD, et al. Down regulation of c-FLIPL enhance PD-1 blockade efficacy in B16 melanoma. Front Oncol 2019;9:857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. David CQ, Troy K, Brianna B, Karen MX, Jeffery MS, James RJ. Effect of immunotherapy time-of-day infusion on overall survival among patients with advanced melanoma in the USA (MEMOIR): a propensity score-matched analysis of a single-centre, longitudinal study. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:1777–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kumagai S, Togashi Y, Kamada T, Sugiyama E, Nishinakamura H, Takeuchi Y, et al. The PD-1 expression balance between effector and regulatory T cells predicts the clinical efficacy of PD-1 blockade therapies. Nat Immunol 2020;21:1346–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yu JW, Bhattacharya S, Yanamandra N, Kilian D, Shi H, Yadavilli S, et al. Tumor-immune profiling of murine syngeneic tumor models as a framework to guide mechanistic studies and predict therapy response in distinct tumor microenvironments. PLoS One 2018;13:e0206223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xiang X, Wang J, Lu D, Xu X. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages to synergize tumor immunotherapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021;6:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chen W, Wang J, Jia L, Liu J, Tian Y. Attenuation of the programmed cell death 1 pathway increases the M1 polarization of macrophages induced by zymosan. Cell Death Dis 2016;7:e2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Meng X, Liu X, Guo X, Jiang S, Chen T, Hu Z, et al. FBXO38 mediates PD-1 ubiquitination and regulates antitumor immunity of T cells. Nature 2018;564:130–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Martinez FO, Gordon S, Locati M, Mantovani A. Transcriptional profiling of the human monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and polarization: new molecules and patterns of gene expression. J Immunol 2006;177:7303–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kitchen GB, Cunningham PS, Poolman TM, Iqbal M, Maidstone R, Baxter M, et al. The clock gene Bmal1 inhibits macrophage motility, phagocytosis, and impairs defense against pneumonia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020;117:1543–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wang S, Lin Y, Yuan X, Li F, Guo L, Wu B. REV-ERBα integrates colon clock with experimental colitis through regulation of NF-κB/NLRP3 axis. Nat Commun 2018;9:4246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Elinav E, Nowarski R, Thaiss CA, Hu B, Jin C, Flavell RA. Inflammation-induced cancer: cross-talk between tumors, immune cells, and microorganisms. Nat Rev Cancer 2013;13:759–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nakagawa H, Koyanagi S, Kuramoto Y, Yoshizumi A, Matsunaga N, Shimeno H, et al. Modulation of circadian rhythm of DNA synthesis in tumor cells by inhibiting platelet-derived growth factor signaling. J Pharmacol Sci 2008;107:401–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wu Y, Tao B, Zhang T, Fan Y, Mao R. Pan-cancer analysis reveals disrupted circadian clock associates with T-cell exhaustion. Front Immunol 2019;10:2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.