Abstract

Translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) is a highly conserved multifunctional protein localized in the cytoplasm and nucleus of eukaryotic cells. It is secreted through exosomes and its degradation is associated with the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), heat shock protein 27 (Hsp27), and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA). Its structure contains three α-helices and eleven β-strands, and features a helical hairpin as its hallmark. TCTP shows a remarkable similarity to the methionine-R-sulfoxide reductase B (MsrB) and mammalian suppressor of Sec4 (Mss4/Dss4) protein families, which exerts guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) activity on small guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) proteins, suggesting that some functions of TCTP may at least depend on its GEF action. Indeed, TCTP exerts GEF activity on Ras homolog enriched in brain (Rheb) to boost the growth and proliferation of Drosophila cells. TCTP also enhances the expression of cell division control protein 42 homolog (Cdc42) to promote cancer cell invasion and migration. Moreover, TCTP regulates cytoskeleton organization by interacting with actin microfilament (MF) and microtubule (MT) proteins and inducing the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process. In essence, TCTP promotes cancer cell movement. It is usually highly expressed in cancerous tissues and thus reduces patient survival; meanwhile, drugs can target TCTP to reduce this effect. In this review, we summarize the mechanisms of TCTP in promoting cancer invasion and migration, and describe the current inhibitory strategy to target TCTP in cancerous diseases.

Keywords: Translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP), Invasion, Migration, Cancer, Clinical drugs

1. Introduction

The human translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) was identified in 1989 (Gross et al., 1989). It contains three α-helices (α1, α2, and α3) and eleven β-strands arrayed in two small β-sheets, β2-β1-β11 and β5-β6, and a relatively larger β-sheet β7-β8-β9-β10-β4-β3. The small β-sheet β2-β1-β11 and the larger β-sheet are twisted and their arrangement forms a β-tent. The long 30‒33-amino acid loop is one conserved structural feature of TCTP. This loop connects strands β5 and β6, and possibly has diverse dynamic properties in various species (Susini et al., 2008). The helices α2 and α3 are linked by a short loop that establishes a kink to form a helical hairpin, which is a hallmark of TCTP (Lowther et al., 2002). TCTP is an evolutionarily highly conserved and pleiotropic protein with 96% sequence similarity to the translationally controlled and growth-related mouse tumor protein p23 (Gross et al., 1989). TCTP is also called tumor protein translationally-controlled 1 (Tpt1), fortilin, Q23, histamine-releasing factor, or microtubule and mitochondria interacting protein (Mmi1p) (Brioudes et al., 2010). Initially, the TCTP protein showed no analogy with any other proteins. Subsequently, researchers found that it was structurally analogous with methionine-R-sulfoxide reductase B (MsrB), which is an enzyme involved in cell protection against oxidation damages via reducing methionine sulfoxide back to methionine. Then, TCTP protein was found to be analogous with the mammalian suppressor of Sec4 (Mss4/Dss4) protein families (Thaw et al., 2001). Mss4 acts as a relatively low-efficiency guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) and also shows guanine nucleotide-free chaperone (GFC) activity for certain members of Ras superfamily small guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases) (Thaw et al., 2001). Hence, TCTP may have a GEF or GFC-like activity similar to small GTPases. Moreover, TCTP has attracted increasing attention due to its intracellular and extracellular roles in many biological processes. The intracellular functions of TCTP were linked with its Ca2+-binding activity and association with microtubules (MTs) (Haghighat and Ruben, 1992). The Ca2+-binding domain of TCTP, which was mapped using a combination of several deletion constructs of rat TCTP and 45Ca2+-assay, is confined to amino acid residues 81‒112. This binding region seems to consist of random coil regions neighboring a helix (Kim et al., 2000). The extracellular function of TCTP was identified as a histamine-releasing factor present in allergic patients (MacDonald et al., 1995), and was demonstrated for its anti-apoptotic activity in HeLa and U2OS cells (Li et al., 2001). The multifunctional nature of TCTP is realized by a variety of post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation, acetylation, ubiquitination, and sumoylation (Yarm, 2002).

It is not surprising that the aberrant activation of TCTP may trigger a range of pathological processes, with the most significant being cancer. Tumor proteins, such as Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS), B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase (BRAF), neurofibromin 2 (NF2), and v-myc myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog (MYC), are usually highly expressed in cancer and participate in the processes of promoting proliferation, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis (Cho et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2022; Wei et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2022). Although TCTP is not a tumor-specific protein, its high level in cancerous tissues was often associated with a more aggressive form of disease and poor patient prognosis. On the contrary, low levels of TCTP result in a higher survival rate. Typically, this can be attributed to its anti-apoptotic effect and the promotion of cancer cell division and tumorigenesis. These functions of TCTP on cancer have been reported by seven review articles (Bommer and Thiele, 2004; Chan et al., 2012a; Koziol and Gurdon, 2012; Nagano-Ito and Ichikawa, 2012; Amson et al., 2013a, 2013b; Acunzo et al., 2014). In recent years, the functions of TCTP involved in the invasion and migration of cancer have raised growing concern (Xiao et al., 2016; Gao et al., 2020). TCTP exerts GEF activity on small GTPase Ras homolog enriched in brain (Rheb) to boost the growth and proliferation of Drosophila cells (Dong et al., 2009), and it enhances the expression of small GTPase cell division control protein 42 homolog (Cdc42) to promote cancer cell invasion and migration (Xiao et al., 2016). TCTP regulates cytoskeleton organization to promote cell movement by associating with actin microfilament (MF) and MT proteins, which have strong kinetic characteristics between polymerization and depolymerization (Bazile et al., 2009). Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) occurs in the process of tumor invasion and migration, and a number of molecules are engaged in its initiation process. As one of these molecules, TCTP induces EMT and ultimately promotes cancer cell movement (Bae et al., 2015). TCTP is a promising pharmacologic target for cancer treatment. Compelling evidence has shown that the drugs' histamine inhibitors and artemisinin analogues effectively target TCTP and reduce its expression to inhibit tumorigenesis (Fujita et al., 2008; Seo and Efferth, 2016). In this review, we focus on the role of TCTP of promoting cancer cell invasion and migration, and summarize the anticancer effects of drugs achieved by reducing TCTP levels. In this way, we aim to provide a comprehensive and clear scientific background for researchers to develop novel avenues in cancer treatment.

2. Secretion and degradation of TCTP

Many secretory proteins contain a signal sequence that consists of 13‒30 hydrophobic amino acids at their N-termini, and are secreted in an endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi-dependent pathway. Some proteins, however, exit cells independent of the endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi apparatus (Bell and Hunt, 1992; Wandall, 1992). Several potential mechanisms of such unconventional means of protein secretion have been proposed, including plasma membrane resident transporters, lysosomes, membrane blebbing, and exosome secretion (Wandall, 1992). TCTP is secreted in exosomes. Hypoxia and ischemia promote TCTP secretion by the activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α. Under this condition, the secretion of TCTP from LoVo and HCT116 cancer cells is increased in a time-dependent manner with the upregulation of intracellular TCTP (Xiao et al., 2016). Subsequently, TCTP colocalizes and interacts with tumor suppressor-activated pathway 6 (TSAP6), which facilitates TCTP export through exosomes at the plasma membrane of vesicular structures (Amzallag et al., 2004). Another exosome-related mechanism for TCTP secretion is that the overexpression of H+/K+ adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) increases TCTP secretion from HEK293 and U937 cells (Choi et al., 2009).

Although TCTP is a specific target for ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) degradation and it interacts with E3-ligases, it is not a substrate of ubiquitin ligases. Accordingly, TCTP has a relatively long half-life. It was revealed that the half-life of TCTP mediated by the UPS pathway is subsequently shortened when dihydroartemisinin (DHA) binds with TCTP (Fujita et al., 2008). Two additional mechanisms have been reported to expedite the degradation of TCTP: the knockdown of heat shock protein 27 (Hsp27) and the overexpression of chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA). On the one hand, the knockdown of Hsp27leads to decreased protein expression of TCTP without affecting its messenger RNA (mRNA) expression in a prostate carcinoma cell line (Baylot et al., 2012). On the other hand, CMA reduces the level of TCTP after acetylation as a posttranslational modification (Bonhoure et al., 2017).

3. Mechanism of TCTP in promoting cancer cell movement

Cell migration includes not only extending prominences (lamellipodia and filopodia) and forming new adhesions at the cell fronts, but also cell body movement, the adhesion release of cell tails, and contraction of the cell body (Howe, 2004). The cytoskeleton is comprised of many different structural proteins, such as actin and tubulin, which can form polymers, ultimately promoting cell invasion and migration. TCTP interacts with the cytoskeleton, mostly with MFs and MTs, and regulates the cytoskeleton organization to influence cell shape and motility. Small GTPase Cdc42 can participate in the regulation of the cytoskeleton, and TCTP may control cell movement by the regulation of Cdc42 (Xiao et al., 2016). The structure of TCTP possesses strong similarity with the MsrB and with the Mss4/Dss4 protein family, and the function of TCTP partially depends on GEF activity (Cans et al., 2003). In addition, TCTP initiates the EMT process to promote cancer cell movement.

3.1. TCTP exerts GEF activity on Rheb and regulates Cdc42

The guanosine triphosphate-guanosine diphosphate (GTP-GDP) cycle of small GTPase is regulated by two classical regulatory proteins. The activation of small GTPase is performed by GEFs, and its inactivation is regulated by GTPase-activating proteins (Mertens et al., 2003). It was found that TCTP is directly associated with Rheb, a small GTPase as well as an upstream protein of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), and exerts its GEF activity on Rheb to promote the growth and proliferation of S2 cells or Drosophila (Hsu et al., 2007). A mutation from glutamic acid to valine in the GTPase-binding groove of TCTPE12V abolishes its GEF activity (Hsu et al., 2007). Subsequently, a decreased TCTP level does not affect mTORC1 signaling in NIH3T3-A14 cells and S2 cells, and a stable interaction between TCTP and Rheb has not been observed in HEK293T cells (Rehmann et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008). However, TCTP was proved to have the ability to bind Rheb and to accelerate GDP release from Rheb in HEK293T cells (Dong et al., 2009). Moreover, TCTP activated the mTORC1 pathwayin vivo, and the presence of key residues of TCTP–Rheb interaction was experimentally confirmed with site-directed mutagenesis and biochemistryin vitro and cell biological analysesin vivo, which strongly supported that TCTP plays a GEF function on Rheb in HEK293T cells (Dong et al., 2009). This relationship between TCTP and Rheb needs to be further confirmed in cancer cells.

Furthermore, TCTP was shown to be related to other small GTPases. The protein levels of both TCTP and RhoA were dramatically higher in ovarian cancer OVCAR3 cells than in ovarian surface epithelial HIO180 cells (Kloc et al., 2012), while the overexpression of TCTP only activated Cdc42, but not RhoA or Rac1, using GTPase-linked immunosorbent assay (G-LISA) in LoVo cells, and decreased TCTP expression inhibited cancer cell invasion and migration by lowering Cdc42 activation in gallbladder cancer cells (Zhang et al., 2017). The positive correlation between the expression of TCTP and Cdc42 was further confirmed in clinical colorectal cancer patient samples by immunohistochemistry staining assays (Xiao et al., 2016), but it is still unclear whether TCTP regulates Cdc42 through GEF activity.

3.2. TCTP interacts with the cytoskeleton to promote cancer cell invasion and migration

The actin cytoskeleton is a highly dynamic network, and the polymerization of globular actin (G-actin) to filamentous actin (F-actin) generates a variety of architectures to regulate cell movement in tumor tissues (Yu et al., 2020). TCTP is interacted with MF in cell-free extracts and clearly colocalizes with curly F-actin at the cell border (Bazile et al., 2009). Immunofluorescence revealed cytoplasmic fibers stained with TCTP antibody in Xenopus XL2 cells, and TCTP was found to localize to a subset of actin-rich fibers in migrating cells, although it failed to bind to purified F-actin (Bazile et al., 2009). However, another research reported that TCTP participated in the Ca2+-mediated multimerization of F-actin (Arcuri et al., 2004; Ishida et al., 2017). Cofilin binds to both G-actin and F-actin and is believed to promote tumor metastasis by enhancing actin dynamics at the leading cell edge (van Rheenen et al., 2009). TCTP and cofilin are colocalized in the cytoplasm and exhibit a strong signal with low background in 16HBE cells (Huang et al., 2015). The primary sequence of TCTP revealed homology with the actin-binding region of cofilin, and TCTP peptide had a higher affinity for G-actin than for F-actin and promoted cofilin release from G-actin. This suggests that TCTP may channel active cofilin to F-actin, increasing the cofilin activity cycle to promote tumor metastatis (Tsarova et al., 2010).

The rearrangement of MTs promotes the formation of cell polarity and guides migration (Ho et al., 2014). TCTP is partially colocalized with the MT cytoskeleton, but it lacks MT-binding affinity and does not affect the assembly/disassembly of MTs detected in pull-down and cell-free extract assays in Xenopus XL2 cells (Bazile et al., 2009). However, the knockdown of TCTP by RNA interference provokes a significant MT-dependent shape change in XL2 and HeLa cells, which suggests that TCTP interacts with MTs and does not behave as a classic MT-associated protein (Bazile et al., 2009). Depending on the cell type or the species, TCTP is localized either at the spindle pole or γ-tubulin-containing pericentriolar material, as shown by immunofluorescence and tagged TCTP expression in XL2, HeLa, mouse NIH3T3, and monkey Cos7 cells; however, TCTP associates with MTs indirectly (Jaglarz et al., 2012). The overexpression of TCTP facilitates cell migration due to inducing actin cytoskeletal reorganization. TCTP knockdown by specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) significantly inhibits the motility of primary astrocytes owing to the reorganization of MTs and the disturbance of F-actin cytoskeleton network (Ren et al., 2015).

The interactions between TCTP with MTs and F-actin in cell polarization and movement continuously evolve, and the relevant cell shape changes are also linked to the interaction with neighboring cells and/or extracellular matrix. Focal adhesions are composed of plasma membrane-associated dynamic supermolecules, including protein focal adhesion kinase (FAK), vinculin, and paxillin, etc. They link the actin cytoskeleton to integrin and establish a relationship with the extracellular matrix. For example, integrin β1-mediated FAK/protein kinase B (Akt) signaling leads to matrix metallopeptidase-2 (MMP-2) and MMP-9 expression, and subsequently promotes the invasion, migration, and adhesion of gastric cancer cells (Wang et al., 2017). It was identified that TCTP and FAK are co-expressed and simultaneously upregulated in the membranes of oncogenic H-RasV12-transformed p38α-deficient mouse embryo fibroblasts cells (Alfonso et al., 2006). TCTP knockdown reduces the protein levels of FAK and phosphorylated FAK (p-FAK) and leads to suppressing the growth and migration abilities of cholangiocarcinoma KKU-M055 cells (Phanthaphol et al., 2017). The knockdown or inhibition of TCTPalso decreases fibronectin, MMP-9, laminin, vitronectin, and collagen I levels in LoVo cells and mouse melanoma B16F10 cells (Ma et al., 2010; Bae et al., 2015).

3.3. TCTP interacts with EMT-related proteins to promote cancer cell invasion and migration

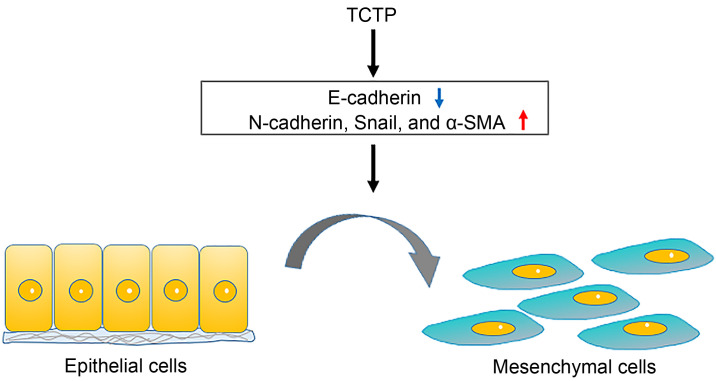

The EMT is an important biological process to allow epithelial cells to undergo multiple biochemical changes and lose their cell–cell interaction as well as to ultimately gain a mesenchymal phenotype. EMT may increase the invasiveness and motility of cancer cells and initiate cancer metastasis (Chaffer and Weinberg, 2011). TCTP is a target of transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), which is a key regulator of EMT. The overexpression of TCTP is connected with mesenchymal characters, while its downregulation promotes the expression of epithelial markers (E-cadherin) and inhibits invasion and migration even under the exposure of TGF-β1 treatment in A549 cells (Mishra et al., 2018). TCTP promotes the expression of EMT-related markers (N-cadherin, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), Snail, Slug, and Twist), enhances cell invasiveness via activating MMP-9, and accelerates migration by activating mTORC2/Akt/glucogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β)/β-catenin signal transduction (Bae et al., 2015). The overexpression of recombinant human TCTP promotes the invasion and migration of LoVo cells by increasing the expression level of phospho-c-Jun N-terminal kinase (p-JNK) from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and enhancing the secretion of MMP-9 (Xiao et al., 2016). Conversely, TCTP knockdown significantly inhibits cancer cell invasion and migration detected by transwell assays and scratch wound healing in lung cancer HCC827 and A549 cell lines (Wang et al., 2018) and gallbladder cancer NOZ and GBC-SD cell lines (Zhang et al., 2017). A suppressed TCTP level reverses the induction of EMT phenotypes and significantly reduces pulmonary metastasis by inhibiting the development of mesenchymal-like phenotypes in melanoma cells (Bae et al., 2015). It also decreases the expression levels of MMP-2, MMP-9, N-cadherin, and α-SAM in glioma U251 cells and mouse melanoma B16F10 cells (Bae et al., 2015; Jin et al., 2015) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. TCTP promotes the EMT process by downregulating epithelial markers and upregulating mesenchymal markers. TCTP: translationally controlled tumor protein; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition; α-SMA: α-smooth muscle actin.

In addition to regulating the EMT-related proteins, TCTP is also associated with other tumor proteins involved in metastasis promotion. Higher mRNA and protein levels of TCTP are related to the exogenous phosphatase of regenerating liver-3 (PRL-3) identified by proteomes. The knockdown of TCTP by siRNA inhibits the PRL-3-promoted proliferation, invasion, and migration of LoVo cells transfected with the PRL-3 gene (Chu et al., 2011). By comparing whole-cell proteomes on two dimentional-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D-SDS-PAGE), it was found that the components of UPS and the proteins involved in cancer proliferation, metastasis, cytoskeleton metabolism, and ion binding are changed upon TCTP downregulation in LoVo cells, in which the expression of 27 proteins was altered, as shown by mass spectrometry analysis. This result was validated again by analyzing the protein expression levels in parental, short hairpin non-coding RNA (shncRNA)-TCTP, and shRNA-TCTP LoVo cell groups by western blotting (Ma et al., 2010). Recently, it was pointed out that TCTP can maintain tumor growth by negatively regulating cell autophagy (Lee et al., 2020).

4. TCTP levels in malignant tumors

A large body of clinical evidence indicates that TCTP is usually expressed at high levels in cancerous tissues and reduces patient survival rates. The mRNA and protein levels of TCTP in invasive (microvascular and neural invasion) and metastatic (liver, lymph node, and abdominal metastases) gallbladder cancer samples were higher than those in non-invasive and non-metastatic ones, and more than 85% of the gallbladder cancer specimens showed a positive association with a high expression of TCTP using immunohistochemistry (IHC) to analyze 73 cancer samples (Zhang et al., 2017). A microarray analysis of 211 clinical specimens showed that 75% of castration-resistant prostate cancer samples exhibited TCTP overexpression, while no or only weak expression of TCTP was detected in benign or normal tissues (Baylot et al., 2017). Huang et al. (2018) used an IHC experiment and western blot to demonstrate that the expression of TCTP in colorectal cancer patients (without metastasis) was significantly higher than that in benign polyp control subjects, and its levels increased further in metastatic tumors. In 508 breast cancer samples, TCTP was overexpressed in the scattered cells of the tumor parenchyma, but not detected in the normal breast parenchyma. A high level of TCTP was associated directly with a poor degree of differentiation, high proliferative activity, and low or negative estrogen receptor expression, each of which is indicative of aggressive G3 tumors (Amson et al., 2012). Moreover, the correlation between the high-TCTP status and a poorer prognosis was maintained after making adjustments for the major clinical and pathological parameters in a multivariate proportional-hazard model, which suggested that TCTP in breast cancer is an independent predictor of poor prognosis (Amson et al., 2012). Sun et al. (2019) conducted an IHC analysis of 24 pairs of tumor tissues and adjacent normal tissues, and found that the level of TCTP in lung cancer tissues was approximately four times greater when compared with adjacent tissues; western blot and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) experiments showed similar results. Using the lung cancer database provided by the website (https://www.kmplot.com) and the online Kaplan-Meier plotter, they also found that cancer patients with a high expression level of TCTP had shorter overall survival time. Our research group investigated the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) database and analyzed other cancers, such as adrenocortical carcinoma, bladder urothelial carcinoma, cervical cancer, and esophageal cancer, to find that a high expression of TCTP reduces the survival rate of patients. In addition, a high expression level of TCTP was significantly correlated with tumor size and was linked to shorter survival time in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) specimens (Chan et al., 2012b; Liu et al., 2020). Highly expressed TCTP was also associated with high pathological grades and metastatic tumor node metastasis stage and significantly correlated with the poor metastasis-free survival rate in colorectal cancer patients (Xiao et al., 2016). TCTP protein levels in high-grade lung adenocarcinoma tissues are significantly higher than those in low-grade tissues (Sun et al., 2019). Moreover, high TCTP scores were highly correlated with overall metastasis and shorter survival time according to the analysis of 119 individual cases of cholangiocarcinoma and ovarian cancer tissues, while the age, sex, or histological type did not have any associations with TCTP protein levels (Chen et al., 2015; Phanthaphol et al., 2017).

Vimentin is a mesenchymal protein that can promote EMT. Among six groups of NSCLC specimens, TCTP and vimentin were upregulated in lung tumors of three patients, and a positive correlation between TCTP and vimentin levels was found in lung tumors of five patients (Liu et al., 2020). Pim-3 is a member of the Pim family of proto-oncogenes. Zhang et al. (2013) performed IHC on 148 cases with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma tissues and found that both TCTP and Pim-3 proteins were expressed positively in most of these tissues. Moreover, TCTP protein was detected in large quantities in malignant ductal epithelial cells, but not in normal pancreatic ductal epithelial cells adjacent to cancer (Zhang et al., 2013). TCTP is the phosphorylated substrate of polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1). In 88 cases of neuroblastoma, the levels of PLK1 and phospho-TCTP were significantly higher, which was related to poor clinical, biological, and pathological characteristics, such as late-stage tumors and a high mitotic index (Ramani et al., 2015). The chromodomain helicase/ATPase DNA-binding protein 1-like (CHD1L) is carcinogenic and can promote the expression of TCTP. Both CHD1L and TCTP were upregulated in human HCC samples analyzed by Chan et al. (2012b). Recently, D'Amico et al. (2020) found that the higher expression of phospho-TCTP in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive breast cancer patients showed poorer clinical response after trastuzumab treatment. In short, TCTP is overexpressed in tumors and regulates some key processes of cancer cells, and thus can be used as an important target for clinical treatment.

5. Drugs targeting TCTP for cancer treatment

In light of the above-described carcinogenic roles of TCTP, it seems worthwhile to find pharmacological compounds to reduce its expression level. Tanshinone IIA, an active drug extracted from Salvia milti orrhiza, has an anticancer effect, and it downregulates the level of TCTP in gastric cancer (Su, 2014) and pancreatic cancer (Huang et al., 2013) cells to inhibit cell proliferation. Oxaliplatin, a third-generation platinum compound, has been widely used in cancer chemotherapy; it increases TCTP expression first and then decreases it in colon cancer HT29, SW620, and LoVo cells. Furthermore, it induces S phase accumulation and G2/M phase arrest, promotes cell apoptosis, and inhibits proliferation (Yao et al., 2009). As a traditional medicinal prescription, Sann-Joong-Kuey-Jian-Tang also reduces the TCTP level, inhibits cell proliferation, and promotes cell apoptosis in HepG2 cells (Chen et al., 2013). Another chemical, curcumin downregulates TCTP to induce mitochondrial dysfunction in HCC J5 cells and promote cell apoptosis (Cheng et al., 2010).

Differentiation therapy is a promising strategy for cancer treatment, and TCTP plays a key role in tumor phenotype reversal, which allows the tumor cells to differentiate into normal tissues. Tuynder et al. (2002) found 263 genes to be either activated or inhibited during the reversion process, as confirmed by quantitative PCR or northern blot analysis. Of these, TCTP had the strongest differential expression. U937 leukemic cells stably transfected with antisense TCTP form less and smaller tumors than controls when injected into severe combined immune deficiency (SCID) mice (Tuynder et al., 2002). Moreover, fibroblasts transformed with v-Src become elongated and have an increased growth rate. When transfected with antisense TCTP, v-Src-transformed NIH3T3 cells acquire a flat shape and their growth rate becomes comparable to untransfected fibroblasts. These results suggest that TCTP can be used as a target for differentiation therapy (Tuynder et al., 2004). By using a chemical library of more than 31 000 compounds for electronic screening and molecular docking, ZINC10157406 and AMG900, as new ligands of TCTP, were identified by Fischer et al. (2021) for cancer differentiation therapy. Microscale thermophoresis and co-immunoprecipitation showed that ZINC10157406 and AMG900 could bind to the p53-binding site of TCTP with strong affinity, which could significantly downregulate the expression of TCTP, increase free p53 expression, and induce the G0/G1 arrest of MCF-7, SK-24 OV3, and MOLT-4 cell lines to inhibit cell growth (Fischer et al., 2021). In addition, F6, an active fraction from embryo fish, decreases the level of TCTP in MDA-MB-231 cells and increases the activation of p53, which curbs the proliferation, invasion, and migration of cancer cells, promotes apoptosis, and reverses the malignant phenotype of tumors (Proietti et al., 2019). Differentiation therapy, as a promising emerging therapeutic approach, is expected to be less toxic and more selective than cytotoxic chemotherapy. Currently, however, this field of research is still at its infancy, which motivates researchers to identify more novel TCTP inhibitors and to study their anticancer mechanisms, so that they can be used safely and effectively in clinical application.

TCTP is also called histamine-releasing factor. After treatment with the antihistamine drugs levomepromazine and buclizine, TCTP expression becomes significantly reduced, and the cell cycle of MCF-7 cells will be blocked in the G1 phase in a dose-dependent manner without triggering their apoptosis (Seo and Efferth, 2016). Levomepromazine and buclizine bind to TCTP to inhibit the proliferation of MCF-7 cells due to the induction of cell differentiation rather than its toxic effect, which was confirmed by testing the formation of lipid droplets as a differentiation marker (Seo and Efferth, 2016). The analogues of antihistaminic drugs, sertraline and thioridazine, have been confirmed to bind with TCTP by surface plasmon resonance, which leads to reverse TCTP-induced tumor suppression protein p53 ubiquitination (Amson et al., 2013a). A study has shown that TCTP directly interacts with the lysine (Lys)101-proline (Pro)300 region including the DNA-binding motif of p53 to prevent the transcriptional activation of the proapoptotic protein B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2)-associated X protein (Bax) (Rho et al., 2011). Moreover, sertraline and thioridazine bind TCTP to restore mouse double minute 2 (MDM2) auto-ubiquitination, as well as to prevent the TSAP6-TCTP complex formation and to disrupt the binding of TCTP to MDM2. Further experiments proved that two site mutants (S46E and S64E) of TCTP lose its ability to bind sertraline and thioridazine, suggesting that the residues S46 and S64 are related to the interaction of TCTP with these drugs (Amson et al., 2013a). Sertraline reduces the growth and migration of prostate cancer stem cells and induces death by targeting TCTP (Chinnapaka et al., 2020). In vivo, sertraline and thioridazine suppress the expression of TCTP protein to decrease the tumor growth in breast cancers and monocytic leukemia induced in mice (Tuynder et al., 2004). Meanwhile, research has shown that sertraline and thioridazine commonly lead to life-threatening cardiovascular toxicity by inhibiting cardiovascular Na+, K+, and Ca2+ channels (e.g., arrhythmia) (Pacher and Kecskemeti, 2004). Therefore, before they can be used as anticancer drugs, it is necessary to conduct adequate clinical studies. Sertraline has entered clinical studies for cancer treatment, including an ongoing phase I/II clinical trial involving end-stage acute myeloid leukemia patients (Amson et al., 2017).

DHA, as a derivative of artemisinin, is able to specifically bind to TCTP. Although the cytotoxicity of DHA has been reported to decrease cell viability after 6 h of incubation in murine GT1-7 hypothalamic neurons, its excellent anticancer performance must be acknowledged (Raghavamenon et al., 2011). DHA reduces TCTP expression levels by increasing its ubiquitination and shorting its half-life in a proteasome-dependent fashion in the vascular smooth muscle cells, the lung cancer A549 and H1299 cell lines, the osteosarcoma U2OS cell line, and the breast cancer MDA468 and MCF7 cell lines (Fujita et al., 2008). DHA also targets phospho-TCTP and notably reduces its expression in breast cancer cell lines (Lucibello et al., 2015). Trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) is an anti-HER2 antibody-drug. DHA can increase the drug sensitivity of T-DM1 to HER2-positive breast cancer and disrupt the mitosis process by reducing the level of phospho-TCTP. The combination of DHA with T-DM1 enhances the MT toxicity of breast cancer cells HCC1954 and HCC1569, which contributes to the therapeutic effect (D'Amico et al., 2020). The metastasis model is built by injecting TCTP-positive NOZ and TCTP-negative EH-GB-2 gallbladder cancer cells into mice spleen. Treatment with DHA reduces spleen-to-liver metastasis by about 50% than vehicle controls, which suggests that DHA inhibits TCTP-dependent cell invasion and migration in gallbladder cancer (Zhang et al., 2017). In a previous study by our group, a combination of DHA and resveratrol, a natural product and a polyphenolic phytoalexin with anticancer potential, upregulated the tumor suppressor gene deleted in liver cancer 1 (DLC1) and significantly downregulated TCTP expression compared to each compound alone in HepG2 and MDA-MB-231 cancer cells (Gao et al., 2020). Furthermore, this combination treatment impeded the cancer cell migration via modulating the DLC1/TCTP axis to hinder the Cdc42 regulating JNK/nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (N-WASP) signaling pathways. The combination therapy also effectively inhibited the growth of xenograft tumors in an avian embryo model seeded by HepG2 cells (Gao et al., 2020). Although these drugs are a boon to cancer patients and some of them have exhibited no issues in clinical application, the safety of these drugs for human disease treatment raises concerns, especially when long-term usage is considered.

6. Outlook and conclusions

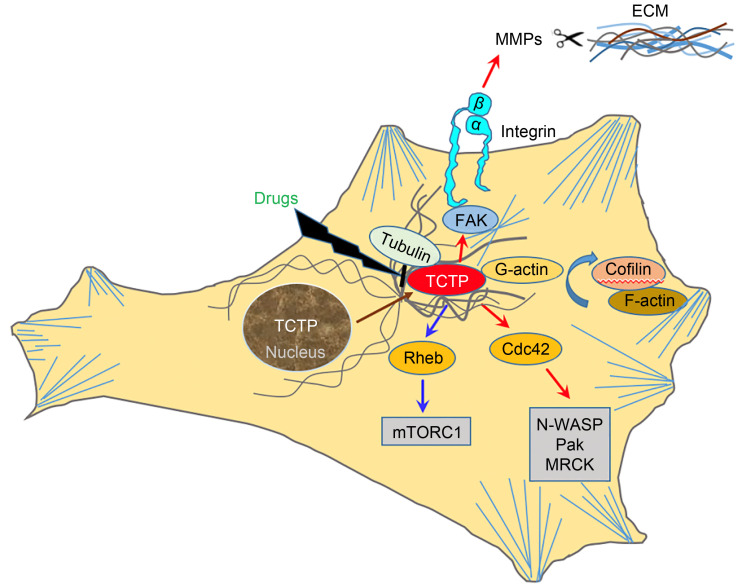

Although TCTP is not a tumor-specific protein, the preferential expression of TCTP underlines the importance of TCTP in the progression of different cancers. As summarized in this paper, TCTP shows remarkable similarity to the MsrB and Mss4/Dss4 protein families and consequently exerts GEF action on the small GTPases Rheb as well as Cdc42. It regulates the cytoskeleton by means of acting on F-actin and MTs-associated proteins to promote cancer cell invasion and migration. Furthermore, TCTP is involved in the cell EMT process and interacts with EMT-related proteins. A high level of TCTP is often associated with aggressive diseases and poor patient prognosis in cancers. Therefore, it is straightforward that the role of TCTP in several malignant tumors and its interactions within cancer cells make it a direct therapeutic target. Certain drugs, such as histamine inhibitors and artemisinin derivatives, inhibit the level of TCTP (Fig. 2). In addition to the existing drugs for blocking TCTP activity, efforts should be made to develop new inhibitors or treatment strategies for targeting TCTP, such as developing peptide-based TCTP inhibitors to interfere with the protein–protein interaction network of TCTP, or exploring the effects of post-translational modifications of TCTP on cancers. Furthermore, it may be a good idea to seek the structural similarity of the TCTP with other proteins to reveal its potential unknown functions and then perform corresponding suppression. Amson et al. (2013b) and Lupas et al. (2015) identified several new TCTP structural homologues (Cereblon, retinoic acid-inducible gene-I (RIG-I), and domain of unknown function (DUF427)). However, whether TCTP has a homologous function like these proteins still needs further exploration. Overall, the mechanisms of TCTP in cancer cell invasion and migration are worth exploring and the existing problems need to be further addressed.

Fig. 2. Underlying oncogenic mechanisms of TCTP during cancer cell invasion and migration. TCTP associates with MTs and MFs and interacts with these proteins, leading to cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis, and this function of TCTP can be inhibited by drugs. Cdc42: cell division control protein 42 homolog; ECM: extracellular matrix; FAK: focal adhesion kinase; F-actin: filamentous actin; G-actin: globular actin; MF: microfilament; MMPs: matrix metallopeptidases; MRCK: myotonic dystrophy kinase-related Cdc42-binding kinase; MT: microtubule; mTORC1: mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1; N-WASP: neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein; Pak: p21-activated kinase; Rheb: Ras homolog enriched in brain; TCTP: translationally controlled tumor protein.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31672377).

Author contributions

Guorong LI and Guiwen YANG outlined the content of the review and made the final corrections for the manuscript. Junying GAO and Yan MA collected the literature and wrote the manuscript. Junying GAO drew the figures. All authors have read and agreed the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

Junying GAO, Yan MA, Guiwen YANG, and Guorong LI declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

- Acunzo J, Baylot V, So A, et al. , 2014. TCTP as therapeutic target in cancers. Cancer Treat Rev, 40(6): 760-769. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso P, Dolado I, Swat A, et al. , 2006. Proteomic analysis of p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase regulated changes in membrane fractions of RAS-transformed fibroblasts. Proteomics, 6(S1): S262-S271. 10.1002/pmic.200500350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amson R, Pece S, Lespagnol A, et al. , 2012. Reciprocal repression between P53 and TCTP. Nat Med, 18(1): 91-99. 10.1038/nm.2546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amson R, Karp JE, Telerman A, 2013a. Lessons from tumor reversion for cancer treatment. Curr Opin Oncol, 25(1): 59-65. 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32835b7d21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amson R, Pece S, Marine JC, et al. , 2013b. TPT1/TCTP-regulated pathways in phenotypic reprogramming. Trends Cell Biol, 23(1): 37-46. 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amson R, Auclair C, André F, et al. , 2017. Targeting TCTP with sertraline and thioridazine in cancer treatment. In: Telerman A, Amson R (Eds.), TCTP/tpt1-Remodeling Signaling from Stem Cell to Disease. Springer, Cham, p.283-290. 10.1007/978-3-319-67591-6_15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amzallag N, Passer BJ, Allanic D, et al. , 2004. TSAP6 facilitates the secretion of translationally controlled tumor protein/histamine-releasing factor via a nonclassical pathway. J Biol Chem, 279(44): 46104-46112. 10.1074/jbc.M404850200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcuri F, Papa S, Carducci A, et al. , 2004. Translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) in the human prostate and prostate cancer cells: expression, distribution, and calcium binding activity. Prostate, 60(2): 130-140. 10.1002/pros.20054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae SY, Kim HJ, Lee KJ, et al. , 2015. Translationally controlled tumor protein induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition and promotes cell migration, invasion and metastasis. Sci Rep, 5: 8061. 10.1038/srep08061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylot V, Katsogiannou M, Andrieu C, et al. , 2012. Targeting TCTP as a new therapeutic strategy in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Mol Ther, 20(12): 2244-2256. 10.1038/mt.2012.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylot V, Karaki S, Rocchi P, 2017. TCTP has a crucial role in the different stages of prostate cancer malignant progression. In: Telerman A, Amson R (Eds.), TCTP/tpt1-Remodeling Signaling from Stem Cell to Disease. Springer, Cham, p.255-261. 10.1007/978-3-319-67591-6_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazile F, Pascal A, Arnal I, et al. , 2009. Complex relationship between TCTP, microtubules and actin microfilaments regulates cell shape in normal and cancer cells. Carcinogenesis, 30(4): 555-565. 10.1093/carcin/bgp022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell NJ, Hunt RH, 1992. Role of gastric acid suppression in the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut, 33(1): 118-124. 10.1136/gut.33.1.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommer UA, Thiele BJ, 2004. The translationally controlled tumour protein (TCTP). Int J Biochem Cell Biol, 36(3): 379-385. 10.1016/s1357-2725(03)00213-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonhoure A, Vallentin A, Martin M, et al. , 2017. Acetylation of translationally controlled tumor protein promotes its degradation through chaperone-mediated autophagy. Eur J Cell Biol, 96(2): 83-98. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2016.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brioudes F, Thierry AM, Chambrier P, et al. , 2010. Translationally controlled tumor protein is a conserved mitotic growth integrator in animals and plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 107(37): 16384-16389. 10.1073/pnas.1007926107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cans C, Passer BJ, Shalak V, et al. , 2003. Translationally controlled tumor protein acts as a guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor on the translation elongation factor eEF1A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 100(24): 13892-13897. 10.1073/pnas.2335950100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA, 2011. A perspective on cancer cell metastasis. Science, 331(6024): 1559-1564. 10.1126/science.1203543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan THM, Chen LL, Guan XY, 2012a. Role of translationally controlled tumor protein in cancer progression. Biochem Res Int, 2012: 369384. 10.1155/2012/369384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan THM, Chen LL, Liu M, et al. , 2012b. Translationally controlled tumor protein induces mitotic defects and chromosome missegregation in hepatocellular carcinoma development. Hepatology, 55(2): 491-505. 10.1002/hep.24709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Deng Y, Hua MH, et al. , 2015. Expression and clinical role of TCTP in epithelial ovarian cancer. J Mol Histol, 46(2): 145-156. 10.1007/s10735-014-9607-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YL, Yan MY, Chien SY, et al. , 2013. Sann-Joong-Kuey-Jian-Tang inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma Hep-G2 cell proliferation by increasing TNF-α, Caspase-8, Caspase-3 and Bax but by decreasing TCTP and Mcl-1 expression in vitro. Mol Med Rep, 7(5): 1487-1493. 10.3892/mmr.2013.1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CY, Lin YH, Su CC, 2010. Curcumin inhibits the proliferation of human hepatocellular carcinoma J5 cells by inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Int J Mol Med, 26(5): 673-678. 10.3892/ijmm_00000513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnapaka S, BAkthavachalam V, Munirathinam G, 2020. Repurposing antidepressant sertraline as a pharmacological drug to target prostate cancer stem cells: dual activation of apoptosis and autophagy signaling by deregulating redox balance. Am J Cancer Res, 10(7): 2043-2065. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho JH, Park S, Kim S, et al. , 2022. RKIP induction promotes tumor differentiation via SOX2 degradation in NF2-deficient conditions. Mol Cancer Res, 20(3): 412-424. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-21-0373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Min HJ, Kim M, et al. , 2009. Proton pump inhibitors exert anti-allergic effects by reducing TCTP secretion. PLoS ONE, 4(6): e5732. 10.1371/journal.pone.0005732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu ZH, Liu L, Zheng CX, et al. , 2011. Proteomic analysis identifies translationally controlled tumor protein as a mediator of phosphatase of regenerating liver-3-promoted proliferation, migration and invasion in human colon cancer cells. Chin Med J, 124(22): 3778-3785. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.2011.22.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico S, Krasnowska EK, Manni I, et al. , 2020. DHA affects microtubule dynamics through reduction of phospho-TCTP levels and enhances the antiproliferative effect of T-DM1 in trastuzumab-resistant HER2-positive breast cancer cell lines. Cells, 9(5): 1260. 10.3390/cells9051260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong XC, Yang B, Li YJ, et al. , 2009. Molecular basis of the acceleration of the GDP-GTP exchange of human Ras homolog enriched in brain by human translationally controlled tumor protein. J Biol Chem, 284(35): 23754-23764. 10.1074/jbc.M109.012823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer N, Seo EJ, Klinger A, et al. , 2021. AMG900 as novel inhibitor of the translationally controlled tumor protein. Chem Biol Interact, 334: 109349. 10.1016/j.cbi.2020.109349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita T, Felix K, Pinkaew D, et al. , 2008. Human fortilin is a molecular target of dihydroartemisinin. FEBS Lett, 582(7): 1055-1060. 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.02.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao JY, Ma FJ, Wang XJ, et al. , 2020. Combination of dihydroartemisinin and resveratrol effectively inhibits cancer cell migration via regulation of the DLC1/TCTP/Cdc42 pathway. Food Funct, 11(11): 9573-9584. 10.1039/d0fo00996b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross B, Gaestel M, Böhm H, et al. , 1989. cDNA sequence coding for a translationally controlled human tumor protein. Nucleic Acids Res, 17(20): 8367. 10.1093/nar/17.20.8367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghighat NG, Ruben L, 1992. Purification of novel calcium binding proteins from Trypanosoma brucei: properties of 22-, 24- and 38-kilodalton proteins. Mol Biochem Parasitol, 51(1): 99-110. 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90205-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho KW, Lambert WS, Calkins DJ, 2014. Activation of the TRPV1 cation channel contributes to stress-induced astrocyte migration. GLIA, 62(9): 1435-1451. 10.1002/glia.22691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe AK, 2004. Regulation of actin-based cell migration by cAMP/PKA. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)-Mol Cell Res, 1692(2-3): 159-174. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu YC, Chern JJ, Cai Y, et al. , 2007. Drosophila TCTP is essential for growth and proliferation through regulation of dRheb GTPase. Nature, 445(7129): 785-788. 10.1038/nature05528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CY, Chiu TL, Kuo SJ, et al. , 2013. Tanshinone IIA inhibits the growth of pancreatic cancer BxPC-3 cells by decreasing protein expression of TCTP, MCL-1 and Bcl-xL. Mol Med Rep, 7(3): 1045-1049. 10.3892/mmr.2013.1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HY, Li X, Hu GH, et al. , 2015. Poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase silencing down-regulates TCTP and Cofilin-1 associated with metastasis in benzo(a)pyrene carcinogenesis. Am J Cancer Res, 5(1): 155-167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M, Geng Y, Deng Q, et al. , 2018. Translationally controlled tumor protein affects colorectal cancer metastasis through the high mobility group box 1-dependent pathway. Int J Oncol, 53(4): 1481-1492. 10.3892/ijo.2018.4502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida H, Jensen KV, Woodman AG, et al. , 2017. The calcium-dependent switch helix of l-plastin regulates actin bundling. Sci Rep, 7: 40662. 10.1038/srep40662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaglarz MK, Bazile F, Laskowska K, et al. , 2012. Association of TCTP with centrosome and microtubules. Biochem Res Int, 2012: 541906. 10.1155/2012/541906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Zhang XX, Su J, et al. , 2015. RNA interference-mediated knockdown of translationally controlled tumor protein induces apoptosis, and inhibits growth and invasion in glioma cells. Mol Med Rep, 12(5): 6617-6625. 10.3892/mmr.2015.4280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Jung Y, Lee K, et al. , 2000. Identification of the calcium binding sites in translationally controlled tumor protein. Arch Pharm Res, 23(6): 633-636. 10.1007/BF02975253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloc M, Tejpal N, Sidhu J, et al. , 2012. Inverse relationship between TCTP/RhoA and p53/cyclin A/actin expression in ovarian cancer cells. Folia Histochem Cytobiol, 50(3): 358-367. 10.5603/19745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koziol MJ, Gurdon JB, 2012. TCTP in development and cancer. Biochem Res Int, 2012: 105203. 10.1155/2012/105203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Jang EH, Woo HA, et al. , 2020. Regulation of autophagy is a novel tumorigenesis-related activity of multifunctional translationally controlled tumor protein. Cells, 9(1): 257. 10.3390/cells9010257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Zhang D, Fujise K, 2001. Characterization of fortilin, a novel antiapoptotic protein. J Biol Chem, 276(50): 47542-47549. 10.1074/jbc.M108954200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu LZ, Wang MH, Xin QH, et al. , 2020. The permissive role of TCTP in PM2.5/NNK-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in lung cells. J Transl Med, 18: 66. 10.1186/s12967-020-02256-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu TY, Zhou LL, Xiao Y, et al. , 2022. BRAF inhibitors reprogram cancer-associated fibroblasts to drive matrix remodeling and therapeutic escape in melanoma. Cancer Res, 82(3): 419-432. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-0614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowther WT, Weissbach H, Etienne F, et al. , 2002. The mirrored methionine sulfoxide reductases of Neisseria gonorrhoeae pilB. Nat Struct Biol, 9(5): 348-352. 10.1038/nsb783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucibello M, Adanti S, Antelmi E, et al. , 2015. Phospho-TCTP as a therapeutic target of Dihydroartemisinin for aggressive breast cancer cells. Oncotarget, 6(7): 5275-5291. 10.18632/oncotarget.2971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas AN, Zhu HB, Korycinski M, 2015. The thalidomide-binding domain of cereblon defines the CULT domain family and is a new member of the β-tent fold. PLoS Comput Biol, 11(1): e1004023. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q, Geng Y, Xu WW, et al. , 2010. The role of translationally controlled tumor protein in tumor growth and metastasis of colon adenocarcinoma cells. J Proteome Res, 9(1): 40-49. 10.1021/pr9001367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald SM, Rafnar T, Langdon J, et al. , 1995. Molecular identification of an IgE-dependent histamine-releasing factor. Science, 269(5224): 688-690. 10.1126/science.7542803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens AE, Roovers RC, Collard JG, 2003. Regulation of Tiam1-Rac signalling. FEBS Lett, 546(1): 11-16. 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00435-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra DK, Srivastava P, Sharma A, et al. , 2018. Translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) is required for TGF-β1 induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition and influences cytoskeletal reorganization. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)-Mol Cell Res, 1865(1): 67-75. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2017.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagano-Ito M, Ichikawa S, 2012. Biological effects of mammalian translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) on cell death, proliferation, and tumorigenesis. Biochem Res Int, 2012: 204960. 10.1155/2012/204960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacher P, Kecskemeti V, 2004. Cardiovascular side effects of new antidepressants and antipsychotics: new drugs, old concerns? Curr Pharm Des, 10(20): 2463-2475. 10.2174/1381612043383872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phanthaphol N, Techasen A, Loilome W, et al. , 2017. Upregulation of TCTP is associated with cholangiocarcinoma progression and metastasis. Oncol Lett, 14(5): 5973-5979. 10.3892/ol.2017.6985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proietti S, Cucina A, Pensotti A, et al. , 2019. Active fraction from embryo fish extracts induces reversion of the malignant invasive phenotype in breast cancer through down-regulation of TCTP and modulation of E-cadherin/β-catenin pathway. Int J Mol Sci, 20(9): 2151. 10.3390/ijms20092151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavamenon AC, Muyiwa AF, Davis LK, et al. , 2011. Dihydroartemisinin induces caspase-8-dependent apoptosis in murine GT1-7 hypothalamic neurons. Toxicol Mech Methods, 21(5): 367-373. 10.3109/15376516.2011.552534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramani P, Nash R, Sowa-Avugrah E, et al. , 2015. High levels of polo-like kinase 1 and phosphorylated translationally controlled tumor protein indicate poor prognosis in neuroblastomas. J Neurooncol, 125(1): 103-111. 10.1007/s11060-015-1900-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehmann H, Brüning M, Berghaus C, et al. , 2008. Biochemical characterisation of TCTP questions its function as a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rheb. FEBS Lett, 582(20): 3005-3010. 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.07.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren JB, Mao XX, Chen MH, et al. , 2015. TCTP expression after rat spinal cord injury: implications for astrocyte proliferation and migration. J Mol Neurosci, 57(3): 366-375. 10.1007/s12031-015-0628-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rho SB, Lee JH, Park MS, et al. , 2011. Anti-apoptotic protein TCTP controls the stability of the tumor suppressor p53. FEBS Lett, 585(1): 29-35. 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo EJ, Efferth T, 2016. Interaction of antihistaminic drugs with human translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) as novel approach for differentiation therapy. Oncotarget, 7(13): 16818-16839. 10.18632/oncotarget.7605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su CC, 2014. Tanshinone IIA inhibits human gastric carcinoma AGS cell growth by decreasing BiP, TCTP, Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL and increasing Bax and CHOP protein expression. Int J Mol Med, 34(6): 1661-1668. 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun RL, Lu X, Gong L, et al. , 2019. TCTP promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition in lung adenocarcinoma. OncoTargets Ther, 12: 1641-1653. 10.2147/OTT.S184555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susini L, Besse S, Duflaut D, et al. , 2008. TCTP protects from apoptotic cell death by antagonizing Bax function. Cell Death Differ, 15(8): 1211-1220. 10.1038/cdd.2008.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaw P, Baxter NJ, Hounslow AM, et al. , 2001. Structure of TCTP reveals unexpected relationship with guanine nucleotide-free chaperones. Nat Struct Biol, 8(8): 701-704. 10.1038/90415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsarova K, Yarmola EG, Bubb MR, 2010. Identification of a cofilin-like actin-binding site on translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP). FEBS Lett, 584(23): 4756-4760. 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.10.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuynder M, Susini L, Prieur S, et al. , 2002. Biological models and genes of tumor reversion: cellular reprogramming through tpt1/TCTP and SIAH-1 . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 99(23): 14976-14981. 10.1073/pnas.222470799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuynder M, Fiucci G, Prieur S, et al. , 2004. Translationally controlled tumor protein is a target of tumor reversion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 101(43): 15364-15369. 10.1073/pnas.0406776101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rheenen J, Condeelis J, Glogauer M, 2009. A common cofilin activity cycle in invasive tumor cells and inflammatory cells. J Cell Sci, 122(3): 305-311. 10.1242/jcs.031146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandall JH, 1992. Effects of omeprazole on neutrophil chemotaxis, super oxide production, degranulation, and translocation of cytochrome b-245. Gut, 33(5): 617-621. 10.1136/gut.33.5.617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LL, Tang YF, Zhao MJ, et al. , 2018. Knockdown of translationally controlled tumor protein inhibits growth, migration and invasion of lung cancer cells. Life Sci, 193: 292-299. 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.09.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XM, Fonseca BD, Tang H, et al. , 2008. Re-evaluating the roles of proposed modulators of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling. J Biol Chem, 283(45): 30482-30492. 10.1074/jbc.M803348200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZX, Wang Z, Li GH, et al. , 2017. CXCL1 from tumor-associated lymphatic endothelial cells drives gastric cancer cell into lymphatic system via activating integrin β1/FAK/AKT signaling. Cancer Lett, 385: 28-38. 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.10.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Redel C, Ahlner A, et al. , 2022. The MYC oncoprotein directly interacts with its chromatin cofactor PNUTS to recruit PP1 phosphatase. Nucleic Acids Res, 50(6): 3505-3522. 10.1093/nar/gkac138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao B, Chen DX, Luo SH, et al. , 2016. Extracellular translationally controlled tumor protein promotes colorectal cancer invasion and metastasis through Cdc42/JNK/MMP9 signaling. Oncotarget, 7(31): 50057-50073. 10.18632/oncotarget.10315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Jia XY, Tian HY, et al. , 2009. Comparative proteomic analysis of colon cancer cells in response to oxaliplatin treatment. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom, 1794(10): 1433-1440. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarm FR, 2002. Plk phosphorylation regulates the microtubule-stabilizing protein TCTP. Mol Cell Biol, 22(17): 6209-6221. 10.1128/MCB.22.17.6209-6221.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu QL, Zhang B, Zhang YM, et al. , 2020. Actin cytoskeleton-disrupting and magnetic field-responsive multivalent supramolecular assemblies for efficient cancer therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, 12(12): 13709-13717. 10.1021/acsami.0c01762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Liu B, Wang Z, et al. , 2013. A novel regulatory mechanism of Pim-3 kinase stability and its involvement in pancreatic cancer progression. Mol Cancer Res, 11(12): 1508-1520. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Ma Q, Xu ZH, et al. , 2017. Dihydroartemisinin inhibits TCTP-dependent metastasis in gallbladder cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 36: 68. 10.1186/s13046-017-0531-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C, Fan ZS, Zhou ZH, et al. , 2022. Discovery of the first-in-class agonist-based SOS1 PROTACs effective in human cancer cells harboring various KRAS mutations. J Med Chem, 65(5): 3923-3942. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]