Abstract

Since the arrival of COVID-19, tourism scholarship has focused its attention on rethinking and restarting the tourism sector. In this urgent search for a ‘new normal’, the embodied experience of hosting such an unwelcomed virus, the philosophical questions this raises, and the tourism futures already in the making, have not been fully explored. The article introduces Nancy's (2000/2002) philosophy, L'intrus [The Intruder], where he reflects on having a heart transplant operation to give body to the experiences of the self as exteriority and of otherness always already within. We take inspiration from Nancy to think and sense the experience of the COVID-19 virus intrusion in tourism. To do this, we weave personal philosophical reflections with ethnographic material to reflect on three themes of intrusion for tourism scholarship to consider: the experience of a body/self as exposed, the experience of a shattered self, and the experience of uncertain futures.

Keywords: COVID-19, Philosophizing tourism, Jean-Luc Nancy, Intrusion, Embodiment, Self, Pandemic, Tourism experience

To Jean-Luc Nancy, in memoriam

1. Introduction

Some strangers are expected, and some take us by surprise. We were experts of the expected ones. We were proud of how tourism had taught us to tame the fear of welcoming the stranger. The stranger now transformed into a familiar identity that would fit our ideas of having control about the future and life – the tourist/consumer/guest. We had become masters in the art of capitalizing, structuring and promoting the tourism experience.

In early December 2019, an unexpected stranger arrived in the form of a virus. Rapidly spreading around the globe, the virus proved to be more networked and expansive than our wildest dreams of smart, fluid, aero-mobilities. Only this time the stranger in tourism did not serve the gaze, the awakening of the senses, but disruption and death. COVID-19 insists on not being welcomed or tamed. The virus touched everyone and its strangeness remains. This stranger, this unwelcomed guest, has made us foreign even to ourselves. What we were, who we are, and what we are becoming, now thrown into an experience of uncertainty and not knowing (Grimwood, 2021). How are we to think tourism through, or with, such an intrusive experience?

This article is an invitation to experience the global pandemic and tourism through Nancy's philosophy of intrusion. While the pandemic experience might appear to be without reason, a passing moment of madness, we argue alongside Nancy (2020a, 1:19:31) it still reveals something about the state of mankind and offers new insights for tourism scholarship on the relational ontology that is at the core of our being and becoming. In the same way, the pandemic teaches us something about tourism, exposing different questions and understandings of the tourism experience, the tourist as self and body, and finally of the desire and impossibility of returning to a ‘new normal’. This paper invites other authors to explore being philosophical as a method to think and write tourism.

1.1. Nancy's philosophy of intrusion and relational ontology

COVID-19 resembles Jean-Luc Nancy, 2000, Nancy, 2002 philosophy of L'Intrus [The Intruder] in that like the virus, “The intruder enters by force, through surprise or ruse, in any case without the right and without having first been admitted.” At age 50, Nancy received the news that his heart was worn out and that he needed “another's, an other, heart” (Nancy, 2000, Nancy, 2002). Nancy's intruder is a transplanted heart, which produces all kinds of unwelcomed strangeness. On the one hand, there is an embodied experience of strangeness in the form of an implanted foreign heart. His own heartbeat, the pulsing of blood through veins, life itself, now irreconcilably strange and dependent on a living foreign entity embedded within him. This is an endlessly risky endeavor, as at any given time his body could reject this foreign intruder. To prevent this, his body becomes connected to all types of machinery and surveillance, revealing a “stream of unremitting strangeness” as his self/body are refigured and reworked alongside new technologies, systems, networks, and relations (Nancy, 2000, Nancy, 2002, p.10). Nancy describes feeling a quasi-necessity of opting into these techno-interventions: his survival now dependent on strangers and strangeness. This necessity “to live…”, and playing with his French accent jests, “…not to leave”, is met with equal amounts of gratitude towards life and unease with the machinery that keeps him alive (Nancy, 2020a, 42:45).

On the other hand, this radical intrusion—the cutting open of one's chest, the removal of one's heart, the suturing back together of an intruded upon body—draws attention not only to foreign organs and new techno-assemblages, but also signals an embodied exteriority and strangeness which was always already inside. There is the unwelcomed realization that his own untimely heart has betrayed him: the intruder already within, an impure heart from the start. “If my heart was giving up and going to drop me, to what degree was it an organ of ‘mine’, my ‘own’?” he asks (2000/2002, p. 3). Then, there is the discovery of viruses being already a part of all of us (Nancy, 2020a, 1:07:37). Nancy, 2000, Nancy, 2002 explains how his own flesh and blood have always been contaminated by a host of multiple, micro lifeforms that put him at risk. Like pandemic prevention measures, he is warned of the dangers posed to his weakened immunity system by the outside world—“the crowds, stores, swimming pools, small children, those who are sick”—but it is not only the outside world that makes him vulnerable. With intrusion, once dormant diseases (cancers, shingles, cytomegalovirus) surface:

…foreign/strangers that have always laid dormant within me, now suddenly roused and set against me by the necessary depression of my immune system…the most vigorous enemies are inside: the old viruses that have always been lurking in the shadow of my immune system—life-long intrus [intruder], as they have always been there. (p.9).

Nancy's figure of the intruder therefore invites an experience of a two-fold ontological strangeness. First, intrusion serves as a reminder that all origins/essences/foundations remain open, vulnerable and exposed in relation to a constitutive outside. Intrusion exposes the impossibility of an autonomous self/body independent from external ‘other(s)’ or ‘otherness’, emphasizing that the human becomes with others; “the other who is me” (2020a, 35:07). Then by doubling back on the intruded upon body, Nancy further questions the assumption of the body's integrated totality by drawing attention to the otherness from within, which never ceases being strange (Geroulanos & Meyers, 2009). Intrusion is an embodied reminder that no existence, no body, no thing, stems simply from itself, for itself. From our own hearts to the soles of our feet walking (2000/2002, p. 3), the otherness that we are appears absent and strange to our consciousness of ‘self’ and body.

Like Nancy, both psychoanalysis and post-structuralism have long expressed the idea of the multiplicity of the subject and the self: each one of us, our “I”, is always already othered through language, culture, time and space. What makes Nancy's reflection on intrusion unique is that he “give[s] body to the intrusion of the ‘other-than-self’ which is always already part of the self” (McMahon, 2008, p. 464). Nancy's ontology is challenging us to experience, not only the self, but the corporeal body as radically othered. The body as flesh, as organs, as bios, that for so long had been considered closed, bounded and border; this is the view that falls apart in intrusion. The persistent series of intrusions upon Nancy's body throughout his essay L'Intrús serve to derail any comfortable notions of self-identity or corporeal propriety. He does this to emphasize that the vulnerable and exposed body/self does not, in the end, return to a re-internalized, or even newly multiplied, body/self. Rather, Nancy, 2000, Nancy, 2002 asks us to experience the intruded upon body/self as remaining strange, arguing, “It is neither logically acceptable, nor ethically permissible, to exclude all intrusion in the coming of the stranger, the foreign.” To do so would be doing injustice to the experience of intrusion.

Nancy cannot remove, reconcile, recover, reset or master the intrusion that comes from a transplanted heart. There is no final moment of synthesis, recovery or ‘new normal’. Strangeness remains; the self constitutively exposed, and yet shared and collective because this: a sharing in exposure. The theme of intrusion speaks to Nancy's (2000) broader relational ontology outlined in the text Being Singular Plural where he destabilizes all comfortable assurances of self-autonomy, presence or enclosure, and attunes us to a sense of existence as co-existence, being as being-with, but in a way in which we are together but never fully united. The intrusive experience of the heart transplant was, however, unique in that it inspired a more careful reflection on this relational ontology with respect to the body. Nancy, 2000, Nancy, 2002 describes experiencing intrusion in such an immediate and embodied way that he is able to touch, feel and sense what was previously an intellectual exercise:

I feel it distinctly; it is much stronger than a sensation: never has the strangeness of my own identity, which I have always found so striking, touched me with such acuity. ‘I' has clearly become the formal index of an unverifiable and impalpable system of linkages. (p.10).

Attention attuned to the body, Nancy asks us not only to think, but to feel and sense the body/self as a persistent series of ongoing intrusions that this relational ontology brings to the fore. He does this in an effort to open up and expose an embodied sensation of the self as exposure, as exteriority, as already othered by the stranger always present within.

Intrusions, interruptions, reversal spacings, all signal destabilizing notions of essence, identity, intimacy. L'intrus is not only about identifying lists of how technology invades our lives, but of exposing us to sense / meaning of the world through an ontology of being singular plural (Nancy, 2000). Disturbed intimacy, through the sharing in exposure to one another, is a condition of meaning, it is meaning at work, an experience and exposition of sense. ‘Post’ COVID-19 recovery, resetting, rethinking; these are attempts to purify the heart of tourism. Nancy's philosophy takes us away from any interest in purification and instead goes to great lengths to establish an origin art exposure of the heart. Bringing to presence the more immediate strangeness at the heart of our being-together and the ageless intrusion of technology “Had I lived earlier, I would be dead; later, I will be surviving in a different manner” (Nancy, 2002, pages 2–3). Intrusion is material and metaphysical, philosophically asking us to consider the “I” as an extension that is infinite and an intimacy that is characterized by exteriority. A non-intimate intimacy that CoVid brings to the forefront. Nancy directs his very personal experience of a heart transplant to invite a philosophical reflection on the open and exposed relationality of the self, body and community, ultimately proposing: “The intrus is no other than me, my self; none other than man himself. None other than the one, the same, always identical to itself and yet that is never done with altering itself” (Nancy, 2000, Nancy, 2002). In other words, the heart transplant (or virus) intrusion opens a discussion of both our material experiences and metaphysical concerns—a material metaphysics—where Nancy uses a deeply embodied experience to carefully reflect on the metaphysical questions of self and body, or any other attempts at foundations, origins, essences. Experiencing the intruded upon body, as we all have experienced during this pandemic, albeit in different ways, exposes us to this relational ontology experienced through and with the body.

2. Philosophizing intrusion in tourism

We had not predicted that Nancy's reflections on the intruder would provide us with a new way of understanding the experience of COVID-19 in tourism. This was not an enquiry that began with identifying a problem, posing a question, and then followed a structured search for literature. Instead, it exposed itself out of our ongoing conversation on philosophy and life. Our friendship started at exactly the same time the pandemic was expanding over the world. We had been sharing with each other the ideas and works of authors and artists that we found inspirational, and for Adam, the philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy had been a major influence, already from the time of his graduate studies and his philosophical reflections on freedom (Doering, 2016), the creation of the world (Doering & Zhang, 2018) and communication (Zhang & Doering, 2022). To read Nancy's essay L'Intrus together came out of a sense of desperation and distress in the middle of the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, not because we thought we could connect the two, but because we hoped to find solace and joy in the engagement with a philosophical text. We were reaching out to philosophy as healing in a moment when we felt off and trapped both physically, through lock downs and travel bans, and intellectually through a long list of duties and exhausting online encounters, and when Ana had just experienced an unexpected and heartbreaking loss in her family.

Nancy's L'Intrus felt as an intimate space. He was sharing with us his reflections on a deeply troubling personal experience and teaching us how suffering had contributed to his understanding of self, others, the body, and the world. There is an element of boundless generosity in the act of philosophizing and sharing such reflections so that others such as we can enter that space; a seldom and precious vulnerability. It was once in that space that our own awareness and felt understanding of the pandemic, and of ourselves, was transformed. Reflecting on the pandemic and tourism together with Nancy's philosophy provides insights, which are not easy and do not give determined answers. Nancy does not shy away from the incommensurable and complex in existence, but it is precisely the courage to sense what cannot be explained or controlled that it becomes a source of consolation; it shows a way to be in the world.

This article offers a series of reflections inspired by three works: the philosophical essay L'Intrus, the online keynote lecture titled The World After the Pandemic that Nancy (2020a) gave at the BISLA Virtual Conference in Germany, and the film “The Intruder” (L'Intrus) by Claire Denis (2004) which is inspired in Nancy's essay. In L'Intrus, Nancy reflects on a deeply personal and intimate experience while showing how the particular can provide insights about the human condition. Humanity has known this through millennia—the art of storytelling, poetry and drama by illuminating the most particular reveals something about the commons, about ‘we’. This philosophical essay follows Nancy's L'Intrús way of approaching what is most particular as a door to reflect on the world and our common humanity. Nancy's point of departure was his experience of intrusion through a heart transplant, and in this article we reflect on two personal experiences of pandemic intrusion and tourism. We approach Nancy's fragmented philosophical writing as “a contingent practice of writing which traces diverse paths and traverses a multiplicity of specific philosophical contexts…a practice of thought which unfolds as a plurality of singular gestures or exposure to/at the limits of thought” (James, 2006, pp. 231–232). Such a nonsystematic approach to philosophical writing invites the reader to reflect on the experience of intrusion—its outlines, tonalities, dispositions—as a collage or open exposition; it does not conclude and it is not problem-based oriented. It adopts a critical approach where criticality is understood as vulnerable, curious and experimental engagement with the world. Furthermore, the way this article is written follows the ontological orientation of the philosophy of Nancy. For him meaning is not an intellectual exercise detached from existence, instead it is ‘being-with-one-another’, ‘we ourselves are meaning’ (Nancy, 2000, p.1).

We take up this inspiration to think, show, feel, sense and compose intrusion instead of analyzing it. Consider this form of academic writing as similar to an art exhibition where the participants can move from piece to piece and construct their own meanings based on their interactions with each work. We use “I” in these works as both of us contribute to the reflections. As our collective author name —AyA Autrui— shows, the reflections of this work are an expression of ‘us’. We write this article with the aim of challenging each other and the reader to become-other through writing, reading and thinking. The pieces combine philosophical reflection with ethnographic materials collected and developed from the autumn 2020 until summer 2021. In this paper we engage in a close reading with Jean-Luc Nancy's intrusion. This approach does not in any way discount other theoretical streams that might intersect with Nancy's such as new materialism, post-humanism, feminist philosophy or Socio-Technical System's theory.

Welcome to a philosophical journey with Jean-Luc Nancy into an experience of pandemic intrusion and tourism.

3. Are you ok?

Are you ok? She asks after the procedure of swabbing my nose is finished. I have lost count of how many tests I have taken, but a couple of weeks ago I knew this, it was a total of 14 tests since the beginning of the pandemic. Now, I did not care to count anymore. I was experiencing a higher level of exhaustion. I bow my head as if saying – yes, I am ok, which I am not. It is the first time I was asked this question; this is not part of the script of the medical personnel, which I have heard many times before. Is medical personnel the right term to describe her? Even professional categories seem to have been intruded upon during these months. This test facility with hundreds of workers is run by a private company ‘Copenhagen Medical’, employed by the state. The workers here do not need to have any medical degree. The logo of Copenhagen Medical is a star and I get an association to private military services.

I get teary and look away, pull the mask over my nose, take the piece of paper with the test attached to it, breathe deeply and stand up. This medical technology resembles a pregnancy test, a plastic pen with a window that shows one or two stripes. A plastic which now includes part of me and which I still do not know if it also includes a part of COVID-19 in me. Before those stripes had been the sign of another being in me, a human one. I had taken those tests in the intimacy of my bathroom at home, alone, waiting with expectation before the joy of a positive, holding the secret of another in me.

Testing is proclaimed from the posters around the city as the new ethical duty of responsible citizenship. This test was different to the many previous ones. I am done. I do not want any of this anymore, not even for the article, I do not care. I want to lie down under the trees just outside this ugly big white tent, forget everything and rest looking at their new leaves, which are so tender, just born, a promise of unconsciousness. The new leaves do not know, they begin opening to the world as an expansion of green hope, unaware of the global pandemic and the fall which is just around the corner.

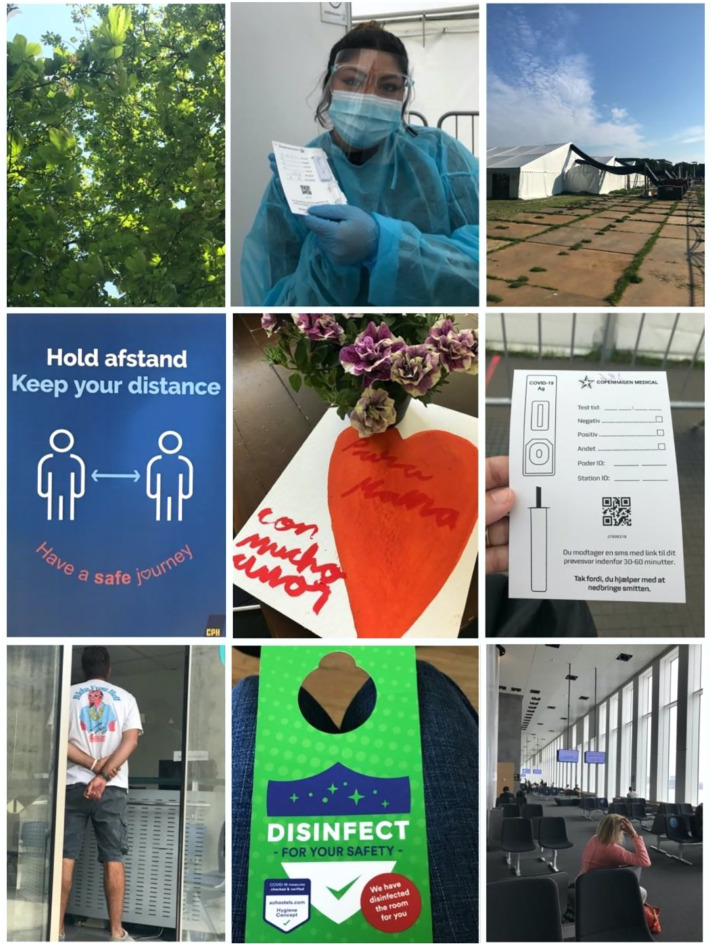

Those many tests I had to take were bearable, even interesting, because they were also research - collecting data and taking notes to be able to share with the world the experience of intrusion. But not this time. My husband had just been diagnosed with COVID-19 the day before, I was taking this test because I was quarantined out of my own home, had slept at a hotel in my own city, which welcomed me with a sign of ‘Disinfected’ hanging at the door. Disinfected is the new ‘Do not disturb’. Whenever I saw hotel rooms with a do not disturb sign I thought of couples making love or people sleeping at random times enjoying their freedom. It reminded me of the times when I was able to hang that sign in hotel rooms. Please, virus, do not disturb. ‘Disinfected’ - a sign to be hanged on my body at all times, a new mantra for the planet. My room is on the third floor, I am careful not to press the elevator button with my bare hands. I sit on the bed and look around experiencing a new sense of strangeness of my city and of myself, a new disturbance. “How does one become for oneself a representation? – a montage, an assembly of functions? And where does the powerful, mute evidence that uneventfully was holding all this together disappear to?” (Nancy, 2002, p. 3–4) My mind looks at me like from the outside, alone sitting in this strange space which was designed to be hospitable. My intruded ego races like a trapped mouse asking questions which resemble a paranoia of contagion—can I trust that they have disinfected this space properly? Who was I, what type of arrival home, what type of tourist was this, what type of hospitality? (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

The tourism system in pandemic times. Photo collage by Ana Maria Munar, 2021.

I had received the news of my husband as a text message on my mobile while waiting at the airport on the queue to another test. “Passengers arriving at Copenhagen Airport have to take a COVID-19 test” the message kept on repeating. I had the paper with another negative test result only 24 h old lying in my bag, which I had taken at a private hospital in Spain. All these tests were signed by names of strangers certifying my biological state to be shown to other strangers, stored in some virtual space I fail to imagine. Tourists had been queuing in that facility, the 2021 tourist season had just begun in Mallorca and private hospitals were catering to the many tourists that needed corona passes to be able to fly. This nurse (is she a medical ‘receptionist’?) is dressed from top to toe with protective clothing in white, vizier and mask, but I can see her tattoos while writing on the computer. In Copenhagen one of the swabbers had long fake eyelashes under the vizier, I loved that so much, I asked her if I could take her photo. She re-touched her hair and posed for it as if it was a party, holding my test as if it was a cocktail. Humanity has its magical ways of resisting being programmed and standardized. Kindness cracks through masks and viziers.

The tourists with sandals and masks seem restless while waiting. Some go to the desk to protest that it is taking too long, the nurse-receptionist tries to explain. They are shouting at each other in their English with foreign accents, they are barely understandable through masks and the large plastic shields that separate them. How is mask-suntanning going to be? Isn't this tourist's t-shirt text - “Aloha from hell” - the perfect outfit for COVID testing? I find my mind full of bizarre and random questions and reflections. My “I” as a traveler, I realized now, was connected to a multiplied web of medical personnel, statistical and sanitary experts, politicians and ministries, belonging and intruded by this fragmented community of “soon-to-be tested” beings.

The message was flashing on the screen on my mobile. I read it twice. I stopped and the queue began moving without me. Whenever we get messages as unsettling as this a ‘void’ opens – I have COVID. ‘The intrusion on thought of a body foreign to thought’ (Nancy, 2000, Nancy, 2002), the body of a virus that could be everywhere and in anyone. The stickers on the floor multiplied in front of me ‘Stand here. Have a safe journey’. The ‘o’ of journey is written like a heart. Your heart was meant to last only until you were 50 years old, was the message given to Nancy, “My heart was worn out, for reasons that have never been clear” (p.2). I am 50 now and I have no clue about the condition of my heart and what plans it has for my existence and subsistence. I can only sense it beating faster after reading the news.

Messages from other worlds made of numbers and laboratory tests so far away from our experience are taking home in my heart. Kill the messenger; I could if I was an ancient king, instead I am just a tired passenger on a queue. I am good at obeying the instruction. Stand here. Safe journey. What safety? The pandemic is the experience of fear says Nancy (2020a, 21:34). The experience for Nancy is what is different from our daily lives where we are mostly unconscious of being an estranged multiple self, where we have a sense of control and routine, and move along with our plans, listening to our ego chatter. Experience is a space where learning has not happened yet, instead the “I” is lost in experience, as we feel in the experience of falling in love, intense desire or intense fear. Like being suspended in a space where our idea of who we are recedes and the exposure to life intensifies. Our sense of self gets shattered. “In an experience “I” am lost or it is not really an experience…what is at stake in every experience is the loss of subjectivity because an experience has to a certain extend ‘no subject’ (Nancy, 2020a, 20:59)…the “I” of the experience is not the “I” of before and not the “I” of after”. “I have COVID” and I am standing there, on the ‘stand here’ sticker, and I am not there where I was anymore and I am not safe.

“Every passenger has to take a test”. I could hear the announcement trespassing the music from my headphones, a space of feeling where I could hide while waiting. Put the volume up, numb all these commands – please, let me drown in music. I could not go back home and was now part of the volatile and involuntary quarantine tourists in their own cities. I asked for a dispensation to enter my office at the university which I had not been in for eight months. “Have you been in contact with your husband?” did the secretary ask. An intrusion of intimacy that this time was different to feeling the stranger touching my nostrils. Now also my university secretary was part of my travel and health web of connections. Another layer of strangeness. Under intrusion things take place “only on condition that I want it to, and some others with me. ‘Some others’… I who find myself more double or multiple than ever” (Nancy, 2000, Nancy, 2002). Systems of experts and “some others” all have to agree to make mobility possible. I find myself praying that at least my test now will be negative so I can help my family quarantined at home. I sense the touch of the cotton pin inside the nose. I can't remember the face of who did it. I could draw a heart, but a nostril, that was a part of my body which I would not be able to describe even if I wanted, stranger to me in me. “Have you been in contact with your husband?” And why should I tell you? Instead I tap a brief message on my phone while waiting for the answer of the test, − No, I have not. From this waiting room at the airport I can see the airplanes as resting iron birds.

Contact. Touch. Embrace. “No, I have not”. My heart hurts.

Are you ok?

4. Am I ok?

“Are you ok?” Whose asking? Ana? My computer? Ana through the computer, to me, then on to you? In quasi-lockdown am I asking this to, or about, my “self”. Am I ok? I mean who do I respond to? And where do I respond? Do I need to share these questions and experiences on screens, through messenger, on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter or TikTok for these feelings to exist? What is all this: screens and software, electronic emotions, affect through apps, computers combined with care, tenderness, and friendship…pandemic life?

Although we are writing this piece together, I hardly know the physical Ana. We briefly spent time together at the very early stages of the pandemic in February 2020 during the Critical Tourism Studies Asia Pacific conference in Wakayama, my currently adopted home. Since then I remain in pseudo-lockdown and in a hesitant isolation as part of the Japanese government's key policy to prevent the spread of the virus, jishuku, meaning voluntary self-restraint. There is something fascinating about this virus self-restraint. On the one hand, jishuku presents a call for collective self-isolation, confinement and distance. Together apart, apart together: the new slogan of pandemic life. On the other hand, never has the possibility of self-sufficiency been put into question, or fragilized as much as during the pandemic (Nancy, 2020a, 25:15). During the pandemic one feels, senses, and experiences more than ever an embodied self as interactions, complexes, entangled bodies and bacteria, and a melee of desires. No one is left alone, no one left untouched, no one ever apart. I dwell on the (im)possibility of voluntary self-restraint. I understand the managerial language and generally agree with its purpose, but I cannot pretend my “self” has been restrained. Fractured, fragmented, shattered, and multiplied may be more accurate language for the experience of my pandemic self. Perhaps my body appears restrained, but like Nancy's transplanted heart, the virus intrudes upon the very idea of an autonomous self or an autonomous body. It is the appearance of a body detached from others and self-restrained that makes its porosity even more poignant.

During the pandemic spring of 2021, I often wandered the Faculty of Tourism alone. We are instructed that those who live close to campus can still come to the office, but the abandoned hallways reveal most staff do not live that close to their place of employment. Despite my position as ‘the foreigner’, I notice I am not the only stranger to this place. The ruins of academia remind me of walking through abandoned villages and coastlines in the “difficult-to-return zones” of Fukushima (Doering & Kato, 2022). Emptied streets, halls, and classrooms, a place evacuated of humans, while the stray cats of the neko bu [Cat Club] and the inoshishi [wild boar] are free to roam (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The difficult-to-return to zone of Wakayama University during self-restraint. Photos: Adam Doering, April 27, 2021.

The university has become a difficult-to-return zone. The campus opens and closes in response to a human-to-human virus transmission valleys and peaks. Nuclear fallout and a globally circulating virus make us all hesitate and carefully plan our returns to or evacuations from places we love, care and long for.

A heart transplant (Nancy, 2000, Nancy, 2002), Fukushima's triple disaster (Nancy, 2014), and now a global pandemic (Nancy, 2020a), Nancy exposes just how complex and vulnerable the human experience is within the current techno-global entanglements. He argues that “There are no more natural catastrophes: There is only a civilization catastrophe that expands every time” (Nancy, 2014, p. 34). Faculty and Fukushima emptied by catastrophe, producing a familiar and recurring bio-techno-political strangeness that are no longer isolated incidences. Perhaps we are all strangers now. Or more accurately, for the first time the virus intrusion instigates an embodied experience of the uncanny strangeness of our collective being. “People are strange”, writes Nancy (2000, p. 5), ontologically strange, because from the start there is never a pure heart, a pure people, an autonomous self, impenetrable body, or proper existence. Intrusion is a reminder of this collective, entangled, ontological strangeness.

And like Fukushima, the pandemic experience of intrusion also invites a renewed appreciation of ongoingness, of how we make do in disastrous times (Doering & Kato, 2022). For better and for worse, the pandemic experience has accentuated a sense of online ongoingness. As with all pandemic communications with family in Canada, globally dispersed friends and colleagues, and students connecting with me from their hometowns spread across Japan, Ana and I have communicated through screens. The photos and messages sent back and forth through the ether between Wakayama, Denmark, and Spain have offered a sense mobility within immobility. I travel vicariously, virtually. My pandemic summer holidays experienced as a virtual trip to the pines and seas in Mallorca (Fig. 3). I had never been to Spain before. Now I know the pandemic procedures, palms and pines of Mallorca almost by heart.

Fig. 3.

Vicarious travel in trouble times: Pandemics, palms and pines in Mallorca, Spain. Photos: Ana sent to Adam on March 6, 2021.

I am the virus and screen. The disease and the remedies cut through me. My self and body so obviously comprised and compromised of all that is exterior to me, or exteriority ‘in’ me. I both love and despise this. As Nancy, 2000, Nancy, 2002 writes of intrusion, “what cures me is what infects or affects me.” In the viral world of the Internet, I am simultaneously never more connected while also further embedding online processes and systems that enclose, isolate, and distance. Regardless how I feel about all this amplified screen time, it is a necessity for pandemic survival—for the time being, for this being in time. Emotions expressed as Facebook posts. Frustrations, anxieties and joys shared through messenger. Daydreaming during an online conference I wondered if during this self-restrained isolation whether or not emotions existed if they were not shared online. Have my feelings become one-way traffic? Who owns these emotions?

Pandemic life online. My career as a tourism academic and educator also apparently dependent on increased screen time. Hyper-academia and it's hyper-digital cultures expanding and intensifying as never before (Munar, 2019). Students and teachers resigned to Zoom headshots or blank face spaces with names. I have spent most of my early teaching career learning about the value of embodied and affective pedagogy. I had moved some way to understanding how to do this when I established a class to take students to the sea, to surf, to feel, to live, to sense, in other words to study. Alone at my desk, I can still smell the ocean breeze entering through my office window while teaching on Teams. Can the students? Sensing the sea cannot be taught online.

My body does not respond well to this ever-expansive digital experience. My eyes burned by the screen as if having gazed directly at the sun. Migraines come and go with increasing frequency. I play around with the lighting in the hopes that today I won't see sun spots. I am these techno-intrusions and my resistance to it all. I am a body that responds, reacts and calls for my attention in ways it had not done before. I am these metaphysical questions and techno-material becomings. There is no separation between the two. I am heartbroken by it all, but a beat keeps pulsing through machines. Relations twisted together by wires and Wi-Fi. That we continue—to live, to make do—this makes sense, is making sense. The intrusion of the virus—like the heart transplant—bringing with it an embodied awareness of the fusion between self and screen, heartbeat and technology, and ultimately that we are both more machine and more human than we think. Perhaps it has always been this way.

As electronic texts, images and emotions circulate, my body remains in place. The virus brings forth the sensation of feeling simultaneously lockdown in place and detached. In contrast to Ana, I have not been travelling over the past two-years. The invasive feeling of a stranger penetrating my nostrils remains strange to me. I have little experience with the pandemic travel medical machinery. From where I write in Japan, this all still seems so distant, removed and cold. I stay put, but I am desperate to move again. I needed to not be here, in this place. My teenage daughter and I had been planning our return home to New Zealand set to depart on March 14, 2020, the very same day the government announced anyone entering New Zealand must self-isolate for 14 days, and three days after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 to be a global pandemic. In the weeks leading up to this closure of country, I would tell anyone who would listen how necessary it was to briefly leave Japan and return to one of my adopted homes in Dunedin. I needed time. Time to contemplate, reconnect and converse in the comforts of my dearest friend's living room. In anticipation of the trip, I would close my eyes and picture the fireplace and floor-to-ceiling bookshelf filled with philosophical and post-colonial adventures, mini-escapes and mental openings that would eventually inspire further discussion and writing. My daughter had plans to reconnect with childhood friends and explore possibilities of attending high school there.

The night before leaving, we went souvenir shopping. The search for the right gift was a practice of remembering, of centering our attention on what puts a smile on the faces of friends and family. It was at this moment that a message arrived on the screen on my phone, “I'm hating this but I think it might be getting too tough to come. I'm crying. I love you both.” I stood paralyzed in the middle of the shopping mall. The virus made those who care for me so much, now ask me not to visit. It took seven hours before I could respond, “We cancelled everything last night. I am devastated.” Memories and histories drift off to a distant horizon, while my daughter's possible futures irreconcilably altered.

Strangely, I have never felt so close to these home(s), friends and family who have never felt so far away. There is an uncanny intimacy in this pandemic induced distance. A pandemic intimacy that is incalculable, immeasurable, in terms of physical distance. Contrary to popular discourse concerning pandemic proximity, I do not rediscover an intimate being re-localized. I do not experience a renewed intimacy with my local surroundings or proximity to place. Intrusion makes these places distant and strange too. Whether I stay still or join the pandemic tourism machinery to ‘visit friends and relatives’—a phrase that says far too little—there is no overcoming or excluding the virus intrusion. However, no matter where one is located, intrusion exposes and discloses a feeling of intimacy. For Nancy, intrusion is at the heart of intimacy, not something that is deeply internalized, self-possessed or self-defining (Adamek, 2002). Intrusion disturbs, exposes, and opens up the self to an experience of intimacy. There may be no return to the past or recovery of lost futures, but there is an emergent experience of intimacy with these histories, futures, peoples and places, renewed each time, each in their own strange ways, and always arriving by surprise.

And so I linger in strangeness. My own home, my multiple homes, as well as the systems and desires that produce(d) them, all disturbed by the experience of intrusion. It's as if all my desires have suddenly become strangers to themselves. My own heart—not the virus—exposing me to the strangeness within myself. Nancy, 2000, Nancy, 2002 words resonate here:

My heart was becoming my own foreigner—a stranger precisely because it was inside…A void suddenly opens in my chest or soul—it's the same thing…A strangeness reveals itself “at the heart” of what is most familiar—but familiar is to say too little: a strangeness at the heart of what never used to signal itself as “heart”. (p. 4)

An intrusion from within. An intruder that was always already there. All the world outside beating at the bones and flesh just under my rib cage, the intruder exposes me at the very core of my being, invading both body and self. “I am closed open” (Nancy, 2000, Nancy, 2002). The coronavirus pandemic is, on every level, a product of globalization (Nancy, 2021). I too am the global pandemic machinery and human-techno tool of tourism ‘recovery’, which is already well underway. “I am the illness and the medical intervention…” writes (Nancy, 2000, Nancy, 2002), “…the intrus is no other than me, my self; none other than man himself”.

Exposed, shattered, uncertain. Are we ok?

5. Are we ok?

5.1. The body exposed

For decades, the whole imaginary and theoretical world of tourism relied on the metaphor of mobility or immobility of ‘the body’ as entity. Tourism understood as the phenomenon of individual self/bodies moving in space. A tradition of theorizing tourism and the tourist rely on the basic premise of our bodies as containers of self: classical anthropological understandings of the man away from his usual habitat (Jafari, 1987) who travels to fulfill a need and adopts a role or theatrical identity (MacCannell, 1999); existentialist perspectives of the conscious subjective self engaging in the tourism experience (Wang, 2000); postmodern understandings where tourism is the result of the tourist's self/body relating to the world through gazing (Urry, 1990), performing (Edensor, 2001) or worldmaking (Hollingshead, 2009); and critical perspectives where the tourist is the archetypical representation of the evolution of late modernity and positioned in ontological opposition to the citizen (Bauman, 1998; Ek & Tesfahuney, 2016). Touristic selves and hosts are othered through culture, roles, norms, language, atmospheres, materialities, systems and technologies, always embodied in body-entities which are theorized as belonging to oneself. Selves that can be captured and shared in photographic shots as ‘me’ or ‘you’, and travel in space through destinations as if the skin and its contour was another type of border not to be crossed while crossing into foreign spaces. The whole statistical and monitoring understanding of tourism relies on the tourist body as the unit of measure—the adding up of each distinct tourist body.

Tourism theoretical discourse has realized that when we speak we are spoken (Pernecky, 2012). While the self (the “I” of speech or of consciousness) has long been understood as interior-exterior otherness, our theoretical imaginary has not done the same with the body. What difference does Nancy's philosophy of intrusion make to how we think tourist bodies? It is the closed-openness of our bodies, and consequently an exposed relational ontology, that intrusion exposes. This is what we see in the fear of touching the button in a hotel's elevator, in the saliva of a COVID-19 test, in the word ‘contact’ becoming synonymous with ‘danger’, in the contradictory affectivity of walking through empty spaces both safe and inhospitable, in the imposing of self-restraint at the very moment that we realize that nothing in our corporeality is restrained.

Our personal accounts of intrusion portray the end of an era where we believed touristic bodies and selves where individual containers. We have lost sense of our own contours, our breaths and our embraces transformed into what causes suffering and death. We have also lost the way we understood the corporeality of daily-coexistence. A hug, the sharing of a meal, being able to see each other's smile, the small taken-for-granted habits of hospitality suddenly revealed to us as extremely valuable, precarious and risky. The collage of memories expose that we are also the traces of ourselves, much more outside and much more intruded upon than we ever imagined. They show, that we are still there when we are there no longer and that we do not know what (who) we are. Nancy's philosophy of intrusion invites us to break out of a long scholarship tradition of thinking of the body as the last bastion of unity of being and subjectivity. Can a body and a self without mastering and control be OK? Can we be OK if we are closed open?

5.2. Shattered selves and the tourism experience

The tourism sector promised and designed the tourism experience1 as the finding of oneself. Intrusion shows us an experience of tourism which is about exposing oneself, a shattered self. It is worth mentioning how Nancy's understanding of experience differs from how the experience economy (Pine & Gilmore, 1999) and tourism marketing (Prebensen, Chen, & Uysal, 2014) popularized this concept. While the latter focus on how to capture tourists' subjective experience to allow for tourists' mastering levels (Prebensen, 2021), and on how to teach businesses to design and plan tourism experiences (Mossberg, 2007). Nancy's intrusion reveals the opposite, for an experience to be an experience it can't be planned or controlled.

A human experience is only an experience as long as it is characterized by its newness and by ‘not knowing’. The management of experience is a contradiction in terms - “In an experience, I am lost or it is not really an experience” (Nancy, 2020a, 12:25). Similar to the personal experience of a transplanted heart, the COVID-19 pandemic is a global tourism experience of intrusion, of confronting how a stranger parasite virus is already us. Like when feeling lost quarantining in a hotel, receiving the news that one's loved ones are infected, or when a text message shatters the dreams of a long desired travel to meet with a dear friend, in these tourist experiences we can't make sense or find reasons—a void opens. Our narrations of intrusion depict our desires becoming suddenly strangers to ourselves, our habitual forms of intimacy disrupted, and new forms of longing and care exposed. We feel shattered and stand paralyzed in the middle or airports and shopping malls. It is only afterwards, once the experience has passed, that we try to come up with reasonable explanations for what happened.

An experience is the opposite of what Nancy names ‘the program’ (2020a, 22:18). The program is the expression of humanity's desire to plan and control. The culture and habits of the developed world, he mentions, have for a long time being devoted to the program; giving humans the sensation (and consolation) of feeling that they could master their lives and their futures. Similarly, a long tradition of tourism management and planning has been devoted to ‘the program’, to the mastering and control of the tourism experience. Instead, the experience of intrusion in tourism, as well as in our lives, offers nuanced insights not so much as to how one may recover or overcome intrusion, but how to think through the arrival of intrusion in a way does not force assimilation or control.

Nancy's writing is not so much about arguing for a set of theories, ideas or concepts, as it is about listening and attuning oneself to an experience of intrusion, experiencing that which is being expressed through intrusion. He presents us with a felt understanding of intrusion by dissecting the tensions between integrity of the self and the threat of the stranger, preservation and exposure, tenderness and destruction, body and machine, metaphysical questions and technological assemblages (Geroulanos & Meyers, 2009; McMahon, 2008).

5.3. From now on…

The personal reflections on the pandemic offered throughout this article express what Nancy (2020, p.32) refers to as a “difficult-to-justify strangeness”, arguing that “Everything occurs as if tragedy indicated both the very clear circumscribing of the law…”—as in the global managerial ‘shoulds’ and ‘shalls’ of pandemic prevention measures—“…and its unknown, uncontrollable, vertiginous, worrisome, fascinating beyond.” Humanity has difficulty dwelling in this strangeness. We try to manage the experience of exposure, of the intruded upon body, through a new series of social acts and bureaucratic decisions that have become global in nature: the keeping of the two meter distance, the wearing of masks, the disinfection of hands, the expansion of online encounters and communication, the corona passport and the rituals and proofs of tests and vaccination(s). Reflecting specifically on the corona virus, Nancy (2021, p. 64) writes of a concern that “the contagious brutality of the virus spreads as administrative brutality”. The mass reproduction of these acts composes a new touristic imaginary and discourse, a new biopolitics of tourism. It exposes an emergent transformation of a culture of travel, which is trying to ‘naturalize’ and turn the experiences of this embodied strangeness, exteriority and exposure into a new managerial ‘program’. The corona passport, vaccination, test and quarantine protocols, distancing and disinfecting habits compose the early structure of the program trying to master intrusion—the forced suturing of something that had been revealed, exposed, opened.

Frontiers reopen and travel resumes, like Nancy being sensible to the medical treatments that keep his intruded upon body alive, the mark of the pandemic trauma is most acutely felt in our sensitivity of either the presence or absence of the pandemic social practices. The behaviors and protocols, which manifest the biopolitics of the pandemic, are not stable. They mutate, multiply and adapt to specific local cultures and politics. In Japan, where Adam lives, the extensive use of masks in all public spaces appears permanent while in Denmark, Ana worries that no one uses them anymore, not even in the metro.

We see before us a new landscape of ethics in tourism which is forming around the polemics and the moralities of these new social acts; should we wear a mask, should/can we self-restrain, should/can we get vaccinated? Reflecting back on all the sufferings and difficulties he confronted during his heart transplant, Nancy asks, “Who can say what is ‘worth the trouble’ and exactly what ‘trouble’?” (Nancy, 2000, Nancy, 2002). Is travel worth the trouble? Who can say what we would be willing to do to embrace our loved ones, or to see other places and other worlds? All the ethical considerations that are born out of intrusion don't bring us back to any ‘normal’, but expose us to the possible tourism futures already well underway, that we are already doing.

Nancy's intrusion reveals how the experience of the global pandemic is also our shared experience of failing immune systems, a perturbation of intimacy that does not cease, of our common biological being making its strangeness known, an experience of fear, uncertainty and ‘not knowing’. This reveals the being of the body as exposed, closed open, and adding up to nothing more the “stream of unremitting strangeness” at the very heart of the self (Nancy, 2000, Nancy, 2002). What we have learned from the philosophy of intrusion is that we cannot go back to who we were the moment we met in February 2020 at the Critical Tourism Studies Conference in Wakayama, that Adam and that Ana do not exist anymore, there are no ‘normal’ you or ‘normal’ I. We are infinitely exposed, opened and transformed through intrusion, as expressed in our memories.

Nancy's philosophy takes us away from any interest in purification to share with us the art of living with an exposed heart. What if we do not try to force, control or manage such intrusion too much? What forms of collectivities, relations, practices, politics or ethics might surface if our starting point is to dwell a little longer with the experience of intrusion, deeply, with our bones and blood, with our closed open hearts? Experiencing intrusion is like sensing the beating of an exposed heart, vulnerable and uncertain, yet shared, embodied and full of life. One finds consolation in an ocean breeze entering through our office window, or gleam of hope in the summer leaves opening right outside a plastic test-center tent. Nancy, 2000, Nancy, 2002 goes to great lengths to remind us that in the end there is no final purification of his strange heart, and in this act of keeping his self/body exposed and open, Nancy clearly embodies the richness in the incompleteness of life. He reveals that humanity too is always already exposed, strange and othered, and that there are no ‘points of equilibrium’ or ‘standards’ or ‘reason’ to recover, that there never were, and that “meanwhile the world goes on”, we find our way (Nancy, 2020b). Our thinking with intrusion is a double invitation to reflect on how to live in common when there is no sufficient reason, and to explore how insufficiency and uncertainty are also a powerful force (Nancy, 2020a, 1:01:59).

Re-covery, re-thinking, re-setting, re-newing, re-starting, or any other term including the prefix “re” may be useful terms for industry and management, but does little to help us engage with this pandemic experience of the unknown, uncontrollable and ‘fascinating beyond’. There is no going forward, if by going forward implies a known fixed point just on the horizon to be realized or achieved. There is only from now on, which as Nancy (2021) describes it, is what makes sense, is already making sense. To experience intrusion is the same thing as to experience love, to experience humility, to experience the generous uncertainty of life in all its complexity and contradiction. Although thinking through intrusion does not provide any final answers or solutions, perhaps this sense of experience may also be an instructive way forward for the kinds of thinking and action needed to engage with the question of how to live, how to go on living with and doing tourism, and how to make do in a world of exposed bodies, shattered selves and uncertain futures.

Disclaimer

The first time we introduced the connection between the philosophy of intrusion of Jean-Luc Nancy and COVID-19 in tourism and hospitality was in a brief text of two pages (740 words) aimed at hospitality academics and practitioners: Munar, A. M., & Doering, A. (2020). COVID-19 the intruder: A brief philosophical reflection on strangeness and hospitality. Hospitality Insights, 4(2), 5-6. Later on, we also published an extended abstract of this philosophical essay in Aya Autrui, Doering, A. & Munar, A. (2021). COVID-19 the Intruder: Reflections on Hospitality and Justice. Abstract from the conference Critical Tourism Studies – North America. Justice, Mobility & Power: In Search of Ethical Encounters in Tourism, Montreal, 19-22 June 2021.

Credit author statement

Statement of contribution: We have written this article together - reading, discussing, commenting on the text back and forth. It is not possible to divide the contribution of each one of us into a percentage. The article is the expression of a true co-authorship, of us thinking together. As our collective author name —AyA Autrui— shows, the reflections of this work are an expression of ‘us’. The article combines philosophical reflection with ethnographic materials collected and developed from the autumn 2020 until summer 2021. The article includes two personal ethnographic narrations, one written by Ana and one by Adam.

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this article to Jean-Luc Nancy. Nancy died the 23rd of August 2021, in the middle of the writing of this article. He had lived with his transplanted heart for thirty years, a heart that keeps on beating in his work and in ours. We are deeply thankful that he thought it worth the trouble to live with intrusion. We are grateful to the organizers and participants of the conference Critical Tourism Studies – North America: Justice, Mobility & Power: In Search of Ethical Encounters in Tourism, Montreal, 19-22 June 2021, where we presented this article for the first time. Thank you to Karen, for her always inspiring company and for being the first to point out how a new landscape of social acts was beginning to take form in our world. To the pine in Son Verí, which provided countless hours of company and consolation while writing. To our loved ones, thank you for being-with us.

Biographies

Ana María Munar is Associate Professor at Copenhagen Business School, Denmark. Her research applies philosophical approaches to gender, higher education and tourism. Her book “I am Man” is a poetic philosophical work on gender identity and expression. And in her book “Desire: Subject, Sexuation and Love ” she applies psychoanalysis, philosophy, art and literature to explore what desire means for our human condition. Her ongoing work in tourism focuses on philosophizing tourism, gender and tourism sustainability and on creative writing. Her gender research combines academic reports and publications, with advocacy and action research projects.

Adam Doering is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Tourism at Wakayama University in Japan. A graduate of the University of Otago (2013), he has published broadly on tourism, sustainable transportation, lifestyle sports, and coastal development in the context of Japan. A theoretical thread weaving through all of this work is the concept of relationality. Inspired by the philosophy of Jean-Luc Nancy, he approaches relationality not as a comfortable enclosure into pre-existing groups, self, or body, but as a shared exposure to one another other and the non-human world.

Footnotes

We acknowledge that the word ‘experience’ can be translated in different ways and multiple words in other languages. In this article we are always referring to the way the word experience is used in tourism scholarship in English.

References

- Adamek P.M. The intimacy of Jean-Luc Nancy’s “L’Intrus”. CR: The New Centennial Review. 2002;2(3):189–201. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman Z. Polity Press; Cambridge, UK: 1998. Globalization: The human consequences. [Google Scholar]

- Denis C. 2004. L’Intrus [motion picture] France. [Google Scholar]

- Doering A. In: Motion pictures: Travel ideals in film. Blackwood G., McGregor A., editors. Peter Lang; Bern, Switzerland: 2016. Freedom and belonging Up in the Air: Reconsidering the travel ideal with Jean-Luc Nancy; pp. 109–134. [Google Scholar]

- Doering A., Kato K. In: Socialising tourism: Rethinking tourism for social and ecological justice. Higgins-Desbiolles F., Doering A., Chew Bigby B., editors. Routledge; 2022. In search of light: Ecohumanities, tourism and Fukushima's post-disaster resurgence; pp. 175–194. [Google Scholar]

- Doering A., Zhang J.J. Critical tourism studies and the world: Sense, praxis, and the politics of creation. Tourism Analysis. 2018;23(2):227–237. doi: 10.3727/108354218X15210313504571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edensor T. Performing tourism, staging tourism: (re) producing tourist space and practice. Tourist Studies. 2001;1(1):59–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ek R., Tesfahuney M. In: Tourism research paradigms: Critical and emergent knowledges. Munar A.M., Jamal T., editors. Bingley; Emerald: 2016. The paradigmatic tourist; pp. 113–129. [Google Scholar]

- Geroulanos S., Meyers T. A graft, physiological and philosophical: Jean-Luc Nancy's L'Intrus. Parallax. 2009;15(2):83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Grimwood B. On not knowing: COVID-19 and decolonizing leisure research. Leisure Sciences. 2021;43(1–2):17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead K. The “worldmaking” prodigy of tourism: The reach and power of tourism in the dynamics of change and transformation. Tourism Analysis. 2009;14(1):139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari J. Tourism models: The sociocultural aspects. Tourism Management. 1987;8(2):151–159. [Google Scholar]

- James I. Stanford University Press; 2006. The fragmentary demand: An introduction to the philosophy of Jean-Luc Nancy. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell D. University of California Press; Berkeley: 1999. The tourist: A new theory of the leisure class. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon L. Figuring intrusion: Nancy and Denis. Contemporary French and Francophone Studies. 2008;12(4):463–470. [Google Scholar]

- Mossberg L. A marketing approach to the tourist experience. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism. 2007;7(1):59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Munar A.M. Hyper academia. International Journal of Tourism Cities. 2019;5(2):219–231. doi: 10.1108/IJTC-12-2017-0083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nancy J. Michigan State University Press; East Lansing, Michigan: 2002. L’Intrus. (S. Hanson, Trans.) (Original work published in 2000) [Google Scholar]

- Nancy J.L. Stanford University Press; 2000. Being singular plural. [Google Scholar]

- Nancy J.L. Fordham University Press; 2014. After Fukushima: The equivalence of catastrophes (C. Mandell, Trans.) [Google Scholar]

- Nancy J.L. BISLA virtual conference: The world after the pandemic. Central European University and Bard College in Berlin; Germany: 2020, May 30. Keynote and discussion with Jean-Luc Nancy.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9767jLuJib4&t=3021s [Google Scholar]

- Nancy J.L. Seagull Books; 2020. Doing. [Google Scholar]

- Nancy J.L. In: Coronavirus, psychoanalysis, and philosophy: Conversations on pandemics, politics and society. Castrillón F., Marchevsky T., editors. Routledge; 2021. A much too human virus; pp. 63–65. [Google Scholar]

- Pernecky T. Constructionism: Critical pointers for tourism studies. Annals of Tourism Research. 2012;39(2):1116–1137. [Google Scholar]

- Pine B.J., Gilmore J.H. Harvard Business Press; 1999. The experience economy: Work is theatre & every business a stage. [Google Scholar]

- Prebensen N.K. In: Women’s voices in tourism research. Correia A., Dolnicar S., editors. 2021. Consumer experience.https://uq.pressbooks.pub/tourismknowledge/chapter/consumer-experience-contributions-by-nina-k-prebensen/ [Google Scholar]

- Prebensen N.K., Chen J.S., Uysal M.S. In: Creating experience value in tourism. Prebensen N.K., Chen J.S., Uysal M.S., editors. CABI; Oxfordshire, UK: 2014. Co-creation of tourist experience: Scope, definition and structure; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Urry J. Sage; London: 1990. The tourist gaze: Leisure and travel in contemporary societies. [Google Scholar]

- Wang N. Bingley; Emerald: 2000. Tourism and modernity: A sociological analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.J., Doering A. The interface of culture and communication in tourism. Tourism, Culture and Communication. 2022;22(2) doi: 10.3727/109830421X16296375579543. Online First. [DOI] [Google Scholar]