Abstract

The purpose of this study is to diagnose herpesvirus infections in refractory atypical trigeminal neuralgia, to assess pathogenetic links, and to explore the efficacy of antiviral treatment. In a prospective controlled study, 95 patients with trigeminal neuralgia received antiviral therapy (valacyclovir + alpha2b-interferon) (experimental group, EG). Other patients refused to receive treatment (control group 1 (CG1), n = 31). Control group 2 (CG2) included 32 healthy individuals of the same age and sex. Herpesvirus infection was diagnosed in blood leukocytes by PCR (Biocom, Russian Federation). Serum concentrations of IgM, IgA and IgG to HSV-1/2, VZV (ELISA, Vector-Best, Russian Federation) were determined. Reactivation of herpesvirus infections was observed in the EG in 87% of cases. The heterogeneity of herpesvirus-associated damage of trigeminal nerves and anatomically related areas of the central nervous system (CNS) has been demonstrated. The treatment applied was effective for herpesvirus infection (77%) and pain (61%) and ineffective for immunity correction (26% of cases). Atypical refractory trigeminal neuralgia is associated with herpesvirus infections that reactivate due to minor immunodeficiencies. Antiviral treatment suppresses herpesviruses and reduces the intensity of pain.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13337-022-00769-9.

Keywords: Valaciclovir, Recombinant alpha 2b-interferon, Immunodeficiency, Immunotherapy

Introduction

Trigeminal neuralgia is a common severe disease which can be divided into classical and atypical variants that are difficult to treat [1]. One third of cases are characterized by resistance to the recommended treatment. In such patients, the quality of life is significantly impaired due to intense debilitating neuropathic pain and side effects of the pharmacological therapy.

The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3), emphasizes the heterogeneity of trigeminal neuralgia. Handa et al. [2] give the classification of pain syndromes in the area of trigeminal nerves innervation according to the International Classification of Orofacial Pain (ICOP), 1st edition, which includes trigeminal neuralgia (TN), burning mouth syndrome (BMS), persistent idiopathic facial pain (PIFP), and post-traumatic trigeminal neuropathic pain (PTTNP).

One of the major causes of classic trigeminal neuralgia has been identified. It is the compression caused by neurovascular conflict. The use of decompressive surgery can relieve pain or improve pain control [3]. However, the mechanisms of atypical trigeminal neuralgia are still unclear in many cases. This leads to diagnosing idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia and narrows the treatment strategy applied to symptomatic analgesic therapy.

Evidence suggests that one of the causes of trigeminal neuralgia may be reactivated herpesvirus infection [4–6]. Normally, herpesvirus infections are endogenous because they are present in the body of most people. Thus, alpha herpesviruses are found in the sensory nerve ganglia, and beta and gamma herpesviruses are found in the salivary glands. Reactivation of latent/persistent forms of herpesvirus occurs under conditions of immunosuppression. Modern concepts of the diagnosis and treatment of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia and elucidation of the etiological role of herpes simplex virus type 1 in the genesis of facial nerve neuritis allows paying close attention to the possible association of atypical trigeminal neuralgia with herpes virus infections. At present, herpesviruses are seldomly regarded as the cause of trigeminal neuralgia. Consequently, the problem is narrowed to cases of postherpetic neuralgia in patients who have suffered from herpes or zoster sine herpete. However, the relationship between herpes infection and trigeminal neuralgia may be closer since not only alpha, but also beta and gamma herpesviruses may be involved. Moreover, both direct and indirect mechanisms of trigeminal nerve damage are of concern. At the same time, monitoring of patients with trigeminal neuralgia indicate that pain syndrome was often preceded by the manifestations of herpes virus infection. In particular, this was rash on the lips, skin and mucous membranes, periodic or persistent subfebrility, lymphadenopathy, and changes on the brain MRI [7].

The relationship between herpesvirus infections and the development of trigeminal neuralgia is complex. It may include a multitude of different pathogenetic mechanisms, which can be divided into direct and indirect ones.

Direct virus-induced mechanisms are associated with the direct involvement of the trigeminal system, as in acute ganglioradiculoneuritis with VZV reactivation [8]. Cases of zoster sine herpete should be considered, accounting for at least 10–20% of all herpes zoster episodes due to which postherpetic neuralgia can be mistakenly taken for idiopathic facial pain [9]. Gilden et al. [5] described chronic VZV ganglionitis of the gas site as a cause of refractory trigeminal neuralgia. Instead, Ramos F. [10] reported acute sensory neuropathy caused by VZV as a cause of persistent pain. Liu et al. [11] recommended to use the term herpes zoster-related trigeminal neuralgia to describe all forms of lesions of the trigeminal system of VZV etiology.

Other types of herpesviruses may induce the development of trigeminal neuralgia/neuropathy by the mechanism of direct damage. In 1976, Krohel et al. [6] described chronic HSV-1-induced trigeminal neuropathy was described. Later, Stalker [12] reported persistent facial pain in recurrent orofacial herpes caused by HSV-1/2. Accordingly, Roullet et al. [13] described the clinical and pathomorphological picture of multifocal neuropathy caused by CMV in immunocompromised patients. Farahani et al. [14] reported severe trigeminal trophic syndrome in an immunocompromised patient with recurrent oral mucosa ulcers of CMV etiology. Hüfner et al. [15] demonstrated that HHV-6 DNA along with alpha-herpesvirus DNA is present in the sensory nerve ganglia of cranial nerves. These data were confirmed by the results of pathomorphological research conducted by Ptaszyńska-Sarosiek et al. [16]. Based on the paper, HHV-6 DNA was found in sensory ganglion neurons of cranial nerves more often than HSV-1 and VZV DNA [15, 17].

Indirect mechanisms of the development of trigeminal neuralgia during reactivation of herpesviruses (which include compression, ischemic, autoimmune and neurodegenerative lesions) are actively discussed. Heterogeneity of such mechanisms has been established, including the induction of autoimmune reactions to myelin and neurons, development of virus-induced vasculopathies with ischemic lesions of trigeminal nerves, cavernous sinus thrombosis at the anatomic trigeminal nerve sites, development of virus-associated tumors and pseudotumor lesions with secondary involvement of the trigeminal nerve fibers located at different anatomic sites, as well as disturbances in central pain regulation, including data on the relationship between HHV-6 and development of temporal mesial sclerosis [4, 18–20]. Thus, confirming the association between refractory facial pain and multiple sclerosis, Li et al. [21] proposed to separate classical trigeminal neuralgia (CTN) and trigeminal neuralgia secondary to multiple sclerosis (MSTN) as different nosologies. Damage to the structures of the brain mesolimbic system, which occurs in virus-induced temporal mesial sclerosis [20] or autoimmune limbic encephalitis caused by autoantibodies to hippocampal neuron autoantigens [1], leads to the impairment of the mechanisms of central pain regulation in the central nervous system. Adachi [4] reported a pseudotumorous lesion of the lingual-pharyngeal and vagus nerves of VZV etiology with a clinical picture of refractory facial pain. There are descriptions of persistent facial pain syndromes due to ischemic lesions of trigeminal nerves in thrombosis of the arteries that supply these cranial nerves in patients with VZV-induced vasculopathies [19].

Therefore, the present analysis of the links between herpesvirus infections and trigeminal neuralgia should be based on the currently known spectrum of direct and indirect trigeminal nerve damage during reactivation of herpesviruses in immunosuppressed patients [22, 23]. Further studies devoted to the exploration of these associations would pave the way for an etiologically based clinical diagnostics and use of etiotropic antiviral therapy for refractory atypical neuralgia associated with herpesvirus infections or relapses after surgery. This would improve control over severe pain.

The purpose of this study is to diagnose herpesvirus infections in patients with refractory atypical trigeminal neuralgia with assessment of pathogenetic links and study of the efficacy of antiviral treatment.

The objectives of the study are formulated below:

To diagnose reactivated herpesvirus infection in patients with atypical refractory trigeminal neuralgia.

To explore ways in which reactivated herpesvirus infection can affect atypical refractory trigeminal neuralgia.

To assess the immune status of patients with atypical refractory trigeminal neuralgia associated with reactivated herpesvirus infection.

To test combination antiviral therapy with valaciclovir and recombinant alpha2b-interferon in patients with atypical refractory trigeminal neuralgia associated with reactivated herpesvirus infection.

Materials and methods

Study design

To achieve the study purpose, a prospective controlled non-randomized clinical trial was conducted during the period from 2012 to 2021. It involved 95 patients with idiopathic refractory atypical trigeminal neuralgia and was the result of cooperation between the Department of Subtentorial Neurooncology and the Department of Neurobiochemistry at the A.P. Romadanov Institute of Neurosurgery, Institute of Immunology and Allergology, and Institute of Experimental and Clinical Medicine at the O.O. Bogomolets National Medical University (Online Resource 1).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria included female patients, atypical nature of trigeminal neuralgia, severe or moderate pain, disease duration of more than 1 year, and resistance to the recommended drugs. The exclusion criteria were patient refusal to participate in the study, patient participation in other trials, odontogenic genesis of neuralgia, lack of compliance, development of side effects of tested drugs with their subsequent withdrawal, development of other diseases during the study, and receiving certain drugs for other indications.

Study endpoints

The endpoints of the study were the intensity of neuropathic pain according to the visual analog scale (VAS), viral load in blood leukocytes by PCR (excluding infections caused by HSV-1/2, VZV), and the dynamics of immunological parameters. In patients with HSV-1/2 and VZV infections, the virus status was monitored by serum specific IgM and IgA titers after 2 months of treatment and by serum specific IgG titers at 6 months from the therapy start.

Study limitations

The limitation of this clinical study was no randomization and placebo control. However, a sufficient number of participants, meticulous medical records, maximum standardization of medical procedures, and control points make it possible to consider the data as informative enough to formulate adequate conclusions for planning a randomized placebo-controlled study.

Patient characteristics

The age of patients ranged from 25 to 47 years (Table 1). The duration of neuralgia before participation in the study ranged from 2 to 16 years, with a mean duration of 5.2 ± 0.41 years. Women made up 100% of the study participants, as women are more likely to develop trigeminal neuralgia than men, and they are the target group for the refractory disease forms. All patients were monitored in the outpatient setting, but had regular contacts with the investigators. Social factors, such as income level or marital status, were not taken into account.

Table 1.

Age distribution of the EG patients (n = 95)

| Age, years | 25–30 | 31–35 | 36–40 | 41–47 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 21 | 28 | 24 | 32 |

Initially, patients from different regions of Ukraine were referred by neurologists and neurosurgeons to the pain treatment center, where the diagnosis of atypical refractory trigeminal neuralgia was established or confirmed based on the ICHD-2 and ICHD-3. Those who voluntarily consented to participate in the clinical trial were referred to the Department of Neurosurgery at the Institute of Neurosurgery for laboratory tests to identify herpesviruses. These participants were included in the observation group (n = 95). Subsequently, the patients were consulted and examined at the Institute of Immunology and Allergology and Institute of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, where they were assessed for immune status and prescribed tested combination antiviral therapy. Treatment was based on the presence of reactivated herpesvirus infection determined in blood leucocytes by PCR. After 1 and 2 months from the start of therapy, the patients undergone viral load and immune status assessments. There were 64 patients undergoing a full course of two-month therapy and follow-up (experimental group, n = 64). Other patients refused to receive treatment (control group 1, n = 31). The efficacy of the tested therapy was investigated in comparison with the natural course of the disease. Control group 2 consisted of 32 healthy patients of similar age and gender distribution.

Laboratory and instrumental study methods

Reactivated viral infection was diagnosed based on blood leukocytes by PCR with species-specific primers (HSV-1/2, VZV, EBV, CMV, HHV-6, HHV-7, HHV-8). Biocom reagents (Russian Federation) were used. Given the differences in the properties of pathogens and pathogenesis of the infections caused by them, serum concentrations of IgM, IgA, and IgG to HSV-1/2 and VZV were determined using solid-phase enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (VectorBest, Russian Federation).

Immunological examination included the measurement of general blood counts, subpopulation of lymphocytes using laser flow cytofluorimetry (Epics Xl cytofluorimeter, USA), and indirect immunofluorescence method with monoclonal antibodies to CD-markers with two or three markers (CD3 + , CD3 + CD4 + , CD3 + CD8 + , CD3–CD19 + , CD3–CD16 + CD56 + , CD3 + CD16 + CD56 +) (Beckman Coulter reagents, USA). Phagocytosis was assessed by latex test with determination of the phagocytic index, as well as by the activity of phagocyte myeloperoxidase (laser flow cytofluorimetry). Serum concentrations of the main classes of immunoglobulins (IgM, IgG, IgA, IgE, IgD) and subclasses of IgG (IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, IgG4) in blood serum were measured by ELISA (VectorBEST, Russian Federation).

The results of serological serum tests were evaluated for specific antineuronal autoantibodies to hippocampal autoantigens, which are validated as markers of autoimmune limbic encephalitis. In particular, these were autoantibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase (GADA), neuron potassium channels, amphiphizine, NMDA neuron receptors, GABA, CV2, Yo, Ri, Ma, Hu, AMPAR 1 and 2 (ELISA; MDI Limbach Berlin GmbH, Germany).

All patients underwent brain MRI focused on the roots of V cranial nerves with the program CISS3D or 3Ddrive. Neuroradiological signs of early demyelination were evaluated while diagnosing trigeminal neuralgia in patients with multiple sclerosis, as recommended by McDonald criteria.

Therapy under investigation

The tested combination antiviral therapy included valaciclovir per os at a dose of 3 g/day, divided into three doses of 1 g to be taken every 8 h, and recombinant human alpha2b-interferon at a dose of 3 million IU SC 1 time every 2 days in the evening for 2 months.

Scientific hypothesis

The researchers suggested that an array of laboratory tests and instrumental examinations of patients would demonstrate the incidence of reactivation of latent herpesviruses / immunosuppression-induced reactivation of herpesviruses in patients with refractory atypical trigeminal neuralgia. The heterogeneity of herpesvirus lesions, which could be involved in the development of trigeminal neuralgia, was evaluated for the nerves themselves and anatomical areas of the CNS functionally related to the trigeminal nerves, considering the direct mechanisms of trigeminal nerve damage, as well as indirect, autoimmune, immunoinflammatory, compression and neurodegenerative mechanisms of damage. The hypothesis was to be tested on the basis of the outcomes of antiviral treatment designed to reduce viral activity and pain intensity.

Statistical analysis methods

Methods of structural and comparative analysis were used for the statistical analysis of information. The Shapiro–Wilk test was applied to check the distribution of variants in the variation series. In order to confirm the significance of differences in the results, the Student’s T-test was used with the calculation of the confidence factor p (parametric criterion) and the number of Urbach Z signs (non-parametric criterion). The difference was considered significant at p < 0.05 and Z < Z0.05.

Sources of funding

The study was performed as a fragment of scientific work commissioned by the Ministry of Health of Ukraine, grant No. 0121U107940.

Ethics statement

The research complies with the guidelines for human studies and was conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The author declares that the work is written with due consideration of ethical standards. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles approved by the Human Experiments Ethics Committee of O'Bogomolets National Medical University (protocol No. 140, 21.12.2020). The written informed consent was obtained from participants.

Study results and their discussion

Refractory atypical trigeminal neuralgia was closely associated with reactivated herpesvirus infection, as the latter was detected in 83 (87%) subjects. Meanwhile, patients without trigeminal neuralgia in CG2 had only 7 (23%) cases of reactivated herpesvirus infection (p < 0.05; Z < Z0.05).

In general, the rates of infection in the EG were as follows: VZV—33%, HSV1/2—23%, EBV—26%, CMV—7%, HHV-6—25%, HHV-7—42%, HHV-8—2% of cases. Monoinfection occurred in 42%, and mixed infection was reported in 58% of cases (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The EG structure (n = 95) by the type of detected reactivated herpesvirus

The study analyzed the possible connective pathogenic links between the existing trigeminal neuralgia and reactivated herpesvirus infection in each patient. The researchers found that facial herpes zoster (zoster sine herpete) followed postherpetic neuralgia in 16 patients (17%). A typical exanthema is indicative of the clinical diagnosis of herpetic ganlioradiculoneuritis, although in 10–20% of cases reactivation of VZV from the trigeminal nerve gaseous node is not accompanied by rashes, and this fact can result in diagnostic errors [8]. Identification of salivary viral DNA, detection of blood specific IgM, IgA or a significant increase in the titer of serum specific IgG (paired serum method) allowed a correct differential diagnosis on the border between postherpetic neuralgia and idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia.

Salivary HSV1/2 DNA and blood specific IgM, IgA to HSV1/2 were detected in 22 (23%) cases, which, due to the lack of exa- and enanthema, were regarded as a manifestation of herpes sine herpete. Currently, there are a number of reports suggesting the possibility of development of trigeminal neuralgia in reactivated HSV1/2-infection of the orofacial localization [5, 6].

In 15 (16%) cases, temporomandibular pain was the cause of VZV-induced diffuse vasculopathy of small cerebral arteries (a term proposed by Nagel et al. [19]) with multiple lacunar infarcts in the subcortical areas of cerebral white matter at the sites of middle cerebral arteries supply. Zones of lacunar cerebral infarctions were detected by brain MRI in conventional modes (Fig. 2A). Specific serum IgM and IgA to VZV were noted. In half of the cases, lumbar puncture was performed and the phenomenon of intrathecal synthesis of specific IgG to VZV was revealed. In these cases, the ischemic nature of trigeminal neuralgia due to thrombosis of the feeding artery was assumed, as it is postulated in multiple mononeuritis of cranial nerves of VZV etiology [19].

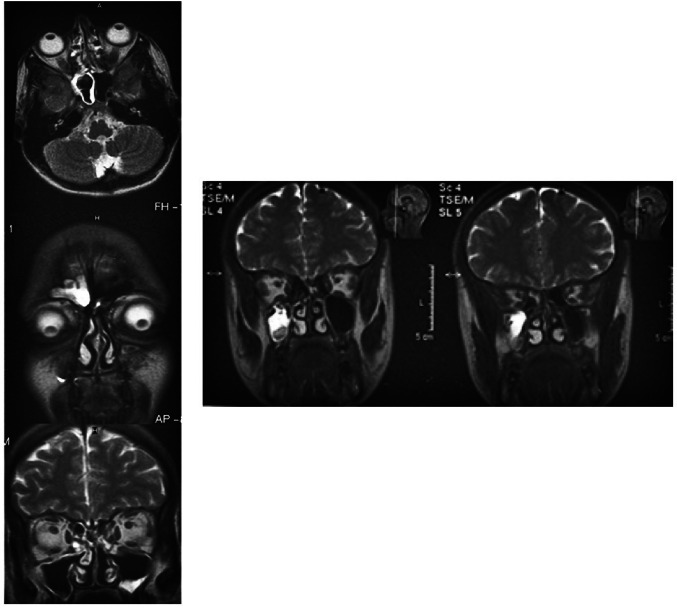

Fig. 2.

Neuroimaging and neurophysiological data of the EG patients Note: A—VZV-induced diffuse vasculopathy of small cerebral arteries (FLAIR mode, axial projection; multiple hyperintensive foci of lacunar infarction in the subcortical areas of cerebral white matter at the sites of middle cerebral arteries supply are visualized—1, 2, leukoareosis zone—3, ventriculomegaly—4, 5, focal atrophy area (shown in the square); B—bilateral hippocampus sclerosis as a manifestation of HHV-6-induced temporal median sclerosis (FLAIR mode, coronary projection; sclerosed hippocampi are marked by arrows); C—multiple sclerosis with clinically isolated syndrome in the form of refractory facial pain (FLAIR mode, axial projection; multiple foci of demyelination in the cerebral white matter in the form of small areas of hyperintense MR signal are visualized); D—HHV-7-induced autoimmune limbic encephalitis caused by autoantibodies to neuron potassium channels, with isolated refractory facial pain (FLAIR mode, axial projection; asymmetric hyperintensive MR signal from both hippocampi is visualized); E—EEG in autoimmune limbic encephalitis caused by autoantibodies to neuron potassium channels (epileptiform activity is marked by an oval)

In 25 (27%) cases, MRI showed temporal mesial sclerosis. Such patients were predominantly diagnosed with reactivated HHV-6 and HHV-7 infections. The authors found that HSV1/2 and HHV-6 may transolfactorially migrate from the nasal mucosa to the mesolimbic system of the cerebral temporal lobes (hippocampus, amygdala, islets, parahippocampal convolutions), inducing neurodegenerative damage in analogy with temporal mesial sclerosis (Fig. 2B). The results of a recent meta-analysis confirm the association between HHV-6 and temporal median sclerosis in humans [20]. A systematic review by Rusbridge indicates that the impairment of central pain regulation in the corticolimbic system of the CNS (prefronal cortex, hippocampus, amygdala) is one of the mechanisms of refractory pain syndromes [24]. Using MR tomographs with a magnetic induction value of 7 Tl, Alper et al. [25] showed a progressive decrease in the amygdala volume in patients with refractory trigeminal neuralgia. This phenomenon was typical of temporal median sclerosis in humans. Liu et al. [11] showed that a reduction in the activity of mitogen activated protein kinase systems (MAPK) associated with activation pathway helps to reduce the intensity of pain in trigeminal neuralgia. At the same time, Engdahl et al. [26] demonstrated that HHV-6 induces the development of temporal median sclerosis by abnormal hyperactivation of the MAPK-associated pathway to control inflammation and apoptosis in the CNS.

In 20 (21%) cases, relapsing-recurrent multiple sclerosis was diagnosed based on contrast-enhanced brain MRI. Demyelination was noted in the projection of the conduction pathways of the trigeminal nerve near its exit from the brainstem. Most of these patients had no manifestations of multiple sclerosis apart from neuropathic facial pain, despite the presence of multiple periventricular foci of demyelination on MR images (Fig. 2C), which led to establishing an incorrect diagnosis of idiopathic atypical trigeminal neuralgia. The results of recent meta-analyzes and systematic reviews confirm the association between multiple sclerosis and EBV [27] and HHV-6 infections [28]. In this subgroup, reactivated EBV, HHV-6, and HHV-7 infections were observed, which is consistent with the notion of the role of viral agents as triggers of multiple sclerosis. Li et al. [21] validated neuroradiological signs of early demyelination in T1-w/T2-w regimens to diagnose the initial manifestations of multiple sclerosis in patients with refractory neuropathic facial pain as an isolated clinical syndrome. A thorough systematic review of the problem of neuropathic pain in multiple sclerosis was prepared by Spirin et al. [29].

In 18 (19%) cases, there was autoimmune limbic encephalitis caused by autoantibodies to autoantigens of hippocampal neurons, including GADA, neuron potassium channels, amphiphizine, and CV2. In such cases, reactivated EBV, HHV-6, and HHV-7 infections predominated. Herpesviruses, like malignant neoplasms, are triggers of autoimmune limbic encephalitis in humans [30], which can lead to disruption of the central mechanisms of nociception and manifest itself as a phenomenon of refractory facial pain. Schwenkenbecher et al. [31] showed that intrathecal synthesis of specific IgG to EBV in autoimmune limbic encephalitis is observed in 19% of cases, while in multiple sclerosis—only in 7% of cases. In half of the cases of autoimmune encephalitis, conventional brain MRI measurements did not show the typical phenomenon of hyperintensity of the hippocampus signal in T2-weighted and FLAIR modes (Fig. 2D), indicating so-called autoimmune limbic encephalitis with a normal MR picture (the term was proposed by Guasp et al. [1]), although clinical, serological and neurophysiological data (Fig. 2E) indicated this diagnosis. Therefore, patients were misdiagnosed with trigeminal neuralgia based on refractory facial pain.

In most of the EG patients there were neuroradiological signs of deviation, deformation of the trigeminal root on the side of pain syndrome in the paramolar tank, although MR signs of vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve were visualized in only 16 (17%) cases, with no clinical picture of typical neuralgia observed. Neurosurgical intervention revealed the signs of chronic inflammation and adhesions in the area of neurovascular conflict, which allowed assuming that reactivated herpesvirus infection was the cause of inflammation, which deepened the pre-existing conflict between the blood vessel and nerve (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative photographs of neurovascular conflict complicated by the inflammatory adhesion process in the area of the trigeminal nerve root Note: (on the left—before surgery, on the right—after neurolysis, decompression); TN—trigeminal nerve; AS—arachnoid spikes; VPS—veins of the upper petrosal sinus; Pons—bridge; H—hook (tool)

In 12 (13%) cases, pain in the projection of the second branch of the trigeminal nerve was associated with productive polysinusitis with the formation of granulomas, pseudopolyps and cysts (Fig. 4). The trigeminal nerve is most likely involved secondarily due to the spread of the inflammatory process. Some patients had a history of atypical neuralgia with episodes of acute piercing pain with rhinorrhea, presumably associated with spontaneous rupture of cysts. Such lesions are often an accidental finding during brain MRI for other reasons. In these cases, mostly isolated IgE deficiency and phagocyte myeloperoxidase deficiency were diagnosed, and cases of induction of foci of cold inflammation in additional sinuses were described [32, 33]. Accordingly, Gujadhur et al. [34] reported CMV-induced hyperplastic sinusitis in a HIV-negative allogeneic kidney recipient.

Fig. 4.

MR-picture of productive hyperplastic pansinusitis in patients with myeloperoxidase deficiency of phagocytes who suffered from refractory facial pain (FLAIR mode, axial and coronary projections, hyperintensive MR signal demonstrated from the maxillary, sphenoidal, and frontal sinuses)

There were 7 (8%) patients with neuropathic pain in the innervation zone of the third branch of the trigeminal nerve who were diagnosed with cervicogenic cranialgia, which mimicked trigeminal neuralgia due to irradiation of pain along communications between the cervical spinal cord and trigeminal nerves [14]. The problem of cervicogenic cervicalgia as a cause of misdiagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia is reviewed in a systematic review by Bogduk and Gavind [35]. Mitrofanova et al. [36] discussed the cases of intervertebral discitis of HSV-1 and HSV-2 etiology, but it is also known that infection reduces the nociceptive threshold due to an inflammatory response, which may have played a role in inducing facial pain.

After neuroimaging, there were 6 (6%) cases of cavernous sinus thrombosis detected, which is considered to be the cause of neuralgic pain [37, 38]. Pain was reported in the area of innervation of the first branch of the trigeminal nerve, which topically corresponded to thrombosis [39, 40]. Brain venous sinus thrombosis was described as a complication of reactivated herpesvirus infection. Chan et al. [18] diagnosed lateral venous sinus thrombosis in patients with zoster sine herpete. Pazos-Añón et al. [35] found venous cerebral thrombosis in an HIV-infected patient with Ramsay Hunt syndrome.

Another 5 patients (5%) had cervical meningoradiculitis of HHV-7 etiology, as indicated by the accumulation of gadolinium seen on MR images in T1-weighted mode. Miranda et al. [41] reported the development of meningomyelitis upon reactivation of HHV-7 with neuropathic pain. This is due to the migration of pain from the cervical nerves to the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve.

In 3 (3%) cases, facial pain was associated with granuloma in the area of the trigeminal nerve root of VZV etiology (Online Resource 2). Herpesviruses can cause granulomatous process – pseudotumors [4]. Trigeminal neuralgia may be a manifestation of pontine tumors, in connection with which the differential diagnostics was performed using MRI with contrast and MR spectroscopy [42].

The combined antiviral treatment resulted in a decrease in the intensity of facial neuropathic pain in 41 (43%) subjects in the EG and none subjects in the KG1 (p < 0.05; Z < Z0.05). Elimination of algae was achieved in 17 (18%) subjects in the EG and none subjects in the KG1 (p < 0.05; Z < Z0.05). In general, a positive effect was achieved in 58 (61%) cases (Online Resource 3). The beneficial effect of therapy developed during the first month of treatment and intensified in the second month. In most individuals with a positive response, the duration of neuralgia did not exceed 5 years. However, there were 37 (39%) cases in the EG where antiviral treatment did not affect the pain syndrome. In almost half of the cases of resistance there was a positive phenomenon of restoring sensitivity to drugs for neuropathic pain.

In general, reactivated herpesvirus infection was eliminated in the EG in 77% of cases. The effectiveness of treatment was higher than the achieved effect on the pain syndrome. The best results were obtained for VZV infection (72%; p < 0.05; Z < Z0.05). Slightly worse results were reported for infections caused by lymphotropic herpesviruses (57%; p < 0.05; Z < Z0.05). This is associated with varying sensitivity to valacyclovir and recombinant alpha2b-interferon in herpesviruses of different subfamilies (Online Resource 4). Elimination of VZV was more strongly correlated with a positive pain response as compared to the subgroup of patients with lymphotropic herpesviruses. There were no adverse reactions registered, except for short-term flu-like syndrome (53% of cases). Gilden et al. [5] described chronic ganglionitis caused by VZV in a patient with persistent neuropathic pain. Complete pain relief occurred 5 times in a row after a course of famciclovir, but pain returned a week after drug discontinuation [5]. Merigan et al. [43] demonstrated the efficacy of leukocyte alpha-interferon in herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Based on the assessment of immune status, minor immunodeficiencies were diagnosed in 81 EG patients (85%), including IgE, IgG1, IgA, IgM, myeloperoxidase, natural killer (NK), natural killer T cells (NKT) deficiencies, and idiopathic CD4 + T-cell lymphopenia. The rate of these events was significantly higher than in the CG2 where 8 (26%) cases were registered (p < 0.05; Z < Z0.05) (Online Resource 5). Normal immune status of the EG patients was diagnosed only in 14 (15%) cases.

Immune dysfunction could be the cause of reactivation of herpesviruses. Severe herpesvirus infections were reported in patients with NK [44], NKT [45], CD16 [46], IgG1 [47], IgE [48] deficiencies, and idiopathic CD4 + T-cell lymphopenia [49].

The importance of diagnosing immune dysfunctions is evidenced by the associations between the form of immunodeficiency, the type of virus and the factors causing nerve damage. In case of VZV, mostly cellular immune disorders were registered, in particular, NK, NKT, and CD16 deficiencies (two thirds of cases). These data are consistent with clinical reports of immune disorders in recurrent alpha-herpesvirus infections. The study conducted by Backström et al. [50] is of value, which confirmed the involvement of NK nerve ganglia in the control of latent VZV. NK produces type I interferons in case of an attempt of virus reactivation and has a virostatic effect. In patients with lymphotropic herpesvirus infections, disorders of humoral immunity and phagocytosis prevailed. They were more common than in the reactivation of alpha-herpesviruses (63.6% vs. 29.1% of cases; p < 0.05; Z < Z0.05).

There was a large proportion of IgE deficiencies in the EG group (30% of cases). In the general population, the proportion of IgE deficiencies was 3% [34], and in patients with immune-dependent pathology, the proportion equaled to 12% [35]. That is, the proportion of IgE deficiencies in patients with trigeminal neuralgia is 10 times higher among the general population and three times higher than in immune-dependent pathology. IgE is involved in the mechanisms of local immunity, which may explain the reactivated state of herpesviruses by weakening immune surveillance in the biological reservoir. IgE deficiency contributes to foci of cold inflammation, which was observed in some EG patients [35]. In a population-based study involving 18,487 people, Magen E. established the association between selective IgE deficiency, bronchial asthma and bronchial hyperreactivity in children, chronic sinusitis, otitis media, autoimmune and oncological lesions in adults [34].

Conclusions

The results of the study show the association between atypical refractory trigeminal neuralgia and reactivated herpesvirus infections. Heterogeneity of the origin of the pain syndrome is revealed. This phenotype was the result of direct or indirect effects of reactivated human herpesvirus infections on the peripheral structures of the trigeminal nerves and centers of pain regulation in the CNS. The phenotype of refractory atypical trigeminal neuralgia is most often associated with reactivated VZV and HHV-7 infections, less often with other herpesviruses. Involvement of trigeminal nerves was due to both direct (zoster sine herpete, herpes sine herpete, ganglionitis, neuritis) and indirect effects of the virus due to CNS damage (VZV-vasculopathy, HHV-7-meningomyelitis), compression (pseudotumors, cavernous sinus thrombosis, sinusitis), autoimmune reactions (multiple sclerosis, autoimmune limbic encephalitis), virus-induced disorders of central pain regulation (temporal median sclerosis), induction of inflammation with a probable decrease in the threshold of nociception (cervicogenic cephalgia), complicated neurovascular conflict. Minor immunodeficiencies related to cellular innate and humoral adaptive immunity were noted; the association with isolated IgE, NK and NKT cell deficiencies was particularly close.

Combination antiviral therapy, including valaciclovir and recombinant alpha2b-interferon, is effective for herpesvirus infection (77%), moderately effective in reducing pain intensity (61%), and ineffective in correcting immune disorders (26% of cases). The highest efficacy of treatment was registered in the subgroup of patients with postherpetic neuralgia after zoster sine herpete and herpes sine herpete. Thus, it is the main target cohort for receiving antiviral therapy.

There is a need to conduct further studies involving placebo control and randomization. These studies should enroll more participants.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by DM. The first draft of the manuscript was written by VF. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was performed as a fragment of scientific work commissioned by the Ministry of Health of Ukraine, grant No. 0121U107940.

Data availability

Data will be available on request.

Declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval

The research complies with the guidelines for human studies and was conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The author declares that the work is written with due consideration of ethical standards. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles approved by the Human Experiments Ethics Committee of O'Bogomolets National Medical University (protocol No. 140, 21.12.2020).

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Informed consent

The written informed consent was obtained from participants.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Guasp M, Landa J, Martinez-Hernandez E, Sabater L, Iizuka T, Simabukuro M, et al. Thymoma and autoimmune encephalitis: clinical manifestations and antibodies. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2021;8(5):e1053. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000001053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Handa S, Keith DA, Abou-Ezzi J, Rosèn A, et al. Neuropathic orofacial pain Characterization of different patient groups using the ICOP first edition, in a tertiary level Orofacial Pain Clinic. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2021;132(6):653–61. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2021.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singhal S, Danks RA. Radiological and neurosurgical diagnosis of arterial neurovascular conflict on MRI for trigeminal neuralgia. World Neurosurg. 2021;157:e166–e172. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.09.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adachi M. A case of Varicella zoster virus polyneuropathy: involvement of the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves mimicking a tumor. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29(9):1743–1745. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilden DH, Cohrs RJ, Hayward AR, Wellish M, Mahalingam R. Chronic varicella-zoster virus ganglionitis—a possible cause of postherpetic neuralgia. J Neurovirol. 2003;9(3):404–407. doi: 10.1080/13550280390201722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krohel GB, Richardson JR, Farrell DF. Herpes simplex neuropathy. Neurology. 1976;26(6 PT 1):596–597. doi: 10.1212/wnl.26.6.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fedirko V. On pathogenesis of Cranial nerves hyperactive dysfunction syndrome. 13th European Congress of Neurosurgery, Glasgow (UK), September 2–7, 2007: 655–9.

- 8.Peñarrocha M, Bagán JV, Alfaro A, Peñarrocha M. Acyclovir treatment in 2 patients with benign trigeminal sensory neuropathy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59(4):453–456. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.21887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou J, Li J, Ma L, Cao S. Zoster sine herpete: a review. Korean J Pain. 2020;33(3):208–215. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2020.33.3.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramos F, Monforte C, Luengo A. Acute sensory neuropathy associated with a varicella-zoster infection. Rev Neurol. 1999;28(11):1067–1069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu W, Pu B, Liu M, Zhang X, Zeng R. Down-regulation of MAPK pathway alleviates TRPV4-mediated trigeminal neuralgia by inhibiting the activation of histone acetylation. Exp Brain Res. 2021;239(11):3397–3404. doi: 10.1007/s00221-021-06194-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stalker WH. Facial neuralgia associated with recurrent herpes simplex. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1980;49(6):502–503. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(80)90071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roullet E, Assuerus V, Gozlan J, Ropert A, Saïd G, Baudrimont M, et al. Cytomegalovirus multifocal neuropathy in AIDS: analysis of 15 consecutive cases. Neurology. 1994;44(11):2174–2182. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.11.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farahani RM, Marsee DK, Baden LR, Woo SB, Treister NS. Trigeminal trophic syndrome with features of oral CMV disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106(3):e15–e18. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hüfner K, Arbusow V, Himmelein S, Derfuss T, Sinicina I, Strupp M, et al. The prevalence of human herpesvirus 6 in human sensory ganglia and its co-occurrence with alpha-herpesviruses. J Neurovirol. 2007;13(5):462–467. doi: 10.1080/13550280701447059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ptaszyńska-Sarosiek I, Dunaj J, Zajkowska A, Niemcunowicz-Janica A, Król M, Pancewicz S, et al. Post-mortem detection of six human herpesviruses (HSV-1, HSV-2, VZV, EBV, CMV, HHV-6) in trigeminal and facial nerve ganglia by PCR. PeerJ. 2019;6:e6095. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neroyev VV, Saakian SV, Miakoshina EB, Iurovskaia NN, Riabina MV, Zaĭtseva OV, Lysenko VS. Differential diagnosis of early central choroidal melanoma and late stage age-related macula degeneration. Vestn oftalmol. 2013;129(1):39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan J, Bergstrom RT, Lanza DC, Oas JG. Lateral sinus thrombosis associated with zoster sine herpete. Am J Otolaryngol. 2004;25(5):357–360. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagel MA, Niemeyer CS, Bubak AN. Central nervous system infections produced by varicella zoster virus. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2020;33(3):273–278. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wipfler P, Dunn N, Beiki O, et al. The viral hypothesis of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy—is human herpes virus-6 the missing link? A systematic review and meta-analysis Seizure. 2018;54:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2017.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li CMF, Chu PPW, Hung PS, Mikulis D, Hodaie M. Standardizing T1-w/T2-w ratio images in trigeminal neuralgia to estimate the degree of demyelination in vivo. Neuroimage Clin. 2021;32:102798. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2021.102798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saakyan SV, Zharua AA, Myakoshina EB, Lazareva LA, Yakovlev SB. Superselective intra-arterial chemotherapy treatment for resistant and severe retinoblastoma. Russ Pediatr Ophthalmol. 2013;1:31–4. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saakyan SV, Myakoshina EB, Yurovskaya NN. Tumor-associated distant maculopathy caused by small uveal melanoma. Russ Ophthalmol J. 2011;4(2):41–45. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rusbridge C. Neurobehavioral disorders: the corticolimbic system in health and disease. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2020;50(5):1157–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alper J, Seifert AC, Verma G, Huang KH, Jacob Y, Al Qadi A, et al. Leveraging high-resolution 7-tesla MRI to derive quantitative metrics for the trigeminal nerve and subnuclei of limbic structures in trigeminal neuralgia. J Headache Pain. 2021;22(1):112. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01325-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engdahl E, Niehusmann P, Fogdell-Hahn A. The effect of human herpesvirus 6B infection on the MAPK pathway. Virus Res. 2018;256:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2018.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobs BM, Giovannoni G, Cuzick J, Dobson R. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between Epstein-Barr virus, multiple sclerosis and other risk factors. Mult Scler. 2020;26(11):1281–1297. doi: 10.1177/1352458520907901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pormohammad A, Azimi T, Falah F, Faghihloo E. Relationship of human herpes virus 6 and multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(4):2850–2862. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spirin NN, Kiselev DV, Karpova MS. Neuropathic pain syndromes in patients with multiple sclerosis. Zh nevrol psikhiatr im SS Korsakova. 2021;121(7):22–30. doi: 10.17116/jnevro202112107222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venâncio P, Brito MJ, Pereira G, Vieira JP. Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis with positive serum antithyroid antibodies, IgM antibodies against mycoplasma pneumoniae and human herpesvirus 7 PCR in the CSF. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(8):882–883. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwenkenbecher P, Skripuletz T, Lange P, Dürr M, Konen FF, Möhn N, et al. Intrathecal antibody production against epstein-barr, herpes simplex, and other neurotropic viruses in autoimmune encephalitis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2021;8(6):e1062. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000001062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magen E, Schlesinger M, David M, Ben-Zion I, Vardy D. Selective IgE deficiency, immune dysregulation, and autoimmunity. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2014;35(2):e27–33. doi: 10.2500/aap.2014.35.3734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith JK, Krishnaswamy GH, Dykes R, Reynolds S, Berk SL. Clinical manifestations of IgE hypogammaglobulinemia. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1997;78(3):313–318. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gujadhur A, Thomson N, Aung AK, Catriona M, Solomon M. CMV sinusitis in a HIV-negative renal transplant recipient. Transplantation. 2014;97(9):e55–e57. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bogduk N, Gavind J. Cervicogenic headache: an assessment of the evidence on clinical diagnosis, invasive tests, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(10):959–968. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70209-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitrofanova LB, Mitrofanov NA, Shliakhto EV, Koval'skiĭ GB. Spinal osteochondrosis, mesenchymal dysplasia and herpes infection. Arkh Patol. 2006;68(6):23–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vurdelja RB, Budincević H, Prvan MP. Central poststroke pain. Lijec Vjesn. 2008;130(7–8):191–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pazos-Añón R, Machado-Costa C, Farto E, Abreu J. Ramsay-Hunt syndrome complicated with cerebral venous thrombosis in an HIV-1-infected patient. Enferm Infec Microbiol Clin. 2007;25(1):69–70. doi: 10.1016/s0213-005x(07)74232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farooqi AA, Gulnara K, Mukhanbetzhanovna AA, Datkhayev U, Kussainov AZ, Adylova A. Regulation of RUNX proteins by long non-coding RNAs and circular RNAs in different cancers. Noncoding RNA Res. 2021;6(2):100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ncrna.2021.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Egoshin VL, Ivanov SV, Savvina NV, Kapanova GZ, Grjibovski AM. Basic principles of biomedical data analysis in R. Ekologiya cheloveka (Human Ecol) 2018;7:55–64. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miranda CM, Torres TJP, Larrañaga LC, Acuña LG. Meningomyelitis associated with infection by human herpes virus 7: report of two cases. Rev Med Chil. 2011;139(12):1588–1591. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872011001200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galin P, Galyaveeva A, Bataev H, Safonov V. The role of micronutrients and vitamins in the prevention and remote treatment of heart failure. Rev Latinoam de Hipertens. 2020;15(1):26–32. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Merigan TC, Gallagher JG, Pollard RB, Arvin AM. Short-course human leukocyte interferon in treatment of herpes zoster in patients with cancer. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981;19(1):193–195. doi: 10.1128/AAC.19.1.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Biron CA, Byron KS, Sullivan JL. Severe herpesvirus infections in an adolescent without natural killer cells. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(26):1731–1735. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198906293202605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banovic T, Yanilla M, Simmons R, Robertson I, Schroder WA, Raffelt NC, et al. Disseminated varicella infection caused by varicella vaccine strain in a child with low invariant natural killer T cells and diminished CD1d expression. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(12):1893–1901. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Almerigogna F, Fassio F, Giudizi MG, Biagiotti R, Manuelli C, Chiappini E, et al. Natural killer cell deficiencies in a consecutive series of children with herpetic encephalitis. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2011;24(1):231–238. doi: 10.1177/039463201102400128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kallio-Laine K, Seppänen M, Aittoniemi J, Kautiainen H, Seppälä I, Valtonen V, et al. HLA-DRB1*01 allele and low plasma immunoglobulin G1 concentration may predispose to herpes-associated recurrent lymphocytic meningitis. Hum Immunol. 2010;71(2):179–181. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Picado C, de Landazuri IO, Vlagea A, Bobolea I, Arismendi E, Amaro R. Spectrum of disease manifestations in patients with selective immunoglobulin E deficiency. J Clin Med. 2021;10(18):4160. doi: 10.3390/jcm10184160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoshikawa T, Ihira M, Asano Y, et al. Fatal adult case of severe lymphocytopenia associated with reactivation of human herpesvirus 6. J Med Virol. 2002;66(1):82–85. doi: 10.1002/jmv.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Backström E, Chambers BJ, Ho EL, Naidenko OV, Mariotti R, Fremont DH, et al. Natural killer cell-mediated lysis of dorsal root ganglia neurons via RAE1/NKG2D interactions. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33(1):92–100. doi: 10.1002/immu.200390012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available on request.