Abstract

The genomes of many filamentous fungi, such as Aspergillus spp., include diverse biosynthetic gene clusters of unknown function. We previously showed that low copper levels upregulate a gene cluster that includes crmA, encoding a putative isocyanide synthase. Here we show, using untargeted comparative metabolomics, that CrmA generates a valine-derived isocyanide that contributes to two distinct biosynthetic pathways under copper-limiting conditions. Reaction of the isocyanide with an ergot alkaloid precursor results in carbon-carbon bond formation analogous to Strecker amino-acid synthesis, producing a group of alkaloids we term fumivalines. In addition, valine isocyanide contributes to biosynthesis of a family of acylated sugar alcohols, the fumicicolins, which are related to brassicicolin A, a known isocyanide from Alternaria brassicicola. CrmA homologs are found in a wide range of pathogenic and non-pathogenic fungi, some of which produce fumicicolin and fumivaline. Extracts from A. fumigatus wild type (but not crmA-deleted strains), grown under copper starvation, inhibit growth of diverse bacteria and fungi, and synthetic valine isocyanide shows antibacterial activity. CrmA thus contributes to two biosynthetic pathways downstream of trace-metal sensing.

Subject terms: Metabolomics, Fungal ecology, Biosynthesis, Antimicrobials

The genomes of filamentous fungi, such as Aspergillus, include many biosynthetic gene clusters of unknown function. Here, the authors show that copper starvation induces expression of an enzyme that generates a valine-derived isocyanide participating in two different pathways, for biosynthesis of acylated sugar alcohols and modified ergot alkaloids.

Introduction

The Kingdom Fungi produces an enigmatic diversity of secondary metabolites derived from dedicated biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) that encode the enzymes required to convert common primary metabolic building blocks into secondary metabolites. Genomic sequencing of 1000 s of fungi has revealed a vast space of BGCs with as yet undetermined function; however, their distribution among taxa is uneven: whereas yeasts contain few, if any, BGCs, some filamentous fungi such as Aspergillus spp. may have upwards of 70 BGCs/genome1. This tremendous expansion of BGCs in specific taxa remains an evolutionary enigma. Experimental evidence for functional roles of a few secondary metabolites (such as polyketide pigment protection of fungal spores from UV light2 or antibacterial properties of fungal secondary metabolites induced in fungal/bacterial culture2) supports the hypothesis that BGC-encoded metabolites are produced to address specific environmental constraints or challenges.

We became intrigued with the potential of fungal BGCs evolved to fit specific environmental niches upon our discovery of a new family of secondary metabolite biosynthetic enzymes, the isocyanide synthases (ICSs), in the filamentous pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus3. Curiously we found that one ICS-BGC was regulated by MacA (also called Mac1), a copper fist transcription factor that functions to activate copper importers during copper starvation4. This BGC, termed the crm (copper responsive metabolite) BGC, was activated in defined media lacking the essential trace element copper in a MacA-dependent manner3. Copper homeostasis is carefully controlled in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, as many biological processes require copper ions, yet too much copper is toxic.

Because loss of MacA and/or its importers greatly impair A. fumigatus growth in copper-limited conditions4,5, we wondered if the crm BGC was involved in fungal biology under low copper environments. We found that, under copper starvation conditions, CrmA converts l-valine to (S)−2-isocyanoisovaleric acid, which is then used for two different biosynthetic pathways. The isocyanide, in an unusual chemical reaction, attaches to chanoclavine-1 aldehyde (an ergot alkaloid biosynthesis intermediate)6,7 to form a new family of alkaloid peptides named the fumivalines. The formation of the fumivalines involves a carbon-carbon bond-forming reaction that is analogous to a well-known synthetic reaction, the Strecker amino acid synthesis. Penicillium spp., which contains a homolog of the crm BGC as well as an intact ergot alkaloid pathway, also produce fumivaline, which is, as in A. fumigatus, induced by copper starvation. Alternatively, the valine-derived isocyanoisovaleric acid is employed for the synthesis of acylated d-mannitol derivatives that represent plausible intermediates toward the biosynthesis of brassicicolin A, an isocyanide previously identified from Alternaria brassicicola8. Another ascomycete, Cochliobolus heterostrophus, whose genome includes a crmA homolog but lacks the ergot alkaloid pathway, produces related acylated d-mannitol derivatives under copper starvation conditions, but lacks the fumivalines.

Here we show that A. fumigatus employs an ICS to produce a reactive building block that is then integrated into two different secondary metabolite families via distinct chemical reactions, one of which provides the first example for Strecker-like amino acid biosynthesis in eukaryotes9. Copper starvation dependence of the identified metabolites and their antibacterial effects suggests that CrmA-dependent pathways provide fungi with niche-specific weaponry to increase fitness under environmental stress.

Results

CrmA encodes a multidomain ICS-NRPS-like enzyme

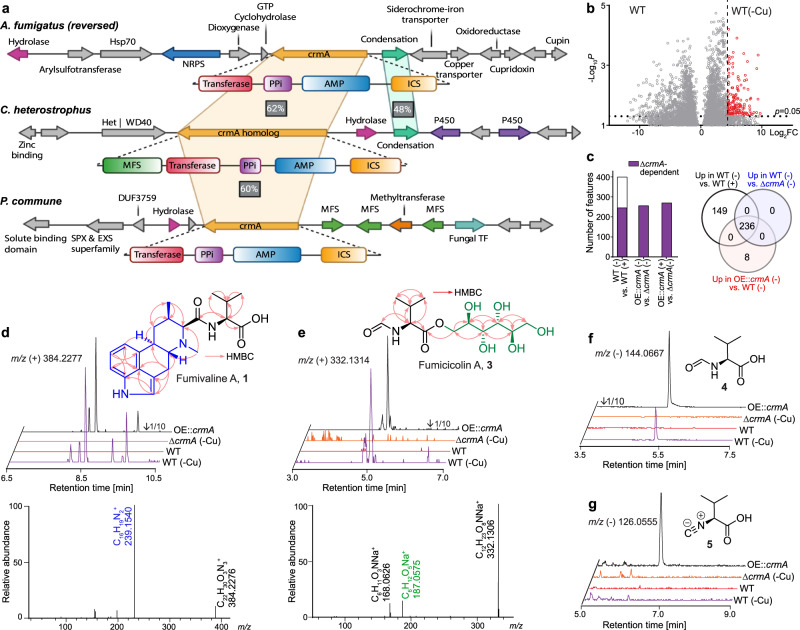

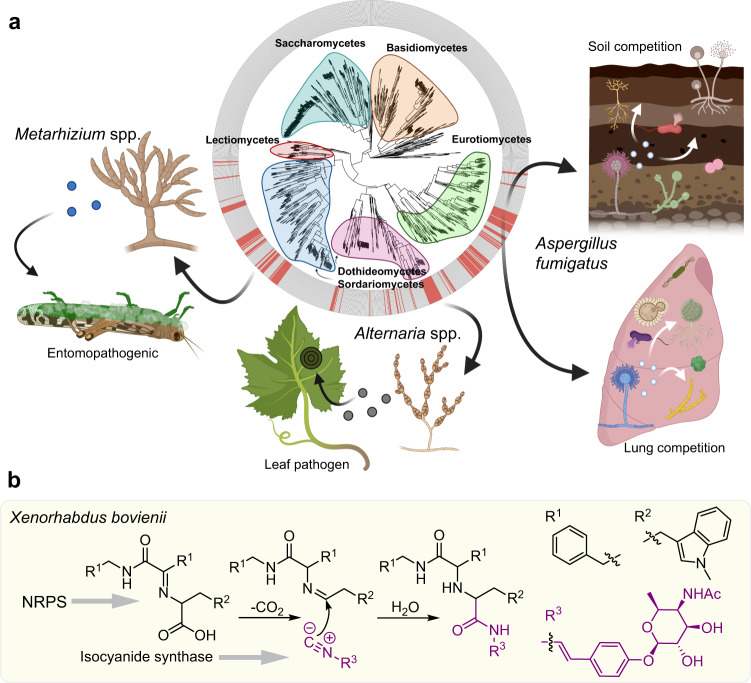

Comparative analyses of available fungal genomes revealed the multidomain ICS-NRPS-like gene crmA encoding adenylation, thiolation, and transferase domains, in addition to the isocyanide synthase domain (Fig. 1a)3. CrmA homologs are present primarily in three diverse ascomycete classes: Eurotiomycetes (e.g., Aspergillus, Penicillium, Talaromyces, Trichophyton spp.), Dothideomycetes (e.g., Cochliobolus, Leptosphaeria, Alternaria spp.) and Sordariomycetes (e.g., Verticillium, Metarhizium, Fusarium, Cordyceps, Beauveria, Trichoderma spp.) with the majority of genera consisting of pathogenic fungi. Variations in domain structure include the addition of a transporter domain found primarily in the Dothideomycetes, a clade that contains common leaf blight/spot fungal pathogens (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1, and Supplementary Data 1). In A. fumigatus, CrmA is part of the four-gene Crm cluster which additionally includes a predicted alcohol-O-acetyl transferase (crmB), siderochrome-iron transporter (crmC), and CtrA1 copper transporter (crmD), all of which are co-regulated by copper (Fig. 1a)3. To our surprise, we found little conservation crmB, C, and D in more distantly related species.

Fig. 1. The crm BGC and associated metabolites from A. fumigatus.

a Comparison of crm BGCs in A. fumigatus, P. commune, and C. heterostrophus. Homologous genes are marked with colors based on their corresponding functions. b Volcano plot of differential metabolites in wild type upregulated by copper starvation (red dots represent metabolites 20-fold upregulated at p < 0.05 as calculated by unpaired two-sided t-test, unadjusted for the number of comparisons, based on 6 independent replicates). c Total number of crmA-dependent metabolites in wildtype upregulated by copper starvation or crmA overexpression compared to the crmA deletion mutant and Venn diagram showing overlap of metabolites induced in WT A. fumigatus under copper-limited relative to copper-replete conditions, metabolites abolished in crmA deletion mutants, and metabolites induced in crmA overexpression mutants relative to WT grown under copper-limited conditions. d, e Structures, MS2 spectra, ESI + ion chromatograms, and HMBC correlations of fumivaline A (1) and fumicicolin A (3). Part of the structure highlighted in blue represents festuclavine (2). f, g Structures and ESI- ion chromatograms for N-formylvaline (4) and (S)−2-isocyanoisovaleric acid (valine isocyanide, 5). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Identification of crm cluster-derived metabolites

To identify crm-derived metabolites, we started by comparing the metabolomes of wildtype (WT) A. fumigatus and a ΔcrmA deletion mutant grown under copper-limited and copper-replete conditions, given that crmA expression is strongly copper-dependent3. Metabolite extracts were analyzed by high-resolution HPLC-MS (HPLC-HRMS), and the resulting datasets were compared using the Metaboseek software platform10, which facilitates comparative analysis of HPLC-HRMS data from multiple different conditions. These comparative analyses revealed a large number of MS features upregulated under low copper conditions. For example, we detected 385 features that were 20-fold or more upregulated under copper-limited conditions (p < 0.05) among a total of 30,000 detected features from both positive and negative ionization modes (Fig. 1b, see Methods for details on data processing). Production of 236 features induced under copper-limited conditions, representing ~30 distinct metabolites, was abolished in the ΔcrmA mutant, and in fact all features abolished in the ΔcrmA mutant were also copper-dependent (Fig. 1c). Next, we examined the metabolome of a crmA overexpression mutant (OE::crmA) under copper-limited and copper-replete conditions. Production of most metabolites abolished in the ΔcrmA mutant was increased above wild-type levels in OE::crmA regardless of a copper regime (Fig. 1c), further supporting that they represent CrmA-derived metabolites. Interestingly, none of the crmA-dependent features were affected by the deletion of any of the other cluster genes, crmB-D (Supplementary Data 2).

The crmA- and copper-dependent MS features were further characterized via tandem MS (MS2) and MS2 networking, which revealed several families of structurally related crmA-dependent metabolites. We then selected the most abundant family members for partial purification via reversed-phase preparative HPLC for NMR spectroscopic analysis (Fig. 1d–g, Supplementary Fig. 2a–e, see Supplementary Information for NMR data). This analysis revealed two distinct families of metabolites, both of which integrate an N-formylvaline moiety. Fumivaline A (1) (Fig. 1d) and the hydroxylated derivative fumivaline B (Supplementary Fig. 2a) represent modified ergot alkaloids featuring a festuclavine (2)-like ring system, whereas fumicicolin A (3) (Fig. 1e) and fumicicolin B (Supplementary Fig. 2b) represent esters of N-formylvaline with D-mannitol or a hexose, respectively. In addition, we detected free N-formylvaline (4) (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 2c), as well as small amounts of (S)−2-isocyanoisovaleric acid (5) (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 2d, e), a plausible precursor of the identified N-formylvaline derivatives (Supplementary Table 1). The identities of fumicicolin A (3) and (S)−2-isocyanoisovaleric acid (valine isocyanide, 5) were further confirmed using synthetic standards prepared from commercially available N-formylvaline (Supplementary Fig. 2f). Detailed descriptions of the syntheses are provided in the Supplementary Information. The (S)-configuration of the α-carbon in the valine-like moieties in fumivaline A and N-formylvaline was established using Marfey’s method11 (Supplementary Fig. 2g, h), suggesting that the crmA-derived metabolites are derived from l-valine. Lastly, we showed that the relative configuration of fumivaline A is identical to that of the related ergot alkaloid festuclavine (2) using NOESY spectra (Supplementary Fig. 2i)7,12.

Fumivaline biosynthesis requires the ergot alkaloid BGC

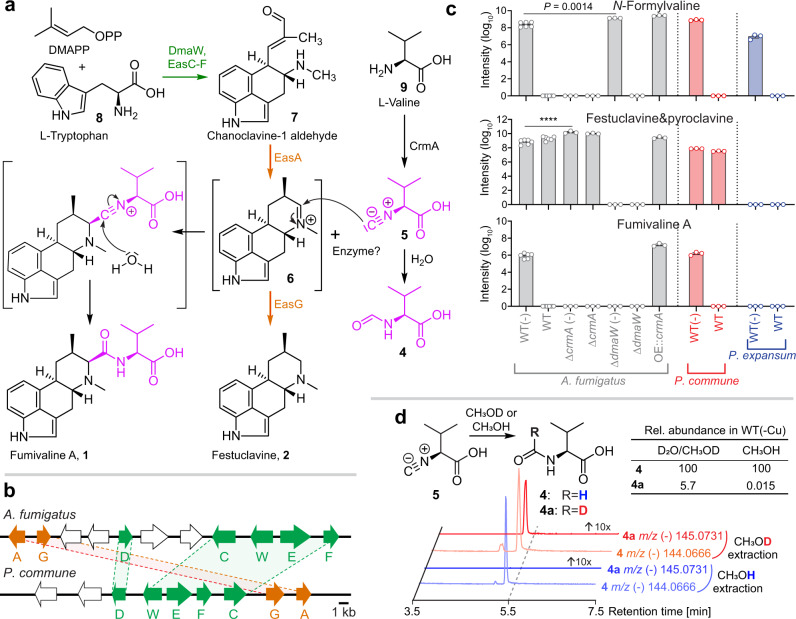

Ergot alkaloids are a class of tryptophan-derived alkaloids featuring the characteristic ergoline tetracyclic ring structure (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 3a)12,13. Given that the structures of the fumivalines are related to that of the ergot alkaloid festuclavine, it appeared that crmA worked in conjunction with the ergot alkaloid BGC for fumivaline biosynthesis. To confirm the requirement of the ergot alkaloid BGC in the biosynthesis of fumivalines, we examined the metabolome of a deletion mutant of DmaW, a rate-limiting enzyme involved in the condensation reaction of tryptophan and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) in ergot alkaloid BGCs7,14,15, in A. fumigatus (Fig. 2a, b). Deletion of dmaW eliminated the production of fumivalines A and B as well as of festuclavine and pyroclavine, whereas the abundance of other crmA-derived metabolites, including N-formylvaline remained unchanged or increased (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 3b). In turn, deletion of crmA eliminated N-formylvaline, fumivalines A and B synthesis but slightly increased the production of festuclavine and pyroclavine (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 3b). These data confirm that both crmA and the ergot alkaloid BGC are required for the production of the fumivalines.

Fig. 2. Comparison of fumivaline BGCs and ergot alkaloids production.

a Ergot alkaloid biosynthesis pathways in A. fumigatus and P. commune. l-Tryptophan (8) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate are converted into chanoclavine-1 aldehyde (7) by DmaW and EasC-F, which is then converted into festuclavine (2) by EasA and EasG in A. fumigatus and P. commune. Valine (9) is converted into valine isocyanide (5) by CrmA, which then reacts with the imine intermediate of festuclavine (6), resulting in formation of the amide bond in fumivaline A following hydration. In addition, hydration of valine isocyanide (5) produces N-formylvaline (4). b Comparison of crm BGCs of A. fumigatus and P. commune. Homologous genes are marked using the same colors as in a. A and C-G represent easA and easC-G respectively. W represents dmaW. c Relative abundances of N-formylvaline (4), fumivaline A (1), and festuclavine (2) and pyroclavine in A. fumigatus, P. commune, and P. expansum (gray, red, and blue, respectively) grown without copper (-) or with copper. Bars represent mean ± s.e.m. with six independent biological replicates for A. fumigatus wildtype and three for the other strains. p values were calculated by unpaired, two-sided t-test with Welch’s correction, ****P < 0.0001. d Relative abundances of N-formylvaline (4) and [7-2H]-N-formylvaline (4a) in extracts of wildtype A. fumigatus (grown without copper) extracted with deuterated or non-deuterated solvents. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Strecker-like peptide formation in fumivaline biosynthesis

Known ergot alkaloids can be divided into three classes, ergoclavines, ergoamides, and ergopeptines, based on their substituents at C-8 position (Supplementary Fig. 3a). d-lysergic acid and its amides are ergoamides derived from the oxidation of a methyl group at the C-8 position of ergoclavines. Ergopeptines12,13 are peptides of d-lysergic acid showing complex structures linked with a peptide bond at the C-8 position synthesized via a canonical NRPS pathway. In contrast, fumivalines identified in this study represent a new class of ergot alkaloids that contains an unprecedented peptide moiety attached to the C-7 position.

Fumivaline A biosynthesis could plausibly result from a nucleophilic attack of valine-derived isocyanide from CrmA on an imine intermediate of the ergot alkaloid biosynthesis (Fig. 2a, b). Therefore, we hypothesized that CrmA first generates valine isocyanide (5), which is then attached to a previously proposed precursor of festuclavine, dehydrofestuclavine (6), via nucleophilic attack of the isocyanide carbon of 5 at the imine carbon of 6. The formation of the carbon-carbon bond is then followed by hydration, resulting in the amide bond in position C-7 of the fumivalines (Fig. 2a). This mechanism is closely related to the well-known Strecker synthesis of amino acids and peptides from isocyanides and imine intermediates (Supplementary Fig. 3c).

The Strecker reactions usually yield racemic mixtures of α-amino acids as products. Correspondingly, our HPLC-HRMS analyses revealed multiple isomers of fumivalines A and B with identical MS2 spectra, likely representing diastereomers (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 2a), consistent with non-stereoselective peptide bond formation in fumivaline biosynthesis. Therefore, we asked whether fumivaline formation could have resulted from the reaction of valine isocyanide with festuclavine biosynthesis intermediates, e.g., 6, during the processing or extraction of the fungal cultures. Although we did not detect valine isocyanide in WT A. fumigatus and the amounts of valine isocyanide found in our analyses of the crmA overexpression mutant are small compared to the amounts of the other crmA-derived metabolites (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 2e), it seemed possible that most of the initially produced valine isocyanide could have converted into N-formylvaline during extraction. In fact, we found that synthetic valine isocyanide is rapidly hydrated to form N-formylvaline under acidic conditions, e.g., during HPLC analysis. To test whether the N-formylvaline in our fungal extracts was derived from the hydration of valine isocyanide, we extracted WT A. fumigatus cultures grown under copper-limited conditions with deuterium-labeled solvents. If valine isocyanide was hydrated during extraction or subsequent solvent removal, some of the resulting N-formylvaline would incorporate one deuterium. In fact, HPLC-HRMS analysis of the deuterium-labeled extracts indicated that 5.7% of the observed N-formylvaline was deuterated (Fig. 2d), indicating that roughly 18% of the detected N-formylvaline in the MS analyses is derived from hydrolysis during or post extraction (also see Methods, Supplementary Table 2). The majority of the detected N-fomylvaline thus formed prior to extraction, either non-enzymatically or via one of the five putative isocyanide hydratases in A. fumigatus identified via a search for homologs of ThiJ/PfpI isocyanide hydratases from Pseudomonas putida16 (Supplementary Table 3). Likewise, 29% of fumicicolin A was observed to incorporate one deuterium when using deuterium-labeled extraction solvents, indicating that the majority of detected fumicicolin A is derived from hydrolysis of an ester of valine isocyanide and D-mannitol during extraction (fumicicolin C, Supplementary Fig. 3d).

Conservation of fumivaline biosynthesis in Penicillium commune

Known producers of ergot alkaloids include the fungal genera Claviceps, Penicillium, Aspergillus, and Epichloë12,13. Many Aspergillus and Penicillium spp. produce ergoclavines as final products, whereas the Claviceps and Epichloë spp. instead produce d-lysergic acid derivatives, ergoamides, and ergopeptines (Supplementary Fig. 3a). crmA homologs are conserved in the ergot alkaloid producing P. commune as well as in the non-ergot alkaloid producing P. expansum (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1, and Supplementary Data 1). Further, the ergot alkaloid BGC in P. commune17–19 (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 4), like the ergot alkaloid BGC in A. fumigatus, includes the complete festuclavine pathway (dmaW, easA, and easC-G, Fig. 2a, b).

To determine whether production of N-formylvaline and fumivalines A and B is conserved in other fungal genera harboring both crm and ergot alkaloid BGCs, we analyzed the metabolome extracts from P. expansum and P. commune grown under both copper-limited and copper-replete conditions. The two Penicillium spp. produced N-formylvaline under copper-limited conditions, whereas neither N-formylvaline nor any of the other crmA-dependent metabolites we had identified in A. fumigatus were present under copper-replete conditions (Fig. 2c). These results confirmed that in Penicillium spp., as in A. fumigatus, production of crmA-dependent metabolites is strongly regulated by copper levels. In addition, we detected fumivalines A and B under copper-limited conditions in P. commune but not in P. expansum (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 3b), consistent with the presence of the festuclavine pathway in P. commune but not P. expansum (Fig. 2a, b). Taken together, our results show that fumivaline production requires crmA, the festuclavine pathway, and copper starvation.

Next we asked whether the putative precursors of the fumivalines, dehydrofestuclavine and valine isocyanide, can be exchanged between different fungi. For this purpose we used mixed cultures of A. fumigatus ΔcrmA, which produces ergot alkaloids but not valine isocyanide, with two different strains producing valine isocyanide but lacking ergot alkaloid biosynthesis: A. fumigatus ΔdmaW, which is defective in ergot alkaloid production, or OE::crmA of P. expansum, which lacks the ergot alkaloid pathway. Fumivaline A was not detected in the co-culture of A. fumigatus ΔcrmA and P. expansum, whereas appreciable amounts of fumivaline A were detected in the co-culture of the two A. fumigatus mutants (Supplementary Fig. 3e, f). The latter result suggests that valine isocyanide or ergot alkaloid precursors can be exchanged between the two A. fumigatus strains, but not between A. fumigatus ΔcrmA and P. expansum.

Conservation of crmA-dependent mannitol derivatives

Homology searches showed that crmA homologs are also found in several species that lack ergot alkaloid BGCs, e.g., P. expansum, as well as in several phytopathogenic fungi including A. brassicicola, L. maculans, and C. heterostrophus (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1, and Supplementary Data 1). crmA and crmB, with the addition of an α/β-hydrolase between the two genes, are conserved in A. brassicicola, L. maculans, and C. heterostrophus, whereas homologs of the two transporters, crmC and crmD, were not identified in any of these species (Supplementary Fig. 1).

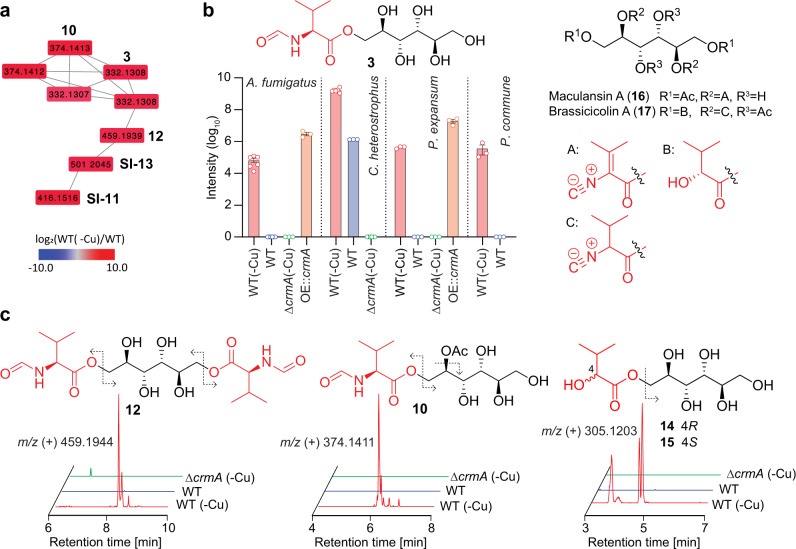

To investigate the role of crmA in fungi that lack ergot alkaloid BGCs, we constructed crmA-deletion mutants for P. expansum and C. heterostrophus. Untargeted metabolomic comparison of C. heterostrophus crmA mutant and WT under copper-limited conditions followed by MS2 networking revealed several groups of crmA- and copper-dependent MS features (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 4). Detailed analysis of their MS2 spectra indicated that they represented a variety of d-mannitol derivatives, named heterocicolins A-F (10−15), that appeared to be related to fumicicolin A, which was also detected, along with N-formylvaline. In addition to N-formylvaline moieties, the heterocicolins additionally incorporate acetyl and/or 2-hydroxyisovaleryl moieties, similar to brassicicolin A (Fig. 3b, c and Supplementary Fig. 5a–c). The identities of heterocicolins C, E, and F were confirmed with synthetic standards (Supplementary Fig. 5d), whereas the structures of acetylated heterocicolins A, B, and D, which are produced as mixtures of isomers, were proposed solely based on MS2 spectra (Supplementary Fig. 5c). Similar to the crmA-dependent metabolites in A. fumigatus, production of heterocicolins A-F, fumicicolins A and B, and N-formylvaline was abolished or strongly downregulated under copper-replete condition (Fig. 3b, c and Supplementary Fig. 5a, c). Similarly, crmA-dependent production of N-formylvaline and fumicicolins A and B was observed in P. expansum under copper-limited but not copper-replete conditions (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 5a). crmA overexpression in P. expansum resulted in increased production of N-formylvaline and fumicicolins A and B, as in A. fumigatus, and deletion of the gene eliminated production of all three metabolites (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 5a). Fumicicolins A and B were also detected in copper-limited P. commune (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 5a). The results indicate that crmA is required for the biosynthesis of the fumicicolins and related mannitol esters incorporating N-formylvaline.

Fig. 3. Identification of fumicicolin A and related metabolites.

a Partial representation of MS2 network (cosine >0.7) for WT C. heterostrophus in ESI+, showing the cluster containing fumicicolin A (3) and the heterocicolins (10–13). Shown nodes are strongly upregulated in wildtype grown without copper (see Supplementary Fig. 4 for full network). b Relative abundance of fumicicolin A (3) in A. fumigatus, C. heterostrophus, and Penicillium spp., and its structural similarity with known d-mannitol derivatives, maculansin A (16) and brassicicolin A (17). c ESI + ion chromatograms of heterocicolins A (10), C (12), E (14), and F (15) in WT C. heterostrophus grown with (blue) or without copper (red) and ΔcrmA (green) grown without copper. Dashed arrows indicate fragmentation in MS2 spectra. In b, bars represent mean ± s.e.m. with six independent biological replicates for A. fumigatus and C. heterostrophus wildtype under copper-limited conditions and three for the other strains/conditions. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The d-mannitol derived fumicicolins and heterocicolins are closely related to maculansin A (16), and brassicicolin A (17), previously described from L. maculans20 and A. brassicicola21, respectively (Fig. 3b), both of which also harbor crmA homologs (Supplementary Data 1), suggesting that 16 and 17 are derived from the crmA homologs in these species20–22. Differences in the composition of the crm cluster in these fungi may account for the observed differences in crmA-dependent d-mannitol derivatives. For example, the α/β-hydrolase present in the crm clusters of C. heterostrophus, L. maculans, and A. brassicicola, but not A. fumigatus, could be responsible for the additional attachment of the hydroxyisovaleric acid or acetic acid moieties in the crmA-dependent d-mannitol derivatives in these species (Supplementary Fig. 1). α/β-hydrolase fold family of enzymes can have diverse biosynthetic roles23 and have been shown to serve as acyltransferases in natural products biosynthesis in Acremonium chrysogenum24 and Caenorhabditis elegans25,26.

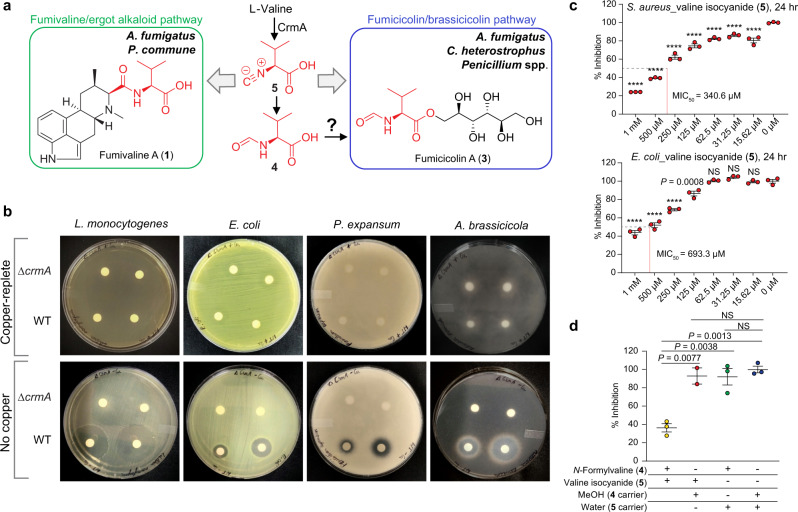

CrmA and associated products inhibit microbial growth from copper-starved A. fumigatus

Considering that several ergot alkaloids have antimicrobial properties27 and that several fungal isocyanides are antibacterial28,29, we tested whether CrmA-derived metabolites (Fig. 4a) have activity against a variety of bacterial and fungal species using disc assays. Disks soaked with crude extracts from WT A. fumigatus, the ΔcrmA deletion mutant, and OE::crmA mutant, from cultures grown under copper-limited and copper-replete conditions, were placed on lawns of four bacteria (Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus aureus) and four fungi (P. expansum, A. brassicicola, Candida albicans, and C. auris). Zones of inhibition were observed against all fungi and all bacteria, except P. aeruginosa, from all OE::crmA extracts and, less consistently, from WT extracts grown under copper-limited conditions, in contrast to no inhibition zones observed from extracts of copper-replete WT or either extract of the ΔcrmA mutant (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 5). These results suggested that CrmA metabolites contribute to the antimicrobial properties of A. fumigatus extracts.

Fig. 4. Putative biosynthesis of CrmA-derived metabolites in diverse fungi and antimicrobial activities.

a Fumivaline biosynthesis was observed in A. fumigatus and P. commune, which has the ergot alkaloid BGC and a homolog for crmA, whereas fumicicolin biosynthesis was observed in A. fumigatus, Penicillium spp. and C. heterostrophus, all of which harbor crmA homologs. b Growth of Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, Pencillium expansum, and Alternaria brassicicola is inhibited when challenged with extracts from WT but not ΔcrmA A. fumigatus grown without copper supplementation. Extracts from copper supplemented cultures do not inhibit microbial growth. c Valine isocyanide (5) significantly inhibits the growth of Staphylococcus aureus at all concentrations tested and inhibits the growth of E. coli at 125 μM and higher. MIC50, minimum inhibitory concentration to inhibit 50% growth. d Valine isocyanide (5) and N-formylvaline (4) show synergistic antifungal activity against Candida auris at 36 h. In c and d, bars represent mean ± s.e.m. with three independent biological replicates. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was performed to assess if the differences in survival at the range of concentrations were statistically significant (at p < 0.05) from survival with solvent only (0 µM), ****p < 0.0001, NS, not significant. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Next we selected four CrmA-derived metabolites, valine isocyanide, N-formylvaline, fumivaline A, and fumicicolin A, for testing against E. coli, S. aureus, C. auris and P. expansum. Both bacteria were inhibited by valine isocyanide (Fig. 4c), but not the other metabolites (Supplementary Fig. 6a). No metabolite showed antifungal activity when applied alone, but a combination of valine isocyanide with N-formylvaline inhibited C. auris growth at early time points, suggestive of possible synergy or additive effects of the two compounds (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 6b) against this pathogen, which is listed by the CDC as an emerging global health threat due to its inherent antifungal resistance30. Valine isocyanide had no significant impact on growth of A. fumigatus (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Taken together, these data suggested that valine isocyanide, possibly in combination with other A. fumigatus metabolites, was partly responsible for the observed crmA-dependent activity of A. fumigatus extracts against bacteria and may contribute to antifungal activities as well; all in the context of environments devoid or poor in copper availability.

Discussion

Filamentous fungi synthesize specific natural products to facilitate survival in response to various environmental stressors. Natural products can be elicited in response to abiotic stimuli, for example, UV induction of melanins protects fungal spores from harmful radiation15,31,32, or in response to competing microbes, where antibacterials33 or antifungals34 can confer competitive advantages to the producing fungus. Limitation of critical resources may also impact microbial secondary metabolite synthesis, as suggested by modulation of bacterial iron uptake genes dependent on confrontations with WT or a secondary metabolite mutant of Penicillium35. Like iron, copper levels are tightly regulated by microbes: copper is essential, but too much is toxic36,37. A. fumigatus maintains copper homeostasis in copper-deficient environments via the transcription factor MacA that activates copper importers during times of copper starvation4. Here we present a new paradigm in which MacA regulates the production of crmA-dependent antibiotics that inhibit the growth of potential A. fumigatus competitors under copper-deficient conditions. Our data support a view that crmA metabolites may function as conserved fitness factors in copper-deficient environments across fungal taxa (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Data 1). Valine isocyanide was efficient in inhibiting bacterial growth (Fig. 4c). This could be due to direct toxicity and/or the result of its copper chelating properties, as shown for other isocyanides including the A. fumigatus metabolite xanthocillin28. The antifungal effects of crude extracts of WT grown in copper-limited conditions may result from additive effects or synergy of valine isocyanide with other metabolites (Fig. 4b, d), including both CrmA- and non-CrmA-derived compounds. For instance, we found that in addition to CrmA metabolites, copper-starved A. fumigatus also produced higher quantities of helvolic acid, a known antifungal agent38–40 (Supplementary Fig. 7b). A. fumigatus occupies diverse primary niches, e.g., the lung as a common opportunistic pathogen, and as a common saprophyte in organic debris in fields and the rhizosphere where any advantage in the competition for scarce nutrients can be a significant fitness attribute (Fig. 5a). More detailed elucidation of the biological functions of the CrmA-derived metabolites we identified, e.g., to investigate synergistic activities, will require additional method development to ensure stability and accurate quantification of the involved metabolites, given that our isotope labeling studies demonstrated that valine isocyanide and its mannitol ester, fumicicolin C, are highly susceptible to hydrolysis and reaction with other nucleophiles.

Fig. 5. Phylogenetic tree and proposed functions of CrmA-derived metabolites in fungal ecology.

a CrmA proteins are found in three fungal taxa (for details, see Supplementary Data 1). CrmA is primarily found in pathogenic fungi including the insect pathogens Metarhizium, Cordyceps and Beauveria and the fungal parasite Trichoderma (Sordariomycetes), leaf blight pathogens Bipolaris(e.g., Cochliobolus) and Alternaria (Dothideomycetes) as well as in opportunistic pathogens and saprophytic Aspergillus and Pencillium spp. and the dermatophytic genus Trichophyton (Eurotiales). Our model proposes that CrmA metabolites are synthesized under copper starvation, where they act as virulence factors facilitating copper acquisition during fungal/host encounters or as antimicrobial compounds during competition in copper-limited niches. b Proposed rhabdoplanin A biosynthesis via an Ugi-like reaction in bacteria9. Panel (a) was created with BioRender.com.

Our analysis of CrmA-derived metabolites revealed biosynthetic pathways that produce (i) a new class of ergot alkaloids derived from Strecker-like peptide formation and (ii) valine isocyanide d-mannitol derivatives, whereby both pathways are strongly induced by copper starvation (Fig. 4a). In the former pathway, formation of the peptide bond in fumivaline biosynthesis appears to result from the nucleophilic attack of an isocyanide on an imine intermediate of ergot alkaloid biosynthesis, an unprecedented reaction in fungi that yields a new class of ergot alkaloids. Recently, a similar reaction was reported to be responsible for the formation of a peptide bond in the rhabdoplanins, a family of natural products isolated from the bacterium Xenorhabdus bovienii9 (Fig. 5b). Formation of the peptide bond in the rhabdoplanins was proposed to proceed as an Ugi-like reaction involving a decarboxylation step to generate the imine intermediate to which the isocyanide is then coupled, effectively resulting in replacement of the carbon lost by decarboxylation with the carbon from the isocyanide (Fig. 5b). In contrast, fumivaline A biosynthesis appears to proceed via nucleophilic attack of the isocyanide to the imine intermediate (Fig. 2a), thus producing a new ergot alkaloid carbon scaffold.

Ergot alkaloids have been primarily shown to be active against vertebrates ranging from insects to humans41,42 (Fig. 5a), and their pharmacological activities have been harnessed for diverse clinical uses43. Interestingly ergot alkaloid synthesis by insect pathogenic fungal Metarhizium spp. is tightly regulated and associated with insect colonization41, and we note that A. fumigatus ergot alkaloids are toxic to insects44. Regardless of fumivaline function, the intriguing reactivity of isocyanides shows their potential to function as versatile building blocks in the biosynthesis of other yet uncharacterized natural products9.

The valine isocyanide d-mannitol pathway, on the other hand, requires CrmA and the polyol, d-mannitol, where acylation, likely by an as-yet-unknown acyl transferase, with N-formylvaline or valine isocyanide followed by hydration yields fumicicolin A. Mannitol is a common sugar across the fungal Kingdom and thought to provide protection against osmotic stress45,46. Its role as a precursor for CmrA-dependent metabolites appears to be conserved in phytopathogenic fungi, such as A. brassicicola, L. maculans, and C. heterostrophus. In these species, CrmA homologs are located next to α/β-hydrolases that could be involved in the attachment of additional acyl moieties26. Notably, the CrmA homologs in these clades contain an additional transporter domain (Fig. 1a) that may also contribute to CrmA pathway metabolism in these fungi. The varying level of conservation of the other genes in the A. fumigatus Crm gene cluster, crmB, C, and D, in more distantly related species is consistent with a model in which CrmA-derived valine isocyanide is integrated into different pathways in different species, and is consistent with our finding that none of the other cluster genes are required for the CrmA-dependent metabolites in A. fumigatus.

Fumicicolin-related metabolites identified from phytopathogenic fungi, such as brassicicolin A synthesized by A. brassicicola and maculansins A and B produced by L. maculans, are host-selective phytotoxins8,20. Phytotoxin synthesis by leaf pathogens results in necrotic lesions in plant tissues and provides a source of easily obtained nutrients for the pathogen. A recent study of the plant pathogenic fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum showed that host copper was transported from healthy leaf tissues to necrotic tissues during infection, thus supplying the fungus with access to this micronutrient47. We speculate that the low copper availability in leaf tissues may be the signal to induce CrmA-derived phytotoxins which, in a similar manner as with S. sclerotiorum, could redirect copper supply to necrotic tissues colonized by the fungi (Fig. 5a).

The requirement of physically separated loci for fumivaline biosynthesis (conserved in both A. fumigatus and P. commune) demonstrates the complex signaling network fungi use to couple expression of non-clustered genes to increase unique chemical diversity. Although most secondary metabolites are reported to be generated from a single locus, examples of natural products requiring genes found in more than one locus are known, such as aspercryptin and nidulan A from A. nidulans48,49, aflatrem in A. flavus50, T toxin in C. heterostrophus51 and trichothecenes in some Fusarium spp.52. These examples suggest that greater consideration of cross-cluster exchange of intermediates could reveal other intriguing pathways. Our work further demonstrates that BGCs are still invisible to current bioinformatics tools (ICSs are not currently identified by BGC algorithms such as antiSMASH) but inferred from gene expression pattern changes in response to environmental stimuli, here copper starvation, can uncover unexpected chemical space. Our study shows that this approach can enable major advances in understanding fungal secondary metabolism, including genuinely new biosynthetic pathways and small-molecule functions. Given that homology searches revealed a large number of CrmA and other ICS homologs in fungi, it seems likely that isocyanides contribute to the production of many as-yet-undiscovered compounds.

In summary, our data show that the analysis of ICS-generated metabolites can reveal not only intriguing new structures and biosynthetic strategies but also striking connections of secondary metabolism with copper homeostasis. Our previous work on the A. fumigatus xanthocillin ICS-BGC showed that xanthocillin and xanthocillin-like isocyanides bind copper, deprive competing microbes of copper, and may facilitate copper uptake28. This latter study, coupled with the copper regulation of CrmA-dependent antimicrobials reported here, makes a strong case for micronutrient scarcity regulating fungal secondary metabolites biosynthesis to enable starvation survival via complementary ecological strategies (Fig. 5a).

Methods

Strains, media, and growth conditions

The fungal strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 6. Aspergillus and Penicillium strains were maintained as glycerol stocks and activated on solid glucose minimal medium (GMM)53 at 37 °C. Growth media were supplemented with 0.56 g uracil L−1, 1.26 g uridine L−1, 1.0 g arginine L−1 for pyrG and argB auxotrophs, respectively. Unless otherwise noted, all Aspergillus fumigatus strains were grown at 37 °C and Penicillum strains were grown at 28 °C. Cochliobolus heterostrophus strains were activated on a complete medium with xylose54. For metabolomic analysis, strains were inoculated (1.0 × 106 spores per mL) into 50 mL GMM53 in a 125-mL Erlenmeyer flask shaking at 200 rpm for 72 h. Escherichia coli strain DH5α was propagated in LB medium with appropriate antibiotics for plasmid DNA.

Gene cloning, plasmid construction, and genetic manipulations

All fungal transformations were accomplished by polyethylene glycol (PEG) based methods as previously described55,56.

A. fumigatus overexpression crmA

For the construction of the crmA overexpression cassettes, two 1000–1500-bp fragments immediately upstream and downstream of the AFUA_3G13690 (CrmA) translational start site were amplified by PCR from AF293 genomic DNA. A. parasiticus pyrG::A. nidulans gpdA(p) as the selectable marker and overexpression promoter, respectively was amplified from the plasmid pJMP957. The three fragments were fused by double joint PCR58 and then amplified using two nested primers to generate the deletion cassette (Supplementary Table 7). The overexpression cassette was transformed into strain TFYL45.1 to create strain TFYL82.2. Multiplex PCR was used to confirm the integration of the overexpression cassette at the native locus (data not shown). Single integration of the transformation construct was confirmed by Southern hybridization using two restriction enzyme digests (ScaI and MluI) and both the P-32 labeled 5′ and 3′ flanks (Supplementary Fig. 8a). To create a prototrophic strain (TJW209) of TFYL82.2, A. fumigatus argB was amplified using primers (fumargBF and fumargBR in Supplementary Table 7), transformed, and confirmed by PCR and sequencing (data not shown).

A. fumigatus deletion crmBC

TJW193.3 strain was made by a modified double joint method58. 1 kb DNA fragment of crmD open reading frame (ORF), a 2 kb DNA fragment of A. parasiticus pyrG and a 1 kb DNA fragment of crmA ORF. About 30 μL of Sephadex® G-50 purified third-round PCR product was used for fungal transformation in TFYL80.1. All of the following fungal transformations were done using the polyethylene glycol (PEG) based method previously described55. crmBC deletants were confirmed by PCR and Southern blot (Supplementary Fig. 8b).

P. expansum PEX2_062980 deletion and overexpression

For the deletion of the P. expansum crmA (PEX2_062980), ~1 kb upstream and downstream DNA regions of PEX2_062980 ORF were amplified by PCR with tails homologous to the hygromycin resistance self-excising β-rec/six blaster cassette59. Double joint PCR was used to build the knock-out construct58. For the overexpression of P. expansum crmA, ~1 kb upstream DNA region and ~1 kb of the ORF were amplified and fused to the overexpressed cassette, which consisted of the hygromycin resistance gene and the constitutive promoter H2Ap. The fungal transformation was done as described previously55. Twelve hours after transforming TJT14.1, an overlay of GMM (5 mL) containing sorbitol (1.2 M) and hygromycin (100 μg/mL) was put on top. The plates were incubated at 25 °C. The resulting transformants were subcultured twice on GMM containing hygromycin (100 μg/mL). The transformants were confirmed by PCR (Supplementary Fig. 8c). All primers for current gene cloning, plasmid construction, and genetic manipulations are listed in Supplementary Table 7.

C. heterostrophus crmA (JGI protein ID: 1220253, Genbank: EMD96666) deletion

Deletion of crmA was accomplished by PEG-mediated protoplast transformation using the split-marker approach56. The 5′ and 3′ regions flanking crmA were amplified from genomic DNA using primers, which included 5′ extensions complementary to those used to amplify the hygromycin B selectable marker (HygB). The HygB cassette was amplified from the plasmid pUCATPH60 as two separate overlapping fragments. The 5′ and 3′ crmA flanks were separately connected to the two HygB fragments by fusion PCR, generating two constructs. Targeted integration of the HygB cassette, and thus deletion of crmA, was accomplished by homologous recombination between the regions flanking crmA, and between the overlapping fragments of the HygB cassette. Candidate transformants were selected on 20 mL regeneration medium overlain with 10 mL 1% agar containing 150 μg/mL hygromycin B. Primers internal to crmA were used to screen candidates for the absence of crmA, while primers external to the original 5′ and 3′ flanks were used with primers internal to the HygB cassette to confirm targeted integration of the cassette. All primers are listed in Supplementary Table 7.

Nucleic acid analysis

Plasmid preparation, digestion with a restriction enzyme, gel electrophoresis, blotting, hybridization, and probe preparation were performed by standard methods61. Aspergillus DNA for diagnostic PCR was isolated using the previously described method62. Sequence data were analyzed using the LASERGENE software package from DNASTAR.

Analytical methods and equipment overview

NMR spectroscopy

NMR spectroscopy was performed on a Varian INOVA 600 MHz NMR spectrometer (600 MHz 1H reference frequency, 151 MHz for 13C) equipped with an HCN indirect-detection probe or a Bruker Avance III HD (800 MHz 1H reference frequency, 201 MHz for 13C) equipped with a 5-mm CPTCL 1H-13C/15N cryoprobe. Non-gradient phase-cycled dqfCOSY spectra were acquired using the following parameters: 0.6 s acquisition time; 400–600 complex increments; 8, 16, or 32 scans per increment. HSQC and HMBC spectra were acquired with these parameters: 0.25 s acquisition time, 200–500 increments, and 8–64 scans per increment. 1H, 13C-HMBC spectra were optimized for JH,C = 6 Hz. HSQC spectra were acquired without decoupling, which allowed to measure one-bond proton-carbon coupling constants (1JH,C). NMR spectra were processed and baseline corrected using MestreLabs MNOVA software packages.

Mass spectrometry

LC−MS was performed on a Thermo Fisher Scientific Vanquish UHPLC system coupled with a Thermo Q-Exactive HF hybrid quadrupole-orbitrap high-resolution mass spectrometer equipped with a HESI ion source. Mass spectrometer parameters were used as spray voltage 3.5 kV, capillary temperature 380 °C, probe heater temperature 400 °C; 60 sheath flow rate, 20 auxiliary flow rate, and one spare gas; S-lens RF level 50, resolution 240,000, AGC target 3 × 106. The instrument was calibrated weekly with positive and negative ion calibration solutions (Thermo Fisher). Each sample was analyzed in negative and positive ionization modes using an m/z range of 100 to 800.

Chromatography

Flash chromatography was performed using a Teledyne ISCO CombiFlash system. Semi-preparative chromatography was performed on an Agilent 1100 series HPLC system using Agilent Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C8 or XDB-C18 columns (25 cm × 10 mm, 5 μm particle diameter).

Metabolite extraction and LC–MS analysis

Liquid fungal cultures (50 mL), including fungal tissue and medium, were frozen using liquid nitrogen and lyophilized. The lyophilized residues were extracted with 20 mL of methanol for 2.5 h with vigorous stirring. Extracts were pelleted at 5000×g for 5 min, and supernatants were transferred to 40 mL glass vials. Samples were then dried in a SpeedVac (Thermo Fisher Scientific) vacuum concentrator. Dried materials were resuspended in 1 mL of methanol and centrifuged to remove insoluble materials, and supernatants were transferred to 2 mL HPLC vials and subjected to UHPLC-HRMS analysis, as follows. An Agilent Zorbax RRHD Eclipse XDB-C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 μm particle diameter) was used with acetonitrile (organic phase) and 0.1% formic acid in water (aqueous phase) as solvents at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. A solvent gradient scheme was used, starting at 1% organic for 3 min, followed by a linear increase to 100% organic over 20 min, holding at 100% organic for 5 min, decreasing back, and holding at 1% organic for 3 min, for a total of 28 min.

Feature detection and characterization

LC−MS RAW files were converted to mzXML format (centroid mode) using MSconvert (ProteoWizard), followed by analysis using the XCMS analysis feature in Metaboseek (metaboseek.com) based on the centWave XCMS algorithm to extract features63. Peak detection values were set as 4 ppm, 3 to 20 peak width, 3 snthresh, 3 and 100 prefilter, FALSE fitgauss, 1 integrate, TRUE firstBaselineCheck, 0 noise, wMean mzCenterFun, and −0.005 mzdiff. XCMS feature grouping values were set as: 0.2 minfrac, 2 bw, 0.002 mzwid, 500 max, 1 minsamp, and FALSE usegroup. Metaboseek peak filling values were set as 5 ppm_m, 5 rtw, and TRUE rtrange. The resulting tables of all detected features were then processed with the Metaboseek data explorer. To remove background-derived features, we first applied filters that only retained entries with a retention time window of 1 to 20 min and then applied maximum intensity (at least one repeat >10,000), and Peak Quality (>0.98) thresholds, as calculated by Metaboseek10. To select differential features, we applied a filter (using Metaboseek) to select entries with peak area ratios larger than 20 (upregulated by copper starvation in wildtype) or 5 (up in overexpression mutants compared to wild types). We manually curated the resulting list to remove false positive entries (i.e., features that upon manual inspection of raw data were not differential), which revealed a combined total of 236 differential features from positive and negative ionization modes. For verified differential features, we examined elution profiles, isotope patterns, and MS1 spectra to find molecular ions and remove adducts, fragments, and isotope peaks. The remaining features were put on the inclusion list for MS2 (ddMS2) characterization. Positive and negative ionization mode data were processed separately. To acquire MS2 spectra, we ran a top-10 data-dependent MS2 method on a Thermo Q-exactive-HF mass spectrometer with MS1 resolution 60,000, AGC target 3 × 106, maximum injection time (IT) 100 ms, MS2 resolution 30,000, AGC target 5 × 105, maximum IT 100 ms, isolation window 1.0 m/z, stepped normalized collision energy (NCE) 20 and 40 for both positive and negative ion modes, dynamic exclusion 3 s.

The initial comparative metabolomic analysis referred to in Fig. 1b was performed using six independent biological replicates. In addition, the crmA-dependence of the identified features was confirmed via HPLC-HRMS analysis of multiple additional sets of metabolite extracts used for compound isolation and bioassays.

Chromatographic enrichment of compounds 1 and 6

Liquid fungal cultures (50 mL × 20), including fungal tissue and medium, were frozen using a dry ice acetone bath and lyophilized. The combined lyophilized residues were extracted with 500 mL of methanol for 3.5 h with vigorous stirring. Extracts were filtered over cotton, evaporated to dryness, and stored in 8 mL vials. Crude extracts were fractionated via semi-preparative HPLC using an Agilent XDB C-8 column (25 cm × 10 mm, 5 μm particle diameter) with acetonitrile (organic phase) and 0.1% acetic acid in water (aqueous phase) as solvents at a flow rate of 3.0 mL/min. A solvent gradient scheme was used, starting at 5% organic for 3 min, followed by a linear increase to 100% organic over 27 min, holding at 100% organic for 5 min, decreasing back to 5% organic for 0.1 min and holding at 5% organic for the final 4.9 min, for a total of 40 min. Further purification of fractions containing 1 and 6 was accomplished by semi-preparative HPLC using the same Agilent XDB C-8 column with acetonitrile (organic phase) and 0.1 M (pH 7.0) ammonium acetate in water (aqueous phase) as solvents at a flow rate of 3.0 mL/min with same gradient scheme as shown above.

Analysis via Marfey’s method

Fumivaline A (0.5 mg) was hydrolyzed in 0.5 mL of 6 N hydrochloric acid at 115 °C. After 2 h, the reaction vial was cooled down in ice water for 3 min. Then the hydrochloric acid was removed in vacuo and the dry material was resuspended in 0.5 mL of water, and dried three times to remove residual hydrochloric acid completely. The residue was dissolved in 100 μL of 1 N sodium bicarbonate, followed by the addition of 50 μL of 10 mg/mL L-FDAA (1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrophenyl-5-l-alanine amide) in acetone. The reaction mixture was incubated in a water bath at 80 °C for 3 min. Then 50 μL of 2 N hydrochloric acid was added to quench the reaction by neutralization. Additionally, 300 μL of aqueous 50% acetonitrile was added to the solution to dissolve the reaction products. A 2 μL aliquot of the reaction mixture was analyzed by LC/MS using the gradient scheme described above. The same procedure was performed for a metabolome fraction containing N-formylvaline. Standards of l-valine and d-valine were derivatized with l-FDAA as described above. The FDAA derivatives of valine derived from fumivaline A and N-formylvaline showed the same retention time as the FDAA derivative of l-valine, which established that the valine moieties in N-formylvaline and fumivaline A possessed L-configuration (Supplementary Fig. 2g, h).

Fungal culture extraction with deuterium-labeled solvents

About 5 mL of 7:3 mixture of methanol-d1 and deuterium oxide were added to liquid fungal cultures (5 mL), including fungal tissue and medium and vigorously mixed. The sample was frozen using a dry ice acetone bath and lyophilized. The lyophilized residues were extracted with 2.5 mL of 7:3:10 mixture of methanol-d1, deuterium oxide, and water for 24 h with vigorous stirring. Extracts were pelleted at 5000 × g for 10 min, and supernatants were transferred to another 4 mL glass vials. Samples were then dried in a SpeedVac (Thermo Fisher Scientific) vacuum concentrator. Dried materials were resuspended in 100 µL of methanol and vortexed for 1 min. Samples were pelleted at 5000×g for 5 min, and supernatants were transferred to 2 mL HPLC vials. Clarified extracts were transferred to fresh HPLC vials and stored at −20 °C until analysis. Percent of valine isocyanide hydrolysis was calculated using the following formula: Ratio (%) = (deuterated N-formylvaline, %) × (abundance of H + abundance of D)/(abundance of D), which takes into account the ratio between hydrogen and deuterium in the extraction solvent, also considers the contribution from water in the culture media (Supplementary Table 2).

MS2-based molecular networking

An MS2 molecular network64 was created using Metaboseek version 0.9.7 and visualized in Cytoscape65. Features were matched with their respective MS2 scan within an m/z window of 5 ppm and a retention time window of 15 s, using the MS2scans function. To construct a molecular network, the tolerance of the fragment peaks was set to an m/z of 0.002 or 5 ppm, the minimum number of peaks was set to 3, and the noise level was set to 2%. Once the network was constructed, a cosine value of 0.7 was used, the number of possible connections was restricted to 6 for positive ion mode, and the maximum cluster size was restricted to 200 for positive ion mode.

Synteny analysis of crmA loci

To locate crmA homologs, a local BLAST66 search was conducted against a database of A. fumigatus (NCBI accession: GCF_000002655.1), A. brassicicola (ATCC96836)67, C. heterostrophus (GCA_000338975.1), and P. commune (GCA_000338975.1, sequenced generously received from Dr. Benjamin Wolfe)19. Protein domains were predicted for the eight genes flanking the left and right of all three crmA homologs by searching against the CDD v3.19 database on the NCBI conserved domains web tool68. The expected value threshold was kept at 0.01 and composition-based statistic adjustment was turned on. Clinker and clustermap.js was utilized to make comparisons of gene cluster similarity69. Similarity scores were calculated by Clinker and are based on the cumulative sequence identity of homologous sequences and the number of shared contiguous sequence pairs. Visualization of the results was done with clustermap.js.

Identification of all crmA homologs

To locate all of the crmA homologs, we extracted the predicted crmA isocyanide synthase domain amino acid sequence from A. fumigatus. This was done to capture variations of the crmA gene that have homologous ICS regions. The following was run using BLAST+70 version 2.12.0 on 11/01/2021: blastp -query ICS_crmA.fa -remote -db nr -evalue 1e-6 -out ICScrmAHits.txt -outfmt “6 qseqid sseqid sacc sgi staxids sscinames scomnames sblastnames sskingdoms stitle length mismatch gapopen qstart qend sstart send sstrand evalue bitscore”. As only the crmA isocyanide region was used in this search, we filtered out hits that had a protein length of less than 1000 amino acids (for reference the crmA protein in A. fumigatus is 1537 amino acids). This prevented returned hits from proteins that were solely an ICS domain (Supplementary Data 1). To generate a visualization of these hits, species with homologs to the crmA protein were mapped onto a taxonomic tree that was generated by identifying single copy orthologs from BUSCO71, followed by an estimation of the maximum-likelihood phylogeny with IQ-TREE72.

Antimicrobial assay using crude extracts

Antimicrobial assays were assessed for Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, P. expansum, A. brassicicola, Candida albicans, and C. auris using Kirby–Baur’s disc-diffusion method73. A loopful of E.coli was inoculated in 4 mL of LB media and L. monocytogenes in 4 mL of BHI (brain–heart infusion) liquid media, followed by incubation at 37 °C in a shaker incubator at 200 rpm overnight. C. auris and C. albicans were grown on YEPD (yeast extract peptone dextrose) media at 33 °C for 48 h, a small amount of the yeast was scraped off of the plates using a sterile toothpick and resuspended in 4 ml 0.85% sodium chloride. A sterile cotton swab was used to dip and swab the yeast and overnight bacterial cultures, completely and evenly on the respective agar plates. 1 × 106 spores from 5-day old P. expansum plates and 7-day old A. brassicicola plates were inoculated in 10 mL GMM top agar (GMM with 0.75% agar) and MEA top agar (MEA with 0.75% agar), respectively, before pouring them on the respective agar plates. The lyophilized crude extract samples were resuspended with 500 uL of 100% methanol and mixed well. Sterile 6 mm blank paper disks were individually injected with 25 µL of crude extracts from wildtype A. fumigatus, crmA deletion and crmA overexpression strains grown on GMM liquid media with copper and without copper. They were then placed at equal distances from each other on all the bacterial and fungal plates, immediately after their inoculation. The bacterial plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C, while the P. expansum plate was incubated at 25 °C for 3 days and A. brassicicola at 25 °C for 5 days. The Candida plates were incubated at 33 °C for 2 days. The presence or absence of antimicrobial susceptibility with all the extracts was determined and zones of inhibition were measured at the end of the respective incubation periods.

Antimicrobial assay using purified metabolites

All antimicrobial assays with purified compounds were performed in flat-bottomed 96-well microtiter plates. Bacteria used in these assays (E. coli and S. aureus) were used from fresh plates of LB incubated at 30 °C overnight. Liquid cultures were raised in 3 mL of liquid LB medium by inoculating a single colony incubated at 30 °C with constant shaking at 250 rpm. Overnight cultures were harvested with centrifugation, washed 2X with phosphate-buffered saline, and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline to be used as inoculum for the assays.

Samples of purified fumivaline A, synthetic fumicicolin A, synthetic (S)−2-isocyanoisovaleric acid, and N-formylvaline obtained from TCI America were resuspended to a final concentration of 10 mM in water, DMSO, and methanol respectively, which were treated as stocks. A concentration gradient was set up using these stocks for each metabolite against each bacterium. All metabolites were set up at half gradients; valine isocyanide with 1 mM as the highest and 15 µM as the lowest concentrations; fumivaline A and N-formylvaline with 250 µM and 4 µM as the highest and lowest concentrations respectively. Each well of the 96-well plate was inoculated to hold a final volume of 200 µL with 2.5% by volume of the desired metabolite (for fumivaline A and N-formylvaline) and 10% by volume of valine isocyanide. Corresponding solvents were used as positive control and gentamicin at 50 µg/mL was used as the negative control. Bacteria were added to obtain a final OD600 = 0.01. The plates were incubated for 24 h before OD600 was read again. Percent survival reported was calculated by normalizing OD600 at 24 h to OD600 at inoculation (0 h).

Antifungal assays were carried out against C. auris with the stocks prepared as above. Synergistic activities of valine isocyanide with N-formylvaline (see results in Fig. 4d) were tested in 96-well plates. The compounds were added at concentrations of 1 mM and 250 µM, respectively, with corresponding solvent combinations as a control in a total volume of 200 µL of YPD medium (10 g yeast extract, 20 g peptone, and 20 g glucose in 1 L). Three replicates were monitored per treatment. C. auris cells were grown overnight in a 1 mL YPD medium at 30 °C without shaking. The cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline and added to YPD at a final concentration of 5 × 104 cells/mL. The plates were incubated at 30 °C and OD600 readings were taken after 24–36 h. Percent survival reported was calculated by normalizing OD600 at 36 h to OD600 at inoculation (0 h).

Antifungal activity of valine isocyanide against A. fumigatus was tested using stocks prepared as above. The compound was tested with 5 mM as the highest concentration and a serial half dilution from 1 mM to 15.62 µM as the lowest concentration. About 100 µL of the A. fumigatus spores in GMM liquid media74,75 were inoculated to each well of the 96-well plate for a final concentration of 1 × 105 cells/mL with 100 µL of each concentration of valine isocyanide in water. Water was used as negative control and polymyxin B76 at 40 mM was used as a positive control. Three replicates were monitored per treatment. The entire experiment was set up on ice and optical density was checked at 600 nm upon completion. The plate was then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, after which contents of the wells were mixed using a multichannel pipette to resuspend fungi, and OD600 was measured again.

One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was performed to assess if the differences in survival at the range of concentrations were statistically significant (at p value <0.05) from survival with solvent only.

Data and statistical analysis

LC–MS data were collected using Thermo Scientific Xcalibur software version 4.1.31.9. LC–MS data were analyzed using Metaboseek software version 0.9.7 and quantification was performed via integration in Excalibur Quan Browser version 4.1.31.9. NMR spectra were processed and baseline corrected using MestreLabs MNOVA software packages version 11.0.0-17609. All statistical analysis were performed with GraphPad Prism version 9.2 or Metaboseek version 0.9.7. The P values of datasets were determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test with a 95% confidence interval unless specified otherwise.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health R01 2R01GM112739-05A1 to N.P.K., the National Institute of General Medical Sciences T32 GM135066 to G.N., NIH 5R44AI140943-03 to J.W.B., as well as the Howard Hughes Medical Foundation (to F.C.S.). We thank Dr. Benjamin Wolfe for providing us with the P. commune sequence and Dr. Milton Drott for providing the fungal taxonomic tree used in Fig. 5a.

Source data

Author contributions

N.P.K. and F.C.S. supervised the study. T.H.W. and F.C.S. characterized and identified metabolites and biosynthetic pathways. J.W.B. and F.Y.L. created all of the A. fumigatus mutants used. N.N. and N.V. conducted antimicrobial assays. G.N. performed synteny and CrmA computational analysis. J.B.G. and B.G.T. created mutants of C. heterostrophus. C.G. created the P. expansum mutants. T.H.W., N.P.K., and F.C.S. wrote the manuscript with input from all co-authors.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

MS and MS2 data for all fungal metabolome samples analyzed in this study (A. fumigatus, P. commune, P. expansum, C. heterostrophus, co-culture of A. fumigatus and P. expansum, and deuterium labeling experiments) are available at the GNPS Web site (massive.ucsd.edu) under MassIVE ID number MSV000089206. The crmA sequence data used in this study are available in the NCBI database under accession code XP_754255 for A. fumigatus, XP_016596276 for P. expansum, and EMD96666 for C. heterostrophus. The sequence data used in this study are available in the NCBI database under accession code GCF_000002655.1 for A. fumigatus, GCA_008931945.1 for P. commune, GCA_000338975.1 for C. heterostrophus. The sequence data for A. brassicicola is available in the JGI Mycocosm database under accession code ATCC96836. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nancy P. Keller, Email: npkeller@wisc.edu

Frank C. Schroeder, Email: schroeder@cornell.edu

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-022-32394-x.

References

- 1.Robey, M. T., Caesar, L. K., Drott, M. T., Keller, N. P. & Kelleher, N. L. An interpreted atlas of biosynthetic gene clusters from 1,000 fungal genomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA118, e2020230118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Keller NP. Fungal secondary metabolism: regulation, function and drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019;17:167–180. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0121-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim, F. Y. et al. Fungal isocyanide synthases and xanthocillin biosynthesis in Aspergillus fumigatus. MBio9, e00785-18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Cai Z, et al. Cu-sensing transcription factor Mac1 coordinates with the Ctr transporter family to regulate Cu acquisition and virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2017;107:31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiemann P, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus copper export machinery and reactive oxygen intermediate defense counter host copper-mediated oxidative antimicrobial offense. Cell Rep. 2017;19:1008–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson SL, Panaccione DG. Chemotypic and genotypic diversity in the ergot alkaloid pathway of Aspergillus fumigatus. Mycologia. 2012;104:804–812. doi: 10.3852/11-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallwey C, Matuschek M, Xie XL, Li SM. Ergot alkaloid biosynthesis in Aspergillus fumigatus: conversion of chanoclavine-I aldehyde to festuclavine by the festuclavine synthase FgaFS in the presence of the old yellow enzyme FgaOx3. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010;8:3500–3508. doi: 10.1039/c003823g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedras MSC, Park MR. The biosynthesis of brassicicolin A in the phytopathogen Alternaria brassicicola. Phytochemistry. 2016;132:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oh J, Kim NY, Chen H, Palm NW, Crawford JM. An Ugi-like biosynthetic pathway encodes Bombesin receptor subtype-3 agonists. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:16271–16278. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b04183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helf MJ, Fox BW, Artyukhin AB, Zhang YK, Schroeder FC. Comparative metabolomics with Metaboseek reveals functions of a conserved fat metabolism pathway in C. elegans. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:782. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28391-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujii K, Ikai Y, Oka H, Suzuki M, Harada K. A nonempirical method using LC/MS for determination of the absolute configuration of constituent amino acids in a peptide: combination of Marfey’s method with mass spectrometry and its practical application. Anal. Chem. 1997;69:5146–5151. doi: 10.1021/ac970289b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen JJ, Han MY, Gong T, Yang JL, Zhu P. Recent progress in ergot alkaloid research. RSC Adv. 2017;7:27384–27396. doi: 10.1039/C7RA03152A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallwey C, Li SM. Ergot alkaloids: structure diversity, biosynthetic gene clusters and functional proof of biosynthetic genes. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011;28:496–510. doi: 10.1039/C0NP00060D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coyle CM, Panaccione DG. An ergot alkaloid biosynthesis gene and clustered hypothetical genes from Aspergillus fumigatus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:3112–3118. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.6.3112-3118.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blachowicz A, et al. Contributions of spore secondary metabolites to UV-C protection and virulence vary in different Aspergillus fumigatus strains. MBio. 2020;11:1–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.03415-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goda M, Hashimoto Y, Shimizu S, Kobayashi M. Discovery of a novel enzyme, isonitrile hydratase, involved in nitrogen-carbon triple bond cleavage. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:23480–23485. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007856200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vinokurova NG, Ozerskaya SM, Baskunov BP, Arinbasarov MU. The Penicillium commune thom and Penicillium clavigerum demelius fungi producing fumigaclavines A and B. Microbiology. 2003;72:149–151. doi: 10.1023/A:1023255628225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matuschek M, Wallwey C, Wollinsky B, Xie X, Li SM. In vitro conversion of chanoclavine-I aldehyde to the stereoisomers festuclavine and pyroclavine controlled by the second reduction step. RSC Adv. 2012;2:3662–3669. doi: 10.1039/c2ra20104f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bodinaku, I. et al. Rapid phenotypic and metabolomic domestication of wild penicillium molds on cheese. MBio10, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Pedras MSC, Yu Y. Structure and biological activity of maculansin A, a phytotoxin from the phytopathogenic fungus Leptosphaeria maculans. Phytochemistry. 2008;69:2966–2971. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gloer JB, Poch GK, Short DM, McCloskey DV. Structure of Brassicicolin a: a novel isocyanide antibiotic from the phylloplane fungus Alternaría brassicicola. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:3758–3761. doi: 10.1021/jo00251a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MARCONI GG, et al. A32390A, a new biologically active metabolite. II. Isolation Struct. J. Antibiot. 1978;31:27–32. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.31.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rauwerdink A, Kazlauskas RJ. How the same core catalytic machinery catalyzes 17 different reactions: the serine-histidine-aspartate catalytic triad of α/β-hydrolase fold enzymes. ACS Catal. 2015;5:6153–6176. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.5b01539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lejon S, Ellis J, Valegård K. The last step in cephalosporin C formation revealed: crystal structures of deacetylcephalosporin C acetyltransferase from Acremonium chrysogenum in complexes with reaction intermediates. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;377:935–944. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le HH, et al. Modular metabolite assembly in Caenorhabditis elegans depends on carboxylesterases and formation of lysosome-related organelles. Elife. 2020;9:1–42. doi: 10.7554/eLife.61886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wrobel CJJ, et al. Combinatorial assembly of modular glucosides via carboxylesterases regulates C. elegans starvation survival. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021 doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c05908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwarz G, Eich E. Influence of ergot alkaloids on growth of Streptomyces purpurascens and production of its secondary metabolites. Planta Med. 1983;47:212–214. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-969988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raffa N, et al. Dual-purpose isocyanides produced by Aspergillus fumigatus contribute to cellular copper sufficiency and exhibit antimicrobial activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118:1–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2015224118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liss SN, Brewer D, Taylor A, Jones GA. Antibiotic activity of an isocyanide metabolite of Trichoderma hamatum against rumen bacteria. Can. J. Microbiol. 1985;31:767–772. doi: 10.1139/m85-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antifungal susceptibility testing and interpretation. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/candida-auris/c-auris-antifungal.html (2020).

- 31.Lim, S. et al. Identification of the pigment and its role in UV resistance in Paecilomyces variotii, a Chernobyl isolate, using genetic manipulation strategies. Fungal Genet. Biol. 152, 103567 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Singaravelan N, et al. Adaptive melanin response of the soil fungus Aspergillus niger to UV radiation stress at ‘Evolution Canyon’, Mount Carmel, Israel. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:2–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Venkatesh N, et al. Secreted secondary metabolites reduce bacterial wilt severity of tomato in bacterial–fungal co-infections. Microorganisms. 2021;9:1–17. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9102123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tong S, et al. Characterization of a fungal competition factor: Production of a conidial cell-wall associated antifungal peptide. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:1–29. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pierce EC, et al. Bacterial–fungal interactions revealed by genome-wide analysis of bacterial mutant fitness. Nat. Microbiol. 2021;6:87–102. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-00800-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raffa, N., Osherov, N. & Keller, N. P. Copper utilization, regulation, and acquisition by aspergillus fumigatus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 1980 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Antsotegi-Uskola M, Markina-Iñarrairaegui A, Ugalde U. New insights into copper homeostasis in filamentous fungi. Int. Microbiol. 2020;23:65–73. doi: 10.1007/s10123-019-00081-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu JY, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus CY018, an endophytic fungus in Cynodon dactylon as a versatile producer of new and bioactive metabolites. J. Biotechnol. 2004;114:279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao J, et al. Antimicrobial metabolites from the endophytic fungus pichia guilliermondii Isolated from Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis. Molecules. 2010;15:7961–7970. doi: 10.3390/molecules15117961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li XJ, Zhang Q, Zhang AL, Gao JM. Metabolites from Aspergillus fumigatus, an endophytic fungus associated with Melia azedarach, and their antifungal, antifeedant, and toxic activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60:3424–3431. doi: 10.1021/jf300146n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leadmon CE, et al. Several Metarhizium species produce ergot alkaloids in a condition-specific manner. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020;86:1–13. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00373-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blodgett DJ. Fescue toxicosis. Vet. Clin. North Am. Equine Pract. 2001;17:567–577. doi: 10.1016/S0749-0739(17)30052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baron EP, Tepper SJ. Revisiting the role of ergots in the treatment of migraine and headache. Headache. 2010;50:1353–1361. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Panaccione DG, Arnold SL. Ergot alkaloids contribute to virulence in an insect model of invasive aspergillosis. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09107-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meena M, Prasad V, Zehra A, Gupta VK, Upadhyay RS. Mannitol metabolism during pathogenic fungal-host interactions under stressed conditions. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calmes B, et al. Role of mannitol metabolism in the pathogenicity of the necrotrophic fungus Alternaria brassicicola. Front. Plant Sci. 2013;4:1–18. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ding Y, et al. Sclerotinia sclerotiorum utilizes host-derived copper for ROS detoxification and infection. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:1–22. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chiang YM, et al. Development of genetic dereplication strains in Aspergillus nidulans results in the discovery of aspercryptin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:1662–1665. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andersen, M. R. et al. Accurate prediction of secondary metabolite gene clusters in filamentous fungi. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA110, E99–107 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Nicholson MJ, et al. Identification of two aflatrem biosynthesis gene loci in Aspergillus flavus and metabolic engineering of Penicillium paxilli to elucidate their function. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:7469–7481. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02146-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Inderbitzin P, Asvarak T, Turgeon BG. Six new genes required for production of T-toxin, a polyketide determinant of high virulence of Cochliobolus heterostrophus to maize. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2010;23:458–472. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-23-4-0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meek IB, Peplow AW, Ake C, Phillips TD, Beremand MN. Tri1 encodes the cytochrome P450 monooxygenase for C-8 hydroxylation during trichothecene biosynthesis in Fusarium sporotrichioides and resides upstream of another new Tri gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:1607–1613. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.3.1607-1613.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shimizu K, Keller NP. Genetic involvement of a cAMP-dependent protein kinase in a G protein signaling pathway regulating morphological and chemical transitions in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics. 2001;157:591–600. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.2.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leach J, Lang BR, Yoder OC. Methods for selection of mutants and in vitro culture of Cochliobolus heterostrophus. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1982;128:1719–1729. [Google Scholar]