Abstract

Objective

To assess the risk of preterm birth, small for gestational age at birth, and stillbirth after covid-19 vaccination during pregnancy.

Design

Population based retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Ontario, Canada, 1 May to 31 December 2021.

Participants

All liveborn and stillborn infants from pregnancies conceived at least 42 weeks before the end of the study period and with gestational age ≥20 weeks or birth weight ≥500 g.

Main outcome measures

Using Cox regression, hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were estimated for preterm birth before 37 weeks (overall and spontaneous preterm birth), very preterm birth (<32 weeks), small for gestational age at birth (<10th centile), and stillbirth. Vaccination against covid-19 was treated as a time varying exposure in the outcome specific risk window, and propensity score weighting was used to adjust hazard ratios for potential confounding.

Results

Among 85 162 births, 43 099 (50.6%) occurred in individuals who received one dose or more of a covid-19 vaccine during pregnancy—42 979 (99.7%) received an mRNA vaccine. Vaccination during pregnancy was not associated with any increased risk of overall preterm birth (6.5% among vaccinated v 6.9% among unvaccinated; adjusted hazard ratio 1.02, 95% confidence interval 0.96 to 1.08), spontaneous preterm birth (3.7% v 4.4%; 0.96, 0.90 to 1.03), or very preterm birth (0.59% v 0.89%; 0.80, 0.67 to 0.95). No increase was found in risk of small for gestational age at birth (9.1% v 9.2%; 0.98, 0.93 to 1.03) or stillbirth (0.25% v 0.44%; 0.65, 0.51 to 0.84). Findings were similar by trimester of vaccination, mRNA vaccine product, and number of doses received during pregnancy.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that vaccination against covid-19 during pregnancy is not associated with a higher risk of preterm birth, small for gestational age at birth, or stillbirth.

Introduction

Infection with SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy has been associated with higher risks of admission to hospital, admission to an intensive care unit, and death for pregnant individuals.1 2 3 Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 infection has been associated with a higher risk of preterm birth,3 4 5 fetal growth restriction,4 postpartum haemorrhage,4 and stillbirth.6 Many countries recommend covid-19 vaccination during pregnancy,7 which has been shown to be effective against covid-19 in pregnant individuals8 as well as their newborns9 10; however, vaccine coverage among pregnant individuals remains lower than among women of reproductive age.11 12

Safety concerns about covid-19 vaccination during pregnancy remains a potential obstacle to improving coverage. As of July 2022, results published from epidemiological studies are reassuring—two case-control studies of covid-19 vaccination in early pregnancy found no association with spontaneous abortion.13 14 Our recent study of pregnancies to 30 September 2021, including 22 660 individuals vaccinated during the second or third trimester, did not show any association with adverse peripartum outcomes such as postpartum haemorrhage or low Apgar scores.15 However, fewer studies have examined risk of adverse birth outcomes associated with prenatal covid-19 vaccination. A population based birth registry study from Sweden and Norway found no increased risks of preterm birth or small for gestational age at birth; importantly, stillbirth also was not associated with covid-19 vaccination in the study.16 Two cohort studies including pregnant individuals insured through large health maintenance organisations observed no associations with preterm birth or small for gestational age at birth.17 18 In a large, province-wide population, we evaluated whether covid-19 vaccination during pregnancy was associated with risk of preterm birth (including spontaneous preterm birth and very preterm birth), small for gestational age at birth, or stillbirth.

Methods

We followed guidance for conducting studies of covid-19 vaccination during pregnancy19 and reporting observational studies.20

Study design, population, and data sources

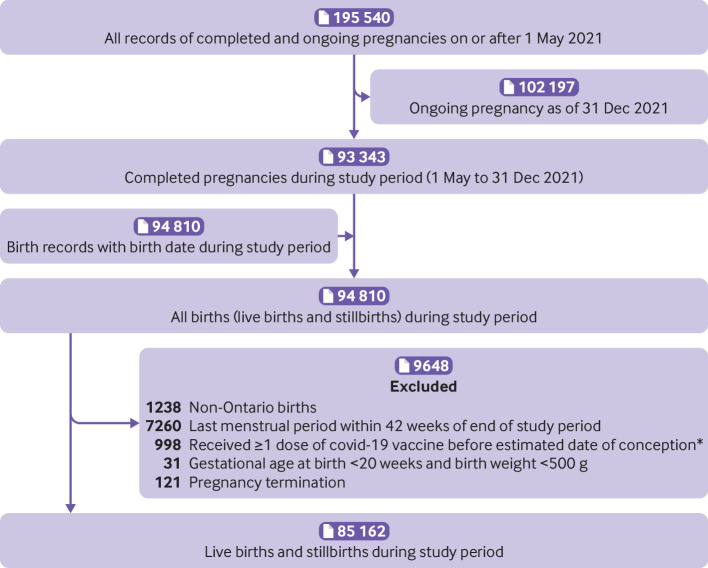

We conducted a population based retrospective cohort study in Ontario, Canada, which provides publicly funded healthcare to all residents, including services relating to prenatal and obstetrical care. The provincial birth registry (Better Outcomes Registry and Network (BORN Ontario))21 was used to identify the study population—after extracting records for completed pregnancies between 1 May and 31 December 2021, we extracted the corresponding births to create distinct records for each live birth and stillbirth, including multi-fetal pregnancies. We excluded births to non-Ontario residents and births from pregnancies conceived less than 42 weeks before the end of the study (ie, last menstrual period date after 10 March 2021) to avoid cohort truncation bias caused by overrepresentation of preterm births close to the end of the study period.22 We also excluded any records with gestational age <20 weeks and birth weight <500 g, or following pregnancy termination, as these events are not systematically collected in the registry (see supplementary table 1 for additional details of data sources).21

The birth registry receives records for all liveborn infants and stillborn infants ≥20 weeks’ gestation or with birth weight ≥500 g from hospitals, birth centres, and midwifery practice groups (home births) across Ontario.21 Maternal personal characteristics, health behaviours, pre-existing health conditions, pregnancy history, obstetric complications, interventions, and birth outcomes are collected from medical records, clinical forms, and patient interview and were shown to be of high quality in a validation study.23 Unique health card numbers (available for 96.9% of the study population) were used to deterministically link birth records to the COVaxON database, which captures all covid-19 immunisations in the province. Since 1 March 2020, information on individuals with confirmed covid-19 during pregnancy has been captured from two sources: a voluntary hospital based or midwifery practice group based case report form submitted directly to the birth registry, and through deterministic linkage with Ontario’s database containing all individuals with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) confirmed covid-19 reported to public health (Public Health Case and Contact Management Solution).24 During the study period, free PCR testing was widely available and recommended for anyone with symptoms of covid-19 or those in close contact with an individual with confirmed covid-19, or both. Finally, maternal residential postal code was used to link to area based socioeconomic data from Statistics Canada’s 2016 census and the Ontario Marginalization Index.25

Outcome measures

Exposure variables

Ontario’s covid-19 vaccination programme began on 14 December 2020,26 and pregnant individuals were designated as a priority population for vaccination on 23 April 2021.27 Owing to a limited supply of covid-19 vaccines in Canada at that time, eligibility had not yet expanded to the general adult population; moreover, for several months during the spring of 2021, Canada used an extended dose interval of up to four months between the first and second vaccine dose.28 On 18 May 2021, all people older than 18 years became eligible to receive a covid-19 vaccine, and on 15 December 2021, all people older than 18 years, including pregnant people, became eligible to receive a covid-19 booster dose.29 From COVaxON, we identified vaccinations received between the estimated date of conception up to one day before birth. We treated vaccination as a time varying exposure within outcome specific risk windows—in the main analyses of preterm birth outcomes and stillbirth, ongoing pregnancies changed status from unvaccinated to vaccinated on the day that dose 1 was received in the risk window (see supplementary fig 1). For the assessment of small for gestational age at birth, we lagged the date of dose 1 by 14 days, since any potential effect of vaccination on fetal growth would not happen acutely.16 In subgroup analyses assessing the number of doses, an additional change in exposure status occurred if dose 2 was received in the risk window. Gestational timing of all doses received during pregnancy was classified as first trimester (pregnancy day 14 to 13 weeks+6 days), second trimester (14 weeks+0 days to 27 weeks+6 days), or third trimester (28 weeks+0 days to end of follow-up). Gestational age is recorded in the birth registry, and most pregnancy dating in Ontario is based on early ultrasound assessment.

Outcome variables

We defined preterm birth and very preterm birth as a live birth before 37 and 32 completed weeks of gestation, respectively. Preterm birth subtype was considered spontaneous if it occurred after spontaneous onset of labour or preterm premature rupture of membranes.30 Small for gestational age at birth was defined as a singleton live born infant below the 10th centile of the sex specific birth weight for gestational age distribution, based on a Canadian reference standard.31 Stillbirth was defined as an antepartum or intrapartum fetal death at ≥20 weeks, with the gestational timing of the event based on the date of birth (information on the exact timing of fetal death was not available). The end of the outcome specific risk windows were 36 weeks+6 days of gestation for preterm birth (pregnancy day 258), 31 weeks+6 days for very preterm birth (pregnancy day 223), and end of pregnancy for small for gestational age infants and stillbirths.

Covariates

We adjusted for a range of covariates potentially associated with study outcomes or covid-19 vaccination, or both, using propensity score methods: maternal age at delivery (years), prepregnancy body mass index ≥30 (v <30), self-reported smoking status (yes or no) or substance use during pregnancy (yes or no), public health unit region (seven regions), pre-existing maternal health conditions (composite of asthma, chronic hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, thyroid disease; yes or no), parity (number of previous live births and stillbirths), multi-fetal pregnancy (yes or no), rural or urban residence, neighbourhood income fifths, neighbourhood marginalisation fifths (four dimensions: residential instability, material deprivation, dependency, ethnic concentration), calendar week of conception (categorical), and first visit for prenatal care in the first trimester (yes or no). Supplementary table 2 provides additional details on outcomes and covariates.

Statistical analysis

We used discrete time survival analysis to account for the time dependent nature of vaccination status and study outcomes. Each pregnancy contributed gestational time in days starting on the estimated date of conception (pregnancy day 14); ongoing pregnancies on 1 May (start of the study) started contributing time from that point (see supplementary fig 1), and follow-up continued until either the event or censoring at the end of the outcome specific risk window.

We used extended Cox proportional hazards regression models with gestational age in days as the time scale, and robust sandwich variance estimation to account for statistical dependence across repeated observations as a result of changes in vaccination status, which was treated as time varying. We estimated hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals and used inverse probability of treatment weights to generate adjusted hazard ratios.32 The weights were derived from a propensity score representing the predicted probability of having received one dose or more of a covid-19 vaccine during pregnancy—for vaccine exposed births, the weight was computed as the inverse of the propensity score, and for unexposed births, the inverse of 1 minus the propensity score. To account for any extreme weights, we stabilised the weights to the entire population and trimmed the values to the 0.01st to 99.99th centiles.32 Missing covariate values were assumed to be missing at random, and we imputed missing values before generating propensity scores using a fully conditional specification (MI procedure in SAS Version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).33 The percentage of missing data for any individual covariate included in propensity scores was low (range 0-3.5%), with the exception of body mass index, which had 10.2% missing. Across all the covariates included in the propensity scores, 15.4% of records had missing information for one or more covariates. Weighted Cox regression models from which we derived adjusted results were fitted on each of the five imputed datasets, and the results were combined using the MIANALYZE procedure (SAS Institute). As the distribution of maternal age after weighting the study population with the stabilised inverse probability of treatment weights remained imbalanced across the two exposure groups (as indicated by a standardised difference >0.134), all weighted models additionally included continuous maternal age.

In primary analyses, we evaluated vaccination status as receipt of one dose or more of a covid-19 vaccine in the outcome specific risk window. We performed subgroup analyses for preterm birth and small for gestational age at birth to evaluate trimester specific associations according to the number of doses (treating each dose as time varying), mRNA vaccine product for dose 1, and vaccine product combinations for those who received two mRNA doses; the number of events for the other outcomes was insufficient to conduct these subgroup analyses. In sensitivity analyses, we added covid-19 during pregnancy as a time varying covariate to the model and, separately, excluded individuals with a history of covid-19 during pregnancy. To assess for potential residual confounding, we stratified the original models by neighbourhood income (two highest and three lowest fifths) and limited the unvaccinated group to those who received their first vaccine dose after pregnancy, because in an earlier study of this population their baseline characteristics were shown to be more similar to individuals vaccinated during pregnancy than to those never vaccinated at any time.15 We also repeated the original analyses limited to singleton births.

Patient and public involvement

Owing to covid-19 related resource and time constraints, it was not feasible to directly involve patients in the design, conduct, reporting, or writing of our study. Although no patients were directly involved, the study team included several obstetrical care providers who were involved from the outset of planning the study and brought forward their experiences from patient interactions related to covid-19 vaccination during pregnancy. These were taken into consideration in planning this research and its dissemination to ensure relevancy for a broad group of knowledge users, including pregnant people.

Results

After exclusions, 85 162 live births and stillbirths occurred during the study period (fig 1); of these, 43 099 (50.6%) were related to individuals who received one dose or more of a covid-19 vaccine during pregnancy. Those vaccinated during pregnancy were more likely to be ≥30 years of age, nulliparous, and live in the highest income neighbourhoods; they were less likely to be smokers, report substance use during pregnancy, or live in a rural setting (table 1 and table 2). A total of 3328 births (3.9%) were to individuals who had covid-19 during pregnancy. The proportion with covid-19 during pregnancy was lower in the vaccinated group than unvaccinated group (2.9% v 4.9%; table 2). However, most of the covid-19 episodes in the vaccinated group (1056/1247; 84.6%) preceded dose 1 by a median of 10.1 weeks (interquartile range 5.3-17.6 weeks).

Fig 1.

Study flow diagram. *Includes 366 who received a dose between the last menstrual period and estimated date of conception

Table 1.

Personal characteristics of study population overall and by covid-19 vaccination status during pregnancy. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Unweighted | Stabilised inverse probability of treatment weighted | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live births and stillbirths (n=85 162)* | ≥1 vaccine dose during pregnancy (n=43 099)* | No vaccine during pregnancy (n=42 063)* | Standardised difference† | ≥1 vaccine dose during pregnancy* (%) | No vaccine during pregnancy* (%) | Standardised difference† | ||

| Maternal age (years) | ||||||||

| <25 | 6877 (8.1) | 1836 (4.3) | 5041 (12.0) | 0.29 | 6.7 | 9.0 | 0.08 | |

| 25-29 | 20 338 (23.9) | 8652 (20.1) | 11 686 (27.8) | 0.18 | 23.3 | 24.3 | 0.03 | |

| 30-34 | 34 350 (40.3) | 19 127 (44.4) | 15 223 (36.2) | 0.17 | 43.3 | 36.9 | 0.13 | |

| 35-39 | 19 405 (22.8) | 11 287 (26.2) | 8118 (19.3) | 0.16 | 22.7 | 22.9 | 0.00 | |

| ≥40 | 4192 (4.9) | 2197 (5.1) | 1995 (4.7) | 0.02 | 4.0 | 6.9 | 0.13 | |

| Mean (SD) age | 32.1 (4.9) | 32.9 (4.4) | 31.3 (5.3) | 0.05 | 32.1 (4.6) | 32.2 (5.3) | 0.01 | |

| Estimated date of conception | ||||||||

| Before Sept 2020 | 7059 (8.3) | 2376 (5.5) | 4683 (11.1) | 0.20 | 6.7 | 9.1 | 0.09 | |

| Sept-Oct 2020 | 24 396 (28.6) | 11 309 (26.2) | 13 087 (31.1) | 0.11 | 29.8 | 27.3 | 0.05 | |

| Nov-Dec 2020 | 24 470 (28.7) | 12 586 (29.2) | 11 884 (28.3) | 0.02 | 29.3 | 28.3 | 0.02 | |

| Jan-Feb 2021 | 21 922 (25.7) | 12 538 (29.1) | 9384 (22.3) | 0.16 | 26.0 | 25.7 | 0.01 | |

| After Feb 2021 | 7315 (8.6) | 4290 (10.0) | 3025 (7.2) | 0.10 | 8.3 | 9.5 | 0.04 | |

| Parity | ||||||||

| 0 (nulliparous) | 36 932 (43.4) | 19 689 (45.7) | 17 243 (41.0) | 0.09 | 43.6 | 43.7 | 0.00 | |

| ≥1 (multiparous) | 47 835 (56.2) | 23 176 (53.8) | 24 659 (58.6) | 0.10 | 56.4 | 56.3 | 0.00 | |

| Missing‡ | 395 (0.5) | 234 (0.5) | 161 (0.4) | 0.02 | ||||

| Multiple birth | ||||||||

| Yes | 2416 (2.8) | 1235 (2.9) | 1181 (2.8) | 0.00 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 0.00 | |

| No | 82 746 (97.2) | 41 864 (97.1) | 40 882 (97.2) | 0.00 | 97.2 | 97.1 | 0.00 | |

| Pre-existing medical condition§ | ||||||||

| Yes | 9474 (11.1) | 5253 (12.2) | 4221 (10.0) | 0.07 | 11.2 | 11.2 | 0.00 | |

| Thyroid disease | 5018 (5.9) | 2957 (6.9) | 2061 (4.9) | 0.08 | 6.1 | 5.8 | 0.01 | |

| Asthma | 3279 (3.9) | 1683 (3.9) | 1596 (3.8) | 0.01 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 0.01 | |

| Diabetes | 910 (1.1) | 483 (1.1) | 427 (1.0) | 0.01 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.00 | |

| Chronic hypertension | 761 (0.9) | 414 (1.0) | 347 (0.8) | 0.01 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.01 | |

| Heart disease | 100 (0.1) | 56 (0.1) | 44 (0.1) | 0.01 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.00 | |

| Smoked during pregnancy | ||||||||

| No | 78 103 (91.7) | 40 566 (94.1) | 37 537 (89.2) | 0.18 | 93.4 | 93.7 | 0.01 | |

| Yes | 5168 (6.1) | 1461 (3.4) | 3707 (8.8) | 0.23 | 6.6 | 6.3 | 0.01 | |

| Missing‡ | 1891 (2.2) | 1072 (2.5) | 819 (1.9) | 0.04 | ||||

| Substance use during pregnancy¶ | ||||||||

| No | 78 346 (92.0) | 40 282 (93.5) | 38 064 (90.5) | 0.11 | 94.7 | 94.9 | 0.01 | |

| Yes | 3958 (4.6) | 1264 (2.9) | 2694 (6.4) | 0.17 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 0.01 | |

| Missing‡ | 2858 (3.4) | 1553 (3.6) | 1305 (3.1) | 0.03 | ||||

| Prepregnancy BMI | ||||||||

| <30 | 60 358 (70.9) | 31 024 (72.0) | 29 334 (69.7) | 0.05 | 78.8 | 78.9 | 0.00 | |

| ≥30 (obese) | 16 100 (18.9) | 7972 (18.5) | 8128 (19.3) | 0.02 | 21.2 | 21.1 | 0.00 | |

| Missing‡ | 8704 (10.2) | 4103 (9.5) | 4601 (10.9) | 0.05 | ||||

| Neighbourhood median family income fifth | ||||||||

| First (lowest) | 17 118 (20.1) | 7081 (16.4) | 10 037 (23.9) | 0.19 | 20.5 | 20.3 | 0.00 | |

| Second | 17 037 (20.0) | 8144 (18.9) | 8893 (21.1) | 0.06 | 20.1 | 20.2 | 0.00 | |

| Third | 17 973 (21.1) | 9154 (21.2) | 8819 (21.0) | 0.01 | 21.2 | 21.3 | 0.00 | |

| Fourth | 17 994 (21.1) | 9989 (23.2) | 8005 (19.0) | 0.10 | 21.3 | 21.3 | 0.00 | |

| Fifth (highest) | 14 271 (16.8) | 8525 (19.8) | 5746 (13.7) | 0.16 | 16.9 | 16.9 | 0.00 | |

| Missing‡ | 769 (0.9) | 206 (0.5) | 563 (1.3) | 0.09 | ||||

| Rural residence** | ||||||||

| No | 73 112 (85.9) | 37 896 (87.9) | 35 216 (83.7) | 0.12 | 85.6 | 85.8 | 0.01 | |

| Yes | 12 050 (14.1) | 5203 (12.1) | 6847 (16.3) | 0.12 | 14.4 | 14.2 | 0.01 | |

| Public health unit region of residence | ||||||||

| Central east | 23 780 (27.9) | 11 883 (27.6) | 11 897 (28.3) | 0.02 | 28.4 | 28.4 | 0.00 | |

| Central west | 18 006 (21.1) | 8824 (20.5) | 9182 (21.8) | 0.03 | 21.2 | 21.3 | 0.00 | |

| Greater Toronto region | 16 620 (19.5) | 9508 (22.1) | 7112 (16.9) | 0.13 | 19.6 | 19.7 | 0.00 | |

| Eastern | 11 224 (13.2) | 6347 (14.7) | 4877 (11.6) | 0.09 | 13.2 | 13.2 | 0.00 | |

| South west | 10 494 (12.3) | 4478 (10.4) | 6016 (14.3) | 0.12 | 12.2 | 12.3 | 0.00 | |

| North east | 2889 (3.4) | 1229 (2.9) | 1660 (3.9) | 0.06 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 0.00 | |

| North west | 1390 (1.6) | 631 (1.5) | 759 (1.8) | 0.03 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 0.01 | |

| Missing‡ | 759 (0.9) | 199 (0.5) | 560 (1.3) | 0.09 | ||||

| Residential instability fifth | ||||||||

| First (least) | 17 007 (20.0) | 8818 (20.5) | 8189 (19.5) | 0.02 | 20.1 | 20.2 | 0.00 | |

| Second | 15 810 (18.6) | 8181 (19.0) | 7629 (18.1) | 0.02 | 18.8 | 18.8 | 0.00 | |

| Third | 16 032 (18.8) | 8167 (18.9) | 7865 (18.7) | 0.01 | 19.1 | 19.1 | 0.00 | |

| Fourth | 15 528 (18.2) | 7713 (17.9) | 7815 (18.6) | 0.02 | 18.6 | 18.5 | 0.00 | |

| Fifth (most) | 19 286 (22.6) | 9743 (22.6) | 9543 (22.7) | 0.00 | 23.4 | 23.4 | 0.00 | |

| Missing‡ | 1499 (1.8) | 477 (1.1) | 1022 (2.4) | 0.10 | ||||

| Material deprivation fifth | ||||||||

| First (least) | 19 351 (22.7) | 11 855 (27.5) | 7496 (17.8) | 0.23 | 23.0 | 23.1 | 0.00 | |

| Second | 17 132 (20.1) | 9481 (22.0) | 7651 (18.2) | 0.10 | 20.3 | 20.4 | 0.00 | |

| Third | 15 461 (18.2) | 7776 (18.0) | 7685 (18.3) | 0.01 | 18.3 | 18.3 | 0.00 | |

| Fourth | 15 279 (17.9) | 7145 (16.6) | 8134 (19.3) | 0.07 | 18.3 | 18.2 | 0.00 | |

| Fifth (most) | 16 440 (19.3) | 6365 (14.8) | 10 075 (24.0) | 0.23 | 20.1 | 20.0 | 0.00 | |

| Missing‡ | 1499 (1.8) | 477 (1.1) | 1022 (2.4) | 0.10 | ||||

| Dependency fifth | ||||||||

| First (least) | 27 572 (32.4) | 14 761 (34.2) | 12 811 (30.5) | 0.08 | 32.8 | 32.8 | 0.00 | |

| Second | 17 547 (20.6) | 8958 (20.8) | 8589 (20.4) | 0.01 | 20.8 | 20.9 | 0.00 | |

| Third | 14 076 (16.5) | 7104 (16.5) | 6972 (16.6) | 0.00 | 16.9 | 16.9 | 0.00 | |

| Fourth | 12 749 (15.0) | 6211 (14.4) | 6538 (15.5) | 0.03 | 15.2 | 15.2 | 0.00 | |

| Fifth (most) | 11 719 (13.8) | 5588 (13.0) | 6131 (14.6) | 0.05 | 14.3 | 14.2 | 0.00 | |

| Missing‡ | 1499 (1.8) | 477 (1.1) | 1022 (2.4) | 0.10 | ||||

| Ethnic concentration fifth | ||||||||

| First (lowest) | 11 634 (13.7) | 5357 (12.4) | 6277 (14.9) | 0.07 | 14.4 | 14.2 | 0.01 | |

| Second | 13 640 (16.0) | 6878 (16.0) | 6762 (16.1) | 0.00 | 16.3 | 16.3 | 0.00 | |

| Third | 15 114 (17.7) | 8251 (19.1) | 6863 (16.3) | 0.07 | 17.8 | 17.9 | 0.00 | |

| Fourth | 18 378 (21.6) | 9898 (23.0) | 8480 (20.2) | 0.07 | 21.8 | 21.9 | 0.00 | |

| Fifth (highest) | 24 897 (29.2) | 12 238 (28.4) | 12 659 (30.1) | 0.04 | 29.6 | 29.7 | 0.00 | |

| Missing‡ | 1499 (1.8) | 477 (1.1) | 1022 (2.4) | 0.10 | ||||

BMI=body mass index; SD=standard deviation.

Column percentages in the weighted study population were based on imputation dataset 1.

Absolute standardised difference comparing those who received one dose or more of a covid-19 vaccine during pregnancy and those who were not vaccinated during pregnancy; standardised difference >0.10 indicates an imbalance in the distribution of the baseline characteristic between these two vaccination groups.

Missing data are not shown in the weighted study population as multiple imputation was used before deriving inverse probability of treatment weights.

Composite of asthma, chronic hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, thyroid disease. Sum of individual conditions does not equal the total number of individuals with any individual condition, as categories were not mutually exclusive.

Self-reported cannabis, opioid, or alcohol use during pregnancy.

Because of small cell counts (<6) for missing values in the vaccinated group, missing has been combined with the “no” category.

Table 2.

Pregnancy characteristics of study population overall and by covid-19 vaccination status during pregnancy. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Unweighted | Stabilised inverse probability of treatment weighted | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live births and stillbirths (n=85 162)* | ≥ 1 vaccine dose during pregnancy (n=43 099)* | No vaccine during pregnancy (n=42 063)* | Standardised difference† | ≥1 vaccine dose during pregnancy * (%) | No vaccine during pregnancy * (%) | Standardised difference† | ||

| Covid-19 during pregnancy‡ | ||||||||

| Yes | 3328 (3.9) | 1247 (2.9) | 2081 (4.9) | 0.11 | 3.1 | 4.8 | 0.09 | |

| No | 81 834 (96.1) | 41 852 (97.1) | 39 982 (95.1) | 0.11 | 96.9 | 95.2 | 0.09 | |

| First prenatal care visit in first trimester | ||||||||

| Yes | 77 440 (90.9) | 39 623 (91.9) | 37 817 (89.9) | 0.07 | 94.1 | 94.2 | 0.00 | |

| No | 4755 (5.6) | 1852 (4.3) | 2903 (6.9) | 0.11 | 5.9 | 5.8 | 0.00 | |

| Missing§ | 2967 (3.5) | 1624 (3.8) | 1343 (3.2) | 0.03 | ||||

| Birth location | ||||||||

| Home | 2460 (2.9) | 845 (2.0) | 1615 (3.8) | 0.11 | 2.0 | 3.7 | 0.10 | |

| Hospital | 82 103 (96.4) | 41 994 (97.4) | 40 109 (95.4) | 0.11 | 97.4 | 95.5 | 0.10 | |

| Birth centre | 382 (0.4) | 197 (0.5) | 185 (0.4) | 0.00 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.02 | |

| Clinic (midwifery) | 153 (0.2) | 44 (0.1) | 109 (0.3) | 0.04 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.02 | |

| Other Ontario location | 64 (0.1) | 19 (0.0) | 45 (0.1) | 0.02 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.01 | |

| Healthcare provider | ||||||||

| Midwives | 9892 (11.6) | 4499 (10.4) | 5393 (12.8) | 0.07 | 10.4 | 12.7 | 0.07 | |

| CNS, NP, registered nurse | 590 (0.7) | 240 (0.6) | 350 (0.8) | 0.03 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.02 | |

| Family doctor | 4939 (5.8) | 2547 (5.9) | 2392 (5.7) | 0.01 | 6.5 | 5.3 | 0.05 | |

| Obstetrician | 61 534 (72.3) | 31 399 (72.9) | 30 135 (71.6) | 0.03 | 72.7 | 72.7 | 0.00 | |

| Other healthcare provider, resident, surgeon | 7422 (8.7) | 4023 (9.3) | 3399 (8.1) | 0.04 | 9.5 | 8.2 | 0.05 | |

| Unattended | 263 (0.3) | 85 (0.2) | 178 (0.4) | 0.04 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.03 | |

| Missing§ | 522 (0.6) | 306 (0.7) | 216 (0.5) | 0.03 | ||||

CNS=clinical nurse specialist; NP=nurse practitioner.

Column percentages in the weighted study population were based on imputation dataset 1.

Absolute standardised difference comparing those who received one dose or more of a covid-19 vaccine during pregnancy and those who were not vaccinated during pregnancy; standardised difference >0.10 indicates an imbalance in the distribution of the baseline characteristic between these two vaccination groups.

Laboratory confirmed covid-19 between estimated date of conception up to one day before date of birth (the specimen collection date, which was a proxy for date of infection, was lagged by two days).

Missing data are not shown in the weighted study population as multiple imputation was used before deriving inverse probability of treatment weights.

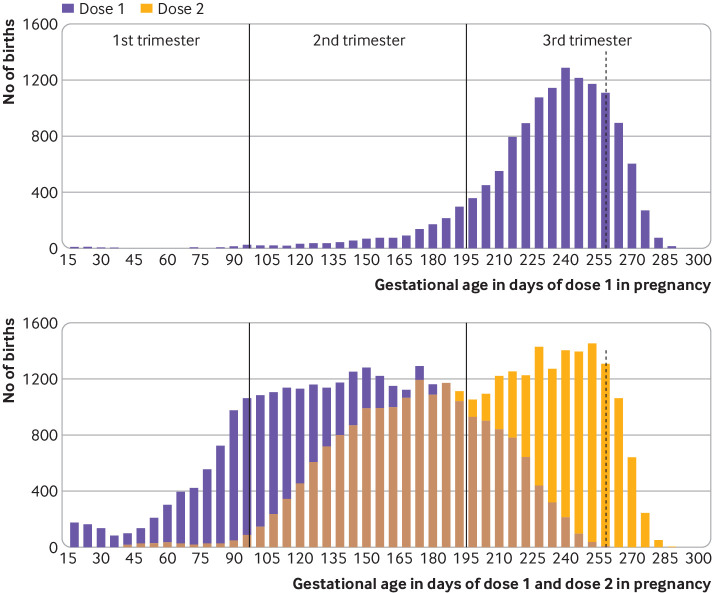

Among 43 099 individuals who were vaccinated during pregnancy, 13 416 (31.1%) received one vaccine dose, 29 650 (68.8%) received two doses, and 33 (0.1%) received three doses (table 3). Overall, 12.1% (n=5213) received dose 1 during the first trimester, 48.1% (n=20 715) during the second trimester, and 39.8% (n=17 171) during the third trimester. The median gestational age at dose 1 was 25 (interquartile range 18-32) weeks—later, when only one dose was received during pregnancy (median 34 (interquartile range 31-36) weeks; n=13 416) and earlier when two doses were received during pregnancy (median 21 (interquartile range 16-26) weeks; n=29 650) (fig 2). Overall, 80.1% (n=34 526) of dose 1 administrations during pregnancy were BNT162b2 (Comirnaty; Pfizer-BioNTech) and 19.6% (n=8453) were mRNA-1273 (Spikevax; Moderna); <1% (0.3%; n=120) were another vaccine product (Vaxzevria; Oxford-AstraZeneca: n=101; other: n=19).

Table 3.

Vaccination characteristics among 43 099 pregnant individuals who received one dose or more of a covid-19 vaccine during pregnancy. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | ≥1 vaccine dose during pregnancy (n=43 099) |

|---|---|

| No of doses received during pregnancy | |

| One dose | 13 416 (31.1) |

| Two doses | 29 650 (68.8) |

| Three doses | 33 (0.1) |

| No of doses received during and/or after pregnancy | |

| One dose during pregnancy | 422 (1.0) |

| One dose during, one dose after, pregnancy | 5555 (12.9) |

| One dose during, two doses after, pregnancy | 7439 (17.3) |

| Two doses during pregnancy | 9646 (22.4) |

| Two doses during, one dose after, pregnancy | 20 004 (46.4) |

| Three doses during pregnancy | 33 (0.1) |

| Trimester of vaccine dose 1 (overall) | |

| First | 5213 (12.1) |

| Second | 20 715 (48.1) |

| Third | 17 171 (39.8) |

| Median (IQR) gestational age (days) | 176 (126-222) |

| Median (IQR) gestational age (weeks) | 25.1 (18.0-31.7) |

| Trimester of vaccine dose 1 (only one dose during pregnancy; n=13 416): | |

| First | 93 (0.7) |

| Second | 1409 (10.5) |

| Third | 11 914 (88.8) |

| Median (IQR) gestational age (days) | 237 (217-253) |

| Median (IQR) gestational age (weeks) | 33.9 (31.0-36.1) |

| Trimester of vaccine dose 1 (only two doses during pregnancy; (n=29 650): | |

| First | 5091 (17.2) |

| Second | 19 302 (65.1) |

| Third | 5257 (17.7) |

| Median (IQR) gestational age (days) | 147 (110-184) |

| Median (IQR) gestational age (weeks) | 21.1 (15.7-26.3) |

| Trimester of vaccine dose 2 (only two doses during pregnancy; n=29 650) | |

| First | 301 (1.0) |

| Second | 13 019 (43.9) |

| Third | 16 330 (55.1) |

| Median (IQR) gestational age (days) | 204 (165-239) |

| Median (IQR) gestational age (weeks) | 29.1 (23.6-34.1) |

| Vaccine product received for dose 1 | |

| BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) | 34 526 (80.1) |

| mRNA-1273 (Moderna) | 8453 (19.6) |

| Other* | 120 (0.3) |

| Vaccine product for those who received two doses of mRNA vaccine during pregnancy (n=29 574) | |

| BNT162b2+BNT162b2† | 19 866 (67.2) |

| mRNA-1273+mRNA-1273† | 5321 (18.0) |

| BNT162b2+mRNA-1273 or mRNA-1273+BNT162b2‡ | 4387 (14.8) |

IQR=interquartile range.

Includes non-mRNA covid-19 vaccines (eg, manufactured by Oxford-AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson-Janssen).

Same type of mRNA vaccine for doses 1 and 2 (homologous mRNA series).

Different type of mRNA vaccine for doses 1 and 2 (heterologous mRNA series).

Fig 2.

Gestational timing of covid-19 vaccine doses received during pregnancy among 43 099 pregnant individuals in Ontario, Canada. (Top panel) Gestational age in days when dose 1 was received, among births to individuals who received only one vaccine dose during pregnancy (n=13 416). (Bottom panel) Gestational age in days when dose 1 and dose 2 were received, among births to individuals who received only two doses during pregnancy (n=29 650). Data for individuals who received three doses during pregnancy (n=33) are not shown. Vertical dotted line represents the end of the risk window for preterm birth (pregnancy day 258)

Overall, 5719 (6.7%) preterm births occurred; 3450 (4.1%) were spontaneous preterm births (table 4). The cumulative incidence of overall preterm birth was 6.5% among those who were vaccinated during pregnancy and 6.9% among those who were unvaccinated during pregnancy. Vaccination was not associated with an increased risk of overall preterm birth (adjusted hazard ratio 1.02, 95% confidence interval 0.96 to 1.08), spontaneous preterm birth (0.96, 0.90 to 1.03), or very preterm birth (0.80, 0.67 to 0.95). In subgroup analyses, results for overall preterm birth were similar by trimester (adjusted hazard ratios: first trimester, 0.98, 95% confidence interval 0.87 to 1.10; second trimester 0.98, 0.91 to 1.04; third trimester 1.00, 0.92 to 1.08) and vaccine product for dose 1, as well as by number of doses received during pregnancy, and vaccine product combination for those who received both doses during pregnancy (see supplementary table 3). Subgroup analyses could not be conducted for spontaneous preterm birth or very preterm birth owing to the small number of events.

Table 4.

Association between covid-19 vaccination during pregnancy and study outcomes

| Outcomes | No vaccine during pregnancy (n=42 063) | ≥1 vaccine dose during pregnancy* (n=43 099) |

|---|---|---|

| Preterm birth <37 weeks† | ||

| No of participants | 41 879 | 42 992 |

| No (%) with outcome (rate/100 live births) | 2907 (6.9) | 2812 (6.5) |

| No of pregnancy days at risk‡ | 4 304 319 | 3 410 735 |

| Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.92 to 1.02) |

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.02 (0.96 to 1.08) |

| Spontaneous preterm birth <37 week†§ | ||

| No of participants | 41 879 | 42 992 |

| No (%) with outcome (rate/100 live births) | 1842 (4.4) | 1608 (3.7) |

| No of pregnancy days at risk‡ | 4 304 319 | 3 410 735 |

| Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.88 (0.82 to 0.94) |

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.96 (0.90 to 1.03) |

| Very preterm birth <32 weeks† | ||

| No of participants | 41 879 | 42 992 |

| No (%) with outcome (rate/100 live births) | 374 (0.89) | 252 (0.59) |

| No of pregnancy days at risk‡ | 3 081 508 | 2 190 543 |

| Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.79 (0.67 to 0.93) |

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.80 (0.67 to 0.95) |

| Small for gestational age at birth¶ | ||

| No of participants | 40 280 | 41 333 |

| No (%) with outcome (rate/100 singleton live births) | 3722 (9.2) | 3743 (9.1) |

| No of pregnancy days at risk‡ | 4 783 558 | 3 953 597 |

| Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.96 (0.91 to 1.00) |

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.03) |

| Stillbirth | ||

| No of participants | 42 063 | 43 099 |

| No (%) with outcome (rate/100 live births and stillbirths) | 184 (0.44) | 107 (0.25) |

| No of pregnancy days at risk‡ | 4 994 562 | 4 111 719 |

| Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.65 (0.51 to 0.82) |

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.65 (0.51 to 0.84) |

CI=confidence interval.

Vaccination was treated as a time varying exposure within outcome specific risk windows. Hazard ratios were adjusted using stabilised inverse probability of treatment weights, trimmed at 0.01st and 99.99th centiles. In addition to weights, maternal age (as a continuous variable) was added to the adjusted models as it remained imbalanced between the two groups after weighting.

Among live births only.

Number of days at risk in risk window. Preterm birth: 36 weeks+6 days of gestation (pregnancy day 258); very preterm birth: 31 weeks+6 days of gestation (pregnancy day 223); small for gestational age at birth and stillbirth: end of pregnancy. Since vaccination status was treated as a time varying variable, vaccinated individuals could have contributed both exposed and unexposed days at risk.

For spontaneous preterm birth, medically initiated preterm births were censored at delivery.

Among singleton live births only. A total of 885 records were excluded from the analysis (34 records had a gestational age either below or above the values provided in the reference standard used to classify small for gestational age at birth, and 851 records had missing information on infant sex or birth weight, or both).

The cumulative incidence of small for gestational age at birth was 9.1% (n=3743) among births to individuals who received one dose or more of a covid-19 vaccine during pregnancy, and 9.2% (n=3722) among births to unvaccinated individuals. No association was observed between vaccination during pregnancy and small for gestational age at birth overall (adjusted hazard ratio 0.98, 0.93 to 1.03; table 4), or in subgroup analyses by trimester and vaccine product for dose 1 (see supplementary table 3). A small increased association was observed for only dose 1 administered during pregnancy (1.09, 1.01 to 1.16), which was not observed among individuals who received two doses during pregnancy (0.92, 0.87 to 0.97; see supplementary table 3). The cumulative incidence of stillbirth was 0.25% (n=107) among births to individuals who received one dose or more of a covid-19 vaccine during pregnancy, and 0.44% (n=184) among births to unvaccinated individuals. Vaccination was not associated with any increase in the risk of stillbirth (0.65, 0.51 to 0.84; table 4). The number of stillbirths was not large enough for subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analyses

When covid-19 during pregnancy was added to the model as a time varying exposure and when births to individuals with covid-19 during pregnancy were excluded, the results remained unchanged for all outcomes (see supplementary table 4). Estimates for most outcomes were similar across strata of neighbourhood income; although stratum specific estimates for individuals of higher income (fourth and fifth fifths) and lower income (first to third fifths) were different in magnitude for very preterm birth and for stillbirth, the direction of the stratum specific point estimates was consistent with that of the main analyses, and confidence intervals overlapped. When the comparison group was restricted to unvaccinated individuals who initiated their covid-19 vaccine series after pregnancy, the results for all outcomes remained unchanged. Analyses restricted to singleton births were similar for preterm birth outcomes; however, the estimate for stillbirth moved closer to the null value (adjusted hazard ratio 0.74, 0.57 to 0.96).

Discussion

In this large population of more than 85 000 live births and stillbirths up to 31 December 2021, we found no evidence that vaccination during pregnancy with an mRNA covid-19 vaccine was associated with a higher risk of preterm birth, spontaneous preterm birth, very preterm birth, small for gestational age at birth, or stillbirth. These results—based on more than 43 000 fetuses exposed to at least one dose of mRNA covid-19 vaccine—did not differ by trimester of vaccination, number of doses received during pregnancy, or mRNA vaccine product.

Comparison with other studies

Our findings for preterm birth and small for gestational age at birth are consistent with a recent Scandinavian birth registry based study of 157 521 births (103 409 from Sweden and 54 112 from Norway) to 12 January 2022, in which 18% of the births (n=28 506) were to individuals who were vaccinated during pregnancy.16 The adjusted estimates pooled across Sweden and Norway were consistent in magnitude and direction with our results for preterm birth (adjusted hazard ratio 0.98, 95% confidence interval 0.91 to 1.05) and small for gestational age at birth (0.97, 0.90 to 1.04).16 A US Vaccine Safety Datalink study of 46 079 singleton live births to 22 July 2021 (21.8% (n=10 064) of individuals received a covid-19 vaccine during pregnancy) reported adjusted hazard ratios for preterm birth (0.91, 95% confidence interval 0.82 to 1.01) and small for gestational age at birth (0.95, 0.87 to 1.03) that were similar to our estimates.17 An Israeli cohort study of 24 288 singleton live births to 30 September 2021 (68.7% (n=16 697) individuals received BNT162b2 during pregnancy)18 reported no increased risk of preterm birth (adjusted risk ratio 0.95, 95% confidence interval 0.83 to 1.10) or small for gestational age at birth (0.97, 0.87 to 1.08), and no differences in risk of infants being admitted to hospital or mortality up to 7 months of age.18 The Scandinavian study16 and the Vaccine Safety Datalink study17 both used a similar methodology as our study—treating vaccination during pregnancy as a time varying exposure—as has been recommended.19 Similar to our results, neither of these two studies16 17 observed any patterns of concern when outcomes were assessed by number of vaccine doses, mRNA vaccine product, or trimester of vaccination.

We observed a reduction in stillbirth risk among vaccinated individuals (adjusted hazard ratio 0.65, 95% confidence interval 0.51 to 0.84), even after adjustment for a range of potential confounders through propensity score weighting. A reduced risk of stillbirth was also observed in the Scandinavian study, although the estimate was smaller in magnitude (pooled adjusted hazard ratio 0.86, 95% confidence interval 0.63 to 1.17).16 Collectively, the findings from these two studies are reassuring and are consistent with no increased risk of stillbirth after covid-19 vaccination during pregnancy. In contrast, covid-19 disease during pregnancy has been associated with an increased risk of stillbirth.6 Although fetal viraemia from SARS-CoV-2 transmission across the placenta is considered uncommon, it is biologically plausible that vaccination could protect against stillbirth through preventing SARS-CoV-2-associated placental damage35 or other immunological responses to clinical or subclinical infection. Nevertheless, we did not observe any difference in our findings in sensitivity analyses adjusting for confirmed covid-19 during pregnancy or after excluding individuals with covid-19 during pregnancy, suggesting it is unlikely to fully account for the suggested protective benefit of vaccination during pregnancy. Residual confounding by unmeasured characteristics or temporal issues could also have biased the estimate away from the null value.19 22 Interestingly, a reduced stillbirth risk after influenza vaccination during pregnancy was also reported in some large cohort studies of 2009 pandemic A/H1N1 monovalent influenza vaccines and seasonal trivalent influenza vaccines—adjusted risk estimates for stillbirth ranged from 0.44 to 0.88 and several were statistically significant.36 Similar to influenza vaccination,37 vaccine derived maternal antibodies are known to cross the placenta after covid-19 vaccination during pregnancy,38 and emerging evidence supports protective benefits to newborns from covid-19 in the early months of life.9 10

Strengths and limitations of this study

Strengths of this study include the large birth population and number of individuals vaccinated during pregnancy. We used deterministically linked population based data sources within a publicly funded healthcare system; thus, identification of births and vaccinations was highly complete and minimised potential selection or exposure misclassification bias. As gestational age at birth is mostly based on early ultrasound assessment in Ontario, the accuracy of classifying gestational timing of vaccination was probably high. Although we adjusted for many potential confounders using a propensity score based approach, we cannot dismiss the possibility of residual confounding, particularly given the potential for healthy vaccinee bias in observational studies of vaccination.19 Moreover, despite using recommended methodological approaches for handling time dependent exposures and pregnancy outcomes,19 22 we cannot rule out residual temporal confounding, particularly given the complex temporal dynamics of the pandemic and vaccination programme. We used a comprehensive strategy to identify cases of covid-19 during pregnancy, including the province-wide public health database for polymerase chain reaction confirmed covid-19; however, individuals who did not seek testing could be misclassified as not having had covid-19 during pregnancy. Pregnancies ending before 20 weeks’ gestation are not systematically captured in the birth registry and could not be evaluated; however, previous high quality case-control studies did not find any evidence of an increased risk of miscarriage associated with covid-19 vaccination during early pregnancy.13 14 Despite the large sample size, our study might have been underpowered to rule out small associations for some rarer outcomes. During the study period, the proportion of vaccines administered in the first trimester was relatively low (12.1%). Moreover, we were unable to assess covid-19 vaccination before pregnancy or around the time of conception, as the time period covered by our study did not include sufficient numbers of these early vaccinations; evaluation of outcomes after vaccination in these time windows is planned for in future studies. We were unable to evaluate booster doses because pregnant Ontario residents were not eligible until December 2021, and most of these pregnancies are ongoing. Finally, we were limited to assessment of mRNA vaccine products, as use of other covid-19 vaccine types in the pregnant population in Canada has been limited.

Conclusions

We did not find evidence of an increased risk of preterm birth, small for gestational age at birth, or stillbirth after covid-19 vaccination during any trimester of pregnancy in this large population based study including more than 43 000 births to individuals vaccinated during pregnancy. Our findings—along with extant evidence that vaccination during pregnancy is effective against covid-19 for pregnant individuals and their newborns, and that covid-19 during pregnancy is associated with increased risks of adverse maternal, fetal, and neonatal outcomes—can inform evidence based decision making about covid-19 vaccination during pregnancy. Future studies to assess similar outcomes after immunisation with non-mRNA covid-19 vaccine types during pregnancy should be a research priority.

What is already known on this topic

SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy is associated with adverse maternal and birth outcomes

Pregnancy specific safety information about covid-19 vaccination is important for pregnant individuals, healthcare providers, and policy makers to guide decision making

Evidence from large comparative studies about pregnancy outcomes after covid-19 vaccination during pregnancy is limited

What this study adds

No association was found between immunisation with an mRNA covid-19 vaccine during pregnancy and increased risk of preterm birth, spontaneous preterm birth, very preterm birth, small for gestational age at birth, or stillbirth

These findings can help inform evidence based decision making about the risks and benefits of covid-19 vaccination during pregnancy

Acknowledgments

We thank the Ontario Ministry of Health for granting access to the COVaxON database and the Public Health Case and Contact Management Solution; the maternal-newborn hospitals and midwifery practice groups in Ontario for providing maternal-newborn data to Better Outcomes Registry and Network (BORN Ontario); and BORN Ontario staff for their assistance with data extraction, linkage, code review, and results review.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Supplementary information: additional tables 1-4

Contributors: DBF, JCK, AES, DE-C, and SDD conceived the study. DBF, AKR, GDA, LO, CAG, and SEH developed the study design and analytical approach, in consultation with other project team members. GDA, TD, SD-C, and DBF linked the data sources. SD-C performed the statistical analyses, which were supervised by DBF. DBF drafted the initial version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings and reviewed and edited the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. DBF is the guarantor. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This study was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada through the Vaccine Surveillance Reference Group and the COVID-19 Immunity Task Force. SEH and LO were partly funded by the Norwegian Research Council (No 324312 and No 262700). The study sponsors did not participate in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by BORN Ontario and the Ontario Ministry of Health; however, the analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at https://www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare: support from the Public Health Agency of Canada through the Vaccine Surveillance Reference Group and the COVID-19 Immunity Task Force; SEH and LO were partly funded by the Norwegian Research Council. KW is chief executive officer of CANImmunize, which hosts a national digital immunisation record, and is a member of the independent data safety board for the Medicago covid-19 vaccine trial. There are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

The corresponding author (DBF) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as originally planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: All personal identifying information of study participants has been removed from the dataset; thus it is not possible to send the results of this study to participants. Given the rules under which the data are used for research purposes, individuals to whom the data relate are not permitted to be contacted. However, as part of a detailed knowledge translation plan, several provincial and national organisations have been engaged to assist with dissemination of the findings of this study to their diverse networks of public health units and practitioners, care providers, policy makers, and other stakeholders, including patients and the general public. The results of this study have also been shared with the public through provincial webinars and social media channels.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario research ethics board.

Data availability statement

The dataset from this study is held securely by BORN Ontario. Although the dataset cannot be made publicly available, the analytical code may be available on request.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Precautions for people with certain medical conditions. Accessed 24 June 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html.

- 2. Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, et al. for PregCOV-19 Living Systematic Review Consortium . Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020;370:m3320. 10.1136/bmj.m3320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Villar J, Ariff S, Gunier RB, et al. Maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality among pregnant women with and without COVID-19 infection: The INTERCOVID Multinational Cohort Study. JAMA Pediatr 2021;175:817-26. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Regan AK, Arah OA, Fell DB, Sullivan SG. SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy and associated perinatal health outcomes: a national US cohort study. J Infect Dis 2022;225:759-67. 10.1093/infdis/jiab626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Karasek D, Baer RJ, McLemore MR, et al. The association of COVID-19 infection in pregnancy with preterm birth: A retrospective cohort study in California. Lancet Reg Health Am 2021;2:100027. 10.1016/j.lana.2021.100027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. DeSisto CL, Wallace B, Simeone RM, et al. Risk for stillbirth among women with and without COVID-19 at delivery hospitalization - United States, March 2020-September 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:1640-5. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7047e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berman Institute of Bioethics & Center for Immunization Research, Johns Hopkins University. COVID-19 Maternal Immunization Tracker (COMIT): COVID-19 Vaccine policies for pregnant and lactating people worldwide. Published 2021. Accessed 24 June 2022. www.comitglobal.org.

- 8. Dagan N, Barda N, Biron-Shental T, et al. Effectiveness of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in pregnancy. Nat Med 2021;27:1693-5. 10.1038/s41591-021-01490-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Halasa NB, Olson SM, Staat MA, et al. Overcoming COVID-19 Investigators. Overcoming COVID-19 Network . Effectiveness of maternal vaccination with mRNA COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy against COVID-19-associated hospitalization in infants aged <6 months - 17 States, July 2021-January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:264-70. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7107e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carlsen EØ, Magnus MC, Oakley L, et al. Association of COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy with incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in infants. JAMA Intern Med 2022; published online 1 June. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Razzaghi H, Meghani M, Pingali C, et al. COVID-19 vaccination coverage among pregnant women during pregnancy - Eight integrated health care organizations, United States, December 14, 2020-May 8, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:895-9. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7024e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stock SJ, Carruthers J, Calvert C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination rates in pregnant women in Scotland. Nat Med 2022;28:504-12. 10.1038/s41591-021-01666-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Magnus MC, Gjessing HK, Eide HN, Wilcox AJ, Fell DB, Håberg SE. Covid-19 vaccination during pregnancy and first-trimester miscarriage. N Engl J Med 2021;385:2008-10. 10.1056/NEJMc2114466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kharbanda EO, Haapala J, DeSilva M, et al. Spontaneous abortion following COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy. JAMA 2021;326:1629-31. 10.1001/jama.2021.15494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fell DB, Dhinsa T, Alton GD, et al. Association of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy with adverse peripartum outcomes. JAMA 2022;327:1478-87. 10.1001/jama.2022.4255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Magnus MC, Örtqvist AK, Dahlqwist E, et al. Association of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination during pregnancy with pregnancy outcomes. JAMA 2022;327:1469-77. 10.1001/jama.2022.3271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lipkind HS, Vazquez-Benitez G, DeSilva M, et al. Receipt of COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy and preterm or small-for-gestational-age at birth - Eight integrated health care organizations, United States, December 15, 2020-July 22, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:26-30. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7101e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goldshtein I, Steinberg DM, Kuint J, et al. Association of BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy with neonatal and early infant outcomes. JAMA Pediatr 2022;176:470-7. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fell DB, Dimitris MC, Hutcheon JA, et al. Guidance for design and analysis of observational studies of fetal and newborn outcomes following COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy. Vaccine 2021;39:1882-6. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.02.070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, STROBE Initiative . Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007;335:806-8. 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Murphy MSQ, Fell DB, Sprague AE, et al. Data Resource Profile: Better Outcomes Registry & Network (BORN) Ontario. Int J Epidemiol 2021;50:1416-7h. 10.1093/ije/dyab033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Neophytou AM, Kioumourtzoglou M-A, Goin DE, Darwin KC, Casey JA. Educational note: addressing special cases of bias that frequently occur in perinatal epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 2021;50:337-45. 10.1093/ije/dyaa252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dunn S, Lanes A, Sprague AE, et al. Data accuracy in the Ontario birth Registry: a chart re-abstraction study. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19:1001. 10.1186/s12913-019-4825-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ontario Ministry of Health. Protecting Ontarians through enhanced case and contact management. Accessed 24 June 2022. https://www.ontario.ca/page/case-and-contact-management-strategy.

- 25.Public Health Ontario. Ontario Marginalization Index (ON-Marg). Accessed 24 June 2022. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/data-and-analysis/health-equity/ontario-marginalization-index.

- 26.Ontario Ministry of Health. Ontario’s COVID-19 vaccination plan. Accessed 24 June 2022. https://covid-19.ontario.ca/ontarios-covid-19-vaccination-plan#our-three-phased-vaccination-plan.

- 27.Ontario Ministry of Health. COVID-19: Guidance for prioritization of phase 2 populations for COVID-19 vaccination. Accessed 24 June 2022. https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/coronavirus/docs/vaccine/COVID-19_Phase_2_vaccination_prioritization.pdf.

- 28.National Advisory Committee on Immunization. Extended dose intervals for COVID-19 vaccines to optimize early vaccine rollout and population protection in Canada in the context of limited vaccine supply. Accessed 24 June 2022. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/immunization/national-advisory-committee-on-immunization-naci/extended-dose-intervals-covid-19-vaccines-early-rollout-population-protection.html.

- 29.Ontario Ministry of Health. All Ontarians 18+ eligible for COVID-19 booster appointments at three-month interval. Accessed 24 June 2022. https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/1001352/all-ontarians-18-eligible-for-covid-19-booster-appointments-at-three-month-interval.

- 30. Bhattacharjee E, Maitra A. Spontaneous preterm birth: the underpinnings in the maternal and fetal genomes. NPJ Genom Med 2021;6:43. 10.1038/s41525-021-00209-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kramer MS, Platt RW, Wen SW, et al. Fetal/Infant Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System . A new and improved population-based Canadian reference for birth weight for gestational age. Pediatrics 2001;108:E35. 10.1542/peds.108.2.e35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med 2015;34:3661-79. 10.1002/sim.6607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ 2009;338:b2393. 10.1136/bmj.b2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med 2009;28:3083-107. 10.1002/sim.3697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schwartz DA, Avvad-Portari E, Babál P, et al. Placental tissue destruction and insufficiency from COVID-19 causes stillbirth and neonatal death from hypoxic-ischemic injury. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2022;146:660-76. 10.5858/arpa.2022-0029-SA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Giles ML, Krishnaswamy S, Macartney K, Cheng A. The safety of inactivated influenza vaccines in pregnancy for birth outcomes: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2019;15:687-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Regan AK, Munoz FM. Efficacy and safety of influenza vaccination during pregnancy: realizing the potential of maternal influenza immunization. Expert Rev Vaccines 2021;20:649-60. 10.1080/14760584.2021.1915138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shook LL, Atyeo CG, Yonker LM, et al. Durability of anti-spike antibodies in infants after maternal COVID-19 vaccination or natural infection. JAMA 2022;327:1087-9. 10.1001/jama.2022.1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information: additional tables 1-4

Data Availability Statement

The dataset from this study is held securely by BORN Ontario. Although the dataset cannot be made publicly available, the analytical code may be available on request.