Abstract

Objectives

This systematic review aimed to assess in vitro studies that evaluated neutrophil interactions with different roughness levels in titanium and zirconia implant surfaces.

Material and Methods

An electronic search for literature was conducted on PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science and a total of 14 studies were included. Neutrophil responses were assessed based on adhesion, cell number, surface coverage, cell structure, cytokine secretion, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, neutrophil activation, receptor expression, and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) release. The method of assessing the risk of bias was done using the toxicological data reliability assessment tool (TOXRTOOL).

Results

Ten studies have identified a significant increase in neutrophil functions, such as surface coverage, cell adhesion, ROS production, and NETs released when interacting with rough titanium surfaces. Moreover, neutrophil interaction with rough–hydrophilic surfaces seems to produce less proinflammatory cytokines and ROS when compared to naive smooth and rough titanium surfaces. Regarding membrane receptor expression, two studies have reported that the FcγIII receptor (CD16) is responsible for initial neutrophil adhesion to hydrophilic titanium surfaces. Only one study compared neutrophil interaction with titanium alloy and zirconia toughened alumina surfaces and reported no significant differences in neutrophil cell count, activation, receptor expression, and death.

Conclusions

There are not enough studies to conclude neutrophil interactions with titanium and zirconia surfaces. However, different topographic modifications such as roughness and hydrophilicity might influence neutrophil interactions with titanium implant surfaces.

Keywords: neutrophils, systematic review, titanium, zirconia

1. INTRODUCTION

Ever since the ground‐breaking work of Brånemark in the 1960s, different metals and their alloys have been used as dental implants due to their excellent biocompatibility, mechanical strength, and aesthetics (Brånemark et al., 1969). When an implant is inserted into the bone, an initial inflammatory response is triggered by the immune cells of myeloid origin predominated by neutrophils (Kolaczkowska & Kubes, 2013; Segal, 2005). Neutrophils, the critical cellular player, activate an inflammatory cascade by producing cytokines, enzymes, and DNA fiber networks called neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) (Brinkmann et al., 2004; Nauseef, 2016). The presumed neutrophil response to a dental implant is determined by several physical and chemical features of the implant surfaces, which include mechanical and physicochemical properties such as chemical composition, surface wettability, surface energy, and surface topography (Bowers et al., 1992; Galli et al., 2005; Ong et al., 1996).

Improvements in osteointegration have been achieved by introducing micro and nano roughness on the implant surfaces (Goené et al., 2007; Grandfield et al., 2013; Jarmar et al., 2008). Titanium implant surfaces were classified according to the degree of roughness into four categories: smooth (Sa = 0.0–0.4 µm), minimally rough (Sa = 0.5–1.0 µm), moderately rough (Sa = 1.0–2.0 µm), and rough (Sa > 2.0 µm) (Wennerberg & Albrektsson, 2009). Based on this classification, studies have demonstrated stronger/increased adhesion of neutrophils on rough titanium implant surfaces than on smooth Ti surfaces (Campos et al., 2014; Vitkov et al., 2015). Studies have also identified different neutrophil morphology and NETotic responses to titanium surfaces with various roughness fields (Abaricia et al., 2020; Vitkov et al., 2015). Furthermore, researchers have investigated neutrophil interaction with implant surfaces having a combination of roughness/hydrophilicity, which may promote quicker healing time and reduced initial inflammatory response (Abaricia et al., 2020; El Kholy et al., 2020).

Zirconia is considered a potential alternative to titanium implants due to its aesthetics, excellent biocompatibility, mechanical properties, and reduced bacterial biofilm formation (Christel et al., 1989; Langhoff et al., 2008; Piconi & Maccauro, 1999). However, due to its high hardness, surface roughening of zirconia has been technically challenging (Rottmar et al., 2019). Different surface topographies of zirconia were reported to increase osteoblast proliferation on a rough surface compared to a smooth surface (Bächle et al., 2007). A recent study showed a significantly increased cellular spreading and migration rate on rough zirconia surfaces (Sa = 3.36 μm) than on the rough titanium implant surfaces (Munro et al., 2020). From these studies mentioned above, it is assumed that the functional activity of neutrophils is determined by the implant surface characteristics raising questions regarding the exact nature of such interactions. Therefore, this systematic review aimed to assess in vitro studies that evaluated neutrophil interactions with different roughness levels in titanium and zirconia implant surfaces.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The reporting of this review complies with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines (Moher et al., 2009, 2012). The PRISMA checklist is presented in Supporting Information Materials S1 and S2. Ethics approval was not required for this systematic review.

2.1. Literature search strategy

Two independent reviewers (G. E. and J. M. M.‐N.) conducted an electronic search done up to April 2021, using Medical Subject Headings, keywords, and other accessible terms on PubMed. The search strategy was adapted to other electronic databases, including Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science. Appropriate Boolean operators (OR, AND) were used to refine the searches. The search strategy used in PubMed was: (titanium OR zirconia) AND (neutrophils OR phagocyte OR neutrophils OR leukocyte OR granulocyte). No date or language limitations were placed during the search. The search strategy of the other databases is presented in Supporting Information Material S3.

All the retrieved titles and abstracts were exported to a referencing software program (EndNote X9, Philadelphia, Clarivate). Any duplicates found were deleted. Two reviewers (G. E. and J. M. M.‐N.) screened all the titles and abstracts independently; those that seemed suitable were considered for inclusion in the full‐text review. When the information provided in the abstract and title were inadequate to determine eligibility, articles were reviewed in full. Disagreement between reviewers (G. E. and J. M. M.‐N.) was resolved through discussion. A third reviewer (C. M. S. F.) was consulted when an agreement was not reached.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria were based on the PICO (population, intervention, control, and outcomes) questions: How do neutrophils interact with titanium and zirconia surfaces? Studies conducted in vitro investigated peripheral neutrophils (leukocytes, polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells, granulocytes) on titanium and zirconia surfaces with or without surface topography modifications and articles in English. Studies were excluded in vivo and ex vivo investigating titanium nanoparticles, coated implant surfaces, and abstract studies.

2.3. Data extraction

Relevant data were extracted by two reviewers (G. E. and J. M. M.‐N.) independently. Authors were contacted if any missing data or additional data were required from the eligible studies. The following data items were extracted from the eligible studies: author (year); type of biomaterials used in the test and comparison groups; experimental design (methods); primary outcomes (results) related to neutrophils morphology, NETs release, cytokine secretion, neutrophils adhesion, neutrophils receptor expression, ROS production and phagocytosis ability of neutrophils on titanium and zirconia surfaces. A narrative synthesis of the findings from the included studies is presented based on neutrophil response to roughness, hydrophilicity, cytokine expression, morphology, NETosis, and receptor expression (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Author and year | Material/surface modification | Cells | Methods | Main finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abaricia et al. (2020) | Ti | Neutrophils isolated from murine blood | Surface analysis; flow cytometry; coculture; SEM and CLSM; ELISA; qPCR |

|

| ||||

| Radley et al. (2019) | Highly polished | Human peripheral blood | Flow cytometry; ELISA; phagocytosis; ROS assay; rheometry | The application of shear stress to blood on Ti alloy surfaces leads to neutrophil activation indicated by reduced l‐selectin expression. |

| ||||

| Radley et al. (2018) |

Highly polished diamond‐like carbon‐coated stainless steel |

Human peripheral blood | Flow cytometry; ELISA |

|

| ||||

| Vitkov et al. (2015) | Ti | Human peripheral blood |

SEM; CLSM; immunocytochemistry |

|

| ||||

| Campos et al. (2014) | Ti | Neutrophils isolated from human blood |

SEM; flowcytometry; AFM |

|

| ||||

| Smith et al. (2013) | Titania nanotube and Ti surfaces | Human peripheral blood | AFM; MTT assay; ELISA |

|

| Arvidsson et al. (2011) | Ti blasted with Al2O3 | Human peripheral blood | Respiratory burst; SEM |

|

| ||||

| Schildhauer et al. (2009) |

|

Human peripheral blood | ELISA; SEM; chemotaxis, flow cytometry |

|

| Erikkson et al. (2001) | Ti sheets | Human peripheral blood |

Immunofluorescence; chemiluminescence activity |

|

| Erikkson et al. (2001) | Ti sheets | Human peripheral blood |

Chemiluminescence; immunofluorescence; cell number |

The present study results indicate that PMNLs recognize hydrophilic and hydrophobic Ti surfaces by different adhesion receptors and show different patterns of receptor expression. |

| Erikkson et al. (2001) | Ti sheets | Human peripheral blood |

Surface analysis; viability staining; chemiluminescence; immunofluorescence |

|

| ||||

| Nygren et al. (1997) | Ti sheets | Human peripheral blood |

Optical profilometry; SEM; Auger electron spectroscopy; X‐ray photoelectron; spectroscopy; immunofluorescence |

|

| ||||

| Wilke et al. (1998) |

|

Human bone marrow cells | SEM; flow cytometry, fluorescence microscopy | –12.2 ± 2.4% of granulocytes (CD15‐positive cells) adhered to naive Ti surfaces. |

Abbreviations: AFM, atomic force microscopy; CLSM, confocal laser scanning microscopy; ELISA, enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay; MPO, myeloperoxidase; NET, neutrophil extracellular trap; PMNL, polymorphonuclear leukocyte; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; SEM, scanning electron microscopy; TNF‐α, tumor necrosis factor‐α.

2.4. Risk of bias in the included studies

The method of assessing the risk of bias was done using the toxicological data reliability assessment tool (TOXRTOOL) (Schneider et al., 2009). For in vitro studies, it uses a set of 18 questions or criteria. For each criterion, a score of “1” is provided when the response is “yes,” or the criteria are addressed, while a score of “0” is given when the response is “no,” that is, when the criteria are not addressed in the study. If the value is ≥15, Category 1 is assigned. For values >11, Category 2 is assigned, and for all values <11, Category 3 is assigned. Categories 1 and 2 represent that the data is reliable without and with restriction, respectively, while Category 3 indicates that the data reported from the study is unreliable.

3. RESULTS

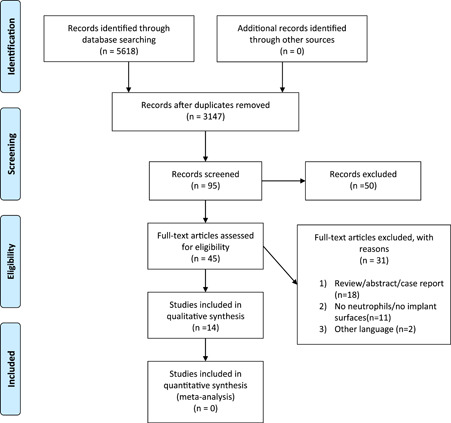

The electronic search of the databases identified a total of 3147 papers: PubMed (n = 1110), Embase (n = 1090), Scopus (n = 666), and Web of Science (n = 281). After eliminating the duplicates and screening the titles and abstracts, 45 full texts were reviewed (Figure 1). Finally, 14 articles were included in the qualitative analysis. Table S1 depicts the studies excluded after full‐text review. The κ‐statistic for agreement on including full‐text articles between the reviewers was 1.0, indicating no disagreement. Table 1 represents the general characteristics of the selected studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the online databases searched and selection of studies for inclusion.

3.1. Background characteristics of the included studies

Among the 14 selected studies, 10 articles compared neutrophils interactions with titanium surfaces of different roughness levels. Four articles compared neutrophil behaviors in titanium surfaces with other biomaterial surfaces used for medical implants, and among these, only one study compared neutrophil behavior between titanium and zirconia surfaces. All included studies assessed responses of peripheral neutrophils on titanium and zirconia surfaces (Abaricia et al., 2020; Arvidsson et al., 2011; Campos et al., 2014; El Kholy et al., 2020; Eriksson & Nygren, 2001a, 2001b; Eriksson et al., 2001; Nygren et al., 1997; Radley et al., 2018, 2019; Schildhauer et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2013; Vitkov et al., 2015; Wilke et al., 1998). Neutrophil responsiveness, morphological changes, and adhesion were evaluated about roughness in 10 studies. Different methods, such as 5 studies—enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay, 9—scanning electron microscopy (SEM), 6—flowcytometry, 6—immunofluorescence staining, 5—chemiluminescence assay, 2—atomic force microscopy and 3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyl tetrazolium bromide assay, 2—confocal laser scanning microscopy, were used to evaluate the role of cellular immune response and morphological changes on titanium and zirconia surfaces. Analysis of the geographic distribution revealed that five studies were carried out in Sweden (Arvidsson et al., 2011; Eriksson & Nygren, 2001a, 2001b; Eriksson et al., 2001; Nygren et al., 1997), three studies were carried out in the United States (Abaricia et al., 2020; El Kholy et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2013), two studies each in United Kingdom and Germany (Radley et al., 2018, 2019; Schildhauer et al., 2009; Wilke et al., 1998) and one study in Brazil (Campos et al., 2014). Five studies used neutrophils directly isolated from the blood, eight used whole blood (leukocytes/granulocytes/PMN), and one used human bone marrow cells (granulocytes). Table 1 summarizes the studies that evaluated immunological response, morphological changes, activation, and adhesion of neutrophils during interaction with titanium and zirconia implant surfaces.

3.2. Risk of bias

In this review, 12 studies were found to have an overall score of ≥15 (Category 1), demonstrating that data from these studies are reliable without restrictions. One study had a score of 14 and belonged to Category 2, and one study had a score of 11 and belonged to Category 3. The scoring for all studies is shown in Table S2 and Figure S1 shows the number of studies belonging to the respective categories.

3.3. Results from the individual studies

3.3.1. Neutrophil behavior based on roughness

Ten studies assessed the interaction of neutrophils with titanium surfaces based on their roughness. One study identified intact cellular morphology and reduced chemiluminescence activity (respiratory burst) by neutrophils when interacting with serum coated moderately rough hydrophilic titanium surfaces compared to moderately rough hydrophobic titanium surfaces (El Kholy et al., 2020). A second study identified neutrophils interacting with rough hydrophilic titanium surfaces to produce low levels of interleukin‐1β (IL‐1β), IL‐6, IL‐12, tumor necrosis factor‐α, IL, neutrophils elastase, and myeloperoxidase with no NETs formation compared to neutrophils interacting with naive smooth and rough titanium surfaces (Abaricia et al., 2020). However, activated neutrophils on smooth titanium and alloy surfaces released relatively low IL‐ra and IL‐8 fields (Schildhauer et al., 2009). Additionally, rapid neutrophil adhesion (80%–82%) and various stages of NETosis with completely spread NETs with swollen nuclei and chromatin alteration on SLA (Sandblasted, Large grit, Acid‐etched) titanium surfaces were observed. (Vitkov et al., 2015). In another study, neutrophils exposed to rough titanium surfaces had a fourfold higher surface attachment area showing a prominent shape and more cytoplasmic projections after 2 h compared to smooth titanium surfaces (Campos et al., 2014). However, CD11b and l‐selectin expression in neutrophils were not influenced by titanium surface textures (Campos et al., 2014). Two studies also reported increased neutrophils adhesion, priming, ROS production and expression of CD 11b on rough titanium surfaces compared to smooth titanium surfaces (Eriksson et al., 2001; Nygren et al., 1997). Significant production of ROS occurred earlier on smooth titanium surfaces compared to rough titanium surfaces (Eriksson et al., 2001). No statistically significant differences in neutrophil cell count and production of ROS were observed on blasted Ti surfaces compared to other coated Ti surfaces (Arvidsson et al., 2011). Short‐ and long‐term exposure of neutrophils to rough titanium surfaces showed increased adhesion and proliferation compared to nanostructural surfaces (Smith et al., 2013). Only one study investigated biocompatibility parameters of human bone marrow cells and reported that 12.2% of granulocytes adhered to naive titanium surfaces (Wilke et al., 1998). Based on these results, increased neutrophil adhesion, ROS production, and different stages of NETosis were observed on rough titanium surfaces. However, rough hydrophilic titanium surfaces seem to induce decreased levels of proinflammatory cytokines and ROS production and showed no NET formation from neutrophils.

3.3.2. Neutrophil behavior based on receptor expression

Eriksson and Nygren (2001b) investigated neutrophil functions based on adhesion receptors on hydrophilic and hydrophobic titanium surfaces. Eriksson and Nygren (2001a) found that neutrophils adhered to hydrophilic titanium surfaces in a FcγIII receptor (CD16). Expression of the FcγIII receptor on neutrophils was dominant during the initial hours, which gradually shifted towards CD11b expression later. Eriksson and Nygren (2001b) reported that neutrophil activation increased over time on hydrophilic titanium surfaces, which was evident from the decreased expression of CD62L. Additionally, the CD16 expression was higher during the initial hours at hydrophilic surfaces but only peaked after late hours at hydrophobic surfaces (Eriksson & Nygren, 2001b). The same study showed that neutrophils adhesion to hydrophilic and hydrophobic titanium surfaces was depressed by inhibiting hirudin (thrombin inhibition), reporting the expression of CD16 and CD11b to be thrombin dependent (Eriksson & Nygren, 2001b). A recent study also identified a significant reduction in l‐selectin (CD62L) expression on titanium alloy surfaces by applying sheave r force, indicating an increased neutrophils activation compared to other highly polished medical implant surfaces such as stainless steel and sapphire crystal (Radley et al., 2019). These studies indicate that different adhesion receptors recognize hydrophilic and hydrophobic titanium surfaces. Moreover, the activation and adhesion were increased in hydrophilic surfaces compared to hydrophobic surfaces.

3.3.3. Neutrophil interaction with titanium and zirconia implant surfaces

Only one study compared neutrophils interaction between titanium alloy and zirconia toughened alumina surfaces (Radley et al., 2018). The neutrophils count was not significantly different between titanium and zirconia surfaces, and the neutrophil expression of CD62L did not differ between these surfaces.

4. DISCUSSION

This systematic review indicated that neutrophils functions, such as adhesion, surface coverage, attachment, and NET release, are influenced by topographic modifications on titanium surfaces. It has been demonstrated that a rapid surface coverage and stronger neutrophil adhesion can be seen on rough titanium surfaces compared to smooth titanium surfaces (Campos et al., 2014; Eriksson et al., 2001; Vitkov et al., 2015). Additionally, SEM analysis has shown different morphological features of neutrophils, such as flat cells, cytoplasmic projections, and surface attachment on rough titanium surfaces (Campos et al., 2014). Like neutrophils, macrophage adhesion, morphology, and phenotype can be modulated by implant surface roughness (Chen et al., 2010; Geiger et al., 2009; Soskolne et al., 2002). Also, previous studies have shown increased osteoblast adhesion on rough titanium surfaces compared to smooth one's Fields (Bowers et al., 1992; Michaels et al., 1991). Additionally, studies have shown that osteoblast morphology can vary between rough and smooth titanium surfaces (Bowers et al., 1992; Boyan et al., 2003). Therefore, early biological events such as cell behavior and functions seem to be influenced by surface roughness.

Neutrophils seem to produce low levels of proinflammatory cytokines and enzymes and high anti‐inflammatory cytokines when interacting with rough hydrophilic Ti surfaces (Abaricia et al., 2020). Likewise, studies on macrophages also showed low levels of proinflammatory cytokines in response to micro‐rough hydrophilic titanium surfaces (Alfarsi et al., 2014; Hamlet et al., 2012). Studies on osteoblast have also found that increased hydrophilic surfaces improved osteogenic differentiation (Olivares‐Navarrete et al., 2011; Vlacic‐Zischke et al., 2011). In addition, micro‐rough hydrophilic surfaces seem to be positively involved in the earlier onset of the osseointegration (Lang et al., 2011). These findings suggest that surface hydrophilicity seems to attenuate the production of proinflammatory cytokines and may promote faster wound healing. (Vitkov et al., 2015) showed that rough Ti surfaces triggered the NET release and histone citrullination. In contrast, Abaricia et al. (2020) demonstrated no NET formation on rough hydrophilic Ti surfaces compared to naive rough and smooth Ti surfaces. Neutrophils are generally known to release NETs upon activation by microbes, often dependent on ROS generation (Kolaczkowska & Kubes, 2013). However, studies have shown NET formation even under sterile conditions (Abaricia et al., 2020; Vitkov et al., 2015). Therefore, it is plausible to believe that implant surface roughness/chemistry can affect the NETotic response.

It has been shown that neutrophils interaction with rough Ti surfaces can induce ROS to release (Eriksson et al., 2001; El Kholy et al., 2020), which might lead to local tissue damage, delayed wound healing and even loosening of implants (Hwang et al., 2019; Segal, 2005). Studies have also reported that Ti ions released from implant surfaces trigger macrophages and osteoblast to produce increased ROS levels (Vermes et al., 2001; Żukowski et al., 2018). It is believed that hydrophilic surfaces can downregulate neutrophil activation, causing a decrease in ROS production (El Kholy et al., 2020). Thus, the initial inflammatory response by neutrophils seems to be altered by combining surface topography/hydrophilicity.

Our findings must be interpreted with caution. First, only one study compared neutrophils interaction between titanium alloy and alumina toughened zirconia implant surfaces showing no significant difference. Second, only in vitro studies were assessed. Thus, further clinical and in vivo studies are needed to confirm the relevance of in vitro findings. Finally, the lack of homogeneous quantitative data for meta‐analysis and methodological heterogeneity to assess the interaction/behavior of neutrophils can also be a drawback of the present systematic review.

5. CONCLUSION

There are not enough studies to draw any conclusion about neutrophil interactions with titanium and zirconia surfaces. However, different topographic modifications such as roughness and hydrophilicity might influence neutrophil interactions with titanium implant surfaces.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Carlos Marcelo S. Figueredo. Methodology: Gayathiri Elangovan, Joao M. Mello‐Neto, Santosh K. Tadakamadla, and Carlos Marcelo S. Figueredo. Validation: Gayathiri Elangovan and Joao M. Mello‐Neto. Formal analysis: Gayathiri Elangovan and Joao M. Mello‐Neto. Investigation: Gayathiri Elangovan and Joao M. Mello‐Neto. Resources: Gayathiri Elangovan and Joao M. Mello‐Neto. Data curation: Gayathiri Elangovan and Joao M. Mello‐Neto. Writing—original draft preparation: Gayathiri Elangovan and Joao M. Mello‐Neto. Writing, review, and editing: Carlos Marcelo S. Figueredo, Gayathiri Elangovan, Joao M. Mello‐Neto, Peter Reher, and Santosh K. Tadakamadla. Visualization: Carlos Marcelo S. Figueredo, Gayathiri Elangovan, Joao M. Mello‐Neto, Peter Reher, and Santosh K. Tadakamadla. Supervision: Carlos Marcelo S. Figueredo. Project administration: Carlos Marcelo S. Figueredo. Funding acquisition: Not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Santosh Kumar Tadakamadla is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship, Australia. This study received no external funding.

Elangovan, G. , Mello‐Neto, J. M. , Tadakamadla, S. K. , Reher, P. , & Figueredo, C. M. S. (2022). A systematic review on neutrophils interactions with titanium and zirconia surfaces: Evidence from in vitro studies. Clinical and Experimental Dental Research, 8, 950–958. 10.1002/cre2.582

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable—no new data was generated, or the article describes entirely theoretical research.

REFERENCES

- Abaricia, J. O. , Shah, A. H. , Musselman, R. M. , & Olivares‐Navarrete, R. (2020). Hydrophilic titanium surfaces reduce neutrophil inflammatory response and NETosis. Biomaterials Science, 8(8), 2289–2299. 10.1039/c9bm01474h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfarsi, M. A. , Hamlet, S. M. , & Ivanovski, S. (2014). Titanium surface hydrophilicity modulates the human macrophage inflammatory cytokine response. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 102(1), 60–67. 10.1002/jbm.a.34666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsson, A. , Malmberg, P. , Kjellin, P. , Currie, F. , Arvidsson, M. , & Stenport, V. F. (2011). Early interactions between leukocytes and three different potentially bioactive titanium surface modifications. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B‐Applied Biomaterials, 97B(2), 364–372. 10.1002/jbm.b.31823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bächle, M. , Butz, F. , Hübner, U. , Bakalinis, E. , & Kohal, R. J. (2007). The behaviour of CAL72 osteoblast‐like cells cultured on zirconia ceramics with different surface topographies. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 18(1), 53–59. 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2006.01292.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, K. T. , Keller, J. C. , Randolph, B. A. , Wick, D. G. , & Michaels, C. M. (1992). Optimization of surface micromorphology for enhanced osteoblast responses in vitro. The International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants, 7(3), 302–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyan, B. D. , Lossdörfer, S. , Wang, L. , Zhao, G. , Lohmann, C. H. , Cochran, D. L. , & Schwartz, Z. (2003). Osteoblasts generate an osteogenic microenvironment when grown on surfaces with rough microtopographies. European Cells & Materials, 6, 22–27. 10.22203/ECM.v006a03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brånemark, P. I. , Adell, R. , Breine, U. , Hansson, B. O. , Lindström, J. , & Ohlsson, A. (1969). Intra‐osseous anchorage of dental prostheses. I. Experimental studies. Scandinavian Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 3(2), 81–100. 10.3109/02844316909036699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann, V. , Reichard, U. , Goosmann, C. , Fauler, B. , Uhlemann, Y. , Weiss, D. S. , Weinrauch, Y. , & Zychlinsky, A. (2004). Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science, 303(5663), 1532–1535. 10.1126/science.1092385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos, V. , Melo, R. C. N. , Silva, L. P. , Aquino, E. N. , Castro, M. S. , & Fontes, W. (2014). Characterization of neutrophil adhesion to different titanium surfaces. Bulletin of Materials Science, 37(1), 157–166. 10.1007/s12034-014-0611-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S. , Jones, J. A. , Xu, Y. , Low, H. Y. , Anderson, J. M. , & Leong, K. W. (2010). Characterization of topographical effects on macrophage behaviour in a foreign body response model. Biomaterials, 31(13), 3479–3491. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christel, P. , Meunier, A. , Heller, M. , Torre, J. P. , & Peille, C. N. (1989). Mechanical properties and short‐term in‐vivo evaluation of yttrium‐oxide‐partially‐stabilized zirconia. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research, 23(1), 45–61. 10.1002/jbm.820230105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Kholy, K. , Buser, D. , Wittneben, J. G. , Bosshardt, D. D. , Van Dyke, T. E. , & Kowolik, M. J. (2020). Investigating the response of human neutrophils to hydrophilic and hydrophobic micro‐rough titanium surfaces. Materials (Basel), 13(15). 10.3390/ma13153421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, C. , Lausmaa, J. , & Nygren, H. (2001). Interactions between human whole blood and modified TiO2‐surfaces: Influence of surface topography and oxide thickness on leukocyte adhesion and activation. Biomaterials, 22(14), 1987–1996. 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00382-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, C. , & Nygren, H. (2001a). Adhesion receptors of polymorphonuclear granulocytes on titanium in contact with whole blood. Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine, 137(1), 56–63. 10.1067/mlc.2001.111470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, C. , & Nygren, H. (2001b). Polymorphonuclear leukocytes in coagulating whole blood recognize hydrophilic and hydrophobic titanium surfaces by different adhesion receptors and show different patterns of receptor expression. Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine, 137(4), 296–302. 10.1067/mlc.2001.114066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli, C. , Guizzardi, S. , Passeri, G. , Martini, D. , Tinti, A. , Mauro, G. , & Macaluso, G. M. (2005). Comparison of human mandibular osteoblasts grown on two commercially available titanium implant surfaces. Journal of Periodontology, 76(3), 364–372. 10.1902/jop.2005.76.3.364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, B. , Spatz, J. P. , & Bershadsky, A. D. (2009). Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 10(1), 21–33. 10.1038/nrm2593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goené, R. J. , Testori, T. , & Trisi, P. (2007). Influence of a nanometer‐scale surface enhancement on de novo bone formation on titanium implants: a histomorphometric study in human maxillae. The International Journal of Periodontics and Restorative Dentistry, 27(3), 211–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandfield, K. , Gustafsson, S. , & Palmquist, A. (2013). Where bone meets implant: The characterization of nano‐osseointegration. Nanoscale, 5(10), 4302–4308. 10.1039/c3nr00826f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlet, S. , Alfarsi, M. , George, R. , & Ivanovski, S. (2012). The effect of hydrophilic titanium surface modification on macrophage inflammatory cytokine gene expression. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 23(5), 584–590. 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2011.02325.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J. H. , Ma, J. N. , Park, J. H. , Jung, H. W. , & Park, Y. K. (2019). Anti‐inflammatory and antioxidant effects of MOK, a polyherbal extract, on lipopolysaccharide‑stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. International Journal of Molecular Medicine, 43(1), 26–36. 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarmar, T. , Palmquist, A. , Brånemark, R. , Hermansson, L. , Engqvist, H. , & Thomsen, P. (2008). Characterization of the surface properties of commercially available dental implants using scanning electron microscopy, focused ion beam, and high‐resolution transmission electron microscopy. Clinical Implant Dentistry and Related Research, 10(1), 11–22. 10.1111/j.1708-8208.2007.00056.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolaczkowska, E. , & Kubes, P. (2013). Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nature Reviews Immunology, 13(3), 159–175. 10.1038/nri3399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang, N. P. , Salvi, G. E. , Huynh‐Ba, G. , Ivanovski, S. , Donos, N. , & Bosshardt, D. D. (2011). Early osseointegration to hydrophilic and hydrophobic implant surfaces in humans. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 22(4), 349–356. 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2011.02172.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhoff, J. D. , Voelter, K. , Scharnweber, D. , Schnabelrauch, M. , Schlottig, F. , Hefti, T. , Kalchofner, K. , Nuss, K. , & von Rechenberg, B. (2008). Comparison of chemically and pharmaceutically modified titanium and zirconia implant surfaces in dentistry: A study in sheep. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 37(12), 1125–1132. 10.1016/j.ijom.2008.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels, C. M. , Keller, J. C. , & Stanford, C. M. (1991). In vitro periodontal ligament fibroblast attachment to plasma‐cleaned titanium surfaces. The Journal of Oral Implantology, 17(2), 132–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D. , Hopewell, S. , Schulz, K. F. , Montori, V. , Gøtzsche, P. C. , Devereaux, P. J. , Elbourne, D. , Egger, M. , & Altman, D. G. (2012). CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. International Journal of Surgery (London, England), 10(1), 28–55. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D. , Liberati, A. , Tetzlaff, J. , & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro, T. , Miller, C. M. , Antunes, E. , & Sharma, D. (2020). Interactions of osteoprogenitor cells with a novel zirconia implant surface. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 11(3). 10.3390/jfb11030050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauseef, W. M. (2016). Neutrophils, from cradle to grave and beyond. Immunological Reviews, 273(1), 5–10. 10.1111/imr.12463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygren, H. , Eriksson, C. , & Lausmaa, J. (1997). Adhesion and activation of platelets and polymorphonuclear granulocyte cells at TiO2 surfaces. Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine, 129(1), 35–46. 10.1016/s0022-2143(97)90159-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivares‐Navarrete, R. , Hyzy, S. L. , Park, J. H. , Dunn, G. R. , Haithcock, D. A. , Wasilewski, C. E. , Boyan, B. D. , & Schwartz, Z. (2011). Mediation of osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells on titanium surfaces by a Wnt‐integrin feedback loop. Biomaterials, 32(27), 6399–6411. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.05.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong, J. L. , Prince, C. W. , Raikar, G. N. , & Lucas, L. C. (1996). Effect of surface topography of titanium on surface chemistry and cellular response. Implant Dentistry, 5(2), 83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piconi, C. , & Maccauro, G. (1999). Zirconia as a ceramic biomaterial. Biomaterials, 20(1), 1–25. 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00010-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radley, G. , Pieper, I. L. , Thomas, B. R. , Hawkins, K. , & Thornton, C. A. (2019). Artificial shear stress effects on leukocytes at a biomaterial interface. Artificial Organs, 43(7), E139–e151. 10.1111/aor.13409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radley, G. , Pieper, I. L. , & Thornton, C. A. (2018). The effect of ventricular assist device‐associated biomaterials on human blood leukocytes. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B—Applied biomaterials, 106(5), 1730–1738. 10.1002/jbm.b.33981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottmar, M. , Müller, E. , Guimond‐Lischer, S. , Stephan, M. , Berner, S. , & Maniura‐Weber, K. (2019). Assessing the osteogenic potential of zirconia and titanium surfaces with an advanced in vitro model. Dental Materials, 35(1), 74–86. 10.1016/j.dental.2018.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schildhauer, T. A. , Peter, E. , Muhr, G. , & Koller, M. (2009). Activation of human leukocytes on tantalum trabecular metal in comparison to commonly used orthopedic metal implant materials. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 88(2), 332–341. 10.1002/jbm.a.31850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, K. , Schwarz, M. , Burkholder, I. , Kopp‐Schneider, A. , Edler, L. , Kinsner‐Ovaskainen, A. , Hartung, T. , & Hoffmann, S. (2009). “ToxRTool”, a new tool to assess the reliability of toxicological data. Toxicology Letters, 189(2), 138–144. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal, A. W. (2005). How neutrophils kill microbes. Annual Review of Immunology, 23, 197–223. 10.1146/annurev.Immunol.23.021704.115653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B. S. , Capellato, P. , Kelley, S. , Gonzalez‐Juarrero, M. , & Popat, K. C. (2013). Reduced in vitro immune response on titania nanotube arrays compared to titanium surface. Biomaterials Science, 1(3), 322–332. 10.1039/c2bm00079b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soskolne, W. A. , Cohen, S. , Shapira, L. , Sennerby, L. , & Wennerberg, A. (2002). The effect of titanium surface roughness on the adhesion of monocytes and their secretion of TNF‐α and PGE2. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 13(1), 86–93. 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2002.130111.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermes, C. , Chandrasekaran, R. , Jacobs, J. J. , Galante, J. O. , Roebuck, K. A. , & Glant, T. T. (2001). The effects of particulate wear debris, cytokines, and growth factors on the functions of MG‐63 osteoblasts. JBJS, 83(2), 201–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitkov, L. , Krautgartner, W. D. , Obermayer, A. , Stoiber, W. , Hannig, M. , Klappacher, M. , & Hartl, D. (2015). The initial inflammatory response to bioactive implants is characterized by NETosis. PLoS One, 10(3), e0121359. 10.1371/journal.pone.0121359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlacic‐Zischke, J. , Hamlet, S. M. , Friis, T. , Tonetti, M. S. , & Ivanovski, S. (2011). The influence of surface microroughness and hydrophilicity of titanium on the up‐regulation of TGFβ/BMP signalling in osteoblasts. Biomaterials, 32(3), 665–671. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennerberg, A. , & Albrektsson, T. (2009). Effects of titanium surface topography on bone integration: A systematic review. Clinical Oral Implants Research, 20(Suppl 4), 172–184. 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01775.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke, A. , Orth, J. , Lomb, M. , Fuhrmann, R. , Kienapfel, H. , Griss, P. , & Franke, R. P. (1998). Biocompatibility analysis of different biomaterials in human bone marrow cell cultures. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research, 40(2), 301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Żukowski, P. , Maciejczyk, M. , & Waszkiel, D. (2018). Sources of free radicals and oxidative stress in the oral cavity. Archives of Oral Biology, 92, 8–17. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2018.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Supporting information.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable—no new data was generated, or the article describes entirely theoretical research.