Abstract

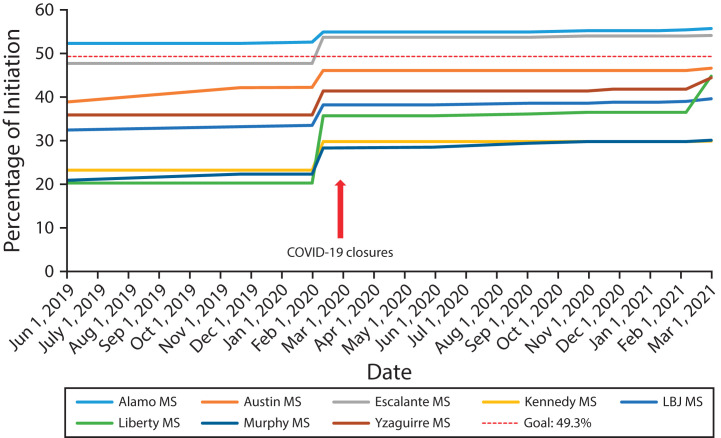

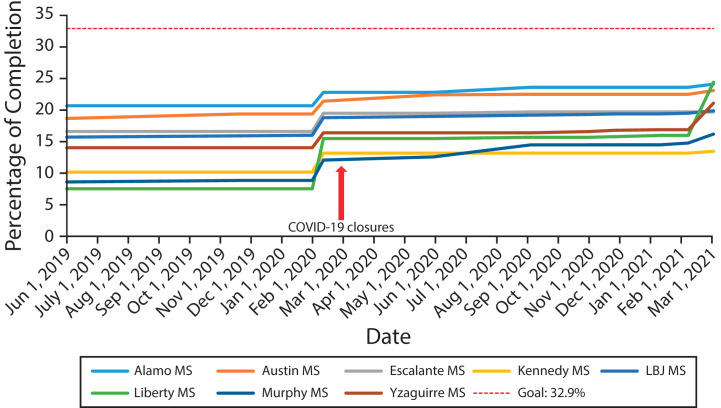

This quasi-experimental study (a community-based, physician-led human papillomavirus [HPV] education campaign and school-based vaccination program) followed 6481 students at eight Pharr–San Juan–Alamo Independent School District (Rio Grande Valley, Texas) middle schools between August 2016 and March 2021. We describe the successes and challenges experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. HPV vaccine initiation and completion rates increased 1.29-fold and 1.47-fold, respectively, between June 2019 and March 2021. Between March 2020 and March 2021, 268 HPV vaccine doses were provided through 24 school-based interventions. Our program continued successes seen in increasing HPV vaccination rates and reducing possible HPV-associated cancers. (Am J Public Health. 2022;112(9):1269–1272. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.306970)

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccinations have proven to be a valuable, cost-effective public health intervention for reducing HPV-associated cancers. 1 The ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic has affected health service delivery, causing dramatic drops in annual well visits, cancer screenings, and immunizations (e.g., a 19.3% decrease in HPV vaccinations). 2 – 4 With population-wide lockdowns implemented to reduce outbreaks (closing schools, businesses, and clinics and halting mass gatherings), these disruptions have caused indirect health effects and threatened progress in HPV vaccinations, thus possibly increasing preventable HPV-related diseases and cancers. The objectives of the intervention described here were to increase HPV vaccination rates among medically underserved, economically disadvantaged students in a rural middle school district (Rio Grande Valley [RGV], TX) and assess COVID-19 pandemic adaptations to a community-based education and school-based HPV vaccination program.

The intervention combined community-based HPV education with school-based vaccinations in the Pharr–San Juan–Alamo Independent School District (PSJA ISD). 5 The educational component, involving physician-led educational events in Cameron, Hidalgo, and Starr counties (located in a 15-mile radius encompassing that of the original intervention, which took place in the Rio Grande City Independent School District [RGC ISD])), started in August 2016, and the PSJA ISD school-based vaccination program began in June 2019. 5

INTERVENTION AND IMPLEMENTATION

From June 2019 to March 2021, a quasi-experimental design was used to implement the school-based vaccination component in the PSJA ISD (starting with the schools with the largest enrollments and in the closest proximity to the RGC ISD: August 2019 for phase 1 [three middle schools], August 2020 for phase 2 [three middle schools], and February 2021 for phase 3 [two middle schools]). 5 HPV vaccine series were initiated and completed during the school year at back-to-school events, progress report nights, and preview events. 5 Catch-up vaccinations were scheduled through nearby clinics and in subsequent events for missed doses.

The intervention addressed factors affecting HPV vaccine uptake (e.g., social norms, health provider recommendations, risk perceptions, accessibility, costs). 5 Physicians addressed the audience, targeted the middle schoolers in the recommended age group (11–12 years), and bundled HPV with recommended vaccines (e.g., flu; meningococcal; meningitis B; tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis; and hepatitis A vaccines). Parents were required to be present at the administration of the first dose. 5

The goals were to increase HPV vaccine initiation rates (the percentages of eligible students who received at least one dose) and up-to-date completion rates (the percentages of eligible students younger than 15 years who completed two doses and the percentages who completed three doses among those who initiated vaccination at 15 years or above or had immunocompromising conditions) to meet the 2016 National Immunization Survey—Teen HPV vaccination rates (initiation: 49.3%; completion: 32.9%). HPV vaccine initiation was defined as receipt of the first dose of the HPV vaccine series. HPV vaccine completion was defined as an interval of at least 6 months apart from initiation to the next dose. 6

Student vaccination data were refreshed quarterly. Baseline HPV vaccination rates and demographic information were collected for the study cohort during June 2019 to March 2021. HPV vaccination data were collected from the vaccine vendor and school immunization records and reconciled with Immtrac2 (the Texas Immunization Registry). The registry is secure and confidential and safely consolidates and stores immunization records from multiple sources in a single centralized system. Summary statistics were computed for each school. We used the χ2 test and analyses of variance to compare school differences between intervention groups (phase 1, phase 2, and phase 3) for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. HPV initiation and completion rates were computed from the start of the school-based vaccination intervention (June 2019) to March 2021 and stratified by middle school and sex. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) was used in conducting all analyses. Statistical significance was set at an α of .05 (two-sided).

PLACE, TIME, AND PERSONS

Eight PSJA ISD middle schools participated from June 2019 to March 2021. Using previously identified barriers from another RGV study, 5, 7 we strengthened our strategies, continued to target female and male middle schoolers (11–12 years of age), and extended the study area for school-based vaccinations from the RGC ISD to the PSJA ISD. Before COVID-19, school-based vaccination events were held in nurses’ offices, conference rooms, nearby clinics, and community events. The COVID-19 pandemic hit in the middle of the first year of implementation. After school closures, we held outside events with social distancing, limited in-person activities and increased online activities, and sought to increase stakeholder engagement through teleconferences, navigational services, and mobile van vaccinations.

PURPOSE

Texas ranks 47th of the 50 states and the District of Columbia in terms of HPV up-to-date vaccination rates. 8 Texas continues to have a 10% lower uptake of HPV initiation than the rest of the United States, with HPV vaccine coverage among girls 13 to 17 years old decreasing in 2016. 9 Because rural communities often have higher incidence and mortality rates of HPV-associated cancers and lower HPV vaccination rates, 10 offering the HPV vaccine at no cost is important in the RGV, a rural, medically underserved area (with four counties bordering Mexico: Cameron, Hidalgo, Starr, and Willacy). Residents of this area are more likely to be Hispanic, medically underserved, less educated, less literate in terms of health knowledge, and economically disadvantaged than residents of other areas of Texas. 11 Women residing in the RGV have a 30% higher incidence of and mortality from HPV-associated cervical cancer. 12

EVALUATION AND ADVERSE EFFECTS

Our community-based education and school-based vaccination intervention has helped strengthen adolescent health in the RGV. 5 Despite COVID-19 conditions, HPV vaccine initiation and completion rates in the PSJA ISD increased 1.29-fold and 1.47-fold, respectively, between June 2019 and March 2021 (Figures 1 and 2; Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at https://www.ajph.org).

FIGURE 1—

Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Initiation Rates for Pharr–San Juan–Alamo Middle Schools: Rio Grande Valley, TX, 2019–2021

Note. LBJ = Lyndon B. Johnson; MS = middle school.

FIGURE 2—

Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Completion Rates for Pharr–San Juan–Alamo Middle Schools: Rio Grande Valley, TX, 2019–2021

Note. LBJ = Lyndon B. Johnson; MS = middle school.

Notwithstanding the program’s successes, we faced numerous challenges. Extensive recovery efforts were made to minimize the potential long-term consequences despite school and clinic closures and limited gatherings. Adjustments were made to safely interact with the community (telephone calls and virtual meetings through Zoom to educate the community and continuing vaccination efforts through mobile clinics). Between March 2020 and March 2021, 268 HPV vaccine doses were provided through 24 school-based interventions. The study identified those who missed their vaccinations and reestablished community demand through HPV “catch-up” campaigns. Our results suggest that middle schools are a feasible, effective setting for increasing HPV uptake.

SUSTAINABILITY

Sustainability is of paramount importance in this area with higher cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates, lower HPV vaccination rates, and a high proportion of low-income and largely uninsured, rural minority residents. With the appropriate resources and partnerships, schools can carry out vaccine-related activities ranging from educating students, parents, and communities to developing policies supporting vaccination, providing vaccines, and serving as sites where partners administer vaccines. We have improved organizational capacity (communications) by developing a curriculum and “train-the-trainer” training sessions for individuals interested in continuing our education efforts. Health care providers have been trained to bundle and provide strong recommendations for the HPV vaccine. Our community-based education and school-based vaccination program has been successful in building community demand. We have received requests to extend the program to additional RGV school districts.

PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE

As noted, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected health care delivery, with dramatic drops in annual well visits, cancer screenings, and HPV vaccinations. Our results show that schools continue to serve as feasible, effective settings for increasing HPV vaccine uptake. Our program increases access to the HPV vaccine; reaches a large, diverse population regardless of individual access to health care; and removes known barriers. Our COVID-19 adaptations have allowed for a safe environment for middle schoolers to get vaccinated. HPV vaccine uptake can be sustained if the vaccine is bundled with other required vaccines and parents, local providers, school board members, and school staff are educated about its importance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Institute for Translational Sciences at the University of Texas Medical Branch, with partial support from a National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Clinical and Translational Science Award (grant UL1 TR001439). In addition, A. M. Rodriguez and Y. -F. Kuo received funding from the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT; grants PP160097, PP190023, and P200057).

Note. Neither the National Institutes of Health (NIH) nor CPRIT had a role in the development of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or CPRIT.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Approval was obtained from the University of Texas Medical Branch’s institutional review board and the Pharr–San Juan–Alamo Independent School District school board. Informed consent was required for middle schoolers to be vaccinated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Oyo-Ita A, Wiysonge CS, Oringanje C, Nwachukwu CE, Oduwole O, Meremikwu MM. Interventions for improving coverage of childhood immunisation in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;7(7):CD008145. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008145.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lassi ZS, Naseem R, Salam RA, Siddiqui F, Das JK. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on immunization campaigns and programs: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):988. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18030988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daniels V, Saxena K, Roberts C, et al. Impact of reduced human papillomavirus vaccination coverage rates due to COVID-19 in the United States: a model based analysis. Vaccine. 2021;39(20):2731–2735. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodworth K.2021. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2021-05-12/05-COVID-Woodworth-508.pdf

- 5.Kaul S, Do TQN, Hsu E, Schmeler KM, Montealegre JR, Rodriguez AM. School-based human papillomavirus vaccination program for increasing vaccine uptake in an underserved area in Texas. Papillomavirus Res. 2019;8:100189. doi: 10.1016/j.pvr.2019.100189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV vaccine schedule and dosing. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/schedules-recommendations.html

- 7.Victory M, Do TQN, Kuo Y-F, Rodriguez AM. Parental knowledge gaps and barriers for children receiving human papillomavirus vaccine in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1678–1687. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1628551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Singleton JA, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(33):874–882. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6633a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nehme E, Patel D, Oppenheimer D, Elerian N, Lakey D.2021. https://www.utsystem.edu/sites/default/files/news/assets/HPV%20in%20Texas%20Report.pdf

- 10.Brandt HM, Vanderpool RC, Pilar M, Zubizarreta M, Stradtman LR. A narrative review of HPV vaccination interventions in rural US communities. Prev Med. 2021;145:106407. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/time-series/demo/census-poverty-tool.html

- 12.Center for Reproductive Rights. 2021. https://reproductiverights.org/nuestra-voz-nuestra-salud-nuestro-texas-the-fight-for-womens-reproductive-health-in-the-rio-grande-valley