Key Points

Question

Is the 90-day incidence of arterial thromboembolism and venous thromboembolism higher in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 vs in patients hospitalized with influenza?

Findings

In this retrospective cohort study that included 93 906 patients, hospitalization with COVID-19 before vaccine availability and during vaccine availability was significantly associated with higher 90-day risk of venous thromboembolism (adjusted hazard ratios, 1.60 and 1.89, respectively) vs hospitalization with influenza in 2018-2019, but there was no significant difference in the risk of arterial thromboembolism among those hospitalized with COVID-19 during either period (adjusted hazard ratios, 1.04 and 1.07) vs those hospitalized with influenza.

Meaning

Hospitalization with COVID-19 both before and during vaccine availability was significantly associated with a higher risk of venous thromboembolism, but not arterial thromboembolism, vs hospitalization with influenza in 2018-2019.

Abstract

Importance

The incidence of arterial thromboembolism and venous thromboembolism in persons with COVID-19 remains unclear.

Objective

To measure the 90-day risk of arterial thromboembolism and venous thromboembolism in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 before or during COVID-19 vaccine availability vs patients hospitalized with influenza.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective cohort study of 41 443 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (April-November 2020), 44 194 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 during vaccine availability (December 2020-May 2021), and 8269 patients hospitalized with influenza (October 2018-April 2019) in the US Food and Drug Administration Sentinel System (data from 2 national health insurers and 4 regional integrated health systems).

Exposures

COVID-19 or influenza (identified by hospital diagnosis or nucleic acid test).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Hospital diagnosis of arterial thromboembolism (acute myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke) and venous thromboembolism (deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism) within 90 days. Outcomes were ascertained through July 2019 for patients with influenza and through August 2021 for patients with COVID-19. Propensity scores with fine stratification were developed to account for differences between the influenza and COVID-19 cohorts. Weighted Cox regression was used to estimate the adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for outcomes during each COVID-19 vaccine availability period vs the influenza period.

Results

A total of 85 637 patients with COVID-19 (mean age, 72 [SD, 13.0] years; 50.5% were male) and 8269 with influenza (mean age, 72 [SD, 13.3] years; 45.0% were male) were included. The 90-day absolute risk of arterial thromboembolism was 14.4% (95% CI, 13.6%-15.2%) in patients with influenza vs 15.8% (95% CI, 15.5%-16.2%) in patients with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (risk difference, 1.4% [95% CI, 1.0%-2.3%]) and 16.3% (95% CI, 16.0%-16.6%) in patients with COVID-19 during vaccine availability (risk difference, 1.9% [95% CI, 1.1%-2.7%]). Compared with patients with influenza, the risk of arterial thromboembolism was not significantly higher among patients with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 1.04 [95% CI, 0.97-1.11]) or during vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 1.07 [95% CI, 1.00-1.14]). The 90-day absolute risk of venous thromboembolism was 5.3% (95% CI, 4.9%-5.8%) in patients with influenza vs 9.5% (95% CI, 9.2%-9.7%) in patients with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (risk difference, 4.1% [95% CI, 3.6%-4.7%]) and 10.9% (95% CI, 10.6%-11.1%) in patients with COVID-19 during vaccine availability (risk difference, 5.5% [95% CI, 5.0%-6.1%]). Compared with patients with influenza, the risk of venous thromboembolism was significantly higher among patients with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 1.60 [95% CI, 1.43-1.79]) and during vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 1.89 [95% CI, 1.68-2.12]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Based on data from a US public health surveillance system, hospitalization with COVID-19 before and during vaccine availability, vs hospitalization with influenza in 2018-2019, was significantly associated with a higher risk of venous thromboembolism within 90 days, but there was no significant difference in the risk of arterial thromboembolism within 90 days.

This cohort study uses data from the US Food and Drug Administration Sentinel System to measure the 90-day risk of arterial thromboembolism and venous thromboembolism among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 before and during COVID-19 vaccine availability vs patients hospitalized with influenza.

Introduction

COVID-19 is primarily an acute respiratory illness, but evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 infection may also induce a hypercoagulable state resulting in arterial thromboembolism or venous thromboembolism.1,2,3,4 In case series, up to 30% of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 developed arterial thromboembolism (ie, acute myocardial infarction or stroke) or venous thromboembolism (ie, acute deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism).2,5,6,7,8,9,10 However, studies examining thrombotic complications from COVID-19 have included small samples, rarely included a comparator group, and have not evaluated characteristics associated with these outcomes.11 Therefore, the incidence, determinants, and consequences of arterial thromboembolism and venous thromboembolism with COVID-19 remain unclear.

This study evaluated the 90-day risk of arterial thromboembolism and venous thromboembolism among patients initially diagnosed with COVID-19 in the hospital both before and during COVID-19 vaccine availability in the US. The risk of arterial thromboembolism and venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19 during each of these periods was compared with the risk among patients initially diagnosed with influenza in the hospital prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients with influenza were selected as the comparator because influenza has been associated with increased risk of myocardial infarction,12 ischemic stroke,13 and venous thromboembolism.14,15 Among patients with COVID-19, characteristics present prior to hospitalization were examined for associations with arterial thromboembolism and venous thromboembolism.

Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

A retrospective cohort study was performed using data from the US Food and Drug Administration Sentinel System, a multisite distributed data network with standardized, quality-checked administrative claims and electronic health record data.16,17 The data included health plan enrollment dates, demographics, diagnoses (using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] codes), laboratory results, and dispensed outpatient medications.

The included data were from 2 national health insurers (Aetna and Humana Inc) and 4 regional integrated health systems (HealthPartners, Kaiser Permanente Colorado, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, and Kaiser Permanente Washington).17 The Sentinel System is a public health surveillance activity under the authority of the US Food and Drug Administration and is not subject to institutional review board oversight.18,19

Study Patients

Eligibility criteria in the COVID-19 cohorts included: (1) patients who had an initial COVID-19 ICD-10-CM diagnosis code U07.1 or positive SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid test result (eTable 1 in the Supplement) recorded in the hospital between April 1, 2020, and May 31, 2021, (2) patients who were aged 18 years or older at diagnosis, and (3) patients who had 365 days or longer of continuous prior medical and pharmacy coverage at diagnosis. Eligibility criteria in the influenza cohort included: (1) patients who had an initial influenza ICD-10-CM diagnosis (the codes appear in eTable 2 in the Supplement) or a positive influenza nucleic acid test result (eTable 1 in the Supplement) recorded in the hospital between October 1, 2018, and April 30, 2019, (2) patients who were aged 18 years or older at diagnosis, and (3) patients who had 365 days or longer of continuous prior medical and pharmacy coverage at diagnosis.

We included patients diagnosed during the 2018-2019 influenza season to ensure that patients with influenza were not co-infected with COVID-19. The 2018-2019 influenza season was moderately severe.20 Patients in the influenza cohort were allowed to be included in the COVID-19 cohorts because it was unlikely that prior influenza infection would affect thrombosis risk with COVID-19. Patients initially diagnosed with COVID-19 or influenza in the ambulatory setting were excluded.

Follow-up began on the date of hospital admission. Within each cohort, patients with diagnostic or laboratory evidence of their infection within 90 days prior to admission were excluded to ensure inclusion of incident infections. Patients diagnosed with another respiratory virus within 14 days of admission were excluded (the ICD-10-CM codes appear in eTable 3 in the Supplement). The 365 days prior to admission represented the baseline period. Follow-up continued until a study end point was reached (defined below), disenrollment from medical or pharmacy coverage, death, or 90 days after admission, whichever occurred first (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

Study Outcomes

The 2 primary outcomes were (1) inpatient arterial thromboembolism (defined by a principal or contributory hospital discharge diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke) and (2) inpatient venous thromboembolism (defined by a principal or contributory hospital discharge diagnosis of acute deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism). Events were ascertained using ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes (eTable 4 in the Supplement) mapped from International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis codes for arterial thromboembolism21,22,23,24 and venous thromboembolism25,26 that had been validated in these data against medical record review. Prior to this analysis, the mapped ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes underwent clinical review to ensure appropriate inclusion within arterial thromboembolism and venous thromboembolism end point algorithms. The secondary outcomes were an expanded arterial thromboembolism end point (defined by emergency department or hospital discharge diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, angina, transient ischemic attack, or peripheral artery disease) and an expanded venous thromboembolism end point (defined by emergency department or hospital discharge diagnosis of acute deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or venous thrombosis of devices, implants, or grafts). The primary and secondary thrombotic outcomes were ascertained through July 29, 2019, for patients with influenza and through August 29, 2021, for patients with COVID-19.

All-cause mortality within 30 days after arterial thromboembolism or venous thromboembolism was an additional secondary outcome. Mortality was ascertained through August 28, 2019, for patients with influenza and through September 28, 2021, for patients with COVID-19.

Covariates

The covariates included age at diagnosis, sex, race and ethnicity (obtained by self-report via closed-ended questionnaires or patient intake forms), month of COVID-19 diagnosis, severity of infection (never admitted to the intensive care unit and did not require mechanical ventilation; or admitted to the intensive care unit or required mechanical ventilation), and the number of hospital and ambulatory encounters during the year before hospitalization. Race and ethnicity were evaluated as descriptive variables to assess for differences in outcomes among patients with COVID-19.

During the baseline period, diagnoses that might influence SARS-CoV-2 or influenza infection, or affect thrombosis risk, were identified (Table 1 and eTable 5 in the Supplement), as defined previously.28 Baseline hemoglobin levels and platelet counts from the dates closest to (or on) the admission date were collected. Dispensed outpatient prescriptions for anticoagulants, antiplatelet drugs, statins, and other products possibly affecting coagulation were identified from the prior 183 days through 3 days prior to the date of hospital admission (eTable 6 in the Supplement).

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 Before or During Vaccine Availability vs Patients Hospitalized With Influenza.

| No. (%)a | Standardized difference after development of the propensity scores with fine stratification and weighting | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 cohorts | Influenza cohort (Oct 1, 2018-Apr 30, 2019) (n = 8269) |

||||

| Before vaccine availability (Apr 1-Nov 30, 2020) (n = 41 443) |

During vaccine availability (Dec 1, 2020-May 31, 2021) (n = 44 194) |

COVID-19 cohort before vaccine availability vs influenza cohort |

COVID-19 cohort during vaccine availability vs influenza cohort |

||

| Age, mean (SD), yb | 72.3 (13.1) | 72.3 (12.8) | 71.9 (13.3) | 0.018 | 0.026 |

| Age group, y | |||||

| 18-44 | 2032 (4.9) | 2021 (4.6) | 373 (4.5) | −0.029 | −0.040 |

| 45-54 | 2186 (5.3) | 2158 (4.9) | 437 (5.3) | −0.024 | −0.033 |

| 55-64 | 5161 (12.5) | 5475 (12.4) | 1265 (15.3) | −0.043 | −0.044 |

| 65-74 | 12 889 (31.1) | 14 276 (32.3) | 2499 (30.2) | 0.073 | 0.084 |

| 75-84 | 12 649 (30.5) | 13 709 (31.0) | 2422 (29.3) | 0.018 | 0.020 |

| ≥85 | 6526 (15.7) | 6555 (14.8) | 1273 (15.4) | −0.042 | −0.049 |

| Sexb | |||||

| Male | 20 890 (50.4) | 22 330 (50.5) | 3725 (45.0) | 0.003 | −0.003 |

| Female | 20 553 (49.6) | 21 864 (49.5) | 4544 (55.0) | −0.003 | 0.003 |

| Racec | |||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 194 (0.5) | 172 (0.4) | 31 (0.4) | 0.015 | −0.002 |

| Asian | 657 (1.6) | 721 (1.6) | 125 (1.5) | −0.017 | −0.002 |

| Black or African American | 8613 (20.8) | 7790 (17.6) | 1095 (13.2) | 0.168 | 0.090 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 385 (0.9) | 365 (0.8) | 66 (0.8) | −0.010 | −0.014 |

| White | 25 955 (62.6) | 27 584 (62.4) | 6141 (74.3) | −0.192 | −0.208 |

| Unknown | 5639 (13.6) | 7562 (17.1) | 811 (9.8) | 0.089 | 0.203 |

| Hispanic ethnicityc | |||||

| Yes | 2070 (5.0) | 1571 (3.6) | 215 (2.6) | 0.093 | 0.027 |

| No | 28 392 (68.5) | 28 966 (65.5) | 5921 (71.6) | −0.110 | −0.243 |

| Unknown | 10 981 (26.5) | 13 657 (30.9) | 2133 (25.8) | 0.035 | 0.261 |

| Year of diagnosis | |||||

| 2018 | 1205 (14.6) | ||||

| 2019 | 7064 (85.4) | ||||

| 2020 | 41 443 (100) | 13 674 (30.9) | |||

| 2021 | 30 520 (69.1) | ||||

| Geographic location | |||||

| South | 21 102 (50.9) | 22 600 (51.1) | 3983 (48.2) | 0.069 | 0.077 |

| Midwest | 9611 (23.2) | 9034 (20.4) | 1712 (20.7) | 0.071 | 0.005 |

| West | 6145 (14.8) | 6513 (14.7) | 1633 (19.7) | −0.195 | −0.202 |

| Northeast | 4341 (10.5) | 5834 (13.2) | 870 (10.5) | 0 | 0.090 |

| Other or missing | 244 (0.6) | 213 (0.5) | 71 (0.9) | −0.045 | −0.061 |

| Health encounters by type, mean (SD)b | |||||

| Ambulatory | 25.7 (32.7) | 24.3 (31.3) | 27.2 (30.2) | −0.003 | 0.003 |

| Hospital | 0.7 (1.3) | 0.5 (1.2) | 0.8 (1.3) | 0.003 | −0.017 |

| Charlson or Elixhauser comorbidity score, mean (SD)b,d,e | 4.3 (3.9) | 3.9 (3.8) | 4.4 (3.6) | −0.011 | −0.031 |

| Comorbiditiesf | |||||

| Hypertensionb,d | 36 220 (87.4) | 38 442 (87.0) | 7138 (86.3) | 0.057 | 0.051 |

| Hyperlipidemiab,d | 31 740 (76.6) | 33 761 (76.4) | 6065 (73.3) | 0.034 | 0.037 |

| History of cardiovascular diseaseb,g | 23 325 (56.3) | 24 041 (54.4) | 4746 (57.4) | 0.001 | −0.012 |

| Prior coronary artery diseaseg | 17 788 (42.9) | 18 358 (41.5) | 3783 (45.7) | −0.008 | −0.019 |

| Prior PAD or acute limb ischemiag | 9515 (23.0) | 9363 (21.2) | 1654 (20.0) | 0.071 | 0.049 |

| Other prior cerebrovascular diseaseg | 7554 (18.2) | 7270 (16.5) | 1455 (17.6) | 0.009 | −0.007 |

| Recent outpatient anticoagulant useh | 7131 (17.2) | 7395 (16.7) | 1611 (19.5) | −0.006 | −0.018 |

| Prior myocardial infarctiong | 5710 (13.8) | 5803 (13.1) | 1239 (15.0) | −0.004 | −0.007 |

| Prior strokeg | 4701 (11.3) | 4226 (9.6) | 758 (9.2) | 0.054 | 0.028 |

| Any type of diabetesb,d | 21 775 (52.5) | 22 961 (52.0) | 3839 (46.4) | 0.027 | 0.022 |

| Type 2 diabetesd | 21 656 (52.3) | 22 827 (51.7) | 3803 (46.0) | 0.030 | 0.023 |

| Chronic kidney diseaseb,d | 21 151 (51.0) | 21 766 (49.3) | 3820 (46.2) | 0.009 | −0.007 |

| Tobacco useb,d | 18 415 (44.4) | 19 778 (44.8) | 4540 (54.9) | 0.008 | 0.003 |

| Obesityb,d | 17 908 (43.2) | 19 788 (44.8) | 3134 (37.9) | 0.018 | 0.019 |

| Heart failureb,d | 15 560 (37.5) | 16 218 (36.7) | 3593 (43.5) | 0.010 | −0.004 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseb,d | 15 012 (36.2) | 15 540 (35.2) | 4647 (56.2) | 0.031 | 0.033 |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutterb,d | 12 435 (30.0) | 13 055 (29.5) | 2811 (34.0) | −0.015 | −0.018 |

| Thrombocytosis (diagnosis code or platelet count >450 000/μL)b,d | 11 285 (27.2) | 11 266 (25.5) | 1709 (20.7) | 0.022 | 0.014 |

| Cancer (excluding non–melanoma skin cancer)b,d | 10 982 (26.5) | 11 578 (26.2) | 2402 (29.0) | −0.009 | −0.006 |

| Neurological diseaseb,d | 8941 (21.6) | 7790 (17.6) | 1298 (15.7) | −0.012 | −0.019 |

| Chronic liver diseaseb,d | 6197 (15.0) | 6630 (15.0) | 1126 (13.6) | −0.009 | −0.009 |

| Asthmab,d | 5514 (13.3) | 5674 (12.8) | 1703 (20.6) | −0.011 | −0.010 |

| Outpatient use of select medicationsb,f,h,i | |||||

| Statins | 21 857 (52.7) | 24 005 (54.3) | 4224 (51.1) | 0.015 | 0.021 |

| Corticosteroids | 13 463 (32.5) | 14 868 (33.6) | 3804 (46.0) | 0.015 | 0.020 |

| ACE inhibitors | 10 665 (25.7) | 11 652 (26.4) | 2191 (26.5) | 0.009 | 0.019 |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers | 9183 (22.2) | 10 057 (22.8) | 1662 (20.1) | 0.014 | 0.014 |

| Anticoagulants | 8841 (21.3) | 9411 (21.3) | 2044 (24.7) | −0.016 | −0.020 |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 6015 (14.5) | 6415 (14.5) | 1035 (12.5) | 0.021 | 0.026 |

| Antiplatelets | 5117 (12.3) | 5426 (12.3) | 1092 (13.2) | −0.007 | −0.007 |

| Severity of infectionj | |||||

| Never admitted to the ICU and did not require mechanical ventilation | 18 204 (43.9) | 19 321 (43.7) | 3837 (46.4) | −0.086 | −0.085 |

| Admitted to the ICU or required mechanical ventilation | 23 239 (56.1) | 24 873 (56.3) | 4432 (53.6) | 0.086 | 0.085 |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ICU, intensive care unit; PAD, peripheral artery disease.

Some of the data are expressed as mean (SD) as indicated. These data are not weighted.

Included in the propensity score logistic regression model.

Obtained by self-report via closed-ended questionnaires or patient intake forms. These were evaluated as descriptive variables because of disparities in the effects of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups. Unknown race or ethnicity includes those who provided responses other than the options available in the closed-ended questionnaires and patient intake forms.

Based on reported information from the prior 365 days to the date of hospital admission.

Calculated based on the comorbidities observed during a requester-defined window around the exposure episode start date.27

The data for comorbidities with frequencies of less 10% appear in eTable 5 in the Supplement.

Based on reported information from the prior 365 days through 1 day prior to the date of hospital admission.

Based on reported information from the prior 183 days through 3 days prior to the date of hospital admission.

Specified drug classes appear in eTable 6 in the Supplement.

Due to the nature of administrative claims data and the reliance on diagnosis and procedure codes, the data for this category are likely incomplete.

Statistical Analysis

Because evaluation for thrombotic complications might have changed during the pandemic and because COVID-19 vaccination might affect risk of thrombosis after SARS-CoV-2 infection, patients with COVID-19 were evaluated separately for the period before vaccine availability (April-November 2020) and the period during vaccine availability (December 2020-May 2021) in the US. The between-group differences in the characteristics of patients in the COVID-19 and influenza cohorts were assessed using standardized differences, of which an absolute value of 0.1 or greater suggests a meaningful imbalance.29 The 90-day absolute risk of first arterial thromboembolism and venous thromboembolism (with 95% CIs) was measured for each cohort overall and stratified by demographics, diagnosis of cardiovascular disease or prior venous thromboembolism, severity of infection, and month at diagnosis (for patients with COVID-19).

Propensity scores were used to control for differences in characteristics between the influenza cohort and each COVID-19 period cohort. Within each of the 6 data sources, a single propensity score was estimated for each patient using logistic regression; COVID-19 (vs influenza) status was used as the dependent variable. The variables included in the propensity score appear in Table 1 and in eTable 5 in the Supplement. Patients were excluded from the COVID-19 cohorts if their propensity score exceeded the maximum or minimum values in the influenza cohort and vice versa. Fine stratification for the propensity scores was used to retain the maximum number of patients.30 Patients were assigned to 1 of 50 propensity score strata based on quantiles of the propensity score distribution among patients with COVID-19. Stratum-specific weights were calculated using the distribution of exposure within each stratum to create a weighted population reflecting the characteristics of the overall sample.31 Development of the propensity scores with fine stratification and weighting was then implemented because (1) traditional unweighted propensity score stratification would be unlikely to offer strong confounding control and (2) inverse probability weighting could yield extreme weights that are challenging to address in distributed analyses.30,31

Weighted Cox regression (accounting for propensity scores and adjusted for the data source) was used to calculate the hazard ratios (HRs) with robust 95% CIs for the primary and secondary thrombotic outcomes comparing COVID-19 during each period vs influenza.32 For the primary end points, the results were stratified by cardiovascular disease (arterial thromboembolism analysis) or prior venous thromboembolism (venous thromboembolism analysis). The robustness of the results of the primary analyses to unmeasured confounding were assessed using E-values, which represent the minimum strength of an association (on the risk ratio scale) that an unmeasured confounder would need to have with both the exposure and the outcome to explain away an observed association, conditional on the measured covariates.33 For patients who had an inpatient arterial or venous thrombotic event, weighted Cox regression was used to determine the HRs for 30-day all-cause mortality for COVID-19 during each period vs influenza.

Among patients with COVID-19, baseline variables were evaluated as risk factors for arterial thromboembolism and venous thromboembolism because of their potential to promote stasis of circulation, endothelial injury, or hypercoagulability. Variables included alcohol dependence or alcohol use disorder, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, atrial fibrillation or flutter, cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, heart failure, cardiovascular disease (for the analysis of arterial thromboembolism) or prior venous thromboembolism (for the analysis of venous thromboembolism), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, inherited thrombophilia, neurological diseases that promote immobility (Alzheimer disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, dementia, Guillain-Barre syndrome, multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, Parkinson disease), obesity, older age group (45-54 years, 55-64 years, 65-74 years, 75-84 years, or ≥85 years), pregnancy, polycythemia (diagnosis or hemoglobin level >16.0 g/dL), rheumatologic disease, sex, thrombocytosis (diagnosis or platelet count >450 000/μL), tobacco use, and recent outpatient use of an anticoagulant, antiplatelet, or statin within 3 to 183 days before hospitalization. Multivariable Cox regression models that separately evaluated patients with COVID-19 before and during vaccine availability were used to estimate the HRs with 95% CIs for arterial thromboembolism and venous thromboembolism associated with each risk factor and were adjusted for age and sex (in 1 set of analyses) and all risk factors (in another set of analyses).

All hypothesis tests were 2-sided. Statistical significance was declared if P<.05. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, the analyses of the secondary outcomes should be interpreted as exploratory. The data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Cohort Characteristics

Patients who met inclusion criteria consisted of 41 443 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 before vaccines were available, 44 194 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 during vaccine availability, and 8269 patients hospitalized with influenza (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Prior to the development of the propensity scores with fine stratification and weighting and compared with patients with influenza, the COVID-19 cohorts contained patients who were slightly older, had lower proportions of female and White patients, and had higher proportions of patients with preexisting comorbidities (including chronic kidney disease, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia; Table 1). Compared with patients with COVID-19, patients with influenza had a significantly higher prevalence of asthma, COPD, heart failure, and dispensed corticosteroids. After development of the propensity scores with fine stratification and weighting, there were no between-group standardized differences of 0.1 or greater for the variables in the propensity score models. Some variables not included in propensity score models had standardized differences of 0.1 or greater (Table 1 and eTable 5 in the Supplement). There were no missing data for the variables included in the propensity score and outcome models. No observations were excluded due to missing data.

Risk of Arterial Thromboembolism in Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 vs Patients Hospitalized With Influenza

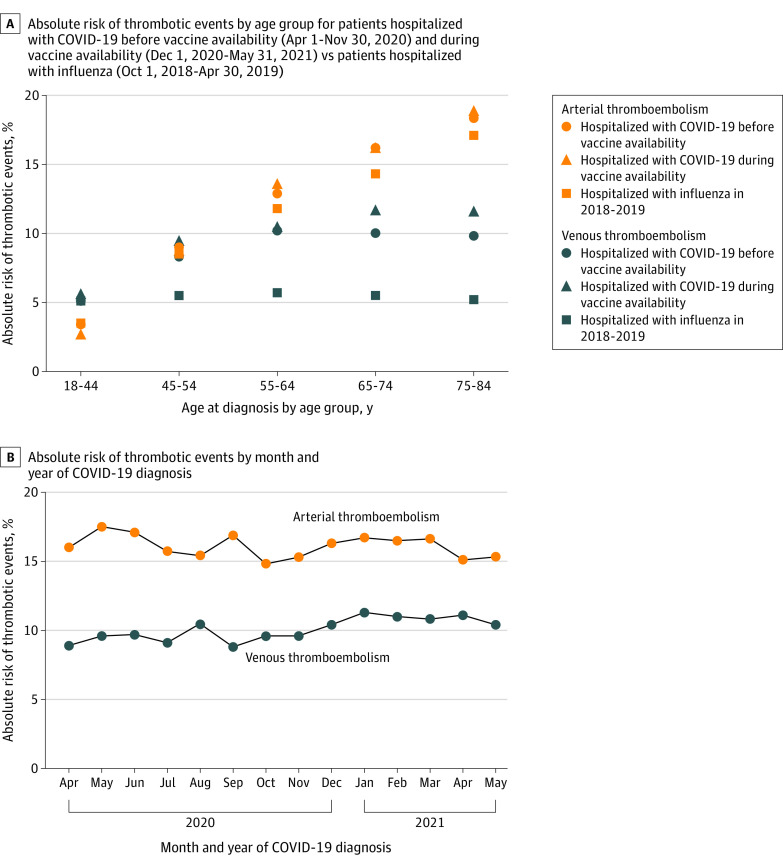

The 90-day absolute risk of arterial thromboembolism was 14.4% (95% CI, 13.6%-15.2%) among patients hospitalized with influenza vs 15.8% (95% CI, 15.5%-16.2%) among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (risk difference, 1.4% [95% CI, 1.0%-2.3%]) and 16.3% (95% CI, 16.0%-16.6%) among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 during vaccine availability (risk difference, 1.9% [95% CI, 1.1%-2.7%]). Within each cohort, the 90-day risk of arterial thromboembolism was significantly higher among patients who were older, male, admitted to the intensive care unit or required mechanical ventilation, or had history of cardiovascular disease (Table 2 and eTable 7 in the Supplement). Among patients with COVID-19, the risks of arterial thromboembolism were similar across the study periods (Figure and eTable 7 in the Supplement).

Table 2. 90-Day Absolute Risk of Arterial and Venous Thrombotic Events Among Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 Before or During Vaccine Availability vs Patients Hospitalized With Influenza.

| COVID-19 cohortsa | Influenza cohort (Oct 1, 2018-Apr 30, 2019) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before vaccine availability (Apr 1-Nov 30, 2020) |

During vaccine availability (Dec 1, 2020-May 31, 2021) |

||||||||

| No. of patientsb |

No. of eventsb |

Absolute risk, % | No. of patientsb |

No. of eventsb |

Absolute risk, % | No. of patientsb |

No. of eventsb |

Absolute risk, % | |

| Arterial thromboembolism c | |||||||||

| Overall | 41 443 | 6559 | 15.8 | 44 194 | 7202 | 16.3 | 8269 | 1190 | 14.4 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 20 890 | 3580 | 17.1 | 22 330 | 4000 | 17.9 | 3725 | 604 | 16.2 |

| Female | 20 553 | 2979 | 14.5 | 21 864 | 3202 | 14.6 | 4544 | 586 | 12.9 |

| Raced | |||||||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 194 | 20 | 10.3 | 172 | 22 | 12.8 | 31 | 3 | 9.7 |

| Asian | 657 | 97 | 14.8 | 721 | 107 | 14.8 | 125 | 14 | 11.2 |

| Black or African American | 8613 | 1614 | 18.7 | 7790 | 1536 | 19.7 | 1095 | 196 | 17.9 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 385 | 72 | 18.7 | 365 | 76 | 20.8 | 66 | 14 | 21.2 |

| White | 25 955 | 4199 | 16.2 | 27 584 | 4506 | 16.3 | 6141 | 895 | 14.6 |

| Unknown | 5639 | 557 | 9.9 | 7562 | 955 | 12.6 | 811 | 68 | 8.4 |

| Hispanic ethnicityd | |||||||||

| Yes | 2070 | 218 | 10.5 | 1571 | 178 | 11.3 | 215 | 18 | 8.4 |

| No | 28 392 | 4813 | 17.0 | 28 966 | 5024 | 17.3 | 5921 | 896 | 15.1 |

| Unknown | 10 981 | 1528 | 13.9 | 13 657 | 2000 | 14.6 | 2133 | 276 | 12.9 |

| History of cardiovascular diseasee | 23 325 | 4901 | 21.0 | 24 041 | 5115 | 21.3 | 4746 | 865 | 18.2 |

| Recent outpatient anticoagulant usef | 7131 | 1648 | 23.1 | 7395 | 1602 | 21.7 | 1611 | 287 | 17.8 |

| No recent outpatient anticoagulant usef | 16 194 | 3253 | 20.1 | 16 646 | 3513 | 21.1 | 3135 | 578 | 18.4 |

| Prior venous thrombotic evente | 3275 | 661 | 20.2 | 3146 | 613 | 19.5 | 604 | 93 | 15.4 |

| Recent outpatient anticoagulant usef | 2016 | 399 | 19.8 | 2040 | 358 | 17.5 | 389 | 67 | 17.2 |

| No recent outpatient anticoagulant usef | 1259 | 262 | 20.8 | 1106 | 255 | 23.1 | 215 | 26 | 12.1 |

| Severity of infectiong | |||||||||

| Never admitted to the ICU and did not require mechanical ventilation | 18 204 | 2025 | 11.1 | 19 321 | 2173 | 11.2 | 3837 | 340 | 8.9 |

| Admitted to the ICU or required mechanical ventilation | 23 239 | 4534 | 19.5 | 24 873 | 5029 | 20.2 | 4432 | 850 | 19.2 |

| Venous thromboembolism h | |||||||||

| Overall | 41 443 | 3917 | 9.5 | 44 194 | 4799 | 10.9 | 8269 | 440 | 5.3 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 20 890 | 2040 | 9.8 | 22 330 | 2567 | 11.5 | 3725 | 190 | 5.1 |

| Female | 20 553 | 1877 | 9.1 | 21 864 | 2232 | 10.2 | 4544 | 250 | 5.5 |

| Raced | |||||||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 194 | 14 | 7.2 | 172 | 17 | 9.9 | 31 | 1 | 3.2 |

| Asian | 657 | 54 | 8.2 | 721 | 59 | 8.2 | 125 | 5 | 4.0 |

| Black or African American | 8613 | 945 | 11.0 | 7790 | 1102 | 14.1 | 1095 | 74 | 6.8 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 385 | 32 | 8.3 | 365 | 25 | 6.8 | 66 | 3 | 4.5 |

| White | 25 955 | 2444 | 9.4 | 27 584 | 2831 | 10.3 | 6141 | 313 | 5.1 |

| Unknown | 5639 | 428 | 7.6 | 7562 | 765 | 10.1 | 811 | 44 | 5.4 |

| Hispanic ethnicityd | |||||||||

| Yes | 2070 | 147 | 7.1 | 1571 | 133 | 8.5 | 215 | 12 | 5.6 |

| No | 28 392 | 2717 | 9.6 | 28 966 | 3138 | 10.8 | 5921 | 313 | 5.3 |

| Unknown | 10 981 | 1053 | 9.6 | 13 657 | 1528 | 11.2 | 2133 | 115 | 5.4 |

| History of cardiovascular diseasee | 23 325 | 2335 | 10.0 | 24 041 | 2628 | 10.9 | 4746 | 273 | 5.8 |

| Recent outpatient anticoagulant usef | 7131 | 853 | 12.0 | 7395 | 915 | 12.4 | 1611 | 121 | 7.5 |

| No recent outpatient anticoagulant usef | 16 194 | 1482 | 9.2 | 16 646 | 1713 | 10.3 | 3135 | 152 | 4.8 |

| Prior venous thrombotic evente | 3275 | 977 | 29.8 | 3146 | 982 | 31.2 | 604 | 133 | 22.0 |

| Recent outpatient anticoagulant usef | 2016 | 623 | 30.9 | 2040 | 642 | 31.5 | 389 | 90 | 23.1 |

| No recent outpatient anticoagulant usef | 1259 | 354 | 28.1 | 1106 | 340 | 30.7 | 215 | 43 | 20.0 |

| Severity of infectiong | |||||||||

| Never admitted to the ICU and did not require mechanical ventilation | 18 204 | 1266 | 7.0 | 19 321 | 1482 | 7.7 | 3837 | 129 | 3.4 |

| Admitted to the ICU or required mechanical ventilation | 23 239 | 2651 | 11.4 | 24 873 | 3317 | 13.3 | 4432 | 311 | 7.0 |

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit

Data on age category and month at the time of COVID-19 diagnosis appear in the Figure and in eTable 7 in the Supplement.

These data are not weighted.

Hospital diagnosis included acute myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke.

Obtained by self-report via closed-ended questionnaires or patient intake forms. These were evaluated as descriptive variables because of disparities in the effects of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups. Unknown race or ethnicity includes those who provided responses other than the options available in the closed-ended questionnaires and patient intake forms.

Based on reported information from the prior 365 days through 1 day prior to the date of hospital admission.

Based on reported information from the prior 183 days through 3 days prior to the date of hospital admission.

Due to the nature of administrative claims data and the reliance on diagnosis and procedure codes, the data for this category are likely incomplete.

Hospital diagnosis included deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.

Figure. Absolute Risk of Inpatient Arterial and Venous Thrombotic Events.

Hospital diagnosis of arterial thromboembolism included acute myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke. Hospital diagnosis of venous thromboembolism included deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.

After development of the propensity scores with fine stratification and weighting and compared with patients with influenza, the risk of arterial thromboembolism was not significantly higher in patients with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 1.04 [95% CI, 0.97-1.11]) or in patients with COVID-19 during vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 1.07 [95% CI, 1.00-1.14]) (Table 3). The E-values for the point estimates were 1.20 for the period before vaccine availability and 1.27 during vaccine availability. Associations were similar when evaluating the secondary outcome of arterial thromboembolism with an emergency department or hospital discharge diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, angina, transient ischemic attack, or peripheral artery disease in patients with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 1.02 [95% CI, 0.98-1.06]) and in patients with COVID-19 during vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 1.03 [95% CI, 1.00-1.07]).

Table 3. Hazard Ratios for 90-Day Arterial and Venous Thrombotic Events Among Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 Before or During Vaccine Availability vs Patients Hospitalized With Influenza.

| COVID-19 cohort before vaccine availability (Apr 1, 2020-Nov 30, 2020) vs influenza cohort |

COVID-19 cohort during vaccine availability (Dec 1, 2020-May 31, 2021) vs influenza cohort |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patientsa | No. of eventsa | Risk per 100 patients | Difference in risk per 100 patients (95% CI) |

Hazard ratio (95% CI) | No. of patientsa | No. of eventsa | Risk per 100 patients | Difference in risk per 100 patients (95% CI) |

Hazard ratio (95% CI) | |||

| Unweighted | Weightedb | Unweighted | Weightedb | |||||||||

| Arterial thromboembolism | ||||||||||||

| Primary outcomec | ||||||||||||

| COVID-19 cohort | 41 443 | 6559 | 15.83 | 1.44 (0.60 to 2.27) |

1.10 (1.04 to 1.18) |

1.04 (0.97 to 1.11) |

44 194 | 7202 | 16.30 | 1.91 (1.07 to 2.74) |

1.13 (1.06 to 1.20) |

1.07 (1.00 to 1.14) |

| Influenza cohortd | 8269 | 1190 | 14.39 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 8269 | 1190 | 14.39 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Had cardiovascular disease | ||||||||||||

| COVID-19 cohort | 23 325 | 4901 | 21.01 | 2.79 (1.57 to 4.00) |

1.18 (1.10 to 1.27) |

1.10 (1.02 to 1.19) |

24 041 | 5115 | 21.28 | 3.05 (1.84 to 4.26) |

1.19 (1.10 to 1.28) |

1.13 (1.04 to 1.22) |

| Influenza cohortd | 4746 | 865 | 18.23 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 4746 | 865 | 18.23 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Did not have cardiovascular disease | ||||||||||||

| COVID-19 cohort | 18 118 | 1658 | 9.15 | −0.07 (−1.12 to 0.97) |

0.99 (0.87 to 1.11) |

0.91 (0.79 to 1.04) |

20 153 | 2087 | 10.36 | 1.13 (0.09 to 2.17) |

1.10 (0.98 to 1.24) |

0.97 (0.85 to 1.12) |

| Influenza cohortd | 3523 | 325 | 9.23 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 3523 | 325 | 9.23 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| All-cause 30-d mortality after primary outcome | ||||||||||||

| COVID-19 cohort | 6559 | 1482 | 22.59 | 14.70 (12.86 to 16.53) |

3.13 (2.54 to 3.87) |

3.45 (2.68 to 4.45) |

7202 | 1618 | 22.47 | 14.57 (12.76 to 16.38) |

3.09 (2.51 to 3.81) |

3.45 (2.69 to 4.44) |

| Influenza cohortd | 1190 | 94 | 7.90 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1190 | 94 | 7.90 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Secondary outcomee | ||||||||||||

| COVID-19 cohort | 41 443 | 16 671 | 40.23 | 1.67 (0.52 to 2.82) |

1.04 (1.00 to 1.08) |

1.02 (0.98 to 1.06) |

44 194 | 17 830 | 40.34 | 1.79 (0.65 to 2.94) |

1.04 (1.00 to 1.08) |

1.03 (1.00 to 1.07) |

| Influenza cohortd | 8269 | 3188 | 38.55 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 8269 | 3188 | 38.55 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Venous thromboembolism | ||||||||||||

| Primary outcomef | ||||||||||||

| COVID-19 cohort | 41 443 | 3917 | 9.45 | 4.13 (3.57 to 4.69) |

1.76 (1.60 to 1.94) |

1.60 (1.43 to 1.79) |

44 194 | 4799 | 10.86 | 5.54 (4.97 to 6.10) |

2.03 (1.84 to 2.24) |

1.89 (1.68 to 2.12) |

| Influenza cohortd | 8269 | 440 | 5.32 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 8269 | 440 | 5.32 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Had prior venous thrombotic event | ||||||||||||

| COVID-19 cohort | 3275 | 977 | 29.83 | 7.81 (4.15 to 11.47) |

1.43 (1.19 to 1.72) |

1.22 (0.98 to 1.52) |

3146 | 982 | 31.21 | 9.19 (5.51 to 12.87) |

1.47 (1.23 to 1.76) |

1.42 (1.16 to 1.74) |

| Influenza cohortd | 604 | 133 | 22.02 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 604 | 133 | 22.02 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Did not have prior venous thrombotic event | ||||||||||||

| COVID-19 cohort | 38 168 | 2940 | 7.70 | 3.70 (3.18 to 4.21) |

1.90 (1.69 to 2.14) |

1.77 (1.55 to 2.02) |

41 048 | 3817 | 9.30 | 5.29 (4.77 to 5.81) |

2.32 (2.06 to 2.60) |

2.09 (1.82 to 2.40) |

| Influenza cohortd | 7665 | 307 | 4.01 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 7665 | 307 | 4.01 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| All-cause 30-d mortality after primary outcome | ||||||||||||

| COVID-19 cohort | 3917 | 714 | 18.23 | 12.77 (10.33 to 15.22) |

3.60 (2.40 to 5.41) |

2.96 (1.84 to 4.76) |

4799 | 985 | 20.53 | 15.07 (12.66 to 17.48) |

4.10 (2.73 to 6.14) |

3.80 (2.41 to 6.00) |

| Influenza cohortd | 440 | 24 | 5.45 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 440 | 24 | 5.45 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Secondary outcomeg | ||||||||||||

| COVID-19 cohort | 41 443 | 4118 | 9.94 | 4.17 (3.59 to 4.75) |

1.72 (1.56 to 1.89) |

1.57 (1.41 to 1.75) |

44 194 | 5018 | 11.35 | 5.59 (5.00 to 6.17) |

1.97 (1.79 to 2.17) |

1.84 (1.65 to 2.06) |

| Influenza cohortd | 8269 | 477 | 5.77 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 8269 | 477 | 5.77 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

These data are not weighted.

The hazard ratios were calculated after adjustment for the 6 data sources and after development of the propensity scores with fine stratification and stratum-specific weighting.

The primary outcome was arterial thromboembolism.

The dates for the influenza cohort were October 1, 2018, through April 30, 2019.

Defined as an emergency department or hospital discharge diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, angina, transient ischemic attack, or peripheral artery disease.

The primary outcome was venous thromboembolism.

Defined as an emergency department or hospital discharge diagnosis of acute upper or lower deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or venous thrombosis of devices, implants, or grafts.

Among patients with cardiovascular disease and compared with patients with influenza, the risk of arterial thromboembolism was significantly higher for patients with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 1.10 [95% CI, 1.02-1.19]) and for patients with COVID-19 during vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 1.13 [95% CI, 1.04-1.22]) (Table 3). After experiencing the primary outcome of an arterial thrombotic event and compared with patients with influenza, 30-day all-cause mortality was significantly higher in patients with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 3.45 [95% CI, 2.68-4.45]) and in patients with COVID-19 during vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 3.45 [95% CI, 2.69-4.44]) (Table 3).

Risk of Venous Thromboembolism in Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 vs Patients Hospitalized With Influenza

The 90-day absolute risk of venous thromboembolism was 5.3% (95% CI, 4.9%-5.8%) among patients hospitalized with influenza vs 9.5% (95% CI, 9.2%-9.7%) among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (risk difference, 4.1% [95% CI, 3.6%-4.7%]) and 10.9% (95% CI, 10.6%-11.1%) among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 during vaccine availability (risk difference, 5.5% [95% CI, 5.0%-6.1%]). Within each cohort, the 90-day risk of venous thromboembolism was higher for patients who were admitted to the intensive care unit or required mechanical ventilation and in patients who had a prior venous thrombotic event (Table 2). Among patients with COVID-19, risk of venous thromboembolism was similar across the study periods (Figure and eTable 7 in the Supplement).

After development of the propensity scores with fine stratification and weighting and compared with patients with influenza, the risk of venous thromboembolism was significantly higher in patients with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 1.60 [95% CI, 1.43-1.79]) and in patients with COVID-19 during vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 1.89 [95% CI, 1.68-2.12]) (Table 3). The E-values for the point estimates were 2.58 for the period before vaccine availability and 3.19 during vaccine availability. The E-values for the lower bound of the 95% CI for these point estimates (calculated to estimate the magnitude of confounding to shift the lower bound of the 95% CI for the statistically significant results to the null) were 2.21 for the period before vaccine availability and 2.75 during vaccine availability. Associations were similar for the secondary outcome of venous thromboembolism with an emergency department or hospital discharge diagnosis of acute deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or venous thrombosis of devices, implants, or grafts in patients with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 1.57 [95% CI, 1.41-1.75]) and in patients with COVID-19 during vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 1.84 [95% CI, 1.65-2.06]).

Among patients without a history of venous thromboembolism and compared with patients with influenza, the risk of venous thromboembolism was significantly higher for patients with COVID-19 both before vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 1.77 [95% CI, 1.55-2.02]) and during vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 2.09 [95% CI, 1.82-2.40]). Among patients who had a prior venous thrombotic event and compared with patients with influenza, the risk of a subsequent venous thrombotic event was not significantly higher for patients with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 1.22 [95% CI, 0.98-1.52]) but was significantly higher for patients with COVID-19 during vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 1.42 [95% CI, 1.16-1.74]). After an inpatient venous thrombotic event and compared with influenza, all-cause 30-day mortality was higher for patients with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 2.96 [95% CI, 1.84-4.76]) and during vaccine availability (adjusted HR, 3.80 [95% CI, 2.41-6.00]) (Table 3).

Risk Factors in Persons With COVID-19

Arterial Thromboembolism

Within age- and sex-adjusted models examining risk factors associated with arterial thromboembolism, older age, male sex, and the following baseline characteristics were associated with a significantly higher risk of arterial thromboembolism: alcohol dependence or alcohol use disorder, atrial fibrillation or flutter, chronic kidney disease, COPD, diabetes, heart failure, cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, inherited thrombophilia, neurological disease, pregnancy, thrombocytosis, and recent outpatient use of an anticoagulant, antiplatelet, or statin during both COVID-19 periods; cancer was associated with a significantly lower risk of arterial thromboembolism during both COVID-19 periods (eTable 8 in the Supplement). Within the fully adjusted models, the HRs for the risk factors were attenuated (eTable 9 in the Supplement).

Venous Thromboembolism

Within age- and sex-adjusted models examining risk factors associated with venous thromboembolism, older age, male sex, and the following baseline characteristics were associated with a significantly higher risk of venous thromboembolism: antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, cancer, chronic kidney disease, COPD, heart failure, prior venous thrombotic event, inherited thrombophilia, obesity, pregnancy, thrombocytosis, and recent outpatient use of an anticoagulant during both COVID-19 periods; recent statin use was associated with a significantly lower risk of venous thromboembolism during both COVID-19 periods (eTable 8 in the Supplement). Within the fully adjusted models, the HRs for the risk factors were attenuated (eTable 9 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Using data from a US public health surveillance system, this study found that the 90-day risk of venous thromboembolism was significantly higher among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 than among patients hospitalized with influenza in 2018-2019. This association was observed for patients diagnosed with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (April-November 2020) and during vaccine availability (December 2020-May 2021). In contrast, COVID-19 was not associated with a higher 90-day risk of arterial thromboembolism compared with influenza during either COVID-19 vaccine period.

Prior studies of the association of COVID-19 with thrombosis included small, regional samples. One analysis of 3334 patients with COVID-19 admitted to 4 New York City hospitals found that 11.1% developed arterial thromboembolism and 6.2% developed venous thromboembolism during hospitalization.34 A study from 2 New York City hospitals reported that 1.6% of 1916 patients with COVID-19 and emergency department visits or hospitalizations developed ischemic stroke compared with 0.2% of 1486 patients with influenza (odds ratio, 7.6 [95% CI, 2.3-25.2]).35

There are several possible reasons for the higher risk of venous thromboembolism among patients with COVID-19 compared with influenza. SARS-CoV-2 infection of endothelial cells incites inflammation and abnormalities in coagulation, such as an increased abundance of antiphospholipid antibodies and enhanced platelet activity.36 These abnormalities might be more marked in patients with COVID-19 vs in patients with influenza infections. Alternatively, heightened awareness of thrombosis with COVID-19 might have led to a greater ascertainment of events in patients with COVID-19 after case series published early in the pandemic reported high rates of these complications.2,5,6,7,8,9,10 However, no association between COVID-19 and arterial thromboembolism was observed, which might be subject to similarly increased event ascertainment.

After an inpatient arterial or venous thrombotic event, the risk of 30-day mortality was significantly higher for patients with COVID-19 vs patients with influenza. Patients with COVID-19 may have had a higher frequency of thromboses that contributed to organ failure, multisystem injury, and death (eg, more pulmonary embolism than deep vein thrombosis) compared with patients with influenza.37,38 However, data regarding the severity of the thrombotic events were not available in this study. Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms for this observation.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, misclassification of thrombotic outcomes can occur in administrative claims data. Second, some thrombotic events and deaths might have been missed in the COVID-19 cohorts because of delays in data availability.

Third, it is possible that more testing for venous thromboembolism occurred among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 than among patients hospitalized with influenza, which may have contributed to higher rates of venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19. Fourth, data on COVID-19 or influenza immunization status were not included. Vaccination against both infections may have occurred outside health care settings and therefore be incompletely ascertained.

Fifth, the analyses used a distributed data framework in which only summary level information was shared. Therefore, the proportional hazards assumption for the HRs could not be evaluated in patients with COVID-19 and influenza. Sixth, residual confounding by unmeasured factors was possible. Data on inpatient laboratory results were limited. In addition, data on the medications administered (eg, prophylactic or therapeutic anticoagulation) within the hospital were unavailable.

Seventh, COVID-19 occurrence, detection, or severity might have been affected by factors associated with thrombosis, which may have created or altered associations between the risk factors and the outcomes (collider bias).39 Eighth, the results might not be generalizable to people without health insurance.

Conclusions

Based on data from a US public health surveillance system, hospitalization with COVID-19 before and during vaccine availability, vs hospitalization with influenza in 2018-2019, was significantly associated with a higher risk of venous thromboembolism within 90 days, but there was no significant difference in the risk of arterial thromboembolism within 90 days.

eTable 1. Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINCs) indicating SARS-CoV-2 and influenza nucleic acid tests

eTable 2. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) diagnosis codes and descriptions for influenza

eTable 3. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) diagnosis codes used to identify exclusionary diagnoses of other respiratory viruses

eTable 4. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) diagnosis codes and descriptions for conditions representing arterial thromboembolism and venous thromboembolism events

eTable 5. Additional clinical characteristics of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (April 1, 2020-November 30, 2020) and during vaccine availability (December 1, 2020-May 31, 2021) compared to those hospitalized with influenza (October 1, 2018-April 30, 2019)

eTable 6. Outpatient medications examined within specified drug classes of interest

eTable 7. 90-day absolute risk of inpatient arterial and venous thromboembolism events among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 before and during vaccine availability compared to those hospitalized with influenza

eTable 8. Age- and sex-adjusted hazard ratios for inpatient arterial and venous thromboembolism events among patients with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (April 1, 2020-November 30, 2020) and during vaccine availability (December 1, 2020-May 31, 2021)

eTable 9. Hazard ratios, adjusted for all risk factors, for inpatient arterial and venous thromboembolism events among patients with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (April 1, 2020-November 30, 2020) and during vaccine availability (December 1, 2020-May 31, 2021)

eFigure 1. Summary diagram depicting the criteria for selection, baseline period, and follow-up

eFigure 2. Selection of hospitalized patients diagnosed with COVID-19 and influenza virus infection

References

- 1.Zhang Y, Xiao M, Zhang S, et al. Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(17):e38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Samkari H, Karp Leaf RS, Dzik WH, et al. COVID-19 and coagulation: bleeding and thrombotic manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Blood. 2020;136(4):489-500. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spiezia L, Boscolo A, Poletto F, et al. COVID-19–related severe hypercoagulability in patients admitted to intensive care unit for acute respiratory failure. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(6):998-1000. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connors JM, Levy JH. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020;135(23):2033-2040. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145-147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goyal P, Choi JJ, Pinheiro LC, et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(24):2372-2374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lax SF, Skok K, Zechner P, et al. Pulmonary arterial thrombosis in COVID-19 with fatal outcome: results from a prospective, single-center, clinicopathologic case series. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(5):350-361. doi: 10.7326/M20-2566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lodigiani C, Iapichino G, Carenzo L, et al. ; Humanitas COVID-19 Task Force . Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res. 2020;191:9-14. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Middeldorp S, Coppens M, van Haaps TF, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(8):1995-2002. doi: 10.1111/jth.14888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nahum J, Morichau-Beauchant T, Daviaud F, et al. Venous thrombosis among critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e2010478. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tufano A, Rendina D, Abate V, et al. Venous thromboembolism in COVID-19 compared to non–COVID-19 cohorts: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2021;10(21):4925. doi: 10.3390/jcm10214925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwong JC, Schwartz KL, Campitelli MA, et al. Acute myocardial infarction after laboratory-confirmed influenza infection. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(4):345-353. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1702090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boehme AK, Luna J, Kulick ER, Kamel H, Elkind MSV. Influenza-like illness as a trigger for ischemic stroke. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5(4):456-463. doi: 10.1002/acn3.545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bunce PE, High SM, Nadjafi M, Stanley K, Liles WC, Christian MD. Pandemic H1N1 influenza infection and vascular thrombosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(2):e14-e17. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dimakakos E, Grapsa D, Vathiotis I, et al. H1N1-induced venous thromboembolic events? results of a single-institution case series. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(4):ofw214. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curtis LH, Weiner MG, Boudreau DM, et al. Design considerations, architecture, and use of the mini-Sentinel distributed data system. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(suppl 1):23-31. doi: 10.1002/pds.2336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cocoros NM, Fuller CC, Adimadhyam S, et al. ; FDA-Sentinel COVID-19 Working Group . A COVID-19–ready public health surveillance system: the Food and Drug Administration’s Sentinel System. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2021;30(7):827-837. doi: 10.1002/pds.5240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosati K, Jorgensen N, Soliz M, Evans BJ. Sentinel Initiative principles and policies: HIPAA and Common Rule compliance in the Sentinel Initiative. Accessed October 31, 2021. https://www.sentinelinitiative.org/sites/default/files/communications/publications-presentations/HIPAA-Common-Rule-Compliance-in-Sentinel-Initiative.pdf

- 19.US Department of Health and Human Services . Policy for protection of human research subjects, 45 CFR §46.102(l)(2).

- 20.Xu X, Blanton L, Elal AIA, et al. Update: influenza activity in the United States during the 2018-19 season and composition of the 2019-20 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(24):544-551. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6824a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cutrona SL, Toh S, Iyer A, et al. Validation of acute myocardial infarction in the Food and Drug Administration’s mini-Sentinel program. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(1):40-54. doi: 10.1002/pds.3310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ammann EM, Schweizer ML, Robinson JG, et al. Chart validation of inpatient ICD-9-CM administrative diagnosis codes for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) among intravenous immune globulin (IGIV) users in the Sentinel distributed database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018;27(4):398-404. doi: 10.1002/pds.4398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wahl PM, Rodgers K, Schneeweiss S, et al. Validation of claims-based diagnostic and procedure codes for cardiovascular and gastrointestinal serious adverse events in a commercially-insured population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(6):596-603. doi: 10.1002/pds.1924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roumie CL, Mitchel E, Gideon PS, Varas-Lorenzo C, Castellsague J, Griffin MR. Validation of ICD-9 codes with a high positive predictive value for incident strokes resulting in hospitalization using Medicaid health data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17(1):20-26. doi: 10.1002/pds.1518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yih WK, Greene SK, Zichittella L, et al. Evaluation of the risk of venous thromboembolism after quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccination among US females. Vaccine. 2016;34(1):172-178. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.09.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ammann EM, Cuker A, Carnahan RM, et al. Chart validation of inpatient International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) administrative diagnosis codes for venous thromboembolism (VTE) among intravenous immune globulin (IGIV) users in the Sentinel distributed database. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(8):e9960. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gagne JJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Levin R, Schneeweiss S. A combined comorbidity score predicted mortality in elderly patients better than existing scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(7):749-759. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Food and Drug Administration . Master protocol development: COVID-19 natural history. Accessed October 27, 2021. https://www.sentinelinitiative.org/sentinel/methods/master-protocol-development-covid-19-natural-history

- 29.Mamdani M, Sykora K, Li P, et al. Reader’s guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies, 2: assessing potential for confounding. BMJ. 2005;330(7497):960-962. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7497.960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Desai RJ, Rothman KJ, Bateman BT, Hernandez-Diaz S, Huybrechts KF. A propensity-score–based fine stratification approach for confounding adjustment when exposure is infrequent. Epidemiology. 2017;28(2):249-257. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Desai RJ, Franklin JM. Alternative approaches for confounding adjustment in observational studies using weighting based on the propensity score: a primer for practitioners. BMJ. 2019;367:l5657. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shu D, Yoshida K, Fireman BH, Toh S. Inverse probability weighted Cox model in multi-site studies without sharing individual-level data. Stat Methods Med Res. 2020;29(6):1668-1681. doi: 10.1177/0962280219869742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-value. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(4):268-274. doi: 10.7326/M16-2607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bilaloglu S, Aphinyanaphongs Y, Jones S, Iturrate E, Hochman J, Berger JS. Thrombosis in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in a New York City health system. JAMA. 2020;324(8):799-801. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.13372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Merkler AE, Parikh NS, Mir S, et al. Risk of ischemic stroke in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vs patients with influenza. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(11):1366-1372. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1417-1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levi M, Thachil J, Iba T, Levy JH. Coagulation abnormalities and thrombosis in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(6):e438-e440. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30145-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(2):120-128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Griffith GJ, Morris TT, Tudball MJ, et al. Collider bias undermines our understanding of COVID-19 disease risk and severity. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):5749. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19478-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINCs) indicating SARS-CoV-2 and influenza nucleic acid tests

eTable 2. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) diagnosis codes and descriptions for influenza

eTable 3. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) diagnosis codes used to identify exclusionary diagnoses of other respiratory viruses

eTable 4. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) diagnosis codes and descriptions for conditions representing arterial thromboembolism and venous thromboembolism events

eTable 5. Additional clinical characteristics of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (April 1, 2020-November 30, 2020) and during vaccine availability (December 1, 2020-May 31, 2021) compared to those hospitalized with influenza (October 1, 2018-April 30, 2019)

eTable 6. Outpatient medications examined within specified drug classes of interest

eTable 7. 90-day absolute risk of inpatient arterial and venous thromboembolism events among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 before and during vaccine availability compared to those hospitalized with influenza

eTable 8. Age- and sex-adjusted hazard ratios for inpatient arterial and venous thromboembolism events among patients with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (April 1, 2020-November 30, 2020) and during vaccine availability (December 1, 2020-May 31, 2021)

eTable 9. Hazard ratios, adjusted for all risk factors, for inpatient arterial and venous thromboembolism events among patients with COVID-19 before vaccine availability (April 1, 2020-November 30, 2020) and during vaccine availability (December 1, 2020-May 31, 2021)

eFigure 1. Summary diagram depicting the criteria for selection, baseline period, and follow-up

eFigure 2. Selection of hospitalized patients diagnosed with COVID-19 and influenza virus infection