Although nostalgia—a bittersweet emotion that reflects longing for days gone by—has been predominantly studied as an individual-level emotion (i.e., longing for one’s personal past; Sedikides et al., 2004), nostalgia can also be experienced in relation to the past of one’s social group (i.e., longing for the ingroup’s past; Wildschut et al., 2014), even if the past that people are nostalgic for is outside their lived experience (Smeekes et al., 2015). Importantly, the consequence of feeling this group-based emotion is a desire to re-establish the group’s past in the present. This can manifest constructively (e.g., ingroup favoring collective action; Wildschut et al., 2014) or destructively (e.g., hostile intergroup attitudes; Smeekes et al., 2015).

The key to understanding whether positive or negative outcomes of collective nostalgia prevail lies in the content of the emotion, i.e., the specific aspects of the collective past that group members long to bring back to the present (Lammers & Baldwin, 2020; Wohl et al., 2020a and b). As evidenced by Wohl et al. (2020b), the content of nostalgia is malleable: when American participants were manipulated to think of a time in America’s past that made them nostalgic for when America was more open to other cultures, they expressed more acceptance of immigrants. Conversely, when they were manipulated to nostalgize about a time in America’s past when American society was more homogenous, participants expressed less acceptance of immigrants.

The current research explored the possibility that framing a particular aspect of a group’s history as positive through a large-scale intervention should stimulate nostalgia for that aspect of the past. We hypothesized that when Poles learn about the historical co-existence with Jews during an intervention styled workshop about Jewish history in Poland, it will stimulate nostalgia for an open society and decrease nostalgia for a homogenous society. These changes in collective nostalgia should, in turn, relate to more tolerant intergroup attitudes. We also expected the intervention to stimulate participants’ knowledge of history and interest in local history. The latter of which has been shown to relate to more positive intergroup attitudes (Stefaniak et al., 2017; Wójcik et al., 2010). We expected that the positive effects of the intervention on attitudes via collective nostalgia would emerge even when including knowledge of and interest in local history in the model.

Method

Study Context

The reported study was conducted in Poland due to its unique history of intergroup relations. Post-war Poland became one of the most ethnically homogenous countries in the world with more than 96% of the population declaring a solely Polish ethnic identification (Gudaszewski, 2015), which made intergroup contact highly unlikely (Stefaniak & Bilewicz, 2016) and intergroup prejudice prevalent (Zick et al., 2011). Most recently, more than one million Ukrainian citizens settled in the country, and today immigrants consist more than 5% of the country’s population. From a historical perspective, the post-war situation was highly untypical. Being situated in the center of Europe, at the cross-roads of cultural influences and economic interests, up until World War II, many diverse ethnic groups settled in Poland.

In fact, pre-war data shows that close to a third of the Polish population at the time consisted of various ethnic minorities, with the Jewish minority being the second largest at 10.5% of the total population (Eberhardt, 2006). Even though the Jewish minority living in Poland today is very small, strong negative attitudes towards Jews persist (Bilewicz et al., 2012), also among young people (Ambrosewicz-Jacobs, 2013). Given the historic coexistence of Poles and Jews and the relative paucity of school education on this topic (Witkowska et al., 2014), the current study was conducted among a sample of Polish youth who live in small and medium size towns that used to be the home to large Jewish communities before the war and who, as part of an educational intervention, learned about the pre-war presence of Jewish minority in their current places of residence.

The intervention, entitled School of Dialogue, was designed and implemented by a Polish non-governmental organization, the Forum for Dialogue. The program comprises four workshops during which participants acquire knowledge about the Jewish heritage and culture of pre-war Poland and their influence on Polish culture, as well as about current Jewish inhabitants of the country. The main features of the program comprise the explicit focus on local Polish-Jewish history and the direct engagement with the still existing Jewish material heritage (Stefaniak et al., 2017; Stefaniak & Bilewicz, 2016). A more detailed description of the intervention may be found in the Supplementary Material.

Participants and Design

For the purpose of the current study, we recruited participants of the 2019 edition of the School of Dialogue (N = 476). It is important to note that although the decision to participate in the School of Dialogue program is made by the school officials, in some of the schools, the students volunteer to take part in the program; in others, they are selected to participate by their teachers (though they have a right not to do so). Unfortunately, how participants entered the program was not coded. As such, the extent to which self-selection into the program influences results cannot be assessed.

The participants who agreed to take part in the evaluation study were on average 14 years and 10 months old (Mage = 14.82; SD = 1.63), 61.6% identified as female, 37.4% as male, and 1.1% did not provide gender self-identification. They came from 32 different locations: 18.8% of the locations were villages, 46.9% were towns with a population up to 20,000, 21.9% were from towns with a population between 20,000 and 100,000, and 12.5% were from cities with a population over 100,000. As part of the study, the participants filled out two questionnaires—one before the start of the program and one after its completion. The participants were asked to sign their questionnaires with special codes, so that time 1 and time 2 answers could be matched. Only data from participants who completed and correctly coded both questionnaires was analyzed. The consent to participate in the study was collected verbally from participants’ parents by head teachers or school headmasters (depending on the location). Only students who agreed to participate in the study were given the questionnaires.

Measures

Measures reported as part of this study were embedded in a longer questionnaire that aimed at evaluating the effects of the intervention also on other aspects of social functioning of participant (e.g., willingness to engage in social activism in one’s local community, place attachment [Lewicka, 2005], social trust [Putnam, 2000], etc.). Unless otherwise indicated, the measures used in the study had an answer scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

Collective Nostalgia for an Open and for a Homogenous Society

The two types of collective nostalgia were measured with one item each taken from Wohl et al. (2020b). We asked participants about the extent to which they longed for times “when Poland was more ethnically diverse” and “when Poles were more culturally homogenous”.

Interest in Local History

Interest in local history was measured with three items taken from the Interest in Place History Scale (Lewicka, 2012), e.g., “I am interested in the history of my place of residence”; αt1 = .75; αt2 = .74.

Knowledge of Jewish History and Culture

To evaluate whether participants’ felt knowledgeable about Jewish culture and history, we asked them the following two questions: “How do you evaluate your own knowledge about the history of Polish Jews compared to your peers?” and “How do you evaluate your own knowledge about the culture of Polish Jews compared to your peers?”; rt1(469) = .62, p < .001; rt2(462) = .74, p < .001 (answer scale: 1 = I know a lot less; 3 = I know about the same; 5 = I know a lot more). Given that the items were strongly correlated, we created composite subjective knowledge of history scores by averaging answers to both questions.

Attitudes Towards Jews

Attitudes towards Jews were measured with a feeling thermometer that asked participants about the extent to which their feelings towards this group were negative or positive on a scale from 0 = extremely cold/negative to 100 = extremely warm/positive.

Attitudes Towards Ethnic Diversity

Attitudes towards ethnic diversity were measured with four items: “Poland should accept more refugees from countries at war,” “I wish there were more people with different skin colors living in Poland,” “Immigrants enrich Polish culture,” and “Immigrants are taking jobs away from ethnic Poles (reversed)”; αt1 = .75; αt2 = .76.

Results

Table 1 presents means, standard deviations, changes over time, and correlations among variables in the study at time 1 and time 2. Data analyzed in this article is publicly available via OSF: https://osf.io/f64qn/?view_only=205e31c28e0e4139b7cae31a1d3cd081.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, changes over time, and correlations among variables in the study

| Time 1 | Time 2 | t | d | Powera | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Openness CN | 2.77 (1.00) | 2.88 (1.05) | −2.14* | −0.11 | 0.67 | .12** | .05 | .02 | .33*** | .46*** | |

| 2. Homogeneity CN | 2.94 (1.03) | 2.79 (1.01) | 3.00** | 0.14 | 0.85 | −.06 | .12* | −.05 | −.13** | −.20*** | |

| 3. Interest in local history | 3.12 (0.77) | 3.41 (0.78) | −8.30*** | −0.39 | 1.00 | .19*** | .10* | .25*** | .12** | .09* | |

| 4. Knowledge of history | 2.95 (0.65) | 3.38 (0.78) | −11.34*** | −0.54 | 1.00 | .14** | −.12* | .21*** | .10* | −.02 | |

| 5. Feeling thermometer | 65.81 (25.11) | 69.79 (26.16) | −3.66*** | −0.17 | 0.96 | .32*** | −.07 | .21*** | .18*** | .46*** | |

| 6. Diversity | 2.87 (0.78) | 2.97 (0.79) | −4.16*** | −0.18 | 0.98 | .52*** | −.21*** | .15** | .17*** | .46*** |

CN collective nostalgia. Diversity = attitudes towards ethnic diversity. Correlations at time 1 are presented above and at time 2 below the diagonal

aObserved power, two-tailed

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05

We observed significant changes in all variables after the intervention. Specifically, upon completion of the program, the participants displayed greater nostalgia for an open society, more positive intergroup attitudes (towards Jews, and towards ethnic diversity more generally), more interest in local history, and higher subjective evaluation of their knowledge of Jewish culture and history. At the same time, participants’ nostalgia for a homogeneous society significantly decreased.

Predictably, collective nostalgia for an open society was associated with more positive attitudes towards Jewish people and towards ethnic diversity at both measurement times, while nostalgia for a homogenous society related to more negative attitudes towards Jews and towards ethnic diversity (though the latter was only significant at time 1 and not at time 2). The two types of nostalgia were positively, though not very strongly correlated at time 1, but did not correlate at time 2. Knowledge of Jewish history and culture as well as interest in local history were positively related to participants’ intergroup attitudes as well.

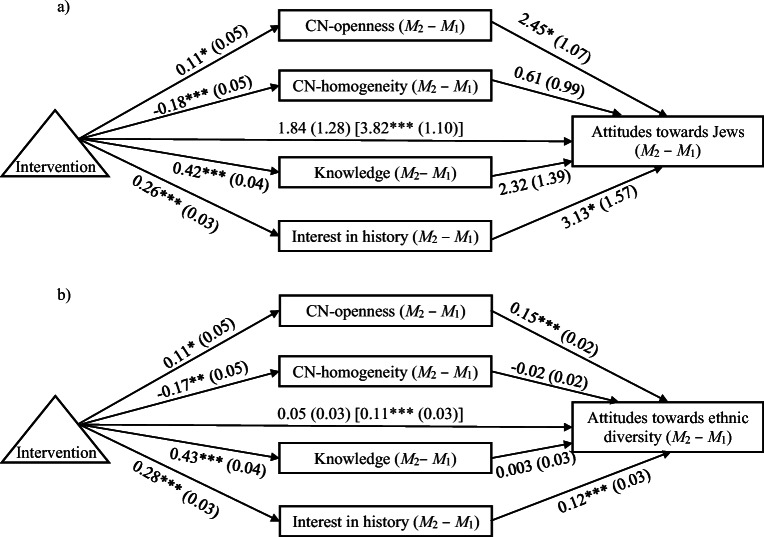

To verify the predictions that participating in the intervention will influence collective nostalgia, knowledge of history, and interest in local history and that changes in collective nostalgia will translate to participants’ intergroup attitudes, an analysis of within-participants mediation was conducted using the MEMORE macro (Montoya & Hayes, 2017). The macro is designed for testing mediational models in repeated measure designs (with two measurements) and allows for testing the relations between changes in the variables that occur over time (while controlling for the effects of average levels of the variables). Using this method, we assessed the influence of the intervention on participants’ openness-focused and homogeneity-focused collective nostalgia, interest in local history, and subjective knowledge of Jewish history as well as the influence of these changes on changes observed in attitudes towards Jews and towards ethnic diversity. The two models tested are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Within-subjects mediation of the influence of the intervention on participants’ attitudes towards Jews (a) and towards ethnic diversity (b) via changes in collective nostalgia for an open (“CN-openness”) and homogenous (“CN-homogeneity”) society, knowledge of Jewish history and culture (“Knowledge”), and interest in local history (“Interest in history”)

In both models, the effect of the intervention was significant for all mediator variables. These significant changes translated to more positive attitudes towards Jews. Specifically, both greater interest in local history and stronger nostalgia for an open society related to developing more positive attitudes towards Jews, while greater subjectively evaluated knowledge of Jewish history and lower homogeneity-focused nostalgia did not (see Fig. 1a). However, only increased openness-focused nostalgia mediated the effect of the intervention on attitudes, B = 0.27, Bps = 0.01, SE = 0.17, 95% CI 0.03, 0.78, while the indirect effects via homogeneity-focused nostalgia, B = − 0.11, Bps = − 0.004, SE = 0.17, 95% CI − 0.53, 0.20, knowledge of history, B = 0.98, Bps = 0.04, SE = 0.81, 95% CI − 0.68, 2.51, and interest in local history, B = 0.83, Bps = 0.04; SE = 0.46, 95% CI − 0.02, 1.76, were not significant.

In the model for attitudes towards ethnic diversity as the dependent variable, greater openness-focused nostalgia and interest in local history predicted more positive attitudes towards ethnic diversity, while increased knowledge and decreased homogeneity-focused nostalgia did not (see Fig. 1b). The indirect effect of the intervention on attitudes towards ethnic diversity was significant via greater openness-focused nostalgia, B = 0.02, Bps = 0.03, SE = 0.01, 95% CI 0.003, 0.04, and interest in local history, B = 0.03, Bps = 0.06, SE = 0.01, 95% CI 0.01, 0.06, while the effects via homogeneity-focused nostalgia, B = 0.005, Bps = SE = 0.004, 95% CI −0.004, 0.01, and knowledge of Jewish history, B = 0.001, Bps = 0.002, SE = 0.01, 95% CI −0.03, 0.03, were not significant.

Discussion

A longitudinal study conducted in Poland showed that participants of an intergroup intervention that provides young Poles with knowledge about the multicultural history of their places of residence developed greater nostalgia for an open society while their nostalgia for a homogenous society decreased. Participants became more interested in local history, felt more knowledgeable about Jewish history, and developed more positive attitudes towards Jews and towards ethnic diversity. Increased nostalgia for an open society mediated the effect of the intervention on both measures of intergroup attitudes. Additionally, greater interest in local history was a significant mediator of the effect of the intervention on more positive attitudes towards ethnic diversity. Neither decreased nostalgia for a homogenous society, nor feeling more knowledgeable about Jewish history emerged as significant mediators.

Although the lack of a control group,1 participants’ self-selection, and relatively small effect sizes constitute shortcomings of this research, we nonetheless believe that it provides a substantial contribution to the literature. Specifically, our results show that teaching about the history of coexistence between majority and minority groups in a naturalistic setting stimulates a sense of nostalgia for a more open society of the past and simultaneously decreases nostalgia for a homogenous society. Thus, reliable historical knowledge emerges as a possible source of nostalgia, which goes beyond the typical short instructions used to induce participants’ collective nostalgia (e.g., Lammers & Baldwin, 2020; Wohl et al., 2020b). The current research also demonstrates that collective nostalgia for an open society (alongside greater interest in local history) is a reliable mediator of the effects of learning about historical ethnic diversity on more tolerant intergroup attitudes, which contributes to the broader literature on prejudice reduction (Paluck & Green, 2009; Stefaniak & Bilewicz, 2016). Lastly, our results show that history may be utilized as a resource for building more amiable intergroup relations in contexts where lack of diversity may preclude other methods, such as direct intergroup contact (Wagner et al., 2003).

Supplementary Information

(PDF 475 kb)

Additional Information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Insight Grant (#435-2019-0692) to Wohl and NCN Sonata Bis grant (2017/26/E/HS6/00129). The authors wish to thank the Forum for Dialogue for organizing and conducting the study.

Data availability

Data reported in the article is available at: https://osf.io/f64qn/?view_only=205e31c28e0e4139b7cae31a1d3cd081.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

This study has been approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the Robert Zajonc Institute for Social Studies, University of Warsaw, Poland.

Informed Consent

The consent to participate in the study was obtained verbally from participants’ parents by head teachers/school headmasters. Only students who agreed to participate in the study were given the questionnaires.

Footnotes

In 2015, evaluation of the School of Dialogue program included a control group and showed that the effects found in the study cannot be attributed to just the passage of time or other unaccounted processes. Please see a more detailed description of that study in the Supplement and in an unpublished Ph.D. dissertation by Stefaniak (2017, Study 3). Data from that study is publicly available on OSF: https://osf.io/f64qn/?view_only=205e31c28e0e4139b7cae31a1d3cd081.

References

- Ambrosewicz-Jacobs, J. (2013). Antisemitism and attitudes towards the holocaust. Empirical studies from Poland. Antisemitism in Europe Today: The Phenomena, the Conflicts, 1–10.

- Bilewicz, M., Winiewski, M., & Radzik, Z. (2012). Antisemitism in Poland: Psychological, religious and historical aspects. Journal for the Study of Antisemitism , 4, 423–442.

- Eberhardt P. Przemiany struktury etnicznej ludności Polski w XX wieku. Sprawy Narodowościowe. 2006;28:53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gudaszewski, G. (2015). Struktura narodowo-etniczna, językowa i wyznaniowa ludności Polski [The ethno-national, linguistic, and religious structure of the Polish population] (pp. 1–256). Statistics Poland.

- Lammers J, Baldwin M. Make America gracious again: Collective nostalgia can increase and decrease support for right-wing populist rhetoric. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2020;50(5):943–954. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka M. Ways to make people active: The role of place attachment, cultural capital, and neighborhood ties. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2005;25(4):381–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2005.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka, M. (2012). Psychologia miejsca [Psychology of place]. Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar.

- Montoya AK, Hayes AF. Two-condition within-participant statistical mediation analysis: A path-analytic framework. Psychological Methods. 2017;22(1):6–27. doi: 10.1037/met0000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paluck EL, Green DP. Prejudice reduction: What works? A review and assessment of research and practice. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60(1):339–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster. 10.1145/358916.361990.

- Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., & Baden, D. (2004). Nostalgia: Conceptual issues and existential functions. In J. Greenberg, S. L. Koole, & T. Pyszczynski (Eds.), The Handbook of Experimental Existential Psychology (pp. 200–214). Guilford Press.

- Smeekes A, Verkuyten M, Martinovic B. Longing for the country’s good old days: National nostalgia, autochthony beliefs, and opposition to Muslim expressive rights. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2015;54(3):561–580. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefaniak, A. (2017). The influence of contact with a multicultural past on intergroup attitudes and civic engagement. [Ph.D., University of Warsaw]. https://depotuw.ceon.pl/handle/item/2047. Accessed 2020-12-28.

- Stefaniak A, Bilewicz M. Contact with a multicultural past: A prejudice-reducing intervention. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2016;50:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stefaniak A, Bilewicz M, Lewicka M. The merits of teaching local history: Increased place attachment enhances civic engagement and social trust. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2017;51:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.03.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner U, van Dick R, Pettigrew TF, Christ O. Ethnic prejudice in East and West Germany: The explanatory power of intergroup contact. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. 2003;6(1):22–36. doi: 10.1177/1368430203006001010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wildschut T, Bruder M, Robertson S, van Tilburg WAP, Sedikides C. Collective nostalgia: A group-level emotion that confers unique benefits on the group. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2014;107(5):844–863. doi: 10.1037/a0037760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkowska M, Stefaniak A, Bilewicz M. Stracone szanse? Wpływ polskiej edukacji o Zagładzie na postawy wobec Żydów [Foregone chances? The influence of Holocaust education in Poland on attitudes towards Jews] Psychologia Wychowawcza. 2014;5:147–159. doi: 10.5604/00332860.1123989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wohl MJA, Stefaniak A, Smeekes A. Days of future past: Concerns for the group’s future prompt longing for its past (and ways to reclaim it) Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2020;29(5):481–486. doi: 10.1177/0963721420924766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wohl MJA, Stefaniak A, Smeekes A. Longing is in the memory of the beholder: Collective nostalgia content determines the method members will support to make their group great again. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2020;91:104044. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2020.104044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wójcik A, Bilewicz M, Lewicka M. Living on the ashes: Collective representations of Polish–Jewish history among people living in the former Warsaw Ghetto area. Cities. 2010;27(4):195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2010.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zick A, Küpper B, Hövermann A. Intolerance, prejudice and discrimination: A European report. Forum Berlin: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung; 2011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 475 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Data reported in the article is available at: https://osf.io/f64qn/?view_only=205e31c28e0e4139b7cae31a1d3cd081.