Abstract

Individuals who are intelligent concerning their emotions should experience them differently. In particular, being conversant with the valence dimension that is key to emotions should reasonably result in emotional experiences that are more bipolar with respect to this dimension. Pursuant of these ideas, three studies (total N = 335) assessed emotional intelligence in ability-related terms (ability EI). The same participants also reported on their recent experiences of positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA) at work (studies 1 and 2) and/or their day-to-day emotional experiences within a daily diary protocol (study 3). Within each of these studies, ability EI moderated the relationship between experiences of PA and NA, such that the PA-NA relationship was more bipolar at higher levels of EI. These findings are discussed with respect to their implications for debates about bipolarity as well as for their value in highlighting ways in which the ability EI dimension operates.

Keywords: Emotional intelligence, Ability, Positive affect, Negative affect, Bipolarity

Individuals are thought to differ in their abilities to perceive, understand, and manage emotions, which is a construct termed emotional intelligence (EI). This construct was formally proposed in 1990, popularized in 1995, and redefined in 1997, as briefly reviewed by Barchard, Brackett, and Mestre (2016). In this area of scholarship and research, it is important to distinguish ability-related perspectives on EI (ability EI) from trait-related perspectives (trait EI), both because the two sorts of measures (performance-based versus self-reported) do not correlate highly with each other and because the correlates of each sort of approach are quite different (Joseph & Newman, 2010). In the present research, we are concerned with ability EI rather than trait EI.

There are several tests of ability EI and the reliability of these tests tends to be sufficient when total scores are used (Palmer, Gignac, Manocha, & Stough, 2005). However, evaluations of whether such individual differences matter (i.e., predict anything) have been quite discrepant. As is well-known, Goleman (1995) claimed that emotional intelligence was more important than cognitive ability in facilitating success in school, at work, and in one’s relationships, but these claims were clearly overstated (Ybarra, Kross, & Sanchez-Burks, 2014). Conversely, critics have stated that the evidence in favor of the importance of ability EI is surprisingly sparse if not disappointing (Matthews, Zeidner, & Roberts, 2012). The truth could be somewhere in the middle, but this middle has been difficult to find (Ybarra et al., 2014). Nonetheless, it would seem problematic that even advocates of ability EI have used fairly hesitant language when characterizing its manifestations in daily life (Mayer, Caruso, & Salovey, 2016).

This is surely true concerning relations between ability EI and affective well-being. In an early study using the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT), Zeidner and Olnick-Shemesh (2010) found a .08-sized correlation between ability EI scores and affective well-being levels. More recently, Di Fabio and Kenny (2016) found correlations of .01, − .04, and .04 for MSCEIT relations with positive affect (PA), negative affect (NA), and life satisfaction (LS) outcomes. Such essentially null relationships are not unique to the MSCEIT as they have been observed for other ability-based tests as well (e.g., Krishnakumar, Perera, Persich, & Robinson, in press). Thus, while correlations with affective well-being are sometimes found, they are sometimes not found, and we may need to consider next generation questions in better understanding these relationships (Fernández-Berrocal & Extremera, 2016).

One possibility is that the skills associated with EI do not have any primary role in increasing one’s well-being. Rather, malleable components of well-being will primarily be due to the circumstances of one’s life (Robinson, 2000) and EI would allow one to recognize such circumstances, and their emotional implications, with greater clarity. Consider a person with a stressful job. Higher levels of EI would facilitate recognition of such stressful circumstances, which could result in higher rather than lower levels of negative affect (Krishnakumar et al., in press). Precisely because EI involves greater insight into emotions, and the circumstances that cause them (Mayer et al., 2016), the person with higher levels of EI should experience their emotions differently, but the nature of those differences should depend on the events, conditions, and stimuli that they encounter. Engelberg and Sjöberg (2004) explore ideas of this type in the context of emotional reactivity phenomena and we explore ideas of this type with respect to the fundamental question of how experiences of positive and negative affect relate to each other.

Relations between positive and negative affect have long been of interest in psychology. Wundt, Schlosberg, and Russell, among others, developed an influential model that argues that experiences of positive and negative affect should be inversely related to each other. According to this model, that is, higher levels of PA necessarily implicate lower levels of NA and vice versa (as reviewed in Barrett & Russell, 1999). Others, including Bradburn, Tellegen, and Watson, have suggested that experiences of positive affect are essentially independent of experiences of negative affect. According to this model, one can experience all combinations of low and high positive and negative affect, such that levels of PA would essentially be non-predictive of levels of NA and vice versa (as reviewed in Reich, Zautra, & Davis, 2003). In sum, there are major questions as to whether individuals experience their positive and negative feelings in bipolar or independent manners.

Attempts to resolve such questions typically focus on questions of affect markers, measurement error, or time frame (Diener & Emmons, 1984), but the more intriguing possibility is that individuals may in fact differ in whether and how their experiences of PA and NA relate to each other (Barrett, 2006; Rafaeli, Rogers, & Revelle, 2007). Dejonckheere et al. (2018) supported this point by showing that within-person relationships between PA and NA varied from r = − .8 to r = + .2 and Rafaeli et al. (2007) supported this point by showing that individual differences in relations between PA and NA (whether bipolar or independent) displayed at least moderate levels of test-retest stability over time. Given that EI is centrally concerned with conceptions and experiences of emotional states (Joseph & Newman, 2010), it seemed quite likely that EI should play some role in moderating these patterns.

One possibility is that PA and NA would be experienced more independently at higher levels of EI. In part following from the idea that PA and NA can be linked to distinct motivational systems, Zautra and colleagues have suggested that greater PA-NA independence would be maximally informative concerning the current state of the self in the world (Reich et al., 2003; Zautra, Berkhof, & Nicolson, 2002). Affective bipolarity, by contrast, could represent attempts by the person to simplify their affective space so that processing resources are spared for other purposes (Reich et al., 2003). Consistent with this framework, Zautra and colleagues have shown that stressful events, which are posited to consume resources, sometimes shift PA-NA relations toward greater bipolarity (Zautra et al., 2002). Because cognitive and emotional resources should generally be more abundant at higher, relative to lower, levels of EI (Mayer et al., 2016), one could predict greater PA-NA independence at higher levels of EI, based this Dynamic Model of Affect (Ong, Zautra, & Finan, 2017).

This idea—that high EI could be linked to lesser bipolarity—also accords with the concept of “emotional complexity”. Briefly, there has been considerable interest in whether some individuals experience their emotions in more complex ways than others and a tendency toward mixed emotions or PA-NA co-occurrence has been one operationalization of the complexity construct (Ong et al., 2017). Hypotheses pertaining to emotional complexity have been exceedingly difficult to replicate, however. The different indices of emotional complexity do not converge in a manner suggesting a single entity (Grossmann & Ellsworth, 2017) and variables like age and culture, which are thought to relate to emotional complexity, have not exhibited consistent patterns across studies (Grossmann & Ellsworth, 2017; Grühn, Lumley, Diehl, & Labouvie-Vief, 2013; Hay & Diehl, 2011).

Given this background, there are also compelling reasons to expect the opposite sort of pattern—namely, one in which higher levels of EI are linked to higher levels of bipolarity. Emotions are typically caused by events and those events are typically polarized in affective valence. As suggested by Cacioppo and Berntson (1999), one must quickly discern whether one’s circumstances are “hospitable” or “hostile” (also see Watson, 2000). Because EI is, in part, defined in terms of veridical situational perceptions (Libbrecht & Lievens, 2010), high EI individuals should experience less confusion when determining whether current circumstances are primarily pleasant or unpleasant. Veridical situational perceptions should, in turn, give rise to feeling states are less confused or “mixed” in their emotional valence (van Harreveld, Nohlen, & Schneider, 2015). In support of this point, mixed feelings tend to be unstable and can be quickly resolved once a dominant valence has been assigned (Russell, 2017).

Further, valence (good versus bad or pleasant versus unpleasant) is a foundation upon which nearly all emotional processes are built (Russell, 2017). Because individuals with high EI levels are thought to be more expert in conceptualizing and understanding emotions (Mayer et al., 2016), such individuals should also be more expert in using the valence dimension, which is a bipolar one (Russell, 2017), to represent their feelings. Processes of this type should give rise to greater bipolarity of affective experience, just as “valence focus” (a tendency to represent one’s feelings in terms of their valence) does (Barrett, 2006).

Thus far, we have concentrated on perceptual processes and understanding, but the management facet of EI (which is more behavioral or output-oriented: Joseph & Newman, 2010), too, should be linked to greater bipolarity. This is because effective action in emotional circumstances requires resolving approach-avoidance conflicts in favor of one course of action that is neither hesitant nor conflicted (Robinson, Wilkowski, & Meier, 2008). To accomplish such functions, the person must be able to upregulate one motivational system (either approach or avoidance) while downregulating the other, particularly under circumstances in which some degree of motivational conflict is experienced (Cacioppo & Berntson, 1999; Carver, 2001). Processes of this type would also give rise to greater bipolarity (Fazio, 2000).

In sum, we hypothesized that higher levels of ability EI would be associated with higher levels of emotional bipolarity. We investigated hypotheses of this type using a recently developed ability EI measure that has performed well in both workplace (Krishnakumar, Hopkins, Szmerekovsky, & Robinson, 2016; Robinson, Persich, Stawicki, & Krishnakumar, 2019) and non-work (Krishnakumar, Perera, Hopkins, & Robinson, 2019; Robinson, Fetterman, Hopkins, & Krishnakumar, 2013) contexts and therefore seemed suited to the present studies. Of note, this measure (the NEAT: Krishnakumar et al., 2016) assesses general (or global) differences in EI somewhat better than it assesses specific emotional skills related to perception or management. We therefore concentrate on this global EI level, though do perform follow-up analyses subsequent to primary analyses. Studies 1 and 2 focused on experiences of PA and NA at work and study 3 focused on experiences of PA and NA in daily life.

Hypothesis: Participants with higher levels of ability EI will exhibit greater bipolarity in their emotional experiences.

Study 1

Study 1 focused on experiences of PA and NA within the workplace. We deemed this a good focus because workplaces are relatively well-structured as well as consistent across individuals, rendering comparisons across individuals relatively clean ones in terms of the sorts of events that individuals are encountering (Ashkanasy & Humphrey, 2011). Furthermore, this focus allowed us to examine longer-term trends in affective experience within a particular sort of context—namely, the workplace (Van Katwyk, Fox, Spector, & Kelloway, 2000). Study 1 examined PA-NA relationships among student employees and study 2 will extend the analysis to full-time employees. Hypotheses were examined using multiple regression procedures (Aiken & West, 1991) and we hypothesized that PA and NA would predict each other better at higher levels of the ability EI continuum.

Method

Participants and General Procedures

The study 1 sample consisted of student employees, who are considered an important component of the workforce (Conway & Briner, 2002). In this context, we wanted adequate (.80) power to detect regression-related effect sizes in the medium range (Cohen’s f2 = .15). An online power calculator suggested a sample size of 76 and we sought to exceed this number by about 10. Participants were 91 (56.04% female; 89.01% Caucasian; M age = 21.10) undergraduate students from a north Midwestern University in the USA who received course credit as the result of their participation. The “work experiences” study was advertised online, using the SONA participant registration software. After signing up, participants copied a link to an external website and completed the Qualtrics-programmed study. Credit was then awarded.

The study was limited to students who worked at least 20 h per week and this criterion was the focus of a gate question. Types of employment included accounting, customer service, health care, manufacturing, office management, retail, and sales. The average job tenure had been 15.4 months.

Emotional Intelligence Assessment

Ability-related variations in emotional intelligence (EI) were assessed using a version of the North Dakota Emotional Abilities Test (NEAT), which applies the situation judgment test methodology to the domain of emotional intelligence, with a special emphasis on workplace events and contexts (Krishnakumar et al., 2016). Each scenario describes a protagonist in an emotional situation (e.g., “Cassidy successfully finished a project that took months to accomplish,” “Stephan saw his co-worker struggling to a considerable extent”), which is then paired with 4 response options that differ according to whether the task involves perception, understanding, or management (Joseph & Newman, 2010). Owing to the fact that the perception and understanding tasks overlap to a considerable extent, and for the sake of efficient measurement, the understanding module was omitted and an overall EI score was calculated from performance in the perception and management tasks (Robinson et al., 2019). The perception task requires individuals to rate the extent to which a protagonist would experience 4 emotions (e.g., joy, pride, interest, relief in the case of the Cassidy situation) and the management task requires individuals to rate the effectiveness of 4 different ways of responding (e.g., “take over the co-worker’s more challenging tasks” in the case of the Stephan situation). The perception task pulls for explicit emotion knowledge and the management task pulls for implicit emotion knowledge (Joseph & Newman, 2010), both with respect to the same sorts of situational materials (Libbrecht & Lievens, 2010).

The NEAT has been extensively validated. The reliability of the test is high (around .9) and the test correlates with other ability EI tests such as the STEU and the STEM (MacCann & Roberts, 2008). Associations with general mental ability and personality are sensible and the NEAT correlates positively with outcomes such as job performance (Krishnakumar et al., 2016) and conflict management behavior (Krishnakumar et al., 2019), while correlating negatively with deviant and aggressive behavior both within and outside of the workplace (Robinson et al., 2019). The NEAT is scored using a proportion-consensus scoring system (Barchard, Hensley, & Anderson, 2013) that awards points proportional to the percentage of an expert sample who made the same rating for a particular item (e.g., the participant would receive a score of .4756 if his/her rating for a particular item was also made by 47.56% of the expert sample). Experts consist of 82 workplace leaders (CEOs, managers) with an average of 18.53 years of work experience (Robinson et al., 2019). Consistent with the idea that the NEAT primarily assesses a global factor (Krishnakumar et al., 2016), scores for the perception (M = .3326; SD = .0735; α = .91) and management (M = .2885; SD = .0616; α = .87) tasks correlated at r = .61 and we therefore computed a total score that collapsed across scenarios (M = .3105; SD = .0608; α = .92).

Job Affect

Participants completed Spector’s Job Affect Scales, which required them to indicate the frequency (1 = never; 5 = extremely often) with which they had experienced 15 markers of positive affect (e.g., cheerful, energetic: M = 3.07; SD = 0.79; α = .95) as well as 15 markers of negative affect (e.g., depressed, frustrated: M = 2.43; SD = 0.74; α = .92) in the workplace during the previous 30 days. This time frame should be optimally sensitive to stable, yet state-related, trends in one’s workplace experiences (Van Katwyk et al., 2000). In support of this point, it has been shown that variations in job affect, as captured by these scales, both respond to the circumstances of one’s job and predict concurrent workplace attitudes and behaviors (e.g., Fox, Spector, & Miles, 2001; Miles, Borman, Spector, & Fox, 2002).

Results

Primary Analyses

Individuals receiving higher ability EI scores were less prone to negative feelings on the job, r = − .27, p = .010. By contrast, in zero-order terms, the relationship between ability EI and positive feelings on the job was not significant, r = .15, p = .164. Within the sample as a whole, experiences of job positive affect were somewhat independent of experiences of job negative affect, r = − .10, p = .361.

For descriptive purposes, we then performed a median split on the EI variable. Among participants receiving lower EI scores, there was no correlation between positive and negative affect, r = .16, p = .289. By contrast, bipolarity in affective experience was evidence among participants with higher (above median) EI scores, r = − .36, p = .016.

To more formally evaluate the bipolarity hypothesis, we conducted two multiple regressions, one of which examined whether continuous variations in EI and job positive affect (JPA) interacted to predict job negative affect (JNA) and the other of which examined a possible EI by JNA interaction in predicting JPA. For both regressions, predictors were z-scored (Aiken & West, 1991) and analyses were conducted with the PROCESS macro for SAS (Hayes, 2013).

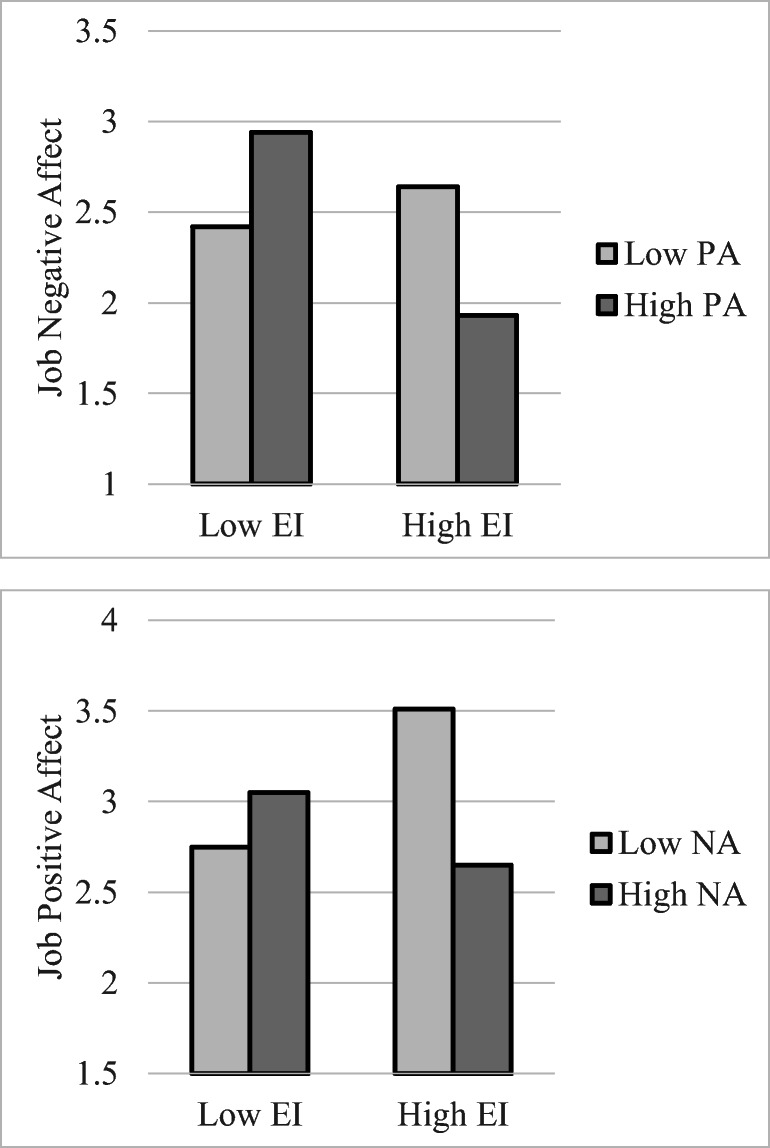

With negative affect as the outcome, there was a main effect for EI, t = − 2.92, p = .004, β = − .27, but not JPA p = .512, β = − .06, and there was also an EI by JPA interaction, t = − 4.86, p < .001, β = − .42. The top panel of Fig. 1 displays estimated means (Aiken & West, 1991) for the EI by JPA interaction as a function of low (− 1 SD) versus high (+ 1 SD) levels of each of the predictor variables. As shown there, JPA was a positive predictor of JNA at the low (− 1 SD) level of EI, t = 2.85, p = .006, β = .36, but a negative predictor of JNA at the high (+ 1 SD) level of EI, t = − 3.79, p < .001, β = − .48. The former pattern was an anomalous one that was not evident in studies 2 or 3. Therefore, what we emphasize is the latter pattern, which was consistent across studies.

Fig. 1.

Estimated means (± 1 SD) for emotional intelligence (EI) by job positive affect (PA) (top panel) and emotional intelligence (EI) by job negative affect (NA) (bottom panel) interactions, study 1

With positive affect as the outcome, effects were parallel. There was a main effect for EI, t = − 2.97, p = .004, β = − .27, but not JNA, t = − 0.68, p = .496, β = − .06, and there was also an EI by JNA interaction, t = − 5.15, p < .001, β = − .44. As shown in the bottom panel of Fig. 1, JNA exhibited a negative relationship with JPA at high (+ 1 SD) levels of EI, t = − 4.10, p < .001, β = − .50, but not at low (− 1 SD) levels of EI, t = 2.95, p = .004, β = .38. In other words, a bipolar relationship between positive and negative feelings was particular to high EI individuals.

Additional Analyses

Follow-up multiple regressions replaced the ability EI total score with perception or management scores considered alone. For the sake of parsimony, we will omit some detail while concentrating on the critical interactive patterns. Positive affect interacted with perception scores to predict negative affect, t = − 5.15, p < .001, β = − .44, and negative affect interacted with perception scores to predict positive affect, t = − 4.84, p < .001, β = − .40. In both cases, bipolarity was evident among individuals receiving high perception scores (+ 1 SD), but not among individuals receiving low perception scores (− 1 SD).

Results were parallel when the ability EI total score was replaced by management scores. That is, PA interacted with management to predict NA, t = − 3.35, p = .001, β = − .32, and NA interacted with management to predict PA, t = − 3.33, p = .001, β = − .32. Further analyses revealed that bipolarity was evident at high levels of emotion management, but not at low levels. Thus, our emphasis on what is shared by perception and management appears to be sound.

Discussion and Study 2

We have argued that higher levels of EI should promote greater “decisiveness” with respect to one’s emotional experiences. This idea was supported in terms of higher levels of bipolarity at higher levels of ability EI. (Indeed, there was no tendency toward bipolarity among low EI individuals.) Given the novelty of these findings, as well as their theoretical importance, we sought to replicate them in a second study, in this case by recruiting full-time employees, who reasonably have more extensive workplace experiences to draw upon.

Method

Participants and General Procedures

The purpose of study 2 was to determine the replicability of the study 1 pattern among full-time employees. In this context, we sought adequate (.80) power to detect effect sizes in the small-to-medium range (Cohen’s f2 = .08). An online calculator with a specific focus on multiple regression work suggested a sample size of 139. As in study 1, we sought to exceed this number by about 10.

Accordingly, we contracted with Qualtrics, who provide excellent panel recruitment services, with the goal of obtaining high-quality data from 150 full-time workers from across the USA. Eligible individuals needed to be above the age of 25, which should result in some degree of vocational stability, and we also asked for a near-equal proportion of males and females. Per contract, Qualtrics targeted users and panels who possessed the desired characteristics who were willing to contribute to research in return for modest compensation. The Qualtrics-programmed survey contained 6 gates, 2 of which ensured that participants met inclusionary criteria (e.g., age > 24) and 4 of which ensured careful attention to the survey, in the form of attention checks. We received data for 150 individuals who passed all attention checks, but 3 completed the survey in less than 10 min, which was deemed too fast. After dropping these individuals, the final sample size was 147.

The sample was balanced with respect to sex (48.85% female) as well as diverse with respect to race (71% Caucasian, 12.98% African American, 9.16% Hispanic, 4.58% Asian American) and geographic location (42 states). The average employee was in his/her early 40s (M age = 42.78), worked 43.49 h per week, and had an average annual salary of $61,078. Jobs encompassed a number of fields such as accounting, caregiving, and facilities management.

Emotional Intelligence Assessment

Individual differences in ability EI were again assessed with the perception (M = .3501; SD = .0569; α = .84) and management (M = .2849; SD = .0584; α = .86) tasks of the NEAT, which, together, can be used to define a global EI factor (Krishnakumar et al., 2016; Robinson et al., 2019). In support of this idea, perception and management scores were strongly correlated, r = .53, and the overall EI score was highly reliable (M = .3175; SD = .0503; α = .89).

Job Affect

As in study 1, employees reported on the frequency (1 = never; 5 = extremely often) with which they had experienced 15 positive feelings (e.g., cheerful, energetic: M = 3.49; SD = 1.01, α = .96) at work, over the previous 30 days (Van Katwyk et al., 2000). They also reported on their experiences of job negative affect with respect to 15 negative feeling markers (e.g., depressed, frustrated: M = 2.11; SD = 0.98; α = .95) and the same 30-day time frame (Van Katwyk et al., 2000).

Results

Primary Analyses

Correlations among the measures indicated that emotionally intelligent employees experienced lower levels of job negative affect (JNA), r = − .30, p < .001, but not job positive affect (JPA), r = − .05, p = .519. Perhaps because employees had a better sense of whether they liked their jobs or not, relative to the part-time workers of study 1, there was also a significant JNA-JPA correlation, r = − .30, p < .001.

To obtain a descriptive sense of whether the JNA-JPA relationship varied by emotional intelligence, we performed a median split on the EI variable. At lower levels of EI, the relationship between JNA and JPA was not significant, r = − .17, p = .144. At higher levels of EI, by contrast, it was, r = − .49, p = .001. These descriptive results replicate study 1.

For inferential purposes, though, it is better to treat EI as a continuum. Accordingly, we followed up initial analyses by performing two multiple regressions, one of which examined whether EI interacted with JPA to predict JNA and the other of which examined whether EI interacted with JNA to predict JPA. As in study 1, predictors were z-scored and analyses were conducted with the PROCESS procedures of Hayes (2013).

With negative affect as the outcome, there were main effects for EI, t = − 4.43, p < .001, β = − .33, and JPA, t = − 4.20, p < .001, β = − .31, and the EI by JPA interaction was also significant, t = − 3.18, p = .007, β = − .18. Consistent with the estimated means (± 1 SD) displayed in the top panel of Fig. 2, positive affect was a significant predictor of negative affect at a high (+ 1 SD) level of emotional intelligence, t = − 5.04, p < .001, β = − .49, but not at a low (− 1 SD) level of emotional intelligence, t = − 1.36, p = .177, β = − .13.

Fig. 2.

Estimated means (± 1 SD) for emotional intelligence (EI) by job positive affect (PA) (top panel) and emotional intelligence (EI) by job negative affect (NA) (bottom panel) interactions, study 2

We deemed it important to replicate this pattern with positive affect as the outcome variable. In this multiple regression, there was a main effect for JNA, t = − 5.05, p < .001, β = − .41, but not EI, t = − 1.33, p = .186, β = − .11. Of more importance, the EI by JNA interaction was significant, t = − 3.55, p < .001, β = − .26. Consistent with the estimated means displayed in the bottom panel of Fig. 2, there was an inverse relationship between JNA and JPA at a high (+ 1 SD) level of the EI continuum, t = − 5.52, p < .001, β = − .67, but not at a low (− 1 SD) level of the EI continuum, t = − 1.60, p = .113, β = − .15.

Additional Analyses

In follow-up analyses, we replaced the total EI score with perception or management scores considered alone. The management branch interacted with JPA to predict JNA, t = − 2.31, p = .023, β = − .15, and with JNA to predict JPA, t = − 3.81, p < .001, β = − .25. The perception branch did not interact with JPA to predict JNA, t = − 1.64, p = .103, β = − .12, and the perception branch did not interact with JNA to predict JPA, t = − 1.98, p = .050, β = − .15, though patterns were similar. Nonetheless, these follow-up analyses hint at the possibility that bipolarity may follow from management to a greater extent than it follows from perception, implicating action-oriented processes (Joseph & Newman, 2010) in this connection.

Discussion and Study 3

Whereas studies 1 and 2 focused on affective experiences within the workplace, it seemed important to extend our analysis to daily emotional states more generally. Through the use of a daily diary design, we could also tackle the important question of whether links between ability EI and bipolarity can be found using a within-subject design. This is an important question because within-person relationships between PA and NA often exhibit a greater degree of bipolarity than is true concerning time-aggregated reports (Scollon, Diener, Oishi, & Biswas-Diener, 2005), which were the focus of studies 1 and 2. Following Scollon et al. (2005) and others (e.g., Schmukle, Egloff, & Burns, 2002), we expected some degree of within-subject bipolarity among nearly all participants. Following theorizing, nonetheless, we expected that this more momentary type of bipolarity would be more pronounced at higher levels of EI. In other words, the daily feelings of high EI individuals would display greater “decisiveness” in differentiating good (high PA, low NA) versus bad (high NA, low PA) days.

Method

Participants and General Procedures

The daily diary study is an example of a multilevel data structure in which multiple days are nested within particular individuals. Such designs are powerful, especially to the extent that the investigator aims for at least 900 observations (Scherbaum & Ferreter, 2009). We aimed to exceed this figure by several 100 and ultimately ended up with 1244 daily reports.

An initial sample of 150 undergraduates from a north Midwestern University signed up for a Daily Diary Study using a SONA-based platform. Following informed consent, participants were given subject numbers and asked to complete daily diary reports for 14 days in a row. To facilitate compliance with the protocol, we provided daily email reminders that were paired with subject number information and links to a secure website. Reports needed to be completed between 7 p.m. and 9 a.m. the next morning or they were considered missing. Ultimately, 137 participants provided at least 9 daily reports, which was an a priori criterion for inclusion in subsequent portions of the study.

Following the 2 weeks of daily surveys, we emailed participants again and asked them to complete a scenario inference test (the NEAT) for additional credits. We obtained responses to this Qualtrics-programmed Internet survey from 97 participants (69.07% female; 92.78% Caucasian; M age = 18.99) who constituted the final sample. The 97 participants completed 1244 daily reports and the average participant completed 12.82 of them (range 9–14).

Emotional Intelligence Assessment

Although the scenarios of the NEAT reference the workplace, the NEAT’s utility is not limited to workplace samples. Rather, the sorts of themes described in the test (e.g., success, failure, interpersonal concerns) are universal themes and the emotions that are targeted occur both inside and outside the workplace (Krishnakumar et al., 2016; Robinson et al., 2013). Hence, the NEAT can be considered a general-purpose ability EI test as well as one that can be used with workplace samples (Krishnakumar et al., 2019). Following this logic, study 3 participants completed the same test completed in studies 1 and 2. Once again, perception (M = .3668; SD = .0694; α = .88) and management (M = .3082; SD = .0438; α = .76) scores were highly correlated, r = .51, and we therefore computed a total score to assess EI in its most general and reliable terms (M = .3375; SD = .0496; α = .89).

Daily Affect

Studies 1 and 2 assessed positive and negative feelings within the workplace and study 3 sought to assess similar feelings within daily life more generally. The relevant probes needed to be brief, though, to mitigate respondent fatigue, given that these surveys were completed for 14 days in a row. Daily positive affect was assessed with two markers from the PANAS (Watson, 2000) that have worked well in previous daily diary studies (e.g., Moeller, Nicpon, & Robinson, 2014). In specific terms, participants indicated whether (1 = not at all; 4 = very much) they felt excited and enthusiastic on each day and we averaged across these markers to quantify daily PA (M = 2.62; SD = 0.90; α = .92, with day as the unit of analysis). Daily negative affect (or NA) was quantified similarly. In this case, participants indicated whether (1 = not at all; 4 = very much) they felt distressed and nervous on each day of the survey, which are general upset markers from the PANAS (Moeller et al., 2014; Watson, 2000: M = 1.87; SD = 0.78; α = .63).

Results

Primary Analyses

We conducted a series of multilevel model (MLM) analyses to examine within- and between-person relationships involving positive and negative affect. Within these analyses, within-person predictors were person-centered (Enders & Tofighi, 2007) and the between-person predictor of ability EI was z-scored (Aiken & West, 1991). All analyses were conducted using the PROC MIXED procedure of SAS (Singer, 1998) and intercepts and slopes were allowed to vary randomly, in accordance with a central interest in individual differences.

In single-predictor models, ability EI did not predict average levels of positive affect (PA), b = .070, t = 1.32, p = .189, or negative affect (NA), b = .051, t = 1.01, p = .313. Thus, the skills involved in ability EI do not necessarily generate happiness in the absence of relevant events. By contrast, within-person relationships between positive and negative affect often display a great deal of bipolarity (Scollon et al., 2005; Yik, 2007) and we expected this to be true in the present study as well. In support of this idea, daily PA levels were a strong predictor of daily NA levels, b = − .160, t = − 6.74, p < .001, and daily NA levels were a strong predictor of daily PA levels, b = − .181, t = − 6.59, p < .001. In other words, days that were “good” ones tended to produce both greater PA and lesser NA, relative to days that were “bad” ones.

Having considered single-predictor models, we next sought to characterize individual differences in bipolarity, first using a largely descriptive method. For each participant, we computed a within-subject correlation reflecting the magnitude of the PA-NA correlation, with days as the unit of analysis. The magnitude of this PA-NA correlation correlated with EI levels, r = − .23, p = .023, and a median split on the EI variable produced descriptive statistics that were fairly similar to study 2. Among participants with low (below median) NEAT scores, the average PA-NA coefficient was − .15. By contrast, among participants with high (above median) NEAT scores, the average PA-NA coefficient was − .32. These results encourage more formal analyses.

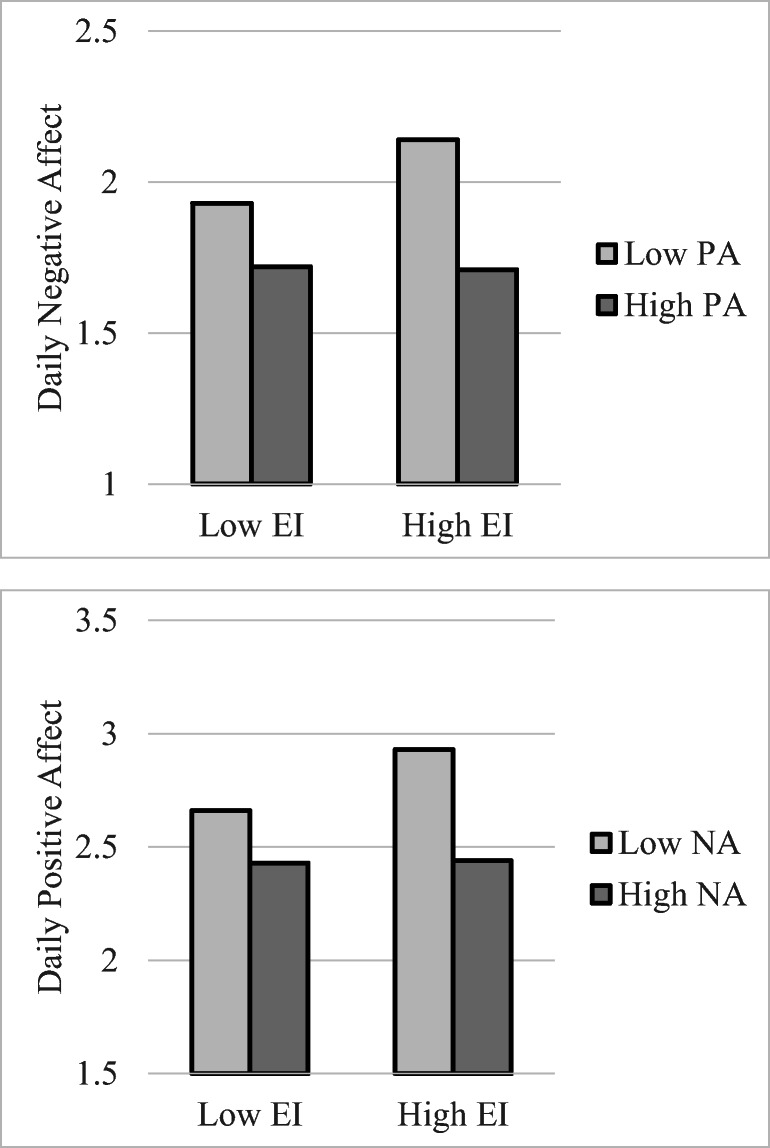

Accordingly, we returned to the larger data set with 1244 rows and performed two cross-level (Singer, 1998) analyses, one in which ability EI and daily PA levels were treated as interactive predictors of daily NA. In this analysis, there was no main effect for EI, b = .051, t = 1.01, p = .313, but there was a main effect for daily PA levels, b = − .160, t = − 6.91, p < .001, and there was also an ability EI by daily PA interaction, b = − .057, t = − 2.44, p = .015. Estimated means for the interaction, which were computed as a function of low (− 1 SD) versus high (+ 1 SD) levels of the predictor variables, are shown in the top panel of Fig. 3. Although within-person bipolarity was evident at both low, b = − .103, t = − 3.12, p = .002, and high, b = − .218, t = − 6.59, p < .001, levels of ability EI, greater bipolarity was evident at higher levels of EI.

Fig. 3.

Estimated means (± 1 SD) for emotional intelligence (EI) by daily positive affect (PA) (top panel) and emotional intelligence (EI) by daily negative affect (NA) (bottom panel) interactions, study 3

Results were parallel in a model in which the predictor was daily NA and the outcome was daily PA. In this analysis, there was no main effect for ability EI, b = .017, t = 1.32, p = .189, but there was a main effect for daily NA, b = − .181, t = − 6.77, p < .001, as well as an EI by daily NA interaction, b = − .067, t = − 2.48, p = .013. As evident in the bottom panel of Fig. 3, daily NA levels were a stronger predictor of daily PA levels at a high (+ 1 SD) level of ability EI, b = − .248, t = − 6.51, p < .001, than at a low (− 1 SD) level of ability EI, b = − .114, t = − 2.99, p = .003. These findings conceptually replicate those of studies 1 and 2, but in the context of more dynamic relationships among PA and NA.

Additional Analyses

In a series of follow-up analyses, we replaced total EI scores with perception or management scores considered alone. The skills assessed by the perception task interacted with daily PA levels to predict daily NA levels, b = − .048, t = − 2.02, p = .044, and also interacted with daily NA levels to predict daily PA levels, b = − .055, t = − 1.99, p = .047. Similarly, the skills assessed by the management task interacted with daily PA levels to predict daily NA, b = − .054, t = − 2.29, p = .022, and with daily NA levels to predict daily PA, b = − .065, t = − 2.41, p = .016. These results implicate skills common to both perception and management—namely, EI in total (Mayer et al., 2016).

Discussion

The purpose of study 3 was to examine within-person (cross-day) relationships involving positive and negative affect. In line with past research (Scollon et al., 2005), such relationships were consistently bipolar in state-related analyses. Even so, the magnitude of this bipolarity was higher at higher levels of ability EI. Such results extend studies 1 and 2 and support general conclusions concerning an affective signature (bipolarity) of the ability EI continuum.

General Discussion

Three studies demonstrated that the relationship between experiences of positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA) systematically varied across the ability EI continuum. Consistent with an “emotional decisiveness” framework, individuals with high EI levels consistently demonstrated a bipolar relationship between their PA and NA (rs = − .36, − .49, and − .32 in studies 1, 2, and 3, respectively). This was less true of individuals with low EI, who tended not to display bipolarity or displayed it to a much lesser extent (rs = .16, − .17, and − .15 in studies 1, 2, and 3, respectively). Thus, a tendency toward bipolar experiences systematically increased with ability EI levels and this was true in all three studies.

Moreover, we emphasize the generalizability of the present findings in that the same increases in bipolarity with EI were shown among student employees, full-time employees, and students going about their daily lives. Also, the findings occurred regardless of whether participants were reporting on long-aggregated emotions or not, on their feelings within a specific locale (work) or not, and with respect to both between-subject (studies 1 and 2) and within-subject (study 3) analyses. The latter is an important inclusion because relations between PA and NA can systematically vary depending on the between/within distinction (Scollon et al., 2005) and within-person analyses control for numerous third variables such as response style and stable life circumstances, which should have little impact on within-person associations (Watson, 2000). In the remainder of the “General Discussion” section, we systematically address questions, implications, and future directions.

Implications, Limitations, and Future Directions

In attempting to discover the correlates and consequences of emotional intelligence, researchers often ask questions such as whether EI is associated with higher levels of affective well-being or lower levels of depression, in bivariate or zero-order terms. Although these are good questions to ask, they may miss the important point that ability-related variations in EI are likely to operate in a more dynamic or process-oriented manner (Ybarra et al., 2014). In this connection, EI might not compel the person to experience positive emotions when current circumstances are not conducive to them (in contrast to positive illusions or self-deception). Even so, possessing higher levels of EI should change the manner in which situations are perceived, evaluations are assigned, experiences relate to each other, and decision-making processes and behaviors occur. In the analysis that follows, we offer thoughts consistent with the current data while noting that many of these thoughts would benefit from further research.

Ability EI is assessed by presenting individuals with different stimuli and asking them to assign emotional meanings to such stimuli. Because the stimuli differ from each other in their emotional meanings, doing well on such tests requires an ability to make emotional distinctions. Considered in this light, higher levels of ability EI should be linked to something like situational flexibility or malleability, particularly with respect to evaluative components of meaning (Engelberg & Sjöberg, 2004). Such processes should further align themselves with something like need for evaluation (Jarvis & Petty, 1996) or “valence focus,” which is defined in terms of the greater use of an emotional valence dimension (pleasant versus unpleasant) when organizing emotional experiences (Barrett, 2006). Consistent with this possibility, valence focus has been linked to superior abilities to decode emotional stimuli (Barrett & Niedenthal, 2004), which can be considered a component of emotional intelligence (Joseph & Newman, 2010).

Further, a focus on valence should systematically alter relationships among one’s positive and negative emotions. Specifically, since valence is a bipolar dimension (pleasant versus unpleasant), greater use of this dimension should result in emotional experiences that are more bipolar (Rafaeli et al., 2007). Thus, in answer to the perennial question of whether PA and NA are independent or bipolar (Barrett & Russell, 1999), the answer should be “it depends”. While low EI individuals may experience their positive and negative feelings in relatively independent (uncorrelated) terms, high EI individuals should tend toward bipolarity. That low versus high EI individuals differ in this manner was a key contribution of the present studies.

These findings have important implications for thinking about whether independence or bipolarity is the more functional pattern. On the basis of interesting ideas but less compelling data, some scholars have suggested that independence of the positive and negative emotional systems should support something like emotional sophistication or wisdom (for a review, see Hay & Diehl, 2011). For example, a person experiencing both positive and negative affect might be able to use their positive affect to counter some of the negative consequences of their negative affect (Folkman, 2008). Aside from empirical difficulties with this framework (Grossmann & Ellsworth, 2017; Hay & Diehl, 2011), there are theoretical difficulties as well because mixed emotions (experiencing both PA and NA at the same time) will necessarily create difficulties for self-regulation systems, which require clarity concerning whether approach or avoidance is the better course of action (Carver, 2001). In support of this point, mixed emotions have been linked to goal conflict (Berrios, Totterdell, & Kellett, 2015) as well as confusion and indecisiveness (Russell, 2017; van Harreveld et al., 2015).

By contrast, the bipolarity observed at higher levels of EI should be linked to a number of advantages. If positive and negative affect operate in incompatible ways (Fredrickson, 2004), greater bipolarity should reduce problematic cross-talk among underlying systems. Further, given that emotions have been shown to facilitate decision-making (Adolphs & Damasio, 2001), greater bipolarity should, on average, result in better decisions (van Harreveld et al., 2015). And, given that positive and negative affect are manifestations of key systems related to approach and avoidance (Carver, 2001), greater bipolarity should give rise to self-regulatory actions that are less conflicted (Cacioppo & Berntson, 1999). For example, the data of studies 1 and 2 suggest that high EI employees may have a better sense of whether they enjoy their jobs (high PA, low NA) or not (low PA, high NA). Such emotional profiles should help individuals to decide whether to further invest themselves in their current jobs or, alternatively, seek employment elsewhere (Rich, LePine, & Crawford, 2010). Thus, the current findings suggest a number of interesting directions for future research.

Among such future directions are the following. Study 3 employed a daily diary design, but it would also be informative to know whether higher EI individuals display more bipolarity in momentary experiences, as can be examined in experience-sampling studies (Scollon et al., 2005). Furthermore, we have focused on bipolarity, but there are other structural properties of emotion, too, such as the degree to which individuals display differentiation or “granularity” by distinguishing among like-valenced emotional states (e.g., sadness versus anger: Smidt & Suvak, 2015). It is intuitive to think that higher levels of EI would be linked to higher levels of granularity, but early tests of this idea have not resulted in expected findings (MacCann et al., 2020).

In linking EI to bipolarity, we have suggested that bipolarity is consistent with greater evaluative clarity or certainty (van Harreveld et al., 2015). Such processes can be examined with respect to attitudinal measures in addition to emotion-based measures (Schneider & Schwarz, 2017) and it seems probable that emotional intelligence would relate to key features of attitudes such as how quickly they are formed, how strongly they are held, and how consistent they are over time or across different attitudinal components (Fazio, 2000). In specific terms, high EI individuals should be less prone to attitudinal ambivalence, which occurs when one endorses both positive and negative evaluations concerning an attitude object (van Harreveld et al., 2015).

Similarly, the present results suggest that high EI individuals may be less prone to “mixed emotions,” which occur when one feels both positive affect and negative affect at the same time (Larsen & McGraw, 2014). Mixed emotions can be induced through the use of music clips, pictures, or film clips, but mixed emotions also occur in response to naturalistic events such as a graduation or the end of a problematic relationship (Larsen & McGraw, 2014). With respect to the latter personal events, in particular, we suggest that high EI individuals might be more capable of downregulating one set of meanings (e.g., negative ones) in favor of greater bipolarity. Research of this type would be particularly valuable in the context of longitudinal designs.

Another interesting question is whether high EI individuals might benefit from positive interventions to a greater extent than low EI individuals do. Positive interventions include activities such as counting blessings, affirming important values, and performing acts of kindness (Layous, Chancellor, & Lyubomirsky, 2014), or more formal clinician-guided treatments (Craske et al., 2019). Such interventions increase positive affect, which one might expect, but they also decrease levels of felt stress, distress, and depression (Craske et al., 2019; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). The present results suggest that the latter reductions in negative affect might be more pronounced among individuals with higher EI levels, precisely because of their greater tendencies toward bipolarity.

Returning to an earlier puzzle, we know that relationships between ability EI and health or well-being are somewhat modest (Martins, Ramalho, & Morin, 2010) and/or are in need of greater clarity (Fernández-Berrocal & Extremera, 2016). A possibility suggested by the present data is that high EI individuals could be both happier (greater PA, lesser NA) and unhappier (greater NA, lesser PA), depending on the circumstances. That is, many important predictors of well-being—such as the state of one’s employment or relationships—may predict health and well-being more strongly at higher levels of EI than at lower levels of EI and well-being levels, too, may be more variable at higher levels of the EI continuum. Research investigating such predictions would honor the idea that EI is likely to operate in “dynamic,” or situation-contingent, terms (Engelberg & Sjöberg, 2004; Ybarra et al., 2014).

Conclusions

The correlates of ability EI will almost certainly be different than the correlates of self-report measures (Joseph & Newman, 2010) and we have provided new insights into the manner in which ability EI shapes relationships among one’s positive and negative emotions. Ability EI probably plays a larger role in attuning individuals to their affective environments than in supporting well-being, per se, and the current results are consistent with line of thinking. Future research should build on the present findings in exploring their self-regulatory implications.

Additional Information

Data Availability

The datasets pertinent to the present project can be found at the following OSF repository web address: https://osf.io/8wzrk/?. None of these studies was preregistered.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The studies were approved by our institutional IRB.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained.

Authors’ Contribution

All authors contributed to the designs and analyses of these studies. The first author wrote the paper, the second author played a key role in revision efforts, the third author conducted study 3, and the fourth author contributed to analyses as well as paper preparation.

References

- Adolphs R, Damasio AR. The interaction of affect and cognition: A neurobiological perspective. In: Forgas JP, editor. Handbook of affect and social cognition. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. pp. 27–49. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ashkanasy NM, Humphrey RH. Current emotion research in organizational behavior. Emotion Review. 2011;3:214–224. [Google Scholar]

- Barchard KA, Brackett MA, Mestre JM. Taking stock and moving forward: 25 years of emotional intelligence research. Emotion Review. 2016;8:289. [Google Scholar]

- Barchard KA, Hensley S, Anderson E. When proportion consensus scoring works. Personality and Individual Differences. 2013;55:14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF. Valence is a basic building block of emotional life. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40:33–55. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF, Niedenthal PM. Valence focus and the perception of facial affect. Emotion. 2004;4:266–274. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.4.3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF, Russell JA. The structure of affect: Controversies and emerging consensus. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1999;8:10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Berrios R, Totterdell P, Kellett S. Investigating goal conflict as a source of mixed emotions. Cognition and Emotion. 2015;29:755–763. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2014.939948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Berntson GG. The affect system: Architecture and operating characteristics. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1999;8:133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. Affect and the functional bases of behavior: On the dimensional structure of affective experience. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2001;5:345–356. [Google Scholar]

- Conway N, Briner RB. Full-time versus part-time employees: Understanding the links between work status, the psychological contract, and attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2002;61:279–301. [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Meuret AE, Ritz T, Treanor M, Dour H, Rosenfield D. Positive affect treatment for depression and anxiety: A randomized clinical trial for a core feature of anhedonia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2019;87:457–471. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejonckheere E, Mestdagh M, Houben M, Erbas Y, Pe M, Koval P, et al. The bipolarity of affect and depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2018;114:323–341. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio A, Kenny ME. Promoting well-being: The contribution of emotional intelligence. Frontiers in Psychology. 2016;7:ArtID: 1182. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA. The independent of positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;47:1105–1117. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.47.5.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Tofighi D. Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:121–138. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelberg E, Sjöberg L. Emotional intelligence, affect intensity, and social adjustment. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;37:533–542. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio RH. Accessible attitudes as tools for object appraisal: Their costs and benefits. In: Maio GR, Olson JM, editors. Why we evaluate: Functions of attitudes. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Berrocal P, Extremera N. Ability emotional intelligence, depression, and well-being. Emotion Review. 2016;8:311–315. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S. The case for positive emotions in the stress process. Anxiety, Stress & Coping: An International Journal. 2008;21:3–14. doi: 10.1080/10615800701740457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox S, Spector PE, Miles D. Counterproductive work behavior (CWB) in response to job stressors and organizational justice: Some mediator and moderator tests for autonomy and emotions. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2001;59:291–309. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson B. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 2004;359:1367–1377. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goleman D. Emotional intelligence. New York, NY: Bentam Books; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann I, Ellsworth PC. What are mixed emotions and what conditions foster them? Life-span experiences, culture and social awareness. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 2017;15:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Grühn D, Lumley MA, Diehl M, Labouvie-Vief G. Time-based indicators of emotional complexity: Interrelations and correlates. Emotion. 2013;13:226–237. doi: 10.1037/a0030363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay EL, Diehl M. Emotion complexity and emotion regulation across adulthood. European Journal of Ageing. 2011;8:157–168. doi: 10.1007/s10433-011-0191-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis WBG, Petty RE. The need to evaluate. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:172–194. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph DL, Newman DA. Emotional intelligence: An integrative meta-analysis and cascading model. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2010;95:54–78. doi: 10.1037/a0017286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnakumar S, Hopkins K, Szmerekovsky JG, Robinson MD. Assessing workplace emotional intelligence: Development and validation of an ability-based measure. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied. 2016;150:371–404. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2015.1057096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnakumar S, Perera B, Hopkins K, Robinson MD. On being nice and effective: Work-related emotional intelligence and its role in conflict resolution and interpersonal problem-solving. Conflict Resolution Quarterly. 2019;37:147–167. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnakumar, S., Perera, B., Persich, M. R., & Robinson, M. D. (in press). Affective and effective: Military job performance as a function of work-related emotional intelligence. International Journal of Selection and Assessment.

- Larsen JT, McGraw AP. The case for mixed emotions. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2014;8:263–274. [Google Scholar]

- Layous K, Chancellor J, Lyubomirsky S. Positive activities as protective factors against mental health conditions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2014;123:3–12. doi: 10.1037/a0034709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libbrecht N, Lievens F. Validity evidence for the situational judgment test paradigm in emotional intelligence measurement. International Journal of Psychology. 2010;47:438–447. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2012.682063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCann C, Erbas Y, Dejonckheere E, Minbashian A, Kuppens P, Fayn K. Emotional intelligence relates to emotions, emotion dynamics, and emotion complexity: A meta-analysis and experience sampling study. European Journal of Personality Assessment. 2020;36:460–470. [Google Scholar]

- MacCann C, Roberts RD. New paradigms for assessing emotional intelligence: Theory and data. Emotion. 2008;8:540–551. doi: 10.1037/a0012746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins A, Ramalho N, Morin E. A comprehensive meta-analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence and health. Personality and Individual Differences. 2010;49:554–564. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews G, Zeidner M, Roberts RD. Emotional intelligence: A promise unfulfilled? Japanese Psychological Research. 2012;54:105–127. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer JD, Caruso DR, Salovey P. The ability model of emotional intelligence: Principles and updates. Emotion Review. 2016;8:290–300. [Google Scholar]

- Miles DE, Borman WE, Spector PE, Fox S. Building an integrative model of extra role work behaviors: A comparison of counterproductive work behavior with organizational citizenship behavior. International Journal of Selection and Assessment. 2002;10:51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller SK, Nicpon CG, Robinson MD. Responsiveness to the negative affect system as a function of emotion perception: Relations between affect and sociability in three daily diary studies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2014;40:1012–1023. doi: 10.1177/0146167214533388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Zautra AJ, Finan PH. Inter- and intra-individual variation in emotional complexity: Methodological considerations and theoretical implications. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 2017;15:22–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer BR, Gignac G, Manocha R, Stough C. A psychometric evaluation of the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test Version 2.0. Intelligence. 2005;33:285–305. [Google Scholar]

- Rafaeli E, Rogers GM, Revelle W. Affective synchrony: Individual differences in mixed emotions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;33:915–932. doi: 10.1177/0146167207301009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich JW, Zautra AJ, Davis M. Dimensions of affect relationships: Models and their integrative implications. Review of General Psychology. 2003;7:66–83. [Google Scholar]

- Rich BL, LePine JA, Crawford ER. Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal. 2010;53:617–635. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD. The reactive and prospective functions of mood: Its role in linking daily experiences and cognitive well-being. Cognition and Emotion. 2000;14:145–176. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, Fetterman AK, Hopkins K, Krishnakumar S. Losing one’s cool: Social competence as a novel inverse predictor of provocation-related aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2013;39:1268–1279. doi: 10.1177/0146167213490642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, Persich MR, Stawicki C, Krishnakumar S. Deviant workplace behavior as emotional action: Discriminant and interactive roles for work-related emotional intelligence. Human Performance. 2019;32:201–219. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, Wilkowski BM, Meier BP. Approach, avoidance, and self-regulatory conflict: An individual differences perspective. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2008;44:65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Russell JA. Mixed emotions viewed from the psychological constructionist perspective. Emotion Review. 2017;9:111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Scherbaum CA, Ferreter JM. Estimating statistical power and required sample sizes for organizational research using multilevel modeling. Organizational Research Methods. 2009;12:347–367. [Google Scholar]

- Schmukle SC, Egloff B, Burns LR. The relationship between positive and negative affect in the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule. Journal of Research in Personality. 2002;36:463–475. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider IK, Schwarz N. Mixed feelings: The case of ambivalence. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 2017;15:39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Scollon CN, Diener E, Oishi S, Biswas-Diener R. An experience sampling and cross-cultural investigation of the relation between pleasant and unpleasant affect. Cognition and Emotion. 2005;19:27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sin NL, Lyubomirsky S. Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65:467–487. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD. Using SAS PROC MIXED to fit multilevel models, hierarchical models, and individual growth models. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1998;23:323–355. [Google Scholar]

- Smidt KE, Suvak MK. A brief, but nuanced, review of emotional granularity and emotion differentiation research. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2015;3:48–51. [Google Scholar]

- van Harreveld F, Nohlen HU, Schneider IK. You shall not always get what you want: The consequences of ambivalence toward desires. In: Hofmann W, Nordgren L, editors. The psychology of desire. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2015. pp. 267–285. [Google Scholar]

- Van Katwyk PT, Fox S, Spector PE, Kelloway EK. Using the Job-Related Affective Well-Being Scale (JAWS) to investigate affective responses to work stressors. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2000;5:219–230. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.5.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D. Mood and temperament. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra O, Kross E, Sanchez-Burks J. The ‘big idea’ that is yet to be: Toward a more motivated, contextual, and dynamic model of emotional intelligence. The Academy of Management Perspectives. 2014;28:93–107. [Google Scholar]

- Yik M. Culture, gender, and the bipolarity of momentary affect. Cognition and Emotion. 2007;21:664–680. [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Berkhof J, Nicolson NA. Changes in affect interrelations as a function of stressful events. Cognition and Emotion. 2002;16:309–318. [Google Scholar]

- Zeidner M, Olnick-Shemesh D. Emotional intelligence and subjective well-being revisited. Personality and Individual Differences. 2010;48:431–435. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets pertinent to the present project can be found at the following OSF repository web address: https://osf.io/8wzrk/?. None of these studies was preregistered.