Abstract

Background

There is limited evidence to date about changes to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) during the initial wave of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). To address this gap, our team organized a multicountry, cross-sectional online survey as part of a global consortium.

Methods

Consortium research teams conducted online surveys in 30 countries. Sampling methods included convenience, online panels, and population-representative. Primary outcomes included sexual behaviors, partner violence, and SRH service use, and we compared 3 months prior to and during policy measures to mitigate COVID-19. We conducted meta-analyses for primary outcomes and graded the certainty of the evidence.

Results

Among 4546 respondents with casual partners, condom use stayed the same for 3374 (74.4%), and 640 (14.1%) reported a decline. Fewer respondents reported physical or sexual partner violence during COVID-19 measures (1063 of 15 144, 7.0%) compared to before COVID-19 measures (1469 of 15 887, 9.3%). COVID-19 measures impeded access to condoms (933 of 10 790, 8.7%), contraceptives (610 of 8175, 7.5%), and human immunodeficiency virus/sexually transmitted infection (HIV/STI) testing (750 of 1965, 30.7%). Pooled estimates from meta-analysis indicate that during COVID-19 measures, 32.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 23.9%–42.1%) of people needing HIV/STI testing had hindered access, 4.4% (95% CI, 3.4%–5.4%) experienced partner violence, and 5.8% (95% CI, 5.4%–8.2%) decreased casual partner condom use (moderate certainty of evidence for each outcome). Meta-analysis findings were robust in sensitivity analyses that examined country income level, sample size, and sampling strategy.

Conclusions

Open science methods are feasible to organize research studies as part of emergency responses. The initial COVID-19 wave impacted SRH behaviors and access to services across diverse global settings.

Keywords: HIV, sexually transmitted infections, sexual behavior, sexual violence, condom use

The I-SHARE-1 study in 30 countries assessed sexual and reproductive health outcomes among adults. During COVID-19 measures, 32.3% of people needing HIV/STI testing had hindered access, 4.4% experienced partner violence, and 5.8% decreased casual partner condom use.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has profoundly disrupted social relationships and health services that are fundamental to sexual and reproductive health [1]. The initial wave of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infections (COVID-19 disease) forced billions of people worldwide to shelter in place, transforming social and sexual relationships. Entrenched gender inequalities that existed prior to COVID-19 may have been exacerbated during the emergency response [2], placing people at increased risk for intimate partner violence (IPV). At the same time, a wide range of essential sexual and reproductive health services were stopped or reoriented because of the pandemic [3]. These trends suggest an important question: How have COVID-19 measures impacted sexual and reproductive health outcomes in different settings? Here, we define COVID-19 measures as responses to slow COVID-19 transmission, including movement restrictions, testing programs, and stay-at-home orders [4].

Although social lives during the COVID-19 pandemic have been altered, there has been substantial variation in COVID-19 disease incidence and responses at the national level. Some countries have imposed less stringent lockdown measures, allowing greater movement between and within cities, while others have instituted more unyielding measures [5]. Several countries already had infrastructure in place for decentralized sexual and reproductive health services (eg, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) self-testing, telemedicine abortion) that compensated for pandemic-related closures of facility-based services during COVID-19 [6]. However, in most countries, COVID-19 further undermined already fragile health infrastructure and health service provision [7].

Despite the importance of sexual and reproductive health during the initial wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, research in this area is limited [8, 9]. Modeling and other research studies have noted the lack of detailed information about COVID-19 sexual and reproductive health [10, 11]. The lack of standardized survey instruments makes cross-country comparisons more difficult. Most of the sexual and reproductive health research on initial COVID-19 waves has focused on high-income countries [8], rather than examining broader regional and global trends. Few studies to date have included low- and middle-income countries [9]. At the same time, the global pandemic has accelerated open science and new forms of collaboration.

Our team organized a cross-sectional, multicountry study called the International Sexual Health And REproductive Health during COVID-19 (I-SHARE) study [12]. The I-SHARE project convened a group of sexual and reproductive health researchers to administer a common online survey instrument in respective countries [13]. Teams were identified through an earlier World Health Organization (WHO) crowdsourcing open call [12] and an Academic Network for Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Policy (ANSER) open call. The purpose of this multicountry study was to better understand sexual and reproductive health prior to and during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in respective countries.

METHODS

A more detailed description of survey methods can be found in the protocol [12]. Data were collected from 20 July 2020 to 15 February 2021. Our primary aims in the study were to examine changes in sexual behaviors (sex frequency and condomless sex), IPV, and use of sexual and reproductive health services during COVID-19 measures using a cross-sectional survey. Secondary study aims were to examine changes in HIV/sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing, harmful cultural practices, mental health, and food security. Each country adjusted the questionnaire based on country-level priorities, opportunities, and needs. The consortium recommended a sample size of at least 200, but precise sample size calculations were made by each country’s research team. We used an open science approach in organizing this study and welcomed all interested researchers to join the consortium. This approach included allowing any interested research team to join the project, facilitating collaboration between sites, leveraging open-access software, and prioritizing open-access outputs.

Recruitment and Participants

Participants were recruited through an online survey link that was distributed through local, regional, and national networks. Recruitment used social media (26 studies), partner organizations (20 studies), paid social media advertising (11 studies), university websites (10 studies), telephone interviews (4 studies), and television or newspapers (3 studies). Thirty countries implemented the study, including Argentina, Australia, Botswana, Canada, China, Colombia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Egypt, France, Germany, Italy, Kenya, Latvia, Lebanon, Luxembourg, Malaysia, Mexico, Moldova, Mozambique, Nigeria, Panama, Portugal, Singapore, South Africa, Sweden, Spain, Uganda, United States, and Uruguay (Supplementary Table 1). A total of 23 studies used convenience sampling (Australia, Canada, Colombia, China, Czech Republic, Egypt, France, Germany, Italy, Latvia, Panama, Portugal, Luxembourg, Mexico, Malaysia, Moldova, Mozambique, Nigeria, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Uruguay, United States), 6 studies used online panels (Sweden, Botswana, Uganda, Lebanon, Kenya, Argentina), and 2 used population-based methods (Czech Republic, Denmark). Consortium members in the Czech Republic conducted 2 separate studies (1 using a convenience sample and 1 using a population-based sample), and thus a total of 31 studies among 30 countries were reported. Eligible participants were aged ≥18 years (or younger if the country’s institutional review board and ethical regulation permitted it and the in-country lead ensured appropriate procedures), resided in the respective participating country, were capable of reading and understanding the survey language, could access an online survey, and were willing to provide informed consent.

Survey Development

The partners collaboratively developed the survey instrument based on existing items from a recent WHO survey instrument intended for global use [14], other existing tools, and items adapted for COVID-19. The survey included the following sections: sociodemographic characteristics, compliance with COVID-19 measures, couple and family relationships, sexual behavior, contraceptive use and barriers to access, access to reproductive healthcare, abortion, sexual violence and IPV, HIV/STI testing and treatment, female genital mutilation/cutting and early/forced marriage (optional), mental health (optional), and food insecurity (optional) (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). The time periods for pre–COVID-19 and during initial COVID-19 measures were decided by the in-country team. We focused on an interval of 3 months before the COVID-19 measures because of harmonization with other SRH indicators and less recall bias compared with longer periods [15].

The lead organization in each country selected networks to disseminate the survey link, and it was primarily distributed through email lists, local partner organizations affiliated with ANSER, other sexual and reproductive health networks, and social media links. The survey took most participants 20–30 minutes to complete (Supplementary Table 3).

Data Analysis

Multicountry analysis was undertaken for countries that met specific prespecified criteria. Each country was required to have obtained institutional review board approval from a local ethics authority, locally translated and field-tested the instrument, described the sampling methodology, and obtained responses from at least 200 participants. A minimum threshold of 200 participants was used because small samples may be more likely to be biased and have higher heterogeneity [16]. We examined the effect of including all data empirically using a sensitivity analysis. We did not weight our estimates because most countries did not use a probability sample. We conducted descriptive meta-analysis to assess the effect of study characteristics and setting and more accurately estimate the prevalence of our primary outcomes across countries.

First, we ran descriptive statistics on using the main dataset of 25 countries to assess patterns in respondent sociodemographic characteristics and to assess the primary outcomes prior to and during COVID-19 measures. We used the Oxford indices to assess the stringency of COVID-19 measures in each country, based on the mean value across the days when the survey was open. We used the Appraisal Tool for Cross-Sectional Studies to assess risk of bias [17]. Second, we conducted a meta-analysis for all 30 countries on the prevalence of reported hindered access to HIV/STI testing, IPV during COVID-19 measures, and decreased condom use with casual partners. We used meta-analysis because this provided a mechanism to assess risk of bias of individual studies and consider the strength of the evidence. Tests for heterogeneity were applied using I2 statistics [18]. We used the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) framework to rate the quality of evidence presented in our meta-analysis [19]. Furthermore, we conducted sensitivity analyses that separated primary outcomes based on country income level (low- and middle-income countries compared with high-income countries), sample size (less than 200 or more), and sampling strategy (convenience compared with online panel or population-representative). All analyses were carried out using Stata version 14, and missing data were treated by pairwise deletion (available-case analysis).

RESULTS

Descriptive Analysis

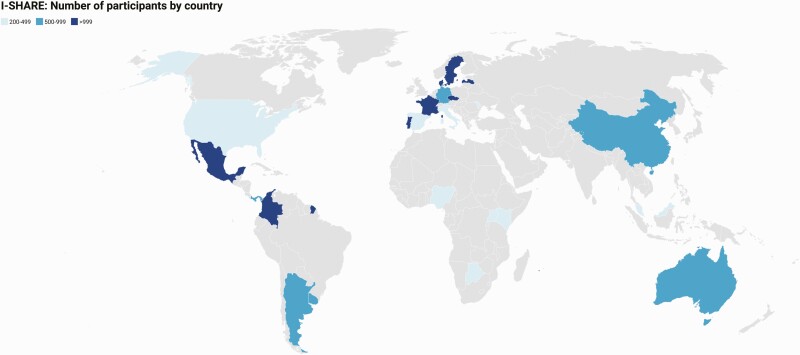

Twenty-five of the 30 countries that joined the I-SHARE study (Figure 1) met all study criteria, including recruiting a minimum of 200 participants. Five countries (Mozambique, Canada, Egypt, Lebanon, South Africa) had fewer than 200 participants and were excluded from descriptive analyses. The majority of countries across all 4 geographic regions implemented all survey components, except female genital mutilation and early marriage (Supplementary Table 2). Abortion and mental health components were excluded in 2 and 3 countries, respectively.

Figure 1.

World map with the 25 countries included in the I-SHARE shaded. Abbreviation: I-SHARE, International Sexual Health And REproductive Health during COVID-19 Study.

Among the 25 included countries, 14 were high-income, 8 were upper-middle-income, 2 were lower-middle-income, and 1 was low-income (see Supplementary Table 1). There was a wide geographic distribution, with 11 countries in Europe, 6 in the Americas, 4 in Asia and Oceania, and 4 in Africa.

As shown in Table 1, more than two-thirds (68.5%) of participants were women, and more than 9 in 10 participants (95.6%) were cis-gender. About 78% of participants were heterosexual. Most participants (44.6%) were aged 18–29 years, followed by those aged 30–39 (26.9%) and 40–49 (14.4%) years. Few participants (2.9%) were aged ≥70 years. More than half (55.9%) of participants reported having completed a college degree. There was diversity in reported socioeconomic position of the household relative to others in their country, with most participants (38.4%) indicating that their household was in the fifth or sixth highest income group out of 10 in their country.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Participants in the International Sexual Health And REproductive Health during COVID-19 (I-SHARE) Multicountry Survey, 2020–2021

| Variable | Level | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex assigned at birth | Female | 13 450 | 68.5 |

| Male | 6169 | 31.4 | |

| Another sexa | 28 | 0.1 | |

| Total | 19 647 | 100 | |

| Gender | Cisgender | 18 512 | 95.6 |

| Non-cisgender | 777 | 4.0 | |

| Another gender | 86 | 0.4 | |

| Total | 19 375 | 100 | |

| Sexual orientation | Heterosexual | 16 592 | 77.9 |

| Bisexual | 1823 | 8.6 | |

| Gay | 818 | 3.8 | |

| Asexual | 629 | 3.0 | |

| Questioning or unsure | 446 | 2.1 | |

| Other | 351 | 1.7 | |

| Lesbian | 315 | 1.5 | |

| Pansexual | 315 | 1.5 | |

| Total | 21 289 | 100 | |

| Age group, y | 18–29 | 10 135 | 44.6 |

| 30–39 | 6109 | 26.9 | |

| 40–49 | 3268 | 14.4 | |

| 50–59 | 1644 | 7.2 | |

| 60–69 | 916 | 4.0 | |

| 70+ | 652 | 2.9 | |

| Total | 22 724 | 100 | |

| Education | No formal education | 102 | 0.5 |

| Some or completed primary school | 944 | 4.2 | |

| Some or completed secondary school | 4717 | 20.8 | |

| Some college or university | 3457 | 15.3 | |

| Completed college or university | 12 619 | 55.7 | |

| Other | 803 | 3.6 | |

| Total | 22 642 | 100 | |

| Relative household socioeconomic position (1–10)b,c | Lower position (1–2) | 2227 | 11.1 |

| 3–4 | 4319 | 21.5 | |

| 5–6 | 7712 | 38.4 | |

| 7–8 | 4327 | 21.6 | |

| Higher position (9–10) | 1486 | 7.4 | |

| Total | 20 071 | 100 | |

| Urban/Rural | Urban or semiurban | 15 722 | 74.0 |

| Rural or semirural | 4710 | 22.2 | |

| Other | 809 | 3.8 | |

| Total | 21 241 | 100 | |

| Relationship statusc | Single, never had partner | 2113 | 9.3 |

| Single, ever had partner | 4268 | 18.8 | |

| In a relationship, not cohabiting | 4354 | 19.2 | |

| Not married, cohabiting | 4349 | 19.1 | |

| Legally married, cohabiting | 5753 | 25.3 | |

| Legally married, not cohabiting | 1083 | 4.8 | |

| Separated or divorced | 894 | 3.9 | |

| Widowed | 178 | 0.8 | |

| Other | 285 | 1.3 | |

| Total | 22 724 | 100 | |

| Current pregnancy situation | Currently pregnant | 514 | 3.7 |

| Currently trying to become pregnant | 835 | 6.1 | |

| Recently had a baby | 432 | 3.1 | |

| Not currently trying to become pregnant | 10 377 | 75.2 | |

| Cannot have children | 1584 | 11.5 | |

| Other | 60 | 0.4 | |

| Total | 13 802 | 100 | |

| Sexual activity frequency (steady partner) | Never | 811 | 5.3 |

| Monthly or less | 2366 | 15.4 | |

| 2–4 times a month | 5758 | 37.6 | |

| 2–3 times a week | 4583 | 29.9 | |

| 4 or more times a week | 1802 | 11.8 | |

| Total | 15 320 | 100 | |

| Sexual activity frequency (casual partner) | Never | 15 655 | 75.9 |

| Monthly or less | 3181 | 15.4 | |

| 2–4 times a month | 1375 | 6.7 | |

| 2–3 times a week | 316 | 1.5 | |

| 4 or more times a week | 96 | 0.5 | |

| Total | 20 623 | 100 | |

| Sex life satisfaction (before COVID-19) | Very satisfied | 7535 | 36.6 |

| Somewhat satisfied | 8026 | 39.0 | |

| Neutral | 216 | 1.1 | |

| Not very satisfied | 3431 | 16.7 | |

| Not at all satisfied | 1382 | 6.7 | |

| Total | 20 590 | 100 | |

| Sex life satisfaction (during COVID-19) | Very satisfied | 5484 | 26.7 |

| Somewhat satisfied | 6738 | 32.8 | |

| Neutral | 202 | 1.0 | |

| Not very satisfied | 4788 | 23.3 | |

| Not at all satisfied | 3353 | 16.3 | |

| Total | 20 565 | 100 |

We did not include comparative population-based data for the entire sample since there were different sampling methods (convenience, online panel, population-representative) used.

Abbreviation: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

This included individuals whose sex at birth was not a male or female.

This item assessed relative household economic position compared with other people in the same country, ranging from 1 to 10; 1 denotes a lower economic position and 10 a higher economic position.

Household socioeconomic status and relationship status were not mutually exclusive, and participants could choose more than 1.

The lower panel of Table 1 presents relationship status, sexual frequency, and sexual satisfaction in the 3 months before and during COVID-19 measures. There was a variety of relationship types reported, with 43.4% in a cohabiting relationship. Among those with a steady partner, 37.6% reported having sex with that partner 2–4 times a month, and another 29.9% reported 2–3 times a week. Among those with a casual partner, the most commonly reported frequency of sex with that partner was monthly or less (15.4%). Most participants (75.6%) reported being somewhat satisfied or very satisfied with their sex life before COVID-19, but this proportion fell (to 59.4%) during COVID-19 in the same participants.

In terms of compliance with COVID-19 measures (Supplementary Table 4), 58.9% of participants reported that they had followed measures a lot. The majority (76.6%) had never been in isolation due to their own symptoms or close contact with someone with COVID-19. Although 62.2% of participants said that their household socioeconomic status stayed the same during the COVID-19 pandemic, about one-third (32.0%) reported their household economic situation worsened.

Table 2 shows our key study outcomes before and during COVID-19. Condom use “always” or “most of the time” with steady partners (62.3%) and with casual partners (64.6%) was relatively high prior to COVID-19 measures. Although most participants perceived their condom use stayed the same during COVID-19 measures (74.4% with casual partners and 86.9% with steady partners), 14.1% of participants with casual partners (and 10.4% of those with steady partners) reported their condom use with those types of partners decreased during COVID-19 measures. Regarding physical or sexual violence, 9.3% reported experiencing 1 or more types of violence prior to COVID-19, and a slightly lower proportion (7.0%) reported experiencing these types of violence during COVID-19 measures.

Table 2.

Key Outcomes 3 Months Before and During Coronavirus Disease 2019 Social Distancing Measures in the 25 International Sexual Health And REproductive Health during COVID-19 (I-SHARE) Study Countries With ≥200 Respondents, 2020

| Key Outcomes | N | % | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Condom use with steady partners (before) | N = 3281 | ||

| Always or most of the time | 2045 | 62.33 | (60.64–63.99) |

| Sometimes/Rarely/Never | 1236 | 37.67 | (36.01–39.36) |

| Condom use with casual partners (before) | N = 4357 | ||

| Always or most of the time | 2816 | 64.63 | (63.19–66.05) |

| Sometimes/Rarely/Never | 1541 | 35.37 | (33.95–36.81) |

| Perceived changes to condom use with steady partners (during) | N = 12 183 | ||

| Decreased | 1262 | 10.36 | (9.82–10.91) |

| Stayed the same | 10 588 | 86.91 | (86.29–87.50) |

| Increased | 333 | 2.73 | (2.45–3.04) |

| Perceived changes to condom use with casual partners (during) | N = 4546 | ||

| Decreased | 640 | 14.08 | (13.08–15.12) |

| Stayed the same | 3374 | 74.22 | (72.92–75.49) |

| Increased | 532 | 11.70 | (10.78–12.67) |

| Any physical or sexual violence from partner (before) | N = 15 887 | ||

| No | 14 418 | 90.75 | (90.29–91.20) |

| Yes | 1469 | 9.25 | (8.80–9.71) |

| Any physical or sexual violence from partner (during) | N = 15 144 | ||

| No | 14 081 | 92.98 | (92.56–93.38) |

| Yes | 1063 | 7.02 | (6.62–7.44) |

| Among those reporting no prior physical or sexual violence from a partner, 1.4% reported experiencing violence during COVID-19 measures. Among those who did report prior physical or sexual violence from a partner, 67.9% reported also experiencing violence during COVID-19 measures. | |||

| COVID-19 measures made it more difficult to access condoms | N = 10 790 | ||

| No | 9857 | 91.35 | (90.80–91.87) |

| Yes | 933 | 8.65 | (8.12–9.19) |

| COVID-19 measures stopped or hindered you from seeking contraceptives | N = 8175 | ||

| No | 7565 | 92.54 | (91.95–93.10) |

| Yes | 610 | 7.46 | (6.90–8.05) |

| COVID-19 measures stopped or hindered you from seeking or obtaining an abortiona | N = 150 | ||

| No | 104 | 69.33 | (61.29–76.59) |

| Yes | 46 | 30.67 | (23.41–38.71) |

| COVID-19 measures stopped or hindered you from accessing a test for human immunodeficiency virus or sexually transmitted infectionsb | N = 1965 | ||

| No | 1215 | 61.83 | (59.64–63.99) |

| Yes | 750 | 38.17 | (36.01–40.35) |

Abbreviation: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Among those reporting being in need of abortion during COVID-19.

Among those reporting wanting a human immunodeficiency virus or sexually transmitted infection test.

For sexual and reproductive healthcare access, we first examined condom access. About 9% of participants indicated that COVID-19 measures made it more difficult to access condoms. A slightly smaller proportion (7.5%) reported that COVID-19 measures hindered contraceptive access. Nearly one-third (30.7%) of participants who reported needing abortion services during COVID-19 reported that COVID-19 measures hindered them from obtaining this service. In addition, 38.2% of participants who needed HIV/STI testing reported that COVID-19 measures hindered them from accessing HIV/STI testing.

Meta-Analyses

Meta-analyses using data from all 30 countries indicated substantial heterogeneity at the country level for all outcomes, including hindered access to HIV/STI testing (P = .000, I2 = 89.9%), IPV experienced during COVID-19 measures (P = .000, I2 = 95.5%), and condom use during COVID-19 measures (P = .000, I2 = 95.5%). Pooled estimates suggest that 32.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 23.9%–42.1%) of people needing HIV/STI testing had hindered access to HIV/STI testing (Supplementary Figures 1–3). Approximately 4.4% (95% CI, 3.4%–5.4%) of people experienced physical or sexual violence (Supplementary Figures 4–6) during COVID-19 measures. Finally, 5.8% (95% CI, 5.4%–8.2%) of people reported a decrease in condom use with sexual partners during COVID-19 measures (Supplementary Figures 7–9).

Risk of bias assessment for the studies in I-SHARE indicated that, in general, study procedures of all studies were largely justified, appropriate, and adequately described (Supplementary Table 5). The convenience sampling methods used by most countries introduced bias. In addition, response rates raised concerns about nonresponse bias, and information about nonresponders was not available.

Based on the GRADE framework, each of the 3 main findings was associated with a moderate certainty of evidence (Supplementary Table 6). Observational studies in general begin at a low quality of evidence; while there were risks of bias due to convenience sampling, we rated the quality of our evidence upward due to the large effect size for the outcome of hindered access to HIV/STI testing and the large sample size of the study across all outcomes.

DISCUSSION

Our study findings provide important insights into sexual and reproductive health during the initial COVID-19 wave in diverse global settings. Our data suggest that condomless sex with casual partners did not substantially change with the introduction of COVID-19 measures. Experiences of IPV may have decreased during COVID-19 measures compared with prior to the pandemic. Among the health services we examined, there were marked decreases in access to HIV/STI testing and abortion services.

We found that condomless sex was similar during COVID-19 measures compared with the pre–COVID-19 period for many respondents. Approximately 74%–87% of people reported that condom use with a steady and/or casual partner stayed the same during these 2 periods. Maintenance of pre–COVID-19 condom use behavior is consistent with observational studies of sex workers and ethnic and racial minority groups [20, 21]. Given that COVID-19 introduced new disease risks, some individuals may have been less likely to engage in risky sexual behaviors [22]. Only 8.7% of the sample noted problems accessing condoms. The COVID-19 environment did not appear to substantially alter individual decisions about whether to use a condom.

Our results suggest a modest decrease in sexual and physical partner violence during COVID-19 measures compared with the pre–COVID period. Although there was concern about COVID-19 exacerbating IPV [2], data on IPV during the pandemic have been mixed. Some studies suggest increased IPV during COVID-19 measures [23, 24], while others found decreases [25]. Other research has shown that IPV may increase after a natural disaster [26, 27], indicating a need for follow-up studies to see if IPV worsened as the COVID-19 pandemic continued beyond the initial wave that we examined in this study.

Our study also indicates that COVID-19 measures interrupted access to HIV/STI testing and abortion services. This finding is consistent with other studies observing interruptions in HIV/STI testing [28, 29] and abortion services [30]. Decentralized testing approaches using STI self-collection and HIV self-testing [31] have alleviated some of the gaps in diagnostic service provision during COVID-19. However, despite strong evidence that telemedicine is safe and effective for providing medical abortion services [32], several countries further restricted abortion services during the initial wave of the COVID-19 pandemic [33]. More research and advocacy are needed to support abortion services during pandemics and similar circumstances.

Our study has several limitations. First, this was an online survey organized during COVID-19 measures, introducing risk for selection bias. Although there is no guideline for conducting online surveys, we used several strategies to limit bias, including the use of online panels, partnerships with organizations for sample recruitment, review of analytics, and prespecified analysis plans [13] Second, although we were able to capture data from different times during the COVID-19 epidemic, this was a series of retrospective cross-sectional studies, and we did not capture how sexual behaviors and access evolved over the course of the pandemic. Third, our sample included more women, people with higher education, and people living in high-income countries compared with populations in respective countries. At the same time, data from 1 of the convenience samples included in this analysis suggested that the convenience sample included similar proportions of adults within subnational geographic areas compared with census data [34]. Fourth, our study had fewer studies from low-income countries, which may have been due to later COVID-19 initial waves and less capacity for research alongside the pandemic. At the same time, our main findings were robust when stratified based on country income level. Fifth, our meta-analyses revealed substantial heterogeneity. However, the common survey instrument, shared protocol, and similar online recruitment methods provide a strong rationale for making these comparisons. In addition, our sensitivity analyses suggested that main findings were robust across country income level, sample size, and sampling strategy. Sixth, our data relied on self-reported data and did not capture STI/HIV transmission.

Although COVID-19 measures made it more difficult to obtain population-representative samples, we organized a multicountry analysis of data from 30 countries. Several studies have noted that online surveys may be particularly useful for collecting information about sensitive sexual behaviors compared with in-person survey methods [3, 13, 35, 36]. Strengths of this study include the inclusive open science approach, the harmonization of key sexual health variables across countries, and the geographic diversity.

This study has implications for research and policy. From a research perspective, this underscores the need for sexual behavior, IPV, and reproductive health service access research in emergency settings. Given the heterogeneity in study outcomes, multinational studies should consider using methods that account for clustering (eg, multilevel modeling). From a policy perspective, our data suggest the need for expanded use of decentralized sexual and reproductive health interventions that could be implemented in emergency settings (eg, self-testing, self-collection, telemedicine abortion). The results from country-level data have already helped to inform COVID-19–related sexual and reproductive health policies in several countries, including Latvia, Czech Republic, Panama, Singapore, Uruguay, and Portugal.

Finally, the open science methods used in this study point toward new frameworks for global health collaboration. We organized a survey in 30 diverse settings during a pandemic, despite not having a central funding source or a COVID-19–specific organizational remit. This suggests the feasibility of grounds-up organized multicountry studies focused on sexual and reproductive health.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Author Contributions. R. T., J. T. E., K. M., and J. T. developed the initial idea. R. T. and J. T. E. led the data analysis with the data analysis subgroup that included A. A., A. L., M. U., K. M., E. W., T. H., S. S., M. M., J. T., W. H. Z., A. M., and J. F. The digital working group that programmed the surveys included T. H., P. K., S. S., L. C., E. B., and L. R. Country leads on the surveys included K. K., K. M., A. G., S. B., D. H., S. S., J. S., T. E., C. M., S. E., W. L., L. P., G. L., A. O., and C. M.; they led field testing, translation, ethical review applications, and survey implementation at the country level. K. M. and J. T. were coordinators for multicountry analysis. All authors read and approved the final version that was submitted.

Acknowledgments. The authors would like to thank the following individuals who contributed to this manuscript: Adedamola Adebayo, Emmanuel Adebayo, Noor Ani Ahmad, Nicolás Brunet, Anna Kagesten, Elizabeth Kemigisha, Eneyi Kpokiri, Ismael Maatouk, Griffins Manguro, Filippo M. Nimbi, Pedro Nobre, Caitlin O’Hara, Oloruntomiwa Oyetunde, Muhd Hafizuddin Taufik Ramli, Dace Rezeberga, Juan Carlos Rivillas, Kun Tang, Ines Tavares. In addition, we would like to thank the members of the research consortium (a list can be found at https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1tHIXp0sM92CrpNDASdN_3hGIH7rj2x9FWY4Gmze6lgs/edit#gid=0).

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH; UG3HD096929 and NIAID K24AI143471). In Latvia, this research was supported by the National Research Programme to Lessen the Effects of COVID-19 (VPP-COVID-2020/1-0011).

Potential conflicts of interest. A. D. has received grants/contracts from the Consortium for Advanced Research Training In Africa (CARTA); consulting fees from the Population Council, FP CAPE, Measurement Learning and Evaluation, Family Health International, Federal Ministry of Health/World Health Organization (WHO), and PATHS 2; payments/honoraria from the West Africa College of Physicians and CARTA; support for attending meetings and/or travel from CARTA, Stroke and Cardiovascular Research Training (S-CaRT) Institute Programme (NIH Fogarty), and the WHO-HRP; stock or stock options from the First Bank Nigeria PLC and Cadbury Nigeria PLC; and served in a leadership or fiduciary role at the Society for Adolescent and Young People’s Health in Nigeria and Society for Public Health Professionals of Nigeria. A. G. served in a leadership or fiduciary role at the Community Development Network of the Americas. E. W. is currently receiving support for the work presented here through the University of Antwerp Special Research Fund (the COVID-19 International Student Well-Being Study). G. L. has received grants/contracts from the Ministry of Education and Research, Latvia (payment made to all researchers involved in the I-SHARE/LATVIA study through Riga Stradins University); support for attending meetings and travel from COST Action (CA18124; ESMN); and participated in a data safety monitoring board or advisory board as a member of the HRP Alliance Advisory Board. D. H. has received consulting fees from OMGYes.com, Journal of Sex Research, and Journal of Adolescent Health and served in a leadership or fiduciary role for several national committees for the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. K. M. has received consulting fees from Coral Sexual Wellness and the Museum of Sex, New York City; has received support for attending meetings and/or travel from the University of Minnesota Medical School; and participated on an advisory board for World Association for Sexual Health. S. S. currently receives support for the work presented here through the Foundation for Professional Development and has received support for attending meetings and/or travel from the Foundation for Professional Development. All remaining authors: No reported conflicts of interest.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Contributor Information

Jennifer Toller Erausquin, Department of Public Health Education, University of North Carolina–Greensboro, Greensboro, North Carolina, USA.

Rayner K J Tan, Dermatology Hospital of Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China; University of North Carolina Project–China, Guangzhou, China; Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore, Singapore.

Maximiliane Uhlich, Department of Psychology, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada.

Joel M Francis, Department of Family Medicine, School of Clinical Medicine, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Navin Kumar, Department of Sociology, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Linda Campbell, Center for Population, Family, and Health, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium; Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Ghent, Ghent, Belgium.

Wei Hong Zhang, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Ghent, Ghent, Belgium; School of Public Health, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium.

Takhona G Hlatshwako, Institute of Global Health and Infectious Diseases, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Priya Kosana, Institute of Global Health and Infectious Diseases, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Sonam Shah, Institute of Global Health and Infectious Diseases, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Erica M Brenner, Institute of Global Health and Infectious Diseases, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Lore Remmerie, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Ghent, Ghent, Belgium.

Aamirah Mussa, Botswana Sexual and Reproductive Health Initiative, Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Gaborone, Botswana.

Katerina Klapilova, Faculty of Humanities, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic; National Institute of Mental Health, Klecany, Czech Republic.

Kristen Mark, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Gabriela Perotta, Faculty of Psychology, University of Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Amanda Gabster, Gorgas Memorial Institute for Health Studies, Panama City, Panama; Clinical Research Department, Faculty of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom.

Edwin Wouters, Center for Population, Family, and Health, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium.

Sharyn Burns, Collaboration for Evidence, Research and Impact in Public Health, School of Population Health, Curtin University, Perth, Australia.

Jacqueline Hendriks, Collaboration for Evidence, Research and Impact in Public Health, School of Population Health, Curtin University, Perth, Australia.

Devon J Hensel, Department of Pediatrics, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA; Department of Sociology, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA.

Simukai Shamu, Health Systems Strengthening, Foundation for Professional Development, Pretoria, South Africa; School of Public Health, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Jenna Marie Strizzi, Department of Public Health, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Tammary Esho, End FGM/C Centre of Excellence, Amref Health Africa, Nairobi, Kenya.

Chelsea Morroni, Botswana Sexual and Reproductive Health Initiative, Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Gaborone, Botswana; MRC Centre for Reproductive Health, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom.

Stefano Eleuteri, Department of Psychology, Sapienzo University, Rome, Italy.

Norhafiza Sahril, Ministry of Health Malaysia, Putrajaya, Malaysia.

Wah Yun Low, Asia–Europe Institute, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Leona Plasilova, Faculty of Humanities, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic; National Institute of Mental Health, Klecany, Czech Republic.

Gunta Lazdane, Institute of Public Health, Riga Stradins University, Riga, Latvia.

Michael Marks, Clinical Research Department, Faculty of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom.

Adesola Olumide, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria.

Amr Abdelhamed, Department of Dermatology, Venereology & Andrology, Sohag University, Sohag, Egypt.

Alejandra López Gómez, Department of Psychology, University of the Republic, Montevideo, Uruguay.

Kristien Michielsen, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Ghent, Ghent, Belgium.

Caroline Moreau, Department of Population, Family, and Reproductive Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, USAand; Primary Care and Prevention, Center for Research in Epidemiology and Public Health, National Institute of Health and Medical Research 1018, Villejuif, France.

Joseph D Tucker, University of North Carolina Project–China, Guangzhou, China; Institute of Global Health and Infectious Diseases, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA; Clinical Research Department, Faculty of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom.

International Sexual Health And REproductive Health during COVID-19 Research Consortium:

Adedamola Adebayo, Emmanuel Adebayo, Noor Ani Ahmad, Nicolás Brunet, Anna Kagesten, Elizabeth Kemigisha, Eneyi Kpokiri, Ismael Maatouk, Griffins Manguro, Filippo M Nimbi, Pedro Nobre, Caitlin O’Hara, Oloruntomiwa Oyetunde, Muhd Hafizuddin Taufik Ramli, Dace Rezeberga, Juan Carlos Rivillas, Kun Tang, and Ines Tavares

References

- 1. Hall KS, Samari G, Garbers S, et al. Centring sexual and reproductive health and justice in the global COVID-19 response. The Lancet 2020; 395:1175–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hall B, Tucker JD.. Surviving in place: the coronavirus domestic violence syndemic. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 2020; 53:102179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. Disruption in HIV, hepatitis and STI services due to COVID-19. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anderson RM, Heesterbeek H, Klinkenberg D, Hollingsworth TD.. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? The Lancet 2020; 395:931–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hale T, Petherick A, Phillips T, Webster S.. Variation in government responses to COVID-19. Blavatnik school of government working paper. 2020; 31:2020–11. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jiang H, Xie Y, Xiong Y, et al. HIV self-testing partially filled the HIV testing gap among men who have sex with men in China during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from an online survey. J Int AIDS Soc 2021; 24:e25737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lal A, Erondu NA, Heymann DL, Gitahi G, Yates R.. Fragmented health systems in COVID-19: rectifying the misalignment between global health security and universal health coverage. The Lancet 2021; 397:61–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kumar N, Janmohamed K, Nyhan K, et al. Sexual health (excluding reproductive health, intimate partner violence and gender-based violence) and COVID-19: a scoping review. Sex Transm Infect 2021; 97:402–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wood SN, Karp C, OlaOlorun F, et al. Need for and use of contraception by women before and during COVID-19 in four sub-Saharan African geographies: results from population-based national or regional cohort surveys. Lancet Glob Health 2021; 9:e793–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Frost I, Craig J, Osena G, et al. Modelling COVID-19 transmission in Africa: countrywise projections of total and severe infections under different lockdown scenarios. BMJ Open 2021; 11:e044149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Riley T, Sully E, Ahmed Z, Biddlecom A.. Estimates of the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sexual and reproductive health in low- and middle-income countries. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2020; 46:73–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Michielsen K, Larrson EC, Kagesten A, et al. International Sexual Health And REproductive health (I-SHARE) survey during COVID-19: study protocol for online national surveys and global comparative analyses. Sex Transm Infect 2020; 97:88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hlatshwako TG, Shah SJ, Kosana P, et al. Online health survey research during COVID-19. Lancet Digit Health 2021; 3:e76–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kpokiri E, Wu D, Srinivas M, et al. Using a crowdsourcing open call, hackathon and a modified Delphi method to develop a consensus statement and sexual health survey instrument. Sex Transm Infect 2021; 98:38–43.33846277 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Napper LE, Fisher DG, Reynolds GL, Johnson ME.. HIV risk behavior self-report reliability at different recall periods. AIDS Behav 2010; 14:152–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. IntHout J, Ioannidis JPA, Borm GF, Goeman JJ.. Small studies are more heterogeneous than large ones: a meta-meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2015; 68:860–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS.. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016; 6:e011458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG.. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003; 327:557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004; 328:1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Machingura F, Chabata S, Busza J, et al. Potential reduction in female sex workers’ risk of contracting HIV during Covid-19. AIDS 2021; 35:1871–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Craig-Kuhn MC, Schmidt N, Scott G Jr, et al. Changes in sexual behavior related to the COVID-19 stay-at-home orders among young Black men who have sex with women in New Orleans, LA. Sex Transm Dis 2021; 48:589–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bowling J, Montanaro E, Gattuso J, Gioia D, Guerrero Ordonez S.. “Everything feels risky now”: perceived “risky” sexual behavior during COVID-19 pandemic. J Health Psychol 2021; 18:13591053211004684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Walsh AR, Sullivan S, Stephenson R.. Intimate partner violence experiences during COVID-19 among male couples. J Interpers Violence 2021:8862605211005135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fawole OI, Okedare OO, Reed E.. Home was not a safe haven: women’s experiences of intimate partner violence during the COVID-19 lockdown in Nigeria. BMC Womens Health 2021; 21:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ojeahere MI, Kumswa SK, Adiukwu F, Plang JP, Taiwo YF.. Intimate partner violence and its mental health implications amid COVID-19 lockdown: findings among Nigerian couples. J Interpers Violence 2021:8862605211015213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rao S. A natural disaster and intimate partner violence: evidence over time. Soc Sci Med 2020; 247:112804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bell SA, Folkerth LA.. Women’s mental health and intimate partner violence following natural disaster: a scoping review. Prehosp Disaster Med 2016; 31:648–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rao A, Rucinski K, Jarrett BA, et al. Perceived interruptions to HIV prevention and treatment services associated with COVID-19 for gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in 20 countries. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2021; 87:644–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mbithi I, Thekkur P, Chakaya JM, et al. Assessing the real-time impact of COVID-19 on TB and HIV services: the experience and response from selected health facilities in Nairobi, Kenya. Trop Med Infect Dis 2021; 6:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jones RK, Lindberg L, Witwer E.. COVID-19 abortion bans and their implications for public health. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2020; 52:65–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kpokiri EE, Marley G, Tang W, et al. Diagnostic infectious diseases testing outside clinics: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020; 7:ofaa360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Endler M, Lavelanet A, Cleeve A, Ganatra B, Gomperts R, Gemzell-Danielsson K.. Telemedicine for medical abortion: a systematic review. Bjog 2019; 126:1094–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bojovic N, Stanisljevic J, Giunti G.. The impact of COVID-19 on abortion access: insights from the European Union and the United Kingdom. Health Policy 2021; 125:841–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gabster A, Erausquin JT, Michielsen K, et al. How did COVID-19 measures impact sexual behaviour and access to HIV/STI services in Panama? Results from a national cross-sectional online survey [published online ahead of print, 2021 Aug 16]. Sex Transm Infect 2021:sextrans-2021-054985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kreuter F, Presser S, Tourangeau R.. Social desirability bias in CATI, IVR, and web surveys: the effects of mode and question sensitivity. Public Opinion Quarterly 2009; 72:847–65. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tso LS, Tang W, Li H, Yan HY, Tucker JD.. Social media interventions to prevent HIV: a review of interventions and methodological considerations. Curr Opin Psychol 2016; 9:6–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.