ABSTRACT

Introduction

DoD Global Health Engagement (GHE) planners can follow a number of models to effectively plan and execute successful GHE activities. One recommendation that could provide a significant return on investment for the DoD GHE enterprise is to utilize a “Crawl, Walk, Run” training model to build or enhance a specific medical capability for a Partner Nation (PN). Through the African Peacekeeping Rapid Response Partnership (APRRP) program, U.S. military medical subject matter experts serving as instructors for a Field Sanitation Course (FSC) delivered to the Senegalese Armed Forces (SAF), gained first-hand experience of the positive outcomes that resulted from incorporating this training model into the DoD GHE process.

Materials and Methods

The SAF completed three APRRP-led, in-person FSC iterations: May 2019 (crawl phase), September 2019 (walk phase), and February 2020 (run phase). Approximately 1 year after the completion of the in-person FSCs, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, USU’s CGHE offered a Field Sanitation Virtual Engagement to augment the FSC, emphasize specific field sanitation topics, and discuss lessons learned with the SAF on the deployment of their Level 2 Hospital.

Results

Before deploying their Level 2 Hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic, the SAF conducted a base camp assessment and found multiple ways to apply the knowledge and skills learned through the APRRP FSC to address issues related to waste management, pest control, and personal protective measures to protect against COVID-19. The SAF’s progress in strengthening and institutionalizing their field sanitation capabilities can be seen by their execution of their own variation of the FSC—in preparation for their deployment, the SAF conducted three of their own FSCs, which closely resembled the APRRP-administered course.

Conclusions

The “Crawl, Walk, Run” training model demonstrates an excellent teaching method that develops PN instructors so they can train more personnel in the long-term, thus building both capacity and capability. This gives the PN the opportunity to sustainably institutionalize a course, allowing them to continue training it in perpetuity. Implementing this training model flexibly to adapt to the differing needs of each PN and each line of effort would increase the success of DoD GHE activities when training PNs. It would also ensure the PN has the capability to sustainably institutionalize a course and can independently train future cohorts through internal iterations of the course.

Introduction

When military units deploy in response to conflict or humanitarian crises, enemy forces are not the only threat found in the operational environment. Disease and injury pose a significant medical threat to the deployed force and emphasize the need to provide troops, including peacekeepers, with the essential knowledge and skills to protect health and wellness in the field. According to Bosetti and Bridges, “the application of preventive medicine measures can significantly reduce time lost due to disease and non-battle injuries.”1 While basic field sanitation practices and preventive medicine measures may be simple, they must be taught to protect the force.

The introduction of a teaching methodology to build field sanitation capacity and capability began as early as the 1940s. In 1942, Mikesell noted that “little progress has been made in the instruction of troops in sanitation until the demonstration and application method of teaching was adopted.”2 By incorporating demonstrations and application of skills as part of the instruction technique, Mikesell further explained, “the Demonstration method of teaching sanitation, properly presented, adds practical knowledge to a training program. Soldiers after attending demonstrations and lectures, must apply the knowledge repeatedly, under competent and critical supervision of inspecting officers.”2(p403) This article describes a recommendation for the DoD Global Health Engagement (GHE) enterprise to incorporate a “Crawl, Walk, Run” training model that could help Partner Nations (PNs) build instructor capacity in teaching field sanitation practices and preventive medicine measures. The use of this training model in future DoD GHE activities can be an effective training methodology for enhancing field sanitation and other essential medical capabilities for peacekeeping forces and the health of partner militaries in general.

Background

In accordance with DoD Instruction 2000.30, Global Health Engagement Activities, DoD policy states that GHE can be used as a tool to achieve national security objectives.3 DoD GHE activities are sometimes conducted within the context of U.S. Department of State (DoS) funded programs; one example is the African Peacekeeping Rapid Response Partnership (APRRP). Executed by the DoD, APRRP’s mission is to build, strengthen, and institutionalize capabilities to rapidly respond to crises on the African continent.4 Since 2016, the USU’s Center for Global Health Engagement (CGHE), guided by the United States Africa Command’s (USAFRICOM) Office of the Command Surgeon, has implemented the medical component of APRRP through the planning and execution of DoD GHE activities. The APRRP medical component includes building and enhancing medical capacity and capability for four PNs to meet U.N. Level 2 Hospital (L2H) standards for rapid deployment. Through APRRP assistance, PNs strengthen their level of preparedness for U.N. rapid deployment requirements. In alignment with APRRP program objectives, the “DoD has provided assistance to countries within every geographic Combatant Command to enhance our allies and partners’ response activities to COVID-19 and to build long-term public health capacity,” in keeping with the DoD’s strategic messaging that “Our allies and partners are a force multiplier and one of the greatest strategic assets we have in protecting our Nation.”5 The conduct of DoD GHE activities, within the context of APRRP, further demonstrates a deliberate effort to build and strengthen partnerships with PNs.

APRRP Use of “Crawl, Walk, Run” Training Model to Develop PN Instructor Cadre

APRRP training utilizes the “Crawl, Walk, Run” training model. These courses consist of a minimum of three iterations which represent a phase of the training model. During the “Crawl” phase, U.S. subject matter experts (SMEs) instruct 100% of course materials to PN participants and employ a training of trainers (TOT) methodology to increase PN trainer capacity. After the first iteration, U.S. SMEs identify TOT instructor candidates among student participants. These candidates are selected based on their high test scores as well as their leadership, communication skills, and knowledge. During the “Walk” phase, U.S. SMEs teach 50% of the course and the selected TOT instructor candidates from the first iteration teach the other 50%. Prior to teaching, these candidates receive a TOT course to improve their instructor skills. They also receive assistance with revising course materials to apply it to a country context. After the second iteration, the candidates become instructors and are expected to independently teach the full course during the third and final iteration. U.S. SMEs observe the PN instructors, providing mentorship and advice during this last iteration known as the “Run” phase.

Historically, the U.S. military has incorporated the “Crawl, Walk, Run” approach as a training methodology for various training lines of effort (LOEs). Wampler, et al described lessons learned from using this methodology to train specific tasks and recommended following a “proven sequence to maximize success for the ‘Soldier’ to learn.” Examples include utilizing this method to teach medical modeling and simulation and other training topics. Wampler, et al further explained that the “Crawl, Walk, Run” method allowed trainers flexibility and better prepared participants through hands-on training.6 PN participants who receive APRRP training could steadily increase their knowledge and skills over the three iterations, gradually building PN capacity and capability. By incorporating this hands-on aspect throughout the phases, PN instructors further develop their teaching skills. APRRP medical training courses, using this training model, also help the PNs institutionalize various training LOEs to achieve DoD objectives that strengthen PN medical capabilities. Byrne, et al also described how participants [using this method] increased their abilities to solve content-specific problems, add new clinical scenarios that were not included originally in the curriculum, and rehearse the skill sets at varying degrees of difficulty.7 This could also prove useful for U.S. SMEs to consider when developing and delivering future medical courses.

Case Study

USU’s CGHE, in coordination with USAFRICOM and with support of the DoS, began partnering with the Senegalese Armed Forces (SAF) in 2018 as part of the APRRP program to enhance medical capabilities for L2H rapid deployment. While Senegal is the 11th largest peacekeeping troop contributing country globally, according to a recent U.N. report,8 medical training, such as field sanitation, provided through APRRP, coupled with the SAF’s previous peacekeeping deployment experiences, is characterized as enhancing the SAF’s healthcare-related capabilities. DoD entities previously conducted assessments of the SAF’s medical training infrastructure and determined the SAF had the field sanitation expertise but there was no evidence of an established field sanitation program. By building and strengthening these capabilities and partnerships through programs like APRRP, the resources and subject matter expertise leveraged through the DoD GHE enterprise shows a return on investment toward protecting the health of peacekeeping personnel and supports the SAF to enhance their rapid deployment capabilities, including field sanitation training.

Health Security and Field Sanitation

The APRRP Field Sanitation Course (FSC) provides basic instruction in hygiene, preventive medicine, and public health concepts to U.N. troop contributing personnel. PN course participants will be able to:

Identify key health and safety considerations to ensure force health protection of troops in field environments.

Demonstrate a working knowledge of field sanitation principles through practical application exercises.

Apply course concepts to develop a basecamp layout for a given scenario.

Course concepts include personal healthcare and hygiene (infectious diseases and sexually transmitted infections), water supply and testing, food services, waste disposal, and vector control.

Groups within APRRP Medical Training

APRRP medical training requires three distinct groups for a successful execution: (1) U.S. instructors, (2) PN instructors, and (3) PN participants. Each group has different requirements and expectations throughout training. USU’s CGHE provides overall management which includes logistics and administration and serves as the centerpoint for coordination and execution.

Expertise is drawn from the U.S. Army, Navy, and Air Force to staff the training team. U.S. instructor roles and responsibilities include curriculum development, delivering the course, mentoring PN instructors, and providing input for after-action reports.

PN instructor candidates are expected to lead or be involved in the health engagement and must successfully complete the first iteration’s post-tests (80% or higher), as observed by the U.S. instructors. They should be military personnel and have a good understanding of their country’s military capability. PN instructors’ roles and responsibilities can be generalized as course administration, content, implementation, and communication within their military context. They are encouraged to independently implement additional training iterations once the PN completes all phases of an APRRP medical training course.

The Field Sanitation LOE Using the Crawl, Walk, Run Training Model

In developing the APRRP FSC, U.S. SMEs customized course materials to apply to the Senegal country context, including translating course materials into French. APRRP courses need to be adaptable to the differing situations within each PN. Figure 1 describes a “typical” example of a “Crawl, Walk, Run” training model used with the APRRP FSC. Each iteration occurs within 6 to 8 weeks of each other to ensure the PN trainers retain the skills and content learned during the first iteration. However, not all iterations can be conducted within the desired time frame due to a number of challenges such as PN unavailability due to deployments or other emergencies, schedule conflicts due to other training events, delays in the vetting of PN participants, restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic, or other external factors.

Figure 1.

Example of “Crawl, Walk, Run” training model used with the APRRP Field Sanitation Course (Source: APRRP Medical Plan, 2019).

This case study demonstrates the advantages of using the “Crawl, Walk, Run” training model to build and strengthen field sanitation capabilities. The SAF completed three APRRP-led, in-person FSC iterations: May 2019 (crawl phase), September 2019 (walk phase), and February 2020 (run phase). Approximately one year after the completion of the FSC, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, USU’s CGHE offered a virtual engagement to augment the FSC, emphasize specific field sanitation topics, and discuss lessons learned from the SAF’s L2H COVID-19 deployment to Touba, Senegal. The SAF deployed their L2H to alleviate the stress to Senegal’s healthcare system during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting the value of the APRRP program.9

Anecdotally, the SAF Environmental Health Officers (EHOs) reported utilizing some of the APRRP specific training, such as Field Sanitation, to help protect the force during the deployment. The SAF EHOs conducted a base camp assessment and applied the knowledge and skills learned through the APRRP FSC to address issues related to waste management, pest control, and personal protective measures to protect against COVID-19. The SAF showed great progress in strengthening and institutionalizing the field sanitation capability by later independently conducting three of their own FSCs.

Crawl Phase of Field Sanitation Training

During the first iteration, or “Crawl” phase, U.S. instructors taught the entire course to SAF participants. They identified potential trainer or instructor candidates based on participants’ levels of content comprehension, retention, participation, and tests. Afterwards, SAF participants identified as trainers attended a two-day TOT where they learned about basic pedagogy, training concepts, and skills. USU’s CGHE conducted the first iteration of the APRRP FSC for the SAF in May 2019 in Senegal where 16 SAF participants attended.

Walk Phase of Field Sanitation Training

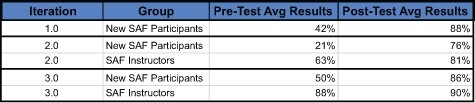

In September 2019, USU’s CGHE delivered the second iteration of the FSC. During this “Walk” phase, selected SAF trainer candidates attended another 2-day TOT course immediately prior to the second full course iteration to receive a refresher on the concepts and requisite skills necessary to teach new SAF participants during the “Walk” phase. The TOT session revisited basic pedagogy, training concepts, and skills before the second iteration began. SAF trainer candidates (from the first iteration) then taught approximately 50% of the course and managed skill stations for new SAF participants. U.S. instructors provided feedback to SAF instructors during their course facilitation, and then taught the remaining 50% of the curriculum. Both U.S. and SAF shared facilitation responsibilities, allowing the SAF to focus on the pedagogy-side of training with constructive feedback from U.S. instructors. Conducting the TOT prior to the second APRRP FSC iteration enabled SAF instructors to confidently deliver 50% of course lectures, facilitate group activities, and coordinate field trips. Figure 2 shows the PN participant results.

Figure 2.

APRRP pre- and post-test average results for all three FSC iterations (Source: APRRP Tests conducted with the SAF).

Run Phase of Field Sanitation Training

In February 2020, USU’s CGHE conducted the third and final iteration of the SAF FSC. SAF instructors taught the entire course during this iteration, or “Run” phase, with feedback provided by U.S. instructors. Before this iteration, the SAF instructors participated in the final TOT session. This TOT did not go in-depth as the previous sessions, but rather emphasized specific pedagogy skills or concepts and re-introduced concepts which the SAF instructors may have needed more thorough discussion with. During this “Run” phase, SAF instructors taught 100% of the course while U.S. instructors assessed their training abilities. Upon completion of the three iterations, the SAF instructors are now able to independently implement this course and institutionalize it within their medical training institution, training future instructors in the process. By this point in the “Crawl, Walk, Run” training model, PN Instructors firmly understand course content as indicated by post-test scores.

Post “Crawl, Walk, Run”

As PN militaries like the SAF institutionalize the medical training provided through APRRP, the DoD has a unique opportunity to continue collaboration and partnership in spite of a pandemic. USU’s CGHE continued to support the SAF after they had deployed their L2H to support their national COVID-19 response, offering to conduct virtual engagements to ascertain that the SAF had the necessary resources to deploy this capability in real-time. USU’s CGHE developed a survey to identify the field sanitation issues and challenges faced during the recent deployment. In response, the SAF asked that the virtual engagement include topics related to water treatment, biohazard/medical waste management, food service sanitation, and pest control. In March 2021, USU’s CGHE coordinated the virtual engagement in which the U.S. SMEs presented the following modules: Water Supply and Treatment, Biohazard and Medical Waste Management, and Food Service Sanitation and Pest Control. The virtual engagement provided the SAF a forum to discuss the challenges they encountered during deployment and exchange best practices on addressing field sanitation issues. SAF participants included previously APRRP-trained Field Sanitation trainers, which confirmed continued interest in enhancing this capability.

Basic Pedagogy, Training Concepts, and Skills Explanation

The APRRP-developed TOT medical training covers basic pedagogy, training concepts, and skills. Pedagogical items covered in APRRP Medical’s TOT program include:

Modern adult education practices

Briefing (pre-briefing, briefing, debriefing)

SMART objectives (Specific, Measureable, Attainable, Relevant, and Time-Bound)

Curriculum and lesson plan development and implementation

Skill station creation and facilitation

Promoting participant-centered learning

The APRRP program’s basic pedagogy modules for medical training guide PN instructors on how to use their training and professional experiences to inform their curriculum and lesson development within their specific medical military context.

APRRP-developed “Task Trackers” are essential documents that enumerate the PN’s responsibilities. As the PN participants progress through the training course using the “Crawl, Walk, Run” training model, their responsibilities increase with each iteration. These Task Trackers become an integral part of assessing and validating that the PNs can eventually facilitate and teach the course on their own. Examples are:

Administration tasks

Supplies/Skill Stations tasks

Didactic/Lesson Planning tasks

Course Delivery and Management tasks

Finally, “skills” is defined as the necessary medical skills associated with a particular line of effort. The TOT program cannot contain all medical skills necessary in one training, however, sessions include built-in mentoring time between the U.S. and the PN instructors. SAF instructors noted they valued the one-on-one guidance provided by the U.S. instructors. The SAF instructors would ask questions about best practices, upcoming presentations, and skill stations resulting in a strong rapport between the PN and U.S. instructors.

How Success Is Measured

PN participant content comprehension and retention can be measured throughout a specific training in a variety of ways. For example, APRRP medical training commonly utilizes “knowledge checks” for determining the PN participants’ understanding and provides assessments to gauge content comprehension and retention throughout the training. Three primary ways LOE success can be measured include: (1) pre-test vs post-test assessment scores evaluation; (2) LOE sustainability; and (3) the LOE institutionalization. PN participants must get 80% on the post-test to demonstrate content mastery.

In order to define APRRP LOE success, the difference between sustainability and institutionalization needs to be explained. Natsios defined the term “sustainability” as one of the “Nine Principles of Reconstruction and Development.” As Principle #3, Natsios further described “the core of the sustainability principle is that development agencies should design programs so that their impact endures beyond the end of the project. Sustainability also encompasses the notion that a country’s resources are finite and development should ensure a balance between economic development, social development, and democracy and governance.”10 In the APRRP context, sustainability can be best measured by whether or not the PN instructors, for any of the APRRP medical courses delivered, can successfully conduct the training themselves without APRRP assistance, while institutionalization can be measured by whether the PN integrates the courses into their training plan and continues to conduct iterations of the training once the initial three iterations have been completed.

PN instructor attendance throughout all iterations helps to predict LOE sustainability. This enables the PN instructors to absorb the course content three times and gives U.S. instructors the opportunity to measure their content knowledge and training ability. By observing them as both participants and trainers, U.S. instructors can focus on areas of improvement during three TOT sessions.

An APRRP medical LOE is considered institutionalized by a PN when the PN has independently conducted at least two iterations of the course after completion of the APRRP-led three iterations. This demonstrates the PN’s commitment to continue training an LOE, including, but not limited to, identifying people who need to be trained, organizing the logistics and administration for additional iterations, adapting the agenda and curriculum, and applying resources to successfully execute those iterations. This case study illustrated a good example of how the SAF institutionalized the APRRP field sanitation LOE and has continued to increase the capability by building the FSC instructor capacity. Ross explained “Institutional capacity-building is the most often neglected element of capability generation, yet it is the element most vital to ensuring enduring capability.”11 When conducting DoD GHE activities, utilizing the “Crawl, Walk, Run” training model whenever possible, can provide the PN a better chance to build not only the capability but also the capacity for the specific LOE.

Sustainability is whether a PN can train an LOE independently, while institutionalization is whether a PN does train an LOE independently. Sustainability means that PN instructors have the content knowledge and pedagogical capabilities that allow them to conduct a specific training LOE, such as FSC, without external support. Furthermore, institutionalizing a specific training LOE means that the PN has developed a strategy to ensure that it is conducting future iterations of that training without external support. A PN needs to establish a plan to train additional personnel and, eventually, other trainers.

Challenges With Using The “Crawl, Walk, Run” Training Model

Long Periods of Time between Iterations

Iterations should be conducted 6 to 8 weeks apart in order to reduce the chances for PN instructors to lose the content knowledge and skills learned in prior iterations. However, this may not always be feasible due to a number of challenges such as scheduling conflicts, coordination issues, or travel constraints (i.e., COVID-19). A major challenge involves preparing and organizing the course iterations within the desired time frame. Scheduling conflicts with PNs and the vetting process for participants can also lead to longer than intended periods between iterations.

Inconsistency of U.S. Instructors and PN participants

Reviewing training materials detracts from course continuity when PN instructors cannot or do not return for subsequent iterations. PN instructors cannot attend for various reasons. If many of the PN instructors do not return for a subsequent training iteration, the U.S. and remaining PN instructors spend an inordinate amount of time reviewing TOT materials (lesson planning and skills station), roles and responsibilities, etc. The additional time spent to review course materials with new PN instructors significantly detracts from critical time needed to develop sustainable training knowledge and skills with the continuing PN instructors.

When U.S. instructors do not return for subsequent iterations, the TOT process with PN instructors can impact the overall success of the training. The TOT portion of APRRP courses provides U.S. instructors the opportunity to continue building rapport with PN instructors. If the same U.S. instructors do not return for a subsequent iteration, PN instructors have to build rapport with a new U.S. instructor and understand a new communication and/or mentorship style. The inability to maintain the same U.S. instructors throughout training execution poses continued challenges due to the realities of DoD operational tempo such as changes in mission and frequent personnel turnover. Furthermore, a new U.S. instructor may not have the same PN experience or a clear understanding of the varied training styles and cultures within that PN. Whenever possible, the same U.S. instructors should train and mentor during all iterations of an APRRP course.

Funding Considerations

Most APRRP medical training courses utilizing the “Crawl, Walk, Run” training model, will have at least three iterations based on the funding received. In some cases, due to the challenges mentioned, the need for additional iterations may be warranted but funding may limit the numbers of iterations conducted. PN instructors can lose training continuity if there is no follow-up activity or supplemental training after the third and final iteration of an APRRP course. After three iterations, continuous communications with the PN leadership can be beneficial and must be considered by DoD GHE planners as a means to continue the longevity of success. In these communications, PN leadership can be encouraged to support PN instructors to continuously and independently conduct the training for other PN personnel. However, PN instructors can face difficulty with implementing the training within their military training context without the support from their leadership. DoD GHE planners can leverage the already existing partnership and relationship to further advance training objectives with PNs.

Conclusion

In Ross’ article, he noted “Too often, U.S. military capacity-building efforts have failed to deliver sustainable, effective partner capabilities that truly ease operational burdens on U.S. forces. In a time of fiscal austerity, the DoD must examine how it can do better with the limited resources available.”11(p26) The SAF case study, as illustrated in this article, clearly provides a good example that DoD GHE activities, not only can be an effective security cooperation tool, but if executed using a “Crawl, Walk, Run” training methodology, can also enhance PN medical capacity and capabilities. Medical activities executed through the APRRP program support U.S. national security objectives by helping to build long-term public health capacity of allies and contribute to helping PNs achieve their goals to enhance their medical and training capabilities, especially as it pertains to rapid deployment. The “Crawl, Walk, Run” training model demonstrates an excellent teaching method that develops PN instructors so they can train more personnel in the long-term, thus building both capacity and capability. This gives the PN the opportunity to sustainably institutionalize a course, allowing them to continue training it in perpetuity.

To increase the success of DoD GHE activities when training PNs, planners need to implement this training model. This would ensure the PN has the capability to institutionalize a course and independently train future cohorts through internal iterations of the course. In addition, conducting virtual engagements can help increase the PN’s institutional capacity and provide DoD GHE planners the opportunity to continue relationships with the PN in the specific content-area when in-person activities cannot be conducted. The “Crawl, Walk, Run” training model APRRP employs can be successfully replicated across other DoD GHE programs and can serve as an example for how to enhance the content-area and training capabilities of U.S. partners and allies.

Acknowledgments

None declared.

Contributor Information

Graham J Button, The Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Bethesda, MD 20817, USA; Center for Global Health Engagement, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD 20814, USA.

Michael Acosta, The Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Bethesda, MD 20817, USA; Center for Global Health Engagement, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD 20814, USA.

LTC Sueann Ramsey, Center for Global Health Engagement, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD 20814, USA.

Yara Francis, The Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Bethesda, MD 20817, USA; Center for Global Health Engagement, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD 20814, USA.

Scott Zuerlein, The Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Bethesda, MD 20817, USA; Center for Global Health Engagement, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD 20814, USA.

Funding

None declared.

Conflict Of Interest Statement

None declared.

References

- 1. Bosetti T, Bridges D: The unit field sanitation team: a square peg in a round hole. US Army Med Dep J 2009; 1(2): 31–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mikesell HL: Teaching field sanitation to troops in the field. Mil Surg 1942; 90(4): 401–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3. DoD Instruction 2000 : 30 Global Health Engagement (GHE) activities. Available at https://fas.org/irp/doddir/dod/i2000_30.pdf; accessed April 27, 2021.

- 4. U.S. Department of State Fact Sheet : U.S. peacekeeping capacity building assistance. Available at https://www.state.gov/u-s-peacekeeping-capacity-building-assistance/, April 20, 2021; accessed April 20, 2021.

- 5. Secretary of Defense Memorandum : Message to the force. Available at https://media.defense.gov/2021/Mar/04/2002593656/-1/-1/0/SECRETARY-LLOYD-J-AUSTIN-III-MESSAGE-TO-THE-FORCE.PDF, March 4, 2021; accessed March 4, 2021.

- 6. Wampler RL, Dyer JL: Training lessons learned and confirmed from military training research. U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences. Available at https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a446697.pdf, April 2006; accessed February 27, 2021.

- 7. Byrne TJ, Hurst CG, Madsen JM, et al. : Graduate Education and simulation training for CBRNE disasters using a multimodal approach to learning part 1: education and training from a human- performance perspective. U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense. Available at https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA593215.pdf, August 2013; accessed February 27, 2021.

- 8. United Nations Peacekeeping : United Nations Peacekeeping Troop and Police Contributors ranking of contributions by country (as of 28 February 2021). United Nations Peacekeeping Troop and Police Contributors, United Nations Peacekeeping. Available at https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/troop-and-police-contributors, February 28, 2021; accessed April 27, 2021.

- 9. Correll DS: Senegal, Ghana employ medical training from U.S. military to respond to COVID-19. Military Times. Available at https://www.militarytimes.com/news/coronavirus/2020/04/07/senegal-ghana-employ-medical-training-from-us-military-to-respond-to-covid-19/, April 2020; accessed April 20, 2021.

- 10. Natsios AS: The nine principles of reconstruction and development. Parameters 2005; 35(3): 9–10. Available at https://press.armywarcollege.edu/parameters/vol35/iss3/12; accessed February 27, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ross TW: Enhancing security cooperation effectiveness, a model for capability package planning. JFQ 2016; 80(1): 25–34. [Google Scholar]