Abstract

Background

As globalization of surgical training increases, growing evidence demonstrates a positive impact of global surgery experiences on trainees from high-income countries (HIC). However, few studies have assessed the impact of these largely unidirectional experiences from the perspectives of host surgical personnel from low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). This study aimed to assess the impact of unidirectional visitor involvement from the perspectives of host surgical personnel in Kijabe, Kenya.

Methods

Voluntary semi-structured interviews were conducted with 43 host surgical personnel at a tertiary referral hospital in Kijabe, Kenya. Qualitative analysis was used to identify salient and recurring themes related to host experiences with visiting surgical personnel. Perceived benefits and challenges of HIC involvement and host interest in bidirectional exchange were assessed.

Results

Benefits of visitor involvement included positive learning experiences (95.3%), capacity building (83.7%), exposure to diverse practices and perspectives (74.4%), improved work ethic (51.2%), shared workload (44.2%), access to resources (41.9%), visitor contributions to patient care (41.9%), and mentorship opportunities (37.2%). Challenges included short stays (86.0%), visitor adaptation and integration (83.7%), cultural differences (67.4%), visitors with problematic behaviors (53.5%), learner saturation (34.9%), language barriers (32.6%), and perceived power imbalances between HIC and LMIC personnel (27.9%). Nearly half of host participants expressed concerns about the lack of balanced exchange between HIC and LMIC programs (48.8%). Almost all (96.9%) host trainees expressed interest in a bidirectional exchange program.

Conclusion

As the field of global surgery continues to evolve, further assessment and representation of host perspectives is necessary to identify and address challenges and promote equitable, mutually beneficial partnerships between surgical programs in HIC and LMIC.

Introduction

Despite advances in global health, an estimated five billion people lack access to safe and affordable surgical care worldwide [1]. The 2015 Lancet Commission on Global Surgery outlined the need for increased access to surgical care and recommended incorporation of global surgery initiatives into the global health agenda [2]. The field of global surgery has since gained recognition among academic surgeons [3–5]. In response to growing interest in global surgery, many residency programs in high-income countries (HIC) have developed international rotations in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) [6]. In the USA, this effort was further supported when the Residency Review Committee, American Board of Surgery, and Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) approved international electives for credit toward graduation requirements [7]. By 2016, 34% of US general surgery residency programs offered international experience for their trainees, and this number continues to rise [8].

Several studies have assessed the impact of unidirectional global surgery experiences, citing benefits for visiting trainees including career development, high case volume, improved cost awareness, research opportunities, and increased cultural competency [9–23]. Additionally, residents from HIC have reported increased likelihood of pursuing global health activities, serving domestically underserved populations, and participating in other forms of service after completing an international rotation [24–26].

Although growing evidence demonstrates a positive impact of global surgery rotations on trainees from HIC, critics have criticized these efforts as neo-colonialist, self-serving endeavors [27–29]. Few studies have assessed the impact of unidirectional global health experiences from the perspectives of host personnel from LMIC [30–34]. Even fewer have assessed host trainee perspectives or host perspectives related to global surgery experiences [35–37]. A recent qualitative meta-ethnography assessing resident rotations in LMIC identified only 4 studies assessing host perspectives of HIC collaboration with a combined total of 25 LMIC surgeons and 20 LMIC surgical trainees represented in these studies [38–42].

As globalization of medical education and practice continues, additional studies are needed to understand LMIC perspectives regarding unidirectional global surgery experiences [43]. Several studies and working groups have emphasized the need for reciprocity, bidirectional partnerships, and equitable exchange between HIC and LMIC and have urged for more balanced assessment of host perspectives and needs [44–52]. This study aims to determine the impact of visiting trainees and faculty on surgical care and training at AIC Kijabe Hospital from the perspective of host surgical trainees and faculty.

Methods

All host surgical faculty and trainees at AIC Kijabe Hospital were invited to participate in voluntary interviews. Study participants were recruited using email and WhatsApp platforms. Surgical trainees included surgical residents and fellows. Medical officer interns, clinical officer interns, and clinical officers who had completed surgery rotations were also invited to contribute. Appendix 1 includes a description of AIC Kijabe Hospital, medical training in East Africa, and roles of surgical providers and trainees included in this study.

Verbal informed consent was obtained prior to data collection. Participant demographic information was collected and stored in a secure, web-based Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database [53, 54]. Interviews were conducted in English by a visiting medical student (CNZ) using an open-ended, semi-structured interview guide (Appendix 1) developed by researchers from the US (CNZ, RMK) and Kenya (JJ, JBAM). Interviews took place in private locations on the hospital campus or via phone if in-person interviews were not possible. Interviews were audio recorded and stored in an encrypted interface. Audio files were transcribed using Temi software and verified for accuracy by two members of the research team (CNZ, DEP). Personal identifiers were removed during the transcription process and prior to data analysis.

Qualitative content analysis was used to identify salient and recurring themes related to host experiences with visiting personnel. Interviews were independently coded by at least one researcher from the US and one from Kenya. Disagreements in coding were resolved by discussion, and codes were refined and axially coded into overarching themes [55–57]. MAXQDA software was used to organize codes, extract code frequencies, and retrieve representative interview excerpts. Code frequencies were defined as the proportion of interviews to which the code was applied (as opposed to the absolute frequency of theme expression) to prevent overrepresentation of themes repeatedly expressed by a single interviewee. Quantitative data were summarized using descriptive statistics.

Results

Forty-three host personnel completed interviews: 11/17 surgical faculty, 2/2 surgical fellows, 17/21 surgical residents, 11/14 medical officer interns, 1 plastic surgery clinical officer, and 1 clinical officer intern on a surgery rotation. Most participants identified as male (72.1%) and Kenyan (72.1%) with a median age of 30.0 years (IQR 26.5–35.5). Collectively, participants indicated 11 home countries, 28 spoken languages, and 6 surgical specialties. Host participant demographics are summarized by level of training in Table 1.

Table 1.

Host participant demographics

| All (N = 43) n (%) |

Faculty (N = 11) n (%) |

Trainees (N = 19) n (%) |

Other (N = 13) n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, Median (IQR) | 30.0 (26.5–35.5) | 38.0 (35.5–40.0) | 31.0 (29.0–33.5) | 25.0 (25.0–26.0) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 31 (72.1%) | 9 (81.8%) | 17 (89.5%) | 5 (38.5%) |

| Female | 12 (27.9%) | 2 (18.2%) | 2 (10.5%) | 8 (61.5%) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 20 (46.5%) | 10 (90.9%) | 10 (52.6%) | – |

| Single | 23 (53.5%) | 1 (9.1%) | 9 (47.4%) | 13 (100.0%) |

| Race | ||||

| Black/African | 41 (95.3%) | 9 (81.8%) | 19 (100.0%) | 13 (100.0%) |

| White/Caucasian | 2 (4.7%) | 2 (18.2%) | – | – |

| Home Country | ||||

| Kenya | 31 (72.1%) | 8 (72.7%) | 11 (57.9%) | 12 (92.3%) |

| Other African Country* | 9 (20.9%) | – | 8 (42.1%) | 1 (7.7%) |

| Non-African Country** | 3 (7.0%) | 3 (27.3%) | – | – |

| Total languages spoken per person (mean ± SD) | 3.5 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 3.9 ± 1.1 | 3.3 ± 0.8 |

| Common languages† | ||||

| English | 43 (100.0%) | 11 (100.0%) | 19 (100.0%) | 13 (100.0%) |

| French | 11 (25.6%) | 1 (9.1%) | 6 (31.6%) | 4 (30.8%) |

| Kikuyu | 13 (30.2%) | 4 (36.4%) | 5 (26.3%) | 4 (30.8%) |

| Luhya | 5 (11.6%) | 2 (18.2%) | 1 (5.3%) | 2 (15.4%) |

| Luo | 5 (11.6%) | – | 4 (21.1%) | 1 (7.7%) |

| Swahili (Kiswahili) | 41 (95.3%) | 11 (100.0%) | 17 (89.5%) | 13 (100.0%) |

| Surgical specialty†† | ||||

| General surgery | 13 (43.3%) | 6 (54.5%) | 7 (36.8%) | – |

| Head and neck surgery | 1 (3.3%) | 1 (9.1%) | – | – |

| Orthopedic surgery | 12 (40.0%) | 3 (27.3%) | 9 (47.4%) | – |

| Pediatric surgery | 4 (13.3%) | 1 (9.1%) | 3 (15.8%) | – |

| Plastic surgery | 1 (3.3%) | 1 (9.1%) | – | 1 (7.7%) |

| Urology | 2 (6.7%) | 2 (18.2%) | – | – |

*Other African countries included Congo (n = 2), Botswana (n = 1), Burundi (n = 1), Gambia (n = 1), Rwanda, (n = 1), South Sudan (n = 1), Tanzania (n = 1), and Uganda (n = 1)

**Non-African countries included the United States (n = 2) and Canada (n = 1)

†Other languages spoken by host participants included Kamba (n = 4), Sheng (n = 4), Kinyarwanda (n = 2), Meru (n = 2), Spanish (n = 2), Dinka (n = 1), Fulani (n = 1), German (n = 1), Hausa (n = 1), Jola (n = 1), Kalenjin (n = 1), Kirundi (n = 1), Kissi (n = 1), Lingala (n = 1), Luganda (n = 1), Mandinka (n = 1), Mandjaque (n = 1), Runyankore (n = 1), Russian (n = 1), Somali (n = 1), Tswana (n = 1), and Wolof (n = 1)

††Three surgical faculty identified more than one surgical specialty: General Surgery and Head and Neck Surgery (n = 1), General Surgery and Urology (n = 2)

Participants recounted experiences with visitors from Canada, Mexico, the USA, Australia, the UK, Germany, Italy, Spain, Israel, China, Korea, Malaysia, and India. Given the high turnover and diversity of visitors hosted by Kijabe Hospital, some participants could not recall specific institutions from which visitors came. Consequently, the following themes are reflective of experiences with all visiting faculty and residents from HIC and are not specific to a single institution.

Host-perceived benefits

Positive learning experiences (95.3%) were an almost unanimously cited benefit of visitor involvement and included expressions about visitors being approachable, patient teachers who granted learners increased autonomy. Capacity building was also commonly described (83.7%), including surgical (72.1%), clinical (53.5%), and research (16.3%) skills. Surgical capacity building often involved sub-specialty procedures and minimally invasive techniques, while clinical capacity building included comparison of clinical practice, diagnostic evaluation and interpretation, clinical teaching on rounds, and management of surgical complications. Participants described gaining enriched, broadened perspectives (74.4%) including exposure to evidence-based medicine, theoretical or textbook topics that do not commonly present in LMIC, high-resource protocols and systems, and different technologies. Participants also expressed that visitors positively influenced host trainee work ethic (51.2%), helped to reduce host workload (44.2%), and made positive contributions to patient care (41.9%). Host participants described access to resources (41.9%) such as donated equipment and educational resources, however donation of expired equipment led to feelings of discomfort among some participants. Lastly, several participants described mentorship opportunities (37.2%) that inspired confidence and provided encouragement related to professional development and career aspirations. Frequencies and representative excerpts of host-perceived benefits expressed by > 20% of participants are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Host-perceived benefits of HIC involvement in Kijabe Hospital

| Themes | Frequency | Representative excerpts |

|---|---|---|

| Positive learning Experiences | 41 (95.3%) |

“They teach you, they teach you, they teach you. And if you don't understand, they still want to sit with you. Tell you this is what we should do on this condition. They make you like you think wide, think out of the box.” – Clinical Officer Intern “I enjoyed working with all the residents I got to work with because most of them had the gift of teaching, if I may put it that way.” – Resident |

| Approachable teachers | 12 (27.9%) | |

| Skilled teachers | 10 (23.3%) | |

| Increased autonomy | 9 (20.9%) | |

| Humble teachers | 8 (18.6%) | |

| Patient teachers | 5 (11.6%) | |

| Capacity building | 36 (83.7%) |

“Their objectives were to come and increase our capacity, specifically in more complex cases such as free flap surgery.” – Faculty “I learned most of my surgical skills, you know, ties and how to hold the instrument from the resident, the visiting resident.” – Resident |

| Surgical skills | 31 (72.1%) | |

| Clinical skills | 23 (53.5%) | |

| Research skills | 7 (16.3%) | |

| Broader perspectives | 32 (74.4%) |

“[We] are used to the usual Kenyan system of doing stuff. But you meet people who have a different perspective, and…it makes you integrate the two systems.” – Resident “So, there's a lot of stuff we learn in theory which we don't do here. A lot of technology, a lot of latest things people are doing we don't do. So, I think now when you have residents, they tell us this is what we do and this is it. So at least it's nice to hear it from someone who's actually done it rather than just reading books.” – Faculty |

| Evidence-based medicine | 9 (20.9%) | |

| Theoretical/Textbook topics | 7 (16.3%) | |

| High-resource systems | 6 (14.0%) | |

| Different technology | 4 (9.3%) | |

| Improved work ethic | 22 (51.2%) |

“They really showed great commitment to the patients. And they gave their very all, their time, and their experience and knowledge. And they pushed us to do the same, to make sure we were giving our very best to our patients.” – Medical Officer Intern “Again, their work ethic. They go the extra mile. They say there is no traffic on the extra mile, so they are willing to drive through it. I've slept in theater with one of them because of a very busy night when the rest of the country was on strike, and I really am glad about that.” – Resident |

| Shared workload | 19 (44.2%) |

“[Visiting] faculty would come to assist us in covering when we're away, when we're on conferences, when we're on holidays, when we're on our home assignments. So, we'll have faculty come out and help cover. So, I think that's been valuable…” – Faculty “Here in Kijabe we are a bit, there are times we are short staffed, especially when you have some of our local surgeons or local doctors going on leave…we tend to become short staffed. So, when we have some visiting consultants, or residents, or even medical students, they tend to sort of help balance the load.” – Medical Officer Intern |

| Faculty coverage | 15 (34.9%) | |

| Access to resources | 18 (41.9%) |

“They also help us bring like…donated implants and equipment, which is a big help. But that's the consultants who help us with that.” – Faculty “In terms of access to papers, they shared a lot of that with us.” – Resident |

| Donated equipment | 12 (27.9%) | |

| Educational materials | 5 (11.6%) | |

| Contributions to patient care | 18 (41.9%) |

“Vascular surgery is not something we would typically do here. So, it's important to acknowledge those kinds of cases where patients get sub specialized care, which they wouldn't otherwise get from our local faculty.” – Resident “[A] lot of them come as missionaries, in my opinion. Maybe missionaries in terms of missionary doctors to reach out to maybe the vulnerable communities, that is one. And then, and offer maybe free services as volunteers, volunteer doctors.” – Medical Officer Intern |

| Specialty services | 10 (23.3%) | |

| Free services | 3 (7.0%) | |

| Mentorship | 16 (37.2%) |

“And therefore, as an individual, I really appreciate their presence. I've told you that they have already influenced my practice from the time I was a young medical student up to now.” – Faculty “And also, their encouragement. They also want to give you their personal experience, where they have been in US, how they started their residency, how it is, the life of residents when you are outside, you know Africa. So those kinds of experiences make you understand that you're not alone, and they've gone through it.” – Resident |

| Confidence | 8 (18.6%) | |

| Encouragement | 6 (14.0%) |

Host-perceived benefits that were expressed by > 20% of participants are shown in bold with sub-codes listed below each major benefit. Sub-codes are not mutually exclusive and thus should not necessarily add up to 100%

Host-perceived challenges

Short duration of stay (86.0%) and visitor adaptation and integration (83.7%) were the most commonly expressed challenges. Most participants felt that longer stays would be more beneficial, and some felt that short stays led to inadequate post-operative care for patients. Assimilation challenges included visitor adaptation to the following: differences in hospital systems, resource allocation protocols, surgical techniques, and differences in scope of practice between HIC and LMIC, which sometimes led to inefficiencies in workflow and patient care.

Cultural differences (67.4%), language barriers (32.6%), and perceived power imbalances between individuals from HIC and LMIC (27.9%) were also commonly expressed challenges. Some participants perceived Western visitors to be confrontational or condescending. Differences in work ethic, though more commonly cited as a positive influence (51.2%), were also viewed as a cultural challenge (20.9%) that negatively impacted clinical team dynamics. Cultural concerns included lack of adherence to local hierarchies and cultural awareness, mistrusting host abilities, and perceived racial biases. Some also felt that cultural differences and language barriers led to reluctance of auxiliary staff to approach visitors with clinical questions.

Participants also expressed concerns about visitors with problematic behaviors (53.5%), which commonly involved isolated interpersonal conflicts. Concerns were also raised about visitors who performed procedures outside of their usual scope of practice or who did not adhere to HIC standards of care in LMIC, which was perceived to lead to worse patient outcomes.

Several participants (48.8%) expressed concerns about the lack of balanced exchange and felt that unidirectional global surgery rotations were more beneficial for visiting trainees than for host trainees. Another perceived challenge was learner saturation (34.9%), particularly regarding case distribution in the operating room. Although case volumes were not affected, some participants felt host residents were demoted if a visiting resident was present. Frequencies and representative excerpts of host-perceived challenges expressed by > 20% of participants are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Host-perceived challenges of HIC involvement in Kijabe Hospital

| Themes | Frequency | Representative excerpts |

|---|---|---|

| Short duration of stay | 37 (86.0%) |

“But there's something that one of my colleagues called brisk surgery, where you come and operate a lot of patients and then you don't follow them. So, one-two weeks, three weeks, one month is rather too short to commit one to medical work.” – Faculty “I think [visitors’ stay] should be longer because one month time is the time you learn someone. You learn them, what they do. You learn what they like. You learn what they're skilled in, you know what kind of surgeries they do best. And then before you realize they are going back.” – Resident |

| Longer stays are beneficial | 23 (53.5%) | |

| Inadequate follow up care | 7 (16.3%) | |

| Visitor adaptation | 36 (83.7%) |

They're here for a very short time, which means they have to learn the system so quickly and adapt to the system so quickly. And it means, it's a totally different system. There's a new language and everything. So sometimes it's frustrating and by the time they just learn the system and how to work with everyone, they're gone. Yes. So that's with residents. They're here for a short time. – Faculty “So, you find the whole pathway kind of becomes complicated and it takes a bit of a long time because if, say a patient comes in with a burr hole, here we are supposed to do burr holes. The senior resident does the burr holes. But for them I think they're not used to burr holes. So that loop, that whole loop takes a bit of time and they think if you're a junior resident spending your time between 9:00 PM and 12 midnight, you're still not getting through very well, I think it wastes quite a bit of time.” – Resident |

| Different hospital system | 25 (58.1%) | |

| Different resource allocation | 8 (18.6%) | |

| Different scopes of practice | 7 (16.3%) | |

| Different surgical techniques | 7 (16.3%) | |

| Inefficiencies in patient care | 4 (9.3%) | |

| Cultural differences | 29 (67.4%) |

“The other thing is understanding the cultural conflicts. By nature, I think the American culture is confidence. Go out, say what you want. By nature, the African culture is very reserved, very conservative, very withdrawn…But when [visiting residents] come over, they still become dominant. Not because they didn't give the Kenyan resident an opportunity, but the assertive nature of the American resident naturally leads to a withdrawal of the Kenyan resident…” – Faculty “One I think is just maybe clash of cultures. The way of expression in different cultures is different from ours. So sometimes some visitors may seem brazen or harsh in how they express themselves. And also, maybe the systems here may be slower or less efficient, and they get frustrated with that.” – Resident |

| Confrontational visitors | 16 (37.2%) | |

| Condescending visitors | 15 (34.9%) | |

| Work ethic | 9 (20.9%) | |

| Power distance and hierarchy | 5 (11.6%) | |

| Problematic behaviors | 23 (53.5%) |

“There's one particular person I'm thinking of who, I won't mention his name, but there were conflicts in almost every area. – Faculty “One of the visiting consultants openly mentioned how all the stuff he brought for surgeries were all expired. And we were like, ‘Oh wow. But you're okay having our patients here use what is expired product from your clinic?’ So anyway, I remember all of us sort of being very uncomfortable with that.” – Resident |

| Interpersonal conflicts | 8 (18.6%) | |

| Selfish motives | 4 (9.3%) | |

| Unwilling to adapt | 4 (9.3%) | |

| Unwilling to learn | 4 (9.3%) | |

| Lowering standards of care | 3 (7.0%) | |

| Working outside scope | 3 (7.0%) | |

| Lack of balanced exchange | 21 (48.8%) |

“The connection with [academic institution] has been, we've tried to make this program where it's two way, but it's difficult. It's difficult for [academic institution] to know how they can help us…I suspect they're getting more out of it than we are.” – Faculty “We don't really get the impact of what their program is like or where they're from is like in a period of a month. They get to benefit a lot more from us, they get to see a lot more of what we do.” – Resident |

| Learner saturation | 15 (34.9%) |

“A problem I've noted is that…when they're here, a similar level resident who is a local, a person who's training here, the visiting resident may be given more responsibilities than the local resident, which we feel is not appropriate. And they may be given preference, especially if it's an interesting case or a different or a difficult case. They may be given preference in terms of scrubbing as either first assistant or lead surgeon over a local resident.” – Resident “The case load doesn't change, but the role changes. Because you can scrub in the same case, but your role is now reduced to a second assistant”. – Resident |

| Case distribution | 14 (32.6%) | |

| HIC residents get preference | 7 (16.3%) | |

| HIC residents take cases | 5 (11.6%) | |

| LMIC residents get demoted | 5 (11.6%) | |

| LMIC residents get preference | 5 (11.6%) | |

| Language barriers | 14 (32.6%) |

“The only concern that happens is the language. When they come here for the first time, mostly those who have never been to Africa, when they come for the first time, it's very difficult to understand them. And then some Kenyans or Africans they don't, they will not ask you to repeat. So, they will just try to see and they go ask someone else, ‘Did you hear what did he say?’” – Fellow “Language barrier is a big deal. I've had staff come to me and say, ‘We don't understand what they want or what they're saying.’” – Resident |

| Power imbalwance | 12 (27.9%) |

“I've not had a discussion in that direction with any of [the visitors] because when somebody comes and is doing voluntary work, you don't want to challenge their position, whatever position they take.” – Faculty “There is a sense of respect that is probably accorded more to a Westerner. And so, things might work out for them better in terms of like maybe if they give orders or if they are trying to ask questions or trying to seek for assistance, it may be easier for them because of that respect that we generally have for Westerners.” – Medical Officer Intern |

Host-perceived challenges expressed by > 20% of participants are shown in bold with sub-codes listed below each major benefit. Sub-codes are not mutually exclusive and thus should not necessarily add up to 100%

Host feedback and interest in bidirectional exchange

Many participants offered advice for future visitors, including cultural advice (95.4%) related to cultural humility (72.1%), pre-visit preparation advice (58.1%), expressions of need for bidirectional exchange (48.8%), and appreciation for the opportunity to participate and discuss their experiences (41.9%). Frequencies and representative excerpts of host feedback and advice expressed by > 20% of participants are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Host Advice and Feedback for Visitors

| Themes | Frequency | Representative excerpts |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural advice | 95.3% |

“What I wish they would have known is hard to know without actually being here. And that's the culture. Yeah. It's very hard to communicate culture, you know, in an email or in a prepared document. But they made up for not knowing about the culture with their sort of flexibility and their willingness to learn.” – Faculty “Take time to know people. Learn from different cultures, experiences. Get to know them. Visit their homes. Don't come and silo yourself again amongst the missionary and white people.” – Faculty “Taking like Swahili class wouldn't be a bad idea…and I feel like it would make their life easier with the patients, with the staff who don't necessarily prefer to communicate in English or are not as fluent in it. And plus, if you, if people feel like you understand the language, I think they open up to you better and you get to understand even the subtle things.” – Resident |

| Cultural humility | 72.1% | |

| Relationships with locals | 51.2% | |

| Power distance | 44.2% | |

| Cultural exchange | 30.2% | |

| Information about Kijabe | 25.6% | |

| Cultural awareness | 23.3% | |

| Learn the local language | 23.3% | |

| East African conflict aversion | 14.0% | |

| Explore the country | 14.0% | |

| Slow down, go with the flow | 11.6% | |

| Pre-visit preparation | 58.1% |

“One of the things I've found to be helpful is communication beforehand with those on the ground so that by the time you come you know the people you're gonna meet and maybe even the kind of cases that would be tackled.” – Faculty “Maybe just a general orientation on the hospital side, on patient care. Like these are the medications we have, this is the frequent kind of diseases that we deal in our set up, and these are our protocols in regards to management of these, so that when we are seeing patients, we are at the same, at the same level.” – Medical Officer Intern |

| Pre-visit communication | 25.6% | |

| Define roles and objectives | 18.6% | |

| Orientation materials | 34.9% | |

| Prepare teaching materials | 16.3% | |

| Bilateral information exchange | 48.8% |

“An exchange program is always good. And the reason is you learn from each other.” – Faculty “And it's the communication, there's no fight at all, but it's just exchange of information for the sake of the benefit of the patient.” – Resident |

| Appreciation for study | 41.9% |

“We often have exchange with different hospitals and different missionaries and others, but we have never been questioning what to do, how we can do better, and other things…It's the first time I find it questions, and that can help actually to improve the exchange and benefit from each side. I think that's great to have thought about doing such thing here.” – Fellow “Having visitors from [academic institution] let me be specific is a great resources to us, but at the same time also, having our opinions or asking us what we need is a good thing and we appreciate that.” -Resident |

Host feedback and advice expressed by > 20% of participants are shown in bold with sub-codes listed below each major benefit. Sub-codes are not mutually exclusive and thus should not necessarily add up to 100%

When subsequently asked if they would be interested in participating in a bidirectional exchange program, 31/32 (96.9%) surgical and other trainees expressed interested, and 11/31 (35.5%) said they would still be interested in an exchange program if their role in HIC was purely observational. Perceived barriers to bidirectional exchange included licensing logistics (58.1%), fear of brain drain (58.1%), financial barriers (55.8%), lack of existing exchange opportunities (32.6%), lack of support from LMIC training program (27.9%), and cultural political barriers (20.9%).

Discussion

Partnerships between surgery training programs in HIC and LMIC result in many benefits for host surgical trainees. However, hosts often perceive the benefits of these experiences to favor visiting trainees. Challenges also inherently arise owing to cultural differences, perceived power imbalances, high visitor turnover, and systemic differences in hospital protocols and resources. As relationships between surgical programs in HIC and LMIC evolve, additional documentation of successes and challenges as perceived by stakeholders from both LMIC and HIC is essential to identify and address new needs and challenges. After analyzing and reflecting on host interviewee responses, the following intercultural recommendations were developed.

Learner saturation, visitor fatigue, and longitudinal relationships

With increasing unidirectional global surgery rotations, caution must be taken to prevent learner saturation and mitigate visitor fatigue. Host programs should determine the maximum capacity of visitors they can accommodate without compromising the education of their own trainees. Visiting trainees and host faculty must ensure that the role of a host trainee does not change when a visiting trainee is present. Visitors should be cognizant of the perpetual cycle of guests in LMICs and the burden placed on host institutions to accommodate and integrate visitors into local systems. Strategies for minimizing visitor fatigue include establishing meaningful relationships with local surgical personnel and maintaining those relationships after returning home. Repeat visits and consistent, longitudinal involvement with institutions in LMIC can further reduce visitor fatigue. Mentorship, networking, and research collaborations were less commonly expressed benefits that represent additional opportunities for strengthening of longitudinal relationships between HIC and LMIC [27].

Systems awareness and cultural humility

Improvements in visitor pre-departure training and post-departure debriefing can maximize benefits and minimize challenges with visitor assimilation and cultural differences [58, 59]. Formal orientation materials and objectives should be developed with LMIC stakeholders and should incorporate information about LMIC hospital protocols, common surgical procedures, disease patterns, and roles of local healthcare providers. Cultural orientation curricula should emphasize cultural humility and promote acknowledgement of personal biases and recognition of power imbalances that contribute to unfair exchange between HIC and LMIC. Incorporation of cultural humility training led by people with prior experiences at host institutions can lead to improved experiences for both hosts and visitors and has been implemented at our institution [60, 61]. Additionally, improved communication with LMIC prior to visits can also allow for enhanced preparation and recruitment of patients; and continued communication during and immediately following visits can enhance peri- and post-operative care for patients [27, 37, 45].

Ethical patient care and donation of surgical equipment

Although visitors may reduce host workload and contribute to patient care, the short-term nature of visitor involvement and differences in clinical protocols and scope of practice between HIC and LMIC can lead to inefficiencies in management, poor post-operative follow up, and even poor outcomes if visitors work outside of their usual scope of practice. Institutions in HIC and LMIC should devise strategies to ensure that visitors are aware of local protocols and are not working outside their scope of practice unless appropriate support is provided. Additionally, use of video communication platforms popularized during the COVID-19 pandemic could allow for virtual visitor participation in post-operative management and surgical audits to ensure high-quality outcomes for patients [62].

Furthermore, as described by one study participant, the provision of “expired” donations to hospitals in LMIC contributes to perceived power imbalances between HIC and LMIC and has vast ethical implications. A recent study showed that up to 70% of donated medical devices have minimal utility in LMIC due to lack of function, appropriateness, or staff training [63]. While donations of surgical equipment can improve access to surgical care in low-resource settings, they should be discussed with LMIC faculty and made in accordance with international guidelines to ensure maximum safety, equity, and utility of donated items [45, 63, 64].

From unidirectional capacity building to bidirectional exchange

With progressive globalization of surgical education, the role of visitors from HIC must shift from one of purely teaching (criticized as neocolonialist hegemony), purely serving (criticized as a savior mentality), or purely learning (criticized as self-serving or experimenting on vulnerable populations) to one of mutual reciprocity and equitable bidirectional exchange opportunities for trainees [27, 44–52, 65]. Few bidirectional exchange programs have been described in the literature, most of which involve LMIC junior faculty or medical students [66, 67]. Some pediatric and internal medicine residency programs have also developed exchange programs with LMIC partner institutions [68–70]. However, few surgical training programs have developed such exchange programs [49, 70–75]. A 2020 systematic review of surgical training partnerships between HIC and LMIC by Price et al. found that only one partnership offered bidirectional exchange and only two offered South-to-North exchange. Barriers to bidirectional included licensing logistics, fear of brain drain, and financial burdens placed on LMIC trainees [49, 76]. Significant effort will be required to overcome financial and sociocultural barriers to developing equitable partnerships and bidirectional or South-to-North opportunities for trainees from LMIC.

Limitations

Although English is the national language of Kenya, it was not the primary language of all interviewees, which may have led to communication errors during interviews. It is also possible that perceived power imbalances between HIC and LMIC may have hindered free host expression, though this was mitigated by having a visiting student who is lower on the medical hierarchy conduct interviews. Furthermore, this study was conducted at a single tertiary care hospital in Kenya with long-standing collaboration with visitors from HIC. Thus, our results may not be generalizable to all collaborations between HIC and LMIC. However, the themes expressed in this study have relevance to many such collaborations and may be even more pronounced at institutions without longitudinal partnerships with visitors from HIC.

Conclusion

Partnerships between surgical departments and training programs in HIC and LMIC have the potential to result in numerous benefits for both host and visiting faculty and trainees. As the field of global surgery continues to gain momentum, further assessment and representation of host perspectives is necessary to maximize benefits, address challenges, and promote equitable partnerships between HIC and LMIC.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge all individuals from AIC Kijabe Hospital who participated in interviews or who have been involved in hosting visitors from Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC). We also thank John Tarpley, Maggie Tarpley, Kyla Terhune, Erik Hansen, Amanda Hansen, Peter Bird, and Beryl Akinyi for their efforts to establish and maintain the partnership between VUMC and AIC Kijabe Hospital that allowed for the development and continuation of a global surgery rotation for VUMC general surgery residents. Furthermore, we would like to thank the VUMC Section of Surgical Sciences, the AIC Kijabe Hospital Department of Surgery, the Medical Scholars Program at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, and the Vanderbilt Institute of Global Health for their support of this project. Finally, we would like to thank Nick Carter, Gretchen Edwards, Liz Nelson, and Maren Shipe from the Vanderbilt General Surgery Residency Program for providing feedback about their experiences at AIC Kijabe Hospital that was used to generate preliminary questions for our semi-structured interview guide, and Gretchen Jackson, Gretchen Edwards, Carolyn Audet, Chelsea Shikuku, Sarah Rachal, and Sandra Huynh, for their feedback regarding project design, data analysis, and manuscript development.

Appendix

Sample questions from semi-structured interview guide

Describe the involvement of western visitors at Kijabe hospital

How often does Kijabe Hospital have visitors from other countries?

What countries do they typically come from?

How long do these visitors typically stay? Is this amount of time adequate?

What do the hospital staff think about visiting health care providers?

Why do you think Western visitors come to Kijabe Hospital?

Describe your experience working with visiting residents

Did you enjoy working with them?

How did you feel when you worked with them?

What did you like about working with them?

What did you not like about working with them?

What were the challenges of working with them?

Did you learn anything from them?

What did they learn from you?

Did working with them benefit you? How so?

Was there anyway that they could have been more helpful?

Is there anything you wish they did differently?

Is there anything you wish they knew before they came to Kijabe?

Describe your experience working with visiting consultants

•Did you enjoy working with them?

•How did you feel when you worked with them?

•What did you like about working with them?

•What did you not like about working with them?

•What were the challenges of working with them?

•Did you learn anything from them?

•What did they learn from you?

•Did working with them benefit you? How so?

•Was there anyway that they could have been more helpful?

•Is there anything you wish they did differently?

Bidirectional exchange

Are you interested in a bidirectional exchange program between Kijabe Hospital and Vanderbilt?

Miscellaneous and wrap up

Is there anything else that you would like to talk about that we haven’t discussed?

Description of east african training paradigm and roles of surgical providers

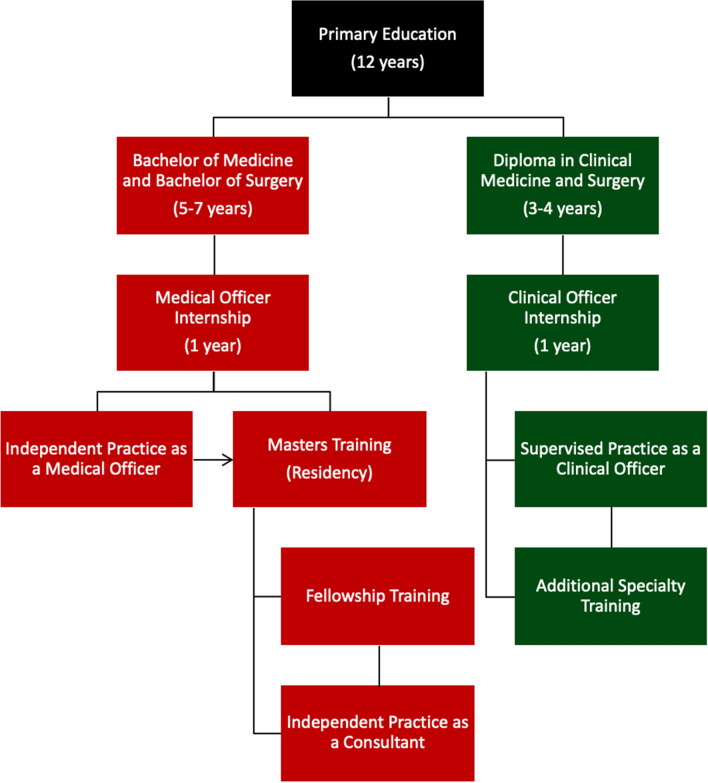

In Kenya, medical officers complete a six -year Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery followed by a one-year internship consisting of rotations in internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, and obstetrics and gynecology. Following internship, medical officers may begin independent medical practice. In addition to overseeing inpatient management, medical officers are expected to perform a wide range of surgical procedures such as Cesarean sections, appendectomies, hernia repairs, lumpectomies, traumatic lacerations and wound care and reduce closed fracture/dislocations. Some medical officers then opt to apply for residency training, after which they become consultants (analogous to attendings in the American medical system) and can pursue additional fellowships.

Clinical officers complete three to four years of training in Clinical Medicine and Surgery followed by a one-year internship similar to that of medical officers. Clinical officers provide a wide range of outpatient medical services including primary care, prenatal care, pre- and post-operative care, and minor surgical procedures such as suturing lacerations and I&D of abscesses. The East African medical training paradigm is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

East African Medical Training Paradigm

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alkire BC, Raykar NP, Shrime MG, et al. Global access to surgical care: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(6):e316–e323. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70115-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meara JG, Leather AJ, Hagander L, et al. Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet. 2015;386(9993):569–624. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60160-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farmer P, Meara JG. Commentary: the agenda for academic excellence in "Global" surgery. Surgery. 2013;153(3):321–322. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dare AJ, Grimes CE, Gillies R, et al. Global surgery: defining an emerging global health field. Lancet. 2014;384(9961):2245–2247. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60237-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shrime MG, Bickler SW, Alkire BC, et al. Global burden of surgical disease: an estimation from the provider perspective. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(Suppl 2):S8–S9. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70384-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell KB, Tarpley MJ, Tarpley JL, et al. Elective global surgery rotations for residents: a call for cooperation and consortium. World J Surg. 2011;35(12):2617–2624. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1311-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Margaret Knudson M, Tarpley MJ, Numann PJ. Global surgery opportunities for U.S. surgical residents: an interim report. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(4):e60–e65. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sobral FA, Bowder AN, Smith L, Ravipati A, Suh MK, Are C. Current status of international experiences in general surgery residency programs in the United States. Springerplus. 2016 doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2270-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang D, Siddiqui S, Weiss H, et al. Are we meeting ACGME core competencies? A systematic review of literature on international surgical rotations. Am J Surg. 2018;216(4):782–786. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harfouche M, Krowsoski L, Goldberg A, et al. Global surgical electives in residency: the impact on training and future practice. Am J Surg. 2018;215(1):200–203. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donley DK, Graybill CK, Fekadu A, et al. Loma linda global surgery elective: first 1000 cases. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(6):934–938. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henry JA, Groen RS, Price RR, Nwomeh BC, Peter Kingham T, Hardy MA, Kushner AL. The benefits of international rotations to resource-limited settings for U.S. surgery residents. Surgery. 2013;153(4):445–454. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bale AG, Sifri ZC. Surgery resident participation in short-term humanitarian international surgical missions can supplement exposure where program case volumes are low. Am J Surg. 2016;211(1):294–299. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolkman P, Soliman M, Kolkman M, et al. Comparison of resident operative case logs during a surgical oncology rotation in the United States and an international rotation in India. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2015;6(1):36–40. doi: 10.1007/s13193-015-0389-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cintolo-Gonzalez JA, Bedada AG, Morris J, et al. An international surgical rotation as a systems-based elective: the Botswana-University of Pennsylvania surgical experience. J Surg Educ. 2016;73(2):355–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2015.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ozgediz D, Wang J, Jayaraman S, et al. Surgical training and global health: initial results of a 5-year partnership with a surgical training program in a low-income country. Arch Surg. 2008;143(9):860–865. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.9.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klaristenfeld DD, Chupp M, Cioffi WG, et al. An international volunteer program for general surgery residents at Brown Medical School: the Tenwek Hospital Africa experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207(1):125–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silverberg D, Wellner R, Arora S, et al. Establishing an international training program for surgical residents. J Surg Educ. 2007;64(3):143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliphant JL, Ruhlandt RR, Sherman SR, et al. Do international rotations make surgical residents more resource-efficient? A prelim Study J Surg Educ. 2012;69(3):311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen S, Tadlock MD, Douglas T, et al. Integration of surgical residency training with US military humanitarian missions. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(5):898–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarman BT, Cogbill TH, Kitowski NJ. Development of an international elective in a general surgery residency. J Surg Educ. 2009;66(4):222–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobs MJ, Young SC, Mittal VK. Benefits of surgical experience in a third-world country during residency. Curr Surg. 2002;59(3):330–332. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7944(01)00624-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Love TP, Martin BM, Tubasiime R, et al. Emory global surgery program: learning to serve the underserved well. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(4):e46–e51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LeCompte MT, Goldman C, Tarpley JL, et al. Incorporation of a global surgery rotation into an academic general surgery residency program: impact and perceptions. World J Surg. 2018;42(9):2715–2724. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-4562-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flatow V, Trinidad SM, Zhang LP, et al. The effect of a global surgery resident rotation on physician practices following residency: the mount sinai experience. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(2):480–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Esquibel BM, O'Heron CT, Arnold EJ, et al. International surgery electives during general surgery residency: a 9-year experience at an independent academic center. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(6):e234–e239. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scheiner A, Rickard JL, Nwomeh B, et al. Global surgery pro-con debate: a pathway to bilateral academic success or the bold new face of colonialism? J Surg Res. 2020;252:272–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2020.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.St-Amant O, Ward-Griffin C, Berman H, et al. Client or volunteer? Understanding neoliberalism and neocolonialism within international volunteer health work. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2018;5:2333393618792956. doi: 10.1177/2333393618792956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gumbs AA, Gumbs MA, Gleit Z, et al. How international electives could save general surgery. Am J Surg. 2012;203(4):551–552. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bozinoff N, Dorman KP, Kerr D, et al. Toward reciprocity: host supervisor perspectives on international medical electives. Med Educ. 2014;48(4):397–404. doi: 10.1111/medu.12386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kung TH, Richardson ET, Mabud TS, et al. Host community perspectives on trainees participating in short-term experiences in global health. Med Educ. 2016;50(11):1122–1130. doi: 10.1111/medu.13106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lukolyo H, Rees CA, Keating EM, et al. Perceptions and expectations of host country preceptors of short-term learners at four clinical sites in Sub-Saharan Africa. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(4):387–393. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.11.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loiseau B, Sibbald R, Raman SA, et al. Perceptions of the role of short-term volunteerism in international development: views from volunteers, local hosts, and community members. J Trop Med. 2016;2016:2569732. doi: 10.1155/2016/2569732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peluso MJ, Rodman A, Mata DA, et al. A comparison of the expectations and experiences of medical students from high-, middle-, and low-income countries participating in global health clinical electives. Teach Learn Med. 2018;30(1):45–56. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2017.1347510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.LaGrone LN, Isquith-Dicker LN, Egoavil EH, et al. Surgeons' and Trauma Care Physicians' perception of the impact of the globalization of medical education on quality of care in Lima. Peru JAMA Surg. 2017;152(3):251–256. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wassef DW, Holler JT, Pinner A, et al. Perceptions of orthopaedic volunteers and their local hosts in low- and middle-income countries: are we on the same page? J Orthop Trauma. 2018;32(Suppl 7):S29–S34. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mulenga M, Rhodes Z, Wren SM, Parikh PP. Local staff perceptions and expectations of international visitors in global surgery rotations. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(10):980. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donnelley CA, Won N, Roberts HJ, von Kaeppler EP, Albright PD, Woolley PM, Haonga B, Shearer DW, Sabharwal S. Resident rotations in low- and middle-income countries: motivations, impact, and host perspectives. JBJS Open Access. 2020;5(3):e20.00029–e20.00029. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.OA.20.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elobu AE, Kintu A, Galukande M, et al. (2014) Evaluating international global health collaborations: perspectives from surgery and anesthesia trainees in Uganda. Surgery. 2014;155(4):585–592. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cadotte DW, Sedney C, Djimbaye H, et al. (2014) A qualitative assessment of the benefits and challenges of international neurosurgical teaching collaboration in Ethiopia. World Neurosurg. 2014;82(6):980–986. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ibrahim GM, Cadotte DW, Bernstein M. A framework for the monitoring and evaluation of international surgical initiatives in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0120368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120368.PMID:25821970;PMCID:PMC4379101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Donnell S, Adler DH, Inboriboon PC, et al. Perspectives of South American physicians hosting foreign rotators in emergency medicine. Int J Emerg Med. 2014;7:24. doi: 10.1186/s12245-014-0024-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grant CL, Robinson T, Al Hinai A, et al. Ethical considerations in global surgery: a scoping review. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(4):e002319. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crump JA, Sugarman J. Ethical considerations for short-term experiences by trainees in global health. JAMA. 2008;300(12):1456–1458. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.12.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crump JA, Sugarman J. Working group on ethics guidelines for global health training (WEIGHT). Ethics and best practice guidelines for training experiences in global health. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83(6):1178–1182. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miranda JJ, Garcia PJ, Lescano AG, et al. Global health training–one way street? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;84(3):506–507. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0694a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Umoren RA, James JE, Litzelman DK. Evidence of reciprocity in reports on international partnerships. Educ Res Intern. 2012;2012:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2012/603270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Axt J, Nthumba PM, Mwanzia K, et al. Commentary: the role of global surgery electives during residency training: relevance, realities, and regulations. Surgery. 2013;153(3):327–332. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rohrbaugh R, Kellett A, Peluso MJ. Bidirectional exchanges of medical students between institutional partners in global health clinical education programs: putting ethical principles into practice. Ann Glob Health. 2016;82(5):659–664. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2016.04.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Redko C, Bessong P, Burt D, et al. Exploring the significance of bidirectional learning for global health education. Ann Glob Health. 2016;82(6):955–963. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rickard J, Ntirenganya F, Ntakiyiruta G, et al. Global health in the 21st century: equity in surgical training partnerships. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(1):9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hudspeth JC, Rabin TL, Dreifuss BA, et al. Reconfiguring a one-way street: a position paper on why and how to improve equity in global physician training. Acad Med. 2019;294(4):482–489. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hofstede G (1991). Part II National Cultures: more equal than others. Cultures and organizations: software of the mind. London: McGraw-Hill. 23-46

- 59.Purkey E, Hollaar G. Developing consensus for postgraduate global health electives: definitions, pre-departure training and post-return debriefing. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:159. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0675-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Foronda C, Baptiste DL, Reinholdt MM, et al. Cultural humility: a concept analysis. J Transcult Nurs. 2016;27(3):210–217. doi: 10.1177/1043659615592677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tervalon M, Murray-García J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9(2):117–125. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ganguli S, Yibrehu B, Niba V. Global surgery in the time of COVID-19: a trainee perspective. Am J Surg. 2020;220(6):1534–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McDonald S, Fabbri A, Parker L, et al. Medical donations are not always free: an assessment of compliance of medicine and medical device donations with World Health Organization guidelines (2009–2017) Int Health. 2019;11(5):379–402. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihz004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marks IH, Thomas H, Bakhet M, Fitzgerald E. Medical equipment donation in low-resource settings: a review of the literature and guidelines for surgery and anaesthesia in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(5):e001785. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Holst J. Global health – emergence, hegemonic trends and biomedical reductionism. Glob Health. 2020 doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00573-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bodnar BE, Claassen CW, Solomon J, et al. The effect of a bidirectional exchange on faculty and institutional development in a global health collaboration. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0119798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abedini NC, Danso-Bamfo S, Moyer CA, et al. Perceptions of Ghanaian medical students completing a clinical elective at the University of Michigan Medical School. Acad Med. 2014;89(7):1014–1017. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Umoren RA, Einterz RM, Litzelman DK, et al. (2014) Fostering reciprocity in global health partnerships through a structured, hands-on experience for visiting postgraduate medical trainees. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(2):320–325. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00247.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pitt MB, Gladding SP, Majinge CR, Butteris SM. Making global health rotations a two-way street: a model for hosting international residents. Glob Pediatr Health. 2016;3:2333794X1663067. doi: 10.1177/2333794X16630671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arora G, Russ C, Batra M, et al. Bidirectional exchange in global health: moving toward true global health partnership. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97(1):6–9. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Greive-Price T, Mistry H, Baird R. North–South surgical training partnerships: a systematic review. Can J Surg. 2020;63(6):E551–E561. doi: 10.1503/cjs.008219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baird R, Poenaru D, Ganey M, et al. Partnership in fellowship: comparative analysis of pediatric surgical training and evaluation of a fellow exchange between Canada and Kenya. J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51(10):1704–1710. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lakhoo K, Msuya D. Global health: a lasting partnership in paediatric surgery. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2015;12(2):114–118. doi: 10.4103/0189-6725.160351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guest GD, Scott DF, Xavier JP, et al. Surgical capacity building in Timor-Leste: a review of the first 15 years of the royal Australasian college of surgeons-led Australian aid programme. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87(6):436–440. doi: 10.1111/ans.13768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Debas H, Alatise OI, Balch CM, et al. Academic partnerships in global surgery: an overview american surgical association working group on academic global surgery. Ann Surg. 2020;271(3):460–469. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hagopian A, Thompson MJ, Fordyce M, et al. The migration of physicians from sub-Saharan Africa to the United States of America: measures of the African brain drain. Hum Resour Health. 2004;2(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-2-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]