Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the frequency and severity of new cases of youth-onset type 2 diabetes in the US during the first year of the pandemic compared with the mean of the previous 2 years.

Study design

Multicenter (n = 24 centers), hospital-based, retrospective chart review. Youth aged ≤21 years with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes between March 2018 and February 2021, body mass index ≥85th percentile, and negative pancreatic autoantibodies were included. Demographic and clinical data, including case numbers and frequency of metabolic decompensation, were compared between groups.

Results

A total of 3113 youth (mean [SD] 14.4 [2.4] years, 50.5% female, 40.4% Hispanic, 32.7% Black, 14.5% non-Hispanic White) were assessed. New cases of type 2 diabetes increased by 77.2% in the year during the pandemic (n = 1463) compared with the mean of the previous 2 years, 2019 (n = 886) and 2018 (n = 765). The likelihood of presenting with metabolic decompensation and severe diabetic ketoacidosis also increased significantly during the pandemic.

Conclusions

The burden of newly diagnosed youth-onset type 2 diabetes increased significantly during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, resulting in enormous strain on pediatric diabetes health care providers, patients, and families. Whether the increase was caused by coronavirus disease 2019 infection, or just associated with environmental changes and stressors during the pandemic is unclear. Further studies are needed to determine whether this rise is limited to the US and whether it will persist over time.

Abbreviations: BMI, Body mass index; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; DKA, Diabetic ketoacidosis; EMR, Electronic medical record; HbA1c, Hemoglobin A1c; HHS, Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome; PPY, Prepandemic year; TODAY, Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Youth

The incidence of youth-onset type 2 diabetes is rising worldwide. The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study showed an increase in incidence of 5% per year in the US from 2002 to 2012,1 such that prevalence nearly doubled between 2001 and 2017.2 This has significant long-term implications, given observations from the Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Youth (TODAY) study showing rapid β-cell failure3 and early onset of complications4 in least one-half of US youth with type 2 diabetes.

A recent study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention5 demonstrated an increased incidence of diabetes in youth following coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection but did not differentiate diabetes type. Moreover, irrespective of concomitant COVID-19 infection, since the onset of the pandemic, pediatric endocrinologists have anecdotally experienced an unprecedented acute burden of newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Multicenter and/or population-based studies in the US and Europe suggest that the proportion of youth with type 1 diabetes presenting in diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) rose early in the pandemic, but the impact on the overall incidence of type 1 diabetes is still unclear.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Several US individual institutions showed an increase in both rates and severity of presentation of youth-onset type 2 diabetes during the pandemic.11, 12, 13, 14, 15 However, multicenter/population-based data regarding effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on youth-onset type 2 diabetes have not yet been published.

This study was designed to compile retrospective data from electronic medical records (EMRs) from institutions across the US to assess the national impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on rates of youth-onset type 2 diabetes. Specifically, the aims were to compare the total number of new cases of youth-onset type 2 diabetes and the proportion of those youth presenting with metabolic decompensation (DKA and/or hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome [HHS]) from March 2020 to February 2021 to the previous 2 years.

Methods

This retrospective, multicenter study examined trends in youth-onset type 2 diabetes diagnosis and incidence of metabolic decompensation at presentation during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic (March 1, 2020, to February 28, 2021) compared with the previous 2 years (March 1, 2018, to February 29, 2020). This collaborative effort was organized by the Children's Hospital Colorado/University of Colorado School of Medicine and the Johns Hopkins Hospital/Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, with 24 contributing diabetes clinics in the US (Appendix). Institutional review board approval was obtained by each contributing site, with a waiver of consent. Deidentified data were submitted to the coordinating center.

Patients ≤21 years old diagnosed with type 2 diabetes from March 1, 2018, to March 1, 2021, were included. Diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, in accordance with American Diabetes Association guidelines, required ≥2 negative diabetes-associated antibodies (glutamic acid decarboxylase-65, insulin antibodies, zinc transporter 8, and/or islet antibodies [islet antigen-2 or islet cell antibodies]), and no positive antibodies.16 Medication-induced diabetes, prediabetes, post-transplant diabetes, and body mass index (BMI) <85 percentile were exclusionary. Patients were included if BMI ≥85 percentile was confirmed before onset of type 2 diabetes, but acute weight loss resulted in BMI <85 percentile at diagnosis. Inclusion criteria were designed to ensure participants had type 2 diabetes while being kept broad enough to ensure generalizability and reduce bias. Eligibility was adjudicated at each site based on these criteria. Of note, history of overweight/obesity was confirmed in 112 participants who do not have BMI at diagnosis due to missing height.

EMR-extracted data included diabetes-related clinical variables, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance type, age at diagnosis, BMI, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), and initial random blood sugar at diagnosis; for those with metabolic decompensation (DKA or HHS, or mixed DKA/HHS) at presentation, initial pH, bicarbonate, and serum osmolarity were recorded. At 23 of 24 institutions, race and ethnicity were determined by 2 separate questions; in addition to these self-report questions, the University of Columbia uses Spanish language to help determine Hispanic/LatinX ethnicity if a family reports “other or unknown.” Data extraction from EMR allowed for options of “other” and “unknown” for race, and thus some of these data are incomplete. Laboratory values reported as either above or below the limit of detection were set to the limit of detection. DKA was defined as either pH <7.3 or bicarbonate ≤1.5. DKA severity was categorized using the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes 2018 guidelines: mild DKA = pH 7.2-7.29 and/or bicarbonate 11-15 mmol/L, moderate DKA = pH 7.1-7.19 and/or bicarbonate 6-10 mmol/L, and severe DKA = pH<7.1 and/or bicarbonate ≤5 mmol/L.17 HHS was defined as serum osmolality ≥330 mOsm/kg and serum glucose >600 mg/dL. If data regarding pH or osmolality were missing, it was presumed that they did not present in DKA or HHS, respectively.

The primary outcome was the absolute case number of new-onset type 2 diabetes diagnosed in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, compared with the mean of the previous 2 years. The secondary outcome was the percentage of these patients presenting with metabolic decompensation (DKA, HHS, or mixed DKA/HHS) compared with the previous 2 years.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics reported include mean ± SD for normally distributed continuous variables, median (25th, 75th percentile) for skewed continuous variables, and frequency and percentage for categorical variables. Groups were compared using either a t-test or ANOVA for normally distributed continuous variables, the Kruskal–Wallis test for non-normally distributed variables, and the χ2 test for categorical variables.

A negative binomial time series model was used to model the count of youth-onset type 2 diabetes diagnoses per month. A background linear trend of 5% increase per year was assumed. Seasonality was assessed by allowing the number of diagnoses in a particular month to depend on the number in the previous month, and the number 12 months previously. A test of intervention was performed to determine whether the onset of the pandemic in March 1, 2020, had a significant effect on the count of diagnoses.18 , 19

The year from March 1, 2018, to February 28, 2019, is referred to as prepandemic year 18-19 (PPY18-19), from March 1, 2019, to February 29, 2020, as prepandemic year 19-20 (PPY19-20), and from March 1, 2020, to February 28, 2021, as the pandemic year.

Results

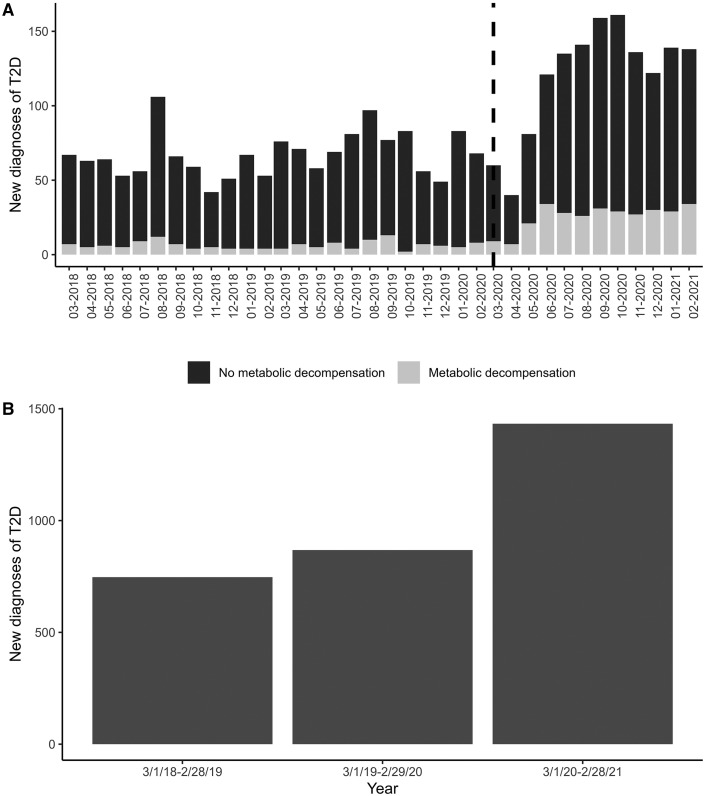

A total of 3459 patients with new-onset type 2 diabetes were identified from 24 centers across the US. Of these, 312 were excluded due to inadequate antibody data, 32 were excluded due to BMI <85 percentile, 1 was excluded due to suspicion for monogenic diabetes, and 1 was excluded due to young age, atypical of type 2 diabetes. Thus, the final analysis included 3113 participants (Table I ). The average number of new diagnoses per year in the 2 prepandemic years was 825, compared with 1463 diagnosed during the first pandemic year, an increase of 77.3% (Figure 1 ). The increase in new presentation was seen across almost all sites (Table II; available at www.jpeds.com). The largest contributing site reported 426 new cases (13.7% of the total sample). The South and West regions were over-represented, particularly compared with the Northeast (Table I, P = .11). The mean age at presentation did not change over the 3-year period.

Table I.

Demographic, anthropometric, and clinical characteristics of study participants

| Characteristics | PPY 18-19 | PPY 19-20 | Pandemic | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total new-onset type 2 diabetes, No. | 765 | 886 | 1463 | .005 |

| Region, No. (%) | ||||

| Midwest | 201 (26.3) | 214 (24.2) | 342 (23.4) | .114 |

| Northeast | 64 (8.4) | 93 (10.5) | 168 (11.5) | |

| South | 265 (34.7) | 277 (31.3) | 458 (31.3) | |

| West | 234 (30.6) | 302 (34.1) | 495 (33.8) | |

| Age at diagnosis, y, mean (SD) n = 22 missing | 14.3 (2.3) | 14.5 (2.4) | 14.4 (2.3) | .226 |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||

| Asian | 20 (2.6) | 24 (2.7) | 40 (2.7) | .004 |

| Black | 231 (30.2) | 267 (30.1) | 519 (35.5) | |

| Hispanic | 323 (42.3) | 356 (40.2) | 577 (39.4) | |

| White | 121 (15.8) | 143 (16.1) | 187 (12.8) | |

| Other | 49 (6.4) | 45 (5.1) | 88 (6.0) | |

| Unknown | 20 (2.6) | 51 (5.8) | 52 (3.6) | |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||||

| Female | 421 (55.1) | 488 (55.1) | 663 (45.3) | <.001 |

| Male | 343 (44.9) | 398 (44.9) | 800 (54.7) | |

| Insurance, No. (%) | ||||

| Private | 182 (23.8) | 207 (23.4) | 305 (20.8) | .009 |

| Public | 556 (72.8) | 647 (73.0) | 1110 (75.9) | |

| Other | 4 (0.5) | 9 (1.0) | 5 (0.3) | |

| Uninsured | 20 (2.6) | 22 (2.5) | 27 (1.8) | |

| Unknown | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 16 (1.1) | |

| Location at diagnosis, No. (%) | ||||

| Inpatient | 329 (43.1) | 382 (43.1) | 836 (57.1) | <.001 |

| Outpatient | 434 (56.8) | 502 (56.7) | 626 (42.8) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | |

| COVID-19 at diagnosis, No. (%), n = 266 missing | ||||

| No | 529 (82.4) | 625 (82.3) | 954 (66.0) | <.001 |

| Unknown | 113 (17.6) | 133 (17.5) | 456 (31.5) | |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 36 (2.5) | |

| BMI, kg/m2, median [IQR] n = 112 missing | 34.6 [29.6, 39.2] | 34.3 [30.0, 39.3] | 35.1 [30.9, 40.9] | .001 |

| BMI % of 95%ile, mean [SD] | 133.88 (31.11) | 132.41 (30.17) | 137.04 (30.09) | .001 |

| HbA1c, %, median [IQR] n = 14 missing | 9.3 [7.3, 11.9] | 9.7 [7.1, 12.1] | 10.4 [7.9, 12.4] | <.001 |

| Serum glucose (random), mg/dL, (median [IQR]) | 241 [142, 360] | 246 [146, 361] | 286 [171, 414] | <.001 |

| pH, median [IQR],∗ n = 1837 missing | 7.37 [7.30, 7.40] n = 261 | 7.36 [7.31, 7.39] n = 320 | 7.34 [7.21, 7.39] n = 695 | <.001 |

| Bicarbonate, mmol/L, median [IQR]∗ n = 1530 missing | 23.0 [20.0, 26.0] n = 355 | 24.0 [19.0, 26.0] n = 401 | 21.0 [12.0, 25.0] n = 827 | <.001 |

| Serum osmolality, mOsm/kg, median [IQR]∗ n = 2657 missing | 298.0 [292.0, 307.0] n = 122 | 297.0 [293.0, 304.5] n = 87 | 306.0 [293.0, 333.5] n = 247 | .002 |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis, No. (%) | 70 (9.2) | 79 (8.9) | 304 (20.8) | <.001 |

| Hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome, No. (%) | 7 (0.9) | 6 (0.7) | 56 (3.8) | <.001 |

| Metabolic decompensation, No. (%) | 72 (9.4) | 80 (9.0) | 307 (21.0) | <.001 |

| DKA severity (%) | ||||

| Mild | 25 (35.7) | 33 (41.8) | 121 (39.8) | .35 |

| Moderate | 30 (42.9) | 25 (31.6) | 93 (30.6) | |

| Severe | 15 (21.4) | 21 (26.6) | 90 (29.6) |

SI conversion factors: To convert HbA1c to mmol/mol, multiply by 0.01, to convert serum osmolality to mmol/kg, multiply by 1.

Data only included for subset of patients with data available.

Figure 1.

New youth-onset type 2 diabetes diagnosis by month and year. A, Number of new type 2 diabetes cases by month, including the proportion presenting with metabolic decompensation. The dotted vertical line demarcated onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. B, Total number of new diagnoses by year. T2D, type 2 diabetes.

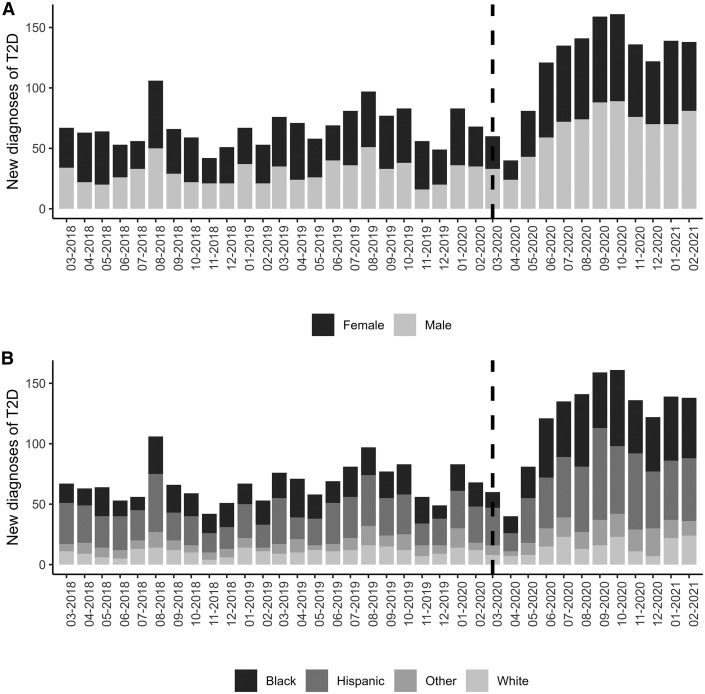

Because of an apparent peak of diagnoses in August, a covariate corresponding to August vs other months was tested but was not significant. Thus, the final model did not include any effect of seasonality. There was a difference in racial/ethnic distribution over the 3 years, P = .004 (Table I, Figure 2 ), with post-hoc analyses demonstrating increased diagnoses among Black youth (P = .002) and decreased diagnoses among White youth (P = .039) during the pandemic year. The vast majority of new type 2 diabetes diagnoses occurred in those with public insurance during all 3 years. There was a reversal in the proportion of male vs female new diagnoses—55% female/45% male in PPY18-19 and PPY19-20 compared with 45% female/55% male during the pandemic year (P < .001, Figure 2). There was no difference in association of sex by race/ethnicity pre- and postpandemic.

Figure 2.

New youth-onset type 2 diabetes diagnosis by sex and race/ethnicity. A, Number of new cases each month broken down by sex, with the dotted line representing onset of the pandemic. This depicts the rise in proportion of male cases during the pandemic. B, Number of new cases each month broken down by race and ethnicity, with the dotted line representing onset of the pandemic. This depicts the relative rise in type 2 diabetes diagnoses in Black youth during the pandemic.

BMI was statistically greater on presentation in the pandemic year compared with PPY1 and PPY2. Patients with new-onset type 2 diabetes presented with greater HbA1c (median 10.4% vs 9.3% [PPY1] and 9.7% [PPY2], P < .001) and greater blood glucose during the pandemic compared with the 2 previous years (median 286 mg/dL vs 240 mg/dL [PPY18-19] and 246 mg/dL [PPY19-20], P < .001). In the prepandemic years, more patients with new-onset type 2 diabetes were diagnosed as outpatients; there was a reversal during the pandemic year such that more patients were diagnosed and managed as inpatients (43% inpatient vs 57% outpatient during PPY18-19 and PPY19-20, as opposed to 57% inpatient and 43% outpatient during the pandemic). Further, 21% of youth presented with metabolic decompensation (DKA and/or HHS) at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes during the first year of the pandemic compared with 9.4% and 9.0% in PPY1 and PPY2, respectively (P < .001) (Table I, Figure 1). Few patients in this cohort had a concurrent COVID-19 infection detected at presentation of type 2 diabetes (Table I).

A negative binomial time series model showed that pandemic onset (March 1, 2020) had a significant effect on the number of type 2 diabetes diagnoses, with a parameter estimate of 15.2, P < .0001. This estimate represents an increase of 15.2 type 2 diabetes cases per month, although the effect is not strictly additive because the background linear trend of 5% increase per year is applied to the increased number of cases per month. Another negative binomial time series model demonstrated a significant effect of the pandemic on the number of patients presenting with metabolic decompensation, with a parameter estimate of 7.0, P = .002.

Discussion

This first multicenter report from 24 US diabetes centers, including more than 3100 youth diagnosed with new-onset type 2 diabetes over 3 years, shows an unprecedented impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the frequency of diagnosis of youth-onset type 2 diabetes, increasing by 77.3% compared with the average in the 2 previous years. Moreover, severity of initial presentation rose, based on proportion presenting with metabolic decompensation, which more than doubled, and median HbA1c at diagnosis. This confirms the findings of 3 single-center studies, all of which contributed data to this analysis, suggesting that rates of type 2 diabetes and presentation in DKA rose during the COVID-19 pandemic.11 , 14 , 15

Although the incidence of type 2 diabetes was already on the rise, the increase seen in the past year significantly outpaces recently published epidemiologic data, which demonstrated an annual increase in incidence of approximately 5% between 2002 and 2012.1 Interestingly, the rise in youth-onset type 2 diabetes between PPY18-19 and PPY19-20, at 15.8%, was also greater than previously reported. However, data presented here are derived from subspecialty diabetes care centers, and are not population-based data, so trends seen in this study may not be generalizable. Historically, type 2 diabetes has been described as almost twice as common among female youth in the US,1 , 20 but during the pandemic this trend changed, with an increase in the relative proportion of adolescent male youth diagnosed. There was also an increase in proportion of cases diagnosed in Black youth and a decrease in White youth during the pandemic. The sex differences seen do not appear to be driven by racial or ethnic differences. However, the increase in proportion of Black youth diagnosed with type 2 diabetes is consistent with recent US population data.2

Potential explanations for the pandemic-associated rise in youth-onset type 2 diabetes are broad and likely multifactorial. Pediatric weight gain tends to increase during summer months, when school is out.21 , 22 Indeed, there are regional23 , 24 and national25 , 26 database reports of a rising trajectory of BMI during the pandemic, when most youth were out of school, and BMI increases were greatest in youth with previous overweight or obesity. However, the rise in BMI appears to have had the most significantly affected younger children (5-11 years),25 whereas the onset of type 2 diabetes seldom occurs before puberty. We noted an increase in BMI of youth at diabetes diagnosis in the pandemic year compared with the previous 2 years. The reasons for pandemic gains in BMI have yet to be elucidated but presumably are in part related to increases in sedentary behavior and changes in eating behaviors. During the pandemic, families reported changes in the home food environment, purchasing more shelf-stable foods that are ultra-processed and calorie-dense, which could contribute to weight gain.27 Sedentary behavior changes included increased screen time related to online school, lack of physical education, cancellation of organized sports and other activities, and people being more confined to their homes.28 One group specifically reported an increase in screen time during the pandemic in youth with previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes.29 However, most of available data regarding pandemic-related behavior changes are based on self-report, relying on recall for report of prepandemic behaviors; thus, these are likely to be inaccurate.28, 29, 30 Accelerometry-based data from TODAY and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey suggested that greater sedentary behavior distinguishes youth with type 2 diabetes from youth with obesity but without diabetes.31 Furthermore, boys are known to be more physically active than girls during adolescence32 , 33; thus, they may have been affected in terms of BMI gains and metabolic risk by increases in sedentary behavior than girls. This may, in part explain, the reversal in sex differences in incident type 2 diabetes in youth during the pandemic. Although there is some evidence that boys experienced greater weight gain during the pandemic,34 the largest studies did not break results down by sex,24 , 25 , 35 so it is unclear whether boys had more significant weight gain than girls. However, data from the TODAY study support the hypothesis that lifestyle change may more significantly affect type 2 diabetes in adolescent boys, as male subjects in TODAY responded more favorably to lifestyle intervention than female subjects.3 Although this evidence is certainly not adequate to prove that lifestyle behavior changes are the sole cause of rising cases of youth-onset type 2 diabetes during the pandemic, they certainly may contribute to its onset in those at increased risk.

Another potential contributor to the pandemic-related increase in type 2 diabetes presentation is an increase in psychosocial stress.36 Youth with type 2 diabetes are known to be exposed to significant environmental stressors, as evidenced by a high proportion coming from single-caregiver and low-income households, with low parental education attainment.20 Furthermore, mental health disorders are common in youth with obesity and diabetes.37 , 38 It is possible that elements of this underlying stress could contribute to the pathophysiology of diabetes. Shomaker et al demonstrated that treatment of depression with cognitive behavioral therapy in girls at risk for type 2 diabetes improved insulin sensitivity compared with health education-controls 1 year after the treatment, and independent of BMI change.39 Furthermore, in SEARCH, depression was associated with greater metabolic and inflammatory markers.40 The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a significant mental health crisis in youth, with rates of depression and anxiety among youth that have doubled compared with prepandemic years.41 In addition, screens assessing suicide risk have shown increasing rates of positivity during the COVID-19 pandemic in both the pediatric emergency department42 and primary care setting.43 In addition to potentially affecting stress physiology, social determinants of health also impact access to healthy food, access to health care, and safe outdoor environments. The pandemic may have disproportionately affected Black youth, who already are at greater risk for health disparities.44 This may in part explain the racial differences in newly diagnosed diabetes associated with the pandemic. Whether there is a direct or indirect relationship between psychosocial stress and incident youth-onset type 2 diabetes, this coincident increase during the pandemic warrants further investigation.

Finally, there is a possibility that COVID-19 infection itself may have caused a nonautoimmune destruction of β cells, resulting in declines in β-cell function in adolescents already predisposed to develop diabetes. There is in vitro evidence that the β-cell expresses the angiotensin converting enzyme-2 receptor—the receptor that the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 virus binds to gain entry into the cell and, further, that COVID-19 infection in the β-cell can result in decreased insulin secretion.45 , 46 Some have argued that this might explain high rates of DKA in adults with COVID-19 infection and coincident diabetes. However, the evidence is conflicting and purely in vitro in nature.47 A recent publication from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention using retrospective claims data in thousands of youth found a significant increase in diabetes incidence at least 30 days after COVID-19 infection, both compared with a control population without COVID-19 infection and compared with a pre-pandemic control group with non–COVID-19 respiratory infection.5 However, the study did not differentiate diabetes type. COVID-19 infection has been associated with an increase in type 2 diabetes onset among adults.48 , 49 Currently, an international group has designed a registry (CoviDIAB) to better evaluate the clinical impact of COVID-19 on incident type 2 diabetes.49 In those hospitalized from our cohort, very few had coincident COVID-19 infection. Because symptomatic COVID-19 infections are low in youth, and antibody testing was very limited at our sites, our study lacks evidence for whether these youth with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes had a previous COVID-19 infection.

Our results also demonstrated increased severity of presentation of youth-onset type 2 diabetes during the pandemic, with increased HbA1c on presentation and increased presentation with metabolic decompensation. Although criteria for inpatient admission of youth with new-onset type 2 diabetes varies by institution, and these criteria may have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, inpatient admission generally suggests a more severe presentation at diagnosis. A pandemic-associated increase in severity of presentation also has been reported in youth with type 1 diabetes.7 , 8 , 14 , 49 It is also likely that patients and families may have delayed seeking care due to concerns about being exposed to COVID-19; delayed presentation with other diseases has been reported in the literature.50 , 51 Whereas the literature on adult reports increased DKA rates in those with a previous diabetes diagnosis associated with concurrent COVID-19 infection, as well as hyperglycemia associated with COVID-19 infection in patients without diabetes, detected rates of COVID-19 positivity were low in our patients presenting with metabolic decompensation.

This study has the known limitations of retrospective chart review data, which include inconsistency of reported data and missing information. In addition, incidence data cannot be derived due to lack of an appropriate denominator. Thus, the findings need to be validated in population-based cohorts. One of the strengths is the use of a rigorous type 2 diabetes definition, requiring at least 2 pancreatic autoantibodies tested and negative, without positive detected antibodies. This, combined with the pediatric endocrinology provider-based diagnosis, ensures that patients with type 2 diabetes were captured in this analysis. Another strength is the racial/ethnic and geographic heterogeneity of the study population, which is possible only with multicenter data from centers throughout the US. In addition, the findings confirm what single sites have previously reported.

The results of this study of more than 3100 patients with newly diagnosed diabetes demonstrate a dramatic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the presentation of type 2 diabetes in youth, which was already rising in incidence and prevalence before the pandemic. This has created a significant strain on pediatric endocrinology, general practitioner, and obesity providers, who have been managing this growing population with limited resources. Moreover, marginalized and under-resourced families already impacted by high rates of unemployment, food and housing insecurity during the pandemic, have been disproportionately affected. The long-term implications of this rapid rise in youth-onset type 2 diabetes case numbers are important in the context of the final outcome analysis of the TODAY study, which demonstrated an alarming incidence of complications—60% of youth experienced at least 1 complication after a mean follow-up of 13.3 years.4 It is important to note that the TODAY study participants were treated and followed rigorously as part of a clinical trial and, thus, results may underestimate the burden of complications in youth-onset type 2 diabetes. Follow-up studies will need to assess durability of the trend of increasing type 2 diabetes case numbers and severity, and to further explore potential underlying causes and outcomes.

Footnotes

Funding and disclosure information is available at www.jpeds.com.

Supplementary Data

Appendix

Table II.

Number of new cases by year at each site (%of total for that year)

| Institutions | March 1, 2018, to February 28, 2019 N = 764 | March 1, 2019, to February 28, 2020 N = 886 | March 1, 2020, to February 28, 2021 N = 1463 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children’s Hospital Colorado | 59 (7.7) | 61 (6.9) | 95 (6.5) |

| Children’s Hospital Illinois | 2 (0.3) | 4 (0.5) | 4 (0.3) |

| Children’s Hospital Los Angeles | 86 (11.3) | 130 (14.7) | 210 (14.4) |

| Children’s Hospital Philadelphia | 21 (2.7) | 42 (4.7) | 72 (4.9) |

| Children’s Mercy | 35 (4.6) | 59 (6.7) | 69 (4.7) |

| Children’s National Hospital | 39 (5.1) | 30 (3.4) | 86 (5.9) |

| Cincinnati Children’s Hospital | 38 (5.0) | 41 (4.6) | 45 (3.1) |

| Columbia University Irving Medical Center, Harlem Hospital | 8 (1.0) | 13 (1.5) | 27 (1.8) |

| Duke University Medical Center | 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.3) | 20 (1.4) |

| Hasbro Children’s Hospital | 18 (2.4) | 19 (2.1) | 37 (2.5) |

| John Hopkins Hospital | 25 (3.3) | 24 (2.7) | 57 (3.9) |

| Lurie Children’s Hospital | 52 (6.8) | 33 (3.7) | 101 (6.9) |

| Mayo Clinic | 5 (0.7) | 5 (0.6) | 9 (0.6) |

| Our Lady of The Lake Children’s Hospital | 17 (2.2) | 20 (2.3) | 23 (1.6) |

| Penn State Health Children’s Hospital | 17 (2.2) | 19 (2.1) | 32 (2.2) |

| Rady Children’s Hospital | 43 (5.6) | 47 (5.3) | 98 (6.7) |

| Riley Children’s Hospital | 35 (4.6) | 42 (4.7) | 62 (4.2) |

| Texas Children’s Hospital | 31 (4.1) | 32 (3.6) | 43 (2.9) |

| University of California San Francisco | 46 (6.0) | 64 (7.2) | 92 (6.3) |

| University of Chicago Medical Center | 20 (2.6) | 20 (2.3) | 41 (2.8) |

| University of Michigan | 14 (1.8) | 10 (1.1) | 11 (0.8) |

| University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center | 42 (5.5) | 55 (6.2) | 67 (4.6) |

| University of Texas Southwestern | 91 (11.9) | 95 (10.7) | 132 (9.0) |

| Vanderbilt University Medical Center | 17 (2.2) | 18 (2.0) | 30 (2.1) |

Funding and Conflicts of Interest Disclosure

L.H. is a site investigator for a type 2 diabetes treatment trial sponsored by Boehringer-Ingelheim; M.K. is a site investigator for type 2 diabetes treatment trials sponsored by Boehringer-Ingelheim and Janssen; B.M. has received investigator-initiated funding from Tandem Diabetes Care and Dexcom; A.S. is the site PI for trials sponsored by AstraZeneca, NovoNordisk, and Boehringer-Ingelheim; and R.W. has received investigator-initiated funding from Dexcom; the other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mayer-Davis E.J., Lawrence J.M., Dabelea D., Divers J., Isom S., Dolan L., et al. Incidence Trends of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among youths, 2002-2012. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1419–1429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence J.M., Divers J., Isom S., Saydah S., Imperatore G., Pihoker C., et al. Trends in prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents in the US, 2001-2017. JAMA. 2021;326:717–727. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.11165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeitler P., Hirst K., Pyle L., Linder B., Copeland K., Arslanian S., et al. A clinical trial to maintain glycemic control in youth with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2247–2256. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Group T.S., Bjornstad P., Drews K.L., Caprio S., Gubitosi-Klug R., Nathan D.M., et al. Long-term complications in youth-onset type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:416–426. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2100165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrett C.E., Koyama A.K., Alvarez P., Chow W., Lundeen E.A., Perrine C.G., et al. Risk for Newly diagnosed diabetes >30 days after sARS-CoV-2 infection among persons aged <18 years—United States, March 1, 2020-June 28, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:59–65. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7102e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beliard K., Ebekozien O., Demeterco-Berggren C., Alonso G.T., Gallagher M.P., Clements M., et al. Increased DKA at presentation among newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes patients with or without COVID-19: data from a multi-site surveillance registry. J Diabetes. 2021;13:270–272. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.13141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamrath C., Mönkemöller K., Biester T., Rohrer T.R., Warncke K., Hammersen J., et al. Ketoacidosis in children and adolescents with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. JAMA. 2020;324:801–804. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.13445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabbone I., Schiaffini R., Cherubini V., Maffeis C., Scaramuzza A. Has COVID-19 delayed the diagnosis and worsened the presentation of type 1 diabetes in children? Diabetes Care. 2020;43:2870–2872. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tittel S.R., Rosenbauer J., Kamrath C., Ziegler J., Reschke F., Hammersen J., et al. Did the COVID-19 lockdown affect the incidence of pediatric type 1 diabetes in Germany? Diabetes Care. 2020;43:e172–e173. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unsworth R., Wallace S., Oliver N.S., Yeung S., Kshirsagar A., Naidu H., et al. New-onset type 1 diabetes in children during COVID-19: multicenter regional findings in the U.K. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:e170–e171. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chao L.C., Vidmar A.P., Georgia S. Spike in diabetic ketoacidosis rates in pediatric type 2 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:1451–1453. doi: 10.2337/dc20-2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Modarelli R., Sarah S., Ramaker M.E., Bolobiongo M., Benjamin R., Gumus Balikcioglu P. Pediatric diabetes on the rise: trends in incident diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Endocr Soc. 2022;6:bvac024. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvac024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmitt J.A., Ashraf A.P., Becker D.J., Sen B. Changes in type 2 diabetes trends in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107:e2777–e2782. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgac209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marks B.E., Khilnani A., Meyers A., Flokas M.E., Gai J., Monaghan M., et al. Increase in the diagnosis and severity of presentation of pediatric type 1 and type 2 diabetes During the COVID-19 pandemic. Horm Res Paediatr. 2021;94:275–284. doi: 10.1159/000519797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neyman A., Nabhan Z., Woerner S., Hannon T. Pediatric Type 2 diabetes presentation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2021 doi: 10.1177/00099228211064030. 99228211064030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Diabetes Association 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:S15–S33. doi: 10.2337/dc21-S002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolfsdorf J.I., Glaser N., Agus M., Fritsch M., Hanas R., Rewers A., et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018: diabetic ketoacidosis and the hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19(suppl 27):155–177. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fokianos K., Fried R. Interventions in INGARCH processes. J Time Series Analysis. 2010;31:210–225. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fokianos K., Fried R. Interventions in log-linear Poisson autoregression. Stat Modelling. 2012;12:299–322. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Copeland K.C., Zeitler P., Geffner M., Guandalini C., Higgins J., Hirst K., et al. Characteristics of adolescents and youth with recent-onset type 2 diabetes: the TODAY cohort at baseline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:159–167. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franckle R., Adler R., Davison K. Accelerated weight gain among children during summer versus school year and related racial/ethnic disparities: a systematic review. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E101. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreno J.P., Johnston C.A., Woehler D. Changes in weight over the school year and summer vacation: results of a 5-year longitudinal study. J Sch Health. 2013;83:473–477. doi: 10.1111/josh.12054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jenssen B.P., Kelly M.K., Powell M., Bouchelle Z., Mayne S.L., Fiks A.G. COVID-19 and Changes in Child Obesity. Pediatrics. 2021;147 doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-050123. e2021050123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woolford S.J., Sidell M., Li X., Else V., Young D.R., Resnicow K., et al. Changes in body mass index among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2021;326:1434–1436. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.15036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lange S.J., Kompaniyets L., Freedman D.S., Kraus E.M., Porter R., Blanck H.M., et al. Longitudinal trends in body mass index before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among persons aged 2–19 years—United States, 2018–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1278–1283. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7037a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weaver R.G., Hunt E.T., Armstrong B., Beets M.W., Brazendale K., Turner-McGrievy G., et al. COVID-19 leads to accelerated increases in children's BMI z-score gain: an interrupted time-series study. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61:e161–e169. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adams E.L., Caccavale L.J., Smith D., Bean M.K. Food insecurity, the home food environment, and parent feeding practices in the era of COVID-19. Obesity. 2020;28:2056–2063. doi: 10.1002/oby.22996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pietrobelli A., Pecoraro L., Ferruzzi A., Heo M., Faith M., Zoller T., et al. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on lifestyle behaviors in children with obesity living in Verona, Italy: a longitudinal study. Obesity. 2020;28:1382–1385. doi: 10.1002/oby.22861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng H.P., Wong J.S.L., Selveindran N.M., Hong J.Y.H. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on glycaemic control and lifestyle changes in children and adolescents with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocrine. 2021;73:499–506. doi: 10.1007/s12020-021-02810-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunton G.F., Do B., Wang S.D. Early effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity and sedentary behavior in children living in the U.S. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1351. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09429-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kriska A., Delahanty L., Edelstein S., Amodei N., Chadwick J., Copeland K., et al. Sedentary behavior and physical activity in youth with recent onset of type 2 diabetes. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e850–e856. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Basterfield L., Adamson A.J., Frary J.K., Parkinson K.N., Pearce M.S., Reilly J.J. Longitudinal study of physical activity and sedentary behavior in children. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e24–e30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nader P.R., Bradley R.H., Houts R.M., McRitchie S.L., O'Brien M. Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity from ages 9 to 15 years. JAMA. 2008;300:295–305. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maltoni G., Zioutas M., Deiana G., Biserni G.B., Pession A., Zucchini S. Gender differences in weight gain during lockdown due to COVID-19 pandemic in adolescents with obesity. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2021;31:2181–2185. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2021.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brooks C.G., Spencer J.R., Sprafka J.M., Roehl K.A., Ma J., Londhe A.A., et al. Pediatric BMI changes during COVID-19 pandemic: an electronic health record-based retrospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38:101026. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patrick S.W., Henkhaus L.E., Zickafoose J.S., Lovell K., Halvorson A., Loch S., et al. Well-being of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey. Pediatrics. 2020;146 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-016824. e2020016824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gulley L.D., Shomaker L.B. Depression in youth-onset type 2 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2020;20:51. doi: 10.1007/s11892-020-01334-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rankin J., Matthews L., Cobley S., Han A., Sanders R., Wiltshire H.D., et al. Psychological consequences of childhood obesity: psychiatric comorbidity and prevention. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2016;7:125–146. doi: 10.2147/AHMT.S101631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shomaker L.B., Tanofsky-Kraff M., Stern E.A., Miller R., Zocca J.M., Field S.E., et al. Longitudinal study of depressive symptoms and progression of insulin resistance in youth at risk for adult obesity. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2458–2463. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hood K.K., Lawrence J.M., Anderson A., Bell R., Dabelea D., Daniels S., et al. Metabolic and inflammatory links to depression in youth with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:2443–2446. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Racine N., McArthur B.A., Cooke J.E., Eirich R., Zhu J., Madigan S. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:1142–1150. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hill R.M., Rufino K., Kurian S., Saxena J., Saxena K., Williams L. Suicide ideation and attempts in a pediatric emergency department before and during COVID-19. Pediatrics. 2021;147 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-029280. e2020029280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mayne S.L., Hannan C., Davis M., Young J.F., Kelly M.K., Powell M., et al. COVID-19 and adolescent depression and suicide risk screening outcomes. Pediatrics. 2021;148 doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-051507. e2021051507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hill-Briggs F., Adler N.E., Berkowitz S.A., Chin M.H., Gary-Webb T.L., Navas-Acien A., et al. Social determinants of health and diabetes: a scientific review. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:258–279. doi: 10.2337/dci20-0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang X., Uhl S., Zhang T., Xue D., Li B., Vandana J.J., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection induces beta cell transdifferentiation. Cell Metab. 2021;33:1577–1591.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu C.-T., Lidsky P.V., Xiao Y., Lee I.T., Cheng R., Nakayama T., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infects human pancreatic β cells and elicits β cell impairment. Cell Metab. 2021;33:1565–1576.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Accili D. Can COVID-19 cause diabetes? Nat Metab. 2021;3:123–125. doi: 10.1038/s42255-020-00339-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al-Aly Z., Xie Y., Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;594:259–264. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03553-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rubino F., Amiel S.A., Zimmet P., Alberti G., Bornstein S., Eckel R.H., et al. New-onset diabetes in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:789–790. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2018688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lazzerini M., Barbi E., Apicella A., Marchetti F., Cardinale F., Trobia G. Delayed access or provision of care in Italy resulting from fear of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4:e10–e11. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30108-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosenberg Danziger C., Krause I., Scheuerman O., Luder A., Yulevich A., Dalal I., et al. Pediatrician, watch out for corona-phobia. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180:201–206. doi: 10.1007/s00431-020-03736-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.