Abstract

Background

Reports on the impact of some antiretrovirals against SARS-CoV-2 infection and disease severity are conflicting.

Objectives

We evaluated the effect of tenofovir as either tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (TAF/FTC) or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) against SARS-CoV-2 infection and associated clinical outcomes among people living with HIV (PLWH).

Methods

We conducted a propensity score-matched analysis in the prospective PISCIS cohort of PLWH (n = 14 978) in Catalonia, Spain. We used adjusted Cox regression models to assess the association between tenofovir and SARS-CoV-2 outcomes.

Results

After propensity score-matching, SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis rates were similar in TAF/FTC versus ABC/3TC recipients (11.6% versus 12.5%, P = 0.256); lower among TDF/FTC versus ABC/3TC recipients (9.6% versus 12.8%, P = 0.021); and lower among TDF/FTC versus TAF/FTC recipients (9.6% versus 12.1%, P = 0.012). In well-adjusted logistic regression models, TAF/FTC was no longer associated with reduced SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 0.90; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.78–1.04] or hospitalization (aOR 0.93; 95% CI, 0.60–1.43). When compared with ABC/3TC, TDF/FTC was not associated with reduced SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis (aOR 0.79; 95% CI, 0.60–1.04) or hospitalization (aOR 0.51; 95% CI, 0.15–1.70). TDF/FTC was not associated with reduced SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis (aOR 0.79; 95% CI, 0.60–1.04) or associated hospitalization (aOR 0.33; 95% CI, 0.10–1.07) compared with TAF/FTC.

Conclusions

TAF/FTC or TDF/FTC were not associated with reduced SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis rates or associated hospitalizations among PLWH. TDF/FTC users had baseline characteristics intrinsically associated with more benign SARS-CoV-2 infection outcomes. Tenofovir exposure should not modify any preventive or therapeutic SARS-CoV-2 infection management.

Introduction

Tenofovir has been postulated as a treatment candidate for COVID-19.1 This nucleotide analogue is very prominent in antiretroviral treatment (ART) and is available as the prodrugs tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF). The two medicines are also efficacious as HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in high-risk populations without HIV infection.2 The repurposing of TAF and TDF is due to their well-established safety profile, the wide availability of the generic forms, and the low cost of TDF.3 In pre-clinical studies, tenofovir showed some in vitro activity against SARS-CoV-2, inhibiting its RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp).4 Furthermore, triphosphate forms of tenofovir are believed to be incorporated by SARS-CoV-2 RdRp and retard polymerase extension, which could explain why the nucleotide analogue could inhibit SARS-CoV-2.5 However, a recent comprehensive set of in vitro analyses performed by the drug manufacturer has finally indicated that neither TAF, TDF, nor emtricitabine (FTC) are inactive against SARS-CoV-2.6 These results are corroborated by the lack of interaction between tenofovir triphosphates and SARS-CoV-2 RdRp observed both in biochemical assays and in structural modelling analyses.6

A study of people living with HIV (PLWH) receiving ART in Spain suggested that individuals receiving TDF/FTC were at a lower risk of COVID-19 and related hospitalization than those receiving other antiretroviral regimens.7 However, the analysis was not adjusted for baseline co-morbidities and important sociodemographic characteristics, and could be overestimating the protective effect of TDF/FTC because recipients of TDF/FTC are likely to be younger and without comorbidities such as renal and cardiovascular diseases, which have been established as risk factors for COVID-19 and severe outcomes.8–10 In another study, from South Africa, TDF/FTC (versus abacavir or zidovudine) was again associated with lower mortality among PLWH after adjusting for kidney disease, viral suppression, and antiretroviral treatment duration.11 Zidovudine, a second-line regimen, is however associated with prior virological failure or presence of tuberculosis, both of which were not adjusted for in that study. Similarly, among HIV-negative individuals with chronic hepatitis B infection, lower rates of severe COVID-19, ICU admission, need for respiratory support, and shorter hospitalization duration were found among patients receiving TDF/FTC compared with entecavir.12 However, again, the prevalence of chronic comorbidities was significantly lower among those receiving TDF/FTC, establishing again a channelling prescription bias.12

A study that assessed the protective effects of tenofovir against SARS-CoV-2 infection among HIV-negative individuals found just the opposite: a higher SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence among PrEP (tenofovir) users compared with persons not receiving tenofovir (15.5% versus 9.2%, P = 0.026).13 The study found no statistically significant differences in COVID-19 clinical manifestations between users of PrEP, TDF/FTC or TAF/FTC and the control group.13 Similarly, the PREVENIR-ANRS and SAPRIS-Sero study from France also showed no reduction in SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence among TDF/FTC PrEP users.14 That study is particularly relevant as there were no baseline patient characteristics biasing the analysis through a channelling prescription.

There are several on-going clinical trials assessing the potential of tenofovir as prophylaxis against SARS-CoV-2 infection and treatment for COVID-19.3 Understanding the preventive effect of tenofovir is very relevant given the rapidly changing COVID-19 situation and the surge of new variants with potential to escape vaccine- or infection-induced immune protection.

We evaluated the association between TAF/FTC and TDF/FTC exposure against SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19 among PLWH, mitigating the limitations in existing studies by adjusting adequately for potential baseline confounders.

Patients and methods

Study population and design

We performed a retrospective study using data from the Populational HIV Cohort from Catalonia and Balearic Islands (PISCIS). PISCIS is a prospective, multicentre, population-based cohort which follows PLWH aged ≥16 years accessing care at 15 hospitals in Catalonia, Spain.15 We linked PISCIS data with data from several administrative official public health databases to obtain information about chronic comorbidities, SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis, and related clinical outcomes. Data were managed through the Analytical Data for Research and Innovation in Health Project of Catalonia (PADRIS) so as to ensure anonymization in accordance with current data protection legislation.16 The study period was from 1 March 2020 to 18 July 2021. We excluded patients who were reported dead before 1 March 2020, those without information on ART, and those who had at any point switched their ART regimen since cohort entry.

Study definitions and outcomes

We divided the study population into three groups according to nucleos(t)ide reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) exposure: (i) TAF/FTC; (ii) TDF/FTC; and (iii) abacavir/lamivudine (ABC/3TC). The primary outcome variables of interest were SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis confirmed by a positive reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and/or antigen detection; and COVID-19 outcomes graded as asymptomatic, symptomatic requiring community management (mild symptoms managed as outpatients or at the emergency department for <24 h), and hospital admissions (>24 h with any of the following signs: dyspnoea, tachypnoea, hypoxaemia, asphyxia or hyperventilation). Among hospitalized patients, we also assessed admission to the ICU (suffered a respiratory failure or sepsis) and death.

Independent variables in the study included patient sociodemographic characteristics: age; sex; socioeconomic deprivation based on the Catalonian Government socioeconomic deprivation index classified as least deprived, mildly deprived, and moderately/severely deprived;17 and country of origin (Spanish and non-Spanish origin). The HIV-associated variables we included in the study were HIV acquisition risk groups as stated in Table 1; duration since HIV diagnosis in years; CD4 cell count (categorized <350 cells/mm3, 350–499 cells/mm3, and ≥500 cells/mm3) and CD4/CD8 cell ratio; plasma HIV-RNA [detectable and undetectable (≤50 copies/mL)]; and duration on ART in years. We included chronic comorbidities extracted using the International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) and tenth revision (ICD-10-CM) and grouped them into 11 groups (Table S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online).

Table 1.

Propensity score-matcheda baseline characteristics of people living with HIV receiving (i) TAF/FTC versus ABC/3TC, (ii) TDF/FTC versus ABC/3TC, or (iii) TAF/FTC versus TDF/FTC

| TAF/FTC versus ABC/3TC | TDF/FTC versus ABC/3TC | TAF/FTC versus TDF/FTC | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | TAF/FTC | ABC/3TC | Total | TDF/FTC | ABC/3TC | Total | TAF/FTC | TDF/FTC | ||||

| Characteristic | (n = 7024) | (n = 3512) | (n = 3512) | P value | (n = 3052) | (=763) | (n = 2289) | P value | (n = 3080) | (n = 2310) | (n = 770) | P value |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.926 | 1.000 | 0.557 | |||||||||

| Male | 5678 (80.8) | 2841 (80.9) | 2837 (80.8) | 2476 (81.1) | 619 (81.1) | 1857 (81.1) | 2504 (81.3) | 1884 (81.6) | 620 (80.5) | |||

| Female | 1346 (19.2) | 671 (19.1) | 675 (19.2) | 576 (18.9) | 144 (18.9) | 432 (18.9) | 576 (18.7) | 426 (18.4) | 150 (19.5) | |||

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 48.2 (39.6–55.4) | 48.0 (39.4–55.2) | 48.4 (39.8–55.6) | 0.117 | 45.2 (38.0–53.1) | 45.0 (38.3–52.4) | 45.3 (37.9–53.2) | 0.803 | 45.0 (38.3–52.5) | 45.1 (38.3–52.6) | 44.9 (37.9–52.3) | 0.542 |

| Age category, years | 0.642 | 0.893 | 0.587 | |||||||||

| 16–39 | 1832 (26.08) | 932 (26.54) | 900 (25.63) | 1014 (33.2) | 250 (32.8) | 764 (33.4) | 988 (32.1) | 730 (31.6) | 258 (33.5) | |||

| 40–64 | 4706 (67) | 2346 (66.8) | 2360 (67.2) | 1907 (62.5) | 480 (62.9) | 1427 (62.3) | 1957 (63.5) | 1477 (63.9) | 480 (62.3) | |||

| 65–74 | 393 (5.6) | 192 (5.47) | 201 (5.72) | 97 (3.2) | 26 (3.4) | 71 (3.1) | 113 (3.7) | 88 (3.8) | 25 (3.3) | |||

| ≥75 | 93 (1.32) | 42 (1.2) | 51 (1.45) | 34 (1.1) | 7 (0.9) | 27 (1.2) | 22 (0.7) | 15 (0.7) | 7 (0.9) | |||

| Country of origin, n (%) | 0.007 | 0.608 | 0.621 | |||||||||

| Spain | 4354 (62.0) | 2121 (60.4) | 2233 (63.6) | 1838 (60.2) | 453 (59.4) | 1385 (60.5) | 1794 (58.3) | 1339 (58.0) | 455 (59.1) | |||

| Outside Spain | 2669 (38.0) | 1390 (39.6) | 1279 (36.4) | 1214 (39.8) | 310 (40.6) | 904 (39.5) | 1285 (41.7) | 970 (42.0) | 315 (40.9) | |||

| Socioeconomic deprivation, n (%) | 0.001 | 0.978 | 0.032 | |||||||||

| Least deprived | 3361 (47.9) | 1754 (49.9) | 1607 (45.8) | 1443 (47.3) | 361 (47.3) | 1082 (47.3) | 1559 (50.6) | 1196 (51.8) | 363 (47.1) | |||

| Mildly deprived | 1372 (19.5) | 659 (18.8) | 713 (20.3) | 597 (19.6) | 137 (18.0) | 460 (20.1) | 559 (18.2) | 421 (18.2) | 138 (17.9) | |||

| Moderately/severely deprived | 2123 (30.2) | 1021 (29.1) | 1102 (31.4) | 933 (30.6) | 237 (31.1) | 696 (30.4) | 884 (28.7) | 643 (27.8) | 241 (31.3) | |||

| Missing | 168 (2.4) | 78 (2.2) | 90 (2.6) | 79 (2.6) | 28 (3.7) | 51 (2.2) | 78 (2.5) | 50 (2.2) | 28 (3.6) | |||

| HIV acquisition risk group, n (%) | 0.058 | 0.938 | 0.266 | |||||||||

| PWID | 853 (12.1) | 442 (12.6) | 411 (11.7) | 291 (9.5) | 71 (9.3) | 220 (9.6) | 335 (10.9) | 264 (11.4) | 71 (9.2) | |||

| MSM | 3631 (51.7) | 1835 (52.3) | 1796 (51.1) | 1663 (54.5) | 408 (53.5) | 1255 (54.8) | 1663 (54.0) | 1255 (54.3) | 408 (53.0) | |||

| Male heterosexual | 978 (13.9) | 469 (13.4) | 509 (14.5) | 427 (14.0) | 111 (14.6) | 316 (13.8) | 401 (13.0) | 290 (12.6) | 111 (14.4) | |||

| Female hetero/homo/bisexual | 1032 (14.7) | 526 (15.0) | 506 (14.4) | 448 (14.7) | 111 (14.6) | 337 (14.7) | 451 (14.6) | 336 (14.6) | 115 (14.9) | |||

| Other | 397 (5.7) | 175 (5.0) | 222 (6.3) | 171 (5.6) | 46 (6.0) | 125 (5.5) | 175 (5.7) | 126 (5.5) | 49 (6.4) | |||

| Missing | 133 (1.9) | 65 (1.9) | 68 (1.9) | 52 (1.7) | 16 (2.1) | 36 (1.6) | 55 (1.8) | 39 (1.7) | 16 (2.1) | |||

| Years since HIV diagnosis, median (IQR) | 11.7 (6.3–18.1) | 11.6 (6.6–18.1) | 11.8 (6.0–18.1) | 0.877 | 11.1 (5.8–16.9) | 11.7 (7.4–17.2) | 10.8 (5.0–16.8) | <0.001 | 11.0 (6.3–17.0) | 10.7 (6.0–16.8) | 11.7 (7.3–17.1) | 0.001 |

| CD4 count (cells/mm3) category | 0.057 | 0.869 | 0.983 | |||||||||

| <350 | 781 (11.1) | 424 (12.1) | 357 (10.2) | 303 (9.9) | 79 (10.4) | 224 (9.8) | 335 (10.9) | 254 (11.0) | 81 (10.5) | |||

| 350–499 | 981 (14.0) | 482 (13.7) | 499 (14.2) | 431 (14.1) | 105 (13.8) | 326 (14.2) | 428 (13.9) | 320 (13.9) | 108 (14.0) | |||

| ≥500 | 5262 (74.9) | 2606 (74.2) | 2656 (75.6) | 2318 (76.0) | 579 (75.9) | 1739 (76.0) | 2317 (75.2) | 1736 (75.2) | 581 (75.5) | |||

| CD4 count (cells/mm3), median (IQR) | 695.5 (499.0–926.0) | 680.0 (490.0–904.0) | 711.0 (506.0–950.0) | <0.001 | 707.0 (509.8–937.0) | 690.0 (508.0–918.5) | 712.0 (510.0–944.0) | 0.103 | 686.0 (500.0–910.0) | 684.5 (500.0–906.0) | 688.5 (505.3–917.5) | 0.681 |

| CD4/CD8 ratio, median (IQR) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 0.323 | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 0.030 | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 0.011 |

| Plasma HIV-RNA, n (%) | 0.581 | 0.840 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| Detectableb | 511 (7.3) | 262 (7.5) | 249 (7.1) | 219 (7.2) | 53 (7.0) | 166 (7.3) | 220 (7.1) | 165 (7.1) | 55 (7.1) | |||

| Undetectableb | 6513 (92.7) | 3250 (92.5) | 3263 (92.9) | 2833 (92.8) | 710 (93.1) | 2123 (92.8) | 2860 (92.9) | 2145 (92.9) | 715 (92.9) | |||

| Number of comorbidities, n (%) | 0.715 | 0.978 | ||||||||||

| 0 | 2041 (29.1) | 1048 (29.8) | 993 (28.3) | 0.983 | 1218 (39.6) | 920 (39.8) | 298 (38.7) | |||||

| 1 | 1651 (23.5) | 818 (23.3) | 833 (23.7) | 1150 (37.7) | 291 (38.1) | 859 (37.5) | 754 (24.5) | 561 (24.3) | 193 (25.1) | |||

| 2 | 1244 (17.7) | 613 (17.5) | 631 (18.0) | 792 (26.0) | 193 (25.3) | 599 (26.2) | 507 (16.5) | 381 (16.5) | 126 (16.4) | |||

| 3 | 773 (11.0) | 383 (10.9) | 390 (11.1) | 507 (16.6) | 126 (16.5) | 381 (16.6) | 264 (8.6) | 198 (8.6) | 66 (8.6) | |||

| ≥4 | 1315 (18.7) | 650 (18.5) | 665 (18.9) | 253 (8.3) | 66 (8.7) | 187 (8.2) | 337 (10.9) | 250 (10.8) | 87 (11.3) | |||

| Type of comorbidities, n (%) | 350 (11.5) | 87 (11.4) | 263 (11.5) | |||||||||

| Respiratory disease | 1596 (22.7) | 811 (23.1) | 785 (22.4) | 0.477 | 539 (17.5) | 390 (16.9) | 149 (19.4) | 0.132 | ||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 1220 (17.4) | 612 (17.4) | 608 (17.3) | 0.925 | 554 (18.2) | 149 (19.5) | 405 (17.7) | 0.278 | 360 (11.7) | 267 (11.6) | 93 (12.1) | 0.746 |

| Autoimmune disease | 840 (12.0) | 393 (11.2) | 447 (12.7) | 0.051 | 378 (12.4) | 93 (12.2) | 285 (12.5) | 0.899 | 311 (10.1) | 239 (10.4) | 72 (9.4) | 0.468 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 374 (5.3) | 136 (3.9) | 238 (6.8) | <0.001 | 295 (9.7) | 72 (9.4) | 223 (9.7) | 0.860 | 70 (2.3) | 61 (2.6) | 9 (1.2) | 0.026 |

| Chronic liver disease | 1393 (19.8) | 722 (20.6) | 671 (19.1) | 0.135 | 116 (3.8) | 9 (1.2) | 107 (4.7) | <0.001 | 506 (16.4) | 379 (16.4) | 127 (16.5) | 1.000 |

| Neuropsychiatric | 2128 (30.3) | 1077 (30.7) | 1051 (29.9) | 0.516 | 467 (15.3) | 127 (16.6) | 340 (14.9) | 0.258 | 771 (25.0) | 564 (24.4) | 207 (26.9) | 0.187 |

| Diabetes | 464 (6.6) | 210 (6.0) | 254 (7.2) | 0.039 | 746 (24.4) | 207 (27.1) | 539 (23.6) | 0.052 | 126 (4.1) | 89 (3.9) | 37 (4.8) | 0.294 |

| Metabolic disease | 1839 (26.2) | 878 (25.0) | 961 (27.4) | 0.026 | 140 (4.6) | 37 (4.9) | 103 (4.5) | 0.764 | 558 (18.1) | 424 (18.4) | 134 (17.4) | 0.589 |

| Cancer | 789 (11.2) | 381 (10.9) | 408 (11.6) | 0.326 | 598 (19.6) | 134 (17.6) | 464 (20.3) | 0.114 | 228 (7.4) | 161 (7.0) | 67 (8.7) | 0.131 |

| Hypertension | 1630 (23.2) | 790 (22.5) | 840 (23.9) | 0.166 | 262 (8.6) | 67 (8.8) | 195 (8.5) | 0.881 | 504 (16.4) | 384 (16.6) | 120 (15.6) | 0.536 |

| Obesity | 699 (10.0) | 342 (9.7) | 357 (10.2) | 0.577 | 526 (17.2) | 120 (15.7) | 406 (17.7) | 0.223 | 230 (7.5) | 170 (7.4) | 60 (7.8) | 0.752 |

| Years on ART, median (IQR) | 9.9 (5.4–15.3) | 9.8 (5.7–14.9) | 10.1 (5.3–15.5) | 0.213 | 234 (7.7) | 60 (7.9) | 174 (7.6) | 0.875 | 9.5 (5.6–13.7) | 9.3 (5.4–13.6) | 10.4 (6.1–14.1) | 0.003 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; PWID, people who inject drugs; MSM, men who have sex with men; ART, antiretroviral therapy; TAF, tenofovir alafenamide; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; FTC, emtricitabine; ABC/3TC, abacavir/lamivudine.

Propensity score-matching ratio is 1:1 for TAF/FTC versus ABC/3TC, 1:3 for TDF/FTC versus ABC/3TC, and 1:3 for TDF/FTC versus TAF/FTC.

HIV-RNA viral load (detectable: ≥50 copies per mL, undetectable: <50 copies per mL).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as median with interquartile ranges (IQR) and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. Proportions for categorical variables were compared using the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate. Continuous variables were compared using the Kruskal Wallis test. We performed four rounds of propensity-score matching for TAF/FTC versus ABC/3TC and a single round for TDF/FTC versus ABC/3TC and TAF/FTC versus TDF/FTC using nearest-neighbour algorithms with a calliper width of 0.1 of the pooled standard deviations to ensure that key baseline characteristics of the groups were adequately balanced. We matched patients by sex, age, plasma HIV-RNA [detectable and undetectable (HIV RNA <50 copies/mL)], and number of comorbidities (none, one, two, three, four or more). We did three separate propensity score matches in a ratio 1:1 for TAF/FTC versus ABC/3TC, and 1:3 for TDF/FTC versus ABC/3TC, and TDF/FTC versus TAF/FTC. To evaluate the effect of ART regimens on SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis and severe outcomes, we used Cox regression models and provided adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and unadjusted odds ratios (uOR) along with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) to remove residual confounding.18 We adjusted for the factors that were significantly different after propensity score matching. We adjusted for country of origin, socioeconomic status, CD4 count (continuous variable), time in years on ART, CD4/CD8 ratio, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and metabolic disease. In multivariable analysis, we removed the time since HIV diagnosis due to collinearity with the time in years on ART (Table S2). Records of missing values for adjustment covariates were excluded in adjusted analyses, as they were few and not expected to affect estimates significantly. A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. We performed all statistical analyses using R Statistical Software version 4.0.2.

Ethics

The PISCIS cohort study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Germans Trias i Pujol University Hospital, Badalona, Spain (EO-11–108). Data collection was also approved by the ethics committees of participating hospitals. Patient-level information obtained from PADRIS was anonymized and de-identified before the analysis. This study follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.19 The planning, conduct, and reporting of the study was in line with the Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

Access to data

The study protocol is available from Dr Juliana Reyes-Urueña (e-mail: jmreyes@iconcologia.net). Statistical code for the analysis can be requested from Yesika Diáz, Sergio Moreno, and Jordi Aceiton (ydiazr@iconcologia.net, smorenof@iconcologia.net, jaceiton@igtp.cat). The data for this study is available at the Centre for Epidemiological Studies of Sexually Transmitted Diseases and HIV/AIDS in Catalonia (CEEISCAT), the coordinating centre of the PISCIS cohort and from each of the collaborating hospitals upon request via https://pisciscohort.org/contacte/.

Results

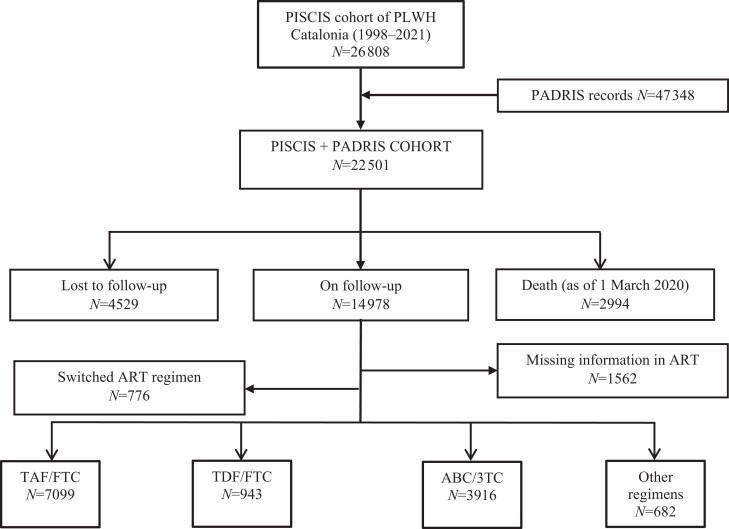

Out of 14 978 PLWH (median age: 46.4 years, male sex: 82.1%) on follow-up in our cohort, 1562 had missing information on ART, 776 had switched their ART regimen at least once during the study period, and 11 958 were included in the present analysis. Of them, 7099 were treated with TAF/FTC, 943 with TDF/FTC, 3916 with ABC/3TC, and 682 were receiving other regimens (Figure 1). PLWH receiving TDF/FTC were younger (median age 44.6 years) compared with those receiving TAF/FTC (45.6 years) or ABC/3TC (48.2 years) (P < 0.001). Individuals receiving TDF/FTC had a lower number of comorbidities than those receiving TAF/FTC or ABC/3TC (P < 0.001) and significantly different socioeconomic deprivation (Table S3).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of people living with HIV in the PISCIS cohort in Catalonia showing the reception ART regimens and inclusion into the analysis. Abbreviations: PADRIS, Analytical Data for Research and Innovation in Health Project of Catalonia; ART, antiretroviral therapy; TAF, tenofovir alafenamide; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; FTC, emtricitabine; ABC/3TC, abacavir/lamivudine.

Of the patients included in the analysis, 1445 (12.1%) individuals had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 as of 18 July 2021, of whom 670 (46.4%) were asymptomatic, 630 (43.6%) were symptomatic with mild disease requiring community management, and 145 (10.0%) were hospitalized. In the latter, 7 (0.5%) were admitted to the ICU, and 20 (1.4%) died.

Out of 7099 PLWH receiving TAF/FTC, 3512 were matched 1:1 to an equal number of ABC/3TC recipients (n = 3512). Out of 943 TDF/FTC recipients, 763 were matched 1:3 to 2289 ABC/3TC recipients; and 770 TDF/FTC recipients were matched 1:3 to 2310 TAF/FTC recipients. No key covariates exhibited major imbalances (standard mean difference <0.1) (Figure S1). The baseline characteristics of the propensity score-matched groups are presented in Table 1.

TAF/FTC was not associated with a reduction in SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis (aOR 0.90; 95% CI, 0.78–1.04) or associated hospitalization (aOR 0.93; 95% CI, 0.60–1.43) compared with ABC/3TC in adjusted analysis. TDF/FTC compared with ABC/3TC was not associated with a reduction in SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis (aOR 0.79; 95% CI, 0.60–1.04) or hospitalization (aOR 0.51; 95% CI, 0.15–1.70). We finally compared the association between TDF/FTC and TAF/FTC in adjusted analysis. TDF/FTC was not associated with a reduction in SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis (aOR 0.79; 95% CI, 0.60–1.04) or associated hospital admissions (aOR 0.33; 95% CI, 0.10–1.07) compared with TAF/FTC (Table 2).

Table 2.

SARS-Cov-2 diagnosis and clinical severity in propensity score-matched groups of PLWH based on antiretroviral therapy (ART) and results from Cox regression models that evaluated the effect of ART regimens on SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis and associated hospitalization

| TAF/FTC versus ABC/3TC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totala | TAF/FTCa | ABC/3TCa,b | P valuec | uOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis | 0.256 | 0.92 (0.80–1.05) | 0.90 (0.78–1.04) | |||

| Positive | 848 (12.1) | 408 (11.6) | 440 (12.5) | |||

| Negative | 6176 (87.9) | 3104 (88.4) | 3072 (87.5) | |||

| Clinical severity | 0.838 | |||||

| Asymptomatic | 380 (44.8) | 186 (45.6) | 194 (44.1) | |||

| Symptomatic mild community management | 370 (43.6) | 172 (42.3) | 198 (45.0) | |||

| Hospitalizationd | 98 (11.6) | 50 (12.3) | 48 (10.9) | 1.04 (0.70–1.55) | 0.93 (0.60 -1.43) | |

| ICU admission | 4 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) | |||

| Deathe | 17 (2.0) | 9 (2.2) | 8 (1.8) | |||

| TDF/FTC versus ABC/3TC | ||||||

| Total | TDF/FTC | ABC/3TCb | P valuec | uOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis | 0.021 | 0.74 (0.57–0.95) | 0.79 (0.60–1.04) | |||

| Positive | 369 (12.0) | 74 (9.6) | 295 (12.8) | |||

| Negative | 2704 (88.0) | 697 (90.4) | 2007 (87.2) | |||

| Clinical severity | 0.352 | |||||

| Asymptomatic | 172 (46.6) | 40 (54.1) | 132 (44.8) | |||

| Symptomatic mild community management | 170 (46.1) | 31 (41.9) | 139 (47.1) | |||

| Hospitalizationd | 27 (7.3) | 3 (4.1) | 24 (8.1) | 0.37 (0.11–1.24) | 0.51 (0.15–1.70) | |

| ICU admission | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.7) | |||

| Deathe | 3 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.0) | |||

| TAF/FTC versus TDF/FTC | ||||||

| Total | TAF/FTCb | TDF/FTC | P valuec | uOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis | 0.012 | 0.72 (0.56–0.93) | 0.79 (0.60–1.04) | |||

| Positive | 377 (12.2) | 303 (13.1) | 74 (9.6) | |||

| Negative | 2703 (87.8) | 2007 (86.9) | 696 (90.4) | |||

| Clinical severity | 0.274 | |||||

| Asymptomatic | 190 (50.4) | 150 (49.5) | 40 (54.1) | |||

| Symptomatic mild community management | 150 (39.8) | 119 (39.3) | 31 (41.9) | |||

| Hospitalizationd | 37 (9.8) | 34 (11.2) | 3 (4.1) | 0.26 (0.08–0.86) | 0.33 (0.10–1.07) | |

| ICU admission | 3 (0.8) | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0) | |||

| Deathe | 6 (1.6) | 6 (2.0) | 0 (0) | |||

Adjusted model: Adjusted for country of origin, socioeconomic status, CD4 count (continuous variable), time in years on ART, CD4/CD8 ratio, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, and metabolic disease.

Abbreviations: TAF, tenofovir alafenamide; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; FTC, emtricitabine; ABC/3TC, abacavir/lamivudine; ICU, intensive care unit, SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; OR, odds ratio; uOR, unadjusted odds ratio; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Data in this category is presented as n (%).

Reference group for odds ratios.

Numbers in bold indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Including ICU admissions.

Also included in hospitalized patients.

Discussion

We assessed the association between current TAF/FTC and TDF/FTC treatment and SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis and COVID-19 outcomes in a prospective multicentre cohort of PLWH using a propensity score-matched approach. TAF/FTC and TDF/FTC were not significantly associated with a reduction in SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis and poorer COVID-19-related outcomes including hospitalizations, ICU admissions, and death among PLWH. We found no significant association either when TAF/FTC or TDF/FTC were compared with ABC/3TC or against each other.

Importantly, we found significantly lower rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection and associated hospitalizations in unadjusted analyses among those receiving TDF/FTC. Compared with patients receiving TAF/FTC and ABC/3TC, those receiving TDF/FTC were significantly younger, and had a lower number and prevalence of comorbidities. When the analysis was adjusted for these variables, the potential protective effect disappeared. This finding supports that the differences in baseline factors intrinsically associated with lower SARS-CoV-2 infection rates and more benign SARS-CoV-2 infection outcomes constitute a channelling bias that could have influenced many previous analyses that indicated that TDF could have a protective role against SARS-CoV-2 infection, but lacked an adequate adjustment of these variables that are directly correlated with the primary outcome.7,11

Analyses performed in PrEP studies with TDF/FTC, such as PREVENIR-ANRS and SAPRIS-Sero14 sub-study from France, where these biases do not exist, found no reduced risk in SARS-CoV-2 infection among TDF/FTC PrEP users.

Similarly, TDF/FTC in our study reduced COVID-19-associated hospitalizations in unadjusted analysis but not in adjusted analysis, which is contrary to previous large studies.7,11 As previously discussed, the lack of adjustment for baseline patient characteristics probably influenced the results of the study from del Amo et al.7 by confounding and channelling bias. In the subsequent large study from the Western Cape, South Africa,11 there was an adjustment for kidney disease, viral suppression, and antiretroviral treatment. Zidovudine use (the alternative to TDF), however, was preferentially prescribed to individuals with prior virologic failure as per the WHO guidelines20 and can be associated with higher rates of tuberculosis, both of which were not adjusted for in that study.

The rationale behind the possible protective benefits of tenofovir was a result of the potential activity that the nucleotide analogue showed against SARS-CoV-2 in pre-clinical studies and animal models (ferrets)4,21 and the more potent immunomodulatory effects of TDF22 including the decreased production of interleukin-8 and -10,23 and the higher penetration into mucosal tissues.24 However, in a recent analysis, none of these drugs (TAF, TDF or FTC) showed any significant in vitro anti-SARS-CoV-2 effect at concentrations up to 100-fold higher than the clinically relevant levels.6 These results are corroborated by the lack of interaction between the respective NRTI-triphosphates and SARS-CoV-2 RdRp observed both in biochemical assays and in structural modelling analyses.6

Our finding that TAF does not prevent SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis or severe disease is in-line with a report from Ayerdi et al.13 who actually found a higher SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence among HIV-negative PrEP users receiving TAF or TDF versus those without PrEP. That study also demonstrated no differences in terms of clinical manifestations between people receiving tenofovir (TAF or TDF) and those not on tenofovir.13

The study by del Amo et al.7 found a lower risk for SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis among persons receiving TDF/FTC compared with those on other regimens. SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis in Spain has also been disproportionately affected by sociodemographic factors including country of origin and socioeconomic status in both the general population25 and among PLWH.15 The del Amo et al.7 study did not adjust for these sociodemographic factors.

In recent findings from a clinical trial involving 30 participants on TDF/FTC and a control group of 30 participants on standard of care therapy, TDF/FTC did not expedite the natural clearance of nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 viral load at day 4 (primary endpoint), there were no differences in the time to symptom recovery nor in the hospitalization rates.26 However, there was a significantly greater increase in the Ct RT-PCR on the seventh day, with an effect corresponding to approximately 0.8 log10 decrease of SARS-CoV-2 RNA, a reduction of unknown microbiological or clinical relevance.

Our study is limited by its epidemiological nature, depriving us of having information on treatment adherence and exposure to SARS-CoV-2, which are both relevant given the objectives of our study. Secondly, assessing the association between ART and SARS-CoV-2 infection is challenging in a scenario where not everyone is tested equally for SARS-CoV-2. For example, testing could be more frequent among patients with higher risks of poor COVID-19 outcomes. The identification of a higher incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection and associated hospitalizations in unadjusted analyses that disappears in the propensity score matching and adjusted Cox regression models suggests that indeed subjects treated with TDF have intrinsic characteristics that lend them a lower risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection or poorer COVID-19 outcomes. Our analyses demonstrate that failure to evaluate potential sociodemographic and clinical confounding factors can bias observational study results and lead to erroneous inferences.

In conclusion, the use of TAF/FTC or TDF/FTC among PLWH was not associated with a reduction in SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis or poorer COVID-19 outcomes including hospital and ICU admissions or death. Until well-designed randomized clinical trials reveal new robust evidence, existing preventive measures and treatment approaches for PLWH against SARS-CoV-2 infection should be maintained, independent of tenofovir exposure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Public Data Analysis for Health Research and Innovation Program of Catalonia (PADRIS) and the Programme for the Prevention, Control and Care for HIV, Sexually Transmitted Diseases and Viral Hepatitis (PCAVIHV) of the Ministry of Health, Government of Catalonia for their support.

Contributor Information

Daniel K Nomah, Centre Estudis Epidemiològics sobre les Infeccions de Transmissió Sexual i Sida de Catalunya (CEEISCAT), Dept Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Badalona, Spain; Departament de Pediatria, d’Obstetrícia i Ginecologia i de Medicina Preventiva i de Salut Publica, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, Spain; Institut d’Investigació Germans Trias i Pujol (IGTP), Barcelona, Spain.

Juliana Reyes-Urueña, Centre Estudis Epidemiològics sobre les Infeccions de Transmissió Sexual i Sida de Catalunya (CEEISCAT), Dept Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Badalona, Spain; Institut d’Investigació Germans Trias i Pujol (IGTP), Barcelona, Spain; CIBER Epidemiologia y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), Barcelona, Spain.

Yesika Díaz, Centre Estudis Epidemiològics sobre les Infeccions de Transmissió Sexual i Sida de Catalunya (CEEISCAT), Dept Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Badalona, Spain; Institut d’Investigació Germans Trias i Pujol (IGTP), Barcelona, Spain.

Sergio Moreno, Centre Estudis Epidemiològics sobre les Infeccions de Transmissió Sexual i Sida de Catalunya (CEEISCAT), Dept Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Badalona, Spain; Institut d’Investigació Germans Trias i Pujol (IGTP), Barcelona, Spain.

Jordi Aceiton, Centre Estudis Epidemiològics sobre les Infeccions de Transmissió Sexual i Sida de Catalunya (CEEISCAT), Dept Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Badalona, Spain; Institut d’Investigació Germans Trias i Pujol (IGTP), Barcelona, Spain.

Andreu Bruguera, Centre Estudis Epidemiològics sobre les Infeccions de Transmissió Sexual i Sida de Catalunya (CEEISCAT), Dept Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Badalona, Spain; Departament de Pediatria, d’Obstetrícia i Ginecologia i de Medicina Preventiva i de Salut Publica, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, Spain; Institut d’Investigació Germans Trias i Pujol (IGTP), Barcelona, Spain.

Rosa M Vivanco-Hidalgo, Agència de Qualitat i Avaluació Sanitàries de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain.

Jordi Casabona, Centre Estudis Epidemiològics sobre les Infeccions de Transmissió Sexual i Sida de Catalunya (CEEISCAT), Dept Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Badalona, Spain; Departament de Pediatria, d’Obstetrícia i Ginecologia i de Medicina Preventiva i de Salut Publica, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, Spain; Institut d’Investigació Germans Trias i Pujol (IGTP), Barcelona, Spain; CIBER Epidemiologia y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), Barcelona, Spain.

Pere Domingo, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona, Spain.

Jordi Navarro, Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), Hospital de Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona, Spain.

Arkaitz Imaz, Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBELL), University of Barcelona, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Spain.

Elisabet Deig, Hospital General de Granollers, Granollers, Spain.

Gemma Navarro, Unitat de VIH/SIDA, Corporació Sanitària i Universitària Parc Taulí-Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Sabadell, Spain.

Josep M Llibre, Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona, Spain.

Jose M Miro, Hospital Clínic-Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

PISCIS study group:

Esteve Muntada, Anna Esteve, Francisco Fanjul, Vicenç Falcó, Hernando Knobel, Josep Mallolas, Juan Tiraboschi, Adrià Curran, Joaquín Burgos, Boris Revollo, Maria Gracia, Maria del Mar Gutierrez, Javier Murillas, Francisco Homar, Jose V Fernández-Montero, Eva González, Joaquim Peraire, Lluís Force, Elena Leon, Miquel Hortos, Ingrid Vilaró, Amat Orti, David Dalmau, Àngels Jaen, Elisa De Lazzari, Leire Berrocal, Lucía Rodríguez, Freya Gargoulas, Toni Vanrell, Jose Carlos, Josep Vilà, Marina Martínez, Bibiana Morell, Maribel Tamayo, Jorge Palacio, Juan Ambrosioni, Montse Laguno, María Martínez-Rebollar, José L Blanco, Felipe Garcia, Berta Torres, Lorena de la Mora, Alexy Inciarte, Ainoa Ugarte, Iván Chivite, Ana González-Cordon, Lorna Leal, Antoni Jou, Eugènia Negredo, Maria Saumoy, Ana Silva, Sofia Scévola, Paula Suanzes, Patricia Alvarez, Isabel Mur, Melchor Riera Jaume, Mercedes García-Gasalla, Maria À Ribas, Antoni A Campins, María Peñaranda, María L Martin, Helem Haydee, Sònia Calzado, Manel Cervantes, Marta Navarro, Antoni Payeras, Carmen Cifuentes, Aroa Villoslada, Patrícia Sorní, Marta Molero, Nadia Abdulghani, Thaïs Comella, Rocio Sola, Montserrat Vargas, Consuleo Viladés, Anna Martí, Elena Yeregui, Anna Rull, Pilar Barrufet, Laia Arbones, Elena Chamarro, Cristina Escrig, Mireia Cairó, Xavier Martinez-Lacasa, Roser Font, Lizza Macorigh, and Juanse Hernández

Members of the PISCIS study group

Esteve Muntada, Anna Esteve, Francisco Fanjul, Vicenç Falcó, Hernando Knobel, Josep Mallolas, Juan Tiraboschi, Adrià Curran, Joaquín Burgos, Boris Revollo, Maria Gracia, Maria del Mar Gutierrez, Javier Murillas, Francisco Homar, Jose V. Fernández-Montero, Eva González, Joaquim Peraire, Lluís Force, Elena Leon, Miquel Hortos, Ingrid Vilaró, Amat Orti, David Dalmau, Àngels Jaen, Elisa De Lazzari, Leire Berrocal, Lucía Rodríguez, Freya Gargoulas, Toni Vanrell, Jose Carlos, Josep Vilà, Marina Martínez, Bibiana Morell, Maribel Tamayo, Jorge Palacio, Juan Ambrosioni, Montse Laguno, María Martínez-Rebollar, José L. Blanco, Felipe Garcia, Berta Torres, Lorena de la Mora, Alexy Inciarte, Ainoa Ugarte, Iván Chivite, Ana González-Cordon, Lorna Leal, Antoni Jou, Eugènia Negredo, Maria Saumoy, Ana Silva, Sofia Scévola, Paula Suanzes, Patricia Alvarez, Isabel Mur, Melchor Riera Jaume, Mercedes García-Gasalla, Maria À. Ribas, Antoni A. Campins, María Peñaranda, María L. Martin, Helem Haydee, Sònia Calzado, Manel Cervantes, Marta Navarro, Antoni Payeras, Carmen Cifuentes, Aroa Villoslada, Patrícia Sorní, Marta Molero, Nadia Abdulghani, Thaïs Comella, Rocio Sola, Montserrat Vargas, Consuleo Viladés, Anna Martí, Elena Yeregui, Anna Rull, Pilar Barrufet, Laia Arbones, Elena Chamarro, Cristina Escrig, Mireia Cairó, Xavier Martinez-Lacasa, Roser Font, Lizza Macorigh, Juanse Hernández.

Funding

This work was supported by Fundació ‘La Caixa’ (grant number: COVIHCAT). The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or report writing.

Transparency declarations

J.M.M. reported receiving a personal 80:20 research grant from Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Spain, during 2017–22 and consulting honoraria and/or research grants from Angelini, Contrafect, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Jansen, Lysovant, Medtronic, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, and ViiV Healthcare, outside the submitted work. P.D. reported that his institution received grants from Gilead Sciences, Janssen & Cilag, and ViiV Healthcare; and he personally received honoraria from Gilead Sciences, Janssen & Cilag, MSD, ViiV Healthcare, Roche, and Thera Technologies. A.I. reported that his institution received grants from Gilead Sciences and MSD; and he personally received consultation fees from Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, and Thera Technologies; honoraria for lectures and presentations from Gilead Sciences, MSD, Jansen, and ViiV Healthcare; travel support for attending meetings from Gilead Sciences, Jansen, and ViiV Healthcare. J.M.L. has received honoraria from Gilead Sciences, Janssen-Cilag, and ViiV Healthcare outside of the present work. J.N. has received honoraria and/or speakers’ fees from Abbvie, Gilead, Janssen-Cilag, Merck Sharp & Dohme and ViiV Healthcare outside of the submitted work. All other authors: none to declare.

Author contributions

D.K.N., J.R.U., Y.D., and J.M.M. conceived and designed the study. D.K.N., J.R.U., Y.D. had full access to all of the study data, verified the data, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. D.K.N., J.R.U., Y.D., S.M. and J.A. performed the analyses. D.K.N. and J.R.U. wrote the first draft of the paper and incorporated revisions. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results. All authors critically revised and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary data

Figure S1 and Tables S1 to S4 are available as Supplementary data at JAC Online.

References

- 1. Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZet al. . Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA 2020; 323: 1824–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Riddell J, Amico KR, Mayer KH. HIV preexposure prophylaxis: a review. JAMA 2018; 319: 1261–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zanella I, Zizioli D, Castelli Fet al. . Tenofovir, another inexpensive, well-known and widely Available old drug repurposed for SARS-COV-2 infection. Pharmaceuticals 2021; 14: 454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Elfiky AA. Ribavirin, remdesivir, sofosbuvir, galidesivir, and tenofovir against SARS-CoV-2 RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp): A molecular docking study. Life Sci 2020; 253: 117592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chien M, Anderson TK, Jockusch Set al. . Nucleotide Analogues as Inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Polymerase, a Key Drug Target for COVID-19. J Proteome Res 2020; 19: 4690–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Feng J, Bilello J, Babusis Det al. . NRTIs tenofovir, TAF, TDF, and FTC are inactive against SARS-CoV-2. HIV Med 2021; 22. 10.1111/hiv.13183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. del Amo J, Polo R, Moreno Set al. . Incidence and severity of COVID-19 in HIV-positive persons receiving antiretroviral therapy. Ann Intern Med 2021; 174: 581–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hall AM, Hendry BM, Nitsch Det al. . Tenofovir-associated kidney toxicity in HIV-infected patients: a review of the evidence. Am J Kidney Dis 2011; 57: 773–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baxi SM, Scherzer R, Greenblatt RMet al. . Higher tenofovir exposure is associated with longitudinal declines in kidney function in women living with HIV. AIDS 2016; 30: 609–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sutton SS, Magagnoli J, Hardin JWet al. . Association of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate exposure with chronic kidney disease and osteoporotic fracture in US veterans with HIV. Curr Med Res Opin 2020; 36: 1635–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Western Cape Department of Health in collaboration with the National Institute for Communicable Diseases SA . Risk Factors for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Death in a Population Cohort Study from the Western Cape Province, South Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73: e2005–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Muñoz B, Buti M, Vazquez I. Tenofovir reduces severity of COVID-19 infection in chronic hepatitis B patients. EASL International Liver Congress, 23–26 June 2021. Abstract PO-1449. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ayerdi O, Puerta T, Clavo Pet al. . Preventive efficacy of tenofovir/emtricitabine against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 among pre-exposure prophylaxis users. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020; 7: ofaa455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Delaugerre C, Assoumou L, Maylin S. SARS CoV-2 seroprevalence among HIV-negative participants using tenofovir/emtricitabine-based PrEP in 2020: a sub-study of PREVENIR-ANRS and SAPRIS-Sero. 11th IAS Conference on HIV Science, 18–21 July 2021. Abstract OAC0201. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nomah D, Reyes-Urueña J, Díaz Yet al. . Sociodemographic, clinical, and immunological factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis and severe COVID-19 outcomes in people living with HIV: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet HIV 2021; 3018: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Generalitat de Catalunya . Agència de Qualitat i Avaluació Sanitàries de Catalunya. Programa públic d’analítica de dades per a la recerca i la innovació en salut a Catalunya – PADRIS. 2017. https://aquas.gencat.cat/web/.content/minisite/aquas/publicacions/2017/Programa_analitica_dades_PADRIS_aquas2017.pdf.

- 17. García-Altés A, Ruiz-Muñoz D, Colls Cet al. . Socioeconomic inequalities in health and the use of healthcare services in Catalonia: analysis of the individual data of 7.5 million residents. J Epidemiol Community Health 2018; 72: 871–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nguyen T-L, Collins GS, Spence Jet al. . Double-adjustment in propensity score matching analysis: choosing a threshold for considering residual imbalance. BMC Med Res Methodol 2017; 17: 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger Met al. . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bull World Health Organ 2007; 85: 867–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. World Health Organization . Policy brief: update of recommendations on first-and second-line antiretroviral regimens. 2019. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/325892/WHO-CDS-HIV-19.15-eng.pdf.

- 21. Park S-J, Yu K-M, Kim Y-Iet al. . Antiviral efficacies of FDA-approved drugs against SARS-CoV-2 infection in ferrets. MBio 2020; 11: e01114-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Castillo-Mancilla JR, Meditz A, Wilson Cet al. . Reduced immune activation during tenofovir-emtricitabine therapy in HIV-negative individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 68: 495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Melchjorsen J, Risør MW, Søgaard OSet al. . Tenofovir selectively regulates production of inflammatory cytokines and shifts the IL-12/IL-10 balance in human primary cells. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011; 57: 265–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cottrell ML, Garrett KL, Prince Het al. . Single-dose pharmacokinetics of tenofovir alafenamide and its active metabolite in the mucosal tissues. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017; 72: 1731–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pollán M, Pérez-Gómez B, Pastor-Barriuso Ret al. . Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Spain (ENE-COVID): a nationwide, population-based seroepidemiological study. Lancet 2020: 535–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Parienti J-J, Prazuck T, Peyro-Saint-Paul Let al. . Effect of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine on nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 viral load burden amongst outpatients with COVID-19: A pilot, randomized, open-label phase 2 trial. EClinicalMedicine 2021; 38: 100993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.