This editorial refers to ‘Cardiopulmonary assessment prior to returning to high-hazard occupations post symptomatic COVID-19 infection : a position statement of the Aviation and Occupational Cardiology Task Force of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology’ by R. Rienks et al.https://doi.org/doi:10.1093/eurjpc/zwac041.

Since the first outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus 2 in late 2019, and across its progressive spreading to pandemic, medical community has been making constant progresses in prevention, treatment and management of COVID-19 disease. Beyond the efforts to fight the virus spread and to cure the acute infection, the need of bringing back people recovered from COVID-19 to their life has become a priority. Indeed, even if the majority of COVID-19 infections recovers without residual symptoms, a variable percentage of patients experiences the ‘post-COVID-19 syndrome’—a wide spectrum of long-lasting (beyond 12 weeks) clinical manifestations, including cardiopulmonary, renal and neurological problems.1 The prevalence and the severity of post-COVID-19 syndrome are related to the age and the frailty of the subjects, occurring more frequently after severe diseases requiring prolonged hospitalization. Nevertheless, it does not affect only elderly people, being diagnosed in about 40% of subjects between 18 and 49 years.2 Therefore, the need of evaluate active workers before reincorporation, providing a certification or simply reassuring the patient, is a frequent task common to general practitioners and specialists.

In this issue of the Journal, Rienks et al.3 on behalf of the Aviation and Occupational Cardiology Task Force of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology offer a new tool to evaluate patients prior to returning to high-hazard occupations focused on the cardiopulmonary assessment. The position statement provides a step-by-step indication to guide employers, and the structures regularly involved in medical assessment of workers, throughout a pragmatic approach. The document addresses the specific context of high-hazard occupations, where the required medical standards are high and justified by the risks and responsibilities of the employees, defining a standard tool for post-COVID-19 health management.

Of note, the statement is easily developed recommending a first-line triage aimed to rule out subjects at very low risk, who did not experience any symptom during infection. The second step consists of a flow chart addressing the severity of the disease course and the persistence of respiratory symptoms, chest pain, palpitations or the inability to return to baseline fitness levels. This patient-based approach is thought to identify the clinical ‘red flags’ requiring further specific assessments to unmask the presence of underlying pathology. In case of an abnormal finding (for example in case of palpitations associated with ectopic ventricular beat at electrocardiogram), the statement clearly refers to additional diagnostic workups, ensuring the most accurate management of the patients.

The most interesting element of the statement is the use of cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET), with a strong recommendation in subjects at risk of post-COVID-19 cardiopulmonary disease. The authors identify the CPET as a gatekeeper for additional investigations and as the standard for an accurate assessment of systemic response to exercise. CPET is able to identify the mechanisms responsible of functional limitation resulting as an effective tool to assess post-COVID-19 subjects, consistently with early reports4,5 and current clinical use.6

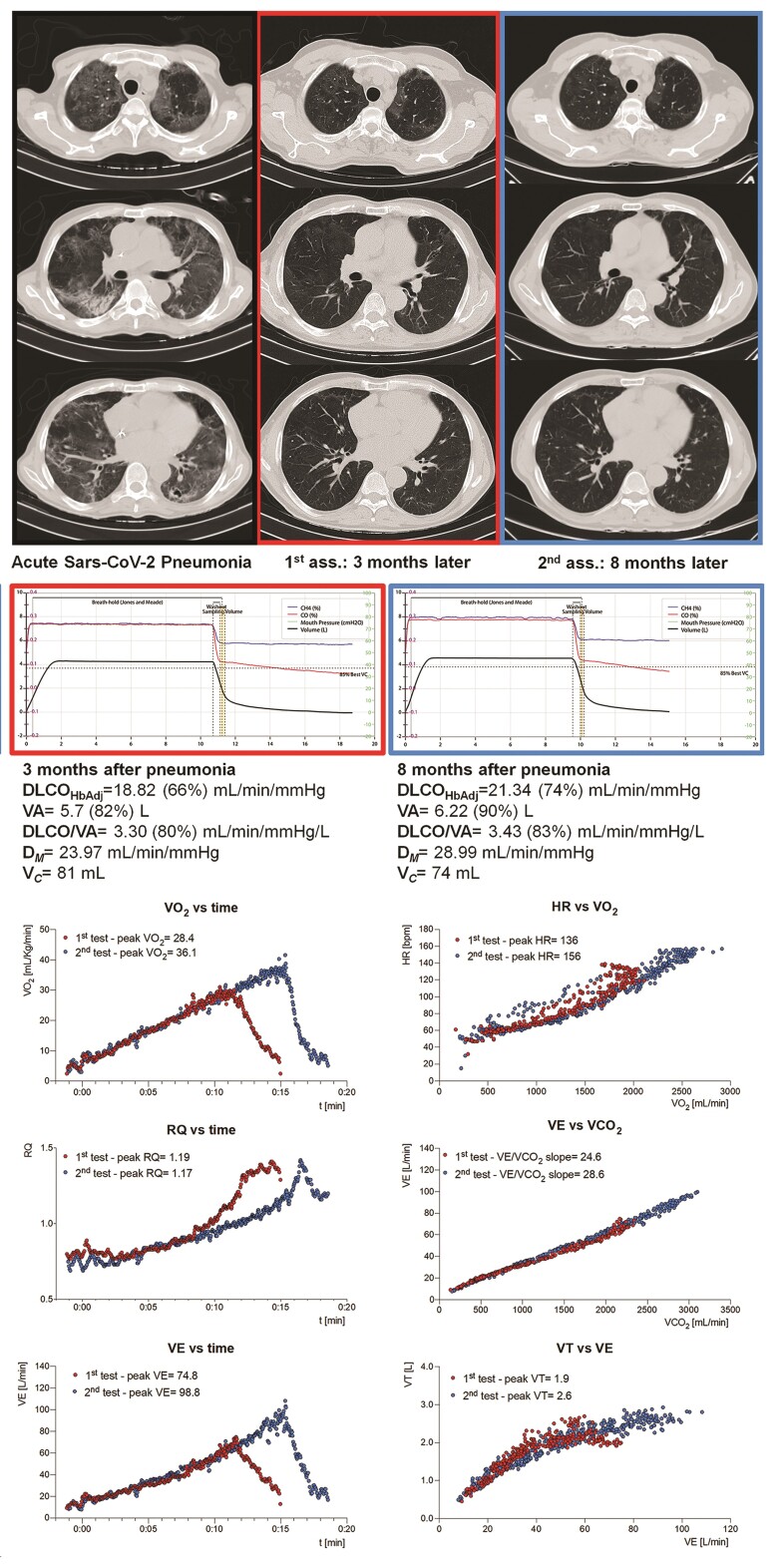

Post-COVID-19 sequelae are often characterized by asthenia, effort intolerance and dyspnoea, requiring an objective assessment of symptoms and their causes. Several reports had shown the low prevalence of severe cardiac involvement and therefore the limited clinical value of indiscriminate use of echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance.7 Similarly, chest imaging may be more effective in detecting the expected lung healing process rather than identifying subjects with specific conditions requiring additional treatments. On the other hand, CPET investigating the exercise-induced reserve of several systems (including cardiac, pulmonary and autonomic systems) provides an actual quantification of effort tolerance and identifies specific patterns of functional limitation. An example of post-COVID-19 CPET use is shown in Figure 1, where the follow-up (carried out with lung diffusion and chest imaging) of a 61-year-old man, who practiced high-altitude trail running before infection, is reported. Despite the severity of the acute disease, requiring prolonged invasive ventilation, and determining a mild impairment of alveolar diffusion at 3 months follow-up, the subject exhibited a globally preserved functional capacity (% of predicted peak VO2 = 94%) at the first assessment. Remarkably, 5 months later, its effort tolerance further improved (% of predicted peak VO2 = 121%), driven by higher peak tidal volume, peak minute ventilation and chronotropic reserve, as confirmed by alveolar diffusion. The very high level of pre-COVID-19 physical fitness reasonably explains the disparity between disease severity and the rapid functional recovery. This example well fits with the present statement addressing people with high-hazard occupations, generally expected to be above the average with respect to physical performance.

Figure 1.

Example of post-Covid-19 assessment with CPET. From top to bottom: CT scan, DLCO and CPET. The upper panel shows the acute lung infection with typical diffuse ground glass attenuation, few cavitary lesions, peripheral consolidations, mild fibrotic lobular distortion and focal, sub-centimetric peripheral thromboembolic lesion involving inferior left lobe, followed by the progressive resolution of lung involvement. The mid-panel shows the initial mild impairment of DLCO (with reduced VA and DM) followed by a global improvement of alveolar diffusion. The lower panel presents the first and second CPET. The peak VO2 significantly improved and was associated with a better chronotropic response and greater ventilatory response. DLCOHbAdj, Haemoglobin-adjusted lung diffusion for CO; VA, alveolar volume; DM, membrane component; Vc, capillary volume; HR, heart rate; RQ, respiratory quotient; VE, minute ventilation; VT, tidal volume.

If the position statement stands out for the global vision on the role of CPET in post-COVID-19 functional assessment, some issues of this approach remain to be addressed. The thresholds to discriminate physiological form pathological response are not univocal, especially with a multiparametric approach, and their interpretation requires specific expertise. The prognostic value of main CPET parameters relies on large scientific evidence, but it is currently limited to non-COVID conditions. In a population-perspective, the value of CPET is unquestionable, but with the single patient it can result challenging to unequivocally define a normal response. A recent study5 reported a predicted peak VO2 lower than 80% in about 60% of subjects with long-COVID-19 syndrome, with a very high prevalence of ventilatory abnormalities (about 90%) and circulatory impairment (due to abnormal stroke volume or pulmonary pressure response) in a sub-group studied with exercise haemodynamic. These results confirm the strategic role of CPET in dealing with post-COVID-19 subjects, but they also remark the potential complexity of interpreting the test. Additional studies, defining the degrees and the patterns of post-COVID-19 functional impairment on a large-scale population would be advised to definitely state the role of CPET. However, the statement is addressed to specialists called to high-responsibility evaluation and generally supported by high experience in the field.

The position statement published in this number of the Journal is a new valuable tool aimed at dealing with post-COVID-19 subjects employed in high-hazard occupations, with a sharp perspective focused on the functional assessment where the use of CPET is pivotal. This approach is consistent with the recent ACC Expert Consensus8 addressing the management of post-COVID-19 sequalae in the general adult population, where the presence of exercise intolerance or dyspnoea is considered indication for CPET. The document proposed by Rienks et al.3 has been designed for high-hazard occupations, but the centrality of physical stress test and its pathophysiological significance may expand the frame of interest to a wider population.

References

- 1. Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, McGroder C, Stevens JS, Cook JR, Nordvig AS, Shalev D, Sehrawat TS, Ahluwalia N, Bikdeli B, Dietz D, Der-Nigoghossian C, Liyanage-Don N, Rosner GF, Bernstein EJ, Mohan S, Beckley AA, Seres DS, Choueiri TK, Uriel N, Ausiello JC, Accili D, Freedberg DE, Baldwin M, Schwartz A, Brodie D, Garcia CK, Elkind MSV, Connors JM, Bilezikian JP, Landry DW, Wan EY. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med 2021;27:601–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, Graham MS, Penfold RS, Bowyer RC, Pujol JC, Klaser K, Antonelli M, Canas LS, Molteni E, Modat M, Jorge Cardoso M., May A, Ganesh S, Davies R, Nguyen LH, Drew DA, Astley CM, Joshi AD, Merino J, Tsereteli N, Fall T, Gomez MF, Duncan EL, Menni C, Williams FMK, Franks PW, Chan AT, Wolf J, Ourselin S, Spector T, Steves CJ. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat Med 2021;27:626–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rienks R, Holdsworth D, Davos CH, Halle M, Bennett A, Parati G, Guettler N, Nicol E. Cardiopulmonary assessment prior to returning to high-hazard occupations post symptomatic COVID-19 infection : a position statement of the Aviation and Occupational Cardiology Task Force of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Motiejunaite J, Balagny P, Arnoult F, Mangin L, Bancal C, d’Ortho MP, Frija-Masson J. Hyperventilation: a possible explanation for long-lasting exercise intolerance in mild COVID-19 survivors? Front Physiol 2021;11: 614590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mancini DM, Brunjes DL, Lala A, Trivieri MG, Contreras JP, Natelson BH. Use of cardiopulmonary stress testing for patients with unexplained dyspnea post–coronavirus disease. JACC Heart Failure 2021;9:927–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guazzi M, Bandera F, Ozemek C, Systrom D, Arena R. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing: what is its value? J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:1618–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Udelson JE, Rowin EJ, Maron BJ. Return to play for athletes after COVID-19 infection: the fog begins to clear. JAMA Cardiol 2021;6:997–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gluckman TJ, Bhave NM, Allen LA, Chung EH, Spatz ES, Ammirati E, Baggish AL, Bozkurt B, Cornwell WK III, Harmon KG, Kim JH, Lala A, Levine BD, Martinez MW, Onuma O, Phelan D, Puntmann VO, Rajpal S, Taub PR, Verma AK. 2022 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on cardiovascular sequelae of COVID-19 in adults: myocarditis and other myocardial involvement, post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and return to play: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol; doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]