Abstract

Background

We evaluated clinical effectiveness of regdanvimab (CT-P59), a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 neutralizing monoclonal antibody, in reducing disease progression and clinical recovery time in patients with mild-to-moderate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), primarily Alpha variant.

Methods

This was phase 3 of a phase 2/3 parallel-group, double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Outpatients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 were randomized to single-dose regdanvimab 40 mg/kg (n = 656) or placebo (n = 659), alongside standard of care. The primary endpoint was COVID-19 disease progression up to day 28 among “high-risk” patients. Key secondary endpoints were disease progression (all randomized patients) and time to recovery (high-risk and all randomized patients).

Results

Of 1315 randomized patients, 880 were high risk; the majority were infected with Alpha variant. The proportion with disease progression was lower (14/446, 3.1% [95% confidence interval {CI}, 1.9%–5.2%] vs 48/434, 11.1% [95% CI, 8.4%–14.4%]; P < .001) and time to recovery was shorter (median, 9.27 days [95% CI, 8.27–11.05 days] vs not reached [95% CI, 12.35–not calculable]; P < .001) with regdanvimab than placebo. Consistent improvements were seen in all randomized and non-high-risk patients who received regdanvimab. Viral load reductions were more rapid with regdanvimab. Infusion-related reactions occurred in 11 patients (4/652 [0.6%] regdanvimab, 7/650 [1.1%] placebo). Treatment-emergent serious adverse events were reported in 5 of (4/652 [0.6%] regdanvimab and 1/650 [0.2%] placebo).

Conclusions

Regdanvimab was an effective treatment for patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19, significantly reducing disease progression and clinical recovery time without notable safety concerns prior to the emergence of the Omicron variant.

Clinical Trials Registration

NCT04602000; 2020-003369-20 (EudraCT).

Keywords: COVID-19 treatment, CT-P59, regdanvimab, SARS-CoV-2

Compared with placebo, regdanvimab effectively reduced the rate of disease progression, shortened time to recovery and more rapidly reduced viral load in patients with mild-to-moderate SARS-CoV-2 alpha variant at high risk of progression to severe disease. No notable safety concerns were observed.

KEY POINTS.

Compared with placebo, regdanvimab effectively reduced the rate of disease progression, shortened time to recovery, and more rapidly reduced viral load in patients with mild-to-moderate SARS-CoV-2 Alpha variant at high risk of progression to severe disease. No notable safety concerns were observed.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a global health crisis [1], with more than 532 million confirmed cases and 6.3 million deaths as of 10 June 2022 [2]. Approximately 15% of patients with COVID-19 develop severe or critical illness associated with serious complications and increased mortality, such as severe pneumonia, with increased respiratory rate, severe respiratory distress, or reduced oxygen saturation [3].

Therapeutic agents such as monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against the spike protein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) can be important treatments to prevent disease progression and hospitalization, and they have been used intensely during the Alpha and particularly the Delta variant waves as the therapeutic focus in COVID-19 shifted from late-disease intensive care toward preemptive outpatient treatment and reduction of severe disease [4–6]. This was especially true before the emergence of the Omicron variant as the dominant strain, which induces a less severe disease course compared with the previously dominant Delta variant (with reported reductions in hospitalization rate, admittance to intensive care, oxygen therapy, acute respiratory distress syndrome rates, and deaths) [7–11].

Binding assays showed that most clinically approved therapeutic antibodies were highly active against the Delta variant but failed to bind to the spike protein from Omicron [12, 13]. While 1 mAb, sotrovimab, did bind, neutralization activity was reduced compared with the Delta variant [14].

Regdanvimab (formerly known as CT-P59), is a fully human mAb that blocks interaction between the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein receptor-binding domain and the cellular angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor [15]. It was developed at the point when the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a public health emergency at the end of January 2020, and was an important treatment in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, before the spread of the Omicron variant. Regdanvimab was granted marketing authorization by the South Korean Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS) on 17 September 2021 [16], and by the European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) on 12 November 2021 [17]. The clinical data supporting the approval of regdanvimab included 2 phase 1 single-dose studies, where regdanvimab showed a promising safety profile in healthy volunteers and patients with mild COVID-19, and potential antiviral and clinical efficacy against mild infections [18], as well as a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 2/3 study that evaluated regdanvimab in patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19. The phase 2 study assessed the safety and efficacy of regdanvimab for mild-to-moderate COVID-19 and identified the appropriate dose for further study [19]. Here, we report outcomes from phase 3, up to day 28 in patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19, including those at high risk of progression to severe disease. At the time of this study, patients were primarily infected with the Alpha variant of SARS-CoV-2. Among patients infected with the Omicron variant, most currently available mAb therapies, including regdanvimab, are known to have lost binding affinity for SARS-CoV-2 [12, 13]. This would make such first-generation mAbs useful in the early pandemic but inappropriate in current treatment algorithms; however, some susceptibility to first-generation mAbs may be reemerging [20].

METHODS

Study Design and Oversight

In phase 3 of this phase 2/3, parallel-group, double-blind, multiregional study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04602000; EudraCT: 2020-003369-20), outpatients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 (WHO criteria [3]), including those at high risk of progression, were randomized to regdanvimab or placebo, with standard-of-care management. The protocol and statistical analysis plan for this phase 3 study appear in the Supplementary Data.

Patients

Participants were aged ≥18 years, with COVID-19 confirmed by sponsor-supplied rapid antigen kit or reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), oxygen saturation of >94% on room air, and who did not require supplemental oxygen at study entry. Patients were required to have at least 1 COVID-19–associated symptom with onset ≤7 days and present with at least 1 prespecified symptom (fever, cough, shortness of breath, sore throat, body or muscle pain, fatigue, or headache) ≤48 hours before study drug administration. Individuals who had received a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine were excluded. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Race and ethnicity were collected for evaluation of clinically relevant demographics in this multiregional study. High-risk patients were those at increased risk of progressing to severe COVID-19 and/or hospitalization, defined as meeting at least 1 of the following risk factors: age >50 years, obesity (body mass index [BMI] >30 kg/m2), cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, or immunosuppression.

Study Procedures

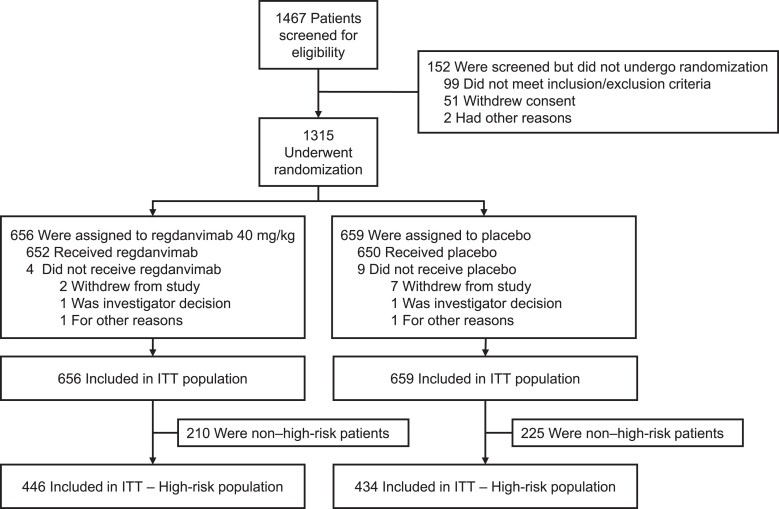

Patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive a single dose of regdanvimab 40 mg/kg or placebo (Figure 1). Regdanvimab and placebo were reconstituted in 250 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride and administered via intravenous infusion over 60 ± 15 minutes.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart. Abbreviation: ITT, intention-to-treat.

All patients were centrally randomized to the study using an interactive web response system, which linked a sequential patient randomization number to the treatment codes. The randomization numbers were blocked, and within each block the prespecified ratio of patients was allocated to each group. Further details can be found in the study protocol (Supplementary Data). Randomization was stratified by age (≥60 vs <60 years), region (United States vs Asia vs European Union vs other), and baseline comorbidities (yes vs no; having ≥1 of cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or pneumonia). Patients received standard-of-care treatment including rehydration therapy, antipyretics, or antitussives per investigator discretion.

Outcomes

The primary efficacy endpoint was proportion of patients with disease progression up to day 28 in high-risk patients. Disease progression was defined as meeting at least 1 of the following COVID-19 events: hospitalization, oxygen therapy, or mortality due to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Key secondary efficacy outcomes included disease progression up to day 28 in all randomized patients and time to clinical recovery up to day 14 in high-risk and all randomized patients. Time to clinical recovery was defined as the time in days since study drug administration and all items on the COVID-19 Symptom Checklist (Supplementary Table 2), as assessed by patient diary, being recorded as absent/mild in intensity for ≥48 hours, or absent if rated mild/absent at baseline. Clinical recovery after day 14 was censored at 14 days for the key secondary endpoint.

Secondary outcomes were efficacy and safety. Exploratory outcomes included virology and serology endpoints (Supplementary Table 3). Patients were considered to possibly have antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) in the case of excessive progression of viral infection–related symptoms (eg, excessive infiltration of inflammatory cells in the lung) or other SARS-CoV-2–related signs and symptoms judged by the investigator to be possible ADE manifestations. The virology endpoint included viral load at days 1 (predose), 3, 7, 10, 14, 21, and 28, and serology included serum SARS-CoV-2 antibody status at days 1, 7, 14, and 28. Viral load and serostatus methodology are described in the Supplementary Data (supplementary methods and statistical analysis plan). Analyses for efficacy endpoints were also performed in non-high-risk patients. Subgroup analysis by COVID-19 viral variant, protocol-specified risk factor, and pneumonia were performed post hoc.

Statistical Analysis

Sample size was estimated using a 2-sided Mantel-Haenszel test in a “tests for two proportions” procedure using PASS software (NCSS LLC, Kaysville, Utah). A sample size of 822 high-risk patients would provide 80% power to detect a 60% reduction in the proportion of high-risk patients with disease progression (requiring hospitalization, oxygen therapy, or experiencing mortality due to SARS-CoV-2 infection) up to day 28 at a 2-sided significance level of .05, assuming 7.1% for placebo and 2.9% for regdanvimab. Approximately 1300 patients were to be enrolled to ensure the required number of high-risk patients.

Primary and binary key secondary endpoints were tested using stratified Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (CMH) at the 2-sided significance level of .05. The difference in proportion between the treatment groups was estimated using CMH weights and was provided along with the 95% stratified Newcombe confidence interval (CI) with CMH weights. Time-to-event key secondary endpoints were tested using stratified log-rank test at the 2-sided significance level of .05. Full details of sample size assumptions and statistical methodologies are included in the Supplementary Data (statistical analysis plan). Further details of statistical analyses for secondary efficacy endpoints are included in Supplementary Table 4.

Kaplan-Meier methodology was used to estimate the median, and Brookmeyer-Crowley methodology (via log-log transformation) was used to construct the 95% CIs for medians. The treatment difference was assessed by the stratified log-rank test presenting P value. Clinical recovery ratio (hazard ratio) between 2 treatment groups and associated 95% CI was estimated using the stratified Cox proportional hazard model.

Stratification factors used for analysis of primary and key secondary endpoints are age (≥60 years vs <60 years), baseline comorbidities (yes vs no), and region (United States vs European Union vs other).

A multiple testing procedure was applied to the primary and key secondary endpoints to control the family-wise error rate at the 2-sided .05 level. All safety analyses were performed for the safety set, defined as all randomly assigned patients who had received a complete or partial dose of study drug. Primary and key secondary endpoints were analyzed in sequence: (1) proportion of patients with clinical symptoms requiring hospitalization, oxygen therapy, or experiencing mortality due to SARS-CoV-2 infection up to day 28 in high-risk patients (primary endpoint); (2) proportion of patients with clinical symptoms requiring hospitalization, oxygen therapy, or experiencing mortality due to SARS-CoV-2 infection up to day 28 in all randomized patients; (3) time to clinical recovery up to day 14 in high-risk patients; (4) time to clinical recovery up to day 14 in all randomized patients.

For viral shedding in nasopharyngeal swab specimens, based on RT-PCR, mean viral load titer was plotted for each time point. Time to negative conversion included patients who had positive results confirmed at baseline (threshold of 2.33 log10 copies/mL) and was analyzed in a descriptive manner with no adjustments for multiple testing.

Patient Consent Statement

The study was conducted according to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and in compliance with the International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines and applicable regulatory requirements. Protocols and all applicable amendments were reviewed and approved by local or national independent ethics committees before study initiation, and the study was monitored by an independent data and safety monitoring board. All patients provided written informed consent and received a stipend, such as transportation expenses or meal vouchers, depending on national policy.

RESULTS

Patients

Participants were enrolled between 18 January 2021 and 24 April 2021. In total, 1315 patients from 58 study centers in 13 countries (Supplementary Data) were randomized to regdanvimab 40 mg/kg (n = 656) or placebo (n = 659) (Figure 1), including 880 high-risk patients (regdanvimab 40 mg/kg, n = 446; placebo, n = 434) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics and Characteristics of All Randomized Patients (Intention-to-Treat [ITT] Set) and High-Risk Patients (ITT High-Risk Set)

| Characteristic | Regdanvimab 40 mg/kg |

Placebo | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| ITT set | |||

| No. of patients | 656 | 659 | 1315 |

| Age, y | |||

| Median (IQR) | 49.0 (38–59) | 47.0 (37–58) | 48.0 (38–59) |

| >50 | 298 (45.4) | 284 (43.1) | 582 (44.3) |

| ≥60 | 151 (23.0) | 146 (22.2) | 297 (22.6) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 309 (47.1) | 332 (50.4) | 641 (48.7) |

| Male | 347 (52.9) | 327 (49.6) | 674 (51.3) |

| Race | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 5 (0.8) | 9 (1.4) | 14 (1.1) |

| Asian | 7 (1.1) | 7 (1.1) | 14 (1.1) |

| Black | 6 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | 7 (0.5) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (0.1) |

| Other | 74 (11.3) | 73 (11.1) | 147 (11.2) |

| White | 563 (85.8) | 569 (86.3) | 1132 (86.1) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 137 (20.9) | 139 (21.1) | 276 (21.0) |

| Non-Hispanic or non-Latino | 515 (78.5) | 513 (77.8) | 1028 (78.2) |

| Unknown | 4 (0.6) | 7 (1.1) | 11 (0.8) |

| Region | |||

| Asia | 6 (0.9) | 6 (0.9) | 12 (0.9) |

| European Union | 522 (79.6) | 523 (79.4) | 1045 (79.5) |

| Other | 79 (12.0) | 79 (12.0) | 158 (12.0) |

| United States | 49 (7.5) | 51 (7.7) | 100 (7.6) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 28.1 (5.1) | 28.0 (5.6) | 28.0 (5.4) |

| Obesitya | 207 (31.6) | 208 (31.6) | 415 (31.6) |

| Baseline comorbidities present | 431 (65.7) | 410 (62.2) | 841 (64.0) |

| Viral load titer | |||

| No. of patients | 648 | 644 | 1292 |

| Median (IQR), log10 copies/mL | 6.155 (4.64–7.25) | 6.255 (4.97–7.24) | 6.190 (4.81–7.24) |

| Serostatusb | |||

| Seropositive | 76 (11.6) | 72 (10.9) | 148 (11.3) |

| Seronegative | 573 (87.3) | 573 (86.9) | 1146 (87.1) |

| Other | 7 (1.1) | 14 (2.1) | 21 (1.6) |

| Days since symptom onset, median (IQR) | 4.0 (3–5) | 4.0 (3–5) | 4.0 (3–5) |

| Disease severity | |||

| Mild | 343 (52.3) | 354 (53.7) | 697 (53.0) |

| Moderate | 308 (47.0) | 302 (45.8) | 610 (46.4) |

| High riskc | 446 (68.0) | 434 (65.9) | 880 (66.9) |

| ITT–high risk set | |||

| No. of patients | 446 | 434 | 880 |

| Age, y | |||

| Median (IQR) | 54.0 (46–63) | 55.0 (45–62) | 54.0 (46–63) |

| >50 | 298 (66.8) | 284 (65.4) | 582 (66.1) |

| ≥60 | 151 (33.9) | 146 (33.6) | 297 (33.8) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 198 (44.4) | 210 (48.4) | 408 (46.4) |

| Male | 248 (55.6) | 224 (51.6) | 472 (53.6) |

| Race | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 4 (0.9) | 5 (1.2) | 9 (1.0) |

| Asian | 4 (0.9) | 3 (0.7) | 7 (0.8) |

| Black | 6 (1.3) | 1 (0.2) | 7 (0.8) |

| Other | 37 (8.3) | 40 (9.2) | 77 (8.8) |

| White | 395 (88.6) | 385 (88.7) | 780 (88.6) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 87 (19.5) | 88 (20.3) | 175 (19.9) |

| Non-Hispanic or non-Latino | 357 (80.0) | 340 (78.3) | 697 (79.2) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.4) | 6 (1.4) | 8 (0.9) |

| Region | |||

| Asia | 4 (0.9) | 3 (0.7) | 7 (0.8) |

| European Union | 365 (81.8) | 353 (81.3) | 718 (81.6) |

| Other | 41 (9.2) | 43 (9.9) | 84 (9.5) |

| United States | 36 (8.1) | 35 (8.1) | 71 (8.1) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 29.8 (5.1) | 29.9 (5.5) | 29.9 (5.3) |

| Obesitya | 207 (46.4) | 208 (47.9) | 415 (47.2) |

| Baseline comorbidities present | 352 (78.9) | 339 (78.1) | 691 (78.5) |

| Viral load titer | |||

| No. of patients | 441 | 424 | 865 |

| Median (IQR), log10 copies/mL | 6.080 (4.61–7.27) | 6.145 (4.95–7.16) | 6.110 (4.80–7.24) |

| Serostatusb | |||

| Seropositive | 57 (12.8) | 50 (11.5) | 107 (12.2) |

| Seronegative | 384 (86.1) | 374 (86.2) | 758 (86.1) |

| Other | 5 (1.1) | 10 (2.3) | 15 (1.7) |

| Days since symptom onset, median (IQR) | 4.0 (3–5) | 4.0 (3–5) | 4.0 (3–5) |

| Disease severity | |||

| Mild | 211 (47.3) | 202 (46.5) | 413 (46.9) |

| Moderate | 230 (51.6) | 231 (53.2) | 461 (52.4) |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; ITT, intention-to-treat; SD, standard deviation; y, year.

Obesity defined as BMI >30 kg/m2.

Patients were considered to be seropositive if they had at least 1 positive viral serology result (SARS-CoV-2 antibody immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin M) at day 1, or seronegative if they had negative results for both viral serology tests at day 1. Patients were considered to have “other” serostatus if serostatus was missing at day 1.

Aged >50 years; BMI >30 kg/m²; cardiovascular disease including hypertension; chronic lung disease including asthma; type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus; chronic kidney disease including those on dialysis; chronic liver disease; immunosuppressed based on investigator’s assessment.

Overall, 55 patients (4.2%) discontinued the study during the treatment period (regdanvimab 40 mg/kg, n = 20 [3.0%]; placebo, n = 35 [5.3%]). Reasons for discontinuation included withdrawal from study (n = 16 and n = 29 in the regdanvimab and placebo arms, respectively), investigator’s decision (n = 2 and n = 2), loss to follow-up (n = 1 and n = 0), death (n = 0 and n = 2), and other reasons (n = 1 and n = 2). Three deaths occurred during the study due to worsening COVID-19. Of these, 2 patients in the placebo group remained in the study until death; 1 patient in the regdanvimab group discontinued the study early and died after the end-of-treatment visit. Of the 3 patients who died due to worsening of COVID-19, all were infected with Alpha variant. During the study, 1 patient in the regdanvimab 40 mg/kg treatment group received the COVID-19 vaccine at 24 days after the study drug administration.

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics were generally well balanced between treatment groups (Table 1). The median age was 48.0 years (interquartile range [IQR], 38–59 years), and 641 patients (48.7%) were female. Patients received regdanvimab or placebo within a median of 4 days after the initial onset of SARS-CoV-2 infection–related symptoms. The median age of high-risk patients was 54.0 years, and 408 high-risk patients (46.4%) were female. Overall, patients in the intention-to-treat (ITT) high-risk set were older and had higher BMI compared with patients in the total ITT set. Concomitant medications are summarized in Supplementary Table 5.

More than 60% of patients in each group were infected with Alpha variant at baseline (371/612 [60.6%] patients in the regdanvimab group and 381/618 [61.7%] patients in the placebo group), and >10% of patients were infected with the ancestral variant (77/612 [12.6%] patients in the regdanvimab group and 71/618 [11.5%] in the placebo group). Only 2 patients (0.3%), both in the placebo group, were infected with the Beta variant, and 7 patients in each group (1.1%) were infected with the Gamma variant.

Efficacy

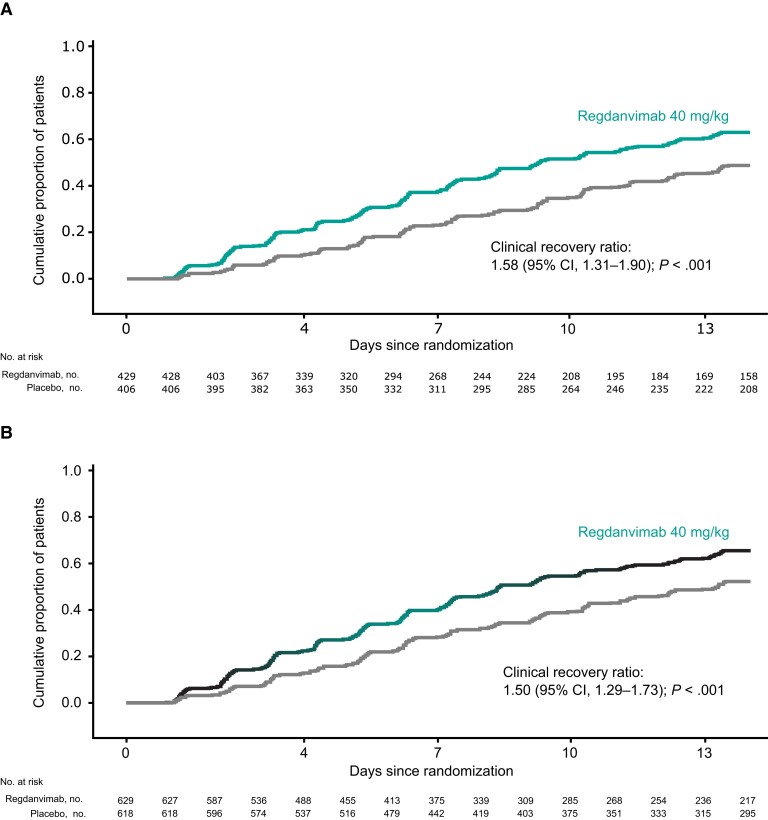

The proportion of high-risk patients (ITT high-risk set) with disease progression up to day 28 was significantly lower in the regdanvimab than placebo group (3.1% [95% CI, 1.9%–5.2%] vs 11.1% [95% CI, 8.4%–14.4%]; estimated treatment difference [ETD], −8.0% [95% CI, −11.7% to −4.5%]; P < .001) (Table 2). High-risk patients treated with regdanvimab had a significantly shorter time to clinical recovery up to day 14 than those receiving placebo (median, 9.27 days [95% CI, 8.27–11.05 days] vs median not reached [95% CI, 12.35 days–not calculable; clinical recovery ratio, 1.58 [95% CI, 1.31–1.90]; P < .001) (Figure 2A, Table 2).

Table 2.

Efficacy Endpoints in All Randomized (ITT Set and ITT High-Risk Set) Patients

| Endpoint | Regdanvimab 40 mg/kg |

Placebo |

|---|---|---|

| Primary endpoint | ||

| Proportion of patients with disease progression up to day 28 in high-risk patientsa | ||

| No./total No. (%) [95% CI] | 14/446 (3.1) [1.9–5.2] | 48/434 (11.1) [8.4–14.4] |

| Difference, %b (95% CI); stratified CMH test P value | −8.0 (−11.7 to −4.5); P < .001 | |

| Key secondary endpoints | ||

| Proportion of patients with disease progression up to day 28 in all randomized patientsc | ||

| No./total No. (%) [95% CI] | 16/656 (2.4) [1.5–3.9] | 53/659 (8.0) [6.2–10.4] |

| Difference, %b (95% CI); stratified CMH test P value | −5.9 (−8.5 to −3.3); P < .001 | |

| Time to clinical recovery up to day 14 | ||

| High-risk patients, No./total No. (%)a | 271/429 (63.2) | 198/406 (48.8) |

| Median (95% CI) time to event, days | 9.27 (8.27–11.05) | NC (12.35–NC) |

| Clinical recovery ratiod (95% CI); stratified log-rank test P value | 1.58 (1.31–1.90); P < .001 | |

| All randomized patients, No./total No. (%)c | 412/629 (65.5) | 323/618 (52.3) |

| Median (95% CI) time to event, days | 8.38 (7.91–9.33) | 13.25 (11.94–NC) |

| Clinical recovery ratiod (95% CI); stratified log-rank test P value | 1.50 (1.29–1.73); P < .001 | |

| Other secondary endpoints in all randomized patients up to day 28c | ||

| Patients requiring hospital admission, No. (%)e | 16 (2.4) | 52 (7.9) |

| Patients requiring supplemental oxygen, No. (%)e | 15 (2.3) | 49 (7.4) |

| Patients requiring mechanical ventilation, No. (%) | 0 | 3 (0.5) |

| Patients requiring rescue therapy, No. (%)e | 37 (5.6) | 84 (12.7) |

| Patients requiring ICU transfer, No. (%)f | 0 | 5 (0.8) |

| All-cause mortality, No. (%) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.3) |

| Median (95% CI) time to clinical recovery, dayse | 8.39 (8.01–9.39) | 13.29 (12.12–15.24) |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CMH, Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel; ICU, intensive care unit; NC, not calculable.

Intention-to-treat (ITT) high-risk set.

Adjusted difference using CMH weights.

ITT set.

Hazard ratio estimated from the stratified Cox proportional hazard model.

P < .001 for difference between regdanvimab and placebo groups.

P < .05 for difference between regdanvimab and placebo groups.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier plot of time to clinical recovery (for ≥48 hours) up to day 14 by treatment group in high-risk patients (ITT high-risk set) (A) and all randomized patients (ITT set) (B). Along with the Kaplan-Meier plot, the clinical recovery ratio between 2 treatment groups and associated 95% CI estimated from the stratified Cox proportional hazard model, and P value from the stratified log-rank test are presented. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ITT, intention-to-treat.

The proportion of all randomized patients (ITT set) with disease progression up to day 28 was also significantly lower (2.4% vs 8.0%; ETD, −5.9%; P < .001) (Table 2), and time to clinical recovery was significantly shorter (median, 8.38 vs 13.25 days; clinical recovery ratio, 1.50; P < .001) (Figure 2B, Table 2) with regdanvimab than with placebo. Clinically significant benefit with regdanvimab compared with placebo observed in high-risk and all randomized patients was maintained in non-high-risk patients (Supplementary Table 6).

In post hoc subgroup analysis by individual risk factors for progressing to severe COVID-19, patients with each risk factor showed consistently lower risk of disease progression in the regdanvimab group compared with placebo (Supplementary Table 7).

Safety

A total of 872 treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were reported in 400 (30.7%) patients, most of which were grade 1 or 2 in intensity (Table 3). There were no TEAEs resulting in permanent study discontinuation. The most frequently reported TEAEs considered related to study drug were hepatic enzyme increases and hypertriglyceridemia with regdanvimab (both reported in 7 [1.1%] patients) and increased alanine aminotransferase levels with placebo (reported in 10 [1.5%] patients).

Table 3.

Safety and Tolerability (Safety Set)

| Adverse Event | Regdanvimab 40 mg/kg (n = 652) |

Placebo (n = 650) | Total (N = 1302) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any TEAE | 198 (30.4) | 202 (31.1) | 400 (30.7) |

| Related to study drug | 44 (6.7) | 46 (7.1) | 90 (6.9) |

| Grade ≥3 TEAEs | 61 (9.4) | 69 (10.6) | 130 (10.0) |

| Related to study drug | 12 (1.8) | 15 (2.3) | 27 (2.1) |

| Any TESAE | 4 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 5 (0.4) |

| Deathsa | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Any TEAE leading to discontinuation | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TEAEs classified as infusion-related reactionsb | 4 (0.6) | 7 (1.1) | 11 (0.8) |

Data are presented as No. of patients (%).

Abbreviations: TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event; TESAE, treatment-emergent serious adverse event.

Reported as TESAEs.

TEAEs classified as infusion-related reactions were considered TEAEs of special interest for this study.

Four patients (0.6%) receiving regdanvimab experienced treatment-emergent serious adverse events (TESAEs): acute myocardial infarction, hospital-acquired pneumonia, infusion-related reaction (urticaria), and pulmonary embolism. One (0.2%) patient in the placebo group experienced a TESAE of bacterial pneumonia (Table 3). No deaths were reported as TESAEs or as outcomes of other TESAEs.

Rates of infusion-related reaction were low for both regdanvimab (0.6%) and placebo (1.1%). At day 1, 10 (1.5%) and 13 (2.0%) patients in the regdanvimab and placebo groups, respectively, tested positive for antidrug antibodies (ADAs). During the study, 10 of 635 (1.6%) patients in the regdanvimab group and 15 of 619 (2.4%) in the placebo group had a positive ADA conversion. There were no cases of ADE.

Virology and Serology

Time to negative conversion in nasopharyngeal swab specimens for the ITT infected set (all randomized patients with confirmed COVID-19 using quantitative RT-PCR at day 1 and who received study drug) was numerically shorter with regdanvimab than placebo up to day 28 (Supplementary Figure 1). The negative conversion ratio up to day 28 was 1.48 (95% CI, 1.30–1.67; P < .001; Supplementary Table 8). A rapid decline in viral load for regdanvimab was shown from day 3 (mean [standard error] changes from baseline in viral load were −1.268 [0.0517] log10 copies/mL and −0.781 [0.0551] log10 copies/mL in the regdanvimab and placebo groups, respectively; treatment difference, −0.48 [95% CI, −.63 to −.33]; P < .001). By day 7, these were −2.770 (0.0652) log10 copies/mL and −2.236 (0.0637) log10 copies/mL, respectively. Greater reductions in viral load were observed with regdanvimab than placebo from baseline out to day 7 (treatment difference, −0.53 [95% CI, −.71 to −.35]; P < .001; Supplementary Figure 2A), after which reductions were comparable in the 2 groups. As to be expected from these results, the proportion of patients providing a positive result for SARS-CoV-2 (threshold of 2.33 log10 copies/mL) over time declined faster in the regdanvimab group than for the placebo group (Supplementary Table 9). Changes over time in the proportion of patients testing positive for immunoglobulin M or immunoglobulin G antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 were broadly comparable with regdanvimab and placebo (Supplementary Table 10).

Efficacy endpoints and viral titers over time among patients with non-wild-type infections are summarized in Supplementary Table 11 and Supplementary Figure 2B. Among patients with the predominant Alpha variant (B.1.1.7), the proportion with disease progression was lower and time to clinical recovery was shorter with regdanvimab compared with placebo. The proportion of patients with disease progression was also numerically lower with regdanvimab than placebo in those infected with the BavPat1/2020 strain (“ancestral” early 2020 strain, containing the D614G secondary spike protein mutation [21]). Only 2 patients were infected with the Beta variant (B.1.351) and 14 with the Gamma variant (P1), of which only 2 patients with the Gamma variant had disease progression. As such, no meaningful analyses were conducted for the Beta and Gamma variants.

DISCUSSION

This phase 3 study, in patients primarily infected with the Alpha variant of SARS-CoV-2, demonstrated that significantly fewer high-risk patients experienced disease progression when treated with regdanvimab than with placebo (P < .001), with a rate reduction of 72%.

The clinical benefits of regdanvimab seen in high-risk patients were also apparent among all randomized patients, with a reduction in the rate of disease progression of 70%. Median times to clinical recovery up to day 14 in high-risk patients and all randomized patients were also shorter for regdanvimab compared with placebo.

Post hoc analysis indicated a consistent reduction in the rate of disease progression among patients older than 50 years with obesity, cardiovascular disease, or diabetes mellitus. Those risk factors are consistent with results from other studies [22–26].

We observed an overall higher rate of disease progression in the current study compared with that in similar trials examining the clinical benefit of the neutralizing antibody treatments bamlanivimab plus etesevimab and casirivimab plus imdevimab for SARS-CoV-2 infection [27, 28]. Due to the timing of the study periods for those studies (bamlanivimab plus etesevimab: September 2020 to January 2021; casirivimab plus imdevimab: June 2020 to September 2020), it is highly likely that wild-type SARS-CoV-2 was dominant at the time of patients’ enrollment to those studies. In our study, the more contagious Alpha variant was the currently dominant strain [29], and this group did account for a higher disease progression rate compared with other variants.

A greater reduction in viral load up to day 7 was also observed with regdanvimab compared with placebo, suggesting that regdanvimab is effective in achieving an early reduction in viral burden; these differences were apparent between groups up to 10 days after treatment administration. While 12% of patients receiving regdanvimab remained PCR positive at day 28, vs with 22% of patients receiving placebo, detection of leftover virus particles at this time point is not unusual. In a population-based prospective cohort study, viral clearance was achieved in only 60.6% (704/1162) of patients with COVID-19, with a median time to clearance of 30 days from diagnosis (IQR, 23–40 days) and 36 days from symptom onset [30].

This study included patients with onset of symptoms ≤7 days prior to the administration of study drug. Symptoms may appear 2–14 days after exposure to the virus, and it can take 1–3 weeks for the immune system to make antibodies after infection. Overall, 11.3% of patients in this study were seropositive at day 1; this is low compared with other recent phase 3 trials of mAbs in patients with COVID-19, which have shown seropositivity between 21.9% and 23.8% [28].

Based on the findings of this study, regdanvimab showed favorable effectiveness compared with placebo, which is in line with results from trials of other antibody therapies showing around a 70% reduction in the risk of hospitalization or death [27, 28]. While the overall rate of disease worsening is higher in our study, the timing of our study meant that the majority of patients presented with the more contagious Alpha variant, compared with the likely inclusion of wild-type virus in other similar studies. This is borne out in “real-world” observations of regdanvimab conducted at a similar time (after the introduction of regdanvimab in to clinical practice through emergency use authorization granted by the South Korean MFDS in February 2021), which show comparable levels of disease progression [31].

SARS-CoV-2 continues to evolve with the emergence of viral variants. The Alpha (B.1.1.7) variant was the most frequent non-wild-type strain in our study. Regdanvimab was effective against the Alpha variant, reducing the proportion of patients with disease progression by 78% compared with placebo. Time to clinical recovery and viral titers were also reduced. Regdanvimab has shown reduced in vitro neutralizing potency against the Beta (B.1.351) variant, although in vivo antiviral activity was still retained in animal modeling [32]. Similarly, in vitro studies have shown that regdanvimab has neutralizing potency against the Delta, Epsilon, and Kappa variants despite being less active against these variants vs the wild-type virus [33]. The currently predominant Omicron variant seems to induce a less severe disease course and mAbs, including regdanvimab, have demonstrated reduced efficacy against the Omicron variant in vitro [10–12, 14]. However, severe COVID-19 due to Omicron is still a clinical reality for high-risk patients, particularly those who have not experienced a prior episode of COVID-19, or who have not been vaccinated against COVID-19, or have had only a nonboosted primary course of vaccination in late 2020 and early 2021. Loss of efficacy means that currently available mAb therapies, including regdanvimab, may no longer be suitable in current treatment algorithms for patients infected with the Omicron variant, contrasting with their effectiveness during the early pandemic. Although it is impossible to predict the characteristics of future variants, there is some evidence suggesting that among the WHO monitored variants of concern, the novel BA.2 subvariant, BA.2.75, may have regained susceptibility to regdanvimab and other first-generation mAbs [20].

Regdanvimab showed no apparent clinically significant safety issues and there were no deaths due to TEAEs. Most adverse events were mild in severity and did not require intervention. Rates of IRRs with regdanvimab were low and comparable with placebo and there were no reports of ADE.

Our study has some limitations. Certain patient subgroups known to be at higher risk of complications and COVID-19–related deaths, including Black/African American or Hispanic [34–36] patients, were underrepresented (0.5% and 21% of the study population, respectively). Data were not available on any drug interactions with regdanvimab, subsequent vaccination response, or in patients with COVID-19 despite prior vaccination. Also, mutational studies that may help to identify the development of treatment-resistant variants were not performed. Finally, patient recruitment for this study began before June 2021, when the Delta variant became widespread globally, and before the emergence of the most recent Omicron variant [29]. It is becoming apparent that current antibody therapies, including regdanvimab, may be less effective against the Omicron variant [12, 13]. Consideration of the currently predominant and other variants of concern will be crucial in future research, alongside monitoring emerging viral variants for potential reemergence of susceptibility [20].

Viral mutations may reduce the effectiveness of vaccines, antivirals, or antibody therapeutics. However, antibody therapy can be rapidly deployed, and thus could have an important role in limiting the occurrence of severe disease [37, 38]. Also, given the capacity limitations on mAb production and the unknowns of dealing with a new virus, it is important to have access to a range of mAb preparations to ensure availability for treating high-risk patients and limiting hospital admissions.

In conclusion, disease progression and clinical recovery time were significantly reduced with regdanvimab vs placebo in patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 who were at high risk of progression. Further to the emergency use authorization and subsequent approval of regdanvimab by the South Korean MFDS in September 2021 and the CHMP recommendation made in November 2021, regdanvimab has been administered to >40 000 patients [39], and these data provide additional evidence supporting the use of regdanvimab as a treatment for COVID-19. Efficacy and safety of regdanvimab were demonstrated at the beginning phase of the COVID-19 pandemic when the Alpha variant, with higher disease severity than the later Omicron variant, was predominant in circulation. Although such “first-generation” mAb therapies are no longer be suitable for patients with the Omicron variant, the emergence of new Omicron variants that may show renewed susceptibility to first-generation mAbs [20] suggests that further study is needed as SARS-CoV-2 continues to evolve.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Jin Yong Kim, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Incheon Medical Center, Incheon, Republic of Korea.

Oana Săndulescu, National Institute for Infectious Diseases “Prof Dr Matei Balş,” Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania.

Liliana-Lucia Preotescu, National Institute for Infectious Diseases “Prof Dr Matei Balş,” Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania.

Norma E Rivera-Martínez, Oaxaca Site Management Organization, Oaxaca, Mexico.

Marta Dobryanska, City Clinical Hospital 12, Kyiv, Ukraine; ARENSIA Exploratory Medicine, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Victoria Birlutiu, Faculty of Medicine, Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu, Emergency Clinical County Hospital, Sibiu, Romania.

Egidia G Miftode, Clinical Hospital of Infectious Diseases “Sfanta Parascheva,” University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Gr. T. Popa,” Iasi, Romania.

Natalia Gaibu, Institutul Oncologic din Republica Moldova Republican Clinical Hospital “T. Moşneaga,” ARENSIA Exploratory Medicine, Chisinau, Moldova.

Olga Caliman-Sturdza, Stefan cel Mare University, Suceava, Romania.

Simin-Aysel Florescu, Dr Victor Babes Clinical Hospital for Tropical and Infectious Diseases, Bucharest, Romania.

Hye Jin Shi, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Gil Medical Center, Gachon University College of Medicine, Incheon, Republic of Korea.

Anca Streinu-Cercel, National Institute for Infectious Diseases “Prof Dr Matei Balş,” Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania.

Adrian Streinu-Cercel, National Institute for Infectious Diseases “Prof Dr Matei Balş,” Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania.

Sang Joon Lee, Celltrion, Inc, Incheon, Republic of Korea.

Sung Hyun Kim, Celltrion, Inc, Incheon, Republic of Korea.

Ilsung Chang, Celltrion, Inc, Incheon, Republic of Korea.

Yun Ju Bae, Celltrion, Inc, Incheon, Republic of Korea.

Jee Hye Suh, Celltrion, Inc, Incheon, Republic of Korea.

Da Rae Chung, Celltrion, Inc, Incheon, Republic of Korea.

Sun Jung Kim, Celltrion, Inc, Incheon, Republic of Korea.

Mi Rim Kim, Celltrion, Inc, Incheon, Republic of Korea.

Seul Gi Lee, Celltrion, Inc, Incheon, Republic of Korea.

Gahee Park, Celltrion, Inc, Incheon, Republic of Korea.

Joong Sik Eom, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Gil Medical Center, Gachon University College of Medicine, Incheon, Republic of Korea.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Author contributions. S. H. K. and I. C. had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. J. Y. K., O. S., L.-L. P., N. E. R.-M., M. D., V. B., E. G. M., N. G., O. C.-S., S.-A. F., H. J. S., An. S.-C., Ad. S.-C., and J. S. E. collected the data. S. J. L., S. H. K., I. C., Y. J. B., J. H. S., D. R. C., S. J. K., M. R. K., S. G. L., and G. P. analyzed the data. All authors participated in study design and in the preparation, critical review, and final approval of the article for publication.

Acknowledgments. We thank all patients and investigators involved in the study. Medical writing support (including development of a draft outline and subsequent drafts in consultation with the authors, assembling tables and figures, collating author comments, copyediting, fact checking, and referencing) was provided by Duncan Campbell, PhD, CMPP, at Aspire Scientific (Bollington, UK), and funded by Celltrion, Inc (Incheon, Republic of Korea).

Data availability. The protocol and statistical analysis plan are available in the Supplementary Data. Individual patient-level data are not currently available for sharing.

Financial support. This work was funded by Celltrion and supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, South Korea (grant number HQ21C0073).

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Pollard CA, Morran MP, Nestor-Kalinoski AL. The COVID-19 pandemic: a global health crisis. Physiol Genomics 2020; 52:549–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization . Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed 13 June 2022.

- 3. World Health Organization . Living guidance for clinical management of COVID-19. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-clinical-2021-2. Accessed 3 May 2022. [PubMed]

- 4. Weinreich DM, Sivapalasingam S, Norton T, et al. REGN-COV2, a neutralizing antibody cocktail, in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:238–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen P, Nirula A, Heller B, et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody LY-CoV555 in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:229–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gottlieb RL, Nirula A, Chen P, et al. Effect of bamlanivimab as monotherapy or in combination with etesevimab on viral load in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021; 325:632–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ferguson N, Ghani A, Hinsley W, Volz E. Hospitalisation risk for Omicron cases in England. https://www.imperial.ac.uk/mrc-global-infectious-disease-analysis/covid-19/report-50-severity-omicron/. Accessed 3 May 2022.

- 8. Sheikh A, Kerr S, Woolhouse M, McMenamin J, Robertson C. Severity of Omicron variant of concern and effectiveness of vaccine boosters against symptomatic disease in Scotland (EAVE II): a national cohort study with nested test-negative design. Lancet Infect Dis 2022; 22:959–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wolter N, Jassat W, Walaza S, et al. Early assessment of the clinical severity of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in South Africa: a data linkage study. Lancet 2022; 399:437–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Auvigne V, Vaux S, Strat YL, et al. Severe hospital events following symptomatic infection with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron and Delta variants in France, December 2021–January 2022: a retrospective, population-based, matched cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 2022; 48:101455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davies MA, Kassanjee R, Rousseau P, et al. Outcomes of laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in the Omicron-driven fourth wave compared with previous waves in the Western Cape Province, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2022; 27:564–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Planas D, Saunders N, Maes P, et al. Considerable escape of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron to antibody neutralization. Nature 2022; 602:671–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ju B, Zheng Q, Guo H, et al. Molecular basis of broad neutralization against SARS-CoV-2 variants including Omicron by a human antibody. bioRxiv [Preprint]. Posted online 20 January 2022. doi: 10.1101/2022.01.19.476892. [DOI]

- 14. Schulz SR, Hoffmann M, Roth E, et al. Augmented neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant by boost vaccination and monoclonal antibodies. Eur J Immunol 2022; 52:970–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim C, Ryu DK, Lee J, et al. A therapeutic neutralizing antibody targeting receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Nat Commun 2021; 12:288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Business Wire . Celltrion’s monoclonal antibody treatment for COVID-19, regdanvimab (CT-P59) becomes the first authorized COVID-19 treatment approved from the Korean Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS). https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20210918005026/en/%C2%A0Celltrion%E2%80%99s-monoclonal-antibody-treatment-for-COVID-19-regdanvimab-CT-P59-becomes-the-first-authorized-COVID-19-treatment-approved-from-the-Korean-Ministry-of-Food-and-Drug-Safety-MFDS. Accessed 3 May 2021.

- 17. European Medicines Agency . Regkirona (regdanvimab). https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/regkirona. Accessed 3 May 2022.

- 18. Kim JY, Jang YR, Hong JH, et al. Safety, virologic efficacy, and pharmacokinetics of CT-P59, a neutralizing monoclonal antibody against SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding protein: two randomized, placebo-controlled, phase I studies in healthy individuals and patients with mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin Ther 2021; 43:1706–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Streinu-Cercel A, Săndulescu O, Preotescu L-L, et al. Efficacy and safety of regdanvimab (CT-P59): a phase 2/3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in outpatients with mild-to-moderate coronavirus disease 2019. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022; 9:ofac053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yamasoba D, Kimura I, Kosugi Y, et al. Neutralization sensitivity of Omicron BA.2.75 to therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. bioRxiv [Preprint]. Posted online 15 July 2022. doi: 10.1101/2022.07.14.500041. [DOI]

- 21. Hoffmann D, Corleis B, Rauch S, et al. CVnCov and CV2CoV protect human ACE2 transgenic mice from ancestral B BavPat1 and emerging B.1.351 SARS-CoV-2. Nat Commun 2021; 12:4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mohammad S, Aziz R, Al Mahri S, et al. Obesity and COVID-19: what makes obese host so vulnerable? Immun Ageing 2021; 18:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhou Y, Chi J, Lv W, Wang Y. Obesity and diabetes as high-risk factors for severe coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19). Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2021; 37:e3377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Varikasuvu SR, Dutt N, Thangappazham B, Varshney S. Diabetes and COVID-19: a pooled analysis related to disease severity and mortality. Prim Care Diabetes 2021; 15:24–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Naz NA, Patel J, Al Rifai M, Turlington JS, Shapiro MD. American College of Cardiology. Mitigating ASCVD risk among those previously infected with COVID-19. https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2021/06/01/12/48/mitigating-ascvd-risk-among-those-previously-infected-with-covid-19. Accessed 3 May 2021.

- 26. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . COVID-19 risk factors and risk groups. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19/latest-evidence/risk-factors-risk-groups. Accessed 3 May 2021.

- 27. Dougan M, Nirula A, Azizad M, et al. Bamlanivimab plus etesevimab in mild or moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:1382–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Weinreich DM, Sivapalasingam S, Norton T, et al. REGEN-COV antibody combination and outcomes in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:e81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. GISAID . Tracking of variants: VOC Delta, relative variant genome frequency per region. https://www.gisaid.org/hcov19-variants/. Accessed 9 September 2021.

- 30. Mancuso P, Venturelli F, Vicentini M, et al. Temporal profile and determinants of viral shedding and of viral clearance confirmation on nasopharyngeal swabs from SARS-CoV-2-positive subjects: a population-based prospective cohort study in Reggio Emilia, Italy. BMJ Open 2020; 10:e040380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee JY, Lee JY, Ko J-H, et al. Effectiveness of regdanvimab treatment in high-risk COVID-19 patients to prevent progression to severe disease. Front Immunol 2021; 12:772320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ryu D-K, Song R, Kim M, et al. Therapeutic effect of CT-P59 against SARS-CoV-2 South African variant. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2021; 566:135–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ryu DK, Kang B, Noh H, et al. The in vitro and in vivo efficacy of CT-P59 against Gamma, Delta and its associated variants of SARS-CoV-2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2021; 578:91–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Perkin MR, Heap S, Crerar-Gilbert A, et al. Deaths in people from Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities from both COVID-19 and non-COVID causes in the first weeks of the pandemic in London: a hospital case note review. BMJ Open 2020; 10:e040638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wiley Z, Kubes JN, Cobb J, et al. Age, comorbid conditions, and racial disparities in COVID-19 outcomes. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2022; 9:117–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rodriguez-Diaz CE, Guilamo-Ramos V, Mena L, et al. Risk for COVID-19 infection and death among Latinos in the United States: examining heterogeneity in transmission dynamics. Ann Epidemiol 2020; 52:46–53.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Taylor PC, Adams AC, Hufford MM, de la Torre I, Winthrop K, Gottlieb RL. Neutralizing monoclonal antibodies for treatment of COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol 2021; 21:382–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Marston HD, Paules CI, Fauci AS. Monoclonal antibodies for emerging infectious diseases—borrowing from history. N Engl J Med 2018; 378:1469–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ministry of Health and Welfare . Coronavirus-19 (COVID-19): Covid-19 vaccination and domestic outbreaks (2.4.) [in Korean]. http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/tcmBoardView.do?brdId=3&brdGubun=31&dataGubun=&ncvContSeq=6352&contSeq=6352&board_id=312&gubun=ALL. Accessed 3 May 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.