Abstract

Background

The burden and duration of persistent symptoms after nonsevere coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) remains uncertain. This study aimed to assess postinfection symptom trajectories in home-isolated COVID-19 cases compared with age- and time- matched seronegative controls, and investigate immunological correlates of long COVID.

Methods

A prospective case-control study included home-isolated COVID-19 cases between February 28 and April 4, 2020, and followed for 12 (n = 233) to 18 (n = 149) months, and 189 age-matched severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-naive controls. We collected clinical data at baseline, 6, 12, and 18 months postinfection, and blood samples at 2, 4, 6, and 12 months for analysis of SARS-CoV-2-specific humoral and cellular responses.

Results

Overall, 46% (108/233) had persisting symptoms 12 months after COVID-19. Compared with controls, adult cases had a high risk of fatigue (27% excess risk, sex, and comorbidity adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 5.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.27–10.5), memory problems (21% excess risk; aOR 7.42; CI, 3.51–15.67), concentration problems (20% excess risk; aOR 8.88; 95% CI, 3.88–20.35), and dyspnea (10% excess risk; aOR 2.66; 95% CI, 1.22–5.79). The prevalence of memory problems increased overall from 6 to 18 months (excess risk 11.5%; 95% CI, 1.5–21.5; P = .024) and among women (excess risk 18.7%; 95% CI, 4.4–32.9; P = .010). Longitudinal spike immunoglobulin G was significantly associated with dyspnea at 12 months. The spike-specific clonal CD4+ T-cell receptor β depth was significantly associated with both dyspnea and number of symptoms at 12 months.

Conclusions

This study documents a high burden of persisting symptoms after mild COVID-19 and suggests that infection induced SARS-CoV-2-specific immune responses may influence long-term symptoms.

Keywords: long COVID, PASC, SARS CoV-2, antibodies, T-cells

A significant burden of long COVID symptoms were observed 6 to 18 months postinfection in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-positive cases, compared with SARS-CoV-2-naive controls. Associations between SARS-CoV-2-specific humoral and cellular immune responses and long COVID symptoms were identified.

Prolonged complications after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) are a major health concern in the ongoing pandemic. New and persisting symptoms beyond 3 months after acute COVID-19, without other medical explanations [1–4], are referred to as long COVID. Long COVID significantly overlaps with the postintensive care syndrome observed in survivors of severe COVID-19 [5, 6]. Although the burden of long COVID is greater after severe disease, long COVID can also develop after mild illness, with 39% to 77% of hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients reporting persisting symptoms 12 months after COVID-19 [7–13]. In 2-year longitudinal follow-up studies, the symptom burden decreased with time, but residual symptoms persisted in 55% of hospitalized patients [14] and 38% of nonhospitalized patients [15]. Frequent, persisting symptoms are fatigue, dyspnea, neurocognitive problems, and mental health problems [16], but because of methodological heterogeneity, uncertainty remains about the true burden. Symptoms of long COVID may be wrongly attributed to infection as only a few studies included controls [14, 17, 18], making it difficult to identify any confounders [10, 15]. Online surveys in which participants are included on their own initiative likely overestimate the symptom burden of long COVID [19]. In contrast, registry data may fail to pick up on symptoms that do not result in contact with health service and may consequently underestimate symptom prevalence [20, 21]. Previously, we reported higher severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike-specific antibodies associated with long COVID in a prospective cohort of home-isolated patients at 6 months [22]. Others have found potent antibody responses, aberrant T-cellular responses and preexisting illness are associated with symptom sequelae [22–26]. Knowledge of the pathophysiology of long COVID is still evolving. In this study, we aimed to investigate symptom trajectories up to 18 months after infection, assess the excess risk of symptoms in COVID-19 cases compared with age- and time-matched SARS-CoV-2 naive controls, and explore the immunological and clinical correlates of long COVID.

METHODS

Study Population

Cases included home-isolated patients with reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, tested at the city’s centralized testing facility (Bergen Municipality Emergency Clinic) between 28 February 2020 and 4 April 2020. Household contacts of confirmed cases were invited to participate in a study of household attack rates during the same period [27], and those testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 spike antibodies within 2 months after recruitment were included as cases in the current study. One patient who was hospitalized in the weeks after acute infection was excluded from this cohort. All cases were assessed by clinical follow-up for 12 months (n = 233), and a subgroup of adult cases agreeing to further follow-up (n = 149) were followed for 18 months.

A control group was assessed at the clinic and recruited in 2 ways. First, household contacts without symptoms, who did not seroconvert, and had no history of RT-PCR positivity, were included, and considered socioeconomically matched to the cases. Second, age-matched controls were recruited between January and March 2021 from the population of individuals who were prioritized for vaccination because of either age, comorbidity, or occupation. All controls were seronegative at the time of symptom assessment. Hence, the seasonal timing of assessment and the degree of national and local restrictions were similar for cases at the 12-month follow-up and controls. The matching was therefore primarily chosen for comparison to the 12-month patient data.

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee of Western Norway (#118664 and #218629). All eligible individuals received both oral and written information about the study protocol and provided written informed consent on inclusion. For children <16 years, parents provided consent.

Clinical Data Collection

Participant data were entered in electronic case report forms (using the Research Electronic Data Capture database (REDCap, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee) software and subsequently stored on a secure research server.

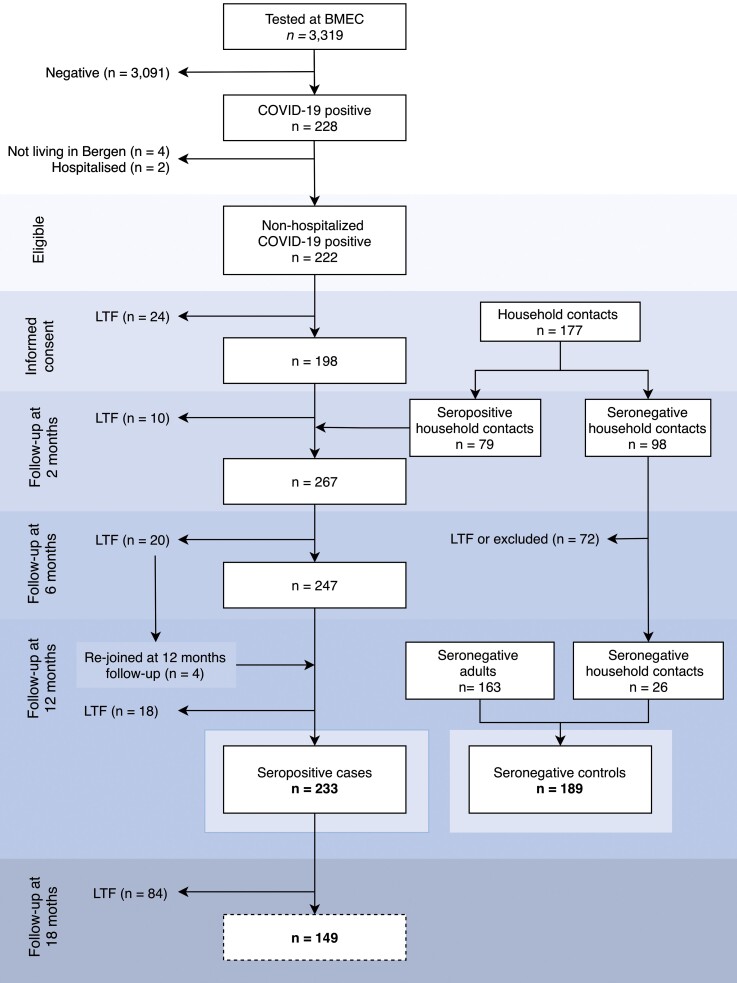

All cases recruited at Bergen Municipality Emergency Clinic were followed up for 12 months (interquartile range, 11.5–12.4 months) with systematic interviews at baseline, 2, 6, and 12 months (Supplementary Methods), and blood samples at 2, 4, 6, and 12 months. A total of 149 cases had an additional follow-up at 18 months (Figure 1). All subjects provided information on demographics and comorbidities, prescription drug use, and COVID-19-related symptoms at baseline and follow-up visits. Comorbidities recorded were asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, chronic heart disease, rheumatic disease, diabetes, cancer, neurological disease, immunosuppressive conditions, or other severe or chronic disorders.

Figure 1.

Study population. Inclusion of SARS-CoV-2 cases (left) and control group (right). Eligible participants tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection by RT-PCR at Bergen Municipality Emergency Clinic (BMEC) were recruited between February 28 and April 4, 2020. Only 1 case (the first most symptomatic) from each household was tested because of the limited testing capacity; thus, individuals living with COVID-19-positive study participants were included as household contacts. If household contact had positive SARS-CoV-2 serology (RBD and spike-IgG ELISA) within 2 months after recruitment, they were registered as cases. Seronegative household contact without a history of COVID-19 symptoms were included as controls. Additional controls were recruited amongst individuals who were prioritized for vaccination, either because of their age, comorbidity, or occupation. At the time of symptom recording, all controls were confirmed seronegative. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; LTF,lost to follow-up; RBD, receptor-binding domain; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

The baseline symptom questionnaire was limited to fatigue, headache, fever, myalgia, and dyspnea. At 6-, 12-, and 18-month follow-up of cases, a dichotomized yes/no questionnaire was conducted for the following persistent symptoms: dyspnea, sleep problems, headache, dizziness, tingling, palpitations, gastrointestinal problems, or low-grade fever. A general questionnaire with dichotomized answers was used to assess fatigue, concentration, and memory problems in children ≤15 years old. For adult cases, the validated 11-item Chalder Fatigue Scale (CFS) was used. This CFS questionnaire identifies symptoms associated with both physical and mental fatigue, with graded responses that can be reported according to a Likert scale (0, 1, 2, 3) or as a bimodal score (0,0,1,1) [28]. The prevalence of fatigue, impaired concentration, and memory problems was derived from the corresponding bimodal score of the CFS item 1, 8, and 11, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). We used a definition of long COVID as persistent or new onset symptoms at 3 months after COVID-19 [4].

Controls provided blood samples and replied to a survey including demographic and clinical information on comorbidities, assessment of dyspnea, and the 11-item CFS concomitantly with the 12-month follow-up of cases.

Blood Sampling

Sera were stored at –80°C and heat-inactivated for 1 hour at 56°C after thawing before use.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

A 2-step enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for detection of immunoglobulin G (IgG) was used, first by antibody screening for the Wuhan receptor-binding domain (RBD), followed by endpoint Wuhan spike ELISA, as previously described [27, 29] (Supplementary Methods).

Microneutralization Assay

The microneutralization assay was performed using a local SARS-CoV-2 isolate from March 2020, as previously described [27, 29] (Supplementary Methods).

Identification of SARS-CoV-2-associated T-cell Receptor β (TCRβ) Sequences

Genomic DNA was extracted from EDTA blood using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood Extraction Kit (QIAGEN, Germantown, MD) and amplified in a bias-controlled multiplex PCR, followed by high-throughput sequencing. SARS-CoV-2-associated CDR3 regions of TCRβ chains were sequenced using the ImmunoSEQ Assay T-MAP COVID platform (Adaptive Biotechnologies, Seattle, WA) as previously described [30]. The clonal breadth was defined as the relative number of SARS-CoV-2-associated TCR clonal lineages in a repertoire, and the relative expansion of SARS-CoV-2-associated TCR clonotypes was defined as the clonal depth.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis and visualization were performed in R version 4.2.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) (Figures 2, 3, and 4) and IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 (New York, USA) (Table 1 and Supplementary Tables 1–4). Age-stratified analysis was performed using 15-year intervals to provide sufficient group sizes. Pearson χ2 test and Fisher exact test were used to compare proportions. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables between 2 groups. Confidence intervals (CIs) and P values for risk differences were calculated using the fmsb package in R. Correlations between antibody titers and T-cell breadth and depth were assessed by Spearman rho. Multivariate binomial logistic regression was used for analyses of binary outcome variables and negative binomial regression was used for the count outcome “number of symptoms.” Regression models are presented with adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% CI or rate ratio with 95% CI or standard error (SE) and P values. Scaling of TCR breadth was applied because of significant difference in the range between the depth and the breadth of the TCR variables. Microneutralization and IgG antibody titers were log(10)-transformed to adjust for nonnormality. Generalized estimating equations were used to compare longitudinal spike IgG antibody measurements between 2 groups (geepack package; v 1.3.3 in R).

Figure 2.

Age-stratified symptom prevalence at 12 months after infection. Bar plot representing the proportion of cases reporting 11 key symptoms at 12 months’ follow-up. The cases reported a mean of 1.4 symptoms overall. The age group 0 to 15 years old (n = 13) is not shown because of absence of symptoms. The light gray area in the bar charts represents the overall proportion with any of the 11 symptoms in the current age group. The colored areas represent the proportion with the specified symptoms.

Figure 3.

Longitudinal symptom changes up to 18 months after infection. Dumbbell charts present longitudinal data on development of 11 specified symptoms in a subcohort of patients followed for 18 months (n = 148, 1 patient was excluded because of missing data on all symptoms at 6 months). (Left panel) The overall symptom change from 6 to 12 months, (Middle panel) the overall symptom change from 6 to 18 months, and (Right panel) the symptom change in men (n = 73) and women (n = 75) from 6 to 18 months.

Figure 4.

Kinetics of the spike IgG antibody response in relation to symptoms at 6 and 12 months. The relationship between longitudinal antibody titers and (A) persistent dyspnea versus no dyspnea, (B) 3 or more symptoms at 12 months vs no symptoms, and (C) persistent fatigue vs no fatigue. The generalized estimating equation (GEE) coefficients with 95% confidence intervals (CI) are adjusted for age, sex, comorbidity, and time of measurement. All cases who had been vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 during the follow-up period (n = 20) were excluded from the analysis of immunological parameters at 12 months. IgG, immunoglobulin G; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Table 1.

Risk of Frequently Reported Symptoms at 12 Months in Age-stratified COVID-19 Cases Aged ≥16 Years Compared With Noninfected Controls

| All (16–81 y) | 16–30 y | 31–45 y | 46–60 y | 61–81 y | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case % (n) |

Control % (n) |

aORa (95% CI) |

Crude risk difference 95% CI |

Case % (n) |

Control % (n) |

aORa (95% CI) |

Case % (n) |

Control % (n) |

aORa (95% CI) |

Case % (n) |

Control % (n) |

aORa (95% CI) |

Case % (n) |

Control % (n) |

aORa (95% CI) |

|

| n = 220 | n = 182 | P value | P value | n = 55 | n = 38 | P value | n = 56 | n = 78 | P value | n = 68 | n = 43 | P value | n = 41 | n = 23 | P value | |

| Fatigue | 37% (81) |

9% (17) |

5.86

(3.3–10.5) <.001 |

27%

(20-,35) <.001 |

26% (14) |

13% (5) |

2.95 (.9–9.5) .070 |

39% (22) |

10% (8) |

5.67

(2.3–14.2) <.001 |

41% (28) |

2% (1) |

32.98

(4.2–260.8) .001 |

42% (17) |

13% (3) |

4.64

(1.1–19.1) .033 |

| Memory problems | 26% (57) |

5% (9) |

7.42

(3.5–15.7) <.001 |

21%

(14, 28) <.001 |

18% (10) |

3% (1) |

12.97

(1.5–110.0) .019 |

25% (14) |

8% (6) |

4.62

(1.6–13.2) .005 |

32% (22) |

0% (0) |

NA | 27% (11) |

9% (2) |

3.42 (.7–17.3).137 |

| Impaired concentration | 24% (53) |

4% (7) |

8.88

(3.9–20.4) <.001 |

20%

(14, 27) <.001 |

26% (14) |

5% (2) |

7.03

(1.4–34.6) .016 |

23% (13) |

3% (2) |

12.66

(2.7–59.8) .001 |

29% (20) |

0% (0) |

NA | 15% (6) |

14% (3) |

1.15 (.3–5.3).860 |

| Dyspnea | 15% (34) |

5% (9) |

2.66

(1.2–5.8) .014 |

11%

(5.16) <.001 |

13% (7) |

0% (0) |

NA | 14% (8) |

5% (4) |

2.61 (.72–9.5) .144 |

18% (12) |

4% (2) |

3.62 (0.7–18.0) 0.115 |

17% (7) |

14% (3) |

1.19 (.3–5.4) .827 |

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; NA = not applicable.

OR,sex and comorbidity adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Comorbidity,includes the presence of any comorbidity. Corresponding 2-sided P values <.05 are shown in bold.

RESULTS

Study Population

A population of 233 home-isolated COVID-19 cases were followed for 12 months, and 189 controls were assessed at the time when cases had their 12 months follow-up. Cases and controls had similar median age (44 vs 41 years, P = .576) and 16/233 cases and 7/189 controls were ≤18 years. There were fewer females among cases (53% vs 66%, P = .010). Overall, more cases reported comorbidities than controls (53% vs 42%, P = .026), most frequently chronic lung disease (12% vs 8%, P = .168), hypertension (11% vs 7%, P = .241), rheumatic disease (7% vs 3% P = .047), and chronic heart disease (6% vs 6%, P = .915) (Supplementary Table 1).

Symptom Burden in Cases at 12-month Follow-up Compared With Controls

Compared with controls, adult cases had excess risk, and higher gender and comorbidity adjusted odds of fatigue (37% vs 9%; aOR 5.86; 95% CI, 3.27–10.5; P < .001), impaired concentration (24% vs 4%; aOR, 8.88; 95% CI, 3.88–20.35; P < .001), memory problems (26% vs 5%; aOR, 7.42; 95% CI, 3.51–15.67, P < .001), and dyspnea (15% vs 5%; aOR 2.66; 95% CI, 1.22–5.79; P = .014). Children 0 to 15 years old reported no symptoms at 12 months’ follow-up in either cases or controls. Cases aged 16 to 30, 31 to 45, and 46 to 60 years had the highest risk of memory problems and impaired concentration (P < .05) (Table 1). Fatigue, on the other hand, was more frequently reported by cases aged 46 to 60 years (41% vs 2% in controls, P < .001) and 61 and 81 years (42% vs 13% in controls, P = .033). Age-stratified prevalence of 11 symptoms is presented in Figure 2.

Longitudinal Symptom Development

We assessed the trajectories of 11 symptoms in a subgroup of 149 cases followed for 18 months (Figure 3). The prevalence of reported memory difficulties increased overall from 6 to 18 months of follow-up, with an excess risk of 11.5% (95% CI, 1.5–21.5; P = .024), the excess risk was significant among women (excess risk 18.7%; 95% CI, 4.4–32.9; P = .010), but not among males (9.6; 95% CI, –3.6 to 22.8; P = .154). The risk difference from 6 to 18 months for other specific symptoms and symptoms overall was not statistically significant (Figure 3).

Compared with males, women had excess risk of having symptoms overall at 18 months (17.5%; 95% CI, 1.6–33.3; P = .030; Figure 4B) and at 12 months’ follow-up (20.2%; 95% CI, 4.5–36.0; P = .012), but not at 6 months (6.8%; 95% CI, –9.3 to 22.8; P = .41). There was no statistically significant risk difference between the sexes for each specific symptom at 18 months of follow-up (Figure 4B), although women had more memory problem at 12 months and scored higher on Chalder fatigue score at 6 and 12 months (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Assessing different intensities according to the Likert scale (“more than usual” vs “much more than usual”), we found that cases had excess risk of fatigue, memory problems, impaired concentration, and dyspnea compared with controls at all 3 time points (Table 2). However, the proportion with severe symptoms was low, and there was no significantly increased risk of severe cognitive symptoms at 12 and 18 months.

Table 2.

Longitudinal Data on Crude Risk Difference of Long COVID Symptomsa in 149 Cases Aged ≥16 years Who Came for 6-, 12-, and 18-months’ Follow-up Compared With Noninfected Controls

| Controls | Cases 6 mo | Cases 12 mo | Cases 18 mo | Excess Risk Compared With Controls, % (CI) P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 182 | N = 148 | N = 149 | N = 149 | 6 mo | 12 mo | 18 mo | |

| Fatigue | 9% (17) | 39% (58) | 41% (61) | 36% (53) | 30% (21–39) <.001 | 32% (23–41) <.001 | 26% (17–35) <.001 |

| More than usual | 9% (17) | 32% (47) | 36% (53) | 32% (48) | 22% (14–31) <.001 | 26% (17–35) <.001 | 23% (14–31) <.001 |

| Much more than usual | 0% (0) | 7% (11) | 5% (8)) | 3% (5) | 7% (3–12) <.001 | 5% (2–9).004 | 3% (0–6).023 |

| Concentration problems | 4% (7) | 22% (33) | 29% (43) | 26% (38) | 18% (11–26) <.001 | 25% (17–33) <.001 | 22% (14–29) <.001 |

| More than usual | 4% (7) | 18% (27) | 27% (40) | 23% (35) | 14% (8–21) <.001 | 23% (15–31) <.001 | 20% (12–27) <.001 |

| Much more than usual | 0% (0) | 4% (6) | 2% (3) | 2% (3) | 4% (0–7) .012 | 2% (0– 4) .080 | 2% (0–4) .080 |

| Memory problems | 5% (9) | 21% (31) | 29% (43) | 33% (49) | 16% (9–23) <.001 | 24% (16–32) <.001 | 28% (20–36) <.001 |

| More than usual | 4% (8) | 20% (29) | 27% (40) | 30% (45) | 15% (8–22) <.001 | 22% (15–30) <.001 | 26% (18–34) <.001 |

| Much more than usual | 1% (1) | 1% (2) | 2% (3) | 3% (4) | 1% (−1 to 3) .227 | 1% (−1 to 4) .251 | 2% (−1 to 5) .136 |

| Dyspneaa | 5% (9) | 16% (23) | 17% (25) | 16% (24) | 11% (4–17) .002 | 12% (5–19) <.001 | 11% (4–18) .001 |

Severity of dyspnea was not recorded at 6 and 12 months.

Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Association Between Acute-phase Symptoms and Long COVID

The majority of cases were symptomatic in the acute phase (226/233 cases). When adjusted for age, sex, and comorbidities, acute-phase dyspnea was associated with an increased risk of fatigue (aOR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.16–3.95; P = .010) and dyspnea (aOR, 8.55; 95% CI, 2.77–26.32; P = .002) at 12 months’ follow-up, and acute-phase headache was associated with impaired concentration (aOR, 2.34; 95% CI, 1.03–5.29; P = .040) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations Between Acute Symptoms, Early Immune Responses, and Long COVID Symptoms at 12 Months in Adult Casesa

| Fatigue aOR (CI) P Value |

Memory Problems aOR (CI) P Value |

Impaired Concentration aOR (CI) P Value |

Dyspnea aOR (CI) P Value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute phase headache (n = 196) | 1.37 (.69–2.74) .3700 |

1.38 (.65–2.93) .4100 |

2.34 (1.03–5.29)

.0400 |

1.40 (.55–3.53) .4800 |

| Acute phase dyspnea (n = 198) |

2.14 (1.16–3.95)

.0100 |

1.85 (.95–3.59) .0700 |

1.11(.58–2.12) .7600 |

8.55 (2.77–26.32)

.0002 |

| Acute phase fever (n = 198) | 1.40 (.72–2.70) .3200 |

1.17 (.58–2.39) .6600 |

1.50 (.73–3.08) .2700 |

.90 (.39–2.09) .8100 |

| Acute phase myalgia (n = 198) | 1.51 (.80–2.86) .2100 |

1.48 (.73–2.98) .2800 |

1.46 (.73–2.93) .2900 |

3.73 (1.34–10.35)

.0100 |

| Spike IgG titer at 2 mob (n = 209) | 1.16 (.64–2.1) .6300 |

1.14 (.58–2.22) .7100 |

1.39 (.71–2.73) .3300 |

3.06 (1.23–7.61)

.0200 |

| Microneutralizing antibody titer at 2 moc (n = 195) |

.95 (.55–1.64) .8500 |

.80 (.43–1.49) .4800 |

.98 (.54–1.8) .9600 |

1.21 (.59–2.48) .6000 |

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, 95% confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Presented as age, sex, and comorbidity adjusted odds ratios, with corresponding 2-sided P values <.05 shown in bold.

IgG titer range: 50–98 924. Samples with undetectable spike IgG titers were given a value of 50. Titers were log(10) transformed for calculation purposes.

MN titer range: 10–16 096. Samples with undetectable microneutralizing (MN) antibodies were given a value of 50. Titers were log(10) transformed for calculation purposes.

Association of Antibody Titers and Long COVID

We measured SARS-COV-2 spike-specific IgG antibody titers at 2, 4, 6, and 12 months after infection. Antibodies waned over time (Supplementary Table 4), and antibody titers measured at 2 months were considered to reflect the peak of humoral response [31]. Peak spike-binding IgG (geometric mean titer 6128, range 50–98 924) and longitudinal antibody titers from 2 to 12 months, were associated with dyspnea at 12 months and persistent dyspnea from 6 to 12 months, in adjusted analysis (P = .02 and P = .05) (Table 3, Figure 4A). Longitudinal antibody responses were not significantly higher in cases with ≥3 symptoms at 12 months compared with those with no symptoms, or in cases with persistent fatigue at 6 and 12 months compared with cases without fatigue (Figure 4B–C).

Association of Persisting Symptoms and T-cell Responses

We measured the correlations between SARS-CoV-2-associated class I restricted (CD8+) or class II restricted (CD4+) TCRs and spike IgG titers from the same time points. Spike IgG antibodies correlated more strongly with CD4+ than CD8+ spike-specific TCRs. Significant correlations between spike IgG and CD4+ clonal breadth and depth were observed at 2 months (r = 0.371, P < .0001; and r = 0.315, P < .001), respectively, and at 6 months (r = 0.276, P < .001; and r = 0.251, P < .001). Whereas only the spike IgG and CD8+ clonal depth correlation at 2 months was significant (r = 0.139, P = .039). SARS-CoV-2-specific clonal depth (total, CD4+, and spike-specific CD4+) at 6 months was associated with increased number of symptoms at 12 months, when adjusted for age, sex, and the reciprocal TCR breadth (Table 4). Total CD4+ spike-specific clonal depth was also associated with dyspnea at 12 months.

Table 4.

Associations Between SARS-CoV-2-associated T-cell Clonal Deptha and Fatigue, Memory/concentration, Dyspnea, and Number of Symptoms at 12 mo

| SARS-CoV-2-associated T-cell Receptor Sequences |

Fatigue aOR (SE)c P Value |

Memory Problems + Impaired Concentration aOR (SE)c P Value |

Dyspnea aOR (SE)c P Value |

Number of Symptoms at 12 mob aRR (SE)d P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total T-cell clonal depth | 1.55 (.332) .1880 |

1.86 (.378) .102 |

1.49 (.497) .4250 |

1.71 (.274)

.0499 |

| Total CD4+ T-cell clonal depth | 1.80 (.362) .1060 |

1.98 (.395) .0827 |

1.85 (.568) .2780 |

1.94 (.294)

.0242 |

| Total spike-specific CD4+ T-cell clonal depth | 2.70 (.583) .0889 |

2.77 (.608) .0943 |

7.12 (.969)

.0427 |

3.15 (.483)

.0176 |

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; aRR, adjusted rate ratio; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SE, standard error.

One-tailed Fisher exact test identified 8630 SARS-CoV-2-associated TCRβ sequences, and potential false positive TCRβ sequences associated with cytomegalovirus (CMV) or human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles were removed. SARS-CoV-2-associated TCRβ sequences subsets were classified as class I associated (CD8+ T cells) or class II associated (CD4+ T cells), and spike or nonspike-associated. T-cell depth corresponded to the relative expansion of SARS-CoV-2-associated T-cell clonal subtypes.

Number of symptoms at 12 months were encoded as integers from 0 to 11 including the total of 11 symptoms assessed.

Odds ratio (OR), adjusted for age, sex, and scaled reciprocal SARS-CoV-2 associated T-cell breadth, with standard error (SE), corresponding 2-sided P value <.05 are shown in bold.

Rate ratio (RR), adjusted for age, sex, and scaled reciprocal SARS-CoV-2-associated T-cell breadth, with standard error (SE), corresponding 2-sided P value <.05 are shown in bold.

DISCUSSION

In this longitudinal observational case-control study, we found that half of the home-isolated cases still had at least 1 residual symptom 12 and 18 months after infection. Compared with controls, cases had significant excess risk of the dominant long COVID symptoms: fatigue, memory and concentration problems, and dyspnea.

A key strength of our study is the inclusion of age-matched, seronegative controls recruited from the same geographical location and during the same period as the cases. Both cases and controls, therefore, had similar exposures to pandemic-related public infection control measures, disrupted social services, and psychosocial stress. We show that the excess fatigue, cognitive symptoms, and dyspnea reported by cases are likely sequelae of mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. Other case-control studies find excess burden of main long COVID symptoms in cases compared with influenza controls [32], healthy adults [14], and children, but the quality-of-life scores were lower in pediatric controls [17], suggesting that pandemic circumstances have affected the health of young people considerably.

Investigating longitudinal symptoms trajectories is important to predict the long COVID burden. In our study, specific symptoms evolved differently over time in individual cases, supporting the fluctuating nature of long COVID previously described [33]. Symptom debut later than 6 months after infection could also reflect a coincidental overlap with emerging symptoms attributable to other causes or personal circumstances.

In noncontrolled studies, the proportion of patients with residual symptoms at 12 months varies considerably (39%–77%) [7, 9–13], and we found a prevalence of 46% in our cases. The prevalence of fatigue, a dominating long COVID sequelae, ranges from 27% [12] in nonhospitalized, 16% to 53% in mixed populations [11, 13] to 10% to 33% [7, 8, 10] in hospitalized patients, partly reflecting differences in patient selection and symptom assessment [9]. In our subgroup of cases followed for 18 months, the prevalence of most symptoms remained at similar levels throughout, whereas memory difficulties increased, particularly among women. Although a body of research essentially describe improvement of long COVID over time, studies have described durable symptoms concerning mental health and cognition [14, 15]. Our finding of a lack of improvement in memory difficulties over time is of concern.

Although sometimes perceived as vague symptoms and not always being recognized by the healthcare systems, cognitive symptoms may have significant impact on daily activity and work performance. Our study provides some reassurance for patients with persistent cognitive symptoms in that most cases reported moderate symptoms, and that there was no significant excess risk of severe cognitive symptoms at 12 and 18 months.

SARS-CoV-2 infection leads to sustained alteration of immune responses and spike-specific IgG titers appears to be associated with long COVID in both hospitalized and home-isolated patients [22, 25, 34]. Our study found that higher peak and longitudinal spike-specific IgG was associated with persistent dyspnea at 12 months. Interestingly, neutralizing antibodies levels were not associated with long-term symptoms, suggesting that other antibody effector mechanisms such as complement activation, Fc receptor binding, or cross-reactivity to autoantigens, could be involved in long COVID [35–37]. No association was observed between spike-specific IgG and cognitive symptoms. The role of antibodies in this pathology remains unclear, although SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies have been discovered in the cerebrospinal fluid of COVID-19 patients [38], with abnormal oligoclonal banding patterns found in mild COVID-19 with cognitive sequelae [39]. Furthermore, cerebral elevated cytokine levels and brain abnormalities found in long COVID patients are compatible with inflammatory damage [40].

Dysregulation of T-cell activation and their associated cytokine mediators suggest an aberrant systemic immune response in long COVID patients [26]. Here, we found that the spike-specific CD4+ TCR clonal depth at 6 months was associated with increased number of long COVID symptoms and dyspnea at 12 months, suggesting a role for CD4+ T cells in long COVID. This may indicate an extensive immune stimulation driving T-cell proliferation, resulting in an increased magnitude and duration of circulating spike-specific T cells and their associated antibodies. T-cell-mediated tissue damage, disruption of cytokines, and cell signalling homeostasis, may thus be involved in the pathogenesis of long COVID. Further studies should investigate the role of antigen-driven dysregulation of T cells in long COVID, including functional and phenotypic characteristics of T-cell subsets.

Our study is limited by the small size hampering subgroup analysis, potential bias in self-reported symptoms, suboptimal sex- and comorbidity-matching for controls, and lack of information for controls on certain variables of interest for long COVID, such as smoking and body mass index. Strengths of our study are the inclusion of a near-complete geographical cohort from the first pandemic wave and the personalized follow-up to detect long COVID symptoms, which may be missed in healthcare-based registry studies. All cases were infected with the ancestral Wuhan-like strain, and the prevalence of long COVID may differ after infection with subsequent variants of concern, which have increased infectivity and cause a different range of organ-specific symptoms.

Overall, our findings should be considered as intermediate because longer follow-up will be required to understand the nature and chronicity of long COVID. Nonetheless, it is worrisome that fatigue, dyspnea, and cognitive problems after infection have affected an important portion of the working-age population over this extensive period.

CONCLUSION

The positive association between spike IgG antibodies and CD4+ associated SARS-CoV-2 specific TCR sequences with long-term symptoms, supports previous published results linking immune responses to long COVID pathogenesis. Hallmark long COVID symptoms occurred far more frequently in cases than in time- and age-matched confirmed seronegative controls, suggesting a causal relationship between COVID-19 and sequelae. The high proportion of symptomatic patients at 18 months, particularly those with cognitive symptoms is concerning. It is somewhat reassuring that few patients perceived their cognitive symptoms as severe at 18 months.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Elisabeth B Fjelltveit, Influenza Centre, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway; Department of Microbiology, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway.

Bjørn Blomberg, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway; National Advisory Unit for Tropical Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway.

Kanika Kuwelker, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway; Department of Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway.

Fan Zhou, Influenza Centre, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway.

Therese B Onyango, Influenza Centre, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway.

Karl A Brokstad, Influenza Centre, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway; Department of Safety, Chemistry and Biomedical Laboratory Sciences, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Bergen, Norway.

Rebecca Elyanow, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Ian M Kaplan, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Camilla Tøndel, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway; Department of Research and Development, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway; Department of Pediatrics, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway.

Kristin G I Mohn, Influenza Centre, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway; Department of Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway.

Türküler Özgümüş, Department of Global Public Health and Primary Care, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway.

Rebecca J Cox, Influenza Centre, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway; Department of Microbiology, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway.

Nina Langeland, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway; National Advisory Unit for Tropical Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway.

Bergen COVID-19 Research Group:

Geir Bredholt, Lena Hansen, Sarah Larteley Lartey, Anders Madsen, Jan Stefan Olofsson, Sonja Ljostveit, Marianne Sævik, Hanne Søyland, Helene Heitmann Sandnes, Nina Urke Ertesvåg, Juha Vahokoski, Amit Bansal, Håkon Amdam, Tatiana Fomina, Dagrun Waag Linchausen, Synnøve Hauge, Annette Corydon, and Silje Sundøy

Notes

Author contributions. N.L. and R.J.C. conceived and designed the study. K.K. and E.B.F. performed literature search. K.K., E.B.F., C.T., and K.G.I.-M., recruited the participants and undertook follow-up. F.Z. developed and ran the neutralization assays. T.B.O. conducted the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. K.A.B. organized sample collection and the T-cell receptor (TCR) analyses. R.E. and I.M.K. conducted the TCR analyses. T.Ö. and E.B.F. analyzed the data. B.B., R.J.C., N.L., and E.B.F. interpreted the data. N.L., R.J.C., B.B., and E.B.F. wrote the manuscript. Members of the coronavirus disease 2019 research group contributed to the study follow-up, data collection and laboratory assays. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments. We thank all the participants who altruistically gave their time and blood samples to the study. We thank the Bergen Municipality Emergency Clinic for excellent collaboration in the initial patient recruitment. We also thank the Clinical Trials unit, Occupational Health Department at Haukeland University Hospital for invaluable assistance, and the Research Unit for Health Surveys (RUHS), University of Bergen, for their assistance in patients’ and household contacts data collection. We thank Professor Florian Krammer, Department of Microbiology, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai, New York, for supplying the receptor-binding domain and spike constructs, and finally the Adaptive Biotechnologies for their analysis of TCR-sequencing data.

Following is a list of members of the Bergen COVID-19 Research Group and their affiliations: Geir Bredholt (Influenza Centre, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Norway), Lena Hansen (Influenza Centre, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Norway), Sarah Larteley Lartey (Influenza Centre, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Norway), Anders Madsen (Influenza Centre, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Norway), Jan Stefan Olofsson (Influenza Centre, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Norway), Sonja Ljostveit (Influenza Centre, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Norway), Marianne Sævik (Department of Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway), Hanne Søyland (Department of Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway), Helene Heitmann Sandnes (Influenza Centre, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Norway), Nina Urke Ertesvåg (Influenza Centre, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Norway), Juha Vahokoski (Influenza Centre, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Norway), Amit Bansal (Influenza Centre, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Norway, Mai Chi Trieu (Influenza Centre, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Norway), Håkon Amdam (Influenza Centre, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Norway), Tatiana Fomina (Department of Global Public Health and Primary Care, University of Bergen), Dagrun Waag Linchausen (Bergen Municipality Emergency Clinic, Bergen, Norway), Synnøve Hauge (Research Unit for Health Surveys, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway), Annette Corydon (Bergen Municipality Emergency Clinic, Bergen, Norway), and Silje Sundøy (Influenza Centre, Department of Clinical Science, University of Bergen, Norway).

Financial support. This work was supported by the University of Bergen, Norway, which supported E.B.F.’s candidate position, funded intramurally by the Influenza Centre, Department of Microbiology, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway. The Influenza Centre is supported by the Trond Mohn Stiftelse (TMS2020TMT05), the Ministry of Health and Care Services, Norway; Helse Vest (F-11628, F-12167, F-12621), the Norwegian Research Council Globvac (284930); the European Union (EU IMI115672, FLUCOP, IMI2 101007799 Inno4Vac, H2020 874866 INCENTIVE, H2020 101037867 Vaccelerate); the Faculty of Medicine, University of Bergen, Norway; and Nanomedicines Flunanoair (ERA-NETet EuroNanoMed2 JTC2016) and Pasteur legatet & Thjøtta’s legat, University of Oslo, Norway (101563). RUHS. receives support from Trond Mohn Stiftelse (TMS). I.M.K. reports support for this work as a full-time employee at Adaptive Biotechnologies at the time of the study. R.E. also reports support from Adaptive Biotechnologies.

References

- 1. Prevention CfDCa . Post COVID Conditions. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/index.html.

- 2. Excellence NIfHaC . COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188/chapter/Recommendations. [PubMed]

- 3. Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med 2021; 27:601–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization . A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus, 6 October 2021 Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post_COVID-19_condition-Clinical_case_definition-2021.1.

- 5. Nanwani-Nanwani K, López-Pérez L, Giménez-Esparza C, et al. Prevalence of post-intensive care syndrome in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19. Scientific Reports 2022; 12:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rousseau AF, Minguet P, Colson C, et al. Post-intensive care syndrome after a critical COVID-19: cohort study from a Belgian follow-up clinic. Ann Intensive Care 2021; 11:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fumagalli C, Zocchi C, Tassetti L, et al. Factors associated with persistence of symptoms 1 year after COVID-19: a longitudinal, prospective phone-based interview follow-up cohort study. Eur J Int Med 2022; 97:36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Huang L, Yao Q, Gu X, et al. 1-year outcomes in hospital survivors with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. The Lancet 2021; 398:747–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bellan M, Baricich A, Patrucco F, et al. Long-term sequelae are highly prevalent one year after hospitalization for severe COVID-19. Sci Rep 2021; 11:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang X, Wang F, Shen Y, et al. Symptoms and health outcomes among survivors of COVID-19 infection 1 year after discharge from hospitals in Wuhan, China. JAMA Network open 2021; 4:e2127403-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim Y, Bitna H, Kim SW, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome in patients after 12 months from COVID-19 infection in Korea. BMC Infect Dis 2022; 22:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boscolo-Rizzo P, Guida F, Polesel J, et al. Sequelae in adults at 12 months after mild-to-moderate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2021; 11:1685–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Seessle J, Waterboer T, Hippchen T, et al. Persistent symptoms in adult patients one year after COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 16:e0256142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang L, Li X, Gu X, et al. Health outcomes in people 2 years after surviving hospitalisation with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2022; 10:863–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Helmsdal G, Hanusson KD, Kristiansen MF, et al. Long COVID in the long run-23 months follow-up study of persistent symptoms. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022; 9:ofac270. Oxford University Press.

- 16. Groff D, Sun A, Ssentongo AE, et al. Short-term and long-term rates of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a systematic review. JAMA Network Open 2021; 4:e2128568-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Berg SK, Palm P, Nygaard U, et al. Long COVID symptoms in SARS-CoV-2-positive children aged 0–14 years and matched controls in Denmark (LongCOVIDKidsDK): a national, cross-sectional study. Lancet Child Adoles Health 2022; 6:614–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Havervall S, Rosell A, Phillipson M, et al. Symptoms and functional impairment assessed 8 months after mild COVID-19 among health care workers. JAMA 2021; 325:2015–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim Y, Kim S-W, Chang H-H, Kwon KT, Bae S, Hwang S. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome in patients after 12 months from COVID-19 infection in Korea. BMC Infect Dis 2022; 22:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lund LC, Hallas J, Nielsen H, et al. Post-acute effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection in individuals not requiring hospital admission: a Danish population-based cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2021; 21:1373–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xie Y, Bowe B, Al-Aly Z. Burdens of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 by severity of acute infection, demographics and health status. Nat Commun 2021; 12:6571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blomberg B, Mohn KG, Brokstad KA, et al. Long COVID in a prospective cohort of home-isolated patients. Nat Med 2021; 27:1607–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Havervall S, Jernbom Falk A, Klingstrom J, et al. SARS-CoV-2 induces a durable and antigen specific humoral immunity after asymptomatic to mild COVID-19 infection. PloS One 2022; 17:e0262169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Garcia-Abellan J, Padilla S, Fernandez-Gonzalez M, et al. Antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 is associated with long-term clinical outcome in patients with COVID-19: a longitudinal study. J Clin Immunol 2021; 41:1490–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Peluso MJ, Deitchman AN, Torres L, et al. Long-term SARS-CoV-2-specific immune and inflammatory responses in individuals recovering from COVID-19 with and without post-acute symptoms. Cell Rep 2021; 36:109518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Phetsouphanh C, Darley DR, Wilson DB, et al. Immunological dysfunction persists for 8 months following initial mild-to-moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Immunol 2022; 23:210–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kuwelker K, Zhou F, Blomberg B, et al. Attack rates amongst household members of outpatients with confirmed COVID-19 in Bergen, Norway: a case-ascertained study. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2021; 3:100014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, et al. Development of a fatigue scale. J Psychosom Res 1993; 37:147–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Trieu MC, Bansal A, Madsen A, et al. SARS-CoV-2-Specific neutralizing antibody responses in Norwegian health care workers after the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic: a prospective cohort study. J Infect Dis 2021; 223:589–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Snyder TM, Gittelman RM, Klinger M, et al. Magnitude and dynamics of the T-cell response to SARS-CoV-2 infection at both individual and population levels. medRxiv 2020.Version 3. Preprint. NaN NaN [revised 2020 Sep 17]. doi: 10.1101/2020.07.31.20165647

- 31. Tan W, Lu Y, Zhang J, et al. Viral kinetics and antibody responses in patients with COVID-19. medRxiv 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.24.20042382 [DOI]

- 32. Taquet M, Dercon Q, Luciano S, Geddes JR, Husain M, Harrison PJ. Incidence, co-occurrence, and evolution of long-COVID features: a 6-month retrospective cohort study of 273,618 survivors of COVID-19. PLoS medicine 2021; 18:e1003773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tran V-T, Porcher R, Pane I, Ravaud P. Course of post COVID-19 disease symptoms over time in the ComPaRe long COVID prospective e-cohort. Nat Commun 2022; 13:1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Peghin M, Palese A, Venturini M, et al. Post-COVID-19 symptoms 6 months after acute infection among hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients. Clin Microbiol Infect 2021; 27:1507–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kaplonek P, Fischinger S, Cizmeci D, et al. mRNA-1273 vaccine-induced antibodies maintain Fc effector functions across SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. Immunity 2022; 55:355–65 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chang SE, Feng A, Meng W, et al. New-onset IgG autoantibodies in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Nat Commun 2021; 12:5417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lucchese G, Flöel A. SARS-CoV-2 and Guillain-Barre syndrome: molecular mimicry with human heat shock proteins as potential pathogenic mechanism. Cell Stress Chaperones 2020; 25:731–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Borsche M, Reichel D, Fellbrich A, et al. Persistent cognitive impairment associated with cerebrospinal fluid anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies six months after mild COVID-19. Neurol Res Pract 2021; 3:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Apple AC, Oddi A, Peluso MJ, et al. Risk factors and abnormal cerebrospinal fluid associate with cognitive symptoms after mild COVID-19. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2022; 9:221–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Douaud G, Lee S, Alfaro-Almagro F, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is associated with changes in brain structure in UK Biobank. Nature 2022; 604:697–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.