Abstract

Wearing a mask or a face covering became mandatory in indoor public spaces to reduce the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The Ontario government (i.e., a province of Canada) encouraged medical supply producers to switch their operations to produce personal protective equipment (e.g., masks) during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this regard, there are several uncertain parameters (e.g., operational costs, market demand, and capacity levels of facilities) affecting the performance of producers in a medical supplies market. In this study, we propose a flexible optimization model to configure a robust mask supply chain network under uncertainty. Furthermore, companies are supposed to undertake their operations based on sustainable manners, in compliance with provincial policy, in Ontario. Therefore, the proposed flexible optimization model is extended to a robust multi-objective model to investigate sustainable strategies in a mask supply chain network design problem. The applicability of this model is demonstrated for the Greater Toronto Area, Canada.

Keywords: Supply chain network, Multi-objective model, Mixed-integer linear programming, Robust optimization, COVID-19 outbreak

Introduction

The recent COVID-19 outbreak caused major uncertainty for supply chain networks (SCNs) across the world. A general structure of SCNs may consist of multiple echelons such as suppliers, producers, distribution centers, retailers, and customer zones. A successful SCN design should have sufficient flexibility to fulfill customer expectations in high-risk situations. The adoption of proactive strategies (e.g., inventory planning for handling fluctuations in supply and demand) leads to mitigating structural risks in uncertain circumstances (Amin & Zhang, 2013; Iyengar et al., 2020; Olivares-Aguila & ElMaraghy, 2021; Tosarkani et al., 2020). Two types of operational and disruption risks may occur in SCNs. The operational risk is caused by daily disturbance such as volatility in demand, while the disruption risk stems from high-impact events such as earthquakes, strikes, and disease outbreaks. Accordingly, the disruption risk leads to a significant impact on the structure of SCNs since some facilities may become unavailable (Govindan et al., 2020; Ivanov, 2020).

SCNs incorporate all strategic, tactical, and operational decisions (e.g., opening new facilities, partner selection, procurement, production and inventory planning, customer service, logistics, and transportations) through the collaboration between multiple entities (e.g., producers and intermediaries) to fulfill customer expectations (Yousefi et al., 2021; Rezaee et al., 2017). In supply chain planning, efforts should be implemented to coordinate materials, information, and financial flows (Choi et al., 2017; Yousefi & Tosarkani, 2022). As mentioned previously, there are several sources of uncertainties affecting SCN configuration. Hence, different mathematical approaches can be applied to deal with uncertainties in facility location problems (e.g., robust optimization, stochastic, and possibilistic programming). The adoption of such methods depends on the type of imprecise (i.e., uncertain) parameters incorporating into optimization models. Robust optimization is applicable when variations of parameters are definable (e.g., bounded uncertainty sets) (Ben-Tal & Nemirovski, 2002; Prakash et al., 2020; Vahdani & Mohammadi, 2015). Stochastic programming is employed when probability distributions of random parameters are known (Amin et al., 2017; Badri et al., 2017; Lima et al., 2018). However, in some cases, the statistical distributions of uncertain parameters (e.g., fluctuations in capacity levels of resources due to prevention policies and practices during the COVID-19 pandemic) cannot be estimated. In such cases, the fuzzy theory is applied to define imprecise parameters through a membership function (Amin et al., 2020; Tsao et al., 2018).

The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared that the coronavirus spreads primarily from person to person through small droplets from the nose or mouth when the person with COVID-19 coughs, sneezes, or speaks. Masks are supposed to be used to keep full protection of the eyes, nose, and mouth. On this matter, the presence of an efficient, effective, and robust mask SCNs is essential for COVID-19 prevention. This research is inspired by a medical device SCN in the GTA, including medical manufacturer(s), distribution center(s), retailer(s), and customers. In this respect, several uncertain factors are interfering with an optimal SCN configuration. To prevent the spread of COVID-19, many employees (except essential workers) either stay at home or work from home limiting the hours of operation. Furthermore, all employees presenting at their workplace should continue to practice physical distancing. This has a negative impact on the capacity levels of entities involved in SCNs, particularly in the healthcare sector, requiring long hours of operations due to the high-volume demand. The other uncertain parameters include market demand and major variable costs of transportation, production, and holding inventory. In this study, we develop a robust flexible multi-objective programming (RFMOP) model for a mask SCN under uncertainty in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), Canada. The developed model enables managers to create robust SCNs for managing different types of risks. Accordingly, this model considers a variety of imprecise parameters (e.g., the capacity of producers, market demand, and infection prevention policies and practices) that affect the optimal configuration of SCNs during high-impact events.

The structure of this study is organized as follows: Sect. 2 reviews the previous studies in the field of the research. The research methodology and problem definition are provided in Sects. 3 and 4, respectively. Section 5 presents the proposed mathematical models to address the defined problem and discusses the results. The practical implications of this study are discussed for practitioners in Sect. 6. Finally, Sect. 7 describes concluding remarks and future research avenues.

Literature review

SCN design using stochastic programming

The relevant studies using a stochastic programming (SP) model in facility location problems are reviewed in this section. Subulan et al. (2015) designed a closed-loop supply chain network (CLSCN) for lead-acid battery production, using a scenario-based stochastic and possibilistic model considering financial and collection risks. Ameknassi et al. (2016) integrated logistics outsourcing decisions in an SCN design. They established multiple scenarios, including the uncertainty of demand, the capacity of facilities, quantity and quality of returned products, and other variable costs. Keyvanshokooh et al. (2016) developed a profit maximization model to design a CLSCN considering various scenarios for stochastic transportation costs. Soleimani et al. (2016) applied a mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) model to develop a CLSCN with stochastic demand and price. Jeihoonian et al. (2017) utilized a two-stage stochastic MILP model to configure a CLSCN for modular structured products. Binary scenarios were considered to handle uncertainty in the quality of the return stream. Fahimnia et al. (2017) created a stochastic bi-objective model for a blood SCN in a disaster situation, which focused on minimizing the total cost and delivery time. Badri et al. (2017) applied a two-stage stochastic programming (TSP) model for a value-based SCN design. Fathollahi-Fard et al. (2018) investigated the economic and social aspects of a CLSCN design using a multi-objective SPM. Heydari et al. (2018) proposed an analytical model to coordinate the order quantity and service level in a seller-buyer SCN with stochastic demand. Yu and Solvang (2018) mentioned that reverse product flow may have stochastic specifications due to the unpredictable quality of returned products and the fluctuations in pricing for remanufactured items. They applied a TSP model to design a reverse logistics network (RLN) under uncertainty.

Quddus et al. (2018) developed a two-stage chance-constrained stochastic model for a bio-fuel SCN with uncertain feedstock supply (e.g., forest residues, and municipal waste). Zahiri et al. (2018) investigated the uncertainty in blood donation through a multi-stage SP model in a blood SCN. Ghelichi et al. (2018) developed a flexible SP model to design a green biodiesel SCN under the uncertainty of fuel demand. Hamdan and Diabat (2019) considered production, inventory, and location decisions using a TSP model for a blood SCN design. Poudel et al. (2019) designed a biomass SCN with regard to uncertain feedstock supply using a TSP model. Tosarkani and Amin (2019) designed a lead-acid battery CLSCN considering the environmental compliance of involved facilities. They examined multiple scenarios for recovery rates of returned products with a given probability of occurrence. Zhang et al. (2020) investigated the quick response in a two-echelon SCN with the stochastic production capacity. They developed the two-stage two-ordering model and employed dynamic programming to obtain an optimal ordering policy. Nur et al. (2021) proposed a novel TSP model for a biofuel SCN design incorporating related uncertain parameters such as biomass quality. Lin et al. (2020) designed a vaccine SCN, including manufacturers, distributors, and retailers (e.g., hospitals). They investigated the risks and uncertainty associated with vaccine-related adverse events and temperature damage to vaccines due to malfunctions of temperature-controlling equipment.

SCN design using fuzzy programming

In some cases, it is required to apply a fuzzy optimization model to cope with epistemic uncertainty due to the imprecise nature of input data. Dai and Zheng (2015) integrated fuzzy programming and chance-constrained programming methods to deal with uncertain disposal rates, demand, and capacity levels in a CLSCN design. Sherafati and Bashiri (2016) developed a novel fuzzy optimization method to design a CLSCN with fuzzy tactical decision variables. Amin and Baki (2017) applied a fuzzy multi-objective programming (MOP) model to deal with uncertain demand for a global CLSCN design. Dai and Li (2017) designed a multi-echelon CLSCN considering fuzzy parameters (e.g., demand, capacity levels, and prices). They proposed a bi-objective model including the total profit and waste of facilities involved in their model.

Tosarkani and Amin (2018a) introduced a fully fuzzy solution approach for a battery CLSCN. All the input parameters and decision variables were assumed to be uncertain in their created model. Yu et al. (2018) designed a dual-channel SCN for agri-product concerning information uncertainty. They employed triangular fuzzy numbers (TFNs) to deal with uncertainty. Tosarkani et al. (2020) designed a scenario-based possibilistic model for an electronic RLN design. TFNs were applied to cope with the uncertainty of demand, return, and variable costs. Tirkolaee et al. (2020) applied an integrated approach, including fuzzy decision-making and MOP, to design a reliable two-echelon SCN. Zandkarimkhani et al. (2020) proposed a bi-objective MILP model to design a perishable pharmaceutical SCN under uncertainty of demand. They developed a chance-constrained fuzzy goal programming model to solve a simultaneous facility location and vehicle routing problem. Goodarzian et al. (2021) proposed a fuzzy bi-objective MILP model to address the green medicine SCN design. They used various meta-heuristic algorithms (e.g., social engineering optimization and hybrid whale optimization to solve this model.

SCN design using robust optimization

A robust solution approach enhances the feasibility and performance of optimization models when their infeasibility costs are considerable. Mousazadeh et al. (2015) applied a robust possibilistic programming approach to design a pharmaceutical SCN concerning epistemic uncertainty. Akbari and Karimi (2015) introduced a novel robust optimization (RO) model to design a multi-echelon SCN considering process uncertainty. Bai and Liu (2016) presented a new RO approach for an SCN configuration with regard to the variability of demand. Talaei et al. (2016) developed a robust fuzzy programming model (RFPM) to design a carbon-efficient CLSCN under the uncertainty of input parameters. Guo et al. (2016) presented an RO model to design an SCN regarding macroeconomic fluctuations. Golpîra et al. (2017) introduced a robust bi-level optimization model for a green SCN configuration to mitigate the uncertainty of demand and costs of transportation and shortage. Zokaee et al. (2017) employed an RO model to design an SCN considering the uncertainty of demand, supply, and major costs.

Alavi and Jabbarzadeh (2018) applied an RO approach for a CLSCN design to deal with the uncertainty of recycled products and market demand. Kim et al. (2018) utilized an RO method for a fashion CLSCN planning under uncertainty of market demand and RL flow. Ghahremani-Nahr et al. (2019) developed an RFPM for a multi-echelon CLSCN considering discounts on the purchase of components, shortage, and uncertain parameters (e.g., demand, return, and major costs). Yavari and Geraeli (2019) introduced an RO method to design a green CLSCN for perishable items regarding uncertain demand, quantity, and quality of returned products. Hamdan and Diabat (2020) proposed a bi-objective RO model to configure a blood SCN. The bi-objective model was applied to minimize the total cost and delivery time associated with the supply of blood during the occurrence of disasters. Sinha et al. (2020) utilized an RO approach to mitigate the impact of cost disturbance due to demand variation on the configuration of a multi-echelon apparel SCN. Arabsheybani and Arshadi Khasmeh (2021) proposed a robust bi-objective multi-product mathematical model to consider resiliency and uncertainty in SCN design. In this study, the ε-constraint method is employed to obtain Pareto solutions for a real case in the food industry.

SCN design considering sustainability

The economic benefits have been the primary consideration in the configuration of SCNs. However, lately, the concept of circular supply chains has appeared in operations management due to the advance of technologies and the growing level of environmental awareness (Choi et al., 2020). Govindan et al. (2016) mentioned that optimization of the social responsibility along with the environmental impact of operations should be considered in addition to the economic motivations of companies in an RLN design. In this regard, they proposed an MOP model to minimize the present value of costs, the environmental impact, and maximize the social responsibility in a medical syringe recycling program. Zhang et al. (2016) proposed an MOP model (i.e., minimizing the total cost and environmental influences, and maximizing the customer coverage) for a sustainable SCN design. Soleimani et al. (2017) developed an MOP model (i.e., maximizing the total profit and fulfilling the customer demand, and minimizing the number of missed working days because of accidents) to configure a sustainable CLSCN. Nurjanni et al. (2017) introduced a new green SCN design to minimize the total cost and carbon dioxide emissions. Van Engeland et al. (2020) mentioned that a great number of benefits are associated with the domain of waste management and facility location problems such as reducing the consumption of raw materials and diverting waste from landfills and waterways. Arampantzi and Minis (2017) applied an MOP model (i.e., emissions costs, waste generation, and community development) to design a sustainable SCN. Tosarkani and Amin (2018b) developed an MOP model (i.e., the total expected profit, green practices, on-time delivery, and quality of products and services provided by third parties) to design a sustainable electronic RL using multiple-criteria decision-making (MCDM). Rohmer et al. (2019) mentioned that the current patterns of food consumption and production make a negative impact on the environment and food security for the next generation. Accordingly, they designed a sustainable SCN in the context of the global food system.

Vafaeenezhad et al. (2019) developed an MOP model (i.e., the total profit, greenhouse gas emissions, consumed energy, generated waste, travel distance of employees, and employment consistency) to design a sustainable SCN in the paper industry. Hosseini-Motlagh et al. (2019) developed a coordination mechanism to obtain the optimal pricing, sustainability levels, and corporate social responsibility in a competitive RLN. Mardan et al. (2019) proposed a bi-objective model (i.e., the total cost and environmental emissions) to design a green CLSCN. Zarei et al. (2020) proposed a multi-objective MILP (MOMILP) model (i.e., the total profit, greenhouse gas emissions, and water consumption) to design a sustainable natural gas SCN. Rabbani et al. (2020) introduced an MOMILP model (i.e., operation costs, gasoline-related costs, uncollected waste, and the number of created jobs) to design a sustainable bioethanol SCN. Dutta et al. (2020) applied an MOP model (i.e., the total cost, environmental impact, and social responsibility) to configure a sustainable RLN in the e-commerce market. Durmaz and Bilgen (2020) introduced an MOMILP model (i.e., the total expected profit and the total distance between farms and biogas facilities) to design a sustainable biomass SCN. Fung et al. (2020) investigated the external pressure and internal motivations for companies to apply a sustainable planning strategy in a fashion SCN. They employed the institutional theory through a triple bottom line framework, including social knowledge, value systems, and governmental policies. Table 1 illustrates the research contributions of some relevant research.

Table 1.

Review of some studies to design and optimize facility location models under uncertainty

| Authors | Network | Objective* | Sustainability | Multi-period | Multi-objective | Product | Solution approach | Real locations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subulan et al. (2015) | CLSCN | EA | ✓ | Battery | SP | ✓ | ||

| Bai and Liu (2016) | SCN | EA | ɱ | Food | RO and FP | |||

| Soleimani et al. (2016) | CLSCN | EA | A | Plastic water cane | SP | |||

| Amin and Baki (2017) | CLSCN | EA, SA | ✓ | ✓ | FP | ✓ | ||

| Kim et al. (2018) | CLSCN | EA | Fashion | RO | ✓ | |||

| Yu et al. (2018) | SCN | EA, SA | ✓ | ✓ | Agri-product | FP | ||

| Hamdan and Diabat (2020) | SCN | EA | ✓ | ✓ | Blood | RO | ✓ | |

| Tosarkani et al. (2020) | RL | EA, GA | ✓ | ✓ | Electronic | FP and SP | ✓ | |

| Hasani et al. (2021) | SCN | GA | ✓ | ✓ | Medical equipment | RO | ||

| Goodarzian et al. (2021) | SCN | GA | ✓ | Medical equipment | FP | |||

| Darmawan et al. (2021) | SCN | EA | ✓ | SP | ||||

| Fathollahi-Fard et al. (2021) | CLSCN | GA | ✓ | Tire | FP | |||

| Arani et al. (2021) | SCN | EA, GA, SA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Blood | RO | |

| Arabsheybani and Arshadi Khasmeh (2021) | SCN | EA | ✓ | Food | RO | |||

| Nur et al. (2021) | SCN | EA | ✓ | Biofuel | SP | ✓ | ||

| Liu et al. (2021) | CLSCN | EA | Food | RO and FP | ✓ | |||

| Shahedi et al. (2022) | CLSCN | EA, GA, SA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Automotive | SP | ✓ |

| Proposed model | SCN | EA, GA, SA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Mask | RFMOP | ✓ |

*Green aspect (GA), economic aspect (EA), social aspect (SA)

Research methodology

This research aims to develop an RFMOP for a mask SCN under uncertainty. As indicated in Fig. 1, the overall framework of this study can be summarized in three phases:

Phase 1: A mask SCN is configured in the GTA considering a realistic situation arising during the COVID-19 outbreak. In this regard, a flexible optimization model (FOM) is primarily developed to minimize the total cost of the SCN.

Phase 2: As mentioned previously, environmental and social objectives should be involved to design a sustainable SCN. The model proposed in Phase 1 is extended to the MOP model. The RO approach is also employed to handle the uncertainty of the mentioned imprecise parameters. Therefore, the FOM is advanced to the RFMOP model to enable decision-makers (DMs) for managing multiple objectives under uncertainty. To the best of our knowledge, such an integrated approach is novel in SCN literature.

Phase 3: The MOP model includes the total cost (z1), CO2 emissions (z2), and the producer capability index (CI) (z3). Two objectives of z1 and z2 consist of quantitative parameters, while z3 contains a qualitative index associated with the capability of producers to fulfill customer expectations. Hence, a fuzzy quality function deployment (QFD) model is utilized to convert the qualitative index of CI to a quantitative parameter. Then, the non-dominated solutions of the RFMOP model are computed and discussed as managerial insights for practitioners.

Fig. 1.

The overall approach to develop a proposed RFMOP model

Problem definition

According to Toronto By-Law 541–2020, wearing a mask or face covering is mandatory in indoor public spaces beginning July 7, 2020. There are 25 municipalities in the GTA with a total population of 6,417,516 (Canada statistics). In this regard, millions of people are affected by such an additional measure mandated to reduce the spread of the COVID-19. The Ontario government has begun investing in medical manufacturers to redesign their operations and expand their capacity levels to make personal protective equipment (PPE) (e.g., masks, face shields, and goggles). The COVID-19 pandemic has led to unprecedented demand for certain PPE supplies. Accordingly, the presence of robust healthcare SCNs for the purpose of handling fluctuations in demand and different types of risks is essential.

The applicability of the proposed solution approach is investigated using a leading company in advanced manufacturing of textile technology in the healthcare industry. Their productions include textile-based wearable items (e.g., biometric clothing) for the remote monitoring of brain, heart, and muscle activities. By the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, they have provided textile-based PPE to reduce the spread of coronavirus disease in the GTA, Ontario.

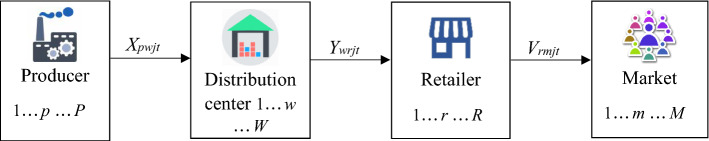

A multi-echelon, multi-product mask SCN is illustrated in Fig. 2. The network includes producer(s), distribution center(s), retailer(s), and customer zones (markets). The producer is responsible to hold an optimal operation plan to fulfill market demand. Distribution centers are utilized for the purpose of the rapid movement of products. Retailers are located in all municipal districts. However, the number of selected retailers is mainly dependent on the fluctuations in demand during the COVID-19 outbreak. This study aims to optimize three objectives of the total cost, CO2 emissions, and CI of the proposed SCN by answering the following questions:

Which and how many producer(s), distribution center(s), and retailer(s) should be considered?

How many products should be produced in each period?

How many products should be held as the inventory and how many should be sent to the markets?

Fig. 2.

The proposed mask SCN

Flexible optimization model

An FOM is proposed to minimize the total cost of a mask SCN configuration. Table 2 indicates the notation utilized in the formulation of the FOM.

| 1 |

Table 2.

Indices, parameters, and decision variables used in the mathematical programming

| Indices |

| P: Set of potential locations for producers (p ∈ P) |

| W: Set of distribution centers (w ∈ W) |

| R: Set of retailers (r ∈ R) |

| M: Set of Markets (m ∈ M) |

| T: Set of time periods (t ∈ T) |

| J: Set related to different types of mask supplied by producers (j ∈ J) |

| Parameters |

| Ap: Fixed cost of agreement with producer p |

| Bw: Fixed cost of agreement with distribution center w |

| Cr: Fixed cost of agreement with retailer r |

| aj: Unit cost of transportation related to mask j between producers and distribution centers |

| bj: Unit cost of transportation related to mask j between distribution centers and retailers |

| cj: Unit cost of transportation related to mask j between retailers and markets |

| qpw: Distance between producer p and distribution center w |

| swr: Distance between distribution center w and retailer r |

| urm: Distance between retailer r and market m |

| ej: Unit cost of supply related to mask j |

| fj: Unit cost of holding inventory related to mask j |

| Dmjt: Demand of mask j required at market m in period t |

| Epj: Capacity of producer p to produce mask j |

| Fwj: Capacity of distribution center w for shipping mask j |

| Grj: Capacity of retailer r for mask j |

| Hpj: Capacity of producer p for holding mask j |

| n: Truck capacity |

| k: Truck CO2 emissions per km |

| op: Capability of producer p to fulfill customer expectations |

| Decision variables |

| Mpjt: Quantity of available mask j for the supply at producer p in period t |

| Npjt: Quantity of mask j holding as the inventory at producer p in period t |

| Xpwjt: Quantity of mask j shipping to distribution center w from producer p in period t |

| Ywrjt: Quantity of mask j shipping to retailer r from distribution center w in period t |

| Vrmjt: Quantity of mask j shipping to market m from retailer r in period t |

| xp: 1, if a producer is selected at location p, 0, otherwise |

| yw: 1, if a distribution center is selected at location w, 0, otherwise |

| vr: 1, if a retailer is selected at location r, 0, otherwise |

Subject to the following constraints:

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

| 10 |

| 11 |

The objective function (1) is introduced to minimize the total cost of the mask SCN design. In this regard, variable costs (i.e., costs of supply, inventory, and transportation) along with fixed costs of agreement associated with producer(s), distribution center(s), and retailer(s) are taken into account. Constraint (2) implies that the quantity of products shipping to the distribution center(s) should be equal to the number of available products for the supply minus the number of products that must be held as the inventory in period t. Constraints (3) and (4) balance the flows between distribution center(s), retailer(s), and markets. Constraint (5) is utilized to ensure that the market demand is fulfilled. Constraint (6) represents the limit in the capacity of supply. In other words, as the nominal capacity of production () in period t decreases, the number of inventory held in period (t-1) should be increased to cover the required number of the supply in period t. Constraint (7) indicates the maximum capacity for holding inventory, and also ensures that only the selected producer(s) can hold the inventory. Constraints (8) and (9) are associated with the capacities of distribution center(s), and retailer(s), respectively. Constraint Eq. (10) illustrates the binary variables. Finally, nonnegative decision variables are presented by Constraint Eq. (11).

A solution approach to solve the FOM

As mentioned previously, different policies (e.g., practice physical distancing, and a self-isolation period for the ones with symptoms of COVID-19) have been announced to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Such policies reduce the production capacity of producers. In this regard, producers should be flexible to fulfill market demand in a timely manner. In Constraint (7), we employ , representing the soft version of applied in flexible constraints, which enable producers to have the inventory more than a specific level due to the limited production capacity. Accordingly, the quantity of holding inventory is supposed to be less than or equal to the maximum capacity of producers for holding inventory. Based on Peidro et al. (2009), can be transformed into the crisp inequality constraint by , where is the satisfaction level of such constraint (i.e., ), and implies the violation of the flexible constraint. In practice, can be either the emergency stock or the number of products purchased from other sources to fulfill market demand in case of operational disturbance. However, holding emergency stock imposes additional costs to the system. On this matter, is used as the unit cost of holding emergency stock. The proposed model can be rewritten as follows:

| 12 |

Subject to:

Constraints (2)–(6), (8)–(11),

| 13 |

The multiplication of by in (12) and (13) causes a mixed-integer nonlinear programming (MINLP) model. To overcome nonlinearity, a nonnegative auxiliary variable of is utilized to transform the MINLP model into the equivalent MILP model. Accordingly, Eqs. (12) and (13) are replaced by Eqs. (14) and (15), respectively. Furthermore, Eqs. (16)–(18) are employed based on a technique introduced by Pishvaee and Khalaf (2016). Equation (16) enforces to be equal to zero if . Otherwise, is equal to if based on Eqs. (17) and (18).

| 14 |

Subject to:

Constraints Eq. (2)–(6), (8)–(11),

| 15 |

| 16 |

| 17 |

| 18 |

Applicability of the proposed FOM

The proposed FOM is investigated using information related to the GTA. As stated, there are 25 municipal areas in the GTA considered as the regional markets. According to the mandatory mask or a face covering By-Law 541–2020, everyone is required to wear a mask in indoor public spaces (exempt children under the age of two and individuals with a medical condition). Therefore, the demand for masks in each region (market) is supposed to be equal to the population of such municipal areas. The population of each region is considered based on the 2016 census of Canada.

The unit cost of transportation is calculated as a function consisting of distances between selected facilities and the price of fuel. Hence, Google Maps is used to estimate the driving distances. The values of other parameters, incorporating into the proposed model, are set based on the case observed in the GTA (see Table 13 in Appendix 1).

Table 13.

Values of the parameters

| P = 5 | Ap = 100,000,000 | Epj = (2,500,000)5*3 |

| W = 7 | Bw = 400,000 | Hpj = (500,000)5*3 |

| R = 25 | Cr = 100,000 | Grj = (750,000)25*3 |

| M = 25 | ej = 4 | Fwj = (3,000,000)7*3 |

| T = 2 | fj = 6 | ρpj = (500,000)5*3 |

| J = 3 | aj = bj = cj = 0.107 | n = 50,000 |

| ψpj = 14 | k = 68 |

*op is calculated in Appendix 2

IBM ILOG CPLEX 12.7.1 is applied to solve the FOM. In the proposed optimization problem, there are 645 constraints, 5,096 nonnegative decision variables, 37 binary variables, and 20,480 nonzero coefficients. The optimal solutions are obtained in 1,023 iterations and the CPU time required to solve the problem is 3 s. Table 3 illustrates the optimal configuration (i.e., the required number of facilities and flows of products) of the mask SCN in the GTA.

Table 3.

Solution for the proposed mask SCN in the GTA

| Objective value ( = 1) | Selected producer | Selected distribution centers | Selected retailers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 191,394,521 | x5: Etobicoke | y2: Mississauga y3: Brampton y6: Concord | v2: Mississauga v3: Bramptonv7: Milton v10: Toronto v12: Vaughan v13: Markham v18: Toronto v21: Pickering v24: Uxbridge |

For all j = 1 to 3; t = 1 to 2.M5 jt = 12,821,414. X5 2jt = 10,548,365, X5 3jst = 1,661,195, X5 6jst = 611,854. Y2 2jt = 2,195,293, Y2 10jt = 1,245,769, Y2 13jt = 1,556,248, Y2 18jt = 4,500,000, Y2 21jt = 965,555, Y2 24jt = 85,500, Y3 3jt = 1,441,159, Y3 7jt = 220,036, Y6 12jt = 611,854. V2 2jt = 1,441,755, V2 5jt = 387,276, V2 6jt = 366,261, V3 3jt = 1,186,089, V3 4jt = 132,871, V3 8jt = 122,200, V7 7jt = 220,036, V10 1jt = 982,166, V10 10jt = 239,115, V10 18jt = 24,487, V12 12jt = 611,854, V13 13jt = 657,274, V13 14jt = 389,654, V13 15jt = 91,582, V13 16jt = 110,779, V13 17jt = 168,280, V13 19jt = 47,934, V13 20jt = 90,745, V18 1jt = 4,475,513, V18 18jt = 24,487, V21 9jt = 183,358, V21 11jt = 318,597, V21 21jt = 23,261,V21 22jt = 183,842, V21 25jt = 256,497, V24 23jt = 43,191, V24 24jt = 42,310

The optimal solutions demonstrate the balance between selected facilities. For instance, the number of masks sent to the distribution center 2 from the producer 5 (i.e., X5 2jt = 10,548,365) is matched by the number of masks shipped from the distribution center 2 to the retailers (i.e., Y2 2jt + Y2 10jt + Y2 13jt + Y2 18jt + Y2 21jt + Y2 24jt = 10,548,365). As indicated in Fig. 3, the optimal network includes 1 producer, 3 sites for distribution centers, and 9 locations for retailers. Figure 4 shows the routes among the selected facilities.

Fig. 3.

The optimal mask SCN design in the GTA

Fig. 4.

The optimal routes among the selected facilities

Table 4 demonstrates the sensitivity analysis conducted on the nominal production capacity (Epj) of the selected producer. As mentioned previously, the Epj may decrease due to many factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. The 1st scenario indicates 30% decrease in the capacity of Producer 5 (E5j), while β5 is equal to 1. Recalling Eq. (13) (i.e., ), it means that Producer 5 is still capable to handle market demand without using its emergency stock .

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis of production capacity

| 1st scenario 30% decrease in E5 j | 2nd scenario 35% decrease in E5 j | 3rd scenario 40% decrease in E5 j | 4th scenario 45% decrease in E5 j | 5th scenario 50% decrease in E5 j |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 196,617,701 | 204,180,072 | 212,430,072 | 220,680,072 | 290,273,898 |

| β5 = 1 | β5 = 0.72 | β5 = 0.40 | β5 = 0.09 | β3 = β5 = 1 |

However, as E5j decreases by 35%, β5 decreases from 1 to 0.72, which means that Producer 5 is not able to fulfill the market demand. Therefore, β5 is reduced to boost the emergency stock in the selected producer (i.e., ). The 5th scenario indicates that the production capacity decreases to 50% of its nominal value. In this case, Producer 5 is not able to handle the market demand even it uses its emergency stock; therefore, Producer 3 is added to the SCN structure.

Figure 5 illustrates the impact of the decrease in E5j on the supply (Mpj2) in period 2 and inventory (Npj1) in period 1. As a result of the decrease in E5j in period 2, Mpj2 decreases as well. Therefore, the number of Npj1 held in period 1 increases to fulfill customer demand (6,410,706) in period 2.

Fig. 5.

The impact of operational risks on supply and inventory

An extension to an MOP model

Three aspects of economic, environmental, and social should be considered for a sustainable SCN design. The 1st objective function was introduced to investigate the economic aspect (i.e., the total cost) of the proposed model. In this section, we define Eqs. (19) and (20) to address the environmental, and social aspects of this facility location problem, respectively. Equation (19) identifies the CO2 emissions stemming from transportation between facilities in the SCN. Furthermore, a capability index (CI) of potential producers to fulfill customer expectations is described by Eq. (20).

| 19 |

| 20 |

The CI (i.e., ) is a qualitative objective required to be measured by expert judgments. A fuzzy QFD model is employed to estimate the CI associated with each potential producer. The QFD process has some privileges compared to other MCDM methods since it provides a systematic approach for producers to enhance customer satisfaction. This technique is utilized in decision analysis, particularly for introducing new products. Many researchers have employed QFD in different industries, such as product design process (Bottani, 2009; Karsak et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2010; Sousa-Zomer & Miguel, 2017; Zaim et al., 2014), information system development (Han et al., 1998), healthcare system (González et al., 2006), energy security management (Shin et al., 2013), employee turnover risks (Wang et al., 2014), vendor assessment and supplier recommendation for business-intelligence systems (Wang, 2015), process performance measurement system (Wieland et al., 2015), project management (Lo et al., 2017), strategic maintenance technique selection (Baidya et al., 2018), transportation sector (Chin et al., 2019; Pakdil & Kurtulmuşoğlu, 2014), and technology development (Gündoğdu & Kahraman, 2020; Haktanır & Kahraman, 2019). In QFD models, DMs play prominent roles to identify the appropriate criteria related to customer expectations and producers’ technical determinants. To compare the potential producers, it is difficult to make a decision based on certain factors. Therefore, fuzzy linguistic scales can be utilized with QFD to aggregate experts’ judgment in uncertain situations.

Chardine-Baumann and Botta-Genoulaz (2014) identified some major areas (e.g., customer issues, societal commitment, and business practices) to consider the social development in the configuration of sustainable SCNs. As indicated in Fig. 6, we consider price and durability, reliability of producers, and environmental compliance as indicators of customer issues, societal commitment, and business practices, respectively. Accordingly, experience, strategic alliances, and flexible manufacturing systems are considered as producers’ technical determinants to fulfill customer expectations. The procedure of producer ranking is provided in Appendix 2.

Fig. 6.

An overall qualitative framework to rank the potential producers based on their capability to fulfill customer expectations

An introduction of an RFMOP model

A sustainable SCN design is a strategic decision since opening or closing a facility imposes considerable costs and time. Therefore, an SCN configuration should be robust to deal with uncertain parameters (e.g., customer demand, transportation costs). Accordingly, we propose a novel RFMOP model to find the best solution that can be immunized for all possible scenarios in a specified bounded box. Model Eq. (M1) is considered to define the solution approach (Ben-Tal & Nemirovski, 2000; Ben-Tal et al., 2005; Pishvaee et al., 2011).

| M1 |

In Model (M1), in which vector and represents variable costs and fixed costs, respectively. implies the market demand and , , are coefficient matrices in constraints. All variables are indicated by vectors (i.e., binary variables) and (i.e., nonnegative decision variables). In this model, all parameters of variable costs and market demand are presumed to be uncertain and vary in specified bounded boxes. Equation (21) shows the typical form of such boxes.

| 21 |

where is the nominal value of the . is the uncertainty scale, and > 0 defines the uncertainty level. In this regard, a specific case of interest is = , therefore deviates from the nominal value to the maximum amount of . Furthermore, Model (M1) includes multiple objectives. The concept of the ε-constraint method is integrated to handle multiple objectives. In the ε-constraint method, the objective with the highest priority is optimized as the main objective function and the remaining objectives are considered as constraints using the ε values as the bound (Collette & Siarry, 2004; Nayak & Ojha, 2019; Roni et al., 2017). Accordingly, Model (M1) can be replaced by Model (M2).

| M2 |

If the bounded box is replaced by a finite set (i.e., extreme points of ), Model (M2) can be transformed into the equivalent tractable version (Ben-Tal et al., 2005; Pishvaee et al., 2011). Equations (22) and (23) are the equivalent tractable versions of the constraints including uncertain parameters and varying in bounded uncertainty sets.

| 22 |

| 23 |

Finally, Model (M3) is written as the tractable form of Model (M2) to handle uncertain parameters as follows:

| M3 |

Accordingly, the robust counterpart of the mask SCN considering uncertain demand and variable costs is equivalent to the following MILP model.

| 24 |

Subject to:

Constraints (2)–(4), (6), (8)–(11), (15)–(18),

| 25 |

| 26 |

| 27 |

| 28 |

| 29 |

| 30 |

| 31 |

| 32 |

| 33 |

| 34 |

| 35 |

| 36 |

| 37 |

| 38 |

Non-dominated solutions of RFMOP model considering different uncertainty levels

In MOP models, there is not a single solution that optimizes all objectives simultaneously. In such cases, several efficient solutions may exist which none of them is dominated (Deb et al., 2002; Mirzapour Al-E-Hashem et al., 2011; Tosarkani & Amin, 2018b). As demonstrated in Tables 5 and 6, we employed the RFMOP model to compute efficient solutions. In this regard, ε2 and ε3 are changed to reach different non-dominated solutions. By comparing Tables 5 and 6, it can be concluded that the uncertainty level has a significant impact on efficient solutions of MOP model. As demonstrated in Model (M3), is less than or equal to incorporating into the objective function. The value of is identified by DMs based on the type of uncertain parameters and the associated risk level.

Table 5.

Non-dominated solutions of proposed RFMOP model ( = 0.15)

| Objective functions | Series 1: = 526,500 = 1,475,000 | Series 2: = 560,500 = 1,474,500 | Series 3: = 535,600 = 1,625,000 | Series 4: = 619,500 = 3,220,500 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cost | 315,394,216 | 220,433,293 | 315,669,473 | 326,882,384 |

| CO2 emissions | 502,540 | 558,240 | 505,580 | 619,500 |

| CI | 1,611,700 | 1,474,500 | 1,625,100 | 3,220,500 |

Table 6.

Non-dominated solutions of proposed RFMOP model ( = 0.30)

| Objective functions | Series 1: = 526,500 = 1,475,000 | Series 2: = 560,500 = 1,474,500 | Series 3: = 535,600 = 1,625,000 | Series 4: = 619,500 = 3,220,500 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cost | 544,306,199 | 347,113,426 | 444,584,884 | 450,698,448 |

| CO2 emissions | 526,340 | 568,450 | 534,930 | 594,700 |

| CI | 2,213,700 | 1,821,900 | 2,213,700 | 3,220,500 |

The value path analysis (VPA) is utilized to investigate the trade-off between non-dominated solutions of RFMOP model. According to the properties of VPA, if two paths (lines) do not intersect, then an inferior line lies entirely below the superior one. In other words, neither of the value paths is dominated, if they have an intersection (Wadhwa and Ravindran, 2007; Afshari et al., 2020).

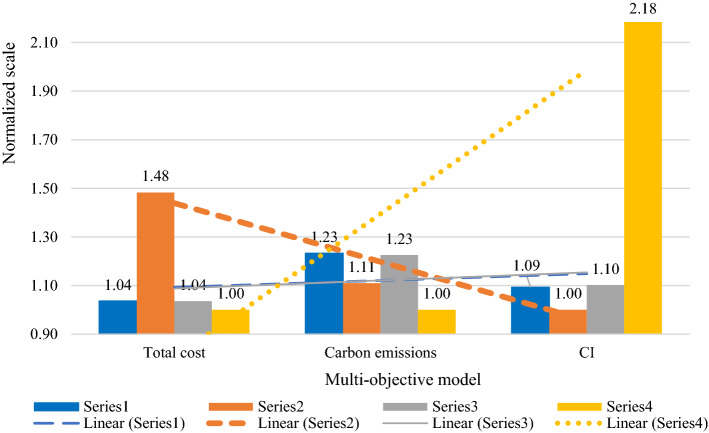

In the RFMOP model, we propose different types of objective functions (i.e., minimizing the total cost and CO2 emissions along with maximizing the CI of potential producers). Therefore, the non-dominated solutions are converted to normalized measurements prior to analyzing the trade-off between them. In the case of minimization, the inferior value of one objective is divided by the corresponding values of same objective among all sets (e.g., normalized scale of z1: 326,882,384 / 315,394,216 = 1.04 and z2: 619,500 / 502,540 = 1.23 for the 1st set of Table 5). However, in the case of maximization, the objective values of a certain objective are divided by the minimum value among all alternatives (e.g., the normalized scale of z3: 1,611,700 / 1,474,500 = 1.09 for the 1st set of Table 5). Accordingly, in both cases of maximizing and minimizing commands, a higher normalized scale leads to a more desirable result. Figures 7 and 8 illustrate value paths (i.e., Linear sets 1, 2, 3, and 4) for the non-dominated solutions of Tables 5 and 6, respectively. In both Figs. 7 and 8, all linear lines (Series 1, 2, 3, and 4) have intersections, and therefore, neither of them is superior based on the properties of VPA. In other words, it is verified that all the solutions are efficient.

Fig. 7.

Value path analysis for the non-dominated solutions of Table 5

Fig. 8.

Value path analysis for the non-dominated solutions of Table 6

Furthermore, the compromise programming method (i.e., a well-known method to solve the MOP model) is also considered to verify the performance of the proposed RFMOP model. This technique is utilized to compute the Pareto efficient solutions in close proximity to objectives’ ideal values (Amin & Baki, 2017). Equation (39) represents the formula where wi and zi* are the weight and ideal values for objective i, respectively. To compute zi*, each objective function is supposed to be solved separately with respect to the defined constraints (i.e., Constraints (2-4), (6), (8-11), (15-18), (25-38)). In this research, there are three objective functions including the total cost (z1), CO2 emissions (z2), and CI of potential producers (z3). Equation (40) indicated the objective function for the multi-objective mask SCN.

| 39 |

| 40 |

Constraints (2)-(4), (6), (8)–(11), (15)–(18), (25)–(38).

To calculate Pareto efficient solutions of the MOP model, several pairs of wi are tested while . Tables 7 and 8 show the non-dominated solutions of the MOP model, while the uncertainty levels are assumed to be equal to 0.15 and 0.30.

Table 7.

Non-dominated solutions of proposed RFMOP model ( = 0.15) using distance technique

| Objectives’ weight | Series 1: = = = 0.33 | Series 2: = 0.8 and = = 0.1 | Series 3: = 0.8 and = = 0.1 | Series 4: = 0.8 and = = 0.1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cost | 316,780,000 | 224,130,000 | 419,830,000 | 670,230,000 |

| CO2 emissions | 499,050 | 580,260 | 528,340 | 822,090 |

| CI | 1,601,600 | 1,474,500 | 1,625,100 | 3,221,500 |

Table 8.

Non-dominated solutions of proposed RFMOP model ( = 0.30) using distance technique

| Objectives’ weight | Series 1: = = = 0.33 | Series 2: = 0.8 and = = 0.1 | Series 3: = 0.8 and = = 0.1 | Series 4: = 0.8 and = = 0.1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cost | 364,880,000 | 362,020,000 | 547,750,000 | 800,970,000 |

| CO2 emissions | 707,100 | 687,250 | 552,080 | 1,851,000 |

| CI | 2,049,700 | 1,666,800 | 2,285,200 | 3,151,800 |

By comparing Table 5 with Table 7 (i.e., non-dominated solutions while = 0.15), and Table 6 with Table 8 (i.e., non-dominated solutions while = 0.30), it can be determined that the proposed RFMOP model performs in proximity to the compromise programming method. However, the proposed RFMOP model enables DMs to compute more Pareto efficient solutions by changing ε2 and ε3 in desirable ranges. For example, DMs may decide to consider all non-dominated solutions in which CO2 emissions are less than 550,000. In this case, they consider 550,000 as the value of ε2 and change ε3 to find different non-dominated solutions. Table 9 indicates several Pareto efficient solutions, while the CO2 emissions are less than the specific level of 550,000.

Table 9.

Non-dominated solutions of proposed RFMOP model ( = 0.15 and = 550,000)

| Objective functions | Series 1: = 550,000 = 2,200,000 | Series 2: = 550,000 = 2,300,000 | Series 3: = 550,000 = 2,400,000 | Series 4: = 550,000 = 2,500,000 | Series 5: = 550,000 = 2,600,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cost | 444,584,767 | 444,586,627 | 444,885,304 | 445,587,759 | 446,568,144 |

| CO2 emissions | 533,950 | 534,950 | 537,870 | 544,730 | 550,000 |

| CI | 2,213,700 | 2,328,200 | 2,400,000 | 2,500,000 | 2,600,000 |

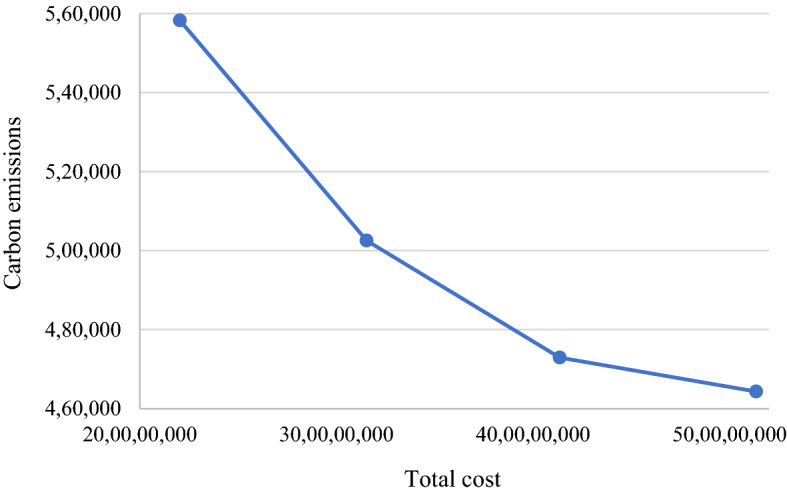

MOP models are utilized to calculate ideal decisions in the presence of a trade-off between some conflicting objectives. As mentioned previously, a variety of Pareto efficient (i.e., non-dominated) solutions may exist for MOP problems. All non-dominated solutions are equally considered (Amin & Zhang, 2012; Deb et al., 2002). It depends on DMs to choose one of them based on their strategies. By comparing the series of non-dominated solutions in Tables 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9, it can be concluded that the value of one objective function cannot be improved without degrading the value of at least one objective function. In this study, three objectives (i.e., the total cost, carbon emissions, and CI of potential producers) are taken into account to design a sustainable mask SCN. To consider the impact of each objective on the others, three bi-objective models are solved. Figure 9 indicates that the total cost of SCN must be increased to reduce the carbon emissions stemming from transportation between facilities. Figure 10 illustrates that SCN must incur more costs to improve the CI associated with potential producers. We provide a discussion to show the reasons, as managerial insights, in Sect. 4. Similarly, as indicated in Fig. 11, the carbon emissions increase as the CI is supposed to be improved.

Fig. 9.

The non-dominated solutions of carbon emissions and total cost

Fig. 10.

The non-dominated solutions of CI and total cost

Fig. 11.

The non-dominated solutions of carbon emissions and CI

Application of simulation to evaluate the performance of RFMOP model

The main feature of the RFMOP model is to support strategic decisions with regard to multiple sources of uncertainty. In this section, simulation is conducted to demonstrate the performance of the proposed RFMOP model compared to the deterministic model in dealing with risks and uncertainty. Since the uncertain parameters are deviated within bounded uncertainty boxes in the proposed RFMOP model, six test problems are generated, using beta distribution, for different uncertainty levels (i.e., φ = 0.15, 0.30, 0.45, 0.60, 0.75, 0.90). The beta distribution is a continuous probability distribution, defined in terms of two parameters of α and β, on the bounded interval (Gupta & Nadarajah, 2004; Johnson, 1997). The mean and variance of beta distribution, on the bounded interval [,], are computed by (41) and (42).

| 41 |

| 42 |

where , , are the minimum, average, and maximum values of the uncertain parameter (i.e., ), respectively. The parameters of α and β can be estimated by Eqs. (43) and (44). For more information, it is recommended to refer to Davis (2008).

| 43 |

| 44 |

The BETAINV (RAND (), , , ,) function is employed to generate random numbers for uncertain parameters (e.g., demand and variable costs) in the bounded interval. For example, in the case of φ = 0.15, and are considered as a 15 percent decrease and increase of (i.e., nominal values of parameters). The generated random numbers (GRNs), associated with each parameter, are replicated 1,000 times. Then, the average and maximum values of each data set are considered to compare the performance of the RFMOP model and deterministic MOP (DMOP) model.

Constraints (25) and (26) are relaxed to indicate the impact of robustness price on the total cost of SCN precisely. To this aim, very large and small values are assigned to and , respectively. Then, the DMOP model is solved considering the average and maximum values of GRNs. Figure 12 demonstrates that the total cost obtained by the RFMOP model is higher than the deterministic multi-objective model solved by average values of GRNs (DMOMA) and is less than the deterministic multi-objective model solved by maximum values of GRNs (DMOMM) (i.e., worst case scenario). Therefore, the application of the RFMOP model leads to the higher total cost, compared to the DMOMA, stemming from handling risks and uncertainty (i.e., cost of robustness) in the SCN. Table 10 demonstrates the performance of the RFMOP model, DMOMA, and DMOMM in terms of the number and locations of producers (i.e., network configuration). As mentioned previously, various policies (e.g., lockdown and self-isolation period) have been considered, in Ontario, to reduce the spread of the COVID-19, which have a significant impact on the capacity levels of producers. In this regard, the RFMOP, DMOMA, and DMOMM models are solved based on different capacity levels of producers. As illustrated in Table 10, only Producers 3 and 5 (x3 and x5) are required to be open based on the RFMOP approach when the uncertainty level is equal to 0.15. However, the number and locations of producers are varied based on the deterministic approach (DMOMA and DMOMM) in the same level of uncertainty level. Therefore, the RFMOP model offers more stable solutions (i.e., network configuration) compared to the deterministic approach leading to the optimal utilization of producers in uncertain situations.

Fig. 12.

Cost of robustness for RFMOP model and deterministic model

Table 10.

Performances of RFMOP and DMOP models

| Uncertainty level | Model | 75% of capacity | 50% of capacity | 25% of capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| φ = 0.15 | RFMOP | x5 * | x3 and x5 | x3 and x5 * |

| DMOMA | x2 and x5 | x3 and x5 | x3, x4 and x5 | |

| DMOMM | x2 and x5 | x3 and x5 | x3, x4 and x5 | |

| φ = 0.30 | RFMOP | x3 and x5 | x3 and x5 | x3 and x5 * |

| DMOMA | x3 and x5 | x3 and x5 | x3, x4 and x5 | |

| DMOMM | x3 and x5 | x3 and x5 | x3, x4 and x5 | |

| φ = 0.45 | RFMOP | x3 and x5 | x3 and x5 | x3 and x5 * |

| DMOMA | x3 and x5 | x3 and x5 | x2, x4 and x5 | |

| DMOMM | x3 and x5 | x3 and x5 | x1, x2, x4 and x5 | |

| φ = 0.60 | RFMOP | x3 and x5 | x3 and x5 * | x3, x4 and x5 * |

| DMOMA | x3 and x5 | x3, x4 and x5 | x1, x3, x4 and x5 | |

| DMOMM | x3 and x5 | x3, x4 and x5 | x1, x3, x4 and x5 | |

| φ = 0.75 | RFMOP | x3 and x5 | x3 and x5 * | x3, x4 and x5 * |

| DMOMA | x3 and x5 | x3, x4 and x5 | x1, x3, x4 and x5 | |

| DMOMM | x3 and x5 | x3, x4 and x5 | x1, x3, x4 and x5 | |

| φ = 0.90 | RFMOP | x3 and x5 | x3 and x5 * | x3, x4 and x5 * |

| DMOMA | x3 and x5 | x3, x4 and x5 | x1, x3, x4 and x5 | |

| DMOMM | x3 and x5 | x3, x4 and x5 | x2, x3, x4 and x5 |

*The lower number of producers is required based on the RFMOP approach

Furthermore, we conduct a sensitivity analysis to evaluate the performance of the RFMOP model and DMOMM based on the mean and standard deviations of . Under different uncertainty levels, five numerical experiments, created by GRNs, are investigated with regard to different capacity levels of producers. As shown in Table 11, the RFMOP model dominates DMOMM in terms of lower standard deviations of solutions in all numerical experiments. With respect to the mean of objective functions, the results suggest that the robust flexible approach has a better performance compared to the deterministic model when the capacity of producers drops from their 100% nominal capacity levels. For further clarification, in the proposed robust flexible approach, producers are able to benefit from the emergency stock owing to the application of the flexible constraint. Therefore, as demonstrated in Table 11, the gap between the mean of the two models becomes larger as the capacity levels of producers decrease to 25% of their nominal capacity.

Table 11.

Computational results of RFMOP model and DMOMM considering different uncertainty levels

| Uncertainty level | 100% of capacity | 75% of capacity | 50% of capacity | 25% of capacity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFMOP | DMOMM | RFMOP | DMOMM | RFMOP | DMOMM | RFMOP | DMOMM | |

| φ = 0.15 | 219,728,627 | 219,859,291 | 236,237,253 | 315,617,187 | 318,680,820 | 319,069,511 | 354,494,885 | 425,381,455 |

| 219,729,411 | 220,846,658 | 236,303,626 | 316,577,670 | 318,656,621 | 320,017,983 | 354,531,667 | 426,516,881 | |

| 219,227,661 | 218,285,036 | 235,160,378 | 313,909,008 | 318,146,940 | 317,399,496 | 353,423,667 | 423,330,920 | |

| 219,375,049 | 218,833,717 | 235,486,938 | 314,494,713 | 318,334,894 | 317,970,943 | 353,778,666 | 424,029,361 | |

| 219,751,043 | 219,189,072 | 236,306,453 | 314,865,798 | 318,679,336 | 318,338,947 | 354,537,700 | 424,463,291 | |

| Mean SD | 219,562,358 | 219,402,755 | 235,898,930 | 315,092,875 | 318,499,722 | 318,559,376 | 354,153,317 | 424,744,382 |

| 244,060 | 988,944 | 538,403 | 1,035,667 | 245,611 | 1,015,866 | 519,692 | 1,238,523 | |

| φ = 0.30 | 257,666,192 | 258,235,563 | 349,238,937 | 349,764,102 | 355,209,234 | 356,650,621 | 411,306,186 | 465,333,348 |

| 257,285,375 | 256,463,955 | 348,917,012 | 348,243,975 | 354,801,878 | 354,857,583 | 410,549,274 | 463,348,296 | |

| 256,913,031 | 255,826,768 | 348,581,648 | 347,804,256 | 354,401,372 | 354,252,694 | 409,881,850 | 462,657,630 | |

| 257,415,610 | 257,459,379 | 349,026,563 | 349,102,363 | 354,935,401 | 355,834,276 | 410,771,967 | 464,403,203 | |

| 257,856,763 | 259,099,081 | 349,408,672 | 350,508,127 | 355,411,653 | 357,520,281 | 411,669,194 | 466,280,970 | |

| Mean SD | 257,427,394 | 257,416,949 | 349,034,566 | 349,084,565 | 354,951,908 | 355,823,091 | 410,835,694 | 464,404,689 |

| 362,719 | 1,317,039 | 316,520 | 1,099,363 | 388,411 | 1,319,445 | 691,376 | 1,462,106 | |

| φ = 0.45 | 307,231,018 | 378,465,134 | 384,377,282 | 382,524,297 | 394,824,334 | 394,096,264 | 502,423,526 | 504,959,981 |

| 307,139,031 | 378,855,532 | 384,301,144 | 383,003,623 | 394,733,626 | 394,711,965 | 502,308,536 | 505,551,576 | |

| 307,219,825 | 377,375,144 | 384,477,057 | 381,289,940 | 394,929,542 | 392,437,997 | 502,501,283 | 503,334,159 | |

| 307,138,795 | 379,740,839 | 384,387,905 | 383,924,715 | 394,846,912 | 395,864,497 | 502,425,493 | 506,707,460 | |

| 307,076,673 | 380,653,108 | 384,200,855 | 384,817,526 | 394,678,116 | 397,036,957 | 502,304,876 | 507,882,961 | |

| Mean SD | 307,161,068 | 379,017,951 | 384,348,849 | 383,112,020 | 394,802,506 | 394,829,536 | 502,392,743 | 505,687,227 |

| 64,128 | 1,247,709 | 103,621 | 1,345,954 | 98,493 | 1,747,485 | 84,576 | 1,728,174 | |

| φ = 0.60 | 421,979,131 | 421,439,424 | 424,505,836 | 426,056,691 | 447,004,869 | 523,066,495 | 564,630,070 | 643,752,018 |

| 422,046,997 | 421,613,651 | 424,567,301 | 426,194,271 | 447,171,102 | 523,239,028 | 564,798,138 | 643,456,454 | |

| 422,695,451 | 422,973,651 | 425,133,829 | 427,506,282 | 448,178,178 | 524,592,460 | 565,809,747 | 645,472,425 | |

| 421,497,773 | 421,151,212 | 424,030,779 | 425,787,557 | 446,155,114 | 522,779,337 | 563,785,446 | 642,855,881 | |

| 422,086,485 | 422,204,917 | 424,585,182 | 426,853,029 | 447,154,124 | 523,832,116 | 564,780,117 | 644,252,346 | |

| Mean SD | 422,061,167 | 421,876,571 | 424,564,585 | 426,479,566 | 447,132,677 | 523,501,887 | 564,760,704 | 643,957,825 |

| 426,410 | 724,183 | 391,430 | 695,110 | 718,849 | 720,961 | 719,455 | 985,998 | |

| φ = 0.75 | 466,216,778 | 469,303,630 | 468,651,408 | 474,072,130 | 512,419,398 | 571,079,930 | 630,921,956 | 701,774,861 |

| 465,778,304 | 468,392,299 | 468,213,246 | 473,160,799 | 512,700,782 | 570,167,802 | 630,215,816 | 700,256,587 | |

| 465,013,087 | 467,104,035 | 467,454,778 | 471,872,535 | 511,205,553 | 568,880,138 | 628,776,793 | 698,190,720 | |

| 464,698,830 | 467,097,984 | 467,131,522 | 471,867,337 | 510,575,006 | 568,873,717 | 628,170,482 | 698,620,068 | |

| 465,989,598 | 468,874,683 | 468,449,166 | 473,643,183 | 512,142,965 | 570,650,543 | 630,635,639 | 700,324,168 | |

| Mean SD | 465,539,319 | 468,154,526 | 467,980,024 | 472,923,197 | 511,808,741 | 569,930,426 | 629,744,137 | 699,833,281 |

| 652,334 | 1,014,324 | 655,950 | 1,014,102 | 889,703 | 1,014,398 | 1,205,888 | 1,445,664 | |

| φ = 0.90 | 513,041,070 | 516,964,488 | 522,118,136 | 527,187,678 | 583,574,428 | 624,122,517 | 700,100,282 | 760,436,496 |

| 514,189,055 | 519,093,563 | 523,467,217 | 529,931,205 | 585,476,146 | 626,868,283 | 701,994,890 | 763,491,934 | |

| 514,721,955 | 519,684,319 | 524,197,464 | 530,586,035 | 586,585,390 | 627,535,755 | 702,104,926 | 764,218,128 | |

| 513,816,525 | 517,882,282 | 523,035,155 | 528,415,557 | 584,843,067 | 625,295,380 | 701,381,542 | 761,823,978 | |

| 513,273,313 | 517,519,404 | 522,422,151 | 527,830,657 | 583,993,605 | 624,831,904 | 700,536,032 | 761,153,794 | |

| Mean SD | 513,808,384 | 518,228,811 | 523,048,025 | 528,790,226 | 584,894,527 | 625,730,768 | 701,223,534 | 762,224,866 |

| 680,930 | 1,127,847 | 829,685 | 1,427,942 | 1,199,403 | 1,426,176 | 884,755 | 1,587,823 | |

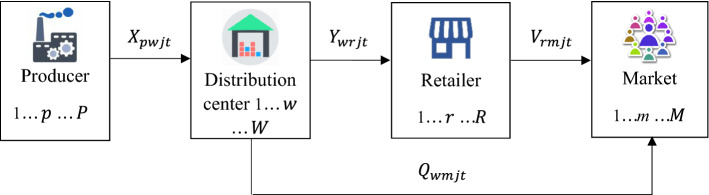

Incorporating online shopping into the proposed RFMOP model

As mentioned previously, this study is inspired by a textile company whose SCN is significantly affected due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This company delivers its products to the markets through distribution centers and retailers. However, online shopping has become more popular among customers to avoid COVID-19. In this section, we investigate the impact of online purchases on the network configuration. As illustrated in Fig. 13, customers may have the option to either purchase products from retailers (i.e., a conventional choice) or place online orders. In this regard, a logistics flow is required to be considered directly from distribution centers to the markets, and the proposed RFMOP model is rewritten as follows:

| 45 |

| 46 |

Fig. 13.

The modified mask SCN considering both conventional and online purchases

Subject to:

Constraints (2)–(4), (6), (8)–(11), (15)–(18), (25)–(38),

| 47 |

| 48 |

| 49 |

| 50 |

| 51 |

| 52 |

Equations (45) and (46) are applied to minimize the total cost and CO2 emissions of the mask SCN considering both conventional and online purchases. In this regard, denotes the number of products delivered directly from distribution center w to market m, is the unit cost of transportation for mask j between distribution centers and markets, and refers to the distance between distribution center w and market m.

Constraints (47) and (48) represent the variation of transportation costs between distribution centers and markets. Constraint (49) ensures that the quantity of products shipping to the distribution center(s) is equal to the number of products sending to the retailers and the number of products sending to the markets . Constraint (50) is applied to guarantee that online orders are fulfilled. Constraint (51) is associated with the capacity of distribution center(s). Finally, Constraint (52) describes the new nonnegative variables required for direct deliveries due to online shopping.

Table 12 demonstrates the comparison between results of the 1st set of Table 8 (i.e., a conventional choice) and the modified version of the proposed RFMOP model, which considered both conventional and online purchases. As online shopping is taken into account the number of distribution centers increases to deliver the products to the customers directly. As a result, the optimal configuration of the conventional SCN changes, and the total distance between selected facilities and markets increases from 1,495 to 2,265.96 km. Accordingly, Table 12 indicates that the values of (i.e., total cost) and (CO2 emissions) degrade while (i.e., CI) improves when online delivery is considered in the configuration of SCN. For further clarification, the impact of growth in online shopping is investigated on the total cost and CO2 emissions separately. As demonstrated in Fig. 14, and increase as the ratio of customers placing online orders grows due to the increase in the total distance between selected facilities and markets.

Table 12.

Comparison of the network configuration in terms of conventional and online deliveries

| Objectives values | Selected producers | Selected distribution centers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st set of Table 8 (w1 = w2 = w3 = 0.33) | 364,880,000 | x1: Mississauga, x5: Etobicoke | y1: Toronto, y2: Mississauga, y3: Brampton, y5: Oakville, y6: Burlington | |

| 707,100 | ||||

| 2,049,700 | ||||

| Considering online purchase (w1 = w2 = w3 = 0.33) * | 375,100,000 | x3: Brampton, x4: Caledon | y1: Toronto, y2: Mississauga, y3: Brampton, y4: Caledon, y5: Oakville, y6: Burlington, y7: Milton | |

| 822,570 | ||||

| 2,078,800 |

*50% of customers place online orders

Fig. 14.

Sensitivity analysis on the ratio of customers placing online orders (Note: The number of customers is fixed, therefore 0.4 implies that 40% of customers place online orders and 60% of customers purchase masks from retailers.)

Managerial insights

In a continuous outbreak, there is a variety of uncertain internal and external factors affecting the configuration of supply chains in the field of healthcare. Internal factors are concerned with the limited capacity of production and transportation, and external ones are associated with the timing and quantities of medical supply required for society. In this regard, an efficient and effective logistics capacity management can support a constant flow of production and mitigate the risk of medical device shortage during a disease outbreak.

The study of sustainable facility location models investigates the systematic determination of the number and location of facilities required to fulfill the market demand with regard to customer requirements, economic benefits, and environmental protection (Tosarkani et al., 2020; Tsai et al., 2020). In this study, the CI of producers has been optimized in addition to the total cost and CO2 emissions for a medical SCN design. Therefore, there are several objectives which may have conflict in practice. This study attempts to offer valuable insights to managers. To this aim, let’s consider the non-dominated solutions of the proposed RFMOP model provided in Table 8. We intend to compare the optimal networks for the 1st set (i.e., = = = 0.33) and the 2nd set (i.e., = 0.8 and = = 0.1) of non-dominated solutions.

Figure 15 illustrates the comparison between the number and location of selected facilities for the two mentioned sets. As indicated in the 2nd set, 1 producer (i.e., x5), 2 distribution centers (i.e., y2, and y3), and 5 retailers (i.e., v2, v3, v10, v14, and v18) are selected when the economic aspect has the highest priority for DMs. However, the SCN configuration is significantly different, if equal weight factors are considered for all three objectives (i.e., 1st set of Table 8). Accordingly, Producer 1, which has the highest priority in the aspect of CI (see Table 23 in Appendix 2), should operate along with Producer 5, and also the number of distribution centers and retailers increases. Therefore, the capability of producers to fulfill the customer requirements (i.e., social aspects) improves from 1,666,700 to 2,049,700. However, the total cost and CO2 emissions of SCN are degraded from 362,020,000 to 364,880,000 and 687,250 to 707,100, respectively, since the total distance between selected facilities increases from 1057 to 1495 km. The proposed MOP model implies that at least the value of one objective must be compromised to improve the values of other objectives. This provides DMs with an opportunity to investigate the impact of each objective on the configuration of facility location models under uncertainty.

Fig. 15.

Changes in SCN configuration due to the allocation of different weight to objectives by DMs

Table 23.

Final ranking of each potential producer

| Producer | FPR | Defuzzified index | Ratio | Ranking | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| l | m | u | ||||

| Producer 1 | 4,528,521 | 72,939,667 | 137,555,000 | 71,674,396 | 50.12% | 1st |

| Producer 2 | 206,063 | 13,349,833 | 52,613,500 | 22,056,465 | 15.42% | 2nd |

| Producer 3 | 166,042 | 12,301,667 | 50,189,792 | 20,885,833 | 14.61% | 3rd |

| Producer 4 | 0 | 6,099,083 | 35,593,708 | 13,897,597 | 9.72% | 5th |

| Producer 5 | 35,479 | 6,497,833 | 36,931,042 | 14,488,118 | 10.13% | 4th |

Conclusions

A multi-objective, multi-echelon, multi-product, multi-period model was proposed for a mask SCN in the GTA. The proposed MOP model included three objectives (i.e., the total cost, generated CO2 emissions, CI of potential producers) to consider sustainability in a facility location problem. The proposed SCN contained multiple facilities such as producers, distribution centers, retailers, and markets. In this study, several challenges were investigated in uncertain circumstances (e.g., ongoing COVID-19 outbreak), such as matching the production capacity of producers with fluctuations in market demand. In this regard, various activities such as planning for production, inventory, and transportation were taken into account in multiple periods.

A successful SCN design should be flexible and robust to fulfill demand during high-impact events, particularly in the field of healthcare. In this study, an FOM was first introduced to utilize the emergency stock in case of a reduction in the capacity levels of producers. Another source of uncertainty was caused by imprecise input parameters (e.g., variable costs and market demand). To handle such types of uncertainty, robust optimization was integrated with the FOM to find the optimal solution that can be guaranteed by all possible scenarios. Pareto efficient (i.e., non-dominated) solutions were computed for the proposed MOP model. As demonstrated by VPA analysis, as the value of one objective function improves, the values of other objective functions degrade in the MOP model. Therefore, it depends on DMs which set of non-dominated solutions should be selected in the ongoing circumstance. A discussion was provided to show how the structure of an SCN might change in terms of considering different non-dominated solutions. However, it is worthy to note that an SCN configuration includes strategic decisions (e.g., third-party selection and capacity decisions), which are impossible to change in the short term. To our knowledge, this study is among the first investigations to propose an integrated RFMOP model to configure an SCN in the field of healthcare. According to our findings, the proposed RFMOP model is an effective solution approach to deal with imprecise parameters.

This research can be extended in different directions. To design a sustainable SCN, CO2 emissions were investigated based on the driving distance. On this matter, incorporating other criteria (e.g., routing plan and traffic condition) to estimate CO2 emissions will offer more precise results. Furthermore, various types of risks (i.e., the uncertainty of input parameters, disruptions in facilities, and transportations) may exist in real problems, and we discussed the first type of risk in this research. Therefore, it is valuable to develop the proposed model to mitigate the impact of disruptions on SCNs. In this research, the values of demand are assumed to be equal to the population of each specific region due to the mandatory face mask policy. However, demand will change after the outbreak. Therefore, developing a forecasting approach for market demand can be a future research direction for this study.

Appendix 1: Parameters

See Table 13.

Appendix 2: The QFD model

In this study, the QFD model is employed to prioritize producers based on qualitative factors. As indicated in Fig. 16, there are different sections in the QFD model (e.g., customer requirements, technical determinants).

Fig. 16.

A: customer expectations (i.e., voice of customers), (WHATs) B: priority of customer requirements, C: technical determinants (i.e., voice of the organization), (HOWs), D: relationship matrix HOWs vs WHATs, E: correlation between technical determinants, F: priority of technical determinants

As indicated in Fig. 6, various criteria are defined to consider both voices of customers and producers. In this study, four qualitative criteria (i.e., price, durability, reliability, and environmental compliance) are identified to represent the customer expectations and three technical criteria (i.e., experience, strategic alliances, and flexible manufacturing system) are considered to evaluate the capability of producers, respectively. Following phases are taken into account to rank the potential producers based on their capability to fulfill customer expectations.

Phase 1: As indicated in Table 14, the following linguistic scale (i.e., Fig. 17) is utilized to rank the criteria based on the expert judgment.

Table 14.

Ranking of criteria

| WHATs | 1st DM | 2nd DM | 3rd DM |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | VH | M | MH |

| C2 | M | M | H |

| C3 | H | H | H |

| C4 | MH | MH | MH |

Fig. 17.

Very Low (VL) = (0,0,1), Low (L) = (0,1,3), Medium Low (ML) = (1,3,5), Medium (M) = (3,5,7), Medium High (MH) = (5,7,9), High (H) = (7,9,10), Very High (VH) = (9,10,10)

Phase 2: DMs have different levels of experience that must be considered in the judgment. Therefore, it is proposed to determine the weight factors for DMs. In this study, we consider experience index (i.e., poor = (0, 0, 10), normal = (5, 10, 15), perfect = (10, 20, 20)). In this case, there are three DMs. αn (i.e., n = 1, 2, 3) is defined as the weight of DMn. The 1st and 3rd DMs have the perfect level of experience, while the 2nd one has a normal level of experience. Then, (b.1) is employed to aggregate the weights assigned by DMs. The results are provided in Table 15.

| b.1 |

Table 15.

The obtained aggregated weights

| WHATs | α1 * wi1 | α2 * wi2 | α3 * wi3 | Aggregated weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | (90, 200, 200) | (15, 50, 105) | (50, 140, 180) | (155, 390, 485) |

| C2 | (30, 100, 140) | (15, 50, 105) | (70, 180, 200) | (115, 330, 445) |

| C3 | (70, 180, 200) | (35, 90, 150) | (70, 180, 200) | (175, 450, 550) |

| C4 | (50, 140, 180) | (25, 70, 135) | (50, 140, 180) | (125, 350, 495) |

where I and N are the numbers of customer expectations and DMs, respectively.

Phase 3: As illustrated in Table 16, the linguistic scale is utilized by all three DMs to evaluate the impact of technical determinants (i.e., HOWs) on customer expectations (i.e., WHATs).

Table 16.

Relationship matrix HOWs vs WHATs

| HOWs WHATs | C5 | C6 | C7 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st DM | 2nd DM | 3rd DM | 1st DM | 2nd DM | 3rd DM | 1 st DM | 2 nd DM | 3 rd DM | |

| C1 | H | VH | H | H | MH | MH | VH | H | VH |

| C2 | MH | M | H | ML | M | H | H | H | H |

| C3 | MH | H | MH | M | H | H | MH | MH | MH |

| C4 | MH | M | M | VH | VH | VH | H | H | H |

Phase 4: (b.2) and (b.3) are employed to compute the relationship matrix between customer expectations (WHATs) and technical determinants (HOWs). Table 17 indicates the results of the relationship matrix.

| b.2 |

| b.3 |

Table 17.

Results of relationship matrix WHATs and HOWs

| HOWs WHATs | C5 | C6 | C7 | Aggregated weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | (185, 460, 550) | (145, 390, 515) | (215, 490, 550) | (155, 390, 485) |

| C2 | (135, 370, 485) | (95, 290, 405) | (175, 450, 550) | (115, 330, 445) |

| C3 | (135, 370, 510) | (135, 370, 490) | (125, 350, 495) | (175, 450, 550) |

| C4 | (95, 290, 425) | (225, 500, 550) | (175, 450, 550) | (125, 350, 495) |

| f1: (19,925, 142,375, 243,363) | f2: (21,288, 147,325, 242,938) | f3: (24,300, 163,650, 264,000) | ||

where is the aggregated weight between WHATs and HOWs. J is the number of HOWs and is the weight associated with HOWs.

Phase 5: (b.4) is applied to estimate the capability () of each potential producer p to perform a technical determinant j. Tables 18, 19, 20, 21, and 22 illustrate the results.

| b.4 |

Table 18.

The capability of producer 1 to perform technical determinants

| WHATs | 1st DM | 2nd DM | 3rd DM | Aggregated weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C5 | VH | VH | VH | (225, 500, 550) |

| C6 | VH | VH | H | (205, 480, 550) |

| C7 | H | H | VH | (195, 470, 550) |

Table 19.

The capability of producer 2 to perform technical determinants

| WHATs | 1st DM | 2nd DM | 3rd DM | Aggregated weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C5 | ML | ML | L | (15, 110, 235) |

| C6 | L | ML | ML | (15, 110, 235) |

| C7 | L | L | L | (0, 50, 165) |

Table 20.

The capability of producer 3 to perform technical determinants

| WHATs | 1st DM | 2nd DM | 3rd DM | Aggregated weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C5 | ML | ML | ML | (25, 150, 275) |

| C6 | L | L | L | (0, 50, 165) |

| C7 | L | L | L | (0, 50, 165) |

Table 21.

The capability of producer 4 to perform technical determinants

| WHATs | 1st DM | 2nd DM | 3rd DM | Aggregated weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C5 | L | VL | L | (0, 40, 135) |

| C6 | L | L | VL | (0, 30, 125) |

| C7 | L | L | L | (0, 50, 165) |

Table 22.

The capability of producer 5 to perform technical determinants

| WHATs | 1st DM | 2nd DM | 3rd DM | Aggregated weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C5 | VL | L | L | (0, 30, 125) |

| C6 | L | ML | L | (5, 70, 195) |

| C7 | L | L | VL | (0, 30, 125) |

Phase 6: (b.5) is employed to calculate the final ranking of each potential producer regarding customer expectation and technical determinants. The final results are provided in Table 23.

| b.5 |

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Afshari H, Tosarkani BM, Jaber MY, Searcy C. The effect of environmental and social value objectives on optimal design in industrial energy symbiosis: A multi-objective approach. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 2020;158:104825. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akbari AA, Karimi B. A new robust optimization approach for integrated multi-echelon, multi-product, multi-period supply chain network design under process uncertainty. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 2015;79(1–4):229–244. doi: 10.1007/s00170-015-6796-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alavi SH, Jabbarzadeh A. Supply chain network design using trade credit and bank credit: A robust optimization model with real world application. Computers and Industrial Engineering. 2018;125:69–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cie.2018.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ameknassi L, Aït-Kadi D, Rezg N. Integration of logistics outsourcing decisions in a green supply chain design: A stochastic multi-objective multi-period multi-product programming model. International Journal of Production Economics. 2016;182:165–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.08.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amin SH, Baki F. A facility location model for global closed-loop supply chain network design. Applied Mathematical Modelling. 2017;41:316–330. doi: 10.1016/j.apm.2016.08.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]