Abstract

目的

探讨乳头状肾细胞癌(papillary renal cell carcinoma,pRCC)的临床病理特征和预后特点。

方法

回顾性分析2012年5月至2021年5月北京大学第三医院泌尿外科收治的114例pRCC患者的临床资料,包括91例男性和23例女性。所有病例均为手术患者,病理诊断明确,随访数据完整。采用Kaplan-Meier法绘制生存曲线并通过log-rank检验分析患者临床病理特征与生存时间的关系,使用Cox比例风险回归模型分析影响患者无进展生存率的因素。

结果

114例患者平均年龄(57.3±12.6)岁。肿瘤位于左肾49例,右肾65例。48例行根治性肾切除术,66例行肾部分切除术。1型pRCC 42例,2型72例,肿瘤平均最大径为(5.5±3.6) cm。肿瘤分期pT1a期52例,pT1b期22例,pT2期4例,pT3期33例,pT4期3例。2016年世界卫生组织/国际泌尿病理学会(World Health Organization / International Society of Urological Pathology,WHO/ISUP)分级Ⅰ级13例,Ⅱ级44例,Ⅲ级51例,Ⅳ级6例。114例患者中34例伴有脉管癌栓,30例伴淋巴结转移,3例伴肾上腺转移。患者术后中位随访时间为22个月,3年无进展生存率为95.6%。1型和2型pRCC患者在年龄(P=0.046)、体重指数(P=0.008)、手术方式(P=0.001)、肿瘤最大径(P < 0.001)、脉管癌栓(P < 0.001)、淋巴结转移(P < 0.001)、pT分期(P < 0.001)和核分级(P < 0.001)方面差异均有统计学意义。1型和2型pRCC的3年无进展生存率分别为100%和69.4%,1型预后明显优于2型(P=0.003)。2型pRCC患者的单因素分析结果显示,pT分期(P < 0.001)、脉管癌栓(P < 0.001)和淋巴结转移(P < 0.001)与其预后紧密相关;多因素分析显示,脉管癌栓为2型pRCC无进展生存率的独立预后因素(P=0.001)。行根治性肾切除术的pRCC患者的单因素分析结果显示,pT分期(P=0.006)、脉管癌栓(P=0.001)和淋巴结转移(P=0.008)是影响其预后的显著因素,进一步多因素分析显示只有脉管癌栓是其无进展生存率的独立预后因素(P=0.006)。

结论

2型pRCC比1型pRCC发病率更高,淋巴结转移更易出现,pT分期更晚,核分级更高。在2型pRCC和根治性切除术后的pRCC患者中,脉管癌栓是其独立预后因素。

Keywords: 乳头状肾细胞癌, 临床特征, 临床病理学, 预后

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the clinicopathological features and prognostic characteristics of papillary renal cell carcinoma (pRCC).

Methods

The clinical data of 114 patients with pRCC, including 91 males and 23 females, admitted to the Department of Urology, Peking University Third Hospital from May 2012 to May 2021 were retrospectively analyzed. All the cases were operated patients with clear pathological diagnosis and complete follow-up data. The log-rank test was used to analyze the relationship between the patients' clinicopathological characteristics and survival time, the Kaplan-Meier method to draw survival curves, and the Cox regression model for univariate and multifactorial analysis.

Results

The mean age of the 114 patients was (57.3±12.6) years. The tumors were located in the left kidney in 49 cases and in the right kidney in 65 cases. In the study, 48 radical nephrectomies and 66 partial nephrectomies were performed, 42 cases were type 1 and 72 cases were type 2, and the mean maximum tumor diameter was (5.5±3.6) cm. pT1a stage 52 cases, pT1b stage 22 cases, pT2 stage 4 cases, pT3 stage 33 cases, and pT4 stage 3 cases were staged. According to the World Health Organization / International Society of Urological Pathology (WHO/ISUP), there were 13 cases of gradeⅠ, 44 cases of grade Ⅱ, 51 cases of grade Ⅲ, and 6 cases of grade Ⅳ. And 34 of the 114 patients had vascular cancer embolism, 30 cases had lymph node metastasis, and 3 cases had adrenal metastasis. The median follow-up time after surgery was 22 months, and the 3-year progression-free survival rate was 95.6%. The patients with type 1 and type 2 pRCC showed statistically significant differences in age (P=0.046), body mass index (P=0.008), surgical approach (P=0.001), maximum tumor diameter (P < 0.001), vascular cancer embolism (P < 0.001), lymph node metastasis (P < 0.001), pT stage (P < 0.001), and nuclear grade (P < 0.001). The 3-year progression-free survival rates for type 1 and type 2 pRCC were 100% and 69.4%, respectively, with type 1 having a significantly better prognosis than with type 2 (P=0.003). Univariate analysis of the patients with type 2 pRCC showed that pT stage (P < 0.001), vascular cancer embolism (P < 0.001) and lymph node metastasis (P < 0.001) were strongly associated with their prognosis. Multifactorial analysis showed that vascular cancer embolism was an independent prognostic factor for progression-free survival in type 2 pRCC (P=0.001). Univariate analysis of the pRCC patients undergoing radical nephrectomy showed that pT stage (P=0.006), vascular cancer embolism (P=0.001), and lymph node metastasis (P=0.008) were significant factors affecting their prognosis, and further multifactorial analysis showed that only vascular cancer embolism was an indepen-dent prognostic factor for their progression-free survival (P=0.006).

Conclusion

Type 2 pRCC has more morbidity, more lymph node metastases, more advanced pT stage, and higher pathologic grading than type 1 pRCC. The presence of vascular cancer embolism is an independent prognostic factor in patients with type 2 pRCC and pRCC undergoing radical nephrectomy.

Keywords: Papillary renal cell carcinoma, Clinical features, Clinical pathology, Prognosis

肾细胞癌是全球第13位最常见的恶性肿瘤,其发病率呈上升趋势[1-3]。乳头状肾细胞癌(papillary renal cell carcinoma,pRCC)是第二常见的肾癌病理亚型,国外文献报道其占肾癌的10%~15%[4]。根据肿瘤细胞的排列层次和细胞核分级,pRCC被分为1型和2型。有文献显示,病理分型为2型、行根治性肾切除术和pT分期较高的患者组织学恶性程度更高[4-5]。但目前国内文献对于上述恶性程度较高的pRCC鲜有针对性的预后分析。

本研究回顾性分析了北京大学第三医院泌尿外科2012年5月至2021年5月诊治的114例pRCC的病例资料,并从病理分型、pT分期、手术方式的角度对患者的临床特点进行分析,从而探讨其临床病理特征,为临床诊疗提供参考。

1. 资料与方法

1.1. 一般资料

本研究的研究对象为2012年5月至2021年5月于北京大学第三医院泌尿外科进行手术治疗的114例pRCC患者,数据来源为北京大学第三医院泌尿外科临床数据随访资料库。其中所有患者均接受肾部分切除术或根治性肾切除术且术后病理诊断为pRCC,排除嗜酸细胞和透明细胞乳头状肾细胞癌。提取性别、年龄、pT分期、核分级及有无淋巴结转移、肾上腺转移、脉管癌栓等临床病理特征相关数据,其中pT分期参照2017年美国癌症联合会(American Joint Committee on Cancer,AJCC)分期标准,核分级以2016年世界卫生组织/国际泌尿病理学会(World Health Organization/International Society of Urological Pathology,WHO/ISUP)分级系统为标准。

1.2. 随访

记录病例的临床随访资料、术后辅助治疗方式、是否存在肿瘤复发和远处转移。采用无进展生存期作为预后评价指标,即以患者接受治疗作为起点,以观察到疾病进展或者发生因任何原因的死亡作为终点。对于死亡前就已经失访的患者,将末次随访时间作为终点。

1.3. 统计学方法

采用SPSS 26.0统计软件处理数据。计量资料用均数±标准差表示,分类变量用数量及百分比表示。二分类变量组间比较采用精确Fisher检验,多分类变量组间比较采用似然比检验。采用Kaplan-Meier法绘制生存曲线并通过log-rank检验分析患者临床病理特征与生存时间的关系,使用Cox比例风险回归模型分析影响患者无进展生存率的因素。P < 0.05为差异具有统计学意义,单因素分析中P < 0.2的变量纳入多因素分析。

2. 结果

2.1. 总体特征

本研究共纳入114例患者,占同期本中心全部肾癌患者的6.8%,有30例(26.3%)在确诊时即已发生转移。其中男性91例(79.8%),女性23例(20.2%),患者平均年龄(57.3±12.6)岁,平均体重指数(body mass index,BMI)(25.1±3.1) kg/m2,肿瘤平均最大径(5.5±3.6) cm,详见表 1。随访时间为1~105个月,中位随访时间为22个月,死亡11例,存活103例。3年无进展生存率为95.6%,5年无进展生存率为91.2%。

表 1.

114例pRCC患者的基本临床病理特征

Clinicopathological features of 114 pRCC patients

| Items | Value |

| Gender, n(%) | |

| Male | 91 (79.8) |

| Female | 23 (20.2) |

| Age/years, x±s | 57.3±12.6 |

| BMI/(kg/m2), x±s | 25.1±3.1 |

| Tumor location, n(%) | |

| Left | 49 (43.0) |

| Right | 65 (57.0) |

| Surgical method, n(%) | |

| Partial nephrectomy | 66 (57.9) |

| Radical nephrectomy | 48 (42.1) |

| Maximum tumor diameter/cm, x±s | 5.5±3.6 |

| pT stages, n(%) | |

| T1a | 52 (45.6) |

| T1b | 22 (19.3) |

| T2 | 4 (3.5) |

| T3 | 33 (28.9) |

| T4 | 3 (2.6) |

| Nuclear grade, n(%) | |

| Ⅰ | 13 (11.4) |

| Ⅱ | 44 (38.6) |

| Ⅲ | 51 (44.7) |

| Ⅳ | 6 (5.3) |

| Vascular cancer embolism, n(%) | |

| Yes | 34 (29.8) |

| No | 80 (70.2) |

| Adrenal metastasis, n(%) | |

| Yes | 3 (2.6) |

| No | 111 (97.4) |

| Lymph node metastasis, n(%) | |

| Yes | 30 (26.3) |

| No | 84 (73.7) |

| Symptoms, n(%) | |

| Osphyalgia | 17 (14.9) |

| Hematuria | 19 (16.7) |

| Physical examination found | 78 (68.4) |

2.2. 1型与2型pRCC临床病理特征比较

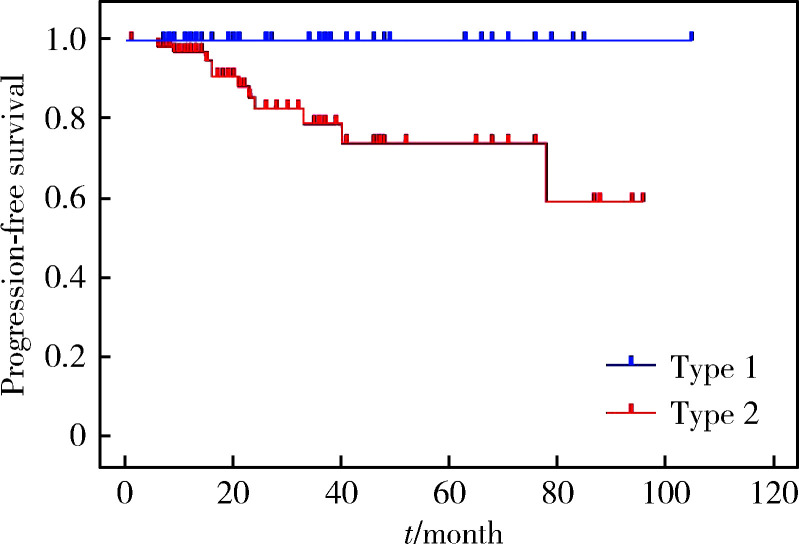

本组患者中,1型pRCC共42例,2型pRCC共72例,两者临床病理特征比较见表 2。1型和2型pRCC患者在年龄(P=0.046)、BMI(P=0.008)、手术方式(P=0.001)、肿瘤最大径(P < 0.001)、有无脉管癌栓(P < 0.001)、有无淋巴结转移(P < 0.001)、pT分期(P < 0.001)和核分级(P < 0.001)方面差异有统计学意义。1型和2型pRCC的3年无进展生存率分别为100%和69.4%,1型显著优于2型,差异有统计学意义(P=0.003,图 1)。

表 2.

1型和2型pRCC患者的临床病理特征比较

Comparison of the clinicopathological features of type 1 and type 2 pRCC

| Items | Type 1 | Type 2 | P |

| Gender, n | 0.231 | ||

| Male | 36 | 55 | |

| Female | 6 | 17 | |

| Age/years, x±s | 54.1±11.5 | 59.0±12.9 | 0.046 |

| BMI/(kg/m2), x±s | 26.1±2.9 | 24.5±3.1 | 0.008 |

| Tumor location, n | 0.421 | ||

| Left | 16 | 33 | |

| Right | 26 | 39 | |

| Surgical method, n | 0.001 | ||

| Partial nephrectomy | 33 | 33 | |

| Radical nephrectomy | 9 | 39 | |

| Maximum tumor diameter/cm, x±s |

3.55±2.30 | 6.63±3.69 | < 0.001 |

| Vascular cancer embolism, n | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 1 | 33 | |

| No | 41 | 39 | |

| Lymph node metastasis, n | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 0 | 30 | |

| No | 42 | 42 | |

| Adrenal metastasis, n | 0.463 | ||

| Yes | 0 | 3 | |

| No | 42 | 69 | |

| pT stages, n | < 0.001 | ||

| T1a | 28 | 24 | |

| T1b | 10 | 12 | |

| T2 | 2 | 2 | |

| T3 | 1 | 32 | |

| T4 | 1 | 2 | |

| Nuclear grade, n | < 0.001 | ||

| Ⅰ | 13 | 0 | |

| Ⅱ | 24 | 20 | |

| Ⅲ | 5 | 46 | |

| Ⅳ | 0 | 6 | |

| Symptoms, n | 0.002 | ||

| Osphyalgia | 3 | 14 | |

| Hematuria | 2 | 17 | |

| Physical examination found | 37 | 41 |

图 1.

1型和2型pRCC患者术后无进展生存曲线

Progression-free survival curves in patients with type 1 and type 2 pRCC after surgery

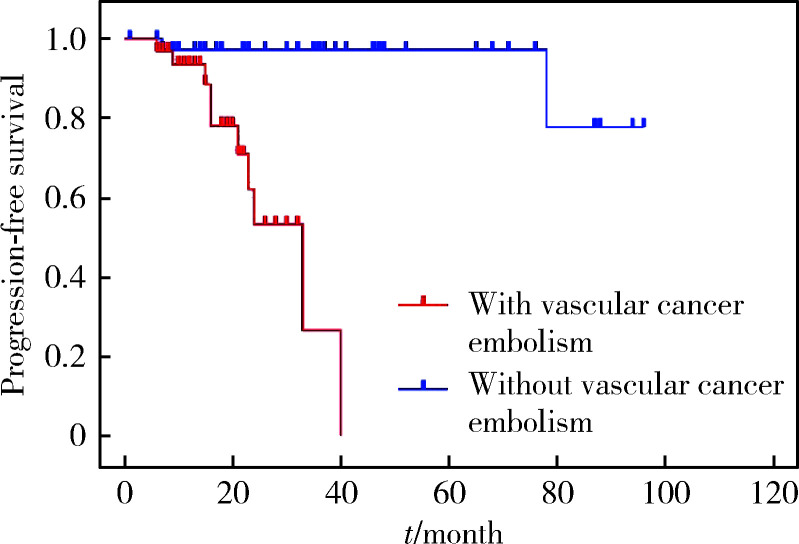

2.3. 2型pRCC患者预后及其影响因素

影响2型pRCC患者预后的单因素和多因素分析结果见表 3。单因素分析结果显示,pT分期、脉管癌栓和淋巴结转移与2型pRCC患者的预后紧密相关;多因素分析显示,脉管癌栓为2型pRCC无进展生存率的独立预后因素。有无脉管癌栓的2型pRCC患者无进展生存曲线见图 2。

表 3.

2型pRCC患者预后相关的单因素和多因素分析

Univariate and multifactorial analysis of the prognosis associated with type 2 pRCC patients

| Items | Univariate analysis | Multifactorial analysis (P) |

||

| HR | 95%CI | P | ||

| pRCC, papillary renal cell carcinoma; BMI, body mass index; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval. | ||||

| Gender (Male/Female) | 0.296 | 0.038-2.295 | 0.215 | |

| BMI (>24.9 kg/m2/≤24.9 kg/m2) | 0.913 | 0.290-2.871 | 0.876 | |

| Tumor location (Left/Right) | 0.799 | 0.256-2.498 | 0.700 | |

| Surgical method (Radical/Partial) | 3.316 | 0.886-12.417 | 0.055 | 0.100 |

| pT stages (T3-4/ T1-2) | 12.495 | 2.605-59.929 | < 0.001 | 0.584 |

| Nuclear grade (Ⅲ-Ⅳ / Ⅰ-Ⅱ) | 1.333 | 0.391-4.541 | 0.641 | |

| Vascular cancer embolism (Yes/No) | 34.301 | 3.983-295.376 | < 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Lymph node metastasis (Yes/No) | 15.257 | 2.767-84.121 | < 0.001 | 0.558 |

| Adrenal metastasis (Yes/No) | 4.009 | 0.488-32.905 | 0.274 | |

图 2.

有无脉管癌栓的2型pRCC患者无进展生存曲线

Progression-free survival curves in patients with type 2 pRCC with and without vascular cancer embolism

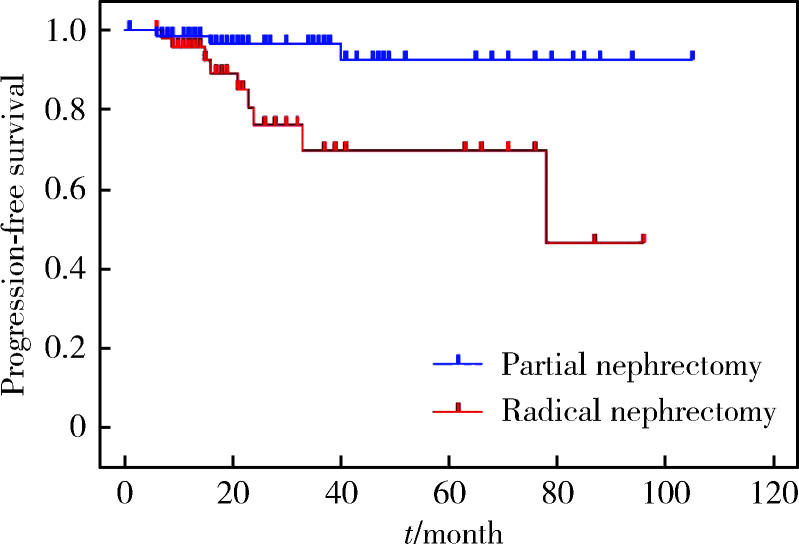

2.4. 行根治性肾切除术的pRCC患者的预后及其影响因素

肾部分切除术和根治性肾切除术的pRCC患者无进展生存曲线(图 3)提示,根治性肾切除术患者的无进展生存率低于肾部分切除术患者(P=0.004)。单因素分析结果显示,pT分期、脉管癌栓和淋巴结转移是根治性肾切除术后pRCC患者预后的显著影响因素;多因素分析表明,脉管癌栓是根治性肾切除术后患者无进展生存率的独立预后因素(表 4)。

图 3.

肾部分切除术和根治性肾切除术的pRCC患者无进展生存曲线

Progression-free survival curves in pRCC patients undergoing partial nephrectomy and radical nephrectomy

表 4.

根治性肾切除术后pRCC患者预后的单因素和多因素分析

Univariate and multifactorial analysis of the prognosis of patients with pRCC after radical nephrectomy

| Items | Univariate analysis | Multifactorial analysis (P) |

||

| HR | 95%CI | P | ||

| Abbreviations as in Table 3. | ||||

| BMI (>24.9/≤24.9 kg/m2) | 0.655 | 0.173-2.477 | 0.537 | |

| Tumor location (Left/Right) | 0.984 | 0.258-3.759 | 0.982 | |

| Nuclear grade (Ⅲ-Ⅳ / Ⅰ-Ⅱ) | 2.300 | 0.494-10.722 | 0.275 | |

| pT stages (T3-4/ T1-2) | 7.412 | 1.503-36.540 | 0.006 | 0.452 |

| Vascular cancer embolism (Yes/No) | 21.445 | 2.455-187.305 | 0.001 | 0.006 |

| Lymph node metastasis (Yes/No) | 10.386 | 1.241-86.938 | 0.008 | 0.499 |

| Adrenal metastasis (Yes/No) | 3.380 | 0.392-29.172 | 0.334 | |

| pRCC (Type 1 / Type 2) | 0.863 | 0.331-2.674 | 0.132 | 0.493 |

2.5. 高pT分期(T3~4)pRCC患者预后影响因素

单因素分析发现,性别、BMI、肿瘤位置、手术方式、核分级、有无脉管癌栓、是否淋巴结转移、是否肾上腺转移均不是高pT分期pRCC患者预后的显著影响因素(表 5)。

表 5.

高pT分期pRCC患者预后的单因素分析

Univariate analysis of prognosis in pRCC patients with high pT stage

| Items | HR | 95%CI | P |

| Abbreviations as in Table 3. | |||

| Gender (male/female) | 0.281 | 0.035-2.270 | 0.163 |

| BMI (>24.9 / ≤24.9 kg/m2) | 1.379 | 0.385-4.944 | 0.626 |

| Tumor location (Left/Right) | 1.359 | 0.361-5.113 | 0.649 |

| Surgical method (Radical/Partial) | 1.815 | 0.465-7.079 | 0.375 |

| Nuclear grade (Ⅲ-Ⅳ / Ⅰ-Ⅱ) | 1.009 | 0.242-4.205 | 0.990 |

| Vascular cancer embolism (Yes/No) | 35.011 | 0.015-82 945.630 | 0.058 |

| Lymph node metastasis (Yes/No) | 1.994 | 0.395-10.068 | 0.376 |

| Adrenal metastasis (Yes/No) | 1.931 | 0.230-16.217 | 0.575 |

3. 讨论

pRCC是原发于肾小管上皮的恶性肿瘤,由Mancilla-Jimenez等[6]在1976年首次报道。本组pRCC病例约占同期本中心全部肾癌病例的6.8%,与文献报道的10%~15%[4]存在差距。虽然pRCC的2个主要形态变异最早在1986年Thoenes等[7]的肾肿瘤分类中即被描述,但直到1997年Delahunt等[8]才根据形态学和免疫组织化学特征将pRCC分为2个亚型:1型pRCC的乳头被单层或双层小细胞所覆盖,胞浆稀薄,细胞核小且呈卵圆形,核仁不明显;2型pRCC有大量嗜酸性胞浆,核呈假分层或不规则分层,细胞通常有大的球形核,核仁突出。国外研究报道,pRCC在男性中发病率更高,男女比例可达1.5:1~2:1[2, 9];本组患者男性占79.8%,男女比例接近3.95:1。一项针对242例中国pRCC患者的多中心回顾性研究显示,2型患者更为多见(1型和2型比例约为1:1.95)[10],与本研究近似(1型和2型比例约为1:1.71),但国外的研究却提示1型比2型更为常见,二者比例接近3:1[11]。国内外1型和2型pRCC发病率的差异需要更大样本量的研究以进一步验证。

国内有研究报道,pRCC患者的发病年龄为53~57岁,肿瘤最大径在5.2~5.6 cm[12-13]。本组平均发病年龄(57.3±12.6)岁,肿瘤平均最大径(5.5±3.6) cm,与上述研究接近。由于pRCC的临床症状并无特异性,大多数pRCC患者是在体检中发现,本组患者经体检发现的pRCC占全部患者的68.4%,其余患者则表现为腰痛(14.9%)和血尿(16.7%)。

国内外多项研究对1型和2型pRCC的临床病理特征和预后因素进行了总结分析,但目前的结论仍存在一定的争论。一项国内研究显示,与1型pRCC相比,2型pRCC肿瘤最大径更长(P < 0.001),此外,2型pRCC可能有更晚期的肿瘤分期(P < 0.001)和更高的WHO/ISUP分级(P < 0.001)[10]。一项韩国的研究发现,2型pRCC患者的发病年龄比1型更高,且差异有统计学意义,同时2型pRCC患者的肿瘤分级更高,但两者在性别、BMI等方面的差异并不具有统计学意义[14]。Pan等[15]的研究纳入了102例pRCC患者,单因素分析提示,病理亚型、临床症状、TNM分期、WHO/ISUP分级和手术方式均会影响pRCC患者的预后,进一步的多因素分析提示TNM分期是pRCC预后的独立危险因素。Sakov等[16]对395例pRCC患者进行回顾性研究,得出临床症状、有无脉管癌栓、TNM分期、Fuhrman分级、pRCC分型均与患者的预后有关,且与pRCC分型相比,Fuhrman分级与预后的相关性更强。

本研究结果显示,1型和2型pRCC患者在年龄(P=0.046)、BMI(P=0.008)、手术方式(P=0.001)、肿瘤最大径(P < 0.001)、有无脉管癌栓(P < 0.001)、有无淋巴结转移(P < 0.001)、pT分期(P < 0.001)和核分级(P < 0.001)方面差异均有统计学意义,其中部分结果与既往研究相似,但本组不同分型pRCC患者间年龄存在显著差异的结果与既往研究不同,需进一步增加样本量进行验证。结合现有文献报道,相较于1型pRCC,2型pRCC与脉管癌栓、较高的核分级、较高的TNM分期的相关性更大。

既往研究表明,1型和2型pRCC患者的1年无进展生存率分别为98.8%和91.9%,5年无进展生存率分别为95.5%和81.3%[10];Ku等[17]对70例pRCC患者的回顾性研究显示,1型和2型pRCC患者的3年无进展生存率分别为96.4%和62.7%。本组1型和2型pRCC患者的3年无进展生存率分别为100%和69.4%,与上述文献一致,均表明2型pRCC的预后更差。因此,我们进一步对2型pRCC患者预后影响因素进行了分析,单因素分析显示pT分期和脉管癌栓与2型pRCC患者的预后紧密相关,多因素分析显示脉管癌栓为影响2型pRCC无进展生存率的独立因素。

手术方式也是影响pRCC患者预后的重要因素。目前的研究认为,对于不适合进行肾部分切除的T1a期、T1b期及T2期肾细胞癌,根治性肾切除术是其首选治疗方式,而肾部分切除术仅适用于部分T1a期肾细胞癌[18]。Fernandes等[19]的研究也认为,对于T1期pRCC应尽可能行肾部分切除术,而T2期则应行根治性肾切除术。2型pRCC相比于1型pRCC的T分期更高,肿瘤分级更高,且更具有侵袭性,因此,2型pRCC患者行根治性肾切除术的可能性更大,这可能会对预后影响因素分析中手术方式和分型的关系造成偏倚。本研究结果表明,手术方式对于pRCC患者的预后具有影响(P=0.004),但随后对2型pRCC患者的多因素分析结果表明,手术方式不是其独立预后因素(P=0.100),这与Hong等[10]对242例pRCC患者的分析结果一致。同时,多因素分析还提示,在根治性肾切除术患者中,pRCC类型对预后无显著影响。因此,对于T1a期的2型pRCC患者,肾部分切除术仍是更好的选择。

对严重程度较高的pRCC患者(pT分期高、行根治性肾切除术)的分层分析提示,对行根治性肾切除术的pRCC患者,单因素分析显示pT分期、脉管癌栓和淋巴结转移是预后的影响因素,而多因素分析显示只有脉管癌栓是影响其预后的独立危险因素;对pT分期较高的pRCC患者(T3/T4期)的单因素和多因素回归分析没有发现影响预后的独立危险因素。

此外,Begg等[20]发现,在患者数量更多的医院和由经验丰富的外科医生进行手术会使术后并发症明显减少,但本研究纳入的病例均为同一医院的具有丰富经验的外科医生所执行的手术,基本可以忽略术者对预后的影响。本文仍存在一定的局限性,比如回顾性研究造成的偏倚和随访时间相对较短等,还有待于增加样本量并延长随访时间以进一步验证结论。

综上,本研究对pRCC患者的临床病理资料进行回顾性分析发现,1型和2型pRCC患者在年龄、BMI、手术方式、肿瘤最大径、有无脉管癌栓、有无淋巴结转移、pT分期和核分级方面存在明显差异,脉管癌栓是2型pRCC患者和高pT分期患者的独立预后因素。

Funding Statement

国家自然科学基金(82072828)、北京大学第三医院临床重点项目(BYSYZD2019016)和北京大学第三医院海淀创新转化专项科创研发(HDCXZHKC2021208)

Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82072828), Key Clinical Projects of Peking University Third Hospital (BYSYZD2019016), and Innovative Transformation Projects of Haidian District(HDCXZHKC2021208)

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qu Y, Chen H, Gu W, et al. Age-dependent association between sex and renal cell carcinoma mortality: A population-based analysis. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):9160. doi: 10.1038/srep09160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Znaor A, Lortet-Tieulent J, Laversanne M, et al. International variations and trends in renal cell carcinoma incidence and mortality. Eur Urol. 2015;67(3):519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akhtar M, Al-Bozom IA, Al Hussain T. Papillary renal cell carcinoma (PRCC): An update. Adv Anat Pathol. 2019;26(2):124–132. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mir MC, Derweesh I, Porpiglia F, et al. Partial nephrectomy versus radical nephrectomy for clinical T1b and T2 renal tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Eur Urol. 2017;71(4):606–617. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mancilla-Jimenez R, Stanley RJ, Blath RA, et al. Papillary renal cell carcinoma a clinical, radiologic, and pathologic study of 34 cases. Cancer. 1976;38(6):2469–2480. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197612)38:6<2469::AID-CNCR2820380636>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thoenes W, Störkel S, Rumpelt HJ. Histopathology and classification of renal cell tumors (adenomas, oncocytomas and carcinomas): The basic cytological and histopathological elements and their use for diagnostics. Pathol Res Pract. 1986;181(2):125–143. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(86)80001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delahunt B, Eble JN. Papillary renal cell carcinoma: A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 105 tumors. Mod Pathol. 1997;10(6):537–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aron M, Nguyen MM, Stein RJ, et al. Impact of gender in renal cell carcinoma: An analysis of the SEER database. Eur Urol. 2008;54(1):133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hong B, Hou H, Chen L, et al. The clinicopathological features and prognosis in patients with papillary renal cell carcinoma: A multicenter retrospective study in Chinese population. Front Oncol. 2021;11:753690. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.753690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bigot P, Bernhard JC, Gill IS, et al. The subclassification of papillary renal cell carcinoma does not affect oncological outcomes after nephron sparing surgery. World J Urol. 2016;34(3):347–352. doi: 10.1007/s00345-015-1634-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.洪 保安, 侯 惠民, 陈 凌霄, et al. 乳头状肾细胞癌的临床病理特征及预后分析. 中华泌尿外科杂志. 2020;41(12):896–900. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112330-20200502-00350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.董 樑, 黄 吉炜, 奚 倩雯, et al. 乳头状肾细胞癌的临床病理特征和预后分析. 中华泌尿外科杂志. 2015;36(3):183–187. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ha YS, Chung JW, Choi SH, et al. Clinical significance of subclassification of papillary renal cell carcinoma: Comparison of cli-nicopathologic parameters and oncologic outcomes between papillary histologic subtypes 1 and 2 using the Korean renal cell carcinoma database. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017;15(2):e181–e186. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2016.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan H, Ye L, Zhu Q, et al. The effect of the papillary renal cell carcinoma subtype on oncological outcomes. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):21073. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78174-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sukov WR, Lohse CM, Leibovich BC, et al. Clinical and pathological features associated with prognosis in patients with papillary renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2012;187(1):54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ku JH, Moon KC, Kwak C, et al. Is there a role of the histologic subtypes of papillary renal cell carcinoma as a prognostic factor? Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2009;39(10):664–670. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyp075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.黄 健. 中国泌尿外科和男科疾病诊断治疗指南(2019版) 北京: 科学出版社; 2020. pp. 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandes DS, Lopes JM. Pathology, therapy and prognosis of papillary renal carcinoma. Future Oncol. 2015;11(1):121–132. doi: 10.2217/fon.14.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Begg CB, Cramer LD, Hoskins WJ. Impact of hospital volume on operative mortality for major cancer surgery. JAMA. 1998;280(20):1747–1751. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.20.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]