Abstract

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is responsible for most morbidity and mortality in neonates. Early recognition of the clinical deterioration in newborns with NEC is essential to enhance the referral and management and potentially improve the outcomes. Here, we aimed to identify the prognostic factors and associate them with the clinical deterioration of preterm neonates with NEC. We analyzed the medical records of neonates with NEC admitted to our hospital from 2016 to 2021. We ascertained 214 neonates with NEC. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and cut-off level of age at onset, C-reactive protein (CRP), leukocyte count, and platelet count for the clinical deterioration of preterm neonates with NEC was 0.644 and 10.5 days old, 0.694 and 4.5 mg/L, 0.513 and 12,200/mm3, and 0.418 and 79,500/mm3, respectively. Late-onset, history of blood transfusion, thrombocytopenia, and elevated CRP were significantly associated with the clinical deterioration of neonates with NEC (p = < 0.001, 0.017, 0.001, and < 0.001, respectively), while leukocytosis, gestational age, and birth weight were not (p = 0.073, 0.274, and 0.637, respectively). Multivariate analysis revealed that late-onset and elevated CRP were strongly associated with the clinical deterioration of neonates with NEC, with an odds ratio of 3.25 (95% CI = 1.49–7.09; p = 0.003) and 3.53 (95% CI = 1.57–7.95; p = 0.002), respectively. We reveal that late-onset and elevated CRP are the independent prognostic factor for the clinical deterioration of preterm neonates with NEC. Our findings suggest that we should closely monitor preterm neonates with NEC, particularly those with late-onset of the disease and those with an elevated CRP, to prevent further clinical deterioration and intervene earlier if necessary.

Subject terms: Medical research, Risk factors

Introduction

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is a severe gastrointestinal emergency that affects preterm neonates1,2. NEC is responsible for most perioperative fatalities in pediatric surgery, with a mortality rate of up to 19%3. However, studies from developing countries on the clinical deterioration in preterm neonates are minimal.

In addition, validated early indicators of clinical deterioration in preterm neonates with NEC are essential. Early predictors for surgery in premature neonates with NEC would help enhance referral and treatment pathways and potentially improve outcomes4. Here, we aimed to identify the prognostic factors and associate them with the clinical deterioration of preterm neonates with NEC.

Methods

Patients

A retrospective study was conducted using medical records of neonates with NEC at our institution from January 2016 to June 2021. We included 237 diagnosed premature neonates with NEC, with the International Classification of Diagnosis (ICD) X code of P.77. Subsequently, we excluded 10 and 13 neonates due to term neonates and incomplete medical records, respectively. We investigated 214 neonates for final analysis5.

Staging of NEC

According to modified Bell's staging, the diagnosis and staging of NEC were established, consisting of the severity of systemic, intestinal, radiographic, and laboratory findings6.

Prognostic factors and ROC curve

We evaluated the following prognostic factors for the clinical deterioration of preterm neonates with NEC: age at onset, C-reactive protein (CRP), leukocyte count, platelet count, history of packed red cell (PRC) transfusion, gestational age, and birth weight. The CRP level was determined using an immunochemical assay (NycoCard™ CRP, Abbott, US) with the normal value of < 5 mg/L. We defined clinical outcomes of NEC into two categories: worsened and improved. The clinical deterioration was defined as worsening of the modified Bell's staging. According to gestational age, the preterm birth was classified into the following: extremely preterm (< 28 weeks), very preterm (28 to < 32 weeks), and moderate to late preterm (32 to < 37 weeks)7. The birth weight was defined as normal birth weight (NBW) (≥ 2500 g), low birth weight (LBW) (< 2500 g), very low birth weight (VLBW) (< 1500 g), and extremely low birth weight (ELBW) (< 1000 g)8.

The cut-off value of age at onset, CRP, leukocyte count, and platelet count was analyzed by receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves. According to a previous study, we assumed the cut-off level for late-onset NEC in preterm infants was ≥ 14 days9.

Statistical analysis

The Chi-square test was used to determine the association between the prognostic factors and the clinical deterioration of premature neonates with NEC. The multivariate regression test was used to look for the strong prognostic factors for clinical deterioration of premature neonates with NEC. The p-value of < 0.05 was determined as a significant level. The IBM SPSS Statistics version 16 (SPSS Chicago, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada/Dr. Sardjito Hospital, Yogyakarta, Indonesia (KE/FK/0464/EC/2021). Written informed consent was obtained from all parents for participating in this study. The research has been performed following the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 214 preterm neonates with NEC were included in the study, with 77% improved clinical outcomes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of neonates with NEC in our institution.

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 98 (45.8) |

| Female | 116 (54.2) |

| History of PRC transfusion | |

| Yes | 112 (52.3) |

| No | 102 (47.7) |

| Clinical outcomes | |

| Worsened | 49 (23) |

| Improved | 165 (77) |

NEC necrotizing enterocolitis, PRC packed red cell.

s.

Association between prognostic factors and clinical deterioration of preterm neonates with NEC

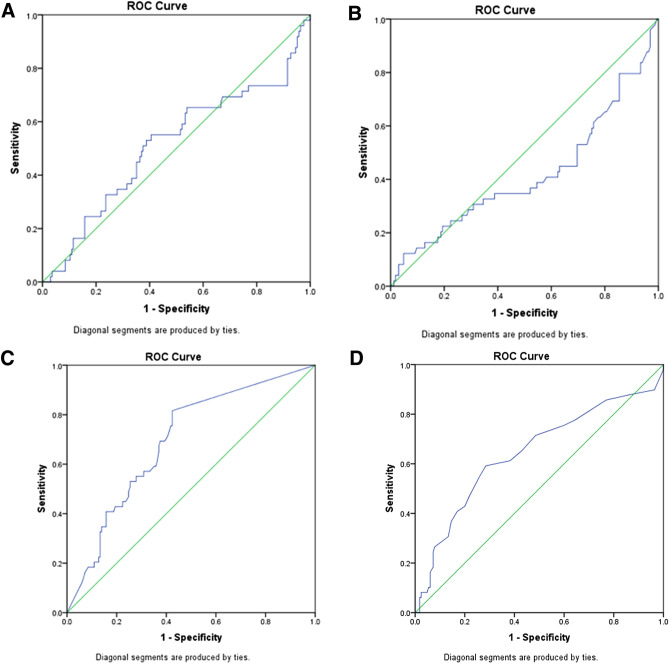

The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and cut-off level of age at onset, C-reactive protein (CRP), leukocyte count, and platelet count for the clinical deterioration of preterm neonates with NEC was 0.644 and 10.5 days old, 0.694 and 4.5 mg/L, 0.513 and 12,200/mm3, and 0.418 and 79,500/mm3, respectively (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

ROC curve of leucocyte count (A), platelet count (B), C-reactive protein (C), and the onset of NEC (D) for distinguishing between worsened and improved clinical deterioration of NEC, with the area under the ROC curve of 0.513, 0.418, 0.694, and 0.644, respectively.

Late-onset, history of blood transfusion, thrombocytopenia, and elevated CRP were significantly associated with the clinical deterioration of neonates with NEC (p = < 0.001, 0.017, 0.001, and < 0.001, respectively), while leukocytosis, gestational age, and birth weight were not (p = 0.073, 0.274, and 0.637, respectively). (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between prognostic factors and clinical deterioration with NEC in our institution.

| Variables | Clinical outcomes | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worsened (N, %) | Improved (N, %) | |||

| Age at onset (days) | < 0.001* | |||

| ≥ 10.5 | 29 (38.2) | 47 (61.8) | 2.63 (1.6–4.32) | |

| < 10.5 | 20 (14.5) | 118 (85.5) | ||

| History of PRC transfusion | 0.017* | |||

| Yes | 33 (29.5) | 79 (70.5) | 2.25 (1.15–4.39) | |

| No | 16 (15.8) | 86 (84.2) | ||

| Leukocyte count (/mm3) | 0.073 | |||

| ≥ 12,200 | 27 (28.7) | 67 (71.3) | 1.57 (0.96–2.57) | |

| < 12,200 | 22 (18.3) | 98 (81.7) | ||

| Platelet count (/mm3) | 0.001* | |||

| ≤ 79,500 | 27 (35.1) | 50 (64.9) | 2.18 (1.34–3.56) | |

| > 79,500 | 22 (16.1) | 115 (83.9) | ||

| CRP (mg/L) | < 0.001* | |||

| ≥ 4.5 | 40 (36.4) | 70 (63.6) | 4.2 (2.15–8.23) | |

| < 4.5 | 9 (8.7) | 95 (91.3) | ||

| Gestational age | 0.274 | |||

| Extremely preterm | 1 (7.1) | 13 (92.9) | 0.22 (0.03–1.78) | |

| Very preterm | 16 (21.3) | 59 (78.3) | 0.79 (0.39–1.56) | |

| Moderate to late preterm | 32 (25.6) | 93 (74.4) | ||

| Birth weight | 0.637 | |||

| ELBW | 12 (30) | 28 (70) | 2.14 (0.41–11.29) | |

| VLBW | 15 (20.3) | 59 (79.7) | 1.27 (0.25–6.43) | |

| LBW | 20 (22.7) | 68 (77.3) | 1.47 (0.29–7.27_ | |

| NBW | 2 (16.7) | 10 (83.3) | ||

*, p < 0.05; CI, confidence interval, OR odds ratio, NEC necrotizing enterocolitis, PRC packed red cell, CRP C-reactive protein, NBW normal birth weight, LBW low birth weight, VLBW very low birth weight, ELBW extremely low birth weight.

Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors for clinical deterioration of preterm neonates with NEC

Multivariate analysis revealed that late-onset and elevated CRP were strongly associated with the clinical deterioration of neonates with NEC, with an odds ratio of 3.25 (95% CI = 1.49–7.09; p = 0.003) and 3.53 (95% CI = 1.57–7.95; p = 0.002), respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of the clinical deterioration of premature neonates with NEC in our institution.

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Late-onset | 3.25 (1.49–7.09) | 0.003* |

| History of PRC transfusion | 2.04 (0.95–4.39) | 0.07 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1.27 (0.59–2.75) | 0.539 |

| Elevated CRP | 3.53 (1.57–7.95) | 0.002* |

*, p < 0.05; CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio, NEC necrotizing enterocolitis, PRC packed red cell, CRP C-reactive protein.

Discussion

Since the survival of preterm newborns is continuously enhanced, it is advised that clinicians search for the modifiable prognostic factors for NEC to intervene earlier and prevent further clinical deterioration10,11. The frequency of clinical deterioration of our patients was 23%. It is similar to a previous study12. In addition, our study shows that late-onset and elevated CRP were the strong prognostic factors for the clinical deterioration of NEC with the OR of ~ 4 and fivefold, respectively. It is similar to a previous study13. CRP is an acute-phase reactant that rises in the bloodstream in response to infection or tissue damage. The liver generates it in response to infection or tissue damage that causes inflammation. CRP was shown to be higher in 83% of neonates with confirmed NEC at the time of diagnosis compared to those without NEC in a previous study14. Pourcyrous et al.15 recently used serial CRP measures to identify preterm infants with NEC in a large cohort. CRP levels were abnormal in both stages II and III of NEC15. They concluded that persistently high CRP levels in neonates with NEC might indicate persisting illness and/or complications and suggested serial CRP tests for NEC follow-up15. Notably, we do not have any data on blood culture. Therefore, our findings should be interpreted cautiously; mainly, the CRP might reflect the intestinal necrosis that occurs in NEC rather than infection.

In this study, the cut-off level of age at onset was 10.5 days. Our findings were compatible with another study16. We showed that premature neonates with late-onset NEC are fivefold more likely to deteriorate clinically than those with early-onset NEC. Our findings are compatible with a previous study17. However, previous studies revealed that the early onset of NEC is an independent prognostic factor for NEC to be managed surgically16,18,19. The timing of NEC development in term and preterm infants has been studied extensively in a prior study20. Early-onset NEC individuals were more likely to require surgery20. A previous study suggested that a more widespread immaturity of the intestinal innate immune response might contribute to the observed increased inflammation in the juvenile gut and hence play a role in the onset of NEC21.

There was a strong inverse association between gestational age and birth weight with NEC mortality22,23. However, our study did not show any association between gestational age and birth weight with the clinical deterioration of NEC. These differences might be due to several factors, including broad discrepancies in patient populations, disease degree, coexisting illnesses, and severity classification among institutions24. Moreover, the following important variables might explain the NEC occurring in neonates with LBW, such as the immaturity of the gastrointestinal tract and its function, barrier function, regulation of circulation, and immune defense25.

Thrombocytopenia is frequently found in NEC neonates and is a poor prognostic variable when platelet counts drop quickly26. Lower platelet counts were linked to the development of surgical NEC26. On the other hand, low platelet count was not found to be a reliable predictor of surgical NEC17. Intestinal ischemia can result in platelet thrombi and platelet consumption at the local level27. Furthermore, these platelet thrombi may hasten the bowel's necrosis process. Our study did not support thrombocytopenia as a significant prognostic factor for clinical deterioration of NEC.

PRC transfusion has been linked to the development of NEC in premature infants28–30. However, our study did not reveal a significant association between the history of PRC transfusion and clinical deterioration of preterm neonates with NEC. Christensen et al.29 found that neonates who had surgery for NEC after PRC transfusion had a greater mortality rate than infants who had surgery for NEC without PRC transfusion. However, these differences were not statistically significant. In addition, PRC transfusion is linked to an increased risk of surgical intervention31. This might be caused by the donated PRCs that are exposed to significant stress during the collection, preservation, and storage32. Red blood cells go through structural and metabolic changes that might impair intestinal oxygen transport33,34. The production of cytokines and other pro-inflammatory substrates after infusion of these products might cause an inflammatory response33.

In our cohort, leukocytosis did not correlate with the deterioration of premature NEC neonates. In most cases, leukocytosis is thought to be a response to inflammatory processes. Various etiologies, including infection, inflammation, medications, and stress, may lead to a change of leucocyte counts in newborns35.

Our study has limitations, such as a retrospective design and a single-center report, indicating that more multicenter research is needed to validate our findings. These facts should be considered during the interpretation of our results.

Conclusions

We reveal that late-onset and elevated CRP are the independent prognostic factor for the clinical deterioration of preterm neonates with NEC. Our findings suggest that we should closely monitor preterm neonates with NEC, particularly those with late-onset of the disease and those with an elevated CRP, to prevent further clinical deterioration and intervene earlier if necessary.

Acknowledgements

We extend our thanks to physicians and nurses who provided excellent management for the patients. Some results for the manuscript are from Ibnu Sina Ibrohim’s thesis.

Abbreviations

- PRC

Packed red cell

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CI

Confidence interval

- OR

Odds ratio

- NEC

Necrotizing enterocolitis

Author contributions

I.S.I., N.A., and G. conceived the study. I.S.I., A.R.F., K.I., and G. drafted the manuscript. I.S.I. and G. analyzed the data. H.A.P., I.S.I., N.A., and G. facilitated all project-related tasks. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the submission. The raw data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lang J, Hickey L, King S, Curley A. OC58 Morbidity and mortality of medical and surgical necrotizing enterocolitis. Arch. Dis. Child. 2019;104:A24. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones IH, Hall NJ. Contemporary outcomes for infants with necrotizing enterocolitis—a systematic review. J. Pediatr. 2020;220:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonasso PC, Dassinger MS, Ryan ML, Gowen MS, Burford JM, Smith SD. 24-hour and 30-day perioperative mortality in pediatric surgery. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2019;54:628–630. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gregory KE. Clinical predictors of necrotizing enterocolitis in premature infants. Nurs. Res. 2008;57:260–270. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000313488.72035.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ibrohim, I.S., Agustriani, N., Gunadi. Faktor prognosis terjadinya perburukan enterokolitis nekrotikan pada pasien bayi prematur [Thesis] [Bahasa]. Yogyakarta (Indonesia): Universitas Gadjah Mada; (2021).

- 6.Kim, J.H. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis: Clinical features and diagnosis. In: UpToDate, Abrams SA, Kim MS (Eds), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (Accessed on September 18, 2021).

- 7.World Health Organization. Preterm birth [Internet]. World Health Organization [updated February 19, 2018; Accessed on June 9, 2022]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth.

- 8.Mandy GT. Preterm birth: Definitions of prematurity, epidemiology, and risk factors for infant mortality. In: UpToDate, Weisman LE, Wilkie L (Eds), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (Accessed on June 9, 2022).

- 9.Berrington JE, Embleton ND. Time of onset of necrotizing enterocolitis and focal perforation in preterm infants: impact on clinical, surgical, and histological features. Front. Pediatr. 2021;9:724280. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.724280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alsaied A, Islam N, Thalib L. Global incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20:344. doi: 10.1186/s12887-020-02231-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siahaan ESED, Adriansyah W, Sasmita AP, Fauzi AR, Dwihantoro A, Gunadi G. Outcomes and prognostic factors for survival of neonates with necrotizing enterocolitis. Front. Pediatr. 2021;9:744504. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.744504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang ZL, Liu L, Hu XY, Guo L, Li QY, An Y, Jiang YJ, Chen S, Wang XQ, He Y, Li LQ. Probiotics may not prevent the deterioration of necrotizing enterocolitis from stage I to II/III. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12887-018-1376-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo L, Dong W, Zhang L, Zhai X, Li Q, Lei X. Correlative factors of the deterioration of necrotizing enterocolitis in small for gestational age newborns. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1–6. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18467-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Çetinkaya M, Özkan H, Köksal N, Akacı O, Özgür T. Comparison of the efficacy of serum amyloid A, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin in the diagnosis and follow-up of necrotizing enterocolitis in premature infants. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2011;46:1482–1489. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pourcyrous M, Korones SB, Yang W, Boulden TF, Bada HS. C-reactive protein in the diagnosis, management, and prognosis of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1064–1069. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berman L, Moss RL. Necrotizing enterocolitis: an update. Semin. Fetal Neonatal. Med. 2011;16:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Short SS, Papillon S, Berel D, Ford HR, Frykman PK, Kawaguchi A. Late onset of necrotizing enterocolitis in the full-term infant is associated with increased mortality: Results from a two-center analysis. J. Ped. Surg. 2014;49:950–953. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Hassani SE, Niemarkt HJ, Derikx JP, Berkhout DJ, Ballón AE, de Graaf M, de Boode WP, Cossey V, Hulzebos CV, van Kaam AH, Kramer BW. Predictive factors for surgical treatment in preterm neonates with necrotizing enterocolitis: A multicenter case-control study. Eur. J. Ped. 2021;180:617–625. doi: 10.1007/s00431-020-03892-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duci M, Fascetti-Leon F, Erculiani M, Priante E, Cavicchiolo ME, Verlato G, Gamba P. Neonatal independent predictors of severe NEC. Ped. Surg. Int. 2018;34:663–669. doi: 10.1007/s00383-018-4261-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yee WH, Soraisham AS, Shah VS, Aziz K, Yoon W, Lee SK. Canadian neonatal network. Incidence and timing of presentation of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):e298–304. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nanthakumar N, Meng D, Goldstein AM, Zhu W, Lu L, Uauy R, Llanos A, Claud EC, Walker WA. The mechanism of excessive intestinal inflammation in necrotizing enterocolitis: An immature innate immune response. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17776. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fitzgibbons SC, Ching Y, Yu D, Carpenter J, Kenny M, Weldon C, Lillehei C, Valim C, Horbar JD, Jaksic T. Mortality of necrotizing enterocolitis expressed by birth weight categories. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2009;44(6):1072–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.González-Rivera R, Culverhouse RC, Hamvas A, Tarr PI, Warner BB. The age of necrotizing enterocolitis onset: an application of Sartwell's incubation period model. J. Perinatol. 2011;31(8):519–523. doi: 10.1038/jp.2010.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Springer, S.C., Annibale, D. J. Necrotizing enterocolitis [Internet]. Emedicine.medscape.com [updated December 27, 2017; Accessed on June 9, 2022]. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/977956-overview#a1.

- 25.Lin HY, Chang JH, Chung MY, Lin HC. Prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm very low birth weight infants: is it feasible? J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2014;113(8):490–497. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dominguez KM, Moss RL. Necrotizing enterocolitis. Clin. Perinatol. 2012;39:387–401. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hutter JJ, Jr, Hathaway WE, Wayne ER. Hematologic abnormalities in severe neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. J. Pediatr. 1976;88:1026–1031. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(76)81069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blau J, Calo JM, Dozor D, Sutton M, Alpan G, La Gamma EF. Transfusion-related acute gut injury: necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight neonates after packed red blood cell transfusion. J. Pediatr. 2011;158:403–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christensen RD, Lambert DK, Henry E, Wiedmeier SE, Snow GL, Baer VL, Gerday E, Ilstrup S, Pysher TJ. Is “transfusion-associated necrotizing enterocolitis” an authentic pathogenic entity? Transfusion. 2010;50:1106–1112. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Josephson CD, Wesolowski A, Bao G, Sola-Visner MC, Dudell G, Castillejo MI, Shaz BH, Easley KA, Hillyer CD, Maheshwari A. Do red cell transfusions increase the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis in premature infants? J. Pediatr. 2010;157:972–978. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.05.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cunningham KE, Okolo FC, Baker R, Mollen KP, Good M. Red blood cell transfusion in premature infants leads to worse necrotizing enterocolitis outcomes. J. Surg. Res. 2017;213:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2017.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.La Gamma EF, Feldman A, Mintzer J, Lakshminrusimha S, Alpan G. Red blood cell storage in transfusion-related acute gut injury. Neo Rev. 2015;16:e420–e430. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharma R, Hudak ML. A clinical perspective of necrotizing enterocolitis: Past, present, and future. Clin. Perinatol. 2013;40:27–51. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mally P, Golombek SG, Mishra R, Nigam S, Mohandas K, Depalhma H, LaGamma EF. Association of necrotizing enterocolitis with elective packed red blood cell transfusions in stable, growing, premature neonates. Am. J. Perinatol. 2006;23:451–458. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-951300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morag I, Dunn M, Nayot D, Shah PS. Leukocytosis in very low birth weight neonates: Associated clinical factors and neonatal outcomes. J. Perinatol. 2008;28:680–684. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the submission. The raw data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.