Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of premature death and disability worldwide, with both genetic and environmental determinants. While genome-wide association studies have identified multiple genetic loci associated with cardiovascular diseases, exact genes driving these associations remain mostly uncovered. Due to Finland’s population history, many deleterious and high-impact variants are enriched in the Finnish population giving a possibility to find genetic associations for protein-truncating variants that likely tie the association to a gene and that would not be detected elsewhere. In a large Finnish biobank study FinnGen, we identified an association between an inframe insertion rs534125149 in MFGE8 (encoding lactadherin) and protection against coronary atherosclerosis. This variant is highly enriched in Finland, and the protective association was replicated in meta-analysis of BioBank Japan and Estonian biobank. Additionally, we identified a protective association between splice acceptor variant rs201988637 in MFGE8 and coronary atherosclerosis, independent of the rs534125149, with no significant risk-increasing associations. This variant was also associated with lower pulse pressure, pointing towards a function of MFGE8 in arterial aging also in humans in addition to previous evidence in mice. In conclusion, our results suggest that inhibiting the production of lactadherin could lower the risk for coronary heart disease substantially.

Subject terms: Cardiovascular genetics, Genome-wide association studies

A genome-wide association study identifies MFGE8 as protective against coronary atherosclerosis in European and East Asian populations.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of premature death and disability worldwide, with both genetic and environmental determinants1,2. The most common cardiovascular disease is coronary heart disease (CHD), including coronary atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction, among others. While genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified multiple genetic loci associated with cardiovascular diseases, exact genes driving these associations remain mostly uncovered3.

Owing to Finland’s population history, many deleterious and high-impact variants are enriched in the Finnish population giving a possibility to find genetic associations that would not be detected elsewhere4. Many studies have reported high-impact loss-of-function (LoF) variants associated with risk factors for CVD, such as blood lipid levels, thus impacting on the CVD risk remarkably. For example, high-impact LoF variants in genes LPA4, PCSK95, APOC36, and ANGPTL47 have been shown to be associated with Lipoprotein(a), LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C), or triglyceride levels, and lowering the CVD risk.

Besides blood lipids, other risk factors for CVD include hypertension, smoking and the metabolic syndrome cluster components. The mechanism that links these risk factors to atherogenesis, however, remains incompletely elucidated. Many, if not all, of these risk factors, however, also participate in the activation of inflammatory pathways, and inflammation in turn can alter the function of artery wall cells in a manner that drives atherosclerosis8.

Using data from a sizeable Finnish biobank study FinnGen (n = 260,405), we identified an association with an inframe insertion rs534125149 in MFGE8 and protection against coronary atherosclerosis and other representations of major coronary heart disease (CHD), such as myocardial infarction (MI). This variant is highly enriched in Finland, 70-fold compared to Non-Finnish Europeans (NFE) in the gnomAD genome reference database9 with AF of 3% in Finland. This association was also replicated in BioBank Japan (BBJ) and Estonian Biobank (EstBB). We also identified a splice acceptor variant rs201988637 in the same gene, which is also associated with protection against coronary atherosclerosis and other representations of major CHD, indicating that rs534125149 has very similar effect on CHD as a splice acceptor variant in MFGE8. Associations of both of these two variants in MFGE8 were specific to CHD, and they did not significantly (p < 1.75 × 10−5) increase risk for any other disease, highlighting MFGE8 as a potential drug target candidate.

Results

GWAS results for coronary atherosclerosis

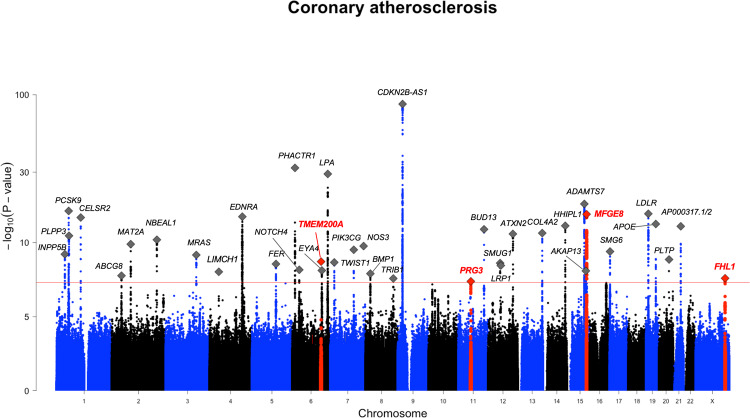

We identified a total of 2 302 variants associated (GWS, p < 5 × 10−8) with coronary atherosclerosis (detailed description of the definition of the endpoint is in Supplementary Note 1). These variants were located in 38 distinct genetic loci (a minimum of 0.5 Mb distance from each other; Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Out of the 38 GWS loci, four (within or near genes MFGE8, TMEM200A, PRG3, and FHL1) have not been previously reported to associate with any CVD-related endpoints or risk factor for CVD in GWAS Catalog10 [https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/]. Lead variants in these loci and their characteristics are listed in Table 1 and locus zoom plots for each of the loci are in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. GWAS results for coronary atherosclerosis in FinnGen.

Total number of independent genome-wide significant associations (GWS; p < 5 × 10-8) is 38, the lead variant in each marked with diamonds. Four previously unreported associations for CVD-related phenotypes are highlighted with ±750 Mb around the lead variant in the region as red and the lead variant marked with red diamond.

Table 1.

Lead variants in previously unreported loci for coronary atherosclerosis.

| Lead variant chrom:pos:ref_alt (rsid) | Most severe consequence | Nearest gene | FIN enrichment (NFE) | AF | OR (p-value) |

Info | # cs (Post-pr) | #coding in cs(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chr15:88901702:C_CTGT (rs534125149) | Inframe insertion | MFGE8 | 70.59 | 0.029 | 0.75 (2.60 × 10−16) | 0.99 | 2 (0.705) | 1 |

| chr6:130483492:A_G (rs118042209) | Intergenic variant | TMEM200A | 0.87 | 0.010 | 0.7 (1.90 × 10−9) | 0.91 | 1 (0.904) | 0 |

| chr11:57380633:A:G (rs764568652) | Intron variant | PRG3 | a | 0.0003 | 7.72 (4.12 × 10−8) | 0.89 | 1 (0.583) | 0 |

| chrX:136194941:C_G (rs5974585) | Intron variant | FHL1 | 1.25 | 0.49 | 0.95 (2.55 × 10−8) | 0.99 | 1 (0.692) | 0 |

aVariant not present in NFE in gnomAD.

Among these four previously unreported loci for coronary atherosclerosis, the locus near MFGE8 had the strongest association (p-value = 2.63 × 10−16 for top variant rs534125149). The lead variant is an inframe insertion located in the sixth exon in the MFGE8 gene (Supplementary Fig. 2) and it is highly enriched in the Finnish population compared to NFSEEs (Non-Finnish, Estonian or Swedish Europeans). Interestingly, MFGE8 is mainly expressed in coronary and tibial arteries according to data from GTEx v8 (Supplementary Fig. 3), and furthermore the expression of MFGE8 is highest in aorta. In addition, previously identified common variants in MFGE8 locus that have been associated with decreased expression of MFGE8 in tibial artery and aorta have also been associated with decreased risk of CHD11.

In addition to MFGE8, we identified three additional previously unreported loci to be associated with coronary atherosclerosis, TMEM200A, PRG3 and FHL1 being the nearest genes of the lead variants. TMEM200A and PRG3 loci had one non-coding low-frequency variant reaching the genome-wide significance threshold, and FHL1 had 11. All variants in the credible sets of all these associations were either intergenic or intronic variants and had no reported significant GWAS associations with any trait in the GWAS Catalog or significant eQTL associations in GTEx. The one variant (rs118042209) in the credible set of TMEM200A locus was associated with multiple disease endpoints representing major coronary heart disease (CHD) in FinnGen, including coronary atherosclerosis, ischemic heart disease and angina pectoris, whereas the lead variant in the PRG3 locus was associated with cardiomyopathy. All variants in the credible set of FHL1 were associated with multiple disease endpoints representing major CHD in FinnGen, including angina pectoris and ischemic heart disease. TMEM200A have been reported to be associated with ten traits (including height and trauma exposure) and PRG3 with two traits (eosinophil count and eosinophil percentage of white cells) in the GWAS Catalog. FHL1 gene had no reported associations in GWAS Catalog.

Replication

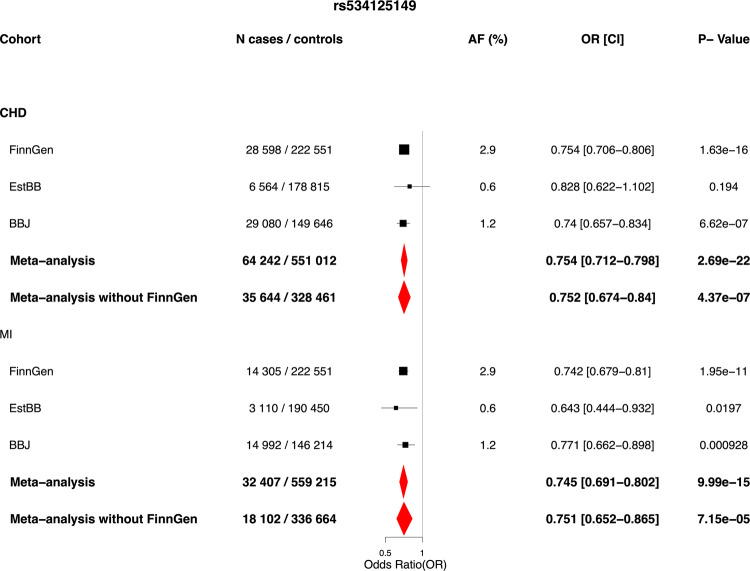

Association between rs534125149 in MFGE8 locus with CHD was replicated in Biobank Japan12,13 (BBJ) and the Estonian Biobank (EstBB)14 (35,644 cases and 328 461 controls total: OR = 0.752 [0.67–0.84], p = 4.37 × 10−7). Association results for rs534125149 with CHD and MI across different cohorts are in Fig. 2. Post hoc power calculations for each cohort were performed (probability that the test will reject the null hypothesis H0 at GWS threshold) and the results as the function of effect size are in Supplementary Fig. 4. From these calculations we can see that in FinnGen the power to detect the variant as GWS is remarkably greater than in EstBB or BBJ, even with similar effect sizes and sample sizes. Therefore, this boost in power in FinnGen seems to be mainly due to a different allele frequencies, since this variant is highly enriched to Finland.

Fig. 2. Results for rs534125149 against coronary heart disease and myocardial infarction across cohorts where available and meta-analysis results.

Logistic regression has been applied, adjusted for age and sex. Meta-analysis was performed using inverse-variance weighted fixed-effects meta-analysis method. Black dots represents odds ratios, and lines 95% confidence interval from the the single cohorts and red diamonds represent the results from meta-analysis ends of the diamonds representing the ends of the 95% confidence interval. Source data for the figure is in Supplementary Data 1.

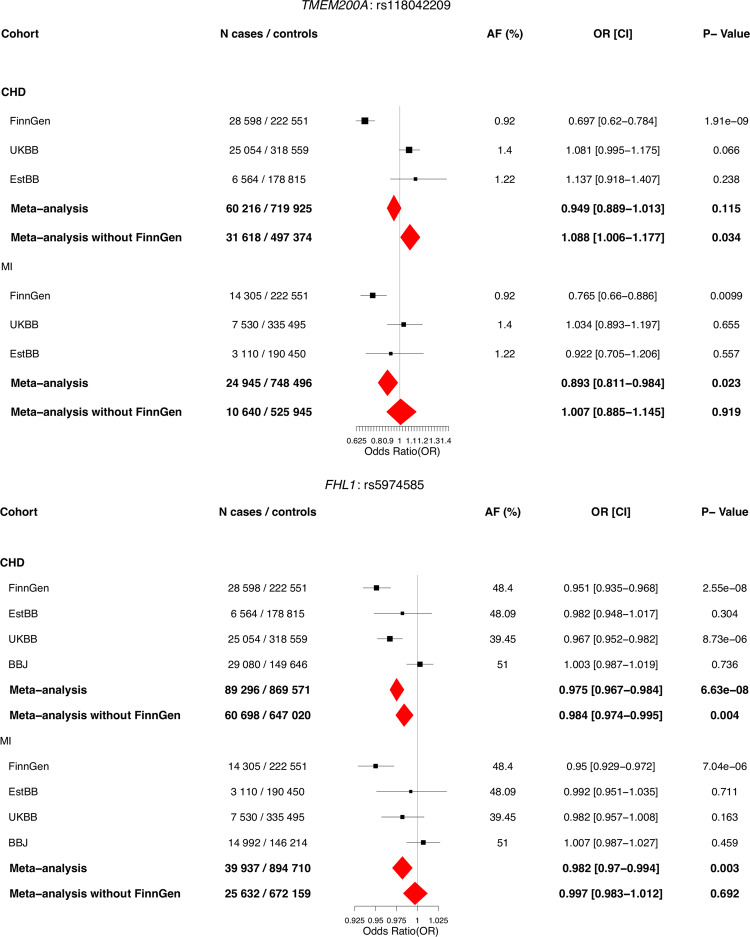

In addition to MFGE8, meta-analysis across FinnGen, UKBB, EstBB, and BBJ was performed for the lead variants in the three other previously unreported loci for CHD (TMEM200A, PRG3, and FHL1), where available. Lead variant in PRG3 locus is highly enriched to Finland and absent in all other cohorts, and thus replication efforts for that variant were not possible. The two other loci that were meta-analyzed (TMEM200A and FHL1) did not replicate (p-value in the combined meta-analysis of the replication cohorts (meta-analysis without FinnGen) is smaller than 0.05/4 = 0.0125 and all effect size estimates are in same direction). Association results for rs534125149 with CHD and MI across different cohorts for TMEM200A and FHL1 variants are in Fig. 3. Post hoc power calculations for each cohort were performed and the results as the function of effect size are in Supplementary Fig. 5. From those results we can see that the lack of replication in UKBB, EstBB and BBJ does not appear to be due to lack of power. Therefore, we identified and replicated one novel locus for CHD (MFGE8).

Fig. 3. Results for rs118042209 in TMEM200A and rs5974585 in FHL1 against coronary heart disease and myocardial infarction across different cohorts across cohorts where available.

Logistic regression has been applied, adjusted for age and sex. Meta-analysis was performed using inverse-variance weighted fixed-effects meta-analysis method. Black dots represent odds ratios, and lines 95% confidence interval from the single cohorts and red diamonds represent the results from meta-analysis ends of the diamonds representing the ends of the 95% confidence interval. Source data for the figure is in Supplementary Data 1.

Phenome-wide association results for rs534125149

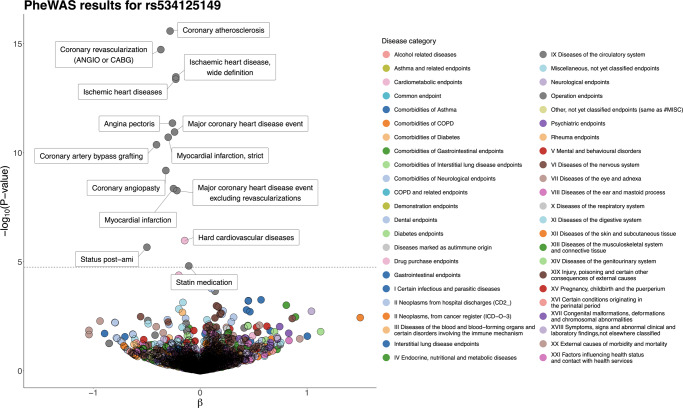

We observed a highly protective association for the Finnish enriched inframe insertion rs534125149 in the MFGE8 gene and multiple disease endpoints, all representing major CHD, including coronary atherosclerosis (OR = 0.75 [0.71–0.81], p = 2.63 × 10−16) and myocardial infarction (MI) (OR = 0.74 [0.68–0.81], p = 1.95 × 10−11). In total, this variant was associated (PWS) with 14 disease endpoints, all representing major CHD (Fig. 4). Majority of them are highly overlapping, and thus similar associations to all of them is expected. Thus, we pruned the 14 PWS disease endpoints down to six disease endpoints (coronary atherosclerosis, coronary revascularization, ischemic heart diseases, major coronary heart disease event, myocardial infarction, and statin medication) that have fundamental characteristics for further analyses. For the inframe insertion rs534125149 in MFGE8, we did not detect other phenome-wide significant associations among the 2 861 endpoints in our data.

Fig. 4. Phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) results for rs534125149.

Total number of tested endpoints is 2861 (A complete list of endpoints analyzed and their definitions is available at https://www.finngen.fi/en/researchers/clinical-endpoints). The dashed line represents the phenome-wide significance threshold, multiple testing corrected by the number of endpoints = 0.05/2861 = 1.75 × 10−5. All endpoints reaching that threshold are labeled in the figure.

Splice acceptor variant rs201988637 in MFGE8

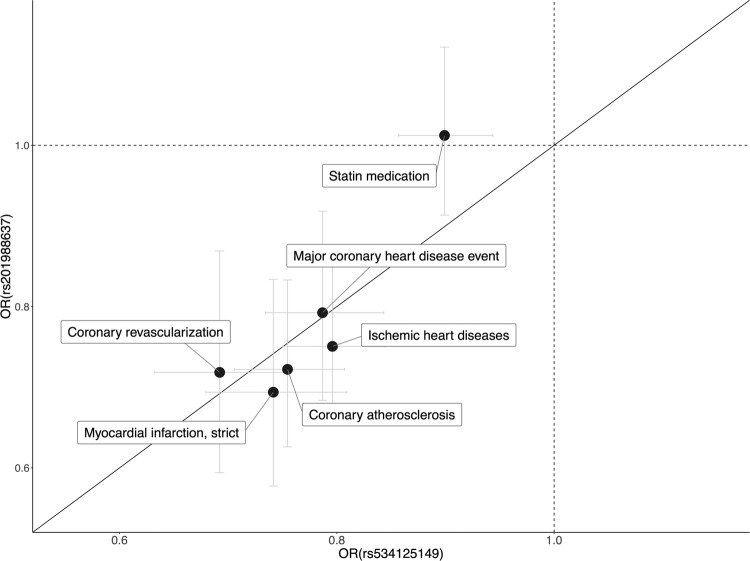

In addition to inframe insertion rs53412514, we identified a splice acceptor variant (rs201988637) in MFGE8 to be associated with coronary atherosclerosis (OR = 0.72 [0.63–0.83], p = 7.94 × 10−06) and multiple disease endpoints representing major CHD. The splice acceptor variant had very similar PheWAS profile as the inframe insertion (Supplementary Fig. 6) and furthermore the two variants had very similar protective effect sizes for the endpoints (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 2). Similar to rs534125149, this variant is also highly enriched in Finland (37-fold compared to NFE), allele frequency in Finland being 0.6%. Moreover, both the splice acceptor and the inframe insertion variants were enriched to Eastern Finland (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Fig. 5. Effect size comparison.

Comparison of the effects (OR) of rs534125149 and rs201988637 for 14 endpoints with p-value < 1.75 × 10-5 (PWS) for rs534125149 in FinnGen R6. 95% confidence intervals represented as gray lines.

These two variants (rs534125149 and rs201988637) are in low linkage disequilibrium (LD, r2 = 0.00015) and did not have any effect on the other variant’s associations with coronary atherosclerosis or MI (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 8). This indicates that they both are independently associated with these endpoints.

Table 2.

Results of the conditional analysis on MI and coronary atherosclerosis.

| Phenotype | SNPID [chr:position:ref:alt] (rsid) | Most severe consequence | Original GWAS results | Conditional results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR [CI] | p-value | OR [CI] | p-value | |||

| Coronary atherosclerosis | chr15:88901702:C:CTGT (rs534125149) | Inframe insertion | 0.75 [0.71–0.81] | 2.63 × 10−16 | 0.75 [0.70–0.80]a | 7.68 × 10−15a |

| chr15:88899813:T:G (rs201988637) | Splice acceptor variant | 0.72 [0.63–0.83] | 7.94 × 10−6 | 0.73 [0.64–0.85]b | 1.99 × 10−5b | |

| Myocardial infarction, strict | chr15:88901702:C:CTGT (rs534125149) | Inframe insertion | 0.74 [0.68–0.81] | 1.95 × 10−11 | 0.79 [0.73–0.85]a | 1.92 × 10−10a |

| chr15:88899813:T:G (rs201988637) | Splice acceptor variant | 0.69 [0.58–0.83] | 9.62 × 10−5 | 0.71 [0.59–0.85]b | 4.03 × 10−4b | |

This table present the conditional analysis results for coronary atherosclerosis and MI (strict definition, only primary diagnoses accepted) where the association has been conditioned on rs534125149 and rs201988637, separately.

aConditional on rs201988637.

bConditional on rs534125149.

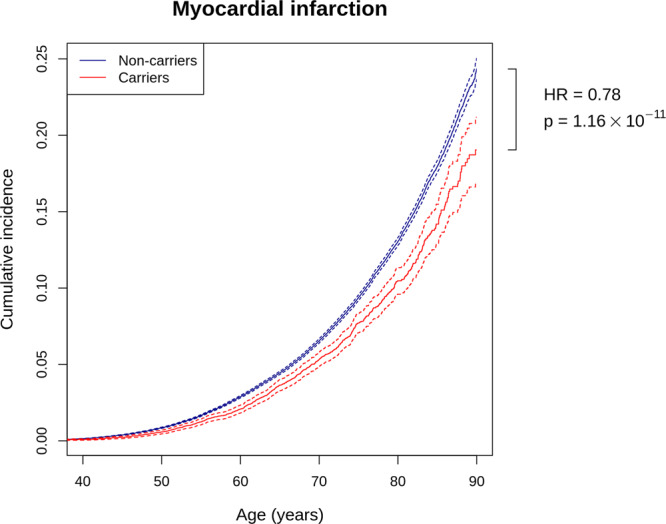

Survival analysis

In addition to protection against coronary atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction, both the infame insertion rs534125149 and splice acceptor variant rs201988637 showed also significant association in survival analysis when analyzing survival time from birth to first diagnose of coronary atherosclerosis (HR = 0.78 [0.74–0.93]), p = 1.67 × 10−17 and HR = 0.77 [0.69–0.88], p = 5.08 × 10−05, respectively) and myocardial infarction (HR = 0.86 [0.80–0.93], p = 2.63 × 10−10 and HR = 0.72 [0.61–0.85], p = 8.16 × 10−05). In addition, when combining the heterozygous and homozygous carriers of both rs534125149 and rs201988637 together, carriers get the first diagnose significantly later than non-carriers (HR = 0.81 [0.77–0.85], p = 6.4 × 10−16 for coronary atherosclerosis and HR = 0.78 [0.72–0.85], p = 1.16 × 10−11 for MI) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Cumulative incidence plots for first event of myocardial infarction in FinnGenR6.

Red line represents carriers (homo- or heterozygous) for either rs534125149 or rs201988637 (n = 17,838), and blue line represent non-carriers (n = 242,567). Hazard ratio and p-value are from cox-proportional hazards model. Dashed lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

In addition, as a sensitivity analysis we performed the similar Cox model for first event of MI by adding different risk factors for CHD as covariates in the model to see if any of these risk factors (BMI, Type 2 Diabetes, smoking, statin use or sex) have impact on the observed association. Risk factors were added to the model both individually and together. As a result, we saw only a small change in the effect size when adjusting for these risk factors (Supplementary Table 3). The change was more noticeable on p-values where the missing data in the added covariates lead to decreased statistical power.

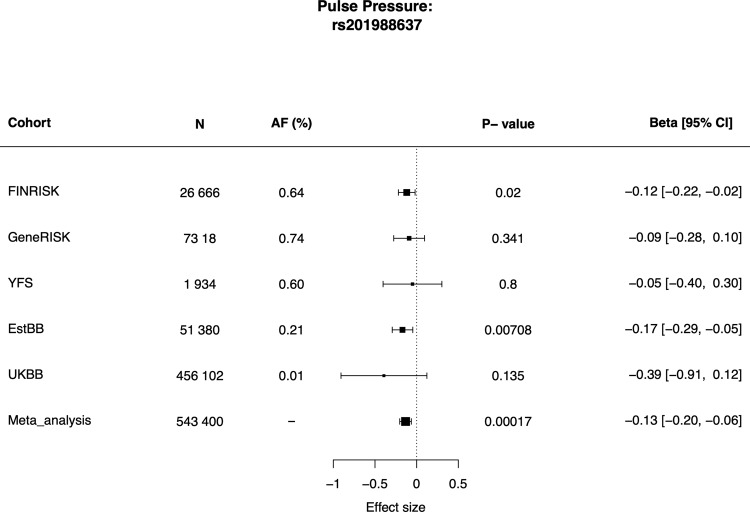

Associations with risk factors for CVD

We then tested for possible associations between the MFGE8 variants and risk factors for CVD. The splice acceptor variant rs201988637 was associated with pulse pressure in analyses across four cohorts with pulse pressure measurement and variant rs201988637 available, with the risk lowering allele associated with lower pulse pressure (p = 1.7 × 10−04, β = −0.13 [−0.2 to −0.06]) (Fig. 7). Association with pulse pressure was also tested for inframe insertion rs534125149 and previously reported common variant in the locus, rs8042271 across all where the variants were available. We saw consistent effect sizes across the cohorts, and significant (p < 0.05) meta-analysis p-values for both variants (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Fig. 7. Results for pulse pressure association across all cohorts with splice acceptor variant rs201988637 available (FINRISK, GeneRISK, YFS, EstBB, and UKBB).

Size of the boxes represent the sample size of the cohorts, and the lines the 95% confidence interval. Associations were tested using linear regression, adjusting for age and sex Pulse pressure phenotypes were inverse-rank normalized prior analysis. Source data for the figure is in Supplementary Data 1.

In addition, in recent studies for blood pressure measurements (systolic and diastolic blood pressure and pulse pressure), genome-wide significant association have been reported in the region15,16. To assess whether these reflects the same signal, we performed colocalization analysis in the region ±200 kB around rs53412514 using Coloc package in R17 with coronary atherosclerosis results from FinnGen and pulse pressure GWAS results from Evangelou et al.16 The probability for shared signal (PP4) was 97.1%, further validating MFGE8 locus is associated with pulse pressure (Supplementary Fig. 10).

In addition to pulse pressure associations in the region, rs534125149 was significantly associated with height, but further analysis pointed this signal to be reflecting the association of a known association of ACAN with height, located near MFGE8 (Supplementary Fig. 11). No associations with other risk factors were observed.

In the Corogene cohort (n = 4896), rs534125149 was significantly (p < 0.05) associated with lower risk for acute coronary syndrome and stable coronary heart disease (RR = 0.87 and 0.83, respectively) compared to healthy controls, but not with myocardial infarction without coronary artery occlusion (Supplementary Fig. 12). These results are in line with our findings regarding the specificity of the association of variants in MFGE8 on atherosclerotic cardiovascular disorders. The p-value for the difference of the AFs of rs534125149 among patients with acute coronary syndrome or stable coronary heart disease and among MINOCA was, however, not significant (p = 0.78), which may due to lack of power. In addition, the cohort is very heterogeneous.

Previously reported common variants near MFGE8

Previously, common intergenic variant (rs8042271) near MFGE8 has been reported to associate with coronary heart disease (CHD) risk3,18. We replicate this association (OR = 0.90, p = 3.69 × 10−10 for coronary atherosclerosis) in FinnGen. LD between the common variant rs8042271 and the inframe insertion rs534125149 is 0.154. The LD characteristics for all three variants in MFGE8 (rs534125149, rs201988637 and rs8042271) in FinnGen are in Supplementary Table 4. Common variant rs8042271 was in the 95% credible set for MI with the causal probability of 0.003 but was not included in the 95% credible sets for coronary atherosclerosis (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6). The conditional analyses of all three MFGE8 variants showed that the association of the previously reported common variant rs8042271 can be explained by the inframe insertion variant rs534125149, but not vice versa, and that the association of the splice acceptor variant rs201988637 is independent of both rs534125149 and rs8042271. (Supplementary Table 7). This was the case also with previously reported common variant rs734780, showing very similar LD with rs534125149 (0.112) as rs8042271 (0.154).

Fine-mapping of the MFGE8 locus

In our fine-mapping analyses, MI had most probably one credible set (set of causal variants) of 32 variants with the highest posterior probability (posterior probability = 0.62), and coronary atherosclerosis had two credible sets of 6 and 45 variants, respectively, with the highest posterior probability (posterior probability = 0.74). For both MI and coronary atherosclerosis, rs534125149 had the highest probability of being causal (probability of being causal = 0.250 and 0.318, respectively) and was included in the first credible set (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6; and Supplementary Fig. 13). Splice acceptor variant rs201988637 was not included in the credible sets for either MI or coronary atherosclerosis, whereas previously reported common variant rs8042271 was included in the credible set for MI with the probability of being causal = 0.003 (Supplementary Table 6).

Protein modeling

We predicted the impact of the insertion variant rs534125149 on the protein structure of MFGE8 using AlphaFold19. The predicted conformational changes were localized to a loop region within the C2 domain, ~20 Å away from the key amino acids involved in membrane binding (Supplementary Fig. 14)20,21. This loop contains Asn238, which is known to be glycosylated22. It is possible that the insertion of an additional asparagine may lead to impaired glycosylation, which is important for protein folding, among other cellular processes23. The role of this region in the function of MFGE8 hasn’t been previously described and it is therefore unclear how this variant would otherwise lead to an impact on MFGE8 function. Thus, further experimental work is necessary to understand the mechanism by which this variant leads to protection against coronary atherosclerosis.

Discussion

Here, we show that a Finnish enriched inframe insertion in MFGE8 is associated with substantially lower risk of diseases representing major CHD, including myocardial infarction and coronary atherosclerosis. This variant was associated with CHD specifically, and no significant association was observed to other diseases in a phenome-wide search, even if this can be due to lower statistical power in rare disease endpoints. Splice acceptor variant rs201988637 in MFGE8 was also associated with lower pulse pressure, but not with blood lipids, blood pressure or other known coronary heart disease risk factors.

Our findings allow us to draw several conclusions. First, MFGE8 is a potential intervention target with specific effects on coronary heart disease. Specific protective association with the variants in MFGE8 and CHD shows potential for efficacy of a treatment targeting MFGE8 protein or downstream products. Second, the lack of risk elevation in other diseases provide evidence on the potential safety of the intervention. Previously, the protective effect of loss-of-function variants have been reported for example for PCSK95 and APOC36, and in phase I, II and III trials, inhibition of PCSK9 have led to significantly decreased LDL-C levels, and in short-term trials, PCSK9 inhibitors have been well-tolerated and have had a low incidence of adverse effects24 Based on the phenome-wide association profile for the splice acceptor variant rs201988637, we hypothesize that inhibiting MFGE8 could lower the CHD risk, if the variant can be proved to be loss-of-function in MFGE8.

An association of a splice acceptor variant rs201988637 in MFGE8 with lower pulse pressure, a potential biomarker for arterial stiffness25, are very much in line with previous studies on MFGE8 and the inflammatory aging process of the arteries, highlighting the possible role of MFGE8 in arterial aging and stiffness. The MFGE8 gene encodes Milk-fat globule-EGF 8 (MFGE8), or lactadherin, which is an integrin-binding glycoprotein implicated in vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation and invasion, and the secretion of pro-inflammatory molecules26,27. Lactadherin is known to play important roles in several other biological processes, including apoptotic cell clearance and adaptive immunity28, which are known to contribute to the pathogenesis of ischemic stroke. Initially lactadherin was identified as a bridging molecule between apoptotic cells and phagocytic macrophages29–31, but growing evidence has indicated that it is a secreted inflammatory mediator that orchestrates diverse cellular interactions involved in the pathogenesis of various diseases, including vascular metabolic disorders and some tumors32–36 and cancers, such as breast34,37, bladder38, esophageal39 and colorectal cancer40. Recently, not only has MFG-E8 expression emerged as a molecular hallmark of adverse cardiovascular remodeling with age41–44, but MFG-E8 signaling has also been found to mediate the vascular outcomes of cellular and matrix responses to the hostile stresses associated with hypertension, diabetes, and atherosclerosis45–49.

Arterial inflammation and remodeling are linked to the pathogenesis of age-associated arterial diseases, such as atherosclerosis. Recently, lactadherin has been identified as a novel local biomarker for aging arterial walls by high-throughput proteomic screening, and it has been shown to also be an element of the arterial inflammatory signaling network50. The transcription, translation, and signaling levels of MFG-E8 are increased in aged, atherosclerotic, hypertensive, and diabetic arterial walls in vivo, as well as activated VSMCs and a subset of macrophages in vitro. During aging, both MFG-E8 transcription and translation increase within the arterial walls and hearts of various species, including rats, humans, and monkeys44,51–53, and MFG-E8 is markedly up-regulated in rat aortic walls with aging44. High levels of MFG-E8 have also been detected within endothelial cells, SMC, and macrophages of atherosclerotic aortae in both mice and humans49,54. Furthermore, in the advanced atherosclerotic plaques found in murine models, decreased macrophage MFG-E8 levels are associated with an inhibition of apoptotic cell engulfment, leading to the accumulation of cellular debris during the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Lactadherin has, however, in contrast shown tissue protection in various models of organ injury, including suppression of inflammation and apoptosis in intestinal ischemia in mice55, as well as inducing recovery from ischemia by facilitating angiogenesis56.

In addition, expression of MFGE8 is highly enriched to tissues relevant to the reported association, such as aorta. Genes nearby MFGE8, including ABHD2 and HAPLN3, are, however similarly to MFGE8 enriched to arteries18. Therefore, they could play a role in atherosclerosis via coordinated gene network. In addition, recent studies have pointed toward the fact that lncRNA, called CARMAL, may regulate the expression of MFGE857.

Our study does, however, have a few limitations. First, our primary association results come from Finnish population with considerable elevation in allele frequency in MFGE8 variants among Finns. Therefore, the replication of the association in other populations has reduced statistical power. However, there were enough carriers combined in Japanese, Estonian and UK samples to replicate robustly both the protective association with coronary heart disease and for pulse pressure. Secondly, although our data shows association with pulse pressure, which has previously been linked to arterial stiffness, the direct effect of the genetic variants on arterial stiffness and arterial aging needs further evidence. Lastly, with our dataset, we have not been able to demonstrate that the two variants (rs534125149 and rs201988637) in MFGE8 are loss-of-function variants, and thus further experimental work is required to validate our findings.

In conclusion, our results suggests that inhibiting production of lactadherin could reduce the risk for coronary atherosclerosis substantially and thus present MFGE8 as a potential therapeutical target for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Our study also highlights the potential of FinnGen, as a large-scale biobank study in isolated population to identify high-impact variants either very rare or absent in other populations.

Methods

Study cohort and data

We studied total of 2 861 disease endpoints in Finnish biobank study FinnGen (n = 260 405) (Table 3). FinnGen (https://www.finngen.fi/en) is a large biobank study that aims to genotype 500,000 Finns and combine this data with longitudinal registry data, including national hospital discharge, death, and medication reimbursement registries, using unique national personal identification numbers. FinnGen includes prospective epidemiological and disease-based cohorts as well as hospital biobank samples.

Table 3.

Basic characteristics of the study cohort.

| All | Females | Males | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 260,405 | 147,061 (56.47%) | 113,344 (43.53%) |

| Age (mean (sd)) | 53.15 (17.55) | 51.84 (17.71) | 54.85 (17.19) |

| BMI (mean (sd))a | 27.29 (5.36) | 27.21 (5.83) | 27.38 (4.76) |

| Statin use (N (%)) | 86,466 (33.2%) | 40,422 (27.48%) | 46,044 (40.62%) |

| Hypertension (N (%)) | 68,005 (26.11%) | 33,420 (22.72%) | 34,585 (30.51%) |

| Smoking (N (%))b | 1733 (1.07%) | 901 (0.96%) | 832 (1.22%) |

| Coronary atherosclerosis | 28,598 (11.38%) | 9252 (6.87%) | 19,346 (17.86%) |

| Myocardial infarction | 14,305 (6.04%) | 3958 (2.87%) | 10,347 (10.42%) |

aBMI is available only from 178,966 individuals.

bSmoking information is available only from 98,654 individuals.

Definition of disease endpoints

All the 2861 disease-endpoint analyzed in FinnGen have been defined based on registry linkage to national hospital discharge, death, and medication reimbursement registries. Diagnoses are based on International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes and have been harmonized over ICD codes 8, 9, and 10. More detailed lists of the ICD codes used for the disease-endpoints myocardial infarction and coronary atherosclerosis, which are discussed more in this study, are in Supplementary Note 1. A complete list of endpoints analyzed, and their definitions is available at https://www.finngen.fi/en/researchers/clinical-endpoints.

Genotyping and imputation

FinnGen samples were genotyped with multiple Illumina and Affymetrix arrays (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Genotype calls were made with GenCall and zCall algorithms for Illumina and AxiomGT1 algorithm for Affymetrix chip genotyping data batchwise. Genotyping data produced with previous chip platforms were lifted over to build version 38 (GRCh38/hg38) following the protocol described here: dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.nqtddwn. Samples with sex discrepancies, high-genotype missingness (>5%), excess heterozygosity (±4SD) and non-Finnish ancestry were removed. Variants with high missingness (>2%), deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (p < 1 × 10−6) and low minor allele count (MAC < 3) were removed.

Pre-phasing of genotyped data was performed with Eagle 2.3.5 (https://data.broadinstitute.org/alkesgroup/Eagle/) with the default parameters, except the number of conditioning haplotypes was set to 20,000. Imputation of the genotypes was carried out by using the population-specific Sequencing Initiative Suomi (SISu) v3 imputation reference panel with Beagle 4.1 (version 08Jun17.d8b, https://faculty.washington.edu/browning/beagle/b4_1.html) as described in the following protocol: dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.nmndc5e. SISu v3 imputation reference panel was developed using the high-coverage (25–30x) whole-genome sequencing data generated at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and at the McDonnell Genome Institute at Washington University, USA; and jointly processed at the Broad Institute. Variant callset was produced with Genomic Analysis Toolkit (GATK) HaplotypeCaller algorithm by following GATK best practices for variant calling. Genotype-, sample- and variant-wise quality control was applied in an iterative manner by using the Hail framework v0.2. The resulting high-quality WGS data for 3775 individuals were phased with Eagle 2.3.5 as described above. As a post-imputation quality control, variants with INFO score <0.7 were excluded.

Association testing and replication

A total of 260,405 samples from FinnGen Data Freeze 6 with 2861 disease endpoints were analyzed using Scalable and Accurate Implementation of Generalized mixed model (SAIGE), which uses saddlepoint approximation (SPA) to calibrate unbalanced case-control ratios58. Models were adjusted for age, sex, genotyping batch and first ten principal components. All variants reaching genome-wide significance p-value threshold of 5 × 10−8 are considered as genome-wide significant (GWS), and all disease-endpoints reaching multiple testing corrected (for the number of endpoints tested = 2861) p-value threshold of 0.05/2861 = 1.75 × 10−5 were considered as phenome-wide significant (PWS).

Independent GWS loci for atherosclerosis were determined as adding ±0.5 Mb around each variant that reached the genome-wide significance threshold, overlapping regions were merged. The publicly available summary statistics from CARDIoGRAMplusC4D, a large meta-analysis of CHD involving 60,801 cases and 123,504 controls3 was used for assessing whether the locus has been previously reported to associate with CHD. In addition, NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog10 was used for assessing whether the locus has been previously reported to associate with any CVD-related endpoint or traditional risk factor for CVD, such as blood lipids, BMI and blood pressure. All loci that had not been reported to associate with CVD were fine-mapped using FINEMAP59 to determine the credible sets in each signal, and meta-analyzed across the cohorts (UKBB, EstBB and BBJ) where available to test their novelty.

In Corogene60 (n = 5300), a sub-cohort of FinnGen where participants have been collected as patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) and other related heart diseases, we tested the association of rs534125149 with sub-types of coronary heart disease: acute coronary syndrome, stable coronary heart disease (CHD) and MINOCA61 (myocardial infarction no coronary artery occlusion), by which we refer to patients that have had symptoms, ECG-changes and cardiac enzyme or troponine release suggesting acute coronary syndrome, but did not have coronary stenosis. The acute coronary syndrome was further divided into unstable Angina pectoris, non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Associations were tested by calculating risk ratios (RR) for carriers vs. non-carriers of rs534125149 using non-CHD group always as controls and excluding the other tested groups from the analysis. p-values were calculated using χ2-test, and p-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Survival analysis

Survival analysis for coronary atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction was performed using GATE62, which accounts for both population structure and sample relatedness and controls type I error rates even for phenotypes with extremely heavy censoring. GATE transforms the likelihood of a multivariate Gaussian frailty model to a modified Poisson generalized linear mixed model (GLMM63,64), and to obtain well-calibrated p-values for heavily censored phenotypes, GATE uses the SPA to estimate the null distribution of the score statistic. For coronary atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction, survival time from birth to first diagnose was analyzed for both rs534125149 and rs201988637. Models were adjusted for age, sex, genotyping batch and first ten principal components, similarly to original GWAS analyses. In addition, cox-proportional hazards model was used for survival analysis for coronary atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction using a binary variable (carrier or non-carrier) for either inframe insertion rs534125149 or splice acceptor variant rs201988637.

Biomarker analyses

We tested the association of the two MFGE8 variants (rs534125149 and rs201988637) with quantitative measurements of cardiometabolic relevance or known risk factors for CVD in two sub-cohorts of FinnGen, the population-based national FINRISK study65 (n = 26,717) and GeneRISK66 (n = 7239). The associations were tested across 66 quantitative measurements of cardiometabolic relevance in FINRISK, and for 158 sub-lipid species in GeneRISK. In Young Finns Study (YFS)67 cohort (n = 1934), we tested the association of the two variants with three measurements of arterial relevance (carotid artery distensibility, pulse wave velocity, and pulse pressure).

In addition to Finnish cohorts described above, we tested the association of the two variants in Estonian Biobank data (EstBB)14,68, BioBank Japan (BBJ)12,13, and UK Biobank (UKBB)69. In EstBB (n = 51,388–137,722) we tested the associations of both variants with body mass index (BMI), systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP) and pulse pressure (PP), in BBJ in we tested the association of rs534125149 with 17 known quantitative risk factors for CVD and lastly, in the UKBB we tested the association of rs201988637 with 79 measurements of cardiometabolic relevance. In all of these biomarker analyses, a linear regression model adjusted for age and sex was used and for all quantitative risk factors rank-based inverse normal transformation was applied prior to analysis. Bonferroni corrected p-value threshold for the number of phenotypes tested was used to assess the significance of resulting associations in each cohort.

For biomarkers that showed significant association in any of the cohorts, we performed a meta-analysis across all cohorts the measurement was available. Meta-analysis was performed using inverse-variance weighted fixed-effects meta-analysis method70,71. Bonferroni corrected p-value for number of traits tested (n = 2) was used to assess the significance of resulting associations in meta-analysis.

Height association

To assess whether the association of rs534125149 with height was due to the MFGE8 gene, we first performed conditional analysis of height conditioning the association for rs534125149, the lead variant in FinnGen height GWAS (rs11630187) and for previously known height-associated variant in the locus, rs1694234172, separately. Conditioning the height association on rs534125149 did not have much effect on the association of the lead variant for height (rs11630187) in the region (p-value before conditioning = 5.07 × 10−34 and after conditioning = 1.19 × 10−26), whereas when conditioning on the lead variant for height (rs11630187) in the region, the smallest p-value in the region was 1.39 × 10−15 (for variant rs28564751). In addition, conditioning on either known height-associated variant rs16942341 or lead variant for height in FinnGen (rs11630187) did not affect on rs534125149’s association with height (p-value before conditioning = 8.04 × 10−13 and after conditioning = 3.14 × 10−12 and 2.75 × 10−05, respectively)

In addition, to assess whether the association of rs534125149 with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and height reflect the same signal, we performed colocalization analysis in the region ±200kB around rs53412514 using Coloc package in R. The probability for shared signal (PP4) was 9.22 × 10−13, whereas probability for two independent (PP3) signals was 1, indicating two independent signals for height and coronary atherosclerosis in the locus.

Identifying causal variants

We used FINEMAP59 on the GWAS summary statistics to identify causal variants underlying the associations for MI (strict definition, i.e., only primary diagnoses accepted) and coronary atherosclerosis. FINEMAP analyses were restricted to a ±1.5 Mb region around the rs534125149. We assessed variants in the top 95% credible sets, i.e., the sets of variants encompassing at least 95% of the probability of being causal (causal probability) within each causal signal in the genomic region. Credible sets were filtered if minimum linkage disequilibrium (LD, r2) between the variants in the credible set was <0.1, i.e., not clearly representing one signal.

Protein modeling

The predicted structure of lactadherin was obtained from AlphaFold19 (https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/entry/Q08431). Model confidence for the domain containing the variant of interest was scored mostly as very high and was structurally similar to the crystal structure of bovine lactadherin21 (PDB ID:2PQS). The structure of the insertion variant rs534125149 was predicted using the AlphaFold Colab notebook (https://colab.research.google.com/github/deepmind/alphafold/blob/main/notebooks/AlphaFold.ipynb). Protein structures were visualized using PyMOL73.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants of all study cohorts for their generous participation. We also want to thank Dr. Kaoru Ito at RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences for supporting the study. This work was supported by the Academy of Finland Center of Excellence in Complex Disease Genetics (Grant No 312062 and 336820 to S.R.), the Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research, the Sigrid Juselius Foundation, University of Helsinki HiLIFE Fellow, Grand Challenge grants and Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (grant number 101016775 “INTERVENE” to S.R.), Academy of Finland grant number 331671 to N.M., the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund (Project No. 2014-2020.4.01.16-0125 to L.M.), the Estonian Research Council grant PRG184 [to L.M.] and the Doctoral Programme in Population Health, University of Helsinki [to S.E.R.]. The FinnGen project is funded by two grants from Business Finland (HUS 4685/31/2016 and UH 4386/31/2016) and the following industry partners: AbbVie Inc., AstraZeneca UK Ltd, Biogen MA Inc., Celgene Corporation, Celgene International II Sàrl, Genentech Inc., Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp, Pfizer Inc., GlaxoSmithKline Intellectual Property Development Ltd., Sanofi US Services Inc., Maze Therapeutics Inc., Janssen Biotech Inc, and Novartis AG. Following biobanks are acknowledged for deliverig biobank samples to FinnGen: Auria Biobank (www.auria.fi/biopankki), THL Biobank (www.thl.fi/biobank), Helsinki Biobank (www.helsinginbiopankki.fi), Biobank Borealis of Northern Finland (https://www.ppshp.fi/Tutkimus-ja-opetus/Biopankki/Pages/Biobank-Borealis-briefly-in-English.aspx), Finnish Clinical Biobank Tampere (www.tays.fi/en-US/Research_and_development/Finnish_Clinical_Biobank_Tampere), Biobank of Eastern Finland (www.ita-suomenbiopankki.fi/en), Central Finland Biobank (www.ksshp.fi/fi-FI/Potilaalle/Biopankki), Finnish Red Cross Blood Service Biobank (www.veripalvelu.fi/verenluovutus/biopankkitoiminta) and Terveystalo Biobank (www.terveystalo.com/fi/Yritystietoa/Terveystalo-Biopankki/Biopankki/). All Finnish Biobanks are members of BBMRI.fi infrastructure (www.bbmri.fi) and FinBB (https://finbb.fi/).

Author contributions

S.E.R. and S.R. designed the study; S.E.R. and J.K. performed the analyses; S.E.R., I.S., N.M., E.W., M.J.D., and S.R. performed interpretation of data; S.E.R., I.S., and S.R. drafted the manuscript; all authors read the manuscript before submission; M. Kanai, K.K., P.P.M., B.H.M. performed analysis for replication cohorts, S.G. performed the protein modeling, M.J.D., J.S., P.P., T.L., O.R., Y.O., L.M., and A.P. provided administrative or material support.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. This article has been peer reviewed as part of Springer Nature’s Guided Open Access initiative.

Data availability

Full GWAS results are publicly available through FinnGen PheWEB browser (r6.finngen.fi) and also at Open Targets website. The Finnish biobank data can be accessed through the Fingenious® services (web link: https://site.fingenious.fi/en/, email: contact@finbb.fi) managed by FINBB. The UK Biobank resource is available to bona fide researchers for health-related research in the public interest at https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/researchers/. The BBJ summary statistics are available at the National Bioscience Database Center (NBDC) Human Database (accession code: hum0197) and at the GWAS catalog (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/home). They are also browseable at our PheWeb website (https://pheweb.jp/). The variant rs534125149 was originally excluded from the publicly available GWAS summary statistics. Its associations were reported in Supplementary Fig. 4. The BBJ genotype data is accessible on request at the Japanese Genotype–phenotype Archive (http://trace.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/jga/index_e.html) with accession code JGAD00000000123 and JGAS00000000114. Genotype and phenotype data from the Estonian Biobank are available (https://genomics.ut.ee/en/biobank.ee/data-access) upon request. The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article were obtained from the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study, which comprises health-related participant data. The use of data is restricted under the regulations on professional secrecy (Act on the Openness of Government Activities, 612/1999) and on sensitive personal data (Personal Data Act, 523/1999, implementing the EU data protection directive 95/46/EC). Owing to these restrictions, the data cannot be stored in public repositories or otherwise made publicly available. Data access may be permitted on a case-by-case basis upon request only. Data sharing outside the group is done in collaboration with YFS group and requires a data-sharing agreement. Investigators can submit an expression of interest to the chairman of the publication committee Professor Mika Kähönen (Tampere University, Finland) or Professor Terho Lehtimäki (Tampere University, Finland).

Code availability

The full genotyping and imputation protocol for FinnGen is described at dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.nmndc5e. The code used for the analyses in this paper are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

Patients and control subjects in FinnGen provided informed consent for biobank research, based on the Finnish Biobank Act. Alternatively, separate research cohorts, collected prior the Finnish Biobank Act came into effect (in September 2013) and start of FinnGen (August 2017), were collected based on study-specific consents and later transferred to the Finnish biobanks after approval by Fimea, the National Supervisory Authority for Welfare and Health. Recruitment protocols followed the biobank protocols approved by Fimea. The Coordinating Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa (HUS) approved the FinnGen study protocol Nr HUS/990/2017. The FinnGen study is approved by Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (permit numbers: THL/2031/6.02.00/2017, THL/1101/5.05.00/2017, THL/341/6.02.00/2018, THL/2222/6.02.00/2018, THL/283/6.02.00/2019, THL/1721/5.05.00/2019, THL/1524/5.05.00/2020, and THL/2364/14.02/2020), Digital and population data service agency (permit numbers: VRK43431/2017-3, VRK/6909/2018-3, VRK/4415/2019-3), the Social Insurance Institution (permit numbers: KELA 58/522/2017, KELA 131/522/2018, KELA 70/522/2019, KELA 98/522/2019, KELA 138/522/2019, KELA 2/522/2020, KELA 16/522/2020 and Statistics Finland (permit numbers: TK-53-1041-17 and TK-53-90-20). The Biobank Access Decisions for FinnGen samples and data utilized in FinnGen Data Freeze 6 include: THL Biobank BB2017_55, BB2017_111, BB2018_19, BB_2018_34, BB_2018_67, BB2018_71, BB2019_7, BB2019_8, BB2019_26, BB2020_1, Finnish Red Cross Blood Service Biobank 7.12.2017, Helsinki Biobank HUS/359/2017, Auria Biobank AB17-5154, Biobank Borealis of Northern Finland_2017_1013, Biobank of Eastern Finland 1186/2018, Finnish Clinical Biobank Tampere MH0004, Central Finland Biobank 1-2017, and Terveystalo Biobank STB 2018001. The FINRISK data used for the study were obtained from THL Biobank with application number BB2015_55.1 and UKBB data using the UK Biobank Resource with application number 22627. The study was approved by the Estonian Committee on Bioethics and Human Research (approval number 1.1-12/624).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lists of authors and their affiliations appear at the end of the paper.

Contributor Information

Samuli Ripatti, Email: samuli.ripatti@helsinki.fi.

Estonian Biobank Research Team:

Tõnu Esko, Andres Metspalu, Reedik Mägi, and Mari Nelis

The Biobank Japan Project:

Koichi Matsuda, Yuji Yamanashi, Yoichi Furukawa, Takayuki Morisaki, Yoshinori Murakami, Yoichiro Kamatani, Kaori Muto, Akiko Nagai, Wataru Obara, Ken Yamaji, Kazuhisa Takahashi, Satoshi Asai, Yasuo Takahashi, Takao Suzuki, Nobuaki Sinozaki, Hiroki Yamaguchi, Shiro Minami, Shigeo Murayama, Kozo Yoshimori, Satoshi Nagayama, Daisuke Obata, Masahiko Higashiyama, Akihide Masumoto, and Yukihiro Koretsune

FinnGen:

Aarno Palotie, Mark Daly, Bridget Riley-Gills, Howard Jacob, Dirk Paul, Heiko Runz, Sally John, Robert Plenge, Mark McCarthy, Julie Hunkapiller, Meg Ehm, Kirsi Auro, Caroline Fox, Anders Mälarstig, Katherine Klinger, Deepak Raipal, Tim Behrens, Robert Yang, Richard Siegel, Tomi Mäkelä, Jaakko Kaprio, Petri Virolainen, Antti Hakanen, Terhi Kilpi, Markus Perola, Jukka Partanen, Anne Pitkäranta, Juhani Junttila, Raisa Serpi, Tarja Laitinen, Johanna Mäkelä, Veli-Matti Kosma, Urho Kujala, Outi Tuovila, Raimo Pakkanen, Justin Wade Davis, Danjuma Quarless, Slavé Petrovski, Eleonor Wigmore, Adele Mitchell, Benjamin Sun, Ellen Tsai, Denis Baird, Paola Bronson, Ruoyu Tian, Yunfeng Huang, Joseph Maranville, Elmutaz Mohammed, Samir Wadhawan, Erika Kvikstad, Minal Caliskan, Diana Chang, Tushar Bhangale, Kirill Shkura, Victor Neduva, Xing Chen, Åsa Hedman, Karen S. King, Padhraig Gormley, Jimmy Liu, Clarence Wang, Ethan Xu, Franck Auge, Clement Chatelain, Deepak Rajpal, Dongyu Liu, Katherine Call, Tai-He Xia, Matt Brauer, Huilei Xu, Amy Cole, Jonathan Chung, Jaison Jacob, Katrina de Lange, Jonas Zierer, Mitja Kurki, Aki Havulinna, Juha Mehtonen, Priit Palta, Shabbeer Hassan, Pietro Della Briotta Parolo, Wei Zhou, Mutaamba Maasha, Susanna Lemmelä, Manuel Rivas, Arto Lehisto, Vincent Llorens, Mari E. Niemi, Henrike Heyne, Kimmo Palin, Javier Garcia-Tabuenca, Harri Siirtola, Tuomo Kiiskinen, Jiwoo Lee, Kristin Tsuo, Kati Kristiansson, Kati Hyvärinen, Jarmo Ritari, Miika Koskinen, Katri Pylkäs, Marita Kalaoja, Minna Karjalainen, Tuomo Mantere, Eeva Kangasniemi, Sami Heikkinen, Samuel Heron, Dhanaprakash Jambulingam, Venkat Subramaniam Rathinakannan, Nina Pitkänen, Lila Kallio, Sirpa Soini, Eero Punkka, Teijo Kuopio, Marco Hautalahti, Laura Mustaniemi, Mirkka Koivusalo, Sarah Smith, and Tom Southerington

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-022-03552-0.

References

- 1.Kessler T, Erdmann J, Schunkert H. Genetics of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction-2013. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2013;15:368. doi: 10.1007/s11886-013-0368-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Donnell CJ, Nabel EG. Genomics of cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:2098–2109. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1105239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nikpay M, et al. A comprehensive 1000 Genomes–based genome-wide association meta-analysis of coronary artery disease. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:1121. doi: 10.1038/ng.3396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim, E. T. et al. Distribution and medical impact of loss-of-function variants in the Finnish founder population. PLoS Genet.10, e1004494 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Cohen JC, Boerwinkle E, Mosley TH, Jr, Hobbs HH. Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:1264–1272. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.TG and HDL Working Group of the Exome Sequencing Project, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Loss-of-function mutations in APOC3, triglycerides, and coronary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:22–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1307095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dewey FE, et al. Inactivating variants in ANGPTL4 and risk of coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;374:1123–1133. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Libby P, et al. Atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2019;5:56. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0106-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karczewski KJ, et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581:434–443. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buniello A, et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;47:D1005–D1012. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nurnberg ST, et al. Genomic profiling of human vascular cells identifies TWIST1 as a causal gene for common vascular diseases. PLoS Genet. 2020;16:e1008538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagai A, et al. Overview of the BioBank Japan Project: study design and profile. J. Epidemiol. 2017;27:S2–S8. doi: 10.1016/j.je.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakaue, S. et al. A global atlas of genetic associations of 220 deep phenotypes. Preprint at medRxiv10.1101/2020.10.23.20213652 (2021).

- 14.Leitsalu L, et al. Cohort profile: Estonian biobank of the Estonian genome center, university of Tartu. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015;44:1137–1147. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffmann TJ, et al. Genome-wide association analyses using electronic health records identify new loci influencing blood pressure variation. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:54–64. doi: 10.1038/ng.3715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evangelou E, et al. Genetic analysis of over 1 million people identifies 535 new loci associated with blood pressure traits. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:1412–1425. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0205-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giambartolomei C, et al. Bayesian test for colocalisation between pairs of genetic association studies using summary statistics. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soubeyrand S, et al. Regulation of MFGE8 by the intergenic coronary artery disease locus on 15q26. 1. Atherosclerosis. 2019;284:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.AlQuraishi M. AlphaFold at CASP13. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:4862–4865. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersen MH, Graversen H, Fedosov SN, Petersen TE, Rasmussen JT. Functional analyses of two cellular binding domains of bovine lactadherin. Biochemistry (N. Y.) 2000;39:6200–6206. doi: 10.1021/bi992221r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin L, Huai Q, Huang M, Furie B, Furie BC. Crystal structure of the bovine lactadherin C2 domain, a membrane binding motif, shows similarity to the C2 domains of factor V and factor VIII. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;371:717–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Picariello G, Ferranti P, Mamone G, Roepstorff P, Addeo F. Identification of N‐linked glycoproteins in human milk by hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2008;8:3833–3847. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200701057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helenius A, Aebi M. Intracellular functions of N-linked glycans. Science. 2001;291:2364–2369. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5512.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dadu RT, Ballantyne CM. Lipid lowering with PCSK9 inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2014;11:563. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benetos A, et al. Mortality and cardiovascular events are best predicted by low central/peripheral pulse pressure amplification but not by high blood pressure levels in elderly nursing home subjects: the PARTAGE (Predictive Values of Blood Pressure and Arterial Stiffness in Institutionalized Very Aged Population) study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012;60:1503–1511. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oshima K, et al. Lactation-dependent expression of an mRNA splice variant with an exon for a multiplyO-glycosylated domain of mouse milk fat globule glycoprotein MFG-E8. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;254:522–528. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aoki N, et al. Immunologically cross-reactive 57 kDa and 53 kDa glycoprotein antigens of bovine milk fat globule membrane: isoforms with different N-linked sugar chains and differential glycosylation at early stages of lactation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) 1994;1200:227–234. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(94)90140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deroide N, et al. MFGE8 inhibits inflammasome-induced IL-1β production and limits postischemic cerebral injury. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:1176–1181. doi: 10.1172/JCI65167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanayama R, et al. Identification of a factor that links apoptotic cells to phagocytes. Nature. 2002;417:182–187. doi: 10.1038/417182a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanayama R, et al. Autoimmune disease and impaired uptake of apoptotic cells in MFG-E8-deficient mice. Science. 2004;304:1147–1150. doi: 10.1126/science.1094359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshida H, et al. Phosphatidylserine-dependent engulfment by macrophages of nuclei from erythroid precursor cells. Nature. 2005;437:754–758. doi: 10.1038/nature03964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tahara H, et al. Emerging concepts in biomarker discovery; the US-Japan Workshop on Immunological Molecular Markers in Oncology. J. Transl. Med. 2009;7:1–25. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neutzner M, et al. MFG-E8/lactadherin promotes tumor growth in an angiogenesis-dependent transgenic mouse model of multistage carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6777–6785. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor MR, Couto JR, Scallan CD, Ceriani RL, Peterson JA. Lactadherin (formerly BA46), a membrane-associated glycoprotein expressed in human milk and breast carcinomas, promotes Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD)-dependent cell adhesion. DNA Cell Biol. 1997;16:861–869. doi: 10.1089/dna.1997.16.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jinushi M, et al. Milk fat globule EGF-8 promotes melanoma progression through coordinated Akt and twist signaling in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8889–8898. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raymond A, Ensslin MA, Shur BD. SED1/MFG‐E8: a bi‐motif protein that orchestrates diverse cellular interactions. J. Cell. Biochem. 2009;106:957–966. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu L, et al. MFG-E8 overexpression is associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer patients. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2019;215:490–498. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2018.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sugano G, et al. Milk fat globule—epidermal growth factor—factor VIII (MFGE8)/lactadherin promotes bladder tumor development. Oncogene. 2011;30:642–653. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanemura T, et al. Immunoregulatory influence of abundant MFG‐E8 expression by esophageal cancer treated with chemotherapy. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:3393–3402. doi: 10.1111/cas.13785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jia M, et al. Prognostic correlation between MFG-E8 expression level and colorectal Cancer. Arch. Med. Res. 2017;48:270–275. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang M, Khazan B, Lakatta G. E. Central arterial aging and angiotensin II signaling. Curr. Hypertens. Rev. 2010;6:266–281. doi: 10.2174/157340210793611668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang M, Monticone RE, Lakatta EG. Arterial aging: a journey into subclinical arterial disease. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2010;19:201. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283361c0b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ortiz A, et al. Clinical usefulness of novel prognostic biomarkers in patients on hemodialysis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2012;8:141. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fu Z, et al. Milk fat globule protein epidermal growth factor-8: a pivotal relay element within the angiotensin II and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 signaling cascade mediating vascular smooth muscle cells invasion. Circ. Res. 2009;104:1337–1346. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.187088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bagnato C, et al. Proteomics analysis of human coronary atherosclerotic plaque: a feasibility study of direct tissue proteomics by liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2007;6:1088–1102. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600259-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li X, et al. Proteomics approach to study the mechanism of action of grape seed proanthocyanidin extracts on arterial remodeling in diabetic rats. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2010;25:237–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strøm CC, et al. Identification of a core set of genes that signifies pathways underlying cardiac hypertrophy. Comp. Funct. Genomics. 2004;5:459–470. doi: 10.1002/cfg.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin Y, et al. Comparative proteomic analysis of rat aorta in a subtotal nephrectomy model. Proteomics. 2010;10:2429–2443. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ait-Oufella H, et al. Clinical perspective. Circulation. 2007;115:2168–2177. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.662080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang M, Wang H, Lakatta G. Milk fat globule epidermal growth factor VIII signaling in arterial wall remodeling. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2013;11:768–776. doi: 10.2174/1570161111311050014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peng S, Glennert J, Westermark P. Medin-amyloid: a recently characterized age-associated arterial amyloid form affects mainly arteries in the upper part of the body. Amyloid. 2005;12:96–102. doi: 10.1080/13506120500107006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peng S, et al. Medin and medin‐amyloid in ageing inflamed and non‐inflamed temporal arteries. J. Pathol. 2002;196:91–96. doi: 10.1002/path.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grant JE, et al. Quantification of protein expression changes in the aging left ventricle of Rattus norvegicus. J. Proteome Res. 2009;8:4252–4263. doi: 10.1021/pr900297f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bagnato C, et al. Proteomics analysis of human coronary atherosclerotic plaque: a feasibility study of direct tissue proteomics by liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2007;6:1088–1102. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600259-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheyuo C, et al. Recombinant human MFG-E8 attenuates cerebral ischemic injury: its role in anti-inflammation and anti-apoptosis. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:890–900. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Silvestre J, et al. Lactadherin promotes VEGF-dependent neovascularization. Nat. Med. 2005;11:499–506. doi: 10.1038/nm1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soubeyrand S, et al. CARMAL Is a Long Non-coding RNA Locus That Regulates MFGE8 Expression. Front. Genet. 2020;11:631. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou W, et al. Efficiently controlling for case-control imbalance and sample relatedness in large-scale genetic association studies. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:1335–1341. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0184-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Benner C, et al. FINEMAP: efficient variable selection using summary data from genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:1493–1501. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vaara S, et al. Cohort profile: the Corogene study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012;41:1265–1271. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Collet J, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur. Heart J. 2021;42:1289–1367. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dey, R. et al. An efficient and accurate frailty model approach for genome-wide survival association analysis controlling for population structure and relatedness in large-scale biobanks. bioRxiv (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Breslow NE, Clayton DG. Approximate inference in generalized linear mixed models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1993;88:9–25. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen H, et al. Control for population structure and relatedness for binary traits in genetic association studies via logistic mixed models. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;98:653–666. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Borodulin K, et al. Forty-year trends in cardiovascular risk factors in Finland. Eur. J. Public Health. 2014;25:539–546. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Widén E, et al. How communicating polygenic and clinical risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease impacts health behavior: an observational follow-up study. Circulation: Genomic and Precision Medicine. 2022;15:e003459. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGEN.121.003459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Raitakari OT, et al. Cohort profile: the cardiovascular risk in Young Finns Study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2008;37:1220–1226. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mitt M, et al. Improved imputation accuracy of rare and low-frequency variants using population-specific high-coverage WGS-based imputation reference panel. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;25:869. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2017.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bycroft C, et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018;562:203. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cooper, H., Hedges, L. V. & Valentine, J. C. in The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-analysis (Russell Sage Foundation, 2019).

- 71.Evangelou E, Ioannidis JP. Meta-analysis methods for genome-wide association studies and beyond. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013;14:379–389. doi: 10.1038/nrg3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lango HA, et al. Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature. 2010;467:832–838. doi: 10.1038/nature09410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.DeLano WL. Pymol: an open-source molecular graphics tool. CCP4 Newslet. Protein Crystallogr. 2002;40:82–92. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Full GWAS results are publicly available through FinnGen PheWEB browser (r6.finngen.fi) and also at Open Targets website. The Finnish biobank data can be accessed through the Fingenious® services (web link: https://site.fingenious.fi/en/, email: contact@finbb.fi) managed by FINBB. The UK Biobank resource is available to bona fide researchers for health-related research in the public interest at https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/researchers/. The BBJ summary statistics are available at the National Bioscience Database Center (NBDC) Human Database (accession code: hum0197) and at the GWAS catalog (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/home). They are also browseable at our PheWeb website (https://pheweb.jp/). The variant rs534125149 was originally excluded from the publicly available GWAS summary statistics. Its associations were reported in Supplementary Fig. 4. The BBJ genotype data is accessible on request at the Japanese Genotype–phenotype Archive (http://trace.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/jga/index_e.html) with accession code JGAD00000000123 and JGAS00000000114. Genotype and phenotype data from the Estonian Biobank are available (https://genomics.ut.ee/en/biobank.ee/data-access) upon request. The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article were obtained from the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study, which comprises health-related participant data. The use of data is restricted under the regulations on professional secrecy (Act on the Openness of Government Activities, 612/1999) and on sensitive personal data (Personal Data Act, 523/1999, implementing the EU data protection directive 95/46/EC). Owing to these restrictions, the data cannot be stored in public repositories or otherwise made publicly available. Data access may be permitted on a case-by-case basis upon request only. Data sharing outside the group is done in collaboration with YFS group and requires a data-sharing agreement. Investigators can submit an expression of interest to the chairman of the publication committee Professor Mika Kähönen (Tampere University, Finland) or Professor Terho Lehtimäki (Tampere University, Finland).

The full genotyping and imputation protocol for FinnGen is described at dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.nmndc5e. The code used for the analyses in this paper are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.