Abstract

The Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean (ASSO) has one of the highest densities of Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) compared to other polar and subpolar regions, which attracts migratory baleen whale species to aggregate in this area for feeding. Humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) also sing extensively while on the Southern Ocean feeding grounds which allows for the exploration of song similarity between feeding grounds and breeding populations which helps to understand population mixing. The results of comparative song analyses between the ASSO and the Ecuadorian and Brazilian breeding populations and recordings from the Chilean, South African and Namibian migration routes/mid-latitude feeding grounds revealed that individuals from at least three humpback whale breeding populations most likely migrate to shared feeding grounds in the ASSO. Humpback whales from different populations potentially mix at different times (i.e., years) at feeding hotspots in variable locations. The ASSO seems to provide sufficient prey resources and seems to present an important area for both cultural and maybe even genetic exchange between populations supporting the maintenance of large gene pools. Assuming that multi-population feeding hotspots are also suitable habitat for krill and other krill-dependent predators, these areas in the ASSO should be carefully managed integrating population, ecosystem and fisheries management.

Subject terms: Conservation biology, Population dynamics, Behavioural ecology

Introduction

Humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) populations of the Southern Hemisphere are known to aggregate in low latitude breeding areas which are confined by continental barriers (at least in one longitudinal direction)1. Due to maternally directed site fidelity, humpback whales usually return every year to their natal breeding ground, dividing Southern Hemisphere humpback whales into at least six distinct breeding populations1. The connectivity among these breeding populations usually correlates with the geographical distance between the areas, but most likely also depends on the degree of longitudinal movements of individuals within the Southern Ocean2–5. Humpback whales are flexible in their ecological requirements and are able to adapt to environmental change with alternative migration and feeding strategies5–9. Specific feeding areas, for example, can be visited during most years, but are abandoned during years with exceptional climatic conditions10. This migratory plasticity facilitates the mixing of populations within feeding aggregations allowing for cultural and genetic exchange3,5,11,12.

Baleen whale populations, and particularly their recovery from past whaling depletion, are managed by the International Whaling Commission (IWC). The IWC lists the identification of breeding/feeding ground migratory linkages and connections as a priority research topic to improve conservation and management efforts for Southern Hemisphere humpback whales13. These linkages can be identified by satellite tagging individual whales, using photographic mark-recapture, or comparing genetic markers or songs of individual whales between regions5,14,15. The songs of male humpback whales can be recorded mainly during late autumn, winter, and early spring (i.e., shortly before, during and shortly after the breeding period of humpback whales) and are highly similar among males within a breeding population, but are (to some extent) distinct among males from different breeding populations14,16. Especially for areas with restricted access, such as the Southern Ocean, the possibility of investigating migratory linkages between breeding and feeding grounds through the comparison of population-specific humpback whale songs is a great advance for humpback whale population monitoring4,12,17,18. The availability of long-term passive acoustic monitoring data from the Southern Ocean and the discovery that humpback whales sing extensively while on the Southern Ocean feeding grounds and migration routes12,19–21 now allows for the exploration of song similarity between breeding and feeding grounds which can be used as an indicator for population mixing4,17,22.

The Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean (ASSO) is regularly frequented by humpback whales and its Northern limit (i.e., in the vicinity of the Antarctic Polar Front) is especially suitable feeding habitat for humpback whales10,23–25. At least two distinct humpback whale breeding populations have been found to visit and overlap within the ASSO5,12,26 and a high similarity in songs from South Atlantic breeding areas suggests occasional mixing of populations, potentially on a common feeding ground4. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of how many and which humpback whale populations mix in the ASSO, this study aims to conduct comparative analysis of humpback whale songs from the ASSO and available temporally matching song recordings from the Ecuadorian (breeding stock G27) and Brazilian (breeding stock A27) breeding grounds and the Chilean, Namibian, and western South African migration routes/mid-latitude feeding grounds (of breeding stocks G and B, respectively; assumed migratory connections by the IWC27). We discuss the temporal flexibility in the migration and mixing of humpback whales from three populations and highlight the importance of mixing areas for the viability of recovering baleen whale populations and Southern Ocean pelagic ecosystem.

Material and methods

Data and processing

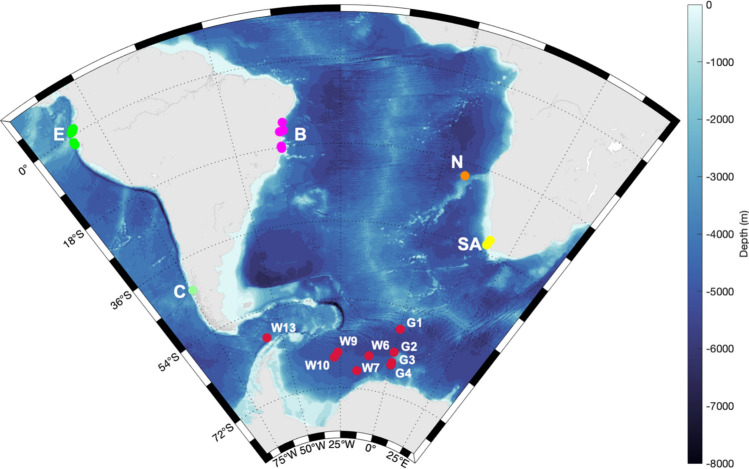

A prerequisite for comparative song analysis is the temporal proximity of the song recordings which are to be compared (i.e., songs from the same years or from previous or following seasons) due to the evolutionary nature of humpback whale songs28,29. Therefore, we gathered feeding ground, breeding ground, and migration route/mid-latitude feeding ground song recordings from 2011 to 2019 for the comparative analyses. Recordings were conducted either with stationary autonomous recording devices which were moored to the seafloor or with portable hydrophones which were submerged from a boat in the vicinity of humpback whales12,30–32. We extracted high quality humpback whale songs (i.e., signal-to-noise ratio ≥ 10 dB and at least two discernible distinct themes, meaning two distinct combinations of vocalizations which are usually repeated multiple times and therefore form a rhythmic song12,33) from passive acoustic recordings collected in the ASSO, off Ecuador, Chile, Brazil, Namibia, and South Africa using a range of recording setups (Fig. 1, Table 1). In the two breeding areas, Ecuador and Brazil, recordings were conducted at multiple locations which sometimes changed during recordings (due to the boat drifting with the current), therefore the larger area where recordings were conducted is defined by the latitude and longitude limits provided in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Bathymetric map with recording locations in the Atlantic, Pacific and Southern Ocean: Greenwich Meridian (G1–4), Weddell Sea (W6–13), Ecuador (E, green), Chile (C, light green), Brazil (B, pink), Namibia (N, orange), South Africa (SA, yellow). Recording locations marked with a red dot, in sum, represent the recordings from the Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean (ASSO). Map was generated with M_MAP in MATLAB34.

Table 1.

Details of passive acoustic recordings from the six regions: Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean (ASSO), Ecuador, Chile, Brazil, South Africa, Namibia.

| Location | Latitude | Longitude | Recording device | Digitalization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASSO |

66° 36.45′ S 66° 30.708′ S 66° 2.01′ S 65° 58.092′ S 63° 59.846′ S 61° 1.071′ S 59° 2.823′ S |

27° 7.26′ W 0° 1.512′ E 0° 3.117′ E 12° 15.12′ W 0° 1.842′ E 55° 58.686′ W 0° 5.775′ E |

SonoVaults (Develogic GmbH, Hamburg) | 5333–9600 Hz |

| Ecuador | 1° 7.3293′ N to 1° 48.5′ S | 79° 43.9392′ W to 81° 6.92′ W |

H2a-XLR omnidirectional hydrophone DolphinEar/PRO hydrophone |

44,100 Hz |

| Chile | 43° 31.889′ S | 74° 26.488′ W | Marine Autonomous Recording Units (MARUs) | 2000 Hz |

| Brazil | 14° 28.6671′ S to 18° 13.9536′ S | 38° 0.5052′ W to 39° 0.6865′ W |

Archival bottom-mounted Oceanpods Tascam DR40/HTI 96 min Zoom H4nPro/Aquarium Audio H2a M-Audio Inc. Micro track II |

11,000–48,000 Hz |

| South Africa |

34° 9.3396′ S 32° 46.1346′ S |

18° 17.7′ E 17° 52.0656′ E |

SoundTrap (Ocean Instruments, NZ) | 48,000 Hz |

| Namibia | 20° 57.90′ S | 5° 58.82′ E | SonoVaults (Develogic GmbH, Hamburg) | 5333 Hz |

Latitudes and longitudes specified with “to” describe an area where recordings have been conducted at many different locations.

Humpback whale vocalizations were manually logged within the spectrograms in Raven Pro (Hann Window, 1025–8057 window size, 80% overlap, 2048–8192 DFT size35). Logged vocalizations were manually classified into distinct unit types and subtypes (call types: CT followed by a number; subtypes: CT followed by a number and a lower case letter) according to the following criteria: (1) differentiation of tonal or broadband characteristics, (2) duration, (3) time–frequency slope and (4) frequency range (vocalizations having the same characteristics regarding criteria (1) to (3) but were encountered in different frequency ranges, were classified into subtypes). Within a humpback whale song sequence, phrases were logged and classified according to unit repetition following the recommendations of Cholewiak et al.33. Phrase types were identified with an uppercase letter (indicating the 1st unit type), a lowercase letter (indicating the combination of following unit types) and a sequence of numbers (indicating the number of repetitions of each unit).

The manual subjective analysis of unit repertoire was tested in terms of robustness by applying an automated classification approach to a subset of units (436 exemplar units with at least 20 exemplars per unit type sampled from different locations and days of recording36). We computed 44 different acoustic metrics for every extracted unit (i.e., 3 s sound file decimated to 5000 Hz to ensure comparability). The 44 metrics can be described as belonging to either of these three categories: (1) indices based on different algorithms to compute acoustic complexity, entropy or diversity (acoustic indices), (2) metrics measuring amplitude or background patterns (energy metrics), and (3) metrics computing ratios between acoustic activity over time and frequency bands (ratio metrics). Details on the acoustic metrices used and the process of computation for the 436 sound examples can be found in Schall et al.36. The 44 acoustic metrices for each extracted unit were used in a random forest supervised machine learning approach36 to discriminate between manually classified unit types.

To assess inter- and intra-individual song differences, first, individual singers were differentiated. For recordings made with a dipping hydrophone, individual singers were differentiated in the field by human observers. For autonomous recordings, spatio-temporal assumptions were applied to allocate presumed individual singers (for details on assumptions, see12). Second, the start and end of an explicit song had to be defined. Inspecting our song sequence data for common patterns, the most sensible definition for song was the complete rendition of all unique theme types per song sequence to form an explicit humpback whale song33.

Song repertoire and structure comparison

The phrase repertoires of geographic groups (i.e., ASSO, Ecuador, Chile, Brazil, Namibia, South Africa) were first clustered by year, and in case of the ASSO, by song group with the data from 2013 split into song group 1 and 2 because these song groups had 0% similarity in previous analyses12. Repertoires of these clusters were compared by applying the Dice Coincidence Index (DCI) with a custom-written script in R37,38:

with A being the number of shared phrase types between a pair of singers, B and C being the number of phrase types of each singer, respectively. The resulting similarity matrix was subjected to a hierarchical cluster analysis in R38 using the “average linkage” method and the output was visualized in a dendrogram. Hierarchical clustering was bootstrapped (1000 times) with the R function ‘pvclust’39 to generate approximate unbiased (AU) values with AU values exceeding 95% indicating dendrogram divisions that are likely to occur.

To compare the song structure (the order of themes within a song) among geographic groups, the sequences of phrases were transcribed to sequences of themes (ignoring the repetition of phrases) and a set median string was chosen for each individual singer. The set median string was defined as the sequence of themes which had the highest similarity to all sequences of themes of a given set. The similarity between sequences was calculated by applying the Levenshtein Distance Similarity Index (LSI) in MATLAB40,41:

with a and b being the two theme sequences, I being insertions, D being deletions, S being substitutions and L being the length of the respective sequence. In the following, the set median strings of the breeding grounds (i.e., Ecuador and Brazil) were clustered per year and a set median string was chosen from each location-year cluster applying the same method as above. The songs recorded in the ASSO and on the migration routes/mid-latitude feeding grounds were all included in the comparative analyses (without reduction to a representative theme sequence per year) due to the unknown number of breeding populations that potentially contributed to the recordings.

Humpback whale songs from the distinct geographic groups were compared for each year of ASSO song recordings including also breeding ground or migration route/mid-latitude feeding ground songs from the year before or after, by applying the LSI to pairs of individuals/clusters with the R function ‘stringdist’42. The resulting similarity matrix was subjected to a hierarchical cluster analysis using the “average linkage” method, the output was visualized in a dendrogram, and hierarchical clustering was bootstrapped (1000 times)38,39.

Results

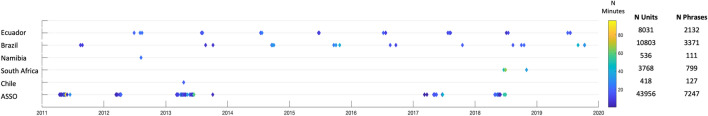

We analyzed humpback whale songs from the ASSO, Brazil, Ecuador, South Africa, Chile, and Namibia for on average 3 individual singers per year and location (between one and 25 individual singers per year and location; see supplementary material I for list of analyzed songs). Fewer individual singers per year and location were only considered if more data was not available (Fig. 2). In the case of the ASSO, songs from as many individual singers as possible were analyzed (10–25 per year) because an unknown number of breeding populations could have contributed to these songs. In the ASSO, data collection in 2014 failed so that no acoustic recordings could be analyzed and in the years 2015 and 2016, passive acoustic data were collected, but did not contain any humpback whale songs (see12 for more details and possible explanations). From the different individual singers between one and 95 min (on average 16.4 min) of humpback whale song were analyzed, depending on the availability of good quality song sequences (Fig. 2). In total, 67,512 song units were classified into 15 distinct unit types, plus seven subtypes, and 13,787 phrases were classified into 114 distinct phrase types (see supplementary material II for catalogue of unit and phrase types). The level of agreement between the manual unit classification and the result of the supervised machine learning approach was high with a general ‘Out-of-bag’ misclassification rate of 16% indicating a robust differentiation of units, phrases, themes and songs (see36 for more detailed results).

Figure 2.

Timeline of song recordings from the six recording locations. Each diamond marks the date of recording of one or multiple individual singers. The color of the diamond represents the number of minutes of analyzed song. For each location, the number of classified units and phrases is listed next to the timeline.

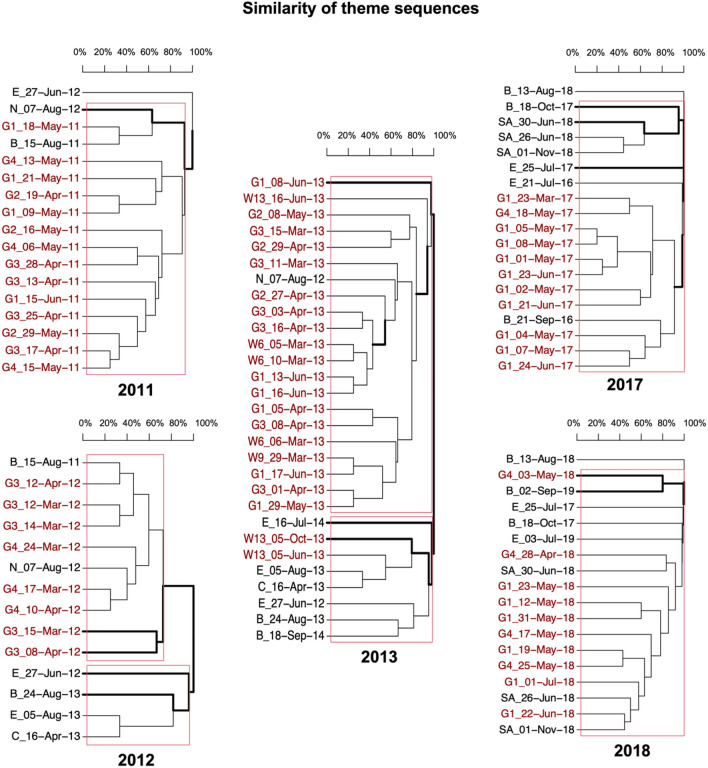

Humpback whale songs from the ASSO shared phrase types with all the breeding and migration route/mid-latitude feeding ground songs included in the comparative analyses (Ecuador, Chile, Brazil, South Africa, and Namibia). The comparison of phrase repertoires revealed a high overlap (> 80%) between the ASSO song group 2 repertoire recorded off Elephant Island and the Ecuadorian and Chilean repertoires in 2013 (‘ASSO_2_2013’, ‘E_1_2013’, and ‘C_1_2013’; Fig. 3). Humpback whale songs from the ASSO in 2017 shared almost 60% of the phrase types with the songs recorded off Brazil in 2016 (‘ASSO_1_2017’ and ‘B_1_2016’; Fig. 3), while the ASSO songs from 2018 shared 70% of the phrase types with the South African songs from the same year (‘ASSO_1_2018’ and ‘SA_1_2018’). The ASSO repertoires from 2011, 2012, and 2013 had some overlap (> 27%) with the repertoires recorded off Namibia in 2012 and Brazil in 2011 (‘ASSO_1_2011’, ‘ASSO_1_2012’, ‘ASSO_1_2013’, ‘B_1_2011’, and ‘N_1_2012’; Fig. 3). Brazilian repertoires from 2014, 2015, 2019 and repertoires from Ecuador 2012, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019 clustered separately indicating no or little (< 10%) overlap with phrase repertoires from the ASSO.

Figure 3.

Bootstrapped dendrogram from hierarchical clustering of the similarity of phrase repertoires (dice coincidence index) for humpback whale songs from the Atlantic sector of the Souther Ocean (ASSO), the Ecuadorian breeding population (E), the Brazilian breeding population (B), and the South African (SA), Chilean (C) and Namibian (N) migration routes/mid-latitude feeding grounds for all recording years. Phrase repertoires were compared as summarized repertoires per location and year. ASSO recordings from 2013 are represented as two repertoires, due to the clear differentiation of two song groups12. The names on each branch indicate the location (e.g., ‘E’ for Ecuador, ‘B’ for Brazil, and ‘SA’ for South Africa), the repertoire ID (e.g., ‘1’, ‘2’), and the year (e.g., ‘2017’) to identify the respective phrase repertoire. Bold lines indicate divisions that were likely to occur (i.e., approximate unbiased value > 95%) and red rectangles indicate clusters of significant probability.

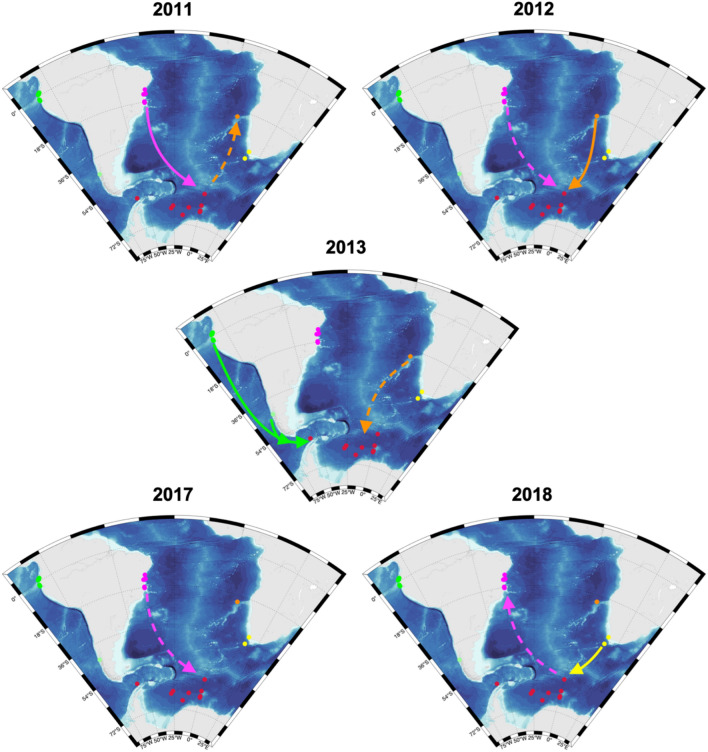

Song structures, represented by theme sequences in the ASSO also showed similarities to songs recorded at all locations included in the comparative analyses, depending on the year of recording. In 2011, the songs recorded from one individual in the ASSO were 70% similar to the songs recorded off Brazil in the same year and 40% similar to the songs recorded off Namibia the year after (Fig. 4). This degree of similarity indicates that humpback whales from the Brazilian breeding population migrated to the ASSO feeding area, more specifically to the area around the Greenwich Meridian, and returned to the waters off Brazil in winter (Fig. 5). This is also evident from the comparative analyses of the 2012 data, where the 70% of song similarity between the Greenwich recordings and the Brazilian recordings from 2011 indicate acoustic contact in 2012 or 2011 (Figs. 4, 5). Humpback whales from the offshore Namibian migration route, visited the ASSO in 2012 and potentially also in 2011 and/or 2013, indicated by theme sequence similarities between 30 and 50% (Figs. 4, 5). The hierarchical cluster of the 2012 data also shows a connection between Ecuadorian and Brazilian song with a higher similarity between the Brazilian and Ecuadorian song from 2013 than between the Ecuadorian song from 2012 and 2013 (Fig. 4), which implies an event of acoustic contact between these populations in 2012, potentially in the ASSO. The 2013 data shows that the songs of two individuals recorded off Elephant Island (i.e., ‘W13_05-Jun-2013’ and ‘W13_05-Oct-2013’ representing song group 2 from Schall et al.12) were the most similar to the songs recorded off Ecuador and Chile in the same year. This indicates that humpback whales from the Ecuadorian breeding population and Chilean migration route/mid-latitude feeding ground visited the area around Elephant Island, at least during this particular year (Figs. 4, 5). All other song recordings from the ASSO in 2013 were clustered together with the song recording from Namibia in 2012 and separately from Ecuadorian, Chilean, and Brazilian song recordings (Fig. 4). Therefore, only humpback whales from the west African breeding population (here represented by the offshore Namibian migration route recordings) contributed to the prevalent song group 1 recorded throughout the entire ASSO (i.e., song group 1 from Schall et al.12). All the songs recorded in the ASSO during 2017 and 2018 were partly similar (i.e., 20%) to Brazilian songs from 2016 and 2019, but almost completely different (i.e., < 5%) from the Brazilian songs from 2017 and 2018 (Fig. 4), indicating acoustic contact between the Brazilian breeding population and the ASSO before 2017 and after 2018 (Fig. 5). The songs recorded in the ASSO in 2018 instead were similar (17–57%) to the songs recorded off South Africa during the same year, indicating a direct migratory link between these two locations (Figs. 4, 5).

Figure 4.

Bootstrapped dendrograms from hierachical clustering of similarity of theme sequences of humpback whales songs (Levensthein distance similarity index) from the Atlantic sector of the Souther Ocean (ASSO: reprsented by recording positions G and W), the Ecuadorian breeding population (E), the Brazilian breeding population (B), and the South African (SA), Chilean (C) and Namibian (N) migration routes/mid-latitude feeding grounds for the five different years of song recordings from the ASSO. Names on each branch belong to individual singers in case of the ASSO and migration route/mid-latitude feeding ground recordings, or representative theme sequence in case of breeding population recordings encoded with the name of the recording position (first 2–3 symbols, e.g., ‘W13’, ‘G4’, ‘SA’,…) and the date of the recording (last 9 symbols, e.g., ‘28-Apr-18’, ‘01-Nov-18’,…). Bold lines indicate divisions that were likely to occur (approximate unbiased value > 95%) and red rectangles indicate clusters of significant probability.

Figure 5.

Schematic illustration of potential humpback whale song transmission pathways between the Atlantic sector of the Souther Ocean (ASSO: red dots) and the Ecuadorian breeding population (green dots), the Brazilian breeding population (magenta dots), and the Chilean (light green dots), South African (yellow dots), and Namibian (orange dots) migration routes/mid-latitude feeding grounds indicated by comparative song analyses. Red dots indicate recording positions in the ASSO. Arrows illustrate the likely pathways of acoustic contact between humpback whales recorded at the different locations for the same year. Southward facing dashed arrows illustrate likely acoustic contact either during the same year or the year before and northward facing dashed arrows illustrate a likely acoustic contact either in the same year or the year after. Maps were generated with M_MAP in MATLAB34.

Discussion

Overall, the comparative song analyses showed that humpback whales from the west African (represented by the animals recorded off South Africa and Namibia), Ecuadorian and Brazilian breeding populations had acoustic contact to humpback whales recorded in the ASSO, most likely because at least some members of these breeding populations migrate to a shared feeding ground in the ASSO. In the case of the ASSO, the comparative analysis of songs seems to be a promising and useful tool to study migratory connections and mixing patterns among breeding populations.

These results confirm the previous suggestion by Darling and Sousa-Lima4 and the findings presented in Schall et al.12 of the presence of humpback whales from at least two breeding populations feeding in the ASSO, and presents evidence for the migration of at least three breeding populations to the ASSO feeding area. Indications of mixing in the ASSO were observed in multiple years and therefore was not a single event (see also4,5). For humpback whales from the South Atlantic breeding populations, the ASSO has been assumed to be the primary feeding ground43–45. Additionally, the results confirm the suggested cultural exchange among humpback whales from the Ecuadorian breeding population and humpback whales from various South Atlantic breeding populations which all migrate to the ASSO where their habitat ranges overlap spatially5. Within this context, it is also possible that humpback whales from other breeding populations than those included in these comparative song analyses (e.g., humpback whales breeding in the Southwestern Indian Ocean), migrate to the ASSO and contributed to the encountered variabilities in song recordings. Future studies could examine circum-Antarctic patterns of song exchange among humpback whale breeding populations at a broader scale by applying the same methods which are presented here. Cultural exchange in terms of song learning requires whales to be within a relatively short distance of each other. Maximum detection range of songs is estimated to be 50 km in the ASSO25 although animals likely need to be < 10 km apart to be able to fully perceive all frequency components of the song46. These values suggest that individual whales from different populations must be within the required spatial vicinity of each other for song exchange, a behavior that also ultimately favors crossbreeding among populations11.

Mixing patterns seem to be temporally variable, meaning that whales from different populations potentially mix at different times (i.e., years or months) at feeding hotspots of variable locations. Based on the acoustic similarities, humpback whales from the Brazilian breeding population, for example, are likely to have visited the area around the Greenwich Meridian in the ASSO during 2011, 2016, and 2019. However, no similarity between songs from Brazil and the ASSO was found for 2013 and 2018. The flexibility of these mixing processes is most likely connected to variations in migratory patterns driven by spatio-temporal changes in prey availability5,47,48. Optimizing their energy budgets, humpback whales from different breeding populations are likely to migrate to those areas with sufficient prey availability that lie closest to the respective breeding ground49. Baleen whales are thought to employ a multi-modal sensory system combining magnetoreception, somatosensory perception of oceanographic conditions, chemosensory cues as well as acoustic perception of conspecifics or other marine animals to find prey hotspots50,51. Humpback whales can detect and localize social vocalizations and songs of conspecifics over tens of kilometers52,53 which allows humpback whales to relatively flexibly navigate to ephemeral prey hotspots following acoustic way markers. Humpback whale song produced at feeding hotspots might serve the purpose of attracting more individuals to these hotspots in order to promote nutrition of females and calves (i.e., to promote receptivity in females and assure survival of kin) and increase chances of reproduction with potentially receptive females16. Additionally, individual whales were also observed to migrate to or towards a different breeding ground, where cultural and genetic exchange could take place54; www.happywhale.com55–57.

Within the Southern Ocean, a high krill availability in the ASSO may attract humpback whales from different breeding populations and favors mixing among the different populations11. On average, the polar and subpolar regions of the South Atlantic Ocean (i.e., including the ASSO) have the highest densities of Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) on a circumpolar scale58,59. The locations of krill hotspots in the Southern Ocean vary on intra- and interannual temporal scales and are driven by sea ice, oceanographic, and climatological dynamics60–62. In contrast to the whales of the Northern Hemisphere, migratory baleen whales from the Southern Hemisphere are not restricted by continental barriers at high latitudes and can therefore choose feeding locations over a large longitudinal range11,15,63. As our results suggest, even humpback whales from two different ocean basins migrate to the ASSO to feed and potentially reproduce. This mixing of multiple humpback whale populations in the ASSO is also supported by genetic analyses of individuals sampled in the ASSO in comparison to individuals sampled in the rest of the Southern Ocean, where no significant genetic differentiation (i.e., mitochondrial and microsatellite) was found between areas11.

Humpback whales from most Southern Hemisphere breeding populations are recovering well from past overexploitation through industrial whaling27 and areas, such as the ASSO where multiple breeding populations feed in mixed aggregations could be of key importance to the positive population trends recorded during the past decade. Two important factors which ensure the prosperity of a population are linked to the ASSO: (1) the ASSO provides sufficient prey resources to allow population growth64–67, and (2) the ASSO is an important area for both cultural and maybe even genetic exchange between populations supporting the maintenance of large gene pools which increase the populations’ resilience to environmental change11. Our results clearly suggest that multiple humpback whale populations visit the ASSO during the feeding season and that cultural exchange in form of song learning is taking place in this region.

Combining these multiple lines of evidence, the ecological relevance of the ASSO for humpback whales from multiple populations is clear, while it seems also clear that other locations can become relevant in this context when considering potential future environmental changes, e.g., more frequent El Niño events68. Contemporary multi-population humpback whale hotspots in the ASSO, as the eastern and western edges of the ASSO along the polar front (i.e., areas around the recording locations G1 and W13 from this study), should be carefully managed by integrating population, ecosystem and fishery management strategies led by the IWC and the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR). Since the spatiotemporal distribution of humpback whales in the ASSO is most likely driven mainly by the availability and distribution of their primary prey species69, it is safe to assume that humpback whale hotspots reflect areas with high krill densities (although whales may target specific age and size classes representing only part of the krill population70). In addition to the importance of the ASSO for multiple humpback whale populations, humpback whale feeding hotspots in the ASSO could therefore also indicate areas of importance for Antarctic krill, the keystone species of the Southern Ocean, and other krill-dependent predator species71. Due to this overlap and the role of baleen whales in structuring the Southern Ocean pelagic ecosystem72, the creation of a marine protected area (i.e., the Weddell Sea MPA73) including humpback whale hotspots could be an effective management strategy beneficial to single species, ecosystem processes, as well as fisheries74.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Develogic GmbH, Hamburg, to the logistics department of the Alfred Wegener Institute, Bremerhaven, the mooring team of the AWI’s physical oceanography department, to Reederei F. Laeisz GmbH, Rostock, and the crews of RV Polarstern expeditions ANT-XXVII/2, ANT-XXIX/2, PS89, PS103 for their contribution to the development, setup or maintenance of the passive acoustic recording array in the ASSO. Also, thanks to Rafael Murakami and Fernando Murakami from Água Viva Sub and Erik Tedesco for the planning, organization and implementation of the fieldwork in Serra Grande (Bahia, Brazil).

Author contributions

E.S. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. D.D., E.R.-M., J.O., J.D., J.E.B., L.R.P., M.R.R.-S., M.I.C.G., R.S.-L., R.H.-G., S.E., S.B., and T.G. collected data and reviewed the manuscript. Conceptualization was partly done by E.S. and I.V.O., as well as D.D. I.V.O. coordinated the study, collected part of the data and helped draft the manuscript. All the authors gave the final approval for publication.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Brazilian data collection was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior-Brasil (CAPES)-Finance Code 001, the Cetacean Society International, the Rufford Foundation, the Instituto Baleia Jubarte, Arim Components and an anonymous donor. RSL thanks the Brazilian Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq-Brazil) for her research fellowship (process number 312763/2019-0). DD received a CAPES Ph.D. scholarship (file no. 88882.344054/2019-01). MICG received a scholarship from CAPES and other from State University of Santa Cruz. South Africa data collection was largely funded by the SA National Research Foundation for equipment and salary for SE and ERM, TG was funded by a Claude Leon Post-Doctoral Fellowship. The data collection in Ecuador was financed by the Rufford Foundation and the COCIBA Grants from Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ) and through the contributions of volunteers and scientists from the CETACEA Ecuador Project. The data collection was carried out with research permits (008-2012-IC-FLO-FAU-DPE-MA; MAE-DPAE-2013-0677; MAE-DPAE-2014-0723; MAE-DPAE-2016-0850; MAE-DPAE-017-2017; MAE-DPAE-2019-0687-O) by the Environmental, Water and Ecological Transition Ministry, Ecuador (MAATE). SJB thanks the support of COPAS Sur-Austral (ANID AFB170006) and COPAS Coastal (ANID FB210021).

Data availability

Analyses reported in this article can be reproduced using the data provided by Schall (2021) at Data Dryad: https://datadryad.org/stash/share/Vfg14Wkti-rXiDZWqIAJX7cdHGxFqUiPUUOWIWx5h6E.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-17999-y.

References

- 1.Clapham PJ. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Elsevier; 2018. pp. 489–492. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calambokidis J, et al. Movements and population structure of humpback whales in the North Pacific. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2001;17:769–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2001.tb01298.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenbaum HC, et al. First circumglobal assessment of Southern Hemisphere humpback whale mitochondrial genetic variation and implications for management. Endangered Species Res. 2017;32:551–567. doi: 10.3354/esr00822. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darling JD, Sousa-Lima RS. Songs indicate interaction between humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) populations in the western and eastern South Atlantic Ocean. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2005;21:557–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2005.tb01249.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcondes MCC, et al. The Southern Ocean Exchange: Porous boundaries between humpback whale breeding populations in southern polar waters. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:23618. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02612-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witteveen BH, Foy RJ, Wynne KM, Tremblay Y. Investigation of foraging habits and prey selection by humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) using acoustic tags and concurrent fish surveys. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2008;24:516–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2008.00193.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barendse J, et al. Migration redefined? Seasonality, movements and group composition of humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae off the west coast of South Africa. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 2010;32:1–22. doi: 10.2989/18142321003714203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Findlay KP, et al. Humpback whale “super-groups” – A novel low-latitude feeding behaviour of Southern Hemisphere humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the Benguela Upwelling System. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0172002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barendse J, et al. Transit station or destination? Attendance patterns, movements and abundance estimate of humpback whales off west South Africa from photographic and genotypic matching. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 2011;33:353–373. doi: 10.2989/1814232X.2011.637343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schall E, et al. Multi-year presence of humpback whales in the Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean but not during El Niño. Commun. Biol. 2021;4:1–7. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02332-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amaral AR, et al. Population genetic structure among feeding aggregations of humpback whales in the Southern Ocean. Mar. Biol. 2016;163:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00227-016-2904-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schall E, et al. Humpback whale song recordings suggest common feeding ground occupation by multiple populations. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-98295-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.International Whaling Commission. Annex H: Report of the Sub-Committee on Other Southern Hemisphere Whale Stocks. (2016).

- 14.Payne R, Guinee LN. Humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) songs as an indicator of “stocks”. Commun. Behav. Whales. 1983;20:333–358. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riekkola L, et al. Application of a multi-disciplinary approach to reveal population structure and Southern Ocean feeding grounds of humpback whales. Ecol. Indic. 2018;89:455–465. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.02.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herman LM. The multiple functions of male song within the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) mating system: Review, evaluation, and synthesis. Biol. Rev. 2017;92:1795–1818. doi: 10.1111/brv.12309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garland EC, et al. Humpback Whale song on the Southern Ocean feeding grounds: Implications for cultural transmission. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McSweeney D, Chu K, Dolphin W, Guinee L. North Pacific humpback whale songs: A comparison of southeast Alaskan feeding ground songs with Hawaiian wintering ground songs. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 1989;5:139–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.1989.tb00328.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Opzeeland IC, et al. Towards collective circum-antarctic passive acoustic monitoring: The southern ocean hydrophone network (SOHN) Polarforschung. 2013;83:47–61. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gridley T, Silva M, Wilkinson C, Seakamela S, Elwen SH. Song recorded near a super-group of humpback whales on a mid-latitude feeding ground off South Africa. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2018;143:298–304. doi: 10.1121/1.5032126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ross-Marsh E, Elwen SH, Prinsloo A, James B, Gridley T. Singing in South Africa: Monitoring the occurrence of humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) song near the Western Cape. Bioacoustics. 2021;30:163–179. doi: 10.1080/09524622.2019.1710254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garland EC, et al. Population structure of humpback whales in the western and central South Pacific Ocean as determined by vocal exchange among populations. Conserv. Biol. 2015;29:1198–1207. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bombosch A, et al. Predictive habitat modelling of humpback (Megaptera novaeangliae) and Antarctic minke (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) whales in the Southern Ocean as a planning tool for seismic surveys. Deep Sea Res. Part 1 Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2014;91:101–114. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2014.05.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Gabbas A, Van Opzeeland I, Burkhardt E, Boebel O. Static species distribution models in the marine realm: The case of baleen whales in the Southern Ocean. Divers. Distrib. 2021;27:1536–1552. doi: 10.1111/ddi.13300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schall E, et al. Large-scale spatial variabilities in the humpback whale acoustic presence in the Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020;7:201347. doi: 10.1098/rsos.201347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.International Whaling Commission. Report of the scientific committee. Annex G. Report of the sub-committee on comprehensive assessment of southern hemisphere humpback whales. Appenix4. Initial alternative hypotheses for the distribution of humpack breeding stocks on the feeding grounds. Report of the International Whlaing Commission48, 181 (1998).

- 27.International Whaling Commission Report on the workshop on the comprehensive assessment of Southern Hemisphere humpback whales. J. Cetacean Res. Manage. Spec. Issue. 2011;3:1–50. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winn HE, Winn LK. Song of Humpback Whale Megaptera-Novaeangliae in West-Indies. Mar. Biol. 1978;47:97–114. doi: 10.1007/Bf00395631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Payne K, Payne R. Large-scale changes over 19 years in songs of Humpback Whales in Bermuda. Z. Tierpsychol. 1985;68:89–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.1985.tb00118.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomisch K, et al. Temporal patterns in the acoustic presence of baleen whale species in a presumed breeding area off Namibia. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2019;620:201–214. doi: 10.3354/meps12952. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buchan SJ, Stafford KM, Hucke-Gaete R. Seasonal occurrence of southeast Pacific blue whale songs in southern Chile and the eastern tropical Pacific. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2015;31:440–458. doi: 10.1111/mms.12173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ross-Marsh E, Elwen S, Prinsloo A, James B, Gridley T. Singing in South Africa: Monitoring the occurrence of humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) song near the Western Cape. Bioacoustics. 2020 doi: 10.1080/09524622.2019.1710254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cholewiak DM, Sousa-Lima RS, Cerchio S. Humpback whale song hierarchical structure: Historical context and discussion of current classification issues. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2013;29:E312–E332. doi: 10.1111/mms.12005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.M_Map: A Mapping Package for MATLAB v. 1.4m. (2020).

- 35.Raven Pro: Interactive sound analysis software. Version 1.6 ([Ithaca (NY)]: The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Accessed 1 Mar 2018 (2022).

- 36.Schall E, Roca I, Van Opzeeland I. Acoustic metrics to assess humpback whale song unit structure from the Atlantic sector of the Southern ocean. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2021;149:4649–4658. doi: 10.1121/10.0005315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dice LR. Measures of the amount of ecologic association between species. Ecology. 1945;26:297–302. doi: 10.2307/1932409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2018).

- 39.Suzuki, R., Terada, Y. & Shimodaira, H. pvclust: Hierarchical clustering with P-values via multiscale bootstrap resampling. R package version 2.2-0 (2019).

- 40.Kohonen T. Median strings. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 1985;3:309–313. doi: 10.1016/0167-8655(85)90061-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garland EC, et al. Improved versions of the Levenshtein distance method for comparing sequence information in animals' vocalisations: Tests using humpback whale song. Behaviour. 2012;149:1413–1441. doi: 10.1163/1568539x-00003032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van der Loo MP. The stringdist package for approximate string matching. R J. 2014;6:111–122. doi: 10.32614/RJ-2014-011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zerbini A, et al. Migration and summer destinations of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the western South Atlantic Ocean. J. Cetacean Res. Manage. Spec. Issue. 2011;3:113–118. doi: 10.3354/meps313295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenbaum HC, Maxwell SM, Kershaw F, Mate B. Long-range movement of Humpback Whales and their overlap with anthropogenic activity in the South Atlantic Ocean. Conserv. Biol. 2014;28:604–615. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reisinger RR, et al. Combining regional habitat selection models for large-scale prediction: Circumpolar habitat selection of Southern Ocean humpback whales. Remote Sens. 2021;13:2074. doi: 10.3390/rs13112074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garland EC, McGregor PK. Cultural transmission, evolution, and revolution in vocal displays: Insights from bird and whale song. Front. Psychol. 2020;11:2387. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.544929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Findlay KP, et al. Humpback whale "super-groups"—a novel low-latitude feeding behaviour of Southern Hemisphere humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the Benguela Upwelling System. PLoS One. 2017 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Owen K, et al. Effect of prey type on the fine-scale feeding behaviour of migrating east Australian humpback whales. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2015;541:231–244. doi: 10.3354/meps11551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Riekkola L, Andrews-Goff V, Friedlaender A, Zerbini AN, Constantine R. Longer migration not necessarily the costliest strategy for migrating humpback whales. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshwat. Ecosyst. 2020;30:937–948. doi: 10.1002/aqc.3295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Torres LG. A sense of scale: Foraging cetaceans' use of scale-dependent multimodal sensory systems. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2017;33:1170–1193. doi: 10.1111/mms.12426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Horton TW, et al. Straight as an arrow: Humpback whales swim constant course tracks during long-distance migration. Biol. Lett. 2001;7:674–679. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2011.0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Au WWL, et al. Acoustic properties of humpback whale songs. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2006;120:1103–1110. doi: 10.1121/1.2211547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dunlop RA, Cato DH, Noad MJ, Stokes DM. Source levels of social sounds in migrating humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2013;134:706–714. doi: 10.1121/1.4807828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cheeseman T, et al. Advanced image recognition: A fully automated, high-accuracy photo-identification matching system for humpback whales. Mamm. Biol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s42991-021-00180-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Felix F, et al. A new case of interoceanic movement of a humpback whale in the Southern Hemisphere: The El Nino Link. Aquat. Mamm. 2020;46:578–584. doi: 10.1578/AM.46.6.2020.578. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pomilla C, Rosenbaum HC. Against the current: An inter-oceanic whale migration event. Biol. Lett. 2005;1:476–479. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2005.0351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stevick PT, et al. A quarter of a world away: Female humpback whale moves 10,000 km between breeding areas. Biol. Lett. 2010;7:299–302. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2010.0717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nicol S. Krill, currents, and sea ice: Euphausia superba and its changing environment. Bioscience. 2006;56:111–120. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2006)056[0111:Kcasie]2.0.Co;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Atkinson A, Siegel V, Pakhomov E, Rothery P. Long-term decline in krill stock and increase in salps within the Southern Ocean. Nature. 2004;432:100–103. doi: 10.1038/nature02996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Atkinson A, et al. Krill (Euphausia superba) distribution contracts southward during rapid regional warming. Nat. Clim. Change. 2019;9:142–147. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0370-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Loeb VJ, Santora JA. Climate variability and spatiotemporal dynamics of five Southern Ocean krill species. Prog. Oceanogr. 2015;134:93–122. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2015.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marrari M, Daly KL, Hu C. Spatial and temporal variability of SeaWiFS chlorophyll a distributions west of the Antarctic Peninsula: Implications for krill production. Deep Sea Res. Part II. 2008;55:377–392. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2007.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sremba AL, Hancock-Hanser B, Branch TA, LeDuc RL, Baker CS. Circumpolar diversity and geographic differentiation of mtDNA in the critically endangered Antarctic Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus intermedia) PLoS One. 2012;7:e32579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bortolotto GA, Danilewicz D, Andriolo A, Secchi ER, Zerbini AN. Whale, whale, everywhere: Increasing abundance of Western South Atlantic Humpback Whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in their wintering grounds. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Félix F, Castro C, Laake JL. Abundance and survival estimates of the southeastern Pacific humpback whale stock from 1991–2006 photo-identification surveys in Ecuador. J. Cetacean Res. Manage. 2020 doi: 10.47536/jcrm.vi.303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ward E, Zerbini AN, Kinas PG, Engel MH, Andriolo A. Estimates of population growth rates of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the wintering grounds off the coast of Brazil (Breeding Stock A) J. Cetacean Res. Manage. 2020 doi: 10.47536/jcrm.vi3.323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Seyboth E, et al. Influence of krill (Euphausia superba) availability on humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) reproductive rate. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1111/mms.12805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cai W, et al. Increasing frequency of extreme El Niño events due to greenhouse warming. Nat. Clim. Change. 2014;4:111–116. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Santora JA, Reiss CS, Loeb VJ, Veit RR. Spatial association between hotspots of baleen whales and demographic patterns of Antarctic krill Eupahusia superba suggests size-dependent predation. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2010;405:255–269. doi: 10.3354/meps08513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Friedlaender AS, Lawson GL, Halpin PN. Evidence of resource partitioning between humpback and minke whales around the western Antarctic Peninsula. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2009;25:402–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2008.00263.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reid K, Brierley AS, Nevitt GA. An initial examination of relationships between the distribution of whales and antarctic krill Euphausia superba at South Georgia. J. Cetacean Res. Manage. 2000;2:143–149. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nicol S, et al. Southern Ocean iron fertilization by baleen whales and Antarctic krill. Fish Fish. 2010;11:203–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2010.00356.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Teschke, K., Pehlke, H., Deininger, M., Jerosch, K. & Brey, T. Scientific background document in support of the development of a CCAMLR MPA in the Weddell Sea (Antarctica)-Version 2016. (2016).

- 74.Teschke K, et al. Planning marine protected areas under the CCAMLR regime—the case of the Weddell Sea (Antarctica) Mar. Policy. 2021;124:104370. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104370. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Analyses reported in this article can be reproduced using the data provided by Schall (2021) at Data Dryad: https://datadryad.org/stash/share/Vfg14Wkti-rXiDZWqIAJX7cdHGxFqUiPUUOWIWx5h6E.