Abstract

A known consequence of portal hypertension is the development of varices, which are described as “ectopic” when located at unusual sites in the abdomen. Ectopic varices carry a mortality rate as high as 40% after initial hemorrhagic episode. We report a patient who presented with hematuria secondary to bladder varices as the presenting symptom for a new diagnosis of cirrhosis. Cross-sectional imaging, early recognition of this rare event, combined with multidisciplinary management was essential for this patient to have a successful outcome.

Keywords: Ectopic varices, Hematuria, Cirrhosis

Introduction

A known consequence of portal hypertension in cirrhotic patients is the development of varices. Portal hypertension leads to venous collateral circulation usually in or near the gastrointestinal tract; therefore, varices are most commonly found in the cardio-esophageal junction. Varices are described as “ectopic” when located at alternate sites, including small bowel, rectum, intestinal stoma, umbilicus, retroperitoneum, biliary tract, vagina, and bladder [1]. Ectopic varices are an uncommon cause of gastrointestinal hemorrhage accounting for up to 5% of variceal bleeding but carry a high mortality rate of up to 40% after an initial hemorrhagic episode [1, 2, 3, 4, 5].

Bladder varices are an even rarer entity because the bladder wall is an uncommon collateral venous route. As a result, bladder varices tend to occur after interruption to normal collaterals, as seen in patients who have undergone prior interventions that alter portal venous anatomy and pressure dynamics such as mesenteric surgery or prior obliteration of gastroesophageal varices [1, 2, 6, 7]. While there have been many treatment options proposed, there currently is no uniform treatment for this rare entity, with the only successful long-term treatment being surgical decompression and transplantation [6]. We report a case of hematuria secondary to bladder varices as the presenting symptom of a new diagnosis of cirrhosis and describe the treatment modality decided on for this patient scenario.

Case Report/Case Presentation

A 62-year-old Caucasian female presented to an outside hospital with 2 days of hematuria, clots, and dysuria. Her past medical history included Graves disease status post-thyroidectomy, bowel resection, rheumatoid arthritis, COPD, and chronic hepatitis C infection (HCV). She was recently diagnosed with genotype 2b chronic HCV and completed 8 weeks of glecaprevir-pibrentasvir. Serologic fibrosis testing had predicted F4 fibrosis; however, prior ultrasound imaging revealed only hepatomegaly without liver contour nodularity, and upper endoscopy 1 year prior to admission did not demonstrate evidence of portal hypertension.

At the outside hospital, urology was consulted for hematuria evaluation and the patient was placed on continuous bladder irrigation (CBI). CT of the abdomen and pelvis showed a micronodular appearance of the liver and irregular right bladder wall thickening with intravesicular hyperdense layering material compatible with retained blood clot. Additionally seen was dilatation of the right pelvic veins adjacent to the irregular bladder wall. No other varices were identified.

The patient continued to have hematuria while on CBI prompting cystoscopy which revealed the irregular wall thickening seen on CT was secondary to dilated vessels within the bladder wall. Despite temporary cessation of hematuria, bleeding recurred with a drop in hemoglobin requiring transfusion of packed red blood cells and initiation of an octreotide drip. Five days after initial presentation, the patient was transferred to our hospital for evaluation and possible intervention for bleeding bladder varices in the setting of a new radiographic diagnosis of cirrhosis and presumed portal hypertension.

On presentation to our hospital, physical exam was notable for an obese female in no distress and without clinical findings of acute or chronic liver disease. She had a hemoglobin of 7.6, platelets 146, INR 1.14, PTT 29, total bilirubin 0.5, creatinine 0.8, and sodium 142 corresponding to a MELD-Na of 7. HCV RNA was undetectable. Abdominal ultrasound with Doppler evaluation confirmed nodularity and increased echogenicity of the liver suggesting cirrhosis with portal hypertension and no evidence of portal vein thrombosis, and CT abdomen/pelvis again showed cirrhosis with presumed portal hypertension manifested by pelvic varices extending into the wall of the bladder (shown in Fig. 1, 2). To gain a better understanding of the patient's liver disease in the setting of treated hepatitis C, transvenous liver biopsy and pressure measurements were performed. An indirect portal vein pressure of 30 mm Hg and free hepatic vein pressure of 17 mm Hg were obtained, equaling a portosystemic pressure gradient of 13 mm Hg, confirming the presence of portal hypertension. Biopsy specimen pathology demonstrated chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis consistent with treated chronic hepatitis C, Batts-Ludwig grade 2/4 stage 4/4.

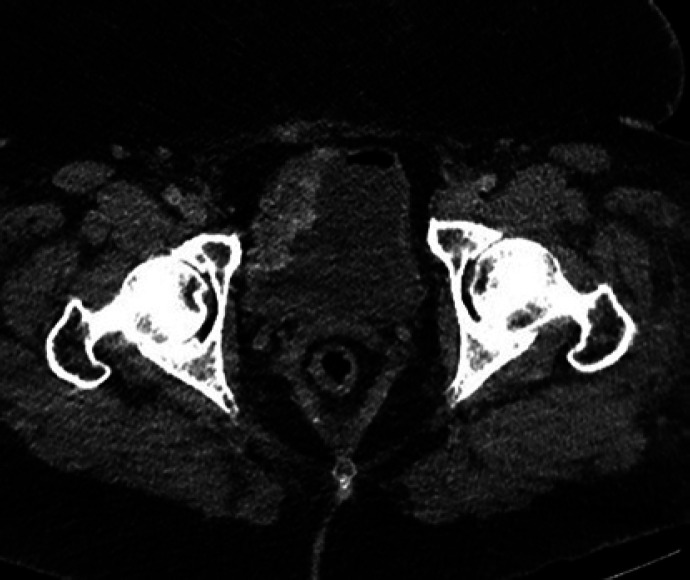

Fig. 1.

CT abdomen/pelvis showing pelvic varices extending into the wall of bladder.

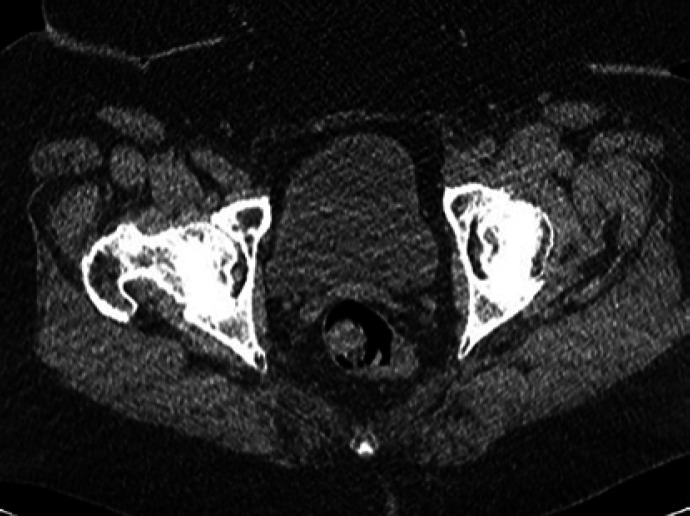

Fig. 2.

CT abdomen/pelvis showing pelvic varices extending into the wall of bladder.

Due to ongoing hematuria, the patient was restarted on CBI and repeat cystoscopy showed prominent right bladder wall varices believed to be the source of ongoing, clinically significant hematuria. Although continuous octreotide infusion at 50 μg/h improved the patient's hematuria, complete cessation was not achieved.

Following multidisciplinary discussion, transvenous variceal sclerotherapy was selected as the preferred treatment modality. Ultimately, percutaneous transhepatic access to the portal vein was obtained allowing successful coil-assisted antegrade transvenous obliteration utilizing a mixture of sodium tetradecyl sulfate (STS), ethiodized oil, and gelfoam slurry (Fig. 3). Two days post-procedure, the patient was spontaneously voiding clear urine with stable hemoglobin levels, allowing for safe discharge.

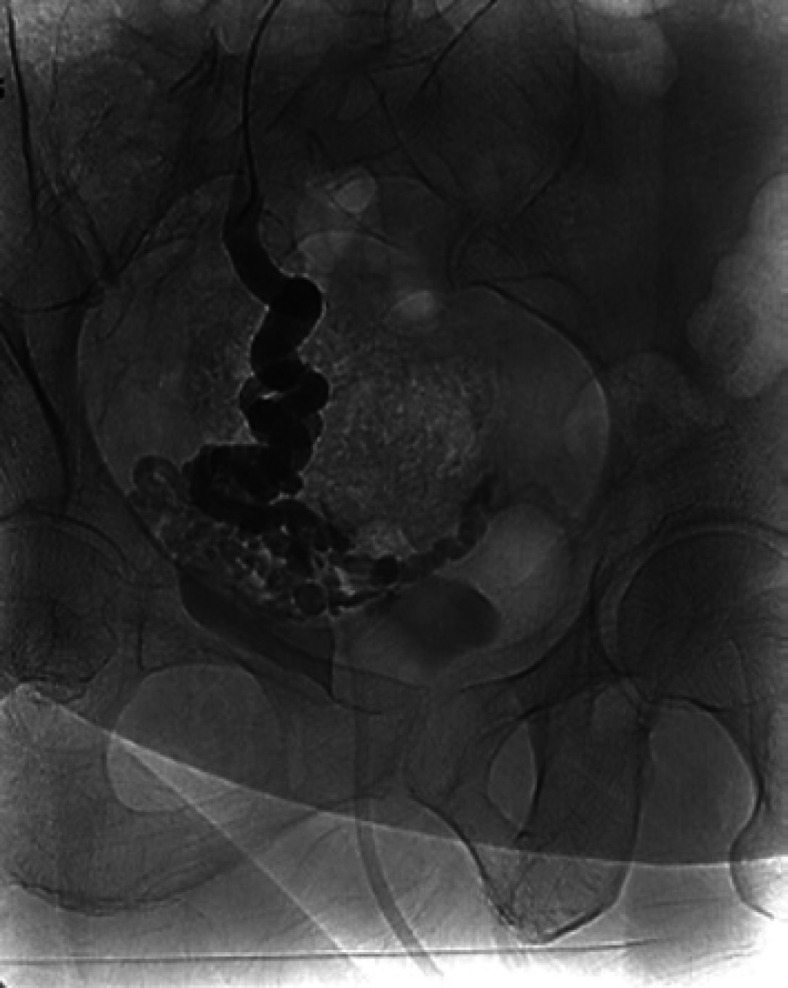

Fig. 3.

Successful coil-assisted transvenous obliteration of varix.

On follow-up, the patient reported intermittent bladder spasms felt to be related to irritation from the sclerosing agent, which spontaneously resolved over time. CT imaging performed 2 and 9 months post-procedure demonstrated stable coil position, sustained obliteration of the right pelvic and bladder varices, and no residual or recurrent enhancing varices (shown in Fig. 4, 5). An EGD performed 4 months post-procedure showed grade 1 esophageal varices with portal hypertensive gastropathy. To date, the patient has not required liver transplant nor transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) decompression.

Fig. 4.

CT abdomen/pelvis performed at 9 months post-treatment showing sustained obliteration of the right pelvis and bladder varices and no residual or recurrent enhancing varices.

Fig. 5.

CT abdomen/pelvis performed at 9 months post-treatment showing sustained obliteration of the right pelvis and bladder varices and no residual or recurrent enhancing varices.

Discussion/Conclusion

Ectopic varices are a rare condition that carry a high mortality rate. The formation of bladder varices is extremely variable, and treatment depends largely on several factors specific to each patient scenario. In our patient with a presenting symptom of hematuria and a new diagnosis of cirrhosis with portal hypertension, it was important to consider ectopic varices as a potential cause of this patient's clinically significant hematuria. Early diagnosis allowed time for multidisciplinary discussion in order to decide on the safest and most successful treatment outcome in our patient.

Ectopic varices are thought to occur in patients with portal hypertension when venous collateral circulation occurs in atypical locations, or when collateral circulation is interrupted by previous procedures that alter portal dynamics [8]. Examples of these include sclerotherapy or band ligation of existing varices. Furthermore, bladder varices are more likely to occur in patients who have undergone intra-abdominal surgeries that alter normal portal pressure anatomy and flow dynamics, as in our patient who had a prior history of bowel resection [1, 5, 9, 10]. In our case, a high index of suspicion, confirmation of cirrhosis and portal hypertension, cross-sectional imaging, and direct cystoscopic visualization were essential to making an accurate diagnosis of bleeding ectopic varices.

Medical management of bleeding ectopic varices is the same as for esophagogastric varices and includes blood transfusions if indicated and intravenous administration of somatostatin [8]. Patients can also be placed on beta blocker therapy for prevention. Standard interventional treatment; however, is not well defined in the literature due to the rare occurrence of ectopic varices [2, 4, 8]. Treatments described include surgical ligation or cauterization, sclerotherapy or embolization, TIPS creation, surgical portosystemic shunt creation, targeted electric coagulation, loop ligation, devascularization or bypass, and liver transplantation [1, 5, 6, 8, 11, 12]. Per standard medical management of varices, our patient was started on intravenous octreotide which improved the hematuria but did not stop it altogether; thus, more definitive intervention was necessary. The treatment decision was facilitated by multidisciplinary discussion involving hepatology, urology, and interventional radiology. Although TIPS creation is commonly used for portal hypertension decompression and long-term efficacy, in this case, definitive intervention with percutaneous coil-assisted sclerotherapy was the treatment determined to have the lowest associated morbidity and mortality and felt appropriate in this patient with only a solitary, clinically significant ectopic varix. The patient had no further bleeding episodes by time of follow-up.

We describe a patient whose presenting symptom of cirrhosis with portal hypertension was hematuria from bladder varices, felt to be occurring in the setting of a prior bowel resection causing altered anatomy. As described in our case, percutaneous interventions, although not frequently discussed in the literature, could be a more common consideration in today's practice. Early recognition and multidisciplinary management of this rare clinical entity is essential for successful treatment and good patient outcomes.

Statement of Ethics

Ethical approval is not required for this study in accordance with local or national guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

There is no financial disclosure to report.

Author Contributions

Cristina Angelo drafted the manuscript and is the article guarantor. Allison Tan, Dina Halegoua-De Marzio, and Jonathan M. Fenkel reviewed, revised, and approved the manuscript prior to submission.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Kim M, Al-Khalili R, Miller J. Vesical varices: an unusual presentation of portal hypertension. Clin Imaging. 2015;39((5)):920–2. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parmar K, Rathi S, Khanna A, Gupta M, Singh A, Singh SK, et al. Portal hypertensive vesiculopathy: a rare cause of hematuria and a unique management strategy. Urology. 2018;115:e7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2018.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.HelmyAl Kahtani K, Al Kahtani M, Al Fadda M. Updates in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of ectopic varices. Hepatol Int. 2008;2((3)):322–34. doi: 10.1007/s12072-008-9074-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norton ID, Andrews JC, Kamath PS. Management of ectopic varices. Hepatology. 1998;28((4)):1154–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akhter NM, Haskal ZJ. Diagnosis and management of ectopic varices. Gastrointest Interv. 2012;1((1)):3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herden U, Seiler CA, Candinas D, Schmid SW. Bladder tamponade due to vesical varices during orthotopic liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2008 Nov;21((11)):1105–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2008.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaspar Y, Detry O, de Leval J. Vesical varices in a patient with portal hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2001;345((20)):1503–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200111153452018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Li H, Wang D, Yang X. Bladder varices caused by portal hypertension. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2015;72((3)):795–8. doi: 10.1007/s12013-015-0535-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sato T, Akaike J, Toyota J, Karino Y, Ohmura T. Clinicopathological features and treatment of ectopic varices with portal hypertension. Int J Hepatol. 2011;2011:1. doi: 10.4061/2011/960720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma M, Rameshbabu CS. Collateral pathways in portal hypertension. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2012;2((4)):338–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kochar N, Tripathi D, McAvoy NC, Ireland H, Redhead DN, Hayes PC. Bleeding ectopic varices in cirrhosis: the role of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunts. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28((3)):294–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei J, Zhu X, Yu HT, Liang ZJ, Gou X, Chen Y. Severe hematuria due to vesical varices in a patient with portal hypertension: a case report. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9((18)):4810–6. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i18.4810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.