Abstract

Objectives

Homocysteine is an intermediary amino acid formed in methionine metabolism, with elevated total homocysteine (tHCY) being a biomarker of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. We evaluated the Abbott ARCHITECT tHCY immunoassay, compared it with the current established JEOL ion exchange chromatography (IEC) method and evaluated its clinical utility.

Design and methods

Following immunoassay method verification, plasma samples of 91 patients were analysed for tHCY using immunoassay and IEC.

Results

For the Abbott immunoassay, accuracy was assessed, with UK NEQAS EQA specimens, by the correlation of our Abbott immunoassay measurements to the Abbott ARCHITECT immunoassay mean (bias = 1.6%), and to the overall immunoassay mean (bias = 2.0%). The total imprecision was 2.7% (11.00 μmol/L), 2.4% (16.80 μmol/L) and 2.8% (24.30 μmol/L) respectively. Bias in linearity assessment was 0.12%–2.58%. The inter-method correlation was strong in Passing-Bablok regression: immunoassay = IEC x0.857 + 2.445 (95% CI: slope = [0.742,0.947], intercept = [1.340,3.582]), with Spearman correlation = 0.803 (p < 0.001). The Bland-Altman plot showed an average difference of −0.284 μmol/L (95% CI: [-1.043,0.474]) with limits of agreement (mean ± 1.96SD) from −7.425 μmol/L to 6.857 μmol/L.

No significant difference in tHCY was found using both methods in patients with cerebrovascular diseases and cardiovascular diseases. Most tHCY measurements were within the reference ranges of both methods. All homocystinuria patients had tHCY values above the reference ranges of both methods.

Conclusions

The immunoassay demonstrated robust performance in its verification and showed good comparability with the IEC but with some biases so caution is needed if both are used interchangeably. The immunoassay offers an automated alternative to IEC in the assessment of hyperhomocysteinaemia.

Keywords: Homocysteine, Immunoassay, ion exchange chromatography

Highlights

-

•

The total homocysteine immunoassay is verified to have robust performance.

-

•

The immunoassay correlates with the ion exchange chromatography but with biases.

-

•

Caution is needed if both methods are used interchangeably.

1. Background

Homocysteine (HCY) is occasionally requested as a prognostic risk factor in patients with cardiovascular diseases. Homocysteine is a sulfhydryl-containing amino acid, as an intermediate product of the biosynthesis of methionine and cysteine and is also a product of demethylation of dietary methionine [1]. Increased plasma HCY may cause direct endothelial cell injury by inducing oxidative stress and reducing available nitric oxide, while also resulting in stiffness of vessels and higher risk of thrombosis [1,2]. Hyperhomocysteinaemia has been implicated in the development of stroke, exerting neurotoxic effects on neuronal cells by acting as an agonist for glutamate receptors, metabotropic receptors and ionotropic receptors so that overstimulation of these receptors increases levels of cytoplasmic calcium, free radicals and caspases [2]. It can also cause damage to glial cells and disrupt the blood-brain barrier [2]. A recent systematic review with meta-analysis on prospective observational studies identified an elevated level of HCY in plasma as a risk factor for ischaemic and recurrent strokes, but not haemorrhagic stroke [3]. In contrast, another recent systematic review with meta-analysis on case-control studies, which has included completely different articles from the aforementioned systematic review, has displayed that HCY levels are higher in haemorrhagic stroke patients than those in healthy control and no significant difference in HCY levels exists between ischaemic and haemorrhagic strokes [4]. Furthermore, as an independent cardiovascular disease risk factor, homocysteine damages cardiovascular endothelium and smooth muscle cells with subclinical alterations in arterial structure and functions [1]. HCY levels have been found to be higher in patients with coronary artery disease than patients without and to be correlated with greater severity of coronary artery disease [5].

Several types of vitamin B, such as folic acid, B9 and B12, are involved in the metabolism of HCY. It is postulated that vitamin B treatment could lower HCY levels and hence reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases and stroke. However, there has been contrary between observational studies and interventional trials, where the former group is supportive of the benefits of HCY-lowering vitamin B treatment in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases and stroke but the latter group does not find any substantial benefits [6].

A number of assays are available for the analysis of total homocysteine (tHCY), including the automated Abbott ARCHITECT immunoassay and the JEOL ion exchange chromatography (IEC) method, while the “gold standard” method would be mass spectrometry which is not commonly used. Previous studies compared Abbott IMx immunoassay with JEOL IEC [7], and compared among Abbott IMx immunoassay, Bio-Rad enzyme immunoassay and high-performance liquid chromatography [8], and high correlations were reported by them. However, the Abbott IMx immunoassay uses the microparticle enzyme immunoassay (MEIA) technology that is different from the chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay used in the Abbott ARCHITECT analyser. Also, previous studies did not take into consideration the diagnoses of patients when used in the clinical setting.

In this study, our objectives were to evaluate the Abbott ARCHITECT immunoassay and compare it with the JEOL method and to investigate if the clinical utility of the biomarker was comparable with both methods in patients with cardiovascular disease and cerebrovascular disease.

2. Methodology

2.1. Patient selection

This study was undertaken in the Mater Misericordiae University Hospital (MMUH), Dublin, from May to October 2018. All samples received routinely during the time period were analysed in parallel for both methods, without any pre-selection. The decision to undertake homocysteine analysis was made by physicians who identified diagnostic and/or monitoring benefits from homocysteine analysis for their patients. Diagnoses were made by physicians who ordered the tHCY measurement and tHCY is not an essential component for the diagnosis of diseases except homocystinuria. The age, gender, clinical diagnosis, tHCY measurement, vitamin B12 level and hs-CRP level were recorded for all the study patients. Only the first tHCY measurement result was included in patients for whom tHCY measurements were ordered more than once. The diagnoses were categorised as follows; cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, metabolic and neurology diseases and those with no definitive diagnosis. Cerebrovascular diseases were further divided into ischaemic stroke, haemorrhagic stroke and transient ischaemic attack (TIA).

2.2. Plasma sampling

Upon request for tHCY measurement, blood was drawn from the patient into a lithium heparin tube and immediately placed on ice, centrifuged, aliquoted and stored at −20 °C. It is thawed prior to analysis with the immunoassay method in the MMUH. On the other hand, the aliquoted sample was sent to Children's University Hospital, Dublin, for simultaneous tHCY measurement using the IEC method. No sample underwent more than one freeze-thaw cycle. According to the manufacturers, the frozen samples were stable for homocysteine analysis for up to 1 year.

2.3. Instrumentation and materials

The immunoassay method. The Abbott ARCHITECT homocysteine assay (Abbott Park, Illinois, U.S.A. ARCHITECT i2000SR analyser) is a one-step immunoassay which utilises chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA). Bound or dimerised homocysteine (oxidised form) is reduced to free HCY, before being transformed into S-adenosyl HCY. The S-adenosyl HCY competes with its acridinium-labelled counterpart for a monoclonal antibody prior to chemiluminescence measurement. The manufacturer states the assay performance has satisfactory precision as the assay is designed to have a total coefficient of variation (CV) of ≤10% while the range of total CVs in the manufacturer's internal study were found to be 2.1%–6.3% [9]. The immunoassay was calibrated with six provided calibrator solutions (0.0, 2.5, 5.0, 10.0, 20.0 and 50.0 μmol/L).

The ion exchange chromatography method. The JEOL AminoTac JLC500/V analyser (Akishima, Tokyo, Japan) was used. The analyser measures HCY with photometric detection after a reaction with ninhydrin. It was calibrated with homocysteine (product no. H4628) and l-methionine (product no. M9625), manufactured by Sigma-Aldrich (Sigma-Aldrich Ireland Limited, Wicklow, Ireland). Quality control was performed with Special Assays in Serum kit manufactured by MCA Laboratory (Beatrixpark, Winterswijk, The Netherlands). According to JEOL, the analytical range is 3–400 μmol/L. The running CV is 8–10%.

2.4. Verification of the Abbott immunoassay method

The accuracy was verified using 9 external quality assessment (EQA) specimens provided by the United Kingdom National External Quality Assessment Service (UK NEQAS) (3 specimens in each of 3 recent distributions). Results of our measurements were compared to the UK NEQAS official Abbott ARCHITECT immunoassay method (trimmed mean), and the overall immunoassay mean (method laboratory trimmed mean, MLTM).

Assay imprecision (in terms of total, intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variance) was tested using quality control (QC) materials provided by the manufacturer (Abbott) and third-party QC materials obtained from Technopath (Technopath Clinical Diagnostics) Multichem IA Plus controls. The Technopath QC levels were 11.00 (Level 1), 16.80 (Level 2) and 24.30 μmol/L (Level 3) with each level tested 5 times per day for 5 consecutive days.

The auto-dilution was assessed as per the dilution protocol published by The Association for Clinical Biochemistry and Laboratory Medicine [10], with 3 samples of high tHCY concentrations (more than 50 μmol/L). Each sample was diluted both manually 1:10 (expected concentration) and automatically 1:10 (observed concentration) by the Abott ARCHITECT analyser. A difference of <15% was considered acceptable.

The linearity was assessed in accordance with the guideline provided by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [11]. Previous samples were used to make a “high tHCY pool” and “low tHCY pool, both of which were then used to create 6 equally spaced dilutions with the expected concentrations being calculated by the formula “expected concentration = (([high tHCY pool]*volume 1) + ([low tHCY pool]*volume 2))/(volume 1 + volume 2)”. The range of concentrations included dilutions with concentrations that required on-board auto-dilution. Each dilution was run in duplicate so that the mean observed tHCY concentration could be calculated. The linearity was assessed by a plot of mean observed concentration against mean expected concentration and by the percentage difference between the two values over the mean expected concentration.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (IBM, New York, the United States) (p-value < 0.05 considered significant). Accuracy was analysed with paired-sample t-test and the calculation of bias. The mean and standard deviation (SD) derived from imprecision studies was used to calculate the CV. The inter-method correlation was analysed with Passing-Bablok regression test together with Bland-Altman plot using MedCalc (Ostend, Belgium). Within each diagnosis group, the two methods were compared by Spearman correlation test to assess the non-parametric correlation.

For immunoassay, the reference ranges are 4.44–13.56 μmol/L and 5.46–16.20 μmol/L respectively in female and male individuals as per manufacturer, Abbott [9]. For IEC, the reference range adopted at Children's University Hospital is combined from several sources relating to different age groups. The IEC reference ranges in individuals of the age of 0–12 months, 1–10 years, 10–14 years, 14–15 years, 15–18 years, 18–65 years and above 65 years are 3–11 μmol/L, 3–8 μmol/L, 3–10 μmol/L, 5–10 μmol/L, 5–11 μmol/L, 5–16 μmol/L, and 5–20 μmol/L respectively. The reference range for 0–12 months was produced internally by Children's University Hospital; that of 65 years and above was adopted form Tietz Clinical Guide to Laboratory Tests (4th Edition) [12]; and the other reference ranges of other age groups were adopted from a brief article written by Vilaseca et al. (1997) [13].

3. Results

3.1. Accuracy

For the 9 EQA specimens from the UK NEQAS, the bias of our measurements against Abbott ARCHITECT immunoassay method (trimmed mean) and that against the overall immunoassay mean were respectively 1.6% and 2.0%.

3.2. Imprecision

For the three levels of Technopath samples, the total imprecision was 2.7% for Level 1 (mean: 11.22 μmol/L), 2.4% for Level 2 (mean: 16.90 μmol/L) and 2.8% for Level 3 (mean: 24.60 μmol/L) respectively. The intra- and inter-assay imprecision across the three levels was 2–2.3% and 1.4–2.2% respectively and were within both the imprecision targets (<10%) claimed by the manufacturer and desirable imprecision specifications (<4.15%) based on within-individual biological variation.

3.3. Auto-dilution

The mean expected (manual dilution) concentrations of the 3 samples used were 197.97 μmol/L, 76.90 μmol/L and 116.77 μmol/L while their mean observed (automatic dilution) concentrations and the percentage differences were respectively 206.84 μmol/L (4.48%), 79.51 μmol/L (3.39%) and 126.26 μmol/L (8.13%). All percentage differences were less than 15%.

3.4. Linearity

The mean expected concentrations of the low and high tHCY pools were 5.40 and 161.40 μmol/L respectively, and the mean expected concentrations of the 6 equally spaced dilutions would be 5.40, 36.60, 67.80, 99.00, 130.20, 161.40 μmol/L respectively. The mean observed concentrations and the percentage differences were 5.40 (N/A), 35.79 (2.21%), 68.27 (0.69%), 101.55 (2.58%), 130.36 (0.12%) and 161.40 (N/A) μmol/L respectively. The equation of the mean observed concentration against the mean expected concentration is y = 0.987 x + 2.544 with a correlation coefficient of 0.999.

3.5. Inter-method correlation

Ninety one patients, 49.5% male with mean age of 49.66 years (SD = 15.72) were included for method comparison (Table 1).

Table 1.

General characteristics of patients.

| Characteristics of patients | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 45 (49.5%) |

| Female | 46 (50.5%) |

| Age | |

| Mean (SD) | 49.66 (15.72) |

| <18 years | 1 (1.1%) |

| 18–65 years | 76 (83.5%) |

| >65 years | 14 (15.4%) |

| Total homocysteine measured by immunoassay (μmol/L) | |

| Median (interquartile range) | 11.21 (9.12–13.74) |

| Total homocysteine measured by ion exchange chromatography (μmol/L) | |

| Median (interquartile range) | 11.00 (8.00–14.00) |

| Diagnosis group of patients | |

| Cerebrovascular | 41 (45.1%) |

| Ischaemic stroke | 36 (39.6%) |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 1 (1.1%) |

| Transient ischaemic attack | 4 (4.4%) |

| Neurologya | 29 (31.9%) |

| Cardiovascular | 8 (8.8%) |

| Metabolic | 5 (5.5%) |

| Psychiatry | 1 (1.1%) |

| No definitive diagnosis | 7 (7.7%) |

Except cerebrovascular diseases.

The Passing-Bablok regression (Fig. 1(A)) showed a correlation between the two methods, giving an equation of tHCY immunoassay = tHCY IEC x 0.857 + 2.445 (95% CI of slope: [0.742, 0.947]; 95% CI of intercept: [1.340, 3.582]). The CUSUM test for linearity showing no significant deviation from linearity (p = 0.63 so the null hypothesis which affirms a linear relationship is not rejected). The Spearman's coefficient of rank correlation is 0.803 (p < 0.001), which could be conventionally classified as a strong correlation.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1(A): Passing-Bablok regression analysis on the correlation of the Abbott ARCHITECT immunoassay method to the JEOL IEC method for tHCY measurement on 91 samples. Fig. 1(B): Bland-Altman plot analysis of tHCY measurement by the immunoassay methods and IEC methods. The y-axis represents the difference between them while the x-axis represents their average values. tHCY: total homocysteine.

The Bland-Altman plot (Fig. 1(B)) (tHCY IEC – tHCY immunoassay) showed an average difference of −0.284 μmol/L (95% CI: [−1.043, 0.474]) with limits of agreement (mean ± 1.96SD) from −7.425 μmol/L (95%CI: 8.7267 to −6.1237) to 6.857 μmol/L (95%CI 5.556 to 8.158), (p = 0.459). The average percentage difference was −5.0% with limits of agreement being −52.7% and 42.7%.

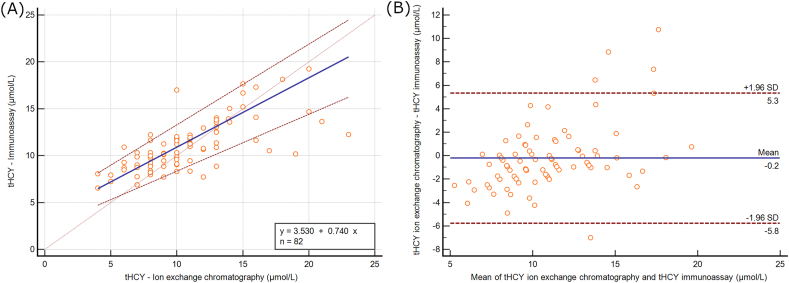

Most measurements concentrated in the range of tHCY <20 μmol/L measured by the immunoassay method (n = 82). In this region, the Passing-Bablok regression showed worse results (tHCY immunoassay = tHCY IEC x 0.740 + 3.530) with a flatter slope and a larger intercept (Fig. 2(A)). The Bland-Altman analysis showed better results, with a smaller average arithmetic difference of −0.225 μmol/L with more narrow limits of agreement from −5.7804 μmol/L to 5.3304 μmol/L (Fig. 2(B)).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2(A): Passing-Bablok regression analysis on the correlation of the Abbott ARCHITECT immunoassay method to the JEOL IEC method for tHCY for immunoassay tHCY <20 μmol/L. Fig. 2(B): Bland-Altman plot analysis of tHCY measurement by the immunoassay methods and IEC methods for immunoassay tHCY <20 μmol/L. The y-axis represents the difference between them while the x-axis represents their average values. tHCY: total homocysteine].

3.6. Clinical utility

Within each diagnosis group, the two methods show no statistically significant difference (Wilcoxon signed rank test) (Table 2), except in the haemorrhagic stroke group and the psychiatry group where there were not enough patients for such a comparison. Fig. 3(A) shows the box-and-whisker plot of all patients, except the psychiatry group, while Fig. 3(B) shows the lower part of Fig. 3(A) with measurements with values < 50 μmol/L.

Table 2.

Range of total homocysteine in different diagnosis groups and the correlation between methods.

| Diagnosis group | N | Total homocysteine (μmol/L) Median (interquartile range) |

Wilcoxon signed rank test p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunoassay | Ion exchange chromatography | |||

| Cerebrovascular | 41 | 10.87 (9.74–12.53) | 10.00 (9.00–14.00) | 0.131 |

| Ischaemic stroke | 36 | 10.78 (9.67–11.89) | 10.50 (9.00–13.00) | 0.215 |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Transient ischaemic attack | 4 | 14.51 (10.91–17.87) | 13.50 (10.00–17.75) | 0.465 |

| Neurologya | 29 | 11.72 (8.89–14.39) | 12.00 (8.00–15.00) | 0.309 |

| Cardiovascular | 8 | 10.87 (8.76–13.76) | 10.50 (7.25–12.75) | 0.069 |

| Metabolic | 5 | 12.49 (9.60–56.39) | 13.00 (8.00–59.50) | 0.686 |

| Psychiatry | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| No definite diagnosis | 7 | 10.91 (9.44–12.20) | 11.00 (8.00–11.00) | 0.31 |

Except cerebrovascular diseases.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3(A): Box-and-whisker plot of total homocysteine categorised by diagnosis group. Fig. 3(B): Close-up view of Fig. 3(A) with measurements of values of <50 μmol/L. The box represents the median, first and third percentiles. The whisker shows the maximum and minimum values within the range of 1.5x interquartile range from the median. Beyond the whiskers, circles represent outliers which are of values between 1.5x and 3x interquartile range from the median. Asterisks represent extremes which are beyond 3x interquartile range from the median.

The median value of vitamin B12 was 365 ng/L (n = 63) (interquartile range: 296–514 ng/L) while the median of hs-CRP measurement is 1.94 mg/L (n = 65) (interquartile range: 0.775–6.905 mg/L). Controlling for vitamin B12 and hs-CRP values, the homocysteine measurements of both methods correlate well (Spearman partial correlation = 0.760, p < 0.05). All patients with low vitamin B12 (n = 4) (<211 ng/L) had tHCY values above the reference range of immunoassay. All patients diagnosed with homocystinuria (n = 2) had normal vitamin B12 values.

Taking reference ranges into consideration, 66 (72.5%) patients were within the reference ranges of both methods, while 12 patients (13.2%) patients were above in both methods, including the 2 patients diagnosed with homocystinuria (Table 3). Others with tHCY values above reference ranges of both methods were diagnosed with ischaemic stroke, TIA, peripheral neuropathy (secondary to vitamin B12 deficiency), unspecific hemiplegia, tricuspid atresia, major depressive disorder and borderline personality disorder. However, 7 patients (7.7%) were within the reference range of the IEC but above the reference range of the immunoassay, and these patients were diagnosed with cerebrovascular diseases and neurology diseases. In these 7 patients, 5 of them had tHCY values measured by the immunoassay (range: 13.93–17.65 μmol/L) greater than that measured by the IEC. From the Passing-Bablok regression, the equation showed a tendency of the immunoassay measurement to be greater than the IEC measurement in measurements below 17 μmol/L, and this tendency could also be seen when reference ranges of both methods were considered.

Table 3.

Concordance between the reference ranges of the two methods.

| All patients (n = 91) | Ion exchange chromatography |

Cohen's kappa | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tHCY < lower limit | tHCY within reference range | tHCY > upper limit | ||||

| Immunoassay | tHCY < lower limit | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.565 | <0.001 |

| tHCY within reference range | 2 | 66 | 4 | |||

| tHCY > upper limit | 0 | 7 | 12 | |||

tHCY: total homocysteine.

4. Discussion

We verified an automated immunoassay (Abbott ARCHITECT) and compared it with the JEOL AminoTac JLC500/V analyser with acceptable clinical correlation in our cohort of patients with cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, metabolic, neurological and other diseases. Biases could be found between the methods. As none of these methods was gold standard, both methods are suitable methods for tHCY measurement but caution is needed if both are used interchangeably.

All homocystinuria patients included in this study had tHCY values far above the reference ranges of both methods. Since tHCY measurement is used for the monitoring of homocystinuria patients, the verification of the Abbott immunoassay has deemed it acceptable for such clinical purposes. The treatment for homocystinuria aims to lower the plasma tHCY concentration to a safe level, which is < 50 μmol/L for pyridoxine-responsive patients and <120 μmol/L for pyridoxine-unresponsive patients.

However, the usefulness of tHCY measurement for cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases may be arguable, since most patients excluding those with homocystinuria in our study had tHCY values within the reference range. Without a control, our study could not generate any conclusion on the sensitivity and specificity of tHCY for diagnosis or risk stratification.

On one hand, the reference-range tHCY values might not accurately represent a desirable healthy status of low cardiovascular and cerebrovascular risks. The pathological consequence associated with higher tHCY within the reference range may only be evident in longer time periods. A prospective cohort study [14] and a prospective case-control study [15] on populations without stroke at baseline, with follow-up periods of 5 years and 10 years retropectively, have shown increased risks of stroke in the upper portion of the reference range compared to the lower portion, with a number of covariates adjusted for, such as age, sex, hypertension and alcohol consumption.

If on the other hand, the reference range does accurately reflect healthy individuals, the finding of normal tHCY levels for our patients may be because of the early acute-phase body reaction after the onset of stroke that may act against the trend of increasing tHCY levels. A study has found that tHCY values at admission of stroke patients were significantly lower than the control group, which was unusual among studies; and then the tHCY values increased in the following week before remaining at the increased levels for the next 3 months [16]. Similar trends of an insignificant or small increase in tHCY in the early acute-phase soon followed by a bigger increase to consistently elevated values was was also found in other studies [17,18].

Furthermore, the use of reference ranges for evaluating tHCY levels may be limited due to the biological variations of tHCY. The within-person and between-person biological variations for tHCY have been found in previous studies to be 7.0–9.4% and 23.9–33.5% [[19], [20], [21], [22]]. Accordingly, the indexes of individuality (II) would be 0.21–0.39 and below the II threshold (<0.6) whereby a reference range for a given analyte maybe less useful for monitoring changes with significant changes for an individual occurring even if all results are within the reference range [23].

There were a limited number of patients in each specific disease cohort included in our studies, which did not allow us to draw conclusions as to the value of measuring HCY in each clinical scenario. The study demonstrates the value of the use of the automated tHCY assay in patients with potential disorders of homocysteine metabolism. Furthermore, plasma tHCY measurement is now recommended as the first-line diagnostic test for homocystinuria instead of free plasma HCY [24]. The measurement of free plasma HCY, despite being the active substance, is problematic as free plasma HCY is only detectable when tHCY has reached approximately more than 50 μmol/L and the method is manual and labour-intensive.

5. Conclusion

The Abbott ARCHITECT immunoassay was verified and demonstrated robust performance characteristics consistent with its use in the assessment of tHCY. It showed acceptable correlation with the JOEL ion exchange chromatography but with biases. As none of these methods was gold standard, both methods are suitable methods but caution is needed if both are used interchangeably. Hyperhomocysteinaemia as an underlying aetiology in CVD is uncommon, but should be ruled out as it is a treatable cause. Our studies suggest that a tHCY measurement using the automated immunoassay is a valid assessment tool in patients with stroke and TIA. We propose that this assay could serve as a method of monitoring tHCY in patients with homocysteine-related metabolic disease.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Mater University Hospital Institutional Research Board (IRB) Ref 1/378/1947.

Funding

This research was supported by ClinBioDx.

Contributorship

K-FKS, GRL, MF and KH processed the samples with immunoassay. IB and CT processed the samples with ion exchange chromatography. K-FKS collected patients’ data. K-FKS, GRL, MF and MCF analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved its final version. MCF supervised the project.

Guarantor

MCF.

Declaration of competing interest

No conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

N/A.

References

- 1.Ganguly P., Alam S.F. Role of homocysteine in the development of cardiovascular disease. Nutr. J. 2015;14:6. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-14-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lehotsky J., Tothova B., Kovalska M., Dobrota D., Benova A., Kalenska D., Kaplan P. Role of homocysteine in the ischemic stroke and development of ischemic tolerance. Front. Neurosci. 2016;10:538. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He Y., Li Y., Chen Y., Feng L., Nie Z. Homocysteine level and risk of different stroke types: a meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Nutr. Metabol. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014;24(11):1158–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou Z., Liang Y., Qu H., Zhao M., Guo F., Zhao C., Teng W. Plasma homocysteine concentrations and risk of intracerebral hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018;8(1):2568. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21019-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shenoy V., Mehendale V., Prabhu K., Shetty R., Rao P. Correlation of serum homocysteine levels with the severity of coronary artery disease. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2014;29(3):339–344. doi: 10.1007/s12291-013-0373-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Debreceni B., Debreceni L. The role of homocysteine-lowering B-vitamins in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2014;32(3):130–138. doi: 10.1111/1755-5922.12064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pernet P., Cuzon G., Lim S.K., Labau N., Laghzal A., Vaubourdolle M. Plasma homocysteine measurement with ion exchange chromatography (Jeol Aminotac 500): a comparison with the Abbott IMx assay. Med. Princ. Pract. 2006;15(2):149–152. doi: 10.1159/000090921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnelly J.G., Pronovost C. Evaluation of the Abbott IMx fluorescence polarization immunoassay and the bio-rad enzyme immunoassay for homocysteine: comparison with high-performance liquid chromatography. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2000;37(Pt 2):194–198. doi: 10.1258/0004563001898998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abbott, Abbott Architect System - Homocysteine 2008. http://www.ilexmedical.com/files/PDF/Homocysteine_ARC.pdf

- 10.Khatami Z., Hill R., Sturgeon C., Kearney E., Breadon P., Kallner A. Association for Clinical Biochemistry and Laboratory Medicine (ACB); London: 2005. Measurement Verification in the Clinical Laboratory: A Guide to Assessing Analytical Performance during the Acceptance Testing of Methods (Quantitative Examination Procedures) And/or Analysers. [Google Scholar]

- 11.CLSI . Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI); Pennsylvania: 2003. Evaluation of the Linearity of Quantitative Measurement Procedures: A Statistical Approach; Approved Guideline. CLSI Document EP06‐A. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu A. fourth ed. Saunders; Philadelphia: 2006. Tietz Clinical Guide to Laboratory Tests. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vilaseca M.A., Moyano D., Ferrer I., Artuch R. Total homocysteine in pediatric patients. Clin. Chem. 1997;43(4):690–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sacco R.L., Anand K., Lee H.S., Boden-Albala B., Stabler S., Allen R., Paik M.C. Homocysteine and the risk of ischemic stroke in a triethnic cohort: the NOrthern MAnhattan Study. Stroke. 2004;35(10):2263–2269. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000142374.33919.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iso H., Moriyama Y., Sato S., Kitamura A., Tanigawa T., Yamagishi K., Imano H., Ohira T., Okamura T., Naito Y., Shimamoto T. Serum total homocysteine concentrations and risk of stroke and its subtypes in Japanese. Circulation. 2004;109(22):2766–2772. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131942.77635.2D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haapaniemi E., Helenius J., Soinne L., Syrjala M., Kaste M., Tatlisumak T. Serial measurements of plasma homocysteine levels in early and late phases of ischemic stroke. Eur. J. Neurol. 2007;14(1):12–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howard V.J., Sides E.G., Newman G.C., Cohen S.N., Howard G., Malinow M.R., Toole J.F. Changes in Plasma Homocyst(e)ine in the Acute Phase After Stroke. Stroke. 2002;33(2):473–478. doi: 10.1161/hs0202.103069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meiklejohn D.J., Vickers M.A., Dijkhuisen R., Greaves M. Plasma homocysteine concentrations in the acute and convalescent periods of atherothrombotic stroke. Stroke. 2001;32(1):57–62. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garg U.C., Zheng Z.-J., Folsom A.R., Moyer Y.S., Tsai M.Y., McGovern P., Eckfeldt J.H. Short-term and long-term variability of plasma homocysteine measurement. Clin. Chem. 1997;43(1):141–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cobbaert C., Arentsen J.C., Mulder P., Hoogerbrugge N., Lindemans J. Significance of various parameters derived from biological variability of lipoprotein(a), homocysteine, cysteine, and total antioxidant status. Clin. Chem. 1997;43(10):1958–1964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clarke R., Woodhouse P., Ulvik A., Frost C., Sherliker P., Refsum H., Ueland P.M., Khaw K.-T. Variability and determinants of total homocysteine concentrations in plasma in an elderly population. Clin. Chem. 1998;44(1):102–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rossi E., Beilby J.P., McQuillan B.M., Hung J. Biological variability and reference intervals for total plasma homocysteine. Ann. Clin. Biochem.: Int. J. Biochem. Lab. Med. 1999;36(1):56–61. doi: 10.1177/000456329903600107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris E. Statistical aspects of reference values in clinical pathology. Prog. Clin. Pathol. 1981;8:45–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morris A.A., Kozich V., Santra S., Andria G., Ben-Omran T.I., Chakrapani A.B., Crushell E., Henderson M.J., Hochuli M., Huemer M., Janssen M.C., Maillot F., Mayne P.D., McNulty J., Morrison T.M., Ogier H., O'Sullivan S., Pavlikova M., de Almeida I.T., Terry A., Yap S., Blom H.J., Chapman K.A. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2017;40(1):49–74. doi: 10.1007/s10545-016-9979-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]