Short abstract

Using Joinpoint regression, our study revealed substantial decreases in postoperative opioid dispensing after outpatient pediatric surgeries beginning in 2017.

Abstract

BACKGROUND

Children who undergo common outpatient surgeries are routinely prescribed opioids, although available evidence suggests opioids should be used with discretion for procedures associated with mild to moderate pain. The study assessed trends in postoperative opioid prescribing over time to determine if prescribing declined.

METHODS

We used a private insurance database to study opioid-naïve patients under the age of 18 who underwent 1 of 8 surgical procedures from 2014 to 2019. The primary outcome was the likelihood of filling a prescription for opioids within 7 days of surgery, and the secondary outcome was the total amount of opioid dispensed. We used Joinpoint regression analysis to identify temporal shifts in trends.

RESULTS

The study cohort included 124 249 opioid-naïve children. The percentage of children who filled an opioid prescription decreased from 78.2% (95% confidence interval [CI] 76.3–80.1) to 48.0% (95% CI 45.8–50.1) among adolescents, from 53.9% (95% CI 51.6–56.2) to 25.5% (95% CI 23.5–27.5) among school-aged children and 30.4% (95% CI 28.6–32.2) to 11.5% (95% CI 10.1–12.9) among preschool-aged children. The average morphine milligram equivalent dispensed declined from 228.9 (95% CI 220.1–237.7) to 110.8 (95% CI 105.6–115.9) among adolescents, 121.3 (95% CI 116.7–125.9) to 65.9 (95% CI 61.1–70.7) among school-aged children and 75.3 (95% CI 70.2–80.3) to 33.2 (95% CI 30.1–36.3) among preschool-aged children. Using Joinpoint regression, we identified rapid opioid deadoption beginning in late 2017, first in adolescents, then followed by school- and preschool-aged children.

CONCLUSION

Opioid prescribing after surgery decreased gradually from 2014 to 2017, with a more pronounced decrease seen beginning in late 2017.

What’s Known on This Subject

Children who undergo common outpatient surgeries are routinely prescribed opioids, although available evidence suggests opioids should be used with discretion for procedures associated with mild to moderate pain.

What This Study Adds

Between 2014 and 2019, study results identified a substantial decrease in both the percentage of children filling an opioid prescription and the opioid quantity dispensed beginning in 2017. The onset of this decline differed by age group and surgery.

Opioids are routinely prescribed for common pediatric surgeries associated with mild to moderate pain; however, evidence suggests that recovery is similar with either limited or no opioids.1–8 In children, excessive postoperative opioid exposure has been associated with adverse outcomes, such as respiratory depression and new long-term use.6,9–12

Few data currently exist to characterize opioid prescribing trends for pediatric surgery, and it is unknown to what extent providers have moved away from routine opioid prescribing.2–4,6,7,12,13 Understanding patterns of opioid prescribing for children after surgery may facilitate policy efforts to address overuse moving forward. For example, opioid prescribing guidelines specific to pediatric surgical patients have recently been published and recommend limiting or avoiding opioid prescriptions for surgeries in which pain is anticipated to be minimal.3,4 These guidelines highlight the risks of opioid prescribing that are unique to pediatric patients.3 However, effective implementation of these evidence-based recommendations is limited by a lack of information on current opioid prescribing patterns and changes in prescribing over time for children undergoing surgery. The current study adds to the information available to policy makers and health systems to develop and target interventions intended to promote evidence-based prescribing.

To address this need, we designed this study to characterize trends in US prescribing practices for opioid-naïve children after surgery, including the percentage of children filling a prescription, the prescription quantity, and refills dispensed. We selected 8 common pediatric surgeries considered to have a low likelihood of significant pain requiring opioids. Because adolescents, school-aged children, and preschool-aged children undergo different types of surgeries, we studied national trends among these 3 groups.12,14 We examined if there was a change in study outcomes over time and then used Joinpoint regression to characterize changes in a slope of identified trends over time. We hypothesized that there would be a decrease in both the likelihood of filling an opioid prescription and prescription quantity consistent with the deadoption of routine opioid prescribing for children undergoing surgery during the study period.

Methods

Study Design and Oversight

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using a national insurance database to determine baseline opioid dispensing trends and moments when trends changed between April 1, 2014 and March 31, 2019. Among children that received at least 1 opioid prescription within 7 days of surgery, we assessed the average amount of opioid dispensed in morphine milligram equivalents (MME), the days supplied, and the percentage of children that received > 1 prescription (refill) within 30 days of surgery. We performed a visual comparison of trends and used Joinpoint regression analysis to identify points in time when rapid shifts in prescribing trends occurred. The purpose of this descriptive analysis was to characterize specific time points at which prescribing trends changed. As a result, we did not specify time points a priori at which we hypothesized a trend change would occur and, rather, allowed the Joinpoint regression program to identify significant points at which changes in trend were observed in the data.15 We used patient-level time series segmented regression to validate changes in prescribing likelihood identified by Joinpoint regression and control for potential confounders. This study was determined to be exempt from human subject research review by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Data Source

We used deidentified data from Optum’s Clinformatics Data Mart database, a US health insurance database with > 15 million annual enrollees from all 50 states.16 The database contained both medical and pharmacy claims data.17 The study sample included all patients under the age of 18 with a submitted claim for surgery and continuous enrollment for 90 days before the date of surgery during the study period. Demographic variables, such as race and ethnicity, were provided as recorded in the electronic medical record. Eight common pediatric surgeries were selected because severe postoperative pain requiring opioids was anticipated to be uncommon3,4,6,18,19 These procedures were: tonsillectomy (with or without adenoidectomy), adenoidectomy only, laparoscopic appendectomy, cholecystectomy, dental surgery, knee arthroscopy, circumcision, and orchiopexy. Procedures were identified by using current procedure terminology (CPT) codes in physician claims (Supplemental Table 3). For patients with > 1 eligible surgery during the study period, we used the first procedure. Patients with claims for > 1 eligible procedure on the same day, patients who required an inpatient stay, and those who did not have 90 days of continuous enrollment before the procedure and 30 days after were excluded. We also excluded patients with a filled opioid prescription in the 90 days before surgery to capture new opioid prescriptions for opioid-naïve children, rather than refills for established chronic pain treatment.

Because of differences in development and anticipated procedure distribution by age, we analyzed data separately in 3 age groups: adolescents (11 through 17 years), school-aged children (5 through 10 years), and infants to preschool-aged children (<5 years). Within a given age group, we limited our analyses to those procedures in which we had an average of at least 100 observations per 12 months over the study period. Among adolescents, we studied knee arthroscopy, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, appendectomy, tonsillectomy, adenoidectomy only, dental surgery, orchiopexy, and circumcision. Among school-aged children, we studied laparoscopic appendectomy, tonsillectomy, adenoidectomy only, dental surgery, orchiopexy, and circumcision. Among preschool-aged children, we studied tonsillectomy, adenoidectomy only, dental surgery, orchiopexy, and circumcision.

We defined baseline comorbidities in the 90 days before surgery using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) and Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes (Supplemental Table 4) for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), history of substance abuse, history of overdose, depression, and chronic conditions categorized into 10 systems using the Pediatric Complex Chronic Conditions classification, Version 2.20

Outcome Measures

Our primary outcome was the likelihood of filling an opioid prescription within 7 days of surgery. We included both liquid and tablet formulations, if applicable, of the following medications: codeine, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, morphine, oxycodone, and tramadol. The secondary outcome was the total amount of opioid dispensed in the first prescription, measured in MME, which we calculated using standard tables.21 We also examined the average days supplied in the initial prescription and the percentage of patients who received >1 opioid prescription (refill) in the first 30 days after surgery.

Statistical Analysis

We compared the distribution of procedures and patient characteristics over the study period and used descriptive statistics and simple hypothesis tests to characterize outcome distribution. By age group and surgery, we plotted the percentage of patients who filled a prescription, the average MME dispensed, days supplied, and the percentage who filled >1 prescription to visually examine changes in prescribing outcomes.

We performed a Joinpoint regression analysis for prescription likelihood and MME dispensed to characterize changes over time in outcome trends. Joinpoint regression is a method to describe changes in trends over time and to assess if a significant increase or decrease in rate occurred at a discrete moment in time.22,23 The logistic–linear regression Joinpoint model evaluates a null hypothesis of no change in trend versus a preset maximum number of changes and displays the quarterly change that is specific to the trend after versus before a given moment in time in which a change in trend is evaluated (ie, the “Joinpoint”).23 For scenarios in which our initial model rejected the null hypothesis of no change (ie, a change is identified), we assessed if the data were best described with 1 or 2 Joinpoints.23

We subsequently performed a linear time series segmented regression analysis for each age group that examined the likelihood of receiving a prescription and included covariates for Joinpoint pre–post time intervals, the interaction between intervals and quarter, sex, surgery type, and OSA diagnosis to verify that differences in trends before versus after identified Joinpoints persisted after controlling for potential confounders. A 3-month calendar quarter was selected as the unit of time for these models. Analyses were conducted in SAS (Version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and the Joinpoint Trend Analysis Software (Version 4.8.0.1, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD). All tests were 2-sided and significance was set at the 5% level.

Results

Overview

The study cohort included 124 249 patients; 45.0% were female and the median age was 7.0 years (interquartile ratio 4.0–14.0 years) (Table 1). There were 43 487 adolescents (35.1% of the sample), 40 221 (32.5%) school-aged children and 40 541 (32.7%) children under the age of 5. Overall, the most common comorbidities were OSA (n = 18 891; 15.2%, P < .001), history of congenital defect (n = 2103; 1.7%, P < .001), and history of cardiovascular diagnosis (n = 1615; 1.3%, P < .001). In addition, 66.4% (n = 82 445) of children were White, 9.6% (n = 11 989) identified as Hispanic or Latino, 5.7% (n = 7190) were Black or African American, and 3.0% (n = 3681) were Asian.

TABLE 1.

Surgical Patient and Procedure Characteristics by Age Group

| Variable/Age group | Infant to Preschool-Aged, 0–4 y, n = 40 541 (32.6%) | School-Aged Children, 5–10 y, n = 40 221 (32.4%) | Adolescents, 11–17 y,n = 43 487 (35.0%) | Overall, n = 124 249 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age, median (IQR) | 3.0 (1.0–4.0) | 7.0 (5.0–8.0) | 15.0 (13.0–16.0) | 7.0 (4.0–14.0) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 15 345 (38.0) | 18 191 (45.5) | 22 124 (50.9) | 55 880 (45.0) |

| Surgical procedures, n (%) | ||||

| Adenoidectomy | 13 515 (33.5) | 6048 (15.1) | 1604 (3.7) | 21 167 (17.1) |

| Appendectomya | — | 2285 (5.7) | 6143 (14.1) | 8565 (6.9) |

| Arthroscopic knee surgery | — | — | 11 816 (27.2) | 12 093 (9.7) |

| Cholecystectomy | — | — | 1165 (2.7) | 1239 (1.0) |

| Circumcision | 5747 (14.2) | 1450 (3.6) | 1249 (2.9) | 8446 (6.8) |

| Dental surgery | 6200 (15.4) | 5747 (14.4) | 10 320 (23.7) | 22 267 (17.9) |

| Orchiopexy | 1388 (3.4) | 1319 (3.3) | 1367 (3.1) | 4074 (3.3) |

| Tonsillectomy +/− adenoidectomy | 13 540 (33.5) | 23 098 (57.8) | 9823 (22.6) | 46 461 (37.4) |

| Common comorbidities,b n (%) | ||||

| OSA history | 7575 (18.8) | 8974 (22.5) | 2339 (5.4) | 18 891 (15.2) |

| Congenital defect diagnosis | 794 (2.0) | 590 (1.5) | 709 (1.6) | 2103 (1.7) |

| Cardiovascular diagnosis | 626 (1.5) | 492 (1.2) | 490 (1.1) | 1615 (1.3) |

| Neurologic/neuromuscular diagnosis | 428 (1.1) | 449 (1.1) | 385 (0.9) | 1262 (1.0) |

| Race or ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 24 950 (61.8) | 26 872 (67.3) | 30 348 (69.8) | 82 445 (66.4) |

| Black or African American | 2412 (6.0) | 2182 (5.5) | 2493 (5.7) | 7190 (5.7) |

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 1244 (3.1) | 1267 (3.2) | 1162 (2.7) | 3681 (3.0) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 3487 (8.6) | 4227 (10.6) | 4219 (9.7) | 11 989 (9.6) |

| Other/unknown | 8297 (20.5) | 5399 (13.5) | 5265 (12.1) | 19 025 (15.3) |

IQR, interquartile range; —, not applicable.

Procedures with <100 occurrences across 12 calendar months were not included in age brackets.

Comorbidities with 1% prevalence were not included.

Among all children, the 3 most commonly performed surgeries were tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy (n = 46 461; 37.4%, P < .001), dental surgery (n = 22 267; 17.9%, P < .001), and adenoidectomy only (n = 21 167; 17.1%, P < .001). Among adolescents, the 3 most common procedures were knee arthroscopy (n = 11 816, 27.2%), dental surgery (n = 10 320, 23.7%), and tonsillectomy (n = 9823, 22.6%). School-aged children most commonly underwent tonsillectomy (n = 23 098, 57.8%), followed by adenoidectomy only (n = 6048, 15.1%) and dental surgery (n = 5747, 14.4%). Among preschool-aged children, tonsillectomy was the most common surgery (n = 13 540, 33.5%), followed by adenoidectomy only (n = 13 515, 33.5%) and dental surgery (n = 6200, 15.4%).

Prescription Likelihood, Average MME, Days Supplied, and Refill Trends Over Time

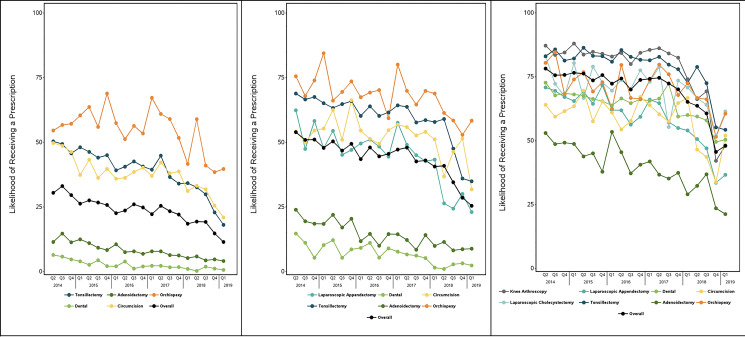

Comparing the first quarter of the 5-year study period with the last quarter, the percentage of adolescents filling an opioid prescription after surgery decreased from 78.2% (95% confidence interval [CI] 76.3–80.1) to 48.0% (95% CI 45.8–50.1); the percentage also decreased from 53.9% (95% CI 51.6–56.2) to 25.5% (95% CI 23.5–27.5) among school-aged children and from 30.4% (95% CI 28.6–32.2) to 11.5% (95% CI 10.1–12.9) among preschool-aged children (P < .001 for all groups; Fig 1). The likelihood of receiving a prescription varied across procedures; among adolescents, opioids were most common after knee arthroscopy, tonsillectomy, orchiopexy, and laparoscopic cholecystectomy, whereas in preschool- and school-aged children, opioids were most commonly prescribed after orchiopexy, tonsillectomy, and circumcision.

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of children who received a prescription for opioids after surgery, overall and by procedure, 2014 to 2019. Each figure displays, by year, the percentage of children undergoing a given surgery who did not receive a prescription for opioids when an equivalent recovery without opioids was considered possible. Panels contain data for the relevant procedures specific to the 3 age groups: A, Infant to 4 years of age; B, 5 to 10 years age; and C, 11 to 17 years of age.

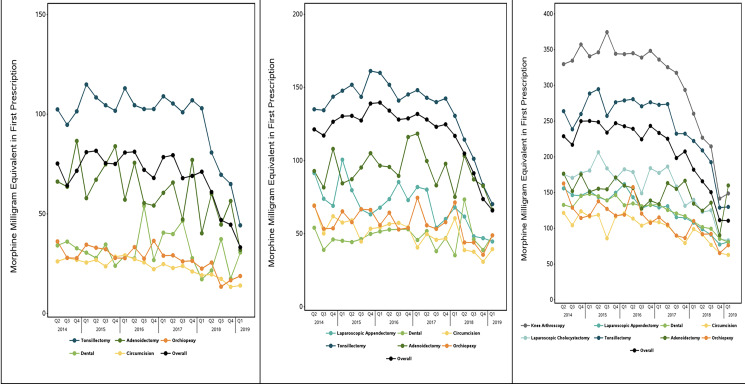

The average MME dispensed in the first prescription declined over the study period from 228.9 (95% CI, 220.1–237.7) to 110.8 (95% CI, 105.6–115.9) among adolescents, from 121.3 (95% CI, 116.7–125.9) to 65.9 (95% CI, 61.1–70.7) among school-aged children, and from 75.3 (95% CI, 70.2–80.3) to 33.2 (95% CI, 30.1–36.3) among preschool-aged children. (P < .001 for all groups; Fig 2). The average days’ supply in the first prescription declined over the study period from 5.2 days (95% CI, 5.1–5.4) to 3.0 days (95% CI, 2.9–3.1) among adolescents, 7.7 days (95% CI, 7.4-7.9) to 3.4 days (95% CI, 3.2–3.6) among school-aged children, and 8.0 days (95% CI, 7.6–8.3) to 3.3 days (95% CI, 3.1–3.6) among preschool-aged children (Supplemental Fig 5). The likelihood of receiving an opioid refill decreased from 12.7% (95% CI, 11.1%–14.3%) to 5.4% (95% CI, 4.4%–6.3%) among adolescents, 5.1% (95% CI, 4.1%–6.1%) to 3.1% (95% CI, 2.3%–3.8%) among school-aged children, and 1.6% (95% CI, 1.1%–2.1%) to 0.51% (95% CI, 0.21%–0.81%) among preschool-aged children (P < .001 for all comparisons; Supplemental Fig 4). Hydrocodone was the most commonly prescribed opioid among all 3 groups over the study period, followed by oxycodone; although the likelihood of filling a hydrocodone prescription reflected overall trends, oxycodone prescribing remained static overall in the 2 younger age groups until a modest decline was noted beginning in 2018 (Supplemental Fig 6).

FIGURE 2.

Postoperative opioid prescription quantity among children who received an opioid prescription, overall and by procedure, 2014 to 2019. Panels contain the total amount of opioid in MME dispensed in the first opioid prescription filled within 7 days after surgeries specific to the 3 age groups: A, Infant to 4 years of age; B, 5 to 10 years of age; and C, 11 to 17 years of age.

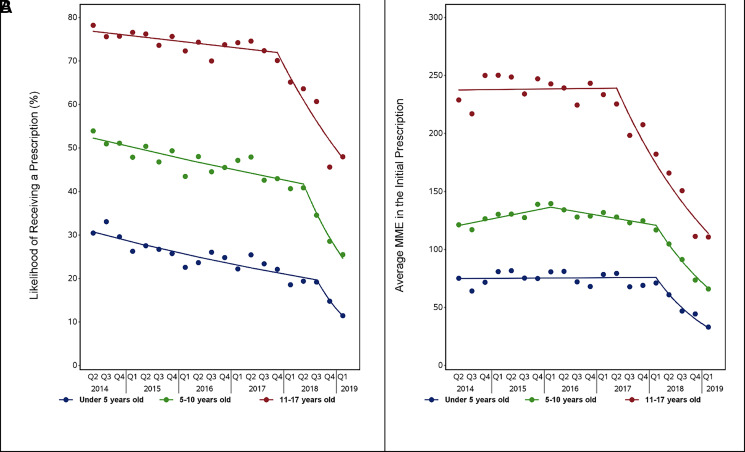

Joinpoint Regression

Our Joinpoint analysis of temporal trends in the likelihood of filling an opioid prescription revealed an initial period of gradual change followed by a period of more rapid decline (Fig 3; Table 2). Although this pattern occurred in all age groups, the timing of the trend change differed by age. Adolescents were the first to demonstrate a sharp change in the likelihood of filling a prescription. The quarterly decrease in prescribing was 0.47% per quarter (P = .04 for trend) until quarter 4 of 2017, when it decreased to 8.3% per quarter (P < .001) between quarter 4 of 2017 and quarter 1 of 2019. School-aged children followed a similar trajectory with a decrease of 1.4% per quarter (P < .001) from the beginning of the study period until quarter 2 of 2018; after this point, prescribing decreased by 17.6% per quarter (P < .001) until the end of the study period. Among preschool-aged children, prescribing decreased slightly until quarter 3 of 2018 (2.6% per quarter, P < .001), when it began to decline rapidly (27.5% per quarter, P = .09). Similar patterns were observed in Joinpoint regressions examining trends in average MME dispensed over time. We also confirmed the changes in trends identified by Joinpoint regression for odds of receiving a prescription in a segmented regression analysis that controlled for potential confounders (Supplemental Table 5).

FIGURE 3.

Joinpoint regression models by age group, 2014 to 2019. Panels contain (A) the likelihood of receiving an opioid prescription after surgery and (B) the total amount of opioid in MME dispensed in the first opioid prescription filled within 7 days after surgery, specific to the 3 age groups.

TABLE 2.

Joinpoint Regression Analysis for the Likelihood of Receiving an Opioid Prescription and Average MME, if Issued, by Age Group

| Likelihood of Receiving a Prescription | Average MME Dispensed in Initial Prescription | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trend 1 | Trend 2 | Trend 1 | Trend 2 | Trend 3 | |||||||

| Quarter Percentage Change (SE) | P | Quarter Percentage Change (SE) | P | Quarter Percentage Change (SE) | P | Quarter Percentage Change (SE) | P | Quarter Percentage Change (SE) | P | ||

| 0–4 y | −2.6 (0.003) | <.001 | −27.5 (0.15) | .09 | 0.09 (0.005) | .85 | −21.2 (0.04) | <.001 | — | — | |

| 5–10 y | −1.4 (0.002) | <.001 | −17.6 (0.04) | <.001 | 1.8 (0.004) | .002 | −1.5 (0.005) | .007 | −14.9 (0.02) | <.001 | |

| 11–17 y | −0.4 (0.002) | .04 | −8.3 (0.02) | <.001 | 0.06 (0.006) | .92 | −10.6 (0.01) | <.001 | — | — | |

SE, standard error; —, not applicable.

Discussion

Among 124 249 opioid-naïve children undergoing 8 common pediatric surgeries between 2014 and 2019, opioid prescribing declined substantially over time; prescribing first decreased gradually from 2014 through late 2017, followed by a more rapid period of decline from 2017 through 2019. Both the onset and the magnitude of decrease in the likelihood of filling an opioid prescription differed for adolescents, school-aged children, and preschool-aged children. Overall, prescribing was more common as age increased. We noted that the rate of decline in prescribing likelihood was steeper among younger children and that they received an increased days’ supply compared with adolescents. With regard to the average MME dispensed, we noted similar trends in the rate of decline that began first among adolescents. As an example of change in prescribing trends, the average preschool-aged child who filled an opioid prescription at the beginning of the study period received 75.3 MME, ∼15 5-mg hydrocodone tablets, and 33.2 MME, ∼6.5 5-mg tablets, at the end of the study period. The latter amount is equivalent to a 7-day supply for an average 4-year-old.

Our Joinpoint analyses characterized specific moments in time when rapid deescalation of routine opioid prescribing began. The drop in prescribing occurred first among adolescents in quarter 4 of 2017. School-aged children followed a similar pattern in quarter 2 of 2018. Preschool-aged children were noted to begin to exhibit this decrease 3 months later in quarter 3 of 2018. The results do not identify the specific events that caused these declines; however, there are several possible explanations. First, the declines in prescribing may have been a delayed response to the Food and Drug Administration’s April 2017 restriction on use of tramadol and codeine in children and increased attention placed on the risks of opioid prescribing after pediatric surgery when they were not needed.24 However, these recommendations focused on children under the age of 12 although changes were first seen among adolescents. Second, a series of studies that discussed the risks of opioid prescribing after pediatric surgery, including potential risks of new chronic use with excessive prescribing,9,10 was published in early 2018. It is possible that increasing general awareness of these risks before study publication may have contributed to prescribing decline when it was not indicated. Third, in a previous study, our group identified decreases in opioid prescribing after surgery associated with the release of a guideline on opioid prescribing for chronic pain by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in March 2016.25 It is possible that decreases observed in children could reflect a “spillover effect” of these guidelines from adult to pediatric prescribers. Of note, Renny et al used pharmacy claims data to identify an overall downtrend in all-cause pediatric opioid prescriptions between 2006 and 2018, suggesting that the declines observed here may be reflective of broader trends away from opioids for pain management in children that were not limited to the context of surgery.13 It is also possible that local or state policy changes, health system initiatives, or insurer policies for the coverage of pain treatments may have contributed to changes over time in opioid dispensing trends after surgery in children

Our findings have helped to fill significant gaps in knowledge with regard to opioid dispensing and pain management in pediatrics. The trend toward deadoption identified by our group is supported by a growing body of evidence suggesting that opioids can be discretionary after common pediatric surgeries associated with mild to moderate pain.12,26,27 For example, society guidelines for the most common surgery studied, tonsillectomy, first recommended nonopioid analgesics as first-line therapy in February 2019 after data demonstrated equivalent pain control for most children.28 Increasing knowledge prompted the publication of Michigan OPEN’s first national pediatric opioid prescribing range recommendations in May 2020 and the first comprehensive expert consensus guidelines specific to pediatric surgery for discretionary opioid use in January 2021.3,28 With increasing awareness of multimodal pain management and new knowledge of prescribing trends specific to each age group and surgery, we recommend the use of our results to inform targeted guideline implementation efforts.

Limitations

This study has limitations. Our patient population was from a private insurance claims database, and it is possible that findings may not be broadly applicable to patients covered by public insurance programs or patients without insurance. We cannot rule out that disparities in pain management did not increase during the study period, and additional research is indicated to characterize these disparities. In addition, although we were able to document prescribing trends after surgery, we were unable to characterize the opioid quantity consumed by individual children and their family’s unique perception of postoperative pain management, and additional research is indicated. Although we noted that opioid refills decreased over the study period, we were not able to definitively measure pain experience, including pain scores and patient satisfaction. Finally, at the societal level, patient-level variables may have changed over the study period with possible implications for influence on prescribing, but it is reassuring that our study cohort remained demographically similar over time.

Conclusions

We identified that the deadoption of routine opioid prescribing after common pediatric surgeries occurred during the study period. This trend was first noted in adolescents in late 2017, and it was then identified among school-aged and preschool-aged children over time. Additional research is indicated to better understand the reasons underlying changes in patterns of opioid prescribing for children of different ages after surgery.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

- CI

confidence interval

- CPT

current procedure terminology

- MME

morphine milligram equivalents

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

Footnotes

FUNDING: This work is funded by R01DA042299 (M.D.N. and H.W.) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (North Bethesda, Maryland) and the University of Pennsylvania’s McCabe Foundation (T.N.S.; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania). Neither funding source had any role in the design or conduct of the study. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Drs Neuman and Sutherland had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis; they also obtained data, conceptualized and designed the study, acquired and analyzed data, and drafted and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content; Dr Wunsch conceptualized and designed the study, obtained funding, performed data analysis, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content; Mr Newcomb participated in study design, statistical analysis, and data interpretation and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Ms Gaskins participated in study design, coordinated data acquisition and management, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Hadland participated in study design and data interpretation and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content.

References

- 1. Wunsch H, Wijeysundera DN, Passarella MA, Neuman MD. Opioids prescribed after low-risk surgical procedures in the United States, 2004-2012. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1654–1657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Franz AM, Martin LD, Liston DE, Latham GJ, Richards MJ, Low DK. In pursuit of an opioid-free pediatric ambulatory surgery center: a quality improvement initiative. Anesth Analg. 2021;132(3): 788–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kelley-Quon LI, Kirkpatrick MG, Ricca RL, et al. Guidelines for opioid prescribing in children and adolescents after surgery: an expert panel opinion. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(1):76–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Michigan Opioid Prescribing Engagement Network (OPEN) . Prescribing recommendations. Available at: https://michigan-open.org/prescribing- recommendations/. Accessed May 25, 2021

- 5. Ceelie I, de Wildt SN, van Dijk M, et al. Effect of intravenous paracetamol on postoperative morphine requirements in neonates and infants undergoing major noncardiac surgery: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;309(2): 149–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kelly LE, Sommer DD, Ramakrishna J, et al. Morphine or ibuprofen for post-tonsillectomy analgesia: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):307–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moore RA, Derry S, Aldington D, Wiffen PJ. Single dose oral analgesics for acute postoperative pain in adults - an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; (9): CD008659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Horton JD, Munawar S, Corrigan C, White D, Cina RA. Inconsistent and excessive opioid prescribing after common pediatric surgical operations. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54(7):1427–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harbaugh CM, Lee JS, Hu HM, et al. Persistent opioid use among pediatric patients after surgery. Pediatrics. 2018; 141(1):e20172439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harbaugh CM, Nalliah RP, Hu HM, Englesbe MJ, Waljee JF, Brummett CM. Persistent opioid use after wisdom tooth extraction. JAMA. 2018;320(5):504–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Neuman MD, Bateman BT, Wunsch H. Inappropriate opioid prescription after surgery. Lancet. 2019;393(10180): 1547–1557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Van Cleve WC, Grigg EB. Variability in opioid prescribing for children undergoing ambulatory surgery in the United States. J Clin Anesth. 2017;41:16–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Renny MH, Yin HS, Jent V, Hadland SE, Cerdá M. Temporal trends in opioid prescribing practices in children, adolescents, and younger adults in the US from 2006 to 2018. JAMA Pediatr. 2021; 175(10):1043–1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hardin AP, Hackell JM; Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine . Age limit of pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2017; 140(3):e20172151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wiener RS, Welch HG. Trends in the use of the pulmonary artery catheter in the United States, 1993-2004. JAMA. 2007; 298(4):423–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Optum Research Data Assets . Product sheets. Available at: https://www.optum.com/content/dam/optum/resources/productSheets/5302_Data_Assets_ Chart_Sheet_ISPOR.pdf. Accessed December 1 2020

- 17. Howard R, Waljee J, Brummett C, Englesbe M, Lee J. Reduction in opioid prescribing through evidence-based prescribing guidelines. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(3):285–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kamdar PM, Liddy N, Antonacci C, et al. Opioid consumption after knee arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2021; 37(3):919–923.e10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barazanchi AWH, MacFater WS, Rahiri JL, Tutone S, Hill AG, Joshi GP; PROSPECT Collaboration . Evidence-based management of pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a PROSPECT review update. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121(4):787–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Opioid oral morphine milligram equivalent (MME) conversion factors. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/Opioid-Morphine-EQ-Conversion- Factors-April-2017.pdf. Accessed April 14, 2019

- 22. Gillis D, Edwards BPM. The utility of joinpoint regression for estimating population parameters given changes in population structure. Heliyon. 2019; 5(11):e02515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) . FDA drug safety communication: FDA restricts use of prescription codeine pain and cough medicines and tramadol pain medicines in children. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug- safety-communication-fda-restricts- use-prescription-codeine-pain-and- cough-medicines-and. Accessed July 1, 2021

- 25. Sutherland TN, Wunsch H, Pinto R, et al. Association of the 2016 US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention opioid prescribing guideline with changes in opioid dispensing after surgery. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2111826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Monitto CL, Hsu A, Gao S, et al. Opioid prescribing for the treatment of acute pain in children on hospital discharge. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(6): 2113–2122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stokes SC, Theodorou CM, Brown EG, Saadai P. Variations in perceptions of postoperative opioid need for pediatric surgical patients. JAMA Surg. 2021; 156(9):885–887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mitchell RB, Archer SM, Ishman SL, et al. Clinical practice guideline: tonsillectomy in children (update)-executive summary. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;160(2):187–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.