Abstract

Diabetes may prevent kidney repair and sensitize the kidney to fibrosis or scar formation. To test this possibility, we examined renal fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) in diabetic mouse models. Indeed, UUO induced significant more renal fibrosis in both Akita and STZ-induced diabetic mice than in non-diabetic mice. The diabetic mice also had more apoptosis and interstitial macrophage infiltration during UUO. In vitro, hypoxia induced higher expression of the fibrosis marker protein fibronectin in high glucose-conditioned renal tubular cells than in normal glucose cells. Mechanistically, hypoxia induced significantly more hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α (HIF-1 α) in high glucose cells than in normal glucose cells. Inhibition of HIF-1 attenuated the expression of fibronectin induced by hypoxia in high-glucose cells. Consistently, UUO induced significantly higher HIF-1α expression along with fibrosis in diabetic mice kidneys than in non-diabetic kidneys. The increased expression of fibrosis induced by UUO in diabetic mice was diminished in proximal tubule-HIF-1α-knockout mice. Together, these results indicate that diabetes sensitizes kidney tissues and cells to fibrogenesis probably by enhancing HIF-1 activation.

Keywords: High glucose, diabetic kidney disease, fibrosis, HIF-1

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus (DM), a disease of abnormally high blood glucose levels, is one of the most common and fastest growing diseases worldwide(1). Vascular complications of both microvascular system (vascular in kidney, eye and nerves) and macrovascular system (coronary and cerebrovascular arteries), are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality of diabetic patients, carrying enormous health and financial burden in developed and developing countries(2). And DM is associated with the development of complications in the heart, eyes, kidneys and other organs.

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD), as a major complication of DM, is the leading cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD), and it is associated with glomerular hyperfiltration, microalbuminuria, overt proteinuria, glomerular and tubular basement membranes thickening, podocyte loss, tubular atrophy, and a decline in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR)(3–5). However, recent epidemiological studies call for more attention to the early decline of GFR occurs in patients with only microalbuminuria or without albuminuria, particular in type 2 diabetes(6). The development of diabetes and its complications are complex, multifactorial conditions with both environmental and genetic components(3–5). Approximately 30 to 40% of patients with type1 or 2 diabetes eventually develop DKD, and DKD generally emerge around 10 to 20 years after onset of diabetes in these patients.

In both animal models of diabetes and in diabetic patients, renal interstitial fibrosis is suggested to contribute to the pathogenesis of DKD(3–5). We hypothesized that kidney tissues and cells in diabetes are highly susceptible to profibrotic stress. To test this possibility, in this study we examined renal fibrosis induced by UUO in diabetic mouse models. Indeed, UUO induced significant more renal fibrosis in both Akita and STZ-induced diabetic mice in vivo. In vitro, hypoxia induced higher expression of the fibrosis marker protein fibronectin in high glucose-conditioned renal tubular cells. Mechanistically, hypoxia induced significantly more HIF-1α in high glucose cells than in normal glucose cells. Inhibition of HIF-1α attenuated the increased expression of fibronectin both in vivo and in vitro models. Together, these results indicate that diabetes may sensitize kidney tissues and cells to fibrogenesis by enhancing HIF-1 signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and reagents

Antibodies were purchased from the following sources: anti-HIF-1α from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI); anti-fibronectin, anti-Bnip3, anti-α-SMA, and anti-collagen IV from Abcam (Cambridge, MA); anti-F4/80 from eBioscience (San Diego, CA); anti-cyclophilin B from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA); the secondary antibodies for immunoblot analysis from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA); the secondary antibodies for immunohistochemistry from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). YC-1 and streptozotocin were from Sigma (St.Louis, MO).

Animals

C57BL/6J, C57BL/6J-Ins2Akita/+ and HIF1α-floxed breeder mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). PEPCK–CRE transgenic mice was originally from Dr. Volker Hasse at Vanderbilt University school of Medicine (Nashville, TE). PT-HIF1α knockout mice were established by crossing HIF1α-floxed mice with PEPCK-CRE transgenic mice as described in our previously work(7). For STZ induction of diabetes, mice at 3–4 weeks of ages were injected with 50mg/kg body weight STZ for five consecutive days according to a standard protocol(8). STZ-induced mice were sustained for another 2–3 weeks before UUO surgery and the fasting blood glucose was measured during this time. For the Akita diabetic model, genotyping of the offspring was performed according to the protocol recommended by the Jackson Laboratory. Ins2Akita/+ and wild-type Ins2+/+ littermates were used at 6–8 weeks for experiments. Fasting blood glucose was measured once a week using a glucometer after fasting for 6–8h. The animals with more than 200mg/dl fasting blood glucose for two or three consecutive readings were considered diabetic. All animals were maintained at Charlie Norwood VA Medical Center under 12-hour light/12-hour dark pattern with free access to food and water. The experiments were carried out according to the protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committee in Charlie Norwood VA Medical Center, Augusta, GA.

UUO surgery and YC-1 injection

Mice (6–8 weeks old) were anesthetized with 60mg/kg pentobarbital sodium (intraperitoneally) and kept on a Homeothermic Blanket Control Unit (Harvard Apparatus, 507220f, Holliston, MA) with a rectal probe to monitor and maintain body temperature at 36.5°C. A left incision was made and the left ureter was exposed and isolated for ligation with 4–0 silk sutures at 2 points. Control mice underwent the same procedures but without ligation(9).

To test the inhibition of HIF1α, YC-1 (30μg/g) or vehicle (DMSO) was administrated from the day of UUO surgery to the day before sacrificing the mice. All experiment animals were sacrificed after 7 days and 14 days of UUO. Blood collection and kidney harvest were done as described in previous work(10).

Cell Lines and Hypoxia Treatment

The mouse proximal tubule BUMPT-306 cell line was a generous gift from Drs. Lieberthal and Schwartz at Boston University (Boston, MA). The stable rat RPTC line (RPTCs) with HIF1α knockdown were established in our previous studies(7). The cells were grown in DMEM medium with 10%FBS, MEM with 10%FBS and DMEM/F12 10%FBS, respectively. For hypoxia treatment, after overnight culture, the cells were transferred to hypoxia chamber (COY Laboratory Products, Ann Arbor, MI) with 1% oxygen and incubated with the medium that had been pre-equilibrated. Control group cells were grown in the medium with normal oxygen (21%)(11).

Analysis of Renal Function

Renal function was indicated by BUN and serum creatinine that were measured with the analytical kits from Biotron Diagnostics Inc (Hemet, CA) and Stanbio Laboratories (Boerne, TX), respectively.

Renal Histology Analysis

For routine analysis, kidneys were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Each sample was sectioned with 4μm and stained with standard Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) procedure. Masson’s trichrome staining was performed based on the manufacturer (Sigma-Aldrich, HT15). Collagen fibrils were stained with aniline blue. ImageJ was used to quantitatively evaluate the percentage area with positive fibrotic staining. 10–20 positive fields were randomly selected from each section. TdT-mediated dUTP mick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay was conducted by using the in situ Cell Death Detection kit from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN) as described in our recent work(10). For immunohistochemical staining of macrophage, kidney tissue sections were deparaffinized and subjected to antigen retrieval in 0.1M sodium citrate (pH 6.0 at 95–100°C) for 1h, followed by incubation with following reagents: 3%H2O2, blocking buffer (2% bovine serum albumin, 0.2% milk, 2% normal goat serum and 0.8% Triton-X-100), and avidin-biotin blocking reagent (Vector Laboratories, SP-2001). The slides were then exposed to anti-macrophage (1:100) at 4°C overnight and 1:500 biotinylated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Following signal amplification with Tyramide Signal Amplification Biotin System (Perkin Elmer, NEL700A001KT), the sections were incubated with a VECTAS- TAIN® ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, PK-6100) and color was developed with a DAB kit. For immunofluorescence, most of the procedures were the same as the Immunohistochemical staining except the incubation with the fluorescent second antibody at the second day. 10 to 20 fields were randomly selected from each section and the percentage of macrophage-positive stained area was quantitated using ImageJ.

Immunoblot analysis

The protein of whole cell lysate and kidney tissues was measured by the BCA reagent kit from Thermo Scientific. Equal amounts of protein were loaded to each lane of the SDS-polyacrylamide gel for electrophoresis and then transferred to PVDF membrane. After blocking with 5% milk for 1 hour at room temperature, the membrane was exposed to the primary antibody at 4°C overnight. The blot was washed with the TBST for 4 times and then incubated with the horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated secondary antibody. The blot signal was revealed with a chemiluminescence kit (Thermo Scientific).

Statistical analysis

All values were expressed as mean ± SD. The GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA) was used for statistical analysis. Comparison between two groups were performed by paired Student t-test or unpaired Student t-test. For multiple comparisons, ANOVA was used. Data were analyzed with a Prism 6.0 software packet (San Diego, CA). P value of <0.05 was considered to show significant difference.

RESULTS

UUO induces more fibrosis in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice than in non-diabetic mice.

To determine the sensitivity of diabetic mice to renal fibrosis, we initially compared streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic mice (DM) and nondiabetic mice (ND) in response to unilateral urethral obstruction (UUO), a commonly used model for inducing renal interstitial fibrosis. To this end, after 2 weeks of verified hyperglycemia in STZ-induced mice, DM and ND mice were subjected UUO surgery and samples were collected 1 or 2 weeks later for analysis. There was no significant difference in body weight between DM and ND mice (data not shown). After UUO, DM and ND mice did not show significant differences or increases in blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine either (data not shown). This was not surprising, because (1) the STZ mice were at the early stage of DM with only 3–4 weeks of hyperglycemia without renal complications, and (2) in UUO, the contralateral kidney was largely intact to support the excretory function.

Interestingly, we detected more collagen fibril deposition in DM mice than in ND mice by Masson trichrome staining (Figure 1A, 1B). Consistently, immunoblot analysis showed higher levels of expression of fibrosis hallmark proteins, such as fibronectin and α-SMA, in DM mice kidneys after UUO than in ND mice (Figure 1C, 1D). In addition, UUO induced apoptosis in kidney tissues in both DM and ND mice as detected by TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay, and notably more apoptotic cells were detected in DM mice than ND mice after UUO (Figure S1A, S1B). Together, these results indicate that UUO induces more severe renal pathologies in early diabetic mice than non-diabetic mice.

Figure 1. UUO induces more fibrosis in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice than in non-diabetic mice.

C57BL/6J mice were treated with STZ to induce diabetes (DM), while control mice were given vehicle solution as non-diabetic mice (ND). The mice were then subjected to UUO for 1 week (UUO1W) or 2 weeks (UUO2W) or sham surgery without ureter ligation (sham). (A) Representative imagines of Masson’s trichrome staining. (B) Quantification of Masson’s trichrome positive areas in whole kidney tissue. *p<0.05, significant difference vs. their corresponding sham groups. # p<0.05, significant difference vs. ND group at each time point. (C) Representative blots of fibronectin and α-SMA with cyclophilin B as the loading control. (D) The fibronectin and α-SMA signals in immunoblots were analyzed by densitometry to calculate the ratio over cyclophilin B and expressed as mean ± SD. *p<0.05, significant difference vs. their corresponding sham group. # p<0.05, significant difference vs. ND group at each time point.

Akita diabetic mice are more susceptible to UUO-induced renal fibrosis.

Akita mice is a model of type 1 diabetes, which has a single point mutation of insulin 2 gene, leading to dysfunction of pancreatic β cells as a result of misfolding of insulin 2. These mutant mice often develop hyperglycemia of diabetes starting from 3–4 weeks of age(12). We confirmed the blood glucose level in these mice once a week for consecutively 3–4 weeks. Akita mice had 490.4±31.79mg/dl blood glucose, whereas 171.8±12.32mg/dl in their wild-type littermates. During our observation period of 5–6 weeks of age, Akita and wild-type mice did not significantly differ in their body weight, BUN, serum creatinine and renal histology (Figure S2).

Compared with sham-operated control, UUO for 1 or 2 weeks (UUO1W and UUO2W) induced renal fibrosis in both wild-type mice and Akita mice. However, UUO induced significantly more fibrosis in Akita mice than in wild-type mice, as shown by Masson trichrome staining (Figure 2A, 2B). In addition, Akita mice showed higher fibronectin and α-SMA expression in kidney tissues by immunoblot analysis (Figure 2C, 2D).

Figure 2. Akita diabetic mice are more susceptible to UUO-induced renal fibrosis.

Akita diabetic mice and wild-type non-diabetic mice were subjected to UUO for 1 week (UUO1W) or 2 weeks (UUO2W) or sham surgery without ureter ligation (sham). (A) Representative imagines of Masson’s trichrome staining. (B) Quantification of Masson’s trichrome positive areas in whole kidney tissue field. *p<0.05, significant difference vs. their corresponding sham groups. # p<0.05, significant difference vs. wild-type littermates at each time point. (C) Representative blots fibronectin and α-SMA with cyclophilin B as the loading control. (D) The fibronectin and α-SMA signals in immunoblots were analyzed by densitometry to calculate the ratio and expressed as mean ± SD. *p<0.05, significant difference vs. their corresponding sham group. # p<0.05, significant difference vs. wild-type littermates at each time point.

UUO induces higher levels of macrophage infiltration and apoptosis in Akita mice kidneys than in wild-type.

We further detected renal apoptosis and inflammation in WT and Akita mice during UUO. No TUNEL-positive cells were detected in the sham groups. After UUO, there was a time-dependent increase of renal apoptosis in WT and Akita mice, which was more severe in Akita mice (Figure 3A, 3B). We analyzed F4/80 staining of macrophages in kidney tissues to indicate inflammation. As shown in Figure 3C, almost no F4/80 staining was detected in the sham groups. UUO induced an accumulation of F4/80 staining-positive macrophages in both WT and Akita mice. At 1 week of UUO, Akita mice had more macrophages infiltration in kidney tissues than wild-type mice. Interestingly, at 2 weeks of UUO, macrophages decreased in the kidneys of Akita mice while they kept increasing in wild-type mice and, as a result, there were more F4/80 staining-positive macrophages in wild-type kidneys (Figure 3C, 3D). Similarly, STZ-induced diabetic mice also had more apoptosis and macrophage infiltration than nondiabetic mice (Figure S1). These observations suggest a chronic pathological condition in obstructive kidneys, which may be exacerbated by hyperglycemia or diabetes.

Figure 3. UUO induces higher levels of macrophage infiltration and apoptosis in Akita mice kidneys than in wild-type.

Akita diabetic mice and wild-type non-diabetic mice were subjected to UUO for 1 week (UUO1W) or 2 weeks (UUO2W) or sham surgery without ureter ligation (sham). (A) Representative images of TUNEL staining. (B) Quantification of TUNEL positive cells in kidney tissues. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. *p<0.05, significant difference vs. their corresponding sham group. # p<0.05, significant difference vs. wild-type littermates at each time point. (C) Representative images of F4/80 staining of macrophages. (D) Quantitative analysis of F4/80 staining. *p<0.05, significant difference vs. their corresponding sham groups. # p<0.05, significant difference vs. wild-type littermates at each time point.

Increased expression of HIF-1α in high glucose BUMPT cells and in diabetic kidneys.

To understand the mechanism whereby UUO induced more severe renal fibrosis in diabetic/hyperglycemic kidney tissues, we established an in vitro model by incubating normal or high glucose-conditioned BUMPT cells under hypoxia. To this end, BUMPT cells were seeded in normal glucose DMEM medium for overnight growth and then changed to the media with different concentrations of glucose (5.5mM glucose, 5.5mM glucose+24.5mM mannitol and 30mM glucose), then cultured in 1% oxygen chamber or 21% oxygen chamber for 48h, 72h and 96h. Hypoxia induced fibrotic changes in BUMPT cells as indicated by the expression of fibronectin, a fibrosis marker protein. Notably, a dramatic fibronectin induction by hypoxia was shown in high (30mM) glucose cells (Figure 4A, 4B). After 48 h hypoxia, these cells had more than 2-fold of fibronectin over 5.5mM glucose cells and 5.5mM glucose+24.5mM mannitol cells (Figure 4B). As expected, hypoxia induced HIF-1α in both normal and high glucose cells. Interestingly, HIF-1α induction was markedly higher in high glucose cells than normal glucose cells, regardless of mannitol (Figure 4A, 4B). To verify this observation in vivo, we compared HIF-1α expression in kidneys after UUO in Akita diabetic mice and wild-type non-diabetic mice. As shown in Figure 4C and 4D, UUO induced a time-dependent accumulation of HIF-1α in kidney tissues in wild-type mice, and notably this induction was significantly higher in diabetic Akita mice. Similar induction was detected for Bnip3, a transcriptional target gene of HIF-1α (Figure 4C, 4D). Consistently, immunostaining detected more HIF-1α signal in kidney tubules of Akita mice than wild-type mice (Figure 4C). Together, these in vitro and in vivo results indicate a higher induction of HIF-1α in diabetic kidney tissues and cells, which may contribute to increased fibrosis.

Figure 4. Increased HIF-1α induction in high glucose BUMPT cells and in diabetic kidneys.

BUMPT cells were cultured in 5.5mM normal glucose without or with 24.5mM mannitol and 30mM high glucose under hypoxia or normoxia for 48h. Akita diabetic mice and wild-type non-diabetic mice were subjected to UUO for 1 week (UUO1W) or 2 weeks (UUO2W) or sham surgery without ureter ligation (sham). (A) Representative immunoblots showing that hypoxia induces higher fibronectin and HIF1α expression in 30mM high glucose BUMPT cells than in 5.5mM normal glucose without or with 24.5mM mannitol (M). (B) Densitometry analysis of the blots. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. *p<0.05, significant difference vs. each group under normoxia condition. # p<0.05, significant difference vs. other groups undergo hypoxia condition. (C) Immunoblots showing UUO induced higher HIF1α and Bnip3 in Akita diabetic mice than in wild-type. (D) Densitometry analysis of the HIF1α and Bnip3 blots. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. *p<0.05, significant difference vs. their corresponding sham group. # p<0.05, significant difference vs. wild-type littermates at each time point. (E) Representative images of HIF1α immunostaining in kidney tissues.

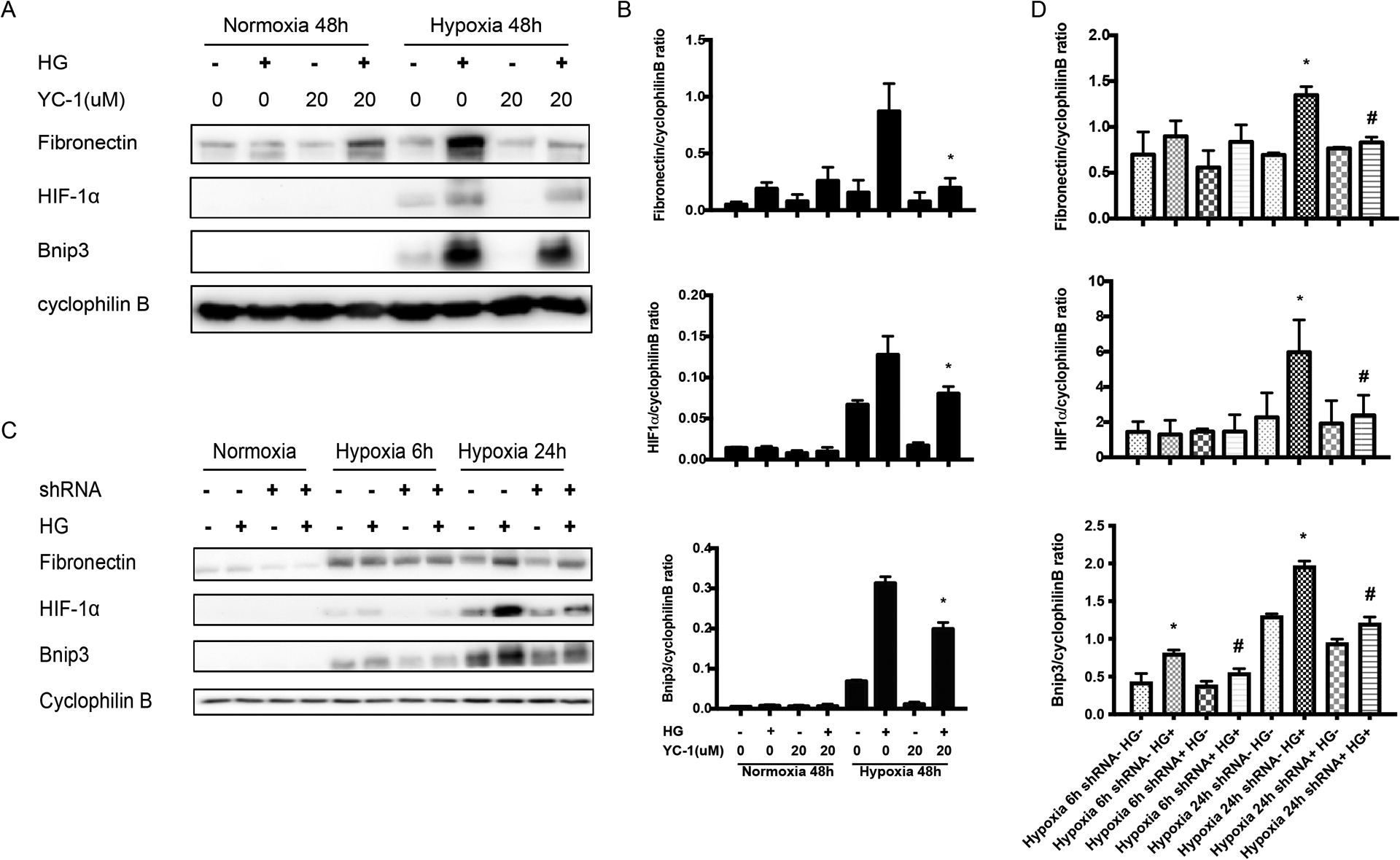

Inhibition of HIF-1α by YC-1 and knockdown HIF-1α alleviate the fibrosis protein expression in BUMPT cells and RPTC cells

Hypoxia and HIFs have been implicated in the development of renal fibrosis and chronic kidney disease(13–15). To determine the role of HIF-1 in fibrotic response in diabetic kidney tissues and cells, we first tested the effect of YC-1, a pharmacologic inhibitor of HIF-1α(16, 17). As shown in figure 5A, YC-1 inhibited the induction of fibronectin, which was consistent with the inhibition of HIF-1α. Bnip3, a proapoptotic protein, was reported as one of the downstream factors of HIF-1α, also suppressed under hypoxia condition with YC-1, which was further confirmed by the densitometry analysis (Figure 5A, 5B).

Figure 5. Blockage of HIF1 reduces fibrotic changes during hypoxia of renal tubular cells.

BUMPT cells with or without YC-1 were cultured in 30mM glucose medium (HG+) or 5.5mM glucose+24.5mM Mannitol (HG-) medium under hypoxia or normoxia for 48h. RPTC cells with (shRNA+) or without (shRNA-) were cultured in HG+ or HG- medium, followed by hypoxia exposure for 6h and 24h. (A) Representative immunoblots showing the effect of YC-1 in high glucose-conditioned BUMPT cells exposed to normoxia and hypoxia conditions. (B) The immunoblots were analyzed by densitometry to calculate the ratio and expressed as mean ± SD. *p<0.05, significant difference vs. high glucose-conditioned BUMPT cells exposed to hypoxia. (C) Immunoblots of HIF-1α, Bnip3 and fibronectin of RPTC stable cells with (shRNA+) or without (shRNA-) in HG+ or HG- medium, followed by hypoxia exposure. (D) Densitometry analysis of the blots and expressed as mean ± SD. *p<0.05, significant difference vs. shRNA-+HG- group at 24h under hypoxia. # p<0.05, significant difference vs. shRNA-+HG+ group at 24h under hypoxia.

We further tested the effects of HIF-1α knockdown using the rat kidney proximal tubule cell (RPTC) lines established in our previous work(7, 18). RPTC cells with (shRNA+) or without (shRNA−) were cultured in 30mM glucose medium (HG+) or 5.5mM glucose+24.5mM Mannitol (HG−) medium, followed by hypoxia exposure. Hypoxia induced remarkably more HIF-1α in high glucose cells than in normal glucose cells (Figure 5C: lane 10 vs. lane 9), and this induction was attenuated by HIF-1α shRNA. Importantly, the increased induction of Bnip3 and fibronectin by hypoxia in high glucose cells were also attenuated in HIF-1α shRNA transfected cells (Figure 5C: lane 12 vs. lane 10). Densitometry of the blots further substantiated this conclusion (Figure 5D).

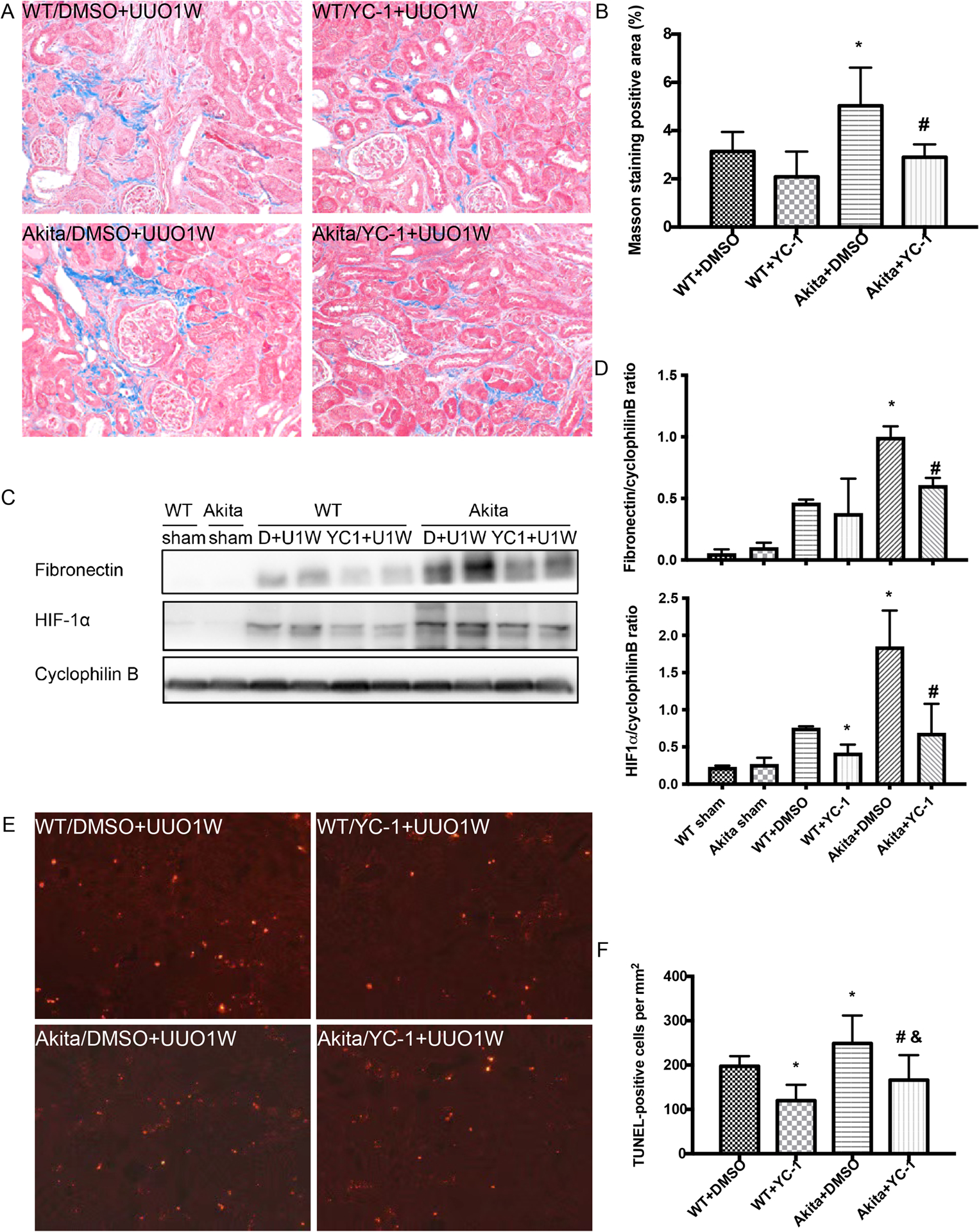

YC-1 attenuates the sensitivity of Akita diabetic mice to fibrosis

Based on above in vitro work, we further tested the effect of YC-1 in vivo in Akita diabetic mice. To monitor the possible side effect of YC-1 in this model, we checked body weight and blood glucose on the day of surgery, and also the third and sixth days following UUO surgery. As shown in Table 1, YC-1 did not significantly affect body weight, blood glucose and kidney function during the observation period. Next, we examined the effect on renal fibrosis. Masson’s trichrome staining showed that UUO induced more renal interstitial fibrosis in Akita mice than in wild-type mice (Figure 6A). Importantly, YC-1 had marginal inhibitory effects on renal fibrosis in wild-type mice, but it significantly reduced UUO-induced renal fibrosis in Akita mice (Figure 6A, 6B). In fact, YC-1 reduced renal fibrosis in Akita mice to the level of wild-type (Figure 6B). Consistently, YC-1 attenuated the accumulation of the fibrosis marker protein fibronectin during UUO in Akita mice (Figure 6C, 6D). We also detected significantly higher induction of HIF-1α in Akita mice kidneys than in wild-type during UUO, and this increased induction was diminished by YC-1 (Figure 6C, 6D). YC-1 suppressed renal apoptosis during UUO in both wild-type and Akita mice (Figure 6E, 6F).

Table 1. Effect of YC-1 on body weight/blood glucose and kidney function in UUO-treated Akita diabetic mice.

Akita diabetic mice and wild-type non-diabetic mice were treated with DMSO or YC-1, then subjected to UUO for 1 week (DMSO+UUO1W, YC-1+UUO1W) or sham surgery without ureter ligation (sham). Mouse body weight, blood glucose and kidney function were monitored on the day of UUO surgery, and also on the third and sixth days after UUO surgery.

| Day 0 | Day 3 | Day 6 | BUN | Creatinine | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BW(g)* | BG(mg/dl)# | BW(g)* | BG(mg/dl)# | BW(g)* | BG(mg/dl)# | (mg/dl) | (mg/dl) | |

| WT+DMSO | 20.27±0.92 | 145.00±35.00 | 20.20±0.95 | 150.32±49.08 | 19.81±0.78 | 141.00±46.36 | 39.28±0.91 | 0.30±0.09 |

| WT+YC-1 | 20.3±1.04 | 144.00±21.93 | 20.40±1.22 | 179.00±22.27 | 20.77±0.83 | 148.33±27.47 | 29.80±1.13 | 0.29±0.08 |

| Akita+DMSO | 17.71±1.27 | 504.67±38.81 | 17.97±1.07 | 493.67±62.17 | 17.67±0.87 | 541.33±67.95 | 34.26±5.78 | 0.38±0.02 |

| Akita+YC-1 | 18.13±0.67 | 516.33±31.77 | 18.20±0.53 | 520.67±36.69 | 18.10±0.82 | 528.00±59.10 | 31.47±3.56 | 0.34±0.05 |

BW: body weight,

BG: blood glucose

Figure 6. YC-1 attenuates the sensitivity of Akita diabetic mice to fibrosis.

Akita diabetic mice and wild-type non-diabetic mice were treated with DMSO or YC-1, then subjected to UUO for 1 week (DMSO+UUO1W, YC-1+UUO1W) or sham surgery without ureter ligation (sham). (A) Representative imagines of Masson’s trichrome staining. (B) Quantification of Masson’s trichrome positive areas in the whole kidney. *p<0.05, significant difference vs. WT+DMSO group. # p<0.05, significant difference vs. Akita+DMSO group. (C) Immunoblots of fibronectin and HIF1α in Akita diabetic mice and wild-type littermates treated with YC-1 or the vehicle solution DMSO following UUO surgery. (D) Densitometry of the blots to calculate the protein ratio and expressed as mean ± SD. *p<0.05, significant difference vs. WT+DMSO, # p<0.05, significant difference vs. Akita+DMSO group. (E) Representative images of TUNEL staining. (F) Quantification of TUNEL positive cells in kidney tissues. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. *p<0.05, significant difference vs. WT+DMSO, # p<0.05, significant difference vs. Akita+DMSO group, & p<0.05, significant difference vs. WT+YC-1 group.

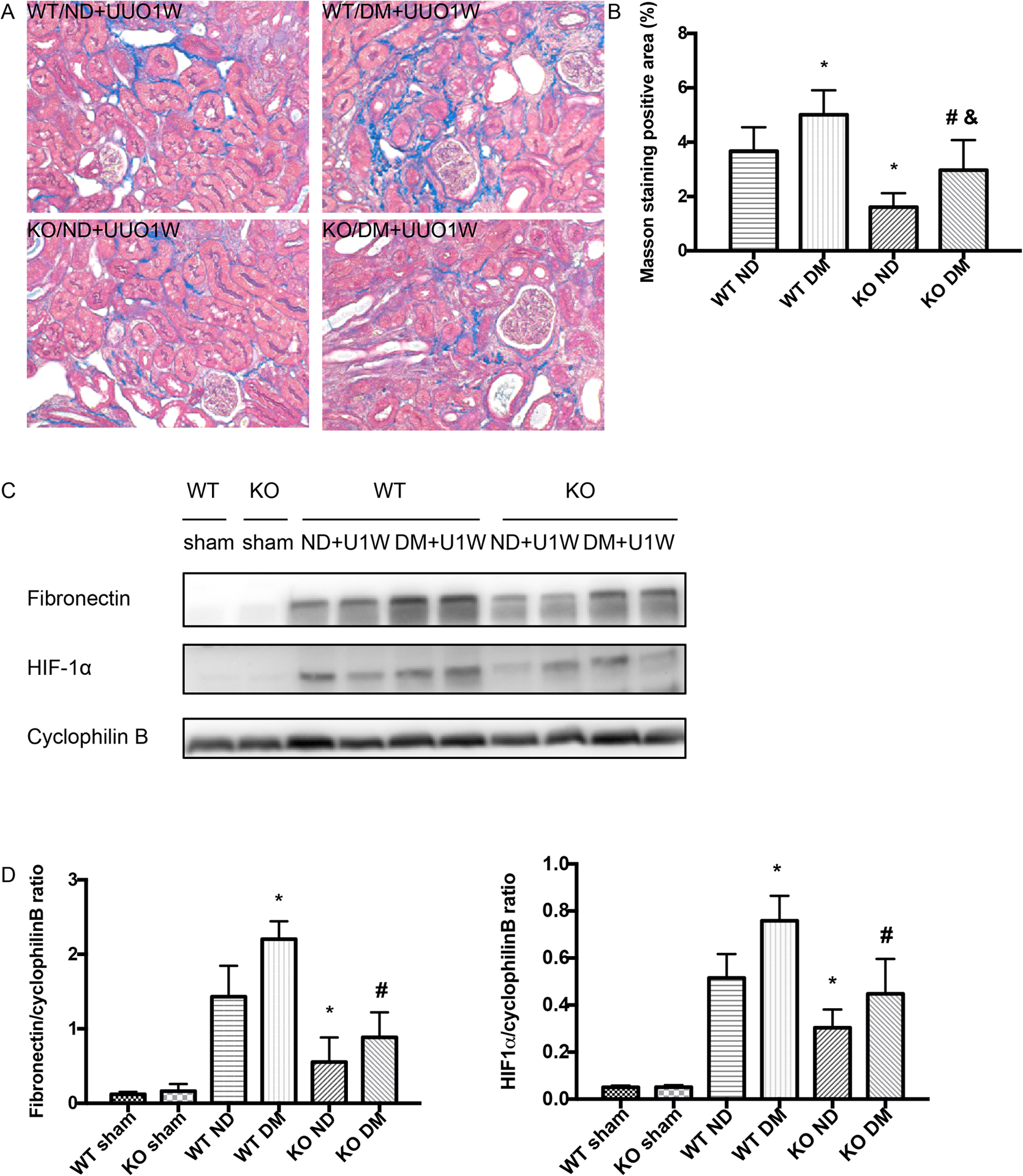

HIF-1α knockout from proximal tubules attenuates the sensitivity of STZ-diabetic mice to fibrosis

To further verify the role of HIF-1 in fibrosis sensitivity of diabetic kidneys, we examined proximal tubule-specific HIF-1α knockout mice model (PT- HIF-1α -KO) established in our previous work(7, 19). PT-HIF-1α-KO and their wild-type (PT-HIF-1α-WT) littermates were injected with STZ at the age of 3 weeks to induce diabetes. The induction of diabetes was confirmed by measuring blood glucose at 3–4 weeks after STZ injection. The mice were then subjected to 1 week of UUO. Masson’s trichrome staining showed that diabetes exaggerated UUO-induced renal fibrosis in wild-type mice, but the effect of diabetes was attenuated in PT-HIF-1α-KO mice (Figure 7A, 7B). Consistently, diabetes increased fibronectin accumulation in UUO kidneys in wild-type mice, and the effect of diabetes was much less in PT-HIF-1α-KO mice (Figure 7C, 7D). As expected, PT-HIF-1α-KO mice had less HIF-1α induction in kidneys than wild-type mice (Figure 7C, 7D). Together with the effects of YC-1 (Figure 6), these results support an important role of HIF-1 in the fibrosis sensitivity of diabetic kidneys.

Figure 7. HIF-1α knockout from proximal tubules attenuates the sensitivity of STZ-diabetic mice to fibrosis.

Proximal tubule-specific HIF-1α knockout mice model (PT- HIF-1α -KO) and their wild-type (PT-HIF-1α-WT) littermates were treated with STZ to induce diabetes (DM), while control mice were given vehicle solution as non-diabetic mice (ND). The mice were then subjected to UUO for 1 week (UUO1W) or sham surgery without ureter ligation (sham). (A) Representative images of Masson’s trichrome staining. (B) Quantification of Masson’s trichrome positive areas in the whole kidney. *p<0.05, significant difference vs. WT+ND group. # p<0.05, significant difference vs. WT+DM. &p<0.05, significant difference vs. KO+ND group. (C) Representative blots of fibronectin and HIF1α. Increased fibronectin induction by UUO in diabetic mice (lanes 5, 6) were attenuated in proximal tubule HIF-1α knockout mice (lanes 9, 10). (D) Densitometry of the blots. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. *p<0.05, significant difference vs. WT+ND group. # p<0.05, significant difference vs. WT+DM group.

DISCUSSION

Using cultured kidney cells as well as Akita or STZ diabetic mouse models, this study demonstrates convincing evidence for the renal fibrosis sensitivity in diabetes mellitus (DM). Mechanistically, this fibrotic sensitivity may involve increased level of inflammation as shown by macrophage infiltration and chronic tissue deterioration with increases in apoptosis. At the molecular level, significantly higher levels of HIF-1α were induced during fibrotic treatment in diabetic kidneys and high glucose-incubated renal tubular cells than in non-diabetic kidney tissues and cells. Notably, inhibition of HIF-1 diminished the renal fibrosis sensitivity of diabetic animals. Together, these findings support a critical role of HIF-1 in the fibrosis sensitivity in diabetes.

In this study, we examined the effect of UUO in the in vivo models of 6–8 weeks old STZ-induced diabetic and Akita mice. In these models, the mice only had 3–5 weeks of hyperglycemia, and did not have functional, structural and pathological characteristics of diabetic kidney disease such as proteinuria, renal fibrosis and glomerular pathology(20). Following UUO, both diabetic and no-diabetic mice had collagen deposition and fibrosis marker protein accumulation, which were much more evident in the diabetic group. Consistently, high glucose-incubated renal tubular cells showed more severe fibrotic changes including fibronectin accumulation than normal glucose cells. The results indicate that the fibrosis sensitivity occurs in the early stage of diabetes and is likely related to high glucose or hyperglycemia. We tested STZ treatment and Akita mice, two type 1 diabetes model, but hyperglycemia is also a feature of type 2 diabetes. Therefore, our finding of renal fibrosis sensitivity may extend to type 2 diabetes, although this needs to be verified by further studies.

The blood to the kidneys accounts for almost 20% of the total cardiac output, but the unique anatomy and complex transport functions of the kidneys make them particularly sensitive to hypoxia(21). Accordingly, hypoxia and HIFs represent an early and potentially initiating factor in the pathogenesis of various kidney diseases(15, 22). HIFs mediates hypoxia-induced cellular responses through regulating genes involved in cell metabolism, glucose utilization angiogenesis, oxidative, apoptosis, fibrogenesis(23). A protective role of HIF1 against tissue injury has been documented in various organ systems including the kidney(24–26). Nordquist et al. showed that chronic pharmacological HIF1 activation mitigated diabetes-induced alternations in renal oxygen metabolism and mitochondria function and that prevention of this alternations was accompanied by normalized renal function, reduced proteinuria, and improve tubulointerstitial injury from DKD in a rat model of type 1 diabetes(24). By using global reduction of HIF-1α mice, Bohuslavova et al. demonstrated that HIF-1α deficiency accelerated pathological changes in the early stage of DKD. Six weeks after diabetes-induction, HIF-1α deficiency mice showed more prominent changes in serum parameters associated with glomerular injury, instead of evident fibrosis induction, at least not in the early phase of diabetes(26). On the contrary, several studies have demonstrated an opposite role for HIF1 in mediating kidney injury using chronic kidney models. Enhanced HIF-1α expression was shown in the glomerular and tubular compartment of patients with tubulointerstitial injury in chronic kidneys and diabetes by immunohistochemistry analysis(15). Nayak et al. further demonstrated that blockade of HIF1 by YC-1 led to the decreases in renal hypertrophy, extracellular matrix protein accumulation, oxidative stress, and urinary albumin excretion in the type 1 diabetic animal model of OVE26 mice(27). The results in our present study suggest that HIF1 contributes to renal fibrosis, especially in diabetic kidneys. Therefore, HIF1 may play different roles during the initiation, progression and end-stages of diabetic kidney disease. Specifically, HIF1 may protect against kidney injury at the initial stage of DKD, but at the late stage, it may promote renal fibrosis and the deterioration of renal function.

In our current study, the observation of higher HIF-1 induction in diabetic kidneys during UUO (Figure 4C) is very interesting. Although the mechanism of the increased HIF-1 induction is currently unclear, microvascular dysfunction is an early pathological alteration in diabetes that contributes critically to later development of diabetic complications including diabetic kidney disease. Microvascular dysfunction is expected to lower oxygen delivery and sensitize the tissues to hypoxia and HIF induction. Intriguingly, we also detected higher HIF-1 induction by hypoxia in high glucose-incubated cells than in normal glucose cells (Figure 4A), suggesting that hyperglycemia in vivo and high glucose in vitro may enhance HIF-1 induction directly in kidney cells. Further investigation should delineate the responsible mechanism.

The correlation between apoptosis, inflammation and fibrosis have been established for a long time. Inflammation plays a crucial role in the initiation and progression of renal fibrosis after injury(28, 29). The contribution of macrophages to fibrosis has been well studied in the past years. After a monocyte is recruited to the injury site via cytokines and chemokines, it would differentiate into a macrophage which displays a typical proinflammatory phenotype and produces chemokines and cytokines for further inflammation and kidney damage(30, 31). Johnson and Dipieto showed that apoptosis also had roles in the initiation and propagation of organ fibrosis via directly and indirectly pathways(32). In our present study, Akita mice showed more macrophages by F4/80 staining during 1 week of UUO compared with wild-type mice. But, after 2 weeks of UUO, Akita mice had few macrophages, probably because of the severe injury and extensive myofibroblast expansion in these mice. Indeed, Akita mice had more apoptotic cells during UUO than wild-type mice. These results are consistent with the idea of chronic inflammation and kidney deterioration in renal fibrogenesis.

In conclusion, this study reports the first evidence that diabetes sensitizes kidneys to renal interstitial fibrosis. Such fibrosis sensitivity also exists in high glucose-incubated cells, suggesting hyperglycemia or high glucose is a major factor leading to this sensitivity. Interestingly, these cells and tissues have more HIF-1 induction and blockade of HIF-1 results in the attenuation of the fibrosis sensitivity, indicating a critical role of HIF-1 in mediating the fibrosis sensitivity in diabetes. Therapeutically, it is important for diabetic patients to avoid the potential causes of fibrogenesis, such as kidney injury and nephrotoxins. In addition, pharmacological inhibitors of HIF-1 may be effective in reducing the sensitivity of fibrosis in these patients.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Volker Haase at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine (Nashville, TE), Dr. Ulrich Hopfer at Case Western Reverse University (Cleveland, OH), and Drs. Lieberthal and Schwartz at Boston University (Boston, MA) for generously providing PEPCK-CRE transgenic mice, RPTC line and mouse PT cell (BUMPT-306) line, respectively. This study was supported by grant from National Natural Science Foundation of China (81873595, 81800681) and Shanghai Municipal Key Clinical Specialty (shslczdzk02503). Zheng Dong is a recipient of the Senior Research Career Scientist award from the Department of Veterans Affairs of USA, supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs of USA (1TK6BX005236, I01 BX000319) and the National Institutes of Health of USA (5R01DK058831, 5R01DK087843).

ABBREVIATIONS

- UUO

unilateral ureteral obstruction

- HIF-1 α

hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- DKD

diabetic kidney disease

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- HE

Hematoxylin-eosin

- TUNEL

TdT-mediated dUTP mick-end labeling

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- DM

diabetic mice

- ND

nondiabetic mice

- BUN

blood urea nitrogen

- RPTC

rat kidney proximal tubule cell

Footnotes

DISCLOURES

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and within its supplementary materials published online.

References

- 1.Cho NH, Shaw JE, Karuranga S, Huang Y, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Ohlrogge AW, and Malanda B (2018) IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 138, 271–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes A (2018) Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2017. Diabetes Care 41, 917–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeFronzo RA, Reeves WB, and Awad AS (2021) Pathophysiology of diabetic kidney disease: impact of SGLT2 inhibitors. Nat Rev Nephrol 17, 319–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oshima M, Shimizu M, Yamanouchi M, Toyama T, Hara A, Furuichi K, and Wada T (2021) Trajectories of kidney function in diabetes: a clinicopathological update. Nat Rev Nephrol 17, 740–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanwar YS, Sun L, Xie P, Liu FY, and Chen S (2011) A glimpse of various pathogenetic mechanisms of diabetic nephropathy. Annu Rev Pathol 6, 395–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qi C, Mao X, Zhang Z, and Wu H (2017) Classification and Differential Diagnosis of Diabetic Nephropathy. J Diabetes Res 2017, 8637138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei Q, Liu Y, Liu P, Hao J, Liang M, Mi QS, Chen JK, and Dong Z (2016) MicroRNA-489 Induction by Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 Protects against Ischemic Kidney Injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 27, 2784–2796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peng J, Li X, Zhang D, Chen J-K, Su Y, Smith SB, and Dong Z (2015) Hyperglycemia, p53, and mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis are involved in the susceptibility of diabetic models to ischemic acute kidney injury. Kidney international 87, 137–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Livingston MJ, Ding HF, Huang S, Hill JA, Yin XM, and Dong Z (2016) Persistent activation of autophagy in kidney tubular cells promotes renal interstitial fibrosis during unilateral ureteral obstruction. Autophagy 12, 976–998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mei SQ, Livingston M, Hao JL, Li L, Mei CL, and Dong Z (2016) Autophagy is activated to protect against endotoxic acute kidney injury. Sci Rep-Uk 6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng J, Ramesh G, Sun L, and Dong Z (2011) Impaired Wound Healing in Hypoxic Renal Tubular Cells: Roles of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 and Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 / -Catenin Signaling. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 340, 176–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breyer MD (2004) Mouse Models of Diabetic Nephropathy. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 16, 27–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins DF, Kimura K, Iwano M, and Haase VH (2008) Hypoxia-inducible factor signaling in the development of tissue fibrosis. Cell Cycle 7, 1128–1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugahara M, Tanaka T, and Nangaku M (2020) Hypoxia-Inducible Factor and Oxygen Biology in the Kidney. Kidney360 1, 1021–1031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins DF, Kimura K, Bernhardt WM, Shrimanker N, Akai Y, Hohenstein B, Saito Y, Johnson RS, Kretzler M, Cohen CD, Eckardt KU, Iwano M, and Haase VH (2007) Hypoxia promotes fibrogenesis in vivo via HIF-1 stimulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest 117, 3810–3820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Na JI, Na JY, Choi WY, Lee MC, Park MS, Choi KH, Lee JK, Kim KT, Park JT, and Kim HS (2015) The HIF-1 inhibitor YC-1 decreases reactive astrocyte formation in a rodent ischemia model. Am J Transl Res 7, 751–760 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brownfoot FC, Tong S, Hannan NJ, Hastie R, Cannon P, Tuohey L, and Kaitu’u-Lino TJ (2015) YC-1 reduces placental sFlt-1 and soluble endoglin production and decreases endothelial dysfunction: A possible therapeutic for preeclampsia. Mol Cell Endocrinol 413, 202–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatt K, Wei Q, Pabla N, Dong G, Mi QS, Liang M, Mei C, and Dong Z (2015) MicroRNA-687 Induced by Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 Targets Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog in Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 26, 1588–1596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei Q, Sun H, Song S, Liu Y, Liu P, Livingston MJ, Wang J, Liang M, Mi QS, Huo Y, Nahman NS, Mei C, and Dong Z (2018) MicroRNA-668 represses MTP18 to preserve mitochondrial dynamics in ischemic acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest 128, 5448–5464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma Z, Li L, Livingston MJ, Zhang D, Mi Q, Zhang M, Ding HF, Huo Y, Mei C, and Dong Z (2020) p53/microRNA-214/ULK1 axis impairs renal tubular autophagy in diabetic kidney disease. J Clin Invest 130, 5011–5026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nangaku M (2005) Chronic Hypoxia and Tubulointerstitial Injury: A Final Common Pathway to End-Stage Renal Failure. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 17, 17–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matoba K, Kawanami D, Okada R, Tsukamoto M, Kinoshita J, Ito T, Ishizawa S, Kanazawa Y, Yokota T, Murai N, Matsufuji S, Takahashi-Fujigasaki J, and Utsunomiya K (2013) Rho-kinase inhibition prevents the progression of diabetic nephropathy by downregulating hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Kidney Int 84, 545–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Semenza GL (2012) Hypoxia-inducible factors in physiology and medicine. Cell 148, 399–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nordquist L, Friederich-Persson M, Fasching A, Liss P, Shoji K, Nangaku M, Hansell P, and Palm F (2015) Activation of hypoxia-inducible factors prevents diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 26, 328–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ekberg NR, Eliasson S, Li YW, Zheng X, Chatzidionysiou K, Falhammar H, Gu HF, and Catrina SB (2019) Protective Effect of the HIF-1A Pro582Ser Polymorphism on Severe Diabetic Retinopathy. J Diabetes Res 2019, 2936962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bohuslavova R, Cerychova R, Nepomucka K, and Pavlinkova G (2017) Renal injury is accelerated by global hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha deficiency in a mouse model of STZ-induced diabetes. BMC Endocr Disord 17, 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nayak BK, Shanmugasundaram K, Friedrichs WE, Cavaglierii RC, Patel M, Barnes J, and Block K (2016) HIF-1 Mediates Renal Fibrosis in OVE26 Type 1 Diabetic Mice. Diabetes 65, 1387–1397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duffield JS (2010) Macrophages and immunologic inflammation of the kidney. Semin Nephrol 30, 234–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meng XM, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, and Lan HY (2014) Inflammatory processes in renal fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol 10, 493–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ricardo SD, van Goor H, and Eddy AA (2008) Macrophage diversity in renal injury and repair. J Clin Invest 118, 3522–3530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gutierrez OM, Shlipak MG, Katz R, Waikar SS, Greenberg JH, Schrauben SJ, Coca S, Parikh CR, Vasan RS, Feldman HI, Kimmel PL, Cushman M, Bonventre JV, Sarnak MJ, and Ix JH (2021) Associations of Plasma Biomarkers of Inflammation, Fibrosis, and Kidney Tubular Injury With Progression of Diabetic Kidney Disease: A Cohort Study. Am J Kidney Dis [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson A, and DiPietro LA (2013) Apoptosis and angiogenesis: an evolving mechanism for fibrosis. Faseb j 27, 3893–3901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and within its supplementary materials published online.