Abstract

Background: Effective leadership is critical for the performance of health care teams and their intended outcomes for patient care. Given that team leadership is a modifiable and teachable skill, there is a need for a better understanding of this multidimensional behavior to inform future leadership training for health care action (HCA) teams. This systematized review identifies reported observed leadership behaviors in HCA teams, defined as interdisciplinary teams which complete vital tasks in complex, time-pressured, and dynamic situations.

Methods: We searched CINAHL, MEDLINE, Scopus, PsycINFO, and Web of Science for peer-reviewed, English language articles using single and combinations of keywords including leadership, health care action team, and teamwork, individually. We included articles published until June 2021 without any specific beginning date.

Results: From 242 records, 13 articles were included in the review. We categorized our findings of team leadership behaviors in HCAs based on an existing framework of three dimensions: transition processes, action processes, and interpersonal skills. The most-reported behaviors for transition processes were encouraging team members’ input, (re)assessing the team’s situation, and confirming team members’ understandings. The action processes dimension consisted of behaviors that included monitoring the progress of the patient, managing resources, asking for help when needed, coaching/supervising, and assisting team members as needed. Finally, closed-loop communication and facilitating team members speaking up behaviors were categorized as interpersonal skills.

Conclusion: Although team leadership has been an area of focus in the field of health professions education, little attention has been paid to identifying the observable behaviors of effective team leaders in an HCA team. The study identified several new essential team leadership behaviors that had not been previously described, including seeking feedback, shared decision making, and aspects of interpersonal communication. The findings can inform educators in planning and implementing strategies to enhance HCA team leadership training, with the ultimate potential to improve health care.

Keywords: Leadership, Health Care Action Team, Teamwork, Team Leader, Leader Skills

Introduction

↑What is “already known” in this topic:

There is a growing knowledge that team leadership is a core competence for health professionals. Prior research has tried to identify team leadership behaviors in health care action teams, yet none of them was comprehensive.

→What this article adds:

This systematized review presented a list of specific leadership behaviors for health care action teams within a framework of dimensions and sub-dimensions, with the intention of informing the development, implementation, and assessment of training interventions.

Leadership has been demonstrated as an important factor for team success (1-4) and has been identified as a critical role for effective Health Care Act ion (HCA) teams (5). HCA teams are described as interdisciplinary teams which are generally supervised by a senior or junior doctor in complex, time-pressured, and dynamic situations to complete vital tasks (6). An illustrative example is the management of a trauma casualty who arrives in the emergency department in severe distress and impending cardiac arrest. In this situation, a group of skilled providers from different disciplines has to coordinate their actions to successfully manage the vital task. HCA teams with an effective team leader have more effective coordination of actions with enhanced team performance and communication, fewer adverse events, and improved outcomes for patients (7-9).

Medical regulatory bodies recognize team leadership as a core competence for medical learners (8-10). The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) expects junior doctors to work efficiently as a leader in teams as part of its six areas of core competencies (11). The CanMEDS competency framework includes the development and application of leadership skills (12). An essential aspect of developing training for addressing these required competencies is to define team leadership behaviors, especially in HCA teams in which leadership is critical, with the intention to ensure that these behaviors are included in any training curricula (13). A systematic review of studies that reported the use of assessment tools for HCA teams leadership until 2012 was conducted by Rosenman et al. (2015) (14). This review identified leadership behaviors, and they proposed a framework for team leadership behaviors by refining previous frameworks. The framework had three dimensions: transition processes, action processes, and interpersonal skills. The transition processes were defined as a period of time in which the team focuses on team structure, teamwork planning, and evaluation of the team performance to achieve its ultimate goal. The action processes included patient monitoring, system monitoring, backup behavior, and coordination which are part of the team's performance to strive towards accomplishing its goals. Interpersonal skills included conflict management, affect management, empowering and communication for management of the transition and action processes.

The aim of this systematized review was to identify the reported observed leadership behaviors in HCA teams in the published literature. Our intention for conducting this review was to inform future team leadership training for HCA teams, with potential impact on HCA team performance and patient care.

Methods

We performed a systematized review by using keywords (leadership, health care action team, teamwork, team leader, leader skills), both single and in combination, to search CINAHL, MEDLINE, Scopus, PsycINFO, and Web of Science for peer-reviewed English language articles published until June 2021, without any specific beginning date (Appendix 1).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria: English language studies that identified team leadership behaviors in HCA teams with the leadership of senior or junior doctors in a hospital or simulated setting were included. Studies that focused on both team leadership behaviors and attributes were initially included, but attributes were not analyzed. Our rationale for not analyzing leadership attributes is that they are not observable. An “attribute” is part of what the leader “is”, whereas “behavior” is part of what the leader “does” (4). Leadership behaviors are directly observable and are determined by attributes. We excluded studies if (1) they were review articles or meta-analyses or book chapters, (2) the main focus of the study was not team leadership in HCA teams, and (3) they were presented as methods of leadership training.

Study selection: The retrieved articles were entered into EndNote software and checked for duplicates. The first author (NSHR) read all the titles and abstracts of the articles and checked them against the inclusion criteria. The full text of the remaining articles was reviewed for the eligibility criteria. The whole process of searching and selecting the articles was conducted throughout with open discussions with RG and MJ. We did not include grey literature in the search.

Data analysis: We summarized the data of the included studies into three categories: (1) study characteristics (Author’s name, publication year, study design, and the number of institutions (2) participants (number, type of participation, number and type of participated teams, profession, medical specialty); and (3) leadership behaviors. The first author (NSHR) initially read a sample of articles and extracted the team leadership behaviors described in the article. The extracted behaviors were checked with RG, and disagreements were discussed to reach a consensus. Then, all selected articles were checked for data extraction by NSHR. Following extraction, leadership behaviors with similar meanings which were described in the different articles were identified, and each behavior was labeled with one behavior that best described the behavior. The frequency of each labeled behavior was determined and the labeled behaviors were deductively assigned to the dimensions and sub-dimensions using Rosenman et al. (2015) team leadership framework (14). The process of data analysis was checked by RG, MJ and JS, with a discussion about differences to reach a consensus.

Results

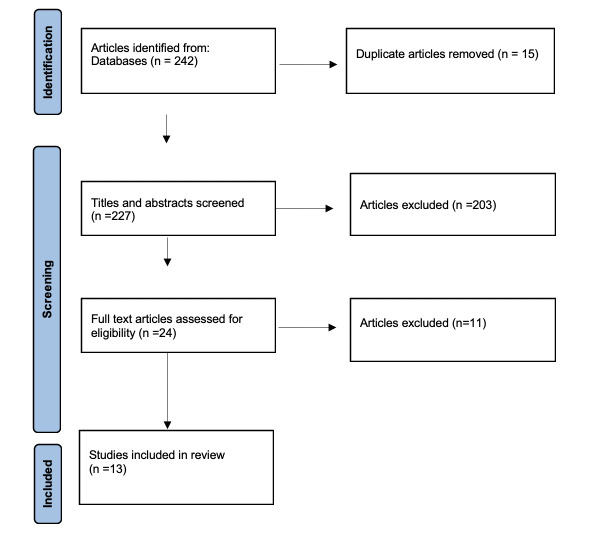

Out of 242 articles, 15 duplicated papers were excluded. After evaluating titles and abstracts, 24 papers remained in which their full text was assessed. A total of 13 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included for further analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the literature selection process for the present article

The detailed overview of each article is described in Table 1. The articles were published between 2003 to 2020. Of 13 articles, 5 were quantitative (6,16-19), 2 used a qualitative approach (20,21), and 6 employed a combination of both quantitative and qualitative methods (7,8,15,22-24). Interviews were conducted in 5 studies for data gathering; 2 of them used critical incidents interviews (20,23). Questionnaires were used in 3 mixed-method studies (8,15,22), and 1 quantitative study (16). Other methods (Delphi and focus group) were used in 2 studies (7,24). Studies identified leadership behaviors in different HCA teams, including surgical (5 studies) (6,15,17,21,24), pediatric emergency (2 studies) (7,16), trauma (3 studies) (8,23), anesthesia (1 study) (18), clinical (1 study) (22) and ICU (1 study) (20). A total of 10 studies performed psychometric analysis of the assessment tools and five studies employed a theoretical framework.

Table 1. Characteristics of 13 studies included in the present article .

| First author | Study design | Number of institutions | Number of participants and Type of participation |

Number and type of teams participated |

| Fernandez 2020 |

Quantitative | 1 | 79 second- and third-year emergency medicine and general surgical residents at the University of Washington Trauma resuscitations were video recorded and coded using outcome measures. |

1 trauma team at the University of Washington |

| MO 2019 |

Mixed | 1 | Phase 1. Quantitative: 21 members from trauma team were interviewed Phase 2. Quantitative: 64 members from trauma team completed DCE (Discrete Choice Experiment) questionnaire Trauma team included physicians (resident, fellow, or attending), nurses, x-ray technologists, respiratory therapists, etc. |

1 Pediatric trauma team |

| Oza 2018 |

Mixed | 2 | Phase 1. Developing LOFT (Leadership Observation Feedback Tool): Internal medicine and pediatric residents were surveyed (20), completed a Delphi questionnaire (15) and participated in a pilot study (78). Phase 2. LOFT testing: 377 team members (attending physicians, fellows, and residents, nurses, pharmacists, medical students, and allied health professionals) completed LOFT for 95 residents. |

5 Clinical teams |

| Stone 2017 |

Mixed | 1 | 7 surgeons and 82 non-surgeons (phase 1) and 5 surgeons and 105 non-surgeons (phase 2) were surveyed to measure surgical staff member perceptions and attitudes about themselves, their teams, and team dynamics. -Cases involving 7surgeons (phase1) and 4 surgeons (phase2) were observed to collect data about interactions between surgeons and non-surgeons during individual surgical procedures. - 7 surgeons and 116 team members were interviewed to gain insights on contextual influences underlying observed interactions Non-surgeons included scrub technicians/nurses, circulating nurses, physician assistants, perfusionists, anesthesiologists, and trainees (e.g. surgical fellows, anesthesia residents. |

Number not stated Surgical teams |

| Leenstra 2016 | Mixed | 3 | 28 participants including 5 surgeons, 3 surgical residents, 8 emergency physicians, 1 resident emergency physician, 1 anesthesiologist, 2 anesthesiology residents and 8 emergency nurses, were interviewed (critical incident type). | Number not stated

Trauma teams |

| Coolen 2015 |

Quantitative | 1 | 12 pediatric residents participated in 48 team simulations of a pediatric critical-care event. 38 residents were surveyed to assess the specific needs in leadership training as felt by them. |

Number not stated Pediatric emergency teams |

| Parker 2014 |

Quantitative | 3 | Videos of 29 operations from Surgical teams (surgeons, surgical residents, nurses, anesthesiologists were analyzed. | Number not stated Surgical teams |

| Parker 2013 |

Mixed | 1 | Phase 1. Qualitative: 106 participants, including surgeons, trainees, anesthetists, nurses participated in 10 focus groups. Phase 2. Testing taxonomy: 2 psychologists rated 5 videos of live surgery. |

1 Operating room team |

| Grant 2012 |

Mixed | 5 | Phase 1.8 pediatric acute care physician educators (3 from emergency medicine, 4 from critical care, and one practicing in both subspecialties) from five pediatric tertiary care hospitals in Canada participated in a Delphi method to develop pediatric resuscitation team leader evaluation tool as members of an Expert Working Group (EWG). Phase 2. 30 residents on two videotaped scenarios were assessed by 4 pediatricians using pediatric resuscitation team leader evaluation tool for Instrument psychometric testing. |

Number not stated Pediatric resuscitation team |

| Parker 2012 |

Quantitative | 3 | 20 surgeons Observed at 29 surgery Participants included consultant surgeons, surgical trainees, circulating nurses, scrub nurses, and anesthetists |

22 Surgical teams |

| Reader 2011 |

Qualitative | 7 | 25 senior ICU physicians were interviewed (critical incident technique). | Number not stated ICU teams |

| Künzle 2010 |

Quantitative | 1 | 26 residents and nurses videotaped during simulated anesthesia inductions. Videotapes were analyzed using the software ATLAS ti. | 12 Anesthesia teams |

| Edmondson 2003 |

Qualitative |

16 | 165 members from 16 Operating Room teams (Surgeons, Anesthesiologists, OR nurses perfusionists, Cardiologists, intensive care unit (ICU) nurses, general care unit (or floor) nurses, senior hospital agents), were interviewed. |

16 Operating Room teams |

Team leadership behaviors were categorized into three dimensions: transition processes, action processes, and interpersonal skills (Appendix 1). Tables 2, 3, and 4 show the behaviors in each dimension. For the transition phase, sub-dimensions were mission analysis, goal specification, strategy formulation, and reflection. Patient monitoring, system monitoring, team monitoring, and activity coordination were the sub-dimensions of action processes. Sub-dimensions of behaviors related to conflict management, affect management, motivation, and communication were included in the dimension of interpersonal skills.

Table 2. Leadership behaviors related to transition processes for health care action .

| Transition processes sub dimensions | Team leadership behaviors | Relevant studies |

| Mission analysis | 1.Team leader encourages team members for input (n=5) 2.Team leader integrates team members’ suggestions (n=1) 3. Team leader holds the team notified of plans and changes to stabilize a shared mental model (n=1) 4. Team leader fortifies team members’ understanding (n=2) 5.Team leader (re) assesses the situation (n=3) 6.Team leader briefs the team (n=2) |

Fernandez 2020 (19), MO 2019 (8), Oza 2018 (22), Leenstra 2016 (23), Parker 2013 (24), Parker 2012 (6), Grant 2012 (7), Reader 2011 (20) |

| Goal specification | 1.Team leader assigns tasks/delegates roles (n=7) 2. Team leader introduces expectations and goals for team/Promotes mutual goal-setting (n=5) 3. Team leader applies established guidelines/protocols to meet standards (n=4) |

Fernandez 2020 (19), MO 2019 (8), Oza 2018 (22), Stone 2017 (15), Coolen 2015(16), Parker 2014 (17), Parker 2013 (24) Parker 2012(6), Grant 2012 (7), Reader 2011 (20), Künzle 2010 (18) |

| Strategy formulation |

1. Team leader plans for whatever to do. (n=3) 2. Team leader plans/decides how to do things (n=3) 3. Team leader presents strategy/creates a new plan regarding patient status (n=3) 4. Team leader thinks ahead/builds contingency plans (n=1) 5.Team leader presents direction/uses command statements/makes firm decisions (n=2) 6. Team leader assures collaboration with team members for shared decision-making (n=7) 7. Team leader plans and prioritizes care monitoring actions(n=3) |

Fernandez 2020 (19), MO 2019 (8), Leenstra 2016 (23), Coolen 2015 (16), Parker 2014 (17), Parker 2013 (24), Parker 2012 (6), Reader 2011 (20), Oza 2018 (22), Künzle 2010 (18) |

| Reflection |

1.Team leader debriefs the team/ Ensures that expectations and goals are achieved (n=4) 2. Team leader provides specific/positive, and constructive feedback/criticism frequently (n=6) 3.Team leader identifies areas for team improvement (n=1) 4. Team leader provides encouragement (n=4) 5. Team leader receives feedback (n=1) |

MO 2019 (8), Oza 2018 (22), Leenstra 2016 (23), Reader 2011(20), Stone 2017 (15), Parker 2012 (6), Parker 2013 (24) |

Table 3. Leadership behaviors related to action processes for health care action teams .

| Action processes sub dimensions | Team leadership behaviors | Relevant studies |

| Patient monitoring | 1- Team leader connects with patients (n=3) 2.Team leader monitors the progress of patient/notes when the patient is not responding as expected (n=5) 3. Team leader notices unpredictable, relevant changes in patient condition (n=5) |

Oza 2018 (22), Leenstra 2016 (23), Coolen 2015 (16), Grant 2012 (7), Reader 2011 (20) |

| Systems monitoring | 1.Team leader requests for help when required (n=5) 2. Team leader notices a change in the system/team environment (n=3) 3. Team leader facilitates team problem solving (n=4) 4. Team leader remains hands-off/maintains a big picture view (1) 5. Team leader involves in time management for tasks (n=3) 6. Team leader manages resource utilization (n=6) 7. Team leader manages team progression towards goals (n=5) 8. Team leader frequently reminds others of goals/ expectations (n=1) |

Oza 2018 (22), stone (2017), Leenstra 2016 (23), Coolen 2015 (16), Parker 2014 (17), Parker 2013 (24), Parker 2012 (6), Grant 2012 (7), Reader 2011 (20), Künzle 2010 (18) |

| Team monitoring/backup behavior |

1. Team leader Identifies errors (n=4) 2. Team leader manages team members’ workload/Distributes work appropriately and fairly based on skill level (n=2) 3. Team leader assists team members as needed, particularly at busy times/establish mutual support with them (n=5) 4.Team leader coaches/provides supervision as needed (n=5) 5. Team leader places an emphasis on teaching and learning (n=2) |

Leenstra 2016 (23), Coolen 2015 (16), Parker 2013 (24), Parker 2012 (6), Grant 2012 (7), Reader 2011 (20), Edmondson 2003 (21) |

| Coordination |

|

Leenstra 2016 (23), Reader 2011 (20) |

Table 4. Leadership behaviors related to interpersonal skill for health care action teams .

| Interpersonal skills sub-dimensions | Team leadership behaviors | Relevant studies |

| Conflict management | 1. Team leader assists with conflict management/resolution (n=2) | Coolen 2015 (16), Reader 2011 (20) |

| Affect management | 1. Team leader is available and approachable/has a positive attitude, even during difficult times (n=1) 2. Team leader treats all team members with respect/ trustworthy and ethical (n=2) 3. Team leader remains calm/copes with pressure and stress/manages noise distraction(n=2) 4. Team leader takes the initiative (n=1) 5. Team leader has a sense of constructive humor (n=1) |

Oza 2018 (22), Parker 2014 (17), Parker 2013 (24), Reader 2011 (20), Stone 2017 (15), Coolen 2015 (16) |

| Motivation/empowering | 1. Team leader motivates and empowers team members (n=2) 2.Team leader is confident in other team members’ work (n=1) 3.Team leader models dedication to and passion for high-quality patient care (n=2) 4.Team leader thanks team members for their work/ Gives praise for work well done/ Acknowledges/Highlights successes and accomplishments (n=1) |

Oza 2018 (22), Edmondson 2003 (21), Reader 2011 (20) |

| Communication | 1. Team leader facilitates speaking up (n=3) 2.Team leader listens carefully to others (n=1) 3.Team leader communicates clearly/uses closed-loop communication (n=10) 4. Team leader facilitates team engagement (n=1) |

MO 2019 (8), Oza 2018 (22), Leenstra 2016 (23), Coolen 2015 (16), Parker 2014 (17), Parker 2013 (24), Parker 2012 (6), Grant 2012 (7), Reader 2011 (20), Edmondson 2003 (21) |

Discussion

Although the leadership by doctors is a crucial component of high-performing HCA teams, identifying the relevant, effective leadership behaviors remains a challenge. We found 13 papers reporting the key leadership behaviors of senior and junior doctors as team leaders for the HCA team and then categorized these behaviors into sub-dimensions using a predetermined framework with the dimensions transition processes, action processes, and interpersonal skills.

We extended Rosenman’s review (2015) (14) by reviewing articles published until June 2021, and we also identified several new leadership behaviors that were not described in this review.

Transition processes: Team leadership behaviors in the transition phase were categorized in 4 sub-dimensions, including mission analysis, goal specification, strategy formulation, and reflection. Most team leadership behaviors related to mission analysis were encouraging team members’ input (6-8,19,21,24), (re)assessing the teams’ situation (6,7,20), and confirming team members’ understandings (23,24). The most common goal specification behaviors were assigning tasks/delegating roles (7,8,18-20,24), and setting expectations and goals for the team (6,16,20,22,24). Collaborating with team members for shared decision-making (6,8,18,20,22-24), providing strategy/creating a new plan in response to changes in patient condition (20,23,24), and planning and prioritizing care monitoring actions (8,19,20,23), were the most common behaviors to formulate a strategy. Finally, the most common reflection behaviors were encouragement (6,15,20,22,24), and providing constructive, positive and, specific feedback (8,20,22,23). Our review showed that the main leadership behaviors of doctors were in transition processes and this was also found in the review of healthcare teams by Dinh et al. (25). They found that of all disciplines in healthcare the medical sub-disciplines fields, including emergency, surgery, anesthesia and obstetric teams, were more focused on transition processes (25). We found two behaviors including “Team leader receives feedback” and “Team leader ensures collaboration with team members for shared decision-making,” that were not included in Rosenman et al.’s review (2015). These findings are in line with the emerging emphasis on the importance of feedback-seeking behavior and shared decision-making in healthcare teams (26,27).

Action processes: Important team leadership sub-dimensions in the action process dimension were patient monitoring, system monitoring, team monitoring, and coordination. Monitoring the progress of the patient and for unexpected changes in the patient’s condition were common behaviors in the patient monitoring dimension (7,16,20,22,23). Managing resources (6,7,17-20,24), and asking for help when needed (6,7,20,22,24), were the most important behaviors in the system monitoring dimension. The monitoring team dimension also included coaching/supervising (6,16,23), and assisting team members as needed (6,16,23) as the most reported behaviors. Consistent with our findings, monitoring behaviors have also been highly reported in several studies of teamwork in emergency surgery (28,29).

Another notable finding for action processes was that important components of team leadership, such as the coordination sub-dimension, included few behaviors. One reason could be that the sub-dimensions of action processes may be difficult to translate into specific behaviors since it is challenging to observe action process–based behaviors during complex, time-pressured, and dynamic real encounters of HCA teams, where completing the vital tasks are at stake. Further research is suggested to analyze team leadership literature using the input–mediator–output–input (IMOI) heuristic that has been previously applied in teamwork studies in health care (30). This adaptive model recognizes mediational factors (processes and emergent states) that transform inputs to outputs. The emergent cognitive, behavioral or affective states (e.g., team efficacy, team potency, team empowerment, cohesion and trust) of a team are particularly influenced by the progression of the team over time. This model shows the broader range of crucial mediational effects that can explain variability in team performance. Utilizing this model may extend our understanding of team performance by revealing more mediational factors for effective team leadership. This model could also be included in interventions for team leadership training for HCA teams, with the intention to support leadership in dynamic situations.

Interpersonal skill dimension: Several sub-dimensions, such as conflict management, affect management, motivation, and communication, were considered as interpersonal skills. The most common interpersonal behaviors were closed-loop communication (6-8,16,20-24), which describes a team's ability to deliver, receive, and understand information. HCA team leaders employ closed-loop communication to make clear communication between team members and to reduce preventable errors. We have identified more behaviors in the interpersonal skills domain than have been described in the previous review by Rosenman et al. (14), which suggests that recent studies on team leadership in HCA have increased their focus on behaviors in this domain.

Study Limitations

This study has several potential limitations. We used a limited number of search terms and databases in our systematic searchthat were limited to articles published in English. However, we adopted an explicit search strategy of the main relevant databases. We found a diversity in the analysis of the procedures and results in the reviewed articles but we tried to overcome this potential limitation by a wider reading of the relevant literature and by increasing our familiarization with the various terms and by discussing the initial coding and labeling between the reviewers to reach consensus. Although the quality assessment of articles may strengthen our findings, due to the small number of articles included in this systematized review, we preferred to maintain all articles and did not perform the quality assessment of articles. Based on Grant's study (2009) on the typology of review studies, systematized reviews may or may not include quality assessment of included articles (31).

Conclusion

This review has identified a list of specific leadership behaviors for HCA teams within a framework of dimensions and sub-dimension, with the intention of informing the development and implementation of training interventions to enhance the effectiveness of HCA teams, and ultimately to improve health care. We extended the list of leadership behaviors described in a previous review by identifying several new behaviors that are increasingly recognized as essential for effective teamwork and clinical care, including seeking feedback, shared decision-making and aspects of inter-personal communication. These leadership behaviors should be included in future training for HCA teams. Further research is suggested to operationalize more action phase processes within HCA teams using more comprehensive underlying theories and to define effective leadership dimensions and behaviors across HCA teams to support patient safety as the ultimate goal.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tehran University of Medical Sciences for supporting this paper in part fulfillment of a PhD thesis.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board of Tehran University of medical sciences approved the study (IR.TUMS.IKHC.REC.1397.152).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix

Appendix 1. Search Strategy Used in a Systematized Review to Identify Research Describing Team Leadership behaviors in Health Care Action Teams

PubMed search strategy:

("Leadership"[MH] OR leadership [tiab] OR team leader [tiab] OR "team leader behaviors"[tiab] OR

""[tiab] OR "leader skills"[tiab]) AND ("Health Care teams"[Mesh] OR

"Outcome Assessment (Health Care)"[MH] OR assessment [tiab] OR assess [tiab] OR

Performance [tiab] OR evaluation [tiab] OR evaluate [tiab] OR evaluated [tiab] OR validity [tiab] OR

Validation [tiab] OR measure [tiab] OR measurement [tiab] OR "leadership assessment"[mh] OR

(leadership status"[MeSH Terms] OR "leadership styles"[MeSH Terms])

OR "leadership development"[tiab]) AND ("Health

Personnel"[Mesh] OR "Faculty"[Mesh] OR "Emergency Responders"[Mesh] OR "Students, Health

Occupations"[Mesh] OR residents [tiab] OR "Internship and Residency"[mh] OR "care teams"[tiab]

OR "Patient Care Team"[mh] OR "Hospital Rapid Response Team"[mh] OR "Students,

Medical"[mh]) OR “interdisciplinary teams” AND English [lang] AND Journal Article.

PyscINFO search strategy:

(DE "Leadership" OR DE "Leadership behaviors" OR DE "Leadership Style" OR DE

"health care Leadership" OR "team leader" OR teamwork) AND ((DE "Measurement"

OR DE "Achievement Measures" OR DE "team leader Measures" OR DE "leadership Measurement"

) OR (DE "Competence" OR DE "Professional Competence") OR (DE

"Evaluation" OR DE "teamwork Evaluation" OR DE "team Evaluation") OR (DE "Training"))

AND ((((DE "Health Personnel" OR DE "Allied Health Personnel" OR DE "Medical Personnel"

OR DE "Mental Health Personnel") OR (DE "Medical Students")) OR (DE "Medical Internship"))

OR (DE "Medical Education") OR "care teams”)

Web of Science search strategy:

Topic= (teamwork OR leadership OR "team leader") AND Topic= ("care providers" OR residents

OR students * OR physician* OR team OR teams OR faculty) AND Topic= (team leader behaviors OR competence OR evaluation OR metrics OR outcome OR validation OR evaluated)

Timespan=2003-2021

Categorization of team leadership behaviors into three dimensions for each article separately .

| Author | Transition processes | Action processes | Interpersonal skills |

|

Fernandez 2020 (2) |

Establishing the leadership role Sharing information and interpreting data Planning and prioritizing tasks Assigning roles Assessing team members’ skills Seeking input Identifying task barriers |

||

| MO 2019 (8) |

Levels of Collaboration: -Actively involves input from team -Sometimes involves input from team -Dismissive of differing opinions Levels of Protocol: -Strict on protocols/standards -Deviates from protocols with team’s feedback -Deviates from protocols under own discretion Levels of Organization: - Delegates and prioritizes tasks; multiple tasks occur simultaneously -Capable of delegation; tasks occur sequentially -Does not clearly delegate or prioritize patient needs Levels of Decisiveness: -Capable of making decisions with expert guidance -Decisive, based on available information -Often indecisive |

Levels of Communication: - Clear, closed-loop communication -Concise communication, at times closed-loop -Hesitant and unclear communication |

|

| Oza 2018 (22) |

- Provides specific and constructive feedback, identifies areas for improvement - Provides positive feedback and encouragement - Gives feedback frequently - Creates an environment in which team members can discuss and learn from mistakes - Sets clear expectations and goals at the beginning -Frequently reminds others of goals/ expectations -Ensures that expectations and goals are achieved |

- Checks in with team members frequently - Ensures collaboration with team members for shared decision-making - Promotes mutual goal-setting and shared decision-making -Distributes work appropriately and fairly based on skill level -Helps with any tasks, particularly at busy times - Incorporates individual learning needs when delegating tasks. -Faces challenges through application of problem-solving skills. - Places an emphasis on teaching and learning |

- Shows appreciation to motivate team - Thanks team members for their work - Gives praise for work well done - Acknowledges/highlights successes and accomplishments - Does things for the team to show appreciation (e.g., brings food) - Listens carefully to others - Communicates directly and clearly with all team members - Is available and approachable - Is confident in other team members’ work - Has a positive attitude, even during difficult time -ability to be assertive -Stays calm in stressful situations - Models how to treat others (respectful to staff and patients, caring toward patients) - Models dedication to and passion for high- quality patient care |

|

Stone 2017 (15) |

-Elucidator (24%):4 positive behaviors (teaching, constructive criticism, explanation, and relevance giving) 2 negative behaviors (private criticism and negative criticism) - Safe space maker (15%): 3 positive behaviors (non-surgeon) initiated concern, questioning, and information sharing. |

- Conductor (9%): 4 positive behaviors (returning the team members to focus, anticipating concerns, mapping steps, and closing loops for confirmation) 1 negative behavior (the need for non-surgeons to seek clarification) - Delegator (15%): help-seeking (positive) or requesting (neutral) |

-Engagement facilitator (15%): 6 positive behaviors (collaboration, consultation, helping /supporting, apology, thanks, and inquiry) - Tone setter (20%): 4 positive behaviors (constructive humor, compliments, reassurance, and encouragement) 2 negative behaviors (frustration and destructive humor) 1 neutral behavior (conversation unrelated to the case) |

| Leenstra 2016 (23) |

Briefing IC: Exchanging prehospital information (Information coordination) DM: Discussing strategy and tasks (Decision making) AC: Discussing preparations (Action coordination) CTD: Setting positive team climate (Coaching and team development) Debriefing IC: Exchanging perceptions and understanding AC: Organizing debriefing Presiding debriefing CTD: Evaluating performance Discussing team climate issues Providing/receiving feedback |

patient handling IC: Collecting patient information Discussing findings/ assessment Communicating findings/ assessment DM: Considering options Selecting and communicating option Reviewing decisions AC: Planning and prioritizing care monitoring actions/protocol adherence Updating about progress Providing action/correction instructions Anticipating/responding members’ task needs CM: Handling communication environment Applying communication standards Structuring discussions CTD: Recognizing limits of own competence Supporting/coaching/ educating others Stimulating concern reporting/speaking up Stimulating positive cooperative atmosphere Managing workload Transfer to follow-up care IC: Presenting case assessment and rationale Highlighting concerns DM: Discussing admission to follow-up care AC: Coordinating continuity of care during handover Exchanging thoughts for care plan Handover IC: Collecting patient information as central contact Checking for differences in prehospital information and handover DM: Confirming initial plans at end of handover AC: Coordinating continuity of care during handover CM: Handling handover communication environment |

|

| Coolen 2015 (16) |

- Actively rewards and compliments coworkers (Supporting style) - Is not open for ideas of coworkers (Delegating style) – Is goal oriented (Directive style) |

Supporting style: – Is focused on coworkers, invests in relationships (Supporting style) – Wants coworkers to excel in their work (Supporting style) – Does not lean on hierarchical structures (Supporting style) - Creates possibilities for innovation and coworker initiative (Supporting style) – Actively coaches coworkers (Supporting style) – Simulates collaboration between coworkers (Supporting style) - Is not focused on task execution (Delegating style) – Transfers responsibilities to coworkers (Delegating style) - Monitors general procedures (Delegating style) – Does not focus on detail (Delegating style) - Keeps distant from coworkers (Delegating style) – Functions as a hatch for facts and figures (Delegating style) - Actively tries to diminish hierarchical differences between leader and coworkers (Coaching style) – Stimulates involvement of coworkers (Coaching style) – Invests in commitment of all coworkers (Coaching style) Actively tries to diminish hierarchical differences between leader and coworkers (Coaching style) – Stimulates involvement of coworkers (Coaching style) – Invests in commitment of all coworkers (Coaching style) –Sstimulates entire team to contribute to decision making (Coaching style) – Invites coworkers to participate in discussion (Coaching style) – Stimulates entire team to contribute to decision making (Coaching style) – Is focused on task execution (Directive style) – Is proactive, and controlling (Directive style) – Is engaged with the patient (Directive style) |

– Is reluctant to take initiative (Supporting style) – Is passive and reactive rather than proactive (Supporting style) – Is not focused on relation with coworkers (Delegating style) – Is reluctant to change (Delegating style) – Is dominant with high level of confidence (Directive style) – Takes initiative (Directive style) - Is dynamic and ambitious (Directive style) – Is cost-conscious (Directive style) - Will not recede from conflicts (Coaching style) – Invests in two-way communication (Coaching style) |

| Parker 2012, 2013, 2014 (6,24,17) |

Making decisions: -Seeking out appropriate information and generating alternative possibilities or courses of action - Synthesizing the information choosing a solution to a problem, and letting all relevant personnel know the chosen option - Making an informed prompt judgment on the basis of information, clinical situation, and risk and continually - Reviewing its suitability in light of changes in the patient’s condition Directing Appropriately to team members, and ensuring the team has what it needs to accomplish the task - Clearly stating expectations regarding accomplishment of task goals; giving clear instructions; using authority where required - Demonstrating confidence in both leadership and technical Maintaining standards: - Supporting safety and quality by adhering to acceptable principles of surgery - Following codes of good clinical practice, and enforcing theater procedures and protocols by consistently demonstrating appropriate behaviors (i.e. asking for help ability) |

Supporting others: - Judging the capabilities of team members - Offering assistance where appropriate - Establishing a rapport with team members and actively encouraging them to speak up Training: - Instructing and coaching team members according to goals of the task - Modifying own behavior according to team’s educational needs -Identifying and maximizing educational opportunities Managing resources: - Assigning resources (people and equipment) depending on the situation or context - Delegating tasks appropriately to team members, and ensuring the team has what it needs to accomplish the task |

Communicating: - Rapport with team members and actively encouraging them to speak up - Giving and receiving information in a timely manner to aid establishment of a shared understanding among team members - Speaking appropriately for the situation - Asking for input from team members |

| Grant 2012 (7) |

- Clearly identifies he/she will lead the resuscitation - Verbalizes thoughts and summarizes progress periodically for benefit of the team - Shows anticipation of future events by asking for preparation of equipment or medication not yet needed - Asks for and acknowledges input from team - Reassesses and reevaluates situation frequently |

- Obtains preliminary history quickly or designates other to do so - Obtains full set cardiorespiratory monitoring and full set of vitals promptly - Obtains assessment of airway patency and protection - Obtains assessment of breathing - Asks for initiation of appropriate initial breathing support and ensures effectiveness - Identifies need for and obtains appropriate airway intervention as required - Ensures adequacy of airway and breathing after each intervention - Asks for assessment of pulses and perfusion - Asks for initiation of chest compressions when appropriate and ensures adequacy of compressions ensures timely appropriate vascular access - Verbally identifies cardiac rhythm on monitor and reassesses rhythm and pulse appropriately after each intervention - Chooses interventions according to appropriate PALS algorithm - Orders appropriate investigations - Asks for assessment of neurological status or secondary survey once - Stabilization of ABC’s complete - Maintains control of leading the resuscitation - Manages team resources appropriately among team members - Avoids fixation errors - Refrains if possible, from active participation - Asks for appropriate help early and shows awareness of own limitations |

- Uses effective closed loop communication |

| Reader 2011 (20) |

Information gathering )Unit Assessment): -Status/condition of new patients is assessed on arrival at the intensive care unit -Expected changes in status of existing patients are confirmed -Patients for potential discharge from intensive care unit are identified -Patient information sources (e.g., charts, x-rays, blood tests, drug charts) are reviewed in-depth with multidisciplinary team - Information on patient progression is gleaned from nursing/medical staff (e.g., drugs, feeding, sedation, discussions with family) - Future information (e.g., computed tomography scan) or resource (materials, expertise) requirements/ gaps are identified with team and tasked accordingly Managing Team Members (Unit Assessment) - Staff rotation is checked and new trainee doctors are met during initial tour - The skills, knowledge, and experience levels of new trainee doctors are considered (e.g., through informal discussion, stage of training) - Contributions to the patient care plans are invited from team members, and questions are invited on previously unseen illnesses/treatments - Dependent on workload/team, junior trainees are asked to present cases, nurses are asked to discuss patient care, and senior trainees are asked to lead on care plans - Tasks and responsibilities are delegated with instructions tailored to trainee physician skills, knowledge, experience, and training needs - Team members are asked to verbally confirm their specific duties and responsibilities for each patient before next patient is reviewed - Team satisfaction with patient care plan is checked Developing a Shared Perspective with the ICU Team: -A unified message on the unit’s goals and expectations of staff is reached between senior physicians - Protocols and guidelines are kept up to-date, are evidence-based, reflect operational realities, and are shared with all team members - Inconsistencies with other senior physicians on patient management strategies are avoided - Specific goals for the ICU are developed (e.g., on patient safety, sedation, feeding) Broader targets for the ICU are developed (e.g., lowest standard ICU mortality rates in regional area) - Unit successes are promoted in terms of patient care quality, safety data, goal attainment, and research - Trainees are provided with a broader vision on the purpose of intensive care beyond the performance of technical tasks and medical training Planning and decision- making (unit assessment) - Ad hoc patient management plans generated during initial walk- around Procedures or tasks that require immediate activation by team members (e.g., extubation) because of patient developments are initiated - In-depth patient care plans are developed with medical/nursing teams - Team member concerns are invited and discussed, and key patient treatments/ investigations are outlined and prioritized - Potential developments in patient progression are discussed and contingency plans are outlined - When appropriate, major decisions are postponed until further information/second opinion has been received - Patient management plans, key decisions, and main information points are recapped with the nursing and medical staff Planning and decision making (unit monitoring) patient management plans are evaluated and adapted (e.g., changing treatments, conducting further tests) with senior trainee as patient conditions change - Factors impeding progression of patient management plans are identified and remedial steps taken (e.g., re-establishing team priorities) - Contingency plans (e.g., re- allocating team duties) are utilized in response to unexpected events/data (e.g., rapid patient deterioration) - Patients are admitted and discharged according to current and likely future demands within the unit (e.g., occupancy and staffing levels) - Management plans are recapped on leaving the unit Building Expectations for Teamwork: - Patient safety is explicitly made key to ICU, with team members being asked and expected to work effectively and courteously together regardless of personal issues Team structures and hierarchical systems through which tasks are allocated and information communicated are clearly explained to trainees and nursing staff - Trainee staff are taught to expect challenges on their decision-making by either medical or nursing staff - Coordination and communication on task work (e.g., data sharing, resource planning) is emphasized to team members so that functions are synchronized (e.g., multiple treatments, procedures or tests) |

Information gathering) Unit Monitoring) - Status/progress of priority patient treatments are monitored through visual inspections and discussions with medical and nursing staff - Information sources (charts, x-rays) are periodically reviewed - Patient plans with inadequate progress are identified/highlighted and discussed further with team members - Problems or unexpected changes to patient conditions are detected through dialogue with medical and nursing staff - Awareness for potential incoming/outgoing patients is maintained through communication with senior trainees/other units - Completion of routine housekeeping/care tasks (e.g., paperwork, patient nourishment) is checked Information gathering (Crisis Management) - A concise analysis of the situation from the trainee doctors/senior nurse is requested - When situation is managed by a trainee physician, indicators showing need for senior physician intervention are monitored (e.g., trainee indecision, severity of illness, management plan quality) - When performing tasks requiring high levels of attention (e.g., line insertion), team members are instructed to verbally update on new information (e.g., physiologic measures) - Information is considered “aloud” to share and confirm (i.e., identify inconsistencies) team member perspectives - Future situational/system information requirements are identified (e.g., availability of surgical support) Managing team member (Unit Monitoring) - status/problems in enacting the care plan are discussed with team members and guidance is given on technical/organizational issues - Medical trainees and nursing staff are made aware of new information on their unit or patient responsibilities (e.g., admissions, test results) - Trainee doctors are observed performing difficult procedures to detect indicators (e.g., stress, distraction, nurse unease) of a need to intervene Tasks that trainees have not previously performed or those that they are struggling to perform are supervised or performed by the senior physician for demonstration and skill retention purposes - Team members coordination is assessed (e.g., task duplication, information sharing) and instructions are given when necessary (e.g., re-confirming tasks, priorities, and inter- dependencies) Managing materials Demonstrating Clinical Excellence - Protocols and guidelines are followed, and if not, an explanation is given responsibility for medical decisions is taken, with trainees expected to take responsibility for their work - Interest is shown in clinical work and also development of trainee physicians and nursing staff - Low-level tasks are performed (e.g., notes, answering telephone) to demonstrate their importance - Clinical competence is displayed through concisely reaching and explaining decisions on patient management - Procedures are always performed to the highest of clinical standards - The successful management of difficult cases are used as ad hoc teaching points for trainees Planning and decision making (crisis Management) - A crisis management plan is quickly developed/adapted with the support of team members and situational overview is communicated - As required, team members opinions are sought on the management plan and alternative ideas considered if appropriate - Task priorities and contingency plans are quickly communicated to the team - Team members are verbally updated on changes to the management plan as the situation progresses - Team members not needed to provide support are asked to focus on normal patient care duties outlined within unit management plan Management team members (crisis Management) - Decision-making authority assumed if trainee is not coping or if patient safety may be at risk (e.g., time constraints, illness complexity) - Decision-making authority is asserted through clearly and appropriately delegating tasks (e.g., by seniority) and by giving precise instructions - Calmness is shown in decision- making and team members are encouraged to contribute information to the decision- making process - Difficulties in team members performing technical tasks are anticipated, with the senior physician - being prepared to supervise or dynamically swap functions with trainees as necessary - Should another team member or specialist be better suited to performing a task than the senior physician, help is requested - Team members are coordinated through them confirming their task duties and providing constant updates on task progression - As control is gained of the situation, decision-making is distributed back to senior trainee and nursing staff |

Team Member Interactions with the Senior Physician: - All team members are asked and expected to perform menial or administrative tasks Formalities are clearly established to new team members (e.g., calling the senior physician by title) - Trainee doctors are supported in contacting the senior physician when they have significant patient care concerns and are not criticized for raising false alarms Contributions and novel ideas from team members on unit and patient management are encouraged - Team members are encouraged to approach the senior physician if they experience professional/personal difficulties - When unintentional mistakes are made by medical or nursing staff, the senior physician remains calm - to establish a learning culture Empathy and compassion are shown to the trainees, with feedback being structured into learning points |

|

Künzle 2010 (18) |

Information collection Content-oriented leadership) Information transfer Content-oriented leadership) Distribution of roles and assigning tasks (Structuring leadership) assigning tasks (Structuring leadership |

Problem solving (Content-oriented leadership) Decision about procedures (Structuring leadership) Initiate an action (Structuring leadership) Structuring work process (Structuring leadership) Resource management (Structuring leadership) |

|

|

Edmondsn 2003 (21) |

- Emphasizing change and innovation as a way of life - Explaining need for others’ input - Direct invitation for others’ input |

- Communicating rationale for change - Communicating others’ importance through word/action - Acknowledge fallibility, under-react to others’ error - Motivating input - Minimizing power differences - Motivating effort -Psychological safety |

Cite this article as: Shamaeian Razavi N, Jalili M, Sandars J, Gandomkar R. Leadership Behaviors in Health Care Action Teams: A Systematized Review. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2022 (14 Feb);36:8. https://doi.org/10.47176/mjiri.36.8

References

- 1. Zaccaro SJ, Heinen B, Shuffler M. Team leadership and team effectiveness. Team effectiveness in complex organizations. Routledge. 2008. p. 117-146.

- 2.Fernandez R, Rosenman ED, Olenick J, Misisco A, Brolliar SM, Chipman AK. et al. Simulation-based team leadership training improves team leadership during actual trauma resuscitations: A randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(1):73–82. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kozlowski SW, Gully S, McHugh P, Salas E, Cannon-Bowers J. A dynamic theory of leadership and team effectiveness: developmental and task contingent leader roles. Res Pers Hum Resour Manag. 1996;14:253–306. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaccaro SJ, Rittman AL, Marks MA. Team leadership. Leadersh Q. 2001;12(4):451–483. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmutz J, Manser T. Do team processes really have an effect on clinical performance? A systematic literature review. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110(4):529–544. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker SH, Yule S, Flin R, McKinley A. Surgeons' leadership in the operating room: an observational study. Am J Surgery. 2012;204(3):347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grant EC, Grant VJ, Bhanji F, Duff JP, Cheng A, Lockyer JM. The development and assessment of an evaluation tool for pediatric resident competence in leading simulated pediatric resuscitations. Resuscitation. 2012;83(7):887–893. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mo D, O'Hara NN, Hengel R, Cheong AR, Singhal A. The Preferred Attributes of a Trauma Team Leader: Evidence From a Discrete Choice Experiment. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(1):120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams J. The elusive leadership competency. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(3):442–443. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-11-00162.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Corbett E, Whitcomb M. The AAMC project on the clinical education of medical students: clinical skills education. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges. 2004.

- 11. Education ACfGM. Leadership training program for chief residents [Available from: https://www.acgme.org/Meetings-and-Educational-Activities/Other-Educational-Activities/Courses-and-Workshops/Leadership-Skills-Training-Program-for-Chief-Residents.

- 12. Dath D, Chan M, Abbott C. CanMEDS 2015: from manager to leader. Ottawa, Canada: TRCoPaSo. 2015.

- 13.True MW, Folaron I, Colburn JA, Wardian JL, Hawley-Molloy JS, Hartzell JD. Leadership Training in Graduate Medical Education: Time for a Requirement? Mil Med. 2020;185(1-2):e11–e6. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usz140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenman ED, Ilgen JS, Shandro JR, Harper AL, Fernandez R. A systematic review of tools used to assess team leadership in health care action teams. Acad Med. 2015;90(10):1408–1422. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stone JL, Aveling E-L, Frean M, Shields MC, Wright C, Gino F. et al. Effective leadership of surgical teams: a mixed methods study of surgeon behaviors and functions. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104(2):530–537. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coolen EH, Draaisma JM, den Hamer S, Loeffen JL. Leading teams during simulated pediatric emergencies: a pilot study. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015;6:19–26. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S69925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parker SH, Flin R, McKinley A, Yule S. Factors influencing surgeons’ intraoperative leadership: video analysis of unanticipated events in the operating room. World J Surg. 2014;38(1):4–10. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Künzle B, Zala-Mezö E, Kolbe M, Wacker J, Grote G. Substitutes for leadership in anaesthesia teams and their impact on leadership effectiveness. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2010;19(5):505–531. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandez R, Rosenman ED, Olenick J, Misisco A, Brolliar SM, Chipman AK, Vrablik MC, Kalynych C, Arbabi S, Nichol G, Grand J. Simulation-based team leadership training improves team leadership during actual trauma resuscitations: A randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2020 Jan 1;48(1):73–82. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reader TW, Flin R, Cuthbertson BH. Team leadership in the intensive care unit: the perspective of specialists. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(7):1683–1691. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318218a4c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edmondson AC. Speaking up in the operating room: How team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams. J Manag Stud. 2003;40(6):1419–1452. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oza SK, van Schaik S, Boscardin CK, Pierce R, Miao E, Lockspeiser T. et al. Leadership Observation and Feedback Tool: A Novel Instrument for Assessment of Clinical Leadership Skills. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(5):573–582. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-18-00113.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leenstra NF, Jung OC, Johnson A, Wendt KW, Tulleken JE. Taxonomy of trauma leadership skills: a framework for leadership training and assessment. Acad Med. 2016;91(2):272–281. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parker SH, Flin R, McKinley A, Yule S. The Surgeons' Leadership Inventory (SLI): a taxonomy and rating system for surgeons' intraoperative leadership skills. Am J Surg. 2013;205(6):745–751. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dinh JV, Traylor AM, Kilcullen MP, Perez JA, Schweissing EJ, Venkatesh A. et al. Cross-disciplinary care: A systematic review on teamwork processes in health care. Small Group Res. 2020;51(1):125–166. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Légaré F, Adekpedjou R, Stacey D, Turcotte S, Kryworuchko J, Graham ID, Lyddiatt A, Politi MC, Thomson R, Elwyn G, Donner‐Banzhoff N. Interventions for increasing the use of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Gordon M, Baker P, Catchpole K, Darbyshire D, Schocken D. Devising a consensus definition and framework for non-technical skills in healthcare to support educational design: a modified Delphi study. Med Teach. 2015;37(6):572–577. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.959910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Capella J, Smith S, Philp A, Putnam T, Gilbert C, Fry W, Harvey E, Wright A, Henderson K, Baker D, Remine S. Teamwork training improves the clinical care of trauma patients. J Surg Educ. 2010;67:439–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leeper WR, Haut ER, Pandian V, Nakka S, Dodd-O J, Bhatti N, Hunt EA, Saheed M, Dalesio N, Schiavi A, Miller C. Multidisciplinary difficult airway course: An essential educational component of a hospital-wide difficult airway response program. J Surg Educ. 2018;75:1264–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ilgen DR, Hollenbeck JR, Johnson M, Jundt D. Teams in organizations: From input-process-output models to IMOI models. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:517–543. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009 Jun;26(2):91-108. [DOI] [PubMed]