SUMMARY

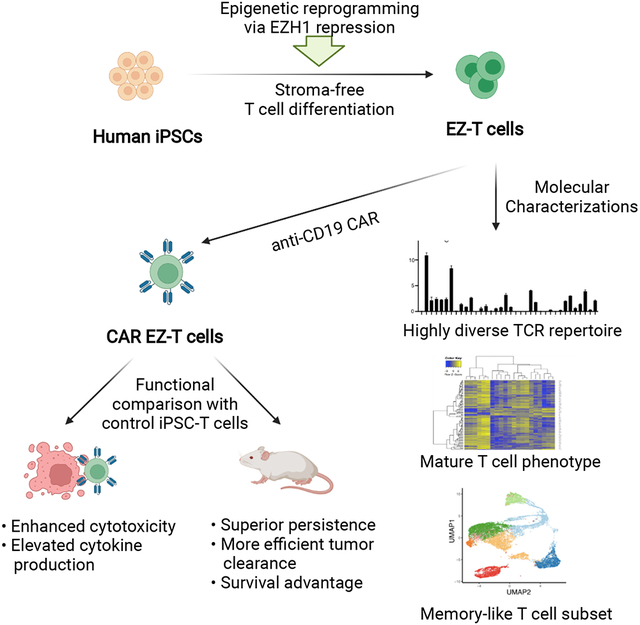

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) provide a potentially unlimited resource for cell therapies, but the derivation of mature cell types remains challenging. The histone methyltransferase EZH1 is a negative regulator of lymphoid potential during embryonic hematopoiesis. Here we demonstrate that EZH1 repression facilitates in vitro differentiation and maturation of T cells from iPSCs. Coupling a stroma-free T cell differentiation system with EZH1 knockdown-mediated epigenetic reprogramming, we generated iPSC-derived T cells, termed EZ-T cells, that display a highly diverse T-cell receptor (TCR) repertoire and mature molecular signatures similar to those of TCRαβ T cells from peripheral blood. Upon activation, EZ-T cells give rise to effector and memory T cell subsets. When transduced with chimeric antigen receptors (CARs), EZ-T cells exhibit potent antitumor activities in vitro and in xenograft models. Epigenetic remodeling via EZH1 repression allows efficient production of developmentally mature T cells from iPSCs for applications in adoptive cell therapy.

Keywords: pluripotent stem cells, hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, T cell differentiation, EZH1, CAR-T cells, cancer immunotherapy

Graphical Abstract

eTOC Blurb

Jing et al. combine a stroma-free differentiation system with EZH1-repression mediated epigenetic reprogramming to generate developmentally mature iPSC-derived CAR T cells with enhances antitumor activities.

INTRODUCTION

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell-based cancer immunotherapy has proven remarkably effective against lymphoid malignancies (June et al., 2018). In this approach, T cells collected from a patient’s blood are expanded in vitro and engineered to express tumor antigen-specific CARs so that the resulting CAR T cells are capable of recognizing and attacking tumor cells. CAR T cell therapy has demonstrated durable therapeutic efficacy and holds great promise for the cure of lymphoid malignancies, but the broader application of this breakthrough anti-cancer strategy has been impeded by several factors. To date, patients have been their own donors, and those who have been heavily pre-treated sometimes lack adequate numbers of functional T cells available for autologous harvest (Fesnak et al., 2016a; Fesnak et al., 2016b). Additionally, the expansion and engineering of autologous T cells requires time that some patients cannot afford. Consequently, this highly effective yet cumbersome, labor-intensive and expensive therapy is still not widely available. An alternative and more readily accessible source for CAR T cells is needed.

Human iPSCs represent an ideal source for scalable manufacture of off-the-shelf products for cell therapy. An early study explored the possibility of using human iPSCs to generate T cells for adoptive T-cell therapy, and showed that iPSC-derived T cells engineered with a CAR against the CD19 antigen were capable of inhibiting tumor growth in tissue culture and murine models (Themeli et al., 2013). However, these iPSC-CAR T cells displayed the transcriptional signature of innate-like γδ T cells, and were not as functionally robust as mature αβ T cells. More recent efforts have demonstrated enhanced T cell maturation when employing iPSCs generated from T cell sources that carry productively rearranged T cell receptors (TCRs) (Iriguchi et al., 2021) or incorporate organoid or thymic culture systems (Vizcardo et al., 2018; Montel-Hagen et al., 2019). Therefore, methods that enable efficient stroma-free production of fully functional, developmentally mature iPSC-T cells are needed to realize a broad range of iPSC-based adoptive T cell therapies.

Recent studies have revealed key roles for epigenetic regulators during definitive hematopoiesis and lymphoid development. Our lab identified EZH1, a component of polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), as a critical negative regulator of definitive lymphoid commitment during embryonic hematopoietic development (Vo et al., 2018). In this study, we tested the hypothesis that EZH1 repression might lead to more faithful in vitro recapitulation of T cell differentiation and developmental maturation from iPSCs. Below we show that iPSC-T cells derived in a stroma-free, serum-free system following EZH1 knockdown (EZ-T Cells) display a molecular signature that more closely approximates peripheral blood αβ T cells than innate-like γδ T cells, and that upon activation, are capable of giving rise to effector cytotoxic T cells and T cell subsets that exhibit a memory-like phenotype. EZ-T cells expressing anti-CD19 CARs showed more robust tumor-killing activity and cytokine secretion compared to control CAR-loaded iPSC-T cells generated without EZH1 repression. Injection of CAR-loaded EZ-T cells into B cell lymphoma-bearing mice led to superior persistence and more efficient tumor clearance than control iPSC-derived CAR T cells. Thus, a combination of EZH1 repression and stroma-free T cell differentiation allows efficient production of mature iPSC-T cells with enhanced functionality. Such an approach is compatible with commercial-scale production for CAR T cell-based immunotherapy.

RESULTS

A serum-free, stroma-free system allows efficient differentiation of iPSCs into T cells expressing diverse TCRs

Existing in vitro T cell differentiation protocols largely rely on engineered mouse stromal cells expressing Notch ligands, such as OP9-DL1/DL4 or MS5-DL1 cells, to provide continuous Notch signaling needed for T cell development. (Holmes and Zúñiga-Pflücker, 2009; Timmermans et al., 2009; Seet et al., 2017). Previous studies have shown that immobilized notch ligands support the induction of primary CD34+ HSPC into T cell lineages (Huijskens et al., 2014; Shukla et al., 2017). Recently, a stroma-free differentiation protocol was reported to generate T cells from TCR-transduced iPSCs or antigen-specific cytotoxic T cell (CTL)-derived iPSCs (Iriguchi et al., 2021). These iPSCs carry pre-rearranged TCRs and display different T cell differentiation kinetics than their wild-type counterparts (Themeli et al., 2013). Premature expression of endogenous or transgenic TCR has been shown to produce T cells with innate-like features (Terrence et al., 2000; Baldwin et al., 2005; Egawa et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2007). Though it has been shown that co-culture with OP9-DL4 cells yields iPSC-T cells with a broad TCR repertoire (Chang et al., 2014), whether a stroma-free system can fully recapitulate normal T cell development and support developmental maturation and random TCR rearrangement in vitro remains unclear. To answer this question, we sought to produce highly differentiated T cells from non-T cell-derived iPSCs while avoiding animal stromal cells and serum. The differentiation procedure is illustrated in Figure 1A. In the first step, human erythroblast-derived 1157 iPSCs were induced to form embryoid bodies to generate HE cells with hematopoietic potential using a previously reported protocol (Ditadi et al., 2015). The CD34+ HE cells were collected and seeded as a monolayer on tissue culture dishes coated with delta-like notch ligand 4 (DLL4) and VCAM-1 (Shukla et al., 2017). To initiate T cell specification, HE cells were cultured in SFEMII media supplemented with a cocktail of cytokines (SCF, FLT3, IL-7, IL-3, TPO). During this time period, HE cells underwent endothelial-to-hematopoietic transition (EHT), giving rise to floating cells that contain CD5+CD7+ T cell progenitors (proTs). On day 14, the floating hematopoietic cells were collected and replated on new DLL4 coated plates followed by three weeks of culture with FLT3 and IL-7. The proT cells continued to expand and passed through a transient CD3−CD4+ immature CD4 single positive (ISP) stage before activating expression of CD8 to form CD4+CD8+ double positive (DP) cells (Fig. 1B, C). After five weeks of differentiation CD3+TCRαβ+ T cells were detected. Further culture of these cells in the presence of anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies and IL-15 facilitated the induction of single positive (SP) cells. At week 6, a majority of cells expressed CD3 with the population consisting of both DP and CD4/CD8 SP T cells (Fig. 1D).

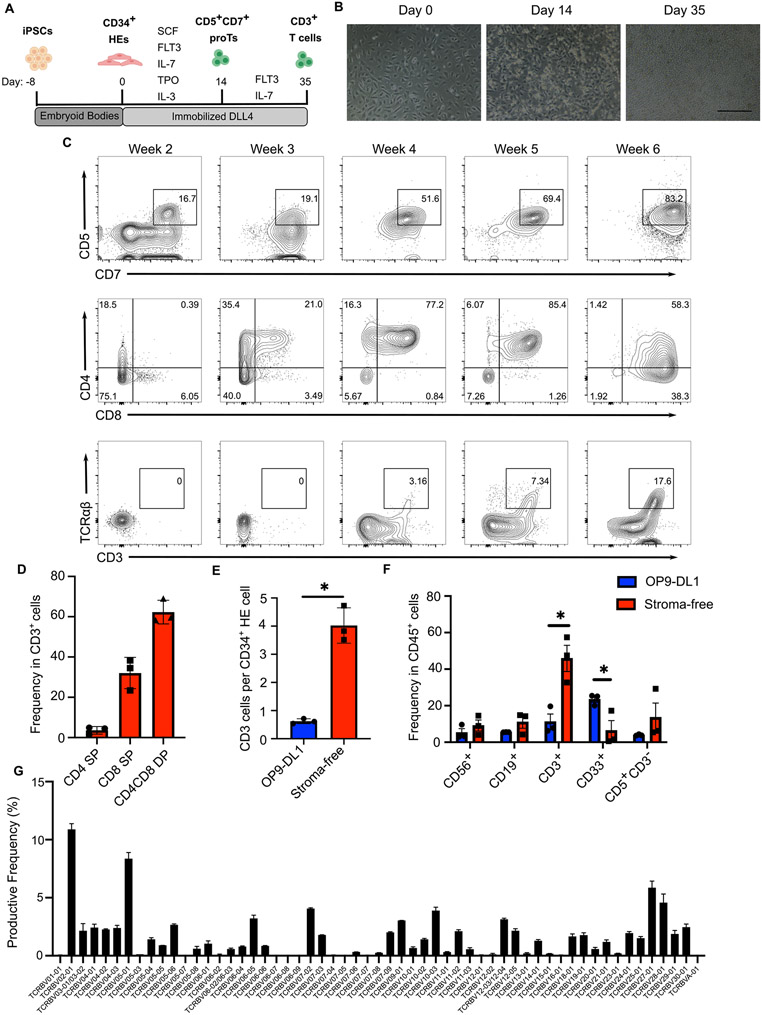

Fig. 1. Stroma-free differentiation of human iPSCs into T cells.

A) Schematic illustration of the stroma-free T cell differentiation. B) Representative images showing day 0 CD34+ HE cells, day 14 proT cells, and day 35 T cells. Scale bar: 200μm. C) Expression of T cell lineage-specific markers during the stroma-free T cell differentiation of iPSCs (gated on CD45+ cells). D) Frequencies of CD4, CD8, and DP T cells in CD3+ cells after 6 weeks of differentiation (n=3, mean ± SEM). E) Numbers of week 6 CD3+ T cells generated via OP9-DL1 (blue) or stroma-free (red) differentiation, normalized to numbers of CD34+ HE cells seeded on day 0 (n=3, mean ± SEM, * P≤0.05). F) Frequencies of B cells (CD19+), NK cells (CD56+), Myeloid cells (CD33+), T cell precursors (CD5+CD3−), and T cells (CD3+) in CD45+ hematopoietic cells after 6 weeks of T cell differentiation using the OP9-DL1 (blue) or stroma-free (red) method (n=3, mean ± SEM, * P≤0.05, ** P≤0.01). G) Frequencies of Vβ family genes determined by sequencing of the TCRβ CDR3 region (n=2)

To further evaluate the yield and efficiency of our stroma-free protocol, we differentiated iPSCs into T cells using both the stroma-free method and a previously published OP9-DL1 co-culture system (Themeli et al., 2013). The stroma-free protocol resulted in a significant increase of CD3+ T cell production (Fig. 1E). Compared to OP9-DL1 co-culture, the stroma-free system also led to more efficient T cell-specific differentiation, indicated by an increased proportion of T cells and concomitant reductions of non-lymphoid cell frequencies (Fig. 1F, S1A). To determine whether the stroma-free differentiation was accompanied by normal TCR rearrangement, we extracted genomic DNA from stroma-free iPSC-T cells and sequenced the complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) of the TCRβ locus to profile the TCR repertoire. ImmunoSEQ analysis identified tens of thousands of unique rearrangements with a high degree of diversity in the usage of Vβ family genes, demonstrating random recombination of CDR3 in the iPSC-T cells (Fig. 1G). Taken together, these data establish a stroma-free system that faithfully recapitulates normal T cell development to produce iPSC-T cells with a highly diverse TCR repertoire.

EZH1 repression facilitates in vitro T cell differentiation from iPSCs.

Previous studies have shown that EZH1 acts as a key regulator of hematopoietic multipotency, and repression of EZH1 function promotes lymphoid potential during mouse and zebrafish embryonic development. (Vo et al., 2018; Soto et al., 2021). To determine whether inhibition of EZH1 would facilitate in vitro T cell differentiation from iPSCs, we performed shRNA-mediated EZH1 knockdown during T cell specification from iPSC-derived CD34+ HE cells (Fig. S1B, C). EZH1-knockdown HE cells were then induced to differentiate into EZ-T cells via the stroma-free system, and compared with control iPSC-SF-T cells derived as above (Fig. 2A). EZH1 knockdown produced a ~2 fold increase in live cells after 2 weeks of differentiation (Fig. 2B), and after 6 weeks resulted in both a higher proportion of T cells amongst CD45+ hematopoietic cells and an increased absolute number of T cells generated from each starting CD34+ cell, suggesting enhanced T cell differentiation specificity and efficiency (Fig. 2C,D, S1D). Similar results were obtained in multiple iPSC lines that were derived from distinct donors using different reprogramming strategies, indicating that the EHZ1-knockdown mediated enhancement of T cell differentiation was not cell line-restricted (Fig. S1E). As an alternative to the shRNA-mediated EZH1 knockdown, we engineered a doxycycline-inducible CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) construct into iPSC-derived CD34+ HE cells to transcriptionally repress EZH1 expression (Fig. S2A). Interestingly, CRISPRi mediated EZH1 knockdown during T cell specification (week 0-2) led to a significant increase in the production of CD3+ T cells, while induction of EZH1-CRISPRi after the formation of proT cells (week 2-5) failed to promote T cell differentiation (Fig. S2B). In control cells, the expression of EZH1 significantly increased during specification of HE into proT cells and was down-regulated after the proT stage (Fig. S2C). EZH2, a homolog of EZH1 that likewise acts as a catalytic subunit of the PRC2 complex, was highly expressed at the later stages of T cell differentiation in both control and EZH1 shRNA-treated cells (Fig. S2D). Such an observation is in agreement with previous findings that EZH1 but not EZH2 functions in HE cells to inhibit lymphoid lineage commitment (Vo et al., 2018) and explains why inhibition of EZH1 had no impact on later stages of T cell differentiation. After 6 weeks of differentiation, while the control iPSC-SF-T cells contained a substantial proportion of DP T cells, the EZ-T cells consisted predominantly of CD8 or CD4 SP cells (Fig. 2E). In contrast to the limited production of SP T cells when differentiated on OP9-DL1 stroma, (La Motte-Mohs et al., 2005; Montel-Hagen and Crooks, 2019), our data demonstrate that a combination of stroma-free differentiation with EZH1-knockdown supports more efficient induction of SP cells.

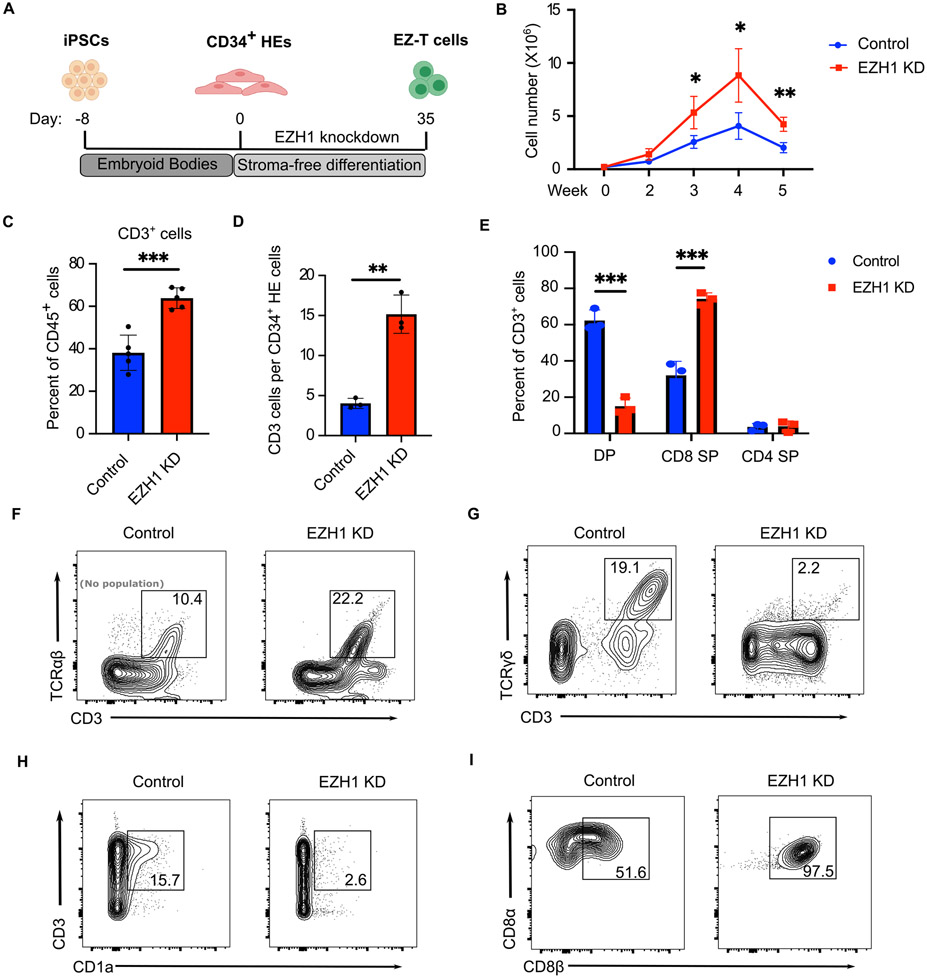

Fig. 2. EZH1 knockdown facilitates in vitro T cell differentiation from iPSCs.

A) Schematic illustration of EZ-T cell generation. B) Numbers of live cells during T cell differentiation using control (blue) or EZH1 knockdown (KD) (red) iPSC-derived HE cells (n=3, mean ± SEM, * P≤0.05). C) Frequencies of CD3+ T cells in CD45+ cells generated from control (blue) or EZH1 KD (red) cells after stroma-free T cell differentiation (n=3, mean ± SEM, *** P≤0.001). D) Numbers of CD3+ T cells generated from control (blue) or EZH1 KD (red) cells, normalized to numbers of CD34+ HE cells seeded on day 0 (n=3, mean ± SEM, ** P≤0.01). E) Frequencies of CD4, CD8, and DP T cells generated from control (blue) or EZH1 KD (red) cells after 6 weeks of stroma-free T cell differentiation (n=3, mean ± SEM, *** P≤0.001). F-H) Expression of CD3 and TCRαβ /TCRγδ/CD1a in control and EZH1 KD cells after stroma-free T cell differentiation, gated on CD45+ cells. I) Expression of CD8α and CD8β in control and EZH1 KD cells after stroma-free T cell differentiation, gated on CD8 T cells.

As previous studies have shown that iPSC-derived T cells tend to resemble innate-like γδ T cells (Nishimura et al., 2013; Vizcardo et al., 2013; Themeli et al., 2013), we performed immunophenotypic and molecular analyses to characterize the nature of T cells produced following EZH1 knockdown. It has been suggested that T cell-derived iPSCs (T-iPSCs) bearing rearranged endogenous TCR genes result in premature expression of TCR receptors during in vitro differentiation (Themeli et al., 2013), whereas T cell differentiation from non-T cell derived-PSCs displays similar kinetics to cord blood (CB) CD34+ cells, with both gradually upregulating surface TCR/CD3 expression only after the DP stage (Seet et al., 2017) (Fig. 1C). After differentiation, EZ-T cells displayed a significant increase in CD3+TCRαβ+ and decrease in CD3+TCRγδ+ T cells (Fig. 2F-G, S2E-F), indicating that EZH1 knockdown promotes differentiation towards αβ T cell fate rather than γδ T cells. EZH1 knockdown also resulted in a decrease of CD1a, which is expressed in thymocytes but not mature peripheral blood T cells, further demonstrating that EZ-T cells exhibit a more mature T cell phenotype (Fig. 2H, S2G). Unlike mature, conventional cytotoxic T cells that express the CD8αβ heterodimer, innate-like γδ+ T cells or intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) express CD8 as a CD8αα homodimer, which has been considered a less robust co-receptor and may even suppress TCR activation (Bosselut et al., 2000; Holler and Kranz, 2003; Cheroutre and Lambolez, 2008). Studies using OP9-DL1 stroma have yielded CD8αα T cells (Themeli et al., 2013; Maeda et al., 2016), while recent protocols using 3D artificial thymic organoids or a Notch ligand-based feeder-free system have yielded iPSC-T cells that express CD8αβ (Montel-Hagen et al., 2019; Iriguchi et al., 2021). Similarly, our stroma-free differentiation protocol supports the production of CD8αβ T cells, with EZH1 knockdown promoting higher yields of CD8αβ T cells, and barely detectable quantities of innate-like CD8αα T cells (Figure 2I, S2H). Collectively, these analyses revealed that repression of EZH1 promotes efficient in vitro differentiation of iPSC cells into mature SP T cells.

EZ-T cells display a molecular signature similar to peripheral blood TCRαβ T cells

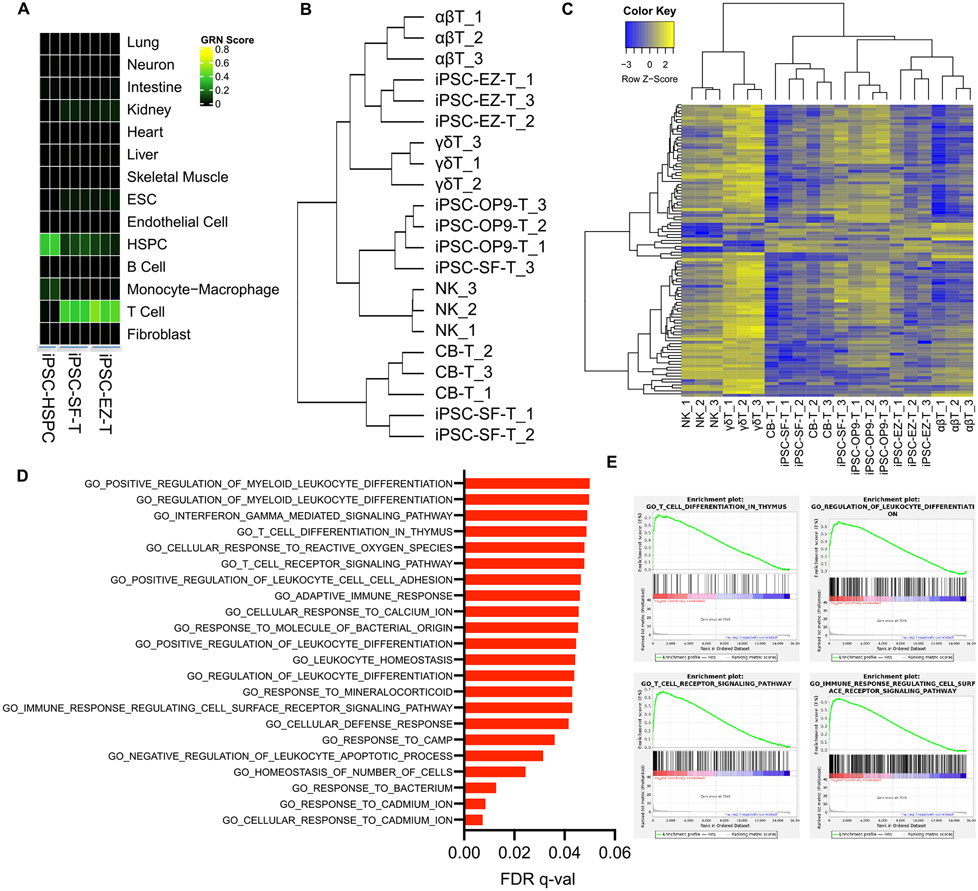

To assess the extent to which our iPSC-T cells resemble their in vivo counterparts, we evaluated the fidelity of stroma-free in vitro T cell differentiation via CellNet, a network biology platform used to analyze the faithfulness of cell fate conversions and the similarity between in vitro derived cell types and gold-standard native tissue equivalents (Cahan et al., 2014; Radley et al., 2017). Analysis of RNA-seq gene expression profiles by CellNet revealed a high degree of similarity between iPSC-derived T cells and donor-derived T cells isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), and clear discrimination from less differentiated multipotent hematopoietic stem or progenitor cells (HSPCs) (Fig. 3A, S3A). We next sought a more refined analysis and therefore performed RNA-seq to compare the gene expression profile of EZ-T cells with PBMC-derived TCRαβ T cells, PBMC-TCRγδ T cells, and PBMC-NK cells, as well as T cells generated from CB CD34+ HSPCs or iPSCs in the absence of EZH1 knockdown via in vitro-differentiation on OP9-DL1 stroma or our stroma-free system. Examining the expression of T cell signature genes, we found that iPSC-T cells differentiated via our stroma-free protocol without EZH1 knockdown (PSC-SF-T) were more similar to CB-HSPC-derived T cells than were iPSC-T cells differentiated via OP9-DL1 stroma (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the EZ-T cells were most similar to PBMC TCRαβ T cells. Furthermore, we compared the transcriptional signature of PBMC-derived TCRαβ T with that of TCRγδ T cells and identified a list of genes that can be used to distinguish αβ T from γδ T cells. Expression levels of these genes were determined across all cell types, and the result again showed that EZ-T cells exhibited a gene expression profile that was most similar to αβ T cells (Fig. 3C). To investigate the molecular mechanism underlying the mature phenotype of EZ-T cells, we performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) on the most significantly upregulated genes in EZ-T cells compared to control iPSC-SF-T cells (lacking EZH1 knockdown), and observed that these genes were highly enriched in biological processes directly associated with T cell differentiation or function (Fig 3D, E). To access whether the differences identified by bulk RNA-seq were due to changes in cell type compositions, we performed scRNA-seq analysis on control iPSC-SF-T cells and EZ-T cells and compared gene expression profiles for the sub-populations of TCRαβ T cells (TRAC+TRDC−). A relatively small number of genes were differentially expressed between control iPSC-SF αβ T cells and those with EZH1 knockdown (Table S1). Interestingly, TCRαβ T cells with EZH1 knockdown more abundantly expressed TRAC, TRBC2, CD2, and CD7, and showed a greater down-regulation of residue "innate" genes (TRDC, KLRB1) (Fig. S3B). Collectively, EZH1 repression during in vitro iPSC differentiation promotes the production of αβ T cells that display a more mature phenotype.

Fig. 3. EZ-T cells display molecular features of mature TCRαβ T cells.

A) Heatmap showing CellNet analysis of RNA-seq data from iPSC-derived CD34+ HSPCs and iPSC-derived T cells generated via stroma-free protocol, either with EZH1 knockdown (iPSC-EZ-T), or without (iPSC-SF-T). B) Dendrogram representing hierarchical cluster analysis based on expression of TCR pathway genes (BIOCARTA_TCR_PATHWAY, M19784) (n=3). C) Heatmap showing unsupervised clustering analysis based on TCRαβ signature genes (n=3). D) Top GO terms of biological process enriched in iPSC-EZ-T cells vs. iPSC-SF-T cells by GSEA analysis (n=3). E) GSEA enrichment plots showing over-representation of gene sets related to T cell development and functions.

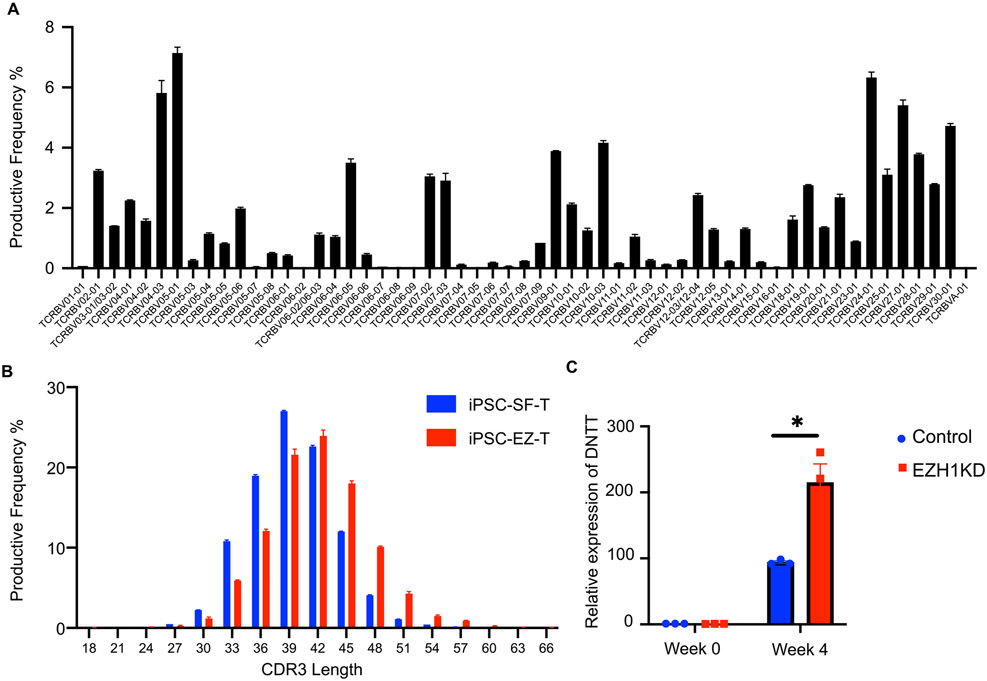

We next performed immunosequencing to determine the TCR repertoire of EZ-T cells, and observed a high degree of TCRβ diversity with no preferential Vβ gene usage (Fig. 4A), suggesting that EZH1-knockdown did not cause significant clonal expansion of individual T cells with specific TCR rearrangements. Notably, EZ-T cells displayed longer CDR3 regions than iPSC-SF-T cells without EZH1 knockdown (Fig. 4B). iPSC-derived T cells tend to have shorter CDR3 regions than mature peripheral blood T cells, likely due to lower expression levels of Terminal Deoxynucleotide Transferase (TdT), the enzyme responsible for random nucleotide insertion during VDJ recombination, which is encoded by the DNTT gene (Montel-Hagen et al., 2019). To test this, we determined the expression levels of TdT/DNTT in both iPSC-derived HE cells and week 4 DP T cells harboring control or EZH1 shRNA. As expected, TdT/DNTT was only expressed in DP T cells and more abundantly expressed in cells with EZH1-knockdown (Fig. 4C). These data suggest that EZH1-knockdown during iPSC differentiation promotes T cell maturation, with the resulting EZ-T cells exhibiting molecular signatures that most closely resemble peripheral blood TCRαβ T cells.

Fig. 4. TCR repertoire analysis of EZ-T cells.

A) Frequencies of Vβ family genes in EZ-T cells determined by sequencing of the TCRβ CDR3 region (n=2). B) TCRβ CDR3 length of iPSC-EZ-T cells (red) compared to control iPSC-SF-T cells without EZH1 knockdown (blue) (n=2). C) Relative expression levels of TdT/DNTT in undifferentiated iPSCs or iPSC-SF-T cells with (red) or without (blue) EZH1 KD (n=3, mean ± SEM, * P≤0.05).

EZ-T cell subsets display effector and memory-like phenotypes.

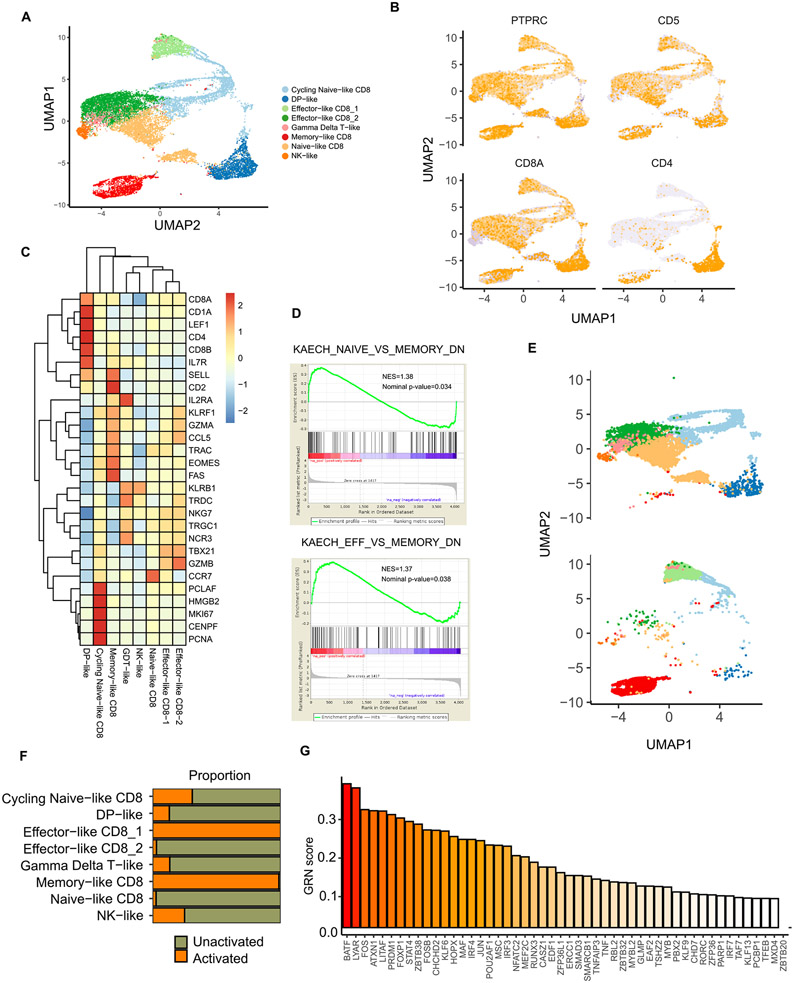

After exiting the thymus, newly produced naive T cells give rise to effector and memory subsets which are characterized by distinct phenotypic and functional features and cumulatively shape T-cell immunity (Kumar et al., 2018). T cells generated from iPSCs have previously been shown to display a naive phenotype (Seet et al., 2017; Iriguchi et al., 2021), but which T cell subsets can be derived from naive iPSC-T cells is still largely unknown. To answer this question, we used single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to profile the distinct changes and characterize the T cell subsets that arise during T cell differentiation and activation. Upon the completion of EZ-T cell differentiation, we sorted CD45+ hematopoietic cells before and after T cell activation and generated 11,131 single-cell transcriptomes. We identified eight clusters across all samples, with the majority of cells manifesting a T cell fate (CD5+) (Fig. 5A, B). Consistent with previous immunophenotypic analyses, cells were predominantly CD8 SP cells with lower amounts of CD4 SP and DP T cells (Fig. 5B). Further analyses on the signature gene expression profiles revealed only small proportions of innate NK-like (CD56+CD5−KLRB1+) or γδ T cells (TRDC+TRGC1+). For the mature T cell compartment, we identified two naive-like T cell clusters (CCR7+SELL+IL2RAlowLEF1high) distinguished by their cycling status (Willinger et al., 2006), two effector-like clusters (CCR7−SELL−GZMBhighGZMAhighNKG7+), and notably, a memory-like T cell cluster that express low levels of cytotoxicity-related genes (GZMB, NKG7) and highly express genes that have been linked to memory T cell identities (CCR7+SELL+IL7R+CD2highCCL5highFAShighEOMEShigh) (Sanders et al., 1988; Huster et al., 2004; Intlekofer et al., 2005; Marçais et al., 2006). We further validated the presence of a memory-like T cell subset by detecting the expression of CD45RA, CD45RO, and CCR7 (Fig. S4A). Moreover, it is known that cytotoxic T cells can express NK cell genes, including inhibitory NK cell receptors that raise the threshold of TCR stimulation and dampen T cell responses (Vivier and Anfossi, 2004). Among the inhibitory NK cell receptors, KLRB1 is expressed by tumor infiltrating effector T cells for several types of human cancer, negatively regulating their antitumor activity (Mathewson et al., 2021). A more recent study further identified KLRB1, together with other NK cell receptors, as a hallmark of exhausted, dysfunctional CAR T cells (Good et al., 2021). In our cell populations, the memory-like T cell cluster expressed lower levels of NK cell genes including KLRB1, which further distinguishes these cells from the terminally differentiated effector-like T cell clusters (Fig. 5C). In addition to the expression of major marker genes, GSEA analysis indicated a gene expression profile similar to that of memory T cells rather than naive or effector T cells (Fig. 5D). None of the clusters showed substantial expression of inhibitory receptors or regulatory T cell markers (Fig. S4B).

Fig. 5. Single cell RNA-seq analysis identifies memory-like T cell subsets in EZ-T cells after activation.

A) Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) visualization of all the CD45+ cells generated from EZ-T cell differentiation with and without activation. B) UMAP visualization of the expression of hematopoietic and T cell markers. C) Heatmap showing expression levels of T/NK cell signature genes across all clusters. D) GSEA analysis of the memory-like CD8 cluster showing over-representation of genes enriched in memory T cells but not naive or effector T cells. E) UMAP analysis comparing cell types in CD45+ cells generated from EZ-T cell differentiation before and after activation. F) Proportion of cells in unactivated and activated CD45+ cells generated via EZ-T cell differentiation. G) CellRouter analysis showing transcriptional regulators enriched in the memory-like CD8 T cell cluster.

We next sought to capture the compositional changes in immune cell clusters during T cell expansion. Compared to unactivated cells, T cell expansion resulted in enrichment of mature T cell populations and a concomitant reduction of immature DP T cells and innate-like cells (NK-like cells, γδ T-like cells). Similarly, naive-like T cells were predominantly present in unactivated samples and significantly reduced upon activation. Importantly, T cells displaying a memory-like phenotype were exclusively detected in activated cells after extended expansion, suggesting the occurrence of cell fate conversions from naive-like cells into more differentiated subsets (Fig. 5E, F). To examine this, we performed gene regulatory network (GRN) analysis using CellRouter, aiming to reconstruct the trajectories of cell state transitions from naive to memory-like T cells (Lummertz da Rocha et al., 2018). We identified a series of key transcriptional networks governing the changes in T cell composition, and found multiple top-ranked transcriptional regulators, including BATF, LYAR, LITAF, IRF4, and RUNX3, which were previously known to drive the development of long-lived memory T cells (Fig. 5G) (Seo et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2020; Mackay et al., 2013; Harberts et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2018b). Additionally, we performed Single-Cell rEgulatory Network Inference and Clustering (SCENIC) analysis to map regulons enriched in each annotated cell type (Aibar et al., 2017) (Fig. S4C). Consistent with the CellRouter analysis, SCENIC identified a similar set of regulons associated with the memory-like subset. In particular, regulatory networks that have been linked to the generation and homeostasis of memory-T cells, such as BATF and IRF9 regulons, were exclusively enriched in the memory-like cluster (Kurachi et al., 2014; Martinet et al., 2015; Seo et al., 2021) (Fig. S4D). Finally, we compared EZ-T cells with a range of hematopoietic cells by mapping our scRNA-seq data on a publicly available reference dataset that includes hematopoietic stem cells, lineage-restricted blood progenitors, and terminally differentiated lymphoid/erythroid/myeloid cells collected from healthy bone marrow and peripheral blood samples (Granja et al., 2019) (Fig. S5A). Almost all the CD45+ cells derived via EZ-T cell differentiation overlap with peripheral blood T cells; cells that represent early HSPCs or other non-lymphoid lineages were barely detectable (Fig. S5B). Consistent with previous analysis, following activation a subset of EZ-T cells emerged as CD8 central memory T cells (Fig. S5B). A cross comparison between iPSC-derived T cells with their in vivo counterparts also indicates that the memory-like CD8 cluster in EZ-T cells closely correlates with peripheral blood central memory CD8 T cells (Fig. S5C). Taken together, iPSC-derived EZ-T cells recapitulate the differentiation of naive T cells that give rise to effector cells and T cell subsets that exhibit a memory-like phenotype.

CAR T cells generated from EZ-T cells exhibit enhanced antitumor activity

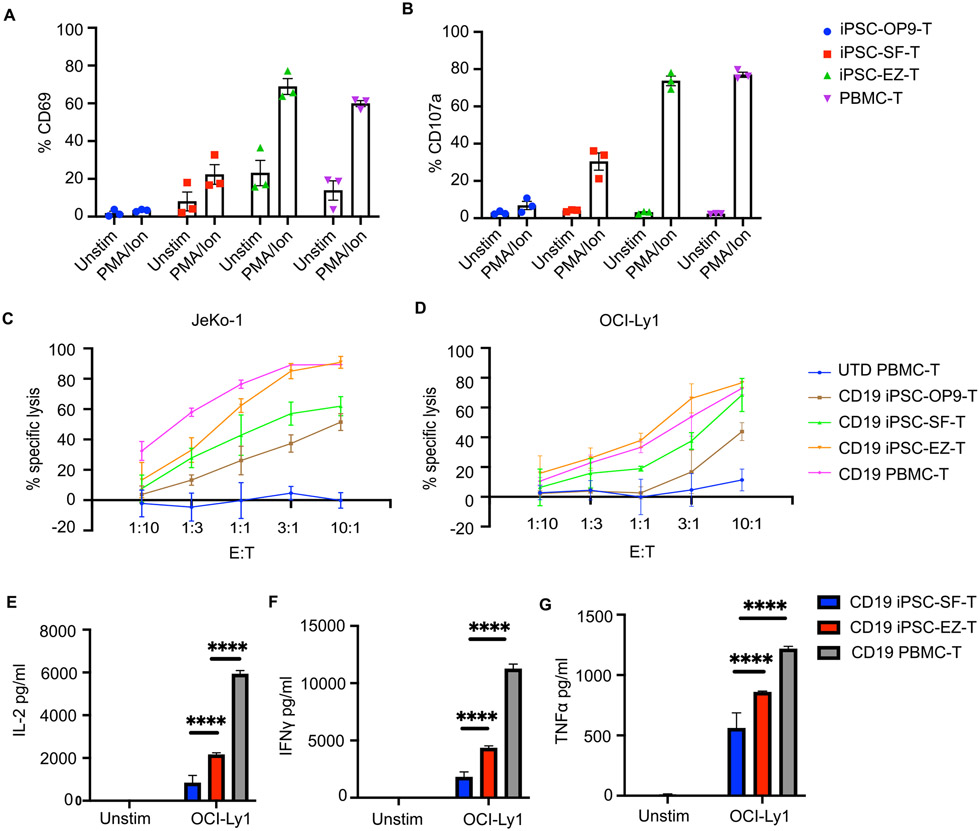

Having shown that EZ-T cells display molecular features similar to those of mature peripheral blood TCRαβ T cells, we next performed functional characterizations of effector cell properties. Compared to iPSC-OP9-T cells or iPSC-SF-T cells, EZ-T cells showed more robust upregulation of CD69 in response to PMA/ionomycin treatment (Fig. 6A). Consistently, EZ-T cell expressed higher levels of CD107a than control iPSC-SF-T cells upon PMA/ionomycin stimulation; the degranulation efficiency was comparable to peripheral blood-derived T cells (Fig. 6B). In light of the EZ-T cells' superior activation/degranulation efficiency, we next explored whether EZ-T cells could be used to generate CAR T cells with enhanced cytotoxic effector functions. We transduced control iPSC-OP9-T cells, iPSC-SF-T cells, EZ-T cells, and donor-derived peripheral blood T cells with anti-CD19 CARs containing a 4-1BB costimulatory domain, and co-cultured with two different types of CD19+ lymphoma cells to compare their cytotoxicity profiles. CD19 CAR EZ-T cells caused more efficient specific target cytolysis against both Jeko-1 and OCI-Ly1 cells than CAR T cells derived from control iPSC-OP-9 and iPSC-SF-T cells, and displayed a specific killing capacity comparable to PBMC-T cells (Fig. 6C, D). Cytotoxicity assays were also performed using presorted iPSC-SF TCRαβ T cells with or without EZH1 knockdown. Similarly, TCRαβ T cells with EZH1 knockdown elicited more efficient killing of target tumor cells (Fig. S6A). Moreover, co-culture with tumor cells triggered EZ-T cells to secrete higher levels of cytokines that are essential for T cell antitumor responses, including IL-2, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) (Fig. 6E, F, G). Both control SF-T and EZ-T cells produced lower levels of cytokines than PBMC T cells. Since iPSC-derived T cells are predominantly CD8+ cytotoxic cells whereas the PBMC T cells include a large proportion of CD4+ cells, this observation is consistent with the higher cytokine production capacity/profile of CD4 T cells (Pfizenmaier et al., 1984; Ngai et al., 2007). Collectively, these data indicate that EZ-T cells exhibit enhanced cytotoxic and cytokine-producing effector functions against tumor cells in vitro.

Fig. 6. EZ-T cells display enhanced effector functions.

A) CD69 expression and B) CD107a degranulation of iPSC-derived T cells and peripheral blood T cells after 6 hours of PMA/ionomycin stimulation, determined by flow cytometry analysis (n=3, mean ± SEM). C) CAR-T cells generated from iPSC-derived T cells or peripheral blood T cells were co-cultured with JeKo1 and D) OCI-Ly1 tumor cell lines at indicated effector to target (E:T) ratios. Bar graph showing percentages of specific cytolysis of target tumor cells (n=3, mean ± SEM). E) Production of IL-2, F) INFγ, and G) TNFα by CD19 CAR T cells generated from iPSC-SF-T, iPSC-EZ-T, and PBMC-T cells cultured in the absence (Unstim) and presence of OCI-Ly1 target tumor cells (n=3, mean ± SEM, **** P≤0.0001).

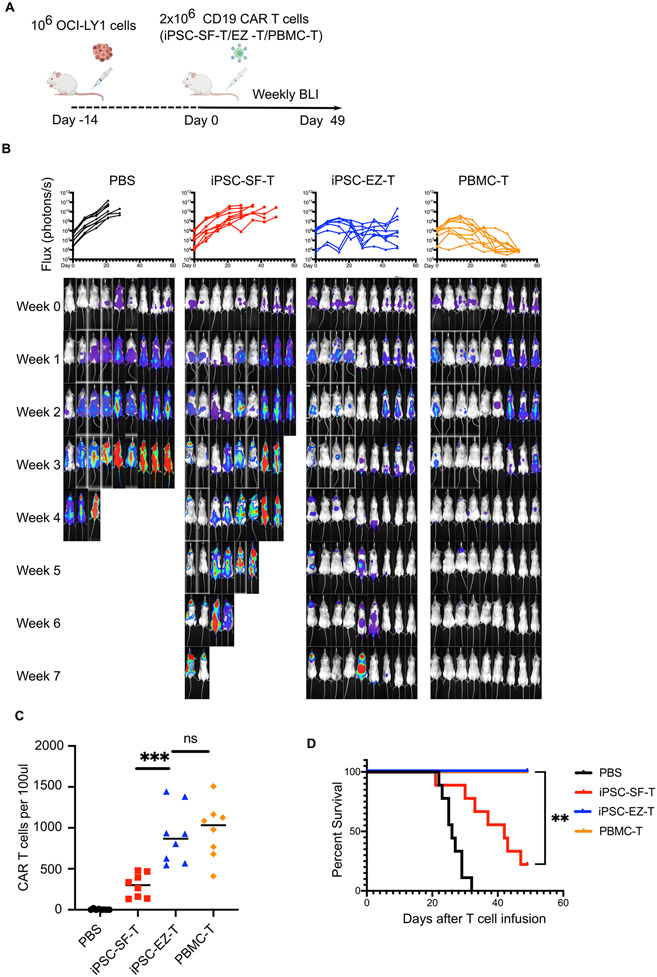

To further evaluate the efficacy of EZ-T cell-derived CAR T cells, we established a xenograft mouse model by intravenously injecting luciferase-expressing diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) cells (OCI-Ly1) into immunodeficient Non-obese diabetic-SCID IL2Rgammanull (NSG) mice. These animals were then infused with PBS, CD19 CAR iPSC-SF-T cells, CD19 CAR EZ-T cells, or PBMC-derived CD19 CAR T cells, and subjected to weekly bioluminescence imaging (BLI) to assess tumor burden (Fig. 7A). Although CAR T cells generated from iPSC-SF-T cells suppressed tumor growth, they failed to eradicate tumor cells in any animal after 7 weeks. Notably, CAR EZ-T cells displayed significant improvement of efficacy and were capable of eradicating tumor cells and caused complete remissions in most animals (Fig. 7B). Consistent with improved tumor clearance, more CAR EZ-T cells were detected in peripheral blood than control CAR iPSC-SF-T cells 3 weeks after injection (Fig. 7C), and most circulating EZ-T cells expressed αβTCR and not γδ TCR (Fig. S6B), suggesting that the enhanced persistence of EZ-T cells is largely due to the enrichment of TCRαβ T cells. As a result, though some mice showed persistent BLI signal intensity, injection of CAR EZ-T cells produced comparable survival rates to PBMC CAR T cell treatment for the 7-week duration of the experiment (Fig. 7D, S7A). To exclude that EZH1 repression may cause abnormal expansion of EZ-T cells, we administrated both control and EZ-T cells into healthy mice and monitored the presence of CAR T cells over a long time period. Without simultaneous tumor engraftment, CAR T cells were barely detectable in peripheral blood after 5 weeks, and these animals remained healthy and were free of human T cells after 20 weeks (Fig. S7B). In summary, when engineered with anti-CD19 CARs, EZ-T cells elicit superior antitumor effects relative to control iPSC-SF-T cells lacking EZH1 knockdown, both in vitro and in vivo.

Fig. 7. CD19 CAR EZ-T cells mediate more robust in vivo tumor clearance.

A) Schematic illustration of in vivo CAR T cell functional studies using a DLBCL mouse model. B) Bioluminescent images of tumor xenografts over time and quantification of the tumor burden over time in each animal (n=9 animals from 3 experiments), represented by mean total flux (photons/sec). C) Numbers of CAR T cells per 100μl peripheral blood from each animal, determined by flow cytometry 3 weeks after CAR T cell injection (n=8, *** P≤0.001). D) Kaplan-Meier curve showing percentage survival of untreated animals (black) and animal groups treated with CD19 CAR T cells generated from control iPSC-SF-T (red), iPSC-EZ-T (blue), or PBMC-T cells (yellow) (n=9, ** P≤0.01 by log-rank test).

DISCUSSION

The identification of signaling pathways that are essential for T cell development has led to the design of protocols that allow the generation of T cells in vitro from human pluripotent stem cells (Holmes and Zúñiga-Pflücker, 2009; Timmermans et al., 2009; Seet et al., 2017). However, past in vitro differentiation approaches have been plagued by dependency on mouse stromal cells as well as deficiencies in terminal stages of T effector cell maturation, thereby limiting their clinical application in adoptive immunotherapy. The generation of definitive (adult-type) hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) with lymphoid potential and differentiation of functional T cells from iPSCs has proven difficult, as in vitro differentiation of iPSCs tends to default into the production of embryonic cell types (Doulatov et al., 2013; Sugimura et al., 2017). Past studies have demonstrated that iPSC-derived T cells resemble innate-like γδ T cells and are not as robustly functional as primary αβ T cells, again suggesting that our ability to recapitulate the mechanisms underlying commitment and progression of T cell development is incomplete. Screening of critical epigenetic modifying enzymes during the generation of HSPCs discovered that EZH1 plays a central role in regulating multipotency and lymphoid potential in embryonic blood progenitors (Vo et al., 2018). As a component of PRC2, EZH1 modulates chromatin accessibility by mediating histone H3 lys27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) (Shen et al., 2008). During embryonic hematopoiesis, EZH1 represses the transcription of genes associated with definitive hematopoietic fates, and EZH1 deficiency in genetically engineered mice promotes the precocious emergence of bona fide HSC and lymphoid progenitors (Vo et al., 2018). A recent study in the zebrafish model further showed that EZH1 suppresses HSPC formation by regulating HE commitment. Specifically, EZH1 enhances Notch signaling to facilitate arterial gene expression at the expense of HE specification and HSPC development. As a result, knockdown of EZH1 unlocks definitive hematopoiesis and leads to enhanced production of multipotent HSPCs with lymphoid potential (Soto et al., 2021).

In light of the repressive function of EZH1 in lymphopoiesis, we investigated the impact of EZH1 knockdown during in vitro T cell differentiation. Although 3D thymic-like culture systems have been established to mimic mouse or human T cell development and yield iPSC-derived T cells that display a mature phenotype, these methods rely on engineered stromal cells or fetal thymic cells derived from mouse (Vizcardo et al., 2018; Montel-Hagen et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2022). Therefore, we developed a stroma-free system that supports efficient T cell differentiation without using mouse-derived feeder cells. Such a strategy based on immobilized Notch ligands has recently been employed to induce the iPSC-derived CD34+ HSPCs to differentiate into CD3+TCRαβ+CD8αβ T cells that are immunophenotypically similar to our iPSC-SF-T cells (Iriguchi et al., 2021; Trotman-Grant et al., 2021). However, whether such stroma-free differentiation could support normal TCR rearrangement remained unclear. Here we show that the stroma-free system can faithfully recapitulate T cell development by differentiating non-T cell-derived iPSCs (without pre-rearranged TCRs) into T cells with a high degree of TCR diversity. Compared to iPSC-OP9-T cells, iPSC-SF-T cells exhibit a marginally more mature phenotype, similar to T cells differentiated from CB CD34+ HSPCs. Moreover, by avoiding the cumbersome co-culture with mouse feeder cells, the stroma-free protocol minimizes batch-to-batch variation that can confound phenotypic characterization. Leveraging this stroma-free differentiation platform, we further demonstrate that repression of EZH1 expression during lymphoid specification facilitates T cell differentiation from human iPSCs and leads to robust generation of developmentally mature iPSC-derived T cells. Importantly, while iPSC-SF-T cells exhibit some innate-like phenotypes that have been previously reported in OP9-stroma dependent iPSC differentiation systems (Themeli et al., 2013), EZ-T cells display molecular signatures resembling peripheral blood TCRαβ T cells. These results are in agreement with the hypothesis that EZH1 knockdown produces definitive progenitors that preferentially support adult-like lymphopoiesis rather than the generation of immature primitive embryonic lymphoid cells. Such a mechanism has also been supported by recent findings that hPSC-derived CD34+ progenitors with a primary phenotype, defined by restricted hematopoietic potential, produce fetal-like NK cells via in vitro differentiation (Dege et al., 2020). In contrast, the multipotent CD34+ progenitors with full lymphoid potential are capable of giving rise to adult-like NK cells that are functionally distinct from their fetal counterparts (Dege et al., 2020).

Another focus of our study was to test the impact of EZH1 repression on the functional properties of iPSC-derived T cells and to evaluate the potential of using EZ-T cells for adoptive T cell immunotherapy. We engineered iPSC-derived T cells with anti-CD19 CARs and assessed their antitumor capacities. Compared to CAR T cells generated from iPSC-SF-T cells, CD19-CAR EZ-T cells exhibit superior antitumor activity measured by tumor cell killing and cytokine production against different types of CD19+ tumor cells in vitro, and elicit more efficient tumor clearance in a xenograft mouse model. Notably, scRNA-seq analysis revealed that EZ-T cells, after activation, give rise to a subset of T cells that express relatively low levels of cytotoxicity genes and high levels of memory T cell signature genes. Such an observation is consistent with previous findings that in vitro T cell stimulation allows faster effector/memory commitment than physiological T cell differentiation/expansion (Li and Kurlander, 2010; McLellan and Ali Hosseini Rad, 2019). Trajectory analyses based on the activity of GRNs also identified transcriptional regulators that drive the conversion of naive-like EZ-T cells into memory-like cells. Among these networks are BATF, IRF4/9, and RUNX3, all of which are known to promote T cell longevity or prevent exhaustion (Martinet et al., 2015; Huber et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018b; Istaces et al., 2019; Seo et al., 2021). This is of particular interest because a growing body of evidence has shown that enrichment of memory T cells rather than terminally differentiated effector cells correlates with superior T cell persistence and improved clinical outcomes in adoptive T cell therapies (Gattinoni et al., 2005; Klebanoff et al., 2005; Stark et al., 2009; Fraietta et al., 2018b; Fraietta et al., 2018a). Therefore, the presence of a memory-like T cell subset may contribute to the enhanced persistence and antitumor activity of EZ-T cells in the DLBCL model.

New cell engineering strategies have profoundly changed the paradigm of CAR T cell therapy. Multiple studies have generated CAR T cells with disrupted endogenous TCR to avoid the risk of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) inherent in allogeneic T cell therapy (MacLeod et al., 2017; Eyquem et al., 2017; Georgiadis et al., 2018). Recent success in producing hypoimmunogenic iPSCs that can evade immune rejection has further enhanced the prospects for off-the-shelf, universal iPSC-derived CAR T cells (Han et al., 2019; Deuse et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021). Given the fact that our stroma-free system produces iPSC-derived T cells expressing a highly diverse TCR repertoire, genetic ablation of the endogenous TCR will be required before allogeneic transplantation. Compared to primary T cells, iPSCs are more amenable to genetic manipulations and could facilitate the engineering of "armored" CAR T cells that can secrete specific cytokines or checkpoint inhibitor antibodies to overcome the suppressive tumor microenvironment (Pegram et al., 2015; Adachi et al., 2018; Rafiq et al., 2018). In addition to T cell-based immunotherapies, NK cells have also shown great promise in the treatment of both blood and solid tumors, and are currently being tested in multiple clinical trials (Basar et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021). Compared to T cells, NK cell cytotoxicity is not constrained by MHC recognition and could target tumor cells that are resistant to T cell killing. Moreover, NK cells are less prone to GVHD and CAR-associated toxicity (Ruggeri et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2020). Multiple studies have successfully generated iPSC-derived NK cells that elicit antitumor activities (Knorr et al., 2013; Zeng et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018; Woan et al., 2021). How EZH1-mediated regulation of lymphoid commitment might affect NK cell differentiation from iPSCs remains an open question.

Limitations of the study

Although our data suggest that EZ-T cells show comparable efficacy to donor-derived CAR T cells, there are limitations to be addressed in future studies. First, iPSC-derived EZ-T cells produced by existing methods predominantly consist of CD8 cytotoxic T cells. Therefore, new strategies are needed to enable the efficient production of mature CD4 SP T cells, since a more balanced ratio of cytotoxic vs. helper T cells has been associated with improved therapeutic responses (Sommermeyer et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018a). Second, our current methods for repressing EZH1 activity during T cell differentiation employ viral vectors that integrate into host DNA. Though EZH1/2 dual inhibitors have been shown to promote NK cell development (Damele et al., 2021), small molecule treatment fails to phenocopy shRNA-mediated EZH1 knockdown during iPSC-T cell differentiation. This is consistent with previous findings that EZH1/EZH2 double knockdown had no effects on T cell potential (Vo et al., 2018). Given the lack of EZH1 specific inhibitors that do not repress EZH2 function, the development of non-integrating gene knockdown strategies will be needed to facilitate translation and clinical applications of EZ-T cells.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, George Q. Daley (George.Daley@childrens.harvard.edu).

Materials availability

Plasmids/reagents generated in this study will be made available upon request.

Data and code availability

Single-cell and bulk RNA-seq data have been deposited at GEO and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-human CD45RA BV510 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#BDB563031 |

| Anti-human CD45RO PE | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#BDB555493 |

| Anti-human CCR7 APC | BD Bioscience | Cat#566762 |

| Anti-human CD3 PE/cy7 | Biolegend | Cat#344816 |

| Anti-human CD8 BV421 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#BDB562428 |

| Anti-human TCRαβ APC | Biolegend | Cat#306717 |

| Anti-human TCRγδ PE | Biolegend | Cat#331209 |

| Anti-human CD7 PE | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#BDB555361 |

| Anti-human CD5 BV510 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#BDB563381 |

| Anti-human CD4 PE/cy5 | Biolegend | Cat#555348 |

| Anti-human CD8beta APC | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat#130-110-569 |

| Anti-human CD45 APC/cy7 | Fisher Scientific | Cat#BDB557833 |

| Anti-human CD279 BV421 | BD Bioscience | Cat#566762 |

| Anti-human CD366 APC | BD Bioscience | Cat#345011 |

| Anti-human CD223 PE | BD Bioscience | Cat#565617 |

| Anti-human CD107a PE | Biolegend | Cat#328608 |

| Anti-human CD69 APC | Biolegend | Cat#310910 |

| Anti-human CD33 APC | Biolegend | Cat#303407 |

| Anti-human EZH1 | Abcam | Cat#ab64850 |

| Anti-human TBP | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#85155 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Anti-CD19 CAR lentivirus | Maus lab | N/A |

| Biological samples | ||

| Mouse embryonic fibroblast feeder cells | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#a34181 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| DMEM/F12 | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat#36254 |

| FBS | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#353046 |

| KnockOut serum replacement | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#10828028 |

| StemSpan SFEMII | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat##09605 |

| StemPro-34 SFM | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#10639011 |

| StemFlex media | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A3349401 |

| BIT serum substitute | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat#09500 |

| Gentle cell dissociation reagent | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat#100-0485 |

| rhVCAM-1 | R&D Systems | Cat#862-VC-100 |

| SB431542 | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat#72234 |

| CHIR99021 | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat#72054 |

| bFGF | Gemini | Cat#300-112p |

| VEGF | R&D Systems | Cat#293-VE-500 |

| BMP4 | R&D Systems | Cat#314-BP-500 |

| IL-6 | Peprotech | Cat#200-06 |

| IL-11 | Peprotech | Cat#200-11 |

| IGF-1 | Peprotech | Cat#100-11 |

| SCF | R&D Systems | Cat#255-SC-200 |

| EPO | Life Technologies | Cat#PHC9634 |

| FLT3 | R&D Systems | Cat#308-FK-250 |

| TPO | Peprotech | Cat#300-18 |

| IL-3 | Peprotech | Cat#200-03 |

| rhDLL1/DLL4-Fc | Invitrogen | Cat#A42510 |

| IL-7 | R&D Systems | Cat#207-IL-010 |

| IL-15 | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat#78031 |

| ImmunoCult human CD3/CD28 T cell activator | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat#10971 |

| VivoGlo Luciferin | Promega | Cat#P1041 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Embryoid Body Dissociation Kit | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat#130-096-348 |

| CD34 MicroBead Kit | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat#130-046-702 |

| LEGENDplex Hu Th1/Th2 Panel | BioLegend | Cat#741030 |

| Bright-Glo Luciferase Assay System | Promega | Cat#E2610 |

| Maxima cDNA Sythesis Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#FERK1641 |

| RNeasy Plus Micro Kit | QIAGEN | Cat# 74034 |

| Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 4367659 |

| DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit | Qiagen | Cat# 69504 |

| Human TCRB ImmunoSEQ Assay | Adaptive Biotechnologies | N/A |

| Deposited data | ||

| Raw and processed RNA-seq data | This paper | GEO: GSE195667 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| Human 1157.2 iPSCs | Daley lab | N/A |

| Human 273 iPSCs | BCH Stem Cell Core | N/A |

| Human 1381.3 iPSCs | BCH Stem Cell Core | N/A |

| Jeko-1 cells | Maus lab | N/A |

| OCI-Ly1 cells | Daley lab | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| NOD-scid IL2Rgammanull (NSG) mice | Jackson Laboratories | Cat# 005557 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| EZH1 CRISPRi gRNA: GGTGAGTGAGTAAACAAGCC | Broad Institute | Addgene#92385 |

| DNTT forward primer: 5'-CAGAGCGTTCCTCATGGAGCTG-3' | ORIGENE | Cat#HP233227 |

| DNTT reverse primer: 5'-GTGCTTGAAGCCACTCCAGAAC-3' | ORIGENE | Cat#HP233227 |

| EZH1 forward primer: 5'-CACCACATAGTCAGTGCTTCCTG-3' | Integrated DNA Technologies | N/A |

| EZH1 reverse primer: 5'-AGTCTGACAGCGAGAGTTAGCC-3' | Integrated DNA Technologies | N/A |

| EZH2 forward primer: 5'-GACCTCTGTCTTACTTGTGGAGC-3' | ORIGENE | Cat#HP207764 |

| EZH2 reverse primer: 5'-CGTCAGATGGTGCCAGCAATAG-3' | ORIGENE | Cat#HP207764 |

| GAPDH forward primer: 5'-ACCCAGAAGACTGTGGATGG-3' | Integrated DNA Technologies | N/A |

| GAPDH reverse primer: 5'-TTCAGCTCAGGGATGACCTT-3' | Integrated DNA Technologies | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| CROPseq-EZH1gRNA-Zeo plasmid | This paper | N/A |

| PB03-NDI-dCAS9-KRAB plasmid | This paper | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| immunoSEQ Analyzer 3.0 | Adaptive Biotechnologies | https://www.immunoseq.com/analyzer/ |

| R | R | https://www.r-project.org/ |

| CellRouter | Lummertz da Rocha et al., 2018 | https://github.com/edroaldo/cellrouter |

| R package FUSCA | Lummertz da Rocha et al., 2022 | https://github.com/edroaldo/fusca |

| Symphony | Kang et al., 2021 | https://github.com/immunogenomics/symphony |

| GraphPad Prism v8 | Graphpad Software, Inc | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| FlowJo 10.8.0 | BD Bioscience | https://www.flowjo.com/ |

| GSEA | Broad Institute | https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp |

| Aura imaging software | Spectral Instruments Imaging | https://spectralinvivo.com/aura-imaging-software/ |

| BioRender | BioRender | https://biorender.com/ |

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell line

Human 1157.2 iPSCs established by the Stem Cell Core at Boston Children's Hospital were maintained on Matrigel matrix (Corning, 354277) using Stemflex media (Gibco, A3349401) in 5% CO2 at 37° C.

In vivo tumor xenograft model

NOD-scid IL2Rgammanull (NSG) mice (Jackson Laboratories, 005557) were housed at the Boston Children's Hospital animal care facility following institutional guidelines. 8 to 12-week-old male and female mice were intravenously injected with 1x106 OCI-Ly1 DLBCL tumor cells expressing green firefly luciferase. The inoculated animals were subjected to bioluminescence imaging (BLI) using the IVIS 200 system (PerkinElmer) twice per week following intraperitoneal injections of Vivoglo luciferin (Promega, P1043) at 150mg/kg body weight. After two weeks, animals with substantial tumor cell engraftment (Mean total flux > 5x105 photons/sec) were randomly assigned into four groups and intravenously injected with PBS (untreated) or 2x106CAR T cells generated from control iPSC-SF-T, iPSC-EZ-T, or PBMC-T cells. Tumor burden was measured by BLI weekly, and images were processed and analyzed using Aura imaging software (Spectral Instruments Imaging). To monitor CAR T cell persistence, peripheral blood cells were collected via retro-orbital bleeding after 3 weeks of T cell injections, and absolute numbers of CAR T cells were determined by flow cytometry analysis. All animal experiments were performed under protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Boston Children's Hospital.

METHODS DETAILS

Culture of iPSCs and generation of CD34+ HE

Human 1157.2 iPSCs were maintained on Matrigel-coated plates using Stemflex media (Gibco, A3349401) and transferred to mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) feeder cells (Gibico, A34181) prior to differentiation. After one week of culture of on MEFs, iPSCs were collected for the generation CD34+ HE cells using a previous described protocol (Ditadi et al., 2015). Briefly, iPSC colonies were scraped and transferred to ultra-low attachment plates and cultured with aggregation media contains BMP4 (10ng/ml, day 0-2), bFGF (5ng/ml, day 1-2), CHIR99021 (3μM, day 2), and SB431542 (6μM, day2) to allow EB formation. From day 4, EBs were cultured with StemPro-34 media (Gibco, 10639011) supplemented with VEGF (15ng/ml, day3-8), bFGF (5ng/ml, day3-8), SCF (50ng/ml, day 6-8), EPO (day6-8), IL-6 (day6-8), IL-11 (day6-8), and IGF-1 (day6-8). After 8 days of culture, EBs were dissociated using EB Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi, 130096348), and HE cells were isolated by magnetic-activated cell sorting (MSCS) using the human CD34 Microbead Kit (Miltenyi, 130046702).

Differentiation of iPSCs into T cells

24 well non-tissue culture treated plates were coated with 10μg/ml recombinant human DLL4-Fc protein (Life Technologies, A42510) and 2 μg/ml VCAM-1 (Shukla et al., 2017) (R&D, 862VC100) in PBS for 2 hours at 4°C. CD34+ HE cells (1X105 cells/well) were then seeded on DLL4-coated plates and cultured in SFEMII (StemCell Tech, 09605) media supplemented with 10% BIT serum substitute (StemCell Tech, 09500), 2mM L-Glutamine (Gibco, 35050061), 1mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco, 11360070), 50μg/ml 2-phospho-L-ascorbic acid (Huijskens et al., 2014) (sigma, 49752), 55μM 2-Mercaptoethanol (Gibco, 21985023), 1mM None-essential amino acids (Gibco, 11140050), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Corning, 30002CI), 30ng/ml SCF, 20ng/ml FLT3, 30ng/ml IL-7, 5ng/ml IL-3 (first week only), and 5ng/ml TPO for 2 weeks to induced the differentiation into proT cells. For the production of EZ-T cells, EZH1 knockdown was performed via lentiviral transduction (MOI=5) after 24 hours of HE seeding. After 2 weeks of differentiation, SCF and TPO were withdrawn from the media, and the proT cells were replated into new DLL4-coated plates and cultured in the presence of 20ng/ml FLT3 and 15ng/ml IL-7 till week 5, followed by 1 week of treatment with CD3/CD28 T activator (StemCell Tech, 10971) and 5ng/ml IL-15 to induced SP T cells. During T cell differentiation, half media changes were conducted every 2-3 days. T cell differentiation using the OP9-DL1 co-culture system was conducted following previous reports (Holmes and Zúñiga-Pflücker, 2009; Themeli et al., 2013). Briefly, day 8 CD34+ HE cells were seeded on OP-DL1 stromal cells and co-cultured with OP9 media (α-MEME, 20% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1mM None-essential amino acids, 2mM L-Glutamine, 10μM 2-Mercaptoethanol, 50μg/ml 2-phospho-L-ascorbic acid) supplemented with 10ng/ml SCF, 5ng/ml FLT3, and 10ng/ml IL-7. Cells were mechanically dissociated and filtered through 40μm strainers to be seeded on new stromal cells every five days.

CRISPR interference in iPSs

gRNA targeting the TSS of EZH1 was pulled from the Broad Institute’s genome-wide Dolcetto library (Addgene #92385, Library Set A) (Sanson et al., 2018) and ordered as oligos from IDT. gRNA oligos (GGTGAGTGAGTAAACAAGCC) were annealed, phosphorylated and cloned by Golden Gate Assembly with BsmBI into a modified CROPseq-Zeo vector constitutively expressing mNeon and a modified gRNA scaffold sequence as previously described (Dang et al., 2015). Lentiviruses for each gRNA vector was generated by transfection of pMD2.G (Addgene #12259), psPAX2 (Addgene #12260), and the successfully cloned CROPseq transfer plasmid (2:3:4 ratio by mass and 3ug total plasmid) into HEK293FT cells using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher L3000015). Viral supernatant was harvested 48 hours after transfection and filtered through 0.45 μm PVDF filters (Millipore SLHVR04NL). Human 1157.2 iPSC line expressing a doxycycline-inducible dCas9-KRAB-2A-mCherry cassette (from Boston Children's Hospital Stem Cell Core) were singularized with TrypLE, plated in a matrigel-coated 6-well plate at 165,000 cells per well, and then infected with individual CROPseq lentiviruses at MOI=0.25 with 8ug/mL polybrene. The following day the media was replenished and the cells were selected with 200 μg/mL zeocin (ThermoFisher R25001) for 24 hours. Selected hiPSCs were scaled up, banked, and used for downstream differentiation.

Immunoblot

Whole cell lysates were collected using NP-40 lysis buffer (Invitrogen, FNN0021) with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific, 78443). 50μg total protein was separated by SDS–PAGE using Any kD™ Mini-protean TGX precast polyacrylamide gels (BioRad, 4569033), and transferred to PVDF membranes using the Trans-Blot Cell Transfer System (BioRad). Membranes were incubated overnight with antibodies against TBP (Cell Signaling, 85155, 1:1000), EZH1 (Abcam, ab64850, 1:1000) at 4°C, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:2000) for 1 hour at room temperature. Chemiluminescence was detected using SuperSignal West Pico Plus Chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific, 34579).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR analysis

RNA extraction and removal of genomic DNA was performed using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, 74104). First strand cDNA was synthesized using Maxiam First Strand cDNA SynthesisKit (Thermo Scientific, K1641). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on a QuantStudio 7 Flex Real-Time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems, 4485701) using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, 4367659) following the manufacturer’s directions. The following oligonucleotides were used: DNTT forward primer: 5'-CAGAGCGTTCCTCATGGAGCTG-3'; DNTT reverse primer: 5'-GTGCTTGAAGCCACTCCAGAAC-3'; EZH1 forward primer: 5'-CACCACATAGTCAGTGCTTCCTG-3'; EZH1 reverse primer: 5'-AGTCTGACAGCGAGAGTTAGCC-3'; GAPDH forward primer: 5'-ACCCAGAAGACTGTGGATGG-3'; GAPDH reverse primer: 5'-TTCAGCTCAGGGATGACCTT-3'; EZH2 forward primer: 5'-GACCTCTGTCTTACTTGTGGAGC-3'; EZH2 reverse primer: 5'-CGTCAGATGGTGCCAGCAATAG-3'.

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained with PI/DAPI (BD Biosciences, RUO) and antibodies at 1:100 dilution in PBS with 2% FBS for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. BD LSRII and BD FACSAria II were used for flow cytometry analysis and cells sorting. Compensation was performed by automated compensation with anti-mouse Igk and negative beads (BD Biosciences) using the BD FACSDiva software. The following human antibodies were used: CD45RA-BV510 (BD Biosciences, H100), CD45RO-PE (BD Biosciences, UCHL1), CCR7-APC (BD Biosciences, 2-L1-A), CD3-PE/Cy7 (Biolegend, SK7), CD8α-BV421 (BD Biosciences, RPA-T8), TCRαβ-APC (Biolegend, IP26), TCRγδ-PE (Biolegend, B1), CD7-PE (BD Biosciences, M-T701), CD5-BV510 (BD Biosciences, UCHT2), CD4-PE/Cy5 (Biolegend, RPA-T4), CD8β-APC (Miltenyi, REA715), CD45-APC/Cy7 (BD Biosciences, 2D1), CD279-BV421 (BD Biosciences, EH12.1), CD366-APC (BD Biosciences, F38-2E2), CD223-PE (BD Biosciences, T47-530), CD107a-PE (Biolegend, LAMP-1), CD69 APC (Biolegend, FN50), CD33-APC (Biolegend, WM53).

Bulk RNA-seq and data analysis

Total RNA samples were isolated from iPSC-derived CD3+ cells or PBMC NK/T cells using a column assay with the DNase treatment (Direct-zol MicroPrep, ZYMO). Quantity and quality of the RNA were evaluated using the nanodrop machine and RNA screen tape. High quality RNA (Both 280/260 and 230/260 over 1.7 with RNA integrity number >7) underwent ribosomal RNA depletion and then library construction. For regular gene expression analysis, adaptor trimmed reads from the sequencer were mapped to the human genome, quantified, and analyzed using seq data analysis tools (Cutadapt, Bowtie, TopHat, HTSeq, R, and edgeR). The RNA-seq data is available in GEO database (GSE195667). Portions of this research were conducted on the O2 High Performance Compute Cluster, supported by the Research Computing Group, at Harvard Medical School.

TCR repertoire analysis

CD3+ T cells were FACS-isolated from control PBMC T cells or iPSC-derived T cells, followed by gDNA extraction using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, 69504). DNA samples were then subjected TCRB sequencing via immunoSEQ assay. (Adaptive Biotechnologies). TCR rearrangements, Vβgene usage, and CDR3 length were analyzed using the immunoSEQ Analyzer 3.0 software (Adaptive Biotechnologies).

Single-cell RNA-Sequencing and data analysis

T cells were FACS-isolated for DAPI-CD45+ expression following in vitro differentiation and/or activation. Single-cell suspensions were loaded onto a Chromium Single Cell Chip (10X Genomics) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for a target recovery of ~6000 cells per lane. Each sample was loaded into two lanes to serve as technical replicates for scRNA-Seq library preparation. Libraries were then prepared per the 10X scRNA-Seq v2 protocol in parallel for all conditions. Final 10X scRNA-Seq libraries were assayed via an Agilent High Sensitivity dsDNA Bioanalyzer, normalized, pooled and shallow sequenced on a MiniSeq to quantify the number of high confidence cell barcodes. The libraries were then renormalized per the distribution of reads/library from the MiniSeq run and deep sequenced on a NextSeq to a depth of 50,000 reads per cell barcode.

Sequencing libraries were computationally demultiplexed and the data were aligned to the GRCh38 reference genome using cellranger v2.1 (10X Genomics). CellRouter was used for quality control and downstream analysis (Lummertz da Rocha et al., 2018). Cell by gene count matrices of all samples were combined to a single gene expression matrix. Cells with 500–3000 detected genes and expressing <10% mitochondrial genes as well as genes expressed in > 25 cells were retained for downstream analysis. The final dataset after quality control was composed of 10907 cells, with a median of 1,456 genes detected per cell. Variation caused by mitochondrial gene expression and sample replicates were regressed out. All genes passing QC metrics were used for principal component analysis. Clustering analysis was performed using parameters k=150 and 30 principal components. UMAP analysis was performed using 10 principal components. Cluster annotation was performed using differential expression and marker genes. Gene signatures, as well as ranked gene lists ordered by log fold change for GSEA analysis, were generated by testing for differential expression of a cluster/cell type against all other cells using a Wilcox test, as implemented in CellRouter. Trajectory analysis and calculation of GRN scores was performed with CellRouter. SCENIC analysis was used to identify regulons enriched in each annotated cell type (Aibar et al., 2017). Data generated by Granja et al. (Granja et al., 2019) were downloaded from https://github.com/GreenleafLab/MPAL-Single-Cell-2019 and converted into a FUSCA object (Lummertz da Rocha et al., 2022). We used FUSCA to perform UMAP analysis and prepare input parameters for reference mapping using Symphony (Kang et al., 2021).

T cell activation and degranulation

Control T cells generated from primary PBMC T cells of heathy donors and iPSC-T cells were treated with T cell stimulation cocktail (Invitrogen, 00497093) containing phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and ionomycin for 6 hours. Percentage of iPSC cells that express CD3 and CD69 was measured by flow cytometry to determine T cell activation. Similarly, percentage of CD8+CD3+ iPSC cells that express CD107a was measured by flow cytometry to detect T cell degranulation.

CAR T cell functional assays

Control PBMC T cells and iPSC-derived T cells were activated (day 0) using anti-CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (Gibco, 11131D) or CD3/CD28 T activator (StemCell Tech, 10971), followed by transduction with a lentiviral vector encoding the CD19-CAR 24-hours later (Scarfò et al., 2018). T cells were cultured in RPMI media containing 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin, streptomycin and supplemented with 20 IU/ml rhIL-2 beginning on day 0 of culture and were maintained at a constant cell concentration of 0.5 x106/mL by counting every 2-3 days. On day 10 cells were de-beaded (when using Dynabeads) and used for assays. For cytotoxicity assays, control PBMC or iPSC-T cells were co-cultured with luciferase-expressing Jeko-1 or OCI-Ly1 tumor cells at the indicated ratios for 18 hours. Luciferase activity was measured with a Synergy Neo2 luminescence microplate reader (Biotek). Percentage of specific lysis was calculated as (total RLU / target cells only RLU) x100. Cell-free supernatants were collected for cytokine release assay. Levels of cytokines were measured using a LEGENDplex Multiplex Assay Kit (Biolegend, 741030) following manufacture's instructions.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The significance of the difference between control and experimental results generated from in vitro assays was determined by two tailed student's T test, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For in vivo experiments, survival results were presented in a Kaplan-Meier survival plot and compared by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Statistic parameters in each experiment (value of n, SEM, or SD) are described in the figure legends.

Supplementary Material

Table S1 Differentially expressed genes between control and EZH1 knockdown iPSC-derived αβ T cells. Related to Fig. 3.

Highlights:

Stroma-free differentiation of iPSCs into T cells expressing diverse TCRs

EZH1 repression generates mature EZ-T cells similar to peripheral blood αβ T cells

EZ-T cells can give rise to memory-like T cells upon activation.

CAR EZ-T cells display enhanced antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Boston Children's Hospital Flow Cytometry Core and the hESC Core Facility. We also thank John Atwater, Merve Akyol, and Tamer Onder for assistance with experiments and advice. This study was supported by grants from NIH NHLBI U01HL134812 (GQD), NIH NIDDK 2U01DK104218 (GQD), NIH NHLBI 5U24HL134763 subaward 1701192 (RJ), and Emerson Collective Cancer Research Fund (GQD).

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

R.J., G.Q.D., and Boston Children’s Hospital hold intellectual property and receive consulting fees and/or hold equity interest relevant to the generation of iPSC-derived T cells. T.M.S. receives sponsored research support from Elevate Bio. G.Q.D. is a member of Cell Stem Cell's advisory board.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Adachi K, Kano Y, Nagai T, Okuyama N, Sakoda Y, and Tamada K (2018) IL-7 and CCL19 expression in CAR-T cells improves immune cell infiltration and CAR-T cell survival in the tumor. Nat Biotechnol, 36, 346–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aibar S, González-Blas CB, Moerman T, Huynh-Thu VA, Imrichova H, Hulselmans G, Rambow F, Marine JC, Geurts P, Aerts J et al. (2017) SCENIC: single-cell regulatory network inference and clustering. Nat Methods, 14, 1083–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin TA, Sandau MM, Jameson SC, and Hogquist KA (2005) The timing of TCR alpha expression critically influences T cell development and selection. J Exp Med, 202, 111–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basar R, Daher M, and Rezvani K (2020) Next-generation cell therapies: the emerging role of CAR-NK cells. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program, 2020, 570–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosselut R, Kubo S, Guinter T, Kopacz JL, Altman JD, Feigenbaum L, and Singer A (2000) Role of CD8beta domains in CD8 coreceptor function: importance for MHC I binding, signaling, and positive selection of CD8+ T cells in the thymus. Immunity, 12, 409–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahan P, Li H, Morris SA, Lummertz da Rocha E, Daley GQ, and Collins JJ (2014) CellNet: network biology applied to stem cell engineering. Cell, 158, 903–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CW, Lai YS, Lamb LS, and Townes TM (2014) Broad T-cell receptor repertoire in T-lymphocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One, 9, e97335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen QY, Li YN, Wang XY, Zhang X, Hu Y, Li L, Suo DQ, Ni K, Li Z, Zhan JR et al. (2020) Tumor Fibroblast-Derived FGF2 Regulates Expression of SPRY1 in Esophageal Tumor-Infiltrating T Cells and Plays a Role in T-cell Exhaustion. Cancer Res, 80, 5583–5596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheroutre H, and Lambolez F (2008) Doubting the TCR coreceptor function of CD8alphaalpha. Immunity, 28, 149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damele L, Amaro A, Serio A, Luchetti S, Pfeffer U, Mingari MC, and Vitale C (2021) EZH1/2 Inhibitors Favor ILC3 Development from Human HSPC-CD34. Cancers (Basel), 13, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang Y, Jia G, Choi J, Ma H, Anaya E, Ye C, Shankar P, and Wu H (2015) Optimizing sgRNA structure to improve CRISPR-Cas9 knockout efficiency. Genome Biol, 16, 280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dege C, Fegan KH, Creamer JP, Berrien-Elliott MM, Luff SA, Kim D, Wagner JA, Kingsley PD, McGrath KE, Fehniger TA et al. (2020) Potently Cytotoxic Natural Killer Cells Initially Emerge from Erythro-Myeloid Progenitors during Mammalian Development. Dev Cell, 53, 229–239.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuse T, Hu X, Gravina A, Wang D, Tediashvili G, De C, Thayer WO, Wahl A, Garcia JV, Reichenspurner H et al. (2019) Hypoimmunogenic derivatives of induced pluripotent stem cells evade immune rejection in fully immunocompetent allogeneic recipients. Nat Biotechnol, 37, 252–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditadi A, Sturgeon CM, Tober J, Awong G, Kennedy M, Yzaguirre AD, Azzola L, Ng ES, Stanley EG, French DL et al. (2015) Human definitive haemogenic endothelium and arterial vascular endothelium represent distinct lineages. Nat Cell Biol, 17, 580–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doulatov S, Vo LT, Chou SS, Kim PG, Arora N, Li H, Hadland BK, Bernstein ID, Collins JJ, Zon LI et al. (2013) Induction of multipotential hematopoietic progenitors from human pluripotent stem cells via respecification of lineage-restricted precursors. Cell Stem Cell, 13, 459–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egawa T, Kreslavsky T, Littman DR, and von Boehmer H (2008) Lineage diversion of T cell receptor transgenic thymocytes revealed by lineage fate mapping. PLoS One, 3, e1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyquem J, Mansilla-Soto J, Giavridis T, van der Stegen SJ, Hamieh M, Cunanan KM, Odak A, Gönen M, and Sadelain M (2017) Targeting a CAR to the TRAC locus with CRISPR/Cas9 enhances tumour rejection. Nature, 543, 113–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fesnak A, Lin CY, Siegel DL, and Maus MV (2016a) CAR-T cell therapies from the transfusion medicine perspective. Transfusion medicine reviews, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fesnak AD, June CH, and Levine BL (2016b) Engineered T cells: the promise and challenges of cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer, 16, 566–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraietta JA, Lacey SF, Orlando EJ, Pruteanu-Malinici I, Gohil M, Lundh S, Boesteanu AC, Wang Y, O’Connor RS, Hwang WT et al. (2018a) Determinants of response and resistance to CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat Med, 24, 563–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraietta JA, Nobles CL, Sammons MA, Lundh S, Carty SA, Reich TJ, Cogdill AP, Morrissette JJD, DeNizio JE, Reddy S et al. (2018b) Disruption of TET2 promotes the therapeutic efficacy of CD19-targeted T cells. Nature, 558, 307–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattinoni L, Klebanoff CA, Palmer DC, Wrzesinski C, Kerstann K, Yu Z, Finkelstein SE, Theoret MR, Rosenberg SA, and Restifo NP (2005) Acquisition of full effector function in vitro paradoxically impairs the in vivo antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells. J Clin Invest, 115, 1616–1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiadis C, Preece R, Nickolay L, Etuk A, Petrova A, Ladon D, Danyi A, Humphryes-Kirilov N, Ajetunmobi A, Kim D et al. (2018) Long Terminal Repeat CRISPR-CAR-Coupled “Universal” T Cells Mediate Potent Anti-leukemic Effects. Mol Ther, 26, 1215–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good CR, Aznar MA, Kuramitsu S, Samareh P, Agarwal S, Donahue G, Ishiyama K, Wellhausen N, Rennels AK, Ma Y et al. (2021) An NK-like CAR T cell transition in CAR T cell dysfunction. Cell, 184, 6081–6100.e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granja JM, Klemm S, McGinnis LM, Kathiria AS, Mezger A, Corces MR, Parks B, Gars E, Liedtke M, Zheng GXY et al. (2019) Single-cell multiomic analysis identifies regulatory programs in mixed-phenotype acute leukemia. Nat Biotechnol, 37, 1458–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Wang M, Duan S, Franco PJ, Kenty JH, Hedrick P, Xia Y, Allen A, Ferreira LMR, Strominger JL et al. (2019) Generation of hypoimmunogenic human pluripotent stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 116, 10441–10446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harberts A, Schmidt C, Schmid J, Reimers D, Koch-Nolte F, Mittrücker HW, and Raczkowski F (2021) Interferon regulatory factor 4 controls effector functions of CD8. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 118, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holler PD, and Kranz DM (2003) Quantitative analysis of the contribution of TCR/pepMHC affinity and CD8 to T cell activation. Immunity, 18, 255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes R, and Zúñiga-Pflücker JC (2009) The OP9-DL1 system: generation of T-lymphocytes from embryonic or hematopoietic stem cells in vitro. Cold Spring Harb Protoc, 2009, pdb.prot5156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber M, Suprunenko T, Ashhurst T, Marbach F, Raifer H, Wolff S, Strecker T, Viengkhou B, Jung SR, Obermann HL et al. (2017) IRF9 Prevents CD8+ T Cell Exhaustion in an Extrinsic Manner during Acute Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus Infection. J Virol, 91, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huijskens MJ, Walczak M, Koller N, Briedé JJ, Senden-Gijsbers BL, Schnijderberg MC, Bos GM, and Germeraad WT (2014) Technical advance: ascorbic acid induces development of double-positive T cells from human hematopoietic stem cells in the absence of stromal cells. J Leukoc Biol, 96, 1165–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huster KM, Busch V, Schiemann M, Linkemann K, Kerksiek KM, Wagner H, and Busch DH (2004) Selective expression of IL-7 receptor on memory T cells identifies early CD40L-dependent generation of distinct CD8+ memory T cell subsets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 101, 5610–5615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intlekofer AM, Takemoto N, Wherry EJ, Longworth SA, Northrup JT, Palanivel VR, Mullen AC, Gasink CR, Kaech SM, Miller JD et al. (2005) Effector and memory CD8+ T cell fate coupled by T-bet and eomesodermin. Nat Immunol, 6, 1236–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iriguchi S, Yasui Y, Kawai Y, Arima S, Kunitomo M, Sato T, Ueda T, Minagawa A, Mishima Y, Yanagawa N et al. (2021) A clinically applicable and scalable method to regenerate T-cells from iPSCs for off-the-shelf T-cell immunotherapy. Nat Commun, 12, 430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Istaces N, Splittgerber M, Lima Silva V, Nguyen M, Thomas S, Le A, Achouri Y, Calonne E, Defrance M, Fuks F et al. (2019) EOMES interacts with RUNX3 and BRG1 to promote innate memory cell formation through epigenetic reprogramming. Nat Commun, 10, 3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- June CH, O’Connor RS, Kawalekar OU, Ghassemi S, and Milone MC (2018) CAR T cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Science, 359, 1361–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JB, Nathan A, Weinand K, Zhang F, Millard N, Rumker L, Moody DB, Korsunsky I, and Raychaudhuri S (2021) Efficient and precise single-cell reference atlas mapping with Symphony. Nat Commun, 12, 5890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanoff CA, Gattinoni L, Torabi-Parizi P, Kerstann K, Cardones AR, Finkelstein SE, Palmer DC, Antony PA, Hwang ST, Rosenberg SA et al. (2005) Central memory self/tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells confer superior antitumor immunity compared with effector memory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 102, 9571–9576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knorr DA, Ni Z, Hermanson D, Hexum MK, Bendzick L, Cooper LJ, Lee DA, and Kaufman DS (2013) Clinical-scale derivation of natural killer cells from human pluripotent stem cells for cancer therapy. Stem Cells Transl Med, 2, 274–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar BV, Connors TJ, and Farber DL (2018) Human T Cell Development, Localization, and Function throughout Life. Immunity, 48, 202–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]