Abstract

Background

Although a substantial increase in the survival of patients with other cancers has been observed in recent decades, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) remains one of the deadliest diseases. No effective screening approach exists.

Methods

Differential exosomal long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) isolated from the serum of patients with PDAC and healthy individuals were profiled to screen for potential markers in liquid biopsies. The functions of LINC00623 in PDAC cell proliferation, migration and invasion were confirmed through in vivo and in vitro assays. RNA pulldown, RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) and coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assays and rescue experiments were performed to explore the molecular mechanisms of the LINC00623/NAT10 signaling axis in PDAC progression.

Results

A novel lncRNA, LINC00623, was identified, and its diagnostic value was confirmed, as it could discriminate patients with PDAC from patients with benign pancreatic neoplasms and healthy individuals. Moreover, LINC00623 was shown to promote the tumorigenicity and migratory capacity of PDAC cells in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistically, LINC00623 bound to N-acetyltransferase 10 (NAT10) and blocked its ubiquitination-dependent degradation by recruiting the deubiquitinase USP39. As a key regulator of N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C) modification of mRNA, NAT10 was demonstrated to maintain the stability of oncogenic mRNAs and promote their translation efficiency through ac4C modification.

Conclusions

Our data revealed the role of LINC00623/NAT10 signaling axis in PDAC progression, showing that it is a potential biomarker and therapeutic target for PDAC.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13045-022-01338-9.

Background

While the patient survival time in some cancers has been dramatically prolonged in recent decades, the overall 5-year survival rate of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) has remained virtually unchanged [1, 2]. The lack of a reliable test for diagnosing early PDAC may account for the poor overall survival of patients with this disease, as they are usually diagnosed at an advanced stage due to a lack of or vague symptoms when the cancer is still localized [3]. Thus, it is critical to developing new approaches for diagnosing early PDAC with high specificity and sensitivity.

Exosomes are extracellular membrane vesicles with diameters ranging from 50 to 150 nm [4]. Exosomes contain proteins, lipids and RNA from donor cells and are considered key messengers in intercellular communication [5]. Recently, studies have investigated the potential use of exosomal markers derived from serum or plasma in tumor screening [6–9]. In PDAC, exosomal markers include extracellular vesicle (EV)-based protein markers, such as glypican-1 (GPC1) [10] and a five-protein signature [11]. In addition, a diagnostic signature in plasma was developed for the detection of PDAC based on EV long RNA profiling [12], suggesting that long noncoding RNA (lncRNAs) in exosomes could be promising diagnostic biomarkers.

LncRNAs comprise a large class of transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides with little or no protein-coding ability [13]. They have been considered to function as important regulators in gene expression networks by modulating mRNA stability, translation, posttranslational modification and transcription [14, 15]. By interacting with miRNAs, mRNAs, DNAs or proteins, lncRNAs contribute to various aspects of cellular homeostasis in cancer, including proliferation, survival, migration and genomic stability [16–19]. Moreover, lncRNAs can be encapsulated by exosomes released from cancer cells and transferred to recipient cells to regulate cancer progression [20–22]. Although circulating exosomal lncRNAs have shown potential as noninvasive biomarkers for detecting early-stage tumors and monitoring disease progression [7, 23–25], no circulating exosomal lncRNAs have been identified for the early detection of PDAC, and the underlying mechanisms remain to be clarified.

In this study, we profiled the differential expression of circulating exosomal lncRNAs between patients with PDAC and healthy individuals. A novel oncogenic lncRNA, LINC00623, was identified. The level of circulating exosomal LINC00623 was significantly higher in patients with PDAC than in patients with benign pancreatic neoplasms or healthy individuals. Moreover, exosomal LINC00623 exhibited a high area under the curve (AUC) in the PDAC cohort, especially in patients with normal CA19-9 levels. Elevated LINC00623 expression levels were also found to be associated with clinicopathological features and poor outcomes in patients with PDAC. Functionally, LINC00623 promotes the tumorigenicity and progression of PDAC. Mechanistically, LINC00623 protects N-acetyltransferase 10 (NAT10) from ubiquitination-dependent degradation since LINC00623 acts as a scaffold for the interaction of NAT10 with USP39. NAT10 is a predominantly nuclear protein that catalyzes almost all documented N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C) events in mRNA [26]. Among cytidine modifications in mRNA, ac4C modification remains relatively unexplored compared to two other modifications, 5-methylcytidine (m5C) and 5-hydroxymethylcytidine (hm5C) [27, 28]. Here, we also demonstrated that the LINC00623/NAT10 signaling axis remodels the landscape of mRNA ac4C modification in PDAC and increases the stability and translation efficiency of oncogenic mRNAs.

Methods

Serum and tissue sample collection

In total, 133 pairs of PDAC and adjacent normal specimens were obtained from patients who underwent pancreatectomy at Ruijin Hospital (Shanghai, China) between January 2014 and December 2017. Forty pairs of clinical samples were used for RNA extraction, while the remaining 93 pairs were paraffin-embedded and used for IHC staining. PDAC tissues used for organoid and PDX model establishment were obtained from patients with PDAC who underwent pancreatectomy at Ruijin Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. Samples were collected from patients who had not received any local or systemic treatment prior to the operation. Serum samples were collected from patients with PDAC (n = 73), chronic pancreatitis (CP, n = 5), intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs, n = 19), mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs, n = 6), pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs, n = 16) and serous cystic neoplasms (SCNs, n = 13) and from healthy individuals (n = 42) at Ruijin Hospital between March 2018 and December 2018. All individuals involved in this study provided written informed consent for the use of clinical samples in medical research. All clinical protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of Ruijin Hospital affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University (No. 121 in 2017). The clinical characteristics of the patients enrolled in this study are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Cells and cell culture

PDAC cell lines (AsPC-1, BxPC-3, CFPAC-1, MIAPaCa-2 and PANC-1), human pancreatic ductal immortalized cells (HPNE) and human embryonic kidney cells (HEK-293T) were purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). BxPC-3 and CFPAC-1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco). AsPC-1, PANC-1, MIA PaCa-2, HPNE and HEK-293T cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM (Gibco). All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco), 100 IU/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (NCM, Suzhou, China). All cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. All cells were authenticated using STR profiling and tested negative for mycoplasma contamination.

RNA extraction and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT‒qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA). The nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were extracted using a PARIS kit (Thermo Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription using a ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Kit (Toyobo, Japan). A SYBR Green PCR Kit (Toyobo, Japan) and an ABI 7900 real-time PCR Detection System (Applied Biosystems, USA) were used for RT‒qPCR analysis. All RT-qPCR assays were performed in triplicate. The primer sequences used are listed in Additional file 2: Table S2.

Plasmid construction and cell transfection

For the knockdown system, two different short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) against LINC00623 were inserted into the CMV-copGFP-T2A-puro-H1-shRNA vector (sh-623#1 and sh-623#2) (Bioegene, Shanghai, China). For the overexpression system, the dCAS9-SAM approach was adopted. Lentiviruses were produced in HEK-293T cells by cotransfecting the targeting plasmids with the packaging plasmid psPAX2 and the envelope plasmid pMD2.G. Viral supernatants were collected and passed through filters with a 0.45-μm-diameter pore (Millipore, USA) after 48 h. For the overexpression system, lentiviruses expressing lenti-dCAS-VP64, lenti-MS2-P65-HSF1 and lenti-sgRNA were constructed by Bioegene. The LINC00623 overexpression sgRNA was designed to target the sequence 5′-GGGAAGGAGAAAGTGAGACT-3′. The full-length human NAT10 and USP39 cDNA sequences were cloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector (Bioegene). Transient transfection was conducted by using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Stably transfected cells were selected with puromycin, blasticidin or hygromycin (Beyotime). The knockdown systems for NAT10 and USP39 were similar to those described above. The sequences of the shRNAs are listed in Additional file 3: Table S3.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed with RIPA buffer mixed with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (NCM). Cell lysates were separated by SDS‒PAGE on 10% gels, transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore), incubated with primary and secondary antibodies and visualized with an ECL detection system (Tanon 5200, Shanghai, China). The details of the antibodies used in this study are listed in Additional file 4: Table S4. Three independent experiments were performed.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and immunofluorescence staining (IF)

The FISH probes used in this study were designed and synthesized by RiboBio (Guangzhou, China). FISH assays and IF staining were performed according to a previously described method [29]. Briefly, for FISH, after counterstaining with DAPI (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), slides were visualized under a Leica SP8 X confocal microscope (Leica, Germany). LINC00623 expression was quantified according to the intensity of staining (0 = negative, 1 = weak, 2 = moderate, 3 = strong) and the extent of staining (1 = 0–25%, 2 = 26–50%, 3 = 51–75%, 4 = 76–100%). The intensity score and the percentage score were multiplied to generate a final score ranging from 0 to 12. Then, the samples were classified as having either high expression (score 7–12) or low expression (score 0–6). Immunofluorescence staining was performed using an anti-NAT10 antibody (1:250 dilution, sc-271770, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, USA) and an anti-USP39 antibody (1:250 dilution, ab131244, Abcam).

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining

IHC staining was performed using the standard streptavidin–biotin–peroxidase complex method. Briefly, paraffin sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated. The slides were heated for antigen retrieval for 15 min in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6). The sections were then incubated with specific primary antibodies against PCNA (1:200 dilution, ab15497, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), NAT10 (1:500 dilution, ab194297, Abcam), Vimentin (1:500 dilution, ab92547, Abcam), E-cadherin (1:500 dilution, 20874-1-AP, Proteintech), N-cadherin (1:100 dilution, ab76011, Abcam), LAMB3 (1:500 dilution, 26795-1-AP, Proteintech), PHGDH (1:500 dilution, 14719-1-AP, Proteintech) and KCNN4 (1:200 dilution, 23271-1-AP, Proteintech) at 4 °C overnight. An EnVision Plus System-HRP (DAB; DAKO) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and counterstaining was then performed with Mayer’s hematoxylin. The stained slides were visualized under an Olympus microscope (Olympus BX50, Japan). The IHC staining results were scored by two independent pathologists based on the percentage of positively stained cells (0 = 0%, 1 = 1–20%, 2 = 21–50%, 3 = 51–80%, 4 = 81–100%). The staining intensity was categorized into three grades (0 = negative, 1 = weak, 2 = moderate, 3 = strong). The two scores were multiplied to generate a final staining score ranging from 0 to 12. The final staining scores were averaged and rounded to the nearest whole number.

In vitro functional assays

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) proliferation, colony formation, Transwell migration and invasion, and wound healing assays were conducted as previously described [30]. Briefly, equal numbers of stably transfected PDAC cells were seeded in 96-well plates. After 24, 48 and 72 h of incubation, cell viability was measured using a CCK-8 (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For the colony formation assay, cells were seeded at 2000 cells/well in 6-well plates for 14 days. Colonies were fixed, stained with crystal violet (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and counted. For the Transwell migration and invasion assays, we used Corning Transwell chambers (Corning, NY, USA). For the migration assay, 1 × 105 cells were suspended in 200 μL of serum-free medium and plated in the upper chambers. Medium (800 μL) supplemented with 10% FBS was added to the lower chambers and cultured for 24 h. For the invasion assay, the membranes in the upper chambers were coated with 20 μg of Matrigel (Corning, NY, USA) and cultured for 48 h using the protocol described above. Subsequently, the cells that migrated from the upper chambers were fixed with 1% crystal violet staining solution for 20 min at room temperature and counted manually in three random fields. For the wound healing assay, cells were cultured in 6-well plates until confluent. The monolayers were scratched, washed with PBS and cultured in a serum-free medium. After 24 h of incubation, the monolayers were visualized.

In vivo functional assays

The subcutaneous xenograft mice model was established to evaluate tumor formation in vivo. The in vivo metastatic ability was investigated using tail vein and splenic injection experiments. For the subcutaneous xenograft assay, PANC-1 and BxPC-3 cells (5 × 106 cells/site) were subcutaneously injected into the right flanks of female BALB/c nude mice (4–6 weeks old). Four weeks later, the mice were killed, and the tumors were excised, weighed and placed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for histological analysis. The in vivo metastatic ability was investigated by two experimental approaches. For the tail vein injection experiment, 5 × 105cells resuspended in 150 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were injected into the tested nude mice via the tail vein. For the splenic injection experiment, 5 × 105cells resuspended in 50 μL of serum-free DMEM were injected into the spleens of the tested nude mice. All of the mice were euthanized 12 weeks post-injection. Tumors formed on the lungs and livers were detected macroscopically. Livers and lungs were excised from mice, fixed with 4% PFA and embedded in paraffin, and sections of those tissues were used for histological analysis. To establish the patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models, fresh tumor samples from patients with PDAC were inoculated subcutaneously into both flanks of nude mice [31]. Briefly, successfully established PDXs (P1) that attained a volume of 500 mm3 were transplanted into recipient mice (P2 and P3). Eventually, the mice bearing the P3 xenografts were used to examine the therapeutic effects of the inhibitor ASO-LINC00623. When the volume of the P3 xenografts reached 200 mm3, intratumoral injections of a scrambled ASO or the inhibitor ASO-LINC00623 (10 nmol per injection, RiboBio) were performed in the mice every 3 days. The animals were treated for 36 days, and the tumor volume was measured every 6 days using the following formula: V = π/6 × (W2 × L). Thereafter, the mice were anesthetized, and the tumors were weighed. All harvested tissues were used for pathological analysis. All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine Animal Use and Care Committee.

3D organoid models

3D organoid models were established as previously reported [32]. Briefly, approximately 1 cm3 of fresh tumor tissue was cut, soaked in PBS containing 5% penicillin–streptomycin and other antibiotics (2% Primocin, Invitrogen) for 30 min, and then minced. Enzymolysis of minced tissues was performed with 1.5 mg/mL collagenase IV (Catalog No. 7426, STEMCELL, British Columbia, Canada) for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells were washed twice with advanced DMEM/F12 and filtered through a 40-µm cell strainer (Catalog No. 27305, STEMCELL). After centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 5 min, the cells were inoculated into Matrigel (Catalog No. 356235, Corning, New York, USA) and overlaid with a human IntestiCult™ organoid growth medium (Catalog No. 06010, STEMCELL) containing 10 µM Y-27632, 1% Primocin and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. TrypLE™ Express Enzyme (Catalog No. 12604021, Thermo Scientific) was used to digest and resuspend the cells for organoid passaging.

Isolation of exosomes

Total exosomal RNA was isolated from 1.2 mL of serum using an exoRNeasy Midi Kit (77144, QIAGEN, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two hundred microliters of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was added to the membrane of a spin column to elute exosomes. Then, 50 μL of the eluate was used for nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), 50 μL of the eluate was used for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis, and 100 μL of the eluate was used for Western blot analysis. Exosomes were isolated from the culture medium of PDAC cells that had been cultured in complete medium containing 10% exosome-depleted FBS for 48 h. Exosomal RNAs were extracted with an exoEasy Maxi Kit (76064, QIAGEN, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Validation of exosomes

Exosome morphology was evaluated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) on a JEOL-1230 (JEOL, Japan) instrument. The density and size distribution of exosomes were measured by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) using a ZetaView PMX 110 instrument (Particle Metrix, Germany). The expression of the exosome markers (CD63 and CD81) and Calnexin was checked by Western blotting. Exosomal RNA was extracted using QIAzol (QIAGEN).

Exosomal lncRNA sequencing

Exosomal lncRNA-seq and the corresponding bioinformatic analyses were conducted by Guangzhou RiboBio Co. Ten serum samples were mixed with RiboTM Exosome Isolation Reagent, and exosome isolation was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (RiboBio, China). Exosomal RNA was extracted with MagZol Reagent (Magen, China). The RNA yield was quantified by using a Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and an Agilent 2200 TapeStation (Agilent Technologies, USA). Briefly, rRNAs were removed from exosomal RNA using a QIAseq FastSelect RNA Removal Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) and fragmented into pieces of approximately 200 bp. Subsequently, the RNA fragments were subjected to first-strand and second-strand cDNA synthesis, followed by adaptor ligation and enrichment with a low cycle number according to the instructions of the NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, USA). The purified library products were evaluated using the Agilent 2200 TapeStation and Qubit fluorometer. The libraries were subjected to paired-end 150 bp sequencing on an Illumina platform (Illumina, USA) at RiboBio Co., Ltd. (China). Sequencing read quality was inspected using FastQC software. Adapter removal and read trimming were performed using Trimmomatic. Sequencing reads were trimmed from the ends (base quality less than Q20) and filtered by length (less than 52). The paired-end reads were aligned to the human reference genome hg19 with HISAT2. HTSeq v0.12.4 was used to determine the number of reads mapped to each gene. The statistically significant differentially expressed genes were identified with the threshold criteria of adjusted P value < 0.05 and |log2(fold change)| > 1 using DESeq software.

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay

An EZ-Magna RIP Kit (Millipore) was used to perform the RIP assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Approximately 1 × 107 BxPC-3 or PANC-1 cells were harvested and lysed in 100% RIP lysis buffer with proteinase and RNase inhibitors, and the RIP lysates were incubated with RIP buffer containing magnetic beads conjugated to an anti-NAT10 (ab194297, Abcam) antibody, an anti-USP39 antibody (23865-1-AP, Proteintech), an anti-Flag antibody (14793S, CST, Danvers, USA) or control IgG (Millipore). Enrichment of LINC00623 was evaluated by qRT‒PCR.

Immunoprecipitation (IP)

Cells were homogenized in IP lysis buffer (Beyotime) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Beyotime), phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Beyotime) and EDTA (Beyotime). The lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatants were removed. Then, the prepared lysates were precleared using 10 μL of Protein A+G agarose beads (78610, Thermo Scientific) by incubation with rotation at 4 °C for 2 h. The antibodies of interest or control IgG were added to the precleared lysates, and 20 μL of Protein A+G agarose beads was then added to the mixture; the tubes were incubated with rotation at 4 °C overnight in each step. Finally, the samples were loaded onto an SDS‒PAGE gel for Western blotting.

RNA pulldown

A magnetic RNA Pulldown Kit (20164, Pierce) was used for LINC00623 pulldown assays. Biotinylated RNA was transcribed with Biotin RNA Labeling Mix and T7 RNA polymerase. Purified biotinylated RNA was heated and annealed to form the proper secondary structure, incubated with PANC-1 cell lysates for 1 h at 4 °C, and mixed with streptavidin–agarose beads (Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the enriched proteins were separated by SDS‒PAGE for analysis by mass spectrometry or Western blotting.

RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (RIP-seq) and data analysis

RIP-seq was performed on BxPC-3 cells by SeqHealth Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Briefly, 1 × 107 BxPC-3 cells were lysed, and the lysate was divided into aliquots for subsequent experiments. Approximately 10% of the lysate was stored and used as the “input” sample. Eighty percent of the lysate was used for immunoprecipitation with 5 µg of an anti-NAT10 antibody (ab194297, Abcam) antibody and used as the “IP” sample; the remaining 10% was incubated with rabbit IgG (3900S, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, USA) as the negative control “IgG” sample. RNA from the input and IP samples was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Sigma‒Aldrich) and used for RIP-seq. The stranded RNA sequencing library was constructed with a KC-DigitalTM Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (SeqHealth) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The kit eliminates duplication bias in the PCR and sequencing steps by using a unique molecular identifier (UMI) of 8 random bases to label the preamplified cDNA molecules. The library products with lengths of 200–500 bp were enriched, quantified and finally sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 instrument (Illumina) in PE150 mode. Trimmomatic (version 0.36) was used to filter the raw sequencing data, discard the low-quality reads, and trim the reads contaminated with adaptor sequences. The clean read data were further processed with in-house scripts to eliminate duplication bias introduced during library preparation and sequencing. In brief, the clean reads were first clustered according to the UMIs, and reads with the same UMI were grouped into the same cluster. The reads in the same cluster were compared to each other by pairwise alignment, and then the reads with sequence identity exceeding 95% were extracted to a new subcluster. After all the subclusters were generated, multiple sequence alignment was performed to obtain one consensus sequence for each subcluster. Through these steps, errors and biases in PCR amplification or sequencing were eliminated. Protein binding site analysis was conducted with the de-duplicated consensus sequences. They were mapped to the human reference genome (GRCh38) using STAR software (version 2.5.3a) with default parameters. RSeQC (version 2.6) was used for read distribution analysis. exomePeak (version 3.8) software was used for peak calling. Peaks were annotated using BEDtools (version 2.25.0). deepTools (version 2.4.1) was used for peak distribution analysis. The differential binding peaks were identified by a Python script using Fisher’s exact test. Sequence motifs enriched in peak regions were identified using Homer (version 4.10).

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and data analysis

High-throughput sequencing of RNA from NAT10 knockdown BxPC-3 cells was performed by CloudSeq Biotech (Shanghai, China). Briefly, rRNA was removed from total RNA using a NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit (New England Biolabs, Inc., Massachusetts, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. RNA libraries were constructed by using a NEBNext® Ultra™ II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit (New England Biolabs, Inc., Massachusetts, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were controlled for quality and quantified using a BioAnalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Inc., USA). Library sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 instrument with 150 bp paired-end reads. Paired-end reads were harvested from Illumina NovaSeq 6000 sequencer and were quality-controlled by Q30. After 3′ adaptor trimming and removal of low-quality reads with Cutadapt software (v1.9.3), the high-quality clean reads were aligned to the reference genome (UCSC hg19) with HISAT2 software (v2.0.4). Then, guided by the Ensembl gtf gene annotation file, the Cuffdiff tool (part of Cufflinks) was used to obtain gene expression data in FPKM as the mRNA expression profiles, and fold change and P values were calculated based on the FPKM values to identify the differentially expressed mRNAs. GO and pathway enrichment analyses were performed based on the differentially expressed mRNAs.

acRIP sequencing (acRIP-seq) and data analysis

The ac4C-IP-Seq service was provided by CloudSeq Biotech (Shanghai, China). Total RNA was subjected to immunoprecipitation using a GenSeq® ac4C-IP Kit (GenSeq Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, RNA was randomly fragmented into pieces of ~ 200 nt with RNA fragmentation reagents. Protein A/G beads were coupled to the anti-ac4C antibody by incubation with rotation at room temperature for 1 h. The RNA fragments were incubated with the antibody-conjugated beads and incubated with rotation at 4 °C for 4 h. The RNA/antibody complexes were then digested with Proteinase K, and the eluted RNA was purified by phenol/chloroform extraction. RNA libraries for IP and input samples were then generated with the NEBNext® Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit (New England Biolabs, Inc.) by following the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were qualified using the Agilent BioAnalyzer 2100 system and then sequenced on the NovaSeq platform (Illumina). Briefly, paired-end reads were harvested from Illumina NovaSeq 6000 sequencer and were quality-controlled by Q30. After 3′ adaptor trimming and removal of low-quality reads with Cutadapt software (v1.9.3), the clean reads of all libraries were aligned with the reference genome with HISAT2 software (v2.0.4). Acetylated sites in RNAs (peaks) were identified with MACS software. Differentially acetylated sites were identified with diffReps. The peaks identified by both software programs overlapping with exons in mRNA were identified and selected with in-house scripts.

Ribosome profiling sequencing (Ribo-seq) and data analysis

Ribo-seq was performed by CloudSeq Biotech (Shanghai, China). Cells or tissues were treated with lysis buffer to obtain cell or tissue lysates, respectively. RNase I was used to digest RNA but not ribosome-protected fragments (RPFs). The RNA samples were then treated with an rRNA depletion kit to remove as much rRNA contamination as possible before polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) purification of relatively short (20–38 nt) RPFs. Following PAGE purification, the 5′ and 3′ ends of RPFs were phosphorylated and ligated to adapters, respectively. The fragments were then reverse-transcribed into cDNA and amplified by PCR. Library quality was evaluated with the BioAnalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Inc., USA). Library sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 instrument. Cutadapt software (v1.9.3) was used to discard the low-quality reads, trim the reads contaminated with adaptor sequences and remove the rRNA and tRNA reads. After these steps, the high-quality clean reads were aligned to the reference genome (UCSC hg19) with TopHat2 software. HTSeq was used to determine the number of reads mapped to each gene. The significantly differentially expressed genes were identified with threshold criteria of adjusted P value < 0.05 and |log2(fold change)| > 1 using DESeq software.

Bioinformatic analysis of public datasets

Normalized microarray data from the GSE15471 dataset and normalized RNA-seq data from the GSE138437 dataset were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. For the TCGA cohort, gene expression data and clinical data were obtained from the TCGA hub in UCSC Xena (https://tcga.xenahubs.net). Analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) was performed with the “edgeR” package in the R environment (version 3.5.5). The diagnostic value was assessed with receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and visualized with the “pROC” R package. The Kaplan‒Meier method was used for survival analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 (IBM, SPSS, USA) and GraphPad Prism 6.0 software. All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments. Differences between groups were assessed using Student’s t test, and correlations between groups were determined using the Pearson correlation coefficient. The CCK-8 assay data were analyzed using ANOVA. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Identification of LINC00623 as a potential exosomal marker in patients with PDAC

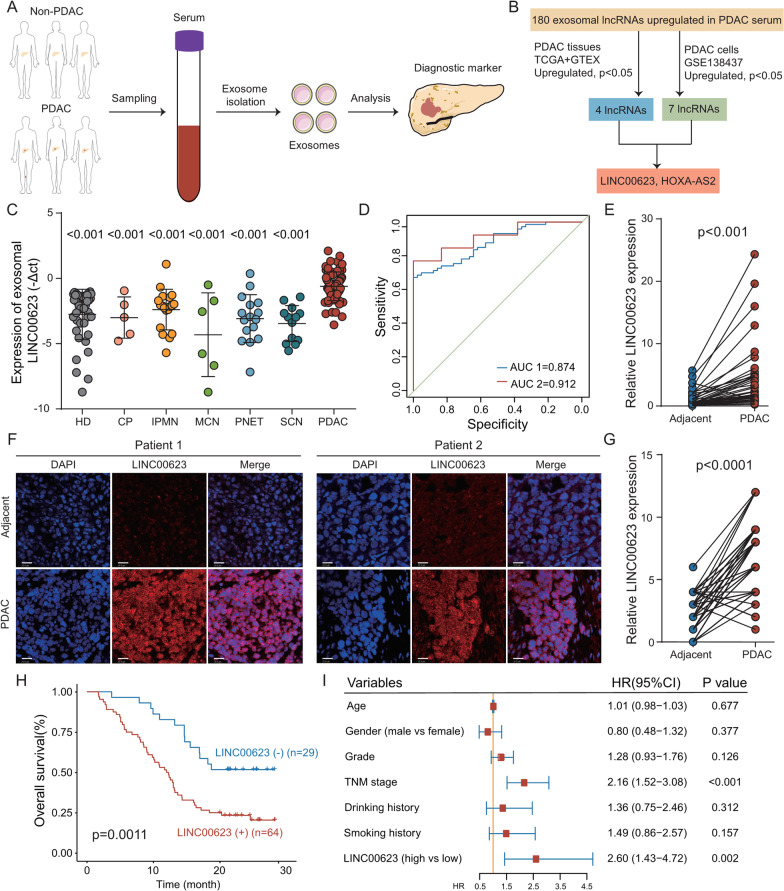

To investigate the potential of circulating exosomal lncRNAs as biomarkers for the early detection of PDAC, circulating exosomes from five PDAC patients and five healthy individuals were isolated and characterized (Additional file 12: Fig. S1A-C). Exosomal RNA was extracted and used for high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) (Fig. 1A), which identified a total of 4801 lncRNAs. Among these lncRNAs, 180 were upregulated and 148 were downregulated in serum samples from patients with PDAC (P < 0.05 and log2FC > 1, Additional file 12: Fig. S1D-E). Thereafter, the candidate lncRNAs were narrowed down based on their expression in PDAC tumor tissues and cell lines (Fig. 1B). Two candidate lncRNAs, LINC00623 and HOXA-AS2, were found to be highly expressed in seven PDAC cell lines compared with HPNE cells and to be upregulated in tumor tissues.

Fig. 1.

Exosomal LINC00623 is upregulated in PDAC and has clinical significance. a Workflow of screening for exosomal diagnostic biomarkers in the serum of patients with PDAC and healthy individuals. b Flowchart showing the process used to narrow down the upregulated exosomal lncRNAs in the serum of patients with PDAC compared to that of healthy individuals. c The levels of circulating exosomal LINC00623 were significantly higher in patients with PDAC than in healthy donors (HD) and patients with benign pancreatic neoplasms. Chronic pancreatitis (CP), intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN), mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN), pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (PNET), serous cystic neoplasm (SCN). Independent Student’s t test, P < 0.001. d Diagnostic AUC value of the circulating exosomal LINC00623 level. AUC1: PDAC (n = 73) vs. HD (n = 42); AUC2: PDAC with normal CA19-9 levels (n = 13) vs. HD (n = 42). e Relative expression of LINC00623 as measured by RT-qPCR in PDAC and matched adjacent normal tissues (n = 40). Independent Student’s t test, P < 0.001. f Representative images of FISH of LINC00623 (red) in 93 pairs of PDAC and adjacent normal tissues. DAPI (blue) was used for nuclear counterstaining. Scale bar = 20 μm. g The expression level of LINC00623 as determined by FISH in PDAC and adjacent normal tissues (n = 93). Independent Student’s t test, P < 0.001. h Kaplan‒Meier survival curve of two groups of patients with PDAC (n = 93): LINC00623(+), patients with high LINC00623 expression; LINC00623(−), patients with low LINC00623 expression. The expression of LINC00623 was determined by FISH. i Univariate Cox regression analyses of the survival of patients with PDAC (n = 93)

Expression of LINC00623 and its clinical significance in patients with PDAC

RT-qPCR analysis was performed to confirm the presence of two candidate exosomal lncRNA markers in a larger patient cohort. The levels of circulating exosomal LINC00623 were significantly higher in patients with PDAC (n = 73) than in healthy individuals (n = 42). Moreover, the circulating levels of exosomal LINC00623 in patients with benign pancreatic neoplasms were similar to those in healthy individuals (Fig. 1C). However, the differences in the levels of circulating exosomal HOXA-AS2 between patients with pancreatic diseases and patients with PDAC were not significant (data not shown); therefore, LINC00623 was selected for further investigation. The AUC values of circulating exosomal LINC00623 were sufficient for distinguishing between patients with PDAC and healthy individuals (AUC1 = 0.874, Fig. 1D). More importantly, LINC00623 had a higher AUC value for distinguishing PDAC patients with normal CA19-9 levels than for distinguishing patients with elevated CA19-9 levels (AUC2 = 0.912, Fig. 1D).

The expression of LINC00623 in cell lines and 40 pairs of PDAC tissues was examined using RT-qPCR. Consistent with the results from public datasets (GSE15471 and TCGA), LINC00623 expression was upregulated in tumor tissues and PDAC cell lines (Fig. 1E, Additional file 12: Fig. S1F-H). The levels of exosomal LINC00623 in the cell culture medium were positively associated with the expression of LINC00623 in the corresponding PDAC cell lines (Additional file 12: Fig. S1I-M). LINC00623 expression was further determined through fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) staining of a tissue microarray (TMA) consisting of 93 pairs of PDAC and nontumor specimens (Fig. 1F–G). Patients with PDAC were divided into two groups based on their FISH scores. A clinical association study found that LINC00623 expression was significantly correlated with histological grade (Table 1). Kaplan‒Meier survival analysis showed that the expression of LINC00623 was significantly associated with a poor overall survival rate (Fig. 1H). Similar results were observed in a cohort of 40 paired PDAC tissues and nontumor tissues (Additional file 12: Fig. S1N). Cox proportional hazards regression analysis showed that LINC00623 expression was an independent prognostic factor for overall survival in patients with PDAC (P = 0.002, Fig. 1I). The coding potential calculator and coding potential assessment tool indicated that LINC00623 had no protein-coding potential [33, 34] (Additional file 12: Fig. S1O).

Table 1.

Associations between LINC00623 expression and clinicopathological features in 93 patients with PDAC

| Feature | Total | LINC00623 expression | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | |||

| Sex | 0.26 | |||

| Male | 56 | 15 | 41 | |

| Female | 37 | 14 | 23 | |

| Age (years) | 0.116 | |||

| ≤ 65 | 53 | 20 | 33 | |

| > 65 | 40 | 9 | 31 | |

| Serum CA19-9 (U/mL) | 0.551 | |||

| ≤ 37 | 19 | 7 | 12 | |

| > 37 | 74 | 22 | 52 | |

| Drinking history | 0.728 | |||

| Yes | 18 | 5 | 13 | |

| No | 75 | 24 | 51 | |

| Smoking history | 0.809 | |||

| Yes | 21 | 7 | 14 | |

| No | 72 | 22 | 50 | |

| Histological grade | 0.0092 | |||

| ≤ 2 | 59 | 24 | 35 | |

| > 2 | 34 | 5 | 29 | |

| Vascular invasion | 0.158 | |||

| Absent | 78 | 22 | 56 | |

| Present | 15 | 7 | 8 | |

| Metastasis | 0.701 | |||

| Absent | 85 | 26 | 59 | |

| Present | 8 | 3 | 5 | |

| TNM stage | 0.337 | |||

| ≤ II | 73 | 21 | 52 | |

| > II | 20 | 8 | 12 | |

Statistical significance (P < 0.05) is shown in bold

LINC00623 promotes tumorigenesis and metastasis in PDAC

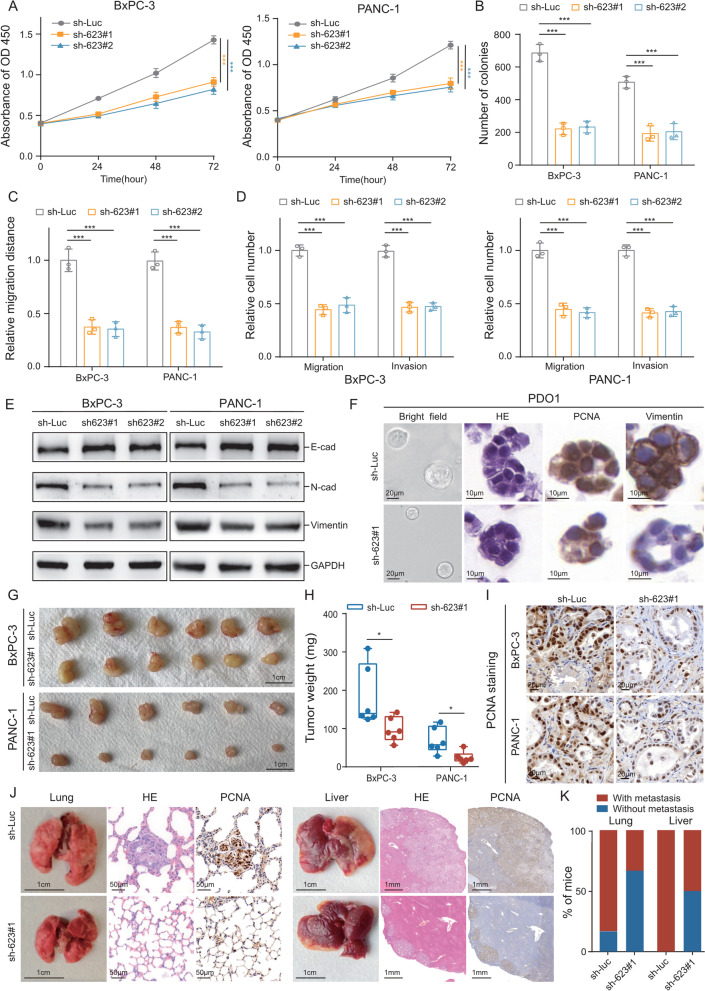

To investigate the functional role of LINC00623 in PDAC, two PDAC cell lines (BxPC-3 and PANC-1) were used for in vitro and in vivo functional assays. LINC00623 expression was silenced using two short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) and overexpressed using the dCAS9-SAM system (Additional file 13: Fig. S2A, 2E). LINC00623 silencing significantly suppressed cell proliferation (Fig. 2A), foci formation (Fig. 2B, Additional file 13: Fig. S2B), cell mobility (Fig. 2c, Additional file 13: Fig. S2C), and cell migration and invasion (Fig. 2D, Additional file 13: Fig. S2D). As expected, LINC00623 overexpression enhanced the tumorigenic and metastatic abilities of PDAC cells (Additional file 13: Fig. S2F-I). Western blotting revealed that LINC00623 overexpression downregulated the expression of epithelial markers (E-cadherin) and upregulated that of mesenchymal markers (N-cadherin and Vimentin) (Fig. 2E, Additional file 13: Fig. S2J). Furthermore, two PDAC patient-derived organoid (PDO) models were established (Additional file 13: Fig. S2K), and we observed that LINC00623 silencing not only reduced the size of the organoids but also decreased the cell proliferation rate (as determined by PCNA expression) and EMT marker (Vimentin) expression in these PDOs (Fig. 2F, Additional file 13: Fig. S2L-P).

Fig. 2.

LINC00623 enhanced the proliferation, migration and invasion abilities of PDAC cells in vitro and in vivo. a CCK-8 assays were used to determine the cell proliferation rates. b The results of quantitative analysis of foci numbers are summarized in the bar chart. c The relative migration distance of the indicated cells was determined in the wound healing assay. d The relative numbers of migrated and invaded cells in the indicated groups in the Transwell migration and invasion assays are summarized in the bar chart. Cells transfected with control plasmids were used as controls. a–d The values indicate the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. P values are shown as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, or *** P < 0.001. Independent Student’s t test. e The protein expression levels of E-cadherin, N-cadherin and Vimentin in BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells were determined by Western blotting. GAPDH was used as the loading control. f Representative images of H&E staining and IHC staining of PDO1. PDO1 was transiently transfected with the LINC00623 shRNA or control plasmid. Antibodies against PCNA and Vimentin were used in the IHC assays. g Representative images of subcutaneous tumors formed by the indicated cells. h Tumor weights are expressed as the mean ± SD of six mice (*P < 0.05, independent Student’s t test). i Representative images of IHC staining with anti-PCNA antibody in tumors formed by the indicated cells. j Two in vivo metastasis assays were performed by tail vein injection (left) and splenic injection (right) to evaluate the effect of LINC00623 knockdown on tumor metastasis. Representative images of excised lungs and livers and of H&E staining and IHC staining with an anti-PCNA antibody in metastatic tumors formed by BxPC-3 cells. k The frequency of tumor metastasis in each group is summarized in the bar chart

To test the tumorigenic ability of LINC00623 in vivo, LINC00623-silenced PDAC cells and vector-transfected controls were inoculated into the left and right dorsal flanks, respectively, of BALB/c nude mice. The tumors formed by LINC00623-silenced cells were smaller than those formed by control cells (Fig. 2G-H). The decreased tumor volume may be attributed to the decreased proliferation rate of the silenced cells, given that fewer PCNA-positive cells were observed in the various xenograft tumors formed by LINC00623-silenced cells (Fig. 2I, Additional file 13: Fig. S2Q). Two in vivo metastasis experiments were performed to validate the role of LINC00623 in PDAC metastasis. In the tail vein injection experiment, metastatic nodules were observed on the surface of the lungs in 1 of the 6 mice injected with LINC00623-silenced cells. In contrast, metastatic nodules were observed in 4 of the 6 mice injected with control cells. In line with the results of the tail vein injection experiment, multiple metastatic tumor nodules were observed in the livers of mice subjected to splenic injection of LINC00623-silenced cells (3/6 mice) and control cells (6/6 mice) (Fig. 2J–K).

LINC00623 binds to NAT10

The function of lncRNAs is closely related to their subcellular localization. To explore the molecular mechanism underlying the oncogenic activity of LINC00623 in PDAC tumorigenicity, we first determined the subcellular localization of LINC00623. Similar to the FISH results in clinical samples (Fig. 1F), single-molecule RNA FISH in BxPC-3 cells revealed that approximately 70% of the LINC00623 molecules were localized in the nucleus (Additional file 14: Fig. S3A). The subcellular localization of LINC00623 was further confirmed via nuclear and cytoplasmic separation assays (Additional file 14: Fig. S3B). Given its nuclear localization, LINC00623 may interact with nuclear-specific proteins [35–37]. Biotinylated LINC00623 sense and antisense RNAs were transcribed, and RNA pulldown assays were performed to identify the proteins associated with LINC00623 in PDAC cells. The enriched proteins were separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate‒polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‒PAGE) for mass spectrometry. Approximately 433 potentially interacting proteins were identified (Additional file 5: Table S5). Subcellular localization enrichment analysis (GO-CC) indicated that most proteins were localized in the nucleus. Among these nuclear proteins, NAT10 was identified as the potential protein that bound to LINC00623 (Fig. 3A). NAT10 was enriched in the RNA pulldown products from two PDAC cell lines transfected with LINC00623 (Fig. 3B). Moreover, PCR showed that LINC00623 could be detected in the RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) products using an antibody against NAT10 (Fig. 3C). In addition, the results of the immunofluorescence (IF) assays confirmed the colocalization of LINC00623 and NAT10 (Fig. 3D). Next, a series of deletion mutants were constructed based on the secondary structure of LINC00623 (http://www.lncipedia.org/, Additional file 14: Fig. S3C-D), especially mutants with deletions within the region of LINC00623 containing nt 700–1800, which mediated its interaction with NAT10 (Fig. 3E). Moreover, RIP assays with FLAG-tagged full-length and truncated NAT10 proteins showed that the deletion mutant lacking the binding domain (753–1025 aa) of NAT10 failed to interact with LINC00623 (Fig. 3F, Additional file 14: Fig. S3E, F).

Fig. 3.

LINC00623 binds to NAT10. a GO-CC (cellular component) analysis predicting the potential proteins binding to LINC00623. b Western blotting was performed to evaluate the specific association of NAT10 with biotinylated LINC00623. Lysates of BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells were harvested for RNA pulldown assays. LINC00623 antisense RNA was used as the negative control. c A RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay was performed using an antibody against NAT10. RT-PCR was used to detect LINC00623 enrichment. IgG was used as the isotype control. d Immunofluorescence (IF) staining showed that LINC00623 (red) was colocalized with NAT10 (green) in the nucleus. Scale bar = 10 μm. e Western blotting of NAT10 in samples precipitated by biotinylated full-length LINC00623 (FL) or LINC00623 truncations (Δ1: 1–699 bp; Δ2: 700–1200 bp; Δ3: 1201–1800 bp; Δ4: 1801–2500 bp; Δ5: 2501–3000 bp; Δ6: 3001–3607 bp). FL LINC00623 was used as the positive control. f Flag-RIP assay for LINC00623 showing its fold enrichment in cells transiently transfected with plasmids containing FLAG-tagged full-length and truncated NAT10 constructs (Del1: 1–280 aa; Del2: 281–488 aa; Del3: 558–753 aa; Del4: 753–1052 aa). IgG-RIP was used as the internal control. The values are expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments

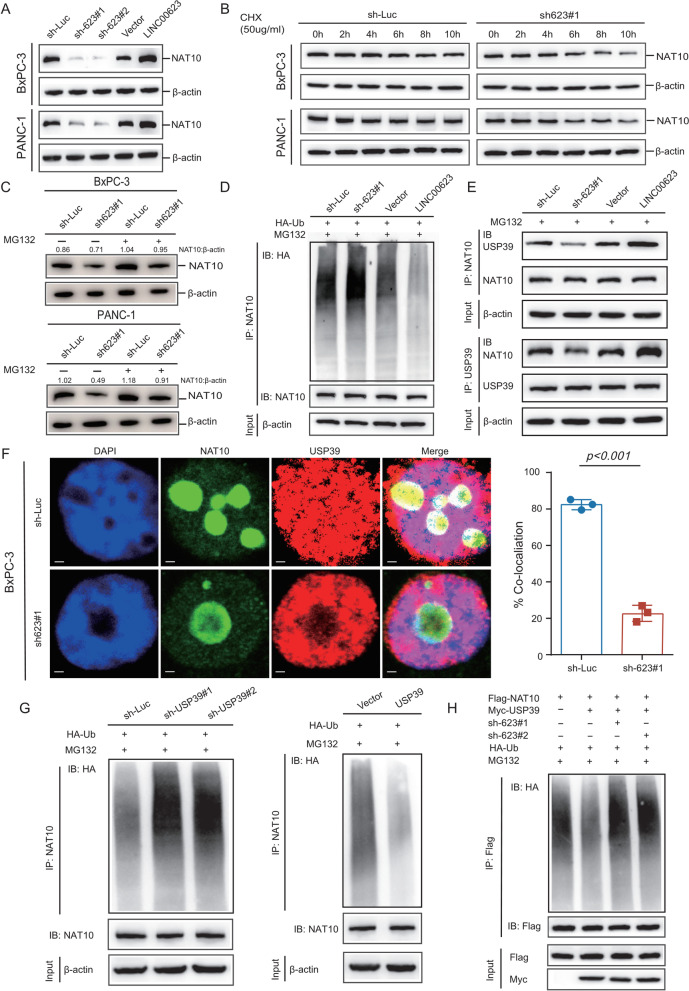

LINC00623 blocks NAT10 ubiquitination and degradation

Given that LINC00623 interacts with NAT10 in PDAC cells, we investigated whether LINC00623 regulates the expression of NAT10. Interestingly, LINC00623 had no effect on the mRNA level of NAT10 (Additional file 15: Fig. S4A). However, the protein level of NAT10 was dramatically decreased when LINC00623 was silenced and increased when LINC00623 was overexpressed (Fig. 4A). Moreover, after treatment with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX), LINC00623 silencing reduced the half-life of the NAT10 protein (Fig. 4B). The ubiquitin–proteasome system and lysosomal pathway play important roles in intracellular proteolysis [38]. The proteasome inhibitor MG132, but not the autophagy inhibitor chloroquine (CQ), which abolishes lysosomal protein degradation, led to the accumulation of endogenous NAT10 in PDAC cells upon LINC00623 silencing (Fig. 4C, Additional file 15: Fig. S4B), suggesting that LINC00623 might inhibit the proteasome-dependent degradation of NAT10 in PDAC cells. As expected, the ubiquitination levels of NAT10 were dramatically increased in LINC00623-silenced cells but decreased in cells overexpressing LINC00623 (Fig. 4D, Additional file 15: Fig. S4C).

Fig. 4.

LINC00623 blocks NAT10 ubiquitination and degradation. a The protein levels of NAT10 in BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells. β-Actin was used as the loading control. b The protein levels of NAT10 in the indicated cells treated with cycloheximide (CHX, 50 μg/mL) for 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 h. c The protein levels of NAT10 in the indicated cells treated with or without MG132 (10 μM) for 6 h. d BxPC-3 cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-NAT10 antibody and immunoblotted with an anti-HA antibody. e IP was performed to detect the association between NAT10 and USP39 in BxPC-3 cells. d–e BxPC-3 cells were transiently transfected with LINC00623 knockdown, LINC00623 overexpression or control plasmids and then treated with MG132 for 4 h before cell lysates were harvested for co-IP with an anti-NAT10 (IP: NAT10) or anti-USP39 (IP: USP39) antibody. f The colocalization of NAT10 (green) and USP39 (red) in BxPC-3 cells was evaluated by IF. Scale bar = 2 μm (left). The percentage of colocalization (Mander’s coefficients) of NAT10 and USP39 is summarized in the bar charts (right). g The ubiquitination levels of NAT10 were determined by Western blotting. BxPC-3 cells were transiently transfected with USP39 silencing (left), USP39 overexpression (right) and control plasmids and then treated with MG132 for 4 h before cell lysates were harvested for co-IP with an anti-NAT10 antibody and immunoblotted with an anti-HA antibody. h The ubiquitination levels of NAT10 in the products of IP with an anti-Flag antibody in lysates from BxPC-3 cells transfected with LINC00623 knockdown or USP39 overexpression and control plasmids

LncRNAs have also been reported to act as scaffolds for protein complexes during processes that maintain cellular homeostasis, including protein ubiquitination [39–41]. Among the 433 potential LINC00623-interacting proteins, two deubiquitinases (USP39 and PRRF8) were identified (Additional file 15: Fig. S4D, Additional file 5: Table S5) [42]. A previous study indicated that NAT10 was among the proteins immunoprecipitated with USP39 [43]. Thus, we hypothesized that LINC00623 serves as an assembly scaffold that facilitates the interaction between NAT10 and USP39, inhibiting the ubiquitination and degradation of NAT10. First, USP39 RIP and LINC00623 pulldown assays were performed to confirm the interaction between LINC00623 and USP39 (Additional file 15: Fig. S4E–F). Their colocalization was also observed in two PDAC cell lines (Additional file 15: Fig. S4G). In addition, coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and IF assays showed that NAT10 physically interacted and colocalized with USP39 and that this interaction was dependent on the expression level of LINC00623 (Fig. 4E, F, Additional file 15: Fig. S4H). Subsequently, the effect of USP39 on NAT10 ubiquitination was also investigated. The ubiquitination level of NAT10 was negatively correlated with the expression level of USP39 (Fig. 4G, Additional file 15: Fig. S4I). Moreover, following treatment with CHX, the USP39 level determined the half-life of the NAT10 protein (Additional file 15: Fig. S4J). As the site mutation C306A abrogated the deubiquitinase activity of USP39, USP39 site mutant (C306A) and USP39 wild-type (WT), control vectors were constructed and transiently transfected into two PDAC cell lines. The protein level of NAT10 was lower in cells transfected with the USP39 site mutant (C306A) construct than in cells transfected with the WT construct (Additional file 15: Fig. S4K-L). It is important to note that LINC00623 silencing still enhanced the ubiquitination of NAT10 in PDAC cells even after USP39 overexpression (Fig. 4H). Collectively, these results indicate that LINC00623 acts as a scaffold supporting the interaction of NAT10 with USP39, which increases the stability of NAT10 by blocking its ubiquitination-dependent degradation.

NAT10 functions as a downstream mediator of LINC00623 by remodeling N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C) modification of mRNA

The protein level of NAT10 was determined via IHC staining of 93 pairs of PDAC tissues and adjacent nontumor tissues. Similar to the expression pattern of LINC00623 in PDAC clinical samples, higher levels of NAT10 were detected in tumor tissues than in nontumor tissues (Fig. 5A, Additional file 16: Fig. S5A). Interestingly, strong positive signals were also observed in PanIN tissues, suggesting that NAT10 may play a role in PDAC development and progression (Fig. 5A). As expected, the NAT10 protein level was associated with the LINC00623 expression level (Fig. 5B). Moreover, higher expression levels of NAT10 significantly correlated with poorer overall survival rates in our in-house PDAC cohort (P = 0.0069; Fig. 5C) and in the TCGA database (P = 0.076; Additional file 16: Fig. S5B).

Fig. 5.

NAT10 functions as a downstream mediator of LINC00623by remodeling N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C) modification of mRNA. a Representative images of IHC staining with an anti-NAT10 antibody in PDAC, pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) or matched adjacent normal pancreatic tissues (NP). b The mRNA level of LINC00623 was positively correlated with the protein level of NAT10 in PDAC tissues (n = 93). c Kaplan‒Meier survival curve of two groups of patients with PDAC (n = 93): NAT10 (+), patients with high NAT10 expression; NAT10 (-), patients with low NAT10 expression. The expression of NAT10 was determined by IHC staining. d Schematic diagram of the effects of NAT10 on the stability and translation efficiency of mRNA by catalyzing ac4C modification. e Metagene profile showing the distribution of NAT10 peaks across full-length transcripts containing the 5′UTR, CDS, and 3′UTR. BxPC-3 cell lysates were used for the NAT10 RIP assay. f Metagene profile showing the distribution of ac4C peaks across full-length transcripts containing the 5′UTR, CDS, and 3′UTR. BxPC-3 cell lysates were also used for acRIP. g Venn diagram showing the downstream target genes regulated by NAT10 via ac4C modification in BxPC-3 cells. Group 1: The gene set enriched in NAT10 RIP-seq (RIP-seq); Group 2: The set of target genes enriched in parental cells but not in NAT10-silenced cells according to acRIP-seq (acRIP-seq); Group 3: The genes upregulated or downregulated in NAT10-silenced cells compared with control cells (RNA-seq); Group 4: The mRNA transcripts displaying differences in translation efficiency in NAT10-silenced cells (Ribo-seq). h Functional annotation and pathway enrichment analysis of the predicted downstream target genes of NAT10 according to the Metascape database. i The relative mRNA levels of NAT10, KCNN4, LAMB3 and PHGDH were measured by RT-qPCR. j The protein levels of KCNN4, LAMB3 and PHGDH were determined by Western blotting. k RT-qPCR was used to detect the relative enrichment of KCNN4, LAMB3 and PHGDH mRNAs in NAT10 RIP products. l RT-qPCR was used to detect the relative enrichment of KCNN4, LAMB3 and PHGDH mRNAs in acRIP products. i–l BxPC-3 cells were transfected with NAT10 silencing and control plasmids. Cell lysates were harvested for RIP assays. IgG was used as the isotype control. The values indicate the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. P values are shown as *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Independent Student’s t test

Western blot analysis was performed to evaluate the protein level of NAT10 in five PDAC cell lines, one immortalized pancreatic cell line, and the NAT10 knockdown/overexpression system (Additional file 16: Fig. S5C-D). NAT10 knockdown markedly decreased the foci formation and migration capabilities of BxPC-3 cells, even when they were pretreated with the LINC00623 overexpression construct (Additional file 16: Fig. S5E, 5G). However, NAT10 overexpression restored the foci formation and migration abilities, which were impaired by LINC00623 knockdown (Additional file 16: Fig. S5F, 5H). These results demonstrated that NAT10 contributes to the LINC00623-induced tumorigenic effects in PDAC cells. As the only known ac4C “writer” protein, NAT10 is thought to have critical effects on modulating mRNA stability and translation [26, 44]. To obtain the expression profile of genes regulated by NAT10-mediated ac4C modification, integrated NAT10 RIP-seq, acRIP-seq, RNA-seq and Ribo-seq analyses were performed in NAT10 knockdown cells (Fig. 5D). According to the NAT10 RIP-seq and acRIP-seq results, NAT10 and ac4C modifications were widely distributed across the transcriptome, with most sites located in CDSs (Fig. 5E, F), consistent with a previous study [45]. The gene set enriched in NAT10 RIP-seq was defined as Group 1 (Fig. 5G, Additional file 6: Table S6). In the comparison of the acRIP-seq data between parental and NAT10-silenced cells, the set of genes that were enriched in parental cells but not in silenced cells was defined as Group 2 (Fig. 5G, Additional file 7: Table S7). It has been reported that ac4C modification can increase gene expression by maintaining mRNA stability and promoting translation efficiency [26, 44, 45]. Thus, transcriptome profiling was performed using deep RNA-seq in NAT10-silenced cells and control cells to compare the expression levels of various mRNAs. The set of genes with differential expression levels was defined as Group 3 (Fig. 5G, Additional file 8: Table S8). In addition, to explore the effects of ac4C on mRNA translation efficiency, we examined ribosome occupancy across the transcriptome through ribosome profiling sequencing (Ribo-seq). In the comparison of the Ribo-seq data between parental and NAT10-silenced PDAC cells, the set of mRNA transcripts displaying significant differences in translation efficiency was defined as Group 4 (Fig. 5G, Additional file 9: Table S9). After evaluating the intersection of Groups 1 to 4, we identified 183 genes (Fig. 5G, Additional file 10: Table S10). Gene ontology (GO) analysis revealed that most of these genes were enriched in signaling pathways involved in cell growth, cell adhesion and extracellular matrix organization (Fig. 5H). Among these 183 genes, 12 have been widely demonstrated to contribute to PDAC progression (Additional file 11: Table S11). The RT-qPCR and Western blotting results demonstrated that the MUC4, LAMB3 and PHGDH expression levels were markedly decreased after NAT10 knockdown (Fig. 5I, J) [46–49]. Representative browser shots showing the transcriptome alignment of the three enriched targets showed discrete peaks in the ac4C-modified mRNA in parental cells, and these peaks were substantially ablated in cells with NAT10 silencing (Additional file 16: Fig. S5I). NAT10 RIP and subsequent RT-qPCR indicated that the defined ac4C targets significantly interacted with NAT10 (Fig. 5K). The RT-qPCR results supported the accuracy of acRIP-seq mapping, which showed increased amplification in the ac4C target regions of the three genes that was reduced in NAT10-silenced cells (Fig. 5L). Moreover, the expression levels of MUC4, LAMB3 and PHGDH were significantly higher in tumor tissues than in nontumor tissues (Additional file 16: Fig. S5J). Together, these findings demonstrate that the effect of LINC00623 on PDAC malignancy is dependent on NAT10, which remodels ac4C modification in PDAC, maintains the stability of oncogenic mRNAs and promotes their translation efficiency.

LINC00623 is a potential therapeutic target for PDAC

As LINC00623 plays an essential role in PDAC tumorigenicity, we further investigated the potential use of LINC00623 as a therapeutic target for PDAC. Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models were established using fresh PDAC tissues with a high LINC00623 expression level (Fig. 6A). For targeting long noncoding RNAs, an in vivo optimized inhibitor mainly composed of antisense oligonucleotides was reported to display strong knockdown effects on nuclear localized RNAs [50]. The LINC00623 inhibitor (ASO-LINC00623) was administered to the PDX models via intratumoral injection. We found that ASO-LINC00623 significantly reduced the tumor burden in both PDX models (Fig. 6B, C). Intriguingly, the treatment had greater benefits in tumors derived from PDAC tissues with higher LINC00623 expression (Fig. 6D). In addition, as shown by H&E and IHC staining, ASO-LINC00623 significantly decreased LINC00623 expression, cell proliferation (as indicated by the PCNA level), and EMT, which may be attributed to the decreased protein level of NAT10 (Fig. 6E, F, Additional file 17: Fig. S6A-B).

Fig. 6.

LINC00623 is a potential therapeutic target for PDAC. a Graphical diagram of intratumoral injection of in vivo optimized LINC00623 inhibitor in PDX-bearing mice. b Representative images of xenograft tumors derived from PDX1 or PDX2 in each mouse group. Mice bearing xenograft tumors were treated with antisense oligonucleotide control (ASO-Ctrl) or an in vivo optimized LINC00623 inhibitor (ASO-LINC00623). Xenograft tumor growth was monitored by measuring the tumor volume every six days (c) and weighing the tumors (d). Tumor volume and weight are expressed as the mean ± SD of five mice (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; independent Student’s t test). e Representative images of H&E staining, IHC staining and FISH of xenograft tumors. Scale bar = 50 μm. f Schematic diagram of the effect of the LINC00623/NAT10 axis on the tumorigenicity and progression of PDAC

Discussion

Late detection is a major reason for the poor prognosis of patients with PDAC, who often present with surgically unresectable disease [51]. Recent studies have suggested that exosomal lncRNAs show great promise for the early detection of cancers [23, 52]. Here, we identified a novel circulating exosomal lncRNA, LINC00623, as a reliable biomarker for the early diagnosis of PDAC. The sensitivity and specificity of circulating exosomal LINC00623 levels were similar to those of CA19-9, the most common biomarker evaluated in patients with PDAC [53]. Moreover, exosomal LINC00623 exhibited a high AUC value for distinguishing PDAC patients with normal CA19-9 levels. Furthermore, exosomal LINC00623 can distinguish PDAC from other pancreatic precancerous lesions and benign neoplasms. Because the nonspecific expression of CA19-9 in benign and malignant diseases limits the universal application of serum CA19-9 levels in the early detection of PDAC, a combination of serum CA19-9 and exosomal LINC00623 might be a more accurate option for the early diagnosis of this disease. Although screening of the general population is unfeasible because of the relatively low prevalence of PDAC, assessing exosomal LINC00623 levels in larger noncancer cohorts and patients with other pancreatic diseases is necessary to establish the specificity of the marker.

Exosomes function in cell‒cell communication via secretion by specific cells and are regarded as messengers sent from their cells of origin [54, 55]. Exosome-mediated cell-free RNA can be released into the circulation and is a potential subtype-specific biomarker for cancer detection [56]. Exosomes produced by tumor cells often contain a wide range of functional lncRNAs, miRNAs and proteins and are thus able to transfer their genetic contents from tumor cells into the surrounding cells, including epithelial cells, stromal cells and immune cells [57, 58]. Studies have contributed to unraveling the molecular mechanisms by which exosomal noncoding RNAs affect the proliferation, invasion and migration of PDAC cells [25]. However, the clinical significance and functional role of exosomal LINC00623 in cancer progression remain to be explored. Consistent with the increased levels of circulating exosomal LINC00623 in patients with PDAC, the expression of LINC00623 was also upregulated in PDAC tissues compared to adjacent nontumor tissues. Moreover, upregulated LINC00623 expression was associated with clinicopathological features and poor prognosis. Functionally, LINC00623 was found to promote PDAC tumor growth and invasiveness in vitro and in vivo, including in 3D organoid and PDX models. We also observed that ASO-LINC00623 significantly inhibited PDAC growth and reduced the tumor burden in PDX models, suggesting that disrupting LINC00623 activity may constitute a new therapeutic target for PDAC. Considering that LINC00623 has been reported to be associated with the progression of only osteosarcoma to date [59], we further elucidated the underlying mechanism of LINC00623 in PDAC tumorigenicity and progression.

LncRNAs commonly exert biological effects through physical interactions with regulatory molecules, such as protein, miRNA and DNA [60]. The subcellular localization of lncRNAs largely determines their molecular mechanisms of action. Consistent with our finding that LINC00623 was mainly localized in the nucleus, most of the enriched proteins in the LINC00623 RNA pulldown assays also exhibited nuclear localization. Among the potential LINC00623-binding proteins, NAT10 and USP39 attracted our attention. NAT10 catalyzes almost all ac4C events in mRNA in eukaryotes [61, 62]. mRNA modifications have been demonstrated to play an important role in mRNA stability, processing and translation [63]. Among these mRNA modifications, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most widely investigated and has been identified as an accelerator of pre-mRNA processing and mRNA transport in mammalian cells. However, ac4C remains relatively unexplored. It has been reported that ac4C is associated with substrate mRNA stability, whereas m6A is correlated with mRNA destabilization. Compared with m6A, which displays a 3′ localization bias, ac4C modification is distributed across the transcriptome and is enriched in the 5′ regions of coding sequences [44, 63]. There are several well-investigated m6A “writers”; however, NAT10 and its homologs are the only enzymes in humans that catalyze ac4C in all cases [44, 61, 62]. Ablation of NAT10 decreased ac4C modification, which led to downregulation of the target mRNAs. NAT10-dependent ac4C modification not only maintains mRNA stability but also promotes translation efficiency [44]. Consistent with this observation, the integrated NAT10 RIP-seq, acRIP-seq, RNA-seq and Ribo-seq analyses in NAT10 knockdown cells in this study demonstrated that NAT10 can remodel ac4C modification in PDAC and regulate the stability and downstream translation of transcripts of the corresponding oncogenes. Recent studies have shown that NAT10 is strongly associated with poor prognosis and malignant features in human cancers [45, 64, 65]. Ubiquitination is a key determinant of protein degradation. Here, we reported that LINC00623 acts as a scaffold supporting the interaction of NAT10 with USP39, a member of a deubiquitinase family of proteins that has been reported to be an oncogene in several cancers [43, 66–69]. A site mutation (C306) in USP39 abrogated its deubiquitinase activity and led to the degradation of NAT10 in PDAC cells.

Taken together, our findings revealed that exosomal LINC00623 could be a promising biomarker with high specificity and sensitivity for PDAC diagnosis. LINC00623 upregulation in PDAC tissues has clinical significance. Knockdown of LINC00623 significantly reduced the proliferation, tumorigenic, migration and invasion capabilities of PDAC cells in vitro and in vivo. LINC00623 acted as a scaffold for NAT10 and USP39 to inhibit ubiquitin-dependent NAT10 degradation. Thereafter, NAT10 remodeled ac4C modification of mRNA and enhanced the stability and translation of oncogenic mRNAs in PDAC. This characterization of LINC00623/NAT10 signaling provides insight into PDAC tumorigenicity and progression and may facilitate the development of precision approaches for PDAC diagnosis and treatment.

Conclusions

In summary, we identified exosomal LINC00623 as a promising biomarker with high specificity and sensitivity for early PDAC diagnosis. The LINC00623/NAT10 signaling axis promotes the proliferation, tumorigenic, migration and invasion capabilities of PDAC cells. Mechanistically, NAT10 enhances the stability and translation of oncogenic mRNAs in PDAC by remodeling ac4C modification of mRNA. Moreover, an in vivo optimized inhibitor targeting LINC00623 has potential as a candidate drug for PDAC treatment.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Characteristics of patients enrolled in this study.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Sequences of primers used in RT-qPCR assays.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Sequences of shRNA used in the study.

Additional file 4: Table S4. Antibodies used in this study.

Additional file 5: Table S5. Proteins identified by mass spectrometry analysis of RNA pull-down fractions.

Additional file 6: Table S6. List of NAT10-binding transcripts identified in NAT10 RIP-seq analysis.

Additional file 7: Table S7. List of acetylated transcripts identified in acRIP-seq analysis.

Additional file 8: Table S8. List of down-regulated genes identified in RNA-seq analysis.

Additional file 9: Table S9. Translation efficiency of mRNAs before and after NAT10 knockdown.

Additional file 10: Table S10. The predicted downstream target genes of NAT10 in BxPC-3 cells.

Additional file 11: Table S11. Twelve predicted downstream target genes of NAT10 have been proved to contribute to PDAC progression.

Additional file 12: Figure S1. Exosomes from serum samples were characterized by nanoparticle tracking analysis (a), Western blotting (b) and transmission electron microscopy (c). d Cluster heatmaps showing the differential expression levels of exosomal lncRNAs in serum samples from 5 healthy individuals (N) and 5 patients with PDAC (T). Red indicates a higher expression level, and blue indicates a lower expression level. e Volcano plot comparing the expression levels of circulating exosomal lncRNAs between patients with PDAC and healthy individuals. The vertical dashed lines indicate the cutoff of fold change > 1, and the horizontal dashed lines indicate the cutoff of P value < 0.05. f Data from the GSE15471 dataset indicated elevated LINC00623 expression levels in PDAC tissues compared with paired adjacent normal tissues (n = 39). g The expression levels of LINC00623 in PDAC (n = 179) and normal pancreatic tissues (n = 171) from TCGA and GTEx, respectively. h The relative expression of LINC00623 as measured by qRT‒PCR in pancreatic cancer and normal cell lines. Exosomes from cell culture supernatant were characterized by nanoparticle tracking analysis (i), Western blotting (j) and transmission electron microscopy (k). l The relative expression of LINC00623 in exosomes isolated from the culture supernatant of pancreatic cell lines. m The expression of exosomal LINC00623 in the culture supernatant of pancreatic cell lines was positively correlated with the expression of LINC00623 in pancreatic cells. n Kaplan–Meier overall survival curves for two groups of patients with PDAC from the other cohort (n = 40): LINC00623(+), patients with high LINC00623 expression; LINC00623(−), patients with low LINC00623 expression. The expression of LINC00623 was determined by qRT‒PCR. o The protein-coding potential of LINC00623 was assessed with CPAT and CPC2 software. The values are expressed as the mean±SD of three independent experiments (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; independent Student’s t test).

Additional file 13: Figure S2. LINC00623 shows strong tumorigenic ability. a RT‒qPCR showed the expression of LINC00623 in cells treated with scrambled shRNA (sh-luc) or shRNA against LINC00623. Gapdh was used as the loading control. b Representative images of foci formed by the indicated cells. c Representative images of the wound healing assay. d Representative images of the migration and invasion assays in the indicated cells. e Overexpression of LINC00623 in BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells was confirmed by RT‒qPCR. f A CCK-8 assay was used to determine cell proliferation rates. LINC00623 significantly increased the efficiency and frequency of foci formation (g) and cell mobility (h), migration and invasion (i) abilities. Quantitative analysis results are shown in the bar chart. (f-i) The values are expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; independent Student’s t test). j The protein expression levels of E-cadherin, N-cadherin and Vimentin in BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells were determined by Western blotting. GAPDH was used as the loading control. k Graphical diagram of the establishment of patient‐derived organoid (PDO) models derived from fresh PDAC tissues (lower). Representative CT scans of target lesions in the patients used for PDO establishment (upper). l Knockdown of LINC00623 in PDOs was confirmed by RT‒qPCR. m Representative images of H&E staining and IHC staining with anti-PCNA and anti-Vimentin antibodies in PDO2. The organoid diameter (n) and scores of IHC staining with anti-PCNA (o) and anti-Vimentin (p) antibodies in two PDOs are summarized in the bar chart. q The scores of IHC staining with an anti-PCNA antibody in tumors formed by the indicated cells (*P<0.05, **P<0.01; independent Student’s t test).

Additional file 14: Figure S3.a Subcellular localization of LINC00623 (red) as detected by RNA FISH in BxPC-3 cells. DAPI (blue) was used for nuclear counterstaining. Scale bar=10 μm. b The expression of LINC00623 in the cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts of BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells was determined by RT‒qPCR. Gapdh and U6 were used as the internal controls for the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, respectively. c Mapping of full-length LINC00623 and a series of deletion mutants of LINC00623. d RT‒PCR was used to confirm the transfection of plasmids containing the full-length sequence and specific deletion sequences of LINC00623. e Mapping of the wild-type (WT) NAT10 protein and specific truncations of NAT10. f Transfection of WT and specific truncations of NAT10 was confirmed by Western blotting using an antibody against FLAG.

Additional file 15: Figure S4.a The relative mRNA levels of NAT10 in BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells with LINC00623 knockdown. b The protein levels of NAT10 in cells after chloroquine (CQ, 10 μM) treatment for 6 hours. c The ubiquitination levels of NAT10 in PANC-1 cells were determined by Western blotting. PANC-1 cells were transiently transfected with LINC00623 knockdown, LINC00623 overexpression and control plasmids and then treated with 10 μM MG132 for 4 hours before cell lysates were harvested for co-IP using an antibody against NAT10. d Venn diagram for identifying two candidate deubiquitinases (DUBs) overlapping with the potential binding proteins of LINC00623. e Western blotting was performed to investigate the specific association of USP39 with biotinylated LINC00623. Lysates of BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells were harvested for RNA pulldown assays. LINC00623 antisense RNA was used as the negative control. f RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation (RIP) assays were performed using an antibody against USP39. RT‒PCR was used to detect LINC00623 enrichment. IgG was used as the isotype control. g The colocalization of USP39 (green) and LINC00623 (red) in BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells was analyzed by IF staining. Scale bar = 10 μm. h The colocalization of NAT10 (green) and USP39 (red) in PANC-1 cells was evaluated by IF staining. Scale bar = 10 μm (left). The percentage of colocalization (Mander’s coefficients) of NAT10 and USP39 is summarized in the bar charts (right). i The ubiquitination level of NAT10 was determined by Western blotting. PANC-1 cells were transiently transfected with USP39 silencing (left), USP39 overexpression (right) and control plasmids and then treated with 10 μM MG132 for 4 hours before cell lysates were harvested for co-IP using an antibody against NAT10.j The protein levels of NAT10 in BxPC-3 cells treated with cycloheximide (CHX, 50 μg/ml) for 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 hours. BxPC-3 cells were transiently transfected with USP39 silencing (upper), USP39 overexpression (lower) or control plasmids. k The protein levels of Flag-NAT10 and Myc-USP39 in BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells were determined by Western blotting. Increasing amounts of the Myc-USP39-WT or Myc-USP39-MUT (C306A) construct were transiently transfected into BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells with Flag-NAT10 overexpression, and cell lysates were then harvested for Western blotting. l The protein levels of NAT10 in BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells transiently transfected with the Myc-USP39-WT or Myc-USP39-MUT (C306A) construct.

Additional file 16: Figure S5.a The scores of IHC staining with an anti-NAT10 antibody in PDAC and matched adjacent normal pancreatic tissues. b Kaplan–Meier analysis of overall survival in patients with PDAC in TCGA. NAT10 (+): high NAT10 expression; NAT10(-): low NAT10 expression. c The protein level of NAT10 in pancreatic cancer and normal cell lines. d The protein levels of NAT10 in the knockdown and overexpression systems were confirmed by Western blotting. e-f Representative images of foci formation assays using BxPC-3 cells transfected with the indicated plasmids (left). The results are summarized in the bar charts (right). g-h Representative images of Transwell assays using BxPC-3 cells transfected with the indicated plasmids (left). The results are summarized in the bar charts (right). (e-h) The values are expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. P value was shown as * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, independent Student’s t test. i Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) tracks displaying the peaks across the mRNA full length of KCNND, PHGDH and LAMB3 according to the results of NAT10 RIP-seq (upper) and ac4C RIP-seq (lower). j Representative images of IHC staining (KCNND, PHGDH and LAMB3) in PDAC or matched adjacent normal pancreatic tissues (NP).

Additional file 17: Figure S6. The scores of IHC staining with anti-PCNA, NAT10, E-cad and N-cad of xenograft tumors in PDX1 (a) and PDX2 (b) models.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients participating in the study for their courage and generosity.

Abbreviations

- PDAC

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- LncRNA

Long noncoding RNA

- AUC

Area under the curve

- ac4C

N4-acetylcytidine

- FISH

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- IF

Immunofluorescence staining

- PDOs

Patient-derived organoids

- EV

Extracellular vesicle

- ASO

Antisense oligonucleotide

- CP

Chronic pancreatitis

- IPMN

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm

- MCN

Mucinous cystic neoplasm

- PNET

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor

- SCN

Serous cystic neoplasm

- EMT

Epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- shRNAs

Short hairpin RNAs

- CCK-8

Cell counting kit-8

- PDX

Patient-derived xenograft

- RT-qPCR

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- HR

Hazard ratio

- 95% CI

95% confidence interval

- GEO

Gene expression omnibus

- TMA

Tissue microarray

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TNM

Tumor, node, metastasis

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- RIP-seq

RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing

- Ribo-seq

Ribosome profiling sequencing

Author contributions

Z.F., L.J. and C.P. initiated and designed the experiments; Z.F., K.L., K.Q. and J.L. performed the experiments; Z.F., K.L., K.Q. and J.L. analyzed the data and interpreted the data; M.S., H.L., Y.M. and Z.F. performed statistical analyses; H.L., S.Z. and B.S. provided clinical samples and the relevant clinical information; B.S. and H.C. provided valuable comments; L.J. and Z.F. drafted the manuscript; B.S., H.C. and C.P. revised the manuscript and supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81470894, 81802316, 81871906, 82073326, 82173226, 82173219), Shanghai Rising-Star Program grant (19QA1405700), Shanghai Municipal Education Commission-Gaofeng Clinical Medicine Grant Support (RC20200037), Medical-Engineering Cross Foundation of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (ZH2018ZDA01), Shanghai Pilot Program for Basic Research-Shanghai Jiao Tong University (21TQ1400205), and Shanghai Collaborative Innovation Center for Translational Medicine (TM201903).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and The Cancer Genome atlas (https://cancergenome.nih.gov/) databases. R code is available upon request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of Ruijin Hospital affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University approved the study. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Consent to publish has been obtained from all authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article has been retracted. Please see the retraction notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-023-01506-5"