Abstract

Ethnopharmacological relevance

There are plant species used in the Mexican traditional medicine for the empirical treatment of anxiety and depression.

Aim of the study

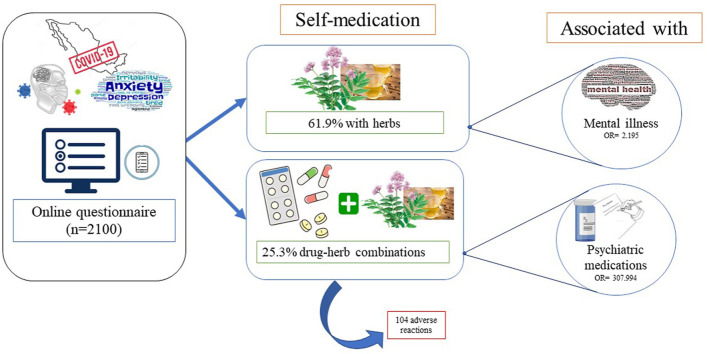

This work assessed the prevalence of self-medication with medicinal plants and the prevalence of the concomitant use of prescribed psychiatric drugs and medicinal plants for treating symptoms associated with anxiety and depression during the Covid-19 lockdown in Mexico.

Materials and methods

The suspected adverse reactions associated with drug-herb interactions were assessed. The factors associated with self-medication, the concomitant use of herb-drug combinations, and the presence of adverse reactions due their combined use is also reported. The study was descriptive and cross-sectional using an online questionnaire conducted among population with symptoms associated with anxiety and depression (n = 2100) from seven states of central-western Mexico.

Results

The prevalence of the use of herbs (61.9%) and the concomitant use of drug-herb combinations (25.3%) were associated with being diagnosed with mental illness [OR:2.195 (1.655–2.912)] and the use of psychiatric medications [OR:307.994 (178.609–531.107)], respectively. The presence of adverse reactions (n = 104) by the concomitant use of drug-herb combinations was associated with being unemployed [p = 0.004, OR: 3.017 (1.404–6.486)].

Conclusion

Health professionals should be aware if their patients concomitantly use medicinal plants and psychiatric drugs. Public health campaigns should promote the possible adverse reactions that might produce the concomitant use of drug-herb combinations for mental illnesses.

Keywords: Herbal products, Anxiety, Depression, Self-medication

Abbreviations: Adverse reactions, ARs; Coronavirus disease 2019, Covid-19; Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM; Odd ratio, OR; Symptoms associated with anxiety and depression, SAAD; World Health Organization, WHO

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Worldwide, there are approximately 300 million people living with depression and more than 260 million people with anxiety. In many cases, both conditions can be diagnosed at the same time (WHO, 2017). Depressive and anxiety disorders produce significant levels of disability, affecting physical, mental, and social functions, and they are also associated with an increased risk of premature death (Griebel and Holmes, 2013). The presence of severe mental diseases is also associated with low socioeconomic status and low educational level (Fryers et al., 2005).

In Mexico, the most recent data indicate that one in five individuals might have at least one mental disorder at some point in life (Valencia, 2018). Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent (14.3% of the population) and the most chronic, followed by substance use (9.2%) and affective (9.1%) disorders, of which depression is the most prevalent (7.2%) (Medina-Mora et al., 2007). Moreover, anxiety and depression disorders occur more frequently in women than in men (Medina-Mora et al., 2007). The age of onset of most psychiatric disorders is around 21 years (Rafful et al., 2012). The central-western region of Mexico has the highest prevalence of mental disorders, which is 36.7%, whereas the national prevalence is 28.6% (Medina-Mora et al., 2003). According to Valencia (2018) less than 10% of patients with anxiety and depression disorders in Mexico seek medical attention. However, current psychiatric drugs might induce side effects, such as sexual dysfunction, metabolic syndrome, dependency, weight-gain, etc. (Gao et al., 2011). This could open the possibility of patients self-medicating with alternative products like herbs. Approximately 49 plant species are used in traditional Mexican medicine for the treatment of anxiety and depression (López-Ruvalcaba and Estrada-Camarena, 2016). However, only 27 of these plants have been scientifically studied in preclinical models and only 4 plants have been studied in clinical trials (López-Ruvalcaba and Estrada-Camarena, 2016). The prevalence of the most common herbs used to treat symptoms associated with anxiety and depression (SAAD) in Mexico is unknown.

On 30th January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak of Covid-19 registered in China to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, and on March 11th the WHO declared Covid-19 to be pandemic (WHO, 2020). The first case of Covid-19 in Mexico was confirmed on February 28th, 2020 (Secretaría de Gobernación, 2020). Approximately, 25–50% of the world population has experienced anxiety and depression during the Covid-19 pandemic (Li et al., 2020; Zhang and Ma, 2020; Özdin and Bayrak Özdin, 2020). In Mexico, the prevalence of severe anxiety and depression during the Covid-19 lockdown ranges from 20.8% to 48% (Galindo-Vázquez et al., 2020; Pérez-Cano et al., 2020; Teran-Perez et al., 2020). Anxiety and depression are increased during the Covid-19 pandemic due to the increase of sensationalized news and misinformation, the fear of getting infected themselves or family members (Pérez-Cano et al., 2020). The main objective of this work was to assess the prevalence of self-medication with medicinal plants for the treatment of SAAD during the Covid-19 lockdown in Mexico. This study describes the prevalence of the concomitant use of herb-drug combinations for the treatment of SAAD. In addition, adverse reactions (ARs) associated with the concomitant use of herbs and psychiatric medications are also reported. The factors associated with self-medication, the concomitant use of drug-herb combinations, and the presence of ARs due to the concomitant use of drug-herb combinations is also reported. This information that entails what medicinal herbs are commonly used for the treatment of SAAD is useful for mental health professionals and general practitioners.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

This descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out from March 2020 to June 2020, during the Covid-19 lockdown in Mexico. Seven states located in the central-western region of Mexico (Queretaro, Michoacán, San Luis Potosí, Mexico City, State of Mexico, Guanajuato, and Jalisco) were included in the study. Participants were asked to complete an online questionnaire that included sociodemographic characteristics (gender, age, education, employment situation, etc.), socio-economic characteristics (number of rooms, number of bathrooms, numbers of occupants, and relationship to interviewee, etc.), which were calculated according to the Mexican Association of Market and Public Opinion Research Agencies (2018), presence of SAAD, presence of comorbidities, use of herbs for the treatment of SAAD, use of psychiatric medications, and concomitant use of drug-herb combinations.

2.2. Research implementation

The anonymity of respondents was maintained. The main variable of interest in this study was the use of medicinal herbs for the treatment of SAAD during the Covid-19 pandemic. The inclusion criteria were as follows: general population presenting SAAD and older than 18 years old. The duration of each survey was 5 min. The protocol of this study was approved by the Institutional Committee of Bioethics in Research (University of Guanajuato, protocol number CIBIUG-P18-2020).

2.3. Diagnostic criteria

The presence of SAAD was based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). A professional psychologist (Miriam Ortiz-Cortes, M. Sc.) evaluated all the data obtained about the DSM-IV criteria. The validity of this survey was evaluated with the assistance of two highly qualified co-workers in the scientific area.

2.4. Sample size estimation

The appropriate population size for this study was estimated using the Raosoft software (Raosoft, Inc. free online software, Seattle, WA, USA). The population residing in these seven states is approximately 46.3 million people, representing 42% of the national population. It was estimated that at least 20% of the Mexican population could be affected by anxiety and depression at some point in their life (Valencia, 2018; Medina-Mora et al., 2007). Therefore, 9.2 million residents were considered as the sample population. The margin of error (3%), the confidence level (99%), and the response distribution (50%) were calculated. Thus, a sample size of at least 1843 respondents was necessary.

2.5. Plant identification

The informants were requested to provide a brief botanical description of the medicinal plant. The specimens mentioned by the respondents were collected in different areas from Mexico. We requested herb companies from different regions of the country to collaborate in providing herbal samples before their process. In some cases, we had the opportunity to collect medicinal plants from their plantations. We also contributed to the proper identification of medicinal plants at no cost. For further reference, samples of plant species were preserved and identified in the herbarium Isidro Palacios (SLPM), Universidad Autonoma de San Luis Potosi, Mexico [Autonomous University of San Luis Potosi, Mexico]. The scientific names of the plant species and the family were searched in specialized bibliographies.

2.6. Data analysis

The Horn algorithm was used to determine whether the drug-herb interaction produced ARs, considering that herbal products were the precipitant drug, whereas the allopathic medicine was the object drug (Horn et al., 2007). The interactions between allopathic medicine and herbs were documented according to the Micromedex® database (DRUG-REAX System, 2009), Lexicomp® Drug Interactions for UpToDate (Jobson, 2017) and the Stockley book (Stockley, 2002). If the drug-herb interaction is not found in these databases, it is considered as a missing report.

All responses reflected a congruent temporal relationship between the ARs and the use of the precipitant drug. Other alternative causes were considered, such as herbal products without knowing their components and quantity. Signs and symptoms referred by the respondents were taken as an objective evidence of the relationship between the ARs and the precipitant drug. The evaluations were carried out by two independent researchers, who discussed each case to reach an agreement. The findings are presented as the mean (standard deviations), percentages and odd ratios (95% CI), when specified. A chi-square test examined associations between socio-demographic and socio-economic information, the self-medication with herbs for SAAD, and the concomitant use of drug-herb combinations. Statistical examination was executed using the software SPSS v20 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Statistical significance was set as p<0.05.

3. Results

The results showed that most of the respondents were women (57.5%), with an average age of 32.08 ± 13.57 years, with a high level of education (64.6%), single (70%), working (44.3%), and a middle socioeconomic status (63.6%) (Table 1 ). Approximately 14.3% of the respondents were diagnosed with mental illness and 19.2% of them used psychiatric medication prescribed by a physician. Findings indicated that 61.9% of the participants self-medicated with herbal products to treat SAAD (Table 1). Female gender, age (>40 years), low educational level (elementary and middle school), marital status (single), unemployment, having private health insurance program, being diagnosed with mental illness, the use of psychiatric medication, and consumption of drugs were the factors associated (p < 0.05) with self-medication (Table 1). Among these factors, respondents diagnosed with mental illness [OR:2.195 (1.655–2.912)], the use of psychiatric medication [OR:2.170 (1.696–2.777)] and having a private health insurance program [OR:1.657 (1.088–2.524)] were the factors that were associated with a higher probability of self-medication with herbal products used for the treatment of SAAD (Table 1).

Table 1.

Factors associated with the self-medication of herbal products used for the treatment of SAAD in adults.

| Characteristics | TOTAL N = 2100 |

Self-medication of herbal products Frequency [n (%)] |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YES n = 1300 (61.9) | NO N = 800 (38.1) |

p | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 1207 (57.5) | 775 (59.6) | 432 (54) | 0.011 | 1.257 (1.053–1.502) |

| Male | 893 (42.5) | 525 (40.4) | 368 (46) | ||

| Age group, years (mean ± SD) | 32.08 ± 13.57 | 32.71 ± 13.82 | 31.05 ± 13.09 | 0.006 | – |

| 18-29 | 1207 (57.5) | 719 (55.3) | 488 (61) | 1 | Ref. |

| 30-39 | 519 (24.7) | 237 (18.2) | 137 (17.1) | 0.189 | 1.174 (0.924–1.492) |

| >40 | 374 (17.8) | 344 (26.5) | 175 (21.9) | 0.009 | 1.334 (1.076–1.655) |

| Level of education | |||||

| Elementary and middle school | 280 (13.3) | 188 (14.5) | 92 (11.5) | 0.041 | 1.328 (1.011–1.743) |

| High school | 464 (22.1) | 290 (22.3) | 174 (21.8) | 0.473 | 1.083 (0.871–1.345) |

| College-postgraduate | 1356 (64.6) | 822 (63.2) | 534 (66.8) | 1 | Ref. |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married/cohabitant | 629 (30) | 425 (32.7) | 204 (25.5) | < 0.001 | 1.419 (1.166–1.728) |

| Single/divorced/widow | 1471 (70) | 875 (67.3) | 596 (74.5) | ||

| Employment status | |||||

| Student | 762 (36.3) | 459 (35.6) | 303 (37.9) | 1 | Ref |

| Employed | 931 (44.3) | 560 (43.1) | 371 (46.4) | 0.971 | 0.996 (0.819–1.212) |

| Unemployed | 407 (19.4) | 281 (21.6) | 126 (15.8) | 0.003 | 1.472 (1.140–1.900) |

| Socioeconomic status | |||||

| High | 622 (29.6) | 38 (29.8) | 234 (29.3) | 0.453 | |

| Middle | 1335 (63.6) | 817 (62.8) | 518 (64.8) | NS | |

| Low | 143 (6.8) | 95 (7.3) | 48 (6) | ||

| Health insurance program | |||||

| Public | 1594 (75.9) | 968 (74.5) | 626 (78.3) | 1 | Ref |

| None | 392 (18.7) | 250 (19.2) | 142 (17.8) | 0.267 | 1.139 (0.905–1.432) |

| Private | 114 (5.4) | 82 (6.3) | 32 (4) | 0.018 | 1.657 (1.088–2.524) |

| Diagnosed with mental illness | |||||

| Yes | 300 (14.3) | 229 (17.6) | 71 (8.9) | <0.001 | 2.195 (1.655–2.912) |

| No | 1800 (85.7) | 1071 (82.4) | 729 (91.1) | ||

| Use of psychiatric medication | |||||

| Yes | 404 (19.2) | 305 (23.5) | 99 (12.4) | <0.001 | 2.170 (1.696–2.777) |

| No | 1696 (80.8) | 995 (76.5) | 701 (87.6) | ||

| Consumption of drugs | |||||

| Yes | 309 (14.7) | 211 (16.2) | 98 (12.3) | 0.012 | 1.388 (1.073–1.796) |

| No | 1791 (85.3) | 1089 (83.8) | 702 (87.8) | ||

| Consumption of alcohol | |||||

| Yes | 901 (42.9) | 575 (44.2) | 326 (40.8) | 0.118 | 1.153 (0.965–1.379) |

| No | 1199 (57.1) | 725 (55.8) | 474 (59.3) | ||

| Presence of symptoms associated with | |||||

| Anxiety | 296 (14.1) | 208 (16) | 88 (11) | <0.001 | 1.691 (1.287– 2.220) |

| Depression | 497 (23.7) | 330 (25.4) | 167 (20.9) | 0.002 | 1.413 (1.139–1.754) |

| Anxiety and depression | 1307 (62.2) | 762 (58.6) | 545 (68.1) | 1 | Ref. |

A total of 11 plant species were taxonomically identified (Table 2 ). It was not possible to identify other medicinal plants due the lack of botanical information provided by the respondents. The most common herbs used to treat SAAD were in the following order: orange blossom [Citrus × aurantium L. (Rutaceae)], chamomile [Matricaria chamomilla L. (Asteraceae)], valerian [Valeriana sorbifolia Kunth (Caprifoliaceae)], tilia [Tilia mexicana Schltdl. (Malvaceae)], and passion flower [Passiflora edulis Sims (Passifloraceae)] (Table 2). Other used herbs were cinnamon [Cinnamomum verum J. Presl (Lauraceae)], ginkgo [Ginkgo biloba L (Ginkgoaceae)], toronjil [Agastache mexicana (Kunth) Lint & Epling (Lamiaceae)], hierba de San Juan [Macrosiphonia hypoleuca (Benth.) Müll. Arg. (Apocynaceae)], cedrón [Aloysia citrodora Paláu (Verbenaceae)], and marijuana [Cannabis sativa L. (Cannabaceae)].

Table 2.

Use of herbs for symptoms associated with anxiety and depression during the Covid- 19 pandemic among Mexican population.

| Medicinal plants contained in products | Citrus × aurantium [SLPM 46949], N = 524 (%) |

Matricaria chamomilla [SLPM 10445] N = 508 |

Valeriana sorbifolia [SLPM 40223] N = 419 |

Tilia mexicana [SLPM 32890] N = 360 |

Passiflora edulis [SLPM 32890] N = 353 |

Cinnamomum verum [SLPM 39788] N = 171 |

Ginkgo biloba [SLPM 10408] N = 153 |

Agastache mexicana [SLPM 39750] N = 134 | Macrosiphonia hypoleuca [SLPM 44477] N = 110 | Aloysia citrodora (SLPM 37141) N = 90 | Cannabis sativa [SLPM 3802] N = 44 | Unidentified N = 194 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 month | 170 (32.4) | 166 (32.7) | 112 (26.7) | 88 (24.4) | 104 (29.5) | 44 (25.7) | 38 (24.8) | 25 (18.7) | 15 (13.6) | 20 (22.2) | 5 (11.4) | 46 (23.7) |

| 1–3 months | 143 (27.3) | 123 (24.2) | 127 (30.3) | 106 (29.4) | 100 (28.3) | 49 (28.7) | 35 (22.9) | 35 (26.1) | 29 (26.4) | 20 (22.2) | 7 (15.9) | 73 (37.6) |

| 3–6 months | 75 (14.3) | 76 (15) | 55 (13.1) | 47 (13.1) | 43 (12.2) | 27 (15.8) | 22 (14.4) | 16 (11.9) | 20 (18.2) | 13 (14.4) | 10 (22.7) | 30 (15.5) |

| 6–12 months | 65 (12.4) | 64 (12.6) | 60 (14.3) | 50 (13.9) | 47 (13.3) | 21 (12.3) | 28 (18.3) | 25 (18.7) | 26 (23.6) | 15 (16.7) | 6 (13.6) | 21 (10.8) |

| >12 months | 71 (13.5) | 79 (15.6) | 65 (15.5) | 69 (19.2) | 59 (16.7) | 30 (17.5) | 30 (19.6) | 33 (24.6) | 20 (18.2) | 22 (24.4) | 16 (36.4) | 24 (12.4) |

| Relative/friend | 321 (61.3) | 296 (58.3) | 252 (60.1) | 219 (60.8) | 197 (55.8) | 102 (59.6) | 82 (53.6) | 83 (61.9) | 57 (51.8) | 49 (54.4) | 27 (61.4) | 114 (58.8) |

| Own initiative | 140 (26.7) | 158 (31.1) | 106 (25.3) | 96 (26.7) | 104 (29.5) | 43 (25.1) | 43 (28.1) | 33 (24.6) | 29 (26.4) | 27 (30) | 13 (29.5) | 51 (26.3) |

| Media | 33 (6.3) | 30 (5.9) | 22 (53) | 15 (4.2) | 17 (4.8) | 15 (8.8) | 8 (5.2) | 7 (5.2) | 9 (8.2) | 5 (5.6) | 0 | 15 (7.7) |

| Herbalist | 29 (5.5) | 24 (4.7) | 38 (9.1) | 30 (8.3) | 33 (9.3) | 11 (6.4) | 20 (13.1) | 11 (8.2) | 15 (13.6) | 9 (10) | 4 (9.1) | 14 (7.2) |

| Deterioration | 5 (1) | 2 (0.4) | 5 (1.2) | 4 (1.1) | 5 (1.4) | 3 (1.8) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.2) | 3 (2.7) | 3 (3.3) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (1) |

| Improvement | 344 (65.6) | 324 (63.8) | 295 (70.4) | 253 (70.3) | 242 (68.6) | 115 (67.3) | 110 (71.9) | 95 (70.9) | 89 (80.9) | 59 (65.6) | 36 (81.8) | 137 (70.6) |

| No effect | 175 (33.4) | 182 (35.8) | 119 (28.4) | 103 (28.6) | 106 (30) | 53 (31) | 42 (27.5) | 36 (26.9) | 18 (16.4) | 28 (31.1) | 7 (15.9) | 55 (28.4) |

| Concomitant use with | ||||||||||||

| Another plant | 431 (82.3) | 417 (82.1) | 361 (86.2) | 344 (95.6) | 317 (89.8) | 106 (62) | 102 (66.7) | 130 (97) | 93 (84.5) | 77 (85.6) | 13 (29.5) | 165 (85.1) |

| Allopathic drug | 157 (30) | 112 (22) | 127 (30.3) | 105 (29.2) | 107 (30.3) | 48 (28.1) | 45 (29.4) | 42 (31.3) | 32 (29.1) | 21 (23.3) | 13 (29.5) | 51 (26.3) |

Most of the plants were used for 1–3 months and were recommended mainly by a relative/friend (Table 2). Most of the participants perceived an improvement in their mental health status after consuming the medicinal herbs (Table 2).

The medicinal plants were combined with at least another medicinal plant (61.2% of the cases) and the prevalence of the concomitant use of herb-drug was 25.3% (Table 3 ). Age (>40 years), low level of education, unemployment, presence of symptoms associated with anxiety, the use of psychiatric medication, presence of symptoms associated with depression, diagnosed with mental illness, having a public health insurance program, and using two or more medicinal herbs were the factors associated (p < 0.05) with the concomitant use of drug-herb combinations (Table 3). Among these factors, the use of psychiatric medication [OR:307.994 (178.609–531.107)], being diagnosed with mental illness [OR: 12.039 (8.695–16.669)], and age (>40 years) [OR: 2.569 (1.920–3.437)] were the factors that were associated with a higher probability of the concomitant use of drug-herb combinations (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with self-medication of concomitant use of drug-herb combinations for the treatment of SAAD in adults.

| Characteristics | Frequency of concomitant drug herb use [n (%)] |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YES n = 329 (25.3) | NO N = 971 (74.7) |

p | OR (95% CI) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 196 (59.6) | 579 (59.6) | 0.986 | 0.998 (0.773–1.287) |

| Male | 133 (40.4) | 392 (40.4) | ||

| Age group, years (mean ± SD) | 36.85 ± 15.53 | 31.31 ± 12.9 | <0.001 | – |

| 18–29 | 140 (42.6) | 579 (59.6) | 1 | Ref. |

| 30–39 | 60 (18.2) | 177 (18.2) | 0.164 | 1.265 (0.908–1.764) |

| > 40 | 129 (39.2) | 215 (22.1) | <0.001 | 2.569 (1.920–3.437) |

| Level of education | ||||

| Elementary and middle school | 65 (19.8) | 123 (12.7) | 0.002 | 1.711 (1.216–2.406) |

| High school | 70 (21.3) | 220 (22.7) | 0.853 | 1.030 (0.753–1.409) |

| College-postgraduate | 194 (59) | 628 (64.7) | 1 | Ref |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/cohabitant | 115 (35) | 310 (31.9) | 0.311 | 1.146 (0.880–1.492) |

| Single/divorced/widow | 214 (65) | 661 (68.1) | ||

| Employment status | ||||

| Student | 96 (29.2) | 363 (37.4) | 1 | Ref |

| Employed | 150 (45.6) | 410 (42.2) | 0.029 | 1.383 (1.033–1.853) |

| Unemployed | 83 (25.2) | 198 (20.4) | 0.008 | 1.585 (1.127–2.229) |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| High | 101 (30.7) | 287 (29.6) | 0.528 | |

| Middle | 200 (60.8) | 617 (63.5) | NS | |

| Low | 28 (8.5) | 67 (6.9) | ||

| Health insurance program | ||||

| None | 40 (12.2) | 210 (21.6) | 1 | Ref. |

| Public | 261 (79.3) | 707 (72.8) | <0.001 | 1.938 (1.343–2.797) |

| Private | 28 (8.5) | 54 (5.6) | 0.162 | 1.405 (0.871–2.265) |

| Diagnosed with mental illness | ||||

| Yes | 159 (48.3) | 70 (7.2) | <0.001 | 12.039 (8.695–16.669) |

| No | 170 (51.7) | 901 (92.8) | ||

| Use of psychiatric medication | ||||

| Yes | 285 (86.6) | 20 (2.1) | <0.001 | 307.994 (178.609–531.107) |

| No | 44 (13.4) | 951 (97.9) | ||

| Consumption of drugs | ||||

| Yes | 44 (13.4) | 167 (17.2) | 0.104 | 0.743 (0.519–1.064) |

| No | 285 (86.6) | 804 (82.8) | ||

| Consumption of alcohol | ||||

| Yes | 133 (40.4) | 442 (45.5) | 0.108 | 0.812 (0.630–1.047) |

| No | 196 (59.6) | 529 (54.5) | ||

| Presence of symptoms associated with | ||||

| Anxiety | 61 (18.5) | 147 (15.1) | <0.001 | 1.691 (1.287–2.220) |

| Depression | 88 (26.7) | 242 (24.9) | 0.002 | 1.413 (1.139–1.754) |

| Anxiety and depression | 180 (54.7) | 582 (59.9) | 1 | Ref. |

| Number of plants in the formulation | 2.62 ± 1.76 | 2.26 ± 1.43 | <0.001 | – |

| 1 plant | 111 (33.7) | 389 (40.1) | 0.042 | 1.313 (1.010–1.706) |

| 2 or more plants | 218 (66.3) | 582 (59.9) | ||

The most frequent used psychiatric medications were clonazepam (n = 62 mentions), fluoxetine (n = 51), diazepam (n = 36), sertraline (n = 35), and escitalopram (n = 17) (Table 4 ). The most frequent drug-herb combinations were: 1) Valeriana sorbifolia-clonazepam (n = 34 mentions), 2) Citrus × aurantium-clonazepam (n = 30), 3) Passiflora edulis-clonazepam (n = 28), 4) Tilia mexicana-clonazepam (n = 26), 5) Matricaria chamomilla-fluoxetine (n = 22), 6) Valeriana sorbifolia-fluoxetine (n = 21), 7) Citrus × aurantium-fluoxetine (n = 21), 8) Passiflora edulis-fluoxetine (n = 18), 9) Tilia mexicana-fluoxetine (n = 18), 10) Citrus × aurantium-diazepam (n = 17), and 11) Citrus × aurantium-sertraline (n = 17) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Frequency of use among drug-herb combinations.

| Concomitant use of drug-herb | N = 329 (%) | Citrus × aurantium N = 157 | Valeriana sorbifolia n = 127 | Matricaria chamomilla N = 112 | Passiflora edulis n = 107 |

Tilia mexicana N = 105 |

Cinnamomum verum n = 48 | Agastache mexicana N = 42 | Ginkgo biloba N = 45 |

Macrosiphonia hypoleuca N = 32 | Aloysia citrodora N = 21 | Cannabis sativa N = 13 |

Unidentified N = 51 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzodiazepines (BZD) | 117 (35.6) | ||||||||||||

| Clonazepam | 62 (18.8) | 30 | 34 | 15 | 28 | 26 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| Diazepam | 36 (10.9) | 17 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| Alprazolam | 14 (4.3) | 3 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Another benzodiazepine | 6 (1.8) | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) | 139 (42.2) | ||||||||||||

| Fluoxetine | 51 (15.5) | 21 | 21 | 22 | 18 | 18 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| Citalopram | 10 (3) | 7 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Escitalopram | 17 (5.2) | 5 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Sertraline | 35 (10.6) | 17 | 16 | 12 | 9 | 11 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Paroxetine | 15 (4.6) | 8 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Other SSRIs | 14 (4.3) | 5 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Another antidepressant drug | 20 (6.1) | 10 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Other medications | 56 (17) | 32 | 20 | 19 | 18 | 18 | 8 | 7 | 14 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 7 |

In 70 patients, a total of 104 ARs were reported, of which, the most frequent were drowsiness (20.2%), followed by dizziness (16.3%), fatigue/tiredness (12.5%), nausea/vomiting (10.6%), headache (8.7%), anxiety (6.7%), and others (25%) including tremors, insomnia, hallucinations, nervousness, fear, anger, depression, hunger, diarrhea, gastritis, stomach pain, tachycardia, and sweating (Table 5 ).

Table 5.

ARs reported with the concomitant use of drug-herb combinations.

| Doubtful |

Possible |

Probable |

Highly probable |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 104 (%) | N = 19 (18.3) | n = 57 (54.8) | N = 26 (25) | n = 2 (1.9) | |

| Neurologic | |||||

| Somnolence | 21 (20.2) | 3 | 12 | 6 | 0 |

| Dizziness/vertigo | 17 (16.3) | 6 | 7 | 4 | 0 |

| Headache | 9 (8.7) | 1 | 7 | 1 | 0 |

| Other neurologic ARs | 4 (3.8) | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Psychiatric | |||||

| Anxiety | 7 (6.7) | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| Depression | 2 (1.9) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Other psychiatric ARs | 5 (4.8) | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal | |||||

| Nausea/vomiting | 11 (10.6) | 2 | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 4 (3.8) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Gastritis | 4 (3.8) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Other gastrointestinal problems | 3 (2.9) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Other AR | |||||

| Fatigue | 13 (12.5) | 2 | 7 | 4 | 0 |

| tachycardia | 2 (1.9) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Sweating | 2 (1.9) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

Table 6 shows the combinations of medicinal herbs and drugs with the highest probability of causality. All ARs have been previously documented. No serious life-threatening side effects were reported. The only two factors associated with the presence of ARs by the concomitant use of drug-herb were being unemployment [p = 0.004, OR: 3.017 (1.404–6.486)] and the consumption of alcohol [p = 0.034, OR: 1.768 (1.039–3.010)] (results not shown).

Table 6.

Description of causality assessment classified as probable among the combinations of drug-herb.

| Documented medicinal plant interaction | No documented medicinal plant interaction | Drugs | Adverse reaction | Evaluation of causality (score) | Determinants of causality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passiflora edulis | Tilia mexicana | Clonazepam | Headache and dizziness | Probable (7) | NO Withdrawal = discomfort continues NO Re-administration Dose-response relationship/AR = positive |

| Passiflora edulis | Tilia mexicana | Fluoxetine | Anxiety | Probable (7) | NO Withdrawal = discomfort continues NO Re-administration Dose-response relationship/AR = positive |

| Passiflora edulis | Matricaria chamomilla - Agastache mexicana | Clonazepam | Sleepiness | Probable (7) | Withdrawal = elimination of the discomfort NO Re-administration Dose-response relationship/AR = non-evaluable |

| Passiflora edulis | – | Clonazepam | Sleepiness | Probable (7) | NO Withdrawal = discomfort continues NO Re-administration Dose-response relationship/AR = positive |

| Passiflora edulis | – | Clonazepam | Sleepiness | Probable (7) | NO Withdrawal = discomfort continues NO Re-administration Dose-response relationship/AR = positive |

| Passiflora edulis |

Tilia mexicana - Citrus × aurantium |

Diazepam | Sleepiness -dizziness | Probable (7) | NO Withdrawal = discomfort continues NO Re-administration Dose-response relationship/AR = positive |

| Passiflora edulis | Matricaria chamomilla - Citrus × aurantium | Fluoxetine | Gastritis | Probable (7) | NO Withdrawal = discomfort continues NO Re-administration Dose-response relationship/AR = positive |

| Passiflora edulis | Matricaria chamomilla - Citrus × aurantium | Fluoxetine | Anxiety and fear | Probable (7) | NO Withdrawal = discomfort continues NO Re-administration Dose-response relationship/AR = positive |

| Passiflora edulis | Tilia mexicana | Sertraline | Nausea and dizziness | Probable (7) | Withdrawal = elimination of the discomfort NO Re-administration Dose-response relationship/AR = non-evaluable |

| Passiflora edulis - Tilia mexicana | – | Clonazepam | Sleepiness | Probable (6) | NO Withdrawal = discomfort continues NO Re-administration Dose-response relationship/AR = non-evaluable |

| Passiflora edulis - |

Tilia mexicana - Citrus × aurantium |

Clonazepam | Fatigue-nausea | Probable (6) | NO Withdrawal = discomfort continues Dose-response relationship/AR = non-evaluable |

| Marijuana | – | Diazepam | Fatigue-hunger | Probable (5) | NO Withdrawal = discomfort continues NO Re-administration Dose-response relationship/AR = negative |

4. Discussion

The main difficulty in this study was the identification of medicinal plants. In many cases, we identified that the same herbal products were sold with different commercial names. This taxonomic information was useful for herb manufacturers considering they were willing to modify the label of their products with the correct name of the medicinal plant. Many companies refused to provide information about the medicinal plant identity contained in their products or they were unwilling to provide an interview due to the pandemic situation. We also should mention that there is a high possibility of undeclared medicinal herbs on the product label. The adulteration of herbal products is a common practice worldwide, even in first-world countries (Cordell and Colvard, 2012). This might represent a potential health risk for consumers (Geck et al., 2020). DNA barcoding and high-resolution melting have been used to distinguish the classification of an unknown plant sample (Kress et al., 2005; Pang et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2017). These techniques should be implemented in the Mexican pharmacopeia to guarantee the quality and safety of herbal products sold in Mexico.

Most of the medicinal plants cited in this work, including Citrus × aurantium, Matricaria chamomilla, Valeriana sorbifolia, Tilia mexicana, Passiflora edulis, Agastache mexicana, Aloysia citrodora, Macrosiphonia hypoleuca Cannabis sativa, and Cinnamomum verum are used in the Mexican traditional medicine for the treatment of anxiety and depression (Berenzon and Saavedra, 2002; Rodríguez-Carranza, 2012; Guzmán-Gutiérrez et al., 2014). Ginkgo biloba is used worldwide for the treatment of anxiety and depression (Woelk et al., 2007). In folk medicine, all these plant species are administered as infusion using aerial parts or whole plant. The following plant species are native to Mexico: Valeriana sorbifolia, Macrosiphonia hypoleuca, Tilia mexicana, and Agastache mexicana.

In a previous study, Berenzon-Gorn et al. (2009) showed that the use of medicinal herbs among patients with anxiety and depression in Mexico City was 15.2% and 9.1%, respectively. In the present study, the results showed that 61.9% of the participants self-medicate with herbal products to treat SAAD. This clearly indicates that Covid-19 lockdown substantially increased the use of medicinal herbs to treat mental disorders such as anxiety and depression among Mexican population. Worldwide, the use of herbs for the treatment of SAAD ranges from 2.28 to 53% (Parslow and Jorm, 2004; Elkins et al., 2005; Roy-Byrne et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2007; Niv et al., 2010; Ravven et al., 2011; Bystritsky et al., 2012; Stojanović et al., 2017; Nikolić et al., 2018). The findings showed that the high levels of self-medication to treat SAAD reported in this study are associated with female gender, age (>40 years), low educational level (elementary and middle school), marital status (single), unemployment, having private health insurance, being diagnosed with mental illness, the use of psychiatric medication, and consumption of drugs. Among these factors, female gender, age (>40 years), being diagnosed with mental illness, and the use of psychiatric medication are consistent with other studies (Parslow and Jorm, 2004; Niv et al., 2010; Vasiladis and Tempier, 2011; Ravven et al., 2011). Being diagnosed with mental illness was the main factor associated with the use of medicinal herbs to treat anxiety and depression in this study [OR:2.195 (1.655–2.912)] and in a previous study [OR:3.45 (1.23–4.65)] in Mexico City (Berenzon-Gorn et al., 2009). Furthermore, a low educational level is consistent with two studies (Stojanović et al., 2017; Nikolić et al., 2018), but it is in contrast with other studies, which indicate that a high educational level was associated with the use of medicinal herbs for the treatment of SAAD (Parslow and Jorm, 2004; Roy-Byrne et al., 2005; Niv et al., 2010; Vasiladis and Tempier, 2011; Ravven et al., 2011). In Canada, a high economic status was related to the use of herbs for the treatment of anxiety and depression (Vasiladis and Tempier, 2011), which is in contrast with the results obtained in this work. Unemployment was a factor associated with self-medication, which is consistent with another study (Wu et al., 2007), but is in contrast with other studies, indicating that working is a main factor for using herbal preparations for the treatment of anxiety and depression (Niv et al., 2010; Ravven et al., 2011). The frequency of psychiatric drugs use (19.2%) reported in this study were higher than those found in other reports, ranging from 5.56 to 9.5% (Parslow and Jorm, 2004; Vasiladis and Tempier, 2011).

The herbs most commonly used to treat SAAD were in the following order: orange blossom, chamomile, valerian, tilia, and passion flower. The most used herbs to treat anxiety and depression reported in other studies were St John's-wort (Parslow and Jorm, 2004; Roy-Byrne et al., 2005; Vasiladis and Tempier, 2011; Ravven et al., 2011), kava-kava (Piper methysticum) (Elkins et al., 2005), garlic and ginko (Niv et al., 2010), melisa (Stojanović et al., 2017; Nikolić et al., 2018), chamomile (Ravven et al., 2011; Bystritsky et al., 2012), and valerian (Nikolić et al., 2018). The findings agree with most of the previous studies.

Some of the herbs most used to treat SAAD have been tested in clinical trials. For instance, C. aurantium essential oil used through inhalation has shown a reduction of the signs and symptoms associated with anxiety in patients with chronic diseases (Pimenta et al., 2016; Moslemi et al., 2019). M. chamomilla, G. biloba, and P. edulis, orally administered, and C. sativa, smoked, decreased symptoms associated with anxiety and depression in acute and long-term studies (Woelk et al., 2007; Mao et al., 2016; Amsterdam et al., 2012; Bahorik et al., 2018).

Most of the respondents perceived a general improvement in their mental health. However, this improvement could not be measured. A study in the United States of America indicated that patients consuming herbs perceived a general improvement in their mental health (Bystritsky et al., 2012). In contrast, a study in Australia showed that respondents who use herbs for anxiety and depression had a worse mental health (Parslow and Jorm, 2004). Most of the plants were used for 1–3 months. This can be explained since the pandemic lockdown lasted between 2-3 months in Mexico. The main source of information for consuming medicinal herbs is a friend or relative, which is consistent with other studies (Stojanović et al., 2017; Nikolić et al., 2018).

The use of multiple herbs for the treatment of anxiety and depression is a common practice, which is consistent with other studies (Ravven et al., 2011; Nikolić et al., 2018). The concomitant use of drug-herb combinations for treating symptoms associated with anxiety and depression is variable, ranging from 0.28 to 50% (Parslow and Jorm, 2004; Niv et al., 2010; Vasiladis and Tempier, 2011; Ravven et al., 2011; Stojanović et al., 2017; Nikolić et al., 2018). In this study, the prevalence of the concomitant use of drug-herb combinations was 25.3%. This can be explained since psychiatric patients want to find alternative therapies to replace the use of medications or reduce the dose of psychiatric drugs.

The ARs induced by the single administration of plants used for the treatment of SAAD have been extensively reported (LaFrance et al., 2000). This work focused on ARs from the concomitant use of drug-herb combinations during the treatment of SAAD. Most of the ARs reported in this study were neurologic. Previously, it was reported that Passiflora edulis induced somnolence in humans (Ngan and Conduit, 2011). This might suggest that medicinal plants such as passion flower could act synergistically with psychiatric medications such as clonazepam. In other studies, some ARs reported with the concomitant use of drug-herb combinations for the treatment of SAAD were dizziness, nightmares, and nausea (Stojanović et al., 2017; Nikolić et al., 2018). Frequently, ARs are associated with older age because seniors consume more drugs and show a slow drug-metabolism. In this study, age was not a factor associated with the presence of ARs during the concomitant use of drug-herb combinations. All ARs for the concomitant use of drug-herb combinations were previously reported.

The general considerations of this work are that many physicians do not ask their patients about the use of herbs or supplements or the concomitant use of drug-herb combinations. Health professionals should be aware if their patients concomitantly use drug-herb combinations to prevent and reduce ARs. In addition, it is necessary to sensitize health personnel about the use of medicinal herbs in patients. This knowledge can improve the physician-patient relationship. Previously, we have shown that Mexican physicians agree to receive scientific information about the use of medicinal herbs (Alonso-Castro et al., 2017). Public health campaigns should promote the possible ARs that might produce the concomitant use of drug-herb combinations for mental illnesses. Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic studies should be carried out with the most common drug-herb combinations. ARs monitorization of drug-herb concomitant use is of great importance. In addition, patients should also ask their physicians before making the decision to consume herbal products.

Regarding herbal products in Mexico, by 2017 there were only 27 phytomedicine patents registered by the Mexican Institute of Industrial Property. This can be attributed, in part, to the low cohesion between university-business-government agencies to increase the innovation of pharmaceutical products in Mexico (Domínguez et al., 2015). Furthermore, many herbal products sold in Mexico lack quality control for efficacy and safety, as well as lack of monitoring of the quality of the finished product and avoid Mexican legislation.

Some limitations of this study include that the results are based on self-reported data, the circumstances of the outbreak due to the Covid-19 pandemic might increase the cases of any mental disorder. The sample in this study cannot be extrapolated to the entire country. It was not possible to obtain a homogenous distribution of individuals. In addition, it is difficult to deduce causality between any of the variables examined in a cross-sectional study.

5. Conclusions

Findings in this study show a high prevalence (61.9%) of self-medication using herbal products to treat SAAD in the central-western region of Mexico. Being diagnosed with mental illness, use of psychiatric medication, and having a private health insurance program were the strongest factors associated with self-medication. There is also a high prevalence (25.3%) of self-medication with the concomitant use of drug-herb combinations. The use of psychiatric medication, being diagnosed with mental illness, and age (>40 years) were the strongest factors associated with the concomitant self-medication of drug-herb combinations.

Author's contribution

All authors participated obtaining surveys. EC identified the plant species. AJRP performed the data analysis. AJAC and MOC designed the study and supervised the project. AJAC wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

Conflict of interest. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Universidad de Guanajuato (Grant/Award Number: DAIP, CIIC 58/2020 provided to AJAC) and Secretariat of Health from the state of Guanajuato, Mexico (grant provided to AJAC).

References

- Alonso-Castro A.J., Domínguez F., Maldonado-Miranda J.J., Castillo-Pérez L.J., Carranza-Álvarez C., Solano E., Isiordia-Espinoza M.A., Del Carmen Juárez-Vázquez M., Zapata-Morales J.R., Argueta-Fuertes M.A., Ruiz-Padilla A.J., Solorio-Alvarado C.R., Rangel-Velázquez J.E., Ortiz-Andrade R., González-Sánchez I., Cruz-Jiménez G., Orozco-Castellanos L.M. Use of medicinal plants by health professionals in Mexico. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017;198:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsterdam J.D., Shults J., Soeller I., Mao J.J., Rockwell K., Newberg A.B. Chamomile (Matricaria recutita) may provide antidepressant activity in anxious, depressed humans: an exploratory study. Alternative Ther. Health Med. 2012;18(5):44–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asociación mexicana de Agencias de Inteligencia de Mercado y opinión [Mexican association of Market intelligence] 2018. http://nse.amai.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Cuestionario-NSE-2018.pdf Available at:

- Bahorik A.L., Sterling S.A., Campbell C.I., Weisner C., Ramo D., Satre D.D. Medical and non-medical marijuana use in depression: longitudinal associations with suicidal ideation, everyday functioning, and psychiatry service utilization. J. Affect. Disord. 2018;241:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.05.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenzon S., Saavedra N. Presencia de la herbolaria en el tratamiento de los problemas emocionales: entrevista a los curanderos urbanos. Salud Ment. 2002;25(1):55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Berenzon-Gorn S., Alanís-Navarro S., Saavedra-Solano N. El uso de las terapias alternativas y complementarias en población mexicana con trastornos depresivos y de ansiedad: resultados de una encuesta en la Ciudad de México. Salud Ment. 2009;32(2):107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bystritsky A., Hovav S., Sherbourne C., Stein M.B., Rose R.D., Campbell-Sills L., Golinelli D., Sullivan G., Craske M.G., Roy-Byrne P.P. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in a large sample of anxiety patients. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(3):266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordell G.A., Colvard M.D. Natural products and traditional medicine: turning on a paradigm. J. Nat. Prod. 2012;75:514–525. doi: 10.1021/np200803m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Gobernación Secretaría. 2020. Acuerdo por el que se declara como emergencia sanitaria por causa de fuerza mayor, a la epidemia de enfermedad generada por el virus SARS-CoV2 (COVID-19) México. Published. [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th Ed. (DSM-IV) American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. American Psychiatric Press, Inc. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez F., Alonso-Castro A.J., Anaya M., González-Trujano M.E., Salgado-Ceballos H., Orozco-Suárez S. In: Therapeutic Medicinal Plants. Rai M., Teixeira-Duarte M.C., editors. CRC Press; United Kingdom: 2015. Mexican traditional medicine: traditions of yesterday and phytomedicines of tomorrow Pp 1-37; p. 400. [Google Scholar]

- DRUG-REAX System [internet Database] Thomson Reuters (Healthcare); Greenwood Village, CO: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Elkins G., Marcus J., Rajab M.H., Durgam S. Complementary and alternative therapy use by psychotherapy clients. Psychother. Theor. Res. Pract. Train. 2005;42(2):232–235. [Google Scholar]

- Fryers T., Melzer D., Jenkins R., Brugha T. The distribution of the common mental disorders: social inequalities in Europe. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health: CP EMH. 2005;1:14. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo-Vázquez O., Ramírez-Orozco M., Costas-Muñiz R., Mendoza-Contreras L.A., Calderillo-Ruíz G., Meneses-García A. Symptoms of anxiety, depression and self-care behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in the general population. Gac. Med. Mex. 2020;156:298–305. doi: 10.24875/GMM.20000266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao K., Kemp D.E., Fein E., Wang Z., Fang Y., Ganocy S.J., Calabrese J.R. Number needed to treat to harm for discontinuation due to adverse events in the treatment of bipolar depression, major depressive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder with atypical antipsychotics. J. Clin. Psychiatr. 2011;72(8):1063–1071. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09r05535gre. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geck M.S., Cristians S., Berger-González M., Casu L., Heinrich M., Leonti M. Traditional herbal medicine in Mesoamerica: toward its evidence base for improving universal health coverage. Front. Pharmacol. 2020;11:1160. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.01160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griebel G., Holmes A. 50 years of hurdles and hope in anxiolytic drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013;12:667–687. doi: 10.1038/nrd4075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán-Gutiérrez S.L., Reyes-Chilpa R., Bonilla-Jaime H. Medicinal plants for the treatment of “nervios”, anxiety, and depression in Mexican Traditional Medicine. Rev. Brasil. Farmacognosia. 2014;24(5):591–608. [Google Scholar]

- Horn J.R., Hansten P.D., Chan L.N. Proposal for new tool to evaluate drug interaction cases. Ann. Pharmacother. 2007;41(4):674–680. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobson M.D. In: Second-generation Antipsychotic Medications: Pharmacology, Administration, and Side Effects. Post T.W., editor. UpToDate Inc; Waltham, MA: 2017. https://www.uptodate.com UpToDate. [Google Scholar]

- Kress W.J., Wurdack K.J., Zimmer E.A., Weigt L.A., Janzen D.H. Use of DNA barcodes to identify flowering plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102(23):8369–8374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503123102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFrance W.C., Jr., Lauterbach E.C., Coffey C.E., Salloway S.P., Kaufer D.I., Reeve A., Royall D.R., Aylward E., Rummans T.A., Lovell M.R. The use of herbal alternative medicines in neuropsychiatry. A report of the ANPA Committee on Research. J. Neuropsychiatr. Clin. Neurosci. 2000;12(2):177–192. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Yang Z., Qiu H., Wang Y., Jian L., Ji J., Li K. Anxiety and depression among general population in China at the peak of the COVID-19 epidemic. World Psychiatr. 2020;19(2):249–250. doi: 10.1002/wps.20758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Rubalcava C., Estrada-Camarena E. Mexican medicinal plants with anxiolytic or antidepressant activity: focus on preclinical research. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016;186:377–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J.J., Xie S.X., Keefe J.R., Soeller I., Li Q.S., Amsterdam J.D. Long-term chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Phytomedicine. 2016;23(14):1735–1742. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Mora M.E., Borges G., Lara C., Benjet C., Blanco J., Fleiz C., Villatoro J., Rojas E., Zambrano J., Casanova L., Aguilar S. Prevalencia de trastornos mentales y uso de servicios: resultados de la Encuesta Nacional de Epidemiología Psiquiátrica en México. Salud Ment. 2003;26:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Mora M.E., Borges G., Benjet C., Lara C., Berglund P. Psychiatric Disorders in Mexico: lifetime prevalence in a nationally representative sample. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2007;190:521–528. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moslemi F., Alijaniha F., Naseri M., Kazemnejad A., Charkhkar M., Heidari M.R. Citrus aurantium aroma for anxiety in patients with acute coronary syndrome: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J. Alternative Compl. Med. 2019;25(8):833–839. doi: 10.1089/acm.2019.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngan A., Conduit R. A double-blind, placebo-controlled investigation of the effects of Passiflora incarnata (passionflower) herbal tea on subjective sleep quality. Phytother Res. 2011;25(8):1153–1159. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolić G., Stojanović N.M., Randjelović P.J., Manojlović S., Radulović N.S. An epidemiological study on herbal product self-medication practice among psychotic outpatients from Serbia: a cross-sectional study. Saudi Pharmaceut. J. 2018;26(3):335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niv N., Shatkin J.P., Hamilton A.B., Unützer J., Klap R., Young A.S. The use of herbal medications and dietary supplements by people with mental illness. Community Ment. Health J. 2010;46(6):563–569. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9235-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özdin S., Bayrak Özdin Ş. Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: the importance of gender. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatr. 2020;66(5):504–511. doi: 10.1177/0020764020927051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang, X. H., Shi, L.C., Song, J.Y., Chen, X.C., & Chen, S.L. Use of the potential DNA barcode ITS2 to identify herbal materials. J. Nat. Med. 67, 571–575. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Parslow R.A., Jorm A.F. Use of prescription medications and complementary and alternative medicines to treat depressive and anxiety symptoms: results from a community sample. J. Affect. Disord. 2004;82(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Cano H.J., Moreno-Murguía M.B., Morales-López O., Crow-Buchanan O., English J.A., Lozano-Alcázar J., Somilleda-Ventura S.A. Anxiety, depression, and stress in response to the coronavirus disease-19 pandemic. Cir. Cir. 2020;88(5):562–568. doi: 10.24875/CIRU.20000561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimenta F.C., Alves M.F., Pimenta M.B., Melo S.A., de Almeida A.A., Leite J.R., Pordeus L.C., Diniz M., de Almeida R.N. Anxiolytic effect of Citrus aurantium L. on patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Phytother Res. 2016;30(4):613–617. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafful C., Medina-Mora M.E., Borges G., Benjet C., Orozco R. Depression, gender and the treatment gap in Mexico. J. Affect. Disord. 2012;138:165–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravven S.E., Zimmerman M.B., Schultz S.K., Wallace R.B. 12-month herbal medicine use for mental health from the national Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Ann. Clin. Psychiatr. 2011;23(2):83–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Carranza R. Los productos de Cannabis sativa: situación actual y perspectivas en medicina. Salud Ment. 2012;35:247–256. [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Byrne P.P., Bystritsky A., Russo J., Craske M.G., Sherbourne C.D., Stein M.B. Use of herbal medicine in primary care patients with mood and anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(2):117–122. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockley I.H., editor. Stockley's Drug Interactions. sixth ed. The Pharmaceutical Press; London, Chicago: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stojanović N.M., Samardžić L., Randjelović P.J., Radulović N.S. Prevalence of self-medication practice with herbal products among non-psychotic psychiatric patients from southeastern Serbia: a cross-sectional study. Saudi Pharmaceut. J. 2017;25(6):884–890. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W., Yan S., Li J., Xiong C., Shi Y., Wu L., Xiang L., Deng B., Ma W., Chen S. Study of commercially available Lobelia chinensis products using Bar-HRM technology. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:351. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teran-Perez G., Arana-Lechuga Y., Velázquez-Moctezuma Cambios en el sueño y la salud mental por el aislamiento social durante la pandemia de Covid 19. Ciencia. 2020;71:66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia M. APM Ediciones y Convenciones en Psiquiatría; 2018. Remisión Y Recuperación Funcional [Remission and Functional Recovery]. En: Depresión, Trastornos Bipolar Y Esquizofrenia [depression, Bipolar Disorders and Schizophrenia] 978-607-8512-88-1. [Google Scholar]

- Vasiladis H.M., Tempier R. Reporting on the prevalence of drug and alternative health product use for mental health reasons: results from a national population survey. Journal of Population Therapeutics and Clinical Pharmacology. 2011;18(1):e33–e43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woelk H., Arnoldt K.H., Kieser M., Hoerr R. Ginkgo biloba special extract EGb 761 in generalized anxiety disorder and adjustment disorder with anxious mood: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2007;41(6):472–480. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) 2020. Novel Coronavirus(2019-nCoV) Situation Report-12. [Google Scholar]

- Wu P., Fuller C., Liu X., Lee H.C., Fan B., Hoven C.W., Mandell D., Wade C., Kronenberg F. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among women with depression: results of a national survey. Psychiatr. Serv. 2007;58(3):349–356. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Ma Z.F. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and quality of life among local residents in Liaoning Province, China: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17(7):238. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]