Abstract

Scientists develop a method that optimizes exoskeleton assistance in one hour and teaches the wearer to walk more economically with it.

For more than a century engineers have been developing wearable devices to reduce the metabolic cost of walking but only in the past four years several groups succeeded in this using ankle exoskeletons (1–3). This slow progress can be attributed to the challenge of identifying the optimal shape of the assistive torque pattern of the exoskeleton over the course of the walking stride. A brute-force approach consists of testing various timing and magnitude settings of the torque pattern and identifying the settings that produce the largest reduction in metabolic cost (1, 3–6). Because obtaining reliable metabolic cost data requires averaging multiple minutes of breath data, the number of settings that one can test is limited. Until now, it was not feasible to optimize the entire shape of the torque pattern. On page … Zhang et al. describe how they implemented an algorithm that optimizes the entire exoskeleton torque pattern in a one hour iterative process with real-time metabolic cost estimations (7). This smart human-in-the-loop algorithm identified an optimal pattern for each participant which resulted in an average reduction of 24% compared to walking with the exoskeleton powered-off. This is slightly better than the best results from previous work (4, 6), and impressive considering that Zhang et al. assisted only one leg.

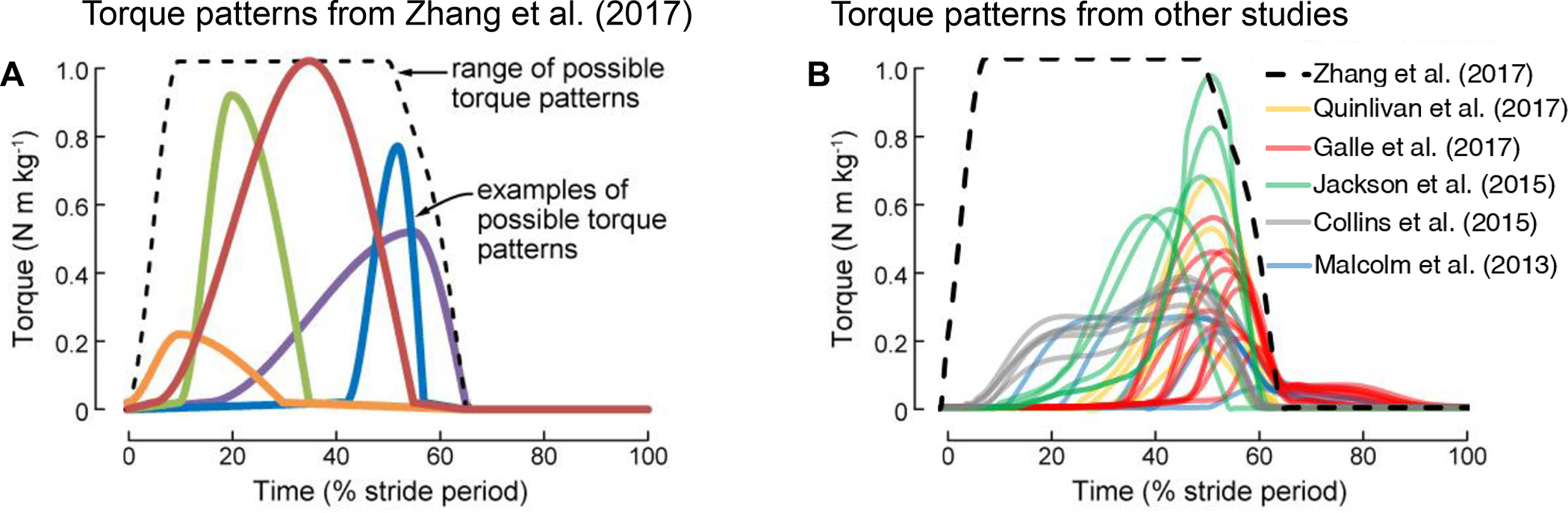

An exciting second outcome was that, after the optimization phase, the average reduction in metabolic cost with a standardized (non-optimized) torque pattern was larger than in a previous experiment with the same pattern and exoskeleton (5). As possible explanation, the authors suggest that the human-in-the-loop algorithm might have facilitated motor learning by exposing participants to a wider variety of torque patterns (Figure 1). Indeed, since the 70’s, scientists showed that variable practice improves skill learning (8). This concept challenged the then prevailing thought that practicing should happen under constant conditions. Variable practice is now applied in sports, physical therapy and learning of skills in professions. So, in the experiment from Zhang et al., the reduction in metabolic cost seems to be obtained through a combination of effective torque pattern optimization and facilitation of motor learning by exposure to a wide variety of torque patterns.

Figure 1: Torque pattern ranges across different studies.

Range of possible torque patterns in Zhang et al. (7) (A). Range of torque patterns in previous studies (1,3,4,5,6) (B). The range in Zhang et al. during adaptation was larger than in all previous studies. This wide variety of actuation patterns could have facilitated motor learning and have contributed to large metabolic reductions.

Perhaps, motor learning could be improved by increasing practice variability. In the field of upper-limb rehabilitation, it is known that robotic devices that amplify movement errors improve training in stroke patients (9). To increase variability in locomotion we can think of alternatives to constant-speed treadmill walking. Non-steady state walking conditions could provide a learning environment that is more realistic and more variable at the same time (Figure 2). In fact, walking during daily life happens on uneven terrain and consists of short bouts (10) with frequent changes in speed. Human-in-the-loop optimization during non-steady state walking would be challenging for the current algorithm that is designed for cyclic gaits. Maybe, walking with an exoskeleton can be practiced separately from the torque pattern optimization, requiring a controller that simply provides a variety of torque patterns. Finding the best method for learning to walking with exoskeletons will require studies with different training modalities with participants who start from an untrained state.

Now that the ability to improve metabolic economy has been demonstrated, improving performance could become a next objective. In the past decade one group was able to produce an increase in preferred walking speed with an ankle exoskeleton (11). Preferred walking speed could be used as objective for a human-in-the-loop algorithm. Such an approach could benefit patients with reduced exercise capacity (e.g. pulmonary impairment).

In conclusion, the study from Zhang et al. demonstrated a solution for optimizing and individualizing exoskeleton torque patterns and gives rise to new questions about motor learning. Thanks to its generalizability it is foreseeable that online optimization will have multiple applications for the development of wearable robotics. Also for human movement science in general we expect that human-in-the-loop optimization will allow new types of experiments where relationships between gait parameters are investigated in real-time rather than by testing static conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank our colleagues for editorial suggestions.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Malcolm P, Derave W, Galle S, De Clercq D, PLoS One. 8, e56137 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mooney LM, Rouse EJ, Herr HM, J Neuroeng Rehabil. 11, 80 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins SH, Wiggin MB, Sawicki GS, Nature (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quinlivan BT et al. , 4416, 1–17 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson RW, Collins SH, J. Appl. Physiol. (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galle S, Malcolm P, Collins SH, De Clercq D, J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 14, 1–16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J et al. , Science (80-. ). (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt RA, Lee TD, Motor learning and performance : From principles to application (Kinetics, Human, Champaign, IL, ed. 5th, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patton JL, Stoykov ME, Kovic M, Mussa-Ivaldi FA, Exp. Brain Res. 168, 368–383 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orendurff MS, Schoen JA, Bernatz GC, Segal AD, Klute GK, J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 45, 1077–1089 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norris JA, Granata KP, Mitros MR, Byrne EM, Marsh AP, Gait Posture. 25, 620–627 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]