Abstract

Context

Metastatic medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) and radioactive iodine–refractory differentiated thyroid carcinoma (RAI-R DTC) have poor prognosis and limited treatment options. Selpercatinib (LOXO-292), a selective kinase inhibitor targeting the RET gene, has shown a 69% to 79% objective response rate in this cohort with benefits in other tumors including lung cancer harboring the same oncogenic driver. Published reports describe only 17% of patients experiencing gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects (AEs), which is in contrast to our local experience.

Objective

Here we characterize the AEs and correlate them with radiological and histopathological findings.

Methods

Sequential patients enrolled in LIBRETTO-001 at Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney, Australia, with available imaging (n = 22) were recruited. Patients had regular visits with AEs documented and computed tomography (CT) scans every 3 months. CT at screening, at time of GI AE, and at most recent follow-up were reviewed and scored. Endoscopic examination was performed in 5 patients.

Results

Of 22 patients in this cohort, the majority had somatic RET alterations (n = 18), most commonly p.Met918Thr (n = 14). Ten patients (50%) developed GI AEs. Dose reduction was required in 8 of the 10 patients, but none discontinued therapy. The majority had stable disease (n = 17). Gastric and small-bowel edema was evident in symptomatic patients after a median time of 67 weeks’ treatment. Histological correlation in 5 patients revealed mucosal edema correlating with radiological evidence of congestion and edema.

Conclusion

GI AEs with selpercatinib may be more common than previously described. Most are self-limiting but often require dose adjustments. Histological evidence of mucosal edema observed in conjunction with the radiological findings of congestion and wall thickening suggest bowel-wall edema is a predominant mechanism of abdominal pain in these patients.

Keywords: selpercatinib, RET mutation, thyroid carcinoma, adverse effects, bowel oedema, radiology, histology

Identifying molecular alterations in thyroid cancer has led to successful targeted therapies particularly in rearranged during transfection (RET)-altered cancers. Metastatic medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) and radioactive iodine–refractory (RAI-R) differentiated thyroid carcinoma (DTC) are associated with poor prognosis and traditionally limited treatment options (1, 2). Both metastatic medullary and DTC can harbor RET alterations upregulating intracellular oncogenic pathways, including RAS/RAF/ERK and phosphatidyl-inositol-3-kinase (P13-kinase)/AKT pathways (3). Constitutive activation of RET is either via point mutations of the cysteine rich and kinase domains, seen in MTC, or via structural fusion mutations in DTC.

MTCs are neuroendocrine tumors arising from parafollicular C cells occurring sporadically in 75% of cases, of which 60% harbor a somatic RET point mutation (4). The remaining 25% are familial and comprise part of the multiple endocrine neoplasia 2 syndrome (MEN2), with germline point mutations in RET (C634R). In MEN3 (previously known as MEN2B), codon 918 is involved in 95% of cases, in a methionine-to-threonine substitution (p.Met918Thr) (5). RET fusion alterations occur in less than 10% of DTC but are overrepresented in pediatric and cancers precipitated by environmental radiation exposure (6-9).

Systemic therapy for metastatic MTC and RAI-R DTC includes multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (MKIs), including vandetanib (10) and cabozantinib (11) for MTC, and sorafenib (12) and lenvatinib (13) for DTC. Phase 3 trials for patients with progressive metastatic disease of DTC report progression-free survival varying between 10.8 and 30.5 months for these MKIs. In MTC, the trials reported for vandetanib an objective response rate of 45%, whereas for cabozantinib it was lower at 28%. In these studies, a large number of adverse effects (AEs) secondary to off-target effects (largely mediated through vascular endothelium growth factor receptor) were observed, which led to a high proportion of dose reductions and interruptions. High rates of hypertension, diarrhea, palmar plantar erythrodysesthesia and prolonged QT syndrome led to cessation of drugs in 12% for vandetanib, 16% for cabozantinib, and 18% for lenvatinib in phase 3 trials and dose interruptions for the 3 drugs at 45%, 79%, and 82.4%, respectively. Thus, impaired quality of life secondary to vascular endothelium growth factor inhibition led to the development of more specific RET kinase inhibitors with fewer off-target effects.

Selpercatinib (formerly LOXO-292) is a novel selective RET inhibitor that has had success without comparable AEs both in MTC and DTC patients. In phase 1 and 2 trials for treatment of RET-altered thyroid cancers (14), including the first 55 MTCs previously treated with TKI, 88 MTCs without previous TKI, and 19 RET fusion–positive DTCs, objective responses were 69%, 73%, and 79%, respectively. AEs were reported in 94% of patients, but only 30% were grade 3 or 4. In contrast to the MKIs described earlier, only 2% of patients discontinued the drug because of AEs, reflecting a much higher degree of tolerance. The main reported AEs were dry mouth (39%), hypertension (30%, 12% grade 3), diarrhea (17%, 3% grade 3), and fatigue (25%, 1% grade 3). Described gastrointestinal (GI) AEs were infrequent and included nausea (15% none grade 3 or 4), constipation (16% none grade 3 or 4), abdominal pain (4% none grade 3 or 4), and abdominal distension (7% none grade 3 or 4). Similar AEs were reported in an accompanying study in non–small cell lung cancer treated with selpercatinib (15). On the basis of these data, selpercatinib was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for RET fusion–mutated non–small cell lung cancer and DTC, and RET-mutated MTC. The drug is now approved for use in some countries as well as via expanded-access programs and through clinical trials.

During LIBRETTO-001, as an international site, we observed an increasing number of patients reporting abdominal and GI AEs. Here, in a retrospective audit of patients currently on selpercatinib, we describe small-bowel edema as a new feature of GI AEs associated with this drug, and detail histopathology and a radiological scoring system to further characterize this finding.

Materials and Methods

All 22 patients enrolled in LIBRETTO-001 at Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney, Australia, were included in this study. The clinical trial was approved by the Northern Sydney Local Health District Ethics Committee. All patients had regular CT scans (every 3 months) and monthly clinical reviews per protocol by clinical trial investigators to assess for potential AEs. Patients also reported AEs in between visits if severe. Additional imaging was occasionally performed if clinically indicated, predominantly to investigate possible AEs.

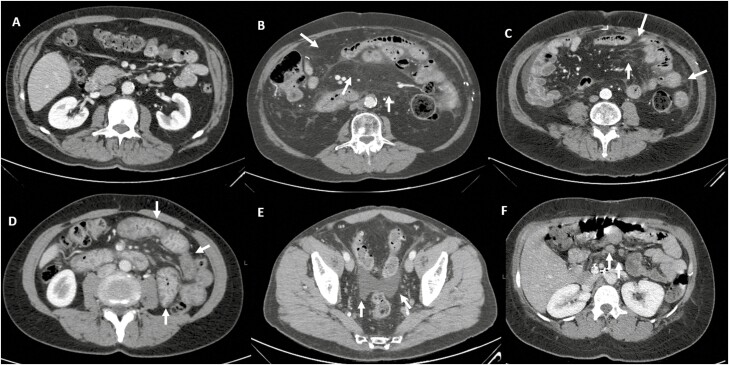

CT imaging from 3 selected time frames (baseline, at symptom onset [or randomly for those without symptoms], and the most recent scan) were reviewed independently by a radiologist (BL) and radiology trainee (LB) blinded to symptom status of the patient. We developed a scoring system for bowel-wall changes including a point each for mesenteric congestion, stranding, bowel-wall thickening/edema, ascites, and lymphadenopathy (ie, a maximum score of 5). Scoring details are described in Table 1 and examples are shown in Fig. 1. For the purpose of this study, mesenteric stranding was defined as a definite increase in density of mesenteric fat, with increased mesenteric vessel caliber and vessel visibility compared with baseline being classified as mesenteric congestion. Bowel-wall thickening was identified by evaluating the bowel wall in segments demonstrating the greatest degree of luminal distension or where intraluminal fluid/gas allowed for clear delineation of true bowel-wall thickness. Ascites was categorized as present by visualizing intraperitoneal fluid, most commonly in the pelvic recesses, paracolic gutters, and adjacent to the liver/spleen. A positive lymphadenopathy score required identification of an increased number of lymph nodes in the mesentery compared to baseline, abnormal lymph node morphology, or enlargement greater than 10 mm along the short axis. While there are multiple radiological findings indicating bowel inflammation that are widely accepted, albeit nonspecific for etiology, no accepted scoring system is available in the literature to facilitate the assessment of treatment-related enteritis and colitis. Recognized features of bowel inflammation were considered to develop a scoring system for this study to allow more objective comparison of the CT studies reviewed during treatment.

Table 1.

Computed tomography scoring system and description

| Feature | Present |

|---|---|

| Ascitic fluid | Peritoneal free fluid |

| Bowel wall thickening | Mural thickening in segments with luminal distention/fluid/gas |

| Mesenteric congestion | Increased caliber and visibility of mesenteric vessels |

| Stranding | Increased density of mesenteric fat |

| Enlarged lymph nodes | Increased number, size, or morphically abnormal mesenteric lymph nodes |

Figure 1.

Illustration of computed tomography findings of bowel inflammation—A, normal; B, mesenteric stranding; C, mesenteric congestion; D, bowel-wall thickening; E, ascites; and F, lymphadenopathy.

The patients were then analyzed depending on whether they developed abdominal symptoms during the course of treatment. The Mann-Whitney test was performed to determine whether there was a significant association between a positive score and positive abdominal symptoms. This was performed at 3 time points: at baseline, at symptom onset, and at the time of the most recent scan.

Mucosal biopsies were performed in 4 of the patients in this cohort who underwent endoscopic examination because of ongoing symptoms. These biopsies were independently reviewed by an anatomical pathologist (A.G.) and relevant changes described.

Results

Demographic Details

A cohort of 22 consecutive patients treated with selpercatinib at a single center as part of LIBRETTO-001 is presented with available radiographical and histopathological data. The information is presented in Table 2. The median age at screening was 52 years (range, 18-77 years) with a majority (65%, n = 13) identifying as male. Most patients were receiving treatment for management of progressive metastatic MTC (90%, n = 18); of the others, one patient had metastatic DTC and another had metastatic pheochromocytoma. The most common molecular alteration in this cohort was somatic RET p.Met918Thr (n = 14). The remainder harbored RET-fusion alterations (papillary thyroid carcinoma n = 1), and mutations in exon 11 (C634 and C530 n = 3). Two of the patients harbored germline mutations (including the patient with metastatic pheochromocytoma), and the remainder harbored somatic mutations. All 20 patients remain on trial drug at the time of publication. Eleven (55%) required dose adjustments because of AEs, 8 (40%) because of GI AEs, and 1 each because of allergic reaction, long QTc, and hepatitis. Three patients have progressive disease (15%) but remain on selpercatinib. One stabilized once the dose was decreased. The demographic details and diagnoses are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographics of 20 patients prescribed selpercatinib

| Baseline characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (n = 20) | Symptoms (n = 10) | No symptoms (n = 10) | |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 13 (65) | 6 (60) | 7 (70) |

| Female | 7 (35) | 4 (40) | 3 (30) |

| Age, median (range), y | 51.5 (18-77) | 51 (41-70) | 58 (18-77) |

| Follow-up, median (range), wk | 118 (62-175) | 129 (68-175) | 101 (62-153) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Medullary thyroid carcinoma | 18 (90) | 9 (90) | 9 (90) |

| Papillary thyroid carcinoma | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) |

| Pheochromocytoma | 1 (5) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Mutation, n (%) | |||

| Germline | 2 (10) | 2 (20) | 0 (0) |

| Somatic | 18 (90) | 8 (80) | 10 (100) |

| Exon 16 M918T | 14 (70) | 7 (70) | 7 (70) |

| RET fusion | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) |

| Exon 11 | 3 (15) | 1 (10) | 2 (20) |

| Presentation of GI AE | |||

| After first dose; median (range), d | 42 (7-380) | 41 (7-336) | N/A |

| Gastrointestinal AEs, n (%) | |||

| Bowel habit changes | 8 (40) | 8 (40) | N/A |

| Abdominal swelling | 7 (35) | 7 (35) | N/A |

| Abdominal discomfort | 7 (35) | 7 (35) | N/A |

| Anorexia | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | N/A |

| Weight gain | 6 (30) | 6 (30) | N/A |

| Nausea | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | N/A |

| Recurrent symptoms | 5 (25) | 5 (25) | N/A |

| Dose changes, n (%) | |||

| Dose reduction | 11 (55) | 8 (80) | 3 (30) |

| Dose reduction due to GI AE | 8 (40) | 8 (80) | 0 (0) |

| Discontinuation | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| Outcome, n (%) | |||

| Stable disease | 17(85) | ||

| Progressive disease | 3 (15) | ||

Abbreviations: AE, adverse effect; GI, gastrointestinal; MTC, medullary thyroid carcinoma; N/A, not available; RET, rearranged during transfection.

Clinical Features of Gastrointestinal Adverse Effects of Selpercatinib

Of 22 patients in this cohort, 10 (50%) developed gastrointestinal adverse effects. These presented at a median of 41 days from the first dose of selpercatinib (interquartile range, 15-91 days). The most common symptoms were changes in bowel habit (n = 8), followed by abdominal swelling (n = 7), abdominal discomfort (n = 7), and anorexia and nausea. Weight gain occurred in 6 patients. Eight patients required dose reduction as a result of gastrointestinal adverse effects, and one had a dose reduction because of prolonged QTc.

For the 10 patients who developed AEs, 10% (n = 1) had grade 1 (common terminology criteria for adverse effects, CTCAE), 70% (n = 7) had grade 1 to 2 CTCAE, and 20% (n = 2) grade 1 to 3 CTCAE adverse effects.

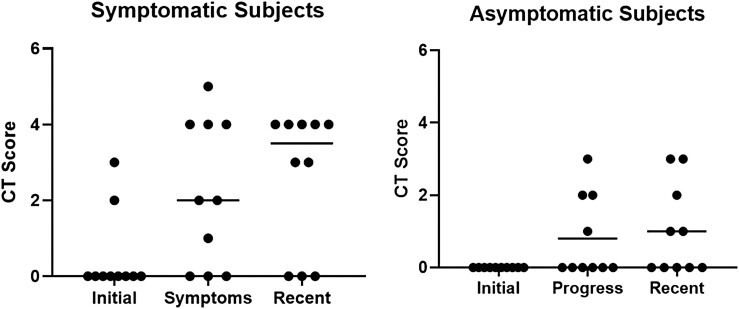

Radiological Scoring Correlated With Adverse Effects

A novel radiological scoring system, outlined in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1 (16), was performed for each patient at baseline, symptom onset, and at latest follow-up (median 60 weeks from first dose, range, 16-107 months; median 67 weeks from time of symptoms to most recent scan, range, 0-101 weeks). The results are shown in Fig. 2. Two patients had abdominal magnetic resonance imaging scans instead of CT and were excluded from this radiological assessment. At baseline, there was no difference in radiological score between patients who would later develop symptoms and those without. At the time of symptom onset, 7 of 10 patients with symptoms had a score greater than or equal to 1 (median 2, SEM 0.61), whereas in a similar time frame, 4 of the 10 asymptomatic patients had a score greater than or equal to 1 (median 0, SEM 0.36) (P = .093). On the most recent available follow-up scan, 7 of 10 symptomatic patients had a score greater than or equal to 1(median 3.5, SEM 0.58), whereas 5 of 10 asymptomatic patients had a score greater than or equal to 1 (median 0.5, SEM 0.39) (P = .049).

Figure 2.

Computed tomography (CT) scoring. Fig. 2 shows the initial, progress, and recent combined CT scoring for each of the bowel edema patients who were (left panel) symptomatic and (right panel) asymptomatic after commencement of selpercatinib. The median is shown for each group. There was a trend toward a difference in the progress score (P = .093) whereas the most recent score was significantly different between the symptomatic and asymptomatic groups (P = .0049).

In the initial scan, abnormalities included enlarged lymph nodes (n = 2); stranding (n = 1) and mesenteric congestion (n = 1). In the progress scan, the most common abnormal feature was bowel-wall thickening (n = 8, symptomatic = 5 and asymptomatic = 3), followed by mesenteric congestion (n = 7, symptomatic = 5, asymptomatic = 2), and ascitic fluid (n = 6, symptomatic = 5, asymptomatic = 1). In the most recent scan, the most common features were again bowel wall thickening (n = 10, symptomatic = 7 and asymptomatic = 3), ascitic fluid (n = 10, symptomatic = 7 and asymptomatic = 3), and mesenteric congestion (n = 8, symptomatic = 7 and asymptomatic = 1). Enlarged lymph nodes were present in only one asymptomatic patient and one of the symptomatic patients.

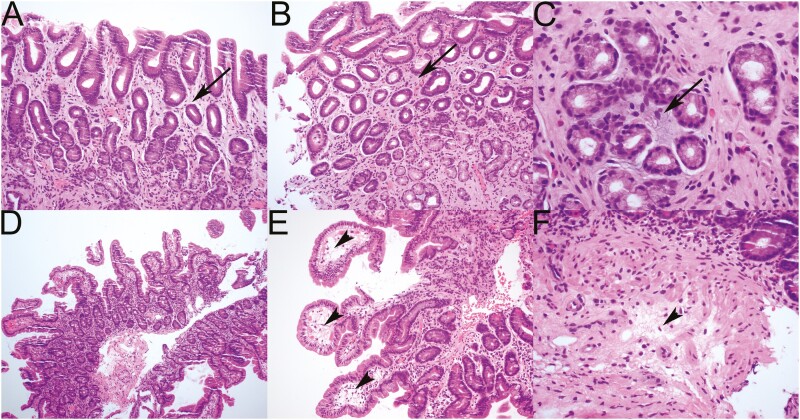

Histological Examination

Initial examination of the biopsies from 5 symptomatic patients were varied. Two symptomatic patients were considered morphologically normal, whereas 2 were reported as showing mild, nonspecific mucosal edema. Unblinded pathological review showed 3 cases with subtle mucosal edema characterized by myxoid change in the lamina propria of the stomach (Fig. 3A-3C), and subtle mucosal edema characterized by myxoid change in the lamina propria (see Fig. 3A-3C), with a little accumulation of edema fluid in the tips of the duodenal villi and submucosa (Fig. 3E and 3F). There was no histologic evidence of mucosal inflammation and no increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes.

Figure 3.

Pathological examination of endoscopic biopsies from A, B, and C, the stomach, and D, E, and F, the duodenum commonly showed only very subtle mucosal edema that was commonly overlooked. Mucosal edema is evident histologically as either a subtle pale blue hue in A, B, and C, the lamina propria (arrows), or stromal clearing with a somewhat vacuolated appearance in D, the tips of the villi (arrowhead) or E, submucosa (arrowhead).

Discussion

The development of selpercatinib for treatment of RET-altered cancers has changed the paradigm of advanced thyroid cancer management. While early trials have shown a reduction in tumor size for nearly all patients, the low frequency of severe AEs have propelled these more selective inhibitors into the forefront of treatment for metastatic disease. It is important to characterize novel AEs as this drug becomes more widely used. Here we have developed a novel radiological grading system that correlated with GI symptoms in our patients and confirm a characteristic mucosal oedema on histology. In many MKI trials and in clinical practice, AEs are a limiting factor in deciding whether to start TKIs (17). The benefit of the more selective inhibitors including selpercatinib and pralsetinib, another RET kinase inhibitor, is minimization of off-target effects. Novel AEs that lead to treatment interruptions need to be fully characterized to optimize utility of these agents in real-world clinical practice.

In our cohort of 20 patients, half developed GI AEs and 4 patients had gastric and small-bowel biopsies confirming mucosal edema. To our knowledge, this has not been previously reported for this drug class. We have no reason to assume our cohort was not otherwise representative of the LIBRETTO-001 trial. Radiological assessment showed that CT changes correlate with onset of symptoms and may predict clinical deterioration. Recognized findings on CT in treatment-related enteritis/colitis include bowel-wall thickening, mesenteric vessel engorgement, serosal hyperemia, fluid-filled loops of bowel, and peritoneal free fluid (1, 2). Pneumatosis intestinalis is a less common finding that is not necessarily indicative of ischemia or infarction in the setting of system or targeted therapy (18). While these imaging features are indicative of bowel inflammation, the appearances that can be seen in chemotherapy and molecular therapy–induced enteritis are often nonspecific and indistinguishable from changes seen with infectious or inflammatory enteritis (18-20). An additional limitation of imaging assessment was the assumption that review of the CT scan completed either at the time of clinical symptoms, or immediately preceding symptoms, was an appropriate correlate. We developed the scoring system using 5 main features (bowel-wall thickening, mesenteric congestion, stranding, ascitic fluid, lymphadenopathy) but scoring was more predictive after removal of lymphadenopathy. While the proposed scoring system is not validated, the radiological feature of bowel inflammation, and the exclusion of lymphadenopathy as a dominant finding, is concordant with generally accepted features of bowel inflammation.

Another consideration is the possibility of lag time between radiological and clinical improvement, which is common in other inflammatory and infective pathologies. This may account for the persisting abnormal scores on the follow-up imaging that was seen in many of the symptomatic patients. Also of note, 3 of 5 patients with recurrent symptoms had higher scores on follow-up imaging than at the onset of symptoms. Given the recurrent or prolonged symptoms in these patients, despite dose reduction, imaging features of persisting inflammation may relate to clinical flares.

One limitation of this study is the lack of outcome data for those on selpercatinib as this is part of a larger clinical study. It is well known that certain AEs can predict more of a tumoricidal effect, as in RAI-R disease tumors treated with lenvatinib who have hypertension or diarrhea have a greater inhibitory drug effect and a better clinical outcome (17). Further analysis once final outcome data are presented would be useful to ascertain if small-bowel obstruction was predictive in a similar fashion.

The histopathological features were subtle and easily overlooked, being characterized solely by very mild mucosal edema. It is unlikely that these features, present in only 3 of 4 patients, would be specific enough to allow a tissue diagnosis in the unblinded setting. Furthermore, there was no control group of biopsies from patients treated with selpercatinib who did not have GI tract symptoms. However, the identification of histological evidence of mucosal edema observed in conjunction with the radiological findings of congestion and wall thickening suggest that bowel-wall edema is the predominant mechanism of abdominal pain in these patients. Many (n = 8) of these patients had dose interruption or reduction and symptoms resolved. There were several (n = 5) who had recurrent episodes, and it was those in whom the biopsy was taken. Future studies with larger numbers of patients should characterize susceptibility factors to this AE.

Expression of RET receptor multikinase is consistently found within enteric neurons in the gut (21). Inactivating RET mutations lead to Hirschprung disease, in which an absence of gut innervation together with GI symptoms is prevalent. Whether targeted inhibition of RET with selpercatinib affects enteric neurons is speculative but may be relevant to fully comprehend the mechanism behind these symptoms.

Ultimately selpercatinib is a generally well-tolerated drug compared to other MKIs. We note small-bowel edema can present in some patients on this treatment with abdominal pain and bloating that typically resolves with dose interruption and/or reduction. Further observation in postmarketing studies will be needed to determine the prevalence of this AE.

Acknowledgments

This study has approval from the Northern Sydney Local Health district human research and ethics committee.

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of the sponsors of the trial from Eli Lilly as well as the patients who participated in this trial.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AE

adverse effect

- CT

computed tomography

- CTCAE

common terminology criteria for adverse effects

- DTC

differentiated thyroid carcinoma

- GI

gastrointestinal

- MEN2

multiple endocrine neoplasia 2 syndrome

- MKI

multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor

- MTC

medullary thyroid carcinoma

- RAI-R

radioactive iodine–refractory

- RET

rearranged during transfection

- TKI

tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Contributor Information

Venessa Tsang, Department of Endocrinology, Royal North Shore Hospital, NSW 2065, Sydney, Australia; Northern Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia.

Anthony Gill, Northern Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia; NSW Health Pathology Department of Anatomical Pathology, Royal North Shore Hospital, NSW 2065, Sydney, Australia.

Matti Gild, Department of Endocrinology, Royal North Shore Hospital, NSW 2065, Sydney, Australia; Northern Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia.

Brett Lurie, Department of Radiology, Royal North Shore Hospital, NSW 2065, Sydney, Australia.

Lucy Blumer, Department of Radiology, Royal North Shore Hospital, NSW 2065, Sydney, Australia.

Rhonda Siddall, Department of Endocrinology, Royal North Shore Hospital, NSW 2065, Sydney, Australia.

Roderick Clifton-Bligh, Department of Endocrinology, Royal North Shore Hospital, NSW 2065, Sydney, Australia; Northern Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia.

Bruce Robinson, Department of Endocrinology, Royal North Shore Hospital, NSW 2065, Sydney, Australia; Northern Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia.

Author Contributions

V.T. and L.B. prepared the draft of the manuscript, which was reviewed and approved by all authors. B.L. and L.B. performed independently the analysis of radiology. A.G. reviewed the histopathology.

Disclosures

V.T. has received honoraria from Eisai. R.C.B., unrelated to this work, has served on advisory boards for AMGEN, Eisai, Kyowa Kirin, and received honoraria from AMGEN and Eisai. B.R. is an advisor to Eisai, Exelixis, and Lilly, and an investigator for Lilly and Exelixis. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

Original data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article or available via the online database at doi:10.5281/zenodo.6578846.

References

- 1. Durante C, Haddy N, Baudin E, et al. Long-term outcome of 444 patients with distant metastases from papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma: benefits and limits of radioiodine therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(8):2892-2899. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kloos RT, Eng C, Evans DB, et al. ; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force. Medullary thyroid cancer: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association. Thyroid. 2009;19(6):565-612. doi: 10.1089/thy.2008.0403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Santoro M, Carlomagno F. Drug insight: small-molecule inhibitors of protein kinases in the treatment of thyroid cancer. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2006;2(1):42-52. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marsh DJ, Learoyd DL, Robinson BG. Medullary thyroid carcinoma: recent advances and management update. Thyroid. 1995;5(5):407-424. doi: 10.1089/thy.1995.5.407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Groot JWB, Links TP, Plukker JTM, Lips CJM, Hofstra RMW. RET as a diagnostic and therapeutic target in sporadic and hereditary endocrine tumors. Endocr Rev. 2006;27(5):535-560. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nikiforov YE, Rowland JM, Bove KE, Monforte-Munoz H, Fagin JA. Distinct pattern of ret oncogene rearrangements in morphological variants of radiation-induced and sporadic thyroid papillary carcinomas in children. Cancer Res. 1997;57(9):1690-1694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ciampi R, Giordano TJ, Wikenheiser-Brokamp K, Koenig RJ, Nikiforov YE. HOOK3-RET: a novel type of RET/PTC rearrangement in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2007;14(2):445-452. doi: 10.1677/ERC-07-0039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vanden Borre P, Schrock AB, Anderson PM, et al. Pediatric, adolescent, and young adult thyroid carcinoma harbors frequent and diverse targetable genomic alterations, including kinase fusions. Oncologist. 2017;22(3):255-263. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Su X, Li Z, He C, Chen W, Fu X, Yang A. Radiation exposure, young age, and female gender are associated with high prevalence of RET/PTC1 and RET/PTC3 in papillary thyroid cancer: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7(13):16716-16730. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wells SA Jr, Robinson BG, Gagel RF, et al. Vandetanib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic medullary thyroid cancer: a randomized, double-blind phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(2):134-141. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.5040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Elisei R, Schlumberger MJ, Müller SP, et al. Cabozantinib in progressive medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(29):3639-3646. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.4659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brose MS, Nutting CM, Jarzab B, et al. DECISION Investigators. Sorafenib in radioactive iodine-refractory, locally advanced or metastatic differentiated thyroid cancer: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9940):319-328. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60421-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schlumberger M, Tahara M, Wirth LJ, et al. Lenvatinib versus placebo in radioiodine-refractory thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(7):621-630. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wirth LJ, Sherman E, Robinson B, et al. Efficacy of selpercatinib in RET-altered thyroid cancers. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(9):825-835. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2005651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Drilon A, Oxnard GR, Tan DSW, et al. Efficacy of selpercatinib in RET fusion-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(9):813-824. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2005653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tsang VG, Gill A, Gild M, et al. Supplementary data for “ Selpercatinib treatment of RET mutated thyroid cancers is associated with gastrointestinal adverse effects.” 2022. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.6578846. https://zenodo.org/record/6578846/export/hx#.YqqtjuhByUk. Upload May 25, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17. Gild ML, Tsang VHM, Clifton-Bligh RJ, Robinson BG. Multikinase inhibitors in thyroid cancer: timing of targeted therapy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021;17(4):225-234. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-00465-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sugi MD, Menias CO, Lubner MG, et al. CT findings of acute small-bowel entities. Radiographics. 2018;38(5):1352-1369. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018170148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Keraliya AR, Rosenthal MH, Krajewski KM, et al. Imaging of fluid in cancer patients treated with systemic therapy: chemotherapy, molecular targeted therapy, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205(4):709-719. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.14459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thornton E, Howard SA, Jagannathan J, et al. Imaging features of bowel toxicities in the setting of molecular targeted therapies in cancer patients. Br J Radiol. 2012;85(1018):1420-1426. doi: 10.1259/bjr/19815818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Perea D, Guiu J, Hudry B, et al. Ret receptor tyrosine kinase sustains proliferation and tissue maturation in intestinal epithelia. EMBO J. 2017;36(20):3029-3045. doi: 10.15252/embj.201696247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Original data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article or available via the online database at doi:10.5281/zenodo.6578846.