Abstract

Context

A greater decrease in 24-hour energy expenditure (24hEE) during short-term fasting is indicative of a thrifty phenotype.

Objective

As ghrelin and the growth hormone (GH)/insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) axis are implicated in the regulation of energy intake and metabolism, we investigated whether ghrelin, GH, and IGF-1 concentrations mediate the fasting-induced decrease in 24hEE that characterizes thriftiness.

Methods

In 47 healthy individuals, 24hEE was measured in a whole-room indirect calorimeter both during 24-hour eucaloric and fasting conditions. Plasma total ghrelin, GH, and IGF-1 concentrations were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay after an overnight fast the morning before and after each 24-hour session.

Results

During 24-hour fasting, on average 24hEE decreased by 8.0% (P < .001), GH increased by ~5-fold (P < .001), whereas ghrelin (mean +23 pg/mL) and IGF-1 were unchanged (both P ≥ .19) despite a large interindividual variability in ghrelin change (SD 150 pg/mL). Greater fasting-induced increase in ghrelin was associated with a greater decrease in 24hEE during 24-hour fasting (r = –0.42, P = .003), such that individuals who increased ghrelin by 200 pg/mL showed an average decrease in 24hEE by 55 kcal/day.

Conclusion

Short-term fasting induced selective changes in the ghrelin/GH/IGF-1 axis, specifically a ghrelin-independent GH hypersecretion that did not translate into increased IGF-1 concentrations. Greater increase in ghrelin after 24-hour fasting was associated with greater decrease in 24hEE, indicating ghrelin as a novel biomarker of increased energy efficiency of the thrifty phenotype.

Keywords: thrifty phenotype, ghrelin, growth hormone, energy expenditure, fasting

Fasting induces a decrease in 24-hour energy expenditure (24hEE) that is highly variable among individuals (1), ranging from −1% to −20% of 24hEE measured during eucaloric conditions, and is predominantly due to the lack of thermogenic response to feeding (2). We have previously shown that a greater decrease in 24hEE during 24-hour fasting is indicative of a thrifty phenotype (2) susceptible to overfeeding-induced weight gain (3) and resistant to diet-induced weight loss (4). The greater fasting-induced decrease in 24hEE is associated with a blunted increase in urinary epinephrine and a greater decrease in plasma leptin, qualifying both hormones as markers of thriftiness (5, 6). However, these hormones together only explain a small proportion (R2 ~10%) of the large interindividual variability in 24hEE observed during 24-hour fasting (5). Therefore, additional hormones might be implicated in the adaptive regulation of 24hEE during short-term fasting and may further characterize the thrifty phenotype.

In this study, we investigated the association of the fasting-induced effects of the growth hormone (GH)/insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) axis on the extent of decrease in 24hEE during fasting conditions. GH is an important regulator of human growth and development (7) and has been positively associated with increased energy expenditure (EE) in many clinical studies (8-11). GH is released in a pulsatile fashion by the anterior pituitary gland and mediates most of its anabolic effects by stimulating continuous hepatic release of IGF-1 (7). GH substantially increases during short-term fasting (12-15) and may, therefore, constitute a plausible mediator of fasting-induced changes in 24hEE. In contrast, IGF-1 tends to decrease during fasting (14) and does not appear to have a major role in the regulation of EE (16).

GH secretion is mainly controlled by the hypothalamic hormones, GH-releasing hormone (stimulatory) and somatostatin (inhibitory), as well as by IGF-1 via a negative feedback loop (7). Additionally, GH secretion can be stimulated by the stomach-derived orexigenic hormone ghrelin (17), which links the GH/IGF-1 axis to meal consumption as ghrelin has a very consistent diurnal secretion pattern that strongly depends on food ingestion with a sharp increase before meal initiation followed by a drop in the postprandial state (18). Dietary perturbations such as short-term fasting might therefore modulate the downstream activity of the GH/IGF-1 axis via upstream effects on ghrelin secretion. As higher ghrelin concentrations are associated with lower metabolic rate (19-22), ghrelin may be implicated in the regulation of EE during fasting conditions independently from its effect on GH secretion.

In this present study, we aimed to assess whether 24-hour fasting alters the plasma concentrations of total ghrelin, GH, total IGF-1, and IGF-binding protein 3 (IGFPB-3) (additionally measured as the main binding protein of IGF-1) and whether the fasting-induced hormonal changes are associated with concomitant adaptive changes in 24hEE and substrate oxidation during prolonged fasting conditions that characterize the extent of metabolic thriftiness.

Materials and Methods

Volunteers and Study Design

The analysis was performed using data from a clinical trial (clinicaltrial.gov identifier: NCT00523627) aimed to investigate the short-term EE responses to 24-hour fasting and overfeeding conditions. From 2008 to 2015, a total of 47 individuals aged 19-54 years completed the study and had plasma measurements of total ghrelin, GH, total IGF-1, and IGFBP-3 concentrations during both 24-hour eucaloric and fasting conditions (Suppl. Figure 1 (23)). All participants signed a written informed consent prior to admission. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases at the National Institutes of Health.

Study volunteers were weight stable (less than 5% variation in body weight) for at least 6 months before admission and were free from medical diseases based on medical history, physical examination, and fasting blood tests. Upon admission to the clinical research unit, individuals were fed daily a weight-maintaining diet (WMD; 50% carbohydrate, 30% fat, and 20% protein), with total intake calculated using unit-specific equations based on gender and weight (24). Body weight was recorded daily and was maintained within 1% of the admission weight by adjusting the energy intake of the WMD by ±200 kcal/day if needed (25). The WMD was consumed on all days except when 24hEE was measured inside the whole-room calorimeter. On the second day of admission, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DPX-1, Lunar Corp, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) was used to assess body composition with fat mass and fat-free mass calculated from the percentage body fat (PFAT) from the dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scan. An oral glucose tolerance test was performed after 3 days of WMD and only subjects with normal glucose regulation continued the study (26). Plasma glucose concentrations were measured using the Analox GM9 glucose oxidase method (Analox Inst. USA Inc., Lunenburg, MA, USA). Plasma insulin concentrations were measured using an automated immunoenzymometric assay (Tosoh Bioscience Inc., Tessenderlo, Belgium).

Energy Expenditure Measurements

The assessment of 24hEE and respiratory quotient (RQ, an index of substrate oxidation) inside the whole-room indirect calorimeter was performed as previously described (1, 27-29). Briefly, after an overnight fast and following breakfast (7:00 am) subjects entered the calorimeter around 7:30 am. During each dietary intervention except for 24-hour fasting, meals were provided to the subjects through an airtight interlock at 11:00 am, 4:00 pm, and 7:00 pm, and any uneaten food was weighed by the metabolic kitchen staff to determine the actual 24-hour energy intake consumed during each 24-hour session. The air temperature was maintained constant at 23.8 ± 1.4°C. The air inflow rate was controlled by a mass flow controller (Alicat, MCRW-250SLPM-D-I) at a fixed rate of 60 L/minute. Samples of air were dried by gas sample dryers (Perma Pure LLC, PD-50T-48MSS) driven by counterflowing dry air generated by an air compressor (JUN-AIR). Air samples were analyzed by differential CO2 (ABB Automation, Uras 26) and O2 (Siemens Oxymat 6E) analyzers at a flow rate of 0.7 L/minute controlled by mass flow controllers (Alicat, Basis). Volunteers remained in the calorimeter for 23.5 hours, during which CO2 production and O2 consumption were recorded every minute and the 24hEE was calculated using the Lusk formula (28). Subjects’ spontaneous physical activity was measured by radar sensors and expressed as the percentage of time when activity was detected (30). The daytime EE in the inactive, awake state (EE0) was calculated as the intercept of the regression line between EE and spontaneous physical activity at 1-minute data points between 10:00 am and 1:00 am and extrapolated to 15 hours (31). Sleeping EE (SLEEP) was calculated as the average EE between 11:30 pm and 5:00 am overnight when subject movement was less than 1.5% (<0.9 seconds/minute) and extrapolated to a 24-hour period, as previously described (1). The awake and fed thermogenesis was calculated as the difference between EE0 minus SLEEP (kcal/minute) and extrapolated to 15 hours (31). The 24-hour RQ was calculated as the ratio of the average 24-hour CO2 production to the average 24-hour O2 consumption. Carbohydrate oxidation (CARBOX) and lipid oxidation (LIPOX) rates were derived from the 24-hour RQ after accounting for protein oxidation (PROTOX), which was estimated from measurement of 24-hour urinary nitrogen excretion (32).

Dietary Interventions

The experimental protocol and dietary manipulations were previously described in detail (1). Briefly, 2 24hEE measurements were performed to precisely achieve an energy balance state inside the calorimeter. During the first 24-hour session, the WMD was reduced by 20% to account for reduced activity inside the calorimeter; subsequently, the second 24-hour session was performed 2 days later when the energy intake was set to the 24hEE value from the first assessment. The 24hEE value from the second session was considered the baseline (eucaloric) EE. Following the energy balance assessment and after at least 3 days on the WMD, 24hEE was assessed during 24-hour fasting when no food was provided, and subjects were instructed to keep themselves hydrated by drinking water or no-calorie no-caffeine beverages.

Hormone Measurements

Blood for measurements of total ghrelin, GH, and IGF-1 concentrations was collected in the morning after overnight fasting both prior to exit and upon exit from the calorimeter during each dietary intervention. The samples were collected in EDTA-containing tubes and stored in a freezer at ‒70°C, and subsequently shipped to the NIDDK Core laboratory in Bethesda, MD, for hormonal measurements. Total ghrelin was measured using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit from EMD-Millipore (RRID:AB_2892838, Billerica, MA, USA); intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variation (CV) were 3.8% and 10.3%, respectively. GH was measured using the Human magnetic beads Luminex screening assay from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA); intra-assay and interassay CVs were 5.9% and 7.3%, respectively. Total IGF-1 (RRID:AB_2915952) and IGFBP-3 (RRID:AB_2915951) were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA); intra-/interassay CVs were 2.3/6.1% and 1.5/3.1%, respectively. Plasma insulin concentrations were measured by an automated immunoenzymometric assay (RRID:AB_2915954, Tosoh Bioscience Inc., Tessenderlo, Belgium). Plasma glucose concentrations were determined using an enzymatic oxygen rate method.

Statistical Analysis

The primary aim of this study was to assess the relationships between fasting-induced changes in total ghrelin, GH, and IGF-1 and concomitant changes in 24hEE during acute fasting. These analyses were prespecified and supported by previous studies showing that ghrelin, GH, and IGF-1 are interrelated (7, 17) and that ghrelin and GH have an effect on metabolic rate (8-11, 19-22). As such, no correction was made for multiple tests as all analyses were preplanned and exploratory, and hormonal data were correlated (33).

Unless otherwise stated, data are presented as mean ± SD or with 95% CI as indicated. For each hormone, the CV and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) were calculated considering both fasting measurements obtained prior to entering the calorimeter during energy balance and fasting conditions to assess within-subject stability and reproducibility of baseline hormonal concentrations. Both hormone concentrations measured before entering the calorimeter were averaged within each subject and considered as the baseline values. Fasting GH concentrations were log10-transformed before analyses to meet the assumptions of parametric tests (ie, homoscedasticity and Gaussian distribution) and results were expressed as geometric mean with 95% CI. Student’s unpaired t-test and analysis of variance with the post hoc Tukey test were used to assess interindividual differences in baseline hormonal values according to sex and race/ethnicity, respectively. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was used to quantify associations between continuous variables. Multivariate regression analyses were conducted to identify the determinants of baseline hormonal concentrations including age, sex, race/ethnicity, and PFAT as independent variables. The homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance was calculated by multiplying fasting glucose (mg/dL) with fasting insulin (mU/L) and then dividing by 405.

The individual change (Δ) in hormone concentrations was calculated as the difference between the postdiet minus the prediet values and analyzed using Student’s paired t-test. The individual change (Δ) in EE measurements from energy balance during 24-hour fasting was calculated as the EE value during fasting minus the EE value during energy balance. Sensitivity analyses were performed by adjusting EE measures for known determinants such as body composition via multivariate linear regression analysis. For graphical purposes and ease of interpretation, the aforementioned analyses using continuous EE data were followed up with confirmatory analyses using distinct metabolic groups. In these confirmatory analyses, subjects were arbitrarily classified as thrifty/spendthrift based on a lower/higher than median decrease in 24hEE during 24-hour fasting from energy balance conditions, respectively, as done previously (4, 34).

Data and Resource Availability

The data sets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the study group are shown in Table 1. Fasting total ghrelin, GH, and IGFBP-3 concentrations were not affected by plasma storage time (all P ≥ .06) while there was a moderate storage time effect for total IGF-1 (r = 0.39, P = .008) (Suppl. Figure 2 (23)), which was accounted for in the analyses. The CVs and ICCs of baseline (prediet) hormone concentrations were 11.2%, 9.8%, 7.3%, and 7.8%, and 0.93, 0.60, 0.93, and 0.76 for total ghrelin, GH, total IGF-1, and IGFBP-3, respectively, indicating good precision and within-subject consistency of fasting hormone measurements.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study group

| TOTAL n = 47 | THRIFTY n = 23 | SPENDTHRIFT n = 24 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 38 (80.9) | 20 (87.0) | 18 (75.0) |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| African-American | 11 (23.4) | 5 (21.7) | 6 (25.0) |

| White | 13 (27.7) | 7 (30.4) | 6 (25.0) |

| Native American | 19 (40.4) | 9 (39.1) | 10 (41.7) |

| Hispanic | 4 (8.5) | 2 (8.7) | 2 (8.3) |

| Age (years) | 37.3 ± 9.4 (19, 54) | 38.6 ± 8.5 (19, 51) | 36.1 ± 10.2 (20, 54) |

| Body composition measures | |||

| Body weight (kg) | 79.6 ± 12.1 (47.5, 107.8) | 83.4 ± 11.3* (56.4, 107.8) | 76 ± 11.9* (47.5, 104.8) |

| Height (cm) | 173.9 ± 7 (161.5, 196.4) | 173.5 ± 6 (164.9, 185) | 174.2 ± 8 (161.5, 196.4) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.4 ± 4.1 (17.8, 39.1) | 27.8 ± 4.2* (20.7, 39.1) | 25 ± 3.6* (17.8, 34.4) |

| Body fat (%) | 28.3 ± 9.7 (6.9, 53.8) | 29.6 ± 8.5 (6.9, 52.8) | 27 ± 10.7 (11.6, 53.8) |

| Fat mass (kg) | 22.9 ± 10.2 (5.9, 56.9) | 25 ± 9.8 (5.9, 56.9) | 20.9 ± 10.3 (7.3, 52.8) |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | 56.7 ± 9.4 (33.9, 79.4) | 58.4 ± 8.4 (42, 79.4) | 55.1 ± 10.2 (33.9, 77) |

| Energy expenditure measures during energy balance | |||

| 24hEE (kcal/day) | 2047 ± 291 (1507, 2810) | 2186 ± 195* (1731, 2646) | 1914 ± 309* (1507, 2810) |

| 24h energy intake (kcal/day) | 2063 ± 285(1529, 2921) | 2186 ± 201*(1679, 2501) | 1945 ± 307*(1529, 2921) |

| 24-hour energy balance (%) | 0.9 ± 3.7 (−7.3, 10.3) | 0.1 ± 4.1 (−7.3, 10.3) | 1.8 ± 3.2 (−3.8, 8.1) |

| 24-hour RQ (ratio) | 0.87 ± 0.04 (0.76, 1.02) | 0.87 ± 0.05 (0.76, 1.02) | 0.88 ± 0.03 (0.8, 0.93) |

| Energy expenditure measures during 24-hour fasting | |||

| 24hEE (kcal/day) | 1878 ± 246 (1426, 2655) | 1937 ± 173 (1524, 2290) | 1821 ± 293 (1426, 2655) |

| Decrease in 24hEE from energy balance conditions (kcal/day) | −169 ± 97 (−420, 0) | −248 ± 63* (−420, −166) | −93 ± 53* (−165, 0) |

| 24-hour RQ (ratio) | 0.79 ± 0.03 (0.73, 0.90) | 0.79 ± 0.03 (0.75, 0.90) | 0.79 ± 0.03 (0.73, 0.88) |

| Baseline hormone concentrationsb | |||

| Total ghrelin (pg/mL) | 586.9 ± 260.3 (173.8, 1262.6) | 534.2 ± 188.4 (173.8, 1013.7) | 637.3 ± 310.0 (248.1, 1262.6) |

| Growth hormonea (pg/mL) | 169.9 ± 191.4 (17.8, 757.4) | 166.0 ± 191.6 (17.8, 726.6) | 173.6 ± 195.1 (24.3, 757.4) |

| IGF-1 (ng/mL) | 86.8 ± 29.5 (31.4, 161.8) | 89.0 ± 27.7 (52.1, 154.8) | 84.7 ± 31.5 (31.4, 161.8) |

| IGFBP-3 (μg/mL) | 1.82 ± 0.37 (0.93, 2.45) | 1.81 ± 0.38 (0.93, 2.43) | 1.83 ± 0.37 (1.07, 2.45) |

| Changes in hormone concentrations following 24h fasting | |||

| Total ghrelin (pg/mL) | +23.3 ± 149.2(−452.4, 307.6) | +83.1 ± 118.7*(−173.4, 307.6) | −34.0 ± 155.1*(−452.4, 202.4) |

| Growth hormone (pg/mL) | +1664 ± 5581(−113, 37437) | +1022 ± 1474(−113, 4857) | +2253 ± 7629(−30, 37437) |

| IGF-1 (ng/mL) | −1.73 ± 8.75(−25.6, 25.8) | −2.27 ± 6.50(−10.5, 15.3) | −1.23 ± 10.51(−25.6, 25.8) |

| IGFBP-3 (μg/mL) | +0.09 ± 0.19(−0.35, 0.56) | +0.07 ± 0.20(−0.35, 0.42) | +0.10 ± 0.18(−0.16, 0.56) |

| Measures of glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity | |||

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 92.1 ± 4.9 (80, 100) | 93 ± 5.5 (80, 100) | 91.1 ± 4 (85.5, 99.5) |

| 2-hour glucose during OGTT (mg/dL) | 104.1 ± 22.5 (65, 154) | 96.6 ± 20.1* (65, 135) | 111 ± 22.8* (71, 154) |

| Fasting insulin (μIU/mL)a | 6.1 ± 1.7 (2, 19) | 6.9 ± 1.7 (2, 19) | 5.4 ± 1.7 (2, 17) |

| 2-hour insulin during OGTT (μIU/mL)a | 35.5 ± 2.2 (4, 185) | 30.9 ± 2.4 (4, 92) | 41.1 ± 2 (14, 185) |

Unless otherwise indicated, data presented as mean ± SD (minimum, maximum).

Classification of subjects into spendthrift or thrifty metabolic group was based on the median value of the decrease in 24hEE from energy balance during fasting (−165 kcal/day), such that thrifty subjects were those with a greater-than-median decrease in 24hEE during fasting conditions. Significance between thrifty and spendthrift metabolic groups was determined by unpaired Student’s t-test for quantitative variables and by χ2 test for categorical variables.

Abbreviations: IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; IGFBP-3, IGF-binding protein 3; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

a Average values of growth hormone, fasting insulin, and 2-hour OGTT insulin concentrations are shown as geometric means.

b Baseline total ghrelin, growth hormone, total IGF-1, and IGFBP-3 concentrations were obtained by averaging fasting measurements obtained before 24-hour energy balance and 24-hour fasting conditions.

*P < .05 between thrifty and spendthrift groups as determined by Student’s unpaired t-test.

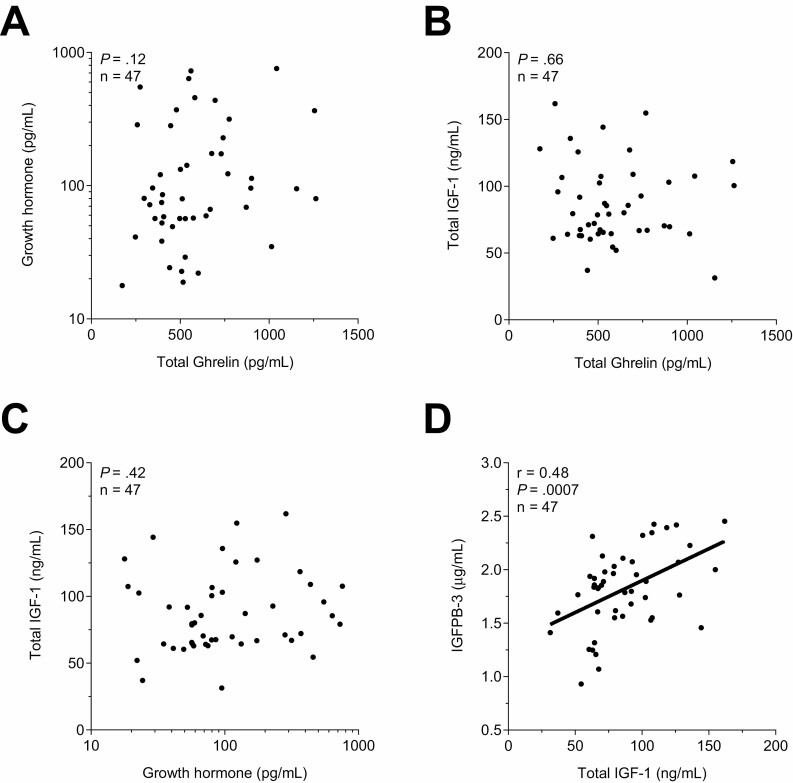

There were no associations among the baseline fasting concentrations of total ghrelin, GH, or IGF-1 (both P ≥ .12, Fig. 1A-1B) and between GH and IGF-1 (P = .42, Fig. 1C), while baseline IGF-1 was positively correlated with baseline IGFPB-3 (r = 0.48, P = .007, Fig. 1D). There were no associations between the baseline concentrations of any hormone and the adjusted EE measurements during energy balance (all P ≥ .16).

Figure 1.

Associations among baseline hormone concentrations. Associations between fasting total ghrelin and growth hormone (A) and IGF-1 (B). Associations between growth hormone and total IGF-1 (C), and between total IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 concentrations (D). Fasting plasma hormone concentrations measured before entering the calorimeter were averaged in each subject and used as baseline. Growth hormone concentrations axes are formatted on a logarithmic scale (log10) to account for skewed data distribution. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was used to quantify associations between continuous variables. IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; IGFBP-3, IGF-binding protein 3.

Determinants of Hormonal Concentrations

Fasting total ghrelin concentration was on average higher in females than in males (mean = +236 pg/mL, CI 53-419, P = .01; Suppl. Figure 3 (23)), in White people compared with Native Americans and Hispanics (both adj. P < .05; Suppl. Figure 4 (23)), and in Black people compared with Native Americans and Hispanics (both adj. P < .05). There were no associations between total ghrelin concentration and PFAT, body mass index (BMI), and age (all P ≥ 0.24; Figure 5 (23)). In a multivariate analysis, sex (females had a 177 pg/mL higher total ghrelin concentration than males, P = .04) and race/ethnicity (White people had a 391 and 347 pg/mL higher total ghrelin concentration than Hispanics and Native Americans, respectively, both P < .009), but not age, PFAT, or BMI (all P > .10) were independent determinants of fasting total ghrelin concentration (total R2 = 0.50; Table 2).

Table 2.

Determinants of total ghrelin, growth hormone, total IGF-1, and IGFBP-3 baseline concentrations

| Total ghrelin (pg/mL) | Growth hormone (pg/mL) (log10–transformed) | Total IGF–1 (ng/mL) | IGFBP–3(μg/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explained variance (global P value) | R 2 = 0.50 P < .0001 | R 2 = 0.44 P = .0005 | R2 = 0.23 P = .14 | R2 = 0.20 P = .16 |

| Age (years) | –0.68 ± 3.5(–7.74, 6.39); partial r: 0.03; P value: 0.85 | 0.01 ± 0.01 (–0.01, 0.02); partial r: 0.18; P value: 0.26 | –0.85 ± 0.5 (–1.86, 0.16); partial r: 0.26; P value: 0.10 | –0.01 ± 0.01 (–0.02, 0.01); partial r: 0.16; P value: 0.30 |

| Sex (male) | –227.19 ± 108.17(–445.8, –8.58); partial r: 0.32; P value: .04 | –0.82 ± 0.19 (–1.22, –0.43); partial r: 0.56; P value: .0001 | 11.74 ± 15.69 (–19.99, 43.48); partial r: 0.12; P value: .46 | –0.22 ± 0.19 (–0.61, 0.18); partial r: 0.17; P value: .27 |

| Ethnicity (Native American) | 43.84 ± 108.73 (–175.92, 263.59); partial r: 0.06; P value: .69 | 0.53 ± 0.2 (0.13, 0.92); partial r: 0.39; P value: .01 | 0.65 ± 15.97 (–31.65, 32.95); partial r: 0.01; P value: .97 | 0.04 ± 0.2(–0.35, 0.44); partial r: 0.03; P value: .83 |

| Ethnicity (White) | 390.87 ± 115.26 (157.92, 623.81); partial r: 0.47; P value: .002 | 0.46 ± 0.21 (0.04, 0.87); partial r: 0.33; P value: .03 | 19.61 ± 17.04 (–14.86, 54.07); partial r: 0.18; P value: .26 | 0.35 ± 0.21 (–0.07, 0.77); partial r: 0.26; P value: .10 |

| Ethnicity (Black) | 227.11 ± 121.95(–19.35, 473.57); partial r: 0.28; P value: .07 | 0.46 ± 0.22(0.02, 0.9); partial r: 0.31; P value: .04 | 16.1 ± 18 (–20.33, 52.47); partial r: 0.14; P value: .38 | 0.03 ± 0.22(–0.41, 0.47); partial r: 0.02; P value: .90 |

| Percentage body fat | –4.26 ± 4.88 (–14.13, 5.61); partial r: 0.14; P value: .39 | –0.02 ± 0.01(–0.04, 0); partial r: 0.37; P value: .02 | 0.32 ± 0.7 (–1.1, 1.73); partial r: 0.07; P value: .65 | –0.01 ± 0.01(–0.02, 0.01); partial r: 0.12; P value: .44 |

| Intercept | 723.36 ± 238.14 (242.06, 1204.65); P value: .004 | 2.52 ± 0.43 (1.65, 3.38); P value: <.0001 | 55.25 ± 40.92 (–27.52, 138.02); P value: .18 | 2.29 ± 0.43 (1.42, 3.15); P value: <.0001 |

Multivariate models for the determinants of overnight-fasted values of total ghrelin, growth hormone, total IGF-1, and IGFBP-3 (average of prechamber values). A multivariate analysis with body mass index instead of percentage body fat as covariate yielded similar results. Similar results were also obtained when additionally including storage time in the multivariate model with total IGF-1 as dependent variable. The β coefficient estimate in each cell is reported with ± SE and 95% CI in parentheses, along with partial correlations and P value. Significant results are highlighted in bold.

Abbreviations: IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; IGFBP-3, IGF-binding protein 3.

Fasting GH concentration was on average higher in females than in males (mean=+247 pg/mL, CI 123-371, P < .001; Suppl. Figure 3 (23)), and lower in Hispanics than in Black people (P < .05; Suppl. Figure 4 (23)) while being unrelated to BMI or age (all P ≥ 0.21; Suppl. Figure 5 (23)). In a multivariate analysis, sex (females had a 383 pg/mL higher GH concentration than males, P = .0001), race/ethnicity (Hispanics had a 50, 111, and 105 pg/mL lower GH concentration than White people, Black people, and Native Americans, respectively, all P < .05), and PFAT (leaner individuals had 2-fold higher GH concentrations per 10% difference in PFAT, P = .02) were independent determinants of fasting GH concentration (total R2 = 0.44, Table 2).

Fasting total IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 concentrations were not overall different between males and females (both P ≥ 0.22; Suppl. Figure 3 (23)) and among races/ethnicities (both P ≥ .10; Suppl. Figure 4 (23)). There were no associations between either hormone and PFAT, BMI, or age (all P ≥ .12; Suppl. Figure 5 (23)).

Hormonal Changes After 24-hour Fasting and Associations with Concomitant 24hEE Changes

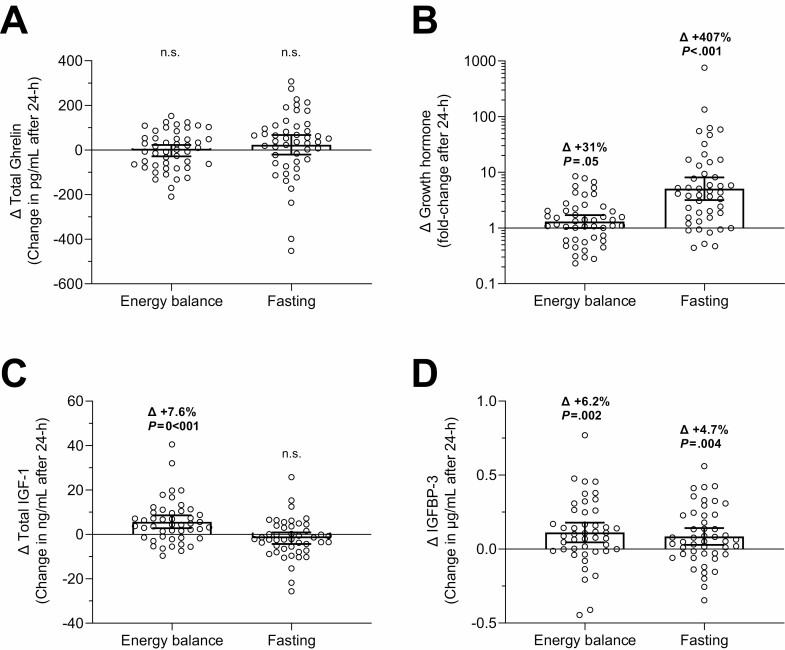

The changes in total ghrelin, GH, total IGF-1, and IGFPB-3 concentrations after 24-hour fasting are reported in Fig. 2 and elsewhere (Suppl. Figure 6, individual pre/post values (23); and Suppl. Table 1 average changes with CIs (23)).

Figure 2.

Changes in hormonal concentrations after 24-hour energy balance and fasting conditions. Changes in total ghrelin (A), growth hormone (B), total IGF-1 (C), and IGFPB-3 (D) after 24-hour energy balance and fasting conditions inside a whole-room indirect calorimeter. The individual change in hormone concentrations on the y-axis was calculated as the difference between the postdiet minus the prediet absolute concentrations. Growth hormone concentrations are shown on a logarithmic scale (log10) to account for skewed data distribution. Error bars represent mean ±95% CI. Average changes (∆) are expressed as percentage of prediet value and shown along with the P-value using the Student’s paired t-test. Statistically significant changes are highlighted in bold. IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; IGFBP-3, IGF-binding protein 3.

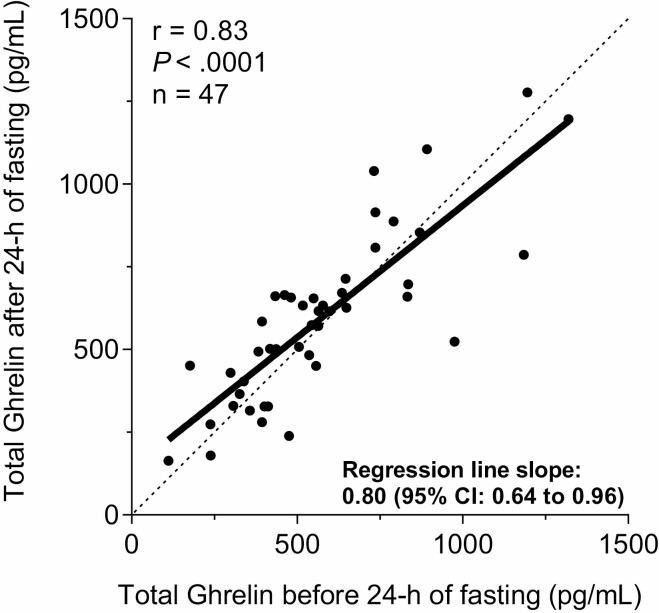

After 24-hour fasting, on average GH substantially increased by ~5-fold (CI 3.2-8.1, P < .001; Fig. 2B), IGFPB-3 increased by 5% (Δ=+0.09 µg/mL, CI 0.03-0.14, P = .004; Fig. 2D), while total ghrelin and IGF-1 remained overall unchanged (both P ≥ .19; Fig. 2A and 2C). The change in ghrelin concentration after 24-hour fasting was dependent on its baseline concentration (slope = 0.80; CI 0.64-0.96; P < .05); in other words, individuals with lower baseline ghrelin concentration showed a greater increase in total ghrelin after 24-hour of fasting (Fig. 3). There were no associations between Δghrelin and ΔGH (P = .93) and between ΔGH and ΔIGF-1 (P = .81) after 24-hour fasting, while ΔIGF-1 was positively related to ΔIGFPB-3 (r = 0.34, P = 0.02).

Figure 3.

Relationship between total ghrelin concentrations measured before and after 24-hour fasting. Relationship between plasma concentration of total ghrelin measured before (x axis) and after (y axis) 24-hour fasting inside the metabolic chamber. The dotted line indicates the line of identity where hormonal pre- and postfasting concentrations are equal. The slope of regression line (=0.80) was statistically less than 1 (95% CI 0.64-0.96, P < .05), indicating a proportional effect for the fasting-induced changes in total ghrelin, such that subjects with relatively lower total ghrelin concentration before 24-hour fasting showed a greater increase in total ghrelin after 24-hour fasting and, vice versa, subjects with relatively higher total ghrelin concentration before 24-hour fasting showed a greater decrease in total ghrelin after 24-hour fasting.

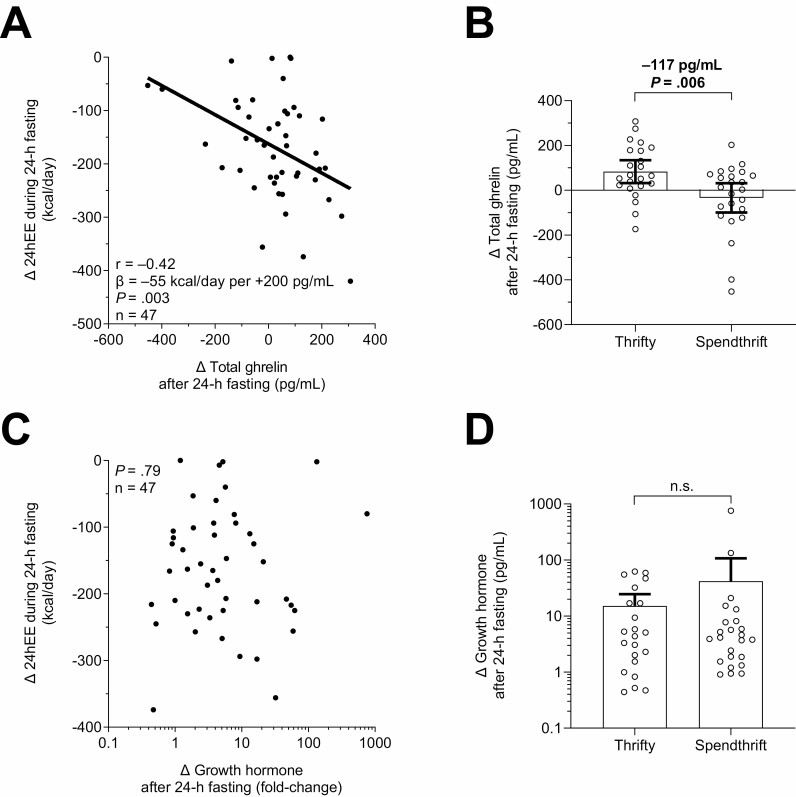

During 24-hour fasting and compared with eucaloric conditions, on average 24hEE decreased by 8.0% (CI –9.2 to –6.8, P < .001). A greater increase in total ghrelin following 24-hour fasting was associated with greater concomitant decrease in 24hEE (r=–0.42, P = .003; Fig. 4A), such that a greater fasting-induced increase in total ghrelin by 200 pg/mL was related to an average concomitant greater decrease in 24hEE by ~55 kcal/day (CI 19.0-90.2). Similar results were obtained in sensitivity analyses: (1) using the Spearman rank-based correlation (ρ=–0.34, P = .02) which is robust to outliers, (2) analyzing the percentage changes in 24hEE (r=–0.38, P = .009; Suppl. Figure 7A (23)), and (3) analyzing the changes in adjusted 24hEE (r=–0.29, P = .046; Suppl. Figure 7B (23)) during 24-hour fasting. For illustrative purposes and to confirm our results obtained using continuous 24hEE data, we also performed a group-wise comparison of thrifty vs spendthrift subjects as arbitrarily defined by the median decrease (−165 kcal/day) in 24hEE from energy balance during fasting. In these confirmatory analyses, on average thrifty individuals increased total ghrelin by 83 pg/mL (CI 31-134, P = .003) after 24-hour fasting while it remained unchanged in spendthrift individuals (mean change −34 pg/mL, P = .29), with an intergroup difference of 117 pg/mL (CI 36-199, P = .006; Fig. 4B). The change in total ghrelin following 24-hour fasting was further associated with the fasting-induced changes in SLEEP (r=−0.37, P = .01) and EE0 (r = 0.36, P = 0.01) while there were no associations with measures of substrate oxidation such as RQ, LIPOX, CARBOX, and PROTOX (all P > .23). When comparing lean (BMI < 25 kg/m2) vs overweight or obese individuals (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2), there was no interaction effect in the association between the decrease in 24hEE during fasting and the concomitant change in total ghrelin (P interaction = 0.28; Suppl. Figure 8 (23)). Additionally, there were no associations between the fasting-induced change in 24hEE or in total ghrelin and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance or fasting insulin concentration.

Figure 4.

A greater increase in plasma total ghrelin concentration after 24-hour fasting was associated with greater concomitant decrease in 24hEE (thriftier phenotype). Associations between fasting-induced changes in total ghrelin (A) and growth hormone (C) vs concomitant changes in 24hEE. In (A), a greater fasting-induced increase in total ghrelin by 200 pg/mL was related to a greater concomitant decrease in 24hEE by 54.6 kcal/day (CI 19.0-90.2). Comparison of fasting-induced changes in total ghrelin (B) and growth hormone (D) between thrifty and spendthrift subjects via unpaired t-test. Classification of subjects as spendthrift or thrifty is based on the median value of the decrease in 24hEE from energy balance during fasting (−165 kcal/day), such that thrifty subjects were those with a greater than median decrease in 24hEE. 24hEE, 24-hour energy expenditure; CI, confidence interval. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was used to quantify associations between continuous variables. Spearman nonparametric correlation analyses were also performed as sensitivity analyses to account for influential cases that may have inflated Pearson correlation values and similar results were obtained (A, Spearman’s ρ=–0.34, P = .02). Growth hormone values are shown on a logarithmic scale (log10) to account for skewed data distribution. 24hEE, 24-hour energy expenditure; CI, confidence interval.

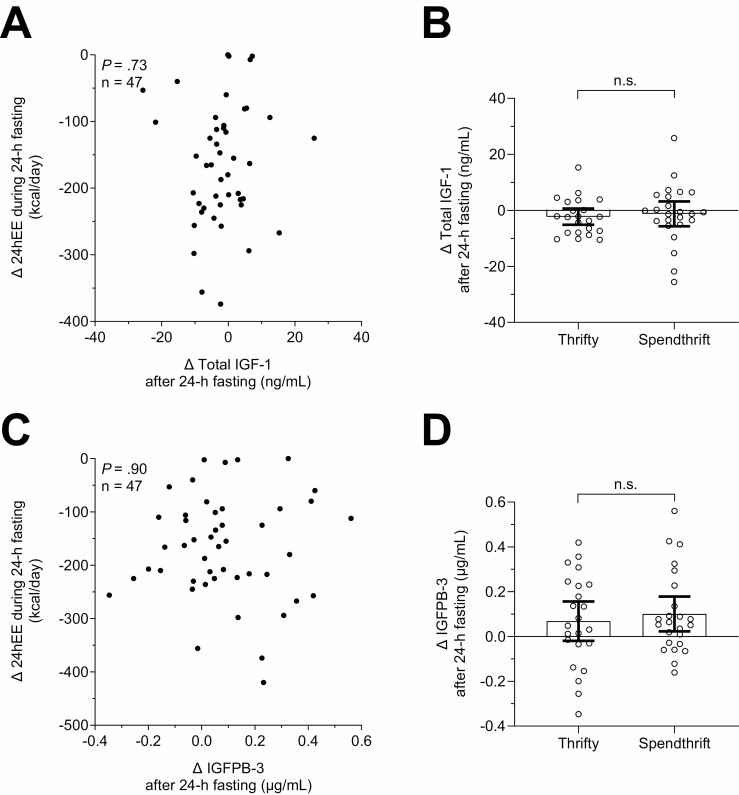

There were no associations between fasting-induced changes in GH, total IGF-1, and IGFBP-3 and concomitant changes in 24hEE (all P > .7; Figs. 4C, 5A, and 5C). Accordingly, these hormonal changes were comparable between thrifty and spendthrift individuals in group-wise comparisons (all P > .57; Figs. 4D, 5B, and 5D).

Figure 5.

Lack of associations between the decrease in 24hEE during fasting and changes in IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 concentrations. Associations between fasting-induced changes in total IGF-1 (A) and IGFBP-3 (C) vs concomitant changes in 24hEE. Comparison of fasting-induced changes in total IGF-1 (B) and IGFBP-3 (D) between thrifty and spendthrift subjects using the unpaired t-test. Classification of subjects as spendthrift or thrifty is based on the median value of the decrease in 24hEE from energy balance during fasting (−165 kcal/day), such that thrifty subjects were those with a greater than median decrease in 24hEE. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was used to quantify associations between continuous variables. Spearman nonparametric correlation analyses were also performed as sensitivity analyses to account for influential cases that may have inflated Pearson correlation values and similar results were obtained. 24hEE, 24-hour energy expenditure; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; IGFBP-3, IGF-binding protein 3.

Discussion

In the present study including 47 healthy subjects with normal glucose regulation, we found that plasma GH concentration substantially increased by 5-fold after 24-hour fasting while plasma total ghrelin, total IGF-1, and IGFBP-3 (the main binding protein for IGF-1) concentrations did not change overall but showed large interindividual variability. A greater increase in total ghrelin following 24-hour fasting was associated with a greater concomitant decrease in 24hEE, such that individuals with a greater decrease in 24hEE during fasting (thriftier phenotype) showed on average increased fasting-induced ghrelin levels compared with those who did not decrease 24hEE and ghrelin concentrations (more spendthrift phenotype).

Short-term Fasting Leads to a State of “GH resistance” Characterized by GH Hypersecretion and Unchanged IGF-1 Concentration

After 24-hour fasting, plasma GH on average increased by 5-fold confirming previous studies showing equivalent increases in GH (12-15). The increased GH concentration during prolonged fasting is likely caused by higher frequency and amplitude of GH secretion (13), which may play a role in the prevention of protein breakdown and loss of lean mass during famine (35). As ghrelin infusion stimulates GH release (36), we hypothesized that the fasting-induced increase in GH could be mediated by ghrelin. However, we did not find such association, which is in line with previous studies (12, 37, 38) and indicates that fasting-induced GH hypersecretion is ghrelin independent. The ghrelin–GH link was hypothesized in a previous human study that reported that the diurnal secretion patterns of total ghrelin and GH during fasting overlapped, which led the authors to speculate that ghrelin could be causal for the fasting-induced GH response (39). However, only 10 men participated in that study and total ghrelin levels were only measured every 6 hours, which may not fully characterize all the diurnal fluctuations in ghrelin secretion. In another study in which total ghrelin was measured every 3 hours over 84 hours of fasting, no association between ghrelin and GH was reported (12), consistent with our current findings.

In contrast to the marked increase in GH secretion, total IGF-1, the effector hormone of GH, did not increase its plasma concentration after 24-hour fasting and showed a trend to decrease, which would be consistent with previous rodent (40) and human (14) studies reporting a fasting-induced decrease in IGF-1. We found no association between the fasting-induced increase in GH and concomitant change in IGF-1, supporting the hypothesis that short-term starvation may induce a state of “GH resistance” characterized by GH hypersecretion but unchanged or even decreased IGF-1 concentration (14), likely mediated by fasting-induced inhibition of GH-mediated hepatic IGF-1 transcription (41). However, studies in which fasting-induced GH hypersecretion was suppressed followed by replacement with exogenous GH demonstrated that GH can retain some degree of IGF-1 regulation during fasting (14). We observed a small (~5%) but significant increase in IGFPB-3, which is the main binding protein of IGF-1 (14). Previous studies reported decreased (14) or unchanged (42, 43) IGFPB-3 concentrations during short-term fasting. This increase in IGFPB-3 would bind free IGF-1, lowering IGF-1 and thus inhibiting its activity to conserve energy in periods of starvation. This regulatory effect of IGFBPs has previously been described for IGFBP-1 (44).

Ghrelin Is a Novel Hormonal Mediator of Thriftiness During Short-term Fasting

Ghrelin is a mainly stomach-derived hormone but also produced in small amounts by other organs such as heart, lung, kidney, adrenal glands, testis, ovaries, thyroid gland, and pancreas (17). Ghrelin circulates in a nonacylated (mainly inactive) and in an acylated (mainly active) form (17), and its plasma concentration usually fluctuates during the day with an increase before meals and a decrease upon food consumption (18), qualifying ghrelin as a “hunger hormone” (45). Acute administration of ghrelin increases appetite and food intake in rodents (46, 47) and humans (48, 49).

In rodents, total ghrelin increases following a 48- to 72-hour fast (46, 50). However, in humans, multiple studies have failed to show an increase in total ghrelin after 24 to 72 hour fasting (37, 51, 52), which is in line with our current results showing no overall change in total ghrelin following 24-hour of fasting. That ghrelin does not change upon short-term fasting seems counterintuitive as it would be anticipated to increase during periods of famine to stimulate food intake in a setting of energy deficit. Chan et al. speculated that ghrelin tachyphylaxis may occur after prolonged fasting (52). Another explanation could be that the total ghrelin concentration measured following a 12-hour overnight fast (ie, our baseline pre-24-hour fasting value) already reflects the maximum physiologic level of a given individual and that prolonging fasting by an additional 24 hours does not further increase plasma ghrelin concentrations above its maximum physiologic level.

Despite no overall change in mean plasma ghrelin concentration, in the present study we observed a large variability in the fasting-induced ghrelin response (SD 150 pg/mL, range –452 to +308 pg/mL): some individuals were indeed able to increase plasma ghrelin concentration up to ~300 pg/mL after 24-hour fasting whereas others decreased it by the same or larger amount. This large interindividual variability is likely not due to error as we observed a strong intrasubject consistency in baseline ghrelin levels (ICC = 0.93) and moderately small intrasubject variation in repeated measures (CV = 13%). Importantly, the interindividual increase in plasma ghrelin concentration depended in part on the baseline level; namely, subjects with relatively lower total ghrelin concentration before 24-hour fasting showed a greater increase in total ghrelin after 24-hour fasting and vice versa (Fig. 3). Altogether, our data indicate that ghrelin secretion can be further stimulated following short-term fasting in some individuals, especially those with relatively lower baseline levels.

Interestingly, we found that the fasting-induced change in total ghrelin was associated with the concomitant decrease in 24hEE with fasting, such that individuals who increased total ghrelin following 24-hour fasting had a greater concomitant decrease in 24hEE (ie, greater metabolic slowing) during fasting conditions. These results were confirmed in sensitivity analyses by using the percentage change in 24hEE from eucaloric conditions and the change in adjusted 24hEE (ie, accounting for differences in body composition and other known EE determinants) which yielded similar results. A greater decrease in 24hEE during 24-hour fasting is indicative of a thrifty phenotype (2) which we have demonstrated is susceptible to future weight gain (3) and resistant to weight loss (4). When comparing thrifty vs spendthrift individuals arbitrarily defined by a greater/lower than median decrease in 24hEE during 24-hour fasting, respectively, we found that on average thrifty individuals increased total ghrelin by 83 pg/mL following fasting while ghrelin remained unchanged in spendthrift individuals (Fig. 4B). Thus, ghrelin might constitute another hormonal mediator of thriftiness in addition to epinephrine and leptin (5) and may promote energy efficiency and resistance to weight loss, in addition to increasing the drive to eat that may ultimately predispose thrifty individuals to weight gain.

This is in line with the concept by Cummings et al proposing ghrelin as a “thrifty gene product” designed to increase energy storage (53). Further, our current finding that ghrelin is inversely associated with EE is in line with previous human studies showing that a higher total ghrelin concentration is associated with lower resting metabolic rate (19, 20) and lower postprandial thermogenesis (19). Notably, there is evidence that ghrelin directly suppresses thermogenesis as ghrelin antibody treatment increases EE and reduces food intake in mice (22). Ghrelin may inhibit EE through its suppressive effects on sympathetic nervous system activity and brown adipose tissue thermogenesis (21). Taken together, current and previous results support the hypothesis that ghrelin regulates energy homeostasis by acting as a hormonal marker of increased energy efficiency, particularly during conditions of short-term fasting. Future studies are warranted to investigate the mechanisms by which ghrelin determines thriftiness and weight gain susceptibility, including repeated measurements of both active and inactive ghrelin prior to and following feeding with concomitant measurement of diet-induced thermogenesis, as well as assessments of hunger and appetite scores and ad libitum energy intake to demonstrate its orexigenic effect.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. We had a small female subgroup (n = 9). However, similar results were obtained when analyzing only men. Due to logistics of blood draws and technical limitations, we could not measure acylated (active) ghrelin; however, there is evidence that total and acylated ghrelin concentrations are closely related (20). We also did not specifically measure des-acylated ghrelin, which interacts with different receptors compared with acylated ghrelin and appears to have distinct actions on energy metabolism (54). By only measuring ghrelin at 1 time point (at 7:00 am in the morning before entering and after exiting the whole-room calorimeter), the observed changes in ghrelin secretion might also be due to diurnal changes in secretion patterns (55), although our repeated ghrelin measurements were highly correlated within individuals (ICC 0.93; Suppl. Figure 9 (23)). Future studies including measurements of both acylated and des-acylated ghrelin at different time points throughout the 24 hours are warranted to better characterize the diurnal changes in ghrelin concentration during prolonged fasting. Furthermore, as GH is secreted in a pulsatile fashion (7), the matutinal assessment of plasma GH concentration at only 1 time point might not adequately reflect the overall GH secretion throughout the day. Lastly, we did not measure free IGF-1 concentrations as it is likely more indicative than total IGF-1 levels to evaluate the bioactivity of the GH/IGF-I axis (56).

Conclusion

To conclude, short-term (24-hour) fasting induced a substantial, ghrelin-independent GH hypersecretion (5-fold increase) which did not further translate into increased IGF-1 secretion, possibly through hepatic “GH resistance”. Although its concentration did not change overall following 24-hour fasting, total ghrelin showed large interindividual variability, with some individuals decreasing and others increasing plasma concentration after prolonged fasting. Importantly, a greater fasting-induced increase in ghrelin was associated with a greater concomitant decrease in 24hEE, indicating that higher ghrelin concentrations constitute a novel hormonal hallmark of the thrifty phenotype, conferring increased energy efficiency.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the dietary, nursing, and technical staff of the Obesity and Diabetes Clinical Research Unit, National Institutes of Health in Phoenix, AZ, for their assistance in conducting this study. Most of all, the authors thank the volunteers for their participation in the study.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 24hEE

24-hour energy expenditure

- BMI

body mass index

- CV

coefficient of variation

- EBL

energy balance

- EE

energy expenditure

- EE0

nonactivity energy expenditure

- FST

24-hour fasting

- GH

growth hormone

- ICC

intraclass correlation coefficient

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor 1

- IGFBP-3

IGF-binding protein 3

- PFAT

percentage body fat

- RQ

respiratory quotient

- SLEEP

sleeping metabolic rate

- WMD

weight-maintaining diet

Contributor Information

Tim Hollstein, Phoenix Epidemiology and Clinical Research Branch, Phoenix, AZ 85016, USA; Institute of Diabetes and Clinical Metabolic Research, 24195 Kiel, Germany.

Alessio Basolo, Phoenix Epidemiology and Clinical Research Branch, Phoenix, AZ 85016, USA.

Yigit Unlu, Phoenix Epidemiology and Clinical Research Branch, Phoenix, AZ 85016, USA.

Takafumi Ando, Phoenix Epidemiology and Clinical Research Branch, Phoenix, AZ 85016, USA.

Mary Walter, Clinical Core Lab, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Jonathan Krakoff, Phoenix Epidemiology and Clinical Research Branch, Phoenix, AZ 85016, USA.

Paolo Piaggi, Phoenix Epidemiology and Clinical Research Branch, Phoenix, AZ 85016, USA; Department of Information Engineering, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy.

Funding

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. P.P. was supported by the program “Rita Levi Montalcini for young researchers” from the Italian Minister of Education and Research. T.H. was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Project 413490537.

Author Contributions

T.H. carried out the initial analyses, interpreted the results, wrote the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. A.B. interpreted the results and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Y.U. interpreted the results and approved the final manuscript as submitted. T.A. interpreted the results and approved the final manuscript as submitted. M.W. performed hormonal measurements and approved the final manuscript as submitted. J.K. interpreted the results, edited the initial draft of the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. P.P. designed the study, interpreted the results, edited the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. P.P.is the guarantor of this work, and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Data Availability

All datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Clinical Trial Information

The trial NCT00523627 was registered on August 31, 2007.

References

- 1. Thearle MS, Pannacciulli N, Bonfiglio S, Pacak K, Krakoff J. Extent and determinants of thermogenic responses to 24 hours of fasting, energy balance, and five different overfeeding diets in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(7):2791-2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Piaggi P. Metabolic determinants of weight gain in humans. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019;27(5):691-699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hollstein T, Ando T, Basolo A, Krakoff J, Votruba SB, Piaggi P. Metabolic response to fasting predicts weight gain during low-protein overfeeding in lean men: further evidence for spendthrift and thrifty metabolic phenotypes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;110(3):593-604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reinhardt M, Thearle MS, Ibrahim M, et al. A Human thrifty phenotype associated with less weight loss during caloric restriction. Diabetes. 2015;64(8):2859-2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hollstein T, Basolo A, Ando T, et al. Recharacterizing the metabolic state of energy balance in thrifty and spendthrift phenotypes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(5):1375-1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hollstein T, Piaggi P. Metabolic factors determining the susceptibility to weight gain: current evidence. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9(2):121-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hartman ML, Veldhuis JD, Thorner MO. Normal control of growth hormone secretion. Horm Res. 1993;40(1-3):37-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chong PK, Jung RT, Scrimgeour CM, Rennie MJ, Paterson CR. Energy expenditure and body composition in growth hormone deficient adults on exogenous growth hormone. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1994;40(1):103-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gregory JW, Greene SA, Jung RT, Scrimgeour CM, Rennie MJ. Changes in body composition and energy expenditure after six weeks’ growth hormone treatment. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66(5):598-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Svensson J, Lönn L, Jansson JO, et al. Two-month treatment of obese subjects with the oral growth hormone (GH) secretagogue MK-677 increases GH secretion, fat-free mass, and energy expenditure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(2):362-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tagliaferri M, Scacchi M, Pincelli A, et al. Metabolic effects of biosynthetic growth hormone treatment in severely energy-restricted obese women. Int J Obes. 1998;22(9):836-841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Espelund U, Hansen TK, Højlund K, et al. Fasting unmasks a strong inverse association between ghrelin and cortisol in serum: studies in obese and normal-weight subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(2):741-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ho KY, Veldhuis JD, Johnson ML, et al. Fasting enhances growth hormone secretion and amplifies the complex rhythms of growth hormone secretion in man. J Clin Invest. 1988;81(4):968-975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nørrelund H, Frystyk J, Jørgensen JOL, et al. The effect of growth hormone on the insulin-like growth factor system during fasting. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(7):3292-3298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Veldhuis JD. Neuroendocrine control of pulsatile growth hormone release in the human: relationship with gender. Growth Horm IGF Res. 1998;8:49-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tabakian A, Juillard L, Laville M, Joly M-O, Laville M, Fouque D. Effects of recombinant growth factors on energy expenditure in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Miner Electrolyte Metab. 1998;24(4):273-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Khatib N, Gaidhane S, Gaidhane AM, et al. Ghrelin: ghrelin as a regulatory peptide in growth hormone secretion. J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2014;8(8):MC13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cummings DE, Purnell JQ, Frayo RS, Schmidova K, Wisse BE, Weigle DS. A preprandial rise in plasma ghrelin levels suggests a role in meal initiation in humans. Diabetes. 2001;50(8):1714-1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. St-Pierre DH, Karelis AD, Cianflone K, et al. Relationship between ghrelin and energy expenditure in healthy young women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(12):5993-5997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marzullo P, Verti B, Savia G, et al. The relationship between active ghrelin levels and human obesity involves alterations in resting energy expenditure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(2):936-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yasuda T, Masaki T, Kakuma T, Yoshimatsu H. Centrally administered ghrelin suppresses sympathetic nerve activity in brown adipose tissue of rats. Neurosci Lett. 2003;349(2):75-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zakhari JS, Zorrilla EP, Zhou B, Mayorov AV, Janda KD. Oligoclonal antibody targeting ghrelin increases energy expenditure and reduces food intake in fasted mice. Mol Pharm. 2012;9(2):281-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hollstein T. Supplemental Material: Effects of short-term fasting on the ghrelin/gh/igf-1 axis in healthy humans: the role of ghrelin in the thrifty phenotype. 2022. Online data repository. Deposited May 1, 2022. 10.7910/DVN/FHV2M0 [DOI]

- 24. Pannacciulli N, Salbe AD, Ortega E, Venti CA, Bogardus C, Krakoff J. The 24-h carbohydrate oxidation rate in a human respiratory chamber predicts ad libitum food intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(3):625-632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Miller DS, Mumford P. Gluttony. 1. An experimental study of overeating low- or high-protein diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 1967;20(11):1212-1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. American Diabetes A. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Suppl 1):S81-S90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Heinitz S, Basolo A, Piaggi P, Piomelli D, Jumpertz von Schwartzenberg R, Krakoff J. Peripheral endocannabinoids associated with energy expenditure in Native Americans of southwestern heritage. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(3):1077-1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ravussin E, Lillioja S, Anderson TE, Christin L, Bogardus C. Determinants of 24-hour energy expenditure in man. Methods and results using a respiratory chamber. J Clin Invest. 1986;78(6):1568-1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heinitz S, Hollstein T, Ando T, et al. Early adaptive thermogenesis is a determinant of weight loss after six weeks of caloric restriction in overweight subjects. Metab Clin Exp. 2020;110:154303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schutz Y, Ravussin E, Diethelm R, Jequier E. Spontaneous physical activity measured by radar in obese and control subject studied in a respiration chamber. Int J Obes. 1982;6(1):23-28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Piaggi P, Krakoff J, Bogardus C, Thearle MS. Lower “awake and fed thermogenesis” predicts future weight gain in subjects with abdominal adiposity. Diabetes. 2013;62(12):4043-4051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Abbott WG, Howard BV, Christin L, et al. Short-term energy balance: relationship with protein, carbohydrate, and fat balances. Am J Physiol. 1988;255(3 Pt 1):E332-E337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bender R, Lange S. Adjusting for multiple testing—when and how? J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(4):343-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Reinhardt M, Schlogl M, Bonfiglio S, Votruba SB, Krakoff J, Thearle MS. Lower core body temperature and greater body fat are components of a human thrifty phenotype. Int J Obes (Lond). 2016;40(5):754-760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Møller N, Jørgensen JOL. Effects of growth hormone on glucose, lipid, and protein metabolism in human subjects. Endocr Rev. 2009;30(2):152-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Takaya K, Ariyasu H, Kanamoto N, et al. Ghrelin strongly stimulates growth hormone release in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(12):4908-4911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nørrelund H, Hansen TK, Ørskov H, et al. Ghrelin immunoreactivity in human plasma is suppressed by somatostatin. Clin Endocrinol. 2002;57(4):539-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Natalucci G, Riedl S, Gleiss A, Zidek T, Frisch H. Spontaneous 24-h ghrelin secretion pattern in fasting subjects: maintenance of a meal-related pattern. Eur J Endocrinol. 2005;152(6):845-850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Muller AF, Lamberts SWJ, Janssen JAMJL, et al. Ghrelin drives GH secretion during fasting in man. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;146(2):203-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Frystyk J, Delhanty PJD, Skjærbæk C, Baxter RC. Changes in the circulating IGF system during short-term fasting and refeeding in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1999;277(2):E245-E252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Beauloye VR, Willems B, De Coninck V, Frank SJ, Edery M, Thissen J-P. Impairment of liver GH receptor signaling by fasting. Endocrinology. 2002;143(3):792-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bang P, Brismar K, Rosenfeld RG, Hall K. Fasting affects serum insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) and IGF-binding proteins differently in patients with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus versus healthy nonobese and obese subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;78(4):960-967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bereket A, Wilson TA, Blethen SL, et al. Effect of short-term fasting on free/dissociable insulin-like growth factor I concentrations in normal human serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(12):4379-4384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Allard JB, Duan C. IGF-binding proteins: why do they exist and why are there so many? Front Endocrinol. 2018;9. Published Apr 9, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pradhan G, Samson SL, Sun Y. Ghrelin: much more than a hunger hormone. Curr Opin Clin Nutr. 2013;16(6):619-624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tschöp M, Smiley DL, Heiman ML. Ghrelin induces adiposity in rodents. Nature. 2000;407(6806):908-913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nakazato M, Murakami N, Date Y, et al. A role for ghrelin in the central regulation of feeding. Nature. 2001;409(6817):194-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wren AM, Seal LJ, Cohen MA, et al. Ghrelin enhances appetite and increases food intake in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(12):5992-5992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Druce MR, Neary NM, Small CJ, et al. Subcutaneous administration of ghrelin stimulates energy intake in healthy lean human volunteers. Int J Obes. 2006;30(2):293-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lee H-M, Wang G, Englander EW, Kojima M, Greeley GH Jr. Ghrelin, a new gastrointestinal endocrine peptide that stimulates insulin secretion: enteric distribution, ontogeny, influence of endocrine, and dietary manipulations. Endocrinology. 2002;143(1):185-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nuttall FQ, Almokayyad RM, Gannon MC. The ghrelin and leptin responses to short-term starvation vs a carbohydrate-free diet in men with type 2 diabetes; a controlled, cross-over design study. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2016;13:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chan JL, Bullen J, Lee JH, Yiannakouris N, Mantzoros CS. Ghrelin levels are not regulated by recombinant leptin administration and/or three days of fasting in healthy subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(1):335-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cummings DE, Foster-Schubert KE, Overduin J. Ghrelin and energy balance: focus on current controversies. Curr Drug Targets. 2005;6(2):153-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wang Y, Wu Q, Zhou Q, et al. Circulating acyl and des-acyl ghrelin levels in obese adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1). Published Feb 17, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Koutkia P, Schurgin S, Berry J, et al. Reciprocal changes in endogenous ghrelin and growth hormone during fasting in healthy women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289(5):E814-E822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Janssen JAMJL, Lamberts SWJ. Is the measurement of free IGF-I more indicative than that of total IGF-I in the evaluation of the biological activity of the GH/IGF-I axis? J. Endocrinol. Invest 1999;22(4):313-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.