Summary

Familial dysautonomia (FD) is a currently untreatable, neurodegenerative disease caused by a splicing mutation (c.2204+6T>C) that causes skipping of exon 20 of the elongator complex protein 1 (ELP1) pre-mRNA. Here, we used adeno-associated virus serotype 9 (AAV9-U1-FD) to deliver an exon-specific U1 (ExSpeU1) small nuclear RNA, designed to cause inclusion of ELP1 exon 20 only in those cells expressing the target pre-mRNA, in a phenotypic mouse model of FD. Postnatal systemic and intracerebral ventricular treatment in these mice increased the inclusion of ELP1 exon 20. This also augmented the production of functional protein in several tissues including brain, dorsal root, and trigeminal ganglia. Crucially, the treatment rescued most of the FD mouse mortality before one month of age (89% vs 52%). There were notable improvements in ataxic gait as well as renal (serum creatinine) and cardiac (ejection fraction) functions. RNA-seq analyses of dorsal root ganglia from treated mice and human cells overexpressing FD-ExSpeU1 revealed only minimal global changes in gene expression and splicing. Overall then, our data prove that AAV9-U1-FD is highly specific and will likely be a safe and effective therapeutic strategy for this debilitating disease.

Keywords: ELP1, familial dysautonomia, neurodegenerative disease, splicing, therapeutics

Familial dysautonomia (FD) is a currently untreatable neurodegenerative disease. We evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of a new class of RNA molecules in an FD mouse model. The treatment, recovering most of the mortality and neuromuscular function, holds promise for clinical application.

Introduction

Hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathies are a heterogeneous group of rare peripheral neuropathies, classified according to clinical characteristics, mode of inheritance and specific genetic markers.1 The most common hereditary neuropathy is the type III hereditary neuropathy,2 named familial dysautonomia (FD [MIM: 223900]), previously known as Riley-Day syndrome.3 FD is an autosomal-recessive genetic disease characterized by sensory and autonomic dysfunction that almost exclusively affects people of Ashkenazi, Eastern European Jewish extraction, occurring in approximately one in 3,600 live births in these people.4 FD has a complex phenotype including defective lacrimation, abnormal temperature and pain perception, proprioceptive ataxia with poor coordination and balance, absent deep tendon reflexes, kyphoscoliosis, gastrointestinal dysmotility, chronic lung disease, cardiovascular lability with postural hypotension and hypertensive crises, optic neuropathy, and emotional anxiety.1,5, 6, 7 FD-affected individuals have low birth weight and the neonatal period is characterized by hypotonia and little or no sucking reflex.8 Current available treatments are mainly symptomatic.9, 10, 11 The major mutation in FD is a T to C nucleotide change in the 5′ splice site of intron 2012, 13, 14 of ELP1 (MIM: 603722); all affected individuals have at least one copy of the c.2204+6T>C splice site mutation (GenBank: NM_003640.3: c.2204+6T>C) with 99.5% of all FD persons being homozygous for this mutation.4,12,13,15 The c.2204+6T>C intronic substitution induces exon 20 skipping and the resulting transcript has a premature stop codon in exon 21 and is degraded by nonsense-mediated mRNA decay.16 In FD-affected individuals, the percentage of ELP1 exon 20 skipping is highly variable among different tissues with the lowest levels of exon inclusion in the central and peripheral nervous system.17,18 ELP1 is a 150 kDa protein and the large size of its coding transcript (5.9 kb) makes a classical gene therapy approach with adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors difficult. ELP1 is a member of the six-subunit Elongator complex (ELP1-ELP6). A number of cellular functions have been associated with the Elongator complex.19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 Defects in Elongator function have been shown to affect transcriptional elongation.21,26,27 In embryos, ELP1 is essential for the expression of genes responsible for nervous system development and, consistent with its interaction with chromatin and RNA polymerase II, ELP1 impacts long gene transcripts.28 In addition, ELP1 can catalyze protein translation through tRNA modifications at the wobble base (U34) position.29,30 A conditional knockout mouse, in which Elp1 expression was selectively ablated in the peripheral nervous system, had reduced levels of U34 tRNA modification and a defective translation of codon bias genes in dorsal root ganglia.29,31,32

The mouse ELP1 is 80% identical to human ELP1 at the amino acid level33 and several FD mouse models have therefore been generated.18,34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 We recently created a phenotypic humanized FD mouse model40 that has most of the major symptoms and recapitulates the human splicing defect in a tissue-specific manner. This mouse contains the entire human ELP1 carrying the FD mutation (c.2204+6T>C) and it is hypomorphic for the endogenous Elp1 (IkbkapΔ20/flox).35,36 This model offers the opportunity to test the efficacy of therapeutic approaches aimed at targeting the splicing defect. Recently, several strategies based on antisense oligonucleotides,41 chemical compounds,42, 43, 44, 45 and modified U1 snRNA46 have been shown to correct the ELP1 splicing defect. However, only one of these molecules, kinetin, has been tested in a symptomatic FD animal model and very high doses of kinetin were necessary to achieve a modest correction of ELP1 splicing in vivo.44,47,48

Here, we explored the therapeutic efficacy of ELP1 splicing correction using exon-specific U1 small nuclear RNAs (ExSpeU1) delivered by AAV vectors. ExSpeU1s are modified U1 snRNAs (∼86 nt long) that target intronic sequences through their engineered 5′ tail.49 They are encoded by a small gene of around 700 bps and therefore are suitable for AAV packaging. By binding the 5′ splice site downstream of targeted exons, ExSpeU1s can correct aberrant splicing in several cellular50, 51, 52, 53 and mouse49,54, 55, 56 models. They can also be used to promote inclusion of normally alternatively spliced exons.57 We previously delivered an ExSpeU1 to extend survival, from 10 days to approximately 6 months, in mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy.58 In a previous study also, we established that AAV9-U1-FD rescues ELP1 exon 20 splicing in the asymptomatic TgFD9 mouse.46 Here we tested the efficacy of our U1-based therapy in rescuing disease progression in the phenotypic FD mouse model. Our positive results suggest that this approach will be an effective and safe treatment intervention.

Material and methods

Animal models

All experimental procedures involving animals were approved by the Italian authorities and ethics committees, in compliance with national and international law and policies (European Directive 2010/63/EU). Mice were housed and handled in the animal facility of the International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology in Trieste, provided with free access to food and water, maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle. To genotype the mice, genomic DNA was extracted from biopsies and PCR was performed with specific primers (see supplemental methods) to discriminate the different mIkbkap alleles and to detect the hIkbkap transgene.

To generate the FD mice we crossed the TgFD9;Ikbkapflox/flox transgenic mouse line (a TgFD9 transgenic mouse18 homozygous for the Ikbkapflox allele36) with heterozygous IkbkapΔ20 mice.36 Following Mendel’s law of segregation in the F1 progeny, we obtained two possible genotypes: the TgFD9;Ikbkap Δ20/flox (FD phenotypic mouse model) and the TgFD9;Ikbkapflox/+ (control littermates).40 The expected ratio in the F1 progeny was 1 in 2 (50%), but the real ratio obtained was remarkably lower, confirming an important embryonic lethality phenotype.40 All experimental treatments on mice were always performed by two operators, one of whom was unaware of the genotypes and treatments.

Mouse tissues collection

After euthanasia, tissues of interest were collected in Safe-Lock tubes (Eppendorf) at two time points: PND-10 and PND-90. The dissection was performed in PBS buffer on an ice-cold plate, and the extracted samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C, ready for further analysis.

AAV9 production

AAV9 vectors were prepared by Genethon, by cloning the U1 expression cassette into the AAV9 backbone using the XbaI site and prepared as previously described.46,59

AAV9-U1-FD delivery

New-born mice received an intra cerebroventricular (i.c.v.) and an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection with AAV9-ExSpeU1 Ik10, at PND-0 and 2, respectively. i.c.v. injections were performed with a Neuro Syringe with a 33-gauge needle (Hamilton: 65460-03, Model 75 RN) and a total volume of 4 μL/animal was injected (2 μL per ventricle); i.p. injections were performed with an insulin syringe with a 30-gauge needle (BD-Medical: 320840) and a total volume of 25 μL/animal was injected. Each injected animal received a final dose of 1.6 × 1011 VG/mouse. At the same time, a control group was treated with saline solution only, respecting the same timing and conditions.

RNA isolation and mRNA analysis

Total RNA was extracted with Trizol (Thermo Fisher) following the manufacturer’s instructions. First strand cDNA synthesis was obtained using reverse-transcriptase enzyme Superscript Vilo Master Mix (Thermo Fisher). Human ELP1 splicing analysis was performed by endpoint PCR using specific primers (see supplemental methods). PCR condition were 95°C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s; and 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were analyzed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Band intensity was quantified with ImageJ Software (NIH) and the statistical analysis performed with Prism (GraphPad, USA).

ExSpeU1-FD detection was determined using RT-qPCR on DNase-treated RNA extracted from different organs of interest. qPCR was performed with iQ-SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories) using specific primers (see supplemental methods). The expression levels of ExSpeU1-FD were expressed as percentage of the U1 endogenous or directly normalized on housekeeping gene (Gapdh).

Protein isolation and western blot analysis

Previously collected mouse tissues were transferred in ice-cold RIPA buffer (Sigma) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and completely homogenized using ceramic beads MagNA Lyser (Roche Diagnostic). Debris was discarded after centrifugation and total protein concentration was measured with protein assay dye reagent (Bio-Rad). A total of 15 μg of protein was separated on NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris precast gels (ThermoFisher) and wet-transferred to 0.2 μm nitrocellulose membranes (Whatman). The membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat milk for 1 h at room temperature and successively incubated overnight at +4°C with primary antibody diluted as follows: anti-IKAP-CT (Anaspec as-54494; 1:1,000) and anti-GAPDH (Abcam ab8245; 1:7,000). Goat anti-rabbit and conjugated anti-mouse IgG HRP were used as secondary antibodies (Dako 1:2,000). Detection was performed with ECL (Thermo Fisher) followed by exposure to UVItec Cambridge Alliance. The intensity of protein bands was measured with UVItec Alliance software and confirmed with ImageJ software (NIH).

Behavioral analysis in mice

At the test day, age- and sex-matched mice were transported in their cages to the behavioral testing room and allowed to adapt for at least 1 h.

Surface righting

This test is performed by turning the pup onto its back and recording the time for them to turn over onto their belly;60 the test requires body control and is used to measure postural imbalance. PND-6 pups were put on their backs on a paper sheet and held for 3–5 s; when released, the time to return to prone position was recorded. 1 min was fixed as cut-off, beyond which the test was stopped.

Limb clasping on tail suspension

Limb clasping is a motor test to quantify defects in corticospinal function.61 Mice were gently removed from their cages and suspended by the tail for 5–10 s, then returned to their home cage. A clasping score was assigned to each mouse following a scale from 0 to 4. Score 0 was used when mice displayed no limb clasping, showing a normal escape extension. Score 1 was assigned when one hind limb exhibits splay or loss of mobility; score 2 when both hind limbs exhibit incomplete splay and or mobility loss; score 3 when both hind limbs exhibit clasping with curled toes; and score 4 when forelimbs and hind limbs exhibit clasping with curled toes.

Gait assay

To assess ataxia and gait abnormalities, mice footprint patterns were analyzed.62,63 The mouse was placed at the entrance of a dark tunnel (10 cm wide × 10 cm high × 50 cm long) with the bottom surface lined with white paper and a bright light source at the end. Mouse paws were stained with nontoxic paint, marking fore and hind paws with different colors. The mouse walking down the tunnel left a pattern of footprints on the paper that can be analyzed. Footprints were scanned and transformed into digital images, to be analyzed with ImageJ Software (NIH). The paw angle variation between fore and hind paws of each step was measured and a final average for each single mouse was plotted on the graph.

Rotarod

Motor coordination and balance was tested at 2 and 3 months after birth through the use of an accelerating rotarod (manufactured at ICGEB Trieste). The rotarod is a rotating cylinder of 4 cm diameter covered with sandpaper to improve the grip, on which the mouse has to walk forward to keep from falling off. The test started at a speed of 4 rpm which gradually accelerated to reach 40 rpm after 300 s (1 rpm acceleration approximately every 8.3 s). Each mouse received one or two practice trials before starting the real test. Latency to fall time was measured three times, allowing a resting period of at least 10 min between cycles; a cut-off of 300 s was used per session. The final score was an average of the three sessions.

Four-limbs hanging test

The four-limbs hang test was used to measure the ability of mice to sustain limb tension in opposition to gravitational force. The mouse was placed on a grid 20 cm above a cage filled with soft bedding; the grid was then turned upside down and latency to fall time was recorded.64 Each mouse received one practice trial before starting the real test. Latency to fall time was measured for three times, allowing a resting period of 5 min at least between cycles, and a cut off of 60 s was used per session. The final score was an average of the three sessions.

Blood collection

Blood collection was performed once in the life of each animal (no multiple blood sample collections were performed in this study). Saphenous vein was used to collect blood, without the use of anesthesia.65 The animal was restrained manually and the hind leg was shaved until saphenous vein was visible. Using an 18-gauge needle, the vein was punctured and the blood collected in a 1.5 mL tube (Eppendorf). A total volume of 50 μL (maximum 100 μL) was collected, to not exceed 10% of the total blood volume. The bleeding stopped almost immediately after the release. Mice were then safely returned to their home cages.

Creatinine assay

Serum creatinine levels were measured with an enzymatic assay kit (Mouse Creatinine Assay Kit, Crystal Chem). The serum was obtained from the blood collection (described above); briefly, whole blood was allowed to clot by leaving it at room temperature for 30 min, and then the red cells were discarded by centrifugation.

Weight and life span monitoring

Body weight was recorded starting from birth (PND-0). All different genotypes were kept balanced in term of sex ratio (1:1 female:male) and death events were daily checked.

Echocardiography exam

To evaluate cardiac function and morphology, transthoracic two-dimensional echocardiography was performed on mice sedated with 1.5% isoflurane at 6 and 12 weeks of age, using a Visual Sonics Vevo 2100 Ultrasound (FUJIFILM VisualSonics) equipped with a 30-MHz linear array solid-state transducer. The heart rate of all animals was kept over 400 beats per minute and the body temperature at 37°C, accordingly to procedures describe by Zacchigna et al.66 Systolic function was assessed on B-mode images, using a multi-planar evaluation (modified Simpson’s method). As per manufacturer’s instructions (FUJIFILM VisualSonics), the ejection fraction (EF) was calculated using a modified Simpson’s rule.

Creation of ExSpeU1-FD HEK293 Flp-In T-REx stable clones

HEK293 Flp-In T-REx cells were grown according to manufacturer’s instructions (ThermoFisher). For stable integration, we cloned three copies of the ExSpeU1-FD (shift 10) into the pcDNA5/FRT/TO vector (ThermoFisher) using different restriction sites (BamHI-BamHI, HindIII-KpnI, and XhoI-ApaI). The included 3XExSpeU1-FD cassette was verified by sequencing. Stable clones were produced by co-transfecting the 3XExSpeU1-FD plasmid in HEK293 Flp-In T-REx cells with the pOG44 plasmid, whereas control empty clones were obtained by co-transfecting the pOG44 plasmid with an empty pcDNA5/FRT/TO vector. After 48 h, transfected cells were selected with Blasticidin. The stable clones were analyzed after 2–4 passages (split 1:3). Transient transfection of stable clones with the pTB-IKBKAP minigene was performed as previously described.46 To quantify the specific expression level of ExSpeU1-FD, total RNA was treated with DNase and qPCRs were performed using specific primers (see supplemental methods). The efficiency (Eff) of the U1WT and ExSpeU1-FD PCR reactions was calculated by the following equation: Eff = 10∗(−1 / slope) −1.

RNA sequencing and data analysis

Messenger RNA sequencing (mRNA-seq) was performed by IGA Technology Services or Area Science Park Sequencing facility. HEK293 Flp-In T-REx stable clones expressing ExSpeU1-FD and dorsal root ganglia of FD mice were purified with TRIazol (Ambion) and quality of total RNA was assessed using Agilent 2100 nano bioanalyzer microfluidic chips and a Nanodrop UV spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher). Only RNA with a RIN value of 8.0 or higher and a 28s/18s ratio ∼1.8 was taken forward for sample preparation. The size distribution of HEK293 Flp-In T-REx cells and mouse-derived libraries were estimated by electrophoresis on Agilent high-sensitivity bioanalyzer microfluidic chips and yield was quantified using the KAPA library quantification kit (KK4824, Kapa Biosystems). The libraries were pooled at equimolar concentrations and diluted before loading onto the flow cell of a NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina) for both clustering and sequencing. Amplified clusters in the flow cell were then sequenced with 150-base paired-end reads using the NovaSeq 6000SP Reagent Kit v1 (300 cycle) (Illumina Inc.). Real-time image analysis and base calling were performed on a NovaSeq 6000 instrument using the recommended sequencing control software. Illumina standard software was used for de-multiplexing and producing FASTQ sequence files. FASTQ raw sequence files were subsequently quality checked with FASTQC software (v.0.11.3 http://www.bioinformatics.bbsrc.ac.uk/projects/fastqc) and sequences including adaptor dimers, mitochondrial, or ribosomal sequences were discarded. The resulting set of trimmed reads from HEK293 Flp-In T-REx cells and mouse dorsal root ganglia were then mapped onto human GRCh38/hg38 and a modified version of Mus musculus GRCm38 (mm10) using the Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference (STAR) algorithm.67 Differential gene expression analysis from HEK293 Flp-In T-REx cells and mouse dorsal root ganglia was performed by the Bioconductor package DESeq2 (v.1.32) using default parameters.68 To detect outlier data after normalization, we used R packages, and before testing differential gene expression, we dropped all genes with low normalized mean counts to improve testing power while maintaining type I error rates. Estimated false discovery rate (FDR) values for each gene were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Prior to analysis, genes without a poly-A tail were discarded. Features with baseMean ≥ 100 counts, padj ≤ 0.05, and absolute logarithmic base 2-fold change (log2FC) ≤ −1 or ≥1 were considered having a significant altered expression. For genome-wide splicing analysis, BAM files produced from STAR mapping were input into rMATS,69 using Human GRCh38/hg38 and Mus musculus GRCm38 (mm10) annotations. For detection of alternative splicing (AS) patterns, human or mouse annotations were generated containing all consecutive spliced and unspliced exon-intron-exon triads from hg38 (Gencode v29) and mm10 (Gencode v25). For transgenic mouse line analysis, we create a modified version of Mus musculus GRCm38 containing an ad hoc genomic sequence of the human ELP1 gene. A modified version of the gtf file, including the genomic positions of the transgenic feature, was generated based on the genome modification and used as annotation. Five basic types of AS were analyzed: skipped exons (SE), retained introns (RI), mutually exclusive exons (MXE), alternative 5′ splice sites (A5SS), and alternative 3′ splice sites (A3SS). Read coverage was based on actual reads as used in Irimia et al.70 SE, RI, and MXE types with an actual read mapping to all exclusion splice junction ≥20 were considered whereas for A5SS and A3SS types ≥40 actual reads mapping to the sum of all splice junctions involved in the specific event were considered. Estimated FDR values for each gene were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. The threshold parameters were set at FDR value ≤0.05 and absolute inclusion level difference ≤−0.2 or ≥0.2.

Pathway analysis by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis

The lists of significant differentially expressed genes in HEK293 Flp-In T-REx stable clones expressing ExSpeU1-FD and dorsal root ganglia of FD were uploaded into the IPA software (Qiagen). The “core analysis” function included in the software was used to interpret the differentially expressed data, which included biological processes, canonical pathways, and gene networks. Each gene identifier was mapped to its corresponding gene object in the Ingenuity Pathway Knowledge Base (IPKB). A −log(B-H p value) > 1.3 was considered having a significant relevance.

Results

AAV9-U1-FD treatment rescues life span in a familial dysautonomia mouse

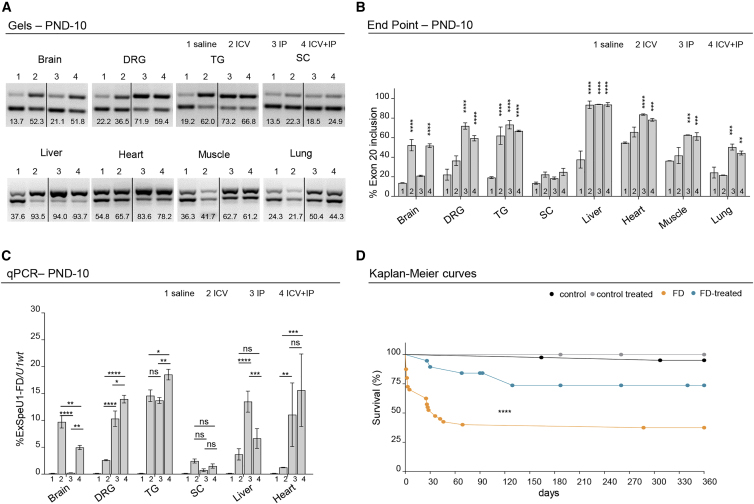

To establish the most effective AAV9-U1-FD delivery system for correcting the FD splicing defect in vivo, we initially used the asymptomatic TgFD9 transgenic mouse. This mouse contains the entire human ELP1 with the c.2204+6T>C FD mutation along with the wild-type (WT) mouse Elp1.18 Using this model, we previously demonstrated that intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of AAV9-U1-FD at postnatal day 0 (PND-0) rescued ELP1 exon 20 inclusion and functional protein accumulation in different mouse tissues.46 However, through this delivery route, possibly due the relative impermeability of the brain blood barrier, the vector did not reach the brain efficiently, as observed using another AAV9-U1.58 To improve tissue distribution and evaluate, in more detail, the effect of AAV9-U1-FD in disease-relevant tissues, such as dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglia,71 we compared intracerebral ventricular injection (i.c.v.), intraperitoneal injection (i.p.), and a combination of the two treatments (i.c.v. + i.p.). This revealed that the dual injection scheme was the most efficient delivery approach to increase ELP1 exon 20 inclusion in several FD-affected tissues, including brain, dorsal root ganglia, trigeminal ganglia, heart, and muscle (Figures 1A and 1B). Consistent with the fact that DRGs are outside the CNS, we found that i.p. compared to i.c.v. delivery reaches these ganglia more efficiently. There was no effect on ELP1 splicing in spinal cord. To clarify the effect of the delivery method on the expression of FD-ExSpeU1 snRNA and the resulting splicing correction, we measured the levels of FD-ExSpeU1 by qPCR in brain, dorsal root ganglia, trigeminal ganglia, spinal cord, liver, and heart. The results show a good correlation between the level of FD-ExSpeU1 snRNA and the improvement in ELP1 exon 20 splicing and confirmed that the combined i.c.v.-i.p. treatment reaches efficiently several FD-affected tissues (Figure 1C). Considering the optimal splicing rescue efficiency obtained in several target tissues, through the combined i.c.v. and i.p. injections, this dual route of administration was selected for the treatment of the phenotypic FD mouse model, TgFD9; Elp1 Δ20/flox.40 This model carries the entire human ELP1 with the c.2204+6T>C FD mutation and expresses very low levels of endogenous Elp1 through the introduction of two distinct mutations. Exon 20 is deleted on one allele (Elp1Δ20) and the second allele is hypomorphic (Elp1flox).36,40 This mouse recapitulates the tissue-specific splicing defects characteristic of FD and most of the disease phenotypes, with approximately 50% of mice dying by the first month of age due to its perinatal fragility.40,44 New-born FD mice were i.c.v. and i.p. injected with AAV9-U1-FD (1.6 × 1011 VG/mouse: i.c.v. = 2.2 × 1010 VG and i.p. 1.375 × 1011 VG) at PND-0 and PND-2, respectively, and analyzed for survival. The total dose of 8 × 1013 VG/kg (1.6 × 1011 VG/pup), is comparable to the approved dosage of the AAV9-based systemic gene therapy for spinal muscular atrophy (e.g., Zolgensma 1.1 × 1014 VG/kg) (https://www.fda.gov/media/126109/download)72 and has been previously shown to be effective on ELP1 splicing in the asymptomatic mice.46 Crucially, the treatment rescued most of the FD mouse mortality before 1 month of age (Figure 1D). At PND-30, 89% of the FD mice, treated with AAV9-U1-FD, were alive compared with only 52% in the untreated group (median of survivals in FD = 36 versus FD treated >360, p < 0.001). The survival curve shows that most of the therapeutic rescue occurs before PND-120 and that no further deaths were observed thereafter in the two groups (Figure 1D). Furthermore, treatment with AAV9-U1-FD had no effect on survival in control mice, indicating that the modified U1 has no obvious toxic effect. Body weight was significantly lower in FD mice than in control and was not affected by treatment (Figure S1). This suggests that the smaller size of FD mice is linked to a defect that occurs during the embryonic period and that early therapeutic intervention should be performed to recover this parameter.

Figure 1.

AAV9-U1-FD treatment (i.c.v. + i.p.) rescues life span in FD mice

(A and B) Endpoint gels (A) and relative quantification histograms (B) of ELP1 splicing isoforms in the TgFD9 asymptomatic mice treated with saline (lane 1) versus treatment with AAV9-U1-FD: intracerebral ventricular (i.c.v.) injected (lane 2), intraperitoneal (i.p.) injected (lane 3), and i.c.v. + i.p. injected (lane 4) at PND-10. Data are expressed as percentage of exon 20 inclusion. DRG, dorsal root ganglia; TG, trigeminal ganglia; SC, spinal cord. In the graph, data are reported as mean ± SEM, for each pair of animals tested. The upper band of 202 bp represents the ELP1 isoform in which exon 20 is included whereas the lower band of 128 bp represents the isoform in which exon 20 is skipped. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

(C) qPCR quantification of ExSpeU1-FD in the TgFD9 asymptomatic mice treated with saline (lane 1) versus treatment with AAV9-U1-FD: intracerebral ventricular (i.c.v.) injected (lane 2), intraperitoneal (i.p.) injected (lane 3), and i.c.v. + i.p. injected (lane 4) at PND-10. Data (mean ± SEM) are expressed as percentage of ExSpeU1-FD relative to endogenous U1, two technical replicates on 2 mice per group were used. DRG, dorsal root ganglia. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

(D) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of FD mice (IkbkapΔ20/Ikbkapflox; h-TgFD9/+) and littermate controls (Ikbkapflox/+; h-TgFD9/+) treated with one intracerebral ventricular injection (i.c.v.) at PND-0 and a second intraperitoneal injection (i.p.) at PND-2 of AAV9-U1-FD (1.6 × 1011 VG/mouse) or saline only. Littermate controls + saline in black; littermate controls + AAV9-U1-FD in gray; FD + saline in orange; FD-treated with AAV9-U1-FD in blue. Statistical analysis was performed with log-rank test, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, n > 15 mice for each group.

AAV9-U1-FD rescues ELP1 exon 20 inclusion and ELP1 accumulation in the FD mouse

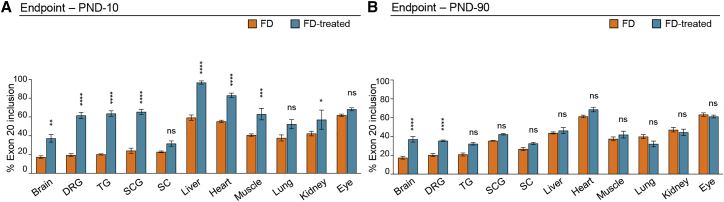

To evaluate the molecular events underlying the improved lifespan of AAV9-U1-FD treated FD-mice, we analyzed ELP1 splicing by end-point RT-PCR. At PND-10, U1-FD induced a significant rescue of exon 20 inclusion in several tissues (Figures 2A and S2A). A significant correction in ELP1 splicing was observed in dorsal root ganglia, trigeminal ganglia, and superior cervical ganglia. In untreated animals, these ganglia, consistently with the peripheral nervous system pathology observed in FD, have low exon 20 inclusion (<20%). Notably, in mice treated with AAV9-U1-FD, the percentage of exon 20 inclusion increases to approximately 60%. A significant splicing improvement was also evident in brain (from ∼15% to ∼40%), liver (from ∼60% to ∼100%), heart (from ∼55% to ∼85%), muscle (from ∼40% to ∼60%), and kidney (from ∼40% to ∼60%, with some individual variability), while no changes were observed in the eye, spinal cord, or lung. To evaluate the long-term effects of the treatment, we analyzed treated and untreated FD mice at PND-90 (Figures 2B and S2B). The recovery of splicing was still evident and significant in the brain and dorsal root ganglia, two of the key tissues affected by the disease. The other tissues had less splicing correction, possibly due to a dilution of the AAV during postnatal development. To clarify whether the reduction in splicing correction at 3 months of age could be due to the dilution of the AAV, we measured the amount of FD-ExSpeU1 RNA at PND-10 and PND-90 by qPCR in four representative tissues (brain, dorsal root ganglia, heart, and liver). After 3 months, brain maintains an efficient splicing rescue, dorsal root ganglia reduce in part the splicing rescue, whereas heart and liver return to PND-10 levels (Figure 2). We observed no significant age-dependent changes in FD-ExSpeU1 RNA in the brain and dorsal root ganglia, an approximately 4-fold reduction in the heart, and severe liver decline (Figure S2C). Even if the age-dependent correlation between the splicing and the FD-ExSpeU1 RNA levels is not complete, these results suggest that the reduction in the FD-ExSpeU1 RNA levels possibly due to AAV dilution are involved in the observed age-dependent effects.

Figure 2.

Tissue-specific ELP1 splicing rescue in FD mice

(A and B) Endpoint PCR histograms of ELP1 splicing isoforms in FD animals (IkbkapΔ20/Ikbkapflox; h-TgFD9/+) treated with saline (in orange) and AAV9-U1-FD (in blue) at PND-10 and PND-90, respectively, in (A) and in (B). Data are expressed as percentage of exon 20 inclusion. DRG, dorsal root ganglia; TG, trigeminal ganglia; SCG, superior cervical ganglia; SC, spinal cord. In the graph, data are reported as mean ± SEM, for each group 5 animals were tested (except for SCG and TG in which 3 animals per group were tested). Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA. Asterisks indicate the comparison for the saline group versus treated group in FD mice. ns, not significant; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

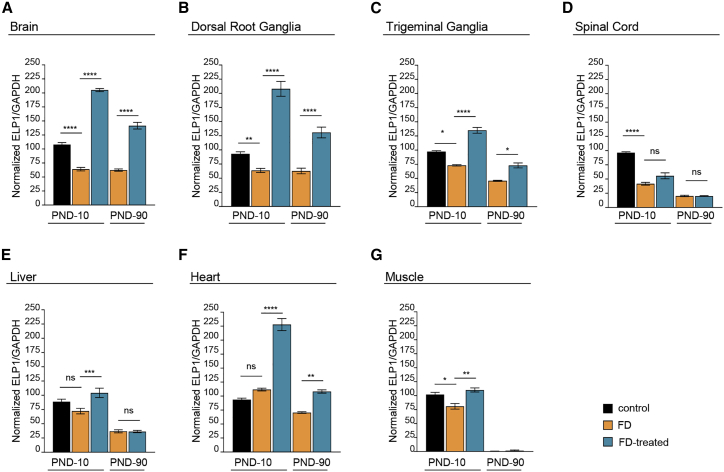

Next, we analyzed whether the correction of ELP1 exon 20 splicing led to an increase in protein. We compared ELP1 quantities between treated and untreated FD mice at PND-10 and PND-90. An untreated healthy control group, carrying one copy of the mouse Elp1 and one copy of the defective human transgene, was included in the analysis to establish the rescue efficiency of the protein compared to an asymptomatic mouse. At PND-10, FD-vehicle mice had a reduced amount of ELP1 in most tissues except for liver and heart, when compared with control mice. FD mice treated with AAV9-U1-FD had significantly more ELP1 at PND-10 than untreated FD mice, in brain, dorsal root ganglia, trigeminal ganglia, liver, muscle, and heart. In the brain, dorsal root ganglia, and heart, ELP1 was twice as abundant as in control mice (Figures 3 and S3). This slight 2-fold accumulation is likely due to the underestimation of the amount of the ELP1 in the asymptomatic control animal since it has only one normal mouse Elp1 allele along with a copy of the defective human ELP1 transgene. Importantly, the ELP1 improvement was maintained after 3 months in most of the tissues, except liver (Figures 3 and S3). In this tissue, the lack of long-term efficacy was expected due to the injection in the neonatal period and the consequent AAV dilution.73

Figure 3.

AAV9-U1-FD treatment rescues ELP1 levels in FD mice

Quantification of ELP1 levels in control mice (Ikbkapflox/+; h-TgFD9/+; black columns), FD mice (IkbkapΔ20/Ikbkapflox; h-TgFD9/+; orange columns), and FD mice treated with AAV9-U1-FD (IkbkapΔ20/Ikbkapflox; h-TgFD9/+; blue columns) at two different time points, PND-10 and PND-90, in different tissues: (A) brain, (B) dorsal root ganglia, (C) trigeminal ganglia, (D) spinal cord, (E) liver, (F) heart, (G) muscle. GAPDH was used as internal reference control. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; 3 mice for each group were tested, except for controls and trigeminal ganglia groups in which 2 animals were analyzed. Western blots used for quantitative analysis are shown in Figure S3. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. ns, not significant; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

In the FD mice, AAV9-U1-FD rescues creatinine levels, cardiac output, and motor/proprioceptive functions

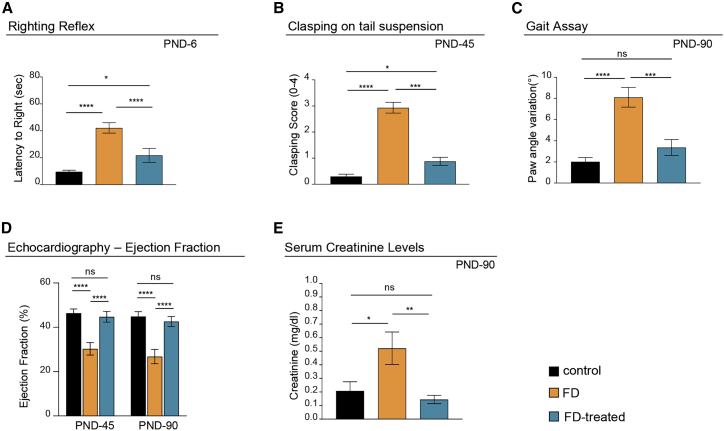

To evaluate the phenotypic improvement associated with life span rescue and increased ELP1 splicing and protein accumulation, we performed functional tests on gait, righting reflex, and clasping on tail suspension. These tests evaluate the motor/proprioceptive functions and ataxic gait at different ages.74,75 In early neonatal ages, at PND-6, FD mice had significantly impaired righting reflex (Figure 4A). Latency of FD mice to righting was four times longer than unaffected controls (40 versus 10 s). The AAV9-U1-FD treatment partly rescued the righting reflex (20 s), indicating that the treatment causes a significant improvement in the motor/proprioceptive activities just a few days after the injections. This early effect is due to the self-complementary AAV9 vector, which is known to rapidly express transgenes, and is consistent with the improvement of ELP1 splicing and protein accumulation observed at PND-10 (Figures 2 and 3). Clasping on tail suspension at PND-45 was significantly reduced in the FD mice, and this parameter was significantly improved by the AAV9-U1-FD treatment (Figure 4B). At PND-90, FD mice were also a significant poorer in performing the gait assay. This assay evaluates the paw angle variation between fore and hind paws during walking, and it is a clear indication that these mice develop an ataxic gait. In particular, FD mice treated with AAV9-U1-FD fully recover the ability to perform this test correctly in the same way as control mice (Figures 4C and S4A). We did not observe differences between control and FD-mice for accelerated automated rotarod and hanging tests (Figures S4B and S4C). As cardiovascular abnormalities are common in FD-affected individuals,76, 77, 78, 79, 80 we evaluated cardiac function by echocardiography. The FD mice at PND-45 and PND-90 had a severely reduced ejection fraction (from ∼45% in controls to ∼30%). The AAV9-U1-FD treatment completely rescued cardiac function in the FD mouse (Figure 4D). We also evaluated renal function, which is frequently compromised in FD,76,77,79 through serum creatinine levels.81 Serum creatinine levels were 2.5 times higher in FD mice compared to control littermates, and AAV9-U1-FD treatment normalized serum creatinine levels in FD-treated mice (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

AAV9-U1-FD rescues FD symptoms in FD mice

(A) The righting reflex test evaluates the latency to right at PND-6, n > 17 pups per group.

(B) Clasping on tail suspension gives the mean clasping score achieved by each genotype on a scale from 0 to 4 at PND-45, where 0 refers to wild-type behavior, linearly increasing to 4 which refers to highly impaired behavior, n > 10 mice per group.

(C) The gait assay test gives the paw angle variation between fore- and hind-paws during the walk at PND-90. The graph plots the final average of all tested animals in each group. n = 13 control, n = 12 FD, and n = 7 FD treated.

(D) Ejection fraction percentage (modified Simpson’s method) at PND-45 (n = 6 control, n = 3 FD, and n = 6 FD treated) and PND-90 (n = 8 control, n = 5 FD affected, and n = 8 FD treated).

(E) Creatinine levels measured in serum of PND-90 mice using an enzymatic assay (n = 10 mice per group). Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. Bars are SEM; ns, not significant; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. The tests were performed on littermate controls (Ikbkapflox/+; h-TgFD9/+) and FD mice (IkbkapΔ20/Ikbkapflox; h-TgFD9/+) treated with one intracerebral ventricular injection (i.c.v.) at PND-0 and a second intraperitoneal injection (i.p.) at PND-2 of AAV9-U1-FD (1.6 × 1011 VG/mouse) or saline only. Littermate controls + saline are in black; FD mice + saline in orange; FD mice treated with AAV9-U1-FD in blue.

U1-FD has few off-target effects in the human transcriptome or mouse dorsal root ganglia

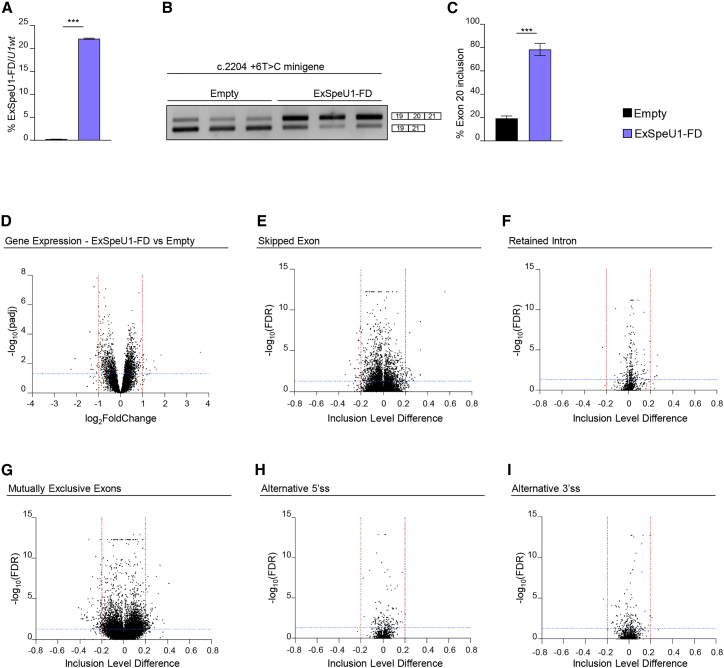

To evaluate whether the presence of U1-FD off-target pre-mRNA binding sites could result in detrimental changes in gene expression and/or alternative splicing, we tested the transcriptome changes in non ELP1-deficient cells of human origin and in mouse dorsal root ganglia after treatment. We have created stable HEK293 Flp-In T-REx clones that contain three integrated copies of ExSpeU1FD at the same chromosomal location. This resulted in expression of the U1-FD (∼20% compared to endogenous U1) and this improved the minigene ELP1 exon 20 splicing pattern (Figures 5A–5C). This relatively high U1-FD expression was well tolerated, and we found only 39 differentially expressed genes (padj ≤ 0.05, log2 fold change ≤−1 or ≥1) (Figure 5D and Table S1). Testing the differentially expressed genes with Qiagen’s Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) did not reveal any significant pathway involvement (Table S1). Analysis of the differentially alternative splicing events identified 51 events out of 101,518 transcripts (0.05%) for skipped exons (SE), 197 events out of 37,465 (0.5%) mutually exclusive exons (MXE), and very few events in retained introns (RI) (n = 5), alternative 5′ (A5SS) or 3′ (A3SS) splice sites (n = 1 and 2, respectively) (Figures 5E–5I and S5 and Table S1).

Figure 5.

Lack of global effects of ExSpe-U1-FD on the human transcriptome

(A) ExSpe-U1-FD expression levels in HEK 293 Flp-In T-REx stable control cells (empty) (n = 6) and stable clone cell line expressing ExSpe-U1-FD (n = 6). Data are expressed as percentage of ExSpe-U1-FD relative to endogenous U1.

(B) Transfection experiment of ELP1 mutant (c.2204+6T>C) minigene in ExSpe-U1-FD stable clones and controls. The ELP1 exon 20 inclusion and exclusion bands are indicated.

(C) Quantification of the percentage of exon 20 inclusion in the ELP1 mutant (c.2204+6T>C) minigene transfection experiment shown in (B).

(D) Volcano plot showing global gene expression changes between controls (empty, n = 6) and ExSpe-U1-FD stable clones (n = 6). Horizontal blue line (padj <0.05) and vertical red lines (log2FoldChange ≤−1 or ≥1) indicate cut-off values and determine significant down- and up-regulated events, respectively.

(E–I) Volcano plots showing global alternative splicing changes in (E) skipped exon (SE), (F) retained intron (RI), (G) mutually exclusive exons (MXE), (H) alternative 5′ splice site (A5SS), and (I) alternative 3′ splice site (A3SS) categories between empty clones (n = 6) and ExSpe-U1-FD stable clones (n = 6). Horizontal blue line (FDR ≤ 0.05) and vertical red lines (inclusion level difference ≤−0.2 or ≥0.2) indicate cut-off values and determine significant events in each category. In (A) and (C), data are expressed as mean ± SD and statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t test (∗∗∗p < 0.001).

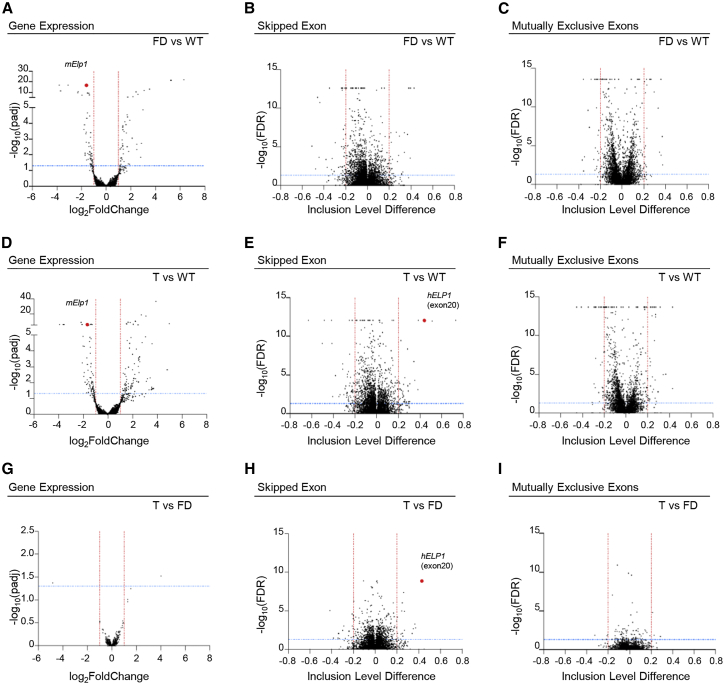

To uncover the molecular consequences of the treatment in vivo, we analyzed the transcriptomes of dorsal root ganglia in FD mice, FD treated (T) mice, and WT control mice at PND 10 and compared their gene expression and alternative splicing profiles. Comparison between FD and WT dorsal root ganglia identified 50 upregulated and 58 downregulated transcripts (padj ≤ 0.05, log2 fold change ≤−1 or ≥1), (Figures 6A and S6A and Table S2). Analysis of differentially expressed genes with Qiagen’s Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) showed involvement of not relevant pathways associated to hepatic fibrosis, atherosclerosis signaling, and ferroptosis signaling pathways (Table S2). Analysis of alternative splicing events identified 73 alternative exons (SE) (28 upregulated and 45 downregulated), 53 mutually exclusive exon events (MXE) (23 upregulated and 30 downregulated), and a few retained intron (RI) and alternative 5′ and 3′ ss (17, 3, and 8, respectively) (Figures 6B, 6C, S6, and S7 and Table S3). Treatment with AAV9-U1-FD (T vs WT) had a minor impact on the mouse transcriptome on differentially expressed transcripts (DE) or alternative splicing events at PND-10 but confirmed the strong increase in inclusion of the target human ELP1 exon 20 (ΔΨ = 0.44) (Figure 6E, hELP1). IPA analysis of differentially expressed genes showed involvement of only the iron homeostasis signalling pathway (Table S2). Comparison between treated (T) and FD showed very few DE transcripts and alternative splicing events, with only two differentially expressed transcripts in treated animals and no pathway enrichment by IPA (Figures 6G–6I and Table S2). As the ELP1 complex can act both on transcription and translation, these results suggest a preferential effect of the ELP1-mediated rescue on the translational defect. However, the extremely low number of DE transcripts (n = 2), SE (n = 35), MXE (n = 8), and other alternative splicing events we have observed in the treated animals indicates that AAV9-U1-FD has no significant off-target effects in dorsal root ganglia (Figures 6G–6I, S6, and S7 and Tables S4 and S5). Interestingly, in the case of alternative exons, most of the off-target events are less significant than human ELP1 exon 20, further implying that off-target splicing effects are minimal (Figure 6H, hELP1). As most gene changes in DRG are not improved by ELP1 splicing correction, it is possible that the changes we observed are not specific ELP1-independent changes. Collectively, these results indicate that U1-FD delivery by AAV9 efficiently remedies FD mice and targets the transcriptome with high specificity in particular in dorsal root ganglia, promoting a robust inclusion of the ELP1 exon 20 without inducing unintended changes in gene expression or alternative splicing.

Figure 6.

Effects of AAV9-U1-FD in dorsal root ganglia in FD mice

Volcano plots showing (A, D, and G) differential gene expression changes, alternative splicing changes in (B, E, and H) skipped exon (SE), and (C, F, and I) mutually exclusive exons (MXE) categories at PND-10 in three groups, WT (h-TgFD9/+), FD (IkbkapΔ20/Ikbkapflox; h-TgFD9/+), and T (IkbkapΔ20/Ikbkapflox; h-TgFD9/+ treated with AAV9-ExSpe-U1-FD). In (A)–(C), FD mice are compared to WT mice (FD vs WT); in (D)–(F), T mice are compared to WT mice (T vs WT); in (G)–(I), T mice are compared to FD mice (T vs FD). In (A), (D), and (G), horizontal blue line (padj ≤ 0.05) and vertical red lines (log2FoldChange ≤−1 or ≥1) indicate cut-off values and determine significant down- and up-regulated events, respectively. In the remaining panels (B, C, E, F, H, and I), horizontal blue line (FDR ≤ 0.05) and vertical red lines (inclusion level difference ≤−0.2 or ≥0.2) indicate cut-off values and determine significant events in each category. In (A) and (D), the red dot represents murine Elp1; in (E) and (H), the red dot represents human ELP1 exon 20.

Discussion

Familial dysautonomia is a severe genetic neurological disease, without effective therapy, caused by a splicing defect that induces skipping of ELP1 exon 20. In this study, we demonstrate that a modified U1 snRNA corrects skipping of ELP1 exon 20 and substantially improves the FD phenotype in a symptomatic mouse model. The FD mouse, showing perinatal fragility; defects in the righting reflex, tail suspension, and gait; a reduced ejection fraction; and an increase in serum creatinine, represents an excellent animal model of the FD sensory and autonomic dysfunctions. Treatment in the early postnatal days with an AAV9-U1-FD corrects the ELP1 splicing and restores the levels of functional ELP1 in several tissues including brain and peripheral ganglia and almost completely obviates mortality in the first month of life. Furthermore, this treatment recovers pathological phenotypes related to motor/proprioceptive activities and cardiac and renal functions and has very few off-target effects on gene expression and alternative splicing in mouse dorsal root ganglia and human cells. The rescue of a severely affected FD animal model by AAV9-U1-FD indicates that AAV-delivered modified U1 snRNA likely represents an effective and safe therapeutic option to treat FD.

The AAV9-U1-FD we have developed here have interesting properties due to the combination of the already proved clinical efficacy and tissue-specific targeting of AAV vectors together with a transgene that codes for a small non-coding RNA that corrects splicing. These vectors have been safely administered intravenously for hepatic, muscle, and even systemic replacement or by intracranial, intramuscular, and intravitreal routes with sustained expression of the transgene, primarily in non-proliferating tissues.82

The optimal dosage and delivery route of the viral particle should be carefully evaluated for future clinical studies. In our experiments, the total delivered dose was about 8 × 1013 VG/kg (1.6 × 1011 VG/pup), which is comparable to the approved dosage of the AAV9-based systemic gene therapy for spinal muscular atrophy (e.g., Zolgensma 1.1 × 1014 VG/kg) (https://www.fda.gov/media/126109/download). However, high doses of protein-coding AAV have recently raised concerns for their potential toxicity particularly in dorsal root ganglia. Prolonged AAV9-mediated overexpression of the SMN transgene in mice results in aggregation of the expressed protein and neuronal toxicity with widespread transcriptome abnormalities in dorsal root ganglion neurons.83 Similarly, administration of AAV vectors coding to different transgenes to nonhuman primates via blood or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) has been shown to result in dorsal root ganglion pathology.84 Although the molecular explanation for this toxicity is not fully understood, several lines of evidence suggests that the toxicity is due to overexpression of the therapeutic gene product (i.e., protein),83,85 which will not be the case with modified U1 snRNAs. These small non-coding RNAs are not expected to induce significant cellular stress and, in fact, we did not observe large changes in expression or alternative splicing in the dorsal root ganglia of FD-treated mice (Figures 6, S6, and S7), nor in human FD-U1-overexpressing cells (Figures 5 and S5), nor a negative effect on survival on normal mice (Figure 1D). Furthermore, FD-U1 has the advantage of only correcting splicing in those cells expressing the target pre-mRNA, thus avoiding the accumulation and/or ectopic expression of ELP1. Evaluation of the effects of the AAV9-U1-FD delivery by IP and i.c.v. individually should be important in future studies to clarify the most effective therapeutic approach. In addition, exploration of other administration routes could be particularly effective to prevent specific aspects of the disease progression such as age-dependent retinal ganglion cells dysfunction that is observed in FD-affected individuals7,86, 87, 88 and also in the FD mice.89 Considering the success of AAV-based therapies for the treatment of ocular disorders,82,90 appropriate adeno-associated virus serotypes could be used to deliver U1-FD by intravitreal injection to specifically target the degeneration of these cells and treat the progressive visual decline.

Since hybridization of the U1 RNA to complementary target sequences may have off-target effects due to unintended binding to RNAs, we performed RNA-seq analysis in human cells and in dorsal root ganglia from treated mice at early ages. In both cases, we observed only minimal changes in global gene expression and splicing caused by the U1-FD expression. Thus, U1-FD is shown to have a high specificity for the intended ELP1 pre-mRNA with no significant off-target effects on the human transcriptome. Similarly, a modified U1 that corrects the SMN2 splicing defect in spinal muscular atrophy showed a low level of off-target effects,58 indicating a more general applicability of the strategy. However, as the FD-ExSpeU1 RNA levels are maintained in the dorsal root ganglia at later time points (PND-90) (Figure S2C), potential long-term off-target effects cannot be excluded. Rescue of the ELP1 in the dorsal root ganglia of treated FD mice at PND-10 did not substantially change the transcriptome profile (Figure 6). As the ELP1 complex has been shown to act both on transcription21,23,26,27 and translation,31,32 it is possible that in this tissue at this developmental stage most of the therapeutic effect of AAV9-U1-FD is on translation. Indeed, analysis of published transcriptome changes in a different mouse model with the selective ablation of the Elp1 in DRG showed a similar low number of changes in the transcriptome profile (Figure S8).32 However, more detailed studies comparing proteomic and transcriptome data at different ages are needed to elucidate the underlying rescue mechanism in detail.

Several other promising therapeutic strategies for ELP1 splicing correction are being actively investigated including small molecules (SMCs)42, 43, 44, 45 and antisense oligonucleotides (ASO).41 SMCs are attractive because they can be optimized for broad tissue distribution and are orally administered but the available compounds need additional chemistry optimization in order to increase the potency, reduce the potential for off-target effects, or improve the bioavailability.42, 43, 44 Following the successful Nusinersen (Spinraza) approach for spinal muscular atrophy, promising ELP1-specific ASOs has also been developed for FD41 but their efficacy was not assessed in the symptomatic FD mouse model nor their potential off-target effects nor bioavailability at target tissues. AAV9-U1-FD has the advantage of exhibiting a very limited number of off-target effects and potentially providing long-lasting splicing correction in most target tissues when administered systemically or intrathecally. However, in common with other AAV-based therapies, it may undergo dilution in replicating tissues73 and, due to the presence of neutralizing antibodies against the viral capsid, it may show reduced efficacy in subsequent treatments.91,92 The tailored combination of complementary strategies could be used to obtain an optimal therapeutic efficacy for a splicing precision medicine.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that U1-FD, a modified U1 snRNA, delivered by AAV9 vectors, efficiently corrects the ELP1 splicing and protein defects in the FD phenotypic mouse model, rescuing its motor, cardiac, and renal dysfunctions, and ultimately reducing animal mortality. The extent of phenotypic improvements induced by systemic treatment of AAV9-U1-FD, along with the lack of significant off-target effects, are promising for the application of AAV9-U1-FD in the clinic.

Acknowledgments

We thank Horacio Kaufmann of the Dysautonomia Treatment and Evaluation Centre at New York University Medical School for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institute of Health (NIH) grant (R01EY029544 to S.A.S. and F.P.) and a grant from Telethon Foundation (GGP17006 to F.P.).

Author contributions

F.P. and G. Romano conceived and designed the research. D.L. and F.R. performed the in silico analyses. G. Romano and E.B. performed the experiments. S.A.S. and E.M. provided the mouse model. I.R. and G. Ronzitti prepared the AAVs. S.V. and G. Romano performed the echocardiography. G. Romano and F.P wrote the original manuscript, which was reviewed and edited by all authors. F.P. supervised the research.

Declaration of interests

F.P. is listed as inventor of the U.S. patent n. 9,669,109 “A modified human U1snRNA molecule, a gene encoding for the modified human U1snRNA molecule, an expression vector including the gene, and the use thereof in gene therapy of familial dysautonomia and spinal muscular atrophy.” As such, the inventors could potentially benefit from any future commercial exploitation of patent rights, including the use of ExSpeU1s in FD. S.A.S. is a paid consultant to PTC Therapeutics and is an inventor on several U.S. and foreign patents and patent applications assigned to the Massachusetts General Hospital, including U.S. Patents 8,729,025 and 9,265,766, both entitled “Methods for altering mRNA splicing and treating familial dysautonomia by administering benzyladenine,” filed on August 31, 2012 and May 19, 2014 and related to use of kinetin; and U.S. Patent 10,675,475 entitled, “Compounds for improving mRNA splicing” filed on July 14, 2017 and related to use of BPN-15477. E.M. and S.A.S. are inventors on an International Patent Application Number PCT/US2021/012,103, assigned to Massachusetts General Hospital and entitled “RNA Splicing Modulation” related to use of BPN-15477 in modulating splicing.

Published: July 28, 2022

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2022.07.004.

Supplemental information

Summary (sheet1); list of the significant candidates of the differential gene expression (sheet 2) and Ingenuity Pathway analysis (sheet 3). Alternative splicing events analysis (Skipped Exon, sheet 4; Retained Intron, sheet 5; Mutually Exclusive Exons, sheet 6; Alternative 5’ splice site, sheet 7; Alternative 3’ splice site, sheet 8) in HEK293 Flp-In-T-Rex cell line. ExSpeU1-FD vs control clones.

Summary (sheet 1); list of the significant candidates of the differential gene expression in dorsal root ganglia of FD mice vs control (WT) (sheet 2), treated (T) vs WT (sheet 3) and T vs FD (sheet 4). Ingenuity Pathway analysis on DGE of FD vs WT (sheet 5) and T vs WT (sheet 6). Mice at PND 10.

Summary, sheet 1; Skipped Exon, sheet 2; Retained Intron, sheet 3; Mutually Exclusive Exons, sheet 4; Alternative 5’ splice site, sheet 5; Alternative 3’ splice site, sheet 6.

Summary, sheet 1; Skipped Exon, sheet 2; Retained Intron, sheet 3; Mutually Exclusive Exons, sheet 4; Alternative 5’ splice site, sheet 5; Alternative 3’ splice site, sheet 6.

Summary, sheet 1; Skipped Exon, sheet 2; Retained Intron, sheet 3; Mutually Exclusive Exons, sheet 4; Alternative 5’ splice site, sheet 5; Alternative 3’ splice site, sheet 6.

Data and code availability

All sequencing data from RNA-seq experiments have been deposited in Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under Bioproject number PRJNA797221 and PRJNA782183.

References

- 1.Norcliffe-Kaufmann L., Slaugenhaupt S.A., Kaufmann H. Familial dysautonomia: history, genotype, phenotype and translational research. Prog. Neurobiol. 2017;152:131–148. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maayan C., Kaplan E., Shachar S., Peleg O., Godfrey S. Incidence of familial dysautonomia in Israel 1977-1981. Clin. Genet. 1987;32:106–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1987.tb03334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riley C.M., Day R.L., Greeley D.M., Langford W.S. Central autonomic dysfunction with defective lacrimation: I. Report of Five Cases. Pediatrics. 1949;3:468–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong J., Edelmann L., Bajwa A.M., Kornreich R., Desnick R.J. Familial dysautonomia: detection of the IKBKAP IVS20(+6T--> C) and R696P mutations and frequencies among ashkenazi jews. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2002;110:253–257. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Axelrod F.B., Pearson J. Congenital sensory neuropathies: diagnostic distinction from familial dysautonomia. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1984;138:947–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunt P.W., Mckusick V.A. Familial Dysautonomia: a report of genetic and clinical studies, with a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltim.) 1970;49:343–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendoza-Santiesteban C.E., Palma J.-A., Hedges T.R., Laver N.V., Farhat N., Norcliffe-Kaufmann L., Kaufmann H. Pathological Confirmation of optic neuropathy in familial dysautonomia. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2017;76:238–244. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlw118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gold-von Simson G., Axelrod F.B. Familial dysautonomia: update and recent advances. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care. 2006;36:218–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norcliffe-Kaufmann L., Martinez J., Axelrod F., Kaufmann H. Hyperdopaminergic crises in familial dysautonomia: a randomized trial of carbidopa. Neurology. 2013;80:1611–1617. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828f18f0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norcliffe-Kaufmann L., Palma J.-A., Martinez J., Kaufmann H. Carbidopa for afferent baroreflex failure in familial dysautonomia: a double-blind randomized crossover clinical trial. Hypertens. Dallas Tex. 2020;1979:724–731. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palma J.-A., Kaufmann L., Fuente C., Percival L., Mendoza C., Kaufmann H. Current treatments in familial dysautonomia. Expert opin. Pharmacother. 2014;15:2653–2671. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2014.970530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson S.L., Coli R., Daly I.W., Kichula E.A., Rork M.J., Volpi S.A., Ekstein J., Rubin B.Y. Familial dysautonomia is caused by mutations of the IKAP gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;68:753–758. doi: 10.1086/318808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slaugenhaupt S.A., Blumenfeld A., Gill S.P., Leyne M., Mull J., Cuajungco M.P., Liebert C.B., Chadwick B., Idelson M., Reznik L., et al. Tissue-specific expression of a splicing mutation in the IKBKAP gene causes familial dysautonomia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;68:598–605. doi: 10.1086/318810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blumenfeld A., Slaugenhaupt S.A., Axelrod F.B., Lucente D.E., Maayan C., Liebert C.B., Ozelius L.J., Trofatter J.A., Haines J.L., Breakefield X.O., et al. Localization of the gene for familial dysautonomia on chromosome 9 and definition of DNA markers for genetic diagnosis. Nat. Genet. 1993;4:160–164. doi: 10.1038/ng0693-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leyne M., Mull J., Gill S.P., Cuajungco M.P., Oddoux C., Blumenfeld A., Maayan C., Gusella J.F., Axelrod F.B., Slaugenhaupt S.A. Identification of the first non-Jewish mutation in familial Dysautonomia. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2003;118A:305–308. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boone N., Loriod B., Bergon A., Sbai O., Formisano-Tréziny C., Gabert J., Khrestchatisky M., Nguyen C., Féron F., Axelrod F.B., Ibrahim E.C. Olfactory stem cells, a new cellular model for studying molecular mechanisms underlying familial dysautonomia. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuajungco M.P., Leyne M., Mull J., Gill S.P., Lu W., Zagzag D., Axelrod F.B., Maayan C., Gusella J.F., Slaugenhaupt S.A. Tissue-specific reduction in splicing efficiency of IKBKAP due to the major mutation associated with familial dysautonomia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:749–758. doi: 10.1086/368263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hims M.M., Shetty R.S., Pickel J., Mull J., Leyne M., Liu L., Gusella J.F., Slaugenhaupt S.A. A humanized IKBKAP transgenic mouse models a tissue-specific human splicing defect. Genomics. 2007;90:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Creppe C., Malinouskaya L., Volvert M.-L., Gillard M., Close P., Malaise O., Laguesse S., Cornez I., Rahmouni S., Ormenese S., et al. Elongator controls the migration and differentiation of cortical neurons through acetylation of α-tubulin. Cell. 2009;136:551–564. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glatt S., Müller C.W. Structural insights into Elongator function. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2013;23:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J.-H., Lane W.S., Reinberg D. Human Elongator facilitates RNA polymerase II transcription through chromatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:1241–1246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251672198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohlen S.B., Russell M.L., Brownstein M.J., Lefcort F. BGP-15 prevents the death of neurons in a mouse model of familial dysautonomia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:5035–5040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620212114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otero G., Fellows J., Li Y., de Bizemont T., Dirac A.M., Gustafsson C.M., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Svejstrup J.Q. Elongator. Mol. Cell. 1999;3:109–118. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solinger J.A., Paolinelli R., Klöss H., Scorza F.B., Marchesi S., Sauder U., Mitsushima D., Capuani F., Stürzenbaum S.R., Cassata G. The Caenorhabditis elegans elongator complex regulates neuronal α-tubulin acetylation. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ueki Y., Shchepetkina V., Lefcort F. Retina-specific loss of Ikbkap/Elp1 causes mitochondrial dysfunction that leads to selective retinal ganglion cell degeneration in a mouse model of familial dysautonomia. Dis. Model. Mech. 2018;11:dmm033746. doi: 10.1242/dmm.033746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Close P., Hawkes N., Cornez I., Creppe C., Lambert C.A., Rogister B., Siebenlist U., Merville M.-P., Slaugenhaupt S.A., Bours V., et al. Transcription impairment and cell migration defects in elongator-depleted cells: implication for familial dysautonomia. Mol. Cell. 2006;22:521–531. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hawkes N.A., Otero G., Winkler G.S., Marshall N., Dahmus M.E., Krappmann D., Scheidereit C., Thomas C.L., Schiavo G., Erdjument-Bromage H., et al. Purification and Characterization of the human elongator complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:3047–3052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110445200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morini E., Gao D., Logan E.M., Salani M., Krauson A.J., Chekuri A., Chen Y.-T., Ragavendran A., Chakravarty P., Erdin S., et al. Developmental regulation of neuronal gene expression by Elongator complex protein 1 dosage. J. Genet. Genomics. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2021.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang B., Johansson M.J.O., Byström A.S. An early step in wobble uridine tRNA modification requires the Elongator complex. RNA. 2005;11:424–436. doi: 10.1261/rna.7247705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang B., Lu J., Byström A.S. A genome-wide screen identifies genes required for formation of the wobble nucleoside 5-methoxycarbonylmethyl-2-thiouridine in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. RNA. 2008;14:2183–2194. doi: 10.1261/rna.1184108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karlsborn T., Tükenmez H., Chen C., Byström A.S. Familial dysautonomia (FD) patients have reduced levels of the modified wobble nucleoside mcm5s2U in tRNA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014;454:441–445. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.10.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goffena J., Lefcort F., Zhang Y., Lehrmann E., Chaverra M., Felig J., Walters J., Buksch R., Becker K.G., George L. Elongator and codon bias regulate protein levels in mammalian peripheral neurons. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:889. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03221-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cuajungco M.P., Leyne M., Mull J., Gill S.P., Gusella J.F., Slaugenhaupt S.A. Cloning, characterization, and genomic Structure of the mouse Ikbkap gene. DNA Cell Biol. 2001;20:579–586. doi: 10.1089/104454901317094990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bochner R., Ziv Y., Zeevi D., Donyo M., Abraham L., Ashery-Padan R., Ast G. Phosphatidylserine increases IKBKAP levels in a humanized knock-in IKBKAP mouse model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013;22:2785–2794. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dietrich P., Yue J., Shuyu E., Dragatsis I. Deletion of exon 20 of the familial dysautonomia gene Ikbkap in mice causes developmental delay, cardiovascular defects, and early embryonic lethality. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dietrich P., Alli S., Shanmugasundaram R., Dragatsis I. IKAP expression levels modulate disease severity in a mouse model of familial dysautonomia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:5078–5090. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.George L., Chaverra M., Wolfe L., Thorne J., Close-Davis M., Eibs A., Riojas V., Grindeland A., Orr M., Carlson G.A., Lefcort F. Familial dysautonomia model reveals Ikbkap deletion causes apoptosis of Pax3+ progenitors and peripheral neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:18698–18703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308596110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jackson M.Z., Gruner K.A., Qin C., Tourtellotte W.G. A neuron autonomous role for the familial dysautonomia gene ELP1 in sympathetic and sensory target tissue innervation. Development. 2014;141:2452–2461. doi: 10.1242/dev.107797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lefcort F., Mergy M., Ohlen S.B., Ueki Y., George L. Animal and cellular models of familial dysautonomia. Clin. Auton. Res. Off. J. Clin. Auton. Res. 2017;27:235–243. doi: 10.1007/s10286-017-0438-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morini E., Dietrich P., Salani M., Downs H.M., Wojtkiewicz G.R., Alli S., Brenner A., Nilbratt M., LeClair J.W., Oaklander A.L., et al. Sensory and autonomic deficits in a new humanized mouse model of familial dysautonomia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016;25:1116–1128. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sinha R., Kim Y.J., Nomakuchi T., Sahashi K., Hua Y., Rigo F., Bennett C.F., Krainer A.R. Antisense oligonucleotides correct the familial dysautonomia splicing defect in IKBKAP transgenic mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:4833–4844. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ajiro M., Awaya T., Kim Y.J., Iida K., Denawa M., Tanaka N., Kurosawa R., Matsushima S., Shibata S., Sakamoto T., et al. Therapeutic manipulation of IKBKAP mis-splicing with a small molecule to cure familial dysautonomia. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:4507. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24705-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao D., Morini E., Salani M., Krauson A.J., Chekuri A., Sharma N., Ragavendran A., Erdin S., Logan E.M., Li W., et al. A deep learning approach to identify gene targets of a therapeutic for human splicing disorders. Nat. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:3332. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23663-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morini E., Gao D., Montgomery C.M., Salani M., Mazzasette C., Krussig T.A., Swain B., Dietrich P., Narasimhan J., Gabbeta V., et al. ELP1 splicing correction reverses proprioceptive sensory loss in familial dysautonomia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019;104:638–650. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Slaugenhaupt S.A., Mull J., Leyne M., Cuajungco M.P., Gill S.P., Hims M.M., Quintero F., Axelrod F.B., Gusella J.F. Rescue of a human mRNA splicing defect by the plant cytokinin kinetin. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004;13:429–436. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Donadon I., Pinotti M., Rajkowska K., Pianigiani G., Barbon E., Morini E., Motaln H., Rogelj B., Mingozzi F., Slaugenhaupt S.A., Pagani F. Exon-specific U1 snRNAs improve ELP1 exon 20 definition and rescue ELP1 protein expression in a familial dysautonomia mouse model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018;27:2466–2476. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Axelrod F.B., Liebes L., Gold-von Simson G., Mendoza S., Mull J., Leyne M., Norcliffe-Kaufmann L., Kaufmann H., Slaugenhaupt S.A. Kinetin improves IKBKAP mRNA splicing in patients with familial dysautonomia. Pediatr. Res. 2011;70:480–483. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31822e1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gold-von Simson G., Goldberg J.D., Rolnitzky L.M., Mull J., Leyne M., Voustianiouk A., Slaugenhaupt S.A., Axelrod F.B. Kinetin in familial dysautonomia carriers: implications for a new therapeutic strategy targeting mRNA splicing. Pediatr. Res. 2009;65:341–346. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318194fd52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rogalska M.E., Tajnik M., Licastro D., Bussani E., Camparini L., Mattioli C., Pagani F. Therapeutic activity of modified U1 core spliceosomal particles. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11168. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dal Mas A., Fortugno P., Donadon I., Levati L., Castiglia D., Pagani F. Exon-specific U1s correct SPINK5 exon 11 skipping caused by a synonymous substitution that affects a bifunctional splicing regulatory element. Hum. Hum. Mutat. 2015;36:504–512. doi: 10.1002/humu.22762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fernandez Alanis E., Pinotti M., Dal Mas A., Balestra D., Cavallari N., Rogalska M.E., Bernardi F., Pagani F. An exon-specific U1 small nuclear RNA (snRNA) strategy to correct splicing defects. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:2389–2398. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nizzardo M., Simone C., Dametti S., Salani S., Ulzi G., Pagliarani S., Rizzo F., Frattini E., Pagani F., Bresolin N., et al. Spinal muscular atrophy phenotype is ameliorated in human motor neurons by SMN increase via different novel RNA therapeutic approaches. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:11746. doi: 10.1038/srep11746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tajnik M., Rogalska M.E., Bussani E., Barbon E., Balestra D., Pinotti M., Pagani F. Molecular basis and therapeutic strategies to rescue factor IX Variants that affect splicing and protein function. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1006082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Balestra D., Faella A., Margaritis P., Cavallari N., Pagani F., Bernardi F., Arruda V.R., Pinotti M. An engineered U1 small nuclear RNA rescues splicing-defective coagulation F7 gene expression in mice. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2014;12:177–185. doi: 10.1111/jth.12471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Balestra D., Scalet D., Pagani F., Rogalska M.E., Mari R., Bernardi F., Pinotti M. An exon-specific U1snRNA induces a robust factor IX activity in mice expressing multiple human FIX splicing mutants. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2016;5:e370. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2016.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dal Mas A., Rogalska M.E., Bussani E., Pagani F. Improvement of SMN2 pre-mRNA processing mediated by exon-specific U1 small nuclear RNA. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;96:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martín E., Vivori C., Rogalska M., Herrero-Vicente J., Valcárcel J. Alternative splicing regulation of cell-cycle genes by SPF45/SR140/CHERP complex controls cell proliferation. RNA. 2021;27:1557–1576. doi: 10.1261/rna.078935.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Donadon I., Bussani E., Riccardi F., Licastro D., Romano G., Pianigiani G., Pinotti M., Konstantinova P., Evers M., Lin S., et al. Rescue of spinal muscular atrophy mouse models with AAV9-Exon-specific U1 snRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:7618–7632. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ayuso E., Mingozzi F., Montane J., Leon X., Anguela X.M., Haurigot V., Edmonson S.A., Africa L., Zhou S., High K.A., et al. High AAV vector purity results in serotype- and tissue-independent enhancement of transduction efficiency. Gene Ther. 2010;17:503–510. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Feather-Schussler D.N., Ferguson T.S. A battery of motor tests in a neonatal mouse model of cerebral palsy. J. Vis. Exp. 2016:53569. doi: 10.3791/53569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miedel C.J., Patton J.M., Miedel A.N., Miedel E.S., Levenson J.M. Assessment of Spontaneous Alternation, Novel Object Recognition and Limb Clasping in Transgenic Mouse Models of Amyloid-β and Tau Neuropathology. J. Vis. Exp. 2017:e55523. doi: 10.3791/55523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Klapdor K., Dulfer B.G., Hammann A., Van der Staay F.J. A low-cost method to analyse footprint patterns. J. Neurosci. Methods. 1997;75:49–54. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(97)00042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Clarke K.A., Still J. Gait analysis in the mouse. Physiol. Behav. 1999;66:723–729. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Putten M., Aartsma-Rus A., Putker K., Overzier M., Adamzek W.A., Pasteuning-Vuhman S., Plomp J.J., Aartsma-Rus A. Natural disease history of the D2-mdx mouse model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. FASEB J. 2019;33:8110–8124. doi: 10.1096/fj.201802488R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Parasuraman S., Raveendran R., Kesavan R. Blood sample collection in small laboratory animals. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2010;1:87–93. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.72350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zacchigna S., Paldino A., Falcão-Pires I., Daskalopoulos E.P., Dal Ferro M., Vodret S., Lesizza P., Cannatà A., Miranda-Silva D., Lourenço A.P., et al. Towards standardization of echocardiography for the evaluation of left ventricular function in adult rodents: a position paper of the ESC Working Group on Myocardial Function. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021;117:43–59. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dobin A., Gingeras T.R. Mapping RNA-seq reads with STAR. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2015;51:11.14.1–11.14.19. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1114s51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Love M.I., Huber W., Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shen S., Park J.W., Lu Z.x., Lin L., Henry M.D., Wu Y.N., Zhou Q., Xing Y. rMATS: robust and flexible detection of differential alternative splicing from replicate RNA-Seq data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:E5593–E5601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419161111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Irimia M., Weatheritt R.J., Ellis J.D., Parikshak N.N., Gonatopoulos-Pournatzis T., Babor M., Quesnel-Vallières M., Tapial J., Raj B., O’Hanlon D., et al. A highly conserved program of neuronal microexons is misregulated in autistic brains. Cell. 2014;159:1511–1523. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Axelrod F.B., Gold-von Simson G. Hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathies: types II, III, and IV. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2007;2:39. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maurya S., Sarangi P., Jayandharan G.R. Safety of Adeno-associated virus-based vector-mediated gene therapy—impact of vector dose. Cancer Gene Ther. 2022:1–2. doi: 10.1038/s41417-021-00413-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bortolussi G., Zentillin L., Vaníkova J., Bockor L., Bellarosa C., Mancarella A., Vianello E., Tiribelli C., Giacca M., Vitek L., et al. Life-long correction of hyperbilirubinemia with a neonatal liver-specific AAV-mediated gene transfer in a lethal mouse model of Crigler-Najjar Syndrome. Hum. Gene Ther. 2014;25:844–855. doi: 10.1089/hum.2013.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.General Health . John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2007. In What’s Wrong With My Mouse? pp. 42–60. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Motor Functions . John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2007. In What’s Wrong with My mouse? pp. 62–84. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bencsik P., Gömöri K., Szabados T., Sántha P., Helyes Z., Jancsó G., Ferdinandy P., Görbe A. Myocardial ischaemia reperfusion injury and cardioprotection in the presence of sensory neuropathy: therapeutic options. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020;177:5336–5356. doi: 10.1111/bph.15021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Carroll M.S., Kenny A.S., Patwari P.P., Ramirez J.-M., Weese-Mayer D.E. Respiratory and cardiovascular indicators of autonomic nervous system dysregulation in familial dysautonomia. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2012;47:682–691. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Norcliffe-Kaufmann L., Axelrod F., Kaufmann H. Afferent baroreflex failure in familial dysautonomia. Neurology. 2010;75:1904–1911. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181feb283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Norcliffe-Kaufmann L., Axelrod F.B., Kaufmann H. Developmental abnormalities, blood pressure variability and renal disease in Riley Day syndrome. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2013;27:51–55. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2011.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Goldstein D.S., Eldadah B., Sharabi Y., Axelrod F.B. Cardiac sympathetic hypo-innervation in familial dysautonomia. Clin. Auton. Res. Off. J. Clin. Auton. Res. 2008;18:115–119. doi: 10.1007/s10286-008-0464-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stevens M., Oltean S. Assessment of kidney function in mouse models of Glomerular disease. J. Vis. Exp. 2018:57764. doi: 10.3791/57764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]