Abstract

Aims

In heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), excessive redistribution of blood volume into the central circulation leads to elevations of intracardiac pressures with exercise limitations. Splanchnic ablation for volume management (SAVM) has been proposed as a therapeutic intervention. Here we present preliminary safety and efficacy data from the initial roll‐in cohort of the REBALANCE‐HF trial.

Methods and results

The open‐label (roll‐in) arm of REBALANCE‐HF will enrol up to 30 patients, followed by the randomized, sham‐controlled portion of the trial (up to 80 additional patients). Patients with HF, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥50%, and invasive peak exercise pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) ≥25 mmHg underwent SAVM. Baseline and follow‐up assessments included resting and exercise PCWP, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), 6‐min walk test, and N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP). Efficacy and safety were assessed at 1 and 3 months. Here we report on the first 18 patients with HFpEF that have been enrolled into the roll‐in, open‐label arm of the study across nine centres; 14 (78%) female; 16 (89%) in NYHA class III; and median (interquartile range) age 75.2 (68.4–81) years, LVEF 61.0 (56.0–63.2)%, and average (standard deviation) 20 W exercise PCWP 36.4 (±8.6) mmHg. All 18 patients were successfully treated. Three non‐serious moderate device/procedure‐related adverse events were reported. At 1‐month, the mean PCWP at 20 W exercise decreased from 36.4 (±8.6) to 28.9 (±7.8) mmHg (p < 0.01), NYHA class improved by at least one class in 33% of patients (p = 0.02) and KCCQ score improved by 22.1 points (95% confidence interval 9.4–34.2) (p < 0.01).

Conclusion

The preliminary open‐label results from the multicentre REBALANCE‐HF roll‐in cohort support the safety and efficacy of SAVM in HFpEF. The findings require confirmation in the ongoing randomized, sham‐controlled portion of the trial.

Keywords: Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, Splanchnic nerve ablation, Therapeutics, Clinical trial

Introduction

Elevated intra‐cardiac filling pressures at rest and specifically during activity cause exertional dyspnoea, impaired aerobic capacity, and are associated with increased mortality in patients with heart failure (HF) and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). 1 , 2 , 3 Accordingly, many cardiovascular therapies target reduction in intra‐cardiac filling pressures to improve exertional capacity, quality of life, and cardiovascular morbidity in patients with HFpEF. 4 The excessive distribution of blood volume from the extra‐thoracic compartments into the thorax is a central contributor to elevated filling pressures in HF patients. 4 , 5 A substantial proportion of the intravascular blood volume is located in the splanchnic vascular compartment. Preclinical and clinical investigations support the critical role of the sympathetic nervous system in modulating the capacitance and compliance of the splanchnic vascular bed via modulation of the greater splanchnic nerve (GSN). GSN stimulation induces an increase in cardiac preload and afterload with resultant cardiopulmonary pressure elevation. 6 , 7 , 8

The short‐term blockade of the GSN via anaesthetic agents demonstrated the feasibility, acute safety and efficacy of the intervention to reduce intracardiac pressures (HF with reduced ejection fraction [HFrEF], bilateral, n = 11, NCT03453151 9 and chronic HFrEF, bilateral and unilateral, n = 15, NCT02669407 10 ). Long‐term blockade of the GSN via surgical ablation in HFpEF (n = 11, NCT03715543) 11 extended these findings and supported the long‐term safety and persistent efficacy of the intervention out to 12 months. A novel, minimally invasive, endovascular, transvenous procedure was developed to ablate the right‐sided GSN (splanchnic ablation for volume management [SAVM] procedure), and has been shown to be beneficial in a small, single‐centre open‐label pilot trial. 12

The ongoing multicentre REBALANCE‐HF randomized, sham‐controlled trial is evaluating the novel SAVM treatment paradigm to determine whether it safely improves haemodynamics, health status (symptoms and quality of life), and exercise tolerance compared to sham control in patients with HFpEF. Here, we present preliminary safety and efficacy data from the initial roll‐in cohort of the REBALANCE‐HF trial.

Methods

The open‐label (roll‐in) arm of REBALANCE‐HF will enrol up to 30 patients, followed by the randomized, sham‐controlled portion of the trial (up to 80 additional patients). As part of the roll‐in cohort, individual sites were allowed to treat up to three patients in an unblinded fashion prior to commencing randomization of patients into the trial. These participants are not considered part of the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) population for the eventual randomized, sham‐controlled portion of the trial. Participants included in the roll‐in cohort underwent the same procedures and follow‐up as participants who are being enrolled in the ITT population trial, but with the exception of randomization; however, these participants will not be included in the analyses of the primary efficacy endpoint and acute procedural success data for the overall REBALANCE‐HF trial.

Eligible patients with chronic HFpEF (left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] ≥50%), with an elevated pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) at rest or exertion (≥25 mmHg) were required to meet clinical eligibility criteria and as well as qualifying haemodynamic selection criteria on the day of treatment (online supplementary Table S1 ). All patients were independently evaluated by a dedicated screening committee to confirm eligibility and optimal management of HFpEF with clinical stability for >30 days.

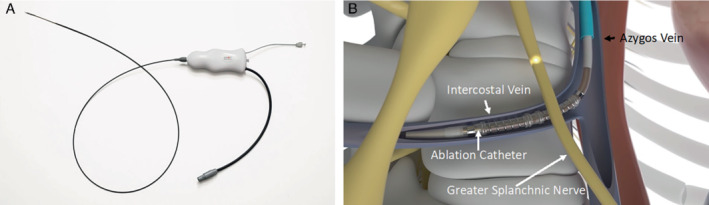

The right GSN was ablated via a transvenous SAVM procedure (Axon Therapies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) (Figure 1 ). 12 Using routine femoral venous access, the right GSN was approached from the right azygos vein and branching intercostal veins where the target nerve and veins cross at the 10th and 11th thoracic levels. The location of the ablation was determined based on anatomical landmarks using fluoroscopic imaging. The SAVM procedure delivers radiofrequency energy (≥90 s) and is continuously cooled by saline injection through the catheter at the ablation site. Baseline and follow‐up assessments included resting and exercise PCWP, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), 6‐min walk test (6MWT), and N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP). The primary efficacy endpoints were a reduction in PCWP at rest, legs up, and 20 W exercise at 1 month. The primary safety endpoint was serious device‐ or procedure‐related adverse events at 1 month (see online supplementary Tables S3 and S4 for a complete list of protocol‐defined potential procedure‐ and device‐related adverse events). Patient data before and at various time‐points after the SAVM procedure (1 and 3 months) were compared using Wilcoxon signed rank test (SAS v9.4 for Windows, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), exercise haemodynamics were compared between baseline and 1 month using a mixed model repeated measures analysis. Continuous variables within a visit are presented as median [Q1, Q3]. A p‐value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The trial was registered (NCT04592445). The REBALANCE‐HF trial is funded by Axon Therapies, Inc. The steering committee designed the protocol with the study sponsor.

Figure 1.

Splanchnic ablation for volume management (SAVM) system. (A) Ablation catheter. (B) Access to greater splanchnic nerve via venous system.

Results

To date, 18 patients with HFpEF across nine centres have been enrolled into the roll‐in portion of the study. Of them, 14 (78%) are female, mean age 74 ± 9 years, median [interquartile range] body mass index of 35.3 [27.6–37.2] kg/m2, 16 (89%) NYHA class III, and LVEF 61 [56–63]% (Table 1 ). All patients were successfully treated. Three non‐serious device‐related adverse events were reported, including acute HF decompensation due to high periprocedural intravenous volume use and diuretic withholding, transient hypertension during ablation procedure and back pain following ablation (online supplementary Table S2 ). All patients completed their follow‐up visits out to 3 months.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study cohort

| Patients, n | 18 |

| Age (years) | 75.2 (68.4–81) |

| Female sex | 78% |

| Race (Black/White) | 11%/89% |

| Comorbidities | |

| History of atrial fibrillation/flutter | 56% |

| Hypertension | 89% |

| Diabetes | 33% |

| Coronary artery disease | 39% |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 0% |

| HF or HTN medication | |

| Loop diuretic | 83% |

| ACEi or ARB | 33% |

| Beta‐blocker | 56% |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist | 67% |

| Calcium channel blocker | 39% |

| Sacubitril/valsartan | 6% |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 17% |

| Biometrics | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 35.3 (27.6–37.2) |

| LVEF (core lab measured) (%) | 61.0 (56.0–63.2) |

| NYHA class II/III (%) | II: 5.6, III: 88.9, IV: 5.6 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 123.5 (114.5–135.8) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 71.5 (66.2–78.8) |

| Resting heart rate (bpm) | 73.5 (69.2–80.8) |

| NT‐proBNP (pg/ml) | 334 (148–698) |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.94 (0.9–1.3) |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 60.5 (45.2–66.8) |

| Echocardiography | |

| LVEF (core lab measured) (%) | 61.0 (56.0–63.2) |

| Left ventricular mass index (g/m2) | 80.5 (67.7–93.1) |

| LA end‐diastolic volume index (ml/m2) | 19.4 (13.9–25.8) |

| LV end‐diastolic volume index (ml/m2) | 40.4 (37.6–45.7) |

| E/e′ (septal) (unitless) | 15.8 (11.3–21.8) |

| Mitral E velocity/mitral A velocity | 1.0 (0.8–1.8) |

| Baseline invasive exercise haemodynamics | |

| Resting PCWP (mmHg) | 17.0 (4.0–34.0) |

| Legs up PCWP (mmHg) | 24.0 (11.0–33.0) |

| 20 W PCWP (mmHg) | 35.0 (22.0–50.0) |

| Peak PCWP (mmHg) | 37.0 (26.0–50.0) |

| Exercise duration (min) | 6.0 (4.0–9.0) |

| Peak workload (W) | 40.0 (20.0–60.0) |

Values are median (interquartile range) unless otherwise specified.

ACEi, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; CVP, central venous pressure; HF, heart failure; HTN, hypertension; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; LA, left atrial; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; SGLT2, sodium–glucose cotransporter 2.

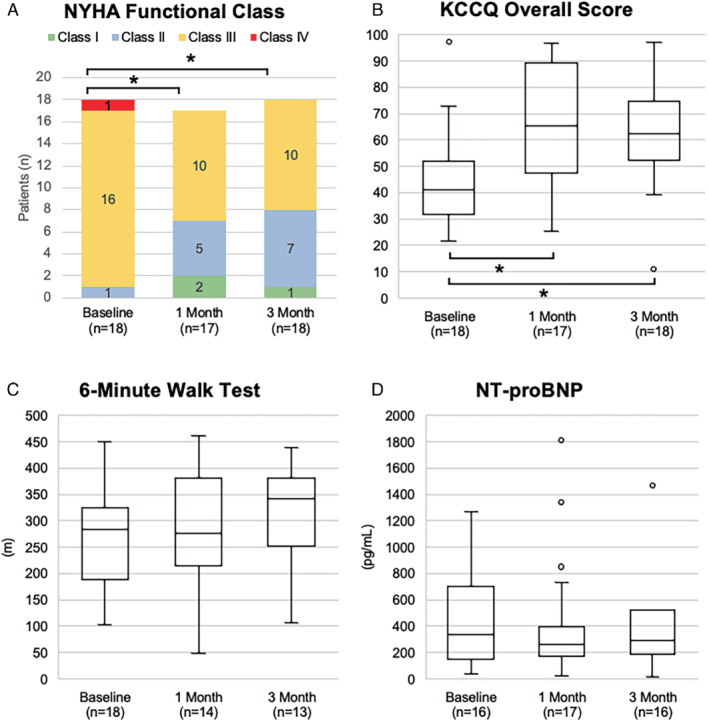

The 20 W PCWP decreased from a mean 36.4 (standard deviation [SD] ± 8.6) to 29.9 (SD ± 7.8) (p < 0.01) and peak exercise PCWP decreased from 39.5 (SD ± 6.9) to 31.9 (SD ± 8.4) (p = 0.01) at 1 month after the SAVM procedure (Figure 2 ). Exercise duration on the supine ergometers changed from a median 6 (4–9) min to 7 (5–10) min (p = 0.51) and the highest achieved resistance on the ergometer (W) was 40 (20–60) at baseline and 40 (40–60) at 1 month (p = 0.56). At 1 month and 3 months post SAVM procedure, 39% and 50% patients experienced at least one NYHA class improvement compared to baseline (p = 0.02 and p < 0.01, respectively) (Figure 3 ). The KCCQ overall summary score improved by 22.1 points (95% confidence interval [CI] 9.4–34.2) (p < 0.01) at 1 month and 18.3 points (95% CI 9.0–27.7) at 3 months (p < 0.01) (Figure 3 ). The median NT‐proBNP was 334 (148–698) pg/ml at baseline, 262 (171–396) pg/ml at 1 month and 291 (187–519) pg/ml at 3 months (all p > 0.05) (Figure 3 ). The 6‐min walk distance changed from 283 (215–322) m at baseline to 276 (239–373) m at 1 month and 342 (257–370) m at 3 months after the SAVM procedure (Figure 3 ). There were no significant changes in echocardiographic measures of left ventricular systolic function (LVEF), diastolic function (E/A, E/e′), left atrial volume or left ventricular mass at 3 months when compared to baseline values (all p > 0.05).

Figure 2.

Change in pulmonary capillary wedge pressure at baseline and 1 month after greater splanchnic nerve ablation. Discrepancy in case numbers between baseline and 1 month is explained by either missed or uninterpretable recordings. Means and standard deviation are presented. *Indicates a comparison between baseline and 1 month using a mixed model repeated measures analysis with a p‐value <0.05.

Figure 3.

Comparison of baseline New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class (A), Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) (B), 6‐min walk distance (C) and N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) (D) compared to 1 month after greater splanchnic nerve ablation. Medians and interquartile range are provided unless otherwise specified. *Indicates a Wilcoxon signed rank test (compared to baseline) with a p‐value <0.05.

Discussion

The preliminary open‐label results from the REBALANCE‐HF roll‐in cohort support the safety and efficacy of SAVM in HFpEF. GSN ablation treatment was associated with a reduction in PCWP during exercise and improvement in symptoms and health status without a significant difference in exercise capacity. The treatment procedure was associated with three moderate, non‐serious device/procedure‐related adverse events but no serious adverse events, and learnings from these events in the roll‐in portion of the trial have informed the conduct of the randomized portion of the trial (e.g. periprocedural intravenous fluids are now being minimized). The greater reduction in PCWP is notable and consistent with recent data showing that abnormalities in venous capacitance importantly contribute to haemodynamic perturbations that develop during exercise in HFpEF. 13 These results are limited by the single‐arm, open‐label design; thus, the results are subject to treatment and observation bias. To avoid confounding by pharmacological medical management on the endpoints of interest, a stable medical HF medical regimen 30 days before and 3 months after the SAVM procedure was required. The findings presented here require confirmation in the ongoing randomized, sham‐controlled portion of the REBALANCE‐HF trial.

Funding

Axon Therapies, Inc.

Conflict of interest: M.F. was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (K23HL151744), the American Heart Association (20IPA35310955), Mario Family Award, Duke Chair's Award, Translating Duke Health Award, Bayer, Bodyport and BTG Specialty Pharmaceuticals. He reports consulting fees from Abbott, Audicor, AxonTherapies, Bodyguide, Bodyport, Boston Scientific, CVRx, Daxor, Edwards LifeSciences, Feldschuh Foundation, Fire1, Gradient, Intershunt, NXT Biomedical, Pharmacosmos, PreHealth, Splendo, Vironix, Viscardia, Zoll. B.A.B. has received research support from R01 HL128526 and U01 HL160226, from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and W81XWH2210245, from the United States Department of Defense, as well as research grants from AstraZeneca, Axon, GlaxoSmithKline, Medtronic, Mesoblast, Novo Nordisk, and Tenax Therapeutics; has received consulting fees from Actelion, Amgen, Aria, Axon Therapies, BD, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, Edwards Lifesciences, Eli Lilly, Imbria, Janssen, Merck, Novo Nordisk, NGM, NXT, and VADovations; is named inventor on an issued patent (US Patent no. 10307179) for the tools and approach for a minimally invasive pericardial modification procedure to treat heart failure. V.Y.R. reports serving as a consultant to, and holding stock options in, Axon Therapies. In addition, he has other disclosures not related to this manuscript: Consultant – Abbott, Biosense‐Webster, BioTel Heart, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Cardiofocus, Cardionomic, CoreMap, EBR, Fire1, Gore & Associates, Impulse Dynamics, Medtronic, Philips, and Pulse Biosciences; Consultant, Equity – Ablacon, Acutus Medical, Affera, Apama Medical, APN Health, Aquaheart, Atacor, Autonomix, Backbeat, BioSig, Cardiac Implants, CardiaCare, CardioNXT/AFTx, Circa Scientific, Corvia Medical, Dinova‐Hangzhou DiNovA EP Technology, East End Medical, EPD, Epix Therapeutics, EpiEP, Eximo, Farapulse, HRT, Intershunt, Javelin Lld, Kardium, Keystone Heart, LuxMed, Medlumics, Middlepeak, Nuvera, Philips, Pulse Biosciences, Restore Medical, Sirona Medical, and Valcare; Equity – Manual Surgical Sciences, Newpace, Surecor, and Vizaramed. D.B. reports consulting fees from Axon Therapies. S.J.S. has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health (U54 HL160273, R01 HL107577, R01 HL127028, R01 HL140731, R01 HL149423), Actelion, AstraZeneca, Corvia, Novartis, and Pfizer; and has received consulting fees from Abbott, Actelion, AstraZeneca, Amgen, Aria CV, Axon Therapies, Bayer, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Cardiora, Coridea, CVRx, Cyclerion, Cytokinetics, Edwards Lifesciences, Eidos, Eisai, Imara, Impulse Dynamics, Intellia, Ionis, Ironwood, Lilly, Merck, MyoKardia, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Prothena, Regeneron, Rivus, Sanofi, Shifamed, Tenax, Tenaya, and United Therapeutics. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Supporting Information.

References

- 1. Obokata M, Olson TP, Reddy YNV, Melenovsky V, Kane GC, Borlaug BA. Haemodynamics, dyspnoea, and pulmonary reserve in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:2810–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reddy YNV, Olson TP, Obokata M, Melenovsky V, Borlaug BA. Hemodynamic correlates and diagnostic role of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6:665–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dorfs S, Zeh W, Hochholzer W, Jander N, Kienzle RP, Pieske B, et al. Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure during exercise and long‐term mortality in patients with suspected heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:3103–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fudim M, Khan MS, Paracha AA, Sunagawa K, Burkhoff D. Targeting preload in heart failure: splanchnic nerve blockade and beyond. Circ Heart Fail. 2022;15:e009340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fudim M, Ponikowski PP, Burkhoff D, Dunlap ME, Sobotka PA, Molinger J, et al. Splanchnic nerve modulation in heart failure: mechanistic overview, initial clinical experience, and safety considerations. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23:1076–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bapna A, Adin C, Engelman ZJ, Fudim M. Increasing blood pressure by greater splanchnic nerve stimulation: a feasibility study. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2019;13:509–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fudim M, Yalamuri S, Herbert JT, Liu PR, Patel MR, Sandler A. Raising the pressure: hemodynamic effects of splanchnic nerve stimulation. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2017;23:126–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fudim M, Neuzil P, Malek F, Engelman ZJ, Reddy VY. Greater splanchnic nerve stimulation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:1952–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fudim M, Ganesh A, Green C, Jones WS, Blazing MA, DeVore AD, et al. Splanchnic nerve block for decompensated chronic heart failure: splanchnic‐HF. Eur Heart J. 2018; 39:4255–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fudim M, Boortz‐Marx RL, Ganesh A, DeVore AD, Patel CB, Rogers JG, et al. Splanchnic nerve block for chronic heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8:742–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Malek F, Gajewski P, Zymlinski R, Janczak D, Chabowski M, Fudim M, et al. Surgical ablation of the right greater splanchnic nerve for the treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: first‐in‐human clinical trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23:1134–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fudim M, Engelman ZJ, Reddy VY, Shah SJ. Splanchnic nerve ablation for volume management in heart failure. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2022;7:319–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sorimachi H, Burkhoff D, Verbrugge FH, Omote K, Obokata M, Reddy YNV, et al. Obesity, venous capacitance, and venous compliance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23:1648–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Supporting Information.