Abstract

Background

Left ventricular assist device (LVAD) evaluation includes a psychosocial assessment, conducted by social workers (SW) on the advanced HF multidisciplinary team. 24/7 post-discharge caregiving plans are central to psychosocial evaluation. Caregiving’s relationship with LVAD outcomes is mixed, and testing patients’ social resources may disadvantage those from historically-undertreated groups.

We describe variation in policies defining adequate caregiving plans post LVAD implant, and possible impacts on patients from marginalized groups.

Methods

Two-phase sequential mixed-methods study. Phase 1: survey of US-based LVAD SWs, describing assessment structure and policies guiding candidacy outcomes. Phase 2: individual interviews with SWs to further describe how caregiving plan adequacy impacts LVAD candidacy.

Results

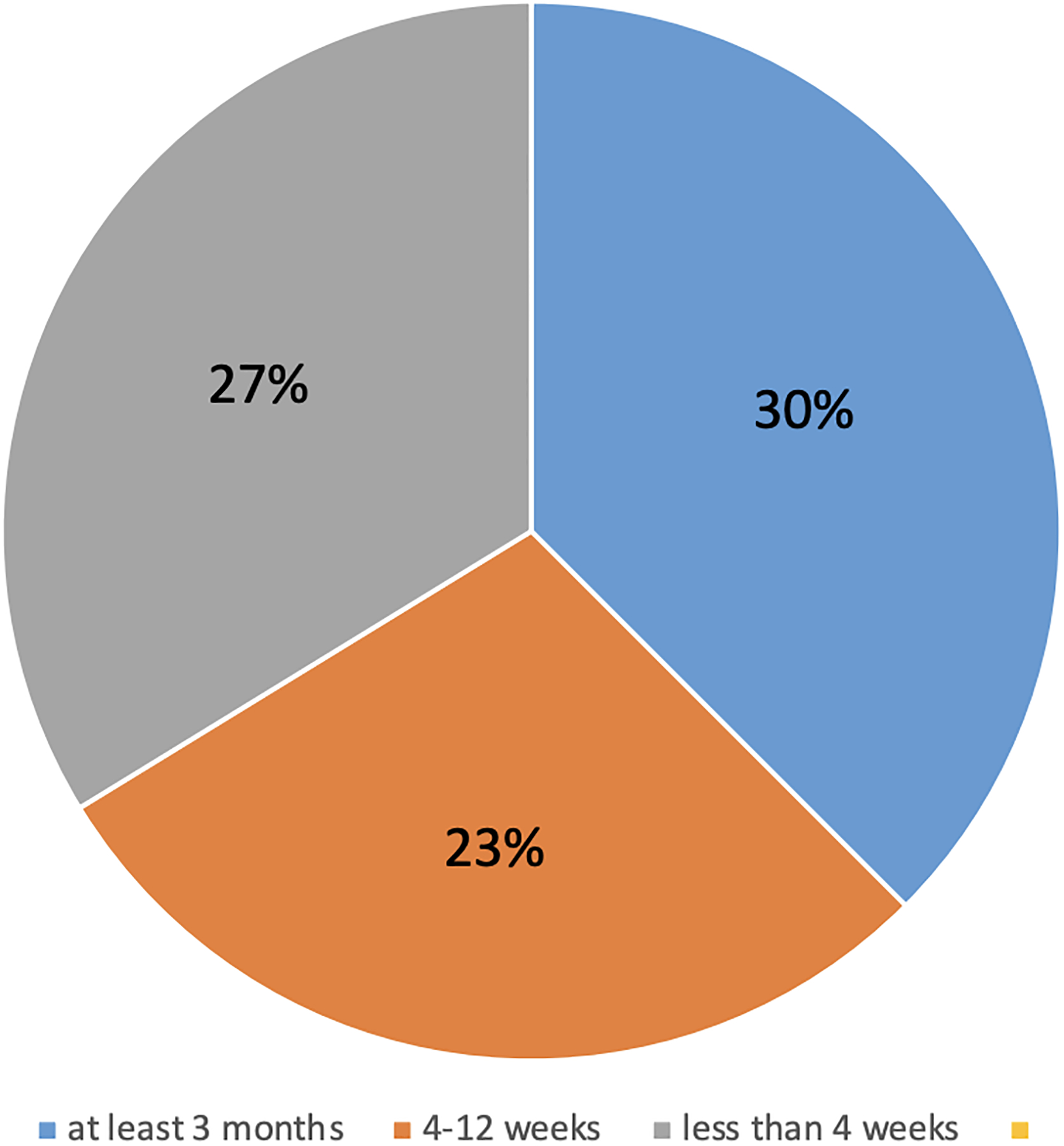

67 SWs returned surveys (rr=47%) from unique programs. Caregiving plan inadequacy (n=30) was the most common psychosocial “dealbreaker”. When asked what duration of caregiving is required, 23% indicated ≥3 months, 27% 4–12 weeks, and 30% <4 weeks. Two reported no duration requirement, six stated an indefinite 24/7 commitment was necessary.

Across 22 interviews, SWs mirrored that caregiving plans were the most common psychosocial contraindication. How caregiving is operationalized varied. Participants voiced a tension between extended caregiving improving outcomes and the sense that some BIPOC, women, or low-SES patients struggle to meet stringent requirements.

Conclusions

Policies regarding adequate duration of 24/7 caregiving vary, but inadequate caregiving plans are the most common psychosocial contraindication. Participants worry about patients’ ability to meet restrictive requirements, particularly from historically-undertreated groups. This highlights a need to operationalize quality caregiving, standardize assessment, and support medically-appropriate patients with strained social resources.

Keywords: Left ventricular assist device (LVAD), psychsocial evaluation, equity, mixed-methods

INTRODUCTION

Left ventricular assist devices (LVAD) can improve survival and quality of life in patients with medically-refractory advanced heart failure (HF)1,2. However, LVADs involve significant risks and substantial patient-borne burdens and costs.3–5 Thus, the decision to implant an LVAD requires careful candidate selection to minimize potential harms and optimize outcomes. Informal/family caregiver involvement is generally recognized as an important contributor to positive postoperative outcomes after LVAD implantation,6–8 although the evidence for specific caregiving requirements and outcomes is mixed9–12. Once identified, caregivers are asked to play a central role in patients’ recovery, ranging from day-to-day assistance with mobility, to device and driveline maintenance, to medication adherence, to considering potentially weighty decisions about future care.13,14

The patient pathway to being evaluated and considered for an LVAD involves medical and psychosocial evaluation, the latter including the patient’s availability and reliability of social support after surgery.15 The evaluation process is guided by health insurer requirements for payment (e.g., Medicare16), standard certifications (e.g., the Joint Commission), and expert consensus documents (e.g., 2018 ISHLT/APM/AST/ICCAC/STSW)6 but implanting centers ultimately develop their own criteria for candidacy, including requirements for caregiving.9 Caregivers are typically asked to provide 24/7 in-home support for patients for a designated period of time post discharge, although no guidelines exist for the duration of this commitment.

Within this context, we set out to characterize variation in psychosocial evaluation assessment prior to LVAD implantation, with an a priori focus on standards applied to caregiver duration and other social support plans when determining LVAD candidacy. We chose to include an a priori focus on caregiver duration requirements as they call directly upon patients’ social resources, which critically include access to others who are able to spend extended periods of time away from work and family. Since hourly employment, working for small companies (who are not required to provide protected leave under the Family Medical Leave Act), and living in a home maintained by one adult are all more common among women and people of color17,18, LVAD candidacy requirements which test these resources carry the possibility of differentially impacting patients from historically marginalized and undertreated groups.

METHODS

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. We utilized a two-phase sequential mixed-method study. Phase 1 was an online survey of US-based LVAD/transplant social workers. Items assessed both the structure of the psychosocial evaluation as well as domains assessed, and included both fixed category and open-response items. In Phase 2, we triangulated survey data with semi-structured interviews of individual LVAD/ heart transplant social workers. All methods described were approved by the University of Colorado Combined IRB (COMIRB).

Sample & Analysis

Survey:

We conducted a nationwide online survey of advanced HF social workers. This survey was distributed through the Society for Transplant Social Workers (STSW), the largest professional society for social workers employed at advanced HF centers in the US. Results from open-ended items were categorized and grouped thematically. All findings were descriptive and included percentages and case counts. No statistical analyses were conducted.

Interviews:

Social work practitioners currently conducting LVAD assessments at US-based centers were identified using a combination of methods. First, we acquired contact information for all members of STSW’s mechanical circulatory support leadership committee. Second, we received contact information for social workers listed as site contacts for I-DECIDE-LVAD19, a learning community-based implementation program supporting shared decision making in LVAD care. Finally, we utilized snowball sampling at the end of each interview, whereby participants referred our team to social work colleagues employed at different advanced HF centers. Interviews were continued until thematic saturation was reached. All interviews were conducted via Zoom videoconferencing by members of the parimary analytic team (CK, BJS, CM, PK), and participants received a $40 gift card as compensation.

Interviews were analyzed using a team-based mixed inductive/deductive method, derived from those previously used by members of the research team20–22. Coding was conducted by the primary analytic team (CEK, BJS, ALL, CM, PK) who have masters and doctoral level training and practice experience in clinical social work, advanced heart failure therapy and evaluation, and qualitative research methods. The team applied a mix of established analytic methods to interview transcripts, including constant comparative, grounded theory, and content analysis methods.23 These included both a codebook developed a priori addressing the primary research questions and hypotheses regarding 1) caregiver duration requirements, 2) domains assessed in the psychosocial evaluation, and 3) the most common reasons for psychosocial disqualification for LVAD therapy, as well as emergent inductive codes and superordinate themes.24 All coding activity and synthesis into themes was conducted using Dedoose analytic software (v 9.0.17: SocioCultural Research Consultants, Los Angeles, CA). All interviews were coded independently by at least two members of the analytic team, who met bi-monthly over the course of analysis to sort, synthesize, and conceptually discuss emergent codes and thematic structure, as well as ensure consistent application of the codebook. This team coding approach maximizes confirmability and reliability of findings24,25, as well as provides a venue in which to clarify nuanced medical, ethical, policy, and social work practice issues discussed by interviewees among the entire coding team.

RESULTS

Phase 1: Survey.

We received 67 surveys (response rate=47%) from social workers who had conducted LVAD assessments for a mean of 5.45 years, representing individual programs in 26 US states (Table 1). We elected not to collect traditional demographic information to preserve participants’ perception of confidentiality given the small community of practicing LVAD social workers.

Table 1:

Characteristics of Social Workers and Centers Responding to Online Survey

| Demographics of Participants/Site Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| m(IQR) | ||

| Tenure conducting MCS/transplant evaluations, years | 5.6[1.5,8] | |

| Approximate number of LVADs implanted per year at center | 33.2[10.5, 50] | |

| n(valid %) | ||

| Patient populations seena | LVAD Candidates | 54(81) |

| Heart Transplant Candidates | 53(79) | |

| Other Transplant Candidates | 17(25) | |

| Outpatient Heart Failure | 34(51) | |

| Inpatient Heart Failure | 29(43) | |

| Outpatient General Cardiology | 4(6) | |

| Inpatient General Cardiology | 4(6) | |

| Other: Non cardiac outpatient clinic | 2(3) | |

| Social work licensure | Independently licensed | 43(64) |

| Provisionally licensed | 3(4.5) | |

| Not licensed | 1(1.5) | |

| Missing | 20(29) | |

Note.

Participants able to choose more than one

Primary findings included that when asked to name psychosocial “dealbreakers” (single issues which would be considered a contraindication at their site, with no limitation on the number of dealbreakers they could list), the most common response (n=30) was having an inadequate post-discharge caregiver plan. Secondary findings included concerns about substance misuse (n=11), a lack of insurance (n=9), mental illness (n=5), and housing instability (n=4) (Table 2).

Table 2:

Identified Psychosocial “Dealbreakers” with Representative Quotes

| Identified “Dealbreaker” (number of mentions) | Representative Examples |

|---|---|

| Inadequate post-discharge caregiving plan (n=30) | “Inability to develop support system” |

| “lack of caregiving plan” | |

| “no viable caregiver plan” | |

| “no caregiver” | |

| Substance misuse (n=11) | “addiction to pain medications, active meth/cocaine use” |

| “IV substance user-active” | |

| “chronic substance use” | |

| Lacking insurance (n=9) | “no insurance and no ability become insured within a reasonable amount of time” |

| “undocumented with no pathway to insurance (as determined by pro-bono lawyers)” | |

| “lack of health insurance (unless Medicaid pending as we go to financial oversight)” | |

| Mental illness (n=5) | “severe and untreated mental health” |

| “unchecked mental health concerns” | |

| Housing instability (n=4) | “Lack of stable/safe housing” |

| “Homelessness” |

Separately, there were a wide range of responses for the duration of time different centers considered an “adequate” a priori plan for 24/7 caregiving post discharge (n=44). Of those who responded, 23% indicated that caregivers were required to commit to at least 3 months of 24/7 care, 27% between 4–12 weeks, and 30% less than 4 weeks (Figure 1). Of note, two respondents indicated that their employing centers did not have any caregiver duration requirement, while six stated that an indefinite commitment to 24/7 care was necessary.

Figure 1:

Length of Time Considered “Adequate” for 24/7 Post-Discharge Caregiving (n=44)

Phase 2: Interviews.

Semi-structured interviews were completed with 22 social workers between March and May of 2021, representing 21 programs in 14 US states. Over half of the respondents were employed within academic medical centers (n=12) and 19 offered both LVAD and transplant (Table 3). Two interviewees had previously worked in advanced HF at other hospitals. Interviews ranged in length from 30 to 90 minutes.

Table 3:

Characteristics of Social Workers and Centers Participating in Individual Interviews

| Participant/Center Characteristic | n=22 | |

|---|---|---|

| Female n(%) | 20(91) | |

| Tenure in heart failure, years m(IQR) | 5.3 [2.5, 6.75] | |

| Hospital type n(%) | Academic medical center | 12 (55) |

| Private | 6 (27) | |

| Private teaching | 3 (14) | |

| VA | 1 (5) | |

| Advanced therapies provided at center n(%) | LVAD only | 2 (9) |

| LVAD and Transplant | 20 (91) | |

Domains assessed:

Mirroring findings from the Phase 1 survey, when asked which psychosocial domains have the greatest impact on whether a patient would qualify for an LVAD, interviewees universally (100%) referenced the postoperative caregiver plan (including who would be a 24/7 caregiver and for what duration), and all but one (96%) indicated patient mental health and/or substance use. As one indicated “I mean, mental health, substance use, [and] caregiver support are of course, the big ones… If they don’t have good caregiver support, that’s an absolute contraindication… so is substance use. There are a couple of areas of mental health that are contraindications.” (Participant 7)

Caregiver Plan:

When asked if their center requires a specific duration for a 24/7 post-operative caregiver for a patient to qualify for LVAD, requirements again varied considerably. In some cases, a duration requirement was considered an absolute rule, effectively ending candidacy for patients who could not identify a set of caregivers to cover the requisite time period. Some participants stated that their centers had no concrete or quantitative requirement for caregiving but that they still considered it an important component of the evaluation. As one described, “not to scare them… but you really have to have this caregiver in place in order for us to feel comfortable with moving forward with giving you the LVAD or getting you transplanted because you’re not going to be able to take care of yourself afterwards for a little while, and you’re going to need some help… being very clear that not having somebody is going to likely be a barrier to getting them the care that they need” (Participant 10).

In these cases, social workers often spent substantial time and effort creatively helping those patients who were not immediately able to identify available caregivers. These activities included both identifying additional people who might be able to help the patient, and coaching the patient as to how to ask for support. As one participant described, “what I always say is, in the beginning, weeks, or months, and then, I try and figure out what’s going to work with this family, and sometimes, we just try and piece it together. I’ll use the analogy of a patchwork quilt - are there people in your formal system, people in your informal system. Usually, it doesn’t work so great, but sometimes there could be a few family caregivers who can bond together.” (Participant 5). These problem-solving efforts were sometimes critical to patients’ continued candidacy. As explained by another participant ”if we have a caregiver who says, ‘I absolutely can’t take any time off work,’ we would really need to think through who can patchwork in when they’re at work. And if there really isn’t anyone, I think it would be a conversation with the team of, ‘What do we do, how can we help get resources off the place or if not, you know, perhaps this isn’t the right center’” (Participant 8).

Alternatively, a few social workers reported that an inability to identify caregivers might not be an absolute contraindication to LVAD therapy in certain circumstances. As one explained, “I think that we want someone to stay with them 24/7 for two to four weeks after they go home. But that being said… I have a patient who lives alone, and he has absolutely no caregiver, he has supportive friends that check in on him, but he does his own dressing changes. And he doesn’t have a caregiver and he’s doing great… I think it depends on each person. There’s some people that we are nervous about beforehand, and we say to their caregiver… “we need you to commit to this amount of time, just because this person will probably need help. And if you were to disappear, they would probably fail a lot.” But no, we don’t have a hard policy of - required time” (Participant 3). Another remarked that, “I think that there could be exceptions. I think there are certainly times where we would consider a patient who maybe seems like they’re going to do well after surgery, who’s maybe younger and more physically able, pre-VAD to kind of say, okay, you know, your partner, your support can only commit to really taking off two weeks after VAD. I think we can work with that.“ (Participant 9)

Other participants described circumstances where caregiver duration requirements might be relaxed postoperatively, owing to a patient’s particular ability to manage recovery. One interviewee stated, “I think the biggest thing that I always tell my patients is, this is not a hard, fast rule. It could be less; it could be more. Our team is pretty amicable to assessing a patient and saying, “You know what, they’re looking good. They’ve had no complications. Their hospitalization was great.” And they’ll allow them to go home early’” (Participant 14).

When asked to respond to the fact that some centers have duration requirements of three months or more, social workers at centers with shorter or more flexible requirements expressed concern about how many of their patients would have been denied for therapy. One proclaimed “I say send them to (our center)…There are quite a few patients who would not have gotten a VAD from our program if that was our policy.” (Participant 3)

Interviewees described a related ethical tension by acknowledging that strict requirements for long-term caregiving reduce the number of high-risk candidates who would eventually be given a device, improving program outcomes but coming at the cost of marginalizing those without the social and financial resources to support them for extended periods. One remarked that “our lung program actually has very strict requirements. They tell people to expect to relocate for six months to a year, and those caregivers are expected to stay, and they have good outcomes related to that…Three months sounds a really long time (though), and I’m just not sure how many people can feasibly do 24/7 support and manage their financial needs for that long.” (Participant 17)

Participants also shared their suppositions about groups of patients who seemed more likely to be challenged in identifying caregivers. Participants described these patients as either being isolated or otherwise having limited social contact. They described social isolation due to small social circles, like those who are single and/or middle aged, or with histories of substance misuse. Participants also described patients whose social contacts were limited by societal, political, and institutional constraints, including those who are undocumented, are expereincing poverty, or who have been historically racially marginalized. For example, “I will say persons of color probably struggle the most and that’s typically if they struggle with access to health care previously or have consistent jobs that don’t allow for benefits [with] sustained income and insurance. Caregivers are a lot more stressed and strained in that population” (Participant 12). In one case, the participant’s center had specific conversations about the impact of SES and race on LVAD candidacy requirements, resulting in active efforts to undermine disparities within their population. As this individual stated “my concern at that time was we’re seeing this influx of these patients coming in from this demographic background (with more varied) socioeconomic statuses, let’s be careful that we’re not biased to, you know, deny them because of that, because of all of these other variables that are well beyond our control, but are well within the scope of just the patient’s cultural identification… (I’ve) tried to do some education and to take all that into consideration when evaluating the patients, but I don’t think that it’s kind of hindered their ability to be candidates” (Participant 10).

DISCUSSION

Among social workers who participate in formal LVAD evaluation, an inadequate post-implant caregiver plan was cited as the most common psychosocial “hard stop” to continued consideration for therapy. At a national level, whether a patient is deemed to have an adequate plan is a function of the center at which they are being evaluated, as the duration of 24/7 caregiving post implant necessary for continued candidacy ranges from “none” to “indefinitely”, with clusters of centers requiring up to a month, up to two months, or at least three months of dedicated support. Some social work participants reported that duration requirements were absolute (i.e. that part of what made a plan “adequate” was the number of weeks caregivers promised to provide 24/7 support). Others were flexible and/or reconsidered after having the opportunity to observe how patients recovered in the weeks following surgery, providing opportunities to amend or problem solve aspects of caregiver arrangements according to the patients’ early recovery. This flexibile approach could be seen as both patient-centered and utilitarian, as it could allow patients who are recovering well medically to regain independence more quickly, while allowing for the reality that some require various forms of support for the rest of their lives.

The level of support required of caregivers is burdensome26,27. It includes extended time away from work, often living away from their own families, and needing to be ready and able to provide emergency assistance and problem solving at any moment12. The subgroup of patients with advanced HF whose social resources could meet the challenge of these demands for several months is likely not representative of the HF population broadly. At centers with more restrictive standards, patients who do not live with a partner, have adult children living nearby without competing demands, or an expansive social group are therefore logically more likely to be declined for LVAD.

Events over the past few years have awakened the the medical community to the presence of institutionalized structures that further oppress people already made vulnerable by historically-determined social resources and inequitable access to healthcare. The subjective nature of specific time requirements raises the concern that these patients are denied potentially lifesaving therapy for their medically-refractory HF because of the very environment (and interconnected social resources) which put them at risk for poorer health in the first place.

Variability in LVAD candidacy policies and this possible link to intersecting, historical marginalization in the duration of caregiving deemed sufficient as a precondition to candidacy is particularly challenging given the lack of predictive value that duration of caregiving has for outcomes in the LVAD population. In our contemporary understanding, overall psychosocial risk (including social support among a host of other domains) only weakly associates with any post-implant outcome, and no domain – including caregiver plan or social support - does so individually8. While having an excellent caregiver carries substantial mortality advantage over one with deficiencies14, there is no current evidence or guideline support identifing “good enough” caregiving, let alone how long such caregivers need to be available to confer benefit to patients.

Lacking a true empirical basis to these standards and the ability and willingness of some centers represented in our samples to create flexible, inclusive, and creative solutions in cases where patients’ social resources are limited, highlight opportunities to improve LVAD equity. It may be possible that an a priori assessment of patients’ abilities and propensity to problem solve and self-manage could eliminate the need to identify caregivers for this subset of patients, or that post-surgical assessments grounded in occupational or rehabilitation therapy principles may limit the need for extensive 24/7 support in selected cases28. Some LVAD centers, both represented in our data and elsewhere, have taken the additional step of creating “loner tracks” within their LVAD programs, allowing patients with certain levels of pre-surgical functioning the option to recover without caregiver support if they are unable to find it (using a variety of professional rehabilitation and at-home support models). Further, training and support should be created and disseminated to other rehabilitation and professional support providers (including skilled nursing facilities, long term acute care, assisted living communities, and others) to increase their comfort and willingness to accept patients with LVADs into their centers. Future research should investigate the clinical viability of such possibilities, as they stand a chance to mitigate unintentional, historically grounded, systemic racism and classism by limiting more restrictive caregiver duration requirements to patients whose safety would benefit from extended in-home support.

These findings should be considered in light of several limitations. First, while we made every effort to triangulate findings between survey and interviews results (and gathered data from as many as half of all social workers currently employed in LVAD centers in the US), it may be possible that they are not fully representative of the full spectrum of pre-LVAD evaluation. Relatedly, while our 47% response rate for our Phase 1 survey is modest, the primary findings (that inadequate caregiving plans are a common psychosocial dealbreaker for LVAD candidates, and the definition of an adequate duration of caregiving varies substantially), would not likely be affected by an increased response rate. The homogeneity of the workforce of Masters-level clinical social workers in the US (estimated to be >85% identifying as female, >70% white, and >90% non-Hispanic29) further reduces concern about systematic response bias within our sample. Second, our interviews focused primarily on the psychosocial evaluation for pre-LVAD implantation due to the high caregiving needs that often occur post implant, but most of our interview participants worked in centers offering transplant, and noted that their evaluations commonly were meant to assess patients for either treatment. Caregiver duration or other criteria applied to evaluations conducted at other centers, particularly those in private hospitals and/or those without transplant programs, may differ, and understanding those differences is critical to designing any standardized assessment procedure. Also, while we designed our projects with a priori hypotheses related to the variability of caregiver requirements, our qualitative method is inherently descriptive. To mitigate risks to stability or replicability, we triangulated these topics between survey items and individual interviews, conducted team-based qualitative analysis, and constantly compared analytic memos at regular team meetings.

This uncomfortable tension – where clinical consensus holds caregiver availability as critical to successsful treatment in most cases, but with the recognition that the evidence supporting caregiver duration requirements to be modest, and holding patients to hard-and-fast standards potentially disadvantages certain demographic groups – highlight additional opportunities for future work. First, variation is often a reflection of a lack of data, and “quality caregiving” needs to be specifically operationalized to remove a host of potential biases30. An improved understanding of what caregiver capabilities and activites improve LVAD outcomes (or lower risks) could facilitate both standardization of support planning prior to LVAD placement. With such an evidentiary baseline, it may be possible to create center-specific social care interventions which expand access to treatment in a manner which is responsive to the needs of patients seen in each program. Empirically operationalizing caregiving standards and attributes can begin by examining how existing policies and practices at specific centers associate with LVAD access and clinical outcomes among patient groups. Given the variability in caregiver duration requirements we observed, it may be possible to characterize any independent relationship these requirements have with clinical outcomes and/or differential impact on patients according to demographic background. Comparing outcomes between centers with less versus more stringent requirements is a critical step toward developing best practices in psychosocial assessment. It also remains possible that individual centers, social workers, heart failure specialists, or others have created formal or informal interventions to circumvent social barriers within their programs. Although, as with standardized psychosocial evaluation protocols9, these policies have not yet been broadly adopted and have not been evaluated to determine whether they negatively affect clinical outcomes.

Our findings provide strong theoretic support for the presence of structural barriers to advanced heart failure therapy candidacy among patients from historically marginalized and undertreated groups. While these historically-grounded race, gender, class, and other demographic inequites in access may account for some disparate reception of advanced HF therapies, there are certainly other contributors. Caregiver duration requirements are only one example of psychosocial standards or requirements within the context of LVAD, transplantation, or other advanced, emerging, and technologically complex therapies which are variably applied, creating further opportunities for unequal opportunity for patients according to the center at which they are evaluated. The medical community and policy makers need to reevaluate absolute cutoffs and establish national standards. The goal of standardizing psychosocial evaluations would be to preserve multidisciplinary teams’ ability to understand the nonmedical context patients carry into their recovery while mitigating the risk that variable standards, as applied, are structurally biased.30,31

Short commentary:

What’s New?

The psychosocial evaluation for left ventricular assist device (LVAD) placement varies by center, including the deficinition of what’s considered an “adequate” 24/7 caregiver support plan post-discharge. While social workers who conduct these evaluations told us that having an indequate caregiver plan was the most common psychosocial reason someone might be denied LVAD therapy, how adequacy is determined varied substantially. This has implications for patients from historically-undertreated groups, which was expressed as a concern by social workers we interviewed.

Clinical Implications?

Patients from historically-undertreated backgrounds are under-represented among LVAD recipients. This is certainly multifactoral, but variable standards applied to the psychosocial evaluation may inadvertently perpetuate inequitable reception of advanced heart failure therapies. Further research is needed to define appropriate psychosocial criteria and other methods of support, including for caregiving post-discharge, in order to undermine the possibility of structural racism and classism in these standards.

Funding:

This study was funded by the Ludeman Family Center for Women’s Health Research, University of Colorado School of Medicine. Dr. Knoepke has research grant support from the American Heart Association (18CDA34110023) and the National Institutes of Health (K23 HL153892). Dr. Khazanie has research grant support from National Institutes of Health (K23 HL145122) and the Doris Duke Fund to Retain Clinical Researchers, Center for Women’s Health Research, University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Non-standard abbreviations and acronyms

- LVAD

left ventricular assist device

- HF

heart failure

- SW

social worker

- STSW

Society for Transplant Social Work

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no relevant disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.McIlvennan CK, Magid KH, Ambardekar AV, Thompson JS, Matlock DD, Allen LA. Clinical Outcomes After Continuous-Flow Left Ventricular Assist Device. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7(6):1003–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller LW, Rogers JG. Evolution of Left Ventricular Assist Device Therapy for Advanced Heart Failure: A Review. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(7):650–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacIver J, Ross HJ. Quality of Life and Left Ventricular Assist Device Support. Circulation. 2012;126(7):866–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grady KL, Meyer PM, Dressler D, Mattea A, Chillcott S, Loo A, White-Williams C, Todd B, Ormaza S, Kaan A, et al. Longitudinal change in quality of life and impact on survival after left ventricular assist device implantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77(4):1321–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levelink M, Eichstaedt HC, Meyer S, Brütt AL. Living with a left ventricular assist device: psychological burden and coping: protocol for a cross-sectional and longitudinal qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e037017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dew MA, DiMartini AF, Dobbels F, Grady KL, Jowsey-Gregoire SG, Kaan A, Kendall K, Young QR, Abbey SE, Butt Z, et al. The 2018 ISHLT/APM/AST/ICCAC/STSW Recommendations for the Psychosocial Evaluation of Adult Cardiothoracic Transplant Candidates and Candidates for Long-term Mechanical Circulatory Support. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(5):415–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bui QM, Allen LA, LeMond L, Brambatti M, Adler E. Psychosocial Evaluation of Candidates for Heart Transplant and Ventricular Assist Devices: Beyond the Current Consensus. Circ Heart Fail. 2019;12(7):e006058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirkpatrick JN, Kellom K, Hull SC, Henderson R, Singh J, Coyle LA, Mountis M, Shore ED, Petrucci R, Cronholm PF, et al. Caregivers and Left Ventricular Assist Devices as a Destination, Not a Journey. J Card Fail. 2015;21(10):806–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clancy M, Jessop A. Adoption of ISHLT Recommendations for Psychosocial Evaluation of LVAD Candidates. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021;40(4, Supplement):S440. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dew MA, Hollenberger JC, Obregon LL, Hickey GW, Sciortino CM, Lockard KL, Kunz NM, Mathier MA, Ramani RN, Kilic A, et al. The Preimplantation Psychosocial Evaluation and Prediction of Clinical Outcomes During Mechanical Circulatory Support: What Information Is Most Prognostic? Transplantation. 2021;105(3):608–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koeckert M, Vining P, Reyentovich A, Katz SD, DeAnda A, Philipson S, Balsam LB. Caregiver status and outcomes after durable left ventricular assist device implantation. Heart Lung J Crit Care. 2017;46(2):74–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruce CR, Minard CG, Wilhelms LA, Abraham M, Amione-Guerra J, Pham L, Grogan SD, Trachtenberg B, Smith ML, Bruckner BA, et al. Caregivers of Patients With Left Ventricular Assist Devices: Possible Impacts on Patients’ Mortality and Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support-Defined Morbidity Events. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10(1):e002879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitko L, McIlvennan CK, Bidwell JT, Dionne-Odom JN, Dunlay SM, Lewis LM, Meadows G, Sattler ELP, Schulz R, Strömberg A. Family Caregiving for Individuals With Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(22):e864–e878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McIlvennan CK, Jones J, Makic M, Meek PM, Chaussee E, Thompson JS, Matlock DD, Allen LA. Stress and Coping Among Family Caregivers of Patients With a Destination Therapy Left Ventricular Assist Device: A Multicenter Mixed Methods Study. Circ Heart Fail. 2021. Oct;14(10):e008243. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.120.008243. Epub 2021 Sep 1.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khazanie P REVIVAL of the Sex Disparities Debate: Are Women Denied, Never Referred, or Ineligible for Heart Replacement Therapies? JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7(7):612–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.NCD - Ventricular Assist Devices (20.9.1). Accessed January 4, 2022. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncd.aspx?NCDId=360

- 17.Labor force characteristics by race and ethnicity, 2018 : BLS Reports: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Accessed September 20, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/race-and-ethnicity/2018/home.htm

- 18.Ranji U, Frederiksen B, Apr 21 MLP, 2021. Difficult Tradeoffs: Key Findings on Workplace Benefits and Family Health Care Responsibilities from the 2020 KFF Women’s Health Survey. KFF. Published April 21, 2021. Accessed September 20, 2021. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/difficult-tradeoffs-key-findings-on-workplace-benefits-and-family-health-care-responsibilities-from-the-2020-kff-womens-health-survey/ [Google Scholar]

- 19.IDecideLearning – LVAD Continuing Education For Providers. Accessed January 4, 2022. https://www.idecidelearning.com/

- 20.McIlvennan CK, Allen LA, Nowels C, Brieke A, Cleveland JC, Matlock DD. Decision Making for Destination Therapy Left Ventricular Assist Devices. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7(3):374–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knoepke CE, Allen A, Ranney ML, Wintemute GJ, Matlock DD, Betz ME. Loaded Questions: Internet Commenters’ Opinions on Physician-Patient Firearm Safety Conversations. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(5):903–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siry BJ, Polzer E, Omeragic F, Knoepke CE, Matlock DD, Betz ME. Lethal means counseling for suicide prevention: Views of emergency department clinicians. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2021;71:95–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charmaz K Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. SAGE Publications Inc. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Kay K, Milstein B. Codebook Development for Team-Based Qualitative Analysis. CAM J. 1998;10(2):31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamilton JB. Rigor in Qualitative Methods: An Evaluation of Strategies Among Underrepresented Rural Communities. Qual Health Res. 2020;30(2):196–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flint K, Chaussee EL, Henderson K, Breathett K, Khazanie P, Thompson JS, Mcilvennan CK, Larue SJ, Matlock DD, Allen LA. Social Determinants of Health and Rates of Implantation for Patients Considering Destination Therapy Left Ventricular Assist Device. J Card Fail. 2021;27(4):497–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McIlvennan CK, Jones J, Allen LA, Swetz KM, Nowels C, Matlock DD. Bereaved Caregiver Perspectives on the End-of-Life Experience of Patients With a Left Ventricular Assist Device. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):534–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wyble E What Is the Meaning of Occupational Therapy for Patients With Left Ventricular Assist Devices in Acute Care? Am J Occup Ther. 2018;72(4_Supplement_1):7211520303p1. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salsberg E, Quigley L, Mehfoud N, Acquaviva K, Wyche K, Silwa S. Profile of the Social Work Workforce. Health Workforce Res Cent Publ. Published online October 1, 2017. https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/sphhs_policy_workforce_facpubs/16

- 30.Breathett K, Yee E, Pool N, Hebdon M, Crist JD, Yee RH, Knapp SM, Solola S, Luy L, Herrera-Theut K, et al. Association of Gender and Race With Allocation of Advanced Heart Failure Therapies. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e2011044. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.11044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Churchwell K, Elkind MSV, Benjamin RM, Carson AP, Chang EK, Lawrence W, Mills A, Odom TM, Rodriguez CJ, Rodriguez F, et al. Call to Action: Structural Racism as a Fundamental Driver of Health Disparities: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020. Dec 15;142(24):e454–e468. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000936. Epub 2020 Nov 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]