Abstract

A woman in her 50s with Turner syndrome was referred to the endocrine clinic, having been unaware of her diagnosis until she received a shielding letter from the UK government during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite a neonatal diagnosis of Turner syndrome on her general practitioner record and despite having undergone laparoscopic examination for absent puberty and primary amenorrhoea aged 18 years, she had not received any prior hormone treatment or cardiovascular screening.

Though Turner syndrome is rare, recent data from the UK Biobank suggest that it may be underdiagnosed. Clinicians should be aware of the clinical features and associated complications of Turner syndrome to avoid delayed diagnosis and missed opportunities for treatment.

In this report, we discuss the clinical features of this rare syndrome and current guidelines for screening and treatment. We stress the importance of peer-to-peer support and information sharing through patient-led groups, such as the Turner Syndrome Support Society.

Keywords: Cardiovascular medicine, Endocrinology, Genetic screening / counselling, Reproductive medicine, Congenital disorders

Background

Turner syndrome is an important cause of primary hypogonadism in women caused by monosomy for part or all of the X chromosome. In addition to congenital cardiac and/or renal anomalies, affected women are predisposed to developing metabolic syndrome, autoimmune conditions, respiratory infections and conductive hearing loss through recurrent childhood otitis media.

Patients are often diagnosed prenatally or neonatally due to characteristic anomalies, but may also present in childhood with short stature or in adolescence with primary amenorrhoea and absent puberty. Diagnosis in later adult life is not unknown.

Though Turner syndrome is rare, with an estimated prevalence of 25–50 per 100 000 female births,1 recent evidence from UK Biobank data suggests it may be underdiagnosed.2 Clinicians in all specialties, particularly those in paediatric medicine or general practice, should be aware of the presenting features and consider it as a differential diagnosis. Mortality in women with Turner syndrome is threefold higher than in the general population and prompt referral to a specialist service for screening and treatment is essential, not only to mitigate this risk, but also to facilitate targeted hormone replacement therapy (HRT) during critical windows in the patient’s life.3

Case presentation

A woman in her 50s was referred to the Turner’s syndrome clinic on the Newcastle Endocrinology Service, having only recently learnt of her Turner syndrome diagnosis. Though she was aware she had a ‘chromosomal abnormality’ that was diagnosed at birth, she was not informed that this was Turner syndrome until she queried a shielding letter she had received at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In clinic, her height was measured at 142 cm (4 feet 8 inches) and her weight was 96.1 kg, giving a body mass index (BMI) of 47.5. Her medical history included hypertension, atrial fibrillation and metformin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus. Six years previously, she had undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for obesity, complicated by vitamin B12, folate and vitamin D deficiencies with secondary hyperparathyroidism. Notably, she had suffered recurrent otitis media with effusion requiring multiple grommet insertions during childhood and wore bilateral hearing aids as an adult. Though the Turner syndrome diagnosis was present on her general practitioner record, she underwent laparoscopy at the age of 18 to investigate primary amenorrhoea and delayed puberty. Although her uterus was necessarily underdeveloped, she had never received hormone treatment.

Investigations

Karyotype analysis confirmed the diagnosis of Turner syndrome; all cells were found to carry one normal X chromosome and one X chromosome with two copies of the long arm joined at the centromere (Isochromosome Xq, 46, X, i(X)(q10)). This arrangement results in monosomy for the short arm with trisomy for the long arm and is associated with increased risk of autoimmune thyroiditis.4

Blood tests showed mild folate deficiency anaemia, with normal liver and renal function tests. She was noted to have subclinical hypothyroidism (thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) 5.82mU/L, free T4 (fT4) 16.2 pmol/L) with negative thyroid peroxidase antibodies and positive thyroglobulin antibodies. Reflecting her prior diagnosis of secondary hyperparathyroidism, she was normocalcaemic with a marginally elevated parathyroid hormone (6.9 pmol/L) and was vitamin D replete. Coeliac screen was negative. Her HbA1c was 61 mmol/L.

Her oestradiol level was undetectable with an elevated follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) of 14.1 IU/L, demonstrating primary hypogonadism. Given her longstanding hypogonadism, bone density scan (DEXA) was performed to assess her bone mineral density and showed osteopenia.

Comprehensive cardiovascular workup revealed controlled hypertension (blood pressure 142/68 mm Hg), with normal sinus rhythm on ECG. In view of her increased risk of cardiac malformations, both echocardiogram and cardiac MRI were performed and showed normal cardiac structure with a trileaflet aortic valve and normal aortic dimensions.

Ultrasound of her renal tract showed normal kidney anatomy with a hyperechoic appearance of the liver suggestive of fatty liver disease.

Pneumococcal, haemophilus and tetanus serology were requested to assess vaccine response and demonstrated low antibody titres for both haemophilus influenzae B and tetanus.

Differential diagnosis

Treatment

Given that a significant proportion of women would still be premenopausal at her age, the pros and cons of commencing hormonal treatment were carefully discussed. Though oestrogen replacement would provide significant bone health benefits and potentially reduce her risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, this had to be weighed against side effects such as cramping and vaginal bleeding. She did not feel that having periods would be problematic for her and agreed to start low-dose transdermal oestrogen replacement (25 μg patch changed twice weekly) which was progressively increased to 75 μg over the course of 12 months. At the time of writing, she had still not experienced any cramps or bleeding. She was managed jointly with the diabetes team and started empagliflozin to assist with weight loss and diabetic control. Her anaemia resolved with folic acid supplementation and she received additional tetanus and HiB/MenC booster vaccination in the community, which resulted in good antibody titres on retesting. She was signposted to the Turner Syndrome Support Society, a UK-based charity, for additional information and peer support with her new diagnosis.

Outcome and follow-up

At the time of writing, she remains under 6 monthly endocrine clinic follow-up with BMI and BP monitoring at each clinic visit and 1–2 yearly screening for other autoimmune comorbidities. Her subclinical hypothyroidism is under monitoring with 6 monthly thyroid function tests. We plan to introduce a progestogen to her HRT whenever she first develops symptoms of endometrial hyperplasia (bleeding, cramping).

Discussion

The clinical syndrome of short stature, webbing of the neck, cubitus valgus and hypogonadism was first reported by Henry Turner in 1938.5 Since then, our understanding of Turner syndrome has expanded to include all patients with loss of part or all of an X chromosome on genetic testing. Loss of genes carried on the X chromosome accounts for the phenotypic characteristics of Turner syndrome, including short stature (SHOX)6 and gonadal insufficiency (BMP15).7 Monosomy X (45, X) accounts for 40%–50% of cases, with a further 15%–25% displaying mosaicism for monosomy X (45, X/46 XX) due to non-disjunction in post-zygotic cell division. X chromosome anomalies account for the remaining ~30%, including isochromosome Xq and ring chromosome X. Approximately 10% of patients with Turner syndrome have Y chromosome mosaicism, conferring a higher risk of gonadoblastoma which may justify prophylactic gonadectomy.1

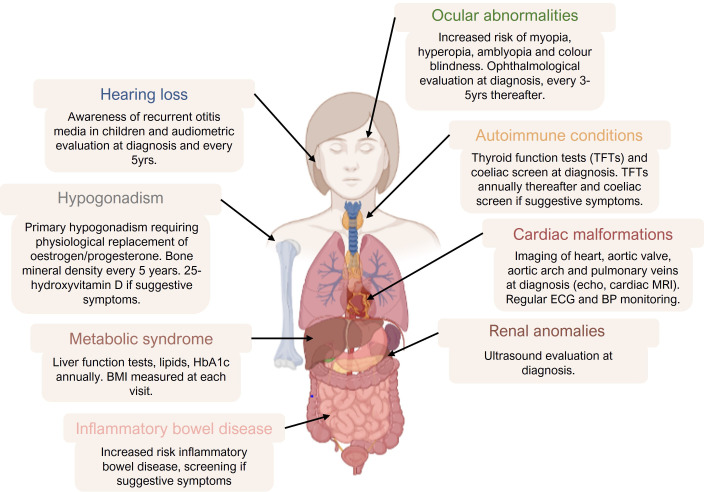

Turner syndrome is diagnosed by karyotype analysis of a tissue sample, usually PMBCs isolated from blood but also dermal fibroblasts, buccal mucosal swab or bladder epithelial cells in urine.8 In one UK study, the mean age of diagnosis was 5.9 years, though 12% of the children fulfilled criteria for earlier testing.9 Prenatal testing may be indicated where fetal anomaly scan shows features such as increased nuchal translucency, fetal hydrops, coarctation of the aorta or horseshoe kidney.8 Infants may have dysmorphic features (webbing of the neck, short fourth metacarpals/metatarsals, widely spaced nipples) and peripheral lymphoedema. Short stature may first become apparent in childhood and girls with Turner syndrome frequently suffer recurrent otitis media with effusion (‘glue ear’). Sexual development falls on a spectrum from primary amenorrhoea and absent puberty to regular menstruation with potential for spontaneous pregnancy, though almost all women develop premature ovarian insufficiency.10 Cardiac malformations are seen in 50% of all patients, including bicuspid aortic valves, coarctation of the aorta, septal defects and coronary artery abnormalities.11 Furthermore, patients with Turner syndrome develop insulin resistance as early as childhood and have an increased risk for obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus and dyslipidaemia.12 Consequently, cardiovascular risk in most patients is high and is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. Turner syndrome also predisposes to autoimmune conditions, particularly autoimmune hypothyroidism and patients often have poor immune response to vaccination.13–15 Patients should be screened for associated conditions at diagnosis and at regular intervals during the follow-up (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Clinical features and recommendations for screening summarised from the 2016 international consensus clinical practice guidelines (1). Image created by DR Sophie Howarth using graphics from Biorender.com. BMI, body mass index. BP, blood pressure. HbA1c, haemoglobin A1c.

The first critical window for intervention is in childhood. Growth hormone supplementation not only increases adult height but has also been shown to reduce central adiposity and restore glucose tolerance.16 Untreated, adults with Turner syndrome are 20 cm shorter than the general female population on average.17 18 Incremental doses of estradiol are used to induce puberty, until appropriate development of the breasts and uterus has been achieved, after which progesterone is then added, usually in a cyclical regimen.19 HRT should be continued until the age of natural menopause.20 Compared with the postmenopausal HRT regimens, higher doses of oestrogen/progesterone tend to be needed in younger women to achieve adequate oestradiol concentrations for bone health and sexual function.21

In addition to the treatment of hypogonadism, adults with Turner syndrome should have regular follow-up with monitoring of BMI and screening for autoimmune conditions and diabetes. Hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidaemia compound the cardiovascular risk in these patients and should be carefully controlled. Bone mineral density should be monitored and other risk factors for osteoporosis should be addressed (eg, vitamin D deficiency and coeliac disease). Patients who wish to become pregnant can be referred for assisted reproductive technologies, usually oocyte donation. The presence of cardiac anomalies and metabolic syndrome increases the risk of adverse events during the pregnancy, hence pregnancy should be supervised in a specialist obstetric clinic.1

We present the case of a woman in her early 50s who had not received prior hormone treatment or cardiovascular screening, despite a neonatal diagnosis of Turner syndrome. Her story, alongside recent biobank data which found the incidence of X chromosome aneuploidy to be four times higher than expected, implies that many women may have missed opportunities for intervention and treatment of their condition. Early referral and follow-up within a specialist service allows targeted intervention during critical windows, reducing morbidity and enabling parenthood if desired.

Learning points.

Clinicians in all specialties should be aware of the clinical features of Turner syndrome and facilitate prompt referral to a specialist service for early screening and intervention.

Affected women should be screened for associated conditions at diagnosis and at regular intervals during follow-up.

Primary hypogonadism in women with Turner syndrome can lead to osteoporosis and increased cardiovascular risk and should be treated with hormone replacement therapy until the age of natural menopause.

Affected women may be able to achieve pregnancy through assisted reproductive technology.

Patient-led support groups, such as the Turner Syndrome Support Society (UK), provide the opportunity for peer-to-peer information sharing and support.

Acknowledgments

We thank Arlene Smyth, Executive Officer at the Turner Syndrome Support Society [UK] for providing the Turner syndrome support society perspective.

Footnotes

Contributors: RQ was involved in conceptualisation and article design. SH wrote the manuscript and designed the figure. Both authors contributed to manuscript review and editing.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: In the past 3 years, RQ has accepted Speaker’s honoraria from Bayer, Besins and Thornton & Ross.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s)

References

- 1.Gravholt CH, Andersen NH, Conway GS, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the care of girls and women with turner syndrome: proceedings from the 2016 cincinnati international turner syndrome meeting. Eur J Endocrinol 2017;177:G1–70. 10.1530/EJE-17-0430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tuke MA, Ruth KS, Wood AR, et al. Mosaic turner syndrome shows reduced penetrance in an adult population study. Genet Med 2019;21:877–86. 10.1038/s41436-018-0271-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schoemaker MJ, Swerdlow AJ, Higgins CD, et al. Mortality in women with turner syndrome in Great Britain: a national cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:4735–42. 10.1210/jc.2008-1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elsheikh M, Wass JAH, Conway GS. Autoimmune thyroid syndrome in women with turner’s syndrome-the association with karyotype. Clin Endocrinol 2001;55:223–6. 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01296.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner HH. A syndrome of infantilism, congenital WEBBED neck, and cubitus VALGUS1. Endocrinology 1938;23:566–74. 10.1210/endo-23-5-566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao E, Weiss B, Fukami M, et al. Pseudoautosomal deletions encompassing a novel homeobox gene cause growth failure in idiopathic short stature and turner syndrome. Nat Genet 1997;16:54–63. 10.1038/ng0597-54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Persani L, Rossetti R, Di Pasquale E, et al. The fundamental role of bone morphogenetic protein 15 in ovarian function and its involvement in female fertility disorders. Hum Reprod Update 2014;20:869–83. 10.1093/humupd/dmu036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolff DJ, Van Dyke DL, Powell CM, et al. Laboratory guideline for Turner syndrome. Genet Med 2010;12:52–5. 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181c684b2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Apperley L, Das U, Ramakrishnan R, et al. Mode of clinical presentation and delayed diagnosis of turner syndrome: a single centre UK study. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol 2018;2018:4. 10.1186/s13633-018-0058-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pasquino AM, Passeri F, Pucarelli I, et al. Spontaneous pubertal development in Turner's syndrome. Italian study group for turner's syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997;82:1810-3–3. 10.1210/jcem.82.6.3970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mortensen KH, Andersen NH, Gravholt CH. Cardiovascular phenotype in turner syndrome--integrating cardiology, genetics, and endocrinology. Endocr Rev 2012;33:677–714. 10.1210/er.2011-1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caprio S, Boulware S, Diamond M, et al. Insulin resistance: an early metabolic defect of turner's syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1991;72:832–6. 10.1210/jcem-72-4-832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanakatti Shankar R. Immunological profile and autoimmunity in turner syndrome. Horm Res Paediatr 2020;93:415-422–22. 10.1159/000512904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bukowczan J, Liew A, Roberts G, et al. Immunity to haemophilus influenzae B and peumococcal vaccination among adult women with turner syndrome. Endocrine Abstracts 2016;41. 10.1530/endoabs.41.EP657 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swee DS, Spickett G, Quinton R. Many women with turner syndrome lack protective antibodies to common respiratory pathogens, haemophilus influenzae type B and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Endocrinol 2019;91:228-230–30. 10.1111/cen.13978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wooten N, Bakalov VK, Hill S, et al. Reduced abdominal adiposity and improved glucose tolerance in growth hormone-treated girls with turner syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:2109–14. 10.1210/jc.2007-2266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brook CGD, Mürset G, Zachmann M. Growth in children with 45, Xo turner’s syndrome. Arch Dis Child 1974;49. 10.1136/adc.49.10.789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ranke MB, Pflüger H, Rosendahl W, et al. Turner syndrome: spontaneous growth in 150 cases and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr 1983;141:81–8. 10.1007/BF00496795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Federici S, Goggi G, Quinton R, et al. New and consolidated therapeutic options for pubertal induction in hypogonadism: in-depth review of the literature. Endocr Rev 2021;170:1–28. 10.1210/endrev/bnab043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein KO, Rosenfield RL, Santen RJ, et al. Estrogen replacement in turner syndrome: literature review and practical considerations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018;103:1790–803. 10.1210/jc.2017-02183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swee DS, Javaid U, Quinton R. Estrogen replacement in young hypogonadal women—transferrable lessons from the literature related to the care of young women with premature ovarian failure and transgender women. Front Endocrinol 2019;10:685. 10.3389/fendo.2019.00685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]